Abstract

Primitive neuroectodermal tumours (PNETs) are aggressive undifferentiated tumours that occur mainly in the central nervous system (CNS). Reviewing the literature, only six cases of primary PNET of the mandible have been reported. These rare tumours are usually overlooked in clinical practice. An 18-year-old woman who presented with dental caries and left cheek swelling was initially diagnosed with facial cellulitis, but the swelling persisted despite adequate intravenous antibiotic therapy. Subsequent ultrasound and MR examinations revealed a tumour originating from the left mandibular ramus. The ultrasonography-guided percutaneous core needle biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of peripheral PNET. The radiographic features of mandibular PNETs are similar to those of PNETs in other regions, except for haemorrhage, necrosis and calcification. In addition, this is the first reported case with sonographic and MR images of this rare tumour, and the first case that was diagnosed based on the ultrasonography-guided percutaneous core needle biopsy. Using these image characteristics, mandibular PNETs can be diagnosed more accurately.

Keywords: mandible, neoplasm, PNET, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, sonography, needle biopsy

Case report

An 18-year-old woman was transferred to the emergency department at the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital at Linkuo and College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taiwan, with progressive painless swelling of the left lower face, with a sensation of numbness and difficulty opening the mouth for 1 month. She had no fever, cough, sore throat, dysphagia, odynophagia or tinnitus. On physical examination, an 8 × 8 cm firm fixed mass with local warmth was noted at the left lateral aspect of her chin. Since she had a prolonged problem with dental caries and left chin swelling, she was admitted with the initial impression of facial cellulitis. However, the facial swelling persisted despite adequate empirical intravenous antibiotic treatment for a presumed infection of dental origin. In addition, the atypical symptoms (gradual painless swelling and sensation of numbness) also increased the risk of neoplastic disease. Therefore, further imaging evaluation of the head and neck was obtained. High-resolution ultrasonography showed a well-defined heterogeneous hypoechoic mass, suggesting a neoplastic lesion, at the left masseter region (Figure 1). MRI of the head and neck revealed a soft-tissue mass arising from the left mandibular ramus and occupying the left masseter compartment. The tumour was isointense to normal muscle on T1 weighted (T1W) images and hyperintense on T2 weighted (T2W) images. It enhanced heterogeneously after the intravenous administration of gadolinium (Figure 2). Bony cortex erosion and involvement of left mandibular canal were also evident, as well as bone marrow replacement, which was seen with isointense signal change on T1W and T2W images. Although facial cellulitis of dental origin was still possible, a neoplasm of the left mandibular ramus was considered the most likely diagnosis.

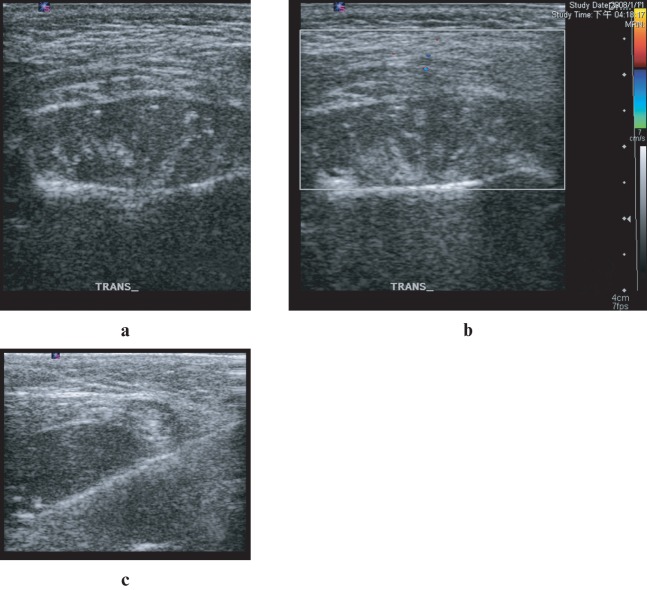

Figure 1.

