Background: The bone phenotype of NHERF1-null mice was ascribed to indirect actions.

Results: With dietary supplementation to maintain normal serum phosphate, NHERF1-deficient mice showed aberrant bone mineralization and decreased bone quality. Osteoblast differentiation from mesenchymal stem cells was impaired.

Conclusion: NHERF1 is expressed in mineralizing osteoblasts and directly regulates bone formation.

Significance: We provide an experimentally validated mechanistic model of NHERF1 regulating bone formation.

Keywords: Bone, Membrane Transport, Osteoblasts, Parathyroid Hormone, Scaffold Proteins, NHERF1, PTHR Signaling, Acid Transport, Mineralization, Osteoblast Differentiation

Abstract

Bone formation requires synthesis, secretion, and mineralization of matrix. Deficiencies in these processes produce bone defects. The absence of the PDZ domain protein Na+/H+ exchange regulatory factor 1 (NHERF1) in mice, or its mutation in humans, causes osteomalacia believed to reflect renal phosphate wasting. We show that NHERF1 is expressed by mineralizing osteoblasts and organizes Na+/H+ exchangers (NHEs) and the PTH receptor. NHERF1-null mice display reduced bone formation and wide mineralizing fronts despite elimination of phosphate wasting by dietary supplementation. Bone mass was normal, reflecting coordinated reduction of bone resorption and formation. NHERF1-null bone had decreased strength, consistent with compromised matrix quality. Mesenchymal stem cells from NHERF1-null mice showed limited osteoblast differentiation but enhanced adipocyte differentiation. PTH signaling and Na+/H+ exchange were dysregulated in these cells. Osteoclast differentiation from monocytes was unaffected. Thus, NHERF1 is required for normal osteoblast differentiation and matrix synthesis. In its absence, compensatory mechanisms maintain bone mass, but bone strength is reduced.

Introduction

Bone formation requires the coordinated secretion of osteoid, the organic matrix of bone, with mineralization of the matrix. Adequate Ca2+, phosphate, and vitamin D are essential for mineralization. Calcium, phosphate, and OH− precipitate as hydroxyapatite within the osteoid. Mineral deposition is an active process that normally occurs in a narrow band proceeding from mineralized osteoid in an active front toward the surface (1). Mineral ion deficiencies can impair mineralization with retained unmineralized osteoid, particularly in hypophosphatemic osteomalacia (2).

The Na+/H+ exchange regulatory factors (NHERFs)2 are PDZ (PSD-95, disc-large, and ZO-1) proteins (3) that assemble protein complexes and regulate their functions. NHERF1 associates with Na+/H+ exchangers (NHEs) (4, 5), the parathyroid hormone receptor (PTHR) (6–8) that has been implicated in bone anabolism (9, 10), and renal sodium phosphate cotransporter 2a (11, 12) that mediates renal phosphate reabsorption. Osteoblasts employ NHE1 and NHE6 to eliminate the acid produced by precipitation of Ca2+ as hydroxyapatite deposited in the osteoid (13). NHEs, in turn, are regulated by NHERF1 and NHERF2 (4).

Mice deficient in NHERF1 exhibit prominent renal phosphate wasting and skeletal abnormalities (11), as do patients harboring NHERF1 mutations (14). In both cases the bone pathology, which is characterized by severe osteomalacia with accumulation of nonmineralized osteoid, was interpreted as a secondary consequence of hypophosphatemia. However, mice lacking sodium phosphate cotransporter 2a exhibit even greater losses of phosphate but have minimal bone changes (15–17). This discrepancy raised the issue that the skeletal phenotype of NHERF1-null mice might also reflect direct consequences of the absence of NHERF1 in bone.

Although not previously identified in primary, matrix-producing osteoblasts, NHERF1 is prominently expressed on mineralizing cells of wild-type mice. To determine whether NHERF1 directly regulates mineralization, we maintained NHERF1-null mice on a diet supplemented with phosphorous to exclude secondary skeletal effects caused by renal phosphate wasting. Bone from NHERF1-null mice exhibited delayed mineralization with broad mineral deposition bands and retarded overall bone synthesis. Delayed bone formation was matched by reduced bone resorption so that net bone density was nearly normal, although bone quality was reduced. Further in vitro studies using mesenchymal stem cells showed that these deficiencies reflect abnormal differentiation and function of osteoblasts in the absence of NHERF1.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice

NHERF1-null mice (11) were intercrossed to generate seventh generation NHERF1-null mice and were maintained in a C57BL/6J background in a pathogen-free environment with NHERF1 wild-type littermate controls. The animals were maintained on Purina/PMI (St. Paul, MN) Prolab RMH 3000, 26% protein, 14% fat, 60% carbohydrate supplemented for growth and reproduction including 1.0% calcium and 0.75% phosphorus (0.44% non-phytate), ad libitum. The animals were genotyped by PCR of tail DNA samples. The studies were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee.

Histology and Histomorphometry

The animals were labeled with calcein, 25 μg/g of animal weight, 4 days and 1 day prior to sacrifice. Bone was fixed in 5% formaldehyde overnight at 4 °C and stored in 70% ethanol at −20 °C until used. Microcomputed tomography was performed on a Viva CT40 (Scanco, Bassersdorf, Switzerland). The undecalcified sections were 4-μm frozen vertebrae sections cut on a Microm HM 505E cryostat using tape transfer (CryoJane; Instrumedics, St. Louis, MO). Histomorphometric analysis (18) was by blinded observers. Bone mineral was stained with 2% AgNO3 under UV light (von Kossa). Unstained sections were used to determine the bone formation rate by assessment of calcein label or for antibody labeling of additional targets. Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) was labeled using 0.01% naphthol phosphate substrate and 5 mg/ml fast red violet in 50 mm sodium tartrate and 90 mm sodium acetate at pH 5.0. Alkaline phosphatase was labeled in citrate-buffered saline at pH 8 with 0.01% naphthol phosphate and 5 mg/ml fast blue. Adipocyte labeling used 2 mg/ml Oil Red O for 1 h. The reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich.

Spectrometric and Mechanical Analysis

Humeri or tibiae from wild-type and NHERF1−/− mice were used. Raman emission from 810 to 950 nm was measured as orthogonal emission using a photomultiplier to record the spectrum from a diffraction monochromator with 1-nm slit, using excitation at 800 nm, also with a 1-nm slit, on an Aminco Bowman Series 2 luminescence spectrometer (Thermo Electron, Waltham, MA). Marrow and periosteum were removed, and the bones were mounted in a clamp to rotate them in the excitation beam. The 1660 cm−1/1690 cm−1 emission ratio was used as an indicator of collagen cross-linking (19). The measurements were averaged over four scans at 90° rotation and are the means of four samples. Three-point bending was performed using an Instron 5564 instrument (Instron, Norwood, MA). The bones were positioned horizontally, anterior upward, between 10-mm supports. Load was applied at 500 μm/min at mid-diaphysis until failure with load/deflection used to calculate stiffness and failure strength (20).

Bone Marrow, Mesenchymal Stem Cells, Osteoblasts, and Osteoclasts

Whole bone marrow and bone marrow-derived MCSs were harvested, and MSC were grown and differentiated as described (21). Briefly, cells from one mouse were used for each MSC preparation; marrow was collected by flushing bones with RPMI1640 (Invitrogen) with 12% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone-Invitrogen). Disaggregated marrow cells were plated at 5 × 105/cm2. Nonadherent cells were washed off and replated at 106/cm2 after 2 h at 37 °C. After 48 h, nonadherent cells were discarded, and the adherent cells were cultured in MesenCult with serum supplement (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada). The cells were fed twice weekly. Cultures at 80% confluence were trypsinized and replated at 5 × 105/cm2. MSCs were used at passages 5–10. Osteoblast differentiation was induced in confluent cells using DMEM with either 25 mm glucose or 5.5 mm glucose as indicated under “Results,” 10% fetal bovine serum, 30 μg/ml ascorbic acid, 200 nm hydrocortisone, and 10 mm glycerol-2-phosphate from Lonza (Walkersville, MD). The media were replaced every 3 days; differentiation took 3–5 weeks. For osteoclast differentiation, spleens from wild-type, and NHERF1-null mice were removed, gently broken, and passed through a cell strainer. The cells were suspended in RPMI 1640 with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum. After red cell lysis, the cells were collected and plated at 2 × 105/cm2 in Eagle's MEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 20 ng/ml mouse RANKL, and 10 ng/ml mouse CSF for 10 days. Alternative osteoclast differentiation used MSC co-cultured with spleen cells. For this, spleen cells were plated at 2 × 105/cm2 in Eagle's MEM with 10% FBS in the presence of 20 ng/ml murine macrophage CSF for 2 days, and then 5 × 105/cm2 MSC were added. The cultures were maintained in low glucose DMEM with 10% FBS and 20 ng/ml macrophage CSF for a further 5 days, after which the TRAP-expressing cell area was determined.

