Background: The anti-inflammatory properties of apolipoproteins are incompletely defined.

Results: Apolipoprotein A-I and E mimetic peptides suppress CXCR2-dependent neutrophil migration in vivo. Mimetic L-37pA itself induces formyl peptide receptor-2-dependent chemotaxis.

Conclusion: Apolipoprotein mimetics display complex structure-activity relationships to multiple chemotactic receptors.

Significance: Apolipoproteins and their mimetics regulate leukocyte migration.

Keywords: Apolipoproteins, Chemotaxis, Innate immunity, Lung, Neutrophil

Abstract

The plasma lipoprotein-associated apolipoproteins (apo) A-I and apoE have well described anti-inflammatory actions in the cardiovascular system, and mimetic peptides that retain these properties have been designed as therapeutics. The anti-inflammatory mechanisms of apolipoprotein mimetics, however, are incompletely defined. Whether circulating apolipoproteins and their mimetics regulate innate immune responses at mucosal surfaces, sites where transvascular emigration of leukocytes is required during inflammation, remains unclear. Herein, we report that Apoai−/− and Apoe−/− mice display enhanced recruitment of neutrophils to the airspace in response to both inhaled lipopolysaccharide and direct airway inoculation with CXCL1. Conversely, treatment with apoA-I (L-4F) or apoE (COG1410) mimetic peptides reduces airway neutrophilia. We identify suppression of CXCR2-directed chemotaxis as a mechanism underlying the apolipoprotein effect. Pursuing the possibility that L-4F might suppress chemotaxis through heterologous desensitization, we confirmed that L-4F itself induces chemotaxis of human PMNs and monocytes. L-4F, however, fails to induce a calcium flux. Further exploring structure-function relationships, we studied the alternate apoA-I mimetic L-37pA, a bihelical analog of L-4F with two Leu-Phe substitutions. We find that L-37pA induces calcium and chemotaxis through formyl peptide receptor (FPR)2/ALX, whereas its D-stereoisomer (i.e. D-37pA) blocks L-37pA signaling and induces chemotaxis but not calcium flux through an unidentified receptor. Taken together, apolipoprotein mimetic peptides are novel chemotactic agents that possess complex structure-activity relationships to multiple receptors, displaying anti-inflammatory efficacy against innate immune responses in the airway.

Introduction

In recent years, it has been increasingly recognized that high density lipoprotein (HDL), a multimolecular particle composed of apolipoproteins (e.g. apolipoprotein (apo) A-I and apoE), lipids, and other cargo, has potent and wide ranging anti-inflammatory properties in addition to its well known function as a vehicle for cholesterol transport in the serum. HDL down-regulates adhesion molecules on endothelium and leukocytes, sequesters and reduces oxidized lipids, suppresses myeloid cell production in the bone marrow, and attenuates pro-inflammatory signaling by Toll-like receptors (1, 2). Many of these anti-inflammatory effects of HDL have been attributed to apoA-I, and in particular, to the 10 tandem amphipathic α-helices of apoA-I, a lipid-binding motif it shares with apoE and other apolipoproteins. Exploiting this discovery, several anti-inflammatory α-helical apoA-I mimetic peptides (e.g. the 18-amino acid peptide L-4F (3–5)) have now been designed, and some are under development for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and/or other inflammatory disorders. Amphipathic α-helical apoE mimetic peptides (e.g. the 12-amino acid peptide COG1410 (6)) have similarly been developed that display anti-inflammatory activity not only in the cardiovascular system, but also in the brain and other organs (6).

ApoA-I and apoE are expressed in the lung by structural (i.e. alveolar epithelial) and hematopoietic (e.g. alveolar macrophages) cells, and they and their mimetic peptides have recently been shown to regulate physiology and adaptive immunity of the airway. Thus, Apoai−/− mice have increased lung inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness, whereas treatment with two apoA-I mimetics (L-4F or 5A) reduces inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness in mouse models of asthma (7, 8). Apoe−/− mice similarly develop exaggerated airway disease in an asthma model, and an apoE mimetic peptide rescues this response (9). Studies on lung and other disease models have generally defined the anti-inflammatory effects of apolipoproteins on tissue-resident cells in various organs, as well as on effector functions of leukocytes. Whether apolipoproteins and their mimetics attenuate end-organ inflammation through the unifying mechanism of modulating leukocyte migration to tissues has not been defined.

Herein, we report that Apoai−/− and Apoe−/− mice have enhanced recruitment of neutrophils (PMNs)3 and monocytes to the airspace in response to inhaled lipopolysaccharide (LPS), as well as enhanced airway neutrophilia in response to direct airway inoculation with CXCL1. Conversely, treatment with apoA-I (L-4F) and apoE (COG1410) mimetics reduces PMN/monocyte recruitment to the airway under these conditions. We identify suppression of chemokine-directed chemotaxis as a mechanism underlying the apolipoprotein effect. ApoA-I protein and L-4F suppress chemotaxis of murine PMNs to CXCL2; this is associated with reduced PMN surface display of CXCR2 in the case of L-4F. Pursuing the possibility that L-4F might suppress chemotaxis through heterologous desensitization (i.e. through itself acting as a chemoattractant), we confirmed that L-4F indeed induces chemotaxis of human PMNs and monocytes. L-4F, however, neither induces a calcium flux in PMNs or monocytes, nor induces chemotaxis through CXCR2, CCR2, formyl peptide receptor (FPR) 1, or FPR2/ALX in transfected HEK293 cells, making the identity of its receptor uncertain. Further exploring structure-function relationships, we studied an alternate apoA-I mimetic peptide, L-37pA, a bihelical version of L-4F with two Leu-Phe substitutions (10). We find that L-37pA induces chemotaxis through the multi-recognition receptor FPR2/ALX, whereas its D-stereoisomer (D-37pA) (11) blocks L-37pA signaling and induces chemotaxis through a different, yet unidentified receptor. Taken together, we report that apolipoprotein mimetic peptides are novel PMN and monocyte chemotactic agents that possess complex structure-function activity relationships to multiple receptors.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

Escherichia coli 0111:B4 LPS and formyl-Met-Leu-Phe (fMLF) were from Sigma. CXCL1/KC and CXCL2/MIP-2 were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). ApoA-I was purified as previously described (12). WKYMVm (designated W peptide) and MMK-1 were synthesized and purified by the Department of Biochemistry, Colorado State University (Fort Collins, CO). IL-8 (CXCL8) was from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ). Fura-2 was from Invitrogen.

Synthesis of Apolipoprotein Mimetic Peptides (Table 1)

TABLE 1.

Apolipoprotein mimetic and control peptides

| Peptides | Sequence | Mr |

|---|---|---|

| L-4F | Ac-DWFKAFYDKVAEKFKEAF-NH2 | 2310.64 |

| Sc-4Fa | Ac-DWFAKDYFKKAFVEEFAK-NH2 | 2310.64 |

| 37pAb | DWLKAFYDKVAEKLKEAFPDWLKAFYDKVAEKLKEAF | 4482.2 |

| Sc-37pAa | FWFDAYFEVVDKALLAYKPALDKEKKAEFKEKLDWKA | 4482.2 |

| COG1410 | Ac-AS(Aib)LRKL(Aib)-KRLL-NH2 | 1408.8 |

| 264 | Ac-AS(Aib)LRKL(Aib)KR-NH2 | 1182.48 |

a Scrambled versions of L-4F and L-37pA, respectively.

b This peptide was synthesized with either L- or D-amino acids (i.e. L-37pA or D-37pA).

COG1410 (Ac-AS(Aib)LRKL(Aib)-KRLL-NH2), a peptide derived from apoE residues 138–149 with Aib (aminoisobutyric acid) substitutions at positions 140 and 145 (6, 13) was synthesized by the Peptide Synthesis Laboratory at the University of North Carolina (Chapel Hill, NC) to a purity of >95%. Peptide 264 (Ac-AS(Aib)LRKL(Aib)KR-NH2), a negative control for COG1410 that displays reduced anti-inflammatory activity in attenuating the LPS response (14), was synthesized to similar specifications at the University of North Carolina. L-4F (Ac-DWFKAFYDKVAEKFKEAF-NH2) and its scrambled version, sc-4F (Ac-DWFAKDYF-KKAFVEEFAK-NH2) (4), were also synthesized to >95% purity at the University of North Carolina. L-37pA (DWLKAFYDKVAEKLKEAF-P-DWLKAFYDKVAEKLKEAF) and D-37pA (i.e. D-amino acid version of 37pA) were synthesized by a solid-phase procedure as previously reported (10). A scrambled version of L-37pA, sc-37pA, was synthesized (FWFDAYFEVVDKALLAYKPALDKEKKAEFKEKLDWKA).

