Abstract

Background:

The objective was to determine the prevalence of ectoparasite infestations in referred companion dogs to veterinary hospital of Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, from 2009 to 2010.

Methods:

A total of 126 dogs were sampled for ectoparasites and examined by parasitological methods. The studied animals were grouped based on the age (<1 year, 1–3 years and >3 years), sex, breed and region

Results:

Thirty six out of 126 referred dogs (28.57%) were positive for external ectoparasites. The most common ectoparasites were Heterodoxus spinigera, which were recorded on 11 dogs (8.73%). Rhipicephalus sanguineus, Sarcoptes scabiei, Otodectes cynotis, Xenopsylla cheopis, Cetenocephalides canis, Cetenocephalides felis, Hippobosca sp. and myiasis (L3 of Lucilia sp.) were identified on 9 (7.14%), 7 (5.56%), 6 (4.76%), 3 (2.38%), 3 (2.38%), 2 (1.59%), 2 (1.59%) and one (0.79%) of the studied dogs respectively. Mixed infestation with two species of ectoparasites was recorded on 8 (6.35%). Prevalence was higher in male dogs (35.82%; 24 out of 67) than females (20.34%; 12 out of 59), age above 3 years (31.81%; 7 out of 22) and in the season of winter (30.95%; 13 out of 42), but the difference was not significant regarding to host gender, age and season (P> 0.05).

Conclusion:

Apparently this is the first study conducted in companion dogs of Ahvaz District, South-west of Iran. Our results indicated that lice and ticks were the most common ectoparasites in dogs of this area. The zoonotic nature of some ectoparasites can be regard as a public health alert.

Keywords: Dogs, Ectoparasite, Infestation, Prevalence, Iran

Introduction

Ectoparasites are a common and important cause of skin diseases in dogs and cats. They have a worldwide distribution and are capable of disease transmission. Ectoparasites cause life-threatening anemia and occasionally hypersensitivity disorders in young and debilitated animals (Araujo et al. 1998). Some ectoparasites of pet animals, notably fleas, can infest humans and may lead to the development of dermatitis and transmit vector-borne diseases (Scott et al. 2001). Human infestation with Otodectes cynotis (Hering, 1838) has also been reported (Hewitt et al. 1971). Ticks, after mosquitoes, are the second most important arthropods that may transmit pathogens like viruses (Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, Colorado tick fever and tick-borne encephalitis), bacteria including rickettsiae (Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Tularemia, Q fever, Ehrlichiosis and Lyme diseases), protozoa (Babesiosis) and filarial nematodes (Onchocerciasis) to other animals and humans. Cases of human parasitism (such as Astrakhan fever) have been reported by Rhipicephalus sanguineus from southeastern Europe too, i.e., from Bosnia and Greece (Fournier et al. 2003, Chaligiannis et al. 2009). Ticks also cause paralysis, the condition caused by toxins found in the saliva of ticks (Xhaxhiu et al. 2009). Canine demodiciosis caused by Demodex canis is considered to be a part of the normal fauna of the canine skin and is present in small number of most healthy dogs. Diagnostic procedures, such as trichography or skin biopsy may be required to obtain an accurate estimation of the mite infestation (Scott et al. 2001). Sarcoptic mange is a highly contagious non-seasonal and pruritic skin condition caused by infestation with Sarcoptes scabiei var. canis, a burrowing mite, which is transmitted by direct contact between dogs. Otoacariosis, caused by O. cynotis, is characterized by irritation, rubbing, ear twitching, scratching and head shaking particular in cats. Other parasites such as Trichodectes canis are highly host specific, but they can act as an intermediate host for the tapeworm Dipylidium caninum that may affect humans, especially children (Scott et al. 2001). Because older animals may acquire immunity, puppies appear to be most susceptible to O. cynotis (Curtis 2004). Various studies have found that Ctenocephalides felis, C. canis and Pulex irritans, are the 3 most common flea species on dogs. Different species of ticks and fleas may infest dogs and cats in different geographical regions. C. felis was the most prevalent species in London (Beresford-Jones 1981), Egypt (Amin 1966), and Denmark (Kristensen et al. 1978), while C. canis was the dominant species in dogs in rural parts of the United Kingdom (Chesney 1995), Dublin (Baker and Hatch 1972), and Australia (Coman et al. 1981). Pulex irritans was the prevalent species in dogs of the southern part of USA (Kalkofen and Greenberg 1974), and this species was also commonly found in dogs in Hawaii (Haas and Wilson 1967).