Antibody Labeling and Western Blots

Frozen sections fixed with cold acetone were used. Goat anti-NHE6 (anti-C-terminal 20-mer peptide, sc-16111) was from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA). Polyclonal rabbit anti-EBP50 (PA1–090) was from Thermo (Rockford, IL). These were applied at 4 μg/ml for 1 h, 20 °C, followed by secondary anti-antibodies with fluorescent labels indicated (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) for 1 h at 20 °C. The sections were photographed using oil objectives. The images were acquired using a 14-bit 2048 × 2048-pixel charge-coupled detector array (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI). A green channel indicates signal from excitation at 450–490 nm using a 510-nm dichroic mirror and a 520-nm barrier; a red signal represents excitation 536–556 nm using a 580-nm dichroic mirror and a 590-nm barrier filter. Signal coincidence analysis used ImageJ co-localization finder software and excluded signal ratio <50%. The TRAP in situ labeled quantitative area was determined using a hue, saturation, and intensity filter to select the red-blue garnet color as a fraction of total area (Fovea Pro; Reindeer Graphics, Asheville, NC). Western blots were performed as described (7). NHERF1 monoclonal antibody for Western blot was purchased from Abcam (ab9526; Cambridge, MA). Actin polyclonal antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz (sc-1616-R; Santa Cruz, CA). Active β-catenin antibody (05-665) and total β-catenin antibody (06-734) were from Millipore (Billerica, MA). Phosphor-CREB antibody (9191s), total CREB antibody (9197s), phosphor-Akt (4058s), and total Akt (9272) antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA).

RNA and Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated by oligo(dT) affinity chromatography (RNeasy; Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized using random hexamers and Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Superscript III; Invitrogen). Quantitative PCR was performed on a MX3000P (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Reactions were performed in 25 μl with 12.5 μl of premixed SYBR green (N′,N′-dimethyl-N-[4-[(E)-(3-methyl-1,3-benzothiazol-2-ylidene)methyl]-1-phenylquinolin-1-ium-2-yl]-N-propylpropane-1,3-diamine), NTPs, buffer, and polymerase (SYBR Green Master Mix; Stratagene), to which 250 nm primers and 1 μl of first strand cDNA were added. After 10 min at 95 °C, the mixture was amplified in cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 59 °C, and 1 min at 72 °C. Product size was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis. The primers for real time PCR are listed in Table 1. Product abundance relative to control was calculated assuming linearity of threshold cycle to log (initial copies) (22).

TABLE 1.

Mouse primers sequences and expected sizes of PCR products

| Genes | GenBankTM accession number | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bp | ||||

| aP2 | NM_024406.2 | 5′-CATGGCCAAGCCCAACAT-3′ | 5′-CGCCCAGTTTGAAGGAAATC-3′ | 100 |

| Actin | NM_007393.3 | 5′-GATATCGCTGCGCTGGTCGTC-3′ | 5′-ACGCAGCTCATTGTAGAAGGTGTG-3′ | 275 |

| ALP | NM_007431.2 | 5′-ATCGGAACAACCTGACTGACCCTT-3′ | 5′-ACCCTCATGATGTCCGTGGTCAAT-3′ | 131 |

| ATPa3 | NM_178405.3 | 5′-TGACCACAAGCTGTCCTTGGATGA-3′ | 5′-AAGCTGACGACAGAACTTGACCCA-3′ | 163 |

| Cathepsin-K | NM_007802.3 | 5′-CAGCAGAGGTGTGTACTATG-3′ | 5′-GCGTTGTTCTTATTCCGAGC-3′ | 174 |

| C/EBPα | NM_007678.3 | 5′-CGCAAGAGCCGAGATAAAGC-3′ | 5′-CGGTCATTGTCACTGGTCAACT-3′ | 79 |

| Col1a1 | NM_007742.3 | 5′-TTCTCCTGGCAAAGACGGACTCAA-3′ | 5′-AGGAAGCTGAAGTCATAACCGCCA-3′ | 159 |

| NHE1 | NM_016981.2 | 5′-CCTGACCTGGTTCATCAACA-3′ | 5′-TCATGCCCTGCACAAAGACG-3′ | 199 |

| NHE6 | NM_172780.3 | 5′-ATTTGGGGACCACGAACTAGT-3′ | 5′-CCGGACTGTGTCTCGTATCA-3′ | 83 |

| NHERF1 | NM_012030.2 | 5′-TCGGGGTTGTTGGCTGGAGAC-3′ | 5′-GAGCTCGCGCAAGTGGCTCT-3′ | 285 |

| Osx | NM_130458.3 | 5′-GATGGCGTCCTCTCTGCTT-3′ | 5′-CGTATGGCTTCTTTGTGCCT-3′ | 146 |

| PPARγ | NM_011146.3 | 5′-CGCTGATGCACTGCCTATGA-3′ | 5′-AGAGGTCCACAGAGCTGATTCC-3′ | 100 |

| PTHR | NM_011199.2 | 5′-ACTCCTTCCAGGGATTTTTTGTT-3′ | 5′-GAAGTCCAATGCCAGTGTCCA-3′ | 106 |

| RANKL | NM_011613.3 | 5′-GCTCCGAGCTGGTGAAGAAA-3′ | 5′-CCCCAAAGTACGTCGCATCT-3′ | 83 |

| RunX2 | NM_001145920.1 | 5′-ATGATGACACTGCCACCTCTGAC-3′ | 5′-ACTGCCTGGGGTCTGAAAAAGG-3′ | 105 |

| TRAP | NM_001102405.1 | 5′-CACGAGAGTCCTGCTTGTC-3′ | 5′-AGTTGGTGTGGGCATACTTC-3′ | 174 |

Statistics

Unless stated, the data are the means ± S.D., and n is the number of independent experiments. Multiple comparisons were evaluated by analysis of variance with post-test repeated measures analyzed by Duncan or Bonferroni tests. Differences of p ≤ 0.05 are reported as significant.

RESULTS

NHERF1 Is Expressed by Mineralizing Osteoblasts

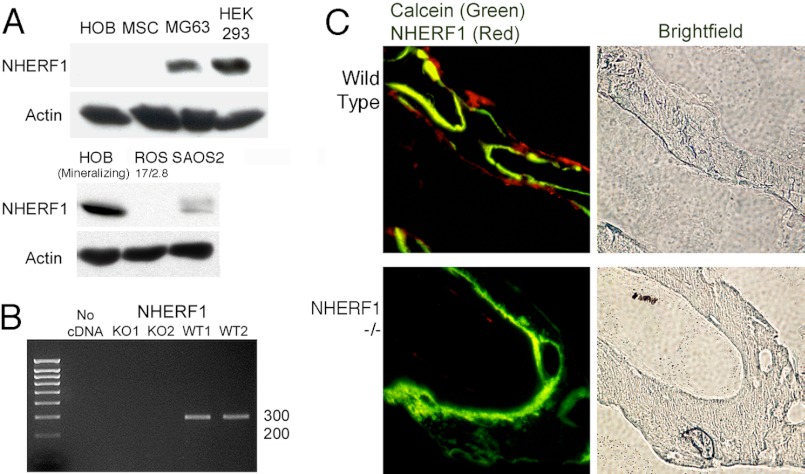

Although growing but nonmineralizing human osteoblast cell cultures and mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) expressed little NHERF1, mineralizing human osteoblast expressed abundant protein (Fig. 1A). NHERF1 protein expression in osteoblast-like osteosarcoma cells was variable, with measureable amounts in MG63 (human) or SAOS2 (human) cells, but absent in ROS 17/2.8 (rat). In whole bone mRNA from wild-type mice, NHERF1 mRNA was confirmed by PCR (Fig. 1B), and NHERF1 mRNA was also present in human osteoblasts (not shown). The strong NHE expression associated with mineralizing osteoblasts (13) suggested that NHERF1 expression might be concentrated in the single cell layer at the bone surface that mediates matrix production. Anti-NHERF1 labeling of vertebral bone supported this hypothesis (Fig. 1C). Osteoblasts in NHERF1-null mice displayed no labeling.

FIGURE 1.

