Abstract

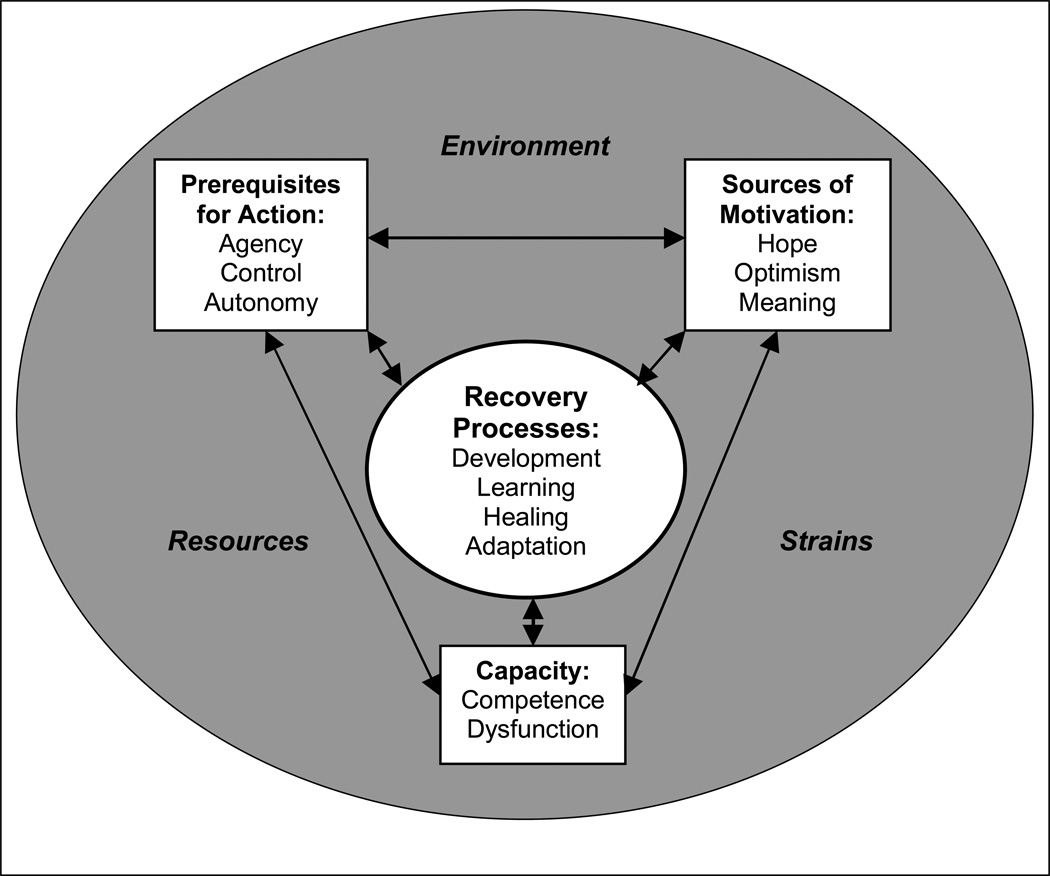

In the past, “recovery” from serious mental health problems has been variously defined and generally considered rare. Current evidence suggests that some form of recovery is both possible and common, yet we know little about the processes that differentiate those who recover from those who do not. This paper discusses approaches to defining recovery, proposes a model for fostering, understanding, and studying recovery, and suggests questions for clinicians, researchers, and policy makers. The proposed model is a synthesis of work from the field of mental health as well as from other disciplines. Environment, resources, and strains, provide the backdrop for recovery; core recovery processes include development, learning, healing, and their primary behavioral manifestation, adaptation. Components facilitating recovery include sources of motivation (hope, optimism, and meaning), prerequisites for action (agency, control, and autonomy), and capacity (competence and dysfunction). Attending to these aspects of the recovery process could help shape clinical practice, and systems that provide and finance mental health care, in ways that promote recovery.

Keywords: Mental Illness, Mental Health, Serious Mental Illness, Recovery, Conceptual Model, Policy

Serious mental illnesses, including schizophrenia, schizoaffective, and bipolar disorders, are prevalent (American Psychiatric Association, 1994a) and costly conditions (National Advisory Mental Health Council, 1993; Rice & Miller, 1996; 1998). In addition to their impact on affected individuals and their families, they have significant effects on health systems and societies, are among the leading causes of disability in developed countries (Murray & Lopez, 1996), and are increasingly important public health concerns (Neugebauer, 1999; US Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, & National Institute of Mental Health, 1999).

Historically, severe mental illnesses have been viewed as chronic, deteriorating disorders (Angst & Sellaro, 2000; Harding & Zahniser, 1994) when, in fact, recovery rates are reasonably consistent with Warner’s 1994 analysis (Warner, 1994) of 85 outcome studies of people with schizophrenia. About 20–25% make a complete recovery (absence of psychotic symptoms and return to pre-illness functioning levels) and 40–45% achieve social recovery (economic and residential independence and low social disruption). Outcomes for the remaining 30–40% remain poor (Angst & Sellaro, 2000; Davidson & McGlashan, 1997; DeSisto, Harding, McCormick, Ashikaga, & Brooks, 1995b; DeSisto, Harding, McCormick, Ashikaga, & Brooks, 1995a; Gitlin, Swendsen, Heller, & Hammen, 1995; Grossman, Harrow, Goldberg, & Fichtner, 1991; Harding, Brooks, Ashikaga, Strauss, & Breier, 1987a; 1987b; Harding, Zubin, & Strauss, 1987; 1992; Hegarty, Baldessarini, Tohen, Waternaux, & Oepen, 1994; Wiersma, Nienhuis, Slooff, & Giel, 1998).

Despite improvements in treatment, however, we remain mostly ignorant about the processes leading to these different outcomes. I believe it is time to leave behind our focus on pathology and to begin studying the pathways and processes leading to successful recoveries. In this way, those who have recovered from serious mental health problems can teach us ways to help those who have fared less well.

Defining Recovery

“Recovery,” in the context of serious mental illness, has been an elusive and sometimes divisive concept, primarily because it is situated in multiple communities, including researchers, clinicians, families, consumer activists, and policy makers, as well as those who live and cope with these disorders. For some, recovery means returning to a “premorbid” level of functioning; others dispute this definition, viewing such a goal as negating the importance of the personal growth and development that has taken place. Depending on perspective, recovery may be seen as the lack of need for mental health care, or may mean using services and medications at levels necessary to maintain a stable or happy life. Recovery may also be defined as the ability to adequately fulfill role obligations despite some limits in functioning. Others argue that recovery should be seen as distinct from disability and role obligations. In addition, people use the term to describe recovery in the most general sense—achieving well-being or a satisfying life—but also to describe recoveries following acute symptom exacerbations. Domain-specific recoveries (such as social or vocational recovery) further add to this definitional confusion, as does the fact that the human condition is rarely stable, even aside from the presence or absence of mental health problems. Well-being waxes and wanes as a normal part of living and interacting. Moreover, a broad range of abilities, satisfaction, and happiness levels exists under normal circumstances among community populations. For these reasons, recovery cannot be seen as either a single or a fixed state, but must be conceptualized as an ongoing process.

