Abstract

In this paper we present a novel method for genome ranking according to gene lengths. The main outcomes described in this paper are the following: the formulation of the genome ranking problem, presentation of relevant approaches to solve it, and the demonstration of preliminary results from prokaryotic genomes ordering. Using a subset of prokaryotic genomes, we attempted to uncover factors affecting gene length. We have demonstrated that hyperthermophilic species have shorter genes as compared with mesophilic organisms, which probably means that environmental factors affect gene length. Moreover, these preliminary results show that environmental factors group together in ranking evolutionary distant species.

Keywords: adaptation, evolution of prokaryotes, orthologs, machine learning, dimension-reduction techniques, factor analysis, clustering, rating, ranking

Introduction

Evolution of protein coding sequences remains an obscure issue in the molecular evolution of both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. In this paper we focus exclusively on prokaryotes. In prokaryotes, the main driving force in shaping gene length is a point mutation, while in addition to point mutations, eukaryotic variations of gene length may be often caused by other factors,1 such as insertion of mobile elements (transposons and retrotransposons), change to an alternative translation start,2 and so on. We will refer to the protein coding sequences as simply “genes.” The majority of prokaryotic genes have homologs in a variety of genomes. Different homologs of a gene may significantly vary in length. Point mutations can change gene length in a few ways. One of the possible paths for lengthening (or shortening) a gene is stop codon shift.3 Single nucleotide substitutions can destroy the existing stop codon, leading to uninterrupted translation up to the next stop codon in the gene’s reading frame, or create a premature stop codon via a nonsense mutation.

Furthermore, short indels-caused frameshifts near the 3′-end of a gene may lead to premature stop codons (shortening) or to translation past the existing stop codon (lengthening). A start codon drift can also occur. Reduction of gene length may happen due to the mutation of a start codon, and a combination of mutations in the upstream region may lead to lengthening of a gene. Whether variations of gene lengths are neutral (some genes become longer than their predecessors, while other genes become shorter, and the sizes of these factions are randomly different from organism to organism) or depend on organismal evolution, and adaptation is still an open question.

This paper is an attempt to review several relevant methods. We hypothesize that the ranking of genomes according to lengths of their genes is the most appropriate approach in revealing evolutionary driving factors. For example, we expect that hyperthermophiles should have the shortest genes.

The genome ranking problem may be presented in the following way: given a set of annotated prokaryotic genomes, the task is to rank each prokaryotic genome according to its gene lengths. Until now, this problem has been addressed by a (naive) dimension reduction technique (DRT) of the averaging method: denote length of gene k in genome i as; the ranking is then obtained by the averaging method as, where Ri is the set of genes in the ith genome.4,5 This method has many drawbacks, especially pronounced for annotated genomes. For example, in Skovgaard et al,6 the following weakness of the method is mentioned: in microbial genomes, some annotated genes are actually not protein-coding genes, but rather open reading frames that occur purely by chance; as a result, too many short genes are annotated across genomes. Even taking only those genes that have orthologs in other genomes does not remove this main weakness. Below we present an example of averaging to a sparse data set.

Suppose that we want to rank genomes A, B, and C according to gene families a, b, and c. From the first row of the Table 1, we see that the genome A contains genes a and c with lengths 800 and 100, correspondingly; the genome A does not have the gene b. An intuitive order of genomes implied by the gene lengths is A, C, B. On the other hand, taking the genome average gene length does not agree with the intuitive order; it contradicts with the ordering of genomes (B, C) according to the gene b, and the ordering of the genomes (A, B) and (B, C) according to the gene c.

Table 1.

Following an example from (Hochbaum et al).20

| Gene families | Average | A-ran king | Intuitive ranking | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| a | b | c | ||||

| A | 800 | 100 | 450 | 2 | 1 | |

| B | 200 | 600 | 400 | 1 | 3 | |

| C | 900 | 100 | 500 | 500 | 3 | 2 |

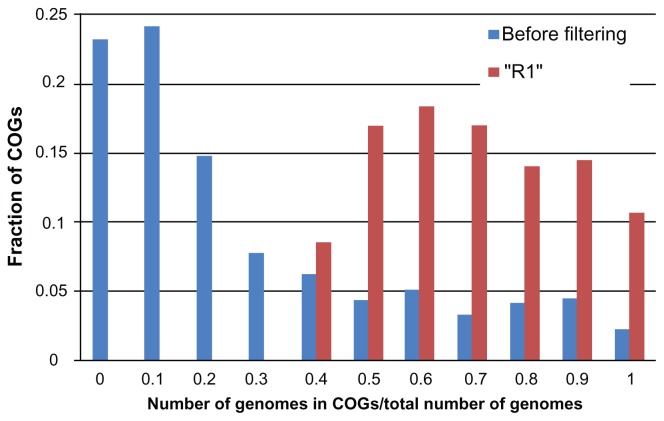

Hence, we present the corrected formulation of the genome ranking problem: given a set of prokaryotic genomes, a set of genes from a given gene family (GF), and the gene lengths of each genome-GF pair, the genome ranking problem is to rate each prokaryotic genome according to its gene lengths. The available data is sparse: prokaryotic genomes do not contain every GF. Figure 1 shows that less than 2.5% of all genomes contain all possible COGs.