Mice

Female mice (8–12 weeks old, weighing 15–22 g) were used in all experiments. Apoai−/− (B6.129P2-Apoa1tm1Unc/J), Apoe−/− (B6.129P2-Apoetm1Unc/J) (both backcrossed 10 generations onto C57BL/6), and wild type C57BL/6 mice were all from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). All experiments were performed in accordance with the Animal Welfare Act and the United States Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals after review by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the NIEHS, National Institutes of Health.

In Vivo Exposures

Mice were injected intravenously (150 μl in saline) with 20 mg/kg of L-4F or sc-4F peptide (control for L-4F), or with 1.2 mg/kg of COG1410 or 264 peptide (control for COG1410) 2 h prior to pulmonary exposures, similar to past reports (4, 13). LPS exposure was by aerosol (300 μg/ml, 20 min) and KC exposure by intratracheal delivery (0.25 or 0.5 μg/60 μl by oropharyngeal aspiration), both as previously described (15). L-37pA or scrambled L-37pA (100 μg/60 μl) were also delivered intratracheally.

Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid Collection and Analysis

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid was collected immediately following sacrifice, and total leukocyte and differential counts were performed, as previously described (15). Cytokines were quantified by a multiplex assay (Bio-Plex, Bio-Rad) per the manufacturer's instructions.

Neutrophil and Monocyte Isolation

Mature murine bone marrow PMNs were isolated from mouse femurs and tibias by discontinuous Percoll gradient centrifugation, as previously described (15). This preparation yields >95% PMNs (data not shown). Human peripheral blood monocytes were isolated from buffy coats (NIH Clinical Center, Transfusion Medicine Department, Bethesda, MD) enriched for mononuclear cells by using an iso-osmotic Percoll gradient, and neutrophils by dextran sedimentation of the buffy coat, both as previously described (16). The purity of the cell preparations was confirmed by morphology to be >90% for monocytes and >98% for neutrophils.

Transfected HEK293 Cells

Parental HEK293 cells were stably transfected with FPR1, FPR2/ALX, CCR2, or CXCR2 as previously described (16). All cell lines were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (Hyclone, Logan, UT), 1 mm glutamine (Invitrogen), and 800 μg/ml of geneticin (G418; Invitrogen).

In Vitro Chemotaxis Assays

Bone marrow-isolated murine PMNs (1 × 106, 0.1 ml of RPMI, 1% FBS) were seeded into the upper chamber of a 96-well transwell system (polycarbonate membrane, 3.0 μm pore) (Corning, Corning, NY) after pretreatment (apoA-I, peptide (L-4F or sc-4F), or buffer control for 30 min), staining (2 μm calcein-AM, 30 min), and then washing in 1× in Hanks' balanced salt solution. Media (0.1 ml) with or without MIP-2 (50 ng/ml) was added to the lower chamber. Fluorescence was monitored in the lower chamber every 2 min in triplicate over a time course (34 min, 37 °C), using Gen5 software on a Synergy 2 plate reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT), as previously described (15). Directional migration (i.e. chemotaxis) was derived at each time point by subtracting the fluorescence signal of nondirectionally migrating cells in control wells with no chemoattractant, and then normalizing this as a % of total cellular fluorescence by indexing it to labeled cells plated directly into the lower chamber (15). Chemotaxis of human neutrophils, human monocytes, and transfected HEK293 cells in response to peptides, IL-8, and/or fMLF was measured using a 48-well microchemotaxis chamber technique (Neuroprobe, Cabin John, MD) system with 5-μm pore-sized polycarbonate membranes for the former two cell types, and 10-μm pore-sized membranes for receptor-transfected HEK293 cells, as previously described (17). A 25-μl aliquot of chemoattractant diluted in chemotaxis medium (RPMI 1640, 1% BSA, 25 mm HEPES) was placed in the lower compartment, and 50 μl of cell suspension (106 cells/ml in chemotaxis medium) was placed in the upper compartment. The chamber was incubated (37 °C, humidified air with 5% CO2; 90 min for monocytes, 60 min for neutrophils, 240 min for HEK293 cells), after which the filter was removed, fixed, and stained with Diff-Quik (Harlew, Gibbstown, NJ). The number of migrated cells in three high-powered fields (×400) was counted by light microscopy after coding the samples. Results are obtained from triplicate samples and are representative of at least 5 experiments. Results are expressed as the chemotaxis index (mean ± S.D.), which represents the fold-increase in the number of migrated cells in response to chemoattractants over spontaneous cell migration (to control medium).

Calcium Mobilization Measurements

Calcium mobilization of monocytes, neutrophils, and HEK293 cells was assayed by measuring fluorescence (LS-50B spectrometer, PerkinElmer Life Sciences) of Fura-2-loaded cells, and calculating the ratio of fluorescence at 340 and 380 nm (FL WinLab, PerkinElmer Life Sciences), as previously reported (17). The assays were performed at least five times and results from representative experiments are shown.

Peripheral Blood Leukocyte Typing and Enumeration

Murine blood samples were analyzed using the HEMAVET 1700 hematology analyzer (Drew Scientific, Inc.). Manual WBC differential counts were reported and smear estimates were used to confirm values.

Flow Cytometry

Anti-CXCR2 (PerCP/Cy5.5), -Gr-1 (FITC), and isotype control antibodies were from Biolegend (San Diego, CA). Cells (peripheral blood or isolated bone marrow neutrophils) were stained and flow cytometry was performed using an LSR II (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR) and FCS Express (De Novo Software, Los Angeles, CA) software.

Statistical Analysis

Analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism statistical software (San Diego, CA). Data are represented as mean ± S.E. Two-tailed Student's t test was applied for comparisons of two groups, and analysis of variance for analyses of three or more groups. For all tests, p < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

ApoE/A-I Deficiency and Supplementation Regulate PMN Influx into LPS-exposed Airway

ApoE and ApoA-I, major protein components of circulating HDL particles, have anti-inflammatory effects on several cell types in the cardiovascular system. Moreover, by binding LPS in the bloodstream and dampening systemic inflammation, intravenous apoA-I supplementation attenuates secondary injury in the lung and other peripheral organs during endotoxemia (4, 18). ApoA-I and apoE are also expressed by airway-resident cells (19, 20). However, the role of apolipoproteins in innate immunity of the airway and other mucosal surfaces, sites at which inflammatory responses to environmental stimuli require both local cellular responses and trans-tissue migration of circulating leukocytes, remains undefined.