Efforts to navigate within this definitional maze can produce vastly different clinical perspectives and “recovery-oriented” treatment systems, as well as strict operationalizations of recovery that, although potentially useful in research contexts, can erroneously lead to standards that require the “recovered” person to achieve functional status and happiness levels that fall only within the upper ranges of what is observed in the general population. For example, many adults without mental health problems cannot meet the following definition of recovery: “…symptom remission; full- or part-time involvement in work or school; independent living without supervision by family or surrogate caregivers; not fully dependent on financial support from disability insurance; and having friends with whom activities are shared on a regular basis…[each] sustained for at least two consecutive years” (Liberman, Kopelowicz, Ventura, & Gutkind, 2002). The homemaker, the woman laid off in a poor economy, the physically disabled individual, the person who has recently experienced the death of a loved one, or the man who desires less social contact, would have difficulties meeting these criteria, as would the individual who functions adequately in all domains despite continued symptoms. And what of romantic partnerships, a good sexual life, and spiritual fulfillment? These are fundamental aspects of the human experience, yet are often left out of recovery conceptualizations and measures. To ignore them in research because of conceptual or measurement difficulties will leave our understanding of recovery incomplete and weak; to ignore them in clinical practice leaves critical human needs unaddressed.

Definitions like the one above also do not account for the fact that progress in and of itself, or stability and contentment at various functional levels, are sometimes what people desire or find comfortable (Diener, 2000). Some people choose not to work, but maintain an active, involved, and fulfilling life. If we are to foster recovery among the full range of individuals with mental health problems, there must be room in our definitions and measures for a variety of forms, processes, and outcomes corresponding to the normal variations in lifestyles, desires, and competencies of individuals who do not have to cope with mental illness. Stringent definitions are useful for measurement, but clinicians, families, and consumers must be careful in applying such definitions so that confidence in recovery is not undermined in the face of unfavorable or unreasonable comparisons.

I use the term “recovery” in the context of serious mental illness to describe the active process of moving toward achieving well-being and a satisfying life, or the process of maintaining a stable level of well-being, mindful that these processes and states include a range of well-being statuses, life satisfaction, or progress towards those ends, just as is true among individuals who do not have mental health problems.

Conceptualizing the Recovery Process

While we have good models of disablement (Pope & Tarlov, 1991; Verbrugge & Jette, 1994), models of recovery are few. To date, most research and publications have explored “better outcomes”—primarily domain-specific, such as social or vocational recovery, relapse prevention, symptom control, and recoveries from acute episodes (Hoffmann & Kupper, 2002; Russinova, Wewiorski, Lyass, Rogers, & Massaro, 2002; Whitehorn, Brown, Richard, Rui, & Kopala, 2002), or on recovery-based treatment programs and personal empowerment in the treatment and rehabilitation process (Anthony, 1993; Deegan, 1988; Fisher, 1994; Frese, Stanley, Kress, & Vogel-Scibilia, 2001). Consistent with this focus, most existing models have been developed as part of treatment programs (Ahern & Fisher, 1999; Anthony & Liberman, 1986; Spaniol, Koehler, & Hutchinson, 1994; Townsend, Boyd, Griffin, & Hicks, 1999), concentrating little on aspects of recovery outside the immediate realm of mental health services. Broader models are now under development (Ralph et al., 2000), however, and reports addressing both the recovery process and whole-person outcomes are becoming available (Harrison et al., 2001; Liberman et al., 2002; Onken, Dumont, Ridgway, Dornan, & Ralph, 2003; Spaniol, Wewiorski, Gagne, & Anthony, 2002; Torgalsboen & Rund, 2002). That is, we have begun to take on the difficult task of understanding recovery in the global sense, examining the production of recovered lives, and the definitions, meanings, and adaptations constructed by individuals for whom one of life’s critical tasks has become making sense of what it means to be affected by a serious mental disorder.

The model proposed here draws on much of this recovery-related work, integrated with research in other areas and disciplines, to provide a framework for (1) understanding the global process of recovery, (2) identifying factors necessary for recovery, and (3) developing research, interventions, and habits-of-mind that foster recovery.

The Proposed Model

Figure 1 provides a simplified representation of key components of the proposed model. Environment, resources, and strains provide the backdrop for the recovery process; development, learning, healing, and their primary behavioral manifestation, adaptation, are presented as its core. Components facilitating recovery include sources of motivation (hope, optimism, and meaning), prerequisites for action (agency, control, and autonomy), and capacity (competence and dysfunction).

Figure 1.

Proposed Model of the Recovery Process

Development, Learning, Healing, and Adaptation

Recovery is inextricably intertwined with normal processes of human development, intellectual growth, learning, experience, and healing that occur over time. Yet, despite awareness of these processes in most circumstances, researchers and practitioners (and sometimes families and consumers) can become so illness- or symptom-focused that we forget that normal developmental processes are also occurring among people coping with mental health problems. As we live our lives, time provides opportunities to learn how to manage life’s challenges and to grieve and heal following our struggles. For all of us, developmental processes lead to increased capacities; people gather experience and knowledge, acquire support systems that can be relied on, and leave behind people, places, and situations that cause them harm (Massimini & Delle Fave, 2000).

It is the rare researcher who takes a developmental approach to understanding mental health outcomes. In conventional research programs, development has mostly come into play when investigators describe the course of serious mental illnesses. To the extent that such research (e.g., age at onset, number of acute episodes, hospitalization experiences, and severity and types of symptoms) helps to identify features and dynamics that affect the recovery process, results can be useful in facilitating recovery or suggesting approaches or timing for interventions. In practice, results are rarely used in this way. Attending to learning, development, and healing, and to how they affect the timing of particular treatments, supports, and interventions, has great potential for fostering recovery.

Adaptation

Adaptation—the collective behavioral manifestation of development, learning, and healing—deserves to be treated separately. Reports from several domains provide preliminary evidence about its importance in the recovery of individuals with psychiatric disorders. Hospitalizations cluster in the early years after diagnosis with schizophrenia, and each hospitalization lowers the risk of additional hospitalizations (Eaton et al., 1992). People with bipolar disorder experience larger stretches of time between relapses (Angst & Sellaro, 2000). Later onset is related to better long-term course and increased likelihood of recovery (Davidson & McGlashan, 1997; Eaton et al., 1992; Haro, Eaton, Bilker, & Mortensen, 1994; Kessler, Foster, Saunders, & Stang, 1995), perhaps because the later the disorder occurs in the life-span, the more undisrupted time the individual has to master important developmental tasks and to accumulate the life experiences, coping techniques, self-knowledge, and social support systems that can be brought to bear when serious illness intrudes.