Figure 1.

Histogram of number of genomes contained in each COG.

The main outcomes described in this paper are the following: the formulation of the genome ranking problem, presentation of relevant methodologies to solve it, and demonstration of preliminary results from prokaryotic genomes ordering.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews ordering methods: finding a ranking vector by optimization of a sum of Kendall’s Tau rank-correlation coefficients and obtaining a ranking vector by dimension-reduction methods. Section 3 compares the prokaryotic genome ranking problem with the sports rating problem. Section 4 presents an example of genome ranking using a small dataset. Section 5 is the main contribution of this paper, that is, applicability of the genome ranking to uncover factors affecting gene length.

Review of Dimension-Reduction Techniques

In this section we focus on the unsupervised learning problem to reveal hidden factors. Unsupervised learning techniques can be classified as cluster- analysis or dimension-reduction techniques. Different applications of clustering techniques with regards to a problem of genome classification are reviewed in Bolshoy and Vokovich.7 In particular, the problem of genome classification based on gene lengths is also studied in Bolshoy and Volkovich8 and Korenblat et al.9

Cluster analysis approach addresses the following problem: given information about n objects, cluster these objects into groups so that objects belonging to the same cluster are similar in some sense. Cluster analysis methods such as k-means, hierarchical clustering, and Gaussian mixture models aim to find a partition of objects so that the objects on each subset (cluster) share some common traits. Genome clustering methods define a partition of genomes into clusters, with genomes belonging to the same cluster sharing common properties, such as a phylogenetic signal, such as shown in Korenblat et al,9 or common regulatory signals, as suggested in Kozobay-Avraham et al.10,11 Cluster analysis can substantially assist in revealing factors affecting gene length. Clustering is not a straightforward natural way to reveal these factors; however, it may be a useful step in heuristically constructed procedures of rating. Here we would like to present alternative, more natural approaches, that is, dimension-reduction techniques (DRTs).

DRTs solve the following problem: given an n × k matrix, R, find the n × k′ matrix with k′ < k that best captures the content in the original matrix according to certain criteria. For the genome segmentation problem, R is the matrix containing gene lengths’ distribution of k GF by n prokaryotic genomes, and the output is an n × 1 vector that captures relative “gene-length’s tendency” of the prokaryotic genomes. Some of the widely used DRTs are principal component analysis (PCA),12–14 factor analysis (FA),14 multidimensional scaling (MDS),15,16 and averaging.

In essence, PCA seeks to reduce the dimension of the data by finding a few orthogonal linear combinations (the principal components) of the original variables with the largest variance. The first principal component is the linear combination with the largest variance; in this sense, it is the one-dimensional vector that best captures the information contained in the original data.

Factor analysis assumes that the measured variables depend on some unknown common factors. The goal of FA is to uncover them. Typical examples include variables defined as various test scores of individuals, as such scores are thought to be related to a common “intelligence” factor. Here the measured variables are the gene lengths in a prokaryotic genome, and the indeterminate factors of interest are taxonomic, environmental, or genomic properties affecting the prokaryotic genome’s proclivity for shorter gene lengths.

Given n items in a k-dimensional space and an n × n matrix of distances among the items, MDS produces a k′-dimensional, k′ < k, representation of the items such that the pairwise distances among the n points in the new space are similar to the distances in the original data.

For PCA and FA, missing data pose serious problems.17–19 In the genome ranking problem, assuming full data is equivalent to assuming that every prokaryotic genome has representatives of all gene families. This assumption does not hold for a heterogeneous set of prokaryotic genomes. The PCA and FA methods require that the missing values are estimated and artificially imputed. While modern implementations of PCA and FA can handle imputed values, they require the imputed values to be consistent with an underlying stochastic model for the data. There is not enough data to fit an underlying stochastic model for the genome-ranking task. Thus, PCA and FA in spite of being so popular in other fields are not appropriate to solve our problem.

We are grateful to Hochbaum for bringing our attention to the conceptually similar problem of rating customers by their adoption promptness.20 It seems that rating customers as well as genome ranking may be undertaken by separation-deviation approach21 that was used for group decision making22 and country-credit risk rating.23

Another approach to the ranking problem is to solve an optimization problem using Kendall tau rank correlation coefficient.24 This coefficient provides a measure of the degree of correspondence between two vectors. In particular, it assesses how well the order of the elements of the vectors is preserved. In Hochbaum et al,20 it was noted that finding the customer rating vector that maximizes Kendall tau rank correlation coefficient is a good alternative to other optimization methods (reviewed below in 2.1–2.3), and the authors believe that it is appropriate to use Kendall tau rank correlation coefficient for measuring how well the customer ratings recovers “true ranking.” However, in Hochbaum et al,20 it is also mentioned that finding solution that maximizes Kendall tau rank correlation coefficient is a difficult task because the problem is (non-deterministic polynomial-time) (NP)-hard.25 Another drawback of this approach is ignoring the absolute values of dissimilarity between elements. In spite of these problems, we believe that the approach to using Kendall tau rank-correlation coefficient is a superior way to reveal the true ordering of the genomes, at least in the case of a relatively small amount of genomes.

