Abstract

A low molecular weight polyethyleneimine (PEI 1.8 kDa) was modified with dioleoylphosphatidylethanolamine (PE) to form the PEI-PE conjugate investigated as a transfection vector. The optimized PEI-PE/pDNA complexes at an N/P ratio of 16 had a particle size of 225 nm, a surface charge of +31 mV, and protected the pDNA from the action of DNase I. The PEI-PE conjugate had a critical micelle concentration (CMC) of about 34 μg/ml and exhibited no toxicity compared to a high molecular weight PEI (PEI 25 kDa) as tested with B16-F10 melanoma cells. The B16-F10 cells transfected with PEI-PE/pEGFP complexes showed protein expression levels higher than with PEI-1.8 or PEI-25 vectors. Complexes prepared with YOYO 1-labeled pEGFP confirmed the enhanced delivery of the plasmid with PEI-PE compared to PEI-1.8 and PEI-25. The PEI-PE/pDNA complexes were also mixed with various amounts of micelle-forming material, polyethylene glycol (PEG)-PE to improve biocompatibility. The resulting particles exhibited a neutral surface charge, resistance to salt-induced aggregation, and good transfection activity in the presence of serum in complete media. The use of the low-pH-degradable PEG-hydrazone-PE produced particles with transfection activity sensitive to changes in pH consistent with the relatively acidic tumor environment.

Keywords: Polyethyleneimine, Transfection, pH-sensitive, Micelles, Cancer

1. Introduction

Among various synthetic vectors, polyethyleneimines (PEIs), are most widely used for gene delivery due to their high nucleic acid condensing capability, ability for endosomal escape [1–3], and nuclear localization capability [4]. Due to their high positive charge density, PEIs can compact DNA into condensed particles by electrostatic interaction, and they have shown promising transfection efficacy both in vitro and in vivo [1,5–8]. The endosomal escape activity of PEIs is due to their high protonation in the acidic endosomal environment, which causes swelling and rupture of the endosomes [1–3]. However, toxicity of the PEIs and undesirable interactions with blood components due to the high positive charge limit their in vivo applications [8–10].

PEIs are available in a wide range of molecular weights (MW) from 423 Da to 800 kDa and with different branching degree (from linear to branched) [5]. Generally, high MW, branched PEIs have high transfection efficiency but also high toxicity due to high cationic charge [11–13]. By contrast, low MW PEIs are less toxic but less efficient as gene delivery agents [14,15]. Many efforts have been directed towards creating PEI derivatives combining higher transfection efficacy and good biocompatibility. One such approach is PEI modification with hydrophobic moieties, such as lipids. Since lipids are the main component of cell membrane, modification with hydrophobic moieties may result in additional hydrophobic interaction between polyplexes and cell membranes, which in turn would facilitate the delivery of a payload into cells. Various hydrophobic modifications have been tried, including modification with cholesterol [14–18], myristate [16], dodecyl iodide [19], hexadecyl iodide [19], palmitic acid [20,21], oleic acid [22], stearic acid [22,23], and phosphatidylcholine [24,25].

To achieve high transfection efficiency, excess polycation is usually complexed with nucleic acid resulting in complexes with a net positive charge. It is now understood that neutral particles are preferred since body enzymes recognize the charge on foreign particles and eliminate them [26]. Various attempts have been made to inhibit the interaction of serum proteins with DNA-carrier complexes, such as the self-assembly of DNA and block copolymers with the cationic block of PEI attached to poly(N-2-hydroxypropyl methacrylamide), poly(acrylic acid) [27,28], and polyethylene glycol (PEG) [29,30]. Certain success was attributed to the improved biophysical properties of resulting complexes associated with decreased surface charge, lower toxicity, and reduced non-specific binding to cells and serum proteins [27,28]. Although in few instances PEGylation could improve gene transfer efficiency [31], in most cases, stable PEGylation of polyplexes strongly reduces the transfection efficiency [26,27,32].

Ideally, a stable PEG coating is required for longer blood circulation, to avoid the exposure of positive surface charge, and to prevent particle aggregation. After a gene delivery carrier reaches target cells, however, the PEG chain becomes unnecessary or even undesireable. Removal of the PEG shielding can allow for more efficient cellular association of the complex due to exposure of cationic charges or provoke efficient endosomal escape.

One of the interesting aspects of tumor physiology is the acidified interstitial pH compared to the normal physiological pH. Thus, shielding of the DNA/PEI complex when in the systemic circulation with PEG, which is capable of detaching at lowered pH values exposing thus a DNA complex only at the tumor sites could serve as an attractive solution. The use of pH-sensitive PEG shields has already been demonstrated as a very encouraging solution to overcome the ‘PEG-dilemma’ [33–38].

Recently, we have demonstrated that phosphatidylcholine-modified low MW PEI effectively condensed and protected siRNA and plasmid DNA from enzymatic degradation and improved its uptake by cancer cells [24,25]. Further encapsulation of these complexes into micelle-like nanoparticles (MNPs) showed transfection efficacy similar to that of PEI-lipid complexes but improved biocompatibility, including the absence of in vitro or in vivo acute toxicity and prolonged blood circulation [24,25]. In another study we have synthesized PEI-lipid conjugate by modification of low MW PEI with dioleoylphosphatidylethanolamine (PE) for siRNA delivery to downregulate P-gp and overcome doxorubicin resistance in multidrug resistance MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. The PEI-PE conjugate enhanced the transfection efficacy of low MW PEI, which was otherwise totally ineffective. These complexes were further encapsulated in MNPs and showed improved biocompatibility. Moreover, the combination of doxorubicin and P-gp silencing formulations led to a 2-fold increase of doxorubicin uptake and cytotoxicity in resistant cells [39].

In the current study, we evaluated the PEI-PE conjugate for the delivery of plasmid DNA and characterized it for its various physicochemical properties, cell cytotoxicity, and transfection efficiency in a cancer cell line. The PEI-PE/DNA complexes were further encapsulated into low-pH degradable PEG-Hydrazone (Hz)-PE micelles with tunable transfection efficiency and improved biocompatibility.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

All materials were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich unless otherwise stated. Branched polyethylenimines (PEI) with a molecular weight of 1.8 kDa and 25 kDa were purchased from Polysciences, Inc. (Warrington, PA). 1,2-disrearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy (polyethylene glycol)-2000] (PEG2000-PE), 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(glutaryl) (NGPE) and phosphatidylthioethanolamine (DPPE-SH) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). 4-(4-N-Maleimidophenyl)butyric acid hydrazide-HCl (MPBH) from Pierce (Rockford, IL). The CellTiter-Blue® Cell Viability Assay was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). Plasmid DNA constructs containing enhanced green fluorescence protein reporter gene (pEGFP-N1) were purchased from Elim Biopharmaceuticals, Inc. (Hayward, CA). YOYO-1 iodide was purchased from Invitorgen (Carlsbad, CA). mPEG-SH was from Laysan Bio Inc. (Arab, AL).

