Abstract

Objective

Review recent studies on spatial hearing abilities in children who use bilateral cochlear implants (BiCIs); compare performance of children who use BiCIs with that of children who have normal hearing.

Methods

Results from recent studies are reviewed in two categories. First, studies measured spatial hearing by using sound localization or identification methods, thereby focusing on localization accuracy. Second, studies that measured the ability of children to discriminate between sound source positions in the horizontal plane, thereby focusing on localization acuity, where performance was quantified using the minimum audible angle (MAA).

Results

Children with BiCIs have localization errors that vary over a wide range of performance. There is evidence that for many children errors are smaller when using two vs one CIs. In the bilateral condition, some children’s performance falls within the range of errors seen in children with normal hearing (less than 30 degree root-mean-square), but most children have errors that are significantly greater than those of children with normal hearing. On MAA tasks performance is generally significantly better (lower MAAs) when children are tested in the bilateral listening mode than in the unilateral listening mode; however, MAAs are generally higher than those measured in children with normal hearing.

Discussion

Results are discussed in the context of auditory experience, and also with regard to the lack of availability of binaural cues presented through the CI speech processors when the children are using their processors in everyday listening situations. The potential roles of interaural timing vs level cues are discussed.

In recent years, a growing number of children have received bilateral cochlear implants (BiCIs) in an effort to improve their ability to segregate speech from background noise and to localize sounds. These efforts were increased following evidence from adult patients demonstrating significant improvement in these abilities when using both CIs compared with a single CI (e.g., van Hoesel & Tyler, 2003; Nopp et al., 2004; Litovsky et al., 2009). There is one important factor that differentiates between the adult and pediatric populations. Many adults lose their hearing post-lingually after having been exposed to acoustic hearing, thus, activation of bilateral CIs most likely re-activates some aspects of their previously established spatial-hearing abilities. In contrast, many of the children receiving BiCIs are diagnosed with severe-to-profound hearing loss at birth, and receive little or no exposure to sound before adjusting to bilateral electric stimulation.

