Abstract

The lipopeptidyl nucleoside antibiotics reperesented by A-90289, caprazamycin, and muraymycin, are structurally highlighted by a nucleoside core that contains a nonproteinogenic β-hydroxy-α-amino acid named 5′-C-glycyluridine (GlyU). Bioinformatic analysis of the biosynthetic gene clusters revealed a shared open reading frame encoding a protein with sequence similarity to serine hydroxymethyltransferases, resulting in the proposal that this shared enzyme catalyzes an aldol-type condensation with glycine and uridine-5′-aldehyde to furnish GlyU. Using LipK involved in A-90289 biosynthesis as a model, we now functionally assign and characterize the enzyme responsible for the C-C bond-forming event during GlyU biosynthesis as an l-threonine:uridine-5′-aldehyde transaldolase. Biochemical analysis revealed this transformation is dependent upon pyridoxal-5′-phosphate, the enzyme has no activity with alternative amino acids such as glycine or serine as aldol donors, and acetaldehyde is a co-product. Structural characterization of the enzyme product is consistent with stereochemical assignment as the threo diastereomer (5′S,6′S)-GlyU. Thus this enzyme orchestrates C-C bond breaking and formation with concomitant installation of two stereocenters to make a new l-α-amino acid with a nucleoside side chain.

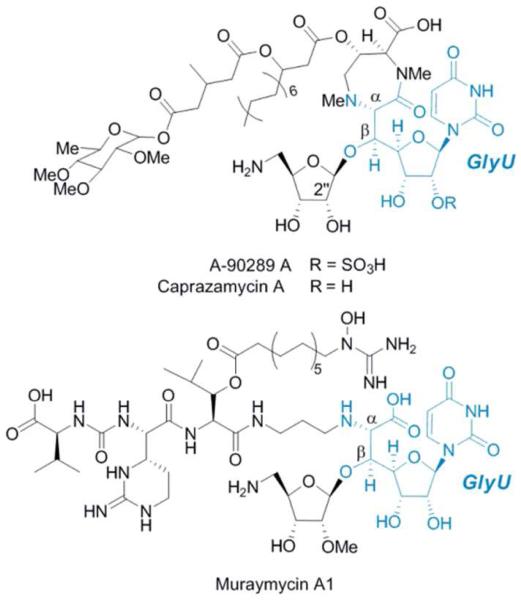

Several nucleoside antibiotics are structurally characterized with a furanose that is highly modified at C-5′ during biogenesis.1 Often this C-5′ modification process involves extension of the carbon chain to C6 or greater, and from isotopic enrichment studies on distinct families of these nucleoside antibiotics, it is generally believed that a C-C bond forming event—potentially by an aldol mechanism—is essential for converting the canonical nucleoside into a so-called high-carbon nucleoside scaffold. One family of lipopeptidyl nucleosides represented by A-90289s from Streptomyces sp. SANK 60405,3 caprazamycins from Streptomyces sp. MK730-62F,4 and muraymycins from Streptomyces sp. NRRL 30471.5, all of which have been discovered within the past decade based on inhibitory activity against bacterial translocase I, contain the high-carbon nucleoside 5′-C-glycyluridine (GlyU, 1).2 We now present the functional assignment of an l-Thr:uridine-5′-aldehyde transaldolase that catalyzes the amalgamation of an amino acid and nucleoside to form the β-hydroxy-α-amino acid (5′S,6′S)-1. The results establish the first known enzymatic strategy for generating high-carbon nucleoside scaffolds.

