Abstract

Objective To determine whether familial risk of cancer is limited to early onset cases.

Design Nationwide prospective cohort study.

Setting Nationwide Swedish Family-Cancer Database.

Participants All Swedes born after 1931 and their biological parents, totalling >12.2 million individuals, including >1.1 million cases of first primary cancer.

Main outcome measures Familial risks of the concordant cancers by age at diagnosis.

Results The highest familial risk was seen for offspring whose parents were diagnosed at an early age. Familial risks were significantly increased for colorectal, lung, breast, prostate, and urinary bladder cancer and melanoma, skin squamous cell carcinoma, and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, even when parents were diagnosed at age 70-79 or 80-89. When parents were diagnosed at more advanced ages (≥90), the risk of concordant cancer in offspring was still significantly increased for skin squamous cell carcinoma (hazard ratio 1.9, 95% confidence interval 1.4 to 2.7), colorectal (1.6, 1.2 to 2.0), breast (1.3, 1.0 to 1.6), and prostate cancer (1.3, 1.1 to 1.6). For offspring with a cancer diagnosed at ages 60-76 whose parents were affected at age <50, familial risks were not significantly increased for nearly all cancers.

Conclusion Though the highest familial risks of cancer are seen in offspring whose parents received a diagnosis of a concordant cancer at earlier ages, increased risks exist even in cancers of advanced ages. Familial cancers might not be early onset in people whose family members were affected at older ages and so familial cancers might have distinct early and late onset components.

Introduction

Early onset cancers tend to have a more pronounced hereditary component than late onset cancers, and cancers in individuals with a family history occur earlier than those without family history.1 2 Although having a family history of a cancer is not modifiable, it is possible that a predisposition to the disease, which is represented by a positive family history, is modifiable through alteration of as yet incompletely understood environmental factors or by adequate intervention strategies. A better understanding of family history within the population is a key factor to improve our understanding of cancer aetiology and to provide appropriate advice for clinical counselling and screening.

Though the greatest risk factor for developing cancer is ageing, little is known about whether any familial component exists in cancers of very old age. As the current population ages, and as more people are living longer, the number of new cancer diagnoses in older people is expected to rise. For unbiased estimates of familial risk, it is important that all data on cancers are medically verified and that family structures are derived from registered sources. Such data, however, have been available from only a few sources, but even those have provided no estimates of familial risk for an advanced age at diagnosis (≥90).1 3 4 5 The median age of diagnosis in the Swedish Cancer Registry is a little over 70 (71 in men and 70 in women) but most of the literature assessing familial risks focuses on populations younger than this age.

We used the unique nationwide Swedish Family-Cancer Database, in which family relationships and data on cancer are retrieved from registered sources of high quality, thus avoiding biases of the interview studies, where participants report cancers in their family members.6 7 We examined whether history of onset of cancer at old age in parents is still associated with an increased risk of familial cancer in the offspring.

Methods

The Swedish Family-Cancer Database was created in the 1990s by linking information from the multigeneration register, national censuses, Swedish Cancer Registry, and death notifications using individually unique national registration number.5 Data on family relationships were obtained from the multigeneration register, in which children born in Sweden in 1932 and later are registered with their biological parents as families. Thus, the individuals in the database can be divided into the offspring generation (individuals born after 1931) and the parental generation. In this nationwide cohort study, parents’ ages were not limited but offspring were limited to those aged 0-76. Because of some inaccuracies in determination of vital status in the first years of cancer registration (1958-61), we used cancer cases with a diagnosis in 1961-2008. Cancer registration in Sweden, which is based on compulsory reports of diagnosed cases, is considered to be close to 90%.8 Basal cell carcinoma of skin is not registered in Sweden and therefore skin cancer in this paper refers to squamous cell carcinoma of skin. We used ICD-7 (international classification of diseases, seventh revision). Additional linkage was carried out to the national census data to obtain socioeconomic background data. Linkage to the hospital discharge register provided information on admissions to hospital for obesity, alcohol consumption, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The 2010 update of the database includes over 12.2 million individuals and over 1.1 million cases of first primary tumours. We excluded individuals without identified parents and restricted this study to those offspring who had a known mother and father in the Swedish Family-Cancer Database (7 904 092 offspring and their biological parents). As our main theme was familial risk of cancer in advanced age, we restricted results to cancer sites with at least 50 cases in offspring with parental age at diagnosis of age ≥80.