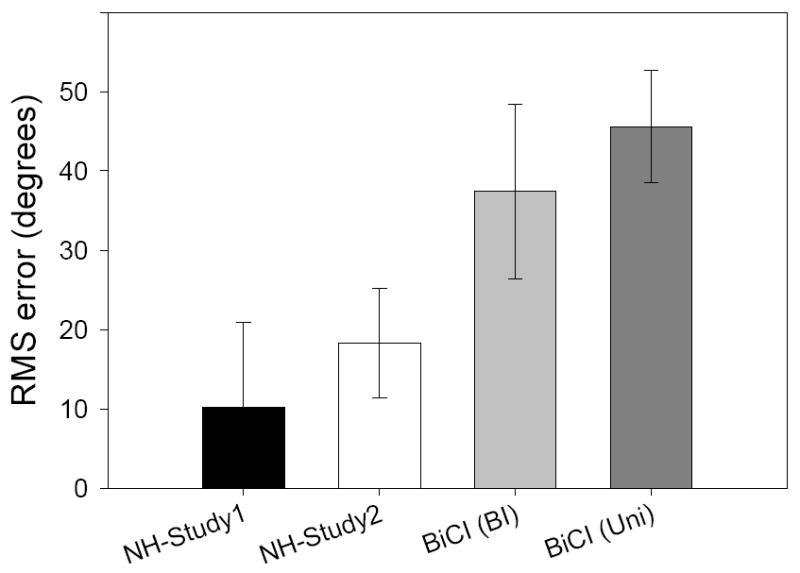

The current paper reviews recent studies from our lab on emergence of spatial hearing abilities in children who are fitted with BiCIs. Litovsky and colleagues have focused on measuring the emergence of spatial hearing skills in young BiCI users using a number of behavioral approaches. The goal has been to measure children’s ability to either localize source positions (accuracy), or to discriminate between sound source positions (acuity). Accuracy may reflect the extent to which a child has been able to develop a spatial-hearing “map.” The tasks, whereby children have to point to where a sound is perceived, may also be somewhat difficult and involve cognitive input or executive function, compared with discrimination tasks. Regarding accuracy, in normal-hearing adult listeners, error rates, often quantified by the root-mean-square (RMS) error, can be as small as a few degrees, (e.g., Hartmann, 1983; Middlebrooks & Greeen, 1991). Data from children with normal hearing are somewhat sparse, with several studies on the topic having been conducted recently, focusing on children between the ages of 4-10 years. Figure 1 summarizes data from three published studies (left). Grieco-Calub & Litovsky (2010) tested 7, 5-year old children and found errors ranging from 9-29° (avg of 18.3° ± 6.9° SD). Litovsky & Godar (2010) reported RMS errors ranging from 1.4-38° (avg of 10.2° ± 10.72° SD). These findings are in agreement with work of Van Deun et al. (2009) who reported average RMS errors of 10°, 6°, and 4° for children ages 4, 5 and 6 years, respectively. These values overlap with those obtained in adults, but tend to be higher, suggesting that some children reach adult-like maturity for sound localization by age 4-5 years and other children undergo a more protracted period of maturation (see also Litovsky, 2011 for review).

Figure 1.

Root mean square errors, in group means (±SD) are compared for two groups of children with normal hearing. NH-Study1 data are from Litovsky and Godar (2010), and NH-Study2 are from Grieco-Calub & Litovsky (2010). In addition, data from a group of children with BiCIs also tested by Grieco-Calub & Litovsky (2010) are shown, comparing their performance in the bilateral (BiCI(BI)) and unilateral (BiCI(Uni)) listening modes.

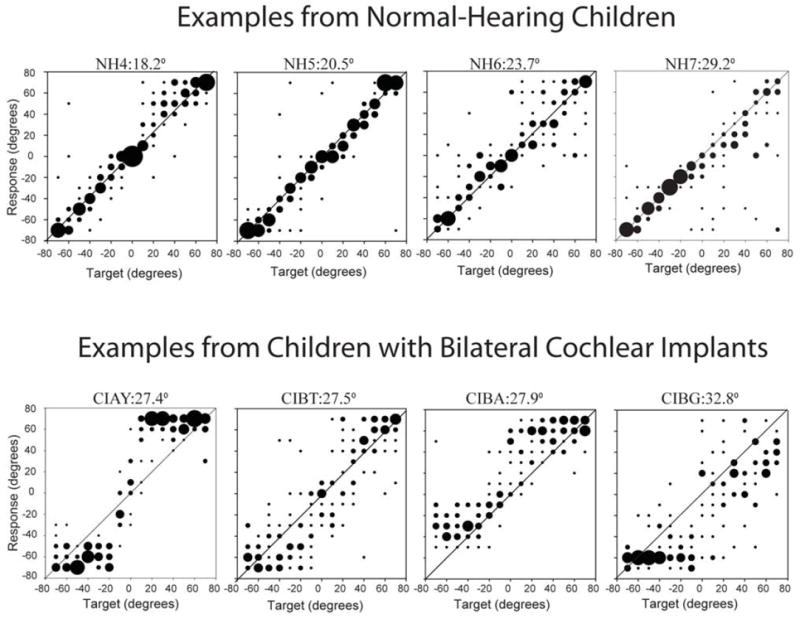

Within this context for normal-hearing children one can consider and assess data obtained from BiCI users. In addition to data from children with normal hearing, Figure 1 shows group average RMS errors reported by Grieco-Calub and Litovsky (2010) for 21 children ages 5-14 years who use BiCIs (right-most column) tested in the bilateral listening mode. RMS errors in 11/21 children were smaller when both CIs were activated compared with a unilateral listening mode, suggesting a bilateral benefit. When considering the bilateral listening mode, RMS errors ranged from 19°-56°. These data are comparable to another recent report by Van Deun et al. (2010) in which RMS errors for 30 children with BiCIs ranged from 13-63°. The range of errors seen in BiCI users overlaps with the range of 9°-29° observed in the group of children with normal hearing, however, only 6/21 children had results in that range. In addition, examples of raw data from that study are shown in Figure 2. Upon visual inspection of the raw data, it becomes clear that the types of errors made by the two groups of children are somewhat different. The children with normal hearing generally perceive the sound sources in the vicinity of their true location, responses generally falling within 1 to 3 loudspeaker locations away (i.e., 10°-30° errors). Compared with the normal-hearing children, children with bilateral CIs have many fewer trials with absolute correct identifications, and their responses on trials with errors tend to be more clustered rather than distributed. The data suggest that spatial hearing resolution or internal “map” of space is perhaps more blurred and less acutely developed in the CI users than in children with normal hearing. What is somewhat remarkable, however, is that the bilaterally implanted children are able to localize sounds at all, given that the hardware and signal processing in the implantable devices are far from ideal as far as providing binaural cues with fidelity. Finally, it is important to recognize that RMS error represents only one metric for evaluating performance on sound localization tasks, but this measure may not be representative of spatial hearing abilities and listening strategies employed by these children.