2.2. Synthesis of PEI-PE conjugate

The PEI-PE conjugate was synthesized from PEI 1.8 kDa and NGPE. NGPE (24.5 mg, 27.8 μM) in chloroform at a stock solution concentration of 25 mg/ml, was activated with N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide HCl (EDCI) (16 mg, 83.3 μM) and N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) (10 mg, 83.3 μM) in the presence of 15 μl of triethylamine at room temperature for 4 h. PEI 1.8 kDa (50 mg, 27.8 μM) was dissolved in chloroform at a concentration of 50 mg/ml. The activated acid solution was added drop-wise into the PEI solution while stirring and the mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. The chloroform was evaporated in a rotary evaporator under reduced pressure and freeze-dried to remove traces of chloroform. The residue was suspended in 2 ml of deionized water (dH2O) and purified by dialysis (MWCO 2000 Da) against dH2O and freeze-dried. PEI-PE was dissolved in CDCl3 and characterized by 1H NMR using a Varian 500 MHz spectrophotometer.

2.3. Synthesis of PEG2000-Hz-PE

PEG2000-Hz-PE was synthesized as reported in [40]. Briefly, mPEG2000-SH (17 μmol) in phosphate buffer, pH 7.2 was mixed with a 2.33 M excess of MPBH and incubated for 3h at room temperature. The excess MPBH was separated from the product by dialysis (MWCO 2000 Da) against dH2O. The product obtained was freeze-dried and stored as a chloroform solution at −80 °C.

Phosphatidylthioethanolamine (DPPE-SH, 51 μmol), in chloroform was mixed with a 2 M excess of 4-acetyl phenyl maleimide (APMal) in the presence of a 3 M excess of triethylamine over the lipid. The reaction mixture was incubated overnight at room temperature. The solvent was evaporated, and the residue re-dissolved in chloroform. The product was separated on a silica gel (240–360 μm) column using chloroform/methanol mobile phases 5:0, 4.5:0.5 and 0:5.0 v/v. The fractions containing the product were identified by the TLC analysis (using 0.25 mm layer thickness, 2.5 × 7.5 cm silica plates with UV indicator, EMD Chemicals, 60F-254) and a mobile phase of chloroform/methanol (80:20% v/v), phospholipid or the conjugates were visualized by the phosphomolybdic acid. The product was stored as a chloroform solution at −80 °C.

Then, 1.1 M excess of the activated phospholipid, was reacted with acyl hydrazide-derivatized PEG in chloroform at room temperature. After the overnight stirring, chloroform was evaporated under the reduced pressure. The PEG2000-Hz-PE conjugate was purified using the size exclusion chromatography on Sepharose CL4B (40–165 μm).

2.4. Analysis of pH-sensitivity of PEG2000-Hz-PE

The pH-sensitivity of the PEG2000-Hz-PE conjugate was analyzed using the size exclusion chromatograpy [40]. PEG2000-Hz-PE solution in chloroform was evaporated under argon to form a thin film. The film was hydrated with a buffer solution (phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 or pH 5.0) at 10 mg/ml to form micelles. The micelles were incubated for 3 h at 37 °C. The degradation of the conjugate was followed by the HPLC using a Shodex KW-804 size exclusion column. The elution buffer was pH 7.0 phosphate buffer (100 mM phosphate, 150 mM sodium sulphate), at 1.0 ml/min. The micelle peak was detected at 227 nm.

2.5. CMC

The CMC value of the polymer (PEI 1.8 or PEI-PE) was estimated by the standard pyrene method [41]. Briefly, tubes containing 1 mg crystals of pyrene were prepared. To these crystals, a 0.25–0.001 mg/ml solution of polymer in dH2O was added. The mixtures were incubated for 24 h with shaking at room temperature. Free pyrene was removed by filtration through 0.2 μm polycarbonate membranes. The fluorescence of filtered samples was measured at the excitation wavelength of 339 nm and emission wavelength of 390 nm using an F-2000 fluorescence spectrometer (Hitachi, Japan). CMC values correspond to the concentration of the polymer at which the sharp increase in pyrene fluorescence in solution is observed.

2.6. Complexation of plasmid DNA with PEI-PE

A fixed amount of plasmid DNA (1.5 μg) and varying amounts of PEI-PE were diluted separately in equal volumes of HEPES Buffered Glucose (HBG) (10 mM HEPES, 5% D-glucose). The PEI-PE solution was added to the DNA solution (final volume 20 μl), vortexed and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The resulting polyplexes were analyzed by the agarose gel electrophoresis using the E-Gel electrophoresis system (Invitrogen Life Technologies). A precast 0.8% E-Gel cartridge was pre-run for 2 min at 60 V and 500 mA followed by loading of 1 μg of pDNA. The amine/phosphate (N/P) ratio was calculated by assuming that 43.1 g/mol corresponds to each repeating unit of PEI containing one amine, and 330 g/mol corresponds to each repeating unit of DNA containing one phosphate.

Whenever required, the complexes were further mixed with different amounts of PEG2000-PE or PEG2000-Hz-PE (20 μl, previously incubated in phosphate buffer, pH 5.0 or pH 7.4 for 3 h at 37 °C) and incubated for an additional 30 min at room temperature.

2.7. DNase I protection assay

The PEI-PE/DNA complexes (N/P 16) prepared as mentioned above were incubated with of DNase I (1unit/μg of DNA, Promega Corp., Madison, WI) for 30 min at 37 °C. The digestion was stopped by the addition of EGTA and EDTA to a final concentration of 5 mM. To dissociate the DNA molecules from complexes, heparin (50 units/μg of DNA) was added, the mixtures were further incubated for 30 min at 37°C, and the products were analyzed on a 0.8% precast agarose gel.

2.8. Size and zeta potential

The size and zeta potential of complexes were determined by the quasi-electric light scattering (QELS) using a Zeta Plus Particle Analyzer (Brookhaven Instruments Corp, Santa Barbara, CA) equipped with the Multi-Angle Option at 23 °C at an angle of 90°. The complexes were diluted in HBG (for size analysis) or in deionized water (for zeta potential measurement) to obtain an optimal scattering intensity.

2.9. Stability against salt-induced aggregation

To investigate the stability of the complexes against the salt-induced aggregation, NaCl (5 M) was added to the complexes in HBG to a final concentration of 0.15 M and the size of the complexes was measured as described above.

2.10. Cell culture

B16F10 cells were grown at 37 °C in 5% CO2 and 95% humidity in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 2 mM glutamine. The cell cultures were detached by trypsinization with 0.5% trypsin in PBS containing 0.025% EDTA.

2.11. Cytotoxicity

Approximately 4 × 103 B16F10 cells were seeded in 96-well plates. After 24 h, the cells were treated with DMEM (100 μl) containing a serial dilution of each polymer up to 50 μg/ml. After 4 h incubation, the cells were washed twice with DMEM and incubated in 100 μl of complete media. After 48 h incubation, 20 μl of CellTiter Blue was added to each well, and the plates were re-incubated for 2 h. The fluorescence was measured at the excitation and emission wavelength of 560 nm and 590 nm, respectively using a 96-well plate reader (Multiscan MCC/340, Fisher Scientific Co). Relative cell viability was calculated with cells treated only with the medium as a control.

2.12. Cell uptake studies

For cell uptake studies, DNA was labeled with YOYO-1 at a dye-to-base pair ratio of 300. Cells were seeded into 12 well plates at a density of 70 × 103 cells per well. For confocal microscopy studies, cells were seeded onto coverslips. Cells were allowed to attach for 24 h.