Methods of deep and superficial skin scraping, acetate tape preparation, combing the entire body surfaces, otic swabs and clinical trials are usually used for the detection of ectoparasites (Scott et al. 2001). In urban or suburban areas, people traditionally raise dogs as pets. Health check-ups protect pets from infestation by ectoparasites. Thus, knowledge of types of species, density and prevalence of ectoparasites is needed to effectively control them (Scott et al. 2001, Nuchjangreed and Somprasong 2007). Scarce information is available on the parasites of dogs from Iran. C. canis was reported as the most common ectoparasite in Shiraz, Southern Iran (Jafari Shoorijeh et al. 2008).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report examining the prevalence of various ectoparasites infesting companion dogs in Ahvaz District, South-west of Iran. We conducted this study in order to determine the prevalence of ectoparasite infestations in companion dogs of this area.

Materials and Methods

In the present investigation, ectoparasites were collected from 126 companion dogs (53 Terriers, 42 mixed breed, 11 German shepherd, 5 Spitz, 5 Pekingense, 4 Great Dane, 3 Doberman Pinscher, 2 Lahasa apso and one Shitzu) with age range 2 months– 8 years. They were referred to Veterinary Hospital of Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz District, in southwestern Iran. This area is located at an elevation of 12 meters above sea level and the climate is warm-humid. Weather parameters were obtained of weather bureau of Khuzestan Province. The studied animals were divided into three groups based on the age (<1 year, 1–3 years and >3 years). Classification was made by sex, breed and region also. Most of the studied dogs were referred for a healthy check up and vaccination. Age was estimated by dental formulary and owner information’s.

The dogs were examined for ectoparasite infestation by a complete examination of the skin, clinical trials, skin scraping, acetate tape preparation, otic swabs, and combing of the whole body with a stainless steel fine-toothed comb (Zakson et al. 1995). The skins of all dogs were palpated and visually inspected thoroughly for the presence of ticks. All ticks were manually removed carefully to ensure that the mouthparts remained intact and collected together with any fleas and lice in the comb. The ticks and lice removed from the animals were stored in 70% ethanol. All dogs were assessed for fleas by combing for 5 minute exactly (Zakson et al. 1995). The combing samples were collected in 70% ethanol also. All fleas were counted at 40× and identified at 400× microscopically. Bilateral otoscopic examination was carried out for clinical signs of erythema, inflammation, excess debris or exudates. The visual presence of mite movement or black ceruminous exudates was indicative of O. cynotis.

Deep ear swab specimens were obtained from both ears from all dogs. All ear swab specimens were examined microscopically (at 40× for detection and 400× for species identification) within 24 h with mineral oil for the presence of mites. Deep and superficial skin scraping was performed with mineral oil in suspected dogs to mites. Skin scrapings and ear swabs were placed in 10% potassium hydroxide and gently heated to scales, crusts and hair or aural material. Thereafter, the material was centrifuged, and the sediment was microscopically examined for mites. A 2 × 2 inch section of hair was clipped from the ventral abdomen on each dog. The clipped hair was collected in 70% ethanol. All hair samples were thoroughly examined with aid of microscope for the presence of nits, lice, mites, fleas and other arthropods. The specimens were mounted on a glass slide with mineral oil preparation. Each slide was completely and carefully examined microscopically for superficial ectoparasites. Finally all arthropods were identified microscopically at 40× to species using the diagnostic keys (Anon 1966, Estrada-Pena et al. 2007).

The study was approved by Ethic Committee by Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz.

Statistics analysis

Dogs were grouped by age, sex, breed and season to determine whether these factors were associated with ectoparasite infestation, using chi-square analysis and Fisher’s exact test. Statistical comparisons were carried out using SPSS 16.0 statistical software. Differences were considered significant at P< 0.05 level.