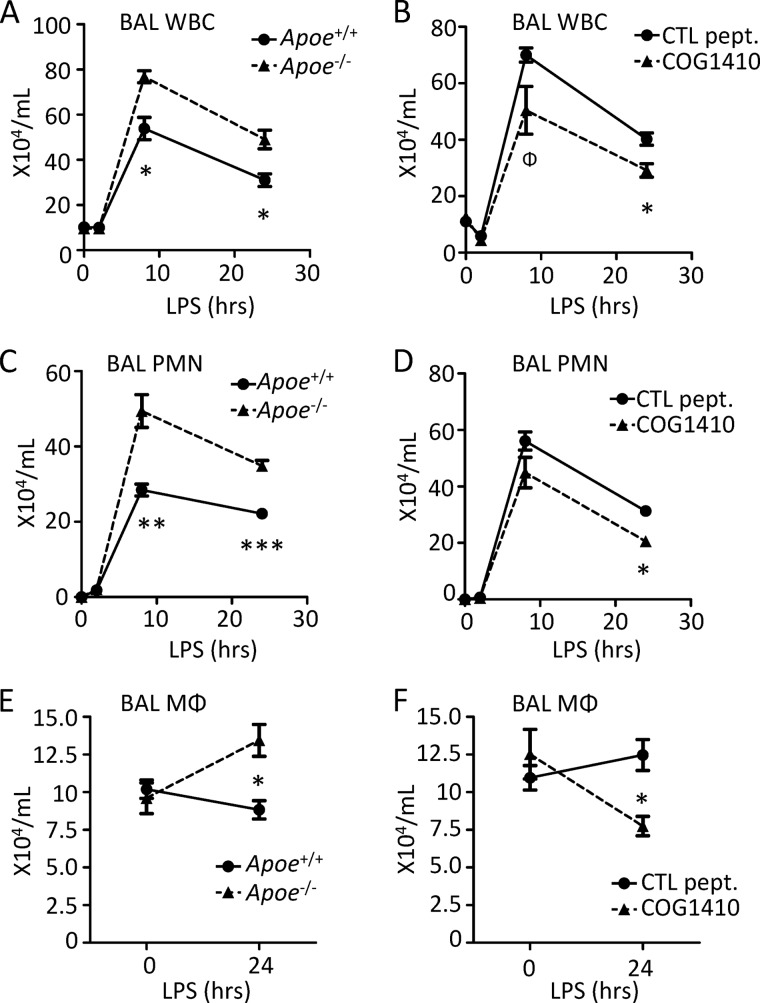

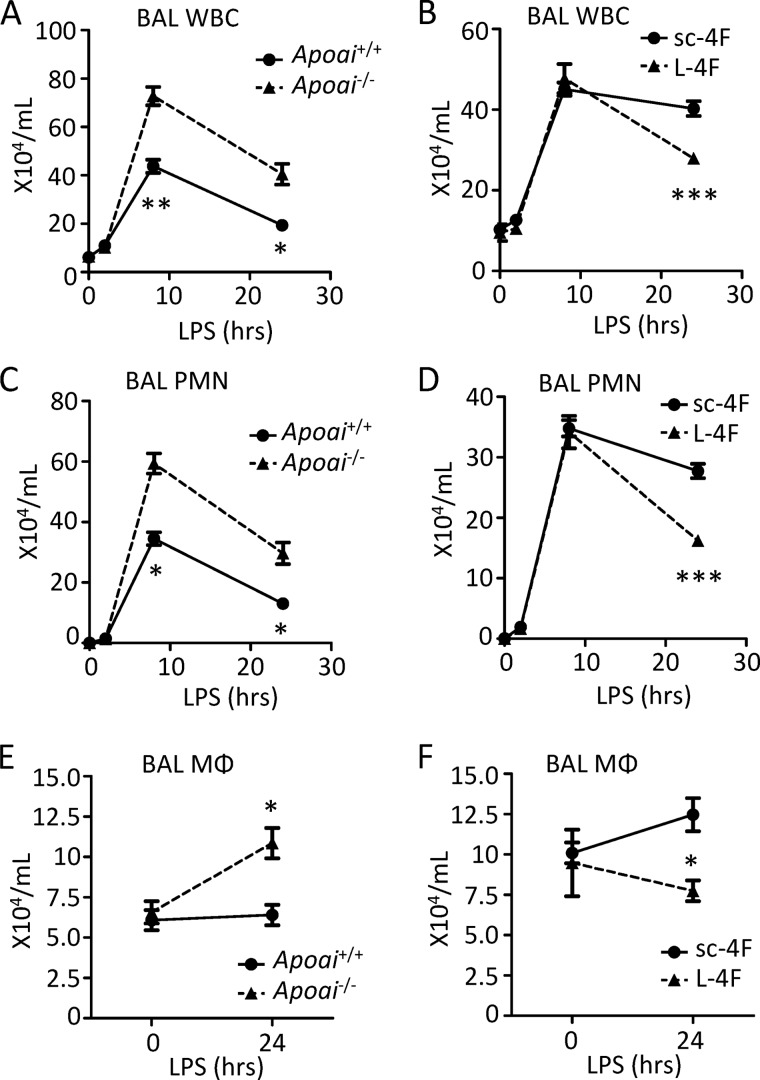

In an effort to define possible regulatory roles for apoA-I and apoE in the pulmonary innate immune response, we exposed Apoai−/− and Apoe−/− mice (and wild type controls) to inhaled LPS and then quantified PMN influx into the airspace, a well established, disease-relevant summary measure of the response to LPS in the lung (15). As shown in panels A, C, and E of Figs. 1 and 2, both apolipoprotein-deficient strains recruited higher numbers of leukocytes to the airspace than WT controls. In addition to an increase in recruited PMNs, increased macrophage numbers were also observed in the airway 24 h post-LPS, consistent with increased recruitment of macrophage precursors (i.e. monocytes) to the alveolus.

FIGURE 1.

ApoE deficiency and supplementation with peptide have reciprocal effects on leukocyte trafficking to inflamed lung. A, C, and E, Apoe+/+ and Apoe−/− mice were exposed to inhaled LPS, and then bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) total leukocytes (WBC) (A), neutrophils (PMNs) (C), and macrophages (MΦ) (E) were quantified at the indicated post-exposure time points. B, D, and F, Apoe+/+ (C57BL/6) mice were pretreated intravenously with 1.2 mg/kg of COG1410 or control (CTL) peptide 264 2 h before LPS inhalation. BAL WBCs (B), PMNs (D), and MΦ (F) were then quantified at the indicated post-LPS time points. Data are mean ± S.E. n = 4–5 mice (A, B, and D); n = 5–10 mice (E and F); and n = 9–10 mice (C) per condition/time point (*, p < 0.01; **, p < 0.001; ***, p < 0.0001; Φ, p = 0.058).

FIGURE 2.

ApoA-I deficiency and supplementation with peptide have reciprocal effects on leukocyte trafficking to inflamed lung. A, C, and E, Apoai+/+ and Apoai−/− mice were exposed to inhaled LPS, and then bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) total leukocytes (WBC) (A), neutrophils (PMNs) (C), and macrophages (MΦ) (E) were quantified at the indicated post-exposure time points. B, D, and F, Apoai+/+ (C57BL/6) mice were pretreated intravenously with 20 mg/kg of L-4F or scrambled control peptide (sc-4F) 2 h before LPS inhalation. BAL WBCs (B), PMNs (D), and MΦ (F) were then quantified at the indicated post-LPS time points. Data are mean ± S.E. n = 9–10 mice per condition/time point (B, D, and F) (*, p < 0.01; **, p < 0.001; ***, p < 0.0001).

Synthetic peptides have been designed that mimic the class A amphipathic α-helical domains of apoA-I (i.e. peptide l-4F (4)) and apoE (i.e. peptide COG1410 (6)) and that retain the anti-inflammatory activity, including in the context of LPS exposure, of their parental holoproteins (Table 1). Notably, as shown in Fig. 1 (panels B, D, and F), WT mice pretreated intravenously with COG1410 2 h before LPS inhalation recruited fewer PMNs and macrophages to the airspace than WT counterparts pretreated with 264, a truncated control peptide that has reduced anti-inflammatory activity against LPS (14). Similarly, L-4F-pretreated WT mice recruited fewer airway PMNs and macrophages 24 h post-LPS inhalation than counterparts pretreated with a scrambled, non-helical version of L-4F (i.e. sc-4F (4)) (Fig. 2, B, D, and F). Taken together, these data suggest that deficiency of apoE and apoA-I is associated with enhanced trafficking of PMNs and monocytes to the LPS-exposed airspace, whereas supplementation of both using mimetic peptides conversely suppresses influx of phagocytes to the airspace.

PMNs migrate into the airway in response to alveolar cytokines and chemokines produced by lung-resident sentinel cells (e.g. alveolar macrophages) upon their encounter with LPS (15). However, profiling a panel of cytokines (IL-1β, G-CSF) and chemokines (CXCL1/KC, CXCL2/MIP-2) of established role in PMN influx into the airspace (15) indicated no significant differences among apolipoprotein genotypes/treatments (data not shown). This result, taken together with the efficacy of brief (2 h) intravenous exposure to peptide, suggested that the predominant effect of apolipoproteins on PMN influx to the airway might stem from direct effects on the responsiveness of circulating PMNs to chemokines (i.e. migration) rather than on effects upon the local LPS response in the alveolus.