The complexes were prepared as described previously but with-labeled plasmid (DNA-Y). The complexes (equivalent to 1.5 μg of DNA-Y) were mixed with 0.5 ml of DMEM. Old medium was removed, cells were washed with DMEM and DNA-Y complexes were added to cells. The plates were then incubated for 4 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2.

For flow cytometry, at the end of the incubation period, the medium was removed, cells were washed with DMEM, trypsinized, and cell-associate fluorescence was quantified by Becton Dickinson FACScan™ (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) at the emission wavelength of 520 nm (channel FL-1). The data analysis was performed using the CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson). The live cells were gated on the basis of forward and side scatter. A total of 10,000 events were acquired for each sample.

For confocal microscopy study, at the end of the incubation period, the medium was removed, and cells were washed twice with the sterile PBS followed by the fixation of the cells with 4% paraformaldehyde (15 min at RT). Hoechst 33342 (1 μg/ml) was added to the cells for 15 min, and cells were washed twice with sterile PBS. A Zeiss Confocal LSM 700 was used to obtain DIC and fluorescent images of cells.

2.13. In vitro transfection

All transfection experiments were carried out with B16F10 cells. In a typical experiment, 12 well plates were seeded with 35 × 103 cells/well in complete medium 24 h before transfection. The complexes (equivalent to 1.5 μg of DNA) were mixed with 0.5 ml of DMEM or complete media. Old medium was removed from the wells, cells were washed with DMEM or complete medium, and DNA complexes were added to cells. The plates were incubated for 4 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. At the end of the incubation period, the medium was removed; cells were washed with complete medium, and incubated with 1 ml of the complete medium for 48 h. The medium was removed, and the cells were washed with complete medium, trypsinized and GFP expression was quantified by Becton Dickinson FACScan™ (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) at the emission wavelength of 520 nm (channel FL-1). The data analysis was performed as described above.

2.14. Statistical analysis

The results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (S.D.), and comparisons between the groups were made using Student’s t test; p-values less than 0.05 were considered to indicate a significant difference.

3. Results

3.1. Synthesis and characterization of PEI-PE

The PEI-PE polymer was synthesized from NHS-activated DOPE and PEI-1.8. The final structure of the polymer was confirmed by 1H NMR. 1H NMR of PEI-PE in CDCl3: δ 0.88–0.91 (6H, t, 6H, (-CH2CH3)2, signal from DOPE), 1.3–1.31 (multiplate (m)), 1.6 (broad singlet (bs), 5H), 2.00–2.04 (m), 2.21–3.43 (m, from DOPE and PEI), 3.96 (bs), 4.13 (bs), 4.39–4.42 (doublet), 5.22–5.39 (m).

The PEI-PE polymer is amphiphilic in nature because PEI is water-soluble and hydrophilic while PE is hydrophobic. As the concentration increases, the PEI-PE polymer may assemble into micellar structures in aqueous media. To measure the concentration at which PEI-PE assembled into micelle-like structures, we measured the fluorescence values of different concentrations of PEI-PE in presence of the fixed amount of pyrene. The fluorescence value of pyrene significantly increases after its incorporation into hydrophobic core (i.e. when micelles are formed and pyrene incorporates into micellar core). Concentration of the PEI-PE polymer at which pyrene fluorescence increases corresponds to the CMC. The CMC of the PEI-PE polymer was found to be 0.034 mg/ml. This was different from the PEI-1.8 solutions, which gave pyrene absorbance similar to aqueous solutions, indicating minimal hydrophobicity of the native PEI.

3.2. Synthesis and characterization of PEG2000-Hz-PE

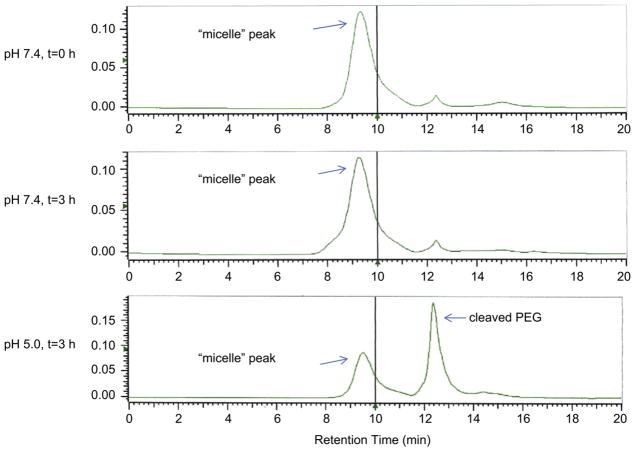

A HPLC chromatogram for PEG2000-Hz-PE is shown in Fig. 1. The micelle peak was observed at the retention time 9.4 min (micelle peak). The intact micelle peak was still observed after the incubation at pH 7.4 for 3 h. However, the area of the intact micelle peak was reduced with the appearance of a cleaved PEG peak after the incubation at pH 5.0 for 3 h. This reduction in the area of the intact micelle peak is indicative of the destruction of the micelle structure due to the loss of the PEG corona. Non-pH-sensitive micelles (PEG2000-PE) showed the same micelle peak at both pH values after incubation for 3 h (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

HPLC analysis of the pH-sensitive PEG2000-Hz-PE micelles after incubation at pH 7.4 or 5.0 at 37 °C for 3 h.

3.3. Physicochemical characteristics of DNA complexes

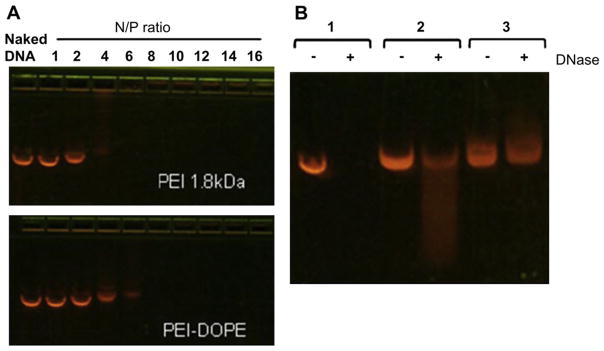

The complexes were prepared by mixing constant amounts of plasmid DNA with different amounts of polymer. An agarose gel electrophoresis was performed to detect the formation of complexes and the N/P ratio, at which the plasmid DNA was totally condensed by the polymer. The complex formation hinders the migration of DNA, retaining the DNA in the wells. The PEI-1.8 condensed the DNA at an N/P ratio higher than 6, while the PEI-PE polymer condensed the DNA at an N/P ratio higher than 8 (Fig. 2A). Thus, the modification of PEI with PE did not affect the condensation capacity of PEI-1.8 much.

Fig. 2.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of: A) PEI-PE/DNA complexes in comparison to PEI-1.8/DNA complexes at various N/P ratios; (B) complexes after treatment with DNAase. 1: naked DNA, 2: PEI-1.8/DNA (N/P 16), 3: PEI-PE/DNA (N/P 16).

The stability of the condensed DNA against the enzymatic degradation was evaluated by incubating the complexes with DNase I for 30 min at 37 °C. Naked DNA was completely degraded at these conditions (Fig. 2B). DNA complex with PEI-1.8 showed some degradation of DNA since a long smear corresponding to smaller DNA fragments was observed. The PEI-PE showed complete protection of the loaded-DNA against enzymatic degradation.

