Background: Autophagy is induced by stress, starvation, and viral infections; however, the role of RNase L in autophagy has not been investigated.

Results: Activation of RNase L induces autophagy involving JNK and PKR.

Conclusion: Autophagy induced by activation of RNase L modulates viral growth.

Significance: Our findings identify a novel role of RNase L in inducing autophagy affecting outcomes of viral infections.

Keywords: Autophagy, Host-Pathogen Interactions, Innate Immunity, Jun N-terminal Kinase (JNK), Ribonuclease, PKR, RNase L, Antiviral Effect

Abstract

Autophagy is a tightly regulated mechanism that mediates sequestration, degradation, and recycling of cellular proteins, organelles, and pathogens. Several proteins associated with autophagy regulate host responses to viral infections. Ribonuclease L (RNase L) is activated during viral infections and cleaves cellular and viral single-stranded RNAs, including rRNAs in ribosomes. Here we demonstrate that direct activation of RNase L coordinates the activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR) to induce autophagy with hallmarks as accumulation of autophagic vacuoles, p62(SQSTM1) degradation and conversion of Microtubule-associated Protein Light Chain 3-I (LC3-I) to LC3-II. Accordingly, treatment of cells with pharmacological inhibitors of JNK or PKR and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) lacking JNK1/2 or PKR showed reduced autophagy levels. Furthermore, RNase L-induced JNK activity promoted Bcl-2 phosphorylation, disrupted the Beclin1-Bcl-2 complex and stimulated autophagy. Viral infection with Encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) or Sendai virus led to higher levels of autophagy in wild-type (WT) MEFs compared with RNase L knock out (KO) MEFs. Inhibition of RNase L-induced autophagy using Bafilomycin A1 or 3-methyladenine suppressed viral growth in initial stages; in later stages autophagy promoted viral replication dampening the antiviral effect. Induction of autophagy by activated RNase L is independent of the paracrine effects of interferon (IFN). Our findings suggest a novel role of RNase L in inducing autophagy affecting the outcomes of viral pathogenesis.

Introduction

Autophagy is a conserved pathway that facilitates recycling of long-lived proteins, damaged or surplus organelles as well as pathogens, including viruses, for degradation. During autophagy, specific cargo is enclosed in double-membrane vesicles (autophagosomes), with small portions of cytoplasm. These autophagosomes fuse with the endolysosomal system where the sequestered material is degraded (1–3). Mammalian autophagy is regulated through a core complex formation between Beclin1, a B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2)2-interacting protein, and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase class 3 (PI3KC3/Vps34), which participates in nucleation of autophagosome (4, 5). Many cofactors (Atg14L, UVRAG, Bif-1, Rubicon, Ambra1, HMGB1, VMP1, IP3R, PINK, and Survivin) regulate the activity of Beclin1-Vps34 complex and regulate autophagy in response to diverse stimuli or stress (5, 6). The Bcl-2 homology-3 (BH3) domain in Beclin1 mediates interaction with antiapoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and B-cell lymphoma extra long (Bcl-xL) during steady-state growth conditions, thereby inhibiting autophagy (7–10). During starvation, stress-activated c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase (JNK) phosphorylates Bcl-2, an antiapoptotic protein. Phospho-Bcl-2 dissociates from Beclin1 and stimulates autophagy (10–12). Also, death-associated protein kinase (DAPK) can phosphorylate Beclin1, promoting dissociation of Beclin1 from Bcl-2-like proteins to induce autophagy (13).

Autophagy has diverse outcomes in the pathogenesis of viral infections: it may function as an antiviral mechanism to promote elimination of viruses and induce adaptive response or it may enhance viral replication or exit from cells (14). Autophagy-related proteins (Atg) are important for innate immune responses induced by activation of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), such as the Toll-like receptors (TLRs) or Rig-like helicases (RLHs) by viral components. Stimulation of TLR7 or TLR3 by single-stranded or double-stranded RNA, respectively, induces autophagy via an interaction between the TLR adaptor, MyD88, and Beclin1 which in turn is required for type I interferon (IFN) production (15, 16). In contrast, Atg5-Atg12 conjugate can bind to retinoic acid-inducible gene I (Rig-I) and IFNβ-promoter stimulator-1 (IPS-1) to suppress type I IFN production (17). The crosstalk between pathogen-sensing pathways and autophagy is further substantiated by the role of NLRX1, a unique member of the nucleotide-binding domain (NBD) and leucine-rich repeats (LRRs)-containing proteins (NLRs), that dually regulates IFN-I and autophagy through the engagement of a mitochondrial protein, TUFM (18). In addition to pathways activated by pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), increased viral protein synthesis and unfolded proteins promote ER stress and induce activity of inositol-requiring kinase 1(IRE1) and JNK which are inducers of autophagy (19–22). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and free fatty acids also activate JNK to induce autophagy in colorectal carcinoma cell line, HCT116, and pancreatic β cells (23, 24).

The IFN-inducible double-stranded protein kinase (PKR) and PKR-like ER kinase (PERK) are required for autophagy induced by ER stress during Herpes Simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) infection in MEFs and primary neurons (25, 26). HSV-1 gene product ICP34.5 blocks autophagy induction by dephosphorylating eIF2α (thereby inhibiting PKR signaling) and binding to Beclin1 (25, 27). The autophagy-inducing functions of PKR, therefore, could also mediate the antiviral effects. In addition to the PKR pathway, a second IFN-inducible dsRNA detecting system, the 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase (OAS)/ribonuclease L (RNaseL) system is implicated in the antiviral activities of IFN (28). OAS proteins are activated by viral dsRNA PAMPs or RNAs with secondary structures to produce 2–5A [px5′A(2′p5′A)n; x = 1–3; n ≥ 2] from cellular ATP, which in turn binds specifically to the latent endoribonuclease, RNase L (29). 2–5A binding converts RNase L from an inactive monomer to an active dimer that cleaves single-stranded regions of viral and host RNAs at UpUp and UpAp dinucleotides generating small duplex RNAs with 3′-phosphoryl and 5′-hydroxyl termini (30, 31). These small RNA cleavage products signal through Rig-I-like helicases, Rig-I and MDA5 to amplify the production of IFNβ (32). Activated RNase L cleaves diverse substrates including 18S and 28S rRNA, an assay used to monitor activity of RNaseL in intact cells, thus inhibiting cellular protein synthesis (31, 33). The turnover of damaged ribosomes and rRNA decay occurs in cells through selective autophagy known as ribophagy (34). Activation of RNaseL by 2–5A causes ribotoxic stress and activates JNK in several cell lines (35–37). The causal relationship between autophagy and innate immunity and activation of JNK by RNase L, prompted us to explore the role of RNase L in inducing autophagy. Here, we show that direct activation of RNase L by 2–5A induces autophagy. Activity of JNK and PKR induced by RNase L are required for induction of autophagy. Phosphorylation of Bcl-2 by JNK disrupts Beclin1-Bcl-2 complex and facilitates Beclin1-Vps34 complex formation, which is necessary for nucleation of autophagosomes. By using pharmacological inhibitors, siRNA-mediated knockdown of autophagy-related genes and knock-out MEFs, we show that autophagy contributes to the antiviral activities of RNase L. Finally, we demonstrate that the ability to induce autophagy is independent of the paracrine effects of IFNβ produced by RNase L. Our studies identify a novel role of RNase L in modulating viral growth by inducing autophagy.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals, Reagents, and Antibodies

Chemicals, unless indicated otherwise, were from Sigma Aldrich. Antibodies to phospho-stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK)/JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), total JNK, LC3, SQSTM1/p62, PI3 Kinase Class III (VPS34), Bcl-2, phospho-Bcl-2 (Ser70), total eIF2α, phospho-eIF2α and Atg5 were from Cell Signaling, Inc. (Danvers, MA). PKR, phospho-PKR (pT451) was from Epitomics (Burlingame, CA) and Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) (for MEFs). Anti-Sendai virus antibody was from MBL (Woburn, MA) and Mengo 3D Pol antibody was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Antibody to β-actin, protein A-Sepharose, and 3-methyladenine was from Sigma; Beclin1 was from Novus Biologicals, LLC, (Littleton, CO). Monoclonal antibody to human RNase L was kindly provided by Robert Silverman (Cleveland Clinic). Polyclonal antibody to mouse RNase L was a kind gift from Aimin Zhou (Cleveland State University). Anti-mouse IgG and anti-rabbit IgG HRP linked secondary antibodies were from Cell Signaling, Inc. (Danvers, MA), and ECL reagents were from GE Healthcare (Piscataway, NJ). The JNK inhibitor SP600125 and rapamycin were from Calbiochem. LysoTrackerR Red DND-99, Trizol LS and Lipefectamine 2000 were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Bafilomycin A1 was from Enzo Life Sciences, Inc. (Farmingdale, NY), 2-aminopurine was from Invivogen (San Diego, CA). GFP-LC3 plasmid was provided by Isei Tanida (via Addgene) (38). Sendai virus (Cantell strain) was from Charles River Laboratories (Preston, CT), and Encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV K strain) was a kind gift from Robert Silverman (Cleveland Clinic). 2–5A [p3(A2′p)nA, where n = 1 to >3], was prepared enzymatically from ATP and recombinant 2–5A synthetase (a generous gift from Rune Hartmann, University of Aarhus, Aarhus, Denmark) as described previously (39). The 2–5A is a mixture of ppp(A2′p)nA, in the following proportions: n = 1, 16%; n = 2, 37%; n = 3, 26%; and n = 4, 9%.

