Abstract

Burkholderia glumae causes bacterial panicle blight of rice and produces major virulence factors, including toxoflavin, under the control of the quorum-sensing (QS) system mediated by the luxI homolog, tofI, and the luxR homolog, tofR. In this study, a series of markerless deletion mutants of B. glumae for tofI and tofR were generated using the suicide vector system, pKKSacB, for comprehensive characterization of the QS system of this pathogen. Consistent with the previous studies by other research groups, ΔtofI and ΔtofR strains of B. glumae did not produce toxoflavin in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth. However, these mutants produced high levels of toxoflavin when grown in a highly dense bacterial inoculum (∼ 1011 CFU/ml) on solid media, including LB agar and King’s B (KB) agar media. The ΔtofI/ΔtofR strain of B. glumae, LSUPB201, also produced toxoflavin on LB agar medium. These results indicate the presence of previously unknown regulatory pathways for the production of toxoflavin that are independent of tofI and/or tofR. Notably, the conserved open reading frame (locus tag: bglu_2g14480) located in the intergenic region between tofI and tofR was found to be essential for the production of toxoflavin by tofI and tofR mutants on solid media. This novel regulatory factor of B. glumae was named tofM after its homolog, rsaM, which was recently identified as a novel negative regulatory gene for the QS system of another rice pathogenic bacterium, Pseudomonas fuscovaginae. The ΔtofM strain of B. glumae, LSUPB286, produced a less amount of toxoflavin and showed attenuated virulence when compared with its wild type parental strain, 336gr-1, suggesting that tofM plays a positive role in toxoflavin production and virulence. In addition, the observed growth defect of the ΔtofI strain, LSUPB145, was restored by 1 µM N-octanoyl homoserine lactone (C8-HSL).

Introduction

Burkholderia glumae, the primary causal agent of bacterial panicle blight (BPB) of rice, is one of the most important disease problems affecting rice production in the southern United States, including Louisiana, Arkansas and Texas [1]. This rice disease has also been reported from many rice-growing areas around the world, including east Asia, southeast Asia and South America [1]. The optimal temperature range for the growth of B. glumae is 38–40°C, but this bacterium can also grow at temperatures as high as 50°C [2]. A typical characteristic of B. glumae is the production of the bright yellow phytotoxin, toxoflavin, which is a major virulence factor of this pathogen [3]–[6].

In B. glumae, production of major virulence factors, including toxoflavin, is dependent on the quorum-sensing (QS) system mediated by a pair of LuxI and LuxR homologs, TofI and TofR [4], [7], [8]. QS is a cell-to-cell communication mechanism that allows bacterial cells to collectively behave like a multicellular organism. In Gram-negative bacteria, QS systems mediated by LuxI and LuxR-family proteins are involved in a diverse range of bacterial behaviors and traits, including formation of biofilm, production of virulence factors, conjugation, and antibiosis [9], [10]. The LuxI/LuxR system, which is considered the prototype of the QS systems of Gram-negative bacteria, was first discovered from Vibrio fischeri, a luminous symbiont in marine animals [11], [12]. LuxI-family proteins are synthases that produce N-acyl homoserine lactone (AHL)-type intercellular signal molecules; LuxR-family proteins are cognate receptors that specifically bind to the AHL molecules [13].

Two types of AHL molecules, N-octanoyl homoserine lactone (C8-HSL) and N-hexanoyl homoserine lactone (C6-HSL), are synthesized by the LuxI-family protein of B. glumae, TofI [4]. It is thought that the LuxR-family protein of B. glumae, TofR, specifically binds to C8-HSL and the resultant TofR-C8-HSL complex triggers the production of toxoflavin by activating the transcription of toxJ, which has a lux box-like cis element (tof-box) upstream of the coding sequence for the binding of the TofR-C8-HSL complex [4]. Unlike C8-HSL, functions of C6-HSL in B. glumae and other Burkholderia spp. remain unknown. ToxJ encoded by toxJ is required for the transcription of toxR; and ToxR, a LysR-type transcriptional regulator, in turn activates the expression of the toxABCDE and toxFGHI operons, which harbor gene clusters for toxoflavin biosynthesis and transport, respectively [4]. This regulatory cascade (the TofI/TofR QS system → ToxJ → ToxR → toxABCDE and toxFGHI) is considered to be the central regulatory system for the production of toxoflavin, which may allow B. glumae to attack host cells in accordance with its population levels at infection sites [4]. Nevertheless, the genetic functions of tofI and tofR as well as additional components of the QS system governing the expression of bacterial virulence genes in B. glumae are not fully understood.

In this study, a series of deletion mutants deleted in the QS genes, tofI and tofR, were successfully generated from the U.S. virulent strain, 336gr-1 [2], for the further characterization of the QS system and the related global regulatory network in B. glumae. Through the genetic analyses conducted in this study, previously unknown tofI- and/or tofR-independent pathways for the production of toxoflavin were revealed and a new regulatory gene required for these pathways, tofM, was discovered between the tofI and tofR loci.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, Media and Growth Conditions

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. All the Escherichia coli and B. glumae strains were routinely grown or maintained in LB broth or on LB agar plates [14] at 30°C or 37°C (even though the original definition of LB was corrected by Bertani as ‘lysogeny broth’ [15], the terms, ‘LB broth’ and ‘LB agar’, are used to clearly contrast two different growth conditions tested in this study). Bacterial strains grown in liquid media were incubated in a shaking incubator at 200 rpm. LB agar plates amended with 30% sucrose were used to counter-select the recombinant mutants that lost the sucrose-sensitive gene, sacB, through the secondary homologous recombination. The levels of bacterial growth and toxoflavin production in liquid or solid media were determined in four different growth conditions; LB alone, LB with 1 µΜ C6-HSL (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); LB with 1 µΜ C8-HSL (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); and LB with both 1 µΜ C6-HSL and 1 µΜ C8-HSL. The antibiotics and their working concentrations used in this study were: ampicillin (Amp), 100 µg/ml; kanamycin (Km), 50 µg/ml; nitrofurantoin (Nit), 100 µg/ml; gentamycin (Gm), 20 µg/ml; and tetracycline (Tc), 20 µg/ml.

Table 1. Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strain or Plasmid | Description | Reference |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| DH10B | F− araD139 Δ(ara, leu)7697 ΔlacX74 galU galK rpsL deoR ø80dlacZΔM15 endA1 nupG recA1 mcrA Δ(mrr hsdRMS mcrBC) | [28] |

| DH5α | F− endA1 hsdR17 (rk −, mk +) supE44 thi-1 λ − recA1 gyrA96 relA1 deoR Δ (lacZYA-argF)-U169 ø80dlacZΔM15 | [28] |

| S17-1λpir | recA thi pro hsdR [res- mod+][RP4::2-Tc::Mu-Km::Tn7] λ pir phage lysogen, Smr/Tpr | [29] |

| Burkholderia glumae | ||

| 336gr-1 | Wild type strain isolated from diseased rice in Crowley, Louisiana, USA | This study |

| LSUPB139 | A ΔtofI-tofR derivative of 336gr-1 | This study |

| LSUPB145 | A ΔtofI derivative of 336gr-1 | This study |

| LSUPB169 | A ΔtofR derivative of 336gr-1 | This study |

| LSUPB201 | A ΔtofI/ΔtofR derivative of 336gr-1 | This study |

| LSUPB286 | A ΔtofM derivative of 336gr-1 | This study |

| LSUPB292 | A ΔtofR/ΔtofM derivative of 336gr-1 | This study |

| LSUPB293 | A ΔtofI/ΔtofM/ΔtofR derivative of 336gr-1 | This study |

| LSUPB294 | A ΔtofI/ΔtofM derivative of 336gr-1 | This study |

| Chromabacterium violaceum | ||

| C. violaceum CV026 | A biosensor that produces a purple pigment in the presence of AHL molecules | [20] |

| Plasmid | ||

| pBBR1MCS-2 | A broad host range cloning vector, RK2 ori, lacZα, KmR | [30] |

| pBBR1MCS-5 | A broad host range cloning vector, RK2 ori, lacZα, GmR | [30] |

| pBBtofIM | A subclone of pBBtofIMR for the 2,808-bp tofI/tofM region inserted into pBBR1MCS-5 at theBglII and SacI sites, GmR | This study |

| pBBtofIMR | A subclone of pCos808 for the 3,670-bp tofI/tofM/tofR region inserted into pBBR1MCS-2 atthe EcoRI and SacI sites, KmR | This study |

| pBBtofM | A tofM clone in pBBR1MCS-5, GmR | This study |

| pBBtofRM | A subclone of pBBtofIMR for the 1,925-bp tofR/tofM region inserted intopBBR1MCS-2 at the EcoRI and PvuII sites, KmR | This study |

| pCos808 | The cosmid clone harbouring tofI, tofM and tofR, AmpR | This study |

| pJP5603 | A suicide vector, R6K γ-ori, RP4 oriT, lacZ’, KmR | [31] |

| pJPtofIUD | A suclone of pLDtofIUD containing the upstream and downstream flanking regions of tofI in pGP5603, KmR | This study |

| pKKSacB | A suicide vector; R6K γ-ori, RP4 oriT, sacB, KmR | (Ham andBarphagha, unpublished) |

| pKKSacBΔtofI | A subclone of pJPtofIUD for the upstream and downstream flanking regions of tofI in pKKSacB, KmR | This study |

| pKKSacBΔtofIMR | A subclone of pLDtofIDRD carrying the downstream flanking regions of tofI and tofR in pKKSacB, KmR | This study |

| pKKSacBΔtofM | A plasmid carrying the upstream and downstream flanking regions of tofM in pKKSacB, KmR | This study |