The particle size analysis data is presented in Table 1. The size of PEI-1.8/DNA complexes ranged from 177 to 225 nm. The size of the complexes decreased gradually as the N/P ratio increased. All complexes were positivelycharged with zeta potential of 20–24 mV. As an additional control, complexes were prepared with PEI-25, which is considered as the gold standard for PEI-based transfection. The PEI-25/DNA complexes exhibited a size of about 129 nm. Particle size of the complexes was also influenced markedly by N/P ratios. It is generally considered that DNA is condensed more tightly as the N/P ratio increases, leading to a smaller particle size [7,8].

Table 1.

Particle size and zeta potential of various complexes.

| Complexes (N/P ratio) | Size (nm ± S.D.) | Zeta potential (mV ± S.D.) |

|---|---|---|

| PEI 1.8 (8) | 225.3 ± 12.4 | 20.32 ± 2.3 |

| PEI 1.8 (10) | 223.5 ± 12.0 | 23.08 ± 0.8 |

| PEI 1.8 (12) | 205 ± 6.3 | 20.56 ± 6.46 |

| PEI 1.8 (16) | 170.3 ± 5.3 | 21.16 ± 5.36 |

| PEI 1.8 (16)a | >1000 | N/A |

| PEI 1.8 (20) | 177.2 ± 5.7 | 24.04 ± 1.86 |

| PEI25 (4) | 129.3 ± 5.2 | 21.32 ± 2.21 |

| PEI-PE (10) | 507.8 ± 24.6 | 17.58 ± 1.27 |

| PEI-PE (12) | 215 ± 11.9 | 25.34 ± 1.21 |

| PEI-PE (14) | 223.17 ± 10.9 | 27.48 ± 1.23 |

| PEI-PE (16) | 225.4 ± 9.4 | 31.28 ± 0.87 |

| PEI-PE (16)a | 304.5 ± 33.1 | N/A |

| PEI-PE (20) | 190.8 ± 7.5 | 34.03 ± 1.62 |

| PEI-PE (16)+PEG 2 | 238.5 ± 15.8 | 1.22 ± 1.38 |

| PEI-PE (16)+PEG2a | 230.7 ± 14.1 | N/A |

After incubation in 150 mM NaCl for 24 h at room temperature.

The size of the PEI-PE/DNA complexes ranged from 190 to 507 nm depending on the N/P ratio. The largest size of complexes was observed at the N/P ratio of 10. All the complexes were positively charged with a zeta potential in the range from 17 to 34 mV.

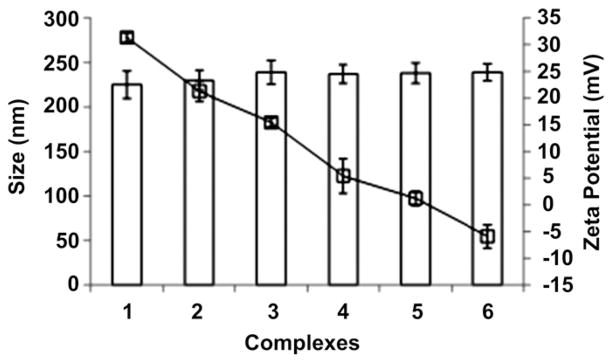

The PEI-PE/DNA complexes (N/P 16) were further coated with varying amounts of micelle-forming polymer, PEG2000-PE (Table 2). There was no significant increase in the size of complexes after the addition of PEG2000-PE (Fig. 3). However, there was a gradual reduction in zeta potential of complexes with increasing amounts of PEG2000-PE suggesting the latter provided shielding for the positive PEI-PE/DNA core (Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Formulation composition of PEI-PE/DNA (N/P 16) complexes with PEG2000-PE or PEG2000-Hz-PE.

| Formulation | PEG-PE micellar complexes. Weight ratio (PEI-PE: PEG-PE) | Formulation | PEG-Hz-PE micellar complexes. Weight ratio (PEI-PE: PEG-Hz-PE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEG 0.25 | 0.25 | – | – |

| PEG 0.5 | 0.5 | PEG-Hz 0.5 | 0.5 |

| PEG 1 | 1 | PEG-Hz 1 | 1 |

| PEG 2 | 2 | PEG-Hz 2 | 2 |

| PEG 5 | 5 | – | – |

Fig. 3.

Effect of PEG2000-PE on size and zeta potential of PEI-PE/DNA complexes. 1: PEI-PE N/P 16, and PEI-PE N/P 16 with 2: PEG 0.25, 3: PEG 0.5, 4: PEG 1, 5: PEG 2, 6: PEG 5.

The colloidal stability (stability against the salt-induced aggregation) of the complexes as indicated by the change in size was studied by incubating the complexes in 150 mM NaCl for 24 h at room temperature. The PEI-1.8/DNA complexes showed a size larger than 1000 nm (Table 1). The size of the PEI-PE/DNA complexes also increased from 225 to 304 nm. However, the size of PEI-PE/DNA complexes with PEG did not change significantly after 24 h (Table 1).

To study the shielding effect of the pH-sensitive PEG2000-Hz-PE, the polymer was pre-incubated at different pH (7.4 and 5.0), then added to the PEI-PE/DNA complexes (PEG-Hz 2, Table 2) and further incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The size of the resulting micellar complexes was 241 ± 11.7 nm, the complexes exhibited a near-neutral zeta potential of about −0.22 ± 1.3 mV, when complexes were mixed with the pH-sensitive polymer pre-incubated at pH 7.4. The near-neutral zeta potential indicated that the positively charged PEI is being shielded. The complexes mixed with pH-sensitive polymer pre-incubated at pH 5.0 had a positive zeta potential of about 15 ± 1.7 mV indicating loss of the shielding effect of PEG. The size of the complexes was 237 ± 16.3 nm. By contrast, the zeta potential of complexes shielded with PEG2000-PE (i.e. PEG 2) did not change significantly at either pH.

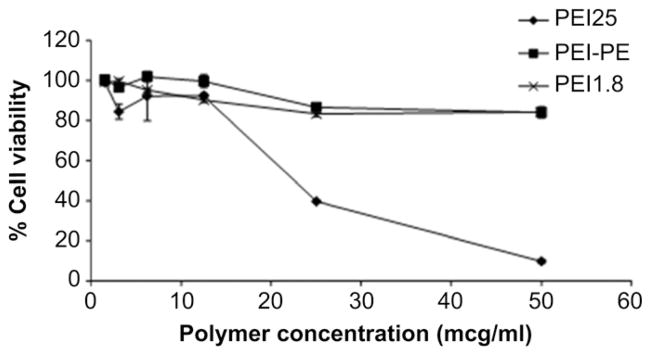

3.4. Cytotoxicity

High toxicity remains the major obstacle for most of the cationic transfection agents both in vitro and in vivo. PEI-25 was highly toxic. There was nearly complete cell death at its concentration of 50 μg/ml. However, PEI-PE and PEI-1.8 were relatively non-toxic to cells, which retained ≥ 90% viability (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

In vitro cytotoxicity of various tested polymers towards B16F10 cells.