Cell Culture and Transfections

The human fibrosarcoma cell line, HT1080 (a gift from Ganes Sen, Cleveland Clinic), U3A (STAT1-defective, derived from parental 2fTGH cells, which were derived from HT1080 cells, was a gift from George Stark, Cleveland Clinic), ATG5−/− (ATG5 KO) and WT MEFs transformed with SV40 T antigen (provided by Shigeomi Shimizu, Tokyo, Japan), JNK1−/− JNK2−/− (JNK1/2 KO), and WT MEFs ( a gift from Kanaga Sabapathy, Singapore), L929 (a gift from Douglas Leaman, University of Toledo) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified minimal essential medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), 100 μg/ml penicillin/streptomycin, 2 mm l-glutamine, and non-essential amino acids. WT, RNaseL−/− (RNase L KO), PKR−/− (PKR KO), RNaseL−/− PKR−/− (RNase L PKR double KO) and IFNAR KO MEFs transformed with SV40 large T antigen (a gift from Robert Silverman, Cleveland Clinic) were grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with streptomycin (100 μg/ml), penicillin (100 units/ml), 2 mmol/liter glutamine, and 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen). Cells were maintained in 95% air, 5% CO2 at 37 °C. RNase L KO MEFs were reconstituted with either pcDNA3.1 plasmid carrying WT RNase L, RNase L R667A mutant (lacks nuclease activity), or vector alone followed by transfection with 2–5A. Transfection of 2–5A (10 μm) was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, cells were plated 1 day before transfection, so that the cells are 80–90% confluent at the time of transfection. 2–5A was diluted into serum-free media and then mixed with Lipofectamine 2000 for 20 min before being added to cells in growth media. In experiments involving inhibitors, cells were preincubated with inhibitor for 1 h prior to 2–5A transfection and then replaced. Rapamycin (100 nm, dissolved in DMSO) was added to the cell culture medium in some experiments to induce autophagy. GFP-LC3 was transfected in HT1080 cells using TransIT-LT1 reagent (Mirus Bio LLC, Madison, WI) and in MEFS using GenJet In Vitro DNA Transfection Reagent (Ver.II) (SignaGen Laboratories, Ijamsville, MD) according to manufacturer's protocols.

Virus Infections and Plaque Assay

Cells (2 × 105 in 12-well plates) were grown overnight, washed two times with PBS and infected with EMCV (strain K) at MOI = 0.1 or Sendai virus (SeV) at 40 HAU/ml in media without serum. After 1 h, media were removed, cells were washed with PBS, and complete media were added until they were harvested. For virus growth experiments, WT or RNase L KO MEFs were infected with EMCV at MOI = 0.01 or Sendai virus at 20 HAU/ml in the presence or absence of inhibitors for indicated times. In experiments with inhibitors, cells were pretreated with 3-methyladenine (5 mm) or Bafilomycin A1 (100 nm) for 1h, infected with EMCV or SeV and then fresh complete media with 10% FBS with or without inhibitors was added. Expression of viral antigen was determined on Western blots using anti-Sendai virus antibody or 3D Pol antibody (for EMCV). EMCV containing supernatants were serially diluted and added to L929 cells for 1h. The cells were washed with PBS and overlaid with DMEM containing 0.5% carboxymethylcellulose and incubated for 24h. The cells were fixed with 10% formaldehyde and stained using 0.1% crystal violet and plaques were counted. The assays were performed in triplicate and fold change in virus titers were determined from three independent experiments.

Sendai Virus Quantification

Sendai Viral RNA copy numbers were quantified by real-time PCR (qPCR) as described (40). RNA from 2 ml of supernatants of Sendai virus infected cells was extracted using Trizol LS reagent (Invitrogen) for cDNA synthesis using random decamers and Retroscript cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen) and PCR using Sybr Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) using primers SeVF (5′-GACGCGAGTTATGTGTTTGC-3′) and SeVR (5′-TTCCACGCTCTCTTGGATCT-3′). Copy numbers were interpolated from a T7-transcribed RNA standard, and expressed as copy number per ml of supernatant. All assays were performed in triplicate and fold change in SeV RNA copies were determined from three independent experiments.

Monitoring RNase L Activity in Intact Cells

HT1080 cells were transfected with 10 μm 2–5A using Lipofectamine 2000. At the indicated times, the total RNA was isolated from transfected cells using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and quantitated by measuring absorbance at 260 nm. Also, RNase L KO MEFs reconstituted with either pcDNA3.1 plasmid carrying WT RNase L, RNase L R667A mutant (lacks nuclease activity) or vector alone were transfected with 10 μm of 2–5A as above and total RNA was isolated. RNA (2 μg) was separated on RNA chips and analyzed with Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies) as described previously (41).

siRNA Transfections

siRNA transfections in HT1080 cells were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's protocols. The following siRNAs were used: siBECN1(h) (pool of three siRNAs; SC-29797), siRNaseL(h) (pool of three siRNAs; SC-45965), controlsiRNA-A(SC-29527) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and Signal Silence ATG5 siRNA (Cell Signaling Inc.(Danvers, MA) at 100 nm. Atg5 was also knocked down using another siRNA (1027415, Qiagen, MD) that has been previously validated. After 36h, cells were transfected with 2–5A and cell lysates were used for Western blotting. To monitor the kinetics of autophagy induction, cells were first transfected with GFP-LC3 and after 12 h with siRNA. 2–5A was transfected after 36 h, and the knockdown of the protein levels were confirmed by Western blots at the end of the experiment.

Quantification of Autophagy and Immunofluorescence

HT1080 or MEFs were transfected with GFP-LC3 and 24h later with 2–5A using Lipofectamine 2000 and visualized by fluorescence microscopy. Autophagy was quantified by counting the percentage of GFP-LC3 cells showing numerous GFP-LC3 puncta (>10 puncta/cell). A minimum of 100 cells per preparation were evaluated in three independent experiments. Cells with diffuse GFP-LC3 in the cytoplasm and nucleus or cells with less than 10 puncta per cell were considered non-autophagic. Cells cultured on coverslips or slide chambers (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) were stained with Lysotracker DND99 red, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (EM Sciences, Hatfield, PA) in PBS for 15min at room temperature and mounted in Vectashield with DAPI to stain the nucleus (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA). Fluorescence and confocal microscopy assessments were performed with Leica CS SP5 multi-photon laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Weitzler, Germany). To analyze autophagic flux, cells were treated in the absence or presence of the vacuolar H+-ATPase inhibitor Bafilomycin A1(100 nm) to inhibit autophagosome-lysosome fusion (42). To quantify the number of GFP-LC3 puncta in a single cell, Z-stack images of single GFP-LC3-expressing cells were collected using 60× oil and the number of GFP-LC3 puncta in a cell was determined using ImageJ Software (NIH). More than 10 cells were analyzed for each condition.

Immunoblotting and Immunoprecipitation

Cells were washed with ice cold PBS and lysed in buffer containing 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 90 mm KCl, 5 mm Mg acetate, 20 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 5 mm β mercaptoethanol, 0.1 m PMSF, 0.2 mm sodium orthovanadate, 50 mm NaF, 10 mm glycerophosphate, protease inhibitor (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) on ice for 20 min. The lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 10,000 × g (at 4 °C for 20 min). Protein concentrations in the supernatants were determined using BSA as a standard (Bio-Rad protein assay kit). Protein (15–80 μg per lane) was separated in polyacrylamide gels containing SDS and transferred to Immobilon membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Membranes were probed with different primary antibodies according to the manufacturer's protocols. Membranes were washed with TBS with 1% Tween 20 and incubated with goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit antibody tagged with horseradish peroxidase (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA)) for 1 h. Proteins in the blots were detected by enhanced chemiluminesence (GE Healthcare). For determining LC3-II/β-actin and P62/β-actin levels, the intensity of each band was determined by densitometry using Image J (NIH) and relative intensities were calculated by normalizing to β-actin from the corresponding samples. The ratios are graphically presented as the mean ± S.E. from three independent experiments. For immunoprecipitation, HT1080 cells were lysed in CHAPS lysis buffer (20 mm Tris pH 7.4, 137 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 10% glycerol, and 2% CHAPS) for 1 h at 4 °C, and immunoprecipitation was performed overnight at 4 °C with anti-Beclin1 rabbit polyclonal antibody (Novus Biologicals) and Protein A Sepharose beads (Sigma Aldrich) using 500 μg of lysate. Beads were washed two times with 137 mm NaCl CHAPS wash buffer (20 mm Tris pH 7.4, 137 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 10% glycerol, and 0.5% CHAPS), and two times with 274 mm NaCl CHAPS wash buffer. Anti-Beclin1 immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis and Bcl-2 and Vps34 were detected by immunoblot analysis as described above. Beclin 1 was detected in immunoprecipitates using Clean Blot IP detection reagent (HRP) from Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL).

