Abstract

Background

Evidence indicates that being a victim of bullying or peer aggression has negative short- and long-term consequences. In this study, we investigated the mediating and moderating role of two types of attributional mechanisms (hostile and self-blaming attributions) on children’s maladjustment (externalizing and internalizing problems).

Methods

In total, 478 children participated in this longitudinal study from grade 5 to grade 7. Children, parents and teachers repeatedly completed questionnaires. Peer victimization was assessed through peer reports (T1). Attributions were assessed through self-reports using hypothetical scenarios (T2). Parents and teachers reported on children’s maladjustment (T1 and T3).

Results

Peer victimization predicted increases in externalizing and internalizing problems. Hostile attributions partially mediated the impact of victimization on increases in externalizing problems. Self-blame was not associated with peer victimization. However, for children with higher levels of self-blaming attributions, peer victimization was linked more strongly with increases in internalizing problems.

Conclusions

Results imply that hostile attributions may operate as a potential mechanism through which negative experiences with peers lead to increases in children’s aggressive and delinquent behavior, whereas self-blame exacerbates victimization’s effects on internalizing problems.

Keywords: Peer victimization, Hostile attributions, Self-blame, Internalizing problems, Externalizing Problems

A wealth of studies shows victims of bullying or peer aggression are likely to suffer negative short- and long-term consequences. Peer victimization is strongly associated with externalizing problems, and may constitute both a cause and a consequence of externalizing problems such as aggression (see Reijntjes et al., 2011). Evidence from longitudinal and twin studies suggests that peer victimization plays a causal role in the development of children’s depressive symptoms (Arseneault et al., 2008; Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie, & Telch, 2010). As outlined by Graham and Juvonen (2001) attributional processes might be particularly relevant to understand the impact of victimization on children’s responses to victimization and subsequent maladjustment. According to this framework - which draws on attribution theory that is concerned with the perceived causes of events (Weiner, 1985) - the question “who is to blame”, seems to be of particular importance. Attributional processes (e.g., self-blame or peer blame, such as attributing hostile intentions to peers) may serve as potential mediators or moderators of victimization’s effects on maladjustment. The mediating pathways indicate that peer victimization has an impact on children’s attributions that in turn have an impact on their maladjustment; that is, attributions – among other factors - might explain whether children develop externalizing or internalizing symptoms as consequences of peer victimization. The moderation effect would suggest that children’s attributions exacerbate or buffer the impact of peer victimization on maladjustment. In this study, we investigated the role of both processes (i.e., mediation and moderation) on two types of attributional mechanisms (hostile and self-blaming attributions) on children’s externalizing and internalizing symptoms.

Attributions and children’s maladjustment

In addition to attribution theory (Graham & Juvonen, 2001; Weiner, 1985), social information processing theory also discusses the role of attributional mechanisms. The social information processing model (Crick & Dodge, 1994; Lemerise & Arsenio, 2000) explicates cognitive mechanisms children may utilize when coping with peer victimization. One of the six processing steps concerns children’s interpretation of cues - which is equivalent to attribution processes. This step is considered to be fundamental because such interpretations are hypothesized to affect the behaviors children construct in response to peer provocations, and such actions may impact their (mal)adjustment. Concerning psychological (mal)adjustment, mainly two kinds of attribution styles have been investigated: the hostile attribution bias (i.e., external blame toward peers) and the depressogenic attributional style (i.e., self-blame).

Hostile attributions and externalizing problems

The hostile attribution bias, which is a form of external blame, depicts a tendency to attribute a hostile intent to another person even in ambiguous and neutral situations. This phenomenon is known to be linked with externalizing symptoms. As Dodge (2006) has suggested, a hostile environment (e.g., peer victimization) may lead to increases (or rather a lack of decreases) in hostile attributions which in turn predict aggressive behavior. Thus, hostile attributions can be conceived as a mediating factor between peer victimization and externalizing problems.

In fact, it was found that peer victimization is positively associated with higher levels of hostile attributions (Camodeca & Goossens, 2005; Pornari & Wood, 2010), especially in peer provocation situations (Keil & Price, 2009). The mediating role of hostile attributions between victimization and aggressive behavior has been documented in a cross-sectional study (Hoglund & Leadbeater, 2007). Likewise, Yeung and Leadbeater (2007) found that hostile attributions mediated the association between relational victimization and relational aggression cross-sectionally, but not longitudinally. Findings from a recent three-wave longitudinal study by Calvete and Orue (2011) showed that the impact of exposure to violence in different contexts (witnessing and victimization) on later reactive aggressive behavior is partially mediated by hostile attributions.

Although most researchers have investigated the mediational role of hostile attributions, it is also possible that hostile attributions moderate (i.e., exacerbate) certain associations. A study by Mathieson (2011) showed hostile attributions were only associated with relational aggression if girls reported higher levels of relational victimization and emotional sensitivity.