3.5. Cellular uptake of the complexes

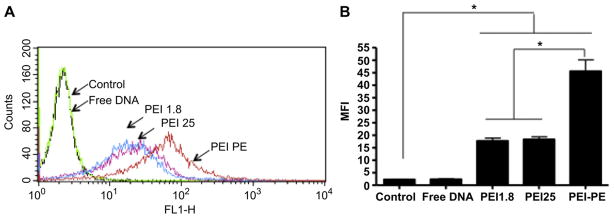

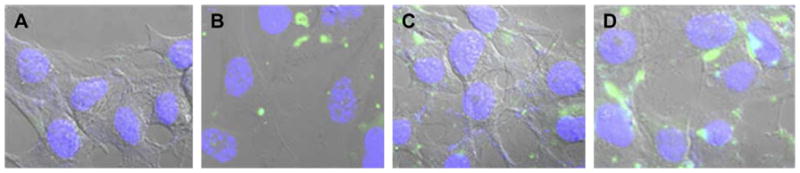

YOYO-1-labeled DNA (DNA-Y) was used to study and compare cellular uptake of complexes. The cellular uptake of complexes with PEI-1.8 and PEI-25 was similar at 4 h (Fig. 5). There was a significant increase in the cellular uptake of DNA-Y complexed with PEI-PE. This was confirmed by the confocal microscopy. Cells treated with PEI-PE complexes showed increased intracellular fluorescence compared to both PEI-1.8- and PEI-25-based complexes (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Cellular uptake of DNA-Y from different complexes (PEI1.8 N/P 16, PEI 25 N/P 4, PEI-PE N/P 16) by B16F10 cells after 4h. A) Histogram analysis, and B) Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of B16F10 cells after incubation with different formulations. *p < 0.05.

Fig. 6.

Confocal microscopy images of cellular interaction of different complexes with B16F10 cell after 4 h incubation. A) Free DNA-Y, and DNA-Y complexes with B) PEI-1.8 (N/P 16); C) PEI-25 (N/P 4); and D) PEI-PE (N/P 16).

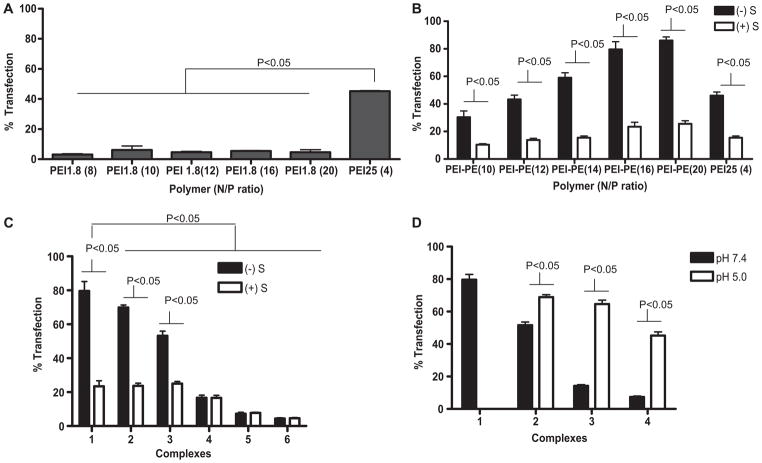

3.6. Transfection efficacy

To check the transfection efficiency of PEI-1.8, B16F10 cells were treated with PEI-1.8/DNA complexes at various N/P ratios. There was no significant increase in GFP-positive cells with the increase in the N/P ratio of PEI-1.8/DNA complexes. Less than 10% GFP-positive cells were observed at the N/P ratio of 20. At the same time, PEI-25 showed almost 45% GFP-positive cells at the N/P ratio 4 (Fig. 7A). Cells treated with complexes with higher N/P ratios showed significant cell death (data not shown). Hence, PEI-25/DNA complexes at the N/P ratio of 4 were chosen as a positive control for further studies.

Fig. 7.

In vitro transfection with: A) PEI-1.8 and PEI-25 complexes; B) PEI-PE and PEI-25 complexes with (+S) and without serum (−S); C) complexes with varying amounts of PEG2000-PE, with (+S) and without serum (−S), 1: PEI-PE N/P 16, and PEI-PE N/P 16 with 2: PEG 0.25, 3: PEG 0.5, 4: PEG 1, 5: PEG 2, and 6: PEG 5; D) complexes with varying amounts of PEG2000-Hz-PE at pH 7.4 or 5.0. 1: PEI-PE N/P 16, and PEI-PE N/P 16 with 2: PEG-Hz 0.5, 3: PEG-Hz 1, 4: PEG-Hz 2.

The transfection efficiency of PEI-PE/DNA complexes at various N/P ratios was also investigated. A significant increase in the percent of GFP-positive cells was observed with increasing N/P ratios when transfections were performed in the serum-free media (−S). In complete media (+S), a significant decrease occurred in percent of GFP-positive cells at all N/P ratios studied. PEI-25 had about 45% and 15% GFP-positive cells in serum-free (−S) and complete media (+S), respectively (Fig. 7B).

To increase the stability of the complexes in serum, complexes were mixed with PEG2000-PE (micelle-forming material). PEI-PE/DNA complexes (N/P 16) were mixed with various amounts of PEG2000-PE (Table 2), and the effect of PEG2000-PE coating on the transfection efficiency was studied in both, serum-free and complete media. As seen in the Fig. 7C, a significant decrease (p < 0.05) in percent of GFP-positive cells was observed with an increase in the amount of PEG2000-PE when transfection was carried out in the serum-free medium.

For formulations containing PEG2000-PE (PEG 0.25 and PEG 0.5, Table 2), there was a significant decrease in the transfection efficiency in complete medium compared to the serum-free medium. The transfection efficiency of formulations with PEG 1-5 (Table 2) did not change significantly in complete media, which clearly shows the protective effect and serum compatibility of PEG2000-PE.

Next, the PEI-PE/DNA complexes were mixed with various amounts of PEG2000Hz-PE (Table 2). A significant decrease (p < 0.05) in the transfection efficiency occurred when complexes were mixed with PEG2000-Hz-PE (pre-incubated at pH 7.4) compared to PEI-PE/DNA complexes indicating PEI shielding. This shielding also might prevent PEI interaction with cells and transfection. However, there was a significant increase in percent of GFP-positive cells when complexes were mixed with PEG2000-Hz-PE pre-incubated at pH 5.0 compared to pH 7.4 (Fig. 7D) indicating that the de-shielding of PEI took place due to the loss of PEG. These data, together with the zeta potential data, clearly establish that the pH-sensitive polymer responds to this difference in pH and may thus be suitable for targeting in the relatively acidified tumor environment.

There was no significant change in percent of GFP-positive cells when complexes were mixed with various amounts of PEG2000-PE (PEG 0.5–2) pre-incubated at pH 7.4 and 5.0 in the serum-free media (data not shown). In all the studies, cells without any additions (controls) and with a free plasmid DNA addition showed negligible transfection (data not shown).