Statistical Analysis

All values are presented as mean ± S.E. from at least three independent experiments. Student's t-tests were used for determining statistical significance between groups. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Activation of RNase L Induces Autophagy

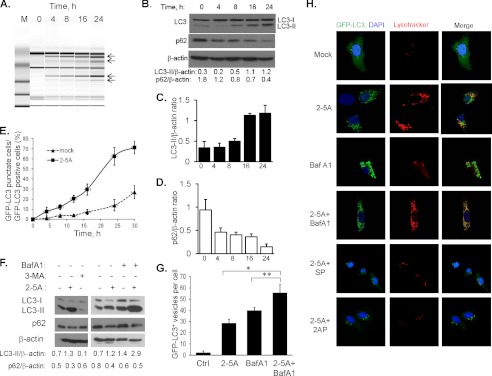

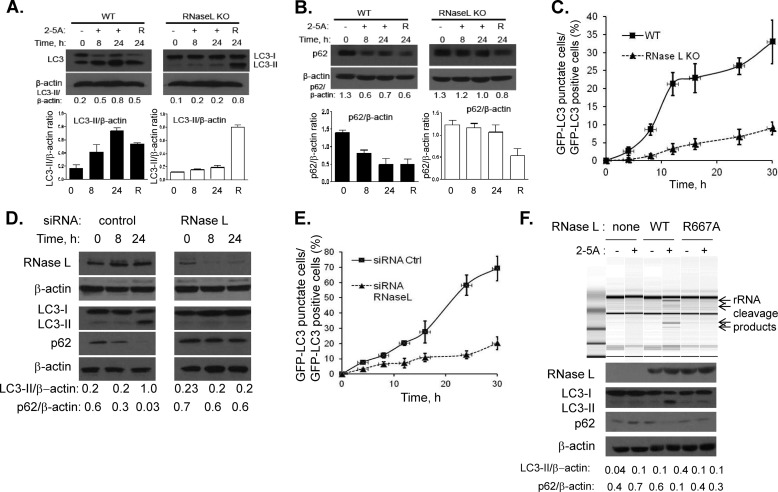

To determine if RNase L can induce autophagy, HT1080 cells were transfected with 2–5A (10 μm) to activate RNase L. Activation was monitored by detecting specific cleavage products of 18S and 28S rRNA which increase with time and increasing concentration of 2–5A (41, 43) (Fig. 1A, supplemental Fig. S1). We observed progressively increasing conversion of the free microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3B-I (LC3-I) to phosphatidylethanolamine-conjugated form (LC3-II) on immunoblots, a hallmark of autophagosome formation (Fig. 1B). The polyubiquitin-binding protein, p62/SQSTM1, which is degraded by autophagy was reduced in a time dependent manner in cells treated with 2–5A (Fig. 1B). Levels of LC3-II or p62 were normalized to the levels of β-actin in at least three independent experiments (Fig. 1, C and D). GFP-LC3 fluorescence was used to microscopically monitor autophagy in 2–5A-transfected cells and induction was followed up to 30 h. The redistribution of GFP-LC3 from diffuse to a punctuate pattern representing autophagosomes was significantly more in 2–5A-transfected cells (71% of GFP+ cells) compared with mock-treated cells (27% of GFP+ cells) (Fig. 1E). The GFP-LC3 protein colocalized with the lysosomal marker, lysotracker red DND-99 (Fig. 1H, supplemental Fig. S2). To confirm that RNase L induced autophagy, we used WT and RNase L−/− MEFs (RNase L KO) (Fig. 2, A--C) and siRNA (pool of three siRNAs) to knockdown RNase L levels (Fig. 2, D and E) in HT1080 cells. RNase L knock-out or siRNA-mediated knockdown of RNase L significantly reduced autophagy as evaluated by LC3-I to LC3-II conversion, p62 degradation and accumulation of GFP-LC3 puncta in response to 2–5A (Fig. 2, A--E, Fig. 3A and B). RNase L KO MEFS did not have a general defect in autophagy since treatment with the autophagy inducer, rapamycin (R), induced biochemical changes consistent with autophagy (Fig. 2, A and B). To further confirm that RNase L enzyme activity is required for induction of autophagy, RNase L KO MEFs were reconstituted with WT RNase L, RNase L R667A mutant that lacks nuclease activity or vector alone and transfected with 2–5A. Restoring RNase L activity, as monitored by rRNA cleavage on RNA chips, caused lipidation of LC3-II and degradation of P62 (Fig. 2F). Lipidation of LC3-II and p62 degradation was inhibited by pretreatment with 3-methyladenine (3-MA), a class III PI3K inhibitor, that inhibits formation of autophagosomes (Fig. 1F). To measure autophagic flux, cells were transfected with 2–5A in the absence or presence of Bafilomycin A1 to prevent fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes causing accumulation of autophagosomes. The abundance of LC3-II and p62 increased further in combined treatments, indicating increased autophagic flux during RNase L activation (Fig. 1, F and H, supplemental Fig. S2). Inhibition of autophagosome/lysosome fusion resulted in increased number of GFP-LC3 vesicles (puncta) per cell in control (basal autophagy, BafA1 alone, 40%), which increased further when combined with 2–5A (induced autophagy, BafA1 + 2–5A, 56%) compared with 2–5A alone (29%) (Fig. 1G). These results suggest that activation of RNase L stimulates the formation of autophagosomes and induces autophagy.

FIGURE 1.

2–5A-mediated activation of RNase L induces autophagy. A, HT1080 cells were transfected with 10 μm of 2–5A and cleavage of rRNA (shown by arrows) was analyzed on RNA chips using Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100. B, 2–5A was transfected for indicated times and conversion of unconjugated LC3-I to lipidated LC3-II and degradation of p62 was monitored on immunoblots and normalized to β-actin levels. Band intensity was calculated using Image J software and ratios of LC3-II/β-actin or p62/β-actin was determined. Similar results were observed in three independent experiments. C and D, each bar represents the ratios of LC3-II/β-actin or p62/β-actin corresponding to the time points in B from three experiments shown as mean ± S.E. E, GFP-LC3 expressing HT1080 cells were transfected with 10 μm of 2–5A and the percentage of GFP+ cells showing puncta formation compared with mock-treated cells is shown. Results shown represent mean ± S.E. for three experiments and at least 100 cells were analyzed per assay. F, effect of 3-MA or BafA1 on autophagic flux induced by 2–5A. HT1080 cells were transfected with 2–5A, during the last 4 h of the 24 h treatment, 5 mm of 3-MA or 100 nm of BafA1 was optionally added. Cell lysates were analyzed on immunoblots and quantitated as in B. G, numbers of GFP+ vesicles per cell enumerated from at least 10 cells per sample. Data represent mean ± S.E. from n = 3. Student's t test, *, p < 0.0001, **, p < 0.001. H, GFP-LC3-expressing HT1080 cells were transfected with 10 μm of 2–5A alone or in the presence of Bafilomycin A1 (100 nm), JNK inhibitor (SP600125, 25 μm) or PKR inhibitor (2-aminopurine, 5 mm) or Bafilomycin A1 alone. Cells were stained with Lysotracker Red (lysosomes) or DAPI (nucleus, blue) and images taken at ×60 magnification using confocal microscope. Representative images are shown.

FIGURE 2.

Autophagosome formation is inhibited in RNase L-deficient cells. WT and RNase L KO MEFs were transfected with 10 μm of 2–5A for indicated times and LC3-II lipidation (A) or p62 degradation (B) was monitored on immunoblots. Cells treated with rapamycin (100 nm, R) served as control for autophagy induction. Ratios of LC3-II/β-actin or p62/β-actin were determined using Image J. Each bar shown below represents the ratios from three different experiments shown as mean ± S.E. C, WT and RNase L KO MEFs were initially transfected with GFP-LC3 and 24 h later with 10 μm of 2–5A. The percentage of GFP+ cells showing puncta formation compared with mock-treated cells is shown. Results shown represent mean ± S.E. for three experiments and at least 100 cells were analyzed per assay. D, HT1080 cells were treated with control siRNA (100 nm) or RNaseL siRNA (100 nm, pool of three siRNAs) for 36 h, followed by 2–5A transfection (10 μm) for indicated times. Cell lysates were analyzed for protein levels of RNase L (80% knockdown) and LC3-II lipidation and p62 degradation. Representative immunoblots are shown. E, cells were transfected with GFP-LC3 prior to transfection with relevant siRNA and 2–5A as in D. The percentage of GFP+ cells showing puncta formation compared with control siRNA-treated cells is shown. Results shown represent mean ± S.E. for three experiments and at least 100 cells were analyzed per assay. F, RNase L KO MEFs were reconstituted with WT RNase L, mutant RNase L R667A (nuclease-dead) or vector alone and transfected with 10 μm of 2–5A for 4 h. Cleavage of rRNA (shown by arrows) was analyzed on RNA chips using Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100. 100 μg of lysates were probed for RNase L expression on immunoblots. Conversion of unconjugated LC3-I to lipidated LC3-II and degradation of p62 was monitored on immunoblots and normalized to β-actin levels. Band intensity was calculated using Image J software and ratios of LC3-II/β-actin or p62/β-actin was determined.

FIGURE 3.

Induction of autophagosomes in response to activation of RNase L. GFP-LC3-transfected cells (A) WT and RNase L KO MEFs, (B) HT1080 cells treated as described under “Experimental Procedures” with control siRNA, siRNase L, siBeclin1 or siAtg5, (C) WT and JNK1/2 KO MEFs, (D) WT and PKR KO MEFs were transfected with 10 μm of 2–5A. Images of cells were taken by confocal microscopy to assess formation of autophagosomes (autofluorescence of GFP-LC3 puncta). Lysosomes were visualized using Lysotracker Red, and nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). The yellow color represents colocalization of GFP-LC3 and lysosomes. Representative images are shown (×60 magnification).