Self-blaming attributions and internalizing problems

Self-blaming attributions, including depressogenic and characterological self-blame attributions, have been studied primarily in relation to internalizing problems. Here, the “learned helplessness” framework has been applied as a means of understanding how attributions are linked with problems such as depression (Graham & Juvonen, 1998; Lewis & Waschbusch, 2008; Seligman et al., 1984). It is assumed that individual’s attribution styles develop during childhood (Cole et al., 2008), and that persons develop preferences for certain combinations of the four dimensions and utilize them consistently (i.e., cross-situational consistency; global attribution style). A depressogenic attributional style (which includes self-blame for negative events) has been examined in both cross sectional and longitudinal studies and found to be a correlate of depressive symptoms (for review see Abramson et al., 2002). Because most of these findings come from studies of adults and older adolescents, it is remains unclear whether this type of attributional style plays a moderating or a mediating role in the relation between victimization and depressive symptoms in children and younger adolescents. It has been hypothesized, however, that such links exist (Cole et al., 2008; Gibb & Alloy, 2006).

A few investigators have examined the specific links between peer victimization, attributions and internalizing problems. Results showed that peer victimization is associated with elevated levels of characterological self-blame (i.e., with the tendency to attribute victimization experiences to internal, stable and uncontrollable causes; see Graham & Juvonen, 1998). Singh and Bussey (2011) found that a lack of self-efficacy to avoid self-blame emerged as a mediator between peer victimization and depression. In a study by Graham and colleagues (2009), the meditational pathway of self-blame was also confirmed among students of the ethnic majority (but not among minority youth). In contrast, Catterson and Hunter (2009) found that attributions of blame did not mediate associations between victimization and loneliness. However, in the latter study, self- and other-blame were combined into one bipolar scale.

A study by Gibb and Alloy (2006) showed that a depressogenic attribution style partially mediated the impact of victimization experiences on increases in depressive symptoms over two years. However, these investigators also found that self-blaming attributions aggravated (i.e., moderated) the impact of peer victimization (Gibb & Alloy, 2006). Likewise, critical self-referent attributions were particularly strongly associated with emotional symptoms when combined with high levels of youth’s actual experience of peer victimization (Prinstein, Cheah, & Guyer, 2005).

Research questions

In this study we investigate the predictive role of the two types of attributional mechanisms (hostile and self-blaming attributions) on children’s maladjustment. We aim to expand existing empirical knowledge through the simultaneous investigation of the role of hostile and self-blaming attributions and by examining both mediating and moderating mechanisms. For both types of attributions, we adopt the traditional social information processing approach, that is, we assess children’s attributions in relation to ambiguous situations (which is in contrast to the general attribution theory approach). We hypothesized that hostile attributions are a mediator between peer victimization and externalizing problems, whereas self-blaming attributions mediate the impact of peer victimization on internalizing problems. To test our mediational hypothesis, we measured the mediator (attributions) as an intervening variable, that is, after the predictor (victimization) but before the outcome (maladjustment). Regarding the outcome we controlled for the initial level of maladjustment, thus predicting changes in externalizing and internalizing problems over time. In addition to the mediational model, we tested whether children’s attributions moderate (i.e., buffer or exacerbate) the impact of peer victimization on maladjustment. Gender was controlled because we expect gender differences in internalizing and externalizing problems.

The simultaneous consideration of two types of attributions and maladjustment patterns related to victimization will advance our understanding of potential causal pathways and differential consequences of negative peer experiences. This study will thus provide a further step towards an integrative framework to understand the impact of peer victimization on children’s development.

Method

Procedure

Data for this study were gathered as part of a larger longitudinal project (Pathways Project, Ladd, 2005) conducted in the Midwestern United States. In this study, data from children, their classmates, teachers and parents were used when participating children were in grades 5 to 7. Consent was first obtained from school administrators of participating school districts. In Grade 5, there were 166 classrooms within 95 schools participating in the study. Written parental consent and children’s assent was obtained for each participant. Of the families invited to participate in the study, ninety-five percent agreed.

Participants

The sample for this study consisted of 478 children (49.8% female) that had an average age of 10.59 years (SD = 0.40) in fifth grade. The sample contained nearly equal proportions of families from urban, suburban, or rural Midwestern communities, and its socioeconomic and ethnic composition was representative of the locales from which it was drawn. Total family income: 19% lower to middle ($0-$20,000); 25.3% middle ($20,001-$40,000); and 55.7% upper-middle to high (above $40,001). Ethnicity: Caucasian: 80.1%; African-American: 15.7%; Hispanic, mixed race, or other: 4.2%.

Assessment of peer victimization (T1: spring grade 5)

Peer victimization was assessed through peer reports (Ladd & Kochenderfer-Ladd, 2002). Children were asked to nominate (up to) three classmates who could be described by the following criteria: “Someone who gets teased, called names, or made fun of by other children”, “gets hit, pushed or kicked”, “kids say bad things about him/her to other kids”, and “gets picked on”. Scores were created by standardizing the number of nominations children received for each item, by classroom (α =.94)

Assessment of attributions (T2: Fall and spring grade 6)

Attributions were assessed through hypothetical scenarios (Dell Fitzgerald & Asher, 1987) in fall and spring of grade 6. Students responded to 4 scenarios1 in each assessment (spilling paint on a project; getting hit by a ball in the back; getting a drink over the back; bumping into someone). Children were asked to imagine why the hypothetical actor did this to them, and using a 5-point scale, rated the degree to which they thought it was due to hostile intentions (e.g., The kid wanted to make fun of me), or self-blame (e.g., I must have done something to make it happen), or accidental reasons (1 = not the reason to 5 = really the reason). The hostile attributions scale with four items showed adequate reliability for each assessment point (fall: α = .77; spring: α = .79). For self-blaming attributions, only three items were retained for each assessment point because one of the hypothetical scenarios exhibited low internal consistency and did not improve this measure’s overall reliability (fall: α = .59; spring: α = .59). For the analyses, fall and spring measures were combined into one latent factor for each attribution mechanism (i.e., the latent factor for hostile attributions was specified using the eight individual items as the observed indicators and the latent factor for self blaming attributions was specified using the six individual items as the observed indicators across the Fall and Spring assessments).

