Abstract

Background

This study evaluated, using in vitro assays, the antibacterial, antioxidant, and tyrosinase-inhibition activities of methanolic extracts from peels of seven commercially grown pomegranate cultivars.

Methods

Antibacterial activity was tested on Gram-positive (Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus) and Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumonia) using a microdilution method. Several potential antioxidant activities, including radical-scavenging ability (RSA), ferrous ion chelating (FIC) and ferric ion reducing antioxidant power (FRAP), were evaluated. Tyrosinase enzyme inhibition was investigated against monophenolase (tyrosine) and diphenolase (DOPA), with arbutin and kojic acid as positive controls. Furthermore, phenolic contents including total flavonoid content (TFC), gallotannin content (GTC) and total anthocyanin content (TAC) were determined using colourimetric methods. HPLC-ESI/MSn analysis of phenolic composition of methanolic extracts was also performed.

Results

Methanolic peel extracts showed strong broad-spectrum activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, with the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) ranging from 0.2 to 0.78 mg/ml. At the highest concentration tested (1000 μg/ml), radical scavenging activities were significantly higher in Arakta (83.54%), Ganesh (83.56%), and Ruby (83.34%) cultivars (P< 0.05). Dose dependent FIC and FRAP activities were exhibited by all the peel extracts. All extracts also exhibited high inhibition (>50%) against monophenolase and diphenolase activities at the highest screening concentration. The most active peel extract was the Bhagwa cultivar against monophenolase and the Arakta cultivar against diphenolase with IC50 values of 3.66 μg/ml and 15.88 μg/ml, respectively. High amounts of phenolic compounds were found in peel extracts with the highest and lowest total phenolic contents of 295.5 (Ganesh) and 179.3 mg/g dry extract (Molla de Elche), respectively. Catechin, epicatechin, ellagic acid and gallic acid were found in all cultivars, of which ellagic acid was the most abundant comprising of more than 50% of total phenolic compounds detected in each cultivar.

Conclusions

The present study showed that the tested pomegranate peels exhibited strong antibacterial, antioxidant and tyrosinase-inhibition activities. These results suggest that pomegranate fruit peel could be exploited as a potential source of natural antimicrobial and antioxidant agents as well as tyrosinase inhibitors.

Keywords: Antibacterial activity, Tyrosinase-inhibition, Phenolics, Pomegranate, South Africa

Background

Numerous epidemiological studies suggest that diets rich in phytochemicals and antioxidants have protective roles in health and disease [1]. These natural antioxidants might play an important role in combating oxidative stress associated with degenerative diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease and aging [2,3]. The antioxidative phytochemicals, especially phenolic compounds, found in vegetables and fruits have received increasing attention for their potential role in the prevention of human diseases [4-8].

Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.; Punicaceae) has gained popularity in recent years due to its multi-functionality and nutritional benefit in the human diet. The fruit is rich in tannins and other biochemicals, particularly phenolics, which have been reported to reduce disease risk [9,10]. Pomegranate fruit peel constitutes about 50% of the total fruit weight [11], and it is often discarded as waste. However, the fruit peel contains higher amounts of polyphenol compounds than the juice, and it possesses stronger biological activities [12-14]. Studies have shown that pomegranate peel extract had markedly higher antioxidant capacity than juice extract in scavenging against superoxide anion, hydroxyl and peroxyl radicals and it inhibited CuSO4-induced LDL oxidation [12]. Besides high antioxidant capacity, pomegranate peel extracts have been reported to possess a wide range of biological actions including anti-cancer activity [15-17], antimicrobial activity [18,19], anti-diarrheal activity [20], apoptotic and anti-genotoxic properties [21,22], anti-tyrosinase activity [23], anti-inflammatory and anti-diabetic activities [24,25]. Polyphenol compounds such as ellagic tannins, flavonols, anthocyanins, catechin, procyanidins, ellagic acid and gallic acid have been implicated in various pharmacological activities in the fruit peel [24-26]. However, the levels of these compounds in the pomegranate peel may vary among pomegranate cultivars which may result in differing levels of bioactivity [27].

In South Africa, more than ten pomegranate cultivars are being commercially cultivated [28]. Till date, there is no available information on bioactivities of fruit peels of pomegranate cultivars grown under South African agro-climatic conditions. If fruit peels of pomegranate cultivars show potential to improve human health, their utilisation should be encouraged during fruit processing. In the quest to promote the development of functional foods with health-benefiting properties, we investigated the antibacterial, antioxidant, and tyrosinase-inhibition activities of extracts from peels, using in vitro assays, of seven commercially pomegranate cultivars grown in the Western Cape, South Africa. Furthermore, the total phenolic content including flavonoid, gallotannin and anthocyanin content, and individual phenolics were quantified.

Methods

Plant material

The studies were performed on peels of seven pomegranate fruit cultivars (Arakta, Bhagwa, Ganesh, Herskawitz, Molla de Elche, Ruby, and Wonderful) which are commercially grown in South Africa. Fruit were procured from a commercial pomegranate pack house in Porterville (Western Cape Province). Fruit were harvested between February and May 2010, packed in paperboard cartons and transported in air-conditioned car to the Postharvest Research Laboratory. Immediately on arrival in the laboratory, ten fruits per cultivar were washed and manually peeled. The peels were freeze-dried, ground into powder form, and stored in airtight containers at 7°C in the dark.

Preparation of peel extract

For each cultivar, each finely-powdered peel sample (2 g) was extracted separately with 10 ml of 80% (v/v) methanol (MeOH) and distilled water (aqueous) by sonication for 1 h [29]. The extract was filtered under vacuum through Whatman No.1 filter paper, and the residue was re-extracted further following the same procedure. Extracts were air-dried under a stream of air and first tested in the antibacterial assay to determine which extracts would be worth subjecting to further pharmacological investigations. Only the methanol extract was tested further in other assays, as it recorded highest antibacterial activity.

Antibacterial property

Microdilution antibacterial assay

The antibacterial activity of peel extract was tested using the microdilution antibacterial assay for the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values [30] as detailed by Fawole et al. [31], except that in the present study the initial concentration (50 mg/ml) of the sample was prepared by dissolving dried extracts in 80% (v/v) methanol. Two Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli ATCC 11775 and Klebsiella pneumonia ATCC 13883) and two Gram-positive bacteria (Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6051 and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 12600) were used. The extract was serially diluted two-folds with sterile distilled water in a 96-well micro-plate in triplicate for each of the four bacteria used. Streptomycin (0.1 mg/ml) was used as positive control, while water and bacteria-free broth were included as negative controls under the same conditions. Methanol (80%) was also included to check for false antibacterial activity. The final concentration of pomegranate extract ranged from 0.097 – 12.5 mg/ml, reducing the methanol content in the test extract to between 0.19 and 20%, whereas streptomycin was between 0.78 and 100 μg/ml.