Other evidence comes from studies that have begun to describe the day-to-day coping techniques and adaptations developed by people with severe mental illnesses. We (Green, Vuckovic, & Firemark, 2002) found that people used various strategies for managing acute symptom exacerbations, including observing treatment recommendations carefully, adjusting medication dosages or taking additional medications as needed, withdrawing from work and social interactions, sleeping, using work and family obligations as motivating forces, controlling intake of psychoactive substances, asking for or accepting help from supportive persons, letting symptoms run their course as long as they do not become too severe, and accepting symptoms and making lifestyle adaptations so that acute exacerbations have fewer negative consequences. Such adaptations resulted in good quality of life and successful community living, despite some functional limitations. Individuals also develop methods for managing auditory hallucinations (Carter, Mackinnon, & Copolov, 1996), cognitive and behavioral strategies for coping with depression and prodromes of mania (Lam & Wong, 1997), and for preventing hospitalization (Corin & Lauzon, 1992). And, patients and relatives with more coping strategies and illness-related knowledge adapt better to schizophrenia’s negative symptoms (Mueser, Valentiner, & Agresta, 1997). In short, learning about, managing, and adapting to serious mental illness are key components of the recovery process. To date, however, most reports address only parts of the process of adaptation and recovery, mostly symptom management and relapse prevention, rather than the overall process of how individuals achieve satisfying lives.

Adaptation in Physical Illness

One in-road to learning more about the process of adapting to serious mental illness is to draw on the more copious literature about adapting to serious physical illness (Charmaz, 1994; 1999). Common responses to initial illness symptoms, to receiving diagnoses, and to functional limitations and impairments include complicated processes of denial, acceptance, and adaptation, although not necessarily in that order (Charmaz, 1991; 1995; 2000). Denial is constructed under various circumstances—the diagnosed person and his/her family may know little about the chronic condition at first diagnosis, defining the illness as acute rather than chronic. Health care providers may foster such beliefs by withholding information about the meaning and likely consequences of a particular problem. Initial illness crises support explanations of the illness as acute, and can be so overwhelming for patients and families as to prevent consideration of long-term course. In dealing with symptoms and repeated acute crises over time, individuals learn about the chronicity of their illnesses and about the effects of illness on daily life. People begin to experience their bodies as altered and come to think of illness as real in ways that allow them to account for their symptoms and the changes in their lives. They compare their present condition with that of the past, weighing the risks of continuing their regular activities and activity levels, and then altering those activity levels. They may feel estranged from the person that they have become, betrayed by their own bodies, or guilty for not meeting standards of activity levels, functioning, and appearance. People distance themselves from their illness, diagnosis, and bodies, objectifying their symptoms as a way of coping. Bodily changes also affect ill individuals’ identities in important ways, and some chronically ill people work very hard at maintaining their pre-illness identity, sometimes to the detriment of their health.

Others, and the same people at different times, may immerse themselves in their illness, taking on an illness-directed lifestyle (Charmaz, 1991). Many ultimately find ways to embrace their illnesses, and begin to recover their sense of a valuable self and achieve a better quality of life (Charmaz, 1991; 1995). Those who achieve good or excellent quality of life find ways to make sense of their symptoms and limitations, to exercise control to maximize predictability in their lives, and to conserve energy while remaining involved in the world and their social relationships (Albrecht & Devlieger, 1999).

These findings, derived from work with people who have chronic medical problems, are consistent with preliminary reports about responses to illness among people with serious mental illnesses. Such commonalities also suggest that processes often thought to be a function of the mental health problem itself (e.g., denial, avoidance of care) may actually be part of the normal course of learning about and adapting to having a life-transforming disorder. Although these processes have not been described in the same detail among people coping with mental illnesses, the parallels to what has been described are striking (e.g., Davidson & Strass (1992); Estroff [Estroff, 1989]). For example, Leete (1987) has written “I am haunted by a pervasive picture of what my life could have been, whom I might have become, what I might have accomplished.” (p. 486) and, “We must study our illness, appraise our lives, identify our strengths and weaknesses, and build on our assets while minimizing our vulnerabilities.” (p. 491).

To the extent that we ignore these parallel processes of learning, development, healing, and adaptation as they occur among individuals who have mental illness, we will continue to focus on symptoms and dysfunction rather than on recovery. Interestingly, however, those who argue against a mentally ill person immersing him or herself in the illness may be making a mistake by inadvertently interfering with part of the necessary process of learning about the disorder, its effects, and its management, and of taking stock about what this means in one’s life. Adopting an “illness identity” may turn out to be as much a normal part of the recovery process among those with mental illnesses as it appears to be among those with physical illnesses. We must learn more about these common experiences.

It also behooves us to attend to developmental changes occurring among the people who make up the support systems of individuals with mental health problems. If we do not, we will miss opportunities that arise as understanding and capacity for support and caregiving increases, and fail to address processes and experiences that may lead to reduced support.

Hope, Optimism, and Meaning

Hope, optimism, and meaning provide the underlying motivation necessary for recovery, yet it is about these components of the process that we know the least. This gap in knowledge likely has two primary sources: (1) the traditional focus on psychopathology within psychology and psychiatry (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000), and (2) discomfort about instilling unreasonable expectations regarding capabilities and future outcomes, because meaningful activities and reasonable lives were believed to be beyond the reach of most individuals with serious mental illness. Recent research suggests, however, that even when unrealistic, optimism and the ability to find meaning in adverse experiences protect health (Taylor & Brown, 1988; Taylor, Kemeny, Reed, Bower, & Gruenewald, 2000), that engaging in meaningful activities can improve functioning (Mueser et al., 1997), and that recovery is the norm rather than the exception. Taken together, such results suggest that clinicians and researchers should feel comfortable promoting and researching these key motivational forces.

Anecdotal evidence suggests several beginning points. Researchers might seek to understand how the recovery process is transformed following “low turning points” (Rakfeldt & Strauss, 1989) and to discover how such transformations might be encouraged without devastating losses. Spirituality in some individuals appears to foster the hope and optimism necessary for recovery (Whitney, 1998; Young & Ensing, 1999), yet little is known about how it can be integrated into treatment programs, or how to help clinicians manage its inclusion when they are wary of negatively affecting symptoms with religious content. Romantic partnerships, sexual relationships, parenting, and social interdependencies, so critical to providing meaning in life (Schwartz, 2000), are often disrupted by mental illness, yet we know almost nothing about the first two and only a little about the latter areas. It is also possible that we might identify important, yet simple, measures of enhancing hope and optimism, such as the best ways and times to discuss recovery.

