Abstract

It was hypothesized that affect-amplifying individuals would be more reactive to affective events in daily life. Affect amplification was quantified in terms of overestimating the font size of positive and negative, relative to neutral, words in a basic perception task. Subsequently, the same (N = 70) individuals completed a daily diary protocol in which they reported on levels of daily stressors, provocations, and social support as well as six emotion-related outcomes for 14 consecutive days. Individual differences in affect amplification moderated reactivity to daily affective events in all such analyses. For example, daily stressor levels predicted cognitive failures at high, but not low, levels of affect amplification. Affect amplification, then, appears to have widespread utility in understanding individual differences in emotional reactivity.

Keywords: Individual Differences, Affect, Perception, Reactivity, Daily Life

A quick mental survey of one’s friends or acquaintances reveals an important difference between them. On the one hand, there are seemingly stoic people for whom emotional events (e.g., having a paper accepted or rejected) barely seem to cause a reaction. On the other hand, there are others whose emotional state seems to vary considerably by recent emotion-related events that have occurred (e.g., a recent argument or a positive relationship experience). Such differences between people can be termed emotional reactivity. The scientific literature has confirmed such differences between people in both laboratory protocols in which emotional inductions have been used (e.g., Larsen, Diener, & Cropanzano, 1987) and in terms of greater contingencies between daily levels of emotional events and reactions to them (e.g., Bolger, Davis, & Rafaeli, 2003). Variability in emotional reactivity across persons, though, is primarily a descriptive phenomenon. That is, we know that people differ in emotional reactivity, but why? The present study tests a theory-informed, though novel, predictor termed affect amplification.

Affect Amplification

We begin our analysis with the concept of salience. Salience, broadly speaking, is a property referring to information that “stands out” or is, in other words, prominent or distinctive. There are thought to be multiple factors that render information more salient, including goal-relevance and accessibility (Higgins, 1996), but also visual factors such as greater figure-ground contrast (Reber, Winkielman, & Schwarz, 1998). In this sense, salience is a latent concept rather than one that is reducible to any specific property. Regardless, though, the social cognition literature has emphasized the idea that salient information should exert a disproportional influence on social judgments, behavior, and – most relevant to our analysis – emotional reactions (Fiske & Taylor, 1991). The salience concept, for example, is often invoked to explain why detailed information concerning a specific person who died as a result of an activity (e.g., traveling on a plane) can often overwhelm more objective probability statistics related to the likelihood of dying in this manner (Slovic & Peters, 2006).

Because of their greater goal-relevance (Lazarus, 1991), affective events may be one important input to salience. Indeed, the brain seems to devote greater processing resources to affective than neutral events, regardless of whether they are positive or negative (Berridge, 2007; Peyk, Schupp, Elbert, & Junghofer, 2008; Schupp et al., 2000). Of more importance to our investigation are indications that affect may bias size perceptions. Bruner and Goodman (1947) found that children overestimated the size of monetary coins (which have affective value) relative to cardboard disks of the same size (for a conceptual replication, see Lambert, Solomon, & Watson, 1949). Bruner and Postman (1948) printed positive (e.g., a dollar sign), neutral (e.g., a square), or negative (e.g., a Nazi sign) symbols on plastic disks and found that the disks were estimated to be larger in size in the two affective conditions relative to the neutral condition (for a conceptual replication, see Klein, Schlesinger, & Meister, 1951).

Such “New Look” ideas concerning affective inputs to perception remained dormant for many years, but they have been resurrected recently. On the appetitive side, Veltkamp, Aarts, and Custers (2008) found that the volume of a glass of water was seen to be higher among thirsty individuals and Topolinski and Pereira (2012) found that hungry participants estimated the size of food stimuli as larger in an oral perception task. On the aversive side, van Ulzen, Semin, Oudejans, and Beek (2008) found that circles seemed larger when a negative relative to neutral picture was placed in them and Riskind (e.g., Riskind & Williams, 2005) has long suggested that phobic stimuli such as spiders possess perceptual “loomingness” among phobic individuals. These findings involve the manipulation of motivational states, special populations, or somewhat involved methods. In the present study, we used a simpler paradigm in which affective and neutral words were presented and participants estimated their font size. On the basis of the idea that affect is salient, we thought it likely that both positive and negative words would be perceived as larger in font size than neutral words in this very basic perceptual task. We term this potential effect affect amplification.