JNK and PKR Are Required for RNase L-induced Autophagy

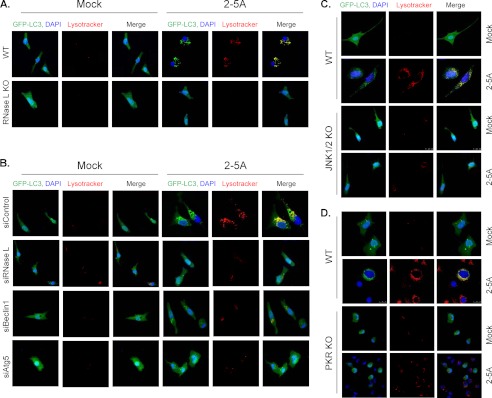

Double-stranded RNA activates IFN-inducible protein kinase R (PKR) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK): both are inducers of autophagy (11, 25). dsRNA can also activate 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase enzymes (OAS) to produce 2–5A, the activator of RNase L, which in turn can activate JNK (35–37). We therefore evaluated the role of JNK and PKR in RNase L-induced autophagy. HT1080 cells transfected with 2–5A (10 μm) showed increased phosphorylation of JNK and PKR on immunoblots. At later time points (16 and 24 h), an increase in PKR protein levels consistent with increase of PKR mRNA expression was observed (44, 45) (Fig. 4A, supplemental Fig. S3). Activation of PKR correlated with the phosphorylation of its natural substrate, eIF2α (Fig. 4, A, B, and D). RNase L-induced lipidation of LC3-II and p62 degradation was suppressed by treatment with SP600125 (SP), a selective JNK inhibitor or 2-aminopurine (2AP), inhibitor of PKR activity (Fig. 4B). GFP-LC3 puncta formation (monitored up to 30 h) was significantly decreased in cells treated with JNK (41%) or PKR inhibitor (45%) in the presence of 2–5A compared with 2–5A alone (71%) (Fig. 1H, supplemental Figs. S2 and 4C). The inhibitors alone did not cause puncta formation greater than mock-treated cells (data not shown). Requirement of JNK and PKR was also confirmed using WT and JNK1/2 KO or PKR KO mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) transfected with 2–5A combined with or without JNK inhibitor or PKR inhibitor (Fig. 4D). WT MEFs showed increased conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II and p62 degradation compared with JNK1/2 KO or PKR KO MEFs. These hallmarks of autophagy were suppressed in WT MEFs by treatment with JNK inhibitor or PKR inhibitor. There were no significant differences in expression of RNase L or PKR in WT and JNK1/2 KO MEFs (Fig. 4D). Consistent with results obtained with pharmacological inhibitors, the GFP-LC3 puncta formation in JNK1/2 KO MEFs and PKR KO MEFs was 57 and 42% of WT MEFs (Fig. 3, C and D and 4E). Taken together, these results indicate that JNK and PKR pathways play important roles in induction of autophagy in response to activation of RNase L.

FIGURE 4.

RNase L-induced autophagy is regulated by activity of JNK and PKR. A, HT1080 cells were transfected with 10 μm of 2–5A for indicated times. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with phospho-PKR (T451), total PKR, phospho-eIF2α, total eIF2α, phospho-JNK (T183,Y185), and total JNK antibodies. B, HT1080 cells were pretreated with PKR inhibitor (2-aminopurine, 5 mm) or JNK inhibitor (SP600125, 25 μm) for 1 h prior to 2–5A transfection (10 μm, 16 h) and then replaced. Inhibition of autophagy was evaluated on immunoblots by LC3-II lipidation and p62 degradation normalized to β-actin levels. Inhibition of PKR and JNK was confirmed using phospho-specific antibodies. C and E, HT1080 cells, WT, PKR KO, or JNK1/2 KO MEFs transfected with GFP-LC3 were treated as in B. The percentage of GFP+ cells showing puncta formation compared with control cells is shown. Results shown represent mean ± S.E. for three experiments and at least 100 cells were analyzed per assay. D, WT and PKR KO or JNK1/2 KO MEFs were transfected with 10 μm of 2–5A and optionally with PKR inhibitor (2-AP, 5 mm) or JNK inhibitor (SP, 25 μm). LC3-II lipidation and p62 degradation were immunodetected as in B and analyzed. Activation of PKR in A, B, and D were correlated with phospho-eIF2α.

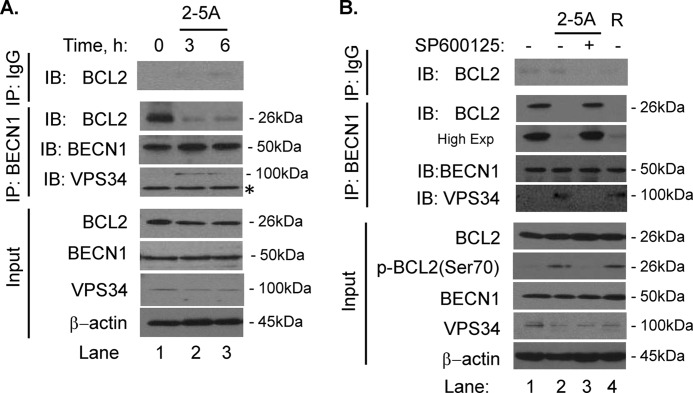

RNase L-induced JNK Activity Disrupts Beclin1-Bcl-2 Complex

Autophagy is tightly regulated by Beclin1-Vps34 complex, which initiates the formation of autophagosomes. The pro-autophagy function of this complex is inhibited by binding of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL to Beclin1. Other studies have reported that the c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 disrupts the Beclin1-Bcl-2 complex in response to starvation, ceramide, lipids, and BH3 mimetics (8, 10, 11, 46). Since JNK is activated by 2–5A (Fig. 4A), we examined if Beclin1 binding to Bcl-2 was regulated by RNase L activity. In co-immunoprecipitation experiments, we observed Bcl-2 binding to Beclin1 under normal growth conditions (Fig. 5A). In cells transfected with 2–5A, only a small fraction of Bcl-2 interacted with Beclin1. Under these conditions, we observed complex formation of Beclin1 and Vps34 (Fig. 5A). Pretreatment of 2–5A-transfected cells with 25 μm of SP600125 (a selective JNK inhibitor) for 1h, prevented dissociation of the Beclin1-Bcl-2 complex (Fig. 5B, lane 3). Cells treated with a potent inducer of autophagy, Rapamycin, showed similar disruption of Beclin1-Bcl-2 complex formation (Fig. 5B, lane 4). Bcl-2 is phosphorylated on serine 70 residue, a site previously shown to be phosphorylated by JNK activity (11, 12). We observed Bcl-2 (Ser70) phosphorylation in response to 2–5A transfection which was abolished when cells were treated with JNK inhibitor (Fig. 5B, lane 2 versus 3). Our results thus suggest that RNase L-mediated JNK activation phosphorylates Bcl-2, which promotes dissociation of Beclin1-Bcl-2 complex which in turn induces autophagy.

FIGURE 5.

RNase L activation induces dissociation of Beclin1-Bcl-2 complex via JNK pathway. A, HT1080 cells were transfected with 2–5A for 3 or 6 h prior to co-immunoprecipitation with control IgG or anti-Beclin1 antibody. Endogenous Beclin1 and co-immunoprecipitated proteins, Bcl-2 or Vps34, were detected using specific antibodies. Expression of the relevant proteins in the cell lysates was confirmed on immunoblots. * indicates nonspecific protein. B, cells were pretreated with JNK inhibitor, SP600125 (25 μm), for 1 h followed by 4 h transfection with 2–5A. As control, HT1080 cells were treated with 100 nm rapamycin (R) for 4 h. Endogenous Beclin1 was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates and co-immunoprecipitated proteins were subject to immunoblotting using anti-Bcl-2 and anti-Vps34 antibodies. Phosphorylation of Bcl-2 on Ser70 residue was detected in cell lysates using phospho-specific antibodies. Protein expression in lysates was normalized to β-actin levels. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

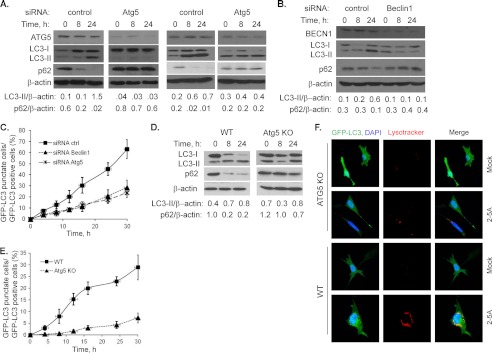

To further dissect the molecular pathways involved in RNase L-induced autophagy, we used siRNA duplexes (pool of three siRNAs) to knockdown Beclin1 (90% of control siRNA) or two different siRNAs targeting Atg5 (80% or 70% of control siRNA); both are required for the early stages of autophagosome formation (17). In knockdown cells transfected with 2–5A, we observed significantly decreased lipidation of LC3-II and p62 degradation compared with non-targeted siRNA-treated cells (Fig. 6, A and B). The GFP-LC3 puncta formation was reduced to 29% (for Beclin1 knockdown) and 24% (for Atg5 knockdown) compared with 63% in control siRNA-treated cells (Figs. 3B and 6C). Also, MEFs lacking Atg5 protein expression (Atg5 KO) showed no increase in LC3-II lipidation or p62 degradation when transfected with 2–5A (Fig. 6D). Atg5 KO MEFs showed 75% decrease in puncta formation compared with WT MEFs (Fig. 6, E and F). These results provide evidence that activation of RNase L induces autophagy involving Beclin1 and Atg5: both proteins are essential for induction of autophagy.