Developing different approaches to mental illness and mental health care also hold promise. It is possible that adopting a whole-person centered, chronic disease management approach, with the health care consumer at the helm (Bodenheimer, Lorig, Holman, & Grumbach, 2002; Sullivan, 2003; Von Korff, Gruman, & Schaefer, 1997), could convert the difficulties posed by serious mental illness from an “end-of-life sentence” into a series of challenges-to-be-addressed. In doing this, we might reduce stigma while instilling hope and optimism for adjusting to these disorders and developing fulfilling lives.

At the same time, one of the most complicated tasks clinicians face is helping individuals balance competing needs for a meaningful life, meaningful activities, and development, while at the same time reducing the risk of setbacks. Clinicians may fear raising expectations or encouraging overextension that might lead to relapse, while individuals coping with mental illness may fear trying new things if they have failed in the past. In taking an overly conservative approach, however, clinicians and consumers may inadvertently destroy hope for the future and interfere with the motivation and competencies necessary to make these important steps. Researchers can and should step into this gap, evaluating different approaches and timing for taking on activities. An excellent example of such work is research showing that rather than interfering with recovery, participating in paid employment improves outcomes and reduces symptoms (Mueser et al., 1997). To the extent that we can begin to uncover similar methods for fostering hope and optimism, beliefs that a meaningful life is possible, and additional mechanisms for supporting participation in truly meaningful activities, we can help to ignite the forces that fuel recovery processes and that provide opportunities for developing necessary competencies.

Agency, Control, and Autonomy

Agency is critical to positive development, and the recovery process, because it encompasses the ability to plan, set priorities, establish goals, and exercise the methods necessary for achieving those goals (Davidson & Strauss, 1995; Larson, 2000). Although mental health problems may interfere with agency, sometimes making it appear as if an individual has lost the ability to act and make decisions, these abilities remain present, even if only at a level that allows for making microdecisions (e.g., when to eat or sleep) (Davidson & Strauss, 1995). When people are faced with such difficult situations, the agency needed for recovery may be rebuilt, starting from successes in decision-making at the micro level (Davidson & Strauss, 1995). Therefore, agency should be seen as a strength that is developed, or attenuated, over time as it is affected by experiences and outcomes. Efforts that lead to poor results or losses of function may be demoralizing, while positive outcomes may be encouraging. Similarly, better self-esteem among individuals with serious mental illness predicts increased life satisfaction and fewer symptoms, while increased symptoms lead, in turn, to worse self-esteem (Markowitz, 2001).

Control and autonomy are also key facets of recovery, for without a sense that one has at least some control over desired outcomes—and adequate autonomy and opportunity (a resource) to engage in action toward those goals—agency and motivation are undermined (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Plateau periods of apathy or withdrawal may actually be important periods of healing, occurring after particularly demoralizing experiences (e.g., severe symptom exacerbations, hospitalization), where both agency and control are practiced, tested, and rebuilt (Strauss, 1989). Such periods may produce potentially important recovery-related developments, depending on the success of these micro-efforts, the speed and timing of re-entry into a more active phase of recovery, and the availability of opportunities to effect decisions. Work on self-efficacy (Davidson & Strauss, 1992), closely related to agency and control, and on the positive impact of actions as ways of building a functional sense of self (Markowitz, 2001), support the importance of these aspects of the recovery process. At the same time, stigma, involuntary hospitalization, incarceration, and commitment can interfere with opportunities to exercise agency, reduce autonomy and control, and undermine these critical components of the recovery process.

A particularly fruitful arena in which to foster and study agency, control, and autonomy is in the area of medication use. Standard care for most severe mental disorders includes psychoactive medications (American Psychiatric Association, 1994b; 1997), yet many people with mental (and other) disorders do not take medications as prescribed (Bebbington, 1995; Kampman & Lehtinen, 1999). Clinicians may interpret non-compliance as symptomatic of mental illness, yet research describing medication use among patients with medical problems suggests that non-compliance may be an important method for individuals to assert control over the disorder (Conrad, 1985). In coming to grips with being formerly “well” individuals, people with serious mental and physical illnesses experience a process of resistance and self-negotiation about medication use (Carder, Vuckovic, & Green, 2003; Karp, 1996). Clinicians aware and accepting of these processes have begun to recognize the importance of these negotiated adjustments, and to accept a more collaborative role that includes education about medications, working together with consumers to develop plans for medication use, and facilitating consumer-to-consumer teaching and learning. These approaches will likely foster more consistent and helpful medication use (Diamond, 1983; Diamond & Little, 1984), better clinician-consumer relationships, enhanced capacities among consumers, and more comprehensive and speedier recoveries. They also provide an opportunity for researchers to examine different approaches and timing for fostering such collaborative efforts.

Competence and Dysfunction

Competence and dysfunction coexist in all individuals, developing and changing over time (Davidson & Strauss, 1995). They arise out of abilities, limitations, experience, and practice, and are affected by agency, control, and autonomy, for even when ability is present and people are experienced in a task, lack of opportunity to affect desired outcomes can produce dysfunction (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

An important part of the recovery process in chronic medical illness is developing an understanding of abilities and limitations (including those related to symptoms), cataloging them, and then making adaptations and decisions about day-to-day life management and long-term goals that respond to capabilities and weaknesses (Charmaz, 1991). These “taking stock” tasks have also been identified as part of the prime work of recovery from mental health problems (Davidson & Strauss, 1992; 1995; Leete, 1987).

Similarly, although it may seem obvious that the recovery process must build on competencies, mental health professionals may inadvertently overlook strengths and desires in response to concerns about risks associated with dysfunction (Davidson & Strauss, 1992; 1995). As a result, they may focus primarily on symptoms and weaknesses when, in reality, some or all of a person’s competencies may remain even when that person is at his or her sickest. Other competencies and dysfunctions likely wax and wane as a function of symptoms, life circumstances, and experiences. Unfortunately, clinicians may unknowingly undermine important aspects of the recovery process by ignoring competencies and focusing on dysfunction (Davidson, Hoge, Merrill, Rakfeldt, & Griffith, 1995). For example, a participant in one of our studies worked full-time, parented a teenager, and cared for a parent with dementia, despite ongoing symptoms most clinicians would rate as severe (feeling controlled by others, auditory hallucinations, receiving messages via the television). This participant took anti-psychotic medications but did not accept the diagnosis of schizophrenia. A clinician focused solely on symptoms and insight would conclude that this participant was neither recovered nor likely to be functioning adequately—despite having a full, meaningful, and reasonably happy life. In reality, this person was performing at a much higher level than many individuals without mental health problems. When asked, what this participant desired was not a reduction in symptoms, but a romantic partner. Stakeholders who look for, recognize, facilitate, understand, and catalog competencies, in addition to symptoms and dysfunctions, will have greater opportunities to enhance the recovery process than those who focus solely on dysfunction and illness-based identities.

