Abstract

We developed 18 polymorphic simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers in pineapple (Ananas comosus) by using genomic libraries enriched for GA and CA motifs. The markers were used to genotype 31 pineapple accessions, including seven cultivars and 11 breeding lines from Okinawa Prefecture, 12 foreign accessions and one from a related species. These SSR loci were highly polymorphic: the 31 accessions contained three to seven alleles per locus, with an average of 4.1. The values of expected heterozygosity ranged from 0.09 to 0.76, with an average of 0.52. All 31 accessions could be successfully differentiated by the 18 SSR markers, with the exception of ‘N67-10’ and ‘Hawaiian Smooth Cayenne’. A single combination of three markers TsuAC004, TsuAC010 and TsuAC041, was enough to distinguish all accessions with one exception. A phenogram based on the SSR genotypes did not show any distinct groups, but it suggested that pineapples bred in Japan are genetically diversed. We reconfirmed the parentage of 14 pineapple accessions by comparing the SSR alleles at 17 SSR loci in each accession and its reported parents. The obtained information will contribute substantially to protecting plant breeders’ rights.

Keywords: Ananas comosus, genetic diversity, parentage, simple sequence repeat

Introduction

The pineapple (Ananas comosus (L.) Merr.) is the most economically important edible plant of the family Bromeliaceae, which includes about 2,000 species, most epiphytic and many strikingly ornamental (Morton 1987). Pineapple is cultivated in most tropical and subtropical countries and in other regions with mild climates, ranking third in world production among tropical fruits, after banana and citrus (Botella and Smith 2008). Many pineapple cultivars are grown, differing in characteristics such as plant and fruit size, flesh color and flavor and leaf margin type. Nearly all cultivars for commercial production are classified into a particular “type” category; examples include Cayenne, Queen, Maipure, Red Spanish, Singapore Spanish, Abacaxi and Cabezona (Wee and Thongtham 1991).

In Japan, high-quality pineapple fruits can be produced only during the summer in the Ryukyu Islands, which stretch southwest from Kyushu to Taiwan (Republic of China), because the islands have a subtropical climate with mild winters and hot summers. Fruits harvested in winter are not suitable for the fresh-fruit market, because of low temperatures during fruit maturation. Pineapple cultivation in the Ryukyu Islands and Okinawa Prefecture started in the 1920s or 1930s after immigrants from Taiwan brought pineapples to these islands and the pineapple canning industry was important from the 1950s to the 1970s (Lin 1983, Watanabe 1961). After the trade of processed pineapple fruits was liberalized in 1990, the proportion of pineapple production intended for the fresh-fruit market gradually increased. In 2010, pineapple production in Okinawa was about 10,000 t (Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Statistical Yearbook; http://www.maff.go.jp/j/tokei), 60% for fresh fruit consumption and the remainder for processing.

Systematic pineapple breeding started in Okinawa Prefecture in 1989 and seven new elite cultivars have since been released for the fresh-fruit market. Several different types of cultivars (Cayenne, Queen, Maipure, Spanish and others), breeding lines and foreign accessions have been used as sources of specific characteristics (e.g., early ripening, high sugar content and low acidity). To establish effective breeding strategies, it is necessary to assess the genetic backgrounds of Japanese cultivars and other breeding materials by using molecular markers. In addition, it will be necessary to establish DNA profiling technique to protect new elite cultivars of pineapple.

In the plant variety protection (PVP) system in Japan, two main points were added by “Amendment of the Act in 2005” (http://www.hinsyu.maff.go.jp/en/about/overview.pdf) under the national policy for strengthening of intellectual property right. One was that coverage of plant breeders’ rights (PBR) was expanded for products directly obtained from harvested material of the protected variety, because variety identification technique by DNA analysis has been developed. Another was extension of the duration of PBR for 30 years for fruit trees and woody plants. Therefore, DNA profiling technique would be important for protection of PBR in fruit species including pineapple.

Up to now, several DNA profiling techniques have been used for cultivar identification and for evaluating genetic diversity in pineapple. Ruas et al. (1995) used random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) markers to estimate the relationships among four major pineapple cultivars in Brazil and Popluechai et al. (2007) analyzed nine pineapple cultivars in Thailand with 40 RAPD primers. Kato et al. (2004) used amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) markers to evaluate 148 accessions of A. comosus and 14 of related species. Among the available molecular markers, simple sequence repeat markers (SSRs, also known as microsatellites) provide a reliable method for cultivar identification because of their co-dominant inheritance and the abundance of alleles per locus (Weber and May 1989). Wohrmann and Weising (2011) developed 18 EST-SSR loci that showed polymorphism in pineapple. However, DNA profiling in pineapple by SSR markers has been rarely studied.

In this study, we developed 18 new genomic SSR markers in pineapple by using an enriched genomic library approach. We used them in cultivar identification, genetic diversity analysis, and parentage reconfirmation of 31 pineapple accessions including Japanese cultivars, breeding lines and foreign accessions.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials and DNA extraction

The 31 materials consisted of seven newly released cultivars from Okinawa Prefectural Agricultural Research Center Nago Branch (OPARC-Nago, Okinawa, Japan); 11 breeding lines from OPARC-Nago; 12 foreign accessions introduced from the USA, Brazil, Taiwan and Australia and one related species, Ananas ananassoides (Table 1). All materials were maintained at OPARC-Nago. Genomic DNA was isolated from young leaves by using a Genomic-tip 20/G (Qiagen, Germany) as described by Yamamoto et al. (2006) or by using a DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Table 1.