| pKKSacBΔtofR | A subclone of pKKtofRUD for the upstream and downstream flanking regions of tofR in pKKSacB, KmR | This study |

| pKKSacBtofMU | A subclone of pSCtofMU for a upstream flanking region of tofM in pKKSacB, KmR | This study |

| pKKtofRD | A subclone of pSCtofRD for the downstream flanking region of tofR in pKNOCK-Km, KmR | This study |

| pKKtofRUD | A subclone of pSCtofRU for the upstream flanking region of tofI in pKKtofRD, KmR | This study |

| pKNOCK-Km | A suicide vector; R6K γ-ori, RP4 oriT, KmR | [32] |

| pLD55 | A suicide vector; f1 ori, R6K γ-ori, RP4 oriT, lacZα, AmpR, TcR | [19] |

| pLDtofID | A subslone of pSCtofID for the downstream flanking region of tofI in pLD55, AmpR, TcR | This study |

| pLDtofIDRD | A subclone of pSCtofRD for the downstream flanking region of tofR in pLDtofID, AmpR, TcR | This study |

| pLDtofIUD | A subclone of pSCtofIU for the upstream flanking region of tofI in pLDtofID, AmpR, TcR | This study |

| pRK2013::Tn7 | A helper plasmid; ColE1 ori | [16] |

| pSC-A-amp/kan | A blunt-end PCR cloning vector; f1 ori, pUC ori, lacZ’, KmR, AmpR | Stratagene |

| pSCtofID | A clone of the 512 bp downstream flanking region of tofI in pSC-A-amp/kan, AmpR, KmR | This study |

| pSCtofIU | A clone of the 545-bp upstream flanking region of tofI in pSC-A-amp/kan, AmpR, KmR | This study |

| pSCtofM | A clone containing the 986-bp region of tofM and its upstream region, AmpR, KmR | This study |

| pSCtofMD | A PCR clone of the 412-bp downstream flanking region of tofM in pSC-A-amp/kan, AmpR, KmR | This study |

| pSCtofMU | A PCR clone of the 433-bp upstream flanking region of tofM in pSC-A-amp/kan, AmpR, KmR | This study |

| pSCtofRD | A clone of the 829-bp downstream flanking region of tofR in pSC-A-amp/kan, AmpR, KmR | This study |

| pSCtofRU | A clone of the 426-bp upstream flanking region of tofR in pSC-A-amp/kan, AmpR, KmR | This study |

Recombinant DNA Techniques

Routine DNA cloning and amplification procedures were conducted following standard methods [14]. PCR products used for cloning were purified using the QuickClean 5 M PCR Purification Kit (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ, USA) and cloned into pSC-A-amp/kan using the Strata Clone™ PCR cloning kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Genomic DNA of the wild type and mutant strains were extracted using the GenElute™ Bacterial Genomic DNA kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Electroporation for transforming E. coli cells was conducted with a GenePulser unit (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) at 1.5 kV with 2 µl DNA and 25 µl competent cells. Triparental mating using the helper plasmid, pRK2013::Tn7 [16], was used to transform B. glumae [17]. DNA were extracted from agarose gels using the GenElute™ Gel Extraction Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). DNA sequencing was performed by the LSU School of Veterinary Medicine Gene Lab. DNA concentrations were measured using a NanoDrop DN-1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). The genomic library of B. glumae 336gr-1 was created previously in our laboratory [18].

Allelic Exchange of the B. glumae Genome for Targeted Deletions

A DNA construct in pKKSacB for deleting a target gene(s) was first introduced into a parental B. glumae strain via conjugation, following a previously described method [18]. Because B. glumae is resistant to Nit and pKKSacB contains a Km-resistance gene, the recombinant B. glumae strain in which a DNA construct in pKKSacB is integrated in the genome via single homologous recombination was initially selected on LB agar medium containing Km and Nit. Subsequently, the selected strain was grown overnight at 30°C in LB broth without any antibiotics. To select the mutants with secondary homologous recombination between the integrated DNA construct and the genome, which would result in the eviction of the integrated DNA construct and consequently the deletion of the target gene(s), the overnight culture was spread on LB agar medium containing 30% sucrose to select sucrose-resistant colonies. Individual sucrose-resistant colonies of B. glumae were then tested for the sensitivity to Km to screen marker-less deletion mutants. Deletion of target gene(s) in each of the selected Km-sensitive and sucrose-resistant mutants was confirmed by the appropriate diagnostic PCRs. Deletions of tofI, tofR, tofM were confirmed using the primer sets, TofI(H)F/TofI(H)R, TofR(H)F/TofR(H)R, and orf1-CT-F/orf1-CT-R, respectively, while the deletion of the entire tofI-tofR region in LSUPB139 was confirmed using the primer set, TofI(H)F/TofR(H)R. Primer sequences and PCR conditions for individual primer sets are described in Table 2.

Table 2. Primers and PCR conditions used in this study.

| Primer name | Primers* (5′ → 3′) | Annealing and extension conditions |

| dtof1 | ACTGGTACC TCGAACCCGACTCCG | Annealing: 60°C/30 sExtension: 72°C/1 min |

| dtof2 | GGATCC AGCTCGGCGGCGATATGG | |

| dtofI3 | GGATCC ACATCGACGCGCAGACGC | Annealing: 62°C/30 sExtension: 72°C/1 min |

| dtofI4 | GCACTAGTATCCGCCCGAGATCCG | |

| TRD3 | GGATCC GCGCGAACGCGAGGTGC | Annealing: 65°C/30 sExtension: 72°C/1 min |

| TRD6 | ACTAGT ACGGCGTGACCGGCGTC | |

| TofR BF | AGGATCCGCTGCTCGTTTTCC | Annealing: 55°C/30 sExtension: 72°C/1 min |

| TofR BR | GACTAGTATCAGATTGCTGCG | |

| TofI(H)F | GTTCGTCAACGACGACTACG | Annealing: 53°C/30 secExtension: 72°C/2.5 min |

| TofR(H)R | CATGAGCATGGAAAAGAGCA | |

| TofI(H)F | GTTCGTCAACGACGACTACG | Annealing: 54°C/30 sExtension: 72°C/1 min |

| TofI(H)R | CGGAATTACCACGAGGACAC | |

| orf1-CT-F | ATGGTCAACAGTCCGAACACGC | Annealing: 58°C/30 sExtension: 72°C/1 min |

| orf1-CT-R | TCATGGGCTGCTTAAACGCAGAAG | |

| TofR(H)F | AAGAATGACAGCGTGGAAGC | Annealing: 50°C/30 sExtension: 72°C/1 min |

| TofR(H)R | CATGAGCATGGAAAAGAGCA | |

| tofI-jh1 | GTCTACGTATTGGGACGCGAT | Annealing: 55°C/30 sExtension: 72°C/30 s |

| tofI-jh2 | ACAGCCGCTCGATGCTGCAGA | |

| UPHP- FP | GGATCC ACATGCCGAAGTC | Annealing: 50°C/30 sExtension: 72°C/1 min |

| UPHP- RP | ACTAGT GTAGGGATGAAGCA | |

| DwN-FP | ACTAGT CGCTGGTCGCAC | Annealing: 50°C/30 sExtension: 72°C/1 min |

| DwN-RP | TCTAGA GAATTTTTCGTCTTC |

Restriction sites (underlined) introduced in primers: GGTACC (KpnI), GGATCC (BamHI), ACTAGT (SpeI), and TCTAGA (XbaI). Default PCR conditions were: initial denaturation, 95°C/5 min; denaturation, 94°C/30 s; number of cycles, 30; and final extension, 72°C/7 min.

DNA Constructs for the Targeted Deletions of tofI, tofM, and tofR

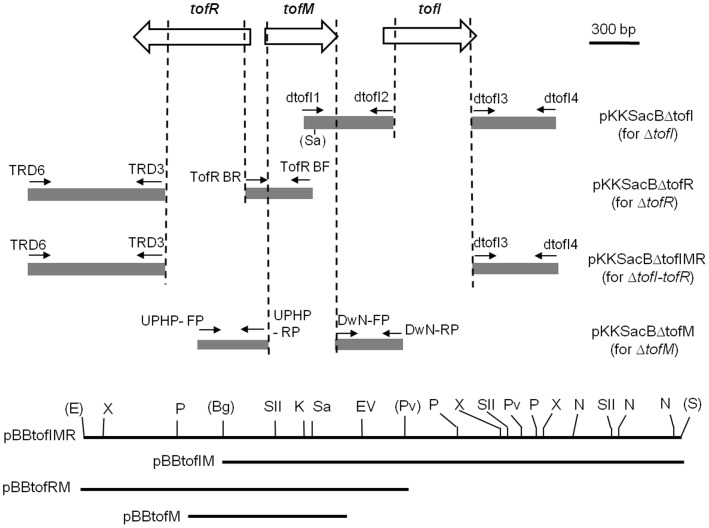

DNA constructs for deletion mutations and deletion mutants of B. glumae generated in this study are listed in Table 1. PCR primers used to create and confirm deletion mutations are listed in Table 2. All deletion mutants generated in this study were obtained through double-crossover homologous recombination in the flanking regions of targeted genes (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A schematic view of the tofI, tofM, and tofR loci and the DNA constructs used for deletion mutation and genetic complementation.

