Abstract

Seed shattering is a significant problem with buckwheat, especially at harvesting time. Several reports have shown that a green-flower mutant of buckwheat, such as W/SK86GF, has a strong pedicel. Although a strong pedicel may provide some resistance to shattering in the field, no study has thoroughly examined this issue. In this paper, we demonstrate that a W/SK86GF has shattering resistance by comparing the degrees of shattering of W/SK86GF and Kitawasesoba (leading variety of Hokkaido with non-green-flower traits) through a test for four years, including a typhoon hit year in the field. In a non-typhoon year, the shattering seed ratio (shattering seed weight/(yield + shattering seed weight) × 100) of W/SK86GF at maturing time +15 days (+15D) was lower than that of Kitawasesoba. In a typhoon hit year, the shattering seed ratios of Kitawasesoba at maturing time and +15D were surprisingly high, 14.4 and 21.1%, respectively. On the other hand, those of W/SK86GF were only 3.08% and 2.57%, respectively; indicating W/SK86GF is promising as a shattering resistant line even in a typhoon hit year. From these results, shattering resistance of W/SK86GF can be evaluated after maturing time such as +15D and pedicel strength would confer W/SK86GF a shattering resistant trait.

Keywords: buckwheat, shattering, green flower, pedicel, typhoon, breeding

Introduction

Buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum (L.) Moench) is cultivated in some countries and it is a useful and unique crop (Ikeda 2002, Kreft et al. 2003). Buckwheat is focused as a healthy food because it contains compounds considered to be healthy, such as rutin (Awatsuhara et al. 2010, Griffith et al. 1944, Jiang et al. 2007, Li et al. 2009, Morishita et al. 2007, Shanno 1946, Wieslander et al. 2011). On the other hand, buckwheat is a crop in which seed shattering is a significant problem, especially at harvesting time (Aufhammr et al. 1994, Lee et al. 1996). The cultivated species of buckwheat did not have any abscission layer across the pedicels, although the wild species did (Oba et al. 1998a). Therefore, pedicel breaking is the most important cause of shattering.