We used Cox proportional hazard models to estimate hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals of risk of cancer in offspring whose parents were affected with a concordant cancer compared with those whose parents were not affected. Years of entering and leaving the study were used as underlining time variables.

Results of these analyses were also stratified by the age of offspring and parents at diagnosis of the concordant cancer to find out whether the risks of familial cancer exist if the cancer was diagnosed at an advanced age. In this study, by concordant cancer we mean the same type of cancer regardless of its histology. The follow-up was started for each offspring at birth, immigration date, or 1 January 1961, whichever came latest and it finished on the year of diagnosis of first primary cancer, death, emigration, or the closing date of the study (31 December 2008), whichever came earlier (mean follow-up 30 years). All hazard ratios were adjusted for age, sex, period (continuous, years of entering and leaving the study, 1961-2008), socioeconomic status (farmer, manual workers, low to middle income office worker, high income office worker/professional, company owner (except farmer), or other/unspecified), residential area (large cities, South Sweden, North Sweden, or unspecified), parents’ age at the start and end of follow-up, and admission to hospital for obesity, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (as a proxy for smoking), and alcohol consumption.

Results

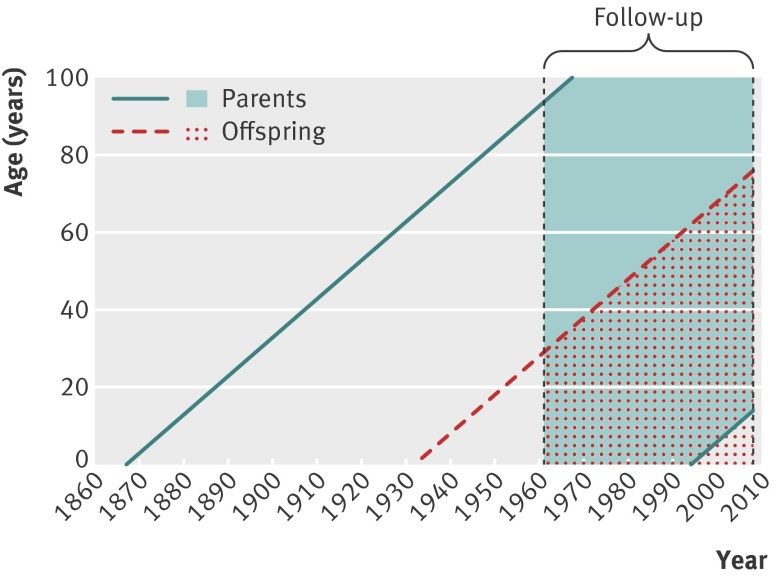

Table 1 shows the total numbers of offspring with cancer and the numbers of familial cases in the offspring generation stratified by parents’ age at diagnosis. Depending on cancer site, some 35-81% of familial cancers in parents were diagnosed after the age of 69 (colorectal: 59% (1528/2596), lung: 56% (621/1113), breast 41% (2275/5526), prostate: 75% (4146/5555, urinary bladder: 62% (270/437), and skin cancer: 81% (268/330), melanoma: 35% (241/687), and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: 54% (111/205)). There were 3 471 917 mothers available in our sample for this study with mean birth year of 1944 (SD 22.2; median 1946; range: 1880-1994) and 3 518 986 fathers with mean birth year of 1941 (SD 22.7; median 1944; range 1867-1993). The figure shows a schematic representation of demographics.[f1] Parents were born from 1867 to 1993 and offspring were born from 1932 to 2008. In this study, follow-up was started from 1961 and ended at 2008 as described before.

Table 1.

Total number of cases of cancer in offspring (including familial cases) by age of offspring at diagnosis and number of familial cancer cases in which parents were affected with concordant cancer

| Cancer and age (years) at diagnosis in offspring | No of cases in offspring | No of familial cases by parental age (years) at diagnosis* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <40 | 40-49 | 50-59 | 60-69 | 70-79 | 80-89 | ≥90 | ||