Pineapple accessions used in this study

| Accession name | Parentage | Origin and type | Parentage assessed by SSR markers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Barrel | Cream Pineapple × McGregor ST-1 | cultivar, bred by OPARC-Nagoa | parentage confirmed except for TsuAC018 |

| Haney Bright | Mitsubishi Smooth Cayenne × I-43-908 | cultivar, bred by OPARC-Nago | |

| Julio Star | N67-10 × Cream Pineapple | cultivar, bred by OPARC-Nago | parentage confirmed |

| N67-10 | selection from Hawaiian Smooth Cayenne | cultivar, bred by OPARC-Nago | identical genotype to Hawaiian Smooth Cayenne |

| Soft Touch | Hawaiian Smooth Cayenne × I-43-880 | cultivar, bred by OPARC-Nago | parentage confirmed |

| Summer Gold | Cream Pineapple × McGregor ST-1 | cultivar, bred by OPARC-Nago | parentage confirmed |

| Yugafu | Cream Pineapple × HI101 | cultivar, bred by OPARC-Nago | parentage confirmed |

| Okinawa No. 2 | Mitsubishi Smooth Cayenne × I-43-908 | breeding line, bred by OPARC-Nago | |

| Okinawa No. 3 | Mitsubishi Smooth Cayenne × I-43-908 | breeding line, bred by OPARC-Nago | |

| Okinawa No. 9 | N67-10 × Cream Pineapple | breeding line, bred by OPARC-Nago | parentage confirmed |

| Okinawa No. 13 | Cream Pineapple × Okinawa No. 2 | breeding line, bred by OPARC-Nago | parentage confirmed |

| Okinawa No. 17 | Yugafu × Summer Gold | breeding line, bred by OPARC-Nago | parentage confirmed |

| Okinawa No. 19 | Yugafu × Soft Touch | breeding line, bred by OPARC-Nago | parentage confirmed |

| Okinawa No. 20 | Yugafu × Summer Gold | breeding line, bred by OPARC-Nago | parentage not confirmed, candidate parentage of Yugafu × N67-10 |

| Okinawa No. 21 | Yugafu × A1031 | breeding line, bred by OPARC-Nago | parentage between Okinawa No. 21 and Yugafu confirmed |

| Okinawa No. 22 | A882 × Soft Touch | breeding line, bred by OPARC-Nago | parentage confirmed |

| Okinawa No. 23 | Julio Star × Okinawa No. 12 | breeding line, bred by OPARC-Nago | parentage between Okinawa No. 23 and Julio Star confirmed |

| Okinawa No. 24 | Soft Touch × Summer Gold | breeding line, bred by OPARC-Nago | parentage confirmed |

| A. ananasoides | indigenous, introduced from Brazil, A. ananasoides | ||

| A882 | Ripely Queen × Puerto Rico | breeding line | |

| Bogor | Smooth Cayenne × Singapore Spanish | breeding line | |

| Cream Pineapple | indigenous, introduced from USA, Maipure type | ||

| Hawaiian Smooth Cayenne | indigenous, introduced from USA, Cayenne type | identical genotype to N67-10 | |

| HI101 | breeding line, introduced from USA | ||

| I-43-880 | unknown, introduced from Brazil | ||

| McGregor ST-1 | indigenous, introduced from Australia, Queen type | ||

| MD2 | 58-1184 × 59-443 | cultivar, introduced from USA | |

| Red Spanish | indigenous, intoroduced from Brazil, Spanish type | ||

| Seijyo Cayenne | indigenous, introduced from Taiwan, Cayenne type | ||

| Tainung No. 11 | (Smooth Cayenne × Mouritius) × Smooth Cayenne | cultivar, introduced from Taiwan | |

| Tainung No. 17 | Smooth Cayenne × Rough | cultivar, introduced from Taiwan |

OPARC-Nago: Okinawa Prefectural Agricultural Research Center Nago Branch

SSR development

We used genomic DNA of pineapple ‘N67-10’ to construct SSR-enriched genomic libraries for GA and CA motifs by the method described by Nunome et al. (2006). The repeat-enriched genomic DNA was ligated into the pCR2.1-TOPO vector (TOPO TA Cloning Kit, Invitrogen, the Netherlands). Plasmid DNA was isolated and sequenced with the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing analysis was conducted with an ABI PRISM 3130xl sequencer (Applied Biosystems, USA).

A total of 384 plasmid sequences were obtained: 192 from GA-enriched genomic libraries and 192 from CA-enriched libraries. Plasmid sequences with no insert were excluded from further analysis, and the minimum number of SSR repeats for marker development was set as eight repeats for di-nucleotide motifs of GA/CT or CA/GT. Primer pairs were designed with the Primer3 Web interface (Rozen and Skaletsky 2000, http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer3/input.htm). The general primer-picking conditions included a primer size of 20–25 bp (optimum 23 bp), a primer Tm of 57–67°C (optimum 63°C), a maximum Tm difference of 1°C, a primer GC content of 50%–60% (optimum 55%) and a product size range of 100–300 bp.

SSR analysis

SSR-PCR amplification was performed in a 10-μL reaction mixture containing 5 μL of GoTaq Master Mix including GoTaq DNA Polymerase (Promega, USA), 5 pmol each of forward primer (fluorescently labeled with Fam, Vic, or Ned) and reverse primer (unlabeled), and 5 ng of genomic DNA. DNA was amplified in 35 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min and 72°C for 2 min and a final extension of 10 min at 72°C. The nucleotide sequence of “gtttctt” was added to the 5′ end of reverse primers as pig-tailing (Brownstein et al. 1996), in order to promote adenylation and facilitate accurate genotyping. The amplified PCR products were separated and detected in a PRISM 3100 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, USA). The sizes of the amplified bands were scored against internal-standard DNA (400HD-ROX, Applied Biosystems, USA) by GeneScan software (Applied Biosystems, USA).

