Abstract

The microaerophilic pathogen Campylobacter jejuni possesses inducible systems for resisting NO. Two globins—Cgb (a single-domain globin) and Ctb (a truncated globin)—are up-regulated in response to NO via the positively acting transcription factor NssR. Our aims were to determine whether these oxygen-binding globins also function in severely oxygen-limited environments, as in the host. At growth-limiting oxygen transfer rates, bacteria were more S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) sensitive, irrespective of the presence of Cgb, Ctb, or NssR. Pregrowth of cells with GSNO enhanced GSNO resistance, even in nssR and cgb mutants, but transcriptomic profiling of oxygen-limited, NO-exposed cells failed to reveal the NssR regulon. Nevertheless, globin expression in an Escherichia coli mutant lacking the NO-detoxifying flavohemoglobin Hmp showed that Cgb and Ctb consume NO aerobically or anoxically and offer some protection to respiratory inhibition by NO. The constitutively expressed nitrite reductase NrfA does not provide resistance under oxygen-limited conditions. We, therefore, hypothesize that, although Cgb and NrfA can detoxify NO, even anoxically, they are neither up-regulated nor functional under physiologically relevant oxygen-limited conditions and, second, responses to NO do not stem from trancriptional regulation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 18, 424–431.

Introduction

NO and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) attack invading bacteria, which should, therefore, possess detoxifying mechanisms (1). The archetypal NO-detoxifying enzyme is flavohemoglobin Hmp, which is transcriptionally activated by RNS and protects enterobacteria from NO by catalyzing NO conversion to nitrate (1). Campylobacter species, the leading cause of gastroenteritis, encounter NO and RNS derived from host NO synthases, dietary nitrate, and salivary nitrite (5) yet lack flavohemoglobin. However, Campylobacter jejuni has two other globins whose induction by NO is mediated via NssR (Cj0466, a member of the Crp-Fnr superfamily of transcription regulators, distinct from NsrR, a member of the Rrf2 family of transcription repressors). NssR controls a small regulon (2), including cgb (Cj1586), encoding a myoglobin-like protein (3) and ctb (Cj0465c) encoding a truncated globin. Cgb is the major NO-detoxifying protein (3) and catalyzes (similar to Hmp) the detoxification of NO, presumably by aerobic conversion to nitrate, whereas the mutation of Ctb does not compromise nitrosative stress tolerance.

However, a microaerophile, C. jejuni grown with higher oxygen provision has elevated globin levels, is more NO resistant, and consumes NO faster (6). Here, we report for the first time the responses to nitrosative stress that occur under host-relevant oxygen-limited conditions: although Cgb and Ctb scavenge NO under oxygen limitation and anoxically, they are not involved in NO tolerance. The nitrite reductase NrfA is not essential for inducible protection of respiration from inhibition by NO in oxygen-limited cells.