4. Discussion

The objectives of the present work were: (1) to increase the DNA transfection efficiency of low molecular weight PEI (PEI 1.8 kDa) by modification with hydrophobic lipid - DOPE; (2) to ensure relatively low in vitro toxicity of the newly synthesized PEI-PE conjugate; (3) to increase the stability of the PEI-PE/DNA complexes against nucleases and salt-induced aggregation; and (4) to encapsulate these complexes into pH-sensitive PEG-PE micelles to provide tunable transfection and increased stability in complete medium. Our results demonstrate that all these objectives were achieved.

Since the discovery of gene transfection efficiency with PEI [1], PEIs of different molecular weight have been widely studied. Various modifications of the PEIs have been reported to enhance the transfection efficiency and/or to reduce toxicity [14–25]. We have previously studied the PEI-PE conjugate for the delivery of siRNA. It demonstrated enhanced transfection capability and low in vitro toxicity compared to unmodified PEI-1.8 [39]. Hence, we decided to study this polymer for delivery of the plasmid DNA. The PEI-PE conjugate was synthesized by reacting a phospholipid with low molecular weight PEI (PEI-1.8). It was assumed that a PEI-PE conjugate would condense DNA due to the electrostatic interaction between polycationic PEI moieties, while the lipid moieties would help to increase cell interaction of the complexes and facilitate their incorporation into lipid-based micellar systems via hydrophobic interactions. The PEI-PE polymer formed micelles in water with a CMC of 34 μg/ml. The conjugation with DOPE did not diminish DNA condensation capacity of the PEI. Mixing of PEI-PE with plasmid DNA resulted in spontaneous formation of small complexes (<250 nm).

We have checked whether the transfection efficiency of PEI-1.8 is enhanced by conjugation with PE. PEI-25/DNA polyplexes used as positive control showed about 45% transfection at the optimal N/P ratio. PEI-1.8 has a low molecular weight and a small number of superficial primary amines, which decreases its toxicity but also its transfection efficacy. The PEI-1.8 produced less than 10% transfection at all N/P ratios studied, which is in agreement with literature [15]. Compared to PEI-1.8, there was a significant increase in the transfection efficiency of PEI-PE/DNA complexes, and it increased with the increase in the N/P ratio. Low transfection efficiency for a lower N/P ratio of 10 could be attributed to incomplete DNA condensation (these complexes also exhibited a large size of around 508 nm). At the N/P ratio of 12, PEI-PE polymer condensed DNA effectively producing small complexes and showed about 45% transfection efficacy (comparable to PEI 25), which increased to about 80% at the N/P ratio of 16. This could be due to the increased zeta potential with the increase in N/P ratios. Hence, we decided to use the N/P ratio of 16 for all further studies. When compared to PEI-25, the PEI-PE polymer (N/P 16) based on PEI-1.8 showed the 1.7-fold increase in transfection efficiency. Most of the other studies have also shown that the modification of low MW PEIs results in transfection efficiencies slightly higher than, or comparable to that of, PEI-25 [17,42,43].

The cell interaction studies using the labeled DNA (DNA-Y) confirmed the increased interaction of PEI-PE/DNA complexes compared to both PEI-25 or unmodified PEI-1.8. We have selected the YOYO-1 dye, which is a high affinity DNA-binding dye, to study the cell interaction of these complexes [44,45]. The dye itself emits a negligible fluorescence. However, when bound to DNA, its fluorescence is enhanced. Although PEI-1.8 and PEI-25 showed a similar cell association, the lower transfection efficiency of PEI-1.8 compared to PEI-25 could be attributed to the inability of the endosomal escape for PEI-1.8 [46]. Although the exact mechanism underlying an increased cell interaction of PEI-PE complexes is currently unclear, it may perhaps be based on the hydrophobic modifications of the hydrophilic PEI, which change its way of interaction with cell membranes or intracellular trafficking. Further studies are in progress to understand the intracellular trafficking of the PEI-PE complexes. It is also important that the PEI-PE/DNA complexes increased the resistance of the complexed DNA towards the action of DNAase compared to PEI-1.8/DNA complexes, suggesting a protective effect of lipid moieties against the nuclease degradation.

The strong electrostatic interaction between polycationic PEI and polyanionic DNA results in the formation of polyplexes, which do not aggregate because electrostatic repulsion between the particles after those are formed. In the presence of increasing salt concentrations, these particles have a strong tendency to aggregate due to charge shielding with salt ions [47]. The PEI-PE/DNA complexes, however, were resistant to the salt-induced aggregation when compared with PEI-1.8 complexes. A slight increase in size from 225 nm to 304 nm was observed after 24 h incubation in presence of 150 mM NaCl. By contrast, complexes made from PEI-1.8 showed size increase to larger than 1000 nm under similar conditions indicating the aggregation and instability of the complexes in presence of the salt. Thus, the presence of lipid moieties in PEI-PE/DNA complexes provided a barrier effect at high-salt concentrations.

To further increase the stability of the PEI-PE/DNA complexes, they were mixed with various amounts of PEG2000-PE. We assumed that PEG2000-PE would spontaneously incorporate into polyplexes due to the hydrophobic interactions and additionally provide some steric stabilization of polyplexes by forming a protective barrier, shielding the positive charge and enforcing an increased stability in high-salt conditions. The amount of PEG2000-PE was chosen based on the zeta potential studies. It was found that as the amount of PEG2000-PE increased, zeta potential reduced gradually. Thus, the PEG 2 formulation was selected for further studies since it had about neutral zeta potential (Table 2 and Fig. 3). The complexes with PEG 2 were stable in 150 mM NaCl for 24 h with no significant change in size (Table 1). It can be assumed that hydrophobic interactions between the lipid moieties in PEI-PE and those in PEG-PE result in their self-assembly into the micelle-like particles. A similar hydrophobic interaction was suggested between the amphiphilic Pluronic P123 chains of Pluronic P123-grafted PEI, which form a micelle-like structures around the polyplex core and unmodified Pluronic P123 [45,48].

A serious problem with gene delivery using the PEI polymer is the high cytotoxicity of the polymer: the more the PEI content in the complex, the higher the cytotoxicity. On the other hand, high PEI content increases the transfection to a certain extent, so typically a compromise is made between toxicity and transfection efficiency. Importantly, the modification of PEI-1.8 with PE did not change the low toxicity profile of the PEI-1.8.

One of the major drawbacks of non-viral vectors is the inhibition of transfection in presence of serum [49,50] since the serum is rich in anionic proteins that interact with polycations [32]. Such interactions are stronger for highly charged polycations and result in the adsorption of the negatively charged proteins on polyplexes resulting in diminished endocytosis [32]. Therefore, we have studied the effect of the complete medium (+S) on the transfection activities of the PEI-PE/DNA polyplexes compared to PEI-25/DNA polyplexes. PEI-25/DNA polyplexes showed the 45% transfection efficacy in the serum-free medium, which decreased drastically in presence of the serum (Fig. 7B). This was expected since highly positively charged PEI-25/DNA polyplexes interact with negatively charged serum proteins to trigger the dissociation of the complexes and/or diminished endocytosis resulting in the reduction in transfection efficacy. As mentioned earlier, PEI-PE/DNA complexes showed an enhanced transfection compared to PEI-25, but in presence of the serum the transfection efficacy also dropped to only 25% (Fig. 7B).