FIGURE 6.

Beclin1 and autophagy-related genes are required for RNase L-induced autophagy. A and B, HT1080 cells were transfected with 100 nm of indicated siRNAs (control, Beclin1 (pool of three siRNAs), Atg5 (two separate siRNAs)) for 36h, followed by 2–5A transfection to induce autophagy for indicated times. Cell lysates were analyzed for knockdown protein levels on immunoblots. Induction of autophagy was determined on immunoblots by lipidation of LC3-II and p62 degradation normalized to β-actin levels. C, quantitation of autophagy in HT1080 cells co-transfected with GFP-LC3 and control siRNA or with GFP-LC3 and siBeclin1 or siAtg5. The percentage of GFP+ cells showing puncta formation in knockdown cells was compared with control siRNA-treated cells. Results shown represent mean ± S.E. for three experiments and at least 100 cells were analyzed per assay. D, WT or Atg5 KO MEFs were transfected with 10 μm of 2–5A for indicated times and induction of autophagy was determined as in A and B. E, quantitation of autophagy in WT and Atg5 KO MEFs as in C. Results are mean ± S.E., n = 3. F, WT and ATG5 KO MEFs were transfected with GFP-LC3 followed by 10 μm of 2–5A. Images of cells were taken by confocal microscopy to assess formation of autophagosomes (autofluorescence of GFP-LC3 puncta). Lysosomes were visualized using Lysotracker Red and nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). The yellow color represents colocalization of GFP-LC3 and lysosomes. Representative images are shown. (×60 magnification).

Autophagy Induced by Activation of RNase L Modulates Viral Growth

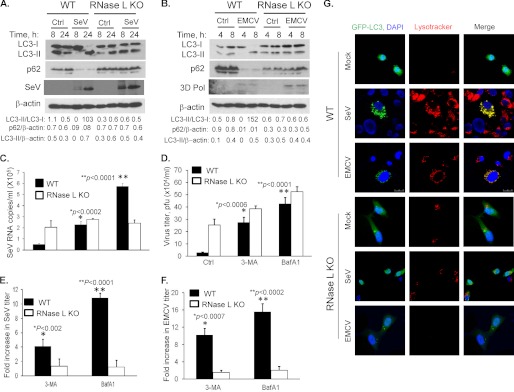

We have shown previously that activation of RNase L during viral infections, particularly Encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) and Sendai virus (SeV), generates small RNA cleavage products that amplify production of type I interferon (32). Many viruses manipulate the host autophagic machinery to benefit or inhibit virus replication and pathogenesis (3). To explore the role of RNase L in the intersection between autophagic and antiviral pathways, WT and RNase L KO MEFs were infected with EMCV (MOI = 0.1) for 8h or SeV (40 HAU/ml) for 16 h. We observed very significant conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II in response to both EMCV and SeV in WT MEFs, compared with RNase L KO MEFs (Fig. 7, A and B). While p62 protein decreased sharply in infected WT MEFs, p62 remained unchanged or accumulated in RNase L KO MEFs infected with either SeV or EMCV. The expression of viral antigens was determined on immunoblots. These results suggest that RNase L participates in induction of autophagy during EMCV or SeV infections.

FIGURE 7.

Inhibition of autophagy modulates antiviral effects of RNase L. WT and RNase L KO MEFs were infected with (A) SeV (40HAU/ml) or (B) EMCV (MOI = 0.1) for indicated times, and cell lysates were analyzed for induction of autophagy. Conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II by lipidation and degradation of p62 were normalized to β-actin levels. Expression of viral antigens were detected using anti-Sendai-virus antibody or 3D Pol antibody (for EMCV). C and D, WT and RNase L KO MEFs were pretreated with autophagy inhibitors, 3-MA (5 mm) or BafA1 (100 nm) for 1 h, followed by infection with SeV (40 HAU/ml) or EMCV (MOI = 0.1) for 16 h or 8 h. Control samples were treated with DMSO (vehicle). Viral titers for EMCV were determined by plaque assay and copy numbers of SeV genomic RNA strands were determined in supernatants by real-time RT-PCR as described under “Experimental Procedures.” E and F, fold increase in viral yields in WT and RNase L KO MEFs treated with either 3-MA (5 mm) or Bafilomycin A1 (100 nm) were compared with control samples. Data represent mean ± S.E. for three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Student's t test was used to determine p values of treated cells compared with DMSO-treated cells (Ctrl). G, WT and RNase L KO MEFs were transfected with GFP-LC3 followed by infection with EMCV (MOI = 0.1) for 8 h or SeV (40 HAU/ml) for 24 h. Lysosomes were stained with lysotracker (red), and nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). GFP-LC3 puncta formation was visualized under confocal microscope at ×60 magnification. Representative images are shown out of three experiments.

To determine if autophagy contributes to the antiviral effects of RNase L, WT and RNase L KO MEFs were infected with EMCV (MOI = 0.1) for 8 h or SeV (40 HAU/ml) for 16 h (single cycle replication) in the absence or presence of vacuolar H+-ATPase inhibitor, Bafilomycin A1, which prevents autophagosome-lysosome fusion, or PI3-kinase inhibitor, 3-methyladenine, which prevents autophagosome formation. Consistent with previous results we observed increased replication of EMCV and SeV in RNase L KO MEFs compared with WT MEFs (Fig. 7, C and D, Ctrl) (32, 47). Inhibiting autophagy with 3-MA or Bafilomycin A1 increased viral yield in WT and KO MEFs. However, the increase in viral titers was significantly more in WT MEFs (4–11-fold for SeV and 10–16-fold for EMCV) than RNase L KO MEFs (less than 2-fold for SeV and up to 2-fold for EMCV) for both inhibitors (Fig. 7, E and F). To monitor autophagy in response to viral infections, we transfected MEFs with GFP-LC3 and then infected them with EMCV (MOI = 0.1) or SeV (40 HAU/ml). The formation of punctate structures was significantly higher in infected WT MEFs compared with RNase L KO MEFs (Fig. 7G). Taken together, these results suggest that during initial cycles autophagy contributes to the antiviral effects of RNase L.

We infected WT, RNase L KO, PKR KO, and RNase L/PKR double KO MEFs with EMCV (MOI = 0.1, 8 h) with or without pretreatment with interferon α A/D to induce increase in levels of RNase L and PKR. We observed reduced accumulation of viral antigens on immunoblots reflecting antiviral effect in cells treated with IFN and significantly reduced autophagy in all cell types. RNase L and PKR levels were induced in response to IFN treatment (supplemental Fig. S4). Therefore, in addition to RNase L and PKR, other interferon-stimulated genes impact viral replication, which in turn abrogates induction of autophagy.

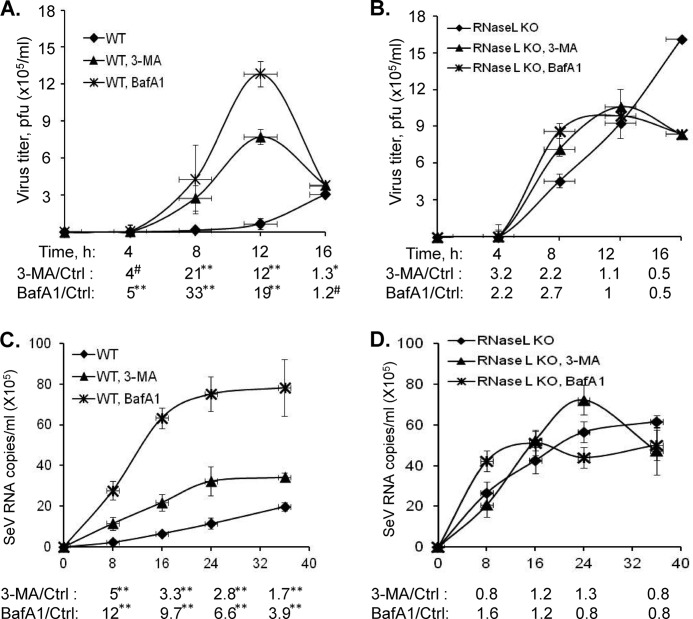

To determine if autophagy induced by RNase L affects virus growth, we measured viral yields in WT and RNase L KO MEFs infected with lower MOI (0.01) of EMCV or 20 HAU/ml of Sendai virus for indicated times (4, 8, 12, and 16 h for EMCV or 8, 16, 24, and 36 h for SeV). As in single replication cycle, we observed increased viral titers in RNase L KO MEFs compared with WT MEFs (Fig. 8, A--D). Inhibiting autophagy with 3-MA or Bafilomycin A1 increased viral titers in WT MEFs during early times of viral growth (21- and 33-fold for EMCV; 5- and 12-fold for SeV at 8h) compared with RNase L KO MEFs (2.2- and 2.7-fold for EMCV; 0.8- and 1.6-fold SeV at 8 h) (Fig. 8, A--D). Therefore, during early phases of replication of both viruses, autophagy induced by RNase L suppresses viral growth. At later times (16 h for EMCV and 36 h for SeV), inhibiting autophagy reduced viral yields in WT MEFs (1.3- and 1.2-fold for EMCV; 1.7 and 3.9-fold for SeV) indicating a role for autophagy in promoting viral replication and dampening the host antiviral effect (Fig. 8, A--D).