The grey areas indicate the flanking regions cloned in pKKSacB for individual or combined deletions of tofI, tofM, and tofR. The genomic regions to be deleted with the DNA constructs in pKKSacB are indicated with vertical hatched lines, while those cloned in a broad host vector, pBBR1MCS-2 or pBBR1MCS-5, for complementation tests are indicated with horizontal solid lines. Small arrows indicate the primers (Table 2) used for the amplification of each flanking region. Abbreviation for restriction sites are as follows: Bg, BglII; E, EcoRI; EV, EcoRV; K, KpnI; N, NotI; P, PstI; Pv, PvuII; S, SacI; Sa, SalI; SII, SacII; X, XhoI. Restriction sites used for generating pBBtofIMR, pBBtofIM, and pBBtofRM are denoted with parentheses.

To construct pKKSacBΔtofI that was used to create the tofI deletion mutants, a 545-bp region upstream and a 512-bp region downstream of tofI were amplified with the primer sets, dtofI1/dtofI2 and dtofI3/dtofI4, respectively (Table 2). The resultant PCR products for these tofI flanking sequences were initially cloned into pSC-A-amp/kan to generate pSCtofIU and pSCtofID. The downstream region of tofI in pSCtofID was then sub-cloned into pLD55 [19] using BamHI and SpeI sites to get pLDtofID. The upstream region of tofI in pSCtofIU was cut with KpnI and BamHI and was then ligated to pLDtofID, cut with the same restriction sites, to generate pLDtofIUD. Because initial attempts to generate a tofI deletion mutant with pLDtofIUD using the tetracycline-resistant gene in pLD55 as a counter-selection marker in the presence of fusaric acid [19] failed, the deletion construct cloned into pLD55 was moved to pKKSacB through the following steps: the 1.1-kb KpnI/XbaI-cut fragment from pLDtofIUD was first ligated to pJP5603, cut with KpnI and XbaI, to generate pJPtofIUD and increase the choice of restriction sites for the final cloning into pKKSacB; the 1.1-kb SalI-cut fragment derived from the native SalI site present 68 bp downstream from the 5′ end of the tofI upstream region cloned into pJPtofIUD and the SalI site in the polylinker region of the same plasmid was then ligated into pKKSacB, cut with SalI, to obtain pKKSacBΔtofI.

To construct pKKSacBΔtofR that was used to create the tofR deletion mutants, a 426-bp region upstream and an 829-bp region downstream of tofR were amplified with the primer sets, TofR BF/TofR BR and TRD6/TRD3, respectively (Table 2). The resultant PCR products were cloned into pSC-A-amp/kan to generate pSCtofRU and pSCtofRD, respectively. The downstream region of tofR in pSCtofRD was removed using the BamHI site in the primer and the PstI site in the polylinker region of the plasmid and subsequently ligated to pKNOCK-Km, cut with BamHI and PstI, to get pKKtofRD. The upstream region of tofR in pSCtofRU, obtained from SpeI and BamHI digestion, was then cloned into pKKtofRD using the same restriction sites, to generate pKKtofRUD. Finally, the SpeI-cut 1.3-kb DNA fragment containing the recombined flanking regions of tofR from pKKtofRUD was cloned to pKKSacB at the SpeI site to obtain pKKSacBΔtofR.

To construct pKKSacBΔtofM that was used to create the tofM deletion mutants, a 433-bp region upstream and a 412-bp region downstream of tofM were amplified with the primer sets, UPHP-FP/UPHP-RP and DwN-FP/DwN-RP, respectively (Table2). The amplified PCR products were initially cloned into pSC-A-amp/kan to generate pSCtofMU and pSCtofMD, respectively (Table 2). The upstream region of tofM, obtained by BamHI and SpeI digestions of pSCtofMU, was cloned into pKKSacB at the BamHI and SpeI sites to get pKKSacBtofMU. The downstream region of tofM, cut from pSCtofMD by SpeI and XbaI, was then ligated to pKKSacBtofMU, cut with SpeI and XbaI, to obtain pKKSacBΔtofM.

To construct pKKSacBΔtofIMR that was used for the deletion of the entire tofI-tofR region, the downstream region of tofR in pSCtofRD was obtained by KpnI and BamHI digestions and subsequently ligated into pLDtofID, cut with KpnI and BamHI, to get pLDtofIDRD. The 1.3-kb DNA fragment that resulted from the SpeI digestion of pLDtofIDRD was then ligated to the SpeI-cut pKKSacB to obtain the final deletion construct, pKKSacBΔtofIMR.

DNA Constructs for the Complementation of the QS Mutants

A cosmid library of the B. glumae 336gr-1 genome was screened with the primers, tofI-jh1 and tofI-jh2, to identify the cosmid clone that contains tofI. The cosmid clone, pCos808, was identified to contain tofI as well as tofR and tofM. pBBtofIMR, which contains tofI, tofM, and tofR, was constructed by cloning a 3,670-bp DNA fragment containing tofI, tofM, and tofR from Cos809 into pBBRMCS-2 using the EcoRI and SacI sites. pBBtofIM was generated by subcloning the 2,808-bp tofI/tofM region of pBBtofIMR into pBBRMCS-5 using BglII and SacI sites. pBBtofRM was constructed by subcloning the 1,925-bp tofR/tofM region of pBBtofIMR in pBBRMCS-2 using EcoRI and PvuII sites. For pBBtofM, a 986-bp region that includes tofM was amplified using the primers orf1-CT-F and orf1-CT-R (Figure 1 and Table 2). The PCR products were initially cloned into the pSC-A-amp/kan vector following the manufacturer’s protocol to generate pSCtofM. Then, the tofM region of pSCtofM was subcloned into pBBR1MCS-5 using SpeI and HindIII sites to get pBBtofM.

For complementation, each of these constructs was introduced into the appropriate B. glumae strain through triparental mating [18].

AHL Production Assays

Chromobacterium violaceum CV026, which produces the purple pigment, violacein, in the presence of AHL molecules [20], was used as a biosensor to determine the AHL production by B. glumae. The AHL production assay was performed following the procedure used by Kim et al. (2004) with some modifications. Briefly, the supernatant fraction of an overnight culture of each B. glumae strain grown in LB broth at 37°C obtained after centrifugation was extracted with an equal volume of ethyl acetate, air-dried in a fume hood, and the residue dissolved in 1% volume of sterile distilled deionized water. Then, 20 µl of each culture extract were applied to the cells of C. violaceum CV026 immediately after they were inoculated on a LB agar plate. The production of the purple pigment by this biosensor strain was observed after 48 h incubation at 30°C.

Quantification of Bacterial Growth

To quantify bacterial growth in liquid and solid media, an equal amount of overnight culture per volume of medium was applied to liquid and solid media (∼106 cell/ml medium). For solid medium, 12.5 µl of an overnight culture were spread on an LB agar plate containing approximately 12.5 ml of LB agar. For liquid media, 3 µl of the same overnight culture were added to 3 ml LB broth. After incubation at 37°C for 24 h, bacterial growth was determined by measuring the absorbance of the bacterial culture suspension at 600 nm (OD600). Overnight cultures in LB broth were measured directly. Cultures grown on LB agar plates were resuspended in 12.5 ml of fresh LB broth and then measured for OD600.

Quantification of Toxoflavin Production

Toxoflavin production by each strain of B. glumae was quantified following a previously established method [4] with some modifications for cultures grown in both liquid and solid media. For bacteria grown in LB broth, toxoflavin present in the supernatant obtained from the centrifugation of 1 ml of culture was extracted with 1 ml of chloroform. Following centrifugation, the chloroform fraction was transferred to a new microtube and air-dried in a fume hood. The residue in the microtube was dissolved in 1 ml of 80% methanol. For bacteria grown on LB agar, bacterial cells were removed from the surface of the agar and the remaining agar containing the diffused toxoflavin was cut into small pieces with a razorblade. The chopped agar was then mixed with chloroform in 1∶1 (w/v) ratio for toxoflavin extraction and the chloroform fraction was filtered through filter paper and collected in a new microtube. Chloroform was evaporated and culture filtrate residue was dissolved in 80% methanol as previously described. The absorbance of each sample was measured at 393 nm to determine the relative amount of toxoflavin [21].

Virulence Tests for B. Glumae

The onion assay system that was previously used to determine the virulence of Burkholderia cenocepacia [22] and B. glumae [18], [23] was adopted in this study with minor modifications. Briefly, the fleshy scales of yellow onions were cut into pieces (∼2×4 cm) with a sterile razorblade and a 2 mm-slit was made in the center of each onion piece with a sterile micropipette tip. Two microliters of bacterial suspensions made from cultures grown on a LB agar plate, suspended in 10 mM MgCl2 and adjusted to 5×107 CFU/ml, were applied to the slit on each piece of onion scale. The inoculated onion scales were incubated in a moist chamber at 30°C for 72 h. The virulence level of each B. glumae strain was assessed by measuring the area of maceration on each onion scale. Virulence of B. glumae strains in rice was tested following a previously established method [23].