| Colorectal | ||||||||

| 0-76 | 24 121 | 28 | 94 | 292 | 654 | 890 | 572 | 66 |

| <60 | 12 972 | 28 | 87 | 212 | 387 | 523 | 310 | 26 |

| 60-76 | 11 149 | 0 | 7 | 80 | 267 | 367 | 262 | 40 |

| Lung | ||||||||

| 0-76 | 16 545 | 2 | 10 | 138 | 342 | 456 | 157 | 8 |

| <60 | 8198 | 1 | 6 | 99 | 204 | 252 | 76 | 4 |

| 60-76 | 8347 | 1 | 4 | 39 | 138 | 204 | 81 | 4 |

| Breast | ||||||||

| 0-76 | 58 505 | 120 | 575 | 1084 | 1472 | 1384 | 787 | 104 |

| <60 | 43 655 | 119 | 522 | 926 | 1212 | 1064 | 547 | 72 |

| 60-76 | 14 850 | 1 | 53 | 158 | 260 | 320 | 240 | 32 |

| Prostate | ||||||||

| 0-76 | 36 878 | 0 | 7 | 168 | 1234 | 2580 | 1465 | 101 |

| <60 | 9837 | 0 | 5 | 94 | 626 | 1121 | 516 | 27 |

| 60-76 | 27 041 | 0 | 2 | 74 | 608 | 1459 | 949 | 74 |

| Urinary bladder | ||||||||

| 0-76 | 9662 | 1 | 10 | 42 | 114 | 158 | 101 | 11 |

| <60 | 5156 | 1 | 8 | 25 | 62 | 81 | 55 | 6 |

| 60-76 | 4506 | 0 | 2 | 17 | 52 | 77 | 46 | 5 |

| Melanoma | ||||||||

| 0-76 | 20 804 | 45 | 90 | 140 | 171 | 148 | 88 | 5 |

| <60 | 16 844 | 45 | 87 | 128 | 156 | 118 | 68 | 3 |

| 60-76 | 3960 | 0 | 3 | 12 | 15 | 30 | 20 | 2 |

| Skin squamous cell carcinoma | ||||||||

| 0-76 | 6998 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 52 | 107 | 125 | 36 |

| <60 | 3633 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 31 | 61 | 50 | 14 |

| 60-76 | 3365 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 21 | 46 | 75 | 22 |

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | ||||||||

| 0-76 | 9687 | 2 | 3 | 26 | 63 | 59 | 49 | 3 |

| <60 | 6736 | 2 | 2 | 22 | 48 | 37 | 32 | 1 |

| 60-76 | 2951 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 15 | 22 | 17 | 2 |

*If both parents were affected with concordant cancer, minimum age at onset in either parent was used.

Study population and follow-up. Shaded area represents parent generation; dotted shaded area represents offspring generation

Table 2 shows the risks of concordant cancer in offspring, stratified by offspring and parental age at diagnosis. The highest familial risk was seen in patients whose parents received a diagnosis at earlier ages. Even when parents were affected in old age (≥70) the risks of concordant cancer in their offspring were significantly higher than those whose parents were not affected with the same cancer. For instance, if parents were affected at age 80-89, the hazard ratios were significantly increased in offspring for melanoma (2.3, 95% confidence interval 1.9 to 2.8), skin squamous cell carcinoma (2.0, 1.7 to 2.4), prostate (1.9, 1.8 to 2.0), non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (1.7, 1.3 to 2.3), urinary bladder (1.9, 1.5 to 2.3), lung (1.8, 1.6 to 2.1), breast (1.6, 1.5 to 1.7), and colorectal cancer (1.6, 1.4 to 1.7). In those whose parents were diagnosed at age ≥90, the hazard ratios were still significantly increased for skin squamous cell carcinoma (1.9, 1.4 to 2.7), colorectal (1.6, 1.2 to 2.0), breast (1.3, 1.0 to 1.6), and prostate cancer (1.3, (1.1 to 1.6) (table 2).

Table 2.