Ultrasonography (a) and Doppler scan (b) of the left chin revealed a well-defined heterogeneous hypoechoic mass at masseter region. Subsequently, an ultrasonography-guided percutaneous core needle biopsy with an 18 G coaxial cutting needle was performed (c)

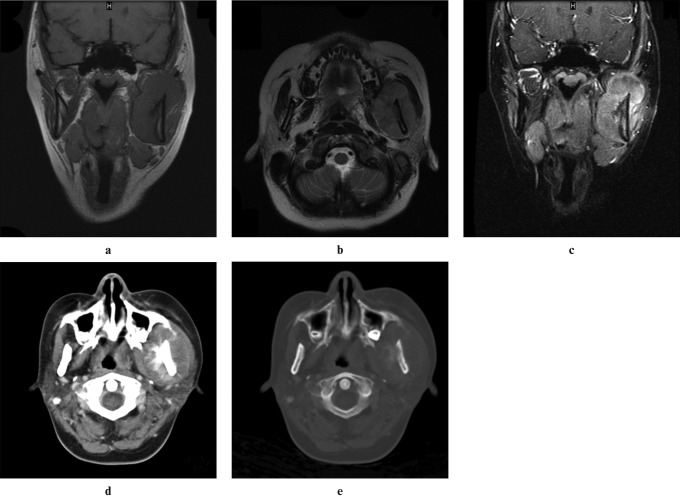

Figure 2.

MRI of the head and neck showed a soft-tissue tumour arising from the left ramus of the mandible occupying the left masticator space. The tumour was isointense to normal muscle on coronal T1W images (a) and hyperintense on axial T2W images (b), and it had heterogeneous enhancement after intravenous administration of gadolinium (c). Bone marrow involvement was also shown on MRI. Enhanced CT of the head and neck in the soft-tissue (d) and bone (e) windows showed cortical destruction and sunburst-like periosteal reaction of left mandibular ramus

An ultrasonography-guided percutaneous core needle biopsy with an 18 G coaxial cutting needle was performed (Figure 1).

Enhanced CT of the head and neck, including chest and abdomen, was performed for further evaluation and tumour staging after the ultrasonography-guided percutaneous core needle biopsy for the left mandibular tumour. It showed the tumour had caused cortical destruction and a sunburst periosteal reaction of the left ramus of the mandible and focal widening of the proximal portion of the left mandibular canal, indicating canal involvement.

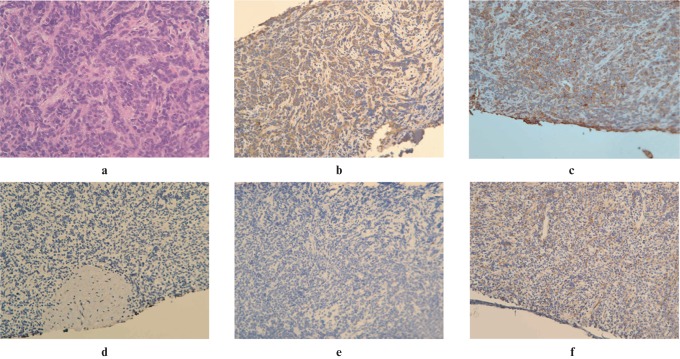

On histopathological examination, the biopsy specimen showed poorly differentiated tumour cells with small blue round or oval nuclei and scant cytoplasm. The tumour cells were mildly positive for desmin, diffusely positive for CD99, and negative for S-100, calponin, HMB-45, CK5/6, AE1/AE3, GFAP (6 F 2) and HHF-35 (Figure 3). Based on these histopathological features and the immunohistochemical pattern, the tumour was diagnosed as a primitive neuroectodermal tumour (PNET). The tumour was a solitary tumour in the left ramus of the mandible with no other primary tumours or distant metastasis and was diagnosed as a primary peripheral PNET arising in the mandible. Oral surgeons were consulted for en bloc resection. However, the tumour was unresectable because of the unacceptable extensive cosmetic and functional destruction that would be caused after resecting the involved portion of the left mandibular ramus. The patient was therefore referred to the haematology department for concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Figure 3.

