Abstract

Purpose

To characterize fast and slow diffusion components in Diffusion-weighted MRI (DW-MRI) of pediatric Crohn’s disease (CD). Overall diffusivity reduction as measured by the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) in patients with CD has been previously demonstrated. However, the ADC reduction may be due to changes in either fast or slow diffusion components. In this study we distinguished between the fast and slow diffusion components in the DW-MRI signal decay of pediatric CD.

Materials and Methods

We acquired MRI from 24 patients, including MR enterography (MRE) and DW-MRI with 8 b-values [0–800 s/mm2]. We characterized fast and slow diffusivity by intra-voxel incoherent motion (IVIM) model parameters (f, D*, D), and overall diffusivity by ADC values. We determined which model best described the DW-MRI signal decay. We assessed the influence of the IVIM model parameters on the ADC. We evaluated differences in model parameter values between the enhancing and non-enhancing groups.

Results

The IVIM model described the observed data significantly better than the ADC model (p=0.0088). The ADC was correlated with f (r=0.67, p=0.0003), but not with D (r=0.39, p=0.062) and D* (r=−0.39, p=0.057). f values were significantly lower (p<0.003) and D* values were significantly higher (p=0.03) in the enhancing segments, while D values were not significantly different between the groups (p=0.14).

Conclusion

For this study population, the IVIM model provides a better description of the DW-MRI signal decay than the ADC model. The reduced ADC is related to changes in the fast diffusion rather than to changes in the slow diffusion.

Keywords: Crohn’s disease, Diffusion-weighted MRI, Intravoxel incoherent motion, apparent diffusion coefficient

INTRODUCTION

An estimated 1.4 million people in the United States live daily with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Of those diagnosed with an IBD, half are believed to have Crohn’s disease, one of two primary forms of IBD along with ulcerative colitis: At least 10% are under the age of 18 (1, 2). CD can arise within any section of the gastrointestinal tract; it has a chronic, relapsing, and remitting clinical course. Long-standing inflammation can result in bowel obstruction, stricture, fistula, and/or abscess. In addition, there is an increased risk for small and large bowel malignancy in areas of chronic inflammation (3). Assessment of inflammatory activity with imaging biomarkers may ultimately play a crucial role in all phases of care (4).

Diffusion-weighted MRI (DW-MRI) is a non-invasive imaging technique sensitive to the motion of water molecules inside the body.

In current practice, it is common for the overall diffusivity of the tissue to be quantitatively characterized by the mono-exponential signal decay model, with the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) as the decay rate parameter (5).

Recently, diffusion weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging (DW-MRI), along with associated ADC measurements, has been shown to reflect abnormal activity in Crohn’s patients. Specifically, intestinal inflammatory lesions are characterized by brighter signal in the b-value images and lower ADC values relative to normal segments. The reduction of ADC values in abnormal segments has been suggested to reflect increased cellularity, which, if present, would restrict the diffusion of the water molecules in the tissue (6–9).

However, the DW-MRI signal decay is known to reflect a combination of both a slow diffusion component associated with the Brownian motion of water molecules and a fast diffusion component associated with bulk motion of intravascular molecules in the micro-capillaries (10–13). Specifically, the reduction in microvascular volume that is a feature of the inflammatory process in Crohn’s disease (14–16) may induce changes in the fast diffusion decay component in DW-MRI which cannot be identified independently using the mono-exponential ADC model analysis.

In this study, we analyzed DW-MRI data of pediatric Crohn’s disease patients with the intra-voxel incoherent motion model (IVIM), in order to identify both slow and fast diffusion signal decay components (10–13), and with the mono-exponential ADC model in which the signal decay coefficient encapsulates both fast and slow diffusion components. We sought to establish if either both fast and slow diffusion or only one of the diffusion components is altered in enhancing ileum segments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data Acquisition

We carried out the study according to a protocol approved by our Institutional Review Board.