Environment, Resources, Strains

In the proposed model, environment, resources, and strains take into account external factors as well as internal and external resources likely to influence the recovery process. These categories are necessarily broad and pervasive, ranging from the strains and limitations arising as a result of stigma and discrimination (Corrigan et al., 2003), to having a strong support system and close relationship with a romantic partner as resources. Mental health care can be incorporated as either a resource or a strain, depending on how it is delivered.

To make sense of these complex interrelationships, I rely on Hobfoll’s (Hobfoll, 1989) model of the ways in which an individual’s resources interact with the stress process—in this context, mental illness and its effects—and the methods people use to manage resources and resource loss. He defines resources as “objects [e.g., a home], personal characteristics [e.g., self-esteem, mastery], conditions [e.g., marriage, tenure], or energies [e.g., time, knowledge, social support, money—aids to the acquisition of other resources] that are valued by the individual or that serve as a means for attainment of these objects, personal characteristics, conditions, or energies” (p. 516). Stress is seen as a function of resource loss; stress resistance is bolstered by resources and resource gains; use of resources of one kind can offset resource loss of another. Most important for the study of recovery are his conceptualizations of (1) resource appraisal and evaluation (consistent with reports of the need for self-evaluation of strengths and weakness during recovery), (2) loss spirals (when resources are so low that stores are inadequate to offset additional loss—such as after repeated acute episodes or loss of employment and family ties), (3) resource building, which requires investment of other resources (particularly critical in situations where severely mentally ill people have lost most or all of their personal and financial resources), and (4) demoralization, low self-esteem, and depression resulting from loss of resources or lack of attainment of gains expected from investments in the future. Individuals with serious mental illnesses, already vulnerable, are also more likely to experience serious stressful and resource-sapping life events than are other people (e.g., to be victims of violence or stigma, to be homeless, to lose employment or the support of family members, or to have serious medical conditions). Taking this perspective, it seems clear that we cannot foster recovery if we do not understand how to help people maintain resources, how to facilitate resource development, or how to help people prevent and stop loss spirals. Yet, if our mental health care system has not failed utterly at these tasks, it has certainly functioned poorly.

Mental Health Care as a Resource or Strain

To understand how mental health care can facilitate recovery, we must understand the characteristics that can make it either a resource, or a strain. At their best, mental health services and mental health care providers are recovery- and wellness-focused, working closely with medical care providers, holding clients in mind as whole persons in control of their destinies, and providing a full range of support and educational systems at the ready. In this best-case scenario, clinicians, collaborating with mental health care consumers in producing health and recovery as consumers define them (Sullivan, 2003), foster improved functioning and enhanced competence, helping their clients to develop interdependencies with their families and friends while managing their own symptoms and lives (see Estroff for a utopian version (Estroff, 1999). In addition to teaching about symptoms and useful coping techniques, clinicians adopting this approach can foster hope and optimism as well as the agency and competencies necessary to create a meaningful life. Such an approach is more likely to produce the healthy teamwork and necessary social and financial supports that promote consultation during difficult times (Green et al., 2002), produce better outcomes, and facilitate recovery (Gehrs & Goering, 1994; Neale & Rosenheck, 1995; Onken et al., 2003; Solomon, Draine, & Delaney, 1995).

Unfortunately, providing comprehensive, empowering, integrated care of this type has been difficult to achieve in our fragmented, underfunded, mental health care system (Appelbaum, 2003; Mechanic, 2003). Too frequently, individuals and their families avoid care because of stigma, while those seeking care find access is limited or that needed services are not available (Dixon, 1999; New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003; Torrey et al., 2001). Symptom flares make it difficult to negotiate systems providing care, primary care is difficult to obtain or of poor quality (Levinson, Druss, Dombrowski, & Rosenheck, 2003), requests for help are denied or referred because of lack of insurance coverage or coexisting substance-abuse problems, and poor-quality involuntary hospitalization undermines individuals’ abilities to act on their own behalf. Institutional structures that increase access to and retention in treatment remain scarce, while patterns of clinical training and practice (e.g., clinical rotations and high staff turnover), and reimbursement, in combination with inadequate or bizarre systems of financing care, reduce continuity of care and increase strains on clinicians and consumers. Making matters worse, mental health services themselves are often fragmented, even though the developmental nature of recovery tasks creates a clear need for continuity of care (Chien, Steinwachs, Lehman, Fahey, & Skodol-Wilson, 2000; New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003). Finally, caregivers may be understandably excluded to ensure confidentiality (Marshall & Solomon, 2003), even though they, in the absence of effective psychiatric advance directives, may be the only available “continuity-of-care surrogates.”

It is in this context that caregivers, both formal and informal, develop, learn, and adapt to the circumstances in which they find themselves, affecting the balances of resources and strains that support or impinge on the person coping with mental illness. Many evolutions are possible: In the extreme, families and clinicians can burn out, give up, and abandon those for whom they provide care, or they can learn helpful methods of providing support and become the best of resources rather than the worst of strains. Too little attention has been paid to these relationships: Some research has addressed clinician and family burnout, but little has addressed positive changes or how to facilitate them among care providers. One important exception to this is the strong program of research evaluating the effects of family psychoeducation programs. These programs reduce relapse, improve relationships between consumers and their families (Dixon, Adams, & Lucksted, 2000), and appear to have great potential for fostering recovery. Nevertheless, such programs are not routinely available (Dixon et al., 2001). Recovery will be best served if we address not only clinical approaches but also the systems-based structures that interfere with good, recovery-oriented, mental health care.

Implications For Mental Health Care And Research

To date, recovery has mostly been a long-term, hit-or-miss process. Yet there is no reason to believe that we cannot foster and nurture it, speeding people towards more and longer periods of well-being and satisfaction. The question is, how? Researchers, practitioners, and consumers are beginning to identify many of the important elements of the recovery process (American Psychiatric Association, 1994b; 1997; Davidson & Strauss, 1995; Deegan, 1988; Fisher, 1994; Harrison et al., 2001; Lehman & Steinwachs, 1998; Liberman et al., 2002; Onken et al., 2003). But how and, perhaps more importantly, when, do we address these elements, and how do we intervene to increase positive and reduce negative cascades of events?

Answers to these questions must now become one of the critical tasks for those working to understand and foster recovery. If we conceive of recovery as a developmental process, the focus of treatment and research changes from that of solely identifying interventions and techniques that promote recovery generally (e.g., evidence-based practices) to how to collaborate with mental health care consumers so that they can direct their own care, and how to appropriately time approaches to collaboration, interventions, and services. In these ways, we can target our energies to produce the utmost benefit for the greatest number of people, while fostering, within individuals, the capacity to take advantage of all the possibilities for promoting recovery that come their way.