Antioxidant property

Radical-scavenging ability

The scavenging ability of stable free radicals such as 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) is a known mechanism for antioxidation. The DPPH assay was carried out in triplicate, according to the method reported by Karioti et al. [32]. Extracts of different concentrations (10, 100 and 1000 μg/ml) were tested in triplicate for free-radical scavenging activity. The scavenging activity of the extract was compared with ascorbic acid (1000 μg/ml). A blank containing methanol instead of the test sample or ascorbic acid was also included under the same condition. The free radical scavenging activity (RSA) as determined by the decolouration of the DPPH solution was calculated according to the formula:

| (1) |

where Atest is the absorbance of the reaction mixture containing the standard antioxidant or extract, and Ablank is the absorbance of the blank test.

Ferrous ion chelating (FIC) assay

The FIC activity assay of Singh and Rajini [33] was adopted. Briefly, 0.1 mM FeSO4 (0.5 ml) was mixed with the extract (0.5 ml) of different concentrations (10, 100 and 1000 μg/ml) in triplicate, followed by adding 0.25 mM ferrozine (1 ml). The reaction mixtures were incubated for 10 min and the absorbance (A) was measured at 562 nm. Ascorbic acid (1000 μg/ml) was included as the positive control. A blank test containing methanol instead of the test sample or ascorbic acid was also included under the same condition. The ability of extracts to chelate ferrous ions was calculated using the following equation:

| (2) |

where Atest is the absorbance of the reaction mixture containing extract or ascorbic acid and Ablank is the absorbance of the blank test.

Ferric ion reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay

The reducing power of extracts was measured according to the colourimetric method reported by Benzie and Straino [34] with a few modifications. In triplicates, methanolic extract (150 μl) of different concentrations at 10, 100 or 1000 μg/ml was added to 2850 μl of FRAP solution that constituted of 300 mM acetate buffer, 50 ml; 10 mM 2,4,6-tripyridyl-s-triazine (TPTZ), 5 ml; and 20 mM ferric chloride, 5 ml. Following the same procedure, a blank test containing 80% methanol instead of extract was included, while trolox at 10 μg/ml served as the positive control under the same condition. The reaction mixtures were incubated in the dark for 30 min. The reduction of the Fe3+-TPTZ complex to a coloured Fe2+-TPTZ complex by the extract was monitored by measuring the absorbance at 593 nm using a Helios Omega UV–vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific technologies, Madison, USA). The changes in absorbance values of test reaction mixtures from the initial blank reading were considered as FRAP activity.

Tyrosinase inhibition property

Tyrosinase inhibition activity was determined as described by Momtaz et al. [35], with L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA, Sigma) and tyrosine as substrates. Samples were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to a concentration of 20 mg/ml, and further diluted in potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 6.5) to 600 μg/ml. Assays were carried out in a 96-well micro-titre plate and a Multiskan FC plate reader (Thermo scientific technologies, China) was used. All the steps in the assay were conducted at room temperature. In triplicate, each prepared sample (70 μl) was mixed with 30 μl of tyrosinase (333 Units/ml in phosphate buffer, pH 6.5). After 5 min incubation, 110 μl of substrate (2 mM L -tyrosine or 12 mM L-DOPA) was added to the reaction mixtures and incubated further for 30 min. The final concentration of the extract was between 2.6 – 333.3 μg/ml. Arbutin (1.04 – 133.33 μg/ml) was used as a positive control while a blank test was used as each sample that had all the components except L-tyrosine or L-DOPA. Results were compared with a control consisting of DMSO instead of the test sample. Absorbance values of the wells were then determined at 492 nm. The percentage tyrosinase inhibition was calculated as follows:

| (3) |

where Acontrol is the absorbance of DMSO and Asample is the absorbance of the test reaction mixture containing extract or arbutin. The IC50 values of extracts and arbutin were calculated.

Phenolic content determination

Total phenolic content (TPC)

The total phenolic (TP) content was determined in triplicate by the Folin-Ciocalteu (Folin-C.) colourimetric method [36] as modified by Makkar [37] and calculated as gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per gram DM.

Total flavonoid content (TFC)

Total flavonoid content (TFC) was determined using the method described by Yang et al. [38] and the results were expressed as catechin equivalent (CAE) per gram DM.

Rhodanine assay for gallotannin content (GTC)

Determination of the gallotannin content in peel methanolic extracts was carried out as described by Makkar [37]. Samples (50 μl) were mixed with 150 μl of 0.4 N sulphuric acid followed by 600 μl rhodanine. After 10 min, 200 μl of 0.5 N KOH were added and subsequently distilled water (4 ml) after 2.5 min. The absorbance was read at 520 nm (room temperature) against a blank test that contained aqueous methanol instead of the sample after 15 min incubation. The GTC was calculated from the standard curve (gallic acid) and expressed as gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per gram DM.

Total anthocyanin content (TAC)

Total anthocyanin content (TAC) was quantified using the pH differential method described by Wrolstad [39]. In triplicate, each extract (1 ml) was mixed with 9 ml of pH 1.0 and pH 4.5 buffers, in separate test tubes. Absorbance of the reaction mixture was measured at 520 and 700 nm in pH 1.0 and 4.5 buffers. The total absorbance was calculated from Equation 4, while total anthocyanin content was calculated from Equation 5. The result was expressed as cyanidin 3-glucoside.

| (4) |

| (5) |

A = Absorbance, ε = Cyd-3-glucoside molar absorbance (26,900), MW = anthocyanin molecular weight (449.2), DF = dilution factor, L = cell path-length (1 cm). Final results are expressed as Cyd-3-glucoside equivalent (C3gE) per gram dry matter (μg C3gE/g DM).