Results, Discussion, and Future Directions

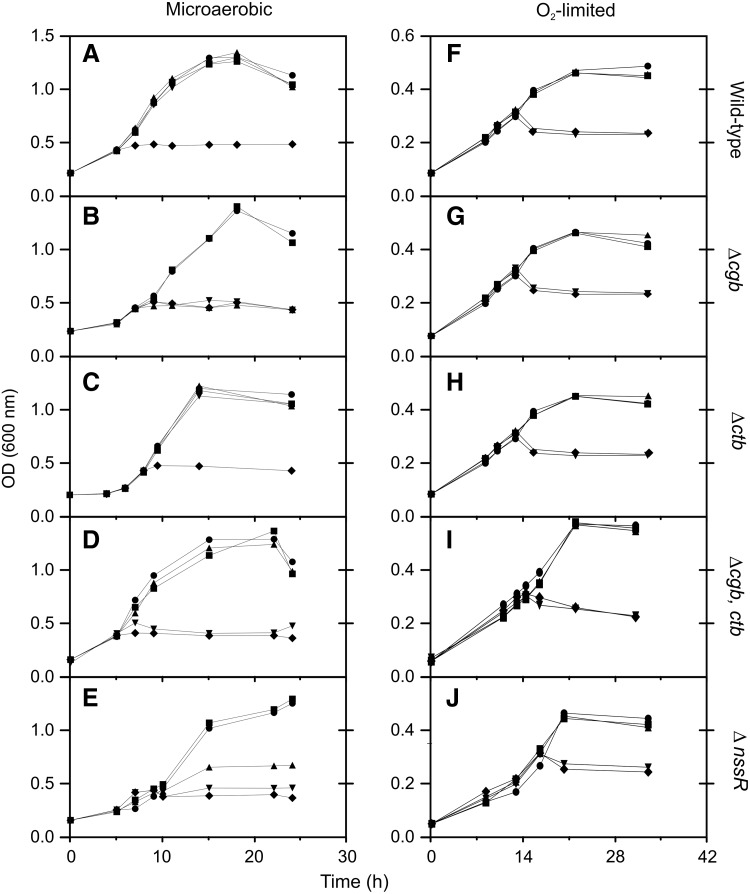

To evaluate globin function, we assayed growth of the wild-type strain and globin and regulator mutants of C. jejuni with S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO), a nitrosating agent. Cells cultivated with drastically limited oxygen supply (“oxygen-limited,” KLa=0.06 min−1) grew poorly compared with cells grown normally in a 10% oxygen atmosphere (“microaerobic,” KLa=0.43 min−1; Fig. 1). Microaerobically, the wild-type strain (Fig. 2A) and ctb mutant (Fig. 2C) grew with 400 μM GSNO (added at OD 0.3) or lower, and only 600 μM GSNO was toxic, but the mutation of cgb (Fig. 2B) caused cells to be sensitive to 200 μM GSNO and higher concentrations. Unexpectedly, a mutant lacking both globins (Fig. 2D) was less sensitive than the cgb mutant and grew with 200 μM GSNO, suggesting that a cgb mutation is partially suppressed by mutating the second globin. The nssR mutant, which lacks GSNO-induced globin expression, exhibited an intermediate response (Fig. 2E), suggesting that NssR may up-regulate an alternative nonglobin resistance mechanism. In contrast, in oxygen-limited conditions, all strains were equally sensitive to GSNO and grew only at 50 or 75 μM GSNO (Fig. 2F–J).

FIG. 1.

Growth of Campylobacter jejuni under normal microaerobic conditions (circles) and O2-limited conditions (squares).

FIG. 2.

Responses of C. jejuni growth to S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO). Five strains (NTCC 11168 [wild-type], Δcgb, Δctb, Δcgb-ctb; ΔnssR) were grown under normal microaerobic conditions (A–E) and O2 limitation (F–J) and exposed at an OD600 of 0.3 to increasing concentrations of GSNO. In (A–E), the concentrations are 0 (●), 100 (■), 200 (▴), 400 (▾), and 600 (♦) μM; in (F–J), the concentrations are 0 (●), 50 (■), 75 (▴), 100 (♦), and 150 (▾) μM.

Innovation.

Microaerobically, Campylobacter jejuni senses NO via NssR, which up-regulates two hemoglobin genes. Here, exploiting the genetic malleability of this pathogen, we ask whether either globin functions in NO tolerance in the oxygen-limited environment of the host. We show for the first time that, under oxygen limitation, C. jejuni retains tolerance to NO and S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO), but this is independent of NssR, the globins, and the nitrite reductase NrfA, even though both globins consume NO aerobically and anoxically. Thus, the presence of a potentially NO-detoxifying protein is not evidence that NO detoxification is its function in bacteria under physiological growth conditions.

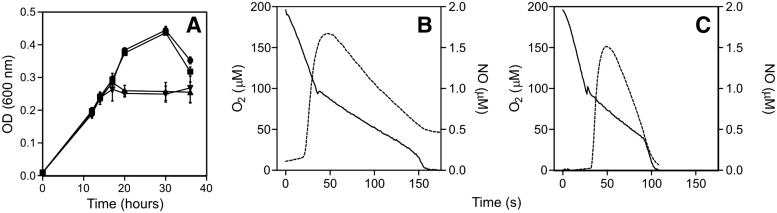

In the absence of Cgb or NssR, do oxygen-limited C. jejuni lack, therefore, an adaptive response to nitrosative stress? GSNO (50 μM) added at OD 0.3 and again 1 h later [when Cgb expression peaks (6)] was less toxic than a single bolus (100 μM GSNO) in wild-type cells (Fig. 3A), the cgb mutant (Fig. 3B), and nssR mutant (Fig. 3C). Thus, oxygen-limited bacteria retain a modest adaptive response to nitrosative stress without NssR or Cgb.

