Abstract

Many assays are used in animal model systems to measure specific human disease-related behaviors. The use of both adult and larval zebrafish as a behavioral model is gaining popularity. As this work progresses and potentially translates into new treatments, we must do our best to improve the sensitivity of these assays by reducing confounding factors. Scientists who use the mouse model system have demonstrated that sex and age can influence a number of behaviors. As a community, they have moved to report the age and sex of all animals used in their studies. Zebrafish work does not yet carry the same mandate. In this study, we evaluated sex and age differences in locomotion behavior. We found that age was a significant factor in locomotion, as was sex within a given age group. In short, as zebrafish age, they appear to show less base level locomotion. With regard to sex, younger (10 months) zebrafish showed more locomotion in males, while older zebrafish (22 months) showed more movement in females. These findings have led us to suggest that those using the zebrafish for behavioral studies control for age and sex within their experimental design and report these descriptors in their methods.

Introduction

Human behaviors associated with disease states such as psychiatric disorders, addiction, and stress have many interrelated environmental and genetic causes. The study of these disorders is technically challenging. In the use of model organisms, many behavioral assays have been developed to measure specific disease-related behaviors. The zebrafish (Danio rerio) is gaining popularity as an animal model for behavioral research, and protocols have been developed to measure aggression, anxiety, locomotion, learning and memory, reward, sleep, and social preference for the purpose of better understanding human disease.1 The zebrafish has been shown to be a viable model for the study of complex behaviors and addiction.2–5 These behavioral assays have been used in hopes of better defining and/or developing new treatments for the disorders being modeled in each study. In the design of a behavioral assay, the control of underlying variability in the individuals used in the study is important as these differences may confound or mask the measurement of a true signal.

Some studies have noted variability among zebrafish relating to a variety of behavioral tests that can be attributed to genetics or phenotypic characteristics.6–9 Magguran et al. demonstrated that the mating tank itself used in behavioral studies can lead to sex-specific behaviors.10 In experiments which include the interactions of multiple zebrafish, sex and color11,12 and age13,14 have been shown to be determinants of behaviors, including interactions between fish and locomotion. However, more is necessary to understand the behavior of individual zebrafish.

The initial hypothesis of this work is that differences in sex and age of adult zebrafish may elicit significant differences in locomotion-based behavior of individual zebrafish measured using traditional assays. Understanding and defining any such contribution would be helpful in experimental protocol designs for zebrafish.

Materials and Methods

Zebrafish

All fish for the experiments were maintained by the Mayo Clinic Zebrafish Core Facility at 28.5°C and a 14:10 light:dark cycle.

Sex

15 male and 15 female zebrafish were individually placed into a mating tank with four equal size quadrants. Each fish was allowed to acclimate for 5 min before the test was started. One-minute intervals were used to monitor zebrafish locomotion. All measurements were done in real-time. Each time a zebrafish crossed a quadrant indicated one movement. Each fish was tested independently five times. Methodology was verified for accuracy by mentor partner.

Age

Age groups of zebrafish included 10 months, 22 months, and 32 months. The sex of fish used in the “Age Only” experiments was allowed to vary. Each age group was tested individually using 10 fish per group. Each individual fish was allowed to acclimate for 5 minutes before the test was started. One-minute intervals were used to monitor zebrafish locomotion. Each time a zebrafish crossed a quadrant indicated one movement. Each fish was tested independently five times.

Sex and age

Age groups from the previous experiments were used for an additional experiment in which sex was also controlled as a variable. Five male and five female zebrafish were used for each age group. Testing proceeded as described above.

Statistics

Averages, standard error, and graphing were performed using Microsoft Excel 2008. Student's t-tests for statistical significance were performed using the free online t-test calculator at http://studentsttest.com. P values in this work were calculated using the 2-tailed t-test. Analysis of variance for the overall effect was performed using St. John's University/College of St. Benedict Physics department's free online tool (http://www.physics.csbsju.edu/stats/anova.html) for ANOVA. Additionally, a Bonferroni correction was used to determine the threshold for statistical significance.