Review of multidimensional scaling for genome ranking

Multidimensional scaling (MDS) aims to approximate given nonnegative dissimilarities, δij, among pairs of objects, i and j, by distances between points in an m-dimensional MDS configuration X. Here X, the configuration, is an n × m matrix with the coordinates of the n objects in ℛm. The most common function to measure the fit between the given dissimilarities, δij, and distances, dij(X), is STRESS, defined as

| (1) |

where wij is a given nonnegative weight reflecting the importance or precision of the dissimilarity δij. Note that wij can be set to 0 if δij is unknown. dij(X) is a vector norm, defined as with given parameter q ≥ 1. Usually, dij (X) is the L2 norm (q = 2) or the L1 norm (q=1).

In a useful MDS technique, the three-way MDS, for each pair of objects we are given K dissimilarity measures from different “replications” (different paralogs in our case). This technique is referred to as three-way MDS because the input is a three-dimensional matrix, [δijk], as opposed to the two-dimensional matrix in “classic” MDS. The objective function of three-way MDS is defined as,26

| (2) |

Unidimensional scaling (UDS) is the important one-dimensional case of MDS where the configuration X is an n × 1 matrix. Therefore UDS seeks to approximate the given dissimilarities by distances between points in a one-dimensional space.

In our particular application, ranking prokaryotic genomes according to their gene length proclivity, the input data is a matrix R with rik giving the gene length (relative to GF) of genome i for GF k. This matrix is, in general, incomplete and has many missing elements. The objective is to assign each genome i to a scale x such that xi most accurately recovers the across-genome gene lengths. In order to solve our problem, we can setup the following three-way UDS problem:

| (3) |

Here the objective is that genomes with high dissimilarities have dissimilar gene lengths and should be placed “far from each other” in the desired scale x.

We have to note the most serious drawback of formulating our genome ranking problem as the three-way UDS problem (3): by calculating the dissimilarities as |rik − rjk |, - three-way UDS problem (3) ignores the so-called directionality of dominance that is the sign of (rik rjk −). There are ways to overcome this difficulty: there are papers,27,28 that consider the case where the dissimilarities are given in a complete skew-symmetric matrix (ie, δij = −δij).

Genome ranking via the separationdeviation model

Consider a set of genomes, identified by the index i. Let rik be the median length of the GF k in a genome i. This means that if there is more than one representative of a GF in a given genome; then in this case the median length is chosen to represent the entire set of paralogs. Each of the n genomes is associated with a K-dimensional vector ri = (ri1,…,rik), recording the gene lengths related to the indexed GF. In the event that the genome does not have a gene, the corresponding entry in the vector is set to zero. Actually, it may be regarded as “missing” or “absent”. Statistically saying, the second option is much more frequent. This means that the dissimilarity matrix [δij] is skew-symmetric and assumed to have no missing entries. (Nevertheless, zero elements rik will be treated differently from non-zeroes through ωijk values).

One of the important features of the separation-deviation model is that the model takes a collection of pairwise comparisons rik − rjk between the objects (genomes) to be classified as an input. In this particular application, the SD-model uses the gene lengths to create pairwise comparisons among the different genomes. (In this sense, formulas (4) and (5) are similar to (3) and dissimilar to (6). There are certain advantages and disadvantages of using δijk≡rik − rjk. For example, a single genome-GF pair can have several possibly conflicting pairwise comparisons.

We are interested in differentiating between genomes that have shorter genes and genomes that have longer genes. In this respect, it is important to emphasize that we are not concerned with the problem of predicting the gene length when a certain genome will acquire a given gene, which is the absolute gene length of each genome. The main motivation for considering pairwise comparisons is given below.

While the specific lengths for different genes might have a high variation, the relative difference in the lengths might have less variation. So, for example, the genome for Helicobacter pylori has genes a and c with lengths 800 and 100, respectively, and genome Bacillus subtilis has the same genes with lengths 900 and 156, respectively. Just considering Helicobacter gene lengths is impossible to determine if this genome adopts short or long genes; however, comparing the genes of H. pylori with B. subtilis we can determine that H. pylori has “shorter genes” than B. subtilis.

Here are the formulas for SD:

| (4) |

| (5) |

Let us set ωijk equal to 1 if both genomes i and j have a gene k and set ωijk equal to 0 otherwise. Following Hochbaum et al20 we set wijk equal to ωijk. Similarly, we set vik equal to 1 if genome i have a gene k, and set vik equal to 0 otherwise. In problems (4) and (5) the parameter M should be chosen in a way such that the separation penalty is the dominant term in the optimization problem; the deviation penalty is only used to choose among the feasible solutions with minimum separation penalty.

The SD optimization model is efficiently solvable, resulting in a scalar value for each prokaryotic genome representing their overall score based on gene lengths.

There are numerous advantages but also some concerns regarding usage of the SD-model for the genome ranking problem. First we mention the advantages of the SD-model:

The SD-model is an approach for unsupervised learning and hence it does not require a training set.

The SD-model works well (without any need for data preprocessing) in situations where the information matrix is sparse.

The SD algorithm has a polynomial time complexity.

The SD-model does not rely on specified distributions for different classes, and there is no requirement of any specific sample size.

Here are the concerns whether the following properties of the SD-model are good or bad for the purpose of genomes ranking:

The SD-model can use subjective and unreliable judgments as an input and produce a misleading output with realistically-looking confidence levels.