Results

Generation of a Series of Markerless Deletion Mutants of tofI and tofR

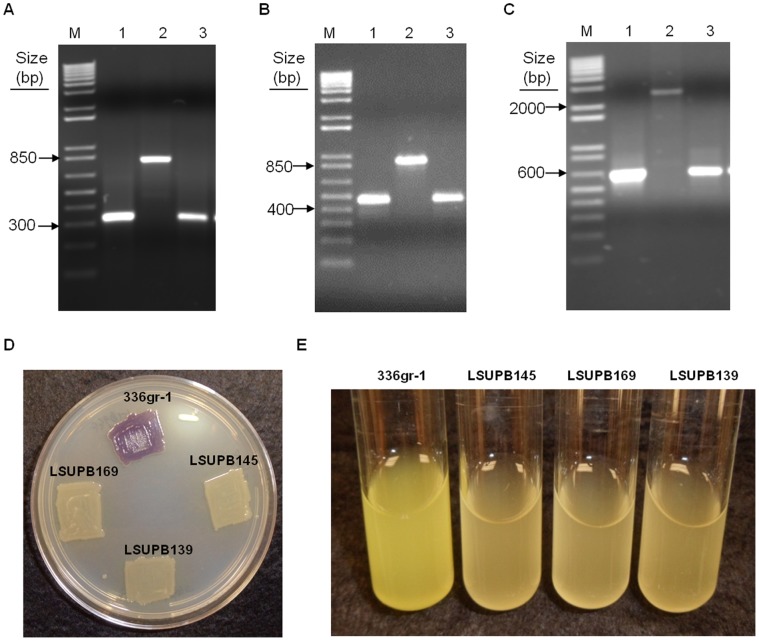

Mutant derivatives of B. glumae 336gr-1 with deleted tofI, tofR, or the entire tofI-tofR region, including the intergenic region, were generated using the pKKSacB system (Ham and Barphagha, unpublished), following the procedures described in the Materials and Methods section (Table 1 and Figure 1). Genetic confirmation of the deletion mutants, LSUPB145 (ΔtofI), LSUPB169 (ΔtofR), and LSUPB139 (ΔtofI-tofR), was performed using PCR and primers corresponding to the DNA sequences flanking each deleted region (Figure 2 and Table 2). The size of the PCR products amplified from each mutant was the same as that of the PCR products amplified from the DNA construct used for the corresponding deletion mutation, and the size difference of the PCR products between the wild type and each mutant was matched to the predicted size of the deleted DNA sequence (Figure 2).

Figure 2. PCR products from diagnostic PCRs used to confirm deletion mutations in Burkholderia glumae and N-acyl homoserine lactone (AHL) signal production and toxoflavin production of deletion mutants.

(A) PCR products amplified from primers, TofI(H)F and TofI(H)R, to confirm the tofI deletion in LSUPB145. Template DNA for each lane is as follows: 1, pKKSacBΔtofI; 2, genomic DNA of B. glumae 336gr-1; and 3, genomic DNA of B. glumae LSUPB145. (B) PCR products amplified with primers, TofR(H)F and TofR(H)R, to confirm the tofR deletion in LSUPB169. Template DNA for each lane is as follows: 1, pKKSacBΔtofR; 2, genomic DNA of B. glumae 336gr-1; and 3, genomic DNA of B. glumae LSUPB169. (C) PCR products amplified with primers, TofI(H)F and TofR(H)R, to confirm the tofI-tofR deletion in LSUPB139. Template DNA for each lane is as follows: 1, pKKSacBΔtofIMR; 2, genomic DNA of B. glumae 336gr-1; and 3, genomic DNA of B. glumae LSUPB139. M indicates the 1 kb Plus DNA ladder (Invitrogen, Santa Clara, CA, USA) used as a marker. (D) Violacein production, shown as a purple pigment, by the biosensor, Chromobacterium violaceum CV026, in the presence of the culture extracts of the B. glumae strains, 336gr-1, LSUPB145, LSUPB169, and LSUPB139. Photo was taken 48 h after application of bacterial culture extracts on C. violaceum CV026 inoculated onto a LB agar plate. (E) Toxoflavin production, shown as a yellow pigment, in the LB broth by B. glumae strains, 336gr-1, LSUPB145, LSUPB169, and LSUPB139. Photo was taken after 24 h incubation at 37°C.

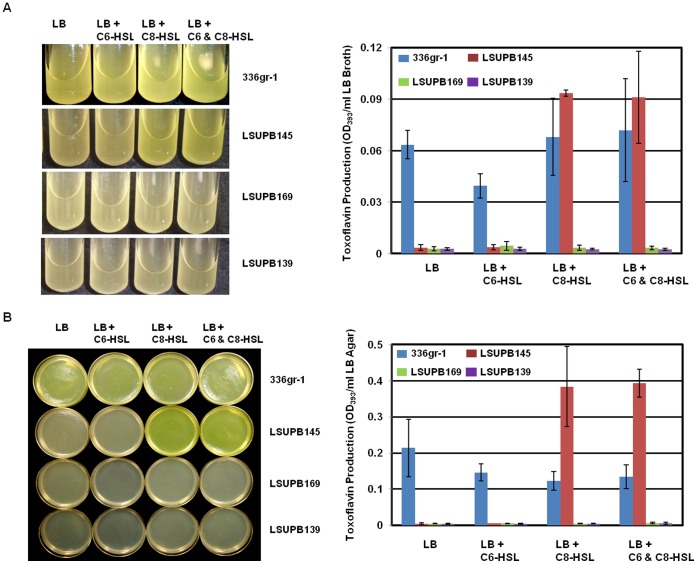

Mutations in tofI and tofR were also confirmed with the biosensor strain, C. violaceum CV026, which produces the purple pigment, violacein, in the presence of AHL compounds, including C6-HSL and C8-HSL [20]. The culture extract of the wild type strain, 336gr-1, caused the production of violacein by the biosensor, while that of the deletion mutants did not (Figure 2D), indicating that these mutants did not produce the AHL molecules required for QS. Likewise, none of the mutants produced toxoflavin in either LB agar or LB broth (Figures 2E and 3). These results were consistent with the previous study by Kim et al. (2004), which showed the dependence of toxoflavin production by B. glumae on tofI and tofR.

Figure 3. Toxoflavin production by Burkholderia glumae strains, 336gr-1 (wild type), LSUPB145 (ΔtofI), LSUPB169 (ΔtofR) and LSUPB139 (ΔtofI-tofR) in the presence or absence of 1.

µM N- hexanoyl homoserine lactone (C6-HSL) and N- octanoyl homoserine lactone (C8-HSL) in LB broth (A) and on LB agar (B). LB broth and LB agar were inoculated with equal amounts of bacterial cells (∼106 CFU) per ml of media. Bacteria were spread uniformly on LB agar plates with a spreader. Photos were taken and toxoflavin were quantified after 24 h incubation at 37°C. LB agar plates were photographed after removal of bacterial culture from the medium. Error bars indicate the standard deviation from three replications.

Restoration of Bacterial Growth and Toxoflavin Production in the Δ tofI Strain, LSUPB145, by C8-HSL

All the QS mutants produced little toxoflavin compared to the wild type in both liquid and solid media (Figure 3). If 1 µM C8-HSL was added to the media, the ΔtofI mutant, LSUPB145, regained the ability to produce toxoflavin, but the ΔtofR mutant, LSUPB169, and the ΔtofI-tofR mutant, LSUPB139, did not (Figure 3). Patterns of toxoflavin production by mutant strains in the presence of exogenous synthetic AHL compounds were similar in both liquid and solid media (Figure 3). In both growth conditions, LSUPB145 appeared to produce more toxoflavin than the wild type 336gr-1 in the presence of 1 µM C8-HSL (Figure 3). According to the statistical analysis using a two-sample t-test, the toxoflavin production in 336gr-1 and LSUPB145 was significantly different from each other in solid media (T value = −3.97, P value = 0.0166) but not in liquid media (T value = −1.95, P value = 0.1888).

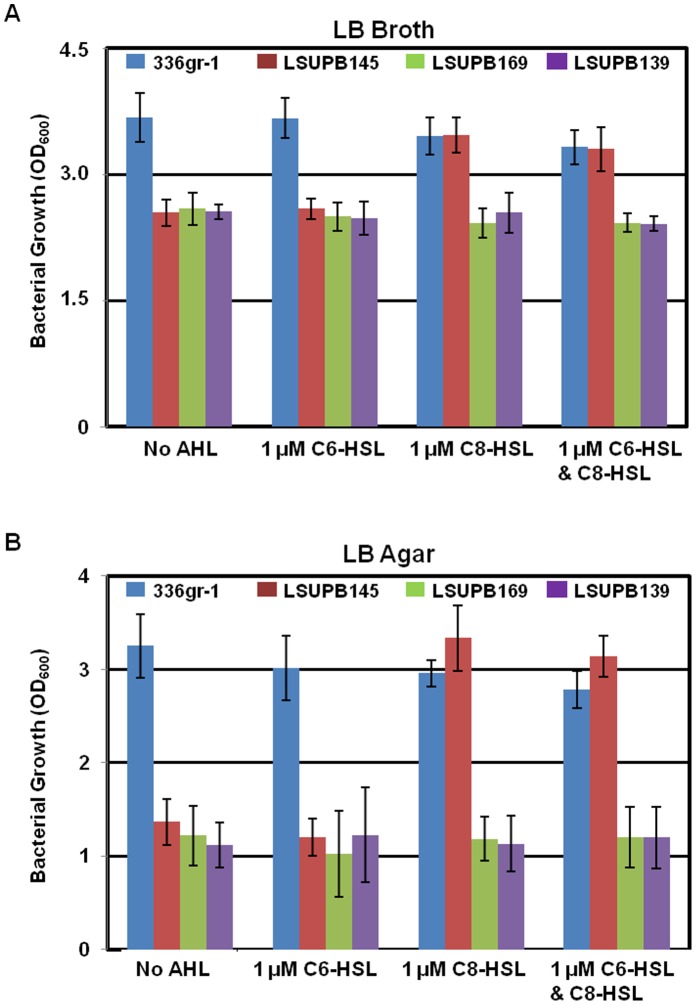

In addition, the QS mutant strains showed reduced growth when compared to the wild type in both liquid and solid media after 24 h incubation at 37°C (Figures 4 and S1). ANOVA and post hoc LSD tests validated that the observed growth reduction of all the three QS mutants in both types of medium condition was statistically significant (not shown). The difference in bacterial growth between the wild type and the QS mutants appeared to be greater in solid media than in liquid media (Figure 4). Addition of C8-HSL to both liquid and solid media restored the growth of the ΔtofI strain, LSUPB145, to the wild type level, but did not have any effect on the growth of the other QS mutants or the wild type strain (Figures 4 and S1). C6-HSL did not affect the growth of any strain tested (Figures 4 and S1).