FIG. 3.

Oxygen-limited cells retain an adaptive response. Growth curves of (A) C. jejuni NTCC 11168 (wild-type), (B) C. jejuni Δcgb, (C) C. jejuni ΔnssR cultured under O2 limitation and exposed to: (●) 0 μM GSNO; (■) 50 μM GSNO plus a further identical addition 1 h later; (▴) 100 μM GSNO once. The arrows define the point of addition of GSNO at an OD600 of about 0.3.

It is unclear how such oxygen-limited cells might resist RNS. Microaerobically, GSNO up-regulates >90 genes, including the NssR regulon (6). Here, we show that NO (3-[2-hydroxy-1-(1-methylethyl)-2-nitrosohydrazino]-1-propanamine [NOC-5] plus 3-(2-hydroxy-1-methyl-2-nitrosohydrazino)-N-methyl-1-propanamine [NOC-7]) also up-regulated >2-fold 40 genes in both batch and continuous cultures (selected genes shown in Table 1), including 3 NssR-regulated genes (2) and the 2 globin genes. As confirmation, we showed that 23 genes were also up-regulated by NOCs in a microaerobic chemostat (6). Of these, six were common to batch and chemostat cultures, including both globin genes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Selected Genes with Increased or Decreased Transcript Levels in Wild-Type Campylobacter jejuni NCTC 11168 After Microaerobic Growth in Batch or Continuous Culture and 15 Min Exposure to NOC-5 and -7 (10 μM Each)

| Gene number | Gene name, protein and function | p-Value | Fold change in microaerobic batch culture (and chemostat) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Genes implicated in nitrosative stress tolerance | |||

| cj1586 | cgb; Campylobacter jejunihemoglobin; detoxification of NO and RNS. | 0.017 | 30.4 (5.75) |

| cj0379c | yedY; molybdenum-containing sulfite oxidase-like periplasmic protein; mutant deficient in chicken colonization and has a RNS phenotype | 0.0080 | 3.08 |

| cj0466 | nssR; nitrosative stress regulator. | 0.007 | 2.19 |

| cj1358c | nrfH; tetraheme NapC-like cytochrome c; electron donor to NrfA (see text) | 0.0067 | −14.3 |

| 2. Binding and transport | |||

| cj1659 | p19, probably involved in iron uptake | 0.014 | 10.6 (2.27) |

| 3. Respiration, metabolism and biosynthesis | |||

| Cj0465c | ctb; truncated hemoglobin, possible role in facilitated diffusion of oxygen to terminal oxidase(s). | 0.035 | 10.1 (22.7) |

| 4. Hypothetical gene products | |||

| cj0761 | Unknown product | 0.045 | 2.33 (4.22) |

Down-regulated genes are underlined; genes previously identified as members of the NssR regulon are shown in bold. Genes selected are members of the NssR regulon or previously implicated in RNS tolerance. For details, see text.

RNS, reactive nitrogen species.

However, transcriptomic analysis of oxygen-limited cells revealed only 10 genes to be up-regulated and 3 genes to be down-regulated (Table 2); none of these has known or predicted roles in resisting NO. Interestingly, Cj1585c, the gene adjacent to cgb, encoding a lactate dehydrogenase (8), was marginally up-regulated; this oxidoreductase could be the cognate reductase that catalyzes Cgb turnover during NO detoxification. The NOC-inducible genes in microaerobic conditions (Table 1) and oxygen-limited conditions (Table 2) were mutually exclusive. Western immunoblotting with anti-Cgb antibodies confirmed the absence of Cgb in wild-type cells grown under conditions of nitrosative stress under oxygen limitation (results not shown). We conclude that the NssR regulon is not induced under oxygen-limited conditions.