Assessment of maladjustment (T1: spring grade 5 and T3: spring grade 7)

Parents and teachers reported on children’s maladjustment. Parents and teachers completed the 118-item Child Behavior Checklist or Teacher Report Form, respectively (Achenbach, 1991). For the most reliable and valid assessment of psychiatric symptoms of children, Kraemer and collaborators (2003) recommended combining parent reports, teacher reports, and self-reports (see also Perren, Von Wyl, Stadelmann, Burgin, & von Klitzing, 2006). For the current contribution we used teacher and parent reports (as we did not have self-reports).

The anxious/depressed and withdrawn behavior subscales of the CBCL and TRF (Achenbach, 1991) were used to measure children’s internalizing behaviors (anxious-depressed: α =.77-.84; withdrawn: α =.71-.81). Internal consistency of the cross-informant aggregate (4 subscales) is ICC=.68. The aggressive and delinquent behavior subscales of the CBCL and TRF (Achenbach, 1991) were used to measure children’s externalizing behaviors (aggressive: α = .89-.96; delinquent: α = .71-.82). Internal consistency of the cross-informant aggregate (4 subscales) is ICC=.76.

Data Analysis Plan

To address the substantive questions of interest in this study, structural equation modeling (SEM) was performed using Mplus Version 5.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2007). Full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) was used to treat missing data which allowed for all sample participants to be retained in the study. Instead of deleting observations with missing values, FIML uses all available information in all observations (without imputing missing values; see Enders, 2010; Schafer & Graham, 2002). Information on missing values is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics (mean, SD, range and percent missing) for study variables

| Mean | SD | Min | Max | % Missing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical victimization (T1) | 0.16 | 1.11 | −1.11 | 4.00 | 13.18% |

| Verbal victimization (T1) | 0.17 | 1.12 | −1.69 | 3.60 | 12.97% |

| Relational victimization (T1) | 0.17 | 1.08 | −1.60 | 3.62 | 13.18% |

| General victimization (T1) | 0.19 | 1.14 | −1.02 | 3.76 | 12.97% |

| Delinquency (TR: T1) | 1.19 | 0.29 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 9.83% |

| Delinquency (PR: T1) | 1.15 | 0.19 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 7.53% |

| Aggression (TR: T1) | 1.25 | 0.38 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 9.83% |

| Aggression (PR: T1) | 1.37 | 0.31 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 7.53% |

| Delinquency (TR: T3) | 1.22 | 0.34 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 7.95% |

| Delinquency (PR: T3) | 1.17 | 0.21 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 4.81% |

| Aggression (TR: T3) | 1.26 | 0.38 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 7.95% |

| Aggression (PR: T3) | 1.37 | 0.32 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 5.23% |

| Withdrawn (TR: T1) | 1.24 | 0.29 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 9.62% |

| Withdrawn (PR: T1) | 1.22 | 0.24 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 7.11% |

| Anxiety (TR: T1) | 1.18 | 0.22 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 10.46% |

| Anxiety (PR: T1) | 1.23 | 0.23 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 7.53% |

| Withdrawn (TR: T3) | 1.26 | 0.33 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 7.95% |

| Withdrawn (PR: T3) | 1.25 | 0.28 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 4.81% |

| Anxiety (TR: T3) | 1.18 | 0.19 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 8.37% |

| Anxiety (PR: T3) | 1.24 | 0.25 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 4.81% |

| Hostile Attribution Item 1 (T2F) | 2.47 | 1.23 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.14% |

| Hostile Attribution Item 2 (T2F) | 2.58 | 1.24 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.14% |

| Hostile Attribution Item 3 (T2F) | 2.62 | 1.19 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 50.84% |

| Hostile Attribution Item 4 (T2F) | 2.58 | 1.27 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 50.84% |

| Hostile Attribution Item 1 (T2S) | 2.51 | 1.17 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.51% |

| Hostile Attribution Item 2 (T2S) | 2.69 | 1.20 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.30% |

| Hostile Attribution Item 3 (T2S) | 2.73 | 1.23 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 50.63% |

| Hostile Attribution Item 4 (T2S) | 2.66 | 1.23 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 51.26% |

| Self-blame attribution Item 1 (T2F) | 2.43 | 1.21 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.14% |

| Self-blame attribution Item 2 (T2F) | 2.27 | 1.22 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 50.84% |

| Self-blame attribution Item 3 (T2F) | 2.51 | 1.37 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 50.84% |

| Self-blame attribution Item 1 (T2S) | 2.44 | 1.20 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.72% |

| Self-blame attribution Item 2 (T2S) | 2.29 | 1.09 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 50.84% |

| Self-blame attribution Item 3 (T2S) | 2.43 | 1.21 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 51.26% |

Note: T1 = Spring Grade 5, T2F = Fall Grade 6, T2S = Spring Grade 6, T3 = Spring Grade 7; TR = Teacher Report, PR = Parent Report.