Consider what affect amplification should, theoretically, assess. It should assess the degree to which affective events, relative to neutral events, are particularly salient to a person. Salient information, in turn, is thought to be more consequential (Fiske & Taylor, 1991). If so, people who exhibit higher levels of affect amplification in the perception task may be more reactive to affective or emotional events. To investigate this possibility, we assessed affect amplification in the laboratory and subsequently conducted a daily diary protocol. In such protocols, emotional reactivity is revealed to the extent that daily levels of some type of emotion-relevant event (e.g., stressors) are more consequential in predicting daily levels of a relevant outcome (such as anxiety or worry) for some individuals relative to others (Bolger et al., 2003). We hypothesized that affect amplification, as an individual difference, would moderate the strength of such daily event-daily outcome relationships, such that these within-person, cross-day slopes would be higher at higher levels of affect amplification and lower at lower levels of affect amplification. To make a potential case for the generality of this phenomenon, we asked people to report on three types of daily events, with two outcomes for each type of daily event.

Method

Participants and Recruitment

The study was generally described as one examining daily experiences. It was emphasized, however, that there would be two quite different parts to the study – an initial laboratory session and a subsequent daily questionnaire – and that both parts of the study must be completed. Seventy (38 females, 90+% Caucasian) undergraduates from North Dakota State University completed the laboratory portion of the study and at least 10 of the 14 daily reports.

Affect Amplification

Overview

Participants arrived to the laboratory in groups of 6 or less and completed a perception task on computer. Instructions for the task stated that it would alternate between two very different types of perceptual judgments, the first requiring them to evaluate each presented word and the second requiring them to estimate the font size of the word. The evaluation portion of each trial was deemed important because there is doubt as to whether incidental affective stimuli are typically evaluated (Klauer & Musch, 2003) and our interest was not in the automaticity of such evaluations.

Stimuli

The task included 168 normed (Bradley & Lang, 1999) word stimuli, 56 of which were positive (e.g., life, warmth), 56 of which were negative (e.g., fear, neglect), and 56 of which were affectively neutral (e.g., paper, seat). On the basis of the Bradley and Lang norms, the stimuli differed substantially in valence (Ms = 2.78, 5.05, & 7.27 for negative, neutral, & positive words), F (2, 165) > 18000, but the negative (M = 5.53) and positive (M = 5.32) words were equal in arousal level, F (1, 110) = 1.36, p > .20.

Trial Procedures

There were 168 paired trials, one for each word stimulus. At the beginning of each trial, a word was randomly selected, capitalized, and presented at center screen. It was randomly assigned to one of seven font sizes – Times New Roman 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, or 22. This variation in actual font size rendered it apparent that such stimuli did in fact differ in font size, but importantly so not in a manner systematically varying by word affect. Participants evaluated each word as “good”, “bad”, or “neutral” by voicekey.

Subsequent to voicekey registration, a mouse cursor was presented just below the word, which remained on the screen. Individuals were then asked to estimate the font size of the presented word in relation to a comparison array presented along the left side of the computer screen. Font sizes for this comparison array ranged from Times New Roman 8 to Times New Roman 24, with one-point steps (counterbalanced from the smallest font at the top to the largest font at the bottom or vice versa). The array consisted of the capital letter “Z”, which was chosen because it is a letter that maximizes both width and height and was rare to presented words. We recorded the font size of the presented word and its perceived font size for each trial.

Affect Amplification Quantification

A bias score was computed for each trial. It subtracted perceived size from actual size. There was a general trend to perceive the font size of words as larger than actually presented (M = 2.21), an effect we ascribe to the impact of evaluating the words, which may increase their perceptual salience (Higgins, 1996). Of more importance, it was found that such size overestimations varied word valence, F (2, 92) = 14.25, p < .01, such that both positive (M = 2.41), F (1, 92) = 31.98, p < .01, and negative (M = 2.17), F (1, 92) = 4.79, p < .05, words were perceived to be larger in size than neutral (M = 2.03) words. Thus, there was a general tendency to overestimate the size of affective relative to neutral words.

Of importance, individuals who overestimated the size of positive words also overestimated the size of negative words, r = .77, p < .01. Accordingly, we averaged size overestimates for the two affective word categories – positive and negative – and then subtracted size overestimates for neutral words. Higher scores thus reflect greater tendencies to misperceive affective stimuli as larger than neutral stimuli – termed affect amplification.

In the main analyses below, affect amplification will be treated as a continuous predictor. Nonetheless, for illustrative purposes, it is useful to conduct a median split on this variable and then examine size estimations by valence for each group (low amplifiers versus high). Among low amplifiers, there was no effect of word valence, F (2, 68) = 1.32, p > .25 (Ms = 2.27, 2.27, & 2.12 for positive, neutral, & negative valence categories, respectively). Above the median on this variable, however, the effect for word valence was significant, F (2, 68) = 5.87, p < .01 (Ms = 2.31, 1.65, & 2.31). Thus, high amplifiers overestimate the size of positive and negative stimuli relative to neutral stimuli, whereas this tendency is absent below the median.

Experience Sampling Protocol and Measures

Overview

Following the laboratory session, individuals were asked to complete daily reports for 14 days in a row. A morning email with a link was sent each day. The survey itself was posted at 5 p.m. and taken down the next morning. Compliance with the protocol was very good in that the average participant completed 12.37 of the 14 reports (M = 88.36%). The survey included three types of affective events – stressful events, provocation events, and social support events – and six dependent measures, two for each event type.