Table 2.

Genes with Increased and Decreased Transcript Levels After Treatment of O2-Limited Cultures with NO

| Gene | Gene product and function | Fold increase or decreasea | p-Value (<0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|

| cj0845c | Glutamyl-tRNA synthetase | 2.76 | 0.037 |

| cj0032 | Putative type IIS restriction/modification enzyme | 2.74 | 0.044 |

| cj1515c | Putative decarboxylase | 2.53 | 0.042 |

| cj0707 | 3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonic-acid transferase | 2.13 | 0.028 |

| cj1585c | Putative oxidoreductase | 1.90 | 0.046 |

| cj1217c | Conserved hypothetical protein | 1.75 | 0.045 |

| cj0849c | Conserved hypothetical protein | 1.54 | 0.022 |

| cj1269c | N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine amidase | 1.42 | 0.029 |

| cj1228c | Periplasmic serine protease, DODeqQ family | 1.31 | 0.037 |

| cj0391c | Hypothetical protein | 1.04 | 0.020 |

| cj0522 | Putative Na+/Pi cotransporter protein | −2.06 | 0.029 |

| cj0730 | Putative ABC transport system permease | −2.44 | 0.029 |

| cj0973 | Hypothetical protein | −2.94 | 0.0087 |

Genes up-regulated are indicated by positive values and down-regulated genes are negative and in bold. Expression data are values for oxygen-limited cultures exposed to 10 μM NOC-5 and NOC-7 for 15 min relative to untreated cultures.

NOC-5, 3-[2-hydroxy-1-(1-methylethyl)-2-nitrosohydrazino]-1-propanamine; NOC-7, 3-(2-hydroxy-1-methyl-2-nitrosohydrazino)-N-methyl-1-propanamine.

Since the NssR regulon does not confer resistance to GSNO (Fig. 2E, J) and is not NO regulated under oxygen limitation (Table 2), we determined respiratory sensitivity to a fast NO releaser, PROLI NONOate (half-life of 1.8 s at 37°C, pH 7.4, liberating 2 mol of NO per mol) as a measure of protective mechanisms (3). Microaerobic wild-type cells pretreated with GSNO were more NO resistant (i.e., more rapid NO consumption and a shorter inhibition period (typically 18 s) than unadapted cells (51 s) (Fig. 4A, B), and the half time for NO decay was reduced from 30 to 5 s in GSNO-pretreated cells. However, oxygen-limited cells were compromised in their NO response. Pretreatment with GSNO reduced only marginally the period of NO inhibition (e.g., for 2 μM PROLI NONOate, 37 and 44 s, respectively for cells treated or not with GSNO) (Fig. 4C, D and inset). In contrast, the nssR mutant loses the adaptive response elicited by GSNO microaerobically (Fig. 5A, B), whereas oxygen-limited cells retained an adaptive response to RNS (compare Fig. 5B with A and Fig. 5D with C).

FIG. 4.

Cell respiration and NO detoxification in wild-type C. jejuni. Cell suspensions from cultures harvested at OD600 of 0.3 were exposed to 2 μM PROLI NONOate at ∼50% air saturation (at the arrows). Respiration was started by the addition of 50 mM sodium formate. The left panel shows cultures grown under normal microaerobic conditions (A) or under O2 limitation (C). The right panel shows cultures pretreated with 75 μM GSNO for 15 min under normal microaerobic conditions (B) or under O2 limitation (D). The continuous line represents the oxygen trace, and the dashed line shows the NO trace. The dotted line shows a control trace after an injection of 2 μM PROLI NONOate in the absence of cells. The inset in (D) shows the period of inhibition by PROLI NONOate with (lower line) or without (top) GSNO pretreatment.

FIG. 5.

Cell respiration and NO detoxification in an nssR mutant of C. jejuni. Details are as in Figure 4. The continuous line represents the oxygen trace, and the dashed line shows the NO detected after an injection of 2 μM PROLI NONOate (arrow). The dotted line shows a trace after an injection of 2 μM PROLI NONOate in the absence of cells.

