Ancora imparo: I am still learning, the 88-year-old Michelangelo scribbled on the margin of a sketchbook as he was working on his last unfinished masterpiece, the Pietà Rondanini (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Michelangelo Buonarroti. Pietà Rondanini (1564). Castello Sforzesco. Milano, Italy.

If one considers how human accomplishments are attained, it must be acknowledged that a lifetime of wholehearted dedication is necessary to achieve significant results. This is true for an architect to design an outstanding structure, for an artist to create a meaningful piece of art, or for a surgeon to perform complex surgical procedures. Surgeons must continually improve their execution while keeping pace with unremitting scientific and technological developments.

Michelangelo himself, reflecting on his life's accomplishments, wrote: “If people knew how hard I worked to gain my mastery, it would not seem so wonderful at all.”

Another thing to consider is that natural talent, dedication, and self-teaching are not sufficient to carry one to the height of mastery: fundamental to an individual's progress is the relationship with the mentor and the influence of the school.

Ernest Rutherford, the scientist who clarified the structure of the atom, wrote that science goes step by step and that every man depends on the work of his predecessors; it is this mutual influence that provides the enormous possibility of scientific advance. Scientists are not dependent on the ideas of a single person, but on the combined wisdom of thousands.

This combined wisdom, collectively accumulated and continuously enriched and refined over the years, is the intellectual heritage that, through the actions of its members in their roles as mentors, is handed down to new generations.

As pointed out by Professor Erino Rendina of the University of Rome, in his presidential address at the 23rd Annual Meeting of the European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgery,1 the figure of the mentor is fundamental: the mentor is the driving force behind the disciple's learning process and behind his or her gradual assumption of responsibilities. The mentor's knowledge and wisdom, personality, human qualities, and—of the greatest importance—his example, influence the student profoundly and forever.

The importance, in the formation of a surgeon, of belonging to an authoritative school was underlined during the 16th International Symposium of the Denton A. Cooley Cardiovascular Surgical Society that took place in Galveston, Texas, in June 2009 and was appropriately titled: “Surgical Mentors: Trusted Teachers.”

This paper's primary objective is to express the concept that, in all fields of art and science, individuals are deeply indebted to their mentors. It underscores the importance of belonging to an authoritative school, which acts as a repository of collected knowledge that is handed over to new generations.

The Mentor in Schools of Surgery

The introduction of anesthesia and antisepsis in the second half of the 19th century rapidly heralded great progress in all fields of surgery. During that fruitful period, new instruments were developed and new procedures were introduced, some of which are still in use today.

A number of surgical schools were established, highly respected for their innovative techniques and excellent results. These schools were generally identified by the name of the master surgeon who founded and developed them and by the city in which they were originally based. Belonging to these schools signified membership in a scientific and professional aristocracy. As the students raised through a school acquired seniority and responsibility, then became heads of surgical departments in their own right, an illustration of the branching out of the various schools could be likened to a family tree.

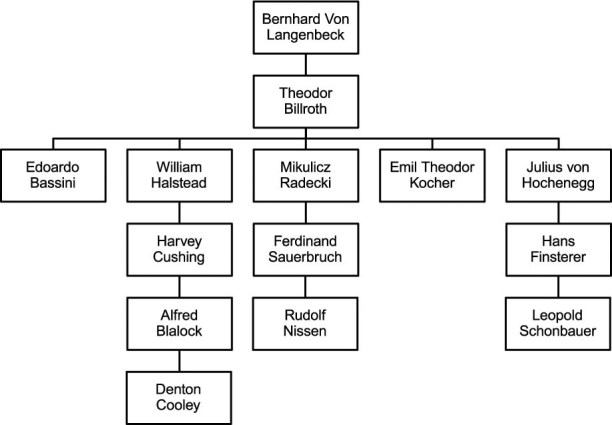

One of the most illustrious examples of these schools was the one founded and headed by Theodor Billroth of the University of Vienna, who conceived and applied surgical procedures that are still in use today. Among his disciples were the Italian Edoardo Bassini, the Polish German Jan Mikulicz-Radecki, the Swiss Theodor Kocher, the Austrian Julius von Hochenegg, and the American William Halsted, all of whom went on to become master surgeons and heads of surgical schools that consolidated and expanded the cultural heritage of the Viennese school (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Family tree of the Viennese school of surgery. Note how Theodor Billroth has influenced successive generations of surgeons to this day.