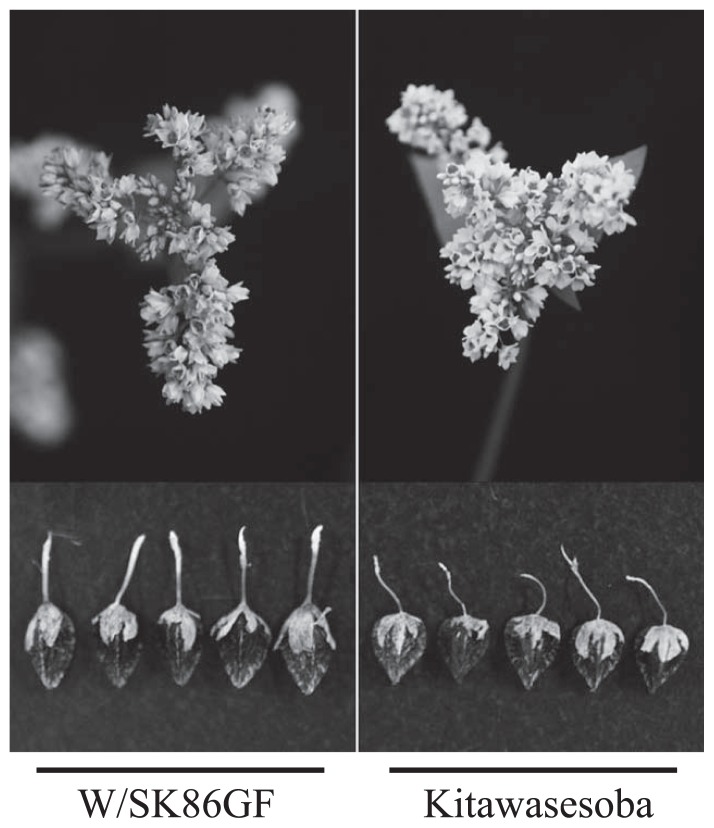

In Hokkaido (northern island of Japan which has the largest buckwheat-producing area in Japan), typhoons sometimes cause a great deal of damage to buckwheat production. In 2004, a typhoon hit year, buckwheat production in Hokkaido was 54% of that of the previous year. Several reports have shown possibilities to improve resistance of seed shattering in buckwheat. Oba et al. (1999) reported that the pedicel diameter correlated well with the breaking tensile strength in pedicels. This was supported by Fujimura et al. (2001). However, the breaking tensile strengths of buckwheat were much lower than those of other crops, such as rice (Ji et al. 2006). In addition, the varietal differences of breaking tensile strength have not been investigated in buckwheat. The Russian variety ‘Green flower’ has been reported to be a useful genetic resource of seed shattering resistance (Funatsuki et al. 2000). Green flower had leaf like green parts in petals with stronger pedicels than normal buckwheats (Alexeeva et al. 1988). They hypothesized that one important reason for strong pedicels is an increased number of vessels (Alexseeva et al. 1988). In Japan, we discovered a green-flower mutant named ‘W/SK86GF’ in 1999, which was from a progeny of hybridization between Kitawasesoba and Skorosperaya 86 (Fig. 1). The green-flower trait and strong pedicel of ‘W/SK86GF’ was dominated by a single recessive gene (Mukasa et al. 2008). Alekseeva et al. (1998) also reported that green-flower trait and strong pedicel of ‘Green flower’ was also dominated by a single recessive gene. Although a strong pedicel of buckwheat may be responsible for shattering resistance in the field, no research has focused on the degree of resistance.

Fig. 1.

Picture of flower and seed of W/SK86GF and Kitawasesoba

In this paper, we investigated varietal differences of breaking tensile strength using 23 buckwheat cultivars/ breeding lines including 3 types of green flower. In addition, we demonstrated that a W/SK86GF has shattering resistance by comparing W/SK86GF with Kitawasesoba in the field through tests for four years (2002, 2003, 2004 and 2011), which included one typhoon hit year (2004).

Materials and Methods

Plant materials and cultivation

We discovered a green-flower mutant in 1999, which was from a progeny of hybridization between Kitawasesoba and Skorosperaya 86. The green-flower mutant was crossed with ‘Kitawasesoba’ in 1999. In the F2 progeny, green-flower individuals were selected and propagated by isolation. By eliminating the white-flower individuals, the green-flower trait was fixed in 2002 (F4) and we named it as ‘W/SK86GF.’ Every buckwheat variety/cultivar tested was cultivated in an experimental field of Memuro, central Hokkaido, Japan (longitude: 143°03′, latitude: 42°53′). To evaluate shattering resistance, Kitawasesoba (a leading variety in the Hokkaido region) and W/SK86GF were sown in early June. They were sown in three replications on 4.8 square-meter plots in which the seeding density was 150 seeds/square meter.

Measurement of breaking tensile strength and shattering seed weight

The breaking tensile strength of the pedicel, which was the force required to detach a seed from a plant, was measured by a modified method of Oba et al. (1998b) using a tension gauge. The stem and a single seed were bound to a tension gauge by two pinches, and pulled using handles carefully. The force need to break the pedicel was recorded as the breaking tensile strength. The breaking tensile strength of the pedicel was measured when 80% of the seed darkened in each plant (maturing time) and 15 days after maturing time (+15D). For each replication, 15 flower clusters on the top of the main stems were used for measurement of the breaking tensile strength. For each flower cluster, 10 seeds were used for the evaluation. To evaluate the weight of shattering seeds, shattered buckwheat seeds in a 1.2 m-square plot were collected with tweezers after careful harvesting of buckwheat plants at maturing time and +15D.