Figure 2.

Examples of raw data from the localization study by -Calub & Litovsky (2010) are shown. There are 4 children with normal hearing and 4 with BiCIs. Within each panel, responses for perceived source positions are plotted as a function of actual source positions, along the horizontal plane, spanning -70 to +70 degrees. The size of the dots represents the number of responses for a given target location, such that larger dots reflect a greater number of responses at that location. The diagonal line represents perfect performance.

Another measure of spatial hearing is that of acuity, whereby discrimination between source locations is measured. In normal-hearing infants this ability is measured within a few months after birth, as soon as children are capable of a conditioned head turn response. The minimum audible angle (MAA), or smallest angle between two source locations that can be reliably discriminated, undergoes significant change during the first few years of life. Much of this notable development in normal hearing children thus occurs during the time window in which BiCI recipients might typically experience deafness and/or periods of unilateral hearing. The question is whether, upon activation of bilateral hearing, they are able to use spatial cues to discriminate right vs. left, and at what angular source separation. Because the task is relatively straight forward, whereby children are trained to report whether a sound is presented from the right vs. left, this measure has been applied in a number of studies and with BiCI users ranging in age from 2-16 years (see also Litovsky and Madell, 2010; Litovsky, 2011).

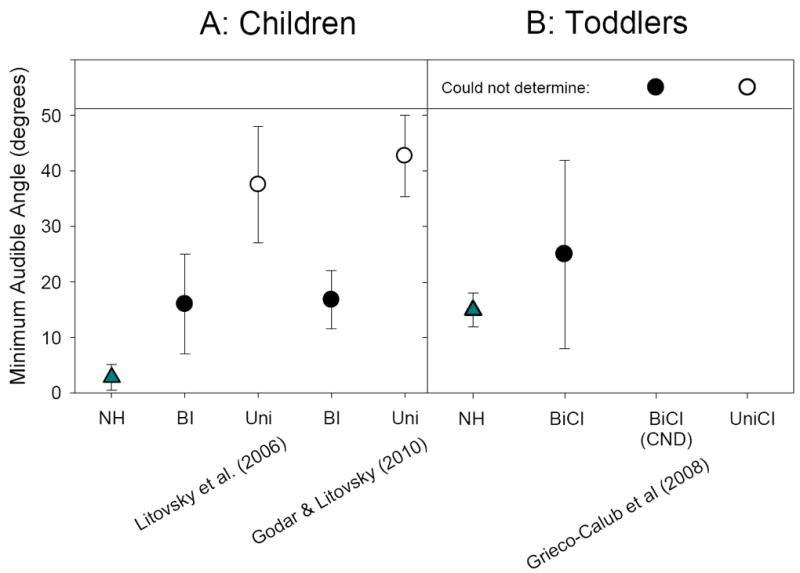

Figure 3 shows MAA thresholds from several studies, with children ranging in age from 3.5-16 years (Litovsky et al., 2006) or 5-10 years (Godar and Litovsky, 2010), and a group of 2-year old toddlers (Grieco-Calub et al., 2008). In the two groups of children who use BiCIs (left panel), performance was significantly better (lower MAAs) when tested in the bilateral listening mode (filled circles) than in the unilateral listening mode (open circles). For these same children, MAA thresholds were nonetheless higher than those measured in children with normal hearing (triangles), suggesting that there is a gap in performance between bilaterally implanted children and their peers with normal hearing.