FIGURE 8.

Effect of inhibition of autophagy on viral growth in WT and RNase L KO MEFs. Growth curve of EMCV (MOI = 0.01, A and B) or SeV (20 HAU/ml, C and D) in WT and RNase L KO MEFs. WT and RNase L KO MEFs were pretreated with autophagy inhibitors, 3-MA (5 mm) or BafA1 (100 nm) for 1 h or not, followed by infection with SeV (20 HAU/ml) or EMCV (MOI = 0.01) for indicated times. Control samples were treated with DMSO (vehicle). Viral titers for EMCV were determined by plaque assay and copy numbers of SeV genomic RNA strands were determined in supernatants by real-time RT-PCR as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Fold increase in viral yields in WT and RNase L KO MEFs treated with either 3-MA (5 mm) or Bafilomycin A1 (100 nm) were compared with control samples. Data represent mean ± S.E. for two independent experiments performed in triplicate. Student's t test was used to determine p values of WT MEFs compared with identically treated RNase L KO MEFs. #, not significant; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.001.

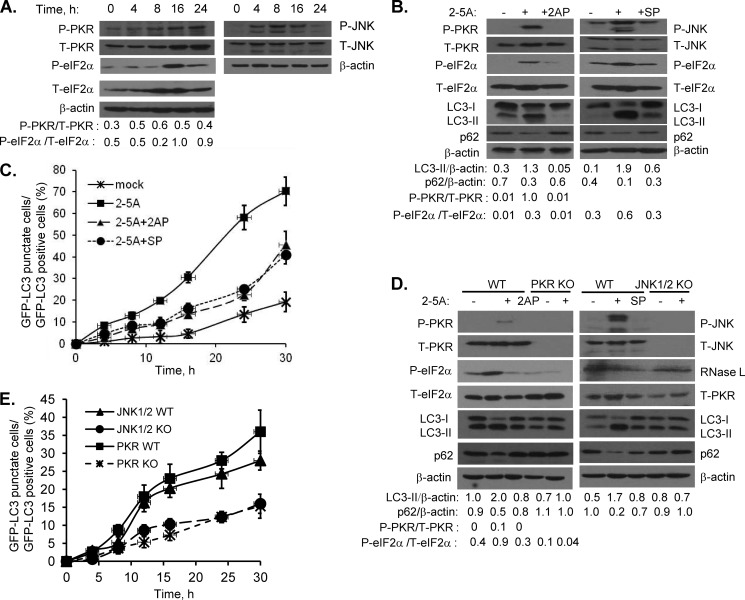

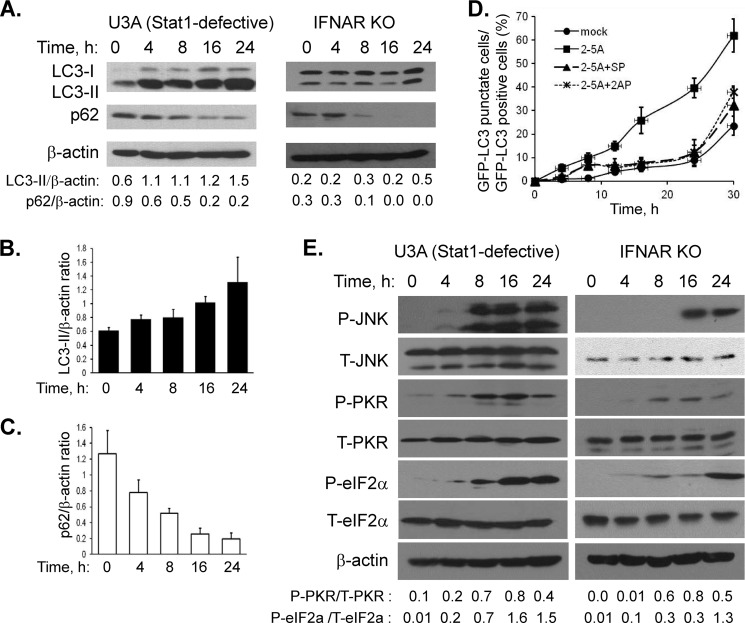

Next, we demonstrated that autophagy induction by RNase L is independent of the paracrine effects of IFN by using U3A cells, which are defective in STAT1-signaling and are therefore IFN-unresponsive or IFNAR KO MEFs (lacking Type I IFN receptor) (48). Transfection of U3A cells with 2–5A activated RNase L similar to parental HT1080 cells as revealed by rRNA cleavage assay (data not shown). In both cells, we observed increased formation of LC3-II and degradation of p62 indicative of induction of autophagy (Fig. 9A). The ratio of LC3-II/β-actin and p62/β-actin in U3A cells from three independent experiments are shown as mean ± S.E. (Fig. 9, B and C). Using phospho-specific antibodies, we monitored the activation of JNK and PKR on immunoblots. Phosphorylation of JNK remained until 24 h and PKR activation peaked at 16 h (Fig. 9E). Activation of PKR correlated with phosphorylation of its natural substrate eIF2α. We conclude that JNK and PKR are activated by 2–5A transfection in cells defective in JAK-STAT-signaling or lacking type 1 IFN receptor, although the kinetics shows some variability. However, like HT1080 cells, we observed increased formation of GFP-LC3 puncta in U3A cells, which was inhibited to 50% levels when 2–5A treatment was combined with JNK inhibitor (SP600125, 25 μm, SP) or PKR inhibitor (2-aminopurine, 5 mm, 2AP) (Fig. 9D). These results suggest that the ability of RNase L to induce autophagy is independent of its IFN-inducing abilities.

FIGURE 9.

Autophagy induced by RNase L is independent of paracrine effects of IFN. A, STAT1-signaling defective U3A cells or type1 IFN receptor defective IFNAR KO MEFs were transfected with 10 μm of 2–5A for indicated times. Cell lysates were analyzed for autophagic markers by monitoring increased lipidation of LC3-II and p62 degradation which was normalized to β-actin levels. B and C, ratios of LC3-II/β-actin or p62/β-actin corresponding to the time points in A from three experiments shown as mean ± S.E. D, U3A cells were transfected with GFP-LC3 and 24 h later with 2–5A. Cells were pretreated optionally with PKR inhibitor (2-aminopurine, 5 mm) or JNK inhibitor (SP600125, 25 μm) for 1 h prior to 2–5A transfection (up to 30 h) and inhibitors were added back. The percentage of GFP+ cells showing puncta formation compared with mock-treated cells is shown. Results shown represent mean ± S.E. for three experiments, and at least 100 cells were analyzed per assay. E, activation of JNK and PKR in response to 2–5A transfection. Western blot analysis of phospho-JNK (T184, Y185), and phospho-PKR (T451) in response to 2–5A transfection (10 μm) for indicated times compared with levels of total JNK and total PKR. Activation of PKR was correlated with phospho-eIF2α. Protein loading was normalized to β-actin levels.

DISCUSSION

Our data presented here demonstrate that RNase L activation induces autophagy. Direct activation of RNase L by 2–5A stimulates autophagy as indicated by increased conversion of LC3-I to lipidated LC3-II, degradation of p62 and microscopic evaluation of GFP-LC3 puncta formation. siRNA silencing of endogenous RNase L or RNase L KO MEFs decrease autophagy significantly. WT MEFs showed increased autophagy during viral infection and inhibiting autophagy preferentially increased viral titers in infected WT MEFs compared with RNase L KO MEFs in initial cycles of viral replication. Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and components of innate signaling pathway, including cytosolic dsRNA-sensing PKR, regulate autophagy in response to viral infections (2, 49). Our results point to an important role for PKR and stress-activated JNK in RNase L-mediated autophagy.

Activation of RNase L cleaves viral and cellular RNA, including rRNA in ribosomes, generating small duplex RNAs (32, 41). Damage to rRNA can cause disassembly and turnover of ribosomes in autophagosomes by a specialized type of autophagy now termed as “ribophagy” (34, 50). In plants, a ribophagy-like process that promotes rRNA decay requires the activity of the endoribonuclease, Rns2 (51). Cleavage of cellular mRNAs by RNase L at translation sites inhibits protein synthesis (31, 52). In Purkinje cells, disassembly of actively translating polysomes to nontranslating monosomes causes sequestration into autophagosomes which then triggers ribophagy (53). It is possible that activation of RNase L triggers autophagy by a process that shares some features of ribophagy.