Of special interest is William Halsted, whose teachings and legacy deeply influenced the American surgical world. It is interesting to note that his influence, through Henry Cushing and Alfred Blalock, reached Denton Cooley; thus all of us who have been his students are linked, albeit remotely, to the surgical science of Theodor Billroth.

The Mentor in Schools of Art

As pointed out by Prof. Rendina,1 life and profession are intimately bound in the art of painting, as in the craft of surgery. The very life and learning of a surgical resident in a teaching hospital closely resemble those of a young apprentice in a Renaissance workshop (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Philip Galle. A Painter's Workshop (1593–98). The master painter (center) is working on the large picture. On the left, the “senior associate” is painting a portrait. The younger students are performing other tasks: drawing in a sketchbook, mixing colors, and preparing the palette.

Not unlike the surgical resident who spends years in the hospital learning the various aspects of the science and art of surgery, successively climbing the steps of increased responsibility, the apprentice lived in the workshop for years, in close contact with the mentor— absorbing day by day, year after year, the master's art.

The apprentice of a master painter would first make the paintbrush, then prepare and mix the colors for the palette, then paint a minor detail of a painting in which the master painted the main figures, until he reached the privilege of painting his own picture. This progression is similar to that of a surgeon who, after a number of years of training, finally reaches the professional independence that allows him to perform surgery on his own patients.

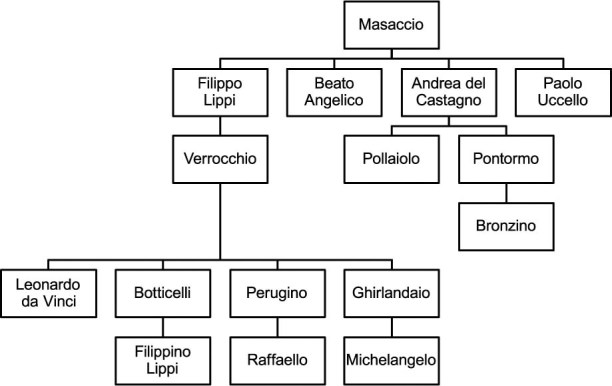

An interesting example that sheds light on the inner workings of a Renaissance workshop is to be found in Giorgio Vasari's work Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550), which recounts the story behind the painting The Baptism of Christ, by Andrea del Verrocchio, a highly esteemed Florentine master. In his renowned workshop, Verrocchio had a series of truly exceptional students, among them Leonardo, Botticelli, Perugino, and Ghirlandaio (Fig. 4)

Fig. 4 Family tree of some of the major Renaissance artists. Verrocchio had a series of exceptional students, among whom were Leonardo, Botticelli, Perugino, and Ghirlandaio. These, in turn, became the mentors of such personalities as Raphael and Michelangelo.

The master painted the main figures of Christ and of John the Baptist (Fig. 5), and he delegated the painting of the background and of the 2 angels on the bottom left side of the picture to his students. Botticelli painted the angel on the right, and Leonardo painted both the angel kneeling on the left and the background, which is reminiscent of the background of his Mona Lisa. Verrocchio immediately recognized the superiority of his students and resolved never to touch a paintbrush again: he dedicated himself to sculpture instead, an art form in which he felt that he had no rivals.

Fig. 5 Andrea Verrocchio. The Baptism of Christ (1475–78). The main figures were painted by his own hand. The angel on the right was painted by Botticelli. The background and the angel on the left were painted by Leonardo da Vinci.