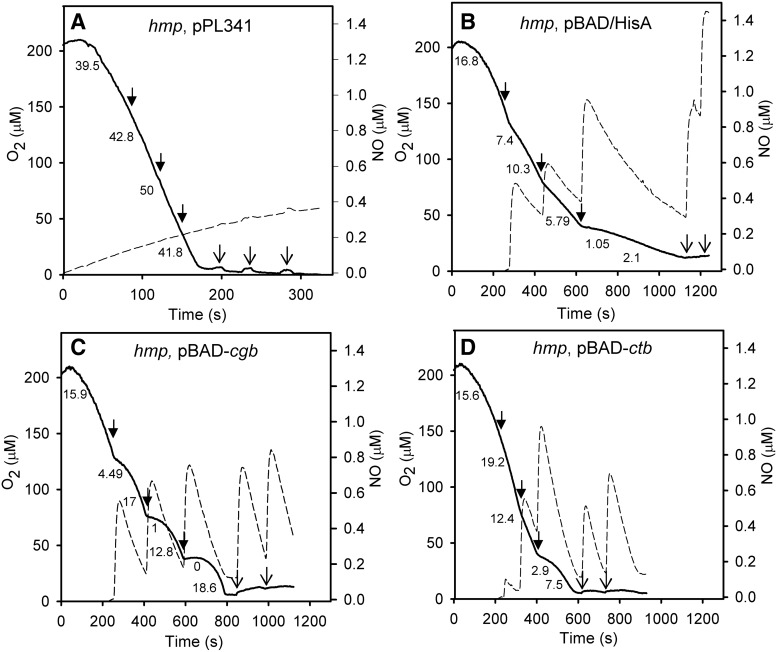

How can NO detoxification activity of the globins be confirmed when they lack a reductase domain as in flavohemoglobins (3) and when globin over-expression in C. jejuni is problematic? We expressed each globin in an Escherichia coli hmp mutant and asked whether NO tolerance is restored. Measuring the removal of NO from solution and consequent protection of respiration provided direct evidence of NO-detoxifying activity. When Hmp is expressed in an hmp mutant (Fig. 6A), additions of PROLI NONOate to cells did not inhibit respiration or register a response from the NO electrode. Even on anoxia, further NONOate additions were barely detected (Fig. 6A), revealing robust anoxic NO detoxification by Hmp (1). However, both Cgb and Ctb, expressed from pBAD, exhibited only modest NO uptake and did not fully protect respiration rates from repeated NO additions (Fig 6C, D). The half times for decay of the NO pulses were, however, significantly shorter than in E. coli transformed with a control plasmid lacking the globin genes (Fig. 6B). To investigate whether catalytic NO detoxification occurred, we determined globin levels by assaying heme; the Cgb concentration in the electrode chamber was 0.68 μM, and the Ctb concentration was 2.6 μM. Since the five sequential additions of NO were each 1 μM, NO removal should be attributed to globin-mediated enzymic detoxification, both aerobically and anaerobically.

FIG. 6.

Protection from NO by globins. Respiration and NO uptake in Escherichia coli hmp mutant cell suspensions expressing Hmp (A), the vector only (B), Cgb (C), or Ctb (D). Cultures were grown in the presence of arabinose and cells resuspended in Tris buffer; glycerol was added to promote respiration. Oxygen (solid line) and NO (dashed line) were polarographically recorded simultaneously. Respiration rates (nmol O2 min−1 mg protein−1) at different oxygen tensions after additions of 1 μM PROLI NONOate are shown on the traces. Arrows indicate the addition of PROLI NONOate in aerobic (closed arrows) or anaerobic (open arrows) conditions.

What protein other than the globins might be responsible for the GSNO-inducible tolerance to NO in oxygen-limited cultures? NrfA is a constitutively expressed nitrite reductase that confers NO tolerance (7); so, we tested GSNO sensitivity of an nrfA mutant, and it was indistinguishable from the wild type (Fig 7A; compare with Fig. 2F). Pregrowth of this mutant with GSNO markedly reduced the extent of respiratory inhibition (Fig. 7C) compared with uninduced cells (Fig. 7B); therefore, NrfA cannot explain the inducible NO tolerance of oxygen-limited cells.