Results

Sex

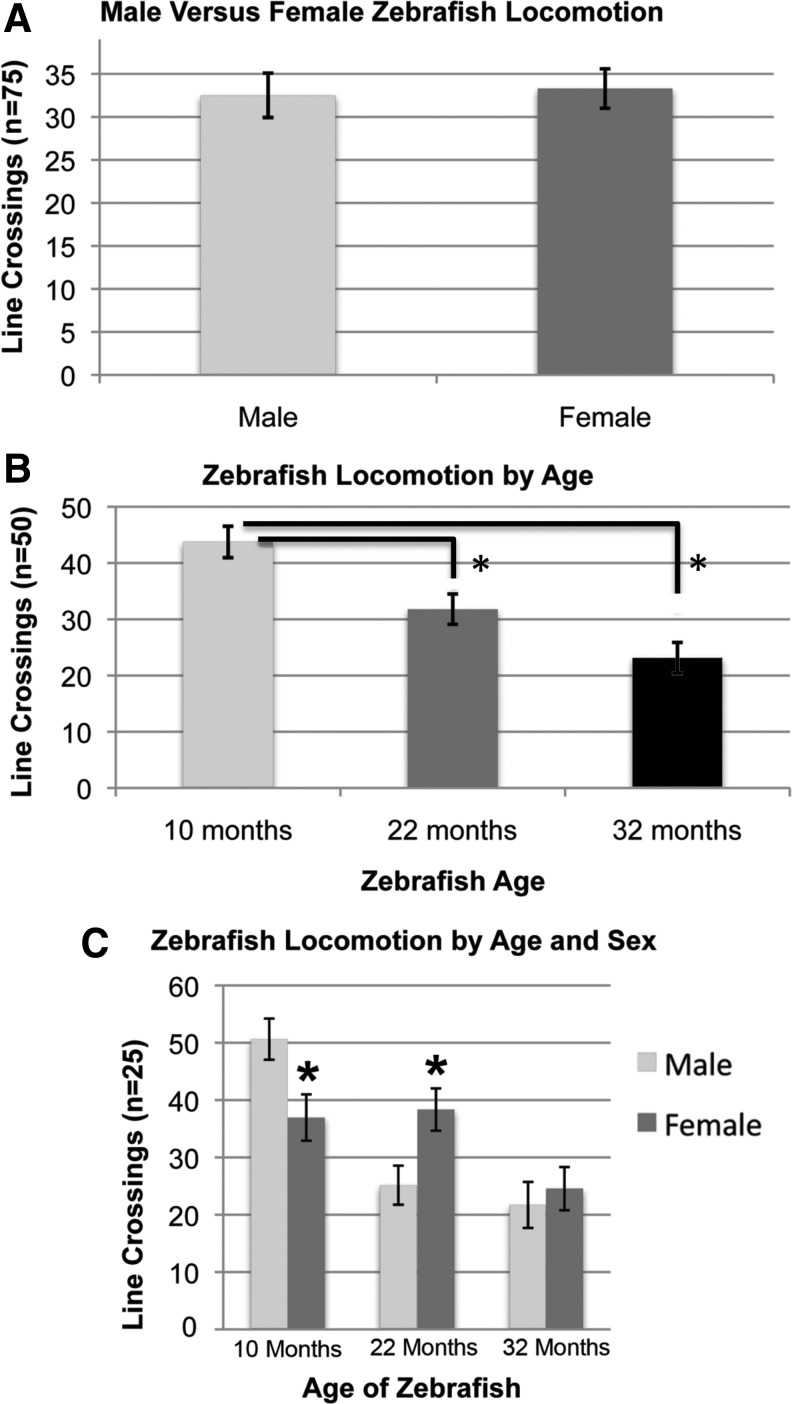

The trial to compare male and female locomotion included 15 male and 15 female zebrafish ranging in age from 10 to 32 months. The data include five 1-minute trials for each of the fish. When age was not controlled within the experiment, male fish and female fish did not differ significantly in their baseline movement between quadrants (p=0.82, n=75 trials) (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

Activity of adult zebrafish independently and coordinately assessed by sex and age. Locomotion of adult zebrafish was described by the number of times a fish crosses a predetermined boundary in 1 minute. (A) This behavior does not appear to be significantly affected by the sex of zebrafish participants (p=0.82). (B) However, the age of zebrafish participants does achieve statistical significance as a factor in the same assay for two of the comparisons. Differences between 10 and 22 months, p=0.003; between 10 and 32 months, p=9.6×e−7, 22 and 32 months p=0.035. Bonferroni correction based on three groups within the comparison and a 95% confidence interval, therefore show the first two comparisons to achieve significance (p<0.017). The latter comparison (22 vs. 32 months) does not. Analysis of variance for the overall effect is shown in Table 1. (C) At 10 and 22 months of age, zebrafish differ significantly by sex in their baseline locomotion (p=0.01 for both) at 32 months of age, the difference does not reach significance (p=0.6). Bars represent standard error.