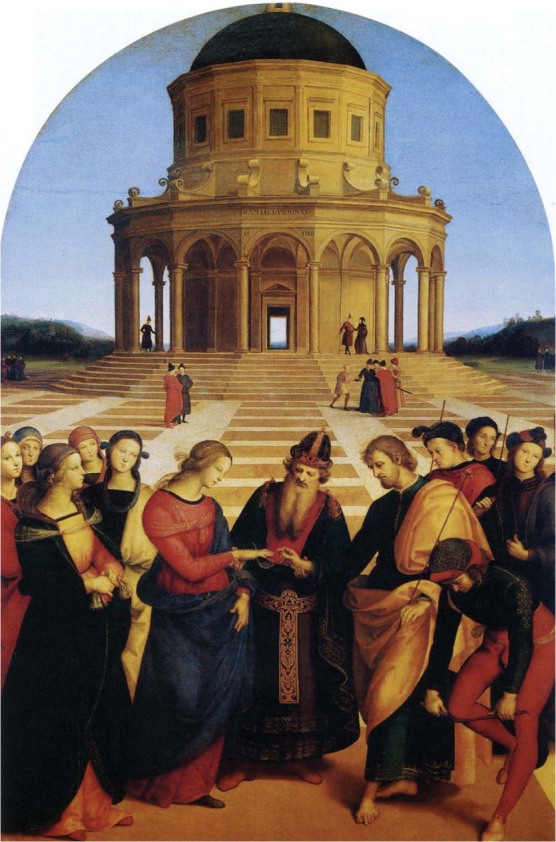

As is true of the schools of surgery, a family tree can be constructed for the schools of art, which shows how the students of Verrocchio later became the mentors of such personalities as Raphael and Michelangelo (Fig. 4). The relationship between mentor and disciple can be clearly demonstrated by comparing 2 paintings depicting the same subject: the marriage of the Virgin, painted, respectively, by the master Perugino and by the student Raphael (Figs. 6 and 7).

Fig. 6 Pietro Perugino. The Marriage of the Virgin (1501–4).

Fig. 7 Raffaello Sanzio. The Marriage of the Virgin (1504).

The similarities between the 2 paintings are striking: the scene is set in front of a neoclassical building and painted in accordance with the recently developed laws of perspective. The groups of people attending the wedding are very similar both in their stance and in their clothes. In Raphael's painting, the central figures, including Mary and Joseph, are almost a replica of the older painting. It is evident that Raphael, who since the age of 15 had worked in Perugino's workshop as an apprentice, created an in-depth study of his mentor's work.