Results

Varietal differences of breaking tensile strength

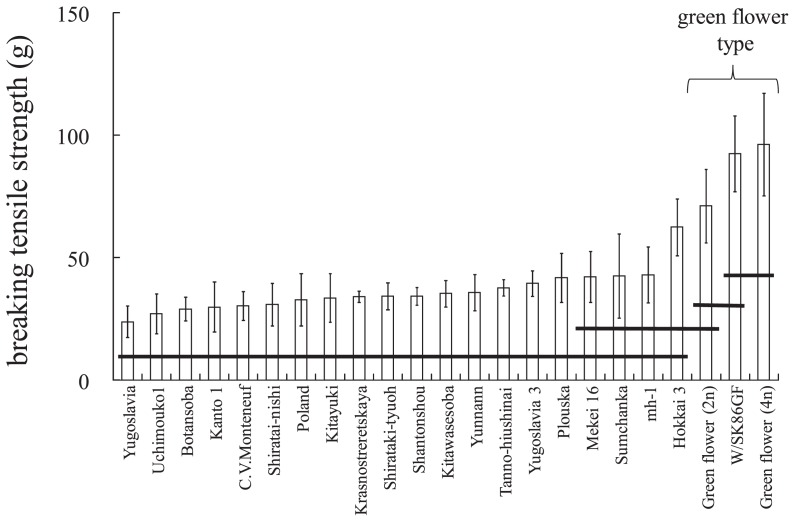

To develop a shattering resistant buckwheat lines, we investigated the varietal differences of the breaking tensile strength of buckwheat varieties from several countries, shown in Fig. 2: Japan (Botansoba, Kanto 1, Shirataki-nishi, Shirataki-tyuoh, Kitayuki, Kitawasesoba, Tanno-Hiushinai, Mekei16, mh-1, Hokkai 3, W/SK86GF); Russia (Krasnostreretskaya, Prouska, Sumchanka, Green flower (2n), Green flower (4n)); China (Uchimouko 1, Santonshou, Yunnan), Poland (Poland), Yugoslavia (Yugoslavia, Yugoslavia 3) and France (C. V. Monteneuf). The breaking tensile strengths of green-flower types were higher than those of other varieties (Fig. 2). Among them, although the breaking tensile strengths of Green flower (2n) did not have significant difference from some non-green flower varieties, those of W/SK86GF and Green flower (4n) were statistically higher than non-green-flower varieties. The pedicels of green flower buckwheat, such as W/SK86GF, were thicker than those of non-green-flower buckwheat, such as Kitawasesoba (Fig. 1).

Fig. 2.

Varietal difference of breaking tensile strength. The breaking tensile strength was measured at maturing time. Data are the means ±SD of 15 individuals. Means under the same horizontal line are not significantly different at p < 0.05 using Ryan’s multiple range test.

Characteristics related to shattering resistance in W/ SK86GF

At maturing time, the breaking tensile strength of W/SK86GF was about 2 to 3 times higher than that of Kitawasesoba (Table 1). At +15D, the breaking tensile strength of Kitawasesoba was lower than that at maturing time. This result is consistent with those of the other non-green-flower varieties (Oba et al. 1998a). However, in W/SK86GF, the breaking tensile strength at +15D was almost the same as that at maturing time (Table 1).

Table 1.

Changes in breaking tensil strength, shattering seed weight and its ratio in the varieties

| 2003 | 2004 | 2006 | 2011 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| breaking tensile strength (g) | W/SK86GF | maturing time | 74.8 ± 8.2 aa | 71.5 ± 14.8 a | 77.7 ± 4.5 a | 76.7 ± 8.3 a |

| +15Db | 72.2 ± 15.0 d | 72.2 ± 25.9 a | 66.5 ± 8.5 a | 51.2 ± 7.4 b | ||

|

| ||||||

| Kitawasesoba | maturing time | 31.8 ± 9.8 c | 17.6 ± 3.9 b | 36.2 ± 1.8 b | 22.8 ± 7.4 c | |

| +15D | 19.7 ± 6.1 b | 19.8 ± 6.0 b | 18.7 ± 3.3 c | 22.9 ± 9.8 c | ||

|

| ||||||

| shattering seed weight (kg/a) | W/SK86GF | maturing time | 0.03 ± 0.04 a | 0.47 ± 0.20 a | 0.01 ± 0.01 a | 0.19 ± 0.09 a |

| +15D | 0.06 ± 0.05 a | 0.42 ± 0.24 a | 0.02 ± 0.00 a | 0.19 ± 0.03 a | ||

|

| ||||||

| Kitawasesoba | maturing time | 0.05 ± 0.02 a | 2.42 ± 0.39 b | 0.05 ± 0.01 b | 0.18 ± 0.08 a | |

| +15D | 0.95 ± 0.34 b | 3.39 ± 0.42 b | 0.24 ± 0.07 c | 0.83 ± 0.16 b | ||

|

| ||||||

| shattering seed raito (%)c | W/SK86GF | maturing time | 0.22 ± 0.30 a | 3.08 ± 1.24 a | 0.08 ± 0.03 a | 1.00 ± 0.46 a |

| +15D | 0.39 ± 0.34 a | 2.57 ± 1.61 a | 0.12 ± 0.03 a | 0.96 ± 0.09 a | ||

|

| ||||||

| Kitawasesoba | maturing time | 0.23 ± 0.09 a | 12.4 ± 1.67 b | 0.28 ± 0.05 b | 0.69 ± 0.32 a | |

| +15D | 4.34 ± 1.63 b | 21.1 ± 0.80 c | 1.40 ± 0.31 c | 3.30 ± 0.60 b | ||

means ± SD.