Poorly differentiated tumour cells with small blue round-to-oval nuclei and scant cytoplasm (a) were seen histologically (×200). The specimen was mildly positive for desmin (b), diffusely positive for CD99 (c), and negative for calponin (d), AE1/AE3 (e) and HHF-35 (f)

Discussion

The PNET, a subtype of the family of small round cell malignancies, was first described in 1918 by Stout.1 These rare tumours are found mostly in the central nervous system (CNS) and, based on their histological features, PNETs are presumed to be aggressive, undifferentiated tumours arising from multipotent embryonic neuroepithelial cells. Rarely, PNETs may be found outside the CNS. These peripheral PNETs are most common in the thoracopulmonary region, kidneys and retroperitoneal area.2 Given their insidious clinical symptoms, variable locations and rarity, the accurate diagnosis of peripheral PNETs poses a challenge for clinicians and radiologists.

The actual incidence of peripheral PNET is difficult to estimate owing to its rarity and because clear diagnostic criteria were established only recently. Although peripheral PNETs can affect any age group, they tend to affect adolescents and young adults more often.3 Some studies have reported a slight male predominance.4 Generally, the prognosis of peripheral PNETs is unfavourable. A combination of adequate surgical resection, effective multi-agent chemotherapy and concurrent radiotherapy if possible is necessary to improve survival. The overall 5-year survival rates for localized and metastatic tumours range from 65% to 74% and 25% to 45%, respectively.5,6 Tumours arising from the paraspinal region and scapular areas respond better to treatment, while abdominal and pelvic PNETs respond poorly.7

Several reviews on the CT and MR features of peripheral PNETs have been published. On CT, PNETs are usually isodense or slightly hypodense compared with normal muscle.2,7,8 Both coarse and fine calcifications are uncommon. Central hypodense areas consistent with tumour necrosis and cystic change are found in large tumours, and sometimes hyperdensities consistent with haemorrhage can be seen. Almost all of these tumours show heterogeneous enhancement after the intravenous administration of an iodine-containing contrast medium. On T1W MRI, most peripheral PNETs are isointense or slightly hyperintense compared with normal muscle. Typical T2W signals are heterogeneous, but are generally hyperintense compared with adjacent normal muscle. A cystic necrotic component and haemorrhagic change are usually obvious on MRI if present. In addition, PNETs tend to displace adjacent structures, instead of invading them directly. Encasement of vessels or trachea is rare. Extension along neural foramens is common in retroperitoneal or paraspinal PNETs.

The first case of mandibular PNET was reported in 2002 as a painless, progressively enlarging lower jaw mass in a 6-year-old girl.9 In the literature, only six cases of primary peripheral PNET arising in the mandible have ever been reported.10-14 The patient age and gender, tumour location, treatment modalities and outcomes are summarised in Table 1. The patients were 4 females and 2 males with ages ranging from 6 to 38 years. The tumours were located around the mandibular symphysis in three cases and in the ramus of the mandible in the other three cases. As in our case, the six reported patients initially presented with a painless swelling of the chin or cheek.

Table 1. General data and clinical course in the seven reported cases.

| Case | Age (years)/gender | Location in the mandible | Treatment modalities | Follow-up (months) | Recurrence/metastasis | Status |

| Ozer9 | 6/female | Mental and parasymphyseal | En bloc resection, post-operative chemotherapy | 10 | Local recurrence, re-operated, tumour free | Alive |

| Sundine10 | 38/female | Mandibular ramus, right | Surgical resection, post-operative chemotherapy, palliative radiation therapy | 18 | Spinal and lung metastases | Dead |

| Alrawi11 | 18/female | Mental and parasymphyseal | Pre-operative chemotherapy, en bloc resection | 14 | No local recurrence or distant metastasis | Alive |

| Votta12 | 18/female | Mental and parasymphyseal | Pre-operative chemotherapy, en bloc resection | 14 | No local recurrence or distant metastasis | Alive |

| Kanaya13 | 38/male | Mandibular ramus, right | En bloc resection, selective neck dissection, post-operative radiation therapy | 36 | No local recurrence or distant metastasis | Alive |

| Anonymous 14 | 11/male | Mandibular ramus, left | Chemotherapy, radiotherapy | 36 | No local recurrence or distant metastasis | Alive |

| Our case | 18/female | Mandibular ramus, left | Chemotherapy, radiotherapy | 14 | No distant metastasis | Alive |