Figure 4. Bacterial growth of Burkholderia glumae strains, 336gr-1 (wild type), LSUPB145 (ΔtofI), LSUPB169 (ΔtofR) and LSUPB139 (ΔtofI-tofR) in the presence or absence of 1 µM N-hexanoyl homoserine lactone (C6-HSL) and N-octanoyl homoserine lactone (C8-HSL) in LB broth (A) and on LB agar (B).

LB broth and LB agar were inoculated with equal amounts of bacterial cells (∼106 CFU) per ml of media. Absorbance of each bacterial culture was measured after 24 h incubation at 37°C. Error bars indicate the standard deviation from three replications.

Toxoflavin Production of ΔtofI and ΔtofR Derivatives of the Wild Type Strain, 336gr-1, at High Culture Density on LB Agar

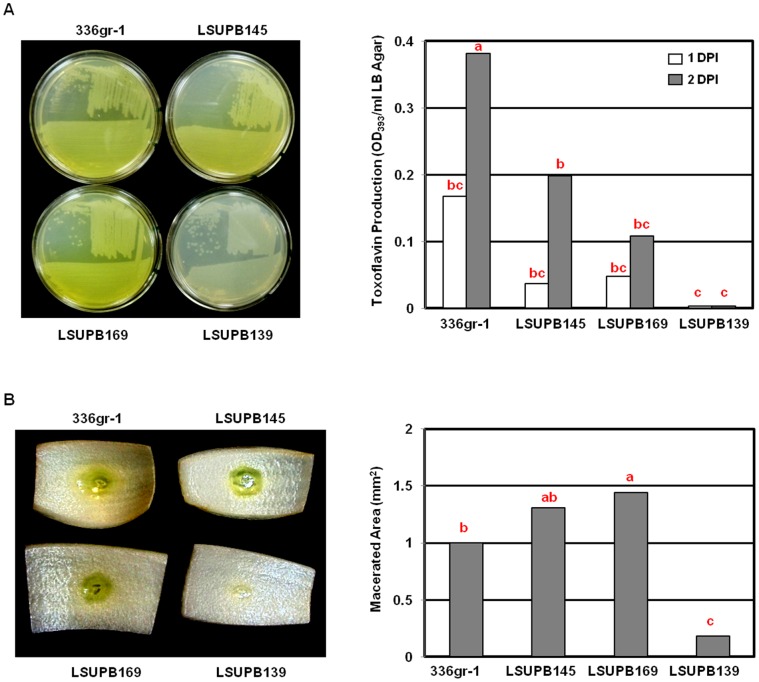

ΔtofI and ΔtofR mutants, LSUPB145 and LSUPB169, respectively, produced toxoflavin when grown on solid media after inoculation with the streaking method using an inoculation loop (Figure 5A). The ΔtofI-tofR strain, LSUPB139, on the other hand, did not produce any detectable toxoflavin in the same condition (Fig. 5A). Even though LSUPB145 and LSUPB169 produced less amounts of toxoflavin than the wild type, 336gr-1, did in this growth condition (Figure 5A), their phenotypes were strikingly different from those shown in LB broth (Figure 3A) or LB agar inoculated with the spreading method (Figure 3B). Similar results were observed in tests with other types of solid media, including King’s B agar [24] (data not shown). In an onion assay established to indirectly determine the virulence of B. glumae [23], LSUPB145 and LSUPB169, but not LSUPB139, were able to cause comparable or larger maceration symptoms on onion bulb scales in comparison with the wild type (Figure 5B). Inoculums prepared from the cultures in LB broth and LB agar showed similar results (data not shown).

Figure 5. Toxoflavin production (A) and virulence phenotypes (B) by Burkholderia glumae strains, 336gr-1 (wild type), LSUPB145 (ΔtofI), LSUPB169 (ΔtofR) and LSUPB139 (ΔtofI-tofR).

(A) LB agar plates inoculated with the streaking method with inoculums from fresh bacterial colonies of B. glumae strains. Photos were taken and quantification procedures were performed 48 h after incubation at 37°C. (B) Virulence phenotypes on onion bulb scales. Photos were taken and maceration was measured 72 h after incubation in a wet chamber at 30°C. Columns for toxoflavin production (A) and area of maceration (B) represent the mean values from three replications and five replications, respectively. The letters above columns indicate significant differences among B. glumae strains (P<0.01). DPI: days post inoculation.

Identification of a New Regulatory Gene, tofM, in the Intergenic Region between tofI and tofR

Based on the observation mentioned above, we speculated that toxoflavin could be produced in a tofI- or tofR-independent manner at certain growth conditions but could not be produced without both tofI and tofR. To verify this notion, a tofI/tofR double deletion mutant (ΔtofI/ΔtofR), LSUPB201, was generated through consecutive deletions of tofI and tofR and its phenotype in toxoflavin production was tested in various conditions. Unlike the ΔtofI-tofR strain LSUPB139, the ΔtofI/ΔtofR mutant LSUPB201 still produced toxoflavin on LB agar medium when it was inoculated with the streaking method (Figures S2 and 6B). The only difference between LSUPB139 (ΔtofI-tofR) and LSUPB201 (ΔtofI/ΔtofR) was the presence of the intergenic region between tofI and tofR (Figure 1), suggesting that unknown genetic element(s) present between tofI and tofR may be responsible for the tofI and tofR-independent production of toxoflavin. According to the annotated whole genome sequence of B. glumae BGR1 (NCBI Reference Sequence: NC_012721.2), the coding sequences of tofI (locus tag: bglu_2g14490) and tofR (locus tag: bglu_2g14470) are 612 bp- and 720 bp-long, respectively, and are separated by a region of DNA 799 bp in length that includes a single ORF (locus tag: bglu_2g14480) that is divergently transcribed from tofR (Figure 1). The deduced amino acid sequence of this ORF showed 22.4% identity to that of RsaM in Pseudomonas fuscovaginae [25] and was found to be highly conserved among Burkhoderia spp. (Table 3 and Figure S3). The DNA sequence of the tofI-tofR intergenic region of B. glumae 336gr-1 was identical to that of B. glumae BGR1.

Table 3. TofM homologs in Burkholderia spp. and Pseudomonas fuscovaginae.