Expression of NHERF1 in osteoblasts. A, Western blots of cell lysates of osteoblasts and osteoblast-like cells probed with antibodies to NHERF1. Proliferating human osteoblasts (HOB), MSCs, MG63 osteosarcoma, human embryonic kidney cells, HEK 293 cells (positive control), mineralizing human osteoblasts, rat osteosarcoma 17/2.8 cells, ROS 17/2.8 cells, and SAOS2 osteosarcoma cells were used. In the normal osteoblasts, only mineralizing cultures expressed significant NHERF1. Actin loading controls are shown for each blot. B, PCRs showing NHERF1 amplified from total RNA isolated from whole bone marrow cells of NHERF1-null (left two lanes, negative) and wild-type (right two lanes, positive) mice. C, fluorescent immune labeling of NHERF1 in wild-type and NHERF1-null mouse lumbar vertebrae. Frozen sections were labeled with rabbit anti-NHERF1 and secondary donkey anti-rabbit cy3 (red). The photographs show NHERF1 (red) overlaid with calcein (green) to indicate regions of active bone formation. Bright field images (right panels) of the same areas show the bone. Expression of NHERF1 is restricted to the surface layer of bone cells. The fields are 400 μm across.

Growth, Serum Parameters, Bone Turnover, and Quality

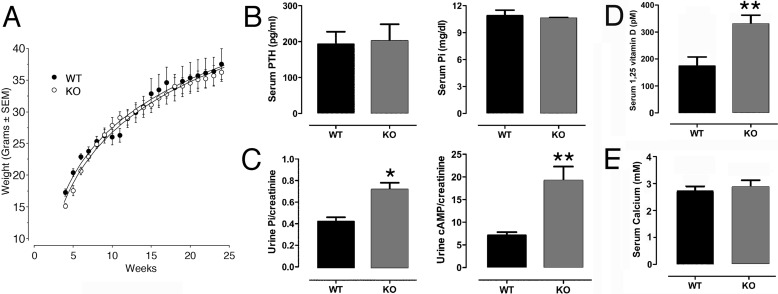

NHERF1 wild-type and knock-out animals were fed a phosphate-rich growth and reproduction diet (“Experimental Procedures”), which maintained normal growth, serum phosphorus, and PTH levels that were indistinguishable from wild-type mice (Fig. 2, A and B). Renal phosphate excretion increased in NHERF1-null mice (Fig. 2C), in keeping with published work (11), consistent with NHERF1 regulating sodium phosphate cotransporter 2a membrane retention and phosphate reabsorption (23). We further found that urinary cAMP excretion, a reflection of the phosphaturic action of PTH, also increased in NHERF1-null mice (Fig. 2C), suggesting enhanced cAMP-medicated PTH signaling in NHERF1-null mice. 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D (calcitriol) levels were nearly double (p < 0.01) in NHERF1-null mice despite normal PTH (Fig. 2D). This is likely to reflect the potentiation of PTH signaling in up-regulating 1α-hydroxylase gene transcription in kidney. Notably, these results indicate that the changes in bone cannot be due to suppressed 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, as in rickets. In keeping with equivalent serum phosphate between wild type and knock-out, serum calcium was the same in the wild-type and knock-out animals (Fig. 2E).

FIGURE 2.

Weight, PTH, phosphorus, 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, and calcium in NHERF1-null and wild-type animals on a phosphate-supplemented diet. A, weights of knock-out and wild-type mice. Differences were indistinguishable in animals over 6 weeks old. The reason for lower body mass at 4–6 weeks is not known, although young NHERF1-null mice often died of causes unrelated to bone or kidney. To avoid variability caused by early mortality, the mice were studied at 20–24 weeks. Males only are shown to reduce intra-group variability. n = 5–7, means ± S.D. B, serum PTH and phosphorus were comparable in two-month-old knock-out and wild-type animals on the diet supplemented with phosphorus. n = 5, means ± S.D. C, phosphate and cAMP were measured in random urine samples. The measurements are normalized to creatinine to compensate for urine output difference. The NHERF1-null animals had increased renal phosphate excretion (*, p < 0.05) and increased cAMP excretion (**, p < 0.01). n = 5, means ± S.D. D, serum 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D levels were significantly higher in NHERF1-null animals than those in wild-type animals (p < 0.01). n = 4–6, means ± S.D. E, serum calcium did not vary meaningfully between NHERF1-null and wild-type animals.

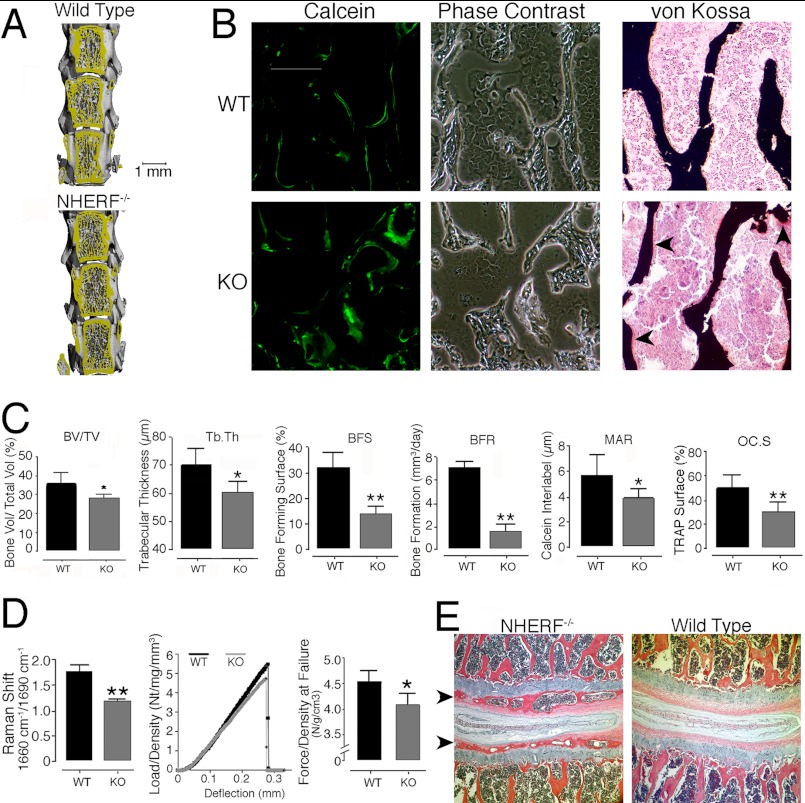

Vertebral bodies consist mostly of trabecular bone. Changes in bone density measured by microcomputed tomography (μCT) were small (Fig. 3 and Table 2); bone mineral density was not significantly different in wild-type and NHERF1-null mice. Trabecular bone in NHERF1-null mice had moderately decreased bone volume/total volume (18%), and NHERF1-null mice exhibited decreased trabecular thickness (9%), consistent with microarchitectural differences. In contrast, dynamic bone turnover studies showed large differences between wild-type and NHERF1-null mice. Sections of vertebral bone in NHERF1-null mice displayed highly unusual diffuse and slow mineral deposition, manifested as thick lines of calcein labeling. Labels at 5-day intervals were not clearly separated (Fig. 3B). Wild-type bone showed a thin and distinct mineralization front, consistent with normal bone growth. Broad calcein labels occur in severe osteomalacia, but bone with thick calcein labels mineralized completely, as shown by silver stains and verified by μCT. The data shown in Fig. 3 and Table 2 are from 25-week-old mice; to determine whether larger differences might occur in mice growing more rapidly, μCT was also performed in wild-type and NHERF-1-null mice at 10 weeks of age. Differences in trabecular thickness, trabecular number, and trabecular spacing in NHERF1 KO mice as compared with WT mice were essentially identical in 10- and 25-week-old mice (not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Changes in bone formation in NHERF1-null mice. A, μCT of lumbar vertebrae 2–4 of wild-type and NHERF1-null mice. Changes were minor on direct visual analysis, but quantitative differences were measureable, as described below. B, broad mineralization fronts by calcein labeling of bone formation (green, left column) in the knock-out mouse. The trabecular bone, in keeping with the μCT, was similar in wild-type and NHERF1-null mice. Note that the trabecular bone of the knock-out mouse bone was irregular in a manner difficult to quantify (bright field, middle column). Staining of mineralized and unmineralized bone with silver nitrate and fast red (right column) in NHERF1-null and wild-type lumbar vertebrae showed more unmineralized bone (red areas on bone surfaces, arrows; mineral is black) in the knock-out, although the total amount of nonmineralized bone was in all cases small. Each frame is 400 μm across. C, bone characterization by μCT and dynamic histomorphometry. Comparison of several animals showed decreased bone volume per total volume (BV/TV, 18%, p < 0.05) and trabecular thickness (9%, p < 0.05), but bone density was not significantly different (Table 2). Dynamic histomorphometry showed decreased bone-forming surface (BFS), bone forming rate (BFR), interlabel distance, and resorptive surface in NHERF1-null mice. The values are the means ± S.D. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01. D, bone quality. Infrared Raman spectroscopy ratio of emission signal at 1660 cm−1/1690 cm−1 (left graph), which reflects collagen cross-linking (see text), was averaged over 16 scans, representing four samples of each type each scanned four times with the specimen rotated 90° between scans. The values are the means ± S.E. **, p < 0.01. Load versus deflection curves of wild-type and NHERF1-null humerus in three-point bone bending (middle graph). To avoid artifacts caused by differences in bone density, the stiffness and force at breaking deflection were normalized to density. A typical curve from five paired comparisons is shown. The most consistent data were at the maximum force, which was evaluated for five pairs of wild-type and knock-out animals; these data are plotted in the right graph, with maximum force at breaking point of wild-type and NHERF1-null humerus. The data are from 10 animals in three litters of mice, five wild-type and five NHERF1-null. n = 5, means ± S.E. *, p = 0.05. E, end plate cartilage mineralization in NHERF1-null animals. Hematoxylin- and eosin-stained decalcified sections are shown, with bone forming in the end plates indicated by arrowheads (left panel). End plate mineralization occurred consistently in the knock-out but was not seen in the controls at 5–6 months. The fields are centered on intervertebral discs and are 1.0 mm across.