FIG. 7.

NrfA does not confer GSNO tolerance to growth or respiratory inhibition. Panel (A) shows growth curves of oxygen-limited C. jejuni ΔnrfA cultures exposed to increasing concentrations of GSNO: (●) control, (■) 50 μM, (▾), 100 μM, (▴) and 150 μM. The growth behavior and GSNO sensitivity is identical to wild-type cultures. For studies of respiration and NO consumption, a C. jejuni ΔnrfA cell suspension (OD 600 nm=0.3) was exposed to 2 μM PROLI NONOate when the oxygen concentration was 50% of air saturation. Panel (B) shows oxygen-limited control cultures, and panel (C) shows cells pretreated with 75 μM GSNO for 15 min. The continuous line represents the oxygen trace (left ordinate), and the dashed line shows the NO generated by PROLI NONOate in the presence of cells (right ordinate).

Our conclusions on globin function are enabled by the genetic tractability of C. jejuni; although microbial globins are widespread, most of those studied are not amenable to genetic analysis and so, only heterologous expression in other hosts (4) or studies with purified proteins have been reported. In contrast, each C. jejuni globin has been inactivated, a sensor of nitrosative stress has been identified, and RNS sensitivity may be correlated with loss of Cgb. Here, we show that the C. jejuni globins are not up-regulated and do not provide protection from NO and GSNO under the oxygen-limited conditions prevailing in host niches for this pathogen. Such microaerobic conditions may occur in vivo: Bacteria from chick cecal contents have elevated transcript levels for genes involved in C4-dicarboxylate transport, a terminal oxidase thought to have very high oxygen affinity (ccoNOPQ), and other anoxically expressed genes (9). The oxygen and NO concentrations experienced by C. jejuni in vivo are uncertain. In the porcine jejunum, the vasculature produces an oxygen gradient reaching about 80 μM (i.e., similar to that when NO is added, Figs. 4–6); whereas in other regions of the alimentary canal, it is assumed that free oxygen concentration is zero. Interestingly, both Cgb and Ctb are capable of NO consumption in vitro, even in anoxia (Fig. 6), at NO concentrations close to those generated (20 μM) by RAW264.7 macrophages stimulated by bacterial lipopolysaccharide.

Why might the increased NO and RNS sensitivity seen under oxygen-limited conditions be independent of globin function? One possibility is that under oxygen-limited conditions, there is insufficient free oxygen that supports the dioxygenase/denitrosylase activity, as suggested earlier (6). Another possibility is that, under oxygen limitation, it is not NO per se that is toxic, but a distinct species which is generated perhaps by a reaction of NO with superoxide anion to give peroxynitrite or by a reaction of NO with a metal center to generate NO+, a potent nitrosating agent, consistent with the formation of S-nitrosated proteins in several bacteria (1). Since NO itself is not an effective nitrosating agent, requiring the additional presence of oxygen or a metal ion (1), this suggests that the toxic species in vivo may be NO+, against which the NO-detoxifying globins are ineffective. Clearly, however, other cellular consequences of NO, such as interaction with hemes or Fe-S clusters, are dependent only on NO per se (1). It will, therefore, be important to identify the targets of NO and nitrosative stresses in C. jejuni under conditions of oxygen limitation.

Notes

Bacterial strains

All C. jejuni strains were derived from the sequenced strain, NCTC 11168. The mutants used were cgb::Tetr, ctb::Kanr, a double globin mutant (cgb::Tetr ctb::Kanr,), nssR::Kanr and nrfA::CmR. Details of all were previously published by our laboratories.