| Locus_tag/Gene | Protein ID (Accession #) | Organism | Identity (similarity) |

| bglu_2g14480 | YP_002909042.1 | Burkholderia glumae BGR1 | 100% |

| bgla_2g11060 | YP_004349067.1 | B. gladioli BSR3 | 80.0% (88.7%) |

| bgla_1p1750 | YP_004362596.1 | B. gladioli BSR3 | 23.7% (35.3%) |

| BCAM1869 | YP_002234480.1 | B. cenocepacia J2315 | 52.9% (59.2%) |

| Bcenmc03_5575 | YP_001779190.1 | B. cenocepacia MC0-3 | 52.2% (59.2%) |

| Bcen_3642 | YP_623507.1 | B. cenocepacia AU 1054 | 52.2% (59.2%) |

| Bmul_3970 | YP_001583945.1 | B. multivorans ATCC 17616 | 55.6% (63.4%) |

| Bamb_4117 | YP_776004.1 | B. ambifaria AMMD | 52.9% (59.9%) |

| BamMC406_4582 | YP_001811254.1 | B. ambifaria MC40-6 | 51.6% (58.6%) |

| BamMC406_5824 | YP_001815818.1 | B. ambifaria MC40-6 | 28.0% (38.5%) |

| Bcep1808_5261 | YP_001117675.1 | B. vietnamiensis G4 | 52.2% (61.1%) |

| Bcep18194_B1051 | YP_371809.1 | Burkholderia sp. 383 | 51.6% (59.9%) |

| BTH_ll1511 | YP_439707.1 | B. thailandensis E264 | 51.3% (65.8%) |

| BURPS668_A1294 | YP_001062291.1 | B. pseudomallei 668 | 50.3% (63.1%) |

| BPSS0886 | YP_110895.1 | B. pseudomallei K96243 | 49.7% (62.4%) |

| BWAA1346 | YP_105962.1 | B. mallei ATCC 23344 | 49.7% (62.4%) |

| rsaM | CBI67624.1/RsaM | Pseudomonas fuscovaginae UPB0736 | 22.4% (37.2%) |

| BURPS1106A_A1576 | YP_001075610.1 | B. pseudomallei 1106a | 32.5% (43.5%) |

| BURPS1106B_0414 | ZP_04810916.1 | B. pseudomallei 1106b | 32.5% (43.5%) |

| BURPS668_A1657 | YP_001062653.1 | B. pseudomallei 668 | 32.5% (43.5%) |

| GBP346_B0905 | EEP50658.1 | B. pseudomallei MSHR346 | 32.5% (43.5%) |

| BPSS1179 | YP_111192.1 | B. pseudomallei K96243 | 28.7% (38.9%) |

| BURPS1710A_A0737 | ZP_04955066.1 | B. pseudomallei 1710a | 17.1% (23.2%) |

| BURPS1710b_A0144 | YP_335303.1 | B. pseudomallei 1710b | 17.1% (23.2%) |

| BTH_II1228 | YP_439424.1 | B. thailandensis E264 | 28.2% (41.2%) |

| Bamb_6054 | YP_777932.1 | B. ambifaria AMMD | 24.2% (33.3%) |

| BamMC406_5825 | YP_001815819.1 | B. ambifaria MC40-6 | 11.5% (20.2%) |

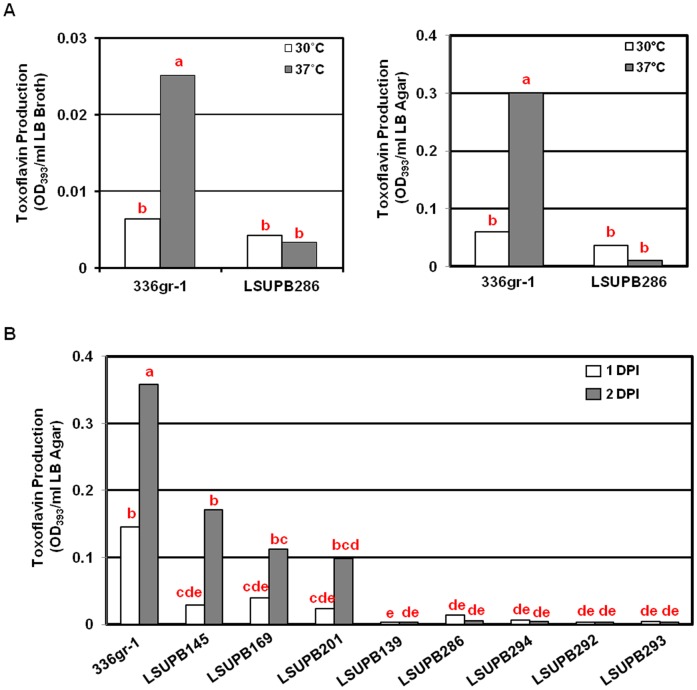

To determine the function of this ORF, deletion mutations of this ORF were made in strains with the genetic backgrounds of ΔtofI and ΔtofR, as well as the wild type background, generating LSUPB201, LSUPB292, and LSUPB286, respectively. The toxoflavin production by LSUPB286 (ΔtofM) was not significantly different from that by the wild type in both LB broth and LB agar conditions at 30°C (Figure 6A). However, this mutant produced a less amount of toxoflavin when compared to the wild type at 37°C and this tendency was more obvious when the bacteria were grown on LB agar medium (Figure 6A). Moreover, the same deletion in the ΔtofI or ΔtofR backgrounds resulted in an almost complete loss of the ability to produce toxoflavin, indicating that this ORF is required for the normal production of toxoflavin (Figure 6B). Thus, this ORF was considered as a functional gene and named as tofM, after rsaM due to the sequence homology and similarity in genetic location between luxI and luxR homolgs [25] (Figure S3).

Figure 6. Toxoflavin production of Burkholderia glumae tofM deletion mutants in various genetic backgrounds.

(A) Toxoflavin production by 336gr-1 (wild type) and LSUPB286 (ΔtofM) in LB broth (left) and on LB agar (right). Equal amounts of bacterial cells (∼106 CFU/ml medium) were inoculated in both LB broth and LB agar media. For inoculation on LB agar plates, bacterial suspensions were uniformly spread with a spreader. Toxoflavin production was determined 24 h after incubation at 30°C or 37°C. (B) Toxoflavin production on LB agar plated by B. glumae strains, 336gr-1 (wild type), LSUPB145 (ΔtofI), LSUPB169 (ΔtofR), LSUPB201 (ΔtofI/ΔtofR), LSUPB139 (ΔtofI-tofR), LSUPB286 (ΔtofM), LSUPB294 (ΔtofI/ΔtofM), LSUPB292 (ΔtofR/ΔtofM) and LSUPB293 (ΔtofI/ΔtofM/ΔtofR). Bacteria were inoculated with the streaking method from fresh bacterial colonies. Toxoflavin production was determined 24 and 48 h after incubation at 37°C. Each column for A indicates a mean values from three replications, while that for B represents a mean value from six replications conducted in two independent experiments. The letters above columns indicate significant differences among B. glumae strains (P<0.01).

Complementation with the tofM clone, pBBtofM, restored toxoflavin production by the ΔtofM strain, LSUPB286 (Figures S4B, S4C, and S5). However, complementation with this tofM clone did not restore the production of toxoflavin on LB agar by LSUPB294 (ΔtofI/ΔtofM), LSUPB292 (ΔtofR/ΔtofM), LSUPB293 (ΔtofI/ΔtofM/ΔtofR), or LSUPB139 (ΔtofI-tofR) (Figure S5). Complementation with pBBtofRM, which contains tofR and tofM, restored the toxoflavin-deficient phenotype of the ΔtofR/ΔtofM strain, LSUPB292, but did not restore the tofI-independent production of toxoflavin in LSUPB293 (ΔtofI/ΔtofM/ΔtofR) and LSUPB139 (ΔtofI-tofR) (Figure S5). Complementation with pBBtofIM, which contains tofI and tofM, did not restore the production of toxoflavin in the ΔtofI/ΔtofM mutant, LSUPB294 (Figure S5). Furthermore, complementation with pBBtofIMR, which contains tofI, tofM and tofR, restored the production of toxoflavin in LSUPB293 (ΔtofI/ΔtofM/ΔtofR), LSUPB139 (ΔtofI-tofR) and LSUPB201 (ΔtofI/tofR), but did not restore the production of toxoflavin in LSUPB286 (ΔtofM), LSUPB292 (ΔtofR/ΔtofM), or LSUPB294 (ΔtofI/ΔtofM) (Figures S4A and S5).

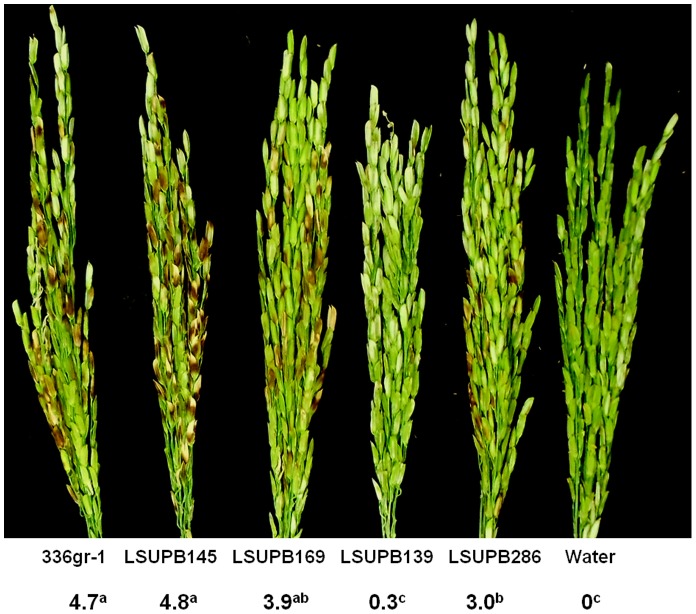

Virulence Phenotypes of tofI, tofR, and tofM Mutants in Rice Plants

In a greenhouse test, the abilities of LSUPB145 (ΔtofI) and LSUPB169 (ΔtofR) to cause symptoms in rice panicles were comparable to that of the wild type, 336gr-1 (Figure 7). However, the ΔtofM mutant LSUPB286 was significantly less virulent than the wild type and tofI or tofR mutants (Figure 7). In this test, LSUPB139 (ΔtofI-tofR) caused few visible symptoms, indicating that tofI, tofR and tofM are collectively required for the pathogenicity of B. glumae in rice (Figure 7).

Figure 7. The virulence of Burkholderia glumae strains in rice.

The numbers indicate the disease severities caused by each strain of B. glumae or water. Disease severity was determined with a 0–9 scale (0 - no symptom, 9– more than 80% discolored panicles) at 10 days after bacterial inoculation and each number indicates a mean value from at least five replications. The superscript letters of the disease severity values indicate significant differences among B. glumae strains (P<0.01).

Discussion

The QS system mediated by the TofI AHL synthase and the TofR AHL receptor is known to be a central regulatory element that governs the expression of the major virulence factors of B. glumae, including toxoflavin [4], [8], lipase [7], and flagella [8]. In this study, a series of tofI, tofM and tofR mutants were generated to dissect the function of each of these QS components in the production of toxoflavin in B. glumae. LSUPB145 (ΔtofI) and LSUPB169 (ΔtofR) produced significantly reduced amounts of toxoflavin compared with the wild type strain, 336gr-1 (Figures 2, 3, and S4A). In addition, the ability of LSUPB145 to produce toxoflavin was restored by the addition of 1 µM C8-HSL, but not C6-HSL (Figure 3). These results were consistent with previous studies with another B. glumae strain, BGR1, which demonstrated the dependency of toxoflavin production on the TofI/TofR QS system and C8-HSL [4], [8]. Although TofI synthesizes both C6-HSL and C8-HSL as major products [4], the role of C6-HSL is still unknown. Notably, the tofI deletion mutant, LSUPB145, produced higher amounts of toxoflavin compared to the parental strain, 336gr-1, in the presence of 1 µM C8-HSL (Figure 3). This pattern was more obvious in LB agar than in LB broth (Figure 3B). This result strongly suggests that tofI is involved in an unknown activity that suppresses the function of C8-HSL in toxoflavin production.

Intriguingly, even though AHL signals were not produced by either the ΔtofI or the ΔtofR mutant (data not shown), both mutants were able to produce high levels of toxoflavin when inoculated with the streaking method on the LB (Figure 5) or KB agar media (data not shown). Further, LSUPB201, which has deletions of both tofI and tofR, also produced considerable amounts of toxoflavin on solid media (Figures 6 and S2). The tofI, tofR and tofI/tofR mutants generated via different approaches, including transposon mutagenesis and homologous recombination, produced phenotypes similar to those of the ΔtofI, ΔtofR, and ΔtofI/ΔtofR strains, indicating that the observed toxoflavin production by tofI, tofR, and tofI/tofR mutants is not an artifact (data not shown). Additionally, significant growth defects observed with the QS mutants suggest that the TofI/TofR QS system controls the bacterial genes required for optimal bacterial growth.