Risk of cancer in offspring whose parents were affected with concordant cancer compared with offspring without affected parents. Figures are hazard ratios* (95% confidence interval)

| Cancer and age (years) at diagnosis in offspring | Parental age (years) at diagnosis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <40 | 40-49 | 50-59 | 60-69 | 70-79 | 80-89 | ≥90 | All ages | |

| Colorectal | ||||||||

| 0-76 | 8.3 (5.7 to 12.1) | 4.4 (3.6 to 5.4) | 2.8 (2.5 to 3.2) | 2.1 (2.0 to 2.3) | 1.7 (1.6 to 1.8) | 1.6 (1.4 to 1.7) | 1.6 (1.2 to 2.0) | 1.9 (1.8 to 2.0) |

| <60 | 9.9 (6.8 to 14.4) | 5.5 (4.4 to 6.8) | 3.4 (2.9 to 3.9) | 2.3 (2.0 to 2.5) | 1.9 (1.7 to 2.0) | 1.7 (1.5 to 1.9) | 1.3 (0.9 to 2.0) | — |

| 60-76 | — | 1.2 (0.6 to 2.5) | 1.7 (1.4 to 2.2) | 1.8 (1.6 to 2.1) | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.6) | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.7) | 1.9 (1.3 to 2.6) | — |

| Lung | ||||||||

| 0-76 | 3.2 (0.8 to 12.7) | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.4) | 2.7 (2.3 to 3.2) | 2.0 (1.8 to 2.3) | 2.1 (1.9 to 2.3) | 1.8 (1.6 to 2.1) | 1.4 (0.7 to 2.8) | 2.1 (1.9 to 2.2) |

| <60 | — | 1.1 (0.5 to 2.4) | 3.2 (2.6 to 3.9) | 2.3 (2.0 to 2.7) | 2.2 (1.9 to 2.5) | 1.8 (1.4 to 2.3) | 1.8 (0.7 to 4.9) | — |

| 60-76 | — | 1.3 (0.4 to 4.0) | 1.5 (1.1 to 2.1) | 1.4 (1.2 to 1.7) | 1.8 (1.5 to 2.0) | 1.8 (1.4 to 2.2) | 1.5 (0.6 to 4.1) | — |

| Breast | ||||||||

| 0-76 | 4.7 (3.9 to 5.7) | 2.9 (2.7 to 3.2) | 2.5 (2.3 to 2.6) | 2.0 (1.9 to 2.1) | 1.8 (1.7 to 1.9) | 1.6 (1.5 to 1.7) | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.6) | 2.0 (1.9 to 2.1) |

| <60 | 5.2 (4.4 to 6.3) | 3.0 (2.7 to 3.3) | 2.5 (2.3 to 2.7) | 2.1 (2.0 to 2.2) | 1.8 (1.7 to 1.9) | 1.5 (1.4 to 1.7) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.7) | — |

| 60-76 | — | 1.8 (1.3 to 2.3) | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.8) | 1.4 (1.3 to 1.6) | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.7) | 1.6 (1.4 to 1.8) | 1.4 (1.0 to 2.1) | — |

| Prostate | ||||||||

| 0-76 | — | 5.2 (2.5 to 10.9) | 3.3 (2.8 to 3.8) | 2.9 (2.8 to 3.1) | 2.4 (2.3 to 2.4) | 1.9 (1.8 to 2.0) | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.6) | 2.3 (2.2 to 2.4) |

| <60 | — | 7.8 (3.2 to 18.7) | 4.9 (3.9 to 6.0) | 4.1 (3.8 to 4.5) | 3.0 (2.8 to 3.3) | 2.2 (2.0 to 2.4) | 1.7 (1.1 to 2.6) | — |

| 60-76 | — | 3.8 (1.0 to 15.2) | 2.3 (1.8 to 2.8) | 2.1 (2.0 to 2.3) | 1.9 (1.8 to 2.0) | 1.8 (1.7 to 1.9) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.8) | — |

| Urinary bladder | ||||||||

| 0-76 | — | 3.8 (2.1 to 7.1) | 2.3 (1.7 to 3.2) | 2.2 (1.8 to 2.6) | 1.8 (1.6 to 2.1) | 1.9 (1.5 to 2.3) | 1.7 (1.0 to 3.1) | 2.0 (1.8 to 2.2) |

| <60 | — | 4.1 (2.0 to 8.1) | 2.3 (1.6 to 3.4) | 2.2 (1.7 to 2.8) | 1.7 (1.3 to 2.1) | 1.9 (1.5 to 2.5) | 2.1 (0.9 to 4.6) | — |

| 60-76 | — | 1.7 (1.0 to 3.0) | 2.1 (1.6 to 2.8) | 1.9 (1.5 to 2.4) | 1.7 (1.2 to 2.3) | 1.4 (0.5 to 3.7) | — | — |