TABLE 2.

Static and dynamic histomorphometry of wild-type and NHERF1−/− bone

The vertebral trabecular bones from 25-week-old mice were analyzed by μCT and dynamic histomorphometry. Bone mineral density, total volume, bone volume, trabecular number, trabecular thickness, and trabecular spacing are from μCT. Bone forming surface, interlabel distance, resorptive surface, and bone formation rate are from dynamic histomorphometry. The values are the means ± S.D.

| Wild-type | NHERF1−/− | |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 6) | (n = 7) | |

| Bone mineral density (mg/cm2) | 652 ± 24 | 647 ± 29 |

| Total volume (mm3) | 1.12 ± 0.72 | 0.79 ± 0.14 |

| Bone volume (mm3) | 0.36 ± 0.22 | 0.22 ± 0.04 |

| Bone volume/total volume | 0.34 ± 0.07 | 0.28 ± 0.02a |

| Trabecular number (1/mm) | 5.96 ± 0.67 | 5.93 ± 0.33 |

| Trabecular thickness (mm) | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.04a |

| Trabecular spacing (mm) | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 0.16 ± 0.01 |

| Bone forming surface (% of total surface) | 32 ± 6 | 14 ± 3b |

| Interlabel distance (μm) | 5.62 ± 1.67 | 3.86 ± 0.82a |

| Resorptive surface (%) | 0.50 ± 0.11 | 0.30 ± 0.08b |

| Bone formation rate (μm3/day) | 7.06 ± 0.52 | 1.64 ± 0.58b |

a p < 0.05.

b p < 0.01.

Incomplete mineralization, determined by residual matrix (osteoid), was detected on surfaces of NHERF1-null bones but not those of wild-type mice (Fig. 3B, right panels). These findings are consistent with delayed mineralization with mild osteomalacia in the phosphate-supplemented animals. Quantitative analysis (Fig. 3C) revealed reduced bone-forming surface (56%) and reduced bone formation rate (77%) in the NHERF1-null mice. Calcein interlabel distance, a measure of the vectorial bone forming rate, decreased 31% in NHERF1-null mice (p < 0.05). The overall changes in mineral deposition were consistent with dysfunctional osteoblast bone synthesis. In accord with osteoblast dysfunction, resorptive surface per bone surface decreased by 40% in NHERF1-null mice (p < 0.01), consistent with reduced osteoclast activity. Given that overall bone mass was unchanged, these alterations indicate that coupling between bone formation and resorption was maintained in the knock-out mice. Together, these data indicate that NHERF1-null bone exhibits disordered mineralization with slightly atypical microarchitecture but essentially normal overall density.

We next studied bone quality. Collagen cross-linking, determined by near infrared Raman spectroscopy, decreased by 32% in femoral bone of NHERF1-null bone compared with that of wild-type mice (Fig. 3D, p < 0.01). The consequences of this on strength were measured by three-point bone bending performed on isolated humeri. Stiffness (n/mm) trended lower by ∼25% for NHERF1-null bone compared with wild-type mice, but the difference did not reach significance. In contrast, the force at fracture (n) was reduced by a similar amount in the knock-out (n = 5; p = 0.05).

Cartilage Mineralization in NHERF1-null Mice

The top and the bottom of each vertebra are capped with a thin cartilaginous pad called the end plate, which is not normally mineralized. Strikingly, vertebral end plates were mineralized in NHERF1-null mice but not in the wild-type mice (Fig. 3E). Pathological end plate mineralization occurs sporadically with trauma or age (24). However, it was present in virtually all knock-out vertebral end plates at 6 months of age, but not in wild-type littermates.