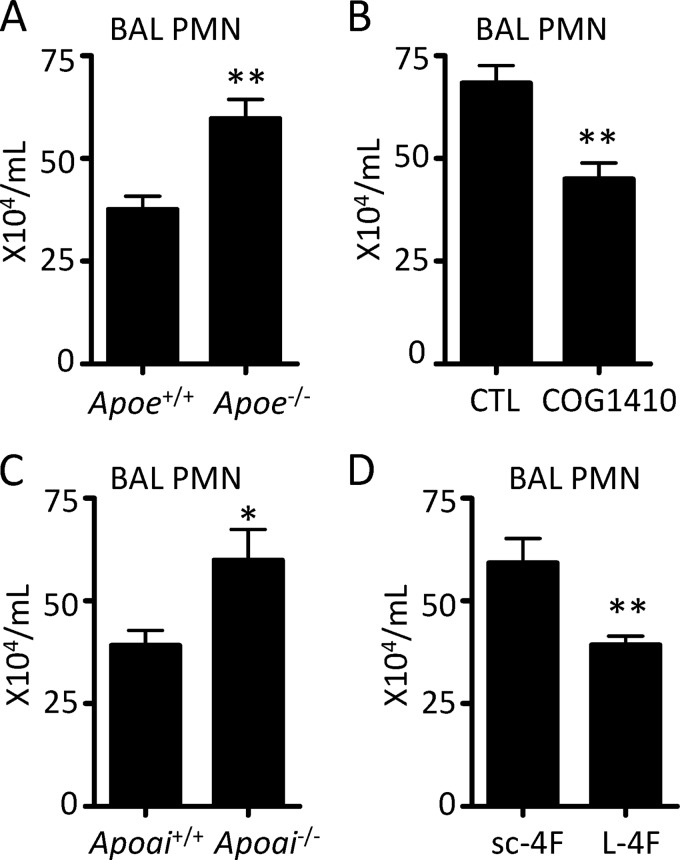

ApoE/A-I Deficiency and Supplementation Regulate PMN Migration into the CXCL1-inoculated Airway

To more precisely define whether apolipoproteins and their mimetics regulate chemokine-induced PMN migration in vivo, we inoculated the airway of naive mice with CXCL1 and then quantified PMN influx into the airway 4 h later, as reported (15). As shown in Fig. 3, parallel results were observed to those seen with LPS exposure. Apoe−/− and Apoai−/− mice displayed enhanced influx of PMNs into the airspace compared with WT counterparts, whereas COG1410- or L-4F-pretreated mice had less PMN influx than control peptide-treated counterparts. Naive Apoai−/− and Apoe−/− mice had equivalent peripheral blood PMN counts to WT controls (data not shown), thus excluding peripheral neutrophilia as an underlying explanation for the increased PMNs recruited to the airway. These findings thus supported the premise that apolipoproteins might suppress PMN migration.

FIGURE 3.

Apolipoprotein deficiency and supplementation with peptide have reciprocal effects on PMN migration to the chemokine-inoculated airspace. Apoe−/− (A) or Apoai−/− (C) mice and corresponding WT controls received 0.5 μg of CXCL1 intrapulmonary, and the BAL PMNs were quantified 4 h later. Wild type (C57BL/6) mice pretreated intravenously at −2 h with either 1.2 mg/kg of COG1410 versus control peptide (B), or with 20 mg/kg of L-4F versus sc-4F (D) had BAL PMNs quantified 4 h after intrapulmonary administration of CXCL1. Data are mean ± S.E. and represent n = 6–10 mice per condition (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01).

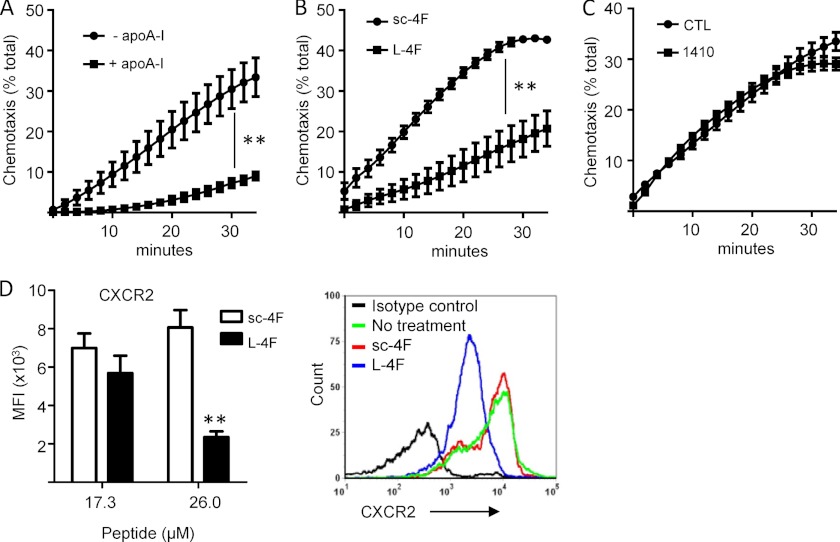

ApoA-I and Mimetic Peptides Suppress CXCR2-dependent PMN Chemotaxis

Whereas two reports have found that HDL and apoA-I suppress monocyte chemotaxis through direct cellular effects (21, 22), the only report of which we are aware that tested apolipoprotein effects on chemotaxis in PMNs found that neither HDL, apoA-I, nor the bihelical apoA-I mimetic peptide L-37pA had any effect on PMN chemotaxis in response to fMLF, the prototypical ligand of FPR1 (23). CXCR2-active chemokines (i.e. CXCL1, CXCL2, and CXCL5), however, play a dominant role in directing PMN migration to inflammatory foci such as the lung in vivo (15). To test whether apolipoproteins suppress CXCR2-dependent PMN chemotaxis, we examined PMN chemotaxis up a CXCL2/MIP-2 gradient. Preincubation of murine bone marrow-derived PMNs with apoA-I for 1 h significantly suppressed chemotaxis in response to CXCL2 (Fig. 4A). Similarly, pretreatment of PMNs with L-4F suppressed PMN chemotaxis to CXCL2 compared with its scrambled peptide control (Fig. 4B). By contrast, COG1410 did not suppress chemotaxis compared with control (Fig. 4C). Suggesting a receptor level effect on chemotaxis, L-4F down-regulated the PMN surface display of CXCR2 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4D). Apoai+/+ and Apoai−/− mice, however, had equivalent numbers of circulating CXCR2+ PMNs (defined as Ly6G+ cells by flow cytometry) in peripheral blood (data not shown), indicating differences between acute ex vivo treatment with apoA-I mimetic and tonic in vivo exposure to apoA-I protein.

FIGURE 4.

Apolipoprotein mimetics suppress CXCR2-directed PMN chemotaxis. A-C, wild type murine bone marrow-derived PMNs were pretreated for 1 h with apoA-I (20 μg/ml) or media control (A), L-4F or sc-4F (10 μg/ml) (B), or COG1410 or control (CTL) peptide 264 (8.5 μg/ml) (C), and then assayed for chemotaxis (represented as % of total input PMNs) up a MIP-2 gradient. Data are mean ± S.E. and represent 2 or more independent experiments (**, p < 0.01). D, cell surface display of CXCR2 by murine PMNs was quantified by flow cytometric measurement of CXCR2 mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) after cell treatment (1 h) ex vivo with the indicated concentrations of sc-4F or L-4F. Data are mean ± S.E. and represent 2 independent experiments; **, p = 0.001. A representative flow cytometry histogram is shown at right.

ApoA-I Mimetic Peptides Induce PMN and Monocyte Chemotaxis

A common mechanism by which proteins/peptides may suppress chemotaxis is that of heterologous desensitization, whereby one chemotactic agent desensitizes responses to another via either receptor level or post-receptor effects. This is particularly well established for ligands of FPR1 and FPR2/ALX (24). Thus, fMLF desensitizes cells to CXCR2 ligands, in part through CXCR2 down-regulation (25, 26). Given these past findings, we next pursued the possibility that L-4F might itself possess chemoattractant activity. To access the greater numbers of cells required for mechanistic studies and at the same time to translate our studies into a human system, we pursued further studies using human peripheral blood PMNs and monocytes.