| Melanoma | ||||||||

| 0-76 | 5.4 (4.1 to 7.2) | 4.5 (3.7 to 5.5) | 3.7 (3.2 to 4.4) | 2.9 (2.5 to 3.4) | 2.2 (1.9 to 2.6) | 2.3 (1.9 to 2.8) | 0.5 (0.2 to 1.5) | 2.9 (2.7 to 3.2) |

| <60 | 5.8 (4.3 to 7.7) | 4.7 (3.8 to 5.8) | 3.7 (3.1 to 4.5) | 3.0 (2.6 to 3.5) | 2.0 (1.6 to 2.4) | 2.2 (1.8 to 2.9) | 0.5 (0.1 to 1.9) | — |

| 60-76 | — | 2.2 (0.6 to 9.0) | 3.6 (2.0 to 6.4) | 2.0 (1.1 to 3.4) | 2.7 (1.8 to 3.9) | 2.0 (1.2 to 3.4) | 0.7 (0.1 to 4.8) | — |

| Skin squamous cell carcinoma | ||||||||

| 0-76 | — | 2.1 (0.5 to 8.4) | 1.8 (0.9 to 3.4) | 3.1 (2.3 to 4.1) | 2.4 (2.0 to 2.9) | 2.0 (1.7 to 2.4) | 1.9 (1.4 to 2.7) | 2.2 (2.0 to 2.5) |

| <60 | — | 2.9 (0.7 to 11.7) | 2.0 (0.9 to 4.4) | 3.3 (2.3 to 4.7) | 2.6 (2.0 to 3.3) | 1.5 (1.1 to 2.0) | 1.7 (1.0 to 2.9) | — |

| 60-76 | — | — | 1.4 (0.4 to 4.2) | 2.4 (1.5 to 3.9) | 2.2 (1.6 to 2.9) | 2.6 (2.0 to 3.3) | 2.3 (1.5 to 3.5) | — |

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | ||||||||

| 0-76 | 1.9 (0.5 to 7.5) | 0.8 (0.3 to 2.6) | 2.3 (1.5 to 3.3) | 2.3 (1.8 to 3.0) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.8) | 1.7 (1.3 to 2.3) | 0.9 (0.3 to 2.9) | 1.8 (1.5 to 2.0) |

| <60 | 2.0 (0.5 to 8.0) | 0.6 (0.2 to 2.5) | 2.4 (1.5 to 3.6) | 2.4 (1.8 to 3.1) | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.8) | 1.8 (1.2 to 2.5) | — | — |

| 60-76 | — | — | 1.4 (0.5 to 4.4) | 2.0 (1.2 to 3.4) | 1.6 (1.0 to 2.5) | 1.4 (0.8 to 2.5) | 1.6 (0.4 to 6.4) | — |

*Presented if at least two familial cases were available in that strata. Adjusted for age, sex, calendar period, geographical region, socioeconomic status of index cases as well as age at start and end of follow-up of parents; further adjustment for admission to hospital for obesity, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (as proxy for smoking), and alcohol consumption did not change results.

Table 2 also shows the familial hazard ratios by offspring age at diagnosis (<60 and 60-76). In offspring aged 60-76 at diagnosis, none of those with colorectal, prostate, urinary bladder, skin cancer, and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and melanoma had a parent affected at young age (<40) (table 1). We found no significantly increased risks for any of the cancers for offspring who received a diagnosis at older ages (60-76) whose parents were affected at young ages (<50), with the exception of breast cancer.

The absolute risks of familial cancers could be estimated based on the cumulative risks of cancers by age 75 in the Swedish population.9 The cumulative risk for colorectal cancer was 3.4%, thus a hazard ratio of 1.9 for familial colorectal cancer in offspring aged 0-76 (table 2) would be translated to a cumulative risk of 6.4%. The respective absolute risk for the other familial cancers when parents received a diagnosis at any age would be 5.0% for lung, 8.8% for breast, 30.1% for prostate, 2.8% for urinary bladder, 3.5% for skin squamous cell carcinoma, 4.6% for melanoma, and 1.6% for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (adjusted for the background cumulative risks of these cancers by age 75, which were 3.4% for colorectal, 2.4% for lung, 4.4% for breast, 13.1% for prostate, 1.4% for urinary bladder, 1.2% for skin cancer, 1.6% for melanoma, and 0.9% for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma).9

Discussion

Principal findings

While most studies on familial cancer emphasise the high risk of developing cancer among relatives of people who received a diagnosis of cancer at young ages, we found the presence of familial risks even in cancers of advanced ages, though the highest familial risk was seen in offspring affected at younger ages with parents who had also received a diagnosis at earlier ages. In nearly all sites, we found no significant familial risk for offspring aged 60-76 at diagnosis whose parents were affected at younger ages.

