Abstract

Purpose of review

To describe community engaged research (CEnR) and how it may improve the quality of a research study while addressing ethical concerns that communities may have with mental health and substance abuse research. This article includes a review of the literature as well as recommendations from an expert panel convened with funding from the US National Institute of Mental Health.

Recent findings

CEnR represents a broad spectrum of practices including representation on institutional ethics committees, attitude research with individuals from the study population, engaging community advisory boards, forming research partnerships with community organizations, and including community members as co-investigators.

Summary

CEnR poses some challenges; for example, it requires funding and training for researchers and community members. However, it offers many benefits to researchers and communities and some form of CEnR is appropriate and feasible in nearly every study involving human participants.

Keywords: research ethics, mental health, substance abuse, community engagement

Introduction

Research has the potential to yield tremendous benefits, but also to inflict significant harms. Consider the example of genetic research on the relationship between schizophrenia and substance abuse. Such research may be undertaken with the legitimate goals of better understanding pathophysiology and comorbidity, seeking new modes of treatment, identifying causative environmental factors, and identifying high-risk individuals who might benefit from preventative interventions.[1] However, such research also generates concerns such as possible insurance or employment discrimination if confidentiality is breached; concerns about negative psychological consequences of learning of a genetic risk; and questions regarding the appropriateness of sharing information pertinent to biological relatives.[2–6][5]** Complicating the resolution of these ethical issues, the field of psychiatric genetics is “haunted by memories of the eugenics movement of the early 1900’s, which targeted psychiatric patients and others considered ‘genetically inferior’ for forced sterilization and death.”[2, p.322] When abuse by researchers occurs in a community, mistrust may occur and people may be less willing to participate in research or even to seek help from the health care community possibly exacerbating health disparities.[7]

While we may tend to think of individuals as those who are harmed or benefited by research endeavors, communities may feel that they too are directly affected for better or for worse when researchers study their members. In particular, they may be highly susceptible to stigmatization.[8]* For example, the term “Scarlet genes” has been coined to refer to the stigmatization of groups when popular media report on genetic predispositions to alcoholism or drug abuse within minority populations.[9]

In this paper, we review what is community-engaged research (CEnR), how CEnR may improve our ability to address such ethical and social issues, and how CEnR may improve the quality of science. This article builds upon a National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)-funded scientific meeting held in St. Louis in June 2009 that reviewed the literature and recent studies at the intersection of research ethics and CEnR in mental health research. The authors served as panelists and include ethicists, mental health researchers, and community representatives, all of whom have played some role in community-engaged research in the areas of mental health or drug addiction research.

The panel strongly endorses the idea that CEnR is an essential and beneficial component of human research; however, CEnR is not easy. To that point, we have added “caveat” sections to raise awareness of some of the more significant challenges that arise in CEnR. Table 1 uses the example of genetic research on comorbid schizophrenia and substance abuse to illustrate the application of concepts found throughout the paper.

Table 1.

Illustrations of Key Concepts in Genetic Research

| Paper Section | Illustration |

|---|---|

| What is Community Engagement in Research? | Dr. Spencer is studying the genetic component to schizophrenia and whether its expression is related to substance use. As she begins designing her study, she consults some recently published articles on participant attitudes toward and knowledge of genetic screening [10–12], and discovers some concerns she had not considered, including the fact that most participants exaggerate the genetic component and heritability of major mental disorders. She establishes a community advisory board consisting of a few patients, a few family members, and the director of a local peer support group that serves mental health consumers. They will provide input on the study design, including the protections offered to participants. Moreover, in an attempt to build trust with the community, she employs an individual with schizophrenia to serve as a recruiter, who will also administer some surveys to peers. |

| Why Is Community Engagement Important? | Given the results of her literature review, Dr. Spencer decided to include a brief educational intervention during the enrollment process of her study. Many participants expressed surprise at the facts shared and some expressed gratitude for the information. Her advisory committee recommended that she hire a mental health consumer to assist with recruitment at the local peer-support center. After interviewing several candidates, she hired Mr. Jones, who was provided with human subjects protection training that was tailored to community members and focused on confidentiality protection. Mr. Jones helped Dr. Spencer to meet her enrollment goals a month earlier than planned after he convinced her to increase the payment for participant time by $10 per visit. He told her participants at his center view payments as a sign of respect and being valued, not as manipulation. Dr. Spencer was also surprised to learn through Mr. Jones that most participants wanted their data to be confidential but identifiable so they could be contacted in the future if the research yielded any information that could be useful to improving their own health. She could not accommodate this request in the current study, but decided to pursue this possibility in future research. |