We acquired DW-MRI and MR enterography (MRE) data from 24 consecutive patients with confirmed Crohn’s disease (15 males, 9 females; mean age 14.7 years; range: 5–24 years), who underwent a clinically indicated MRI study between January 1, 2011 and October 31, 2011 in our outpatient MRI department. We carried out MRI imaging studies of the abdomen and the pelvic using a 1.5-T unit (Magnetom Avanto, Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) and a body-matrix coil and spine array coil for signal reception. We performed free-breathing single-shot echo-planar imaging using the following parameters: repetition time/echo time (TR/TE) = 6800/59 ms; SPAIR fat suppression; matrix size = 192×156; field of view = 300×260 mm; slice thickness/gap = 5 mm/0.5 mm; 40 axial slices; 8 b-values = 5,50,100,200,270,400,600,800 s/mm2 with 1 average. We used a tetrahedral gradient scheme, first proposed by Conturo et al. (17), to acquire 4 images at each b-value with an overall scan acquisition time of 4 min.

The tetrahedral gradient scheme simultaneously applies all three orthogonal gradients with maximum gradient strength to construct the image of the four noncollinear gradients at each b-value. This method allows us to acquire high b-value images with a lower TE than required by the three-scan trace weighted imaging method and has an inherently high SNR for measurements of averaged diffusivity (17). We generated diffusion trace-weighted images at each b-value using geometric averages of the images acquired in each diffusion sensitization direction as described by Mulkern et al. (18).

MR enterography (MRE) protocol included polyethylene glycol administration for bowel distention and gadolinium-enhanced, dynamic 3D VIBE (volume- interpolated breath hold exam) in the coronal plane.

Reference-Standard MRE Radiological Review

Two board certified radiologists (M.C) and (J.P-R), each with 10 years of experience in pediatric abdominal imaging, reviewed the MRE data independently. Disease activity was defined as abnormal bowel wall thickening and enhancement in the gadolinium-enhanced images by each of the readers. In case of a disagreement between the two reviewers, consensus was reached by joint reading of the data. From the consensus decision, we classified each patient ileum qualitatively as enhancing or non-enhancing.

DW-MRI Data Analysis

The ileum was identified independently on the DW-MRI data by another board-certified radiologist (M.B) with 1 year of experience in abdominal imaging who was blinded to the MRE data and review. We manually annotated the ileum wall on the DW-MRI data of each patient (b-value=200 s/mm2) using the ITK-SNAP software tool (19).

We averaged the DW-MRI signal over the annotated region of interest of each patient to obtain high-quality ADC and IVIM estimations (12).

The IVIM model of DW-MRI signal decay assumes a signal decay function of the form (10, 11, 13):

| [1] |

where si is the signal at b-value=bi, s0 is the baseline signal; D is the slow diffusion decay associated with extravascular water molecules’ motion; D* is the fast diffusion decay associated with the intravascular water molecules’ motion; and f is the fraction between the two compartments.

We estimated the IVIM model parameters from the DW-MRI data using the entire range of b-value images acquired, with a maximum-likelihood estimator proposed by Freiman et al. (20).

In addition, we estimated the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) of the mono-exponential signal decay model:

| [2] |

where si, bi, and s0 are as defined above.

We calculated the ADC using three established methods: 1) using the entire range of b-value images (ADCall) (21); 2) using two b-value images with b-values of 0,600 s/mm2 (ADC0-600) (8), and; 3) using three b-value images with b-values of 0,50,800 s/mm2 (ADC0-50-800) (6).

Finally, we calculated mean ADC and IVIM values over the ileum region of interest for each subject.

Statistical Analysis

We performed the statistical analysis with standard statistical software (Matlab® R2010b; The MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). For all analyses, p<.05 was accepted as a statistically significant difference and Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of the data.

Model Selection

We determined whether the DW-MRI signal decay in Crohn’s disease patients contains fast and slow diffusion components or only a single decay component. We calculated the goodness of fit of the IVIM model and the mono-exponential ADC model to the observed DW-MRI data by means of the Akaike information criterion with correction for finite sample size (AICc) (22, 23). Given a set of models for the data, the preferred model is the one with the minimum AICc value. We compared differences in AICc between the IVIM and ADC models using the paired Student’s t-test.

The Influence Of Fast And Slow Diffusion On The ADC

We examined the influence of slow and fast diffusion on the overall diffusivity as measured by the ADC. First, we compared the slow diffusion compartment of the IVIM model (D) and the ADC values (i.e. ADCall, ADC0-600 and ADC0-50-800) using one-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA).

We sought to examine whether or not the fast diffusion component lead to a difference in ADC estimates was associated with disease statues (enhanced vs. non-enhanced).