Values with in the same row with different alphabets are significantly different (p < 0.05) among groups by Ryan’s multiple range test.

+15D means ‘maturing time + 15 days’.

Shattering seed weight/(yield + shattering seed weight) × 100.

In non-typhoon years, such as 2003, 2006 and 2011, the shattering seed weight at maturing time of W/SK86GF and Kitawasesoba was almost the same (Table 1). On the other hand, the shattering seed weight of W/SK86GF was smaller than that of Kitawasesoba at +15D (Table 1) although the yield of W/SK86GF was smaller than that of Kitawasesoba (Table 2). Therefore, to evaluate the shattering resistant trait precisely, we compared the shattering seed ratio (Shattering seed weight/(yield + shattering seed weight) × 100) between Kitawasesoba and W/SK86GF. The shattering seed ratio of W/SK86GF at +15D was lower than that of Kitawasesoba every year. This indicates that W/SK86GF would be promising as shattering resistant buckwheat, at least in non-typhoon years. Although difference of shattering seed weight between Kitawasesoba and W/SK86GF at +15D was several percents, the difference is important in terms of yield improvement.

Table 2.

Growth and yield characteristics of W/SK86GF

| sowing time mon. day | flowering time mon. day | maturing time mon. day | plant height cm | stem diameter mm | number of primary branches | number of nodes on main stem | number of flower clusters | lodging* | total weight kg/a | yield kg/a | ratio % | 1000 seed weight g | one liter weight g | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W/SK86GF | 2003 | 6.6 | 7.12 | 8.22 | 93 | 6.6 | 3.2 | 7.2 | 7.9 | 0.0 | 47.9 | 16.0 | 72 | 32.3 | 551 |

| 2004 | 6.8 | 7.12 | 8.25 | 116 | 6.5 | 2.8 | 11.2 | 14.6 | 5.0 | 73.6 | 15.1 | 82 | 26.0 | 518 | |

| 2006 | 6.6 | 7.18 | 8.19 | 108 | 5.6 | 2.7 | 10.8 | 12.9 | 1.0 | 44.4 | 14.9 | 88 | 27.9 | 562 | |

| 2011 | 6.3 | 7.8 | 8.15 | 127 | 6.2 | 2.3 | 11.6 | 13.1 | 3.0 | 42.8 | 13.0 | 76 | 27.8 | 541 | |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| average | 6.6 | 7.13 | 8.20 | 111 | 6.2 | 2.7 | 10.2 | 12.1 | 2.3 | 52.2 | 14.8 | 79 | 28.5 | 543 | |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Kitawasesoba | 2003 | 6.6 | 7.12 | 8.22 | 92 | 5.4 | 1.7 | 7.8 | 4.5 | 0.0 | 41.9 | 22.1 | 100 | 31.7 | 592 |

| 2004 | 6.8 | 7.12 | 9.01 | 120 | 5.6 | 2.3 | 11.9 | 12.8 | 5.0 | 83.3 | 18.4 | 100 | 29.0 | 602 | |

| 2006 | 6.6 | 7.18 | 8.17 | 99 | 4.9 | 2.5 | 9.9 | 10.4 | 1.0 | 41.7 | 17.0 | 100 | 29.1 | 611 | |

| 2011 | 6.3 | 7.8 | 8.15 | 123 | 5.4 | 3.3 | 10.3 | 12.4 | 1.0 | 47.4 | 17.0 | 100 | 27.8 | 613 | |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| average | 6.6 | 7.13 | 8.22 | 109 | 5.3 | 2.5 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 1.8 | 53.6 | 18.6 | 100 | 29.4 | 605 | |

0: none–5: much.