| What are Characteristics of Successful Community Engagement? | Dr. Spencer’s advisory committee encouraged her to spend some “observership time” with Mr. Jones at the peer-support center and to conduct a focus group with regulars to ensure that she was taking cues from the larger group, and not just one member (Mr. Jones). They also encouraged her to work harder to retain participants in her study; she found that many participants missed meetings, particularly if they were actively using drugs. The advisory committee shared with her strategies for finding participants. After obtaining IRB approval for a protocol modification, Dr. Spencer was able to implement new contact procedures with participants, and her retention rate increased 25%. Additionally, Dr. Spencer began holding her quarterly community advisory board (CAB) meetings in different locations affiliated with members to indicate that she was concerned about their convenience and that she viewed them as team members. These various acts made it easier for participants to accept that she had their best interests in mind, even though the study would have no immediate therapeutic value for them. During the exit interviews, she also asked participants for permission to contact them for future studies. |

What Is Community Engaged Research (CEnR)?

CEnR is research that provides communities with a voice and role in the research process beyond providing access to research participants.[13–15] Clearly, this can be done to greater or lesser degrees. On the one hand, the forms of engagement may range from studying the views of community members regarding research protocols[16, 17] to incorporating community members as co-investigators.[14, 17–19] [17*]

Table 2 provides a description of nine forms of engaging community members. Each of the approaches listed goes beyond international requirements that Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) or Institutional Ethics Committees (IECs) include at least one member who is a non-scientist, unaffiliated with the institution[20, 21]. The various forms of CEnR provide ways of ensuring that a key stakeholder group is represented in the research enterprise as more than just a subject pool. In determining the degree to which communities are involved, key questions include:

Table 2.

Defining Forms of Engaging Communities in Research

| Approach with Illustrative References | Description |

|---|---|

| IRB/IEC membership [21] | An IRB/IEC might include an individual with a mental disorder, a family member, or an employee of a service agency. |

| IRB/IEC consultants | An IRB/IEC might invite an individual with a mental health disorder or a family member to serve as a consultant on all relevant protocols |

| Literature review of studies on participant attitudes and values [22] | A literature review is a low-cost option to understand the attitudes and concerns of participant populations, though published concerns may not be local concerns |

| Original research on participant attitudes and values [23–44] [30*, 40*, 44*] | Surveys, interviews, and focus groups can provide community members with the opportunity to express values, concerns, and knowledge. This approach may ensure that more than 1 individual’s views are represented |

| Community Advisory Boards [45] | Advisors may meet regularly with the research team to shape the study’s aims and design, the interpretation of results, and the dissemination of findings |

| Community Review Boards [46] | Community review boards may serve all of the roles of an advisory board, but additionally hold some decision-making authority—e.g., they could reject key aspects of a protocol—and may serve as gatekeepers |

| Clinical Trial Networks (CTN)— Institution/Agency Partnership | CTNs require collaboration between research institutions and community agencies. The community agency receives a portion of the research budget and serves as a primary recruiting and research site. Agency normally provides a co-investigator |

| Hiring community members as part of research team (e.g., interviewers or recruiters) [31, 45] | In participatory research, boundaries between subject and researcher communities may break down. A community member may be trained to serve as part of the research team, e.g., as a recruiter or interviewer |

| Community-conducted research [13, 45, 47] | Communities may decide to initiate a research project that they have conceived. Whether in partnership with seasoned researchers or not, communities may obtain the funding and design and implement studies |

How many individuals from the community are provided with a voice (e.g., one representative, a small group of gatekeepers, or a random sample)?

Do community members have authority to advise on the research protocol or to make key decisions regarding the research protocol?

Are community members elevated to the level of co-investigators? Do they share resources and play an investigative role in the conduct research? Do they participate in data interpretation and dissemination?