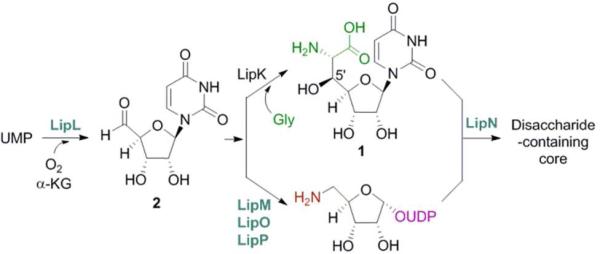

Within the past three years, the biosynthetic gene clusters for A-90289,6 caprazamycin,7 and muraymycin8 have been cloned, sequenced, and characterized. Bioinformatic analysis of these clusters revealed six shared open reading frames (orfs) including an orf encoding a putative serine hydroxylmethyltransferase (SHMT). SHMTs catalyze the reversible conversion of Gly to l-Ser using N5,N10-methylene tetrahydrofolate (THF) as a C1-unit donor and pyridoxal-5′-phosphate (PLP) as a cofactor (Figure S1A),9 and these enzymes have been shown to catalyze an aldol-type reaction with Gly and aldehydes to produce various β-hydroxy-α-amino acids in the absence of THF (THF-independent reaction) (Figure S1B).9,10 Thus, the unearthing of the SHMT homologues led to the proposal that 1 is formed by an aldol-type reaction between uridine-5′-aldehyde (2) and Gly (Figure 2). In vivo studies using gene inactivation within the producing strains of A-902896 and muraymycin8 have revealed this SHMT-like orf—lipK for A-90289 biosynthesis—is essential for biosynthesis, and in vitro studies have revealed the pathway intermediacy of 2 upon functional characterization of a non-heme, Fe(II)-dependent α-ketoglutarate (αKG):UMP dioxygenase (LipL) (Figure 2).11 The remaining four, shared orfs were found to be essential for the assembly of the aminoribosyl moiety starting from 2, overall suggesting a possible biosynthetic pathway that diverges at 2 and, following downstream enzymatic transformations, re-converges to form the β(1→5) disaccharide-containing core (Figure 2).12

Figure 2.

Biosynthesis of the disaccharide-containing nucleoside core of lipopeptidyl nucleoside antibiotics. Enzymes in blue have been functionally assigned while the LipK-catalyzed reaction is proposed.

In order to complete the biosynthetic pathway of the disaccharide-containing core and characterize the elementary steps for the biosynthesis of the high-carbon skeleton, we aimed to define the role of the SHMT homologues using LipK as a model enzyme. Overall LipK and these homologues have a low sequence similarity to bona fide SHMTs from bacterial sources (20-23% sequence identity) (Figure S2). Nevertheless, several residues considered critical for activity, most importantly the Lys responsible for formation of an internal aldimine with PLP, are conserved. Heterologous expression of lipK in E. coli proved unfruitful, however soluble LipK was obtained using Streptomyces lividans TK64 (Figure S3A). As controls, wild-type LipK was also produced in Streptomyces albus, and a mutant protein, LipK(K235A), was prepared with the expectation that this point mutation would yield an enzyme that is unable to form an internal aldimine with PLP that is a prerequisite for catalytic activity (Figure S3B,C). Additionally, recombinant E. coli SHMT (EcGlyA) and E. coli l-Thr aldolase (EcLTA, EC 4.1.24), the latter of which is also involved in β-hydroxy-α-amino acid metabolism by catalyzing the reversible conversion of l-Thr to Gly and acetaldehyde (Figure S1C) and is widely used as a biocatalyst to generate various unnatural β-hydroxy-α-amino acids,10,13 were also produced to serve as controls (Figure S3D,E).

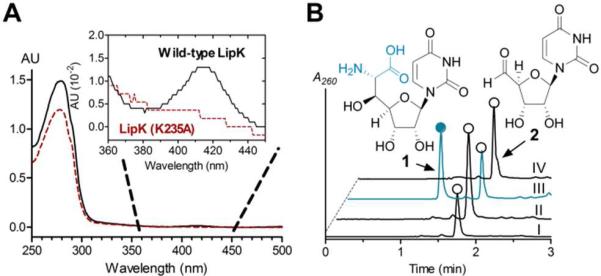

The consensus reaction coordinate of SHMT and LTA involves initial binding of PLP to form an internal aldimine (holo-enzyme) followed by amino acid binding to give an external aldimine, both species of which have a characteristic UV maximum near 425 nm (Figure S4A).14,15 LTA immediately proceeds to a quininoid intermediate upon abstraction of the Cα proton of Gly resulting in a bathochromic shift to a UV maximum of 492 nm, and the UV/Vis profile for SHMT undergoes a comparable shift to 500 nm but only following additional binding of THF to form a ternary complex (Figure S4A). As predicted, all of the proteins had UV/Vis spectra consistent with purification with bound PLP; LipK from both S. lividans TK64 and S. albus had a UVmax at 416 nm that was absent in the LipK(K235A) mutant (Figure 3A and Figure S5B), EcLTA at 421 nm (Figure S4C), and EcGlyA at 425 nm (Figure S4D). In contrast to LipK and EcGlyA, a new UVmax appeared for EcLTA at 492 nm upon the addition of Gly (Figure S4C), and when THF was also added to EcGlyA, the expected UVmax shift to 500 nm was observed (Figure S4D), both consistent with quininoid formation. However, exposing LipK to any combination of hypothetical substrates did not alter the UV spectrum (Figure S4E), suggesting that LipK has unique catalytic properties relative to EcGlyA and EcLTA.