We speculated that the deviated phenotypes of LSUPB145 (ΔtofI) and LSUPB169 (ΔtofR) in toxoflavin production on solid media dependent on different methods of inoculation might be due to the differences in bacterial concentration of the initial inoculum. To test this hypothesis, an overnight culture (∼109 CFU/ml) of LSUPB145 grown in LB broth was inoculated on LB agar with the streaking method, while a concentrated bacterial suspension (∼1011 CFU/ml) of the same strain was inoculated on LB agar with the spreading method. When an overnight culture (∼109 CFU/ml) of LSUPB145 was inoculated on LB agar plates with the streaking method, the bacterial cultures frequently failed to produce toxoflavin but occasionally (with about 30% chance) produced toxoflavin (data not shown). In contrast, when a concentrated bacterial suspension (∼1011 CFU/ml) was inoculated on LB agar plates with the spreading method, the bacterial cultures frequently produced toxoflavin but occasionally (with about 30% chance) failed to produce toxoflavin (data not shown). In both inoculation conditions, the chance to produce toxoflavin increased as the bacterial concentration of the initial inoculum was higher (data not shown). These observations suggest that both initial concentration of bacterial inoculum and method of bacterial inoculation are critical factors for the tofI- or tofR-independent production of toxoflavin on solid media.

Based on the observed toxoflavin production by the tofI, tofR and tofI/tofR mutants at certain growth conditions, we speculated that B. glumae possesses alternative regulatory pathway(s) for the production of toxoflavin in the absence of TofI and TofR. Because the ΔtofI-tofR mutant, LSUPB139, did not produce toxoflavin in any growth condition tested (Figures 2, 3, 5, S2, and S4A), the intergenic region between tofI and tofR was thought to contain at least one regulatory gene that is responsible for toxoflavin production and independent of tofI and tofR. Indeed, a putative gene divergently transcribed from tofR was found to be involved in the production of toxoflavin and deletion of tofM in the wild type background caused a significant reduction in toxoflavin production and virulence in rice (Figures 6A and 7). Toxoflavin production of the ΔtofM strain, LSUPB286, was restored to wild type levels following complementation with the tofM clone, pBBtofM (Figures S4B, S4C, and S5). Nevertheless, complementation of the mutants with functional clones of the mutated genes was frequently unsuccessful (Figure S5), implying that the accurate balance of gene expression based on the correct genomic position and gene dosage of tofI, tofM and tofR is critical for the regulation of toxoflavin production by these genes. In this regard, it is noteworthy that the ΔtofM mutant was complemented by a tofM clone carrying tofM only (pBBtofM), but not by tofM clones carrying additional genes (pBBtofRM, pBBtofIM and pBBtofIMR); likewise, the ΔtofRM and ΔtofIMR mutants were complemented only by pBBtofRM and pBBtofIMR, respectively (Figure S5). We do not know why the ΔtofIM mutant could not be complemented by any clones carrying both tofI and tofM, including pBBtofIM (Figure S5).

Taken together, these results indicate that tofM is a positive regulator for toxoflavin production. When B. glumae is grown in liquid media or on solid media after inoculation with the spreading method, TofM may supplement the regulatory function of the TofI/TofR QS in the production of toxoflavin. When B. glumae is grown on solid media after inoculation with the streaking method, however, TofM may cause the TofI/TofR QS-independent production of toxoflavin. Even though TofM is likely a key regulatory component of the tofI- and tofR-independent pathway(s) for toxoflavin production, additional regulatory components required for the production of toxoflavin in the absence of tofI or tofR have been identified and are currently being analyzed (Chen and Ham, unpublished).

Even though tofM was identified as a positive regulator for toxoflavin production in this study, its homolog, rsaM, was first reported as a novel negative regulator for the QS systems of another rice pathogenic bacterium, P. fuscovaginae [25]. Nevertheless, rsaM seems to exert positive functions for virulence as well because an rsaM mutant of P. fuscovaginae showed attenuated virulence in rice [25]. Both tofM and rsaM are present in the intergenic region of luxI and luxR homologs and are oriented divergently from the luxR homologs (Figure S3). Recent studies on Pseudomonas spp. including P. aeruginosa, P. putida, and P. fuscovaginae revealed that rsaL and rsaM, present in the intergenic regions of luxI and luxR homologs, act as negative regulators controlling the homeostasis of AHL levels [26]. In this study, positive function of tofM in virulence was observed (Figure 7), however, repressive action of tofM on the AHL-mediated QS was somewhat ambiguous in the AHL-detection assay using the biosensor C. violaceum CV026 (Figure S6). The biosensor strain treated with the culture filtrate of the tofM mutant, LSUPB286, showed a stronger purple color than that treated with the culture filtrate of the wild type, 336gr-1 (Figure S6). However, this phenotype of LSUPB286 suggesting a negative role of tofM in the AHL-mediated QS could not be complemented by the tofM clone, pBBtofM. Quantitative analyses to precisely determine the roles of tofM in the expression of tofI and tofR, as well as other virulence genes, of B. glumae and in the production of AHL compounds are currently being conducted (Chen and Ham, unpublished).

A database search for tofM revealed that tofM homologs are conserved in many Burkholderia spp. (Table 3 and Figure S3), suggesting the importance of their functions for ecological fitness. B. gladioli, which also causes BPB of rice, possesses two tofM homologs along with two sets of luxI and luxR homologs. Between the two predicted proteins encoded by the tofM homologs of B. gladioli, one shows the highest level of homology (80% amino acid sequence identity) to TofM, while the other shows only 23.7% identity (Table 3). It is noteworthy that, among the tofM homologs investigated in this study, all of the homologs with greater than 49% identity in deduced amino acid sequence to tofM had the same position and orientation patterns as tofM and rsaM relative to their neighboring luxI and luxR homologs (Table 3 and Figure S3). Regarding the conserved genetic locations and amino acid sequences of encoded proteins, it is very probable that the tofM homologs of other Burkholderia spp., including the select agents, B. mallei and B. pseudomallei, execute similar functions to tofM. Thus, elucidation of the tofM function in the TofI/TofR QS system of B. glumae would provide useful insights into the counter parts of human and animal pathogenic Burkholderia spp.

Conclusively, tofI- and tofR-independent production of toxoflavin in B. glumae was revealed for the first time in this study and tofM was identified as a key genetic component of this newly found pathway for toxoflavin production. tofM alone was also found to contribute to the full virulence of B. glumae 336gr-1. Further studies to determine the regulatory functions of tofM in the expression of tofI and tofR as well as other virulence genes of B. glumae would lead to a better understanding of the global regulatory system that governs the expression of virulence genes in this pathogen and, possibly, other related bacterial species.

Supporting Information

Growth curves of B. glumae strains, 336gr-1 (wild type), LSUPB145 ( ΔtofI ), and LSUPB169 ( ΔtofR ) grown in LB broth (top left), LB broth amended with 1 µM N- hexanoyl homoserine lactone (C6-HSL)(top right), and LB broth amended with or N- octanoyl homoserine lactone (C8-HSL)(bottom). Bacteria were grown at 37°C in a shaking incubator at ∼200 rpm. Similar patterns of data were obtained from three independent experiments.

(TIF)

Toxoflavin production by B. glumae strains, LSUPB145 ( ΔtofI ), LSUPB201 ( ΔtofI/ΔtofR ), LSUPB294 ( ΔtofI/ΔtofM ) and LSUPB139 ( ΔtofI-tofR ) on LB agar plates. Bacteria were inoculated on LB agar plates with the streaking method from fresh colonies of B. glumae strains. Toxoflavin production is indicated by the presence of the yellow pigment in the media. Photo was taken after 24 h incubation at 37°C.

(TIF)

A phylogenetic tree of the RsaM homologs found from the genome sequences of Burkholderia spp. and the relative positions and transcriptional directions of the rsaM homologs. The accession number of TofM is indicated with a red box. Red, green, and orange arrows indicate the homologs of luxR, rsaM, and luxI, respectively. Arrow direction indicates the transcriptional direction of depicted genes; arrow size is not proportional to the size of the corresponding genes. The phylogenetic tree was conducted with MEGA5 [27] using the UPGMA method based on the amino acid sequences of the 27 RsaM homologs including TofM. Bootstrap values from 1000 replicates were given next to the branches. The numbers indicating the evolutionary distance at the bottom of the tree represent the number of amino acid substitutions per site.

(TIF)

Toxoflavin production of Burkholderia glumae mutants and mutants complemented with functional clones of the mutated genes. (A)Toxoflavin production of 336gr-1 (wild type), LSUPB145 (ΔtofI), LSUPB169 (ΔtofR), LSUPB139 (ΔtofI-tofR) and LSUPB139 with pBBtofIMR. (B and C) Toxoflavin production of 336gr-1 (wild type), LSUPB286 (ΔtofM) and LSUPB286 with pBBtofM in LB broth (B) and LB agar (C). Photos were taken at 24 h after incubation at 37°C.

(TIF)

A schematic diagram summarizing the complementation tests conducted in this study. The area deleted in each gene(s) is indicated in a lighter version of the color of the gene. *Toxoflavin production by bacteria inoculated with the streaking method.