Stressor Reactions

Stressful events are a common source of disruption in daily life (Chamberlain & Zika, 1990). We assessed stressor occurrence for each day on the basis of common stressors among college students (Crandall, Preisler, & Aussprung, 1992), as modified for use in daily experience sampling protocols (Compton et al., 2008). Participants reported on the extent to which (1 = not at all true today; 4 = very much true today) four common stressors (e.g., had a lot of responsibilities, too many things to do at once) occurred each day. Reliability for this scale was quantified by first averaging across days and then computing a Cronbach alpha coefficient across the four items (M = 2.31, alpha = .91).

Stressful events often precipitate cognitive failures such as memory lapses and difficulties in decision making (Broadbent, Cooper, FitzGerald, & Parkes, 1982). Such potential reactions to stressors were assessed by asking individuals to report on the extent to which (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) two common cognitive failures (I had trouble making up my mind today, I forgot appointments today) occurred on the day in question (M = 1.93, alpha = .78). Stressful events also precipitate the subjective experience of worry, defined as a negative affective ruminative activity (Molina & Borkovec, 1994). We assessed daily worry by asking participants to report the extent to which (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) two prototypical worry items (I worried about a lot of things today, my worries interfered with other activities today) characterized the self’s daily experiences (M = 2.35, alpha = .91).

Provocation Reactions

Interpersonal provocations are a significant source of frustration and anger (Wilkowski & Robinson, 2008). Indeed, meta-analytic reviews have concluded that interpersonal provocations are perhaps the best predictor of such emotional reactions, as well as the aggression likely to result (e.g., Bettencourt & Miller, 1996). Accordingly, we asked individuals to report on the extent to which (1 = not at all true today; 4 = very much true today) each day was characterized by interpersonal provocation (someone argued with me, someone criticized me). This event-based measure was reliable (M = 1.58, alpha = .89).

On the basis of animal and infant studies in part, Berkowitz (1993) contended that the first reaction to provocation likely involves the subjective experience of frustration. Accordingly, we assessed the extent to which (1 = not at all true today; 4 = very much true today) individuals reported daily perceptions consistent with frustration (I deserved something and did not get it, my plans were blocked: M = 1.58, alpha = .79). Additionally, potential reactions to provocation were assessed in terms of the emotional experience of anger. In the latter case, participants reported on the extent to which (1 = not at all; 5 = extremely) they experienced two commonly-used markers of anger (angry, annoyed: M = 1.99, alpha = .89).

Social Support Reactions

Affect amplification should predict malevolent reactions to interpersonal provocation, but should also predict benevolent reactions to the helpful actions of others. To examine the latter prediction, we drew from the social support literature. Social support is defined in terms of the extent to which important others are available and supportive when the self encounters significant problems. Support of this type has been linked to better emotional and health-related functioning (Uchino, Uno, & Holt-Lunstad, 1999). In our daily protocol, we asked individuals to report on the extent to which (1 = not at all true today; 4 = very much true today) social support was provided on particular days (someone was there when I needed them, received help or support from someone: M = 2.36, alpha = .94).

When others help us, we are likely to have helpful thoughts about other in return. Just such a dynamic is highlighted by interpersonal circumplex models (e.g., Kiesler, 1983). Accordingly, participants were asked to report on the extent to which (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) they had helpful thoughts (I thought about how I could help other people, I thought about the needs of other people: M = 3.19, alpha = .98) each day. In addition, participants were asked to characterize the extent (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) to which their interpersonal behavior each day could be characterized in terms of two adjectives (cold-hearted, reverse-scored, kind: M = 4.00, alpha = .70) characterizing the warmth dimension of the interpersonal circumplex (Wiggins, Trapnell, & Phillips, 1988).

Neuroticism Assessment

Our hypotheses concern emotional reactivity and it is clear that the trait of neuroticism does predict emotional reactivity, even in experience-sampling protocols such as the present one (Suls & Martin, 2005). It therefore seemed useful to assess the trait of neuroticism in the present study. We did so by administering the oft-used neuroticism scale of Goldberg (1999), which has been extensively validated (for a review, see Robinson & Gordon, 2011). Subsequent to the laboratory assessment of affect amplification, participants reported on the extent (1 = very inaccurate; 5 = very accurate) to which statements indicative of high (e.g., “get stressed out easily”) and low (e.g., “am relaxed most of the time”) neuroticism describe the self accurately, with the latter items reverse-scored (M = 2.95; alpha = .79).

Results

Neuroticism as a Predictor of Affect Amplification

Extensive experience with implicit measures in the personality literature has led us to view such measures as typically independent of self-reported traits (Robinson & Neighbors, 2006). This was true in the present study as well in that neuroticism, a good predictor of emotional reactivity, did not predict affect amplification, r = −.03, p > .80. Thus, potential relations between affect amplification and emotional reactivity cannot be viewed in terms of trait variations in neuroticism.