Community engagement in mental health research may involve interaction with individuals from any of the following groups: people with mental health disorders; people who are recovering; family members or caregivers; people at risk; clinicians, health care providers, service agencies, and insurers; government or industry funding representatives; and advocates. CEnR also involves members of communities who are affected by mental disorders, including employers, educators, prisoners, students; and minority members within any of these groups. CEnR may vary radically depending on whether, for example, mental health consumers are approached by researchers or rather they initiate a research study themselves, with or without the collaboration of an academic center.[46]

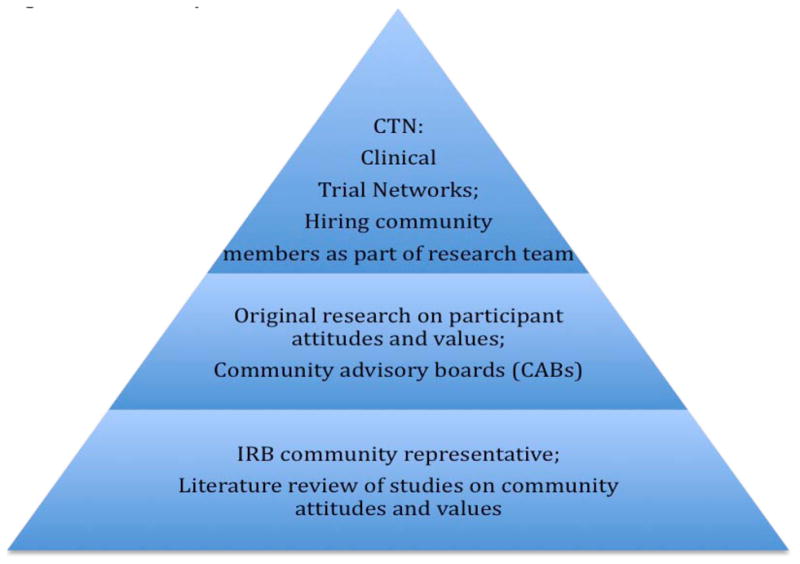

Different kinds and degrees of engagement may depend on how well certain values are embraced, how educated the researchers are regarding community engagement (techniques and benefits), time and financial resources, but also on the type of science (e.g., how much “scientific flexibility” they have) and the funding source, which may mandate CEnR or make it more difficult. Figure 1 provides a hierarchy of forms of CEnR with the baseline representing forms that are minimally burdensome and should be integrated into most human subjects research.

Figure 1.

A Hierarchy of Common Forms of CEnR

Caveats

For a group to constitute a community it must possess structure and leadership. In some cases a clear community exists prior to a research study; in other cases, researchers must collaborate with group members to establish a community structure.[49]** The boundaries of communities are not always well defined and communities may range from fairly homogenous to heterogeneous. Not all community members may wish to engage with researchers, and resources may limit the number of community members who can be engaged. The interests of the larger community may not always be congruent with the best interests or research goals of vulnerable groups within the community who will be recruited to participate in the research.[50] Thus, one never fully engages a community. Rather, community engagement is an ideal that may be more or less embodied by a study.

Why Is Community Engagement Important?

Researchers inevitably affect the communities they study and frequently leave a lasting impression—positive or negative. So-called “helicopter” projects, in which researchers fly in and quickly fly out with data, may leave the impression that communities are simply used rather than valued. Research that does not address the knowledge or health priorities of communities may contribute to research fatigue and an unwillingness to participate in research.[51, 52]

Engaging communities in appropriate ways is a form of showing respect for community members as persons. It provides a voice to individuals who are often disenfranchised.[19]* The American Psychological Association has asserted that community engagement is a requirement of any ethical research with minority communities.[53]

CEnR may also provide significant benefits to community members. Our researcher panelists believe that CEnR improves T3 or curbside translation of the results of health research. To the extent that decreasing health disparities is a health priority,[54] we should increase CEnR efforts toward cultural competence, the recruitment of minorities, and the dissemination of health information among minority communities. CEnR may also provide significant peripheral benefits to community members. For example, mental health service users have reported that participatory research offered them opportunities to gain knowledge and to share their unique perspectives increased self-esteem provided an opportunity for employment, and gave them a chance to give back to society and help others.[46]