Data analysis

Using the CERVUS v. 2.0 software (Marshall et al.1998) and MarkerToolKit v. 1.0 (Fujii et al. 2008), we estimated the expected heterozygosity (HE) at single-locus SSR markers in the tested pineapple cultivars. HE was calculated using an unbiased formula from allele frequencies as 1 − ∑pi2 (1 ≤ i ≤ m), where m is the number of alleles at the target locus and pi is the allele frequency of the ith allele at the target locus.

Parent-offspring relationships were tested by comparing the SSR alleles in each accession with those of its reported parents; the data were analyzed using the MARCO software (Fujii et al. unpublished). MinimalMarker software (Fujii et al. 2007) was used to identify minimal marker subsets to distinguish all cultivars and to find identical genotypes generated from the 18 SSR markers for the 31 accessions.

A phenogram of the 31 accessions was constructed by using the unweighted pair-group method with using arithmetic mean (UPGMA) based on the similarities between genotypes estimated by Dice’s coefficient: Dc = 2nxy/(nx + ny), where nx and ny represent the number of putative SSR alleles for materials X and Y, respectively, and nxy represents the number of putative SSR alleles shared between X and Y. NTSYS-pc v. 2.1 software (Rohlf 1998) was used to visualize the phenogram.

Results

SSR marker development

We sequenced 384 plasmid clones from GA- and CA-enriched genomic libraries of ‘N67-10’ (192 clones from each library). After exclusion of clones with no inserts, ambiguous nucleotide sequences, no repeat motifs, and duplication, 110 sequences that contained at least eight repeats of a di-nucleotide motif remained from the GA-enriched genomic library. These sequences contained 8 to 49 repeat motifs of (GA)/(CT), with 16.8 on average. The average insert size of the clones obtained was about 202 bp, ranging from 84 to 443 bp. Ninety-eight sequences were obtained from the CA-enriched library containing 8 to 31 repeats of (CA)/(GT), with an average of 12.8. The average insert size of the clones obtained was about 255 bp, ranging from 122 to 552 bp. A total of 42 primer pairs were designed with the Primer3 program: 23 for GA repeats and 19 for CA repeats.

We screened and evaluated the 42 SSR primer pairs by using eight pineapple accessions: ‘N67-10’, ‘Cream Pineapple’, ‘Julio Star’, ‘Summer Gold’, ‘Yugafu’, Okinawa No. 17, ‘Soft Touch’ and Okinawa No. 19. Out of the 42 SSR marker candidates, 24 were excluded from further analysis because of no amplification or unstable amplification of the target band. The remaining 18 markers (7 with GA-repeat motifs and 11 with CA-repeat motifs) were used for SSR analysis of all 31 pineapple accessions (Table 2). Among the seven GA-repeat SSR markers, five showed perfect repeats of a GA motif, whereas TsuAC010 and TsuAC013 had combined motifs of (GT)14A(AG)12 and (AGAGAT)3(AG)12, respectively. Out of the 11 CA-repeat SSRs, nine showed perfect repeats of a CA motif, whereas TsuAC018 and TsuAC023 had an interrupted CA motif of (CA)10A(AC)9 and a combined motif of (CA)10(TA)11, respectively.

Table 2.

Characteristics of 18 nelwly developed SSR markers in pineapple

| SSR locus Accession nos.a |

Primer sequence (5′-3′) | Repeat motif | Target size (bp) | No. of allels | (HE) Heterozygosity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TsuAC004 AB716708 |