HPLC-ESI/MSn analysis of phenolic composition

The LC-MS analysis of phenolics and anthocyanin components in the pomegranate peel extract was performed according to Fischer et al. [40] with slight modification, using a Synapt G2 mass spectrometer UPLCTM system (Waters Corp., Milford, USA) connected to a photo diode array detector and a BEH C18 column (1.7μm particle size, 2.1x100 mm, Waters Corp.). The mobile phases were 5% formic acid in water (v/v) as eluent A and 95% acetonitrile, 5% formic acid (v/v) as eluent B. The flow rate was fixed at 0.2ml/min and the column temperature was set at 40°C. The electrospray ionization (ESI) probe was operated in the positive mode with the capillary voltage of 3 kV; and cone voltage of 15 V. The injection volume was 10 μl and the detection was the diode array detector was set at between 200–600 nm. Individual phenolic compounds were quantified by comparison with a multipoint calibration curve obtained from the corresponding standard (catechin, epicatechin, protocatechuic acid, gallic acid, ellagic acid) from Sigma Aldrich (Germany), while anthocyanins were quantified by an external standard cyanidin 3, 5-diglucoside (Sigma Aldrich, Germany).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean values (±S.E). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using SPSS 10.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc. Chicago, USA). Where there was statistical significance (P < 0.05), the means were further separated using Duncan’s Multiple Range Test. Graphical analysis carried out using GraphPad Prism software version 4.03 (GraphPad Software, Inc. San Diego, USA). The IC50 values for the tyrosinase assay were calculated from the logarithmic non-linear regression curve derived from the plotted data using GraphPad Prism software version 4.03 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, USA).

Results and discussion

Antibacterial activity

Antibacterial activities of methanol and aqueous peel extracts of all the investigated pomegranate cultivars is presented in Table 1. None of the aqueous extracts exhibited good antibacterial activity at the highest screening concentration (> 12.5 mg/ml). The methanol extract, however, showed varying broad-spectrum antibacterial activity at statistically different MIC values (P < 0.05) against the test bacteria. Although it is ideal to test plant extracts against a wide range of target microorganisms, taxonomically representative bacterial species were used in this test to avoid handling numerous pathogenic microorganisms. The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) were obtained for extract concentrations ranging from 0.78 to 0.20 mg/ml. In this study, MIC values less than 1.0 mg/ml were considered active for crude extracts [41]. Similar to the findings reported by Opara et al. [42] on peels of pomegranates grown in Oman, all peel extracts of the investigated fruit cultivars showed activity against the Gram negative and positive bacteria used. These findings are contrary to the work of Kanatt et al. [43], which reported that pomegranate extracts showed little or no effect with regards to Gram negative bacteria. The content of methanol used in the assay was inactive against tested bacteria in the assay. It is worth noting that although 80% methanol was used to dissolve the extracts, methanol concentration was <1.25% in all the extracts where the MIC values were record. The total antibacterial index (TAI) was calculated to determine the overall effects of the peel extracts of each cultivar of pomegranate studied against test bacteria. The most active cultivar was Herskawitz with the highest TAI value (6.25), while the lowest TAI value was exhibited by Bhagwa cultivar; clearly indicating that activity was cultivar dependent.

Table 1.

Antibacterial activity of fruit peel methanol extracts of pomegranate cultivars cultivated in South Africa

| |

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC; mg/ml) |

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultivar | Extract | B.s | E.c | K.p | S.a | TAI |

| Arakta |

MeOH |

0.39b |

0.78b |

0.20a |

0.39b |

6.00b |

| |

Aqueous |

>12.50 |

>12.50 |

>12.50 |

>12.50 |

<1.00 |

| Bhagwa |

MeOH |

0.39b |

0.78b |

0.20a |

0.78c |

5.70a |

| |

Aqueous |

>12.50 |

>12.50 |

>12.50 |

>12.50 |

<1.00 |

| Ganesh |

MeOH |

0.39b |

0.39a |

0.20a |

0.78c |

6.00b |

| |

Aqueous |

>12.50 |

>12.50 |

>12.50 |

>12.50 |

<1.00 |

| Herskawitz |

MeOH |

0.20a |

0.39a |

0.20a |

0.78c |

6.25c |

| |

Aqueous |

>12.50 |

>12.50 |

>12.50 |

>12.50 |

<1.00 |

| Molla de Elche |

MeOH |

0.39b |

0.78b |

0.39b |

0.26a |

5.92ab |

| |

Aqueous |

>12.50 |

>12.50 |

>12.50 |

>12.50 |

<1.00 |

| Ruby |

MeOH |

0.39b |

0.39a |

0.39b |

0.39b |

6.00b |

| |

Aqueous |

>12.50 |

>12.50 |

>12.50 |

>12.50 |

<1.00 |

| Wonderful |

MeOH |

0.39b |

0.59ab |

0.33b |

0.39b |

5.99b |

| |

Aqueous |

>12.50 |

>12.50 |

>12.50 |

>12.50 |

<1.00 |

| Streptomycin (μg/ml) | 3.13 | 3.13 | 2.60 | 5.21 | ||

Mean values in the same column followed by different letters (a-c) represent statistical different (P <0.05) using the Duncan’s multiple range test. MIC- Minimum inhibitory concentration, TAI – Total antibacterial index, the higher the TAI the higher antibacterial activity.

Pomegranate peel polyphenols, especially tannins are the major components in the pomegranate peel extract that have been implicated in antimicrobial potential (for example, antiviral, antifungal and antibacterial activities) [44]. Vasconcelos [45] studied the antibacterial activity of methanolic peel extracts of pomegranate cultivars against both Gram negative and positive bacteria strains and reported MIC values ranging from 0.25 to 4.0 mg/ml against the test bacteria. The author reported a two-fold MIC value against a Gram positive bacterium (S. aureus) than against a Gram negative bacterium (E. coli). It has been suggested that the antimicrobial activity of tannins may be due to the ability of tannin compounds to precipitate proteins, therefore causing leakage of cell membrane of the microorganism [19], and aiding cell lysis which ultimately leads to cell death.