CEnR may also improve the quality of science insofar as it may assist researchers in recruitment and retention.[49, 55, 56] The Framingham heart study would not have been the success that it was without intense engagement of the local community, including efforts to adapt the study in response to community concerns.[57] CEnR may additionally contribute to the recruitment of participants who are genuinely representative of the larger community. Given that 6.7% of the population suffers from depression[58] and 3.8% from substance abuse disorders at any given time[58] (with a life-long prevalence of 16.2%[59] and 14.6%[60] respectively) a study that wishes to have a truly representative sample should refrain from excluding individuals with such diagnoses; in fact, extra efforts should be made to include them[61]. CEnR methods have proven successful in recruiting marginalized populations into traditional clinical trials[62].

Moreover, community members may bring novel perspectives to questions of research design and recruitment; they may raise concerns or suggest useful strategies that may be unfamiliar to researchers.[46] Indeed, in early HIV trials CEnR was not only essential to obtaining the cooperation of the participant community, but some community members suggested improvements to the statistical analysis of the data.[63] In other cases, the scientific expertise may be largely qualitative. For example, while researchers often focus on “objective” outcomes of studies, mental health consumers may encourage a focus on subjective outcomes such as a sense of well-being and empowerment or of sadness and hopelessness.

CEnR may also serve to foster trust in science and to improve institutional public relations. While trust and trustworthiness are to be valued for their own sake, they are also prerequisites to any successful research enterprise.[46]

Further, compliance with international policies requires at least some degree of CEnR. For example, 45CFR46 (the US “common rule”) and European guidelines for good clinical practice require IRBs and IECs to have at least 1 member who is a non-scientist and unaffiliated with the institution.[21] NIH requires all Clinical and Translational Science Award programs (CTSAs) to have a community engagement program. Finally, in certain kinds of research, such as research in emergency medicine when informed consent cannot be obtained (e.g., from unconscious patients), U.S. regulations require investigators to consult with communities[64].

Caveats

As Emanuel et al[65] note, to be ethical, research must be scientifically valid.[66] Invalid research benefits no one and wastes resources. CEnR must be conducted in ways that do not compromise the quality of science. While CEnR can improve recruitment, retention, and the quality of participation, it can also compromise the quality of science if done poorly.[67]

What are Characteristics of Successful Community Engagement?

The quality of a CEnR process depends in part upon the traits that the researchers and community members bring to the encounter. Table 3 describes some of the traits that panelists considered ideal. While the panel first attempted to identify separately the ideal traits of researchers and community members, it became apparent that the ideal traits are shared, although the specific kinds of expertise that they provide will differ.

Table 3.

Ideal Traits of Engaged Researchers and Community Members

| Researchers and Community Members Should … |

| - Listen and learn |

| - Ask questions |

| - Educate and share their expertise (e.g., about science or community concerns and priorities) |

| - Be flexible and creative |

| - Demonstrate empathy, courtesy, cultural sensitivity |

| - Be diverse in their backgrounds and thinking |

While not all forms of CEnR involve including community members as members of the research team (co-investigators), this would be considered the most robust and also most complex form of CEnR. A group of mental health consumer-researchers have identified a list of requirements for appropriate involvement of consumers on the research team: payment for work; equal treatment; involvement in all stages of research; acknowledgement of power differentials; regular feedback on their work; safe work environment, including emotional support; and sufficient training.[68]

Successful CEnR requires the ability to translate the community’s values and research priorities to the audience of funding agencies and grant reviewers. This can be challenging when researchers and community members have different priorities and expectations.[69]** In these cases, mediation skills (listening, paraphrasing, seeking compromises, etc.) can be beneficial.[70]

The success of CEnR in research should be measured in terms of all the potential benefits of CEnR identified above, including enhancing relationships with community members and facilitating high quality research.

Caveats

Successful CEnR takes time to develop. Initially, it may be difficult to recruit diverse community members to engage researchers; failures to do so may inappropriately empower one or a few individuals to set the agenda for a community. It may take time for researchers to adapt their frame of mind to appreciate the different values and the different kind of expertise that community members may bring to a project, just as it may take time for community members to understand the rules of science and research funding, which set limits to the accommodations that can be made within a research protocol. Further, when community members are integrated into the research team, they may ironically lose their ability to represent accurately the views of the community; community advisory boards may retain a significant role even in robust forms of CEnR.