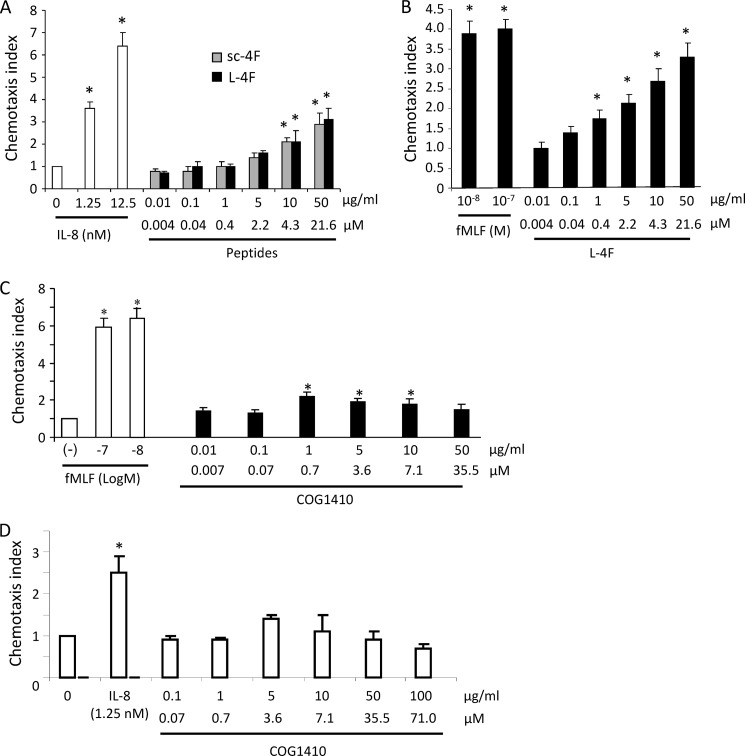

Human PMNs and monocytes indeed migrated up a gradient of L-4F in a dose-responsive fashion (Fig. 5), confirming that L-4F is a chemoattractant. L-4F at 50 μg/ml (21.6 μm) induced comparable chemotaxis to that of 10 ng/ml (∼1.25 nm) of IL-8 in the case of PMNs, and to 10 nm fMLF in the case of monocytes. Unexpectedly, however, sc-4F also induced chemotaxis of human PMNs, and comparably so to that of L-4F (Fig. 5A). Although this finding does not rule out a receptor-specific effect of L-4F on chemotaxis that is unrelated to the response to sc-4F, it does clearly indicate that the inhibition of CXCL2-induced chemotaxis observed with L-4F (compared with sc-4F) can be dissociated from the chemoattractant activity of L-4F. In further experiments, we found that L-4F does not induce a calcium flux in human PMNs or monocytes (data not shown), arguing against its receptor being a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) (16). Moreover, experiments using CXCR2-, CCR2-, FPR1-, and FPR2/ALX-transfected HEK293 cells in which we confirmed chemotactic responsiveness to cognate ligands (IL-8, CCL2, fMLF, and MMK-1 (27), respectively), showed that L-4F does not induce chemotaxis at a concentration up to 100 μg/ml (data not shown). Thus, whereas L-4F has been postulated to interact, if only indirectly, with non-chemotactic receptors (e.g. ATP binding cassette transporter (ABC) A1) (3), the identity of its chemotactic receptor remains uncertain. In contrast to L-4F, apoA-I protein was not chemotactic at concentrations up to 50 μg/ml (data not shown), thus identifying differences between the peptide mimetic and holoprotein.

FIGURE 5.

ApoA-I mimetic L-4F is a chemoattractant for human PMNs and monocytes. A, human PMNs purified from peripheral blood of normal, healthy donors were assayed for chemotaxis up a concentration range of gradients of IL-8 (control), L-4F, or sc-4F. Data are mean ± S.D. of chemotaxis index, which represents the fold-increase in the number of migrated cells counted in three high-power fields in response to chemoattractants over spontaneous cell migration to medium control (0)(*, p < 0.05 compared with medium control). B, chemotaxis of human peripheral blood monocytes in response to either fMLF or L-4F was assayed as in A. C and D, human peripheral blood monocytes (C) and neutrophils (D) were tested for chemotaxis up gradients of COG1410. fMLF and IL-8 were used as positive controls. *, p < 0.05 compared with medium control (− for monocytes; 0 for neutrophils).

Compared with L-4F, a gradient of COG1410 induced more modest migration of human monocytes (Fig. 5C), and without a clear dose-response, and did not induce significant chemotaxis of human PMNs (Fig. 5D). COG1410 also did not induce a calcium flux in monocytes (data not shown). Taken together, these data suggest that the class A amphipathic α-helical structure common to L-4F and COG1410 (but not sc-4F) is not a sufficient chemotactic motif, and that different apolipoprotein mimetic peptides possess complex, divergent relationships to chemotactic receptors.

Different ApoA-I Mimetic Peptides Elicit Calcium Flux and Chemotaxis through Divergent Receptors

Several apoA-I mimetic peptides have been designed in an effort to optimize lipid binding and other characteristics (28). In an aim to further explore structure-function (i.e. chemotaxis) relationships of apolipoprotein mimetics, we next examined L-37pA, a well studied 37-amino acid tandem helical analog of L-4F that incorporates Leu-Phe substitutions at residues 3 and 14 within two helices separated by a proline residue (i.e. [Leu3,14L-4F]-Pro-[Leu3,14L-4F]) (Table 1) (10). Past studies have indicated that L-37pA has increased lipid binding capacity but reduced specificity for the ABCA1 transporter in mobilizing cholesterol from cells compared with either apoA-I or other apoA-I mimetics (11). In parallel, we studied the D-stereoisomer of L-37pA (i.e. D-37pA) (10) as a control peptide.

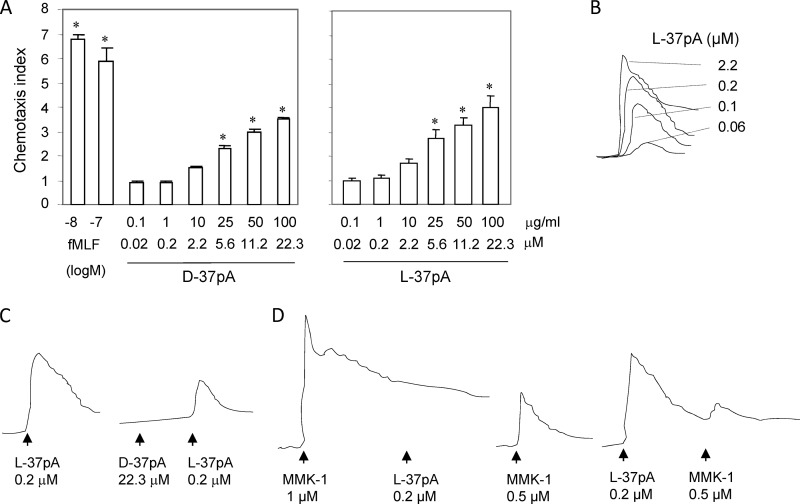

As shown in Fig. 6A, monocytes migrated up an L-37pA gradient in a dose-dependent fashion, with a chemotactic response detected at 10 μg/ml (2.2 μm). D-37pA displayed roughly equivalent chemotactic activity for monocytes. Consistent with its usage of a GPCR, L-37pA induced a dose-dependent calcium flux in monocytes, displaying a threshold of ∼0.06 μm, and an EC50 of ∼0.1 μm (Fig. 6B). Of note, D-37pA did not itself induce a calcium flux, but did attenuate the calcium flux induced by subsequent exposure to L-37pA (Fig. 6C), suggesting that D-37pA may perhaps competitively bind to the same receptor as L-37pA, but in a non-signaling manner.

FIGURE 6.

ApoA-I mimetic L-37pA induces chemotaxis and calcium flux by human monocytes and cross-desensitizes with a defined FPR2/ALX ligand. A, human monocytes were assayed, as described in the legend to Fig. 5, for chemotaxis to a concentration range of D-37pA, L-37pA, or fMLF (*, p < 0.05 compared with medium control (chemotaxis index set to 1)). B-D, calcium flux in Fura-2-loaded monocytes under different stimulation conditions was calculated as the ratio of fluorescence at 340 and 380 nm wavelengths using the FLWinLab program. B, calcium flux in response to a concentration range of L-37pA. C, reduction of L-37pA-induced calcium flux by pre-exposure of monocytes to D-37pA, which itself does not induce a calcium flux. D, cross-desensitization of L-37pA with MMK-1, a defined FPR2/ALX agonist. Pre-exposure of monocytes to MMK-1 and L-37pA reciprocally densensitizes calcium fluxes induced by the other.