Toward this end, much can be gained by drawing on the work of other traditions. For example, motivational interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 1991) is, at its core, a method for fostering hope and optimism for behavior change and, correspondingly, agency and control. Work from the field of health promotion can provide frameworks for understanding where an individual is situated with respect to readiness for a particular change, as well as suggestions for how to facilitate increased readiness and, finally, the change itself (Prochaska et al., 1994). Developmental psychology and life-course studies can help us to identify normal developmental tasks that may have been delayed or disrupted by the onset of mental illness or its acute flare-ups, and suggest appropriate remediation, necessary prerequisites, and timing for specific interventions. Cognitive behavioral therapy techniques may be helpful in fostering optimism (Peterson, 2000), and should also have applicability in promoting agency.

I cannot emphasize enough, however, the importance of involving consumers in assessments of their own lives, treatment process, and recovery, and to do so from the beginning, in global terms, with regard to specific domains, and to the greatest extent possible. Some argue that evidenced-based, technical approaches to treatment are most appropriate and effective for individuals severely affected by their mental health problems, and that person-directed approaches are more appropriate as individuals progress toward recovery (Frese et al., 2001). Such transitional approaches, besides not having been evaluated for effectiveness, appear to conflict with the need to develop agency and control very early in the recovery process. More importantly, consumers may desire an entirely different process. It is time to address these questions empirically, learn what consumers of mental health care prefer and find most helpful, and find common ground among all stakeholders.

Finally, I do not believe that it is possible to foster recovery with a paternalistic attitude or approach. To the extent that clinicians want to be a part of the recovery process, they should be involved as caring, hopeful, collaborators and team members, rather than as (even benevolent) dictators of that process. One of our research participants described his much-loved psychiatrist as “like a brother to me.” A brotherly relationship is characterized by closeness, caring, common experience, and equality—we can learn a great deal from this simple statement.

Fostering Recovery-oriented Systems of Care

It is all well and good to make grand statements and suggestions about the forms that mental health care should take, but stakeholders work within constraints created by mechanisms of organizing and financing of care that can interfere with providing the kinds and range of services suggested by the proposed model (Scheid, 2003). Yet, despite these limitations, such problems are not insurmountable—systems of care can be adapted and changed, and communities empowered to enhance health (Syme, 2004), even if the process is difficult (see Jacobson’s (Jacobson, 2003) paper on reform in Wisconsin). Clinicians can develop collaborative relationships with consumers and work to instill hope, even during the shortest encounters. The recent effort by the President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health (New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003), although short on details for achieving critical system changes, nevertheless argues for them, and more states are reconfiguring their systems of care to promote recovery (e.g., Beale & Lambric [1995]). At the least, recovery is now included in the lexicon; at best, systems of care are being changed. Finally, I believe we need to explore a series of questions ranging from those at the micro level to those at the system or macro level. I list some of them in Table 1, in hopes that others will help to find answers.

Table 1.

Questions for clinicians, researchers, and policy makers interested in fostering recovery and recovery-oriented treatment and funding systems.

| 1) How can clinicians help consumers learn the key tasks of “taking stock”? |

| 2) What are the best ways to facilitate hope, optimism, and agency throughout the recovery process? |

| 3) What are the circumstances that facilitate recovery-related “turning points” or personal decisions, and how can we foster them? |

| 4) How can we determine the best timing for supporting meaningful activities such as employment, or interventions designed to promote other recovery-related factors? |

| 5) How can we minimize damage to agency, autonomy, control, hope, and optimism, if hospitalization or incarceration cannot be avoided? |

| 6) What kinds of support systems, formal and informal, are most likely to promote recovery, and how can we encourage their growth and development? |

| 7) How can we facilitate resource development and prevent resource loss (particularly loss spirals)? |

| 8) What kind of systems for organizing and financing care will best promote principles of treatment most important to the recovery process? |

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the following people for providing comments on earlier drafts of this paper: Beckie Child, Pat Risser, Michael Polen, Gary Miranda, Jennifer Pelt Wisdom, Kevin Bruce, and Kim Hopper. I would also like to thank Robert Paulson, Sue Estroff, and Kathy Charmaz, who gave generously of their time early in the development of the model, and to the anonymous reviewers of National Institute of Mental Health grant MH62321, Recoveries from Severe Mental Illness, which has also supported part of this work. Finally, I want to thank the Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research, for providing support when I first began thinking about recovery.

References

- Ahern L, Fisher D. Personal Assistance in Community Existence. Lawrence, Masschusetts: National Empowerment Center, Inc; 1999. pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht GL, Devlieger PJ. The disability paradox: high quality of life against all odds. Social Science and Medicine. 1999;48:977–988. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00411-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) First ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994a. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder. American Psychiatric Association. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994b;151:1–36. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.12.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. American Psychiatric Association. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:1–63. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.4.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angst J, Sellaro R. Historical perspectives and natural history of bipolar disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2000;48:445–457. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00909-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony WA. Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service systems in the 1990s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1993;16:11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony WA, Liberman RP. The practice of psychiatric rehabilitation: historical, conceptual, and research base. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1986;12:542–559. doi: 10.1093/schbul/12.4.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum PS. Presidential address: Re-envisioning a mental health system for the United States. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1758–1762. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.10.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beale V, Lambric T. The recovery concept: Implementation in the mental health system. Ohio Department of Mental Health; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bebbington PE. The content and context of compliance. International Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1995;9(Suppl 5):41–50. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199501005-00008. 41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA. 2002;288:2469–2475. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carder PC, Vuckovic N, Green CA. Negotiating medications: Patient perceptions of long-term medication use. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 2003;28:409–417. doi: 10.1046/j.0269-4727.2003.00511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter DM, Mackinnon A, Copolov DL. Patients' strategies for coping with auditory hallucinations. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1996;184:159–164. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199603000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Good days, bad days: The self in chronic illness and time. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Discoveries of self in illness. In: Dietz ML, Prus R, Shaffir W, editors. Doing Everyday Life: Ethnography as Human Lived Experience. Mississauga, Ontario: Copp Clark Longman Ltd; 1994. pp. 226–242. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. The body, identity and self: Adapting to impairment. Sociological Quarterly. 1995;36:657–680. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. From the "Sick Role" to Stories of Self. In: Contrada RS, Ashmore RD, editors. Self, Social Identity and Physical Health: Interdisciplinary Explorations. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999. pp. 209–239. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Experiencing chronic illness. In: Albrecht GL, Fitzpatrick R, Scrimshaw S, editors. Handbook of Social Studies and Medicine. London: Sage Publishing; 2000. pp. 277–292. [Google Scholar]