What is Required to Foster Community Engaged Research?

Among the many resources needed to sustain CEnR, we believe two deserve particular attention: the need for training and funding. Successful CEnR requires training for community members to increase knowledge of the research process and of basic human subject protections, as well as training of researchers on strategies for respectful engagement of communities. [69, 71–73][72**] However, too few opportunities for such training exist, especially at the local level.

While some forms of CEnR (such as exit interviews on participant satisfaction) are very affordable and low burden, other more robust forms of CEnR require budgetary support. Expenses may include: hiring diverse staff, translating documents, disseminating results to the community, and tracking hard-to-reach participants.[14] The biggest funding challenge is typically faced at the conclusion of a particular project when bridge funding is required to sustain community-research partnerships.[74]

Conclusions

Researchers frequently equate CEnR with community-based participatory research, which can be highly beneficial for researchers, science, and communities, but can also require significant training, resources, and commitment. Researchers would do well to recognize there are many forms of CEnR including some that are relatively low burden, and that some forms of CEnR can enrich virtually any research program involving human participants.

Key Points.

Community-engaged research (CEnR) can take many forms including reviewing studies on community attitudes, forming a community advisory board, hiring a community member as co-investigator, and conducting the study in collaboration with a local service agency.

CEnR can be challenging and requires resources, but it can enhance the quality of science, demonstrate respect toward individuals and communities, and rebuild or establish trust within a community.

Some form of CEnR is feasible and appropriate for nearly all studies involving human participants. This point is more easily recognized when one ceases to identify CEnR with community-based participatory research and other models that may be inappropriate for a given study.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This publication was made possible by grant 1R13MH079690 from NIH-National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and grant UL1 RR024992 from the NIH-National Center for Research Resources (NCRR).

Contributor Information

James DuBois, Hubert Mäder Endowed Professor, Director, Bander Center for Medical Business Ethics and the Social Science Research Group, Saint Louis University.

Brendolyn Bailey-Burch, Research Associate, Missouri Institute of Mental Health.

Dan Bustillos, Assistant Professor, Department of Health Care Ethics, Saint Louis University.

Jean Campbell, Research Associate Professor, Missouri Institute of Mental Health

Linda Cottler, Professor of Epidemiology, Department of Psychiatry at Washington University School of Medicine, Director of the EPRG, Center for Community Based Research, Master of Psychiatric Epidemiology Program.

Celia Fisher, Marie Ward Doty University Chair, Professor of Psychology, Director of the Center for Ethics Education, Fordham University.

Whitney B. Hadley, Research Assistant, Gnaegi Center for Health Care Ethics, Saint Louis University

Jinger G. Hoop, Mental Health Service Line, Edward Hines Jr. Veteran’s Administration Hospital.

Laura Roberts, Chairman and Katharine Dexter McCormick and Stanley McCormick Memorial Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University

Erica K. Salter, Fellow, Gnaegi Center for Health Care Ethics, Saint Louis University.

Joan E. Sieber, Professor Emerita, California State University, East Bay

Richard D. Stevenson, Director of Special Projects, Alliance on Mental Illness, NAMI St. Louis