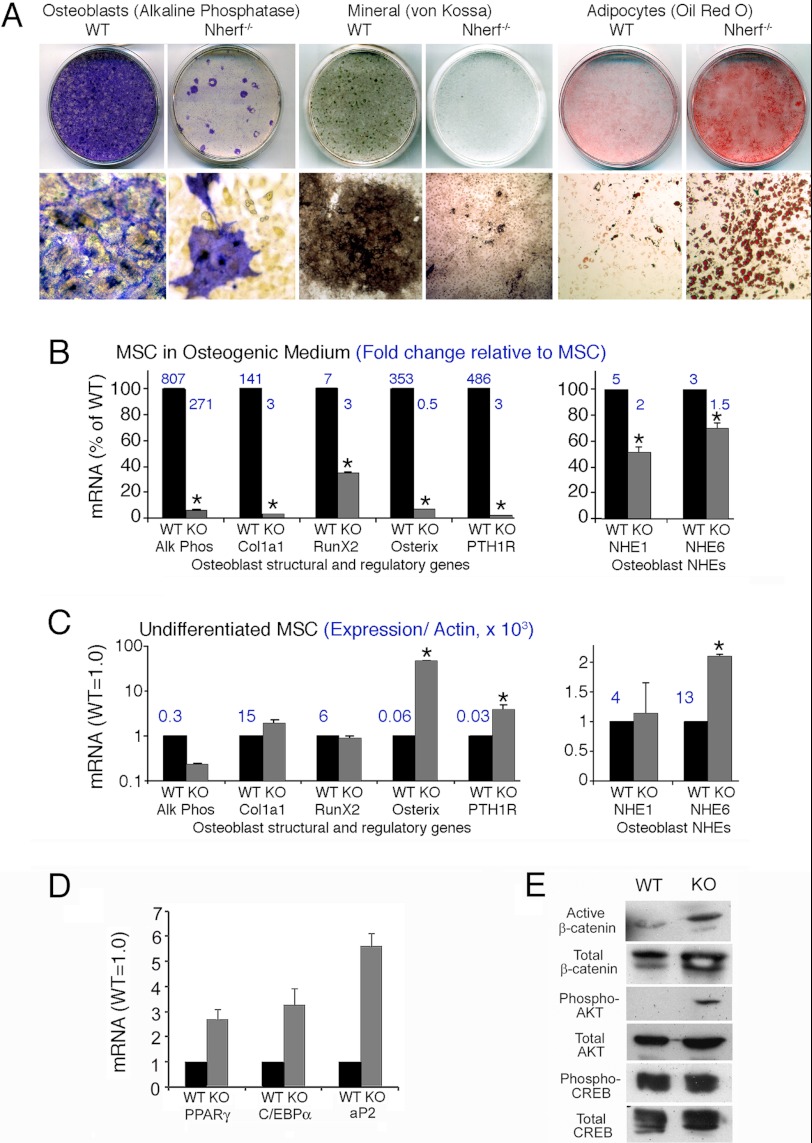

Role of NHERF1 in Mesenchymal Stem Cell Differentiation

We theorized that reduced bone formation and mineralization results from an intrinsic defect of osteoblastic differentiation. To test this idea, MSCs were isolated and grown in vitro under differentiating conditions. Wild-type MSCs differentiated into osteoblasts normally as demonstrated by alkaline phosphatase activity and silver staining of mineral (Fig. 4A). Osteoblast differentiation of NHERF1-null MSCs was impaired, with only focal groups of cells expressing alkaline phosphatase and greatly reduced mineral deposition. To address the pitfall that this might reflect high glucose (25 mm) in the DMEM-based medium used, it was repeated in media with 5 mm glucose, with the same result (not illustrated). In osteoblast differentiation medium, many NHERF1-null cells ultimately differentiated into adipocytes, whereas wild-type cells showed only rare stochastic adipocyte differentiation (Oil Red O; Fig. 4A, right frames). Thus, NHERF1-null stem cells have an intrinsic defect in osteoblast formation that is accompanied by increased adipocyte differentiation.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of NHERF1 knock-out on osteoblast differentiation from MSCs. A, osteoblast differentiation of bone marrow-derived MSCs from wild-type and NHERF1-null mice. MSCs were isolated and induced to differentiate into osteoblasts using ascorbic acid, glycerol-2-phosphate, and hydrocortisone (“Experimental Procedures”). At 4 weeks after induction, alkaline phosphatase activity, silver stain for mineral (von Kossa), and Oil Red O stain for adipocytes were performed. Top row, whole culture dishes, 2.5 cm across. Bottom row, photomicrographs of 400-μm-wide fields. Alkaline phosphatase and mineral were greatly reduced in differentiation of knock-out cells, whereas knock-out cells spontaneously differentiated into adipocytes at a much higher rate. B, wild-type (black bars) and NHERF1-null (gray bars) MSCs were maintained 4 weeks in osteoblast differentiation medium. Then mRNA was harvested, and quantitative PCR analysis of osteoblast-expressed genes (left panel) and NHEs (right panel) was performed. The data were presented as expression levels in NHERF1-null relative to wild type (left bar of each pair) that is in each case normalized to 100%. The numbers above the bars are the fold increase in differentiated cells over undifferentiated MSCs of the same type. n = 2 mean ± range. *, p < 0.05. Similar results were obtained in a duplicate assay. C, quantitative PCR analysis of osteoblast and NHE genes as in B but using MSCs in proliferation medium (i.e., no ascorbate or glycerol-2-phosphate). The data were presented as fold differences of NHERF1-null (right bars, gray) relative to wild-type cells normalized to 1 (left bars, black). The y axis of the left panel is log scale. The numbers above the bars represent absolute expression relative to β-actin × 1000. n = 2 mean ± range. *, p < 0.05. Repeat assays (not shown) gave consistent results. D, quantitative PCR analysis of adipogenic transcription factors and adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein (aP2) in differentiated wild-type and NHERF1-null MSCs treated as in B. The data are presented as fold differences of NHERF1-null (gray bars) relative to wild-type cells normalized to 1 (black bars). The numbers above the bars are absolute expression relative to β-actin × 1000. n = 2 mean ± range. *, p < 0.05. E, cell lysate was collected from wild-type and NHERF1-null MSCs incubated in osteoblast differentiation medium for 4 weeks. Western blots for active β-catenin, total β-catenin, phospho-Akt, total Akt, phosphor-CREB, and total CREB were performed.

All measured osteoblast transcription factors and osteoblast characteristic marker genes studied were reduced significantly at 4 weeks of culture in the knock-out cells (p < 0.05). Osteoblast marker mRNAs alkaline phosphatase and collagen I1 (Col1a) were up-regulated during differentiation (Fig. 4B), but alkaline phosphatase and Col1a were 15 and 30 times higher in wild-type cultures than in NHERF1-null osteoblast cultures, respectively. RunX2 and osterix (Osx), key transcription factors regulating osteoblast differentiation, increased 7-fold in wild-type cells but only 2.8-fold in NHERF1-null cells (p < 0.01). Osx mRNA increased 300-fold during differentiation in wild-type cells but decreased 45% in NHERF1-null cells relative to growing cells. In differentiated MSCs, RunX2 and Osx expression levels were 3 and 14 times higher (p < 0.01) in wild-type cells than that in NHERF1-null cells, respectively. NHERF1 binds PTHR and regulates PTHR membrane retention (6–8). Therefore, we examined PTHR expression in wild-type and NHERF-null cells. PTHR mRNA increased 400-fold (p < 0.005) during osteoblastic differentiation of wild-type MSCs but increased only 3.4 times in NHERF1-null MSCs. Increased PTHR mRNA expression may reflect the smaller proportion of knock-out cells that can be induced to form osteoblasts in vitro. Consistent with the increased adipocyte differentiation observed in NHERF1-null cells, adipogenic transcription factors peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ and CCAAT enhancer-binding protein α mRNA expression in differentiated NHERF1-null MSC were 2.7 and 3.3 times higher than that of the wild-type cells, respectively (p < 0.05). Adipocyte marker gene, adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein-2 (aP2), expression was 5.6 times higher than that of the wild-type cells (p < 0.01) (Fig. 4D).

Because mineralization was delayed (Fig. 3) and because mineralization is supported by acid excretion mediated by Na+/H+ exchange (13), we examined NHE1 and NHE6. NHE1 and NHE6 were up-regulated during differentiation in both wild-type and knock-out cells. (Fig. 4B, right panel) but were 2 and 1.4 times higher, respectively, in wild-type cells than in NHERF1-null derived cells (p < 0.05).

In growing, nondifferentiated MSC, changes in the knock-out cells were smaller, and only differences in osterix, the PTH receptor, and NHE6 were significant (p < 0.05). Alkaline phosphatase expression in wild-type MSCs was 4.6 times higher than that in NHERF1-null cells (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4C), consistent with spontaneous osteoblast differentiation that occurs in a small fraction of cells in normal MSC. Type I collagen expression was not measurably affected, which may be due to the small number of osteoblasts. RunX2 mRNA was similar in growing wild-type and NHERF1-null cells before differentiation. Osx expression, however, increased 48-fold in the NHERF1-null cells (p < 0.02), although Osx expression in the NHERF1-null cells still was 7 times lower (p < 0.05) than in differentiating wild-type osteoblasts. A similar effect was seen with the PTHR, where the NHERF1-null cells expressed 3.6 times more than the wild-type cells (p < 0.01). The mechanism responsible for increased Osx and PTHR abundance in the NHERF1-null MSC, which otherwise were resistant to osteoblastic differentiation, is unknown.

PTH is known to act through Wnt/β-catenin, Akt phosphorylation, or PKA-induced phosphorylation of CREB to regulate osteoblast activity and bone formation (25, 26). We found that protein levels of active β-catenin and phospho-Akt (Ser-473) in differentiated NHERF1-null MSC cells were markedly elevated than that in the wild-type cells (Fig. 4E). In contrast, CREB phosphorylation (Ser-133) was comparable in wild-type and NHERF1-null differentiated MSC cells (Fig. 4E). These results indicate that NHERF1 regulates osteoblast differentiation through enhancing β-catenin and Akt activation but without affecting CREB activation (see “Discussion”).

Role of NHERF1 in Osteoclast Differentiation

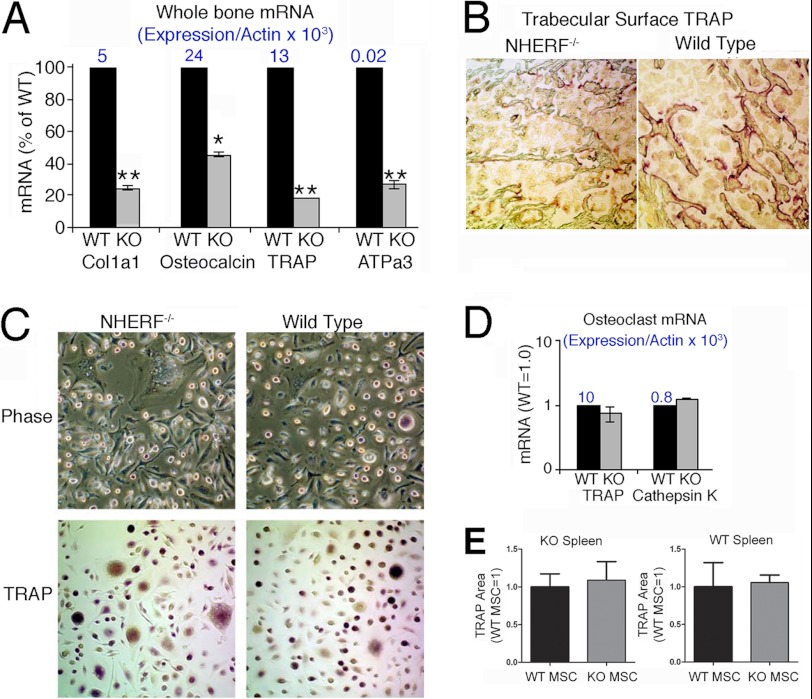

Analysis of osteoblast- and osteoclast-specific transcripts in whole bone mRNA confirmed reduced osteoblast and osteoclast function in NHERF1-null mice. Col1a1, osteocalcin, and osteoclast-specific TRAP and the H+-ATPase subunit ATPa3 decreased (p < 0.01) in NHERF1-null whole bone mRNA compared with wild type (Fig. 5A). TRAP labeling of vertebral bone confirmed these results, with greater abundance (p < 0.01) of TRAP expressing-cells in wild-type bone than in NHERF1-null bone (Fig. 5B), thus establishing that NHERF1-null mice have reduced osteoclast activity in vivo.