The SD-model uses a collection of pairwise comparisons rik − rjk between the objects (genomes) as an input.

In this manuscript we scrutinize another approach presented in the following subsection, which does not take into account the value of difference rik-rkj.

Maximization of Kendall tau rank correlation coefficient

Kendall’s rank correlation coefficient τ provides a distribution free test of independence and a measure of the strength of dependence between two variables a and b. If the a is just [1, 2, …, n] then τ measures how well b is sorted. Let us note υ = [1, 2, …, n]. A scale x is a permutation of υ. In our application (to rank prokaryotic genomes according to their gene length) the input is a matrix R with rik containing gene lengths (relative to GF) of genome i for GF k. The goal is to assign each genome i to a scale x such that xi most accurately recovers the across-genome gene lengths. “Most accurately” here means achieving the maximum of (6):

| (6) |

mk—is a number of non-zero rik elements.

Because solving of this optimization problem is NP-hard,25 heuristic methods, such as the simulated annealing procedure (SAP) or another meta-heuristics, should be used. In the next section we present our implementation of SAP and results of its application.

Comparison of the Prokaryotic Genome Ranking Problem with the Problem of Sports Rating

In many sports there is an officially accepted world ranking. Tennis has its (Association for Tennis Professionals) ATP world ranking, golf has the Sony world ranking, and football (soccer, in the United States and Canada), its Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) ranking. These rankings create some measures of a player’s or a team’s success and are sometimes used for seeding or prize money. The approaches for ranking may differ; however, they may be useful for solving our problem. Genome is analogous to a player (or a team), a gene family (GF) is analogous to a tournament, and gene lengths correspond to tournament points.

The ATP tennis ranking is based on tournament performance and bonus points. A player gained tournament points depending on how far in a tournament he/she progressed, and the quality of a tournament. For our problem, formula (6) would be changed to

| (7) |

where ωk reflects the “quality” of a GF k (developing this approach is in progress).

An exception to the ad hoc rating systems used in most sports is the Elo rating system utilized in chess. This purely quantitative rating system is based on exponential smoothing of a player’s rating depending on the actual proportion of victory compared with that expected given the ratings of the opponents. Various authors have suggested using exponential smoothing methods for rating in other sports, such as those described by Strauss and Arnold29 for racquetball and Clarke30 for squash. However, there are difficulties in ranking tennis players: the tournaments are played on different surfaces (grass, clay, synthetic, etc.). Most players have a favorite surface, and their performance level changes with different surfaces. We may see a direct analogy to protein families here, so the Elo rating may be less appropriate to genome ranking problem.

Ranking Genomes From a Small Dataset

Description of the database of clusters of orthologous groups of proteins

There are several ways to define a gene (protein) family.31–33 The presented algorithm is evaluated on the subset of the database of clusters of orthologous groups of proteins (COGs). The principles of the database construction are described in.34–37 The COGs were constructed by applying the criterion of consistency of genome-specific best hits to the results of an exhaustive comparison of all protein sequences from these genomes. The data in COGs are updated continuously following sequencing new prokaryotic genomes. For example, at some point in the year 2012, proteins from a total of about 1500 complete genomes were assigned to more than 4500 COGs.

COGs are widely used in comparative genomics by a number of research groups.38–42

100-genomes’ dataset

The results presented below are obtained using a subset containing randomly selected genomes from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) genomic database and COGs present in these genomes. This small dataset R1 consists of 100 genomes out of 1496. It contains 9 archaeal and 91 eubacterial genomes. Table 2 contains a list of these genomes.

Table 2.

List of genomes in a ranking order.

| Rank | Domain | Name |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Archaea | Archaeoglobus fulgidus dsm 4304 |