References

- 1.Westermeyer J. Comorbid schizophrenia and substance abuse: A review of epidemiology and course. The American Journal on Addictions. 2006;15:345–355. doi: 10.1080/10550490600860114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoop J. Ethical Considerations in Psychiatric Genetics. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2008;16:322–338. doi: 10.1080/10673220802576859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biesecker B, Peay H. Ethical issues in psychiatric genetics research: points to consider. Psychopharmacology. 2003;171:27–35. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1502-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slattery L. Assessing the perceptions of african americans toward genetics and genetics research. University of Pittsburgh; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- **5.Hoop J, Roberts L, Hammond K. Genetic testing of stored biological samples: Views of 570 US workers. Genetic Testing and Molecular Biomarkers. 2009;13:331–337. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2008.0117. A survey of 570 employees at a U.S. defense laboratory and an academic medical center on their willingness to have tissue stored for genetic testing, their interest in receiving results of future testing, and their willingness to be contacted for future testing. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DuBois JM. Ethics in mental health research: Principles, guidance, and cases. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shavers V, Lynch C, Burmeister L. Knowledge of the Tuskegee study and its impact on the willingness to participate in medical research studies. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2000;92:563–572. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *8.Thornicroft G, Brohan E, Rose D, et al. Global pattern of experienced and anticipated discrimination against people with schizophrenia: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2009;373:408–15. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61817-6. Conducted face-to-face interviews with people with schizophrenia from 27 different countries on their experiences of discrimination. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rothenberg K, Wang A. The scarlet gene: Behavioral genetics, criminal law, and racial and ethnic stigma. Law and Contemporary Problems. 2006;69:343–365. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones I, Scourfield J, McCandless F, Craddock N. Attitudes towards future testing for bipolar disorder susceptibility genes: a preliminary investigation. J Affect Disord. 2002;71:189–193. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00384-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Milner K, Han T, Petty E. Support for the availability of prenatal testing for neurological and psychiatric conditions in the psychiatric community. Genet Test. 1999;3:279–286. doi: 10.1089/109065799316590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trippitelli C, Jamison K, Folstein M, et al. Pilot study on patients’ and spouses’ attitudes toward potential genetic testing for bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:899–904. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.7.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reeve P, Cornell S, D’Costa B, et al. From our perspective: consumer researchers speak abut their experience in a community mental health research project. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2002;25:403–8. doi: 10.1037/h0094996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prevention CfDCa, Health NIo, Administration FaD et al. (Editors) Building community partnership in research: Recommendations and strategies. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher C. Ethics in drug abuse and related HIV risk research. Applied Developmental Science. 2004;8:91–103. [Google Scholar]