FIGURE 5.

Bone cell mRNA in whole bone marrow is consistent with a bone formation defect, but spleen monocyte differentiation into osteoclasts is unaffected by NHERF knock-out. A, real time PCR analysis of osteoclast and osteoblast genes in mRNA harvested from whole bone of wild-type and NHERF1-null animals. Both osteoblast markers (Col1a1 and osteocalcin) and osteoclast markers (TRAP and ATPa3) are reduced significantly in the knock-out animal. Two assays of duplicate cultures gave similar results; one set is shown. n = 2, mean ± range. *, p < 0.05. N is shown above bars: expression relative to β-actin. B, TRAP activity in trabecular bone of wild-type and NHERF1-null mouse vertebral bone frozen sections. The knock-out animals had consistently less TRAP surface (Table 1). C, spleen cells were collected from wild-type and NHERF1-null mice and cultured in macrophage CSF and RANKL to induce osteoclast differentiation. TRAP activity in situ was labeled in cell cultures at day 14. No differences were apparent. D, real time PCR analysis of genes expressed in osteoclasts from cultures as in C. Each pair is normalized to the wild type (left bars). The numbers above the bars are expression relative to β-actin. n = 2, mean ± range. Although there was variability, no change relative to wild type was seen. E, TRAP-labeled cell area in co-cultures of NHERF1-null (KO, left graph) or WT (right graph) spleen cells supported by wild-type or knock-out mesenchymal stem cells. The area of TRAP label was quantified by hue, saturation, and intensity separation (“Experimental Procedures”) and is presented as fraction of the WT MSC result in each case.

Osteoclast differentiation of splenic macrophages by RANKL and CSF treatment was similar by TRAP staining in wild-type and NHERF1-null cells (Fig. 5C). Likewise, TRAP and cathepsin K mRNA levels were indistinguishable. Thus, diminished osteoclast differentiation in vivo is not inherently due to a general absence of NHERF1.

To confirm further that the reduced osteoclast activity in vivo was due to the deficient osteoblast activity, co-culture of bone marrow MSC and spleen cells was performed. This showed that TRAP-labeled spleen cells, either knock-out or wild-type cells, were induced to produce the same TRAP activity in osteoclasts with wild-type or knock-out MSC (Fig. 5E).

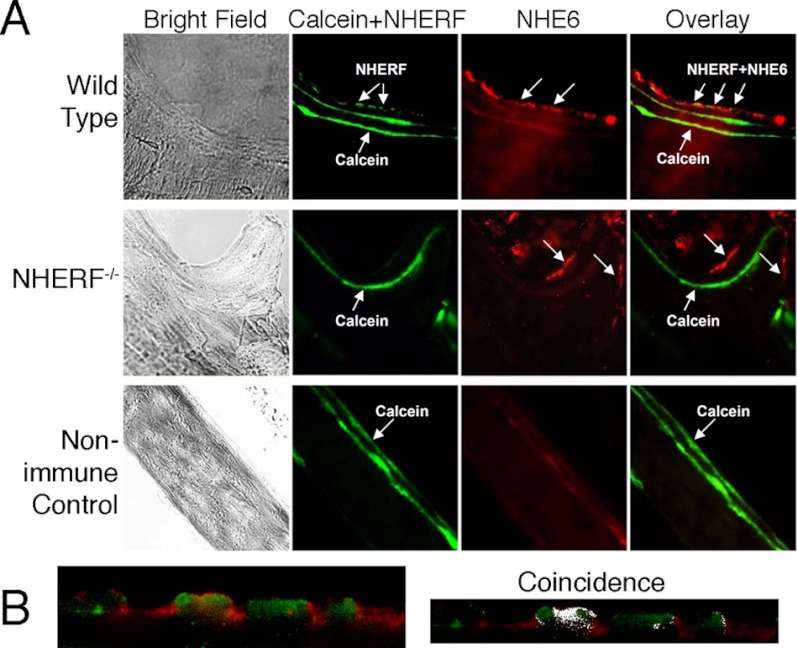

NHERF1 and Na+/H+ Exchange

Because NHERF1 regulates Na+/H+ exchange, we examined NHERF1 co-localization with Na+/H+ exchangers in bone (Fig. 6A). NHERF1 (green) and NHE6 (red) were expressed on the basolateral surfaces of mineralizing osteoblasts in sections of wild-type and NHERF1-null vertebrae at sites of active mineralization. NHERF1 and NHE6 labeling occurred in clusters with ∼5% overlap (Fig. 6B). NHE6 was labeled at mineralizing vertebral surfaces of knock-out mice. To determine whether the absence of NHERF1 causes dysregulation of intracellular pH, we measured the intracellular pH (pHi) of mineralizing osteoblasts grown from MSC in osteogenic medium as in a previous work (13). NHERF1-null osteoblasts displayed a slightly but significantly (p < 0.01) higher resting pHi (6.85 versus 6.60), and pH change in response to 40 mm acetate load was much larger (0.48 pH unit) in wild-type cells than in knock-out cells (0.14 pH unit) (p < 0.01).

FIGURE 6.

NHERF and NHE6 localization in mouse bone. A, the top row shows NHERF1 (green) and NHE6 (red) distribution in bone lining cells (arrows) of frozen sections of using wild-type vertebrae. Calcein labeling to identify regions of active bone formation at the mineralizing surface was also shown (strong linear green signal within the bone). The middle row shows results from knock-out bone. As expected, there is no NHERF1 label associated with the calcein label; NHE6 is still seen in bone lining cells (arrows). Negative controls (bottom row) were performed omitting the primary antibodies using wild-type bone. Here, only the calcein label is seen. The fields shown are 120 μm across. B, distribution of NHE6 and NHERF1 in active osteoblasts. The left panel shows cells of the active osteoblast surface layer in a region over calcein binding, at the highest magnification, after labeling for NHE6 (red) and NHERF1 (green). The field shown is 65 μm wide. The two proteins occur in alternating patches with negligible overlap by coincidence analysis (right panel). The Pearson correlation coefficient, 0.45, was indeterminant for co-localization in the sample used. Labeling with NHE1 and NHERF gave similar results (not shown).

DISCUSSION

Because NHE mediates acid elimination in mineralizing osteoblasts (13) and renal phosphate wasting per se is insufficient to account for the bone phenotype of NHERF1-deficient mice or of humans harboring NHERF1 mutations, we hypothesized that NHERF1 directly regulates bone mineralization. Although described in osteoclasts (27), NHERF1 expression was not previously shown to occur in primary osteoblasts that produce bone matrix. We now show that NHERF1 is prominently expressed in osteoblasts that mediate matrix production (Fig. 1). To avoid potentially confounding effects of renal phosphate wasting on bone (11, 14), mice were fed a phosphate-rich diet. In this setting, bone formation rate was dramatically reduced in NHERF1-null mice under conditions where serum phosphorous, calcium, and PTH were normal (Fig. 2, B–D). Bone resorption was proportionately reduced, compensating for the diminished synthesis, thereby resulting in a negligible change of overall bone mineral density of NHERF1-null mice. This may account for the previous failure to appreciate an important role of NHERF1 on bone. Thus, bone formation and resorption remain well coupled even in the presence of significant distortions of the structure and size of the mineralizing surface. The primary consequence of NHERF1 deficiency was a major decrease in the bone-forming surface and bone-forming rate in NHERF1-null mice (Fig. 3 and Table 2). Wide mineralization fronts in NHERF1-null bone indicate disordered or delayed mineralization. However, mineralization ultimately was complete in areas with wide calcein labels, and only vestiges of unmineralized osteoid were found at trabecular surfaces of NHERF1-null bone. The absolute quantity of osteoid in NHERF1-null bone was small, less than 1% of overall matrix cross-sectional area, unlike rickets or renal osteomalacia, where large amounts of unmineralized osteoid, on the order of 10–50% of cross-sectional area, occur (28). Analysis of mRNA extracted from medullary bone of wild-type and NHERF1-null animals showed decreases in both osteoblast and osteoclast-specific mRNAs in the knock-out animals. This is consistent with the reduced osteoblast and osteoclast activity in NHERF1-null bone relative to the wild type seen by dynamic histomorphometry.