F: ATGTTGGTCAAAGGGCTGTT R: gtttcttTCATGATCACACTGGAGATTTG |

(AG)16 | 144 | 5 | 0.67 |

| TsuAC007 AB716709 |

F: GCAGCGGTAAGATCTGCTTT R: gtttcttTCCTTCTCTCCACCTCTTCATT |

(GA)21 | 102 | 4 | –b |

| TsuAC008 AB716710 |

F: GAAATGGTACTGCTTCACTGTTC R: gtttcttATACGGGGAAATAGGCACAA |

(GA)16 | 173 | 5 | 0.71 |

| TsuAC010 AB716711 |

F: TGAGTTGTGTCATTGTGTGTCA R: gtttcttGGGGGTCTCCATACATTTTT |

(GT)14A(AG)12 | 207 | 7 | 0.76 |

| TsuAC013 AB716712 |

F: TTATGCAGGAAAATAGGGGG R: gtttcttCATGCATCATAAATTCGTGTCC |

(AGAGAT)3(AG)12 | 139 | 4 | 0.55 |

| TsuAC018 AB716713 |

F: GCATCGATCTCCATGCAAAC R: gtttcttAAAGGAAACAAGGAGGATGTGA |

(CA)10A(AC)9 | 120 | 5 | 0.59 |

| TsuAC019 AB716714 |

F: TTCATCCTATGGTTTCCCCA R: gtttcttGTGGGTTCAACTGAGTAGCAAT |

(AC)13 | 177 | 4 | 0.09 |

| TsuAC021 AB716715 |

F: AATCAAAGTGATTCCCCTTCC R: gtttcttTCTGACATAGGGCTTGCACA |

(CA)21 | 141 | 4 | 0.50 |

| TsuAC023 AB716716 |

F: TCGAAAAGAGGATGCTGGAT R: gtttcttTCCGCAGTGTAGGCATGTAA |

(CA)10(TA)11 | 143 | 5 | 0.73 |

| TsuAC024 AB716717 |

F: GTCGCCAATCAAATTCCAGT R: gtttcttCTCACGAAACATGAATCACCA |

(AC)9 | 126 | 3 | 0.52 |

| TsuAC026 AB716718 |

F: GGGATTAACTTTTCCAGGGG R: gtttcttTTGGATTCCTCGTTTGCATT |

(AC)8 | 200 | 4 | 0.09 |

| TsuAC028 AB716719 |

F: TGACACCATAGAGGAGGGGT R: gtttcttGCTCAAGGACAATCCACCAT |

(AC)8 | 220 | 3 | 0.57 |

| TsuAC030 AB716720 |

F: GAGAGAGAAAAGAGTTTCGACAG R: gtttcttCTTCAAAATGGTCTAACGTACC |

(AG)27 | 149 | 4 | 0.43 |

| TsuAC035 AB716721 |

F: TTCCTAGCCAACACTACTACAGA R: gtttcttTGCAGCTTCTTTTCCTGGTT |

(GA)9 | 96 | 3 | 0.45 |

| TsuAC038 AB716722 |

F: TTGCAGCAAACCAAGTCAT R: gtttcttGGAGGTGTAGTCAATTAGGAGAA |

(AC)11 | 327 | 3 | 0.48 |

| TsuAC039 AB716723 |

F: CCCTGTATGGGTAGCATTGAA R: gtttcttAAAAGGTATCACGAAAGCGA |

(AC)8 | 91 | 3 | 0.54 |

| TsuAC040 AB716724 |

F: AAATTCTCTTCATGCACACG R: gtttcttTGCTTCATGAGATCTAAACTGG |

(AC)8 | 99 | 4 | 0.61 |

| TsuAC041 AB716725 |

F: CTCTCTTATGGCACAACCCTG R: gtttcttCCTGGTGAGTAATCTATATGCTG |

(AC)11 | 279 | 4 | 0.58 |

| Average | 4.1 | 0.52 |

DDBJ accession numbers

Heterozygosity not evaluated because of the existence of null allele

Genetic identification of pineapple

We identified 74 putative alleles in the 31 pineapple accessions with the 18 SSR markers (Table 2). The number of alleles per locus ranged from three at five of the loci (TsuAC024, TsuAC028, TsuAC035, TsuAC038 and TsuAC039) to seven at TsuAC010, with an average value of 4.1 (Table 2). The expected heterozygosity (HE) ranged from 0.09 at TsuAC019 and TsuAC026 to 0.76 at TsuAC010, with an average value of 0.52.

The 31 pineapple accessions could be successfully differentiated from one another by the 18 SSR markers, with the exception of ‘N67-10’ and ‘Hawaiian Smooth Cayenne’ (Table 3 and Fig. 1). A single combination of three markers (TsuAC004, TsuAC010 and TsuAC041) was enough to distinguish 30 accessions (all except for ‘N67-10’ and ‘Hawaiian Smooth Cayenne’) on the basis of at least one difference in SSR genotype. Furthermore, ten marker subsets consisting of six SSR markers each (e.g., TsuAC004, TsuAC008, TsuAC010, TsuAC030, TsuAC039 and TsuAC041) could differentiate 30 accessions on the basis of two or more SSR genotype differences.

Table 3.

Genotypes of 18 SSR markers in pineapple accessions used in this study

| Cultivar name | SSR genotypes | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| TsuAC004 | TsuAC007 | TsuAC008 | TsuAC010 | TsuAC013 | TsuAC018 | TsuAC019 | TsuAC021 | TsuAC023 | TsuAC024 | TsuAC026 | TsuAC028 | TsuAC030 | TsuAC035 | TsuAC038 | TsuAC039 | TsuAC040 | TsuAC041 | |

| Gold Barrel | 135/143 | 101/101 | 178/180 | 212/232 | 139/139 | 109/109 | 177/177 | 118/118 | 138/168 | 126/131 | 203/203 | 217/223 | 145/158 | 88/95 | 330/330 | 93/95 | 95/95 | 276/276 |

| Haney Bright | 135/137 | 101/101 | 176/186 | 207/232 | 126/135 | 121/121 | 177/177 | 118/118 | 132/132 | 126/126 | 203/203 | 223/223 | 145/158 | 95/95 | 330/336 | 95/95 | 95/95 | 275/279 |

| Julio Star | 137/143 | 101/101 | 176/180 | 212/212 | 139/139 | 109/121 | 177/177 | 143/143 | 132/168 | 126/131 | 203/203 | 217/223 | 145/145 | 88/95 | 330/336 | 93/95 | 95/97 | 276/276 |

| N67-10 | 137/143 | 101/101 | 176/186 | 207/212 | 135/139 | 121/121 | 177/177 | 118/143 | 132/144 | 126/131 | 203/203 | 217/223 | 145/145 | 88/95 | 330/336 | 93/95 | 95/99 | 276/279 |

| Soft Touch | 137/143 | 101/101 | 176/186 | 212/214 | 139/151 | 111/121 | 177/177 | 118/143 | 138/144 | 126/131 | 203/203 | 223/223 | 145/158 | 95/95 | 336/336 | 91/93 | 95/103 | 276/276 |