- Chien CF, Steinwachs DM, Lehman A, Fahey M, Skodol-Wilson H. Provider continuity and outcomes of care for persons with schizophrenia. Mental Health Services Research. 2000;2:201–211. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad P. The meaning of medications: another look at compliance. Social Science & Medicine. 1985;20:29–37. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(85)90308-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corin E, Lauzon G. Positive withdrawal and the quest for meaning: the reconstruction of experience among schizophrenics. Psychiatry. 1992;55:266–278. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1992.11024600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P, Thompson V, Lambert D, Sangster Y, Noel JG, Campbell J. Perceptions of discrimination among persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54:1105–1110. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.8.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L, Hoge MA, Merrill ME, Rakfeldt J, Griffith EE. The experiences of long-stay inpatients returning to the community. Psychiatry. 1995;58:122–132. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1995.11024719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L, McGlashan TH. The varied outcomes of schizophrenia. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;42:34–43. doi: 10.1177/070674379704200105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L, Strauss JS. Sense of self in recovery from severe mental illness. British Journal of Medical Psychology. 1992;65:131–145. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1992.tb01693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L, Strauss JS. Beyond the biopsychosocial model: integrating disorder, health, and recovery. Psychiatry. 1995;58:44–55. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1995.11024710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deegan PE. Recovery: The lived experience of rehabilitation. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1988;11:11–19. [Google Scholar]

- DeSisto MJ, Harding CM, McCormick RV, Ashikaga T, Brooks GW. The Maine and Vermont three-decade studies of serious mental illness. I. Matched comparison of cross-sectional outcome. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1995a;167:331–342. doi: 10.1192/bjp.167.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSisto MJ, Harding CM, McCormick RV, Ashikaga T, Brooks GW. The Maine and Vermont three-decade studies of serious mental illness: II. Longitudinal course comparisons. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1995b;167:338–342. doi: 10.1192/bjp.167.3.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond RJ. Enhancing medication use in schizophrenic patients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1983;44:7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond RJ, Little ML. Utilization of patient expertise in medication groups. Psychiatry Quarterly. 1984;56:13–19. doi: 10.1007/BF01324628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E. Subjective well being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist. 2000;55:34–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L. Providing services to families of persons with schizophrenia: present and future. Journal of Mental Health Policy & Economics. 1999;2:3–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-176x(199903)2:1<3::aid-mhp31>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L, Adams C, Lucksted A. Update on family psychoeducation for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 2000. 2000;26(1):5–20. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L, McFarlane WR, Lefley H, Lucksted A, Cohen M, Falloon I, et al. Evidence-based practices for services to families of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:903–910. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.7.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton WW, Mortensen PB, Herrman H, Freeman H, Bilker WB, Burgess P, et al. Long-term course of hospitalization for schizophrenia: Part I. Risk for rehospitalization. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1992;18:217–228. doi: 10.1093/schbul/18.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estroff SE. Self, identity, and subjective experiences of schizophrenia: in search of the subject. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1989;15:189–196. doi: 10.1093/schbul/15.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estroff SE. A harmony in three parts: Utopian treatment for schizophrenia. New Directions in Mental Health Services. 1999:13–19. doi: 10.1002/yd.23319998304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher DB. Health care reform based on an empowerment model of recovery by people with psychiatric disabilities. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1994;45:913–915. doi: 10.1176/ps.45.9.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frese FJ, Stanley J, Kress K, Vogel-Scibilia S. Integrating evidence-based practices and the recovery model. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:1462–1468. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.11.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehrs M, Goering P. The relationship between the Working Alliance and rehabilitation outcomes of schizophrenia. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1994;18:43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin MJ, Swendsen J, Heller TL, Hammen C. Relapse and impairment in bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:1635–1640. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.11.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green CA, Vuckovic NH, Firemark AJ. Adapting to psychiatric disability and needs for home- and community-based care. Mental Health Services Research. 2002;4:29–41. doi: 10.1023/a:1014045125695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman LS, Harrow M, Goldberg JF, Fichtner CG. Outcome of schizoaffective disorder at two long-term follow-ups: comparisons with outcome of schizophrenia and affective disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;148:1359–1365. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.10.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding CM, Brooks GW, Ashikaga T, Strauss JS, Breier A. The Vermont longitudinal study of persons with severe mental illness, I: Methodology, study sample, and overall status 32 years later. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1987a;144:718–726. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.6.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding CM, Brooks GW, Ashikaga T, Strauss JS, Breier A. The Vermont longitudinal study of persons with severe mental illness, II: Long-term outcome of subjects who retrospectively met DSM-III criteria for schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1987b;144:727–735. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.6.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding CM, Zahniser JH. Empirical correction of seven myths about schizophrenia with implications for treatment. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Supplement. 1994;384:140–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb05903.x. 140–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding CM, Zubin J, Strauss JS. Chronicity in schizophrenia: fact, partial fact, or artifact? Hospital & Community Psychiatry. 1987;38:477–486. doi: 10.1176/ps.38.5.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding CM, Zubin J, Strauss JS. Chronicity in schizophrenia: revisited. British Journal of Psychiatry Supplement. 1992:27–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haro JM, Eaton WW, Bilker WB, Mortensen PB. Predictability of rehospitalization for schizophrenia. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 1994;244:241–246. doi: 10.1007/BF02190376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison G, Hopper K, Craig T, Laska E, Siegel C, Wanderling J, et al. Recovery from psychotic illness: a 15- and 25-year international follow-up study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;178:506–517. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.6.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty JD, Baldessarini RJ, Tohen M, Waternaux C, Oepen G. One hundred years of schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of the outcome literature. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:1409–1416. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.10.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources. A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist. 1989;44:513–524. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.3.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann H, Kupper Z. Facilitators of psychosocial recovery from schizophrenia. International Review of Psychiatry. 2002;14:293–302. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson N. Defining recovery: an interactionist analysis of mental health policy development, Wisconsin 1996–1999. Qualitative Health Research. 2003;13:378–393. doi: 10.1177/1049732302250334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampman O, Lehtinen K. Compliance in psychoses. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1999;100:167–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb10842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karp DA. Speaking of sadness: Depressions, disconnection, and the meanings of illness. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Foster CL, Saunders WB, Stang PE. Social consequences of psychiatric disorders, I: Educational attainment. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:1026–1032. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam D, Wong G. Prodromes, coping strategies, insight and social functioning in bipolar affective disorders. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:1091–1100. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW. Toward a psychology of positive youth development. American Psychologist. 2000;55:170–183. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leete E. The treatment of schizophrenia: a patient's perspective. Hospital & Community Psychiatry. 1987;38:486–491. doi: 10.1176/ps.38.5.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM. At issue: Translating research into practice: The schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1998;24:1–10. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson MC, Druss BG, Dombrowski EA, Rosenheck RA. Barriers to primary medical care among patients at a community mental health center. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54:1158–1160. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.8.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A, Ventura J, Gutkind D. Operational criteria and factors related to recovery from schizophrenia. International Review of Psychiatry. 2002;14:256–272. [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz FE. Modeling processes in recovery from mental illness: Relationships between symptoms, life satisfaction, and self-concept. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2001;42:79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall T, Solomon P. Professionals' responsibilities in releasing information to families of adults with mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54(12):1622–1628. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.12.1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massimini F, Delle Fave A. Individual development in a bio-cultural perspective. American Psychologist. 2000;55:24–33. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D. Policy challenges in improving mental health services: some lessons from the past. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54:1227–1232. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.9.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York: Guilford Press; 1991. Motivational interviewing. [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Becker DR, Torrey WC, Xie H, Bond GR, Drake RE, et al. Work and nonvocational domains of functioning in persons with severe mental illness: a longitudinal analysis. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 1997;185:419–426. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199707000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Valentiner DP, Agresta J. Coping with negative symptoms of schizophrenia: patient and family perspectives. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1997;23:329–339. doi: 10.1093/schbul/23.2.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJL, Lopez AD. The global burden of disease in 1990: Final results and their sensitivity to alternative epidemiological perspectives, discount rates, age-weights and disability weights. In: Murray CJL, Lopez AD, editors. The Global Burden of Disease. Harvard School of Public Health; 1996. pp. 247–293. [Google Scholar]