Figure 3.

Minimum audible angle (MAA) thresholds are compared for several studies. Panel A includes data from children. Triangles show data from 5-year old normal-hearing children (modified from Litovsky, 1997). In addition, there are two sets of data from studies in which BiCI users were tested in bilateral (filled circle) vs unilateral listening modes (open circle). In one study children ranged in age from 3.5 to 16 (modified from Litovsky et al., 2006), and in a second study children ranged in age from 5-10 years (modified from Godar and Litovsky, 2010) Panel B includes MAA threshold data from toddlers who were approximately age 2.5 years at the time of testing. Triangle show data from normal-hearing children, filled circles show data from BiCI users who fell into two groups, and open circles how data from unilateral CI users (modified from Grieco-Calub et al., 2008).

The gap in performance has raised interesting issues in recent years as the age of bilateral implantation has steadily decreased. One obvious issue is whether children who are activated in both ears at a younger age, and have undergone shorter periods of auditory deprivation prior to stimulation will “catch up” with their age-matched peers more readily than the children who are activated at an older age. In the Grieco-Calub et al (2008) study, toddlers (right panel) who were BiCI users fell into two groups: in one group children were able to perform the task (BiCI), while a second group were unable to perform the task (BiCI (CND), with no obvious factor differentiating them from the former group. Also noted by the authors was the fact that within the BiCI group MAAs were highly variable, such that several of the children had MAAs that were in fact within the range of thresholds observe in the normal hearing group. A group of toddlers who were unilaterally implanted were also tested (UniCI), but none of them could perform the task either. A major difference between the toddlers and children is the age at which the second CI was surgically implanted and activated. While the children were bilaterally activated at an average age of 6.5 years, the toddlers were bilaterally activated at an average age of 1 year, 9 months. This finding opens up the possibility that bilateral activation at a young age may lead to spatial hearing acuity that is closer to the normal-hearing range of performance. What is not known from these studies to date is how these early-implanted bilaterally activated children will perform relative to their normal-hearing peers as they become older.

A number of remaining issues exist that would have to be studied more extensively prior to concluding which factors have lead to the gap in performance between normal hearing children and BiCI users. First, it is important to examine effects related to matching performance by age as well as by amount of auditory experience. One might hypothesize that children with BiCIs have had less exposure to auditory stimulation, in particular to stimulation in both ears. A more complicated issue is related to the engineering of the devices. The hardware and signal processing in the implantable devices are far from ideal as far as providing binaural cues with fidelity. Bilateral CI users are essentially fit with two separate monaural systems. Speech processing strategies in clinical processors utilize pulsatile stimulation, whereby the envelope of the signal is extracted within frequency bands and used to set stimulation levels for each band. Notably, the fine-structure information in the signal is discarded. Although ITDs in the envelopes may be present, because the processors have independent switch-on times, the ITD can vary dynamically and unreliably (van Hoesel, 2004). In addition, the microphones are not placed in the ear in a manner that maximizes the capture of directional cues such as spectrum and level cues. Microphone characteristics, independent automatic gain control and compression settings may also distort the monaural level directional cues that would otherwise be present in the horizontal plane. If children who use BiCIs do not receive synchronized binaural stimulation such that spatial cues are preserved and presented with fidelity, they might be less likely to develop the ability to localize sounds with great accuracy.