Due to the large number of items used to measure parent and teacher reports of internalizing and externalizing behaviors, latent factors for internalizing and externalizing behaviors were specified using mean scores of each subscale as the observed indicators. A multi-informant design was used and latent factors for internalizing and externalizing behaviors at Time 1 and Time 3 were based on both parent and teacher reports.

A latent factor for victimization was specified based on four peer report indicators of victimization (i.e., physical, verbal, relational and general victimization). Latent factors for hostile and self-blaming attributions were specified using the individual items as the observed indicators for both measurement waves2. Within-time covariances were specified between latent factors. In addition, residual covariances were allowed to be estimated between observed indicators in cases in which they were specified in the modification indices and there was valid conceptual reasoning for their specification (e.g., same informant measures across and within time; Cole & Maxwell, 2003). To control for possible gender differences, gender was specified as a covariate (i.e., each of the latent variables in the model were separately regressed on gender). To test for mediation, indirect effects were estimated. Finally, two latent interaction effects were also specified (i.e., self-blaming attributions by victimization and hostile attributions by victimization). Mplus uses the latent moderated structural equations (LMS) method for specifying latent interaction effects (see Klein & Moosbrugger, 2000).

Model fit was assessed using multiple fit indices including the chi-square statistic, comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Simulation studies have found that models with an SRMR ≤ .05 (.08) and either a RMSEA ≤ .05 (.08) or a CFI ≥ .95 (.90) have good (adequate) model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). However, when specifying a latent interaction term in a model, overall model fit indices such as the chi-square statistic, CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR cannot be estimated because of a lack of a comparative (i.e., unrestricted) model (see Klein & Muthén, 2007). To address this issue, two models were specified, one with the interaction effects and a second model without interaction effects. These two models could then be compared using a nested model Likelihood Ratio Test [LR = −2 * (LogLRestricted - LogLFull)]. If the model without the interaction effect had adequate overall model fit and the LR test found that adding interaction effects significantly improved model fit, then we concluded that there was adequate model fit in the model with the interaction effects.

Results

Bivariate analyses

First, Pearson correlation analyses were computed to analyze bivariate associations between study variables. As can be seen in Table 2 boys were more likely to be victimized. Higher levels of peer victimization were associated with higher levels of hostile attributions and higher levels of internalizing and externalizing problems. Higher levels of self-blaming attributions were associated with lower levels of hostile attributions and externalizing problems. In contrast, hostile attributions were positively associated with externalizing problems. Internalizing and externalizing problems showed considerable stability from grade 5 (T1) to grade 7 (T3) and were also positively associated with each other.

Table 2.

Pearson correlations between study variables (latent variables)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Victimization (T1) | |||||||

| 2. Self-blaming attributions (T2) | .00 | ||||||

| 3. Hostile attributions (T2) | .20*** | −.31*** | |||||

| 4. Internalizing (T1) | .15** | .00 | .04 | ||||

| 5. Internalizing (T3) | .28*** | −.01 | .10 | .62*** | |||

| 6. Externalizing (T1) | .18*** | −.14* | .12* | .70*** | .34*** | ||

| 7. Externalizing (T3) | .25*** | −.16* | .22*** | .45*** | .69*** | .71*** | |

| 8. Gender (male) | .20*** | −.04 | .09 | .01 | −.06 | .08 | .04 |

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

Structural Models

To test the hypothesized effects in this study, two models were estimated. The first model tested for main and indirect effects (i.e., interaction effects were not included). This model had adequate model fit, χ2 (527) = 1250.87, p ≤ .001, RMSEA = .05, CFI = .90, SRMR = .08. A second model was then specified by adding two latent interaction effects (victimization by hostile attributions and victimization by self-blame attributions) to the first model (see Figure 1). To determine whether inclusion of the interaction effects improved model fit, a likelihood ratio test was used to compare these two models, the one with the interaction effects specified (LogLFull = −7640.61) and the model without the interaction effects (LogLRestricted = −7647.36). Including the interaction effects improved overall model fit; LR (df = 2) = 13.50, p = .001. In the following sections, the model results are presented for externalizing and internalizing problems separately.

Figure 1.

Unstandardized (standardized) path estimates for structural model with latent interaction effects. Dashed circles represent interaction effects. Standardized estimates are from model when interaction effects were not specified. Gender was included as a covariate in this model, but is not shown in this figure. Dashed lines represent non-significant paths at p < .05. Curved arrows between T2 and T3 measures represent correlated errors. * p ≤ .05. ** p ≤ .01. *** p ≤ .001.

Multivariate analyses predicting externalizing problems

There were significant effects of T1 peer victimization on T3 externalizing problems (B = .11, p < .01), even when controlling for prior levels of externalizing behaviors at T1 (B = .71, p < .001), suggesting that peer victimization predicted increases in externalizing problems over time. Time 1 victimization significantly predicted T2 hostile attributions (B = .19, p = .001), indicating that children who were more victimized were more likely to have hostile attributions. Time 2 hostile attributions predicted increases in externalizing behaviors (B = .09, p < .01). Moreover, mediation analyses indicated that hostile attributions partially mediated the association between victimization and externalizing problems (indirect effect, B = .02, p = .04; direct effect, B = .10, p < .01; total effect, B = .12, p < .01). More specifically, about 13% of the total effect of peer victimization on increases in externalizing problems was mediated by hostile attributions. The hostile attributions by victimization interaction effect was not significant.