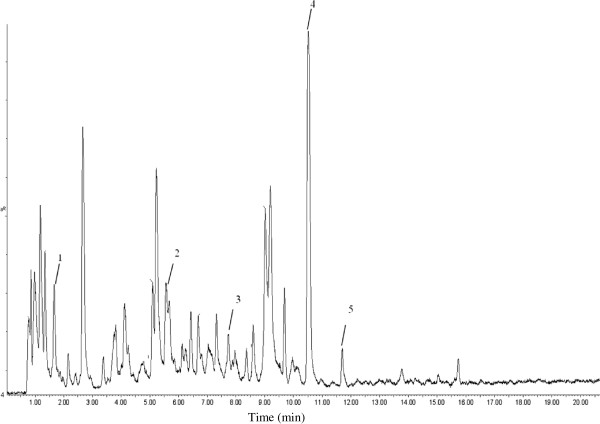

As the peel extracts are complex mixtures of metabolites (Figure 1), it is difficult to pinpoint all the metabolites that are responsible for pharmacological activity. Other researchers have postulated that punicalagin, along with a combination of various phytochemicals, plays a positive role in perceived bacterial inhibition. Considering the broad spectrum antibacterial property exhibited by the methanolic extracts, the fruit peel of the investigated pomegranate cultivars can be considered an effective antibacterial agent. Several reasons may explain varying antibacterial potency of the extracts tested here. Differences in antibacterial activities in the peel extracts may be linked to inter-genetic cultivar variability which is also associated with the inherent chemical composition of the fruit peel. Also, gene-to-biosynthetic modifications are well established in plants as they respond plastically to geo-environmental spatial variation [46]. Secondary metabolites play a key role as defence chemicals for many plants, and so, their accumulation is often dependent on environmental factors. Chemical heterogeneity ultimately leads to differences in the bioactivity of extracts derived from plants growing in different microclimatic areas as these plants face different abiotic and biotic challenges altering gene expression and secondary metabolite synthesis [47].

Figure 1.

Typical HPLC-MS chromatogram of methanolic peel extract of pomegranate fruit. (1) Gallic acid; (2) Catechin; (3) Epicatechin; (4) Ellagic acid; (5) Rutin.

Antioxidant activity

Negi and Jayaprakasha [48] extracted antioxidants from pomegranate peel with the use of methanol, acetone or water and found that methanol gave maximum antioxidant yield. In this study, some degree of radical scavenging activity (RSA) was observed in all the evaluated extracts, with considerable increase in RSA with increase in concentration level. Considering RSA of 50% as good activity, poor RSAs were exhibited by all the evaluated samples at concentrations of 100 μg/ml and 10 μg/ml (Table 2). However at the highest concentration tested (1000 μg/ml), the RSA was superior in all the fruit cultivars. The RSA values were significantly higher in Arakta (83.54%), Ganesh (83.56%), and Ruby (83.34%) cultivars (p < 0.05), while the lowest activity was exhibited by the Molla de Elche cultivar (71.65%). The RSA of ascorbic acid (67.02%), used in this study as a positive control, was lower than the plant extracts at 1000 μg/ml.

Table 2.

Antioxidant activity of fruit peel methanol extracts of seven pomegranate cultivars cultivated in South Africa

| |

DPPH (%) |

FIC (%) |

FRAP (abs. at 593 nm) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultivar | 1000 μg/ml | 100 μg/ml | 10 μg/ml | 1000 μg/ml | 100 μg/ml | 10 μg/ml | 1000 μg/ml | 100 μg/ml | 10 μg/ml |

| Arakta |

83.54±0.31d |

13.35±0.98ab |

5.55±0.06c |

79.44±0.21a |

49.94±0.89a |

37.32±1.82b |

1.19±0.03ns |

0.52±0.02b |

0.11±0.00c |

| Bhagwa |

73.02±0.26ab |

12.34±0.73ab |

1.37±0.34a |

84.96±1.43bc |

65.54±1.09c |

18.83±0.22a |

1.03±0.28 |

0.38±0.00ab |

0.04±0.01a |

| Ganesh |

83.56±0.05d |

16.70±0.83bc |

2.42±0.99ab |

82.98±0.18b |

65.82±0.51c |

15.80±0.52a |

1.47±0.04 |

0.73±0.12c |

0.08±0.01bc |

| Herskawitz |

78.06±0.71c |

15.18±0.97abc |

2.71±0.77ab |

87.82±0.57de |

69.97±0.25d |

34.32±2.45b |

1.29±0.04 |

0.34±0.01ab |

0.08±0.02bc |

| Molla de Elche |

71.65±0.08a |

10.59±0.18a |

1.61±0.08a |

86.59±0.90cd |

70.57±0.43d |

47.24±1.34c |

1.47±0.11 |

0.33±0.05a |

0.03±0.00a |

| Ruby |

83.34±0.51d |

19.67±2.24c |

4.10±2.24bc |

83.58±0.62b |

53.39±1.29b |

47.25±0.66c |

1.18±0.02 |

0.38±0.00ab |

0.08±0.01bc |

| Wonderful |

74.19±1.05b |

12.22±3.13ab |

3.01±0.47ab |

89.67±0.72e |

71.02±0.38d |

49.65±1.26c |

1.32±0.16 |

0.33±0.01a |

0.06±0.00ab |

| Ascorbic acid |

67.02±0.06 |

|

|

62.15±0.98 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Trolox | 0.82±0.03 | ||||||||

Means in the same column followed by different letters (a-e) represent statistical significance (P <0.05) according to the Duncan’s multiple range test. Positive controls: Ascorbic acid and trolox.

The chelating ability of methanolic extracts of pomegranate peel on ferrous ion is presented in Table 2. Similar to the RSA results, the ferrous ion chelating (FIC) activity of methanolic peel extract exhibited a linear exponential relationship with extract concentration. Although low FIC activity was exhibited at the lowest concentration (10 μg/ml) assayed, extracts of Molla de Elche, Ruby and Wonderful showed relatively good FIC activity, ranging from 47.24 to 49.65%. At 100 μg/ml the FIC activity of all extracts (except Arakta cultivar) increased above 50%, with Herskawitz, Molla de Elche and Wonderful, showing highest values of 69.97%, 70.57% and 71.02%, respectively. Moreover, FIC activity exhibited by methanolic extracts of most of the investigated at 100 μg/ml were higher than that of the positive control (ascorbic acid at 1000 μg/ml). Dose dependent FIC activity exhibited by all the investigated extracts indicate that the pomegranate fruit peel contains constituents that inhibit oxidation through a mechanism other than radical scavenging activity.

The FRAP assay measures the ability of an antioxidant to reduce ferric (III) to ferrous (II) in a redox-linked colourimetric reaction that involves single electron transfer [12]. The reducing power of a compound serves as a significant indicator of its potential antioxidant activity. All the investigated extracts showed dose-dependent reducing power (Table 2). Interestingly, there was no significant difference (p < 0.05) in the reducing capacities among all the cultivars at the highest concentration (1000 μg/ml).