Plasmids and the cloning and expression of hmp, cgb and ctb in E. coli

pPL341 is the vector pBR322 (AmpR) containing the E. coli hmp+ gene expressed from its own promoter. pLW1 (pBAD-ctb) is a 380 bp PCR product containing the ctb+ gene cloned between the NcoI and HindIII sites in pBAD/HisC under control of an arabinose-inducible promoter. pBAD-cgb is a 830 bp fragment containing the cgb+ gene cloned between the NcoI and XhoI sites in pBAD/HisA (Invitrogen). Constructions were verified by sequencing. The expression of globins was evaluated by immunoblotting and heme assays and dual-wavelength scanning of difference spectra of cell-free supernatant fractions.

Reagents for imposing NO and nitrosative stress

The NO-releasing compounds NOC-5 and NOC-7 (both Calbiochem) have half lives at 42°C of 10.5 (NOC-5) and 3.0 (NOC-7) min. Stock solutions (0.1 M) of each were made up in 0.1 M NaOH. The fast-acting NO donor used was PROLI NONOate (Cayman Chemical). GSNO was prepared using a published method from the reaction of glutathione and acidified nitrite.

Bacterial growth protocols

Microaerobic conditions (10% O2, 10% CO2, and 80% N2) for C. jejuni were generated at 42°C in a MACS-VA500 workstation (Don Whitley Scientific Ltd). For growth under the normal microaerobic conditions used for C. jejuni (“normal aeration”), liquid cultures (50 ml) were grown in Mueller–Hinton broth in 100 ml conical flasks overnight before use as a 3% (v/v) inoculum for 150 ml MH broth in 250 ml baffled flasks. Cultures were shaken inside the workstation on a Mini-Orbital Shaker SO5 (Stuart Scientific) at ∼125 rpm and growth was measured using OD600nm. For growth under oxygen-limited conditions (“low aeration”); the culture volume was increased to 200 ml in the same flasks. The oxygen transfer rates in such conditions, measured by the sulfite oxidation method and expressed as an oxygen diffusion rate, KLa, from gas to liquid were 0.43 min−1 (microaerobic aeration) and 0.06 min−1 (oxygen-limited conditions). Growth was monitored by measuring OD (apparent absorbance) at 600 nm. For E. coli, bacteria were grown on LB plates (supplemented with antibiotics) and liquid cultures grown aerobically in LB at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm.

Transcriptomic analysis and the response to NOCs and the effect of aeration

At an OD600 nm of ∼0.3, cultures, NOC-5 and −7 (10 μM each) were added, and the cultures were incubated for a further 15 min. Samples (30 ml) were taken from each flask and mixed immediately on ice with ethanol/phenol to stabilize RNA. Total RNA was purified using a Qiagen RNeasy mini kit, and a microarray analysis of three biological replicates was carried out using C. jejuni NCTC 11168 “Pan” arrays from Ocimum. Procedures complied with MIAME standards (www.mged.org/), and data are deposited in the GEO database (reference Series GSE38114, 38115 and 38116.)

Determination of respiration rates and NO consumption

Gas consumption was measured in a custom-built vessel housing both oxygen and NO electrodes. For intact cells, sodium formate (5 mM) was added as reductant, and the oxygen concentration was allowed to decrease by ∼50%. A stock PROLI NONOate solution was then added using a Hamilton microsyringe to give a final concentration of 2 μM. The initial respiratory rate, the inhibited rate, and the rate when oxygen uptake was spontaneously reinitiated were calculated. All respiratory data are means of two measurements of cells from a single culture. Similar data were obtained in triplicate cultures. Where indicated, cultures that had reached an OD600 of 0.3 were supplemented with 50 μM GSNO, and incubated for a further 15 min, then treated with 100 μM chloramphenicol, before washing and resuspension in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) and adjustment to an OD600 of 0.3. Measurements of the period during which cell respiration was inhibited by PROLI NONOate were made at increasing NONOate concentrations, and a linear regression analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 5.04 for Windows (GraphPad Software; www.graphpad.com).

For measurements of E. coli cells expressing C. jejuni globins, cells from overnight cultures (45 ml) in LB supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml), kanamycin (35 μg/ml), 0.02% arabinose, 12 μM FeCl3, and 200 μM δ-aminolevulinic acid were resuspended in buffer (8 ml 50 mM Tris pH 7). Respiration rates were measured as just described in a working volume of 2 ml at 37°C. Glycerol (5 mM) was added to promote respiration, and PROLI NONOate solution was added (final concentration 1 μM) as shown. Respiratory data are means of five measurements of a single culture. Similar data were obtained in duplicate cultures.