Results

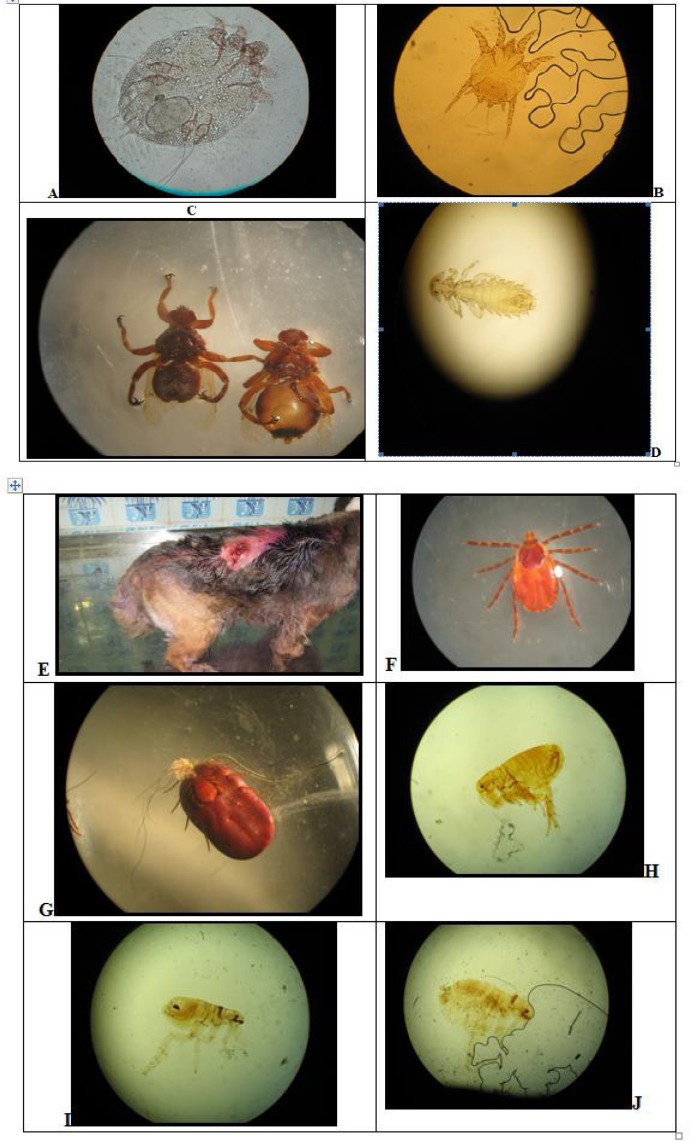

A total of 126 companion dogs were randomly selected from approximately 550 dogs referred during the four time periods. Samples were collected from 25, 32, 27 and 42 dogs in spring, summer, autumn and winter seasons respectively. Thirty six out of 126 referred dogs (28.57%) were positive for external ectoparasites. The most common ectoparasites were lice and ticks followed by mites and fleas. Heterodoxus spinigera, Rhipicephalus sanguineus, Sarcoptes scabiei, Otodectes cynotis, Xenopsylla cheopis, Cetenocephalides canis, C. felis, Hippobosca sp. and myiasis (L3 of fly Lucilia sp.) were identified on 11 (8.73%), 9 (7.14%), 7 (5.56%), 6 (4.76%), 3 (2.38%), 3 (2.38%), 2 (1.59%), 2 (1.59%) and one (0.79%) of the studied dogs respectively (Fig. 1”A-J”). Mixed infestation with two species of ectoparasites was recorded on 6.35% (8 out of 126) of the dogs. R. sanguineus plus O. cynotis infestation were the most common combination (Table 1). Most of infestations were in mixed breeds (45.23%, 19 out of 42) and terriers (16.98%, 9 out of 53). Prevalence was higher in male dogs (35.82%, 24 out of 67) than females (20.33%; 12 out of 59), age above 3 years (31.81%, 7 out of 22) (Table 2) and in the season of winter (30.95%, 13 out of 42) (Table 3), but the difference was not significant relative to host gender, age, breed and season (P> 0.05). Heterodoxus spinigera lice were recorded on 1, 9 and 1 of the dogs examined in seasons of autumn, winter and spring respectively, but they were absent in summer. Otoscopic examination of both ears revealed mite movement and black ceruminous exudates. They were typically indicative of the presence of O. cynotis in (4.76%, 6 out of 126) dogs. The affected dogs to S. scabies had the typical signs of mange mite infestation, such as pruritis, papules, and alopecia. The average temperature for spring–winter was 29.83, 37.26, 23.2, and 17.86° C, respectively. The average relative humidity for spring–winter was 31.0, 23.66, 52 and 61.66% as well.