We compared the differences in ADC and D estimates between the enhancing and non-enhancing groups using two-sample two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Next, we assessed the correlation between the ADCall values and the IVIM model parameters using Pearson correlation.

Group Differences Analysis

We examined whether differences in disease stage (i.e enhanced vs. non-enhanced) are reflected in the quantitative DW-MRI measurements. We evaluated the differences in ADCall, ADC0-600, ADC0-50-800, and the IVIM values between the enhancing and non-enhancing groups using two-sample, two-tailed Student’s t-test.

RESULTS

Conventional MRE review by 2 independent radiologists found enhancing ileum in 11 (46%) patients and non-enhancing ileum in 13 (54%) patients.

Model Selection

Table 1 summarizes the DW-MRI signal decay model fitting comparison. The DW-MRI signal decay exhibits a composition of fast and slow diffusion signal decays, reflected by significantly lower AICc of the IVIM model (98.63±41.18) as compared to the AICc of the ADCall model (195.4±169.3, p=0.0088) for the entire study cohort (n=24). In the non-enhancing group (n=11), the AICc of the IVIM model (105.3±47.23) was significantly lower than that of the ADCall model (281.1±187.1, p=0.0063). In the enhancing group (n=13), there was no significant difference between the AICc of the IVIM model (90.74±33.1) and the AICc of the ADCall model (94.05±55.02, p=0.75), which suggests a substantial change in the nature of the diffusion signal between the non-enhancing and the enhancing group.

Table 1.

Model selection

| Group | AICc (ADCall) | AICc (IVIM) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-enhancing (n=13) | 281.1±187.1 | 105.3±47.23 | 0.0063 |

| Enhancing (n=11) | 94.05±55.02 | 90.74±33.1 | 0.75 |

| All (n=24) | 195.4±169.3 | 98.63±41.18 | 0.0088 |

Akaike information criterion with correction for finite sample size (AICc) of the ADC and IVIM models for non-enhancing and enhancing ileal segments. Data are means ± standard deviations. Difference between the AICc of the ADCall and IVIM models were evaluated with paired Student’s t-test. Significant values are in bold. The IVIM model better describes the DW-MRI signal than the mono-exponential ADC model.

The Influence Of Fast And Slow Diffusion On The ADC

Table 2 summarizes the relation between the slow diffusion as measured by the IVIM model parameter D and the overall diffusivity as measured by the ADC. The ADCall (2.1±0.7 µm2/ms), ADC0-600 (2.6±1.1 µm2/ms), and ADC0-50-800 (2.1±0.6 µm2/ms) of the entire study cohort (n=24) were significantly higher than the D parameter values (1.5±0.6 µm2/ms, p<10−6).

Table 2.

ADC and IVIM D values comparison

| Group | ADC0-600 | ADC0-50-800 | ADCall | D | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-enhancing (n=13) | 3.3 ± 0.9 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.7 | <10−6 |

| Enhancing (n=11) | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 0.003 |

| All (n=24) | 2.6 ± 1.1 | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | <10−6 |

Comparison between ADC and IVIM D values for non-enhancing and enhancing ileal segments. Data are means ± standard deviations and in units of µm2/ms. Difference between ADCall, ADC0-600, ADC0-50-800, and D were evaluated with repeated measures one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test. Significant values are in bold. The ADC values are significantly higher than the slow diffusion parameter (D), reflecting the influence of the fast diffusion component on the overall diffusivity. The magnitude of the fast diffusion influence on the ADC depends on the b-values used to calculate the ADC. A larger influence is observed in the non-enhancing group as compared to the enhancing group.

In the enhancing group (n=11), the ADCall (1.5±0.3 µm2/ms), ADC0-600 (1.7±0.4 µm2/ms), and ADC0-50-800 (1.6±0.4 µm2/ms) were significantly higher than the D parameter values (1.3±0.4 µm2/ms, p=0.003). In the non-enhancing group (n=13), the ADCall (2.7±0.5 µm2/ms), ADC0-600 (3.3±0.9 µm2/ms), and ADC0-50-800 (2.6±0.5 µm2/ms) were significantly higher than the D parameter values (1.7±0.7 µm2/ms, p=10−6).

The differences between the slow diffusion values as measured by the D parameter of the IVIM model and the overall diffusivity as measured by the ADCall, the ADC0-600, and the ADC0-50-800 were significantly larger in the non-enhancing group than in the enhancing group (H0: ADC-D=0, H1: ADC-D≠0, n1=11, n2=13, paired Student’s t-test, p<0.01).