- **17.Sweeney A, Morgan L. The levels and stages of service user/survivor involvement in research. In: Wallcraft J, Schrank B, Amering M, editors. Handbook of service user involvement in mental health research. Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. pp. 25–35. Useful description of the various ways that people with mental health service needs can be engaged in CEnR. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmed SM, Beck B, Maurana CA, Newton G. Overcoming barriers to effective community-based participatory research in US medical schools. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2004;17:141–51. doi: 10.1080/13576280410001710969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *19.Campbell J. ‘We are the evidence’ an Examination of service user research involvement as voice. In: Wallcraft J, Schrank B, Amering M, editors. Handbook of service user involvement in mental health research. Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. pp. 113–137. An account of the ethical and social justification for CEnR in mental health research. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Department of Health and Human Services. Protection of Human Subjects (45CFR46) 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.European Medicines Agency. ICH Topic E 6 (R1) Guideline for Good Clinical Practice. London: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baylis F. IRBs: Protecting the well-being of subject-participants with mental health disorders that may affect decisionmaking capacity. Account Res. 1999;7:183–199. doi: 10.1080/08989629908573951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Angermeyer MC, Holzinger A. Is there Currently a Boom of Stigma Research in Psychiatry? An Analysis of Scientific journals Psychiatrische Praxis. 2005;32:399–407. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-915283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carey MP, Morrison-Beedy D, Carey KB, et al. Psychiatric outpatients report their experiences as participants in a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 2001;189:299–306. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200105000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chu AT, DePrince AP, Weinzierl KM. Children’s perception of research participation: Examining trauma exposure and distress. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 2008;3:49–58. doi: 10.1525/jer.2008.3.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen CI. Consumer preferences for psychiatric research. Psychiatric Services. 2000;51:936–937. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.7.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DuBois JM, Callahan O’Leary C, Cottler LB. The Attitudes of Females in Drug Court Toward Additional Safeguards in HIV Prevention Research. Prevention Science. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0136-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fogas BS, Oesterheld JR, Shader RI. A retrospective study of children’s perceptions of participation as clinical research subjects in a minimal risk study. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2001;22:211–6. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200108000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hummer M, Holzmeister R, Kemmler G, et al. Attitudes of patients with schizophrenia toward placebo-controlled clinical trials. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2003;64:277–281. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *30.Kaminsky A, Roberts LW, Brody JL. Influences Upon Willingness to Participate in Schizophrenia Research: An Analysis of Narrative Data From 63 People With Schizophrenia. Ethics & Behavior. 2003;13:279–302. doi: 10.1207/S15327019EB1303_06. Presents qualitative research data from interviews with patients with schizophrenia on the factors that influence their decisions whether to participate in research studies. Different response patterns were found for those with versus those without prior research experience. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kassam-Adams N, Newman E. Child and parent reactions to participation in clinical research. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2005;27:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kerkorian D, Traube DE, McKay MM. Understanding the African American Research Experience (KAARE): Implications for HIV Prevention. Social Work in Mental Health. 2007;5:295–312. doi: 10.1300/J200v05n03_03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kitchin R. The researched opinions on research: Disabled people and disability research. Disability & Society. 2000;15:25–47. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marshall R, Spitzer R, Vaughan S, et al. Assessing the subjective experience of being a participant in psychiatric research. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:319–21. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murphy MR, Escamilla MI, Blackwell PH, et al. Assessment of caregivers’ willingness to participate in an intervention research study. Research in Nursing & Health. 2007;30:347–55. doi: 10.1002/nur.20186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberts LW, Warner TD, Brody JL. Perspectives of patients with schizophrenia and psychiatrists regarding ethically important aspects of research participation. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:67–74. doi: 10.1176/ajp.157.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosen C, Grossman LS, Sharma RP, et al. Subjective evaluations of research participation by persons with mental illness. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 2007;195:430–5. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000253785.81700.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schafer I, Gschwend C, Karow A, Naber D. Attitudes of patients with schizophrenia to psychiatric research. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 2008;12:165–170. doi: 10.1080/13651500701636502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Slomka J, Ratliff EA, McCurdy SA, et al. Decisions to participate in research: views of underserved minority drug users with or at risk for HIV. AIDS Care. 2008;20:1224–32. doi: 10.1080/09540120701866992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *40.Ulivi G, Reilly J, Atkinson JM. Protection or empowerment: Mental health service users’ views on access and consent for non-therapeutic research. Journal of Mental Health. 2009;18:161–168. Reports on results from focus groups with mental health service users on their preferences regarding recruitment and consent in non-therapeutic research. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wagner KD, Martinez M, Joiner T. Youths’ and Their Parents’ Attitudes and Experiences About Participation in Psychopharmacology Treatment Research. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2006;16:298–307. doi: 10.1089/cap.2006.16.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fisher CB, Wallace SA. Through the community looking glass: reevaluating the ethical and policy implications of research on adolescent risk and sociopathology. Ethics Behav. 2000;10:99–118. doi: 10.1207/S15327019EB1002_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fisher CB, Oransky M, Mahadevan M, et al. Marginalized populations and drug addiction research: realism, mistrust, and misconception. IRB. 2008;30:1–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *44.Oransky M, Fisher CB, Mahadevan M, Singer M. Barriers and Opportunities for Recruitment for Nonintervention Studies on HIV Risk: Perspectives of Street Drug Users. Substance Use & Misuse. 2009;44:1642–1659. doi: 10.1080/10826080802543671. Reports findings from a focus group study with urban drug users on their fears and attitudes toward recruitment for non-intervention HIV studies. Issues explored include stigma, trust, and recruitment payments. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fisher CB. Adolescent and parent perspectives on ethical issues in youth drug use and suicide survey research. Ethics Behav. 2003;13:303–32. doi: 10.1207/S15327019EB1304_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Minogue V, Boness J, Brown A, Girdlestone J. The impact of service user involvement in research. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance. 2005;18:103–112. doi: 10.1108/09526860510588133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levkoff SE, Levy BR, Weitzman PF. The matching model of recruitment. Journal of Mental Health and Aging. 2000;6:29–38. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ochocka J, Janzen R, Nelson G. Sharing power and knowledge: professional and mental health consumer/survivor researchers working together in a participatory action research project. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2002;25:379–87. doi: 10.1037/h0094999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **49.Ross LF, Loup A, Nelson RM, et al. The Challenges of Collaboration for Academic and Community Partners in a Research Partnership: Points to Consider. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 2010;5:19–32. doi: 10.1525/jer.2010.5.1.19. Explores key points to consider for academic and community partners as they engage in various stages of community-based participatory research. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fisher CB, Hoagwood K, Boyce C, et al. Research ethics for mental health science involving ethnic minority children and youths. Am Psychol. 2002;57:1024–40. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.57.12.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brown P, Morello-Frosch R, Brody J, et al. IRB challenges in multi-partner community-based participatory research. In: the American Sociological Association annual meeting; Sheraton Boston the Boston Marriott Copley Place. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Quandt S, McDonald J, Bell R, Arcury T. Aging research in multi-ethicnic rural communities: Gaining entree through community involvement. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 1999;14:113–130. doi: 10.1023/a:1006625029655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.American Psychological Association. Guidelines on multicultural education, training, research, practice, and organizational change for psychologists. Washington DC: 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smedley BB, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washingtonm DC: Institute of Medicine of the National Academies; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barnes M, Davis A, Tew J. There ought to be a better way - Users’ experiences of compulsion under the 1983 Mental Health Act. Department of Social Policy and Social Work; Birmingham: The University of Birmingham; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Happell B, Roper C. Consumer participation in mental health research: articulating a model to guide practice. The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. 2007;15:237–241. doi: 10.1080/10398560701320113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Levy D, Brink S. A Change of Heart: How the people of Framingham, Massachusetts, helped unravel the mysteries of cardiovascular disease. New York: Knopf; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kessler R, Chiu W, Demler O, Walters E. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–709. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kessler RC. The Epidemiology of Major Depressive Disorder: Results From the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Anthony JC, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry. 2007;6:168–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Striley C, Callahan C, Cottler L. Enrolling, retaining and benefitting out-of-treatment drug users in intervention research. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 2008:19–25. doi: 10.1525/jer.2008.3.3.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cottler L, Compton W, Ben-Abdallah A, et al. Achieving a 96. 6 percent follow-up rate in a longitudinal study of drug abusers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1996;41:209–217. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01254-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Melton GB, Levine RJ, Koocher GP, et al. Community consultation in socially sensible research: Lessons from clinical trials on treatment for AIDS. American Psychologist. 1988;43:573–581. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.43.7.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.US Department of Health and Human Services FaDA (Editor) Guidance for institutional review boards, clinical investigators, and sponsors: Exception from informed consent requirements for emergency research. 2000 http://fda.gov/ora/compliance_ref/bimo/emrfinal.pdf.