Fig. 1.

The original pictures of ectoparasites found in companion dogs of Ahvaz District including (A) S. scabies, (B) O. cynotis, (C) Hyppobosca sp., (D) H. spiniger, (E) The affected dog to myiasis (L3 of fly Lucilia sp.), (F) R. sanguinus (female), (G) R. sanguinus (male and female), (H) X. cheopis, (I) C. felis, (J) C. canis. The pictures were taken by a digital camera in the Parasitology Lab of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz.

Table 1.

Occurrence of mixed ectoparasite infestations in companion dogs in Ahvaz district, South-west of Iran, 2009–2010 (n=126)

| Mixed-species ectoparasite infestation (Two species) | Number (Prevalence %) |

|---|---|

| Ctenocephalides felis + Heterodoxus spinigera | 1 (0.79) |

| Xenopsylla cheopis + Heterodoxus spinigera | 1 (0.79) |

| Rhipicephalus sanguineus + Otodectes cynotis | 3 (2.38) |

| Heterodoxus spinigera + Sarcoptes scabiei | 1 (0.79) |

| Ctenocephalides canis + Hippobosca sp. | 2 (1.59) |

| Total | 8 (6.35) |

Table 2.

Number of ectoparasite infestations in companion dogs based on different ages in Ahvaz district, South-west of Iran, 2009–2010

|

Season

|

Age<1 years | Age 1–3 years | Age >3 years | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | ||||

| H. spinigera | 9 | 2 | 0 | 11 |

| R. sanguineus | 3 | 3 | 3 | 9 |

| S. scabiei | 5 | 2 | 0 | 7 |

| O. cynotis | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| X. cheopis | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| C. canis | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| C. felis | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Hippobosca | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Myiasis | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 26 | 8 | 10 | 44 |

Table 3.

Number of ectoparasite infestations in companion dogs based on different seasons in Ahvaz district, South-west of Iran, 2009–2010

|

Season

|

Autumn | Winter | Spring | Summer | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | |||||

| H. spinigera | 1 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 11 |

| R. sanguineus | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| S. scabiei | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 7 |

| O. cynotis | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 6 |

| X. cheopis | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| C. canis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| C. felis | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Hippobosca | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Myiasis | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 8 | 15 | 11 | 10 | 44 |

Discussion

The present study is the first reach on the prevalence of infestations in companion dogs in Ahvaz District. It was revealed that 28.57% of the dogs were infested to ectoparasites. These results indicate that ectoparasites are relatively common in companion dogs of this area, as many parts of the world. According to our study, H. spinigera (8.73%) and R. sanguineus (7.14%) were the most abundant ectoparasites, followed by mites and fleas.

The canine sarcoptic mange and the ear mite (O. cycotis) can infest humans and cause pruritic skin lesions (Hewitt et al. 1971). Fleas not only act as intermediate hosts of tapeworms but also directly infest human. Humans, if parasitized, may be exposed to babesiosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, ehrlichiosis, borreliosis or tick paralysis (Scott et al. 2001). Several reports (Anvar et al. 1972, Jafari Shoorijeh et al. 2008,) have documented ectoparasite infestations among dogs in Iran. Ctenocephalides canis and C. felis have been reported on various host species from different parts of Iran, but their prevalence was not noted (Anvar et al. 1972). In research of Jafari Shoorijeh, the most common ectoparasite was C. canis, which infested 22 of the 160 dogs. In their study, Pulex irritans was identified on 2 of the dogs and 142 R. sanguineus ticks were found on 13 dogs. Trichodectes canis was observed on 2 dogs and 8 dogs had Hippobosca flies, which were seen mostly in spring. All superficial skin scrapes for mite detection were negative (Jafari Shoorijeh et al. 2008). The ticks feed on a wide range of hosts; however, all stages of R. sanguineus are primarily associated with dogs (Dantas-Torres 2008). Lice are reportedly the most common ectoparasites on dogs of the northern hemisphere (Christensson et al. 1998). Heterodoxus spiniger was found on 11 of 126 dogs infested with ectoparasites in our study. It is a major ectoparasite of the dog population in Ahvaz District.