In 2004, strong typhoons struck Hokkaido, and buckwheat production decreased by 54% from that in 2003. In Memuro city where experiment was performed, strong typhoon hit at 20th August when buckwheat was just before maturing time. The shattering seed weights of Kitawasesoba at maturing time and +15D were 2.42 and 3.39 kg/a, respectively (Table 1). The shattering seed ratios of Kitawasesoba at maturing time and +15D were surprisingly high, 12.4 and 21.1%, respectively (Table 1). On the other hand, the shattering seed ratios of W/SK86GF at maturing time and +15D were only 3.08% and 2.57%, respectively (Table 1). This indicates that W/SK86GF has promise as shattering resistant buckwheat even in a typhoon hit year.

Growth and yield characteristics

The ecological characteristics, such as flowering and maturing time, were almost identical for Kitawasesoba and W/SK86GF. The growth characteristics, such as plant height, number of primary branches and number of nodes on the primary stem, were almost identical for Kitawasesoba and W/SK86GF. On the other hand, the stem diameter and number of flower clusters were larger in W/SK86 than in Kitawasesoba. In yield characteristics, little difference in total weight was observed between W/SK86GF and Kitawasesoba, whereas the yield, 1000 seed weight, and one litter weight of Kitawasesoba were higher than those of W/SK86GF.

Discussion

In this study, among the buckwheat varieties tested, the breaking tensile strength of green-flower buckwheat was greater than that of non-green-flower buckwheat. In addition, the breaking tensile strength of pedicel in green-flower plants was generally larger than that in white-flower ones in the F2 segregates, suggesting that pleiotropy or strong linkage existed between green-flower and strong pedicel (Mukasa et al. 2008). These results reinforce the idea that the green flower trait is promising as a shattering resistant trait. The pedicel diameter of W/SK86GF was thicker than that of Kitawasesoba (Fig. 1). This may be responsible for the increased breaking tensile strength in W/SK86GF. In production areas, buckwheat is generally harvested with a combine. The +15D is suitable for combine harvesting than the maturing time because of the lower water content in the stems and leaves. At +15D, about 95% of seed darkened in each plant (data not shown). This was supported by Miyamoto (1983), in which percentage of seed darkened changed from 80% to 95% for about 15 days. The point of 95% seed darkened is suitable for combine harvesting. Therefore, for the first step to evaluate shattering resistance, +15D is appropriate. From these result, low shattering seed weight of W/SK86GF at +15D shows promise for increasing the yield of buckwheat. In years without typhoons, the shattering seed ratios at +15D were lower than usual because the buckwheat was harvested carefully to prevent shattering. However, combine harvesting losses have been a significant problem in buckwheat production areas. Therefore, the increased breaking tensile strength of W/SK86GF even at +15D may contribute for the decrease of losses related to combine harvesting. The breaking tensile strength of the Russian green-flower varieties, green flower (2n) and green flower (4n), is also higher than that of non-green flower varieties. However, the yields of these varieties are about 20% and 45% of that of W/SK86GF (data not shown) in Hokkaido. Therefore, W/SK86GF is promising as a breeding material of shattering resistant buckwheat in Hokkaido. To develop a shattering resistant variety for practical use, further improvement of the breaking tensile strength is required because the breaking tensile strengths of major crops are generally much higher than those of buckwheat; for example, that of rice is about 150–250g (Ji et al. 2006). Agronomic characteristics of W/SK86GF such as yield, lodging resistance, 1000 seed weight and one litter weight are inferior to standard variety Kitawasesoba (Table 2). Therefore, improvement of them and quality evaluations of food such as buckwheat noodle are required.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr. T. Saruwatari, Mr. N. Murakami, Mr. S. Nakamura, Mr. K. Abe, Mr. T. Yamada, Mr. T. Takakura, Mr. M. Oizumi, Mr. T. Hirao and Mr. K. Suzuki for their assistance in the field. We also thank Mr. Y. Honda for his useful suggestions. In addition, we thank Ms. K. Fujii, Ms. M. Hayashida and Ms. T. Ando for their technical assistance. This work was supported in part by ‘Development of crop production technology for all year round multi-utilization of paddy fields’.