A binaural cue that is most likely available and used by BiCI users is the interaural level difference cue (ILD), which in normal hearing listeners is known to be less robust and ideal for spatial hearing than the “gold standard” interaural time difference (ITD) cue. However, if ILDs are present and used by the children, then perhaps their use can be maximized. It may be the case that children with BiCIs would benefit from extra training and feedback in order to solidify a reasonably stable and accurate spatial hearing map that depends on ILDs. The possibility that ILDs could be available through the speech processors, and perhaps worth focusing on, is important to consider in light of recent observations in adults who use BiCIs. One of the most interesting facets of studying adults who receive CIs is the opportunity to explore the effect of short- and long-term auditory deprivation on perception, in this case on binaural sensitivity. Several studies have focused on using binaural stimulation that is carefully controlled, such that electrically pulsed signals are transmitted directly to specific electrodes in the electrode arrays of the CIs. Electrodes in the right and left ears are selected so that sounds delivered to those electrodes are matched in pitch and loudness. These prerequisites ensure that the binaural system receives binaural cues with fidelity. Results suggest that adults whose onset of deafness occurs during adulthood, after having had years of exposure to acoustic cues, have sensitivity to ITD cues, some within the range seen in normal hearing listeners (Long et al., 2006; Laback et al., 2007; van Hoesel, 2007; Poon et al., 2009; van Hoesel et al., 2009). In a recent study Litovsky et al. (2010) measured binaural sensitivity in three groups of adult listeners who had become deaf at various stages in life: (a) adults who became deaf when they were very young children (prelingual); adults who became deaf during their childhood after experiencing acoustic hearing for some years (childhood); adults whose onset of deafness occurred after they reached adult age (adult). Results suggest that ITD sensitivity is impacted by early deprivation, such that none of the subjects in the pre-lingual group had access to ITDs, while subjects in the other groups retained sensitivity to ITDs. The primary difference between the pre-lingual and childhood-onset group was that the latter heard sound for the first 8-10 years of life, whereas the former did not recall having had “normal hearing”; rather they have a history of severe-to-profound hearing loss from birth or very soon thereafter. It is difficult to assess how many years of exposure to acoustic input may be necessary for the establishment of ITD-dependent binaural sensitivity. It is noteworthy that ILD cue sensitivity was present in all subjects tested by Litovsky et al. (2010). That is, even the pre-lingually deafened adults were able to use ILDs to perceive laterally displaced images “in the head” when ILDs were controlled. These findings suggest that the mechanisms involved in processing ITD cues are more susceptible to hearing loss than are the mechanisms associated with ILDs. From a practical point of view, the lack of sensitivity to ITD may not be critical to functionality with today’s CI processors.

Finally, as mentioned above, speech processing strategies do not preserve the fine-structure cues that can give rise to ITDs. In fact, the resulting stimuli in CIs bear some resemblance to acoustic stimuli comprising of high-frequency carriers that are amplitude-modulated. Normal hearing adults are known to be sensitive to ITDs in the envelopes of these high-frequency modulated stimuli (e.g., Bernstein & Trahiotis, 2002). There is the possibility that in bilateral CIs, when stimuli are presented in the free field, ITDs in the envelopes may be available and usable, as they are in controlled binaural experiments with single pairs of electrodes (van Hoesel et al., 2009). This would have to be determined through further investigation.

In conclusion, children who are fitted with BiCIs are able to discriminate source locations better than children who are fitted with a single CI, and they are able to localize sounds with smaller error rates. However, their performance is generally worse than that of their normal-hearing peers. The reasons for this gap in performance are yet to be well understood. It is worth investigating whether the effects of early auditory deprivation on binaural sensitivity are limited to ITD processing that depends on low-frequency stimuli and encoding of fine structure. In that case, bilateral CI users with early deprivation may ultimately be able to recover binaural sensitivity by relying on the auditory circuits that encode ILDs and/or ITDs in the envelopes of high-frequency carriers.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health Grant Numbers R01 DC008365 (R. Litovsky, PI) and R21 DC 006641 (R. Litovsky, PI), and 5P30HD003352 (M. Seltzer, PI). The author is particularly grateful to S. Godar and T. Grieco-Calub for their work on publications that are discussed in this review.

References

- Bernstein LR, Trahiotis C. Enhancing sensitivity to interaural delays at high frequencies by using “transposed stimuli”. J Acoust Soc Am. 2002;112(3 Pt 1):1026–36. doi: 10.1121/1.1497620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godar SP, Litovsky RY. Experience with bilateral cochlear implants improves sound localization acuity in children. Otol Neurotol. 2010;31(8):1287–92. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181e75784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieco-Calub TM, Litovsky RY. Sound localization skills in children who use bilateral cochlear implants and in children with normal acoustic hearing. Ear Hear. 2010;31(5):645–56. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181e50a1d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieco-Calub TM, Litovsky RY, Werner LA. Using the observer-based psychophysical procedure to assess localization acuity in toddlers who use bilateral cochlear implants. Otol Neurotol. 2008;29(2):235–9. doi: 10.1097/mao.0b013e31816250fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann WM. Localization of sound in rooms. J Acoust Soc Am. 2983;74(5):1380–91. doi: 10.1121/1.390163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laback B, Majdak P, Baumgartner WD. Lateralization discrimination of interaural time delays in four-pulse sequences in electric and acoustic hearing. J Acoust Soc Am. 2007;121(4):2182–91. doi: 10.1121/1.2642280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litovsky RY. Development of binaural and spatial hearing. In: Werner LA, Popper A, Fay R, editors. Springer Handbook of Auditory Research. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2011. In press. [Google Scholar]