Antioxidant capacity based on both the free radical scavenging and the oxidation–reduction mechanisms may be determined by several methods, although the mechanism of action set in motion by antioxidant compounds is still not clearly understood [26]. Previous studies have shown strong antioxidant activity in pomegranate fruit peel extracts [12,13]. In comparison with other fruit peels, Okonogi et al. [49] studied the radical scavenging activity on DPPH and ABTS of pomegranate peel extract with other fruit types including rambutan, mangosteen, banana, coconut, dragon fruit, passion fruit as well as long-gong fruit. In the study the highest scavenging activity was reported in pomegranate peel extract. The observed antioxidant property in the peel extract in this study could be attributed to polyphenol compounds such as ellagic tannins, ellagic acid and gallic acid [24,50]. The results show that pomegranate peel may have great relevance in the prevention and therapies of diseases in which oxidants or free radicals are implicated, hence could serve as an economic source of natural antioxidants.

Tyrosinase inhibition activity

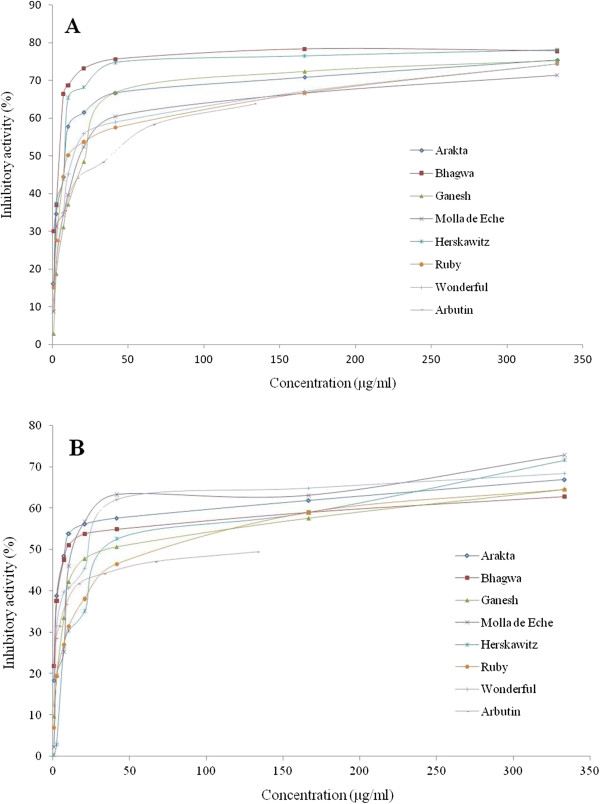

Tyrosinase inhibitors are chemical agents capable of reducing enzymatic reactions such as food browning and melanisation of human skin [23]. Results of tyrosinase inhibition activity of pomegranate methanol peel extract at different concentration (2.6–333.3 μg/ml) are presented in Figure 2 A and B against monophenolase (tyrosine) and diphenolase (DOPA), respectively, and activities were assessed in terms of dopachrome formation. Although the extracts were initially dissolved in 100% DMSO, the final content of the DMSO in the reaction mixture was between 0.14% and 18.3%. Also, DMSO was used as a control in the assay therefore the effect of DMSO (if any) would have been taken care of in the calculation. Generally, tyrosinase inhibition was displayed in a dose-dependent way and there was higher monophenolase inhibition than diphenolase inhibition. In this study, inhibition activity percentage above 50% was described as good tyrosinase inhibition. All extracts exhibited good inhibition against monophenolase and diphenolase activities at the highest screening concentration (Figure 2). Furthermore, there were significant (p < 0.05) differences in the concentrations of 50% tyrosinase inhibition (IC50) by the fruit peel. The most active peel extract was the Bhagwa cultivar against monophenolase and the Arakta cultivar against diphenolase with IC50 values of 3.66 μg/ml and 15.88 μg/ml, respectively (Table 3). The inhibitory activities of most of the peel extracts were higher than the positive control (arbutin) which is a known tyrosinase inhibitor. The IC50 values obtained in this study were higher than those reported by Yoshimura et al. [23] where IC50 value of 182.2 μg/ml was reported for 50% aqueous ethyl alcohol extract of pomegranate rind. Polyphenols are also the largest groups in tyrosinase inhibitors until now [51]. The pomegranate fruit peel is rich in polar substances such as polyphenol such as flavonoid constituents and tannins. In solution, the defining characteristic of tannins is the ability to precipitate mainly proteins, and the structure of flavonoid is compatible with the roles of both substrates and inhibitors of tyrosinase [51]. It could be suggested that tannin content in pomegranate peel could precipitate tyrosinase enzyme, thereby inhibiting enzymatic activity in the reaction medium. These constituents are readily soluble in methanol and show high tyrosinase inhibitory activity in different plants [52,53].

Figure 2.

Tyrosinase enzyme inhibitory activity of fruit peel methanol extracts of seven pomegranate cultivars cultivated in South Africa. Monophenolase inhibition (A) and Diphenolase inhibition (B).

Table 3.

Effective inhibition concentration (EC50) of fruit peel methanol extracts against tyrosinase

| Cultivar | IC50Monophenolase (μg/ml) | IC50Diphenolase (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|

| Arakta |

11.03±0.08c |

15.88±0.10a |

| Bhagwa |

3.66±0.11a |

21.16±0.09a |

| Ganesh |

25.38±0.06f |

40.93±0.12b |

| Herskawitz |

7.56±0.08b |

59.03±0.07c |

| Molla de Elche |

25.56±0.06f |

27.11±0.09ab |

| Ruby |

20.33±0.07d |

114.9±0.08e |

| Wonderful |

23.67±0.06e |

27.26±0.07ab |

| Arbutin | 34.66±0.05g | 98.66±0.12d |

Mean values in the same column followed by different letters (a-f) represent statistical different (P <0.05) using the Duncan’s multiple range test.

According to Yoshimura et al. [23], ellagic acid in pomegranate rind showed an inhibitory effect on tyrosinase in vitro and a whitening effect in vivo on UV-induced pigmentation of brownish guinea pig skin. On the contrary, however, Chang [51] argued that some phenolic compounds could be mistakenly classified as tyrosinase inhibitors due to their role as alternative enzyme substrates whose quinoid reaction products absorb in a spectral range different from that of dopachrome. As a result, when the phenolics show a good affinity for the enzyme, dopachrome formation is prevented.