The radiographic features of mandibular PNETs in these cases are compared in Table 2. Ultrasonography of the mandibular PNET was not available in the six reported cases, while a well-defined heterogeneous hypoechoic mass was seen in our patient. On CT, the tumours were isodense to the adjacent muscles in two cases and hypodense in four. MRI was reported only in one previous case. The signal of the tumours was isointense to adjacent muscles on T1W images and hyperintense on T2W images. Heterogeneous peripheral enhancement after the intravenous administration of gadolinium-containing contrast medium was seen in both cases. Moreover, some common features of peripheral PNET, including haemorrhage, necrosis and calcification, were not found in any of the seven cases. This may be because these characters are related to size of tumour, and the location and symptom of the mandibular PNET make it easier to be detected earlier in clinical practice.

Table 2. Summary of the image findings in the seven reported cases.

| Case | Size (cm) | Ultrasonography | Density on CT | MRI signal | Haemorrhage/necrosis/calcification | Enhancement | Neural foramen invasion |

| Ozer9 | 10 × 12 | N/A | Hypodense | N/A | (–)/(–)/(–) | N/A | (–) |

| Sundine10 | N/A | N/A | Isodense | N/A | (–)/(–)/(–) | N/A | Obliteration of the right inferior alveolar canal |

| Alrawi11 | N/A | N/A | Isodense to mild hypodense | N/A | (–)/(–)/(–) | N/A | Obliteration of the right mental foramen and inferior alveolar canal |

| Votta12 | N/A | N/A | Hypodense | N/A | (–)/(–)/(–) | N/A | (–) |

| Kanaya13 | N/A | N/A | Isodense | N/A | (–)/(–)/(–) | N/A | (–) |

| Anonymous 14 | N/A | N/A | Hypodense | T1WI isointense, T2WI slightly hyperintense | (–)/(–)/(–) | Peripheral enhancement | (–) |

| Our case | 3.9 × 2.5 × 6.7 | Well-defined margin, heterogeneous hypoechoic content | Hypodense | T1WI isointense, T2WIhyperintense | (–)/(–)/(–) | Heterogeneous enhancement | Invasion of the left inferior alveolar canal |

N/A, not applicable; T1WI, T1 weighted image; T2WI, T2 weighted image

The most common sonographical differential diagnosis for a focal mass in the masseter region is haemangioma or abscess after a dental procedure. The haemangiomas commonly appear as ill-defined hypoechoic heterogeneous masses containing sinusoidal vascular spaces and phleboliths as well as slow blood flow inside. The abscess in the masseter muscle usually appears as a well-defined hypoechoic heterogeneous mass with peripheral thick wall and containing debris. These sonographical findings of the above differential diagnoses were not revealed on our case, so the suspicion of neoplasm was increased, resulting in the ongoing needle biopsy.

The appearance of the soft-tissue mass wrapping the mandible narrows the radiological differential diagnosis made on CT and MRI and through our consideration, including osteomyelitis, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, osteosarcoma, ameloblastoma and metastasis. Nevertheless, the radiological findings of our presented case lack the presence of sequestrum or abscess formations, large bubbly osteolytic lesions, extensive bony destruction or cervical nodal metastasis. So the possibility that this lesion represented the above differential diagnoses was considered unlikely.

Because of the infection-like clinical findings and superficial location of mandibular PNETs, sonography and ultrasonography-guided percutaneous core needle biopsy are considered the appropriate imaging modality and procedure to confirm this diagnosis, although they were not applied on previously reported cases.