Age

The trial to compare locomotion by age included 10 zebrafish at each of 3 ages (10, 22, and 32 months) (Fig. 1B). The data include five 1-minute trials for each of the fish. A decrease in motion was shown with increasing age of the zebrafish. In 10-month-old fish, an average of 43 line crossings (between quadrants) was documented. The 32-month-old fish showed nearly a 50% reduction to 23 line crossings on average. With sex of the fish not controlled, the fish of differing ages did show statistically significant differences in their total movement (average number of line crossings) using a Student's t-test, n=50 trials for each group. Differences between 10 and 22 months, p=0.003; between 10 and 32 months, p=9.6×e−7, 22 and 32 months p=0.035. Bonferroni correction based on 3 groups within the comparison and a 95% confidence interval, therefore show the first two comparisons to achieve significance (p<0.017). The latter comparison (22 vs. 32 months) does not. Analysis of variance for the overall effect revealed that as an overall effect, locomotion varies significantly by age of zebrafish (p<0.0001). The analysis of variance results are shared in Table 1.

Table 1.

ANOVA for Locomotion by Age

| Source of variation | Sum of squares | d.f. | Mean squares | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between | 1.0768 E+04 | 2 | 5384 | 14.26 |

| Error | 5.5495 E+04 | 147 | 377.5 | |

| Total | 6.6264 E+04 | 149 |

The probability of this result, assuming the null hypothesis, is less than 0.0001.

Sex and age

Finally, we compared the locomotion of each sex within each age group (Fig. 1C). The data include five 1-minute trials for each of 5 fish, n=25 trials for each combination. Within the 10- and 22-month ages, differences in locomotion between males and females reached statistical significance (p for both=0.01). The differences in locomotion between males and females at 32 months was not statistically significant (p=0.6). The reduction in overall locomotion brought on by age (as described in Fig. 1B) appears to reduce total locomotion to a level that would require many more fish to reveal any potential differences in locomotion by sex.

Discussion

In this study, a simple locomotion assay was used to determine baseline differences in behavior potentially affected by the sex or age of our zebrafish. Age of adult zebrafish was shown to be a significant factor in differences between baseline locomotion. Sex of the zebrafish was initially shown to be insignificant. However, within a single age cohort of adult zebrafish, sex was a significant factor in fish of 10 months and 22 months of age.

Recent behavioral work with zebrafish show that size and color may be important determinants of locomotion and behavior.15 Within this experiment, size was not measured, but there were not visually significant differences within a given age group. Wild-type coloration was also used for all experiments.

The switch in Figure 1C from higher movement in males at 10 months to higher movement in females at 22 months also drives further questions with regard to the priority of behaviors at any given age (i.e., food, safety, mate selection, etc.).10 It will be interesting to follow up with fish prior to sexual maturity.

Studies in mice have similarly shown a significant influence by sex in behavioral assays. Duvoisin et al. demonstrated age-related differences within anxiety behavior assays on mice.16 An et al. further demonstrated differences in anxiety and baseline activity of mice when compared by sex.17 Others have indicated differences in mouse behaviors by sex as it relates to depression and food reward response.16,18–21 Following these findings, it has been recommended that scientists working with mice should specify the sex and age of the animals used in their studies. Many of the assays for mouse behavior tend to be more complex than plotted locomotion, but the data contained in this manuscript strongly suggest that those vested in behavioral assays using zebrafish should carefully analyze differences that may be present within their test groups. It also seems reasonable to suggest that publications on behavior using zebrafish should follow the advice of mouse behaviorists and report the age and sex of their animals.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge: 1. Funding for the InSciEd Out partnership through the Center for Translational Science Activities Program Grant (NIH) at Mayo Clinic (UL1RR024150); 2. Stephen C. Ekker for the use of laboratory space and supplies; 3. Funding for student laboratory facilities through Lowe's grant (James Kulzer, Lincoln K–8 Choice School), and 4. Linnea Archer and her Language Arts class for active revision and proofing of manuscript drafts and revisions.