Literature Cited

- Alekseeva, E.S., Malikov, V.G., and Falendysh, L.G. (1988) Green-flower form of buckwheat. Fagopyrum 8: 79–82 [Google Scholar]

- Aufhammer, W., Fujimoto, F., and Yasue, T. (1994) Development and utilization of the seed yield potential of buckwheat (F. esculentum). Bodenkultur 45: 37–47 [Google Scholar]

- Awatsuhara, R., Harada, K, and Maeda, T (2010) Antioxidative activity of the buckwheat polyphenol rutin in combination with ovalbumin. Molecular Med. Rep. 3: 121–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura, Y., Oba, S, and Horiguchi, T (2001) Effects of fertilization and poliploidy on grain shedding habit of cultivated buckwheats (Fagopyrum spp.). Jpn. J. Crop Sci. 70: 221–225 [Google Scholar]

- Funatsuki, H., Maruyama-Funatsuki, W, Fujino, K, and Agatsuma, M (2000) Ripening habit of buckwheat. Crop Sci. 40: 1103–1108 [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, J.Q., Couch, J.F., and Lindauer, A (1944) Effect of rutin on increased capillary fragility in man. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 55: 228–229 [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda, K (2002) Buckwheat: composition, chemistry and processing. In: Taylor, S.L. (ed.) Advances in Food and Nutrition Research, Academic Press, Nebraska, USA, pp. 395–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji, H.S., Chu, S.H., Jiang, W.Z., Cho, Y.I., Hahn, J.H., Eun, M.Y., McCouch, S.R., and Koh, H.J. (2006) Characterization and mapping of a shattering mutant in rice that corresponds to a block of domestication genes. Genetics 173: 995–1005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, P., Burczynski, F, and Campbell, C (2007) Rutin and flavonoid contents in three buckwheat species Fagopyrum esculentum, F-tataricum, and F-homotropicum and their protective effects against lipid peroxidation. Food Res. Int. 40: 356–364 [Google Scholar]

- Kreft, I., Chang, K.J., Choi, Y.S., and Park, C.H. (2003) Ethnobotany of Buckwheat, Jinsol Publishing Co., Seoul, Korea, pp. 91–115 [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.H., Aufhammer, W., and Kubler, E. (1996) Produced, harvested and utilizable grain yield of the pseudocereals buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum, Moench), quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa, Wild) and amaranth (Amaranthus hypochondriacus, L × A. hybridus, L.) as affected by production techniques. Bodenkultur 47: 5–14 [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.Q., Zhou, F.C., and Gao, F (2009) Comparative evaluation of quer-cetin, isoquercetin and rutin as inhibitors of alpha-glucosidase. J. Agric. Food Chem. 57: 11463–11468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto, H. (1983) Relationships between seed yield, shattering and harvesting time in buckwheat. Report of the Hokkaido Branch, The Japanese Society of the Breeding and Hokkaido Branch, The Crop Science Society of Japan 23: 40 [Google Scholar]

- Morishita, T., Yamaguchi, H, and Degi, K (2007) The contribution of polyphenols to antioxidative activity in common buckwheat and Tartary buckwheat grain. Plant Prod. Sci. 10: 99–104 [Google Scholar]

- Mukasa, Y., Suzuki, T., and Honda, Y. (2008) Inheritance of green-flower trait and the accompanying strong pedicel in common buckwheat. Fagopyrum 25: 15–20 [Google Scholar]

- Oba, S., Ohta, A, and Fujimoto, F (1998a) Association between grain shattering habit and breaking strength of pedicel in buckwheat (Fagopyrum ssp.). Jpn. J. Crop Sci. 67: 76–77 [Google Scholar]

- Oba, S., Suzuki, Y, and Fujimoto, F (1998b) Breaking strength of pedicel and grain shattering habit in two species of buckwheat (Fagopyrum spp.). Plant Prod. Sci. 1: 62–66 [Google Scholar]

- Oba, S., Ohta, A, and Fujimoto, F (1999) Breaking strength of pedicel as an index of grain-shattering habit in autotetraploid and diploid buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench.) cultivars. Plant Prod. Sci. 2: 190–195 [Google Scholar]

- Shanno, R (1946) Rutin: A new drug for the treatment of increased capillary fragility. Am. J. Med. Sci. 211: 539–543 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieslander, G., Fabjan, N, Vogrincic, M, Kreft, I, Janson, C, Spetz-Nyström, U, Vombergar, B, Tagesson, C, Leanderson, P, and Norbäck, D (2011) Eating buckwheat cookies is associated with the reduction in serum levels of myeloperoxidase and cholesterol: A double blind crossover study in day-care center staffs. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 225: 123–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]