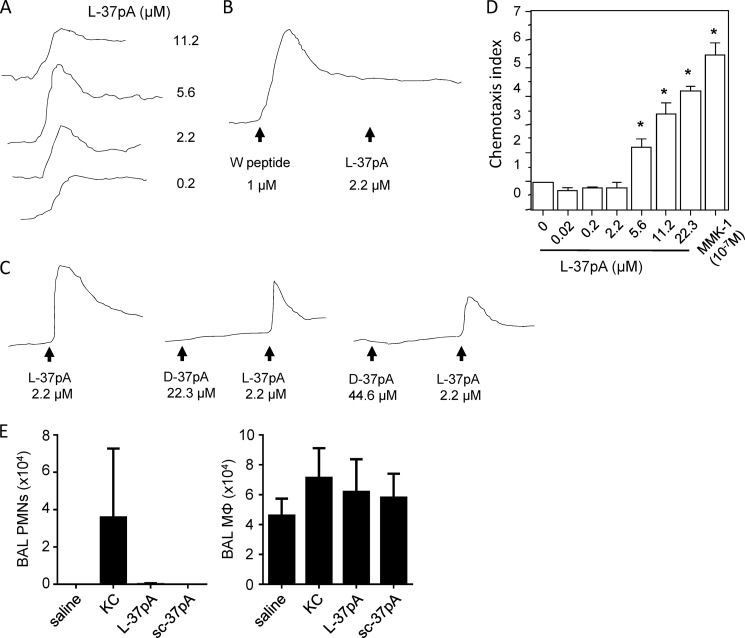

Among chemokine receptors, the FPR family seemed to us to be a strong candidate as a receptor family that might be responsive to L-37pA. Of the two FPR family members co-expressed in human PMNs and monocytes (FPR1 and FPR2/ALX), FPR2/ALX in particular is thought to be among the most promiscuous of chemotactic GPCRs described to date, being responsive to several ligands of varying structure and origin, including short peptides (29, 30). To test the notion that L-37pA uses FPR2/ALX, we used the defined FPR2/ALX agonist MMK-1 (27) and L-37pA in cross-desensitization experiments, a widely used method to infer shared usage of a receptor by two agonists (17, 31). In support of L-37pA indeed acting upon FPR2/ALX, MMK-1 and L-37pA reciprocally desensitized monocyte calcium fluxes to each other (Fig. 6D). Moreover, L-37pA induced a calcium flux in FPR2/ALX-transfected (but not parental or FPR1-transfected) HEK293 cells (Fig. 7A), and W peptide, another defined FPR2/ALX agonist (32), desensitized FPR2/ALX-HEK293 cells to L-37pA-induced calcium flux (Fig. 7B). Consistent with our findings in monocytes, D-37pA did not induce a calcium flux in FPR2/ALX-HEK293 cells even at a concentration as high as 200 μg/ml (44.6 μm), but did reduce responses to L-37pA in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 7C). L-37pA was confirmed to induce chemotaxis of FPR2/ALX-HEK293 cells in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 7D), whereas it did not do so in parental HEK293 cells. L-37pA was, however, considerably less potent than MMK-1, as 100 μg/ml (22.3 μm) L-37pA did not quite approach the chemotactic effect of 0.1 μm MMK-1. Consistent with its failure to induce a calcium flux, D-37pA did not induce chemotaxis of either FPR1- or FPR2/ALX-transfected HEK293 cells (data not shown), thus further confirming its usage of an alternate chemotactic receptor.

FIGURE 7.

ApoA-I mimetic L-37pA induces FPR2/ALX-dependent calcium flux and chemotaxis. A-C, calcium flux in FPR2/ALX-transfected HEK293 cells was assayed as described in the legend to Fig. 6. A, calcium flux was quantified in response to a concentration range of L-37pA. B, W peptide, a defined FPR2/ALX ligand desensitizes subsequent calcium flux in response to L-37pA. C, D-37pA does not induce a calcium flux, but does reduce subsequent L-37pA-induced calcium flux. D, chemotaxis by FPR2/ALX-HEK293 cells was quantified, as described in the legend to Fig. 6, up a concentration range gradient of L-37pA and MMK-1 (*, p < 0.05 compared with medium control (0)). E, C57BL/6 mice were instilled intratracheally with saline, 0.25 μg of KC, 100 μg of L-37pA, or 100 μg of scrambled L-37pA (sc-37pA) and bronchoalveolar lavage neutrophils (PMNs) and macrophages (MΦ) were counted 6 h later. Results are n = 5/condition and are representative of 2 independent experiments.

Given that L-37pA induces chemotaxis in vitro, we tested whether it also chemoattracts leukocytes in vivo. C57BL/6 mice were instilled intratracheally with 0.25 μg (∼0.03 nmol) of KC, 100 μg (43 nmol) of L-37pA, or 100 μg of scrambled L-37pA, and airway cells were counted 6 h later. Neither L-37pA nor scrambled L-37pA induced detectable influx of neutrophils or monocytes/macrophages into the airspace (Fig. 7E).

DISCUSSION

HDL, as well as the HDL-associated apolipoproteins apoE and apoA-I, have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant functions in addition to their well known capacity to mobilize cholesterol from macrophages and other cells in the vascular system. Borrowing on this, a variety of synthetic apoA-I and apoE mimetic peptides have been designed as potential therapeutics; among them, 4F has already been tested in high-risk cardiovascular patients (33). Apolipoprotein mimetic peptides have more recently also been shown to have anti-inflammatory activity in lung, brain, and other peripheral organs, suggesting a wide-ranging potential as human therapeutics. Some anti-inflammatory mechanisms have been defined for these peptides, including down-regulation of adhesion molecules, suppression of cytokine induction, and remodeling of HDL (34). Nonetheless, many questions remain about their biology and their efficacy against inflammation at peripheral sites, in particular mucosal surfaces, where there is a requirement for the complex trans-vascular and -epithelial passage of leukocytes during disease. Herein, we show that apolipoproteins and their mimetics regulate PMN influx into the LPS-exposed airspace, link this to effects upon CXCR2-dependent PMN migration, and provide evidence that apolipoprotein mimetics are themselves novel PMN and monocyte chemoattractants. Using 3 different apoA-I peptides (L-4F, L-37pA, and D-37pA) to explore structure-function relationships, we infer activity at several chemotactic receptors. Perhaps most notably, we specifically identify the GPCR FPR2/ALX as a chemotactic receptor for L-37pA, thus adding another ligand to the list of structurally divergent agonists for this multirecognition receptor, a list that includes serum amyloid A, lipoxin A4, amyloid-β, HIV-1 envelope peptides, and humanin, among others (29, 30).

FPR2/ALX (formerly called FPRL1 or LXA4R) is a 351-amino acid, 7-transmembrane GPCR that shares 69% of its amino acids with FPR1, the high-affinity receptor for the prototypical formylated peptide fMLF. FPR2/ALX and FPR1 display a similar tissue distribution, including hematapoietic (PMNs, monocytes, T cells, immature dendritic cells) and structural (epithelial cells, endothelial cells, hepatocytes) cells (24, 29). Itself a low affinity receptor for fMLF (Kd = 430 nm (35, 36)), FPR2/ALX has recently been shown to have a long list of peptide and non-peptide agonists and antagonists of varying affinity (24, 36). FPR2/ALX agonists have generally been shown to elicit chemotaxis, and in several, but not all cases, additional functions, including superoxide generation, cytokine induction, and apoptosis suppression (31, 37–39). The distinct downstream effects of different FPR2/ALX agonists may stem from non-overlapping binding sites on FPR2/ALX (31, 39). Several examples exist of FPR2/ALX agonists that desensitize cells to chemotaxis elicited through chemokine receptors (i.e. heterologous desensitization). For example, W peptide down-regulates CXCR2 (26) and F peptide and gp120 down-regulate CXCR4 (16). Consistent with our in vivo findings in the present report, small-molecule FPR2/ALX agonists that inhibit chemokine-directed PMN chemotaxis through cross-desensitization have recently been shown, upon systemic treatment of rodents, to attenuate PMN migration to sites of inflammation in vivo (40–42).

Given its EC50 of ∼112 nm for calcium flux in monocytes, L-37pA appears to be a medium-affinity ligand for FPR2/ALX, much less potent than MMK-1 (EC50 <2 nm in FPR2-HEK293 cells (43)), but considerably more potent than the HIV-1 peptides N36 (EC50 ∼ 2.5 μm (44)), F (EC50 ∼ 2.5 μm (16)), and V3 (EC50 ∼ 1.5 μm (45)). Several low-affinity chemokine-receptor interactions have previously been reported (e.g. growth-related oncogene, neutrophil-activating peptide 2, and epithelial cell-derived neutrophil-activating peptide 78 for CXCR1 (46)) and shown to be important in contributing to leukocyte recruitment to inflammatory foci in vivo (47). Nonetheless, it is important to note, especially given the modest potency of the peptides, that our ex vivo and in vivo findings are associative. The inhibition of neutrophil migration observed in peptide-treated mice may very possibly derive from additional or even different mechanisms from those observed ex vivo (e.g. through possible effects of the peptides upon leukocyte adhesion). Indeed, L-37pA injection did not induce neutrophil migration into the airspace, at least under the conditions tested. Although this may possibly reflect technical issues (e.g. protein binding in vivo), it clearly raises into question the status of apolipoprotein mimetics as chemotactic agents in vivo and also dissociates their chemotactic activity from their inhibitory action on chemokine-directed neutrophil migration. In the case of COG1410, we did not observe attenuation of MIP-2-directed neutrophil chemotaxis ex vivo. Moreover, our data indicate that apolipoprotein mimetic peptides and their native holoproteins have distinct biological activities. Thus, whereas our systems of apolipoprotein deficiency (i.e. gene-deleted mice) and excess (i.e. peptide treatment) did show some opposing responses (e.g. neutrophil recruitment into the chemokine-instilled airway), caution is warranted in extrapolating biological insights directly across the two systems.