In several studies, D. canis has been reported as the most frequent infestation (Nayak et al. 1997), but the current study was not consistent with previous studies. These differences can not be easily explained, but it may be attributed to epidemiological factors, such as weather, seasonal variations, geographical location, intrinsic resistance, and particularly the age of the animals examined (Nayak et al. 1997). Studies from various parts of the world have indicated that C. felis, C. canis, and P. irritans are the most commonly occurring flea species in dogs. It is reported that C. canis is the dominant species in Dublin, regions of England and Australia (Linardi et al. 1973, Zygner et al. 2006). However, Harman et al. (1987) reported that C. canis was not identified among the dogs examined for fleas in Florida.

The greatest prevalence infestation of ectoparasites belonged to fleas which followed by ticks, 89% and 30% infestations, respectively (Estares et al. 1999).

In our study, the most common ectoparasites were lice and ticks followed by mites and fleas. Although utilization of an otoscope or cotton-tipped swab for the diagnosis of ear mite and examination of vellus hair for the sarcoptic mange might have increased the detection rates of those mites, but only the skin scraping technique is definitive for diagnosis (Foreyt 2001).

A comparative study of ectoparasite infestation of different breeds of dogs was performed in four veterinary clinics in Nigeria. Of a total of 820 dogs examined, 30.0% were infected by ticks, 27.6% by lice, 25.8% by fleas and 13.3% by mites. The species of ectoparasites identified and their prevalence rates were: R. sanguineus (19.5%), O. megnini (10.5%), C. canis (25.8%), Demodex canis (13.3%) (Ugochukwu et al. 1985). A total of 344 dogs belonging to people in North West Province, South Africa, were examined for ectoparasites, accordingly the dogs harbored 14,724 ixodid ticks belonging to 6 species, 1,028 fleas belonging to 2 species, and 26 lice. Pure infestations of H. leachi were present in 14 dogs and R. sanguineus in 172 dogs (Bryson et al. 2000). In western Romania, the most common flea in dogs was C. felis, followed by C. canis and P. irritans (Morariu et al. 2006). Hippobosca flies were found on 2 of 126 (1.59%) dogs infested with ectoparasites in our study. In Kabul, Afghanistan, 25 of 105 dogs had Hippobosca capensis (Le Riche et al. 1988). It is stated that dogs less than 1 year old are more susceptible to ectoparasite infestations (Kwochka 1987, Nayak et al. 1997, Chee et al. 2008). In contrast, in the present study, the higher prevalence was seen in the dogs of above 3 years old, compared with younger 3 years old. Because older animals may acquire immunity, puppies appear to be most susceptible to ectoparasites; of course the difference was not significant. In the present survey, we found that the prevalence of ectoparasites was more frequent in male dogs (35.82%) than females (20.33%) without significant difference. This is agree to the results of other researchers (Nayak et al. 1997, Rodriguez-Vivas et al. 2003), who suggested that both sexes are susceptible to the infestation of ectoparasites.

Mean (±SD) of temperature and relative humidity of Ahvaz District were noted during the collection period in our study. Among the 36 ectoparasite positive dogs, the highest involvement was recorded in winter season (30.95%), but the difference was not significant. Dipeolu (1975) reported that the highest number of parasites occurred in summer in Nigeria, whereas Alcaino et al. (1999) established that they are predominant in spring in Chile, showing a distinct decrease since the beginning of summer, until completely disappearing in autumn. For C. canis, Horak (1982) considered that the most favorable months for adults are summer-autumn, maybe due to the higher temperature and humidity, whereas the most unfavorable period is that from winter-spring, due to low temperature and humidity. To prevent the possibility of continued transmission of ectoparasites from pet animals, practicing veterinarians should advice pet owners to pay attention to and be aware of ectoparasites of zoonotic importance.