To increase the serum compatibility the coating of PEI-PE/DNA complexes with PEG-PE was applied, and the effect of various amounts of PEG-PE on the transfection efficacy with (+S) and without serum (−S) were studied. A significant decrease in transfection efficacy occurred with complexes containing PEG 0.25–0.5 (Fig. 7C). Formulations with PEG 1-5 showed no significant change in transfection efficacy in the presence of serum. However, the transfection efficacy was not very high - less than 20%. It is in an agreement with the reported data that the PEGylation of polyplexes can strongly reduce transfection efficiency [26,27,32].

An interesting aspect of tumor physiology is the lowered interstitial pH in tumors compared to the normal body pH. This acidified pH profile arises due to their high metabolic rate which leads to production of excess lactic acid and hydrolysis of ATP under hypoxic conditions [51]. Hence, the pH-sensitive PEG2000-Hz-PE was tested as a coat for PEI-PE/DNA complexes. We have selected pH-sensitive hydrazone linkages based on previous work that proved their pH-dependent degradation kinetics [36]. Here, we have also confirmed that the sterically-protective PEG layer was low-pH cleavable as proved by size exclusion chromatography (Fig. 1) and by the increase in zeta potential of complexes when complexes were mixed with PEG2000-Hz-PE pre-incubated at pH 5.0 for 3 h. In vivo, the PEG2000-Hz-PE is expected to shield the PEI-PE/DNA complex in the systemic circulation and expose the complex only at the tumor sites where the pH is slightly acidic and can facilitate the removal of the PEG coat.

With this in mind, the complexes were mixed with different amounts of PEG2000-Hz-PE pre-incubated at pH 7.4 or pH 5.0 for 3 h. The decrease in the transfection efficacy with the increase in the amount of PEG2000-Hz-PE (formulations with PEG-Hz 0.5–2) at pH 7.4 could be attributed to PEG presence (Fig. 7D). However, the transfection efficacy increased when PEG2000-Hz-PE pre-incubated at pH 5.0 was added. The loss of protective PEG layer increased the interaction with cells. Thus, the encapsulation of PEI-PE/DNA complexes into pH-sensitive micelle-like PEG-Hz-PE coat increased the stability of DNA in complete medium and provided a tunable transfection efficiency by being responsive to changes in pH.

5. Conclusions

We report here the synthesis and characterization of a PEI-DOPE conjugate, which was explored for gene delivery in vitro. The modification with DOPE strongly increased the transfection efficiency of low molecular weight PEI-1.8 kDa without any negative effects on its low cytotoxicity. Mixing of the PEI-PE/DNA complexes with PEG-PE produced particles with near-neutral surface charge, resistance to salt-induced aggregation, and transfection activity unaffected by the presence of serum. We further demonstrated that the use of a lowered pH-degradable PEG-Hz-PE produced particles with transfection activity sensitive to changes in pH, which has a promise for site-specific transfection of tumor cells in vivo.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the NIH grant RO1CA121838 and 1U54CA151881 to V.P. Torchilin.