Author Biographies

Catie Philpott is now an 8th grade student at Lincoln K–8 Choice School in Rochester, MN. Corey Dornack is her science teacher. Margot Cousin is a graduate student with the Center for Translational Science at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Norton W. Bally-Cuif L. Adult zebrafish as a model organism for behavioural genetics. BMC Neurosci. 2010;11:90. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-11-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark KJ. Balciunas D. Pogoda HM. Ding Y. Westcot SE. Bedell VM, et al. In vivo protein trapping produces a functional expression codex of the vertebrate proteome. Nat Methods. 2011;8:506–515. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klee EW. Schneider H. Clark KJ. Cousin MA. Ebbert JO. Hooten WM, et al. Zebrafish: A model for the study of addiction genetics. Hum Genet. 2012;131:977–1008. doi: 10.1007/s00439-011-1128-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathur P. Guo Su. Use of zebrafish as a model to understand mechanisms of addiction and complex neurobehavioral phenotypes. Neurobiol Dis. 2010:40. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart A. Wong K. Cachat J. Gaikwad S. Kyzar E. Wu N, et al. Zebrafish models to study drug abuse-related phenotypes. Rev Neurosci. 2011;22:95–105. doi: 10.1515/RNS.2011.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bang PI. Yelick PC. Malicki JJ. Sewell WF. High-throughput behavioral screening method for detecting auditory response defects in zebrafish. J Neurosci Methods. 2002;118:177–187. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00118-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egan RJ. Bergner CL. Hart PC. Cachat JM. Canavello PR. Elegante MF, et al. Understanding behavioral and physiological phenotypes of stress and anxiety in zebrafish. Behav Brain Res. 2009;205:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lopez Patino MA. Yu L. Yamamoto BK. Zhdanova IV. Gender differences in zebrafish responses to cocaine withdrawal. Physiol Behav. 2008;95:36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ninkovic J. Bally-Cuif L. The zebrafish as a model system for assessing the reinforcing properties of drugs of abuse. Methods. 2006;39:262–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magurran AE. Garcia CM. Sex differences in behaviour as an indirect consequence of mating system. J Fish Biol. 2000:57. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engeszer RE. Wang G. Ryan MJ. Parichy DM. Sex-specific perceptual spaces for a vertebrate basal social aggregative behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:929–933. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708778105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snekser JL. Ruhl N. Bauer K. McRobert KB. The influence of sex and phenotype on shoaling decisions in zebrafish. Intl J Comp Psychol. 2010:23. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engeszer RE. Ryan MJ. Parichy DM. Learned social preference in zebrafish. Curr Biol. 2004;14:881–884. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moretz JA. Martins EP. Robison BD. The effects of early and adult social environment on zebrafish (Danio rerio) behavior. Environ Biol Fishes. 2007:80. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abaid N. Spinello C. Laut J. Porfiri M. Zebrafish (Danio rerio) responds to images animated by mathematical models of animal grouping. Behav Brain Res. 2012;232:406–410. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duvoisin RM. Villasana L. Pfankuch T. Raber J. Sex-dependent cognitive phenotype of mice lacking mGluR8. Behav Brain Res. 2010;209:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.An XL. Zou JX. Wu RY. Yang Y. Tai FD. Zeng SY, et al. Strain and sex differences in anxiety-like and social behaviors in C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice. Exp Anim. 2011;60:111–123. doi: 10.1538/expanim.60.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willingale-Theune J. Manaia A. Gebhardt P. De Lorenzi R. Haury M. Science education. Introducing modern science into schools. Science. 2009;325:1077–1078. doi: 10.1126/science.1171989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aoki M. Shimozuru M. Kikusui T. Takeuchi Y. Mori Y. Sex differences in behavioral and corticosterone responses to mild stressors in ICR mice are altered by ovariectomy in peripubertal period. Zoolog Sci. 2010;27:783–789. doi: 10.2108/zsj.27.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D'Andrea I. Gracci F. Alleva E. Branchi I. Early social enrichment provided by communal nest increases resilience to depression-like behavior more in female than in male mice. Behav Brain Res. 2010;215:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayward MD. Low MJ. The contribution of endogenous opioids to food reward is dependent on sex and background strain. Neuroscience. 2007;144:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]