Multivariate analyses predicting internalizing problems

There were significant effects of T1 peer victimization on T3 internalizing behaviors (B = .20, p < .001), even when controlling for prior levels of internalizing behaviors at T1 (B = .61, p < .001), suggesting that peer victimization predicted increases in internalizing problems over time. Time 1 victimization did not significantly predict T2 self-blaming attributions, and T2 self-blaming attributions did not predict T3 internalizing behaviors. Thus, it was not necessary to test for indirect (i.e., mediated) pathways between victimization, self-blaming attributions and internalizing problems. Finally, the analyses indicated significant sex differences with boys having lower levels of internalizing problems at T3 (B = -.10, p = .01), and higher levels of victimization at T1 (B = .20, p < .001).

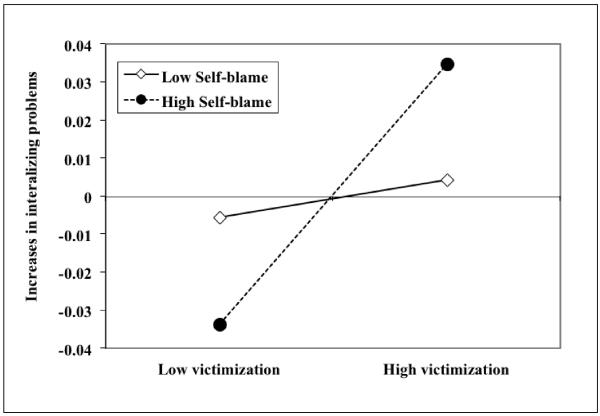

This model also yielded a significant interaction effect between self-blaming attributions and peer victimization (b = .03, p < .01). To evaluate the significant interaction, we used the procedures outlined by Aiken and West (1991). The lines in Figure 2 represent associations (slopes) between the independent and dependent variables for high and low levels (+-1 SD) of the moderator. As can be seen in Figure 2, the impact of peer victimization on the increase in internalizing problems from T1 and T3 is especially pronounced in children who had high levels of self-blaming attributions. With low levels of self-blame (1 SD below the mean), victimization was not associated with increases in internalizing outcomes. But for children with high self blame attributions, a one unit increase in victimization was roughly associated with a .04 unit residual change in internalizing problems, after controlling for Time 1 internalizing problems.

Figure 2.

Interaction effect of victimization x self-blame on increases in internalizing symptoms

Discussion

Findings from this study were consistent with the premise that children’s attributions play a mediating or moderating role in the impact of peer victimization on later maladjustment. Results imply that hostile attributions can be considered as one potential mechanism through which negative experiences with peers lead to increases in children’s aggressive and delinquent behaviors. Under higher levels of self-blame, a stronger predictive link was observed between peer victimization and children’s internalizing problems - a finding that corroborated the hypothesis that self-blame exacerbates victimization’s effects on internalizing problems.

Attributions and externalizing problems

In line with other studies, we found that peer victimization predicted gains in externalizing symptoms over time (Reijntjes et al., 2011). Hostile attributions also predicted increases in externalizing problems. The fact that peer victimization at T1 was predictive of hostile attributions one year later was consistent with the possibility that hostile attributions act as a mediator of increases in externalizing problems. However, as the direct impact of peer victimization remained significant and had a stronger effect size, other mechanisms might also be strongly related to the observed developmental pattern. Nevertheless, our results implicate hostile attributions as a mechanism that might partially account for the vicious cycle of victimization and aggression that has been observed in some children. In research on bullying, for example, victimization appears to be more stable for the group of aggressive victims than for the group of passive victims (Alsaker, 2011). This may be because, in some children (probably those with a proneness for aggressive behavior), peer victimization serves to intensify hostile attributions which, in turn, increases aggressive reactions towards others and precipitates further victimization. Cycles such as this one may lead to increases in externalizing problems.

Attributions and internalizing problems

As expected, we also found that peer victimization predicted increases in internalizing symptoms over time (Reijntjes et al., 2010). In contrast to suggestions made by Gibb and Alloy (2006) and Cole (2008), our results lend more support to a diathesis-stress model regarding self-blame than to a mediational model. Stronger linkages between peer victimization and increases in internalizing problems were found for children who exhibited higher rather than lower levels of self-blame. To interpret the size of the interaction effect (which is only modest), it has to be taken into account that internalizing problems were rather stable across time (i.e., there is only a small proportion of residual change to be predicted by other variables). In contrast to other studies (Graham et al., 2009; Singh & Bussey, 2011), self-blame was not directly associated with peer victimization and depressive symptoms. This latter finding might be partly explained by methodological limitations. As Graham and Juvonen (1998) pointed out, it is important to distinguish between behavioral (unstable and controllable) and characterological (stable and uncontrollable) self-blame. This distinction was not made in this study, but rather the items used to assess self-blame were framed so as tap children’s perceptions of the controllability of events (e.g., “I must have done something to make it happen”). However, as we assessed self-blaming attributions at two different time points (fall and spring of the same school year) on three different scenarios, high scores also indicate a person’s rather stable tendency to attribute causes of ambiguous negative events to him- or herself.