| Summer Gold | 135/135 | 101/101 | 180/186 | 212/232 | 139/139 | 109/121 | 177/177 | 118/118 | 138/168 | 126/131 | 203/203 | 217/223 | 145/158 | 88/95 | 330/336 | 95/95 | 97/99 | 276/279 |

| Yugafu | 135/135 | 101/101 | 186/186 | 207/207 | 139/139 | 121/121 | 177/177 | 118/118 | 132/144 | 126/131 | 203/203 | 217/217 | 145/145 | 88/95 | 336/336 | 93/95 | 95/95 | 276/279 |

| Okinawa No. 2 | 135/143 | 101/101 | 176/186 | 207/232 | 126/135 | 121/121 | 177/177 | 118/118 | 132/132 | 126/126 | 203/203 | 219/223 | 145/158 | 95/95 | 330/336 | 93/95 | 95/95 | 275/279 |

| Okinawa No. 3 | 135/143 | 101/101 | 176/186 | 207/232 | 126/135 | 121/121 | 177/177 | 118/118 | 132/132 | 126/126 | 203/203 | 219/223 | 145/145 | 88/95 | 330/336 | 93/95 | 95/95 | 275/276 |

| Okinawa No. 9 | 135/137 | 101/101 | 180/186 | 212/212 | 139/139 | 109/121 | 177/177 | 143/143 | 132/168 | 126/131 | 203/203 | 217/223 | 145/145 | 95/95 | 336/336 | 95/95 | 95/97 | 276/279 |

| Okinawa No. 13 | 135/143 | 101/101 | 186/186 | 207/232 | 126/139 | 121/121 | 177/177 | 118/143 | 132/144 | 126/131 | 203/203 | 217/223 | 145/145 | 95/95 | 336/336 | 93/93 | 95/97 | 275/275 |

| Okinawa No. 17 | 135/135 | 101/101 | 186/186 | 207/232 | 139/139 | 109/121 | 177/177 | 118/118 | 138/144 | 126/131 | 203/203 | 217/223 | 145/145 | 88/95 | 336/336 | 95/95 | 95/97 | 276/279 |

| Okinawa No. 19 | 135/143 | 101/101 | 176/186 | 207/212 | 139/139 | 111/121 | 177/177 | 118/143 | 138/144 | 126/131 | 203/203 | 217/223 | 145/158 | 88/95 | 336/336 | 93/93 | 95/103 | 276/276 |

| Okinawa No. 20 | 135/137 | 101/101 | 186/186 | 207/212 | 135/139 | 121/121 | 177/177 | 118/118 | 132/144 | 126/131 | 203/203 | 217/217 | 145/145 | 95/95 | 330/336 | 95/95 | 95/95 | 276/279 |

| Okinawa No. 21 | 135/135 | 101/101 | 186/186 | 207/232 | 139/139 | 109/121 | 177/177 | 118/118 | 138/144 | 126/131 | 203/203 | 217/223 | 145/145 | 95/95 | 330/336 | 93/93 | 95/95 | 279/279 |

| Okinawa No. 22 | 137/143 | 101/101 | 178/186 | 214/214 | 135/139 | 117/121 | 177/177 | 143/143 | 138/138 | 126/131 | 203/203 | 223/223 | 145/158 | 88/95 | 336/336 | 93/93 | 97/103 | 276/276 |

| Okinawa No. 23 | 135/143 | 101/101 | 180/180 | 212/232 | 139/139 | 109/109 | 177/177 | 143/143 | 138/168 | 131/131 | 203/203 | 217/217 | 145/145 | 88/95 | 330/330 | 95/95 | 97/97 | 276/279 |

| Okinawa No. 24 | 135/143 | 101/101 | 180/186 | 214/232 | 139/151 | 109/121 | 177/177 | 118/118 | 138/168 | 126/131 | 203/203 | 223/223 | 145/158 | 95/95 | 336/336 | 91/95 | 95/99 | 276/276 |

| A. ananasoides | 145/153 | 86/110 | 178/184 | 216/226 | 126/126 | 118/118 | 189/204 | 155/163 | 158/158 | 129/129 | 199/203 | 219/219 | 151/156 | 88/88 | 324/324 | 93/93 | 97/97 | 277/277 |

| A882 | 137/137 | 101/101 | 178/178 | 207/214 | 135/135 | 117/121 | 177/177 | 143/143 | 132/138 | 126/126 | 203/203 | 223/223 | 145/145 | 88/89 | 336/336 | 93/95 | 97/97 | 276/276 |

| Bogor | 135/143 | 101/101 | 176/178 | 207/232 | 135/139 | 121/121 | 177/177 | 118/143 | 138/144 | 131/131 | 203/203 | 223/223 | 145/158 | 95/95 | 330/336 | 93/95 | 95/99 | 276/279 |

| Cream Pineapple | 135/137 | 101/101 | 180/186 | 207/212 | 139/139 | 109/121 | 177/177 | 118/143 | 144/168 | 131/131 | 203/203 | 217/217 | 145/145 | 88/95 | 330/336 | 93/95 | 95/97 | 275/276 |

| Hawaiian Smooth Cayenne | 137/143 | 101/101 | 176/186 | 207/212 | 135/139 | 121/121 | 177/177 | 118/143 | 132/144 | 126/131 | 203/203 | 217/223 | 145/145 | 88/95 | 330/336 | 93/95 | 95/99 | 276/279 |