| 2 | Bacteria | Thermotoga sp. rq2 |

| 3 | Archaea | Thermococcus onnurineus na1 |

| 4 | Archaea | Thermoplasma volcanium gss1 |

| 5 | Bacteria | Thermotoga neapolitana dsm 4359 |

| 6 | Archaea | Thermoplasma acidophilum dsm 1728 |

| 7 | Archaea | Pyrococcus abyssi ge5 |

| 8 | Bacteria | Aquifex aeolicus vf5 |

| 9 | Bacteria | Campylobacter concisus 13826 |

| 11 | Archaea | Thermococcus sibiricus mm 739 |

| 12 | Archaea | Pyrococcus horikoshii ot3 |

| 12 | Bacteria | Campylobacter curvus 525.92 |

| 13 | Bacteria | Helicobacter felis atcc 49179 |

| 13 | Bacteria | Dictyoglomus thermophilum h-6–12 |

| 15 | Bacteria | Streptococcus pneumoniae p1031 |

| 16 | Bacteria | Streptococcus agalactiae a909 |

| 18 | Bacteria | Bacillus cereus atcc 14579 |

| 19 | Bacteria | Mycoplasma pulmonis uab ctip |

| 20 | Bacteria | Bacillus cytotoxicus nvh 391–98 |

| 20 | Bacteria | Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b |

| 20 | Archaea | Methanosalsum zhilinae dsm 4017 |

| 21 | Bacteria | Streptococcus agalactiae 2603v/r |

| 22 | Bacteria | Caldicellulosiruptor bescii dsm 6725 |

| 25 | Bacteria | Bacillus amyloliquefaciens dsm 7 |

| 26 | Bacteria | Mycoplasma fermentans m64 |

| 27 | Bacteria | Rickettsia canadensis str. mckiel |

| 28 | Bacteria | Ureaplasma parvum serovar 3 |

| 29 | Bacteria | Francisella sp. tx077308 |

| 29 | Bacteria | Streptococcus zooepidemicus |

| 30 | Bacteria | Melissococcus plutonius atcc 35311 |

| 30 | Bacteria | Mycoplasma leachii pg50 |

| 31 | Bacteria | Bacillus pumilus safr-032 |

| 32 | Bacteria | Pediococcus pentosaceus atcc 25745 |

| 34 | Bacteria | Mycoplasma genitalium g37 |

| 35 | Bacteria | Enterococcus faecalis v583 |

| 39 | Bacteria | Legionella pneumophila str. paris |

| 40 | Bacteria | Natranaerobius thermophilus |

| 40 | Bacteria | Brachyspira pilosicoli 95/1000 |

| 40 | Bacteria | Ruminococcus albus 7 |

| 41 | Bacteria | Bacillus thuringiensis str. al hakam |

| 41 | Bacteria | Brevibacillus brevis nbrc 100599 |

| 41 | Bacteria | Geobacter uraniireducens rf4 |

| 42 | Bacteria | Geobacter lovleyi sz |

| 44 | Bacteria | Neisseria meningitidis 053442 |

| 44 | Bacteria | Coxiella burnetii rsa 331 |

| 45 | Bacteria | Mycoplasma pneumoniae m129 |

| 46 | Bacteria | Maribacter sp. htcc2170 |

| 47 | Bacteria | Laribacter hongkongensis hlhk9 |

| 48 | Bacteria | Pseudogulbenkiania sp. nh8b |

| 51 | Bacteria | Zobellia galactanivorans |

| 52 | Bacteria | Dechloromonas aromatica rcb |

| 53 | Bacteria | Sodalis glossinidius str. ‘morsitans’ |

| 54 | Bacteria | Erwinia amylovora atcc 49946 |

| 55 | Archaea | Halalkalicoccus jeotgali b3 |

| 55 | Bacteria | Escherichia coli bw2952 |

| 55 | Bacteria | Gramella forsetii kt0803 |

| 55 | Bacteria | Lactobacillus gasseri atcc 33323 |

| 55 | Bacteria | Borrelia turicatae 91e135 |

| 60 | Bacteria | Klebsiella variicola at-22 |

| 60 | Bacteria | Candidatus riesia pediculicola usda |

| 61 | Bacteria | Salmonella enterica subsp. arizonae |

| 61 | Bacteria | Eubacterium eligens atcc 27750 |

| 62 | Bacteria | Sphingobacterium sp. 21 |

| 63 | Bacteria | Methylomonas methanica mc09 |

| 63 | Bacteria | Dyadobacter fermentans dsm 18053 |

| 64 | Bacteria | Yersinia enterocolitica subsp |

| 67 | Bacteria | Chlamydophila pneumoniae ar39 |

| 68 | Bacteria | Cronobacter turicensis z3032 |

| 69 | Bacteria | Spirochaeta smaragdinae dsm 11293 |

| 71 | Bacteria | Yersinia pseudotuberculosis pb1/+ |

| 72 | Bacteria | Pelodictyon phaeoclathratiforme |

| 72 | Bacteria | Tropheryma whipplei tw08/27 |

| 73 | Bacteria | Xanthomonas oryzae |

| 73 | Bacteria | Desulfovibrio vulgaris |

| 74 | Bacteria | Dinoroseobacter shibae dfl 12 |

| 75 | Bacteria | Acidiphilium cryptum jf-5 |

| 77 | Bacteria | Thauera sp. mz1t |

| 77 | Bacteria | Magnetococcus marinus mc-1 |

| 78 | Bacteria | Prosthecochloris aestuarii dsm 271 |

| 79 | Bacteria | Anaerolinea thermophila uni-1 |

| 81 | Bacteria | Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021 |

| 82 | Bacteria | Bordetella petrii dsm 12804 |

| 84 | Bacteria | Chloroflexus aggregans dsm 9485 |

| 84 | Bacteria | Arcanobacterium haemolyticum |

| 85 | Bacteria | Corynebacterium glutamicum r |

| 87 | Bacteria | Cyanothece sp. pcc 7822 |

| 87 | Bacteria | Starkeya novella dsm 506 |

| 87 | Bacteria | Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus |

| 88 | Bacteria | Rhodopseudomonas palustris dx-1 |

| 90 | Bacteria | Rhodospirillum centenum sw |

| 91 | Bacteria | Xanthobacter autotrophicus py2 |

| 92 | Bacteria | Mycobacterium leprae br4923 |

| 93 | Bacteria | Intrasporangium calvum dsm 43043 |

| 94 | Bacteria | Streptomyces scabiei 87.22 |

| 94 | Bacteria | Streptomyces griseus subsp. |

| 96 | Bacteria | Burkholderia rhizoxinica hki 454 |

| 97 | Bacteria | Haliangium ochraceum dsm 14365 |

| 98 | Bacteria | Salinibacter ruber m8 |

| 99 | Bacteria | Rothia dentocariosa atcc 17931 |

| 100 | Bacteria | Bifidobacterium animalis |

Figure 1 (blue bars) illustrates the input data. The complete set related to 1496 genomes consists of 4692 COGs, and, naturally, there are COGs that no genome of R1 has members of these GFs. Therefore, we removed those COGs that are present in less than 35% of genes from R1. After this filtering, our dataset contained 1409 COGs (Fig. 1, red bars).