(TIF)

AHL production by B. glumae strains, 336gr-1 (wild type), LSUPB145 ( ΔtofI ), LSUPB286 ( ΔtofM ), and LSUPB286 complemented with pBBtofM. AHL production by each strain of B. glumae is indicated by the production of violacein by the biosensor, Chromobacterium violaceum CV026. Photo was taken 48 h after application of B. glumae culture extracts on the biosensor and incubation at 30°C.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Rebecca A. Melanson and Bishnu Shrestha for critical review of this manuscript.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Louisiana State University Agricultural Center, the Research and Development Program of the Louisiana Board of Regents Support Fund (Grant number: LEQSF(2008-11)-RD-A-02), and the Pilot Funding for New Research (Pfund) Program of the National Science Foundation and the Louisiana Board of Regents (Grant number: NSF(2010)-PFUND-194). RC was supported by the Economic Development Assistantship of the Louisiana Board of Regents. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Ham JH, Melanson RA, Rush MC (2011) Burkholderia glumae: next major pathogen of rice? Mol Plant Pathol 12: 329–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nandakumar R, Shahjahan AKM, Yuan XL, Dickstein ER, Groth DE, et al. (2009) Burkholderia glumae and B. gladioli cause bacterial panicle blight in rice in the southern United States. Plant Dis 93: 896–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Iiyama K, Furuya N, Takanami Y, Matsuyama N (1995) A role of phytotoxin in virulence of Pseudomonas glumae . Ann Phytopathol Soc Jpn 61: 470–476. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kim J, Kim JG, Kang Y, Jang JY, Jog GJ, et al. (2004) Quorum sensing and the LysR-type transcriptional activator ToxR regulate toxoflavin biosynthesis and transport in Burkholderia glumae . Mol Microbiol 54: 921–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nagamatsu T (2002) Syntheses, transformation, and biological activities of 7-azapteridine antibiotics: Toxoflavin, fervenulin, reumycin and their analogues. Chem Inform 33: 261. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Suzuki F, Sawada HA, Zegami K, Tsuchiya K (2004) Molecular characterization of the tox operon involved in toxoflavin biosynthesis of Burkholderia glumae . J Gen Plant Pathol 70: 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Devescovi G, Bigirimana J, Degrassi G, Cabrio L, LiPuma JJ, et al. (2007) Involvement of a quorum-sensing-regulated lipase secreted by a clinical isolate of Burkholderia glumae in severe disease symptoms in rice. Appl Environ Microbiol 73: 4950–4958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kim J, Kang Y, Choi O, Jeong Y, Jeong JE, et al. (2007) Regulation of polar flagellum genes is mediated by quorum sensing and FlhDC in Burkholderia glumae . Mol Microbiol 64: 165–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fuqua C, Parsek MR, Greenberg EP (2001) Regulation of gene expression by cell-to-cell communication: acyl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing. Annu Rev Genet 35: 439–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Miller MB, Bassler BL (2001) Quorum sensing in bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol 55: 165–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eberhard A (1972) Inhibition and activation of bacterial luciferase synthesis. J Bacteriol 109: 1101–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fuqua WC, Winans SC, Greenberg EP (1994) Quorum sensing in bacteria: the LuxR-LuxI family of cell density-responsive transcriptional regulators. J Bacteriol 176: 269–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dunlap PV (1999) Quorum regulation of luminescence in Vibrio fischeri . J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 1: 5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sambrook J (2001) Molecular cloning: A laboratory manual, 3rd Ed: Cold Spring Harbor Press.

- 15. Bertani G (2004) Lysogeny at mid-twentieth century: P1, P2, and other experimental systems. J Bacteriol 186: 595–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ditta G, Stanfield S, Corbin D, Helinski DR (1980) Broad host range DNA cloning system for gram-negative bacteria: construction of a gene bank of Rhizobium meliloti . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 77: 7347–7351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Figurski DH, Helinski DR (1979) Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 76: 1648–1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karki HS, Barphagha IK, Ham JH (2012) A conserved two-component regulatory system, PidS/PidR, globally regulates pigmentation and virulence-related phenotypes of Burkholderia glumae. Mol Plant Pathol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19. Metcalf WW, Jiang W, Daniels LL, Kim SK, Haldimann A, et al. (1996) Conditionally replicative and conjugative plasmids carrying lacZ alpha for cloning, mutagenesis, and allele replacement in bacteria. Plasmid 35: 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McClean KH, Winson MK, Fish L, Taylor A, Chhabra SR, et al. (1997) Quorum sensing and Chromobacterium violaceum: exploitation of violacein production and inhibition for the detection of N-acylhomoserine lactones. Microbiology 143 (Pt 12): 3703–3711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jung WS, Lee J, Kim MI, Ma J, Nagamatsu T, et al. (2011) Structural and functional analysis of phytotoxin toxoflavin-degrading enzyme. PLoS One 6: e22443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jacobs JL, Fasi AC, Ramette A, Smith JJ, Hammerschmidt R, et al. (2008) Identification and onion pathogenicity of Burkholderia cepacia complex isolates from the onion rhizosphere and onion field soil. Appl Environ Microbiol 74: 3121–3129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Karki HS, Shrestha BK, Han JW, Groth DE, Barphagha IK, et al. (2012) Diversities in virulence, antifungal activity, pigmentation and DNA fingerprint among strains of Burkholderia glumae . PLoS ONE 7: e45376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schaad NW, Jones JB, Chun W (2001) Laboratory guide for identification of plant pathogenic bacteria. 3rd Ed.: The American Society of Phytopathological Society Press.

- 25. Mattiuzzo M, Bertani I, Ferluga S, Cabrio L, Bigirimana J, et al. (2011) The plant pathogen Pseudomonas fuscovaginae contains two conserved quorum sensing systems involved in virulence and negatively regulated by RsaL and the novel regulator RsaM. Environ Microbiol 13: 145–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Venturi V, Rampioni G, Pongor S, Leoni L (2011) The virtue of temperance: built-in negative regulators of quorum sensing in Pseudomonas . Mol Microbiol 82: 1060–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, et al. (2011) MEGA5: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Molecular Biology and Evolution 28: 2731–2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Grant SG, Jessee J, Bloom FR, Hanahan D (1990) Differential plasmid rescue from transgenic mouse DNAs into Escherichia coli methylation-restriction mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 87: 4645–4649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Simon R, Priefer U, Puhler A (1983) A broad host range mobilization systemfor in vitro genetic engineering: Transposition mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. Biotechnology 1: 784–791. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kovach ME, Elzer PH, Hill DS, Robertson GT, Farris MA, et al. (1995) Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166: 175–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Penfold RJ, Pemberton JM (1992) An improved suicide vector for construction of chromosomal insertion mutations in bacteria. Gene 118: 145–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Alexeyev MF (1999) The pKNOCK series of broad-host-range mobilizable suicide vectors for gene knockout and targeted DNA insertion into the chromosome of gram-negative bacteria. Biotechniques 26: 824–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Growth curves of B. glumae strains, 336gr-1 (wild type), LSUPB145 ( ΔtofI ), and LSUPB169 ( ΔtofR ) grown in LB broth (top left), LB broth amended with 1 µM N- hexanoyl homoserine lactone (C6-HSL)(top right), and LB broth amended with or N- octanoyl homoserine lactone (C8-HSL)(bottom). Bacteria were grown at 37°C in a shaking incubator at ∼200 rpm. Similar patterns of data were obtained from three independent experiments.

(TIF)

Toxoflavin production by B. glumae strains, LSUPB145 ( ΔtofI ), LSUPB201 ( ΔtofI/ΔtofR ), LSUPB294 ( ΔtofI/ΔtofM ) and LSUPB139 ( ΔtofI-tofR ) on LB agar plates. Bacteria were inoculated on LB agar plates with the streaking method from fresh colonies of B. glumae strains. Toxoflavin production is indicated by the presence of the yellow pigment in the media. Photo was taken after 24 h incubation at 37°C.

(TIF)

A phylogenetic tree of the RsaM homologs found from the genome sequences of Burkholderia spp. and the relative positions and transcriptional directions of the rsaM homologs. The accession number of TofM is indicated with a red box. Red, green, and orange arrows indicate the homologs of luxR, rsaM, and luxI, respectively. Arrow direction indicates the transcriptional direction of depicted genes; arrow size is not proportional to the size of the corresponding genes. The phylogenetic tree was conducted with MEGA5 [27] using the UPGMA method based on the amino acid sequences of the 27 RsaM homologs including TofM. Bootstrap values from 1000 replicates were given next to the branches. The numbers indicating the evolutionary distance at the bottom of the tree represent the number of amino acid substitutions per site.

(TIF)

Toxoflavin production of Burkholderia glumae mutants and mutants complemented with functional clones of the mutated genes. (A)Toxoflavin production of 336gr-1 (wild type), LSUPB145 (ΔtofI), LSUPB169 (ΔtofR), LSUPB139 (ΔtofI-tofR) and LSUPB139 with pBBtofIMR. (B and C) Toxoflavin production of 336gr-1 (wild type), LSUPB286 (ΔtofM) and LSUPB286 with pBBtofM in LB broth (B) and LB agar (C). Photos were taken at 24 h after incubation at 37°C.

(TIF)

A schematic diagram summarizing the complementation tests conducted in this study. The area deleted in each gene(s) is indicated in a lighter version of the color of the gene. *Toxoflavin production by bacteria inoculated with the streaking method.

(TIF)

AHL production by B. glumae strains, 336gr-1 (wild type), LSUPB145 ( ΔtofI ), LSUPB286 ( ΔtofM ), and LSUPB286 complemented with pBBtofM. AHL production by each strain of B. glumae is indicated by the production of violacein by the biosensor, Chromobacterium violaceum CV026. Photo was taken 48 h after application of B. glumae culture extracts on the biosensor and incubation at 30°C.

(TIF)