- Litovsky RY, Godar SP. Difference in precedence effect between children and adults signifies development of sound localization abilities in complex listening tasks. J Acoust Soc Am. 2010;128(4):1979–91. doi: 10.1121/1.3478849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litovsky RY, Johnstone PM, Godar SP, Agrawal S, Parkinson A, Peters R, Lake J. Bilateral cochlear implants in children: localization acuity measured with minimum audible angle. Ear Hear. 2006;27(1):43–59. doi: 10.1097/01.aud.0000194515.28023.4b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litovsky RY, Jones GL, Agrawal S, van Hoesel R. Effect of age at onset of deafness on binaural sensitivity in electric hearing in humans. J Acoust Soc Am. 2010;127(1):400–14. doi: 10.1121/1.3257546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litovsky RY, Madell J. Bilateral cochlear implants in children. In: Eisenberg L, editor. Clinical Management of Children with Cochlear Implants. Plural Publishing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Litovsky RY, Parkinson A, Arcaroli J. Spatial hearing and speech intelligibility in bilateral cochlear implant users. Ear Hear. 2009;30(4):419–31. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181a165be. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long CJ, Carlyon RP, Litovsky RY, Downs DH. Binaural unmasking with bilateral cochlear implants. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2006;7(4):352–60. doi: 10.1007/s10162-006-0049-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middlebrooks JC, Green DM. Sound localization by human listeners. Annu Rev Psychol. 1991;42:135–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.42.020191.001031. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nopp P, Schleich P, D’Haese P. Sound localization in bilateral users of MED-EL COMBI 40/40+ cochlear implants. Ear Hear. 2004;25(3):205–14. doi: 10.1097/01.aud.0000130793.20444.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon BB, Eddington DK, Noel V, Colburn HS. Sensitivity to interaural time difference with bilateral cochlear implants: Development over time and effect of interaural electrode spacing. J Acoust Soc Am. 2009;126(2):806–15. doi: 10.1121/1.3158821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Deun L, van Wieringen A, Van den Bogaert T, Scherf F, Offeciers FE, Van de Heyning PH, Desloovere C, Dhooge IJ, Deggouj N, De Raeve L, Wouters J. Sound localization, sound lateralization, and binaural masking level differences in young children with normal hearing. Ear Hear. 2009;30(2):178–90. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e318194256b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Deun L, van Wieringen A, Scherf F, Deggouj N, Desloovere C, Offeciers FE, Van de Heyning PH, Dhooge, Wouters J. Earlier intervention leads to better sound localization in children with bilateral cochlear implants. Audiol Neurootol. 2010;15(1):7–17. doi: 10.1159/000218358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hoesel RJ. Exploring the benefits of bilateral cochlear implants. Audiol Neurootol. 2004;9(4):234–46. doi: 10.1159/000078393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hoesel RJ. Sensitivity to binaural timing in bilateral cochlear implant users. J Acoust Soc Am. 2007;121(4):2192–206. doi: 10.1121/1.2537300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hoesel RJ, Tyler RS. Speech perception, localization, and lateralization with bilateral cochlear implants. J Acoust Soc Am. 2003;113(3):1617–30. doi: 10.1121/1.1539520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hoesel RJ, Jones GL, Litovsky RY. Interaural time-delay sensitivity in bilateral cochlear implant users: effects of pulse rate, modulation rate, and place of stimulation. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2009;10(4):557–67. doi: 10.1007/s10162-009-0175-x. Epub 2009 Jun 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]