Correlations among Outcome Variables

To examine relations between the outcome variables, we created six scores for each person by averaging across days. These scores thus reflect a person’s average level of each variable (e.g., average worry). Such scores were then correlated with each other. The two stress-related outcomes – cognitive failures and worry – were positively correlated across individuals, r = .75, p < 01, as were the two provocation-related outcomes (frustration & anger), r = .68, p < .01, and the two social support-related outcomes (helpful thoughts & interpersonal warmth), r = .40, p < .01. All of these positive correlations make sense given the respective literatures that we drew from (e.g., frustration is a notable correlate of anger: Berkowitz, 1993).

Multi-Level Modeling Procedures

We used multi-level modeling (MLM) procedures, a type of mixed model suited to nested data (Fleeson, 2007), to examine key predictions. The data are nested because days (as many as 14) were nested within individuals. Each MLM analysis consisted of two predictors and one outcome variable. The analysis procedures are probably best explained in terms of an example. We hypothesized that affect amplification would interact with daily stressors to predict daily levels of worry. In this analysis, daily stressor levels constituted a within-person or “level 1” predictor. Daily stressor levels were person-centered such that their mean was 0 for each person, thus ensuring that interactions are not confounded by average levels of the event type in question (Enders & Tofighi, 2007). The “level 2” predictor was continuous between-subject variations in affect amplification, z-scored prior to analyses (Aiken & West, 1991). All analyses were conducted with the SAS Proc Mixed procedure, which will be unbiased by the fact that the number of completed daily reports varies slightly by person (Singer, 1998).

In the example MLM analysis, a main effect for the level 1 predictor was expected. This would mean that, independent of affect amplification levels, worry is higher on days marked by a higher frequency of stressors (a positive slope). A main effect for the level 2 predictor was not expected. This would mean that affect amplification does not predict average levels of worry or, in other words, its intercept. On the other hand, a cross-level interaction was hypothesized. This would mean that the slope defining relations between daily stressors and daily worry systematically varies by affect amplification. Such interactions, and there was only one interaction term in each MLM model, would constitute the primary test of whether higher levels of affect amplification are marked by higher levels of reactivity to emotional events. We report fixed effects, which are relevant to the hypotheses, but not random effects, which are not.

Stressor-Reactive Cognitive Failures

As hypothesized, but a novel contribution to the stress and experience sampling literatures, individuals reported more cognitive failures on high stress days relative to low stress days, b = .10, t = 3.48, p < .01. Affect amplification did not predict higher levels of cognitive failures overall, b = .02, t = 0.30, p > .75, nor should it as this individual difference should predict reactivity to stressors rather than cognitive failures in general terms. Of most importance, then, affect amplification moderated the extent to which daily stressors predicted cognitive failures, b = .08, t = 2.83, p < .01. Estimated means for this interaction (+/−1 SD for both measures) are displayed in the top panel of Figure 1, which confirms that daily stressor levels were more predictive of cognitive failures at high levels of affect amplification. Please note that the labels “low” and “high” are a mere convenience as they actually represent a specific (+1 or −1 SD) point along the predictor continuum. Simple slope analyses (Aiken & West, 1991) were then conducted. At low (-1 SD) levels of affect amplification, there was no relation between daily stressor levels and cognitive failures, b = .03, t = 0.60, p > .55. At high (+1 SD) levels of affect amplification, on the other hand, there was a systematic positive relationship between daily stressors and cognitive failures, b = .18, t = 4.75, p < .01. At least in relation to stressors and cognitive failures, then, higher levels of affect amplification predicted greater reactivity to affective events in daily life.

Figure 1.

Affect Amplification (AA) Moderates Reactivity to Daily Stressors in Terms of Cognitive Failures (Top Panel) and Worry (Bottom Panel)

Stressor-Reactive Worry

As might be expected, a greater frequency of daily stressors predicted greater worry, b = .48, t = 12.75, p < .01. Affect amplification did not predict higher levels of worry across days, b = .12, t = 1.35, p > .15. Of more importance, there was a cross-level interaction, b = .10, t = 2.97, p < .01. Estimated means for this cross-level interaction are reported in the bottom panel of Figure 1. Variations in daily stressors were predictive of worry at both low (−1 SD), b = .37, t = 6.96, p < .01, and high (+1 SD), b = .58, t = 12.02, p < .01, levels of affect amplification, but this relationship was stronger at high levels of affect amplification.