- National Advisory Mental Health Council. Health care reform for Americans with severe mental illnesses: report of the National Advisory Mental Health Council. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150:1447–1465. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.10.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale MS, Rosenheck RA. Therapeutic alliance and outcome in a VA intensive case management program. Psychiatric Services. 1995;46:719–721. doi: 10.1176/ps.46.7.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neugebauer R. Mind matters: the importance of mental disorders in public health's 21st century mission. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89:1309–1311. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. Achieving the promise: Transforming mental health care in America. Rockville, MD: DHHS; 2003. (Rep. No. DHHS Pub. No. SMA-03-3831). [Google Scholar]

- Onken SJ, Dumont JM, Ridgway P, Dornan DH, Ralph RO. Phase One Research Report: A National Study of Consumer Perspectives on What Helps and Hinders Mental Health Recovery. Alexandria, VA: National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD) National Technical Assistance Center (NTAC); 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C. The future of optimism. American Psychologist. 2000;55:44–55. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope AM, Tarlov AR. Disability in America: Toward a National Agenda for Prevention. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, Rossi JS, Goldstein MG, Marcus BH, Rakowski W, et al. Stages of change and decisional balance for 12 problem behaviors. Health Psychology. 1994;13:39–46. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakfeldt J, Strauss JS. The low turning point. A control mechanism in the course of mental disorder. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 1989;177:32–37. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198901000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralph RO, Risman J, Kidder KA, Campbell J, Caras S, Dumont J, et al. Recovery advisory group recovery model: A work in process, May, 1999. 2000 http://www.mhsip.org/recovery/ [On-line]. Available: http://www.mhsip.org/recovery/ [Google Scholar]

- Rice DP, Miller LS. The economic burden of schizophrenia: Conceptual and methodological issues, and cost estimates. In: Moscarelli M, Rupp A, Sartorius N, editors. Handbook of Mental Health Economics and Health Policy: Volume 1, Schizophrenia. West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Rice DP, Miller LS. Health economics and cost implications of anxiety and other mental disorders in the United States. British Journal of Psychiatry Supplement. 1998:4–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russinova Z, Wewiorski NJ, Lyass A, Rogers ES, Massaro JM. Correlates of vocational recovery for persons with schizophrenia. International Review of Psychiatry. 2002;14:303–311. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist. 2000;55:68–78. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheid TL. Managed care and the rationalization of mental health services. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 2003;44:142–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz B. Self-detemination: The tyranny of freedom. American Psychologist. 2000;55:79–88. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP, Csikszentmihalyi M. Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist. 2000;55:5–14. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon P, Draine J, Delaney MA. The working alliance and consumer case management. Journal of Mental Health Administration. 1995;22:126–134. doi: 10.1007/BF02518753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaniol L, Koehler M, Hutchinson DS. The Recovery Workbook: Practical Coping and Empowerment Strategies for People with Psychiatric Disability. Boston, Massachusetts: Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Spaniol L, Wewiorski NJ, Gagne C, Anthony WA. The process of recovery from schizophrenia. International Review of Psychiatry. 2002;14:327–336. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss JS. Mediating processes in schizophrenia. Towards a new dynamic psychiatry. British Journal of Psychiatry Supplement. 1989:22–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan M. The new subjective medicine: taking the patient's point of view on health care and health. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56:1595–1604. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syme SL. Social determinants of health: the community as an empowered partner. Preventing Chronic Disease: Public Health Research, Practice, & Policy [On-line] 2004 Available: www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2004/jan/syme.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Taylor SE, Brown JD. Illusion and well-being: a social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103:193–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Kemeny ME, Reed GM, Bower JE, Gruenewald TL. Psychological resources, positive illusions and health. American Psychologist. 2000;55:99–109. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torgalsboen AK, Rund BR. Lessons learned from three studies of recovery from schizophrenia. International Review of Psychiatry. 2002;14:312–317. [Google Scholar]

- Torrey WC, Drake RE, Dixon L, Burns BJ, Flynn L, Rush AJ, et al. Implementing evidence-based practices for persons with severe mental illnesses. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:45–50. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend W, Boyd S, Griffin G, Hicks PL. Emerging Best Practices in Mental Health Recovery. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio Department of Mental Health; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Center for Mental Health Services; National Institutes of Health; National Institute of Mental Health. Mental health: A report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Maryland: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge LM, Jette AM. The disablement process. Social Science and Medicine. 1994;38:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90294-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Korff M, Gruman J, Schaefer C. Collaborative management of chronic illness. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1997;127:1097–1102. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-12-199712150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner R. Recovery from Schizophrenia. 2nd ed. London: Routledge; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehorn D, Brown J, Richard J, Rui Q, Kopala L. Multiple dimensions of recovery in early psychosis. International Review of Psychiatry. 2002;14:273–283. [Google Scholar]

- Whitney E. Mania as spiritual emergency. Psychiatric Services. 1998;49:1547–1548. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.12.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiersma D, Nienhuis FJ, Slooff CJ, Giel R. Natural course of schizophrenic disorders: a 15-year followup of a Dutch incidence cohort. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1998;24:75–85. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SL, Ensing DS. Exploring recovery from the perspective of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 1999;22:219–231. [Google Scholar]