As we had no specific hypothesis regarding associations between self-blame and externalizing problems, or hostile attributions and internalizing problems respectively, we did not include them in the statistical model. However, bivariate correlations show that hostile attributions are not associated with internalizing problems and self-blame shows a small negative correlation with externalizing problems.

Finally, in line with findings regarding well-known gender differences in psychopathology (Kistner, 2009), girls showed higher levels of internalizing symptoms. However, no gender differences regarding externalizing symptoms were found. Boys were more frequently victimized, which is a common finding in bullying research (Smith et al., 1999). However, gender was not associated with attribution styles. Future studies might investigate whether gender moderates these associations.

Methodological strengths, limitations and research implications

Our study has certain strengths and limitations. To avoid inflated correlations due to shared method variance we used multi-informant data. Victimization was assessed through peer reports, attributions through self-reports and maladjustment through parents and teachers. To assess children’s attributions we aggregated data across two time points to create a robust measure. However, we did not distinguish between characterological and behavioral self-blame, a distinction which would be important to consider in future studies.

We used longitudinal data with three measurement points to investigate the postulated meditational mechanisms. In line with suggestions by Cole and Maxwell (2003) we controlled for initial levels of maladjustment so that it was possible to predict changes in maladjustment. However, we could not control for initial levels of attributions because these data were not collected at earlier time points. Future investigators who study the role of social cognitions as mediators between life events and outcomes should be more rigorous in collecting this kind of data at every time point to allow for a more sophisticated testing of causal mechanisms (Cole & Maxwell, 2003). To test our hypotheses we used structural equation models, this allowed us to test simultaneously the impact of hostile and self-blaming attributions on internalizing and externalizing symptoms.

Practical implications

Our results also have clinical implications. In line with cognitive approaches to treat psychopathological symptoms, changing children’s attributions might be considered as a potential intervention strategy to reduce negative outcomes related to negative peer experiences. Reducing hostile attributions in children might reduce their reactive aggression whereas reducing tendencies for self-blame might reduce depressive symptoms. However, if we aim to alter children’s attributions about negative social situations we have to give them positive alternatives. But what are positive attributions in relation to peer victimization? In ambiguous situations (like in our hypothetical vignettes) accidental (e.g., bad luck) or prosocial (e.g., they wanted to play with me) attributions might be a positive alternative as children’s coping strategies and responses that are based on such inferences might produce more positive peer interactions. However, in a real life situation being a victim of peer aggression or bullying is in most cases non-ambiguous and aggressors behave hostile. Thus, in this circumstance, we cannot speak of hostile attribution “bias”. Blaming the other (“it was them”, i.e., bullies are like this) might be even be protective for children’s well-being. For example, Huitsing and collaborators (2010) found that victims were relatively better psychologically adjusted when they were in classrooms where few bullies harassed many victims. These latter findings were consistent with a social misfit model (i.e., victims occupy non-normative positions in the classroom) and attributional premises (i.e., children attribute blame for victimization to either themselves or external factors; Huitsing et al., 2010). Likewise, internal blame might also be protective because it might lead to adaptive behavioral responses. Self-blame (i.e., holding oneself-responsible for a negative event) is an attribution style with high controllability (Abramson & Sackheim, 1977) and thus with a high potential for change. In relation to this, Graham and Juvonen (1998) made an important distinction between characterological and behavioral self-blame. In their perspective characterological self-blame are attributions in relation to unchangeable person characteristics such as personality. On the other hand, behavioral self-blame is behaviors such as “I was in a wrong place”. According to Graham and Juvonen (1998), only characterological self-blame is associated with peer victimization and internalizing problems. Although (behavioral) self-blame might be adaptive as it can lead to behavioral changes, self-blame might also lead to low self-regard which may invite victimization (Egan & Perry, 1998). Low self-regard has been identified as another mediating path leading from victimization to maladjustment (Troop-Gordon & Ladd, 2005).