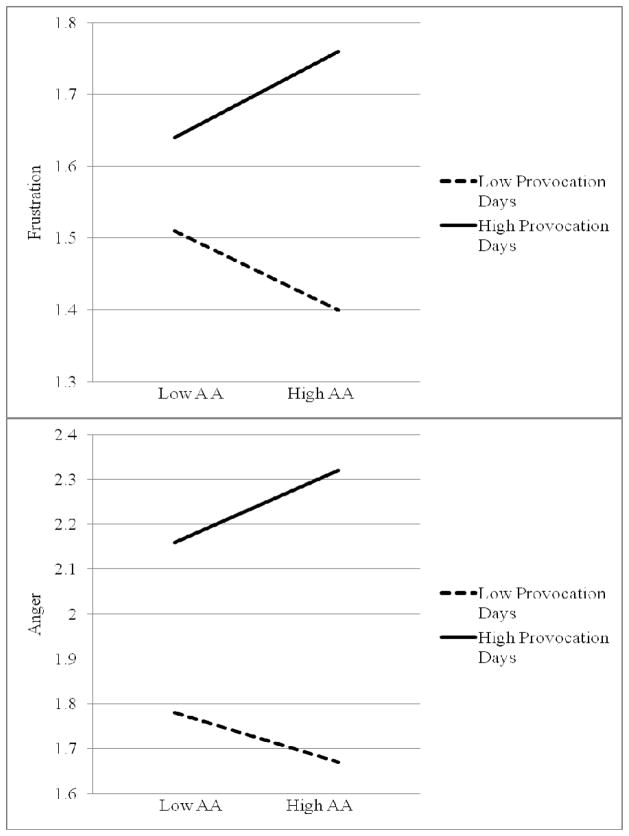

Provocation-Reactive Frustration

We hypothesized that daily provocations would engender higher levels of frustration, but particularly so at high levels of affect amplification. The relevant MLM revealed a main effect for daily provocations, b = .26, t = 5.64, p < .01, but no main effect for affect amplification, b = .00, t = 0.05, p > .95. Instead, affect amplification moderated the impact of daily provocations, b = .12, t = 2.49, p < .05. Estimated means for this interaction are reported in the top panel of Figure 2. Consistent with the figure, provocation-frustration relations were stronger at high (+1 SD) levels of affect amplification, b = .37, t = 5.70, p < .01, than at low (−1 SD) levels of affect amplification, b = .14, t = 2.11, p < .05.

Figure 2.

Affect Amplification (AA) Moderates Reactivity to Daily Provocations in Terms of Frustration (Top Panel) and Anger (Bottom Panel)

Provocation-Reactive Anger

Anger, relative to frustration, has clearer implications for reactive aggression (Wilkowski & Robinson, 2008) and we hypothesized that provocation-anger relations, too, would be stronger at higher levels of affect amplification. Daily provocations predicted daily anger, b = .52, t = 8.39, p < .01. Affect amplification did not predict higher levels of anger overall – that is, irrespective of daily provocations, b = .01, t = 0.17, p > .85. On the other hand, we found support for the idea that affect amplification moderated provocation-anger relations, b = .14, t = 2.14, p < .05. Estimated means for the interaction are reported in the bottom panel of Figure 2. Simple slope analyses were then performed. The provocation-anger relationship was a stronger one at high levels of affect amplification, b = .66, t = 7.35, p < .01, than at low levels of affect amplification, b = .38, t = 4.25, p < .01.