Fig. 1 depicts the relation between the ADCall values and the IVIM model parameters. The ADCall values were strongly correlated with the f values (r=0.67, p=0.0003), while have only non-significant weak inverse-correlation with the D* values (r=−0.39, p=0.057) and non-significant weak correlation with the D values (r=0.39, p=0.062).

Fig. 1.

Scatter plots of the ADCall values versus: (A) the IVIM fast diffusion fraction parameter (f); (b) the IVIM fast diffusion parameter (D*), and; (C) the IVIM slow diffusion parameter (D). The black line represents the trend as modeled using linear regression. The ADCall values are strongly correlated with the f values while having only non-significant correlation with the D* and D values.

Group Differences Analysis

Table 3 summarizes the differences in disease stage (i.e enhanced vs. non-enhanced) as reflected in the quantitative DW-MRI measurements. The ADC0-600 and ADC0-50-800 and ADCall were significantly lower in the enhancing ileal segments (1.7±0.4 vs. 3.3±0.9, 1.6±0.4 vs. 2.6±0.5, and 1.5±0.3 vs. 2.7±0.5 µm2/ms, p<10−4). The IVIM model f parameter was significantly lower in the enhancing segments (0.27±0.2 vs. 0.59±0.26, p<0.003) and the IVIM model D* parameter was significantly higher in the enhancing segments (51.9±48.9 vs. 18.5±16.7 µm2/ms, p=0.03).

Table 3.

DW-MRI group differences

| Parameter | Non-enhancing (n=13) | Enhancing (n=11) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADC0-600 | 3.3 ± 0.9 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 2.75×10−5 |

| ADC0-50-800 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 2.5×10−5 |

| ADCall | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.4×10−6 |

| f | 0.59 ± 0.26 | 0.27 ± 0.2 | 0.0023 |

| D | 1.7 ± 0.7 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 0.14 |

| D* | 18.5 ± 16.7 | 51.9 ± 48.9 | 0.03 |

Summary statistics of DW-MRI parameters for non-enhancing and enhancing ileal segments. Data are means ± standard deviations. ADC, D and D* are in units of µm2/ms. Difference between non-enhancing and enhancing ileal segments was evaluated by using the two-tailed two-sample Student’s t-test. Significant values are in bold. The significant reduction in the ADC values of enhancing segments is associated with the significant reduction in the fast diffusion fraction (f) and not with the variations in D and D* which are not significantly different between the groups.

There were no significant differences in the IVIM model D parameter values (1.3±0.4 vs. 1.7±0.7 µm2/ms, p=0.14).

Fig. 2 depicts a representative example of an enhanced patient. The bright signal in the DW-MRI image (Fig. 2 A) is represented as a dark region in the ADC map (Fig. 2 B). The IVIM parametric maps (Fig. 2 C–E) show low fast-diffusion component and slow-diffusion component similar to the ADC value. Similarly, the plot of the signal decay and the estimated models (Fig. 2 F) show that the fast diffusion component has a very small influence on the signal decay.

Fig. 2.

Representative example of an enhanced patient. (A) the DW-MRI image (b-value=600 s/mm2) with bright region in the abnormal ileum (yellow arrow); (B) the ADC0-600 map presents restricted diffusion (dark region) in the abnormal ileum; (C) the IVIM-D map shows similar value to the ADC0-600; (D)–(E) the IVIM-D* and IVIM-f maps, and; (F) the signal decay plot shows almost no fast-decay compartment.