Strengths and weaknesses

The Swedish Family-Cancer Database is the largest of its kind in the world and risk estimates generated by these data are relatively precise. Bias in estimates of familial cancer, however, can result if population based registers fail to identify relatives as affected when disease occurs before the start of registration (that is, “left truncation” of family history). For common cancers, risk estimates from the Swedish multi-generational cohort do not generally seem to be biased by left truncation.10 To tackle the possible residual effect of truncation in age distribution of cases in parents and offspring, in addition to adjustment of our results for calendar period, we adjusted our results for parents’ age at the start and end of the follow-up and considered age of offspring in our calculation for familial risk of each cancer site. It might be misleading to present distributions for different offspring-parent cancers stratified by parental age at diagnosis as they are determined to some extent by the constraints in the age distribution of parents and offspring. Although the number of familial cases at young ages in the offspring generation in our data (with complete follow-up from birth onward), and in other studies, show that familial cases in very young age are rare, because of the structure of our data the number of familial cases with parent’s age <40 at diagnosis is slightly underestimated. Another factor to consider is underascertainment bias in elderly people in our database,11 which could reflect decreased screening and medical surveillance rather than decreased risk. Exposures to environmental and lifestyle risk factors might also differ between younger and older people. Any underascertainment for elderly people, however, should be non-differential with regard to occurrence of concordant cancer in the offspring, though this could have diluted our results for those offspring whose parents were diagnosed at very advanced ages.

In addition, accurate estimates of risk of disease in an ageing population require adjustment for competing risks of mortality12 because competing risks of death from other causes are high in older populations. Competing risks of other diseases such as cardiovascular disease could potentially influence our results if they had a familial association with cancers. Although cardiovascular disease is also familial,13 neither incidence nor mortality in common types of cancer show familial association with common diseases, such as coronary heart disease or stroke (unpublished results from the Swedish family dataset). Furthermore, any underascertainment or competing risk for elderly patients should be non-differential with regard to occurrence of concordant cancer in the offspring.

Regional differences were probably reconciled by adjustment for geography. Similarly, the adjustment for socioeconomic factors should help to control for factors related to lifestyle. We had data on obesity and alcohol consumption and also chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (as a proxy for smoking) based on admission to hospital for these conditions, which would of course include only extreme cases. Therefore, further studies with more complete information on these confounding factors are warranted. The data on families and cancers have a complete coverage, apart from some groups of dead offspring, which affects those born in the 1930s and who died before 1991. This small group of offspring with missing links to parents has a negligible effect on the estimates of familial risk.14 The sporadic reference population probably contained smaller families than the familial population; based on our previous study, however, family size does not influence familial risk.15

Comparisons with other studies and implications of findings

If cancer diagnosis in a very old parent is a predictor of an increased risk of the same cancer in their offspring, the offspring should benefit from knowing this risk by avoiding known modifiable risk factors for that particular cancer and consider other preventive measures. In our study population, 35-81% of familial cancers in parents occurred at ages over 69. A nested case-control study of the familial risk based on a cohort of around 700 000 individuals reported that both the proportion and the number of all cancers attributable to family history peaked at 32% in the age group 65-84 (probably because of active screening) and remained high in the group aged 85 or over.16

Is age at onset of familial cancer genetically determined?

The risk of developing familial cancer has been proposed to depend both on an index person’s own age and on the age which their relatives received a diagnosis of a concordant cancer. Individual studies, however, have not been large enough to reliably characterise this dual dependence on age. We provided the familial risk for cancer in offspring aged <60 and 60-76 whose parents were affected with a concordant cancer by the parent’s age at diagnosis (table 2). In offspring aged 60 or more at diagnosis, none of those with colorectal, prostate, urinary bladder, and skin cancers, and melanoma and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma had a parent affected at young age (<40). The higher risk of familial cancer for offspring whose parents were affected at young ages disappeared in this subgroup of offspring. This suggests that familial cancers are early onset mainly in those individuals whose family members are affected at early ages and not in those whose family members were affected at older ages.