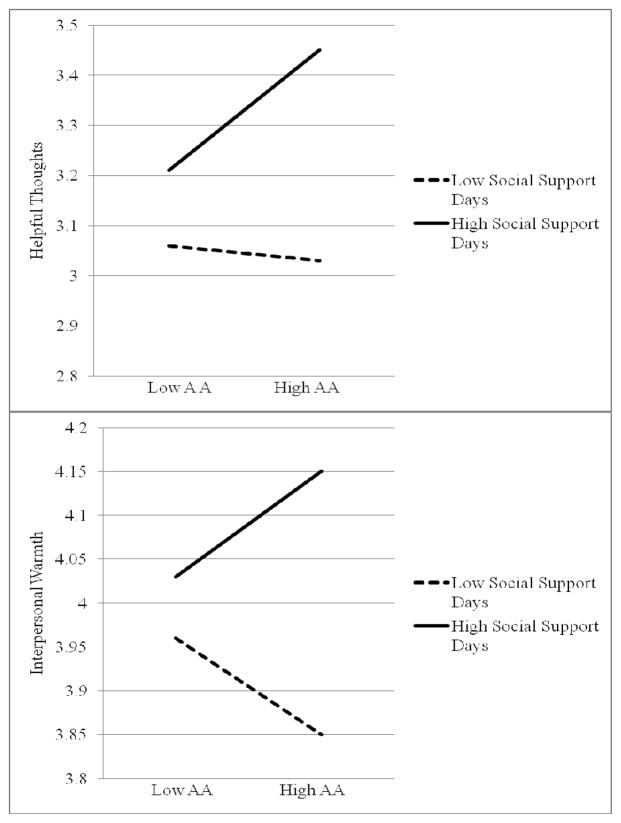

Daily Social Support and Helpful Thoughts

We hypothesized that affect amplification would also predict reactivity to benevolent interpersonal events. To examine this set of predictions, we turn to results involving daily social support. Helpful thoughts were higher on days on which higher levels of social support occurred, b = .22, t = 5.16, p < .01. Helpful thoughts were not generally higher among individuals higher in affect amplification, b = .06, t = 0.69, p > .45. Affect amplification did, however, moderate relations between daily social support and helpful thoughts, b = .11, t = 2.43, p < .05. The pattern of estimated means for this interaction is displayed in the top panel of Figure 3. Simple slopes testing revealed that daily social support predicted helpful thoughts robustly so at high levels of affect amplification, b = .32, t = 5.48, p < .01, but not at low levels of affect amplification, b = .11, t = 1.82, p > .05.

Figure 3.

Affect Amplification (AA) Moderates Reactivity to Daily Social Support in Terms of Helpful Thoughts (Top Panel) and Interpersonal Warmth (Bottom Panel)

Daily Social Support and Interpersonal Warmth

Reactivity to daily social support was examined in another manner was well namely, the extent to which individuals characterized themselves as interpersonally warm (or not) on particular days. Interpersonal warmth varied positively with daily social support among the sample as a whole, b = .14, t = 4.12, p < .01. Affect amplification did not predict interpersonal warmth irrespective of social support events, b = −.00, t = −0.00, p > .95. As hypothesized, however, the cross-level interaction was significant, b = .09, t = 2.53, p < .05. Estimated means for this interaction are displayed in the bottom panel of Figure 3. Strikingly, it was found that social support predicted interpersonal warmth at high levels of affect amplification, b = .23, t = 4.80, p < .01, but did not predict interpersonal warmth at low levels of affect amplification, b = .05, t = 1.06, p > .25.

Discussion

Normative Effects

Affective stimuli, relative to neutral stimuli, should reasonably be prioritized by the mind in that affect is a signal that an event is potentially important to the self and its goals (Lazarus, 1991; Schwarz & Clore, 1996). And, indeed, there is evidence that affective stimuli (either pleasant or unpleasant) are rated more interesting, are viewed for a longer period of time, and engender greater skin conductance activity (Lang, Bradley, & Cuthbert, 1997). There is also some evidence that affective stimuli receive enhanced neural processing (Junghofer, Bradley, Elbert, & Lang, 2001; Peyk et al., 2008). On the basis of such ideas, but more directly following from the work of Bruner and Postman (1948), we hypothesized that affective words, due to their greater posited salience, would appear larger in font size than neutral words. Just such results were found. That such results occurred with word stimuli suggests that substantive levels of emotional arousal are not necessary to observe this phenomenon. In addition, we emphasize ecological considerations: We view words every day, in different font sizes, yet affect biased such perceptions nonetheless.

There are certainly ways of extending the present normative results, however. It would be useful to examine whether affect amplification occurs in non-evaluative tasks (Klauer & Musch, 2003). Neuroticism did not predict affect amplification, but it is possible that other individual difference variables (e.g., need for evaluation: Jarvis & Petty, 1996) might. Manipulations of an evaluative or experiential mindset (e.g., Maas & van den Bos, 2009) may increase affect amplification and this direction of research can be advocated. The use of evaluative conditioning paradigms (e.g., Kerkhof et al., 2009) would also seem valuable in extending the present results in that they can demonstrate an influence of affect that results from learning rather than properties of affective stimuli that may be uncontrolled (Olson & Fazio, 2001). It would also be of value to determine whether affective, relative to neutral, words are perceived in a manner consistent with other operationalizations of perceptual salience such as perceived duration (Witherspoon & Allan, 1985) or perceived visual clarity (Reber et al., 1998). Finally, the use of haptic (action-based) perceptual paradigms might be advocated in establishing a broader scope for the normative findings reported (e.g., Topolinski & Pereira, 2012).

Individual Difference Findings

The affective processing literature has typically focused on how variations in task requirements, timing parameters, and stimuli alter affective processing (De Houwer, 2003; Klauer & Musch, 2003). By holding task requirements, timing parameters, and stimuli constant, we have suggested that affective processing tasks may have great potential in understanding how and why the emotional lives of people differ (e.g., Robinson & Compton, 2008). The primary purpose of the present study was to further this perspective in relation to a novel task that we thought would be sensitive to individual differences. People in fact differed greatly. Below the median on affect amplification, there was no tendency to overestimate the size of affective words versus neutral words. Above the median on affect amplification, this tendency was pronounced. Thus, affect amplification appears to characterize certain people but not others.