Future studies are warranted to define the range of FPR2/ALX ligands beyond L-37pA that are antagonized by D-37pA. As it has recently been shown that endogenous FPR2/ALX ligands are produced in vivo and attract PMNs to inflammatory foci including lung (48), we speculate that therapeutic potential may exist for D-37pA as an anti-inflammatory FPR2/ALX antagonist. Moreover, it will be interesting to identify possible functional responses of tissue-resident, FPR2/ALX-expressing cells (e.g. epithelia) to L-37pA, as well as to profile possible additional inflammation- and infection-relevant functional responses elicited by L-37pA in PMNs. On this note, using a standard cytochrome c reduction assay, we were unable to detect superoxide generation by human PMNs exposed to L-37pA (at a concentration up to 20 μm) either in the absence or presence of prior LPS priming (data not shown). This suggests that L-37pA does not induce the full suite of functional responses that has been described for some FPR2/ALX ligands (24, 29).

We report that L-4F and COG1410 possess chemotactic activity, but provide evidence that their chemotactic receptors are not likely to be GPCRs. To what extent the chemotactic activity of L-4F (and L-37pA) relates to its known ability to extract cholesterol from cell membranes is uncertain. COG1410 (and its analogues) was designed to mimic the α-helical region of holo-apoE that binds to the low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR). The anti-inflammatory activity of this peptide reportedly correlates with its α-helical secondary structure (6), a feature that is enhanced by its content of amino isobutyric acid, a non-naturally occurring amino acid that enhances α-helical character (49). It remains unclear whether the reported anti-inflammatory properties of COG1410, in particular suppression of cytokine induction by leukocytes, are LDL receptor-dependent, although recent evidence argues against this (50). Future work will be required to define the chemotactic receptors for COG1410 and L-4F. Moreover, our findings do not exclude additional possible mechanisms by which apolipoproteins/mimetics may impact leukocyte trafficking to tissues, such as through affecting leukocyte adhesion.

In summary, we report that apoA-I and apoE and their mimetics regulate PMN migration to the airway, and we link this to novel and complex chemotactic properties of apolipoprotein mimetic peptides. We speculate that our findings offer an additional unifying mechanism for the efficacy of these peptides against inflammatory disorders at multiple, disparate tissue sites, and that, in a broader sense, they provide a novel and intriguing link between apolipoproteins and leukocyte biology.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ligon Perrow for animal colony management, Sandra Ward and Greg Travlos for peripheral leukocyte counting and typing, and Carl Bortner for help with flow cytometry.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Program NIEHS Grant Z01 ES102005.

- PMN

- neutrophil

- apo

- apolipoprotein

- fMLF

- formyl-Met-Leu-Phe

- FPR

- formyl peptide receptor

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- HDL

- high density lipoprotein

- Aib

- amino isobutyric acid

- MIP-2

- macrophage inflammatory protein-2.