Children’s attributions are strongly linked to their behavior. As bullying is an interactional phenomenon involving bullies, victims, and bystanders (Pepler, Craig, & O’Connell, 1999), victims’ reactions may play an important role in maintaining, escalating or stopping bullying behavior. According to the social information processing model, social cognitions shape children’s behavior in social situations, thus self-blame and hostile attributions might lead to helpless or aggressive responses, respectively in bullying situations. However, helplessness and counteraggression were perceived by students to perpetuate bullying, whereas nonchalance or having a friend to help was perceived as effective in diminishing or stopping bullying (Salmivalli, Karhunen, & Lagerspetz, 1996; Kochenderfer & Ladd, 1997). According to this, attributions in victimization situations may shape children’s behavior and thus play an important role in stabilizing one’s victim role. Nevertheless, it must be kept in mind that we assessed attributions not related to real victimization events but in relation to ambiguous and potentially provocative peer situations. Children’s attributions, social cognitions and behavior might vary considerably in relation to the specific social situations. Investigating children’s attributions more specifically in relation to the social situation we aim to investigate (i.e., being a victim of peer aggression) might permit greater insight into potential associations between cognitions and behavior and their roles in children’s development. For example, Kochenderfer-Ladd and Visconti (2011) investigated children’s attributions not in relation to ambiguous situations but asked what children would think if they were “picked on”. A very interesting internal attribution emerged in this qualitative study: children said others were jealous. In fact, jealousy emerged as a protective factor against internalizing problems (Kochenderfer Ladd & Visconti, 2011, Perren & Sticca, 2012). In future studies, investigators should assess children’s attributions not only in ambiguous (hypothetical) peer situations but also in non-ambiguous (and maybe real-life) situations.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that hostile attributions may at least play a modest role in sustaining the vicious cycle of being victimized and being aggressive whereas self-blame may impair children’s well-being. Thus victims’ interpretations regarding potential reasons or causes of victimization seem to be a highly relevant step in children’s information processing and corresponding behavior and well-being: Whether children tend to attribute hostile intent to peers or whether they tend to attribute blame on themselves is related to the pattern and strengths of maladjustment.

Key points.

- Peer victimization may increase internalizing and externalizing problems. This negative impact might be mediated or moderated by children’s attributions.

- Hostile attributions partially mediated the impact from victimization to later externalizing symptoms. Although the effect size was only moderate, they nonetheless predicted increases externalizing problems over two years. Hostile attributions may thus have an impact on sustaining the vicious cycle of being victimized and being aggressive.

- Although self-blaming attributions were not associated with peer victimization, for children with higher levels of self-blame, peer victimization was linked more strongly with increases in internalizing problems.

- In line with cognitive approaches to treat psychopathology, changing children’s attributions might be considered as a potential intervention strategy to reduce negative outcomes related to negative peer experiences.

Acknowledgement

This study was conducted as part of the Pathways Project at the University of Illinois, a larger longitudinal investigation of children’s social/psychological/scholastic adjustment in school contexts which is supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants 1-RO1MH-49223 and 2-RO1MH-49223 to Gary W. Ladd). Special appreciation is expressed to all the children and parents who made this study possible, and to members of the Pathways Project for assistance with data collection. The authors declare there are no competing or potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Due to time constraints for the assessment about half of participants only reported attributions for two scenarios, however, no significant differences emerged between those who reported on two versus four scenarios. Thus, all available data was used.

The analyses were also computed with the fall and spring attribution measures separately. With one exception, all significant paths reported in this paper could be replicated in either model. In the model including the fall attribution measure the path from hostile attribution to later externalizing symptoms did not reach significance anymore, but the direction of effects remained the same.

Conflict of interest statement: There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abramson LY, Alloy LB, Hankin BL, Haeffel GJ, MacCoon DG, Gibb BE, Gotlib IH, Hammen CL. Cognitive vulnerability-stress models of depression in a self-regulatory and psychobiological context. Guilfor; New York: 2002. pp. 268–294. [Google Scholar]

- Abramson LY, Sackheim HA. A paradox in depression: Uncontrollability and self-blame. Psychological Bulletin. 1977;84(5):838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL/4-18, YSR, and TRF profiles. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; Burlington, VT: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG, Reno RR. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications, Inc.; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alsaker FD. Lessons learned from research in kindergarten. Paper presented at the Biennial Meeting of the European Society for Developmental Psychology (Keynote address); Bergen, Norway. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Arseneault L, Milne BJ, Taylor A, Adams F, Delgado K, Caspi A, et al. Being bullied as an environmentally mediated contributing factor to children’s internalizing problems. Archives of Paediatric and Adolecent Medicine. 2008;162:145–150. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvete E, Orue I. The impact of violence exposure on aggressive behavior through social information processing in adolescents. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2011;81(1):38–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camodeca M, Goossens FA. Aggression, social cognitions, anger and sadness in bullies and victims. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;Vol.46(2):186–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterson J, Hunter SC. Cognitive mediators of the effect of peer victimization on loneliness. British Journal of Educational Psychology. 2010;80(3):403–416. doi: 10.1348/000709909X481274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112(4):558. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Ciesla JA, Dallaire DH, Jacquez FM, Pineda AQ, LaGrange B, et al. Emergence of attributional style and its relation to depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117(1):16–31. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Dodge KA. A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:74–101. [Google Scholar]

- Dell Fitzgerald P, Asher SR. Aggressive-rejected children’s attributional biases about liked and disliked peers. Paper presented at the 95th annual convention of the American Psychological Association; New York, NY. 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA. Translational science in action: Hostile attributional style and the development of aggressive behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:791–814. doi: 10.1017/s0954579406060391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan SK, Perry DG. Does low self-regard invite victimization? Developmental Psychology. 1998;34(2):299–309. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.2.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Applied missing data analysis. Guilford Press; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Alloy LB. A prospective test of the hopelessness theory of depression in children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35(2):264–274. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Bellmore A, Nishina A, Juvonen J. “It must be me”: Ethnic diversity and attributions for peer victimization in middle school. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:487–499. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9386-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Juvonen J. Self-blame and peer victimization in middle school: An attributional analysis. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34(3):587–599. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Juvonen J. An attributional approach to peer victimization. In: Juvonen J, Graham S, editors. Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized. Guilford Press; New York: 2001. pp. 49–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hoglund WL, Leadbeater BJ. Managing threat: Do social-cognitive processes mediate the link between peer victimization and adjustment problems in early adolescence? Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;Vol.17(3):525–540. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Huitsing G, Veenstra R, Sainio M, Salmivalli C. “It could be me or it must be them?”: The impact of the social network position of bullies and victims on victims’ adjustment. Social Networks. 2010 in press. [Google Scholar]