Gene-length matrix preparation

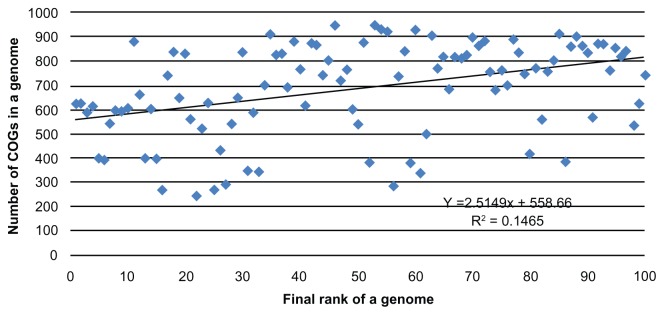

The original data is transformed to the following format: to each (genome, COG) pair we assigned one standardized protein length. For a given COG, each organism is represented by a calculated length—a median length of all paralogous proteins. For example, there are 8 paralogs of a gene tryptophan transporter of high affinity (mtr, sdaC, tdcC, tnaB, tyrP, yhaO, yhjV, and yqeG) in a genome Escherichia coli K12, taxonomy id 83333. These paralogs with lengths 403, 409, 414, 415, 423, 425, 429, and 443 appear as members of COG0814 (amino acid permeases). Only one triplet (83333, COG0814, 419) would be included in the input data. A number of genes vary from genome to genome. Consequently, genomes of the dataset R1 are presented by different number of COGs, that is, from small mycoplasmas and ureaplasma, the smallest and simplest self-replicating organisms with genome sizes from about 540 kb and less than 300 COGs inside to long genomes with more than 900 COGs (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Number of COGs that each genome contains. Genomes are ordered as in Table 2.

Simulated annealing

A variety of combinatorial optimization strategies are available for optimization (3), starting with a bruteforce approach and continuing with deterministic and stochastic approaches.43 The strategy of local pairwise interchange (LOPI) does not guarantee global optimality, but it is very efficient,44 and being enhanced by stochastic techniques, brings good results (manuscript in preparation).

Simulated Annealing45,46 is a generic probabilistic metaheuristics for the global optimization problem of locating a good approximation to the global optimum of a given function in a large search space. We used acceptance probability function in the form α(τ, τ,new, t,) = min(1,eτnew−τ/t). The algorithm was implemented in R using mpiR package to enable parallel processing using HPC Wales computer cluster.

Results and their interpretation

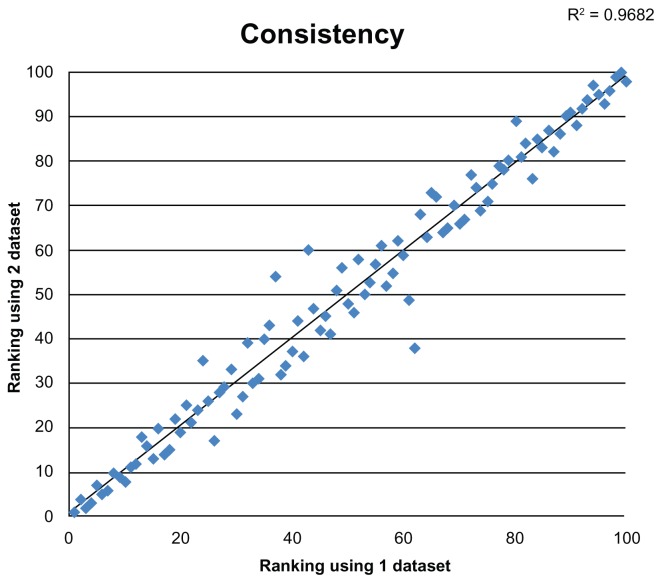

We performed a random selection of 1050 COGs twice (overlap was 777 COGs). For the two subsets of COGs, the resulting rankings are significantly correlated (Fig. 3); the Kendall tau correlation coefficient is 0.908 (2-sided P value < 0.001). Lowest and highest ranks agree the most, while genomes from the middle portion of the ordering show the most deviation.

Figure 3.

Comparison of rankings produced by two different incomplete subsets of COGs.

Figure 2 shows a modest positive tendency to rank genomes that have smaller number of COGs below those with a larger number. However, the number of COGs in a genome is not the major force that affects a rank of a genome. Table 2 aids understanding the driving forces behind the ranking.

Table 2 presents the resulting ranking of the genomes. Different taxonomic groups appear to be tightly clustered within the ordering. For example, the majority of archaeal genomes are placed on the top of the ranking table. Figure 3 and our calculations performed on other genome subsets (unpublished data) has led us to discuss at this stage only the most stable groups: the top (ranked 1–16 in Table 2) and the bottom (ranked 85–100). Among the top 16, 13 hyperthermophiles are the clear majority. There are both archaea and eubacteria in this group.