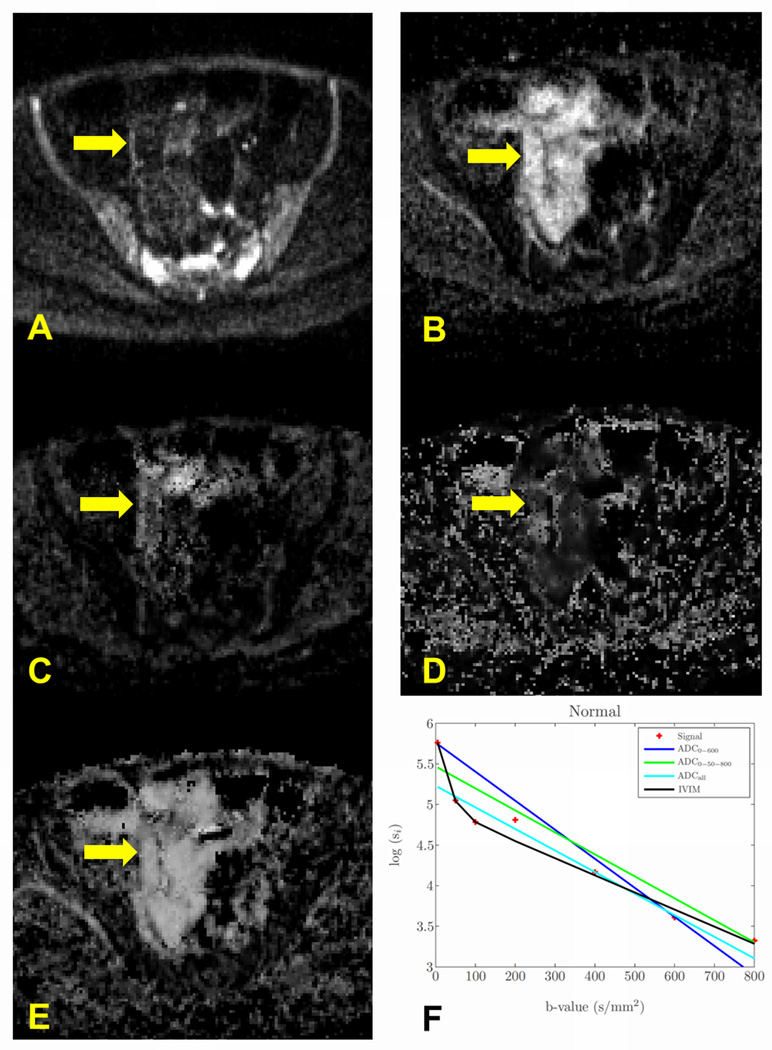

Fig. 3 depicts a representative example of a non-enhanced patient. The dark signal in the DW-MRI image (Fig. 3 A) is represented as a bright region in the ADC map (Fig. 3 B). However, the IVIM parametric maps show a large fast diffusion component and lower D value compared to the ADC (Fig. 3 C–E). Similarly, the plot of the signal decay and the estimated models (Fig. 3 F) show that the fast diffusion component has a large influence on the signal decay.

Fig. 3.

Representative example of a nonenhanced patient. (A) the DW-MRI image (b-value=600 s/mm2) with normal region in the ileum (yellow arrow); (B) the ADC0-600 map presents normal diffusion (bright region) in the ileum; (C) the IVIM-D map shows, however, much lower value as compared to the ADC0-600; (D) – (E) the IVIM-D* and IVIM-f maps show high values of the fast diffusion components, and; (F) the signal decay plot shows that most of the signal decay is associated with the fast diffusion component rather than with the slow diffusion component.

Fig. 4 presents the box-plot representation of the distributions of the quantitative DW-MRI parameters among the enhancing and non-enhancing groups. ADC values are higher than the slow diffusion compartment values that are produced by the IVIM model (D). Moreover, the difference in ADC measurements between the enhancing and non-enhancing group is associated with the fast diffusion decay changes (i.e. f) rather than by changes in the slow diffusion compartment (D).

Fig. 4.

Box-plot representation of the DW-MRI parameters values distributions for non-enhancing and enhancing ileal segments. The overall diffusion variations between the enhancing and non-enhancing ileal segments as measured by the ADC (A–C) are eliminated when calculating slow diffusion measurements using the IVIM model (D). The variations in the fast diffusion components (E–F) are the actual contributors to the overall diffusion variation as observed in the ADC model.

DISCUSSION

DW-MRI analysis of CD patients with the ADC parameter as a measure of overall diffusivity of the tissue has been observed to reflect lower overall diffusivity in inflamed ileal segments of Crohn’s patients. Oto et al. (8) used ADC values calculated from two DW-MRI images with b-value=0,600 s/mm2 to separate between abnormal and normal ileum segments. They reported a significantly lower ADC values (1.98±0.55 vs. 3.11±0.56 µm2/ms, p<0.001) in the abnormal ileum segments.