Phenolic compounds analysis

Total phenolics, flavonoid, gallotannin and anthocyanin

Pomegranate fruit components are rich in phenolic compounds which have synergistic and/or additive effects on its pharmacological properties [22]. Phenolic constituents in pomegranate peel have been implicated in bioactivities such as antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-tyrosinase activities [23,24,44]. Results obtained in this study revealed significant cultivar differences (p < 0.05) in the levels of phenolic compounds (Table 4). The Ganesh cultivar had the highest amount of total phenolics (295.5 mg/g DM) whereas Molla de Elche cultivar had the lowest phenolic contents (179.3 mg/g DM). These results corroborate the levels of total phenolic content (249.4 mg/g) reported by Li et al. [12], who also found that total phenolic content of pomegranate peel extract was 10-fold as high as that of the juice extract. Similarly, the highest (126 mg/g DM) and lowest (97.8mg/g DM) contents of total flavonoid were measured in Ruby and Wonderful cultivars, respectively. This result was expected as flavonoid is a major phenolic group in pomegranate and should contribute to the total phenolic content in the peel extracts. Flavonoid contents found in the investigated cultivars were higher than the value reported by Li et al. [12]. Although the gallotannin content in Arakta (783.6 μg/g DM) was insignificantly higher than that of Ganesh (777.2 μg/g DM) the cultivar contained higher amount of gallotannin than in other cultivars. Anthocyanin is one of the most important groups of flavonoid which is responsible for red colouration of pomegranate fruit [54]. Total anthocyanin was the highest in Wonderful (322.2 μg/g DM) whereas the lowest was contained in the Molla de Elche cultivar (58.5 μg/g DM).

Table 4.

Phenolic contents in fruit peel methanol extracts of seven pomegranate cultivars cultivated in South Africa

|

Cultivar |

Total phenolics |

Total flavonoid |

Total gallotannin |

Total anthocyanin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg GAE/ g DM | mg CAE /g DM | μg GAE/ g DM | μg C3gE /g DM | |

| Arakta |

187.4±6.44ab |

103.0±1.86a |

783.6±65.11d |

289.7±1.63d |

| Bhagwa |

224.1±6.86c |

112.6±1.51b |

697.7±42.92cd |

312.6±1.25e |

| Ganesh |

295.5±23.91d |

121.1±3.12c |

777.2±34.28d |

65.1±1.00a |

| Herskawitz |

198.1±9.22abc |

101.0±1.02a |

530.1±33.86b |

195.9±2.25c |

| Molla de Elche |

179.3±4.60a |

99.5±2.94a |

560.3±62.08bc |

58.5±1.27a |

| Ruby |

218.2±4.53bc |

126.0±0.57c |

326.0±35.28a |

111.7±3.51b |

| Wonderful | 189.1±3.79ab | 97.8±2.10a | 466.3±69.4ab | 322.2±11.90f |

GAE, gallic acid equivalent; CAE, catechin equivalent; C3gE, cyanidin-3glucoside equivalent; DM, dry mass. Mean values in the same column followed by different letters (a-c) represent statistical different (P <0.05) using the Duncan’s multiple range test.

HPLC-MSn analysis of phenolic composition

Individual phenolic compounds in pomegranate fruit peel such as punicalagin, ellagic acid, gallic acid, caffeic acid, protocatechuic acid and p-coumaric acid have received considerable attention due to their potent antibacterial, antioxidant and anti-tyrosinase activities [22,24,44,50,55,56]. High-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS) was used to determine the individual concentrations of the most prominent phenolic compounds in the methanolic peel extract of pomegranate cultivars studied. As shown in Figure 3, seven individual phenolics were identified and quantified, namely; anthocyanins: delphinidin 3,5-diglucoside, cyanidin 3,5-diglucoside flavonoids: catechin, epicatechin and rutin; hydrolysable tannin: ellagic acid; and hydroxybenzoic acid: gallic acid. Phenolic profile and concentration varied amongst the fruit cultivars. Catechin, epicatechin, ellagic acid and gallic acid were found in all cultivars, of which ellagic acid was the most abundant comprising of more than 50% of total phenolic compounds detected in each cultivar. The concentration of ellagic acid ranged from 46.87 μg/ml (Ruby) to 209.44 μg/ml (Ganesh). The anthocyanin types; delphinidin 3,5- diglucoside and cyanidin 3,5- diglucoside, were detected in Arakta, Bhagwa and Herskawitz cultivars, while Ganesh, Ruby and Wonderful cultivars contained only cyanidin 3,5- diglucoside (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Phenolics composition in peel methanol extracts of seven pomegranate cultivars. Ark- Arakta, Bhg- Bhagwa, Gsh- Ganesh, Hesk- Herskawitz, Molla- Molla de Elche, Rby- Ruby & Wond- Wonderful.

Noda et al. [57] reported that cyanidin, pelargonidin, and delphinidin were the principal anthocyanins in pomegranate peel. In the present study, Rutin was found in all cultivars except in Wonderful cultivar, and catechin was the highest in Molla de Elche cultivar with a concentration of 28.85 μg/ml. Overall, the total concentration of the identified phenolic compounds was in the order of Ganesh >Herskawitz >Molla de Elche >Bhagwa >Arakta >Wonderful >Ruby. The presence of these polyphenols in the pomegranate peel may be responsible for the bioactivities observed in the methanol extracts. Phenolic types contained in plants influence antimicrobial activity of the plants [58]. For instance, flavone, quercetin and naringenin were reported showing strong inhibitory activity on the growth of Aspergillus niger, Bacillus subtilis, Candida albicans, Escherichia coli, Micrococcus luteus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis, while gallic acid inhibited only P. Aeruginosa whereas no inhibitory activity was exhibited by rutin and catechin on the tested microorganisms [58]. Major chemicals identified through LCMS may not be the only compounds responsible for bioactivity in the pomegranate peel extracts. Other compounds not identified may play a more significant role in the biological activities exhibited by the peel extracts.

Conclusion

This study has shown that the peel of the investigated pomegranate fruit cultivars possess strong antibacterial, antioxidant and anti-tyrosinase activities. Therefore the peel of the pomegranate fruit cultivars, instead of being wasted, could be exploited as a potential source of natural antimicrobial and antioxidant agents, as well as a potential tyrosinase inhibitor. The findings provide scientific basis to promote value-adding of pomegranate fruit peels for pharmaceutical and cosmetic purposes. Further studies on the isolation of active ingredients, determination of cytotoxicity and genotoxicity effects as well as the mode of action of tyrosinase-inhibitory, antibacterial and antioxidant properties in pomegranate peel extracts are warranted.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

OAF was involved in sample collection, carried out the antibacterial, antioxidant and tyrosinase assays as well as statistical analysis, and also drafted the manuscript. NPM was heavily involved in the antibacterial assay as well as phytochemical and HPLC-MS analyses, and was also mainly involved in scientific correction of the draft manuscript. ULO designed and supervised the study, and revised the manuscript for critically important content. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Olaniyi A Fawole, Email: fawwyb@yahoo.com.