- Keil V, Price JM. Social information-processing patterns of maltreated children in two social domains. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2009;Vol.30(1):43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kistner JA. Sex differences and child psychopathology: Introduction to special section. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38:453–459. doi: 10.1080/15374410902976387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein A, Moosbrugger Maximum likelihood estimation of latent interaction effects with the LMS method. Psychometrika. 2000;65:457–474. [Google Scholar]

- Klein AG, Muthén BO. Quasi-maximum likelihood estimation of structural equation models with multiple interaction and quadratic effects. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2007;42:647–467. [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer Ladd B, Visconti KJ. Children’s attributions: Moderators of the effects of peer victimization on loneliness. Paper presented at the SRCD Biennial Meeting; Montréal. April 2011.2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer BJ, Ladd GW. Victimized children’s responses to peers’ aggression: Behaviors associated with reduced versus continued victimization. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9:59–73. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer H, Measelle JR, Ablow JC, Essex MJ, Boyce WT, Kupfer DJ. A new approach to integrating data from multiple informants in psychiatric assessment and research: Mixing and matching contexts and perspectives. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1566–1577. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW. Children’s peer relations and social competence. A century of progress. Yale University Press; New Haven: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Kochenderfer-Ladd B. Identifying victims of peer aggression from early to middle childhood: Analysis of cross-informant data for concordance, estimation of relational adjustment, prevalence of victimization, and characteristics of identified victims. Psychological Assessment. 2002;14(1):74. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.14.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemerise EA, Arsenio WF. An integrated model of emotion processes and cognition in social information processing. Child Development. 2000;71:107–118. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis SP, Waschbusch DA. Alternative approaches for conceptualizing children’s attributional styles and their associations with depressive symptoms. Depression and Anxiety. 2008;25:37–46. doi: 10.1002/da.20322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieson LC, Murray-Close D, Crick NR, Woods KE, Zimmer-Gembeck M, Geiger TC, et al. Hostile intent attributions and relational aggression: The moderating roles of emotional sensitivity, gender, and victimization. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9515-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 5th ed Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pepler D, Craig WM, O’Connell P. Understanding bullying from a dynamic systems perspective. In: Slater A, Muir D, editors. The Blackwell reader in development psychology. Blackwell Publishers; Malden, MA: 1999. pp. 440–451. [Google Scholar]

- Perren S, Sticca F. (Cyber)victimization and Depressive Symptoms: Can Certain Attributions Buffer the Negative Impact?. Poster presented at the 14th Biennial Meeting Of the Society for Research on Adolescence; Vancouver, BC, Canada. March 08-10, 2012.2012. [Google Scholar]

- Perren S, Von Wyl A, Stadelmann S, Burgin D, von Klitzing K. Associations between behavioral/emotional difficulties in kindergarten children and the quality of their peer relationships. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45(7):867–876. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000220853.71521.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pornari CD, Wood J. Peer and cyber aggression in secondary school students: The role of moral disengagement, hostile attribution bias, and outcome expectancies. Aggressive Behavior. 2010;Vol.36(2):81–94. doi: 10.1002/ab.20336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Cheah CSL, Guyer AE. Peer victimization, cue interpretation, and internalizing symptoms: Preliminary concurrent and longitudinal findings for children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34(1):11–24. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reijntjes A, Kamphuis JH, Prinzie P, Boelen PA, van der Schoot M, Telch MJ. Prospective linkages between peer victimization and externalizing problems in children: A meta-analysis. Aggress Behav. 2011;37(3):215–222. doi: 10.1002/ab.20374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reijntjes A, Kamphuis JH, Prinzie P, Telch MJ. Peer victimization and internalizing problems in children: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Child abuse & neglect. 2010;34(4):244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmivalli C, Karhunen J, Lagerspetz KMJ. How do the victims respond to bullying? Aggressive Behavior. 1996;22(2):99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP, Peterson C, Kaslow N, Tanenbaum RL, Alloy L, Abramson LY. Attributional style and depressive symptoms among children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1984;93:235–238. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.93.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P, Bussey K. Peer Victimization and Psychological Maladjustment: The Mediating Role of Coping Self-Efficacy. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21(2):420–433. [Google Scholar]

- Smith PK, Morita Y, Junger-Tas J, Olweus D, Catalano R, Slee P. The Nature of School Bullying: A Cross-National Perspective. Routledge; London: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Troop-Gordon W, Ladd GW. Trajectories of peer victimization and perceptions of the self and schoolmates: Precursors to internalizing and externalizing problems. Child Development. 2005;Vol.76(5):1072–1091. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner B. An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review. 1985;92:548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung RS, Leadbeater BJ. Does hostile attributional bias for relational provocations mediate the short-term association between relational victimization and aggression in preadolescence? Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007;36(8):973–983. [Google Scholar]