Kiryu et al. (6) compared ADC values calculated with b-values=0,50,800 s/mm2 between abnormal and normal ileum segments. They reported significantly lower ADC values in the abnormal segments (1.57±0.44 vs. 2.38±0.58, µm2/ms, p<0.0001).

Mono-exponential ADC analysis of the DW-MRI data obtained from our study cohort yielded similar results by using the same b-values as in (8) and (6) for ADC calculations.

Nevertheless, the biological interpretation of the lower ADC in abnormal ileum segments remains uncertain (24). Oto et al. (8) hypothesized that both the inflamed lamina propria and submucosa of the small bowel and lymphoid aggregates (25) can narrow the extracellular space and contribute to restricted diffusion of water molecules in the bowel wall.

While the enhancement observed in MRE reflects the concentration of the contrast media in the extra-cellular space due to increased vascular permeability in CD patients, the DW-MRI signal decay is known to be sensitive to the Brownian motion of water molecules and to the bulk motion of intravascular molecules in the micro-capillaries (10–13).

Previous studies of DW-MRI in Crohn’s disease patients utilized the mono-exponential ADC model of DW-MRI signal decay were able to determine only overall diffusivity variations. Our DW-MRI signal decay analysis with the IVIM model demonstrated that the ADC values were significantly higher than the slow diffusion parameter of the IVIM model, reflecting the contribution of the fast diffusion component to the DW-MRI signal decay. The significantly higher differences between the ADC and the D values in the non-enhancing segments than in the enhancing segments and the strong correlation between the ADC measurements and the f parameter of the IVIM model demonstrate that the ADC variations between the two groups are caused by the fast diffusion component rather than by the slow diffusion component.

These results also indicate that the ileum’s ADC values of pediatric CD patients are sensitive to the b-values that were used to calculate the ADC. Therefore, special care should be taken when comparing ADC values of CD patients calculated with different choices of b-values.

Our group differences analysis shows that the overall diffusivity variations between the enhancing and non-enhancing groups as observed by utilizing mono-exponential ADC analysis is related to changes in the f values rather than to changes in the slow diffusion parameter D.

The significant reduction in the f parameter in the enhanced ileum segments observed in our study (0.27±0.2 vs. 0.59±0.26, p<0.003) suggests a reduction in the microvascular volume in these segments. Carr et al. (14) demonstrated a reduction in the microvascular volume in segmented Crohn’s disease by examining tissue samples from postoperative colectomy specimens in which the microvasculature had been perfused with barium sulphate suspension. Similarly, Hultén et al. (15) demonstrated a reduction in microvascular volume by means of an isotope washout technique.

The D* parameter is associated with the average blood velocity in the microcapillaries (10, 11). The higher D* values in the enhanced segments observed in our study (51.9±48.9 vs. 18.5±16.7 µm2/ms, p=0.03) suggests that the microvascular volume reduction is associated with increased blood velocity to supply the tissue.

Our study had several limitations. First, the study population was limited in the number of the patients and by their age range. As a result, our assessment of DW-MRI data was restricted to the ileum, which is more commonly affected than other bowel segments during the course of CD. Second, due to the intra-institutional nature of the study, we performed all the studies in the same 1.5T system (Magnetom Avanto, Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany). A more comprehensive study in a multi-institutional setting with DW-MRI data acquired at different field strengths and/or with different vendor systems should be conducted.

In conclusion, we observed fast and slow diffusion components in the DW-MRI signal of Crohn’s disease patients included in this study. The DW-MRI signal was better described by the IVIM model than by the mono-exponential ADC model. The previously observed lower ADC values in abnormal ileum segments, which have been replicated in our study, were found to be associated with the reduction in the fast diffusion fraction parameter (f) rather than with the slow diffusion component (D). Our group differences analysis show that enhanced ileum segments are characterized by lower f values and higher D* values compared to the non-enhanced segments. We did not find a significant difference in the D values between the enhanced and non-enhanced ileum segments.