Open surgical biopsy is more invasive with higher morbidity when compared with minimally invasive ultrasonography-guided percutaneous core needle biopsy. Real-time ultrasonographical guidance allows precise needle position, excludes vascular lesions to avoid any interventional complication and provides flexible patient positioning so that needle biopsy can be performed quickly and safely on soft-tissue masses around superficial bone lesions.15-17 Several reports have been published on the usefulness and accuracy of needle biopsy specimens for histopathological diagnosis of superficial soft-tissues neoplasms.15-18

In conclusion, all seven cases of mandibular PNET initially presented with a gradually growing painless facial swelling and were misdiagnosed as infectious disease. The radiographic features of mandibular PNETs on CT and MRI are summarised. Although intratumoral haemorrhage, necrosis and calcification are usually seen in other peripheral PNETs, they are not found in the peripheral PNETs arising in the mandible. Sonographically, the mandibular PNETs appear as well-defined heterogeneous hypoechoic masses, and they can be accurately diagnosed based on the ultrasonography-guided percutaneous core needle biopsy. These image findings and procedures of mandibular PNET can alert the physicians to this rare maxillofacial tumour and facilitate precise diagnosis and proper treatment strategies.

References

- 1.Stout AP. A tumor of the ulnar nerve. Proc NY Pathol Soc 1918;12:2–12 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khong PL, Chan GC, Shek TW, Tam PK, Chan FL. Imaging of peripheral PNET: common and uncommon locations. Clin Radiol 2002;57:272–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kushner BH, Hajdu SI, Gulati SC, Erlandson RA, Exelby PR, Lieberman PH. Extracranial primitive neuroectodermal tumors. The Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience. Cancer 1991;67:1825–1829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmidt D, Herrmann C, Jurgens H, Harms D. Malignant peripheral neuroectodermal tumor and its necessary distinction from Ewing's sarcoma. A report from the Kiel Pediatric Tumor Registry. Cancer 1991;68:2251–2259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parham DM, Hijazi Y, Steinberg SM, Meyer WH, Horowitz M, Tzen CY, et al. Neuroectodermal differentiation in Ewing's sarcoma family of tumors does not predict tumor behavior. Hum Pathol 1999;30:911–918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimber C, Michalski A, Spitz L, Pierro A. Primitive neuroectodermal tumours: anatomic location, extent of surgery, and outcome. J Pediatr Surg 1998;33:39–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dick EA, McHugh K, Kimber C, Michalski A. Imaging of non-central nervous system primitive neuroectodermal tumours: diagnostic features and correlation with outcome. Clin Radiol 2001;56:206–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim MS, Kim B, Park CS, Song SY, Lee EJ, Park NH, et al. Radiologic findings of peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor arising in the retroperitoneum. Am J Roentgenol 2006;186:1125–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozer E, Kanlikama M, Karakurum G, Sirikci A, Erkilic S, Aydin A. Primitive neuroectodermal tumour of the mandible. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2002;65:257–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sundine MJ, Bumpous JM. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the mandible: Report of a rare case. Ear Nose Throat J 2003;82:211–214 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alrawi SJ, Tan D, Sullivan M, Winston J, Laree T, Hicks W, et al. Peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the mandible with cytogenetic and molecular biology aberrations. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005;63:1216–1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Votta TJ, Fantuzzo JJ, Boyd BC. Peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor associated with the anterior mandible: A case report and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2005;100:592–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanaya H, Hirabayashi H, Tanigaito Y, Baba K. Ewing's sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumour of the mandible: report of a rare case and review of the literature. J Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg 2007;36:E15–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anonymous Primary peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor of mandible. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2008;30:258–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yeow KM, Tan CF, Chen JS, Hsueh C. Diagnostic sensitivity of ultrasound-guided needle biopsy in soft tissue masses about superficial bone lesions. J Ultrasound Med 2000;19:849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torriani M, Etchebehere M, Amstalden E. Sonographically guided core needle biopsy of bone and soft tissue tumors. J Ultrasound Med 2002;21:275–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soudack M, Nachtigal A, Vladovski E, Brook O, Gaitini D. Sonographically guided percutaneous needle biopsy of soft tissue masses with histopathologic correlation. J Ultrasound Med 2006;25:1271–1277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ray-Coquard I, Ranche're-Vince D, Thiesse P, Ghesquières H, Biron P, Sunyach MP, et al. Evaluation of core needle biopsy as a substitute to open biopsy in the diagnosis of soft-tissue masses. Eur J Cancer 2003;39:2021–2025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]