What are the consequences of such variations in affect amplification? From a general-purpose salience perspective, information that is more salient should be more consequential (Fiske & Taylor, 1991). It has also been observed that particularly motivated individuals – e.g., those motivated by a potential monetary reward (Balcetis & Dunning, 2010), thirst (Veltkamp et al., 2008), or hunger (Topolinski & Pereira, 2012) – often overestimate the size of motivation-relevant stimuli. On the aversive side, Riskind and Williams (2005) report that phobic stimuli are perceived to be larger and more dynamic to phobic individuals. Putting such perspectives and sources of data together, we suggested that higher levels of amplification should underlie and predict higher levels of reactivity to daily emotion-relevant events. This proved to be the case. Daily stressor levels were a better predictor of cognitive failures and worry at high levels of affect amplification. Daily provocation levels were a better predictor of frustration and anger at high levels of affect amplification. Finally, daily levels of social support were a better predictor of helpful thoughts and interpersonal warmth at high levels of affect amplification. We emphasize the breadth of these results across multiple daily event types and outcomes.

Yet, there are certainly future directions of research that should be conducted. Affect amplification, as an individual difference, should predict reactivity to laboratory emotional inductions, potentially in physiological as well as experiential terms. Affect amplifiers may favor emotional over rational factors in their decision-making. They may be more aggressive in response to laboratory provocations, yet they may also be more altruistic in laboratory paradigms in which empathy has been induced. Overall, we believe that there are both benefits and costs to affect amplification. Affect amplifiers may be more attuned to the emotional events of their lives, and emotionally intelligent in this sense, but may also be prone to emotion dysregulation as a result. Affect amplification, in sum, is likely a double-edged sword.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by COBRE Grant P20 GM103505 from the National Institute for General Medical Sciences (GM), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Its contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of GM or NIH.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Balcetis E, Dunning D. Wishful seeing: More desired objects are seen closer. Psychological Science. 2010;21:147–152. doi: 10.1177/0956797609356283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz L. Aggression: Its causes, consequences, and control. New York: Mcgraw- Hill Book Company; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC. The debate over dopamine’s role in reward: The case for incentive salience. Psychopharmacology. 2007;191:391–431. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0578-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettencourt BA, Miller N. Gender differences in aggression as a function of provocation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;119:422–447. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Davis A, Rafaeli E. Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:579–616. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley MM, Lang PJ. Affective norms for English words (ANEW) Gainesville, FL: The National Institute of Mental Health Center for the Study of Emotion and Attention, University of Florida; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent DE, Cooper PF, FitzGerald P, Parkes KR. The Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ) and its correlates. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1982;21:1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1982.tb01421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruner JS, Goodman CC. Value and need as organizing factors in perception. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 1947;42:33–44. doi: 10.1037/h0058484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruner JS, Postman L. Symbolic value as an organizing factor in perception. The Journal of Social Psychology. 1948;27:203–208. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1948.9918925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain K, Zika S. The minor events approach to stress: Support for the use of daily hassles. British Journal of Psychology. 1990;81:469–481. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1990.tb02373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton RJ, Robinson MD, Ode S, Quandt LC, Fineman SL, Carp J. Error-monitoring ability predicts daily stress regulation. Psychological Science. 2008;19:702–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crandall CS, Preisler JJ, Aussprung J. Measuring life event stress in the lives of college students: The Undergraduate Stress Questionnaire (USQ) Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1992;15:627–662. doi: 10.1007/BF00844860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Houwer J. A structural analysis of indirect measures of attitudes. In: Musch J, Klauer KC, editors. The psychology of evaluation: Affective processes in cognition and emotion. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003. pp. 219–244. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Tofighi D. Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A new look at an old issue. Psychological Methods. 2007;12:121–138. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske ST, Taylor SE. Social cognition. 2. New York: Mcgraw-Hill Book Company; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Fleeson W. Studying personality processes: Explaining changes in between-persons longitudinal and within-person multilevel models. In: Robins RW, Fraley RC, Krueger RF, editors. Handbook of research methods in personality psychology. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 523–542. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR. A broad-bandwidth, public domain, personality inventory measuring the lower-level facets of several five-factor models. In: Mervielde I, Deary I, De Fruyt F, Ostendorf F, editors. Personality psychology in Europe. Vol. 7. Tilburg, The Netherlands: Tilburg University Press; 1999. pp. 7–28. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET. Knowledge activation: Accessibility, applicability, and salience. In: Higgins ET, Kruglanski AW, editors. Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles. New York: Guilford Press; 1996. pp. 133–168. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis WBG, Petty RE. The need to evaluate. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:172–194. [Google Scholar]

- Junghofer M, Bradley MM, Elbert TR, Lang PJ. Fleeting images: A new look at early emotion discrimination. Psychophysiology. 2001;38:175–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerkhof I, Goesaert E, Dirikx T, Vansteenwegen D, Baeyens F, D’Hooge R, et al. Assessing valence indirectly and online. Cognition and Emotion. 2009;23:1615–1629. [Google Scholar]