| HI101 | 135/143 | null/null | 178/186 | 207/214 | 139/139 | 117/121 | 177/177 | 118/143 | 132/132 | 126/131 | 203/203 | 217/217 | 145/145 | 88/95 | 336/336 | 93/95 | 95/95 | 276/279 |

| I-43-880 | 137/137 | 101/101 | 176/176 | 212/214 | 139/151 | 111/111 | 177/177 | 118/143 | 138/138 | 126/126 | 203/203 | 223/223 | 158/158 | 95/95 | 336/336 | 91/95 | 97/103 | 276/276 |

| McGregor ST-1 | 135/143 | null/null | 178/186 | 232/232 | 135/139 | 121/121 | 177/177 | 118/118 | 138/138 | 126/131 | 203/203 | 223/223 | 145/158 | 95/95 | 330/336 | 93/95 | 95/99 | 276/279 |

| MD2 | 135/137 | 101/101 | 178/178 | 207/232 | 135/139 | 117/117 | 177/177 | 143/143 | 132/138 | 126/126 | 203/203 | 217/223 | 145/145 | 88/95 | 330/336 | 93/95 | 95/103 | 275/276 |

| Red Spanish | 135/137 | 101/101 | 178/178 | 233/233 | 135/139 | 117/117 | 175/177 | 118/143 | 132/132 | 126/126 | 207/209 | 217/219 | 145/158 | 95/95 | 330/336 | 95/95 | 95/95 | 276/279 |

| Seijyo Cayenne | 137/137 | 101/101 | 176/178 | 207/233 | 135/139 | 117/121 | 177/177 | 118/118 | 132/132 | 126/126 | 203/203 | 217/217 | 145/158 | 88/95 | 330/336 | 95/95 | 95/99 | 276/279 |

| Tainung No. 11 | 135/143 | 101/101 | 186/186 | 207/232 | 139/139 | 121/121 | 177/177 | 118/118 | 138/144 | 126/131 | 203/203 | 217/223 | 145/158 | 95/95 | 336/336 | 95/95 | 95/99 | 276/276 |

| Tainung No. 17 | 135/137 | 101/101 | 176/186 | 207/232 | 135/139 | 121/121 | 177/177 | 118/118 | 132/138 | 126/131 | 203/203 | 217/223 | 145/158 | 88/95 | 330/336 | 93/93 | 95/95 | 276/279 |

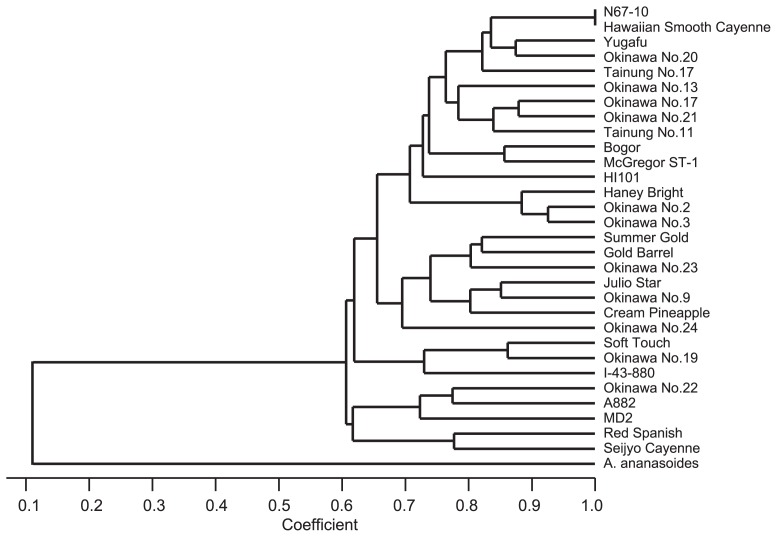

Fig. 1.

Phenogram of the 31 pineapple accessions evaluated in this study. The phenogram was produced using the UPGMA method based on Dice’s coefficient.

We constructed a phenogram of the 31 accessions based on SSR analysis (Fig. 1). The accession belonging to the related species A. ananasoides was clearly separated from the other 30 pineapple accessions. These 30 pineapple accessions were not separated into distinct groups but seemed to be mingled together, and there was little relationship between the cultivar types and the genetic distances based on the SSR analysis. Although some accessions were used representing several types, i.e., ‘Cream Pineapple’ (Maipure type), ‘McGregor ST-1’ (Queen type), ‘Red Spanish’ (Spanish type), ‘Seijyo Cayenne’ and ‘Hawaiian Smooth Cayenne’ (Cayenne type), no distinct groups were found.

Parentage analysis

We examined parent-offspring relationships of 15 pineapple cultivars and breeding lines bred by OPARC-Nago by using 17 SSR genotypes of the 18 loci (Table 3, all except for TsuAC007). SSR analysis suggested that ‘N67-10’ had been selected and bred from a sport or mutant of ‘Hawaiian Smooth Cayenne’ (Ikemiya et al. 1984). The parentage analysis was conducted by comparing SSR alleles in the accessions and their reported parents. The parentage of ten accessions (‘Soft Touch’, ‘Summer Gold’, ‘Yugafu’, ‘Julio Star’ and Okinawa No. 9, 13, 17, 19, 22 and 24) was reconfirmed: in each of these accessions, the SSR alleles at each locus were consistent with one allele being contributed by each of the reported parents. Parent-offspring relationships were also reconfirmed between Okinawa No. 21 and ‘Yugafu’ and Okinawa No. 23 and ‘Julio Star’; but in each case, the second parent was not available for testing. A discrepancy at one SSR locus TsuAC018 was found for ‘Gold Barrel’ and its reported parents ‘Cream Pineapple’ and ‘McGregor ST-1’, which might have been caused by a mutation, otherwise the existence of a null allele, i.e., 109/null, 109/121 and 121/null genotypes for ‘Gold Barrel’, ‘Cream Pineapple’ and ‘McGregor ST-1’, respectively. In the case of Okinawa No. 20, the SSR data were inconsistent with the reported parentage (‘Yugafu’ × ‘Summer Gold’) but suggested another possible set of parents (‘Yugafu’ × ‘N67-10’).