Nokwanda P Makunga, Email: makunga@sun.ac.za.

Umezuruike Linus Opara, Email: opara@sun.ac.za.

Acknowledgments

This work is based upon research supported by the South African Research Chairs Initiative of the Department of Science and Technology and National Research Foundation (Pretoria). The authors are grateful to Citrogold Ltd South Africa and Perishable Products Export Control Board (PPECB) for their financial support. Dr M Stander (Central Analytical Facility, Stellenbosch University) is thanked for her assistance with HPLC-MS analysis. The authors acknowledge the input of the Division of Research Development (Subcommittee B) at Stellenbosch University.

References

- Lampe JW. Health effects of vegetables and fruits: assessing mechanism of action in human experimental studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:475–490. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.3.475s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong SP, Leong LP, Koh JHW. Antioxidant activities of aqueous extracts of selected plants. Food Chem. 2006;99:775–783. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.07.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naczk M, Shahidi F. Phenolics in cereals, fruits and vegetables: Occurrence, extraction and analysis. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2006;41:1523–1542. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Hameed ESS. Total phenolic contents and free radical scavenging activity of certain Egyptian Ficus species leaf samples. Food Chem. 2009;114:1271–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Luo Q, Sun M, Corke H. Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds of 112 Chinese medicinal plants associated with anticancer. Life Sci. 2004;74:2157–2184. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazra B, Sarkar R, Biswas S, Mandal N. Comparative study of the antioxidant and reactive oxygen species scavenging properties in the extracts of the fruits of Terminalia chebula, Terminalia belerica and Emblica officinalis. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2010;10:20. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-10-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazra B, Biswas S, Mandal N. Antioxidant and free radical scavenging activity of Spondias pinnata. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2008;8:63. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-8-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opara UL, Al-Ani MR. Antioxidant contents of pre-packed fresh-cut versus whole fruit and vegetables. Br Food J. 2010;112:797–810. doi: 10.1108/00070701011067424. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martınez JJ, Melgarejo P, Hernandez F, Salazar DM, Martınez R. Seed characterization of five new pomegranate varieties. Sci Hort. 2006;110:241–246. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2006.07.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal V, DerMarderosian A, Porter JR. Anthocyanins and polyphenol oxidase from dried arils of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) Food Chem. 2010;118:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.01.095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Said FA, Opara LU, Al-Yahyai RA. Physico-chemical and textural quality attributes of pomegranate cultivars (Punica granatum L.) grown in the Sultanate of Oman. J Food Eng. 2009;90:129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2008.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Guo C, Yang J, Wei J, Xu J, Cheng S. Evaluation of antioxidant properties of pomegranate peel extract in comparison with pomegranate pulp extract. Food Chem. 2006;96:254–260. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.02.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hajimahmoodi M, Oveisi MR, Sadeghi N, Jannat B, Hajibabi M, Farahani E, Akrami MR, Namdar R. Antioxidant properties of peel and pulp hydro extract in ten Persian pomegranate cultivars. Pak J Biol Sci. 2008;11:1600–1604. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2008.1600.1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gözlekçi Ş, Saraçoğlu O, Onursal E, Özgen M. Total phenolic distribution of juice, peel, and seed extracts of four pomegranate cultivars. Phcog Mag. 2011;7:161–164. doi: 10.4103/0973-1296.80681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackland ML, Van DeWaarsenburg S, Jones R. Synergistic antiproliferative action of the flavonols quercetin and kaempferol in cultured human cancer cell lines. In Vivo. 2005;19:69–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski I, Samojedny A, Paul M, Pietsz G, Wilczok T. Effect of kaempferol on the production and gene expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in J7742 macrophages. Pharmacol Rep. 2005;57:107–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusselmans K, Vrolix R, Verhoeven G, Swinnen JV. Induction of cancer cell apoptosis by flavonoids is associated with their ability to inhibit fatty acid synthase activity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5636–5645. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408177200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarrell EM, Gould SWJ, Fielder MD, Kelly AF, El-Sankary W, Naughton DP. Antimicrobial activities of pomegranate rind extracts: enhancement by addition of metal salts and vitamin C. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2008;8:64. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-8-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo EH, Cortéz DAG, Ueda-Nakamura T, Nakamura CV, Filho BPD. Potent antifungal activity of extracts and pure compound isolated from pomegranate peels and synergism with fluconazole against Candida albicans. Res Microbiol. 2010;161:534–540. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olapour S, Mousavi E, Sheikhzade M, Hoseininezhad O, Najafzadeh H. Evaluation anti-diarrheal effects of pomegranate peel extract. J Iran Chem Soc. 2009;6:115–143. [Google Scholar]

- Lin CC, Hsu YF, Lin TC. Effects of punicalagin on arrageenan-induced inflammation in rats. Am J Chinese Med. 1999;27:371–376. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X99000422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeram NP, Adams LS, Henning SM, Niu Y, Zhang Y, Nair MG, Heber D. In vitro anti-proliferative, apoptotic and antioxidant activities of punicalagin, ellagic acid and a total pomegranate tannin extract are enhanced in combination with other polyphenols as found in pomegranate juice. J Nutr Biochem. 2005;16:360–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura M, Watanabe Y, Kasai K, Yamakoshi J, Koga T. Inhibitory effect of an ellagic acid-rich pomegranate extracts on tyrosinase activity and ultraviolet-induced pigmentation. Biosci, Biotechnol, Biochem. 2005;69:2368–2373. doi: 10.1271/bbb.69.2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansky EP, Newman RA. Punica granatum (pomegranate) and its potential for prevention and treatment of inflammation and cancer. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;109:177–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Althunibat OY, Al-Mustafa AH, Tarawneh K, Khleifat KM, Ridzwan BH, Qaralleh HN. Protective role of Punica granatum L peel extract against oxidative damage in experimental diabetic rats. Process Biochem. 2010;45:581–585. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2009.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Viuda-Martos M, Fernandez-Lopez J, Perez-Alvarez JA. Pomegranate and its many functional components as related to human health: A Review. Compr Rev Food Sci. 2010;9:635–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2010.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland D, Hatib K, Bar-Ya’akov I. Pomegranate: botany, horticulture, breeding. Horticultural Reviews. 2009;35:127–191. [Google Scholar]