Further study is required to determine the role of the fast diffusion component in DW-MRI signal of Crohn’s disease patients in characterizing the different disease stages.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: This investigation was supported in part by NIH grants R01 EB008015, R01 LM010033, R01 EB013248, P30 HD018655 and a research grant from Boston Children's Hospital Translational Research Program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Loftus CG, Loftus EV, Jr, Harmsen WS, et al. Update on the incidence and prevalence of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940–2000. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:254–261. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herrinton LJ, Liu L, Lewis JD, Griffin PM, Allison J. Incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in a Northern California managed care organization, 1996–2002. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1998–2006. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirk GR, Clements WD. Crohn's disease and colorectal malignancy. Int J Clin Pract. 1999;53:314–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis JD. The utility of biomarkers in the diagnosis and therapy of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1817–1826. e1812. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.11.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stejskal EO, Tanner JE. Spin diffusion measurements: spin-echo in the presence of a time dependent field gradient. J Chem Phys. 1965;42:288–292. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiryu S, Dodanuki K, Takao H, et al. Free-breathing diffusion-weighted imaging for the assessment of inflammatory activity in Crohn's disease. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;29:880–886. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oto A, Zhu F, Kulkarni K, Karczmar GS, Turner JR, Rubin D. Evaluation of diffusion-weighted MR imaging for detection of bowel inflammation in patients with Crohn's disease. Acad Radiol. 2009;16:597–603. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oto A, Kayhan A, Williams JT, Fan X, Yun L, Arkani S, Rubin DT. Active Crohn's Disease in the small bowel: Evaluation by diffusion weighted imaging and quantitative dynamic contrast enhanced MR imaging. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2011;33:615–624. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oussalah A, Laurent V, Bruot O, et al. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance without bowel preparation for detecting colonic inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2010;59:1056–1065. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.197665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le Bihan D. Intravoxel incoherent motion perfusion MR imaging: a wake-up call. Radiology. 2008;249:748–752. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2493081301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le Bihan D, Breton E, Lallemand D, Aubin ML, Vignaud J, Laval-Jeantet M. Separation of diffusion and perfusion in intravoxel incoherent motion MR imaging. Radiology. 1988;168:497–505. doi: 10.1148/radiology.168.2.3393671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koh DM, Collins DJ, Orton MR. Intravoxel incoherent motion in body diffusion-weighted MRI: reality and challenges. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:1351–1361. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.5515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lemke A, Laun FB, Simon D, Stieltjes B, Schad LR. An in vivo verification of the intravoxel incoherent motion effect in diffusion-weighted imaging of the abdomen. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64:1580–1585. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carr ND, Pullan BR, Schofield PF. Microvascular studies in non-specific inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1986;27:542–549. doi: 10.1136/gut.27.5.542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hulten L, Lindhagen J, Lundgren O, Fasth S, Ahren C. Regional intestinal blood flow in ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1977;72:388–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thornton M, Solomon MJ. Crohn's disease: in defense of a microvascular aetiology. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2002;17:287–297. doi: 10.1007/s00384-002-0408-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conturo TE, McKinstry RC, Akbudak E, Robinson BH. Encoding of anisotropic diffusion with tetrahedral gradients: a general mathematical diffusion formalism and experimental results. Magn Reson Med. 1996;35:399–412. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910350319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mulkern RV, Vajapeyam S, Robertson RL, Caruso PA, Rivkin MJ, Maier SE. Biexponential apparent diffusion coefficient parametrization in adult vs newborn brain. Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;19:659–668. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(01)00383-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yushkevich PA, Piven J, Hazlett HC, et al. User-guided 3D active contour segmentation of anatomical structures: significantly improved efficiency and reliability. NeuroImage. 2006;31:1116–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freiman M, Voss SD, Mulkern RV, Perez-Rossello JM, Warfield SK. Quantitative body DW-MRI biomarkers uncertainty estimation using Unscented Wild-bootstrap. Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv. 2011;14(Pt 2):73–80. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-23629-7_10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chandarana H, Lee VS, Hecht E, Taouli B, Sigmund EE. Comparison of biexponential and monoexponential model of diffusion weighted imaging in evaluation of renal lesions: preliminary experience. Invest Radiol. 2011;46:285–291. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181ffc485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. Automatic Control, IEEE Transactions on. 1974;19:716–723. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burnham K, Anderson D. Multimodel inference: understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Sociological Methods and Research. 2004;33:261–304. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panes J, Ricart E, Rimola J. New MRI modalities for assessment of inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2010;59:1308–1309. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.214197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riddell RH. Kirsner JB. Inflammatory bowel disease. 5th ed. Philadelphia,PA: WB Saunders; 2000. Pathology of idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease; pp. 427–452. [Google Scholar]