References

- 1.Boussif O, Lezoualc’h F, Zanta MA, Mergny MD, Scherman D, Demeneix B, et al. A versatile vector for gene and oligonucleotide transfer into cells in culture and in vivo: polyethylenimine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7297–301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akinc A, Thomas M, Klibanov AM, Langer R. Exploring polyethylenimine-mediated DNA transfection and the proton sponge hypothesis. J Gene Med. 2005;7:657–63. doi: 10.1002/jgm.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sonawane ND, Szoka FC, Jr, Verkman AS. Chloride accumulation and swelling in endosomes enhances DNA transfer by polyamine-DNA polyplexes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:44826–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308643200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunner S, Furtbauer E, Sauer T, Kursa M, Wagner E. Overcoming the nuclear barrier: cell cycle independent nonviral gene transfer with linear poly-ethylenimine or electroporation. Mol Ther. 2002;5:80–6. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2001.0509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kircheis R, Wightman L, Wagner E. Design and gene delivery activity of modified polyethylenimines. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;53:341–58. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00202-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gebhart CL, Kabanov AV. Evaluation of polyplexes as gene transfer agents. J Control Release. 2001;73:401–16. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00357-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lungwitz U, Breunig M, Blunk T, Gopferich A. Polyethylenimine-based non-viral gene delivery systems. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2005;60:247–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neu M, Fischer D, Kissel T. Recent advances in rational gene transfer vector design based on poly(ethyleneimine) and its derivatives. J Gene Med. 2005;7:992–1009. doi: 10.1002/jgm.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogris M, Wagner E. Tumor-targeted gene transfer with DNA polyplexes. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 2002;27:85–95. doi: 10.1023/a:1022988008131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lemkine GF, Demeneix BA. Polyethylenimines for in vivo gene delivery. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2001;3:178–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benns JM, Maheshwari A, Furgeson DY, Mahato RI, Kim SW. Folate-PEG-folate-graft-polyethylenimine-based gene delivery. J Drug Target. 2001;9:123–39. doi: 10.3109/10611860108997923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moghimi SM, Symonds P, Murray JC, Hunter AC, Debska G, Szewczyk A. A two-stage poly(ethylenimine)-mediated cytotoxicity: implications for gene transfer/therapy. Mol Ther. 2005;11:990–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bieber T, Meissner W, Kostin S, Niemann A, Elsasser HP. Intracellular route and transcriptional competence of polyethylenimine-DNA complexes. J Control Release. 2002;82:441–54. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00129-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bajaj A, Kondaiah P, Bhattacharya S. Synthesis and gene transfection efficacies of PEI-cholesterol-based lipopolymers. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:1640–51. doi: 10.1021/bc700381v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang DA, Narang AS, Kotb M, Gaber AO, Miller DD, Kim SW, et al. Novel branched poly(ethylenimine)-cholesterol water-soluble lipopolymers for gene delivery. Biomacromolecules. 2002;3:1197–207. doi: 10.1021/bm025563c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim S, Choi JS, Jang HS, Suh H, Park J. Hydrophobic modification of poly-ethyleneimine for gene transfectants. Bull Korean Chem Soc. 2001;22:1069–75. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han S, Mahato RI, Kim SW. Water-soluble lipopolymer for gene delivery. Bioconjug Chem. 2001;12:337–45. doi: 10.1021/bc000120w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gusachenko Simonova O, Kravchuk Y, Konevets D, Silnikov V, Vlassov VV, Zenkova MA. Transfection efficiency of 25-kDa PEI-cholesterol conjugates with different levels of modification. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2009;20:1091–110. doi: 10.1163/156856209X444448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas M, Klibanov AM. Enhancing polyethylenimine’s delivery of plasmid DNA into mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14640–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192581499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brownlie A, Uchegbu IF, Schatzlein AG. PEI-based vesicle-polymer hybrid gene delivery system with improved biocompatibility. Int J Pharm. 2004;274:41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2003.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Incani V, Tunis E, Clements BA, Olson C, Kucharski C, Lavasanifar A, et al. Palmitic acid substitution on cationic polymers for effective delivery of plasmid DNA to bone marrow stromal cells. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;81:493–504. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alshamsan A, Haddadi A, Incani V, Samuel J, Lavasanifar A, Uludag H. Formulation and delivery of siRNA by oleic acid and stearic acid modified polyethylenimine. Mol Pharm. 2009;6:121–33. doi: 10.1021/mp8000815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuo WT, Huang HY, Huang YY. Polymeric micelles comprising stearic acid-grafted polyethyleneimine as nonviral gene carriers. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2010;10:5540–7. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2010.2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ko YT, Kale A, Hartner WC, Papahadjopoulos-Sternberg B, Torchilin VP. Self-assembling micelle-like nanoparticles based on phospholipid-polyethyleneimine conjugates for systemic gene delivery. J Control Release. 2009;133:132–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.09.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Navarro G, Sawant R, Essex S, Tros de ILarduya C, Torchilin V. Phospholipid-polyethylenimine conjugate-based micelle-like nanoparticles for siRNA delivery. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2010;1:25–33. doi: 10.1007/s13346-010-0004-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erbacher P, Bettinger T, Belguise-Valladier P, Zou S, Coll JL, Behr JP, et al. Transfection and physical properties of various saccharide, poly(ethylene glycol), and antibody-derivatized polyethylenimines (PEI) J Gene Med. 1999;1:210–22. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-2254(199905/06)1:3<210::AID-JGM30>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oupicky D, Ogris M, Howard KA, Dash PR, Ulbrich K, Seymour LW. Importance of lateral and steric stabilization of polyelectrolyte gene delivery vectors for extended systemic circulation. Mol Ther. 2002;5:463–72. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trubetskoy VS, Wong SC, Subbotin V, Budker VG, Loomis A, Hagstrom JE, et al. Recharging cationic DNA complexes with highly charged polyanions for in vitro and in vivo gene delivery. Gene Ther. 2003;10:261–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tseng WC, Jong CM. Improved stability of polycationic vector by dextran-grafted branched polyethylenimine. Biomacromolecules. 2003;4:1277–84. doi: 10.1021/bm034083y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahn CH, Chae SY, Bae YH, Kim SW. Biodegradable poly(ethylenimine) for plasmid DNA delivery. J Control Release. 2002;80:273–82. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00547-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mannisto M, Vanderkerken S, Toncheva V, Elomaa M, Ruponen M, Schacht E, et al. Structure-activity relationships of poly(L-lysines): effects of pegylation and molecular shape on physicochemical and biological properties in gene delivery. J Control Release. 2002;83:169–82. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00178-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ogris M, Brunner S, Schuller S, Kircheis R, Wagner E. PEGylated DNA/transferrin-PEI complexes: reduced interaction with blood components, extended circulation in blood and potential for systemic gene delivery. Gene Ther. 1999;6:595–605. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li W, Huang Z, MacKay JA, Grube S, Szoka FC., Jr Low-pH-sensitive poly(−ethylene glycol) (PEG)-stabilized plasmid nanolipoparticles: effects of PEG chain length, lipid composition and assembly conditions on gene delivery. J Gene Med. 2005;7:67–79. doi: 10.1002/jgm.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oishi M, Nagasaki Y, Itaka K, Nishiyama N, Kataoka K. Lactosylated poly(-ethylene glycol)-siRNA conjugate through acid-labile beta-thiopropionate linkage to construct pH-sensitive polyion complex micelles achieving enhanced gene silencing in hepatoma cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1624–5. doi: 10.1021/ja044941d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walker GF, Fella C, Pelisek J, Fahrmeir J, Boeckle S, Ogris M, et al. Toward synthetic viruses: endosomal pH-triggered deshielding of targeted polyplexes greatly enhances gene transfer in vitro and in vivo. Mol Ther. 2005;11:418–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kale AA, Torchilin VP. “Smart” drug carriers: PEGylated TATp-modified pH-sensitive liposomes. J Liposome Res. 2007;17:197–203. doi: 10.1080/08982100701525035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sethuraman VA, Na K, Bae YH. pH-responsive sulfonamide/PEI system for tumor specific gene delivery: an in vitro study. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:64–70. doi: 10.1021/bm0503571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meyer M, Wagner E. pH-responsive shielding of non-viral gene vectors. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2006;3:563–71. doi: 10.1517/17425247.3.5.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Navarro G, Sawant RR, Biswas S, Essex S, Tros de ILarduya C, Torchilin VP. P-Glycoprotein silencing with siRNA delivered by DOPE-modified PEI overcomes doxorubicin resistance in breast cancer cells. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2012;7:65–78. doi: 10.2217/nnm.11.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kale AA, Torchilin VP. Design, synthesis, and characterization of pH-sensitive PEG-PE conjugates for stimuli-sensitive pharmaceutical nanocarriers: the effect of substitutes at the hydrazone linkage on the ph stability of PEG-PE conjugates. Bioconjug Chem. 2007;18:363–70. doi: 10.1021/bc060228x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.La SB, Okano T, Kataoka K. Preparation and characterization of the micelle-forming polymeric drug indomethacin-incorporated poly(ethylene oxide)-poly(beta-benzyl L-aspartate) block copolymer micelles. J Pharm Sci. 1996;85:85–90. doi: 10.1021/js950204r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Incani V, Lavasanifar A, Uludag H. Lipid and hydrophobic modification of cationic carriers on route to superior gene vectors. Soft Matter. 2010;6:2124–38. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neamnark A, Suwantong O, Bahadur RK, Hsu CY, Supaphol P, Uludag H. Aliphatic lipid substitution on 2 kDa polyethylenimine improves plasmid delivery and transgene expression. Mol Pharm. 2009;6:1798–815. doi: 10.1021/mp900074d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wong M, Kong S, Dragowska WH, Bally MB. Oxazole yellow homodimer YOYO-1-labeled DNA: a fluorescent complex that can be used to assess structural changes in DNA following formation and cellular delivery of cationic lipid DNA complexes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1527:61–72. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(01)00149-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gebhart CL, Sriadibhatla S, Vinogradov S, Lemieux P, Alakhov V, Kabanov AV. Design and formulation of polyplexes based on pluronic-polyethyleneimine conjugates for gene transfer. Bioconjug Chem. 2002;13:937–44. doi: 10.1021/bc025504w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou J, Yockman JW, Kim SW, Kern SE. Intracellular kinetics of non-viral gene delivery using polyethylenimine carriers. Pharm Res. 2007;24:1079–87. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9229-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reschel T, Konak C, Oupicky D, Seymour LW, Ulbrich K. Physical properties and in vitro transfection efficiency of gene delivery vectors based on complexes of DNA with synthetic polycations. J Control Release. 2002;81:201–17. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kabanov AV, Batrakova EV, Alakhov VY. Pluronic block copolymers as novel polymer therapeutics for drug and gene delivery. J Control Release. 2002;82:189–212. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matsui K, Sando S, Sera T, Aoyama Y, Sasaki Y, Komatsu T, et al. Cerasome as an infusible, cell-friendly, and serum-compatible transfection agent in a viral size. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:3114–5. doi: 10.1021/ja058016i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang C, Tang N, Liu X, Liang W, Xu W, Torchilin VP. siRNA-containing liposomes modified with polyarginine effectively silence the targeted gene. J Control Release. 2006;112:229–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stubbs M, McSheehy PM, Griffiths JR, Bashford CL. Causes and consequences of tumour acidity and implications for treatment. Mol Med Today. 2000;6:15–9. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(99)01615-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]