Compromised bone formation in NHERF1-null animals would be expected to affect bone quality. Impaired collagen cross-linking is a feature of bone in type I collagen defects as occurs in osteogenesis imperfect (29), and in senile osteoporosis, both collagen cross-linking and mineralization defects occur (30, 31). Bone quality was significantly reduced in NHERF1-null bone (Fig. 3E). Bone stiffness and breaking strength were reduced by 25%, even though changes in overall bone mass were minor. Mineralization was impaired, as was collagen cross-linking. In conditions such as low turnover osteoporosis, mineral deposition occurs in narrow bands, whereas the disordered mineralization seen here distinguishes the effect of NHERF1 loss from osteoporosis. Impaired degradation may also affect bone quality. In pycnodysostosis (cathepsin K deficiency) (32) and treatment with bisphosphonates, which inhibit matrix binding, bone mass increases but quality is impaired (33). However, in NHERF1 deficiency, osteoclasts produced in vitro were normal (Fig. 5, C and D), and cRNA screening detected only background NHERF1 expression in osteoclasts or CD14-positive cells (not shown), so it is likely that disordered bone synthesis was primarily responsible for reduced bone quality.

Bone cell differentiation in vitro showed that differences in osteoblast differentiation and matrix synthesis are intrinsic to the MSC, and independent of effects of NHERF1 activity in other organs (11, 14). MSC from NHERF1-null mice grown in osteogenic media had reduced osteoblast transcription factors and matrix proteins and mineralized poorly. Qualitative defects in osteoblast differentiation from MSC previously have been described in telomerase deficiency (34), when TNF alpha is pathologically high (35), or if TGFβ and related proteins are suppressed (36). The NHERF1-null effect is the first example of a membrane regulatory protein defect that has similar consequences. Several independent pathways presumably contribute to the dysregulation of NHERF1-null bone. PTHR was greatly decreased in NHERF1-null cells (Fig. 4). PTHR signaling is regulated by NHERF1 (6–8), and PTH and the PTH-related protein regulate osteoblast proliferation and differentiation (10). Thus, altered PTHR signaling is considered to be a central component of the mechanism for the greatly decreased osteoblast differentiation from MSCs in the NHERF1-null.

Expression of NHE1 and NHE6 that function in osteoblasts were reduced in NHERF1-null MSC in osteogenic medium (Fig. 4B). However, NHERF1-null osteoblasts display a higher resting pHi and a smaller pHi change after acid load—seemingly a stronger, uncontrolled Na+/H+ exchange. This is consistent with the role of NHERF1 in mediating cAMP-induced NHE3 inhibition in fibroblasts (37). Such decreased expression and uncontrolled, excessive activity of Na+/H+ exchanger may not support the spatial and temporal need for proton transport for normal bone mineral deposition. Interestingly, NHE6 and NHERF1 showed that the two proteins had distinct localizations (Fig. 6B). This distribution in no way argues against a regulatory interaction, because NHERF1 interactions are transient, low affinity, and dynamic, assembling and disassembling with a t½ of ∼1–5 min (38). Because NHEs remove acid produced during bone mineral deposition (13), altered NHE activity presumably contributes to the characteristic mineral deposition pattern with wide calcein labels and to the reduced overall mineral apposition rate.

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway plays a pivotal role in osteoblast differentiation and maturation from MSCs (39), and PTH increases the β-catenin level in osteoblasts (40). Interestingly, active β-catenin increased markedly in NHERF1-null MSC cells (Fig. 4E). This is contrary to the view that Wnt/β-catenin positively regulates osteoblast differentiation but is consistent with a recent report that NHERF1 expression negatively correlates with active β-catenin in breast epithelium (41). This might reflect the difference between Wnt-dependent β-catenin activation and PTH-dependent β-catenin activation, which elicit opposite actions on osteoclastogenesis (42). PTH stimulates Akt activation, which promotes the Wnt/β-catenin pathway by stabilizing β-catenin (43). Similarly, Akt phosphorylation is obvious in NHERF1-null MSCs but not detected in wild-type MSCs (Fig. 4E). This is in keeping with a previous report that Akt phosphorylation induced by PDGF is prolonged in NHERF1-null mouse embryonic fibroblasts (44).

Taken together, our results support a function of NHERF1 as a molecular brake that restricts PTH signaling. NHERF1-null osteoblasts display enhanced PTH signaling, with overactivated Akt and β-catenin, which leads to impaired osteoblast differentiation. Because PTH activates cAMP production, we examined cAMP excretion and CREB phosphorylation in NHERF1-null mice and MSCs. Although urine cAMP from NHERF1-null mice increases significantly compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 2C), CREB phosphorylation is comparable between wild-type and NHERF1-null MSC cells (Fig. 4E), suggesting that NHERF1 does not regulate CREB phosphorylation in osteoblasts.

In conclusion, NHERF1 deficiency causes a bone formation defect. Abnormal osteoblast function results in delayed mineralization and matrix maturation in vivo. NHERF1-null bone has moderately abnormal mechanical properties. NHERF1-deficient MSCs exhibit compromised osteoblast differentiation and mineralization. The effect of NHERF1 in bone development reflects abnormal PTH signaling and uncontrolled Na+/H+ transport. However, coupling of bone resorption to formation is maintained in NHERF1-null mice, so that bone density is nearly normal.

Acknowledgment

We thank Yanmei Yang for performing NHERF1 Western blots.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants AR053976, DK069998, and AR055208. This work was also supported by the Department of Veteran's Affairs.

- NHERF

- Na+-H+ exchanger regulatory factor

- NHE

- Na+-H+ exchanger

- PTH

- parathyroid hormone

- PTHR

- PTH receptor

- MSC

- mesenchymal stem cell

- μCT

- microcomputed tomography

- TRAP

- tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase

- CSF

- colony-stimulating factor

- Osx

- osterix

- CREB

- cAMP response element binding protein

- RANKL

- receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand.