Among sequenced archaea, there are many organisms living in extreme environments, such as volcanic hot springs, and they are all in the top group. Next to Achaea are Thermotogae bacteria. The name of this phylum is derived from the existence of many of these organisms at high temperatures. Bacteria of Aquificae phylum live in harsh environmental settings. Representatives of Dicyolglomi phylum are also extremely thermophilic. In addition to hyperthermophiles, two campylobacters and one helicobacter accomplish this group. There are no other campylobacters or helicobacters in R1. The two species of archaea that are not hyperthermophiles are placed at ranks 20 and 50.

The opposite end of the spectrum is occupied by Actinobacteria.47 Many species of Actinobacteria are found in soil, including some of the most common soil life, playing important roles in decomposition and humus formation.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated the efficacy of the Kendall tau rank-correlation coefficient for solving the problem of genome ranking. The proposed method is stable, yielding meaningful results on a small test set of prokaryotic genomes. The presented results agree with our prior intuitive ordering, placing thermophilic species on top of the ranking table. Simulated Annealing approach, in combination with parallel implementation of the developed algorithm, allowed developing an efficient method that can be scaled up to include all prokaryotic genomes. Maximization of an average Kendall tau rank correlation coefficient is suitable to assess the ordering of genomes since it has a simple interpretation. For one column, maximization of tau means sorting. For the full input matrix (no missing values), such maximization is equivalent to sorting the table (the input matrix) to get the best average sorting. An extension of this interpretation for our sparse input data is not straightforward but seems very reasonable.

Our approach can be used for various ranking problems, where each subject has multiple categories that needed to be taken into account. For example, ranking of athletes, consumer products, and so on. The method can be further improved by introducing different weights for categories based on their relative importance.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Dorit Hochbaum for bringing our attention to the conceptually similar problem of rating customers. We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Eugene Koonin’s contribution to the formulation of the evolutionary problem. The authors would like to thank HPC Wales and Fujitsu for computational support in implementation of the task, and Ms. Hannah Garbett and Dr. Owain Kerton for useful comments and proofreading the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: AB. Analyzed the data: TT. Wrote the first draft of the manuscript: AB. Contributed to the writing of the manuscript: TT. Agree with manuscript results and conclusions: AB, TT. Developed the structure and arguments for the paper: AB. Made critical revisions and approved final version: AB, TT. All authors reviewed and approved of the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

Author(s)disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

Disclosures and Ethics

As a requirement of publication author(s) have provided to the publisher signed confirmation of compliance with legal and ethical obligations including but not limited to the following: authorship and contributorship, conflicts of interest, privacy and confidentiality and (where applicable) protection of human and animal research subjects. The authors have read and confirmed their agreement with the ICMJE authorship and conflict of interest criteria. The authors have also confirmed that this article is unique and not under consideration or published in any other publication, and that they have permission from rights holders to reproduce any copyrighted material. Any disclosures are made in this section. The external blind peer reviewers report no conflicts of interest.

Funding

TT received computational support from HPC Wales and Fujitsu. TT was also supported in part by NIH grants GM068968 and HD070886.