To the best of our knowledge this is the first study conducted in Ahvaz District, South-West of Iran that examined the prevalence of ectoparasites in companion dogs population, however, this survey was limited to the Ahvaz area and additional studies are required to complement these findings and help veterinarians prepare a complete program for the control of these parasite populations and their associated diseases.

Acknowledgments

We would like to mention the greatly appreciation of Research Council of Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz for the financial support (8979702). The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

References

- Amin OM. The fleas (Siphonaptera) of Egypt: distribution and seasonal dynamics of fleas infesting dogs in the Nile valley and delta. J Med Entomol. 1966;3(3):293–298. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/3.3-4.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymus . Pictorial Key to Arthropods, Reptiles, Birds and Mammals of Public Health Significance. Centers for Disease Control, United States Health Education and Welfare; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Anvar M, Eslami A, Mirza Yans A, Rak H. List of Endoparasites and Ectoparasites of Domesticated Animals of Iran. Tehran University Press; Tehran, Iran: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Araujo FR, Silva MP, Lopes AA, Ribeiro OC, Pires PP, Carvalho CM, Balbuena CB, Villas AA, Ramos JK. Severe cat flea infestation of dairy calves in Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 1998;80(1):83–86. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(98)00181-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker KP, Hatch C. The species of flea found on Dublin dogs. Vet Rec. 1972;91(6):151–152. doi: 10.1136/vr.91.6.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beresford-Jones WP. Prevalence of fleas on dogs and cats in an area of central London. J Small Anim Pract. 1981;22(1):27–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.1981.tb01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryson NR, Horak IG, Hohn EW, Louw JP. Ectoparasites of dogs belonging to people in resource-poor communities in North West Province, South Africa. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 2000;71(3):175–179. doi: 10.4102/jsava.v71i3.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaligiannis I, Sotiraki S, Xanthopoulou K, Papa A. Ticks parasitizing humans in North-east Greece; 7th Ann Meet Eur Vet Parasitol Coll and 10h Bienn Symp. Ectoparasites in Pets (ISEP); Toulouse, France. 2009. p. 76. Proc. [Google Scholar]

- Chee JH, Kwon JK, Cho HS, Cho KO, Lee YJ, Abd El-Aty AM, Shin SS. A survey of ectoparasite infestations in stray dogs of Gwang-ju City, Republic of Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2008;46(1):23–27. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2008.46.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney CJ. Species of flea found on cats and dogs in south west England: further evidence of their polyxenous state and implications for flea control. Vet Rec. 1995;136(14):356–358. doi: 10.1136/vr.136.14.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensson D, Zakrisson G, Holm B, Gunnarsson L. Prevalence of lice found on dogs in Sweden. Svensk Vet Tidn. 1998;50:189–191. [Google Scholar]