REFERENCES

- 1. Blair H. C., Robinson L. J., Huang C. L., Sun L., Friedman P. A., Schlesinger P. H., Zaidi M. (2011) Calcium and bone disease. Biofactors 37, 159–167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Feng X., McDonald J. M. (2011) Disorders of bone remodeling. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 6, 121–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weinman E. J., Hall R. A., Friedman P. A., Liu-Chen L. Y., Shenolikar S. (2006) The association of NHERF adaptor proteins with G protein-coupled receptors and receptor tyrosine kinases. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 68, 491–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shenolikar S., Voltz J. W., Cunningham R., Weinman E. J. (2004) Regulation of ion transport by the NHERF family of PDZ proteins. Physiology 19, 362–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Weinman E. J., Steplock D., Shenolikar S. (1993) CAMP-mediated inhibition of the renal brush border membrane Na+-H+ exchanger requires a dissociable phosphoprotein cofactor. J. Clin. Invest. 92, 1781–1786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang B., Bisello A., Yang Y., Romero G. G., Friedman P. A. (2007) NHERF1 regulates parathyroid hormone receptor membrane retention without affecting recycling. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 36214–36222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang B., Yang Y., Abou-Samra A. B., Friedman P. A. (2009) NHERF1 regulates parathyroid hormone receptor desensitization. Interference with β-arrestin binding. Mol. Pharmacol. 75, 1189–1197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wheeler D., Sneddon W. B., Wang B., Friedman P. A., Romero G. (2007) NHERF-1 and the cytoskeleton regulate the traffic and membrane dynamics of G protein-coupled receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 25076–25087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mannstadt M., Jüppner H., Gardella T. J. (1999) Receptors for PTH and PTHrP. Their biological importance and functional properties. Am. J. Physiol. 277, F665–F675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Datta N. S., Abou-Samra A. B. (2009) PTH and PTHrP signaling in osteoblasts. Cell Signal. 21, 1245–1254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shenolikar S., Voltz J. W., Minkoff C. M., Wade J. B., Weinman E. J. (2002) Targeted disruption of the mouse NHERF-1 gene promotes internalization of proximal tubule sodium-phosphate cotransporter type IIa and renal phosphate wasting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 11470–11475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hernando N., Déliot N., Gisler S. M., Lederer E., Weinman E. J., Biber J., Murer H. (2002) PDZ-domain interactions and apical expression of type IIa Na/Pi cotransporters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 11957–11962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu L., Schlesinger P. H., Slack N. M., Friedman P. A., Blair H. C. (2011) High capacity Na+/H+ exchange activity in mineralizing osteoblasts. J. Cell. Physiol. 226, 1702–1712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Karim Z., Gérard B., Bakouh N., Alili R., Leroy C., Beck L., Silve C., Planelles G., Urena-Torres P., Grandchamp B., Friedlander G., Prié D. (2008) NHERF1 mutations and responsiveness of renal parathyroid hormone. N. Engl. J. Med. 359, 1128–1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Beck L., Karaplis A. C., Amizuka N., Hewson A. S., Ozawa H., Tenenhouse H. S. (1998) Targeted inactivation of Npt2 in mice leads to severe renal phosphate wasting, hypercalciuria, and skeletal abnormalities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 5372–5377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gupta A., Tenenhouse H. S., Hoag H. M., Wang D., Khadeer M. A., Namba N., Feng X., Hruska K. A. (2001) Identification of the type II Na+-Pi cotransporter (Npt2) in the osteoclast and the skeletal phenotype of Npt2−/− mice. Bone 29, 467–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Prié D., Beck L., Friedlander G., Silve C. (2004) Sodium-phosphate cotransporters, nephrolithiasis and bone demineralization. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 13, 675–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mistry P. K., Liu J., Yang M., Nottoli T., McGrath J., Jain D., Zhang K., Keutzer J., Chuang W. L., Mehal W. Z., Zhao H., Lin A., Mane S., Liu X., Peng Y. Z., Li J. H., Agrawal M., Zhu L. L., Blair H. C., Robinson L. J., Iqbal J., Sun L., Zaidi M. (2010) Glucocerebrosidase gene-deficient mouse recapitulates Gaucher disease displaying cellular and molecular dysregulation beyond the macrophage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 19473–19478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Manoharan R., Wang Y., Feld M. S. (1996) Histochemical analysis of biological tissues using Raman spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 52, 215–249 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jämsä T., Jalovaara P., Peng Z., Väänänen H. K., Tuukkanen J. (1998) Comparison of three-point bending test and peripheral quantitative computed tomography analysis in the evaluation of the strength of mouse femur and tibia. Bone 23, 155–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tropel P., Noël D., Platet N., Legrand P., Benabid A. L., Berger F. (2004) Isolation and characterisation of mesenchymal stem cells from adult mouse bone marrow. Exp. Cell Res. 295, 395–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bustin S. A. (2000) Absolute quantification of mRNA using real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assays. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 25, 169–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang B., Means C. K., Yang Y., Mamonova T., Bisello A., Altschuler D. L., Scott J. D., Friedman P. A. (2012) Ezrin-anchored PKA coordinates phosphorylation-dependent disassembly of a NHERF1 ternary complex to regulate hormone-sensitive phosphate transport. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 24148–24163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Roberts S., Menage J., Eisenstein S. M. (1993) The cartilage end-plate and intervertebral disc in scoliosis. Calcification and other sequelae. J. Orthop. Res. 11, 747–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Williams B. O., Insogna K. L. (2009) Where Wnts went. The exploding field of Lrp5 and Lrp6 signaling in bone. J. Bone Miner. Res. 24, 171–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Murrills R. J., Andrews J. L., Samuel R. L., Coleburn V. E., Bhat B. M., Bhat R. A., Bex F. J., Bodine P. V. (2009) Parathyroid hormone synergizes with non-cyclic AMP pathways to activate the cyclic AMP response element. J. Cell. Biochem. 106, 887–895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Khadeer M. A., Tang Z., Tenenhouse H. S., Eiden M. V., Murer H., Hernando N., Weinman E. J., Chellaiah M. A., Gupta A. (2003) Na+-dependent phosphate transporters in the murine osteoclast. Cellular distribution and protein interactions. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 284, C1633–C1644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brownstein C. A., Zhang J., Stillman A., Ellis B., Troiano N., Adams D. J., Gundberg C. M., Lifton R. P., Carpenter T. O. (2010) Increased bone volume and correction of HYP mouse hypophosphatemia in the Klotho/HYP mouse. Endocrinology 151, 492–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hasegawa K., Kataoka K., Inoue M., Seino Y., Morishima T., Tanaka H. (2008) Impaired pyridinoline cross-link formation in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 26, 394–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fratzl-Zelman N., Roschger P., Misof B. M., Nawrot-Wawrzyniak K., Pötter-Lang S., Muschitz C., Resch H., Klaushofer K., Zwettler E. (2011) Fragility fractures in men with idiopathic osteoporosis are associated with undermineralization of the bone matrix without evidence of increased bone turnover. Calcif. Tissue Int. 88, 378–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Saito M., Fujii K., Marumo K. (2006) Degree of mineralization-related collagen crosslinking in the femoral neck cancellous bone in cases of hip fracture and controls. Calcif. Tissue Int. 79, 160–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fratzl-Zelman N., Valenta A., Roschger P., Nader A., Gelb B. D., Fratzl P., Klaushofer K. (2004) Decreased bone turnover and deterioration of bone structure in two cases of pycnodysostosis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 89, 1538–1547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Seeman E., Delmas P. D., Hanley D. A., Sellmeyer D., Cheung A. M., Shane E., Kearns A., Thomas T., Boyd S. K., Boutroy S., Bogado C., Majumdar S., Fan M., Libanati C., Zanchetta J. (2010) Microarchitectural deterioration of cortical and trabecular bone. Differing effects of denosumab and alendronate. J. Bone Miner. Res. 25, 1886–1894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Saeed H., Abdallah B. M., Ditzel N., Catala-Lehnen P., Qiu W., Amling M., Kassem M. (2011) Telomerase-deficient mice exhibit bone loss owing to defects in osteoblasts and increased osteoclastogenesis by inflammatory microenvironment. J. Bone Miner. Res. 26, 1494–1505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li B., Shi M., Li J., Zhang H., Chen B., Chen L., Gao W., Giuliani N., Zhao R. C. (2007) Elevated tumor necrosis factor-α suppresses TAZ expression and impairs osteogenic potential of Flk-1+ mesenchymal stem cells in patients with multiple myeloma. Stem Cells Dev. 16, 921–930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hosogane N., Huang Z., Rawlins B. A., Liu X., Boachie-Adjei O., Boskey A. L., Zhu W. (2010) Stromal derived factor-1 regulates bone morphogenetic protein 2-induced osteogenic differentiation of primary mesenchymal stem cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 42, 1132–1141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Weinman E. J., Steplock D., Donowitz M., Shenolikar S. (2000) NHERF associations with sodium-hydrogen exchanger isoform 3 (NHE3) and ezrin are essential for cAMP-mediated phosphorylation and inhibition of NHE3. Biochemistry 39, 6123–6129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ardura J. A., Wang B., Watkins S. C., Vilardaga J. P., Friedman P. A. (2011) Dynamic Na+-H+ exchanger regulatory factor-1 association and dissociation regulate parathyroid hormone receptor trafficking at membrane microdomains. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 35020–35029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hartmann C. (2006) A Wnt canon orchestrating osteoblastogenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 16, 151–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tobimatsu T., Kaji H., Sowa H., Naito J., Canaff L., Hendy G. N., Sugimoto T., Chihara K. (2006) Parathyroid hormone increases β-catenin levels through Smad3 in mouse osteoblastic cells. Endocrinology 147, 2583–2590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wheeler D. S., Barrick S. R., Grubisha M. J., Brufsky A. M., Friedman P. A., Romero G. (2011) Direct interaction between NHERF1 and Frizzled regulates β-catenin signaling. Oncogene 30, 32–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Romero G., Sneddon W. B., Yang Y., Wheeler D., Blair H. C., Friedman P. A. (2010) Parathyroid hormone receptor directly interacts with dishevelled to regulate β-catenin signaling and osteoclastogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 14756–14763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Weinstein R. S., Jilka R. L., Almeida M., Roberson P. K., Manolagas S. C. (2010) Intermittent parathyroid hormone administration counteracts the adverse effects of glucocorticoids on osteoblast and osteocyte viability, bone formation, and strength in mice. Endocrinology 151, 2641–2649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Takahashi Y., Morales F. C., Kreimann E. L., Georgescu M. M. (2006) PTEN tumor suppressor associates with NHERF proteins to attenuate PDGF receptor signaling. EMBO J. 25, 910–920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]