- Fawole OA, Opara UL, Theron KI. Chemical and phytochemical properties and antioxidant activities of three pomegranate cultivars grown in South Africa. Food Bioprocess Tech. 2012;5:425–444. doi: 10.1007/s11947-011-0697-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Zoreky NS. Antimicrobial activity of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) fruit peels. Int J Food Microbiol. 2009;134:244–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eloff JN. A sensitive and quick microplate method to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration of plant extracts for bacteria. Planta Med. 1998;64:711–713. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawole OA, Finnie JF, Van Staden J. Antimicrobial activity and mutagenic effects of twelve traditional medicinal plants used to treat ailments related to the gastro-intestinal tract in South Africa. S Afr J Bot. 2009;75:356–362. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2008.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karioti A, Hadjipavlou-Litina D, Mensah MLK, Fleischer TC, Saltsa H. Composition and antioxidant activity of the essential oils of Xylopia aethiopica (Dun) A. Rich. (Annonaceae) leaves stem bark, root bark, and fresh and dried fruits, growing in Ghana. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52:8094–8098. doi: 10.1021/jf040150j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh N, Rajini PS. Free radical scavenging activity of an aqueous extract of potato peel. Food Chem. 2004;85:611–616. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2003.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benzie IFF, Strain JJ. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power” The FRAP assay. Anal Biochem. 1996;239:70–76. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momtaz S, Mapunya BM, Houghton PJ, Edgerly C, Hussein A, Naidoo S, Lall N. Tyrosinase inhibition by extracts and constituents of Sideroxylon inerme L Stem bark, used in South Africa for skin lightening. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;119:507–512. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton VL, Rossi JA Jr. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolibdic phosphotungtic acid reagents. Am J Enol Viticult. 1965;16:144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Makkar HPS. Quantification of tannins in tree foliage: A laboratory manual for the FAO/IAEA coordinated research project on ‘Use of nuclear and related techniques to develop simple tannin assay for predicting and improving the safety and efficiency of feeding ruminants on the tanniniferous tree foliage’ Joint FAO/IAEA division of nuclear techniques in food and agriculture. 2000. (Vienna, Austria).

- Yang J, Martinson TE, Liu RH. Phytochemical profiles and antioxidant activities of wine grapes. Food Chem. 2009;116:332–339. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.02.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wrolstad RE. Agricultural experiment station: Oregon State University, Station Bulletin. Color and Pigment Analyses in Fruit Products. 1993;624:14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer UA, Carle R, Kammerer DR. Identification and quantification of phenolic compounds from pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) peel, mesocarp, aril and differently produced juices by HPLC-DAD–ESI/MSn. Food Chem. 2011;127:807–821. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.12.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Vuuren SF. Antimicrobial activity of South African medicinal plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;119:462–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opara LU, Al-Ani MR, Al-Shuaibi Y. Physico-chemical Properties, Vitamin C content, and antimicrobial properties of pomegranate fruit (Punica granatum L.) Food Bioprocess Tech. 2009;2:315–321. doi: 10.1007/s11947-008-0095-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanatt SR, Chander R, Sharma A. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of pomegranate peel extract improves the shelf life of chicken products. Int J Food Sci Tech. 2010;45:216–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2009.02124.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel MG, Neves MA, Antunes MD. Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.): A medicinal plant with myriad biological properties - A short review. J Med Plants Res. 2010;4:2836–2847. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos NS. Antimicrobial activity of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) fruit peels. Int J Food Microbiol. 2009;134:244–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viljoen AM, Subramoney S, Van Vuuren SF, Baser KHC, Demicri B. The composition, geographical variation and antimicrobial activity of Lippia javanica. Verbenaceae leaf essential oils. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;96:271–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field KJ, Lake JA. Environmental metabolomics links genotype to phenotype and predicts genotype abundance in wild plant populations. Physiol Plant. 2011;142:352–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2011.01480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negi PS, Jayaprakasha GK. Antioxidant and antibacterial activities of Punica granatum peel extracts. J Food Sci. 2006;68:1473–1477. [Google Scholar]

- Okonogi S, Duangrat C, Anuchpreeda S, Tachakittirungrod S, Chowwanapoonpohn S. Comparison of antioxidant capacities and cytotoxicities of certain fruit peels. Food Chem. 2007;103:839–846. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.09.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gil MI, Tomas-Barberan FA, Hess-Pierce B, Holcroft DM, Kader AAL. Antioxidant activity of pomegranate juice and its relationship with phenolic composition and processing. Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:4581–4589. doi: 10.1021/jf000404a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang T-S. An updated review of tyrosinase inhibitors. Int J Mol Sci. 2009;10:2440–2475. doi: 10.3390/ijms10062440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo I, Kinst-Hori I, Kubo Y, Yamagiwa Y, Kamikawa T, Haraguchi H. Molecular design of antibrowning agents. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:1393–1399. doi: 10.1021/jf990926u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meda A, Lamien CE, Romito M, Millogo J, Nacoulma OG. Determination of the total phenolic, flavonoid and proline Contents in Burkina Fasan Honey, as well as their radical scavenging activity. Food Chem. 2005;91:571. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Afaq F, Saleem M, Krueger CG, Reed JD, Mukhtar H. Anthocyanin and hydrolyzable tannin-rich pomegranate fruit extract modulates MAPK and NF-kappa B pathways and inhibits skin tumorigenesis in CD-1 mice. Int J Cancer. 2005;113:423–433. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman AD, Ozgen M, Dayisoylu KS, Erbil N, Durgac C. Antimicrobial activity of six pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) varieties and their relation to some of their pomological and phytonutrient characteristics. Molecules. 2009;14:1808–1817. doi: 10.3390/molecules14051808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, Xu H, Liu X, He W, Yuan F, Hou Z, Gao Y. Identification of phenolic compounds from pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) seed residues and investigation into their antioxidant capacities by HPLC–ABTS+ assay. Food Res Int. 2011;44:1161–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2010.05.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noda Y, Kaneyuki T, Mori A, Packer L. Antioxidant activities of pomegranate fruit extract and its anthocyanidins: delphinidin, cyanidin, and pelargonidin. Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:166–171. doi: 10.1021/jf0108765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauha J, Remes S, Heinonen M, Hopia A, Kähkönen M, Kujala T, Pihlaja K, Vuorela H, Vuorela P. Antimicrobial effects of Finnish plant extracts containing flavonoids and other phenolic compounds. Int J Food Microbiol. 2000;56:3–12. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(00)00218-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]