- Coman BJ, Jones EH, Driesen MA. Helminth parasites and arthropods of feral cats. Aust Vet J. 1981;57(7):324–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1981.tb05837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis CF. Current trends in the treatment of Sarcoptes, Cheyletiella and Otodectes mite infestation in dogs and cats. Vet Dermatol. 2004;15(2):108–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3164.2004.00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantas-Torres F. The brown dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Latreille, 1806) (Acari: Ixodidae): from taxonomy to control. Vet Parasitol. 2008;152(3–4):173–185. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dipeolu OO. A survey of the ectoparasitic infestations of dogs in Nigeria. J Small Anim Pract. 1975;16(1–12):123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Estares L, Chavez A, Casas E. Prevalence of ectoparasites of Canis familiaris in the two districts of San Juan de Lurigancho, San Martin de Porres, Comas and independence of Lima. Rev Inv Vet Peru. 1999;10(2):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Estrada-Pena A, Venzal JM. Climate Niches of Tick Species in the Mediterranean Region: Modeling of Occurrence Data, Distributional Constraints, and Impact of Climate Change. J Med Entomol. 2007;44(6):1130–1138. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2007)44[1130:cnotsi]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foreyt WJ. Veterinary Parasitology Reference Manual. 5th ed. Iowa State Press Ames; Iowa, USA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier PE, Durand JP, Rolain JM, Camicas JL, Tolou H, Raoult D. Detection of Astrakhan fever rickettsia from ticks in Kosovo. Ann New York Acad Sci. 2003;990:158–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas GE, Wilson N. Pulex simulans and P. irritans on dogs in Hawaii (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae) J Med Entomol. 1967;4(1):25–30. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/4.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman DW, Halliwell RE, Greiner EC. Flea species from dogs and cats in north-central Florida. Vet Parasitol. 1987;23(1–2):135–140. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(87)90031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt M, Walton GS, Waterhouse M. Pet animal infestations and human skin lesions. Br J Dermatol. 1971;85(3):215–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1971.tb07219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horak IG. Parasites of domestic and wild animals in south Africa. XIV. The seasonal prevalence of Rhipicephalus sanguineus and Ctenocephalides spp. On kenneled dogs in Pretoria north. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 1982;49(1):63–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari Shoorijeh S, Rowshan Ghasrodashti A, Tamadoni A, Moghaddar N, Behzadi MA. Seasonal Frequency of Ectoparasite Infestation in Dogs from Shiraz, Southern Iran. Turk J Vet Anim Sci. 2008;32(4):309–313. [Google Scholar]

- Kalkofen UP, Greenberg J. Public health implications of Pulex irritans infestations of dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1974;165(10):903–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen S, Haarlov N, Mourier H. A study of skin diseases in dogs and cats. Patterns of flea infestation in dogs and cats in Denmark. Nord Vet Med. 1978;30(10):401–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwochka KW. Mites and related disease. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 1987;17(6):1263–1284. doi: 10.1016/s0195-5616(87)50002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Riche PD, Soe AK, Alemzada Q, Sharifi L. Parasites of dogs in Kabul, Afghanistan. Br Vet J. 1988;144(4):370–373. doi: 10.1016/0007-1935(88)90067-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linardi PM, Nagem RL. Pulicidae and other ectoparasites on dogs of Belo Horizonte and neighbouring municipalities. Rev Bras Biol. 1973;33(4):529–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morariu S, Darabus G, Oprescu I, Mederle N, Moraru EG, Morariu F. Etiology of flea infestation in dogs and cats from three counties of Romania. Rev Sci Parasitol. 2006;6:67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Nayak DC, Tripathy SB, Dey PC, Ray SK, Mohanty DN, Parida GS, Biswal S, Das M. Prevalence of canine demodicosis in Orissa (India) Vet Parasitol. 1997;73(3–4):347–352. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(97)00125-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuchjangreed C, Somprasong W. Ectoparasite species found on domestic dogs from Pattaya district, Chon Buriprovince, Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Publ Health. 2007;38(1):203–207. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Vivas RI, Ortega-Pacheco A, Rosado-Aguilar JA, Bolio GM. Factors affecting the prevalence of mange-mite infestations in stray dogs of Yucatan, Mexico. Vet Parasitol. 2003;115(1):61–65. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(03)00189-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott DW, Miller WH, Griffin CE. Muller and Kirk’s Small Animal Dermatology. 6th ed. WB Saunders; Philadelphia, USA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ugochukwu EI, Nnadozie CC. Ectoparasitic infestation of dogs in Bendel State, Nigeria. Int J Zoonoses. 1985;12(4):308–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xhaxhiu D, Kusi I, Rapti D, Visser M, Knaus M, Lindner T, Rehbein S. Ectoparasites of dogs and cats in Albania. Parasitol Res. 2009;105(6):1577–1587. doi: 10.1007/s00436-009-1591-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakson M, Gregory LM, Endris RG, Shoop WL. Effect of combing time on cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis) recovery from dogs. Vet Parasitol. 1995;60(1–2):149–153. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(94)00765-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zygner W, Wedrychowicz H. Occurrence of hard ticks in dogs from Warsaw area. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2006;13(2):355–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]