Discussion

Interest in plant breeders’ rights is increasing worldwide. The International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plant (UPOV; http://www.upov.int/index_en.html) promotes the development and use of effective systems of plant variety protection. The BMT (Biochemical and Molecular Techniques, and DNA-Profiling in Particular) working group of UPOV agreed to establish DNA profiling techniques for protecting plant breeders’ rights. In Japan, ten DNA profiling manuals for major crops, including rice (Oryza sativa L.), kidney bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), adzuki-bean (Vigna angularis (Willd.) Ohwi & Ohashi.), strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duchesne), sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) and Japanese pear (Pyrus pyrifolia Nakai), have been released on the Plant Variety Protection home page (http://www.hinsyu.maff.go.jp/en/en_top.html). Among them, methods for the use of SSR markers in fruit species are given for sweet cherry and Japanese pear.

Genome-specific CAPS markers had greatly contributed to prevent an infringement of breeder’s rights in strawberry (Kunihisa 2011). Packed strawberry fruits imported from Korea labeled as ‘Nyoho’ were identified to be a mix of ‘Redpearl’ and ‘Sachinoka’ by using CAPS markers (Kunihisa et al. 2005). After admonition to dealers and action to the court, the volume of illegally imported strawberry fruits sharply decreased. On the case of sweet cherry, ‘Benishuho’ in which Yamagata Prefecture holds the breeder’s right, was unlawfully taken out overseas by an Australian citizen residing in Tasmania, producing and selling fruits. Thus, Yamagata Prefecture established DNA profiling system for fruit tissues using SSR markers and lodged a criminal complaint against the exporters (Takashina et al. 2007, 2008). The other recent breeder’s rights infringement cases, DNA profiling methods were developed for rush, kidney bean, adzuki-bean and etc. In this study, the SSR-based identification system for major pineapple cultivars in Japan was developed, which will contribute greatly to protecting plant breeders’ rights.

Kato et al. (2004) reported that major cultivar types such as Cayenne, Spanish and Queen, could not be distinctively separated based on AFLP analysis using 148 accessions of A. comosus and 14 of related species. In this study, the 31 pineapple accessions were not clustered into distinct groups in a phenogram constructed from the results of the SSR analysis. Therefore, it is considered that cultivar types have been classified based on morphological similarity, and that DNA analysis was not in good accordance with morphological classification. Further DNA analysis will help us establish an accurate classification system. Our results suggested that abundant genetic variation existed within cultivars and breeding lines in Japan and foreign accessions. Discrete DNA profiling of pineapples by SSR markers will be utilized for cultivar protection systems.

Accurate information about parent-offspring relationships is necessary for efficient breeding programs. SSR markers have been used for parentage analyses of grapes (Bowers and Meredith 1997, Bowers et al. 1999, Sefc et al. 1997), peaches (Testolin et al. 2000, Yamamoto et al. 2003), apples (Kitahara et al. 2005, Moriya et al. 2011) and pears (Sawamura et al. 2008). We examined parent-offspring relationships of 15 pineapple cultivars by using 17 SSR loci and reconfirmed the parentage for 14 of the cultivars. In the case of Okinawa No. 20, a candidate for its true parent combination was identified.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. H. Fujii for valuable discussion and suggestions on the experiments and the manuscript.

Literature Cited

- Botella, J.R., and Smith, M (2008) Genomics of pineapple, crowning the king of tropical fruits. In: Moore, P. H., and Ming, R. (eds.) Plant Genetics/Genomics: Genomics of Tropical Crop Plants, Springer, USA, pp. 441–451 [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, J.E., and Meredith, C.P. (1997) The parentage of a classic wine grape, Cabernet Sauvignon. Nature Genet. 16: 84–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, J., Boursiquot, J.M., This, P., Chu, K., Johansson, H., and Meredith, C. (1999) Historical genetics: the parentage of Chardonnay, Gamay and other wine grapes of northeastern France. Science 285: 1562–1565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownstein, M.J., Carpten, J.D., and Smith, J.R. (1996) Modulation of nontemplated nucleotide addition by tag DNA polymerase: primer modifications that facilitate genotyping. Biotechniques 20: 1004–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, H., Ogata, T, Shimada, T, Endo, T, Shimizu, T, and Omura, M (2007) Development of a novel algorithm and the computer program for the identification of minimal marker sets of discriminating DNA markers for efficient cultivar identification. Plant & Animal Genomes XV Conference, p. 883 [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, H., Yamashita, H, Shimada, T, Endo, T, Shimizu, T, and Yamamoto, T (2008) MarkerToolKit: an analysis program for data sets consist of DNA maker types obtained from various varieties. DNA Polymorph. 16: 103–107 [Google Scholar]

- Ikemiya, H., Onaha, A., and Nakasone, H. (1984) Excellent strain N67-10 in pineapple. Kyushu Agricultural Research 46: 268 [Google Scholar]