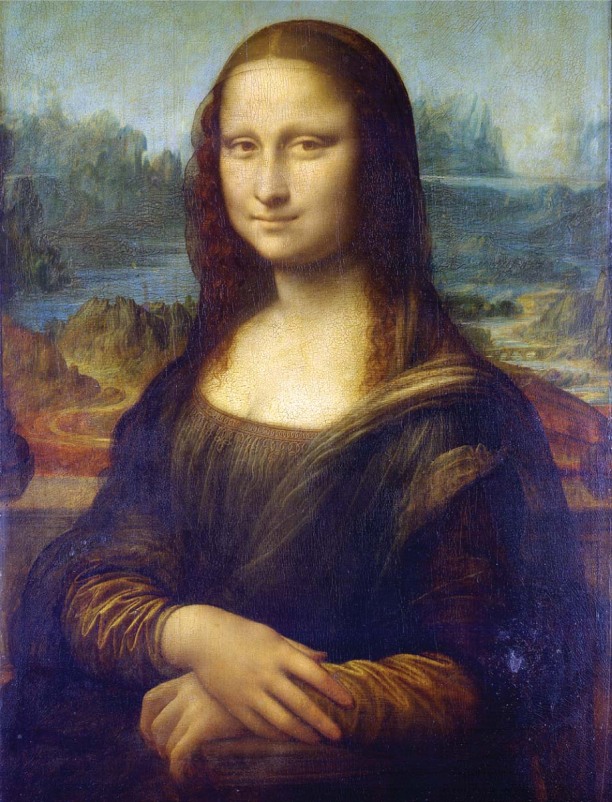

Another example of the ways in which the master influenced the student is demonstrated by a recent restoration of a long-overlooked painting in the Prado in Madrid (Fig. 8). At first it was thought that this painting was one of the many existing copies of the famous original by Leonardo. But, when scholars analyzed this painting using modern technology and compared it with the original Mona Lisa (Fig. 9), they came upon a startling discovery: for each change that Leonardo made, the other painting revealed a corresponding and identical change. This could lead only to the conclusion that the 2 pictures were painted simultaneously and that the student, probably Andrea Salaino, was learning first hand from Leonardo.

Fig. 8 The “new” Mona Lisa (date unknown) of the Prado in Madrid.

Fig. 9 The original Mona Lisa (1503–14) by Leonardo da Vinci. Louvre, Paris.

Learn from the Masters, Modify, Apply

As in ancient times, pupils travel long distances in order to observe the work of different masters and to update themselves on new and different techniques.

Houston provides an example: for many years, surgeons from all over the world crowded the operating rooms of the hospitals there, just to catch a glimpse of the innovative surgery performed by master surgeons.

Notably, there are examples dating back hundreds of years of young painters who traveled long distances in order to study the work of eminent masters who applied new techniques and found new subjects for their paintings. The influence exerted by the great Flemish painter Jan Van Eyck on Antonello da Messina provides such an example. Jan Van Eyck was among the first to adopt the new technique of oil painting, which enabled the artist to paint details with absolute precision (Fig. 10). Antonello, a generation later, learned the oil-painting technique during a trip to Flanders and applied it to the Italian Renaissance style, thus adding perspective to the architectural background of his paintings. Further, Antonello learned to execute portraits: a genre that was popular in northern Europe, but nearly unknown elsewhere. Back home in Sicily, Antonello introduced his own touch by adding subtle twists of psychological interpretation (Fig. 11).

Fig. 10 Jan Van Eyck. Portrait of Jan de Leeuw (1436).

Fig. 11 Antonello da Messina. Portrait of a Man (1465). Museo Mandralisca, Cefalù, Sicily.

The Legacy

The transmission over the years of the body of knowledge and experience of a school represents its legacy. The surgical legacy was alluded to when mention was made of the influence of the Viennese school of Theodor Billroth.

Numerous are the examples of the legacy of the schools of art. It is interesting that this legacy has involved many forms of artistic expression, notably architecture. There, it is sufficient to mention how the neoclassical architecture of the great 16th-century master Andrea Palladio has been the inspiration behind the design of many buildings around the world, notably that of the White House in Washington.

Symbolic Representation

In the great fresco The School of Athens (Fig. 12), which covers an entire wall of the papal palace in the Vatican, Raphael depicted a host of the most notable Greek philosophers, conversing in the beautiful setting of a classical Greek temple. In his rendering of the subject, he substituted portraits of his contemporaries for some of the hypothetical portraits of Greek philosophers. Scholars, indeed, are still debating the identities of some of the figures portrayed, but many are easily recognizable, including the artist's self-portrait next to his mentor Perugino, and Leonardo, Michelangelo, Botticelli, and Bramante.

Fig. 12 Raffaello Sanzio. The School of Athens (1509–10). The Vatican.

Conclusion

Surgeons of my generation have had the good fortune and the privilege of witnessing first hand the development of cardiovascular surgery as it was realized by the great pioneers who were our mentors. I wish to express our gratitude; we can only hope to pass along this tradition of professional achievement to the cardiovascular surgeons of the generations that succeed us.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Ugo Filippo Tesler, MD, Department of Cardiac Surgery, Policlinico di Monza, Clinica San Gaudenzio, Via Bottini 3, 28100 Novara, Italy

★ CME Credit

Presented at the Joint Session of the Michael E. DeBakey International Surgical Society and the Denton A. Cooley Cardiovascular Surgical Society; Austin, Texas, 21–24 June 2012.

E-mail: utesler@gmail.com