RNase L-mediated cleavage of 28S rRNA leads to cellular stress response that in turn activates JNK (35–37, 54). During viral infections, the host translation system is hijacked to produce large amounts of viral proteins. Enhanced protein synthesis causes misfolding of proteins that can activate ER stress-sensors like PERK, IRE1, and JNK1. Our results demonstrate activation of JNK by 2–5A which is important for induction of autophagy since inhibiting JNK activity using pharmacological inhibitors or JNK1/2 KO MEFs reduced 2–5A-induced autophagy. Role of JNK1 has been demonstrated in autophagy induced in response to oxidative stress, ER stress, mTOR pathway, cytokine stimulation, and pathogens (55). Since diverse stimuli trigger JNK-mediated autophagy, autophagy regulation has been linked to the stress response pathway. Nutrient deprivation and ceramide treatment cause JNK activation and JNK1-mediated Bcl-2 phosphorylation, which in turn promotes autophagy (11, 56). In normal growth conditions, Bcl-2 forms an autophagy-inhibitory complex with Beclin1. Induction of JNK activity causes phosphorylation of Bcl-2 on residues critical for complex formation with Beclin1 (12, 56). This causes disruption of Beclin1-Bcl-2 complex and autophagy activation. In our experiments, 2–5A caused dissociation of Beclin1-Bcl-2 complex, but was prevented by treating with the JNK inhibitor, SP600125. Simultaneously, we observed complex formation of Beclin1 with Vps34, which forms the core for nucleation of autophagosomes, a prerequisite for autophagy (6). Many viruses target Beclin1-Bcl-2 complex formation to promote or evade host responses. For instance, HSV-1 protein, ICP34.5, inhibits PKR signaling and binds to Beclin1 to inhibit autophagy (25). The viral Bcl2-like protein of KSHV and γHV68 bind Beclin1 directly and inhibit autophagy (57, 58). The HIV-1 Nef protein binds to Beclin1 and inhibits conversion of autophagosomes (59). The influenza virus induces autophagy to promote survival of infected cells. In case of hepatitis C virus (HCV), autophagic machinery is required for viral replication and translation of viral proteins (60). Therefore, RNase L-mediated JNK activation could serve an important role in balancing the outcome during viral infections by manipulating the autophagic pathway.

Several studies have demonstrated the role of IFN-inducible dsRNA-activated protein kinase R (PKR) in ER stress (61, 62). Our results show that activation of RNase L induces PKR which in turn could trigger autophagy. Gene knockdown of PKR and pharmacological inhibition of PKR activity reduced 2–5A-induced autophagy significantly. It is conceivable that PKR could be activated in these cells by ER stress or small duplex RNAs generated by RNase L activity. However, by using cells with defective STAT1-signaling (U3A) and MEFs lacking type 1 IFN receptor (IFNAR KO), we have demonstrated that an IFN feedback is not involved in inducing autophagy in response to 2–5A. We have shown previously that IFNβ promoter activity can be stimulated under similar conditions in HT1080 cells (32). Our data therefore suggest that coordinate activation of JNK and PKR have a cumulative effect on autophagy induced by RNase L.

Our results point to the role of autophagy induced by RNase L in modulating viral growth. Inhibiting autophagy in cells infected with SeV or EMCV caused significant increase in viral titers in WT MEFs compared with RNase L KO MEFs implicating the involvement of autophagy in promoting antiviral effect in the early stages of infection. During later stages, however, both EMCV and SeV appear to use autophagy to promote viral growth. Recent studies have suggested that autophagy increases the efficiency of EMCV replication on autophagosome-like vesicles that accumulate during infection (63). In our experiments, the beneficial effect of autophagy in fostering viral growth is more significant in EMCV compared with SeV. RNase L activation contributes to antiviral response by cleavage and elimination of viral RNA or mRNA, inhibition of protein synthesis via degradation of rRNA, induction of apoptosis and induction of antiviral genes (64). Our studies add another dimension to the antiviral role of RNase L by inducing autophagy during viral infections by degrading RNA and causing organelle damage.

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert Silverman, Ganes Sen, George Stark, Douglas Leaman, Shigeomi Shimizu, and Kanaga Sabapathy for providing knock-out and other cells. We also thank Rune Hartmann, Isei Tanida, Aimin Zhou, and Robert Silverman for plasmids and other valuable reagents. We thank Lauren Stanoszek (UTMC) for help with RNA chips and Agilent Bioanalyzer. We thank Douglas Leaman and Deborah Chadee for critical reading of our manuscript.

Addendum

While this work was under review, Chakrabarti et al. (65) reported that RNase L triggers autophagy in response to viral infections, consistent with our data described here.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants AI089518 (to K. M.) and startup funds from the University of Toledo.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4.

- Bcl-2

- B-cell lymphoma-2

- RNase L

- ribonuclease L

- JNK

- c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- PKR

- double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase R

- Vps34

- vacuolar protein sorting 34

- IFN

- interferon

- LC3

- microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3

- 3-MA

- 3-methyladenine

- BafA1

- Bafilomycin A1

- MEFs

- mouse embryonic fibroblasts

- KO

- knock-out

- EMCV

- Encephalomyocarditis virus

- SeV

- Sendai virus

- MOI

- multiplicity of infection

- HAU

- hemagglutinin units.