Environmental component of family history

Attempts to reveal familial risks by non-genetic factors by comparing cancer risks between spouses or among siblings by age differences have in principle only incriminated tobacco smoking, contributing some 25-30% of the familial risk of lung cancer. Therefore, familial risks have a largely genetic basis.17 Shared lifestyle among family members seems to explain only a small proportion of familial susceptibility to cancer. Because lifestyles are likely to differ more between parents and offspring than between spouses, familial cancer risks between parents and offspring are even more likely to be caused by heritable than by environmental effects.17 Prenatal, postnatal, and childhood environmental/lifestyle factors, however, can contribute to familial cancer risks between parents and offspring.

Much epidemiological evidence indicates that cancer is mainly an environmental disease.18 19 20 It has become clear that being overweight and lack of physical activity increase risk.21 Moreover, the risks at the population level caused by various infections have become better understood, and known infections have been estimated to account for 15% of cancer worldwide.22 23 Research on diet and cancer found some beneficial and harmful foods and nutrients in regard to risk.24 25 A recent comprehensive review estimated the proportion of cancers in the United Kingdom that were the result of exposure to major lifestyle, dietary, and environmental risk factors such as tobacco, alcohol, diet, overweight, lack of physical exercise, occupation, infections, radiation, use of hormones, and reproductive history.26 This study suggested that 45% of all cancers in men and 40% in women could be prevented by the avoidance of known modifiable risk factors.

Our study suggests that the bulk of familial cancers of advanced ages are included in the moderate risk category, which does demand increased clinical surveillance and further investigations to identify factors that affect cancer susceptibility at advanced ages. Finding the causes of even a modest proportion of familial aggregation of a disease could be a major step toward understanding the causes of the disease itself. Gene mutations associated with high personal risks are typically so rare that they explain only a small proportion of familial aggregation.27 For the known high risk susceptibility genes, our growing understanding has led to genetic tests and to medical and surgical intervention that can add years to the lives of gene mutation carriers. We do not yet know whether improved understanding of intermediate risk and modest risk susceptibility genes will lead to similar medical utility.28 Furthermore, studying the differences between familial cancer cases of advanced age and those familial cases that occur at early age might show a difference in genes and environmental and life styles factors that modify the genetic susceptibility.

Conclusions

Our study has shown the existence of a familial component, even in cancers of advanced ages, though the highest familial risk was seen in patients with a parent diagnosed at earlier ages. Familial cancers might be early onset mainly in those individuals whose family members were affected at early ages. As cancer diagnosis even in a very old parent can be predictor of higher risk of the same cancer in their offspring, offspring might benefit from knowing this risk by avoiding known modifiable risk factors for that particular cancer (such as smoking) and consider other preventive measures. The present study provides novel and useful information for clinical counselling and cancer genetics. Further studies with more complete information on obesity, alcohol consumption, smoking, and other residual possible confounders are warranted.

What is already known on this topic

Early onset cancer cases tend to have a more pronounced hereditary component than late onset cases

Cancers in individuals with a family history occur earlier than in sporadic patients

Despite the fact that the greatest risk factor for developing cancer is ageing, little is known about whether any familial component exists in cancers of very old age

What this study adds

Familial risk of cancers exists even in cancers of advanced ages, though the highest familial risk is in affected people whose parents received a diagnosis at earlier ages

Familial cancers might not be of early onset in those whose family members were affected at older ages

Family members might benefit from knowing this risk by avoiding known modifiable risks factor for that particular cancer and considering other preventive measures

Contributors: EK and KH planned and designed the study, interpreted the results, and wrote the paper. All authors approved the final manuscript. KS provided the study materials. EK and MF analysed the data. KH is guarantor.

Funding: This study was supported by the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research and the German Cancer Aid (Deutsche Krebshilfe).