- Kato, C.Y., Nagai, C, Moore, P.H., Zee, F, Kim, M.S., Steiger, D.L., and Ming, R (2004) Intra-specific DNA polymorphism in pineapple (Ananas comosus (L.) Merr.) assessed by AFLP markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 51: 815–825 [Google Scholar]

- Kitahara, K., Matsumoto, S, Yamamoto, T, Soejima, J, Kimura, T, Komatsu, H, and Abe, K (2005) Molecular characterization of apple cultivars in Japan by S-RNase analysis and SSR markers. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 130: 885–892 [Google Scholar]

- Kunihisa, M., Matsumoto, S, and Fukino, N (2005) Cultivar identification of strawberry fruits imported from Korea by use of DNA markers. Bull. Natl. Inst. Veg. Tea Sci. 4: 71–76 [Google Scholar]

- Kunihisa, M (2011) Studies using DNA markers in Fragaria × ananassa: genetic analysis, genome structure, and cultivar identification. J. Jpn. Soc. Hort. Sci. 80: 231–243 [Google Scholar]

- Lin, F (1983) History of pineapple industry in Okinawa, Okinawa pineapple industrial history publication, Japan, pp. 1–610 [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, T.C., Slate, J, Kruuk, L, and Pemberton, J.M. (1998) Statistical confidence for likelihood-based paternity inference in natural populations. Mol. Ecol. 7: 639–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriya, S., Iwanami, H., Okada, K., Yamamoto, T., and Abe, K. (2011) A practical method for apple cultivar identification and parent-offspring analysis using simple sequence repeat markers. Euphytica 177: 135–150 [Google Scholar]

- Morton, J (1987) Pineapple. In: Morton, J.F., and Miami, F.L. (eds.) Fruits of Warm Climates, pp. 18–28 [Google Scholar]

- Nunome, T., Negoro, S, Miyatake, K, Yamaguchi, H, and Fukuoka, H (2006) A protocol for the construction of microsatellite enriched genomic library. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 24: 305–312 [Google Scholar]

- Popluechai, S., Onto, S, and Eungwanichayapant, P.D. (2007) Relationships between some Thai cultivars of pineapple (Ananas comosus) revealed by RAPD analysis. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol. 29: 1491–1497 [Google Scholar]

- Rohlf, F.J. (1998) NTSYS, numerical taxonomy and multivariate analysis system, Ver. 2.01. Exeter Publishing, Ltd., Setauket, New York [Google Scholar]

- Rozen, S, and Skaletsky, H.J. (2000) Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. In: Krawetz, S., and Misener, S. (eds.) Bioinformatics Methods and Protocols: Methods in Molecular Biology, Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, pp. 365–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruas, P.M., Ruas, C.F., Fairbanks, D.J., Andersen, W.R., and Cabral, J.S. (1995) Genetic relationship among four varieties of pineapple, Ananas comosus, revealed by random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis. Brazilian Journal of Genetics 18: 413–416 [Google Scholar]

- Sawamura, Y., Takada, N, Yamamoto, T, Saito, T, Kimura, T, and Kotobuki, K (2008) Identification of parent-offspring relationships in 55 Japanese pear cultivars using S-RNase allele and SSR markers. J. Jpn. Soc. Hort. Sci. 77: 364–373 [Google Scholar]

- Sefc, K.M., Steinkellner, H., Wagner, H.W., Glossl, J., and Regner, F. (1997) Application of microsatellite markers to parentage studies in grapevine. Vitis 36: 179–183 [Google Scholar]

- Takashina, T., Ishiguro, M., Nishimura, K., and Yamamoto, T. (2007) Genetic identification of imported and domestic sweet cherry varieties using SSR markers. DNA Polymorphism 15: 101–104 [Google Scholar]

- Takashina, T., Endo, R., Fujii, H., and Yamamoto, T. (2008) Application of the genetic identification method of sweet cherry varieties for processed fruits. DNA Polymorphism 16: 95–98 [Google Scholar]

- Testolin, R., Marrazzo, T., Cipriani, G., Quarta, R., Verde, I., Dettori, M.T., Pancaldi, M., and Sansavini, S. (2000) Microsatellite DNA in peach (Prunus persica L. Batsch) and its use in fingerprinting and testing the genetic origin of cultivars. Genome 43: 512–520 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, S (1961) Cultivation and processing in pineapple, Ryukyu Canned Pineapple Association, Japan, pp. 84–88 [Google Scholar]

- Weber, J.K., and May, P.E. (1989) Abundant class of human DNA polymorphisms which can be typed using the polymerase chain reaction. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 44: 388–397 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wee, Y.C., and Thongtham, M.L.C. (1991) Ananas comosus (L.) Merr. In: Verheij, E.W.M., and Coronel, R.E. (eds.) Plant Resources of South-East Asia No. 2 Edible fruits and nuts. Pudoc, Wageningen, the Netherlands, pp. 66–71 [Google Scholar]

- Wohrmann, T, and Weising, K (2011) In silico mining for simple sequence repeat loci in a pineapple expressed sequence tag database and cross-species amplification of EST-SSR markers across Bromeliaceae. Theor. Appl. Genet. 123: 635–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, T., Mochida, K, Imai, T, Haji, T, Yaegaki, H, Yamaguchi, M, Matsuta, N, Ogiwara, I, and Hayashi, T (2003) Parentage analysis in Japanese peaches using SSR markers. Breed. Sci. 53: 35–40 [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, T., Kimura, T, Hayashi, T, and Ban, Y (2006) DNA profiling of fresh and processed fruits in pear. Breed. Sci. 56: 165–171 [Google Scholar]