References

- 1.Sandhya S, Rani SS, Pankaj B, et al. Length variations amongst protein domain superfamilies and consequences on structure and function. PLoS One. 2009;4(3):e4981. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bazykin GA, Kochetov AV. Alternative translation start sites are conserved in eukaryotic genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(2):567–77. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vakhrusheva AA, Kazanov MD, Mironov AA, Bazykin GA. Evolution of prokaryotic genes by shift of stop codons. J Mol Evol. 2011;72(2):138–46. doi: 10.1007/s00239-010-9408-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brocchieri L, Karlin S. Protein length in eukaryotic and prokaryotic proteomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(10):3390–400. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang J. Protein-length distributions for the three domains of life. Trends Genet. 2000;16(3):107–9. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01922-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skovgaard M, Jensen LJ, Brunak S, Ussery D, Krogh A. On the total number of genes and their length distribution in complete microbial genomes. Trends Genet. 2001;17(8):425–8. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02372-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolshoy A, Volkovich Z, Kirzhner V, Barzily Z. Genome Clustering: From Linguistic Models to Classification of Genetic Texts. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bolshoy A, Volkovich Z. Whole-genome prokaryotic clustering based on gene lengths. Discrete Applied Mathematics. 2008;157(10):2370–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korenblat K, Volkovich Z, Bolshoy A. Robustness of the whole-genome prokaryotic clustering based on gene lengths. Computational Biology and Chemistry. 2012;40:20–9. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kozobay-Avraham L, Bolshoy A, Volkovich Z. On clusterization of prokaryotes based on DNA curvature distribution. In: Last M, Szczepaniak PS, Volkovich Z, Kandel A, editors. Advances in Web Intelligence and Data Mining. Studies in Computational Intelligence, Vol. 23. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2006. pp. 361–75. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kozobay-Avraham L, Hosid S, Volkovich Z, Bolshoy A. Prokaryote clustering based on DNA curvature distributions. Discrete Applied Mathematics. 2009;157(10):2378–87. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jollife IT. Principal Component Analysis. New York, NY: Springer; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jolliffe IT. Principal Component Analysis. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mardia KV, Kent JT, Bibby JM. Multivariate Analysis (Probability and Mathematical Statistics) London, UK: Academic Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kruskal JB. Multidimensional-scaling by optimizing goodness of fit to a nonmetric hypothesis. Psychometrika. 1964;29(1):1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kruskal JB, Wish M. Multidimensional Scaling (Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences) Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kosobud R. A Note on a Problem Caused by Assignment of Missing Data in Sample-Surveys. Econometrica. 1963;31(3):562–3. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Afifi A, Elashoff RM. Missing values in multiple-regression. Ann Math Statist. 1964;35(3):1389. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Afifi AA, Elashoff RM. Missing observations in multivariate statistics 1. Review of the literature. JASA. 1966;61(315):595–604. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hochbaum DS, Moreno-Centeno E, Yelland P, Catena RA. Rating customers according to their promptness to adopt new products. Oper Res. 2011;59(5):1171–83. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hochbaum DS. Selection, provisioning, shared fixed costs, maximum closure, and implications on algorithmic methods today. Manage Sci. 2004;50(6):709–23. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hochbaum DS, Levin A. Methodologies and algorithms for group-rankings decision. Manage Sci. 2006;52(9):1394–408. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hochbaum DS, Moreno-Centeno E. Country credit-risk rating aggregation via the separation-deviation model. Optim Method Softw. 2008;23(5):741–62. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kendall M. A new measure of rank correlation. Biometrika. 1938;30(1–2):81–9. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bartholdi J, Tovey CA, Trick MA. Voting schemes for which it can be difficult to tell who won the election. Soc Choice Welfare. 1989;6(2):157–65. [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Leeuw J. Recent Developments in Statistics (Proc European Meeting Statisticians, Grenoble, 1976. Amsterdam: North-Holland; 1977. Applications of convex analysis to multidimensional scaling; pp. 133–45. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hubert L, Arabie P, Meulman J. Combinatorial Data Analysis: Optimization by Dynamic Programming. Phildelphia, PA: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brusco MJ, Stahl S. Bicriterion seriation methods for skew-symmetric matrices. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 2005;58(Pt 2):333–43. doi: 10.1348/000711005X63908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strauss D, Arnold BC. The rating of players in racquetball tournaments. J Appl Stat. 1987;36:163–73. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clarke SR. An adjustive rating system for tennis and squash players. In: de Mestre N, editor. Mathematics and Computers in Sport. Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia: Bond University; 1994. pp. 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tatusov RL, Koonin EV, Lipman DJ. A genomic perspective on protein families. Science. 1997;278(5338):631–7. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sonnhammer EL, Eddy SR, Durbin R. Pfam: a comprehensive database of protein domain families based on seed alignments. Proteins. 1997;28(3):405–20. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(199707)28:3<405::aid-prot10>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barker WC, Hunt LT, George DG, et al. Protein Sequence Database of the Protein Identification Resource (PIR) Protein Seq Data Anal. 1988;1(3):195–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tatusov RL, Natale DA, Garkavtsev IV, et al. The COG database: new developments in phylogenetic classification of proteins from complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(1):22–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koonin EV, Tatusov RL, Rudd KE. Protein sequence comparison at genome scale. Method Enzymol. 1996;266:295–322. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)66020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tatusov RL, Galperin MY, Natale DA, Koonin EV. The COG database: a tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):33–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tatusov RL, Fedorova ND, Jackson JD, et al. The COG database: an updated version includes eukaryotes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2003;4:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gambin A, Slonimski PP. Hierarchical clustering based upon contextual alignment of proteins: a different way to approach phylogeny. C R Biol. 2005;328(1):11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xia Z, Xu H, Zhai J, et al. RNA-Seq analysis and de novo transcriptome assembly of Hevea brasiliensis. Plant Mol Biol. 2011;77(3):299–308. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9811-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shen GM, Dou W, Niu JZ, et al. Transcriptome analysis of the oriental fruit fly (Bactrocera dorsalis) PLoS One. 2011;6(12):e29127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lukjancenko O, Ussery DW, Wassenaar TM. Comparative genomics of Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus and related probiotic genera. Microb Ecol. 2012;63(3):651–73. doi: 10.1007/s00248-011-9948-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Capes MD, DasSarma P, DasSarma S. The core and unique proteins of haloarchaea. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Borg I, Groenen P. Modern Multidimensional Scaling: Theory and Applications. York, PA: Springer-Verlag; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Groenen PJF. The Majorization Approach to Multidimensional Scaling: Some Problems and Extensions. Leiden, The Netherlands: DSWO Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kirkpatrick S, Gelatt CD, Jr, Vecchi MP. Optimization by Simulated Annealing. Science. 1983;220(4598):671–80. doi: 10.1126/science.220.4598.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Metropolis N, Rosenblut AW, Rosenblut MN, Teller AH, Teller E. Equations of state calculations by fast computing machines. J Chem Phys. 1953;21:1087–92. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ventura M, Canchaya C, Tauch A, Chandra G, Fitzgerald G, Chater KvSD. Genomics of Actinobacteria: tracing the evolutionary history of an ancient phylum. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2007;71(3):495–548. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00005-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]