- Kiesler DJ. The 1982 Interpersonal Circle: A taxonomy for complementarity in human transactions. Psychological Review. 1983;90:185–214. [Google Scholar]

- Klauer KC, Musch J. Affective priming: Findings and theories. In: Musch J, Klauer KC, editors. The psychology of evaluation: Affective processes in cognition and emotion. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003. pp. 7–49. [Google Scholar]

- Klein GS, Schlesinger HJ, Meister DE. The effect of personal values on perception: An experimental critique. Psychological Review. 1951;58:96–112. doi: 10.1037/h0059120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert WW, Solomon RL, Watson PD. Reinforcement and extinction as factors in size estimation. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1949;39:637–641. doi: 10.1037/h0060637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN. Motivated attention: Affect, activation, and action. In: Lang PJ, Simons RF, Balaban MT, editors. Attention and orienting: Sensory and motivational processes. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1997. pp. 97–135. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen RJ, Diener E, Cropanzano RS. Cognitive operations associated with individual differences in affect intensity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;53:767–774. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.53.4.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS. Emotion and adaptation. New York: Oxford University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Maas M, van den Bos K. An affective-experiential perspective on reactions to fair and unfair events: Individual differences in affect intensity moderated by experiential mindsets. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2009;45:667–675. [Google Scholar]

- Molina S, Borkovec TD. The Penn State Worry Questionnaire: Psychometric properties and associated characteristics. In: Davey GCL, Tallis F, editors. Worrying: Perspectives on theory, assessment and treatment. Oxford, England: John Wiley & Sons; 1994. pp. 265–283. [Google Scholar]

- Olson MA, Fazio RH. Implicit attitude formation through classical conditioning. Psychological Science. 2001;12:413–417. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyk P, Schupp HT, Elbert T, Junghofer M. Emotion processing in the visual brain: A MEG analysis. Brain Topography. 2008;20:205–215. doi: 10.1007/s10548-008-0052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reber R, Winkielman P, Schwarz N. Effects of perceptual fluency on affective judgments. Psychological Science. 1998;9:45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Riskind JH, Williams NL. The looming cognitive style and Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Distinctive danger schemas and cognitive phenomenology. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2005;29:7–27. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MD, Compton RJ. The happy mind in action: The cognitive basis of subjective well-being. In: Eid M, Larsen RJ, editors. The science of subjective well-being. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 220–338. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MD, Gordon KH. Personality dynamics: Insights from the personality social cognitive literature. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2011;93:161–176. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2010.542534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MD, Neighbors C. Catching the mind in action: Implicit methods in personality research and assessment. In: Eid M, Diener E, editors. Handbook of multimethod measurement in psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2006. pp. 115–125. [Google Scholar]

- Schupp HT, Cuthbert BN, Bradley MM, Cacioppo JT, Ito T, Lang PJ. Affective picture processing: The late positive potential is modulated by motivational relevance. Psychophysiology. 2000;37:257–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz N, Clore GL. Feelings and phenomenal experiences. In: Higgins ET, Kruglanski AW, editors. Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles. New York: Guilford Press; 1996. pp. 433–465. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD. Using SAS PROC MIXED to fit multilevel models, hierarchical models, and individual growth models. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 1998;23:323–355. [Google Scholar]

- Slovic P, Peters E. Risk perception and affect. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15:322–325. [Google Scholar]

- Suls J, Martin R. The daily life of the garden-variety neurotic: Reactivity, stressor exposure, mood spillover, and maladaptive coping. Journal of Personality. 2005;73:1485–1510. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topolinski S, Pereira PT. Mapping the tip of the tongue-deprivation, sensory sensitisation, and oral haptics. Perception. 2012;41:71–92. doi: 10.1068/p6903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN, Uno D, Holt-Lunstad J. Social support, physiological processes, and health. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1999;8:145–148. [Google Scholar]

- van Ulzen NR, Semin GR, Oudejans RRD, Beek PJ. Affective stimulus properties influence size perception and the Ebbinghaus illusion. Psychological Research. 2008;72:304–310. doi: 10.1007/s00426-007-0114-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veltkamp M, Aarts H, Custers R. Perception in the service of goal pursuit: Motivation to attain goals enhances the perceived size of goal-instrumental objects. Social Cognition. 2008;26:720–736. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins JS, Trapnell P, Phillips N. Psychometric and geometric characteristics of the Revised Interpersonal Adjective Scales (IAS-R) Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1988;23:517–530. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2304_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkowski BM, Robinson MD. The cognitive basis of trait anger and reactive aggression: An integrative analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2008;12:3–21. doi: 10.1177/1088868307309874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witherspoon D, Allan LG. The effect of prior presentation on temporal judgments in a perceptual identification task. Memory and Cognition. 1985;13:101–111. doi: 10.3758/bf03197003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]