REFERENCES

- 1. Murphy A. J., Woollard K. J. (2010) High-density lipoprotein. A potent inhibitor of inflammation. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 37, 710–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yvan-Charvet L., Wang N., Tall A. R. (2010) Role of HDL, ABCA1, and ABCG1 transporters in cholesterol efflux and immune responses. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 30, 139–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Navab M., Shechter I., Anantharamaiah G. M., Reddy S. T., Van Lenten B. J., Fogelman A. M. (2010) Structure and function of HDL mimetics. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 30, 164–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dai L., Datta G., Zhang Z., Gupta H., Patel R., Honavar J., Modi S., Wyss J. M., Palgunachari M., Anantharamaiah G. M., White C. R. (2010) The apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptide 4F prevents defects in vascular function in endotoxemic rats. J. Lipid Res. 51, 2695–2705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Getz G. S., Wool G. D., Reardon C. A. (2010) Biological properties of apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptides. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 12, 96–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Laskowitz D. T., Fillit H., Yeung N., Toku K., Vitek M. P. (2006) Apolipoprotein E-derived peptides reduce CNS inflammation. Implications for therapy of neurological disease. Acta Neurol. Scand Suppl. 185, 15–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yao X., Dai C., Fredriksson K., Dagur P. K., McCoy J. P., Qu X., Yu Z. X., Keeran K. J., Zywicke G. J., Amar M. J., Remaley A. T., Levine S. J. (2011) 5A, an apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptide, attenuates the induction of house dust mite-induced asthma. J. Immunol. 186, 576–583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang W., Xu H., Shi Y., Nandedkar S., Zhang H., Gao H., Feroah T., Weihrauch D., Schulte M. L., Jones D. W., Jarzembowski J., Sorci-Thomas M., Pritchard K. A., Jr. (2010) Genetic deletion of apolipoprotein A-I increases airway hyperresponsiveness, inflammation, and collagen deposition in the lung. J. Lipid Res. 51, 2560–2570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yao X., Fredriksson K., Yu Z. X., Xu X., Raghavachari N., Keeran K. J., Zywicke G. J., Kwak M., Amar M. J., Remaley A. T., Levine S. J. (2010) Apolipoprotein E negatively regulates house dust mite-induced asthma via a low-density lipoprotein receptor-mediated pathway. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 182, 1228–1238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bocharov A. V., Baranova I. N., Vishnyakova T. G., Remaley A. T., Csako G., Thomas F., Patterson A. P., Eggerman T. L. (2004) Targeting of scavenger receptor class B type I by synthetic amphipathic alpha-helical-containing peptides blocks lipopolysaccharide (LPS) uptake and LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine responses in THP-1 monocyte cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 36072–36082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Remaley A. T., Thomas F., Stonik J. A., Demosky S. J., Bark S. E., Neufeld E. B., Bocharov A. V., Vishnyakova T. G., Patterson A. P., Eggerman T. L., Santamarina-Fojo S., Brewer H. B. (2003) Synthetic amphipathic helical peptides promote lipid efflux from cells by an ABCA1-dependent and an ABCA1-independent pathway. J. Lipid Res. 44, 828–836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brewer H. B., Jr., Ronan R., Meng M., Bishop C. (1986) Isolation and characterization of apolipoproteins A-I, A-II, and A-IV. Methods Enzymol. 128, 223–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gao J., Wang H., Sheng H., Lynch J. R., Warner D. S., Durham L., Vitek M. P., Laskowitz D. T. (2006) A novel apoE-derived therapeutic reduces vasospasm and improves outcome in a murine model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit. Care 4, 25–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Laskowitz D. T., McKenna S. E., Song P., Wang H., Durham L., Yeung N., Christensen D., Vitek M. P. (2007) COG1410, a novel apolipoprotein E-based peptide, improves functional recovery in a murine model of traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 24, 1093–1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Smoak K., Madenspacher J., Jeyaseelan S., Williams B., Dixon D., Poch K. R., Nick J. A., Worthen G. S., Fessler M. B. (2008) Effects of liver X receptor agonist treatment on pulmonary inflammation and host defense. J. Immunol. 180, 3305–3312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Deng X., Ueda H., Su S. B., Gong W., Dunlop N. M., Gao J. L., Murphy P. M., Wang J. M. (1999) A synthetic peptide derived from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 down-regulates the expression and function of chemokine receptors CCR5 and CXCR4 in monocytes by activating the 7-transmembrane G-protein-coupled receptor FPRL1/LXA4R. Blood 94, 1165–1173 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Su S. B., Gong W., Gao J. L., Shen W., Murphy P. M., Oppenheim J. J., Wang J. M. (1999) A seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor, FPRL1, mediates the chemotactic activity of serum amyloid A for human phagocytic cells. J. Exp. Med. 189, 395–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yan Y. J., Li Y., Lou B., Wu M. P. (2006) Beneficial effects of ApoA-I on LPS-induced acute lung injury and endotoxemia in mice. Life Sci. 79, 210–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kim T. H., Lee Y. H., Kim K. H., Lee S. H., Cha J. Y., Shin E. K., Jung S., Jang A. S., Park S. W., Uh S. T., Kim Y. H., Park J. S., Sin H. G., Youm W., Koh E. S., Cho S. Y., Paik Y. K., Rhim T. Y., Park C. S. (2010) Role of lung apolipoprotein A-I in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effect on experimental lung injury and fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 182, 633–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lin C. T., Xu Y. F., Wu J. Y., Chan L. (1986) Immunoreactive apolipoprotein E is a widely distributed cellular protein. Immunohistochemical localization of apolipoprotein E in baboon tissues. J. Clin. Invest. 78, 947–958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Diederich W., Orsó E., Drobnik W., Schmitz G. (2001) Apolipoprotein AI and HDL3 inhibit spreading of primary human monocytes through a mechanism that involves cholesterol depletion and regulation of CDC42. Atherosclerosis 159, 313–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bursill C. A., Castro M. L., Beattie D. T., Nakhla S., van der Vorst E., Heather A. K., Barter P. J., Rye K. A. (2010) High-density lipoproteins suppress chemokines and chemokine receptors in vitro and in vivo. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 30, 1773–1778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Blackburn W. D., Jr., Dohlman J. G., Venkatachalapathi Y. V., Pillion D. J., Koopman W. J., Segrest J. P., Anantharamaiah G. M. (1991) Apolipoprotein A-I decreases neutrophil degranulation and superoxide production. J. Lipid Res. 32, 1911–1918 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Migeotte I., Communi D., Parmentier M. (2006) Formyl peptide receptors. A promiscuous subfamily of G protein-coupled receptors controlling immune responses. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 17, 501–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Le Y., Oppenheim J. J., Wang J. M. (2001) Pleiotropic roles of formyl peptide receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 12, 91–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang Z., Cherryholmes G., Chang F., Rose D. M., Schraufstatter I., Shively J. E. (2009) Evidence that cathelicidin peptide LL-37 may act as a functional ligand for CXCR2 on human neutrophils. Eur. J. Immunol. 39, 3181–3194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hu J. Y., Le Y., Gong W., Dunlop N. M., Gao J. L., Murphy P. M., Wang J. M. (2001) Synthetic peptide MMK-1 is a highly specific chemotactic agonist for leukocyte FPRL1. J. Leukoc. Biol. 70, 155–161 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Datta G., Chaddha M., Hama S., Navab M., Fogelman A. M., Garber D. W., Mishra V. K., Epand R. M., Epand R. F., Lund-Katz S., Phillips M. C., Segrest J. P., Anantharamaiah G. M. (2001) Effects of increasing hydrophobicity on the physical-chemical and biological properties of a class A amphipathic helical peptide. J. Lipid Res. 42, 1096–1104 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ye R. D., Boulay F., Wang J. M., Dahlgren C., Gerard C., Parmentier M., Serhan C. N., Murphy P. M. (2009) International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXIII. Nomenclature for the formyl peptide receptor (FPR) family. Pharmacol. Rev. 61, 119–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chiang N., Serhan C. N., Dahlén S. E., Drazen J. M., Hay D. W., Rovati G. E., Shimizu T., Yokomizo T., Brink C. (2006) The lipoxin receptor ALX. Potent ligand-specific and stereoselective actions in vivo. Pharmacol. Rev. 58, 463–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ying G., Iribarren P., Zhou Y., Gong W., Zhang N., Yu Z. X., Le Y., Cui Y., Wang J. M. (2004) Humanin, a newly identified neuroprotective factor, uses the G protein-coupled formylpeptide receptor-like-1 as a functional receptor. J. Immunol. 172, 7078–7085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Le Y., Gong W., Li B., Dunlop N. M., Shen W., Su S. B., Ye R. D., Wang J. M. (1999) Utilization of two seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptors, formyl peptide receptor-like 1 and formyl peptide receptor, by the synthetic hexapeptide WKYMVm for human phagocyte activation. J. Immunol. 163, 6777–6784 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bloedon L. T., Dunbar R., Duffy D., Pinell-Salles P., Norris R., DeGroot B. J., Movva R., Navab M., Fogelman A. M., Rader D. J. (2008) Safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of oral apoA-I mimetic peptide D-4F in high-risk cardiovascular patients. J. Lipid Res. 49, 1344–1352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tabet F., Remaley A. T., Segaliny A. I., Millet J., Yan L., Nakhla S., Barter P. J., Rye K. A., Lambert G. (2010) The 5A apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptide displays antiinflammatory and antioxidant properties in vivo and in vitro. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 30, 246–252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Murphy P. M., Ozçelik T., Kenney R. T., Tiffany H. L., McDermott D., Francke U. (1992) A structural homologue of the N-formyl peptide receptor. Characterization and chromosome mapping of a peptide chemoattractant receptor family. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 7637–7643 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ye R. D., Cavanagh S. L., Quehenberger O., Prossnitz E. R., Cochrane C. G. (1992) Isolation of a cDNA that encodes a novel granulocyte N-formyl peptide receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 184, 582–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lee H. Y., Kim S. D., Shim J. W., Lee S. Y., Lee H., Cho K. H., Yun J., Bae Y. S. (2008) Serum amyloid A induces CCL2 production via formyl peptide receptor-like 1-mediated signaling in human monocytes. J. Immunol. 181, 4332–4339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Filep J. G., El Kebir D. (2009) Neutrophil apoptosis. A target for enhancing the resolution of inflammation. J. Cell Biochem. 108, 1039–1046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bae Y. S., Yi H. J., Lee H. Y., Jo E. J., Kim J. I., Lee T. G., Ye R. D., Kwak J. Y., Ryu S. H. (2003) Differential activation of formyl peptide receptor-like 1 by peptide ligands. J. Immunol. 171, 6807–6813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bürli R. W., Xu H., Zou X., Muller K., Golden J., Frohn M., Adlam M., Plant M. H., Wong M., McElvain M., Regal K., Viswanadhan V. N., Tagari P., Hungate R. (2006) Potent hFPRL1 (ALXR) agonists as potential anti-inflammatory agents. Bioorg Med. Chem. Lett. 16, 3713–3718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sogawa Y., Ohyama T., Maeda H., Hirahara K. (2011) Inhibition of neutrophil migration in mice by mouse formyl peptide receptors 1 and 2 dual agonist. Indication of cross-desensitization in vivo. Immunology 132, 441–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sogawa Y., Ohyama T., Maeda H., Hirahara K. (2011) Formyl peptide receptor 1 and 2 dual agonist inhibits human neutrophil chemotaxis by the induction of chemoattractant receptor cross-desensitization. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 115, 63–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Klein C., Paul J. I., Sauvé K., Schmidt M. M., Arcangeli L., Ransom J., Trueheart J., Manfredi J. P., Broach J. R., Murphy A. J. (1998) Identification of surrogate agonists for the human FPRL-1 receptor by autocrine selection in yeast. Nat. Biotechnol. 16, 1334–1337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Le Y., Jiang S., Hu J., Gong W., Su S., Dunlop N. M., Shen W., Li B., Ming Wang J. (2000) N36, a synthetic N-terminal heptad repeat domain of the HIV-1 envelope protein gp41, is an activator of human phagocytes. Clin. Immunol. 96, 236–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shen W., Proost P., Li B., Gong W., Le Y., Sargeant R., Murphy P. M., Van Damme J., Wang J. M. (2000) Activation of the chemotactic peptide receptor FPRL1 in monocytes phosphorylates the chemokine receptor CCR5 and attenuates cell responses to selected chemokines. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 272, 276–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ahuja S. K., Murphy P. M. (1996) The CXC chemokines growth-regulated oncogene (GRO) α, GROβ, GROγ, neutrophil-activating peptide-2, and epithelial cell-derived neutrophil-activating peptide-78 are potent agonists for the type B, but not the type A, human interleukin-8 receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 20545–20550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Foxman E. F., Campbell J. J., Butcher E. C. (1997) Multistep navigation and the combinatorial control of leukocyte chemotaxis. J. Cell Biol. 139, 1349–1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chen K., Le Y., Liu Y., Gong W., Ying G., Huang J., Yoshimura T., Tessarollo L., Wang J. M. (2010) A critical role for the G protein-coupled receptor mFPR2 in airway inflammation and immune responses. J. Immunol. 184, 3331–3335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Marshall G. R., Hodgkin E. E., Langs D. A., Smith G. D., Zabrocki J., Leplawy M. T. (1990) Factors governing helical preference of peptides containing multiple α,α-dialkyl amino acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 487–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Christensen D. J., Ohkubo N., Oddo J., Van Kanegan M. J., Neil J., Li F., Colton C. A., Vitek M. P. (2011) Apolipoprotein E and peptide mimetics modulate inflammation by binding the SET protein and activating protein phosphatase 2A. J. Immunol. 186, 2535–2542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]