- 65.Emanuel E, Wendler D, Grady C. What makes clinical research ethical? JAMA. 2000;283:2701–2711. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.20.2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. The Belmont report: Ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fisher CB. Participant consultation: Ethical insights into parental permission and confidentiality procedures for policy relevant research with youth. In: Lerner RM, Jacobs F, Wertlieb D, editors. Handbook of applied developmental science. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. pp. 371–396. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morrell-Bellai T, Boydell K. The experience of mental health consumers as researchers. Canadian journal of community health. 1994;13:97–110. doi: 10.7870/cjcmh-1994-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **69.Delman J, Lincoln A. Service users as paid research workers: Principles for active involvement and good practice guidance. In: Wallcraft J, Schrank B, Amering M, editors. Handbook of service user involvement in mental health research. Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. pp. 139–151. Practical guidance from mental health service users on effective involvement of services users as paid members of the research team. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dubler N, Liebman C. Bioethics Mediation: A Guide to Shaping Shared Solutions. New York: United Hospital Fund of New York; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Horsfall J, Cleary M, Walter G, Malins G. Challenging conventional practice: Placing consumers at the centre of the research enterprise. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2007;28:1201–1213. doi: 10.1080/01612840701651488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **72.Ross LF, Loup A, Nelson RM, et al. Nine Key Functions for a Human Subjects Protection Program for Community-Engaged Research: Points to Consider. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 2010;5:33–48. doi: 10.1525/jer.2010.5.1.33. Overview of the ethical considerations that arise most prominently in community engaged research. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Goodman MS, Dias JJ, Stafford JD. Increasing research literacy in minority communities: CARES Fellows Training Program. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 2010;5:xx–xx. doi: 10.1525/jer.2010.5.4.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Israel B. Challenges and facilitating factors in sustaining community-based participatory research partnerships: Lessons learned from the Detroit, New York City and Seattle urban research centers. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2006;83:1022–1040. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9110-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]