The oxygen and NO concentrations used here are relevant to those experienced by C. jejuni in vivo. In the porcine jejunum, the vascular arrangement produces a measurable oxygen gradient reaching 26.5 Torr (∼44 μM O2) or 62 μM O2; whereas in other regions of the gastrointestinal tract, it is often assumed that free oxygen concentration is essentially zero. NO concentrations used in our experiments are lower than those accumulated (20 μM) by, for example, RAW264.7 macrophages stimulated by bacterial lipopolysaccharide but higher than the normally presumed physiological range, that is, approximately 0.1 μM.

Abbreviations Used

- CmR

chloramphenicol-resistant

- GSNO

S-nitrosoglutathione

- KanR

kanamycin-resistant

- NOC-5

3-[2-hydroxy-1-(1-methylethyl)-2-nitrosohydrazino]-1-propanamine

- NOC-7

3-(2-hydroxy-1-methyl-2-nitrosohydrazino)-N-methyl-1-propanamine

- PROLI NONOate

1-(hydroxy-NNO-azoxy)-L-proline, disodium salt

- RNS

reactive nitrogen species

- TetR

tetracycline-resistant

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnologia (Mexico) through grant numbers 207780 (Carlos Avila-Ramirez) and 99171 and COECYT Michoacán 007 (Mariana Tinajero-Trejo). The authors thank Dr. Cinzia Verde for helpful discussions.

References

- 1.Bowman LAH. McLean S. Poole RK. Fukuto J. The diversity of microbial responses to nitric oxide and agents of nitrosative stress: close cousins but not identical twins. Adv Microb Physiol. 2011;59:135–219. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387661-4.00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elvers KT. Turner SM. Wainwright LM. Marsden G. Hinds J. Cole JA. Poole RK. Penn CW. Park SF. NssR, a member of the Crp-Fnr superfamily from Campylobacter jejuni, regulates a nitrosative stress-responsive regulon that includes both a single-domain and a truncated haemoglobin. Mol Microbiol. 2005;57:735–750. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elvers KT. Wu G. Gilberthorpe NJ. Poole RK. Park SF. Role of an inducible single-domain hemoglobin in mediating resistance to nitric oxide and nitrosative stress in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:5332–5341. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.16.5332-5341.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frey AD. Farres J. Bollinger CJT. Kallio PT. Bacterial hemoglobins and flavohemoglobins for alleviation of nitrosative stress in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:4835–4840. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.10.4835-4840.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iovine NM. Pursnani S. Voldman A. Wasserman G. Blaser MJ. Weinrauch Y. Reactive nitrogen species contribute to innate host defense against Campylobacter jejuni. Infect Immun. 2008;76:986–993. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01063-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monk CE. Pearson BM. Mulholland F. Smith HK. Poole RK. Oxygen- and NssR-dependent globin expression and enhanced iron acquisition in the response of Campylobacter to nitrosative stress. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:28413–28425. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801016200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pittman MS. Elvers KT. Lee L. Jones MA. Poole RK. Park SF. Kelly DJ. Growth of Campylobacter jejuni on nitrate and nitrite: electron transport to NapA and NrfA via NrfH and distinct roles for NrfA and the globin Cgb in protection against nitrosative stress. Mol Microbiol. 2007;63:575–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas MT. Shepherd M. Poole RK. van Vliet AHM. Kelly DJ. Pearson BM. Two respiratory enzyme systems in Campylobacter jejuni NCTC 11168 contribute to growth on L-lactate. Environ Microbiol. 2011;13:48–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woodall CA. Jones MA. Barrow PA. Hinds J. Marsden GL. Kelly DJ. Dorrell N. Wren BW. Maskell DJ. Campylobacter jejuni gene expression in the chick cecum: evidence for adaptation to a low-oxygen environment. Infect Immun. 2005;73:5278–5285. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.8.5278-5285.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]