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Lund regional ethics committee. Consent was not obtained but the presented data are anonymised and there is no risk of identification.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2012;345:e8076

References

- 1.Goldgar DE, Easton DF, Cannon-Albright LA, Skolnick MH. Systematic population-based assessment of cancer risk in first-degree relatives of cancer probands. J Natl Cancer Inst 1994;86:1600-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandt A, Bermejo JL, Sundquist J, Hemminki K. Age of onset in familial cancer. Ann Oncol 2008;19:2084-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amundadottir LT, Thorvaldsson S, Gudbjartsson DF, Sulem P, Kristjansson K, Arnason S, et al. Cancer as a complex phenotype: pattern of cancer distribution within and beyond the nuclear family. PLoS Med 2004;1:e65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hemminki K, Ji J, Brandt A, Mousavi SM, Sundquist J. The Swedish Family-Cancer Database 2009: prospects for histology-specific and immigrant studies. Int J Cancer 2009;126:2259-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hemminki K, Li X, Plna K, Granstrom C, Vaittinen P. The nation-wide Swedish family-cancer database—updated structure and familial rates. Acta Oncol 2001;40:772-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang ET, Smedby KE, Hjalgrim H, Glimelius B, Adami HO. Reliability of self-reported family history of cancer in a large case-control study of lymphoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006;98:61-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hampel H, Sweet K, Westman JA, Offit K, Eng C. Referral for cancer genetics consultation: a review and compilation of risk assessment criteria. J Med Genet 2004;41:81-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cancer incidence in Sweden 2006. National Board of Health and Welfare, Centre for Epidemiology, 2007. www.socialstyrelsen.se.

- 9.Engholm GFJ, Christensen N, Johannesen TB, Klint Å, Køtlum JE, Milter MC, et al. NORDCAN: cancer incidence, mortality, prevalence and survival in the Nordic Countries, 2012. Association of the Nordic Cancer Registries. Danish Cancer Society, www.ancr.nu.

- 10.Leu M, Reilly M, Czene K. Evaluation of bias in familial risk estimates: a study of common cancers using Swedish population-based registers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:1318-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barlow L, Westergren K, Holmberg L, Talback M. The completeness of the Swedish Cancer Register: a sample survey for year 1998. Acta Oncol 2009;48:27-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Driver JA, Djousse L, Logroscino G, Gaziano JM, Kurth T. Incidence of cardiovascular disease and cancer in advanced age: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2008;337:a2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sundquist K, Winkleby M, Li X, Ji J, Hemminki K, Sundquist J. Familial transmission of coronary heart disease: a cohort study of 80,214 Swedish adoptees linked to their biological and adoptive parents. Am Heart J 2011;162:317-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hemminki K, Li X. Familial risk of cancer by site and histopathology. Int J Cancer 2003;103:105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemminki K, Mutanen P. Birth order, family size, and the risk of cancer in young and middle-aged adults. Br J Cancer 2001;84:1466-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kerber RA, O’Brien E. A cohort study of cancer risk in relation to family histories of cancer in the Utah population database. Cancer 2005;103:1906-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hemminki K, Jiang Y. Life style and cancer: effect of divorce. Int J Cancer 2002;98:316-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doll R, Peto R. The causes of cancer: quantitative estimates of avoidable risks of cancer in the United States today. J Natl Cancer Inst 1981;66:1191-308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lichtenstein P, Holm NV, Verkasalo PK, Iliadou A, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M, et al. Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer—analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. N Engl J Med 2000;343:78-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peto J. Cancer epidemiology in the last century and the next decade. Nature 2001;411:390-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergstrom A, Pisani P, Tenet V, Wolk A, Adami HO. Overweight as an avoidable cause of cancer in Europe. Int J Cancer 2001;91:421-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pisani P, Parkin DM, Munoz N, Ferlay J. Cancer and infection: estimates of the attributable fraction in 1990. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1997;6:387-400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zur Hausen H. Viruses in human cancers. Eur J Cancer 1999;35:1878-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parkin DM. 5. Cancers attributable to dietary factors in the UK in 2010. II. Meat consumption. Br J Cancer 2011;105(suppl 2):S24-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parkin DM, Boyd L. 6. Cancers attributable to dietary factors in the UK in 2010. III. Low consumption of fibre. Br J Cancer 2011;105(suppl 2):S27-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parkin DM. 1. The fraction of cancer attributable to lifestyle and environmental factors in the UK in 2010. Br J Cancer 2011;105(suppl 2):S2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hopper JL. Disease-specific prospective family study cohorts enriched for familial risk. Epidemiol Perspect Innov 2011;8:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hemminki K, Granstrom C, Chen B. The Swedish family-cancer database: update, application to colorectal cancer and clinical relevance. Hered Cancer Clin Pract 2005;3:7-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]