REFERENCES

- 1. Shoji-Kawata S., Levine B. (2009) Autophagy, antiviral immunity, and viral countermeasures. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1793, 1478–1484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Saitoh T., Akira S. (2010) Regulation of innate immune responses by autophagy-related proteins. J. Cell Biol. 189, 925–935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dreux M., Chisari F. V. (2010) Viruses and the autophagy machinery. Cell Cycle 9, 1295–1307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cao Y., Klionsky D. J. (2007) Physiological functions of Atg6/Beclin 1: a unique autophagy-related protein. Cell Res. 17, 839–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kang R., Zeh H. J., Lotze M. T., Tang D. (2011) The Beclin 1 network regulates autophagy and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 18, 571–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. He C., Levine B. (2010) The Beclin 1 interactome. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 22, 140–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liang X. H., Kleeman L. K., Jiang H. H., Gordon G., Goldman J. E., Berry G., Herman B., Levine B. (1998) Protection against fatal Sindbis virus encephalitis by beclin, a novel Bcl-2-interacting protein. J. Virol. 72, 8586–8596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maiuri M. C., Le Toumelin G., Criollo A., Rain J. C., Gautier F., Juin P., Tasdemir E., Pierron G., Troulinaki K., Tavernarakis N., Hickman J. A., Geneste O., Kroemer G. (2007) Functional and physical interaction between Bcl-X(L) and a BH3-like domain in Beclin-1. EMBO J. 26, 2527–2539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Oberstein A., Jeffrey P. D., Shi Y. (2007) Crystal structure of the Bcl-XL-Beclin 1 peptide complex: Beclin 1 is a novel BH3-only protein. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 13123–13132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pattingre S., Tassa A., Qu X., Garuti R., Liang X. H., Mizushima N., Packer M., Schneider M. D., Levine B. (2005) Bcl-2 antiapoptotic proteins inhibit Beclin 1-dependent autophagy. Cell 122, 927–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wei Y., Pattingre S., Sinha S., Bassik M., Levine B. (2008) JNK1-mediated phosphorylation of Bcl-2 regulates starvation-induced autophagy. Mol. Cell 30, 678–688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wei Y., Sinha S., Levine B. (2008) Dual role of JNK1-mediated phosphorylation of Bcl-2 in autophagy and apoptosis regulation. Autophagy 4, 949–951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zalckvar E., Berissi H., Mizrachy L., Idelchuk Y., Koren I., Eisenstein M., Sabanay H., Pinkas-Kramarski R., Kimchi A. (2009) DAP-kinase-mediated phosphorylation on the BH3 domain of beclin 1 promotes dissociation of beclin 1 from Bcl-XL and induction of autophagy. EMBO Rep. 10, 285–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee H. K., Iwasaki A. (2008) Autophagy and antiviral immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 20, 23–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Delgado M. A., Elmaoued R. A., Davis A. S., Kyei G., Deretic V. (2008) Toll-like receptors control autophagy. EMBO J. 27, 1110–1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shi C. S., Kehrl J. H. (2008) MyD88 and Trif target Beclin 1 to trigger autophagy in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 33175–33182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jounai N., Takeshita F., Kobiyama K., Sawano A., Miyawaki A., Xin K. Q., Ishii K. J., Kawai T., Akira S., Suzuki K., Okuda K. (2007) The Atg5 Atg12 conjugate associates with innate antiviral immune responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 14050–14055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lei Y., Wen H., Yu Y., Taxman D. J., Zhang L., Widman D. G., Swanson K. V., Wen K. W., Damania B., Moore C. B., Giguère P. M., Siderovski D. P., Hiscott J., Razani B., Semenkovich C. F., Chen X., Ting J. P. (2012) The mitochondrial proteins NLRX1 and TUFM form a complex that regulates type I interferon and autophagy. Immunity 36, 933–946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. He B. (2006) Viruses, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and interferon responses. Cell Death Differ. 13, 393–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ogata M., Hino S., Saito A., Morikawa K., Kondo S., Kanemoto S., Murakami T., Taniguchi M., Tanii I., Yoshinaga K., Shiosaka S., Hammarback J. A., Urano F., Imaizumi K. (2006) Autophagy is activated for cell survival after endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 9220–9231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kouroku Y., Fujita E., Tanida I., Ueno T., Isoai A., Kumagai H., Ogawa S., Kaufman R. J., Kominami E., Momoi T. (2007) ER stress (PERK/eIF2alpha phosphorylation) mediates the polyglutamine-induced LC3 conversion, an essential step for autophagy formation. Cell Death Differ. 14, 230–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Høyer-Hansen M., Jäättelä M. (2007) Connecting endoplasmic reticulum stress to autophagy by unfolded protein response and calcium. Cell Death Differ. 14, 1576–1582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wong C. H., Iskandar K. B., Yadav S. K., Hirpara J. L., Loh T., Pervaiz S. (2010) Simultaneous induction of non-canonical autophagy and apoptosis in cancer cells by ROS-dependent ERK and JNK activation. PloS One 5, e9996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Komiya K., Uchida T., Ueno T., Koike M., Abe H., Hirose T., Kawamori R., Uchiyama Y., Kominami E., Fujitani Y., Watada H. (2010) Free fatty acids stimulate autophagy in pancreatic β-cells via JNK pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 401, 561–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tallóczy Z., Jiang W., Virgin H. W., 4th, Leib D. A., Scheuner D., Kaufman R. J., Eskelinen E. L., Levine B. (2002) Regulation of starvation- and virus-induced autophagy by the eIF2α kinase signaling pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 190–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tallóczy Z., Virgin H. W., 4th, Levine B. (2006) PKR-dependent autophagic degradation of herpes simplex virus type 1. Autophagy 2, 24–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Orvedahl A., Alexander D., Talloczy Z., Sun Q., Wei Y., Zhang W., Burns D., Leib D. A., Levine B. (2007) HSV-1 ICP34.5 confers neurovirulence by targeting the Beclin 1 autophagy protein. Cell Host Microbe 1, 23–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kerr I. M., Wreschner D. H., Silverman R. H., Cayley P. J., Knight M. (1981) The 2–5A (pppA2'p5'A2'p5'A) and protein kinase systems in interferon-treated and control cells. Adv. Cyclic Nucleotide Res. 14, 469–478 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhou A., Hassel B. A., Silverman R. H. (1993) Expression cloning of 2–5A-dependent RNAase: a uniquely regulated mediator of interferon action. Cell 72, 753–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Floyd-Smith G., Slattery E., Lengyel P. (1981) Interferon action: RNA cleavage pattern of a (2'-5')oligoadenylate-dependent endonuclease. Science 212, 1030–1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wreschner D. H., James T. C., Silverman R. H., Kerr I. M. (1981) Ribosomal RNA cleavage, nuclease activation and 2–5A(ppp(A2'p)nA) in interferon-treated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 9, 1571–1581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Malathi K., Dong B., Gale M., Jr., Silverman R. H. (2007) Small self-RNA generated by RNase L amplifies antiviral innate immunity. Nature 448, 816–819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Silverman R. H., Cayley P. J., Knight M., Gilbert C. S., Kerr I. M. (1982) Control of the ppp(a2'p)nA system in HeLa cells. Effects of interferon and virus infection. Eur. J. Biochem. 124, 131–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cebollero E., Reggiori F., Kraft C. (2012) Reticulophagy and ribophagy: regulated degradation of protein production factories. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 182834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Iordanov M. S., Paranjape J. M., Zhou A., Wong J., Williams B. R., Meurs E. F., Silverman R. H., Magun B. E. (2000) Activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase by double-stranded RNA and encephalomyocarditis virus: involvement of RNase L, protein kinase R, and alternative pathways. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 617–627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li G., Xiang Y., Sabapathy K., Silverman R. H. (2004) An apoptotic signaling pathway in the interferon antiviral response mediated by RNase L and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 1123–1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Malathi K., Paranjape J. M., Ganapathi R., Silverman R. H. (2004) HPC1/RNASEL mediates apoptosis of prostate cancer cells treated with 2',5'-oligoadenylates, topoisomerase I inhibitors, and tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand. Cancer Res. 64, 9144–9151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tanida I., Yamaji T., Ueno T., Ishiura S., Kominami E., Hanada K. (2008) Consideration about negative controls for LC3 and expression vectors for four colored fluorescent protein-LC3 negative controls. Autophagy 4, 131–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hartmann R., Justesen J., Sarkar S. N., Sen G. C., Yee V. C. (2003) Crystal structure of the 2'-specific and double-stranded RNA-activated interferon-induced antiviral protein 2'-5'-oligoadenylate synthetase. Mol. Cell 12, 1173–1185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Thakur C. S., Jha B. K., Dong B., Das Gupta J., Silverman K. M., Mao H., Sawai H., Nakamura A. O., Banerjee A. K., Gudkov A., Silverman R. H. (2007) Small-molecule activators of RNase L with broad-spectrum antiviral activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 9585–9590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Malathi K., Paranjape J. M., Bulanova E., Shim M., Guenther-Johnson J. M., Faber P. W., Eling T. E., Williams B. R., Silverman R. H. (2005) A transcriptional signaling pathway in the IFN system mediated by 2'-5'-oligoadenylate activation of RNase L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 14533–14538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mizushima N., Yoshimori T., Levine B. (2010) Methods in mammalian autophagy research. Cell 140, 313–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Silverman R. H., Skehel J. J., James T. C., Wreschner D. H., Kerr I. M. (1983) rRNA cleavage as an index of ppp(A2'p)nA activity in interferon-treated encephalomyocarditis virus-infected cells. J. Virol. 46, 1051–1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Samuel C. E. (1993) The eIF-2α protein kinases, regulators of translation in eukaryotes from yeasts to humans. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 7603–7606 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gusella G. L., Musso T., Rottschafer S. E., Pulkki K., Varesio L. (1995) Potential requirement of a functional double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR) for the tumoricidal activation of macrophages by lipopolysaccharide or IFN-αβ, but not IFN-γ. J. Immunol. 154, 345–354 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pattingre S., Bauvy C., Carpentier S., Levade T., Levine B., Codogno P. (2009) Role of JNK1-dependent Bcl-2 phosphorylation in ceramide-induced macroautophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 2719–2728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhou A., Paranjape J., Brown T. L., Nie H., Naik S., Dong B., Chang A., Trapp B., Fairchild R., Colmenares C., Silverman R. H. (1997) Interferon action and apoptosis are defective in mice devoid of 2',5'-oligoadenylate-dependent RNase L. EMBO J. 16, 6355–6363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. McKendry R., John J., Flavell D., Müller M., Kerr I. M., Stark G. R. (1991) High-frequency mutagenesis of human cells and characterization of a mutant unresponsive to both α and γ interferons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 11455–11459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Deretic V. (2012) Autophagy as an innate immunity paradigm: expanding the scope and repertoire of pattern recognition receptors. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 24, 21–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kraft C., Deplazes A., Sohrmann M., Peter M. (2008) Mature ribosomes are selectively degraded upon starvation by an autophagy pathway requiring the Ubp3p/Bre5p ubiquitin protease. Nature Cell Biol. 10, 602–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. MacIntosh G. C., Bassham D. C. (2011) The connection between ribophagy, autophagy and ribosomal RNA decay. Autophagy 7, 662–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Silverman R. H. (2007) Viral encounters with 2',5'-oligoadenylate synthetase and RNase L during the interferon antiviral response. J. Virol. 81, 12720–12729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Baltanás F. C., Casafont I., Weruaga E., Alonso J. R., Berciano M. T., Lafarga M. (2011) Nucleolar disruption and cajal body disassembly are nuclear hallmarks of DNA damage-induced neurodegeneration in purkinje cells. Brain Pathol. 21, 374–388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rusch L., Zhou A., Silverman R. H. (2000) Caspase-dependent apoptosis by 2′,5′-oligoadenylate activation of RNase L is enhanced by IFN-beta. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 20, 1091–1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kroemer G., Mariño G., Levine B. (2010) Autophagy and the integrated stress response. Mol. Cell 40, 280–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pattingre S., Bauvy C., Levade T., Levine B., Codogno P. (2009) Ceramide-induced autophagy: to junk or to protect cells? Autophagy 5, 558–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ku B., Woo J. S., Liang C., Lee K. H., Hong H. S., E X., Kim K. S., Jung J. U., Oh B. H. (2008) Structural and biochemical bases for the inhibition of autophagy and apoptosis by viral BCL-2 of murine γ-herpesvirus 68. PLoS pathogens 4, e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sinha S., Colbert C. L., Becker N., Wei Y., Levine B. (2008) Molecular basis of the regulation of Beclin 1-dependent autophagy by the γ-herpesvirus 68 Bcl-2 homolog M11. Autophagy 4, 989–997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Espert L., Varbanov M., Robert-Hebmann V., Sagnier S., Robbins I., Sanchez F., Lafont V., Biard-Piechaczyk M. (2009) Differential role of autophagy in CD4 T cells and macrophages during X4 and R5 HIV-1 infection. PloS One 4, e5787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Dreux M., Gastaminza P., Wieland S. F., Chisari F. V. (2009) The autophagy machinery is required to initiate hepatitis C virus replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 14046–14051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Williams B. R. (2001) Signal integration via PKR. Science's STKE: Signal Transduction Knowledge Environment 2001, re2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Nakamura T., Furuhashi M., Li P., Cao H., Tuncman G., Sonenberg N., Gorgun C. Z., Hotamisligil G. S. (2010) Double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase links pathogen sensing with stress and metabolic homeostasis. Cell 140, 338–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zhang Y., Li Z., Ge X., Guo X., Yang H. (2011) Autophagy promotes the replication of encephalomyocarditis virus in host cells. Autophagy 7, 613–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Silverman R. H. (2007) A scientific journey through the 2–5A/RNase L system. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 18, 381–388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Chakrabarti A., Ghosh P. K., Banerjee S., Gaughan C., Silverman R. H. (2012) RNase L Triggers Autophagy in Response to Viral Infections. J. Virol. 86, 11311–11321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]