Figure 3.

Functional Assigment of LipK. (A) UV/Vis spectra of recombinant LipK and point mutant isolated from S. lividans TK64. (B) HPLC analysis of the reaction catalyzed by LipK using 2 with co-substrate Gly or Ser (I), l-Thr without exogenous PLP (II), l-Thr (III), and l-Thr with LipK (K235A) (IV). AU, absorbance units; A260, absorbance at 260 nm.

We next tested the activity of LipK with 2 and Gly or other potential l-amino acid co-substrates. HPLC analysis revealed the appearance of a new peak using l-Thr, and the formation of the new peak was dependent upon enzyme and PLP (Figure 3B). In contrast, substitution of l-Thr with other amino acids or using the LipK (K235A) mutant protein resulted in no detectable activity (Figure 3B). Further analysis of the PLP-dependency revealed product formation without exogenous PLP following extended incubation times or addition of excess LipK (Figure S5), consistent with the UV spectroscopic analysis that suggests a fraction of LipK is purified as the holo-enzyme. Interestingly, using conditions wherein 2 is completely converted to product by LipK, trace amounts of a new product were observed with EcLTA and EcGlyA using l Thr as an aldol acceptor, yet no new peaks were detected using Gly (Figure S6).

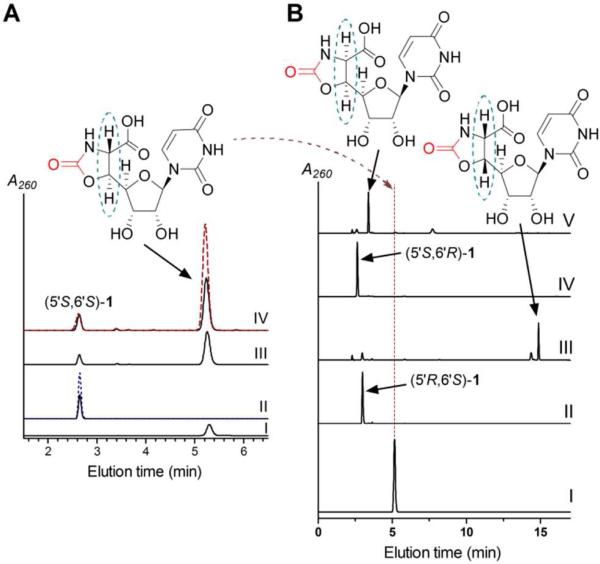

The new, UV-active product was collected and purified, and LC-MS analysis revealed an (M - H)- ion at m/z = 315.9, consistent with the molecular formula C11H13N3O8 of 1 (expected m/z = 316.1) (Figure S7). HR-ESI-MS and 1D and 2D NMR spectroscopic analysis, in comparison to synthetic (5′S,6′S)-1, was consistent with the identity of the expected product (Figure S7-S10). Phosgene modification, which generates 2-oxazolidones from β-amino alcohols without alteration of the stereochemistry of the starting material,16 of both synthetic and enzymatic 1 followed by HPLC (Figure 4A and S11) and NMR analysis (Figure S12-S14) revealed—among other important diagnostic attributes—a JH6′-H5′ = 5.0 Hz, which is consistent with the stereochemical assignment for the threo diastereomer, (5′S,6′S)-1.17 Furthermore, synthetically prepared 5′- and 6′-epimers of 1 were both spectroscopically and chromatographically different from the product of the LipK reaction (Figure 4B), thus providing further support of the stereochemistry.

Figure 4.

Comparative analysis of enzymatic and synthetic 1 diastereomers. (A) HPLC analysis of pure phosgene-modified (5′S,6′S)-1 that was prepared by enzymatic synthesis and confirmed by NMR spectroscopy (I), (5′S,6′S)-1 prepared by chemical synthesis (black, solid line) and spiked with an equimolar amount of enzymatic (5′S,6′S)-1 (blue, dashed line) (II), crude mixture of (5′S,6′S)-1 that was prepared by enzymatic synthesis and modified with phosgene (III), crude mixture of (5′S,6′S)-1 that was prepared by chemical synthesis and modified with phosgene (black, solid line) and spiked with authentic, enzymatically produced phosgene-modified (5′S,6′S)-1 (red, dashed line) (IV). (B) HPLC analysis of pure phosgene-modified (5′S,6′S)-1 (I), synthetic (5′R,6′S)-1 (II), phosgene-modified (5′R,6′S)-1 (III), synthetic (5′S,6′R)-1 (IV), and phosgene-modified (5′S,6′R)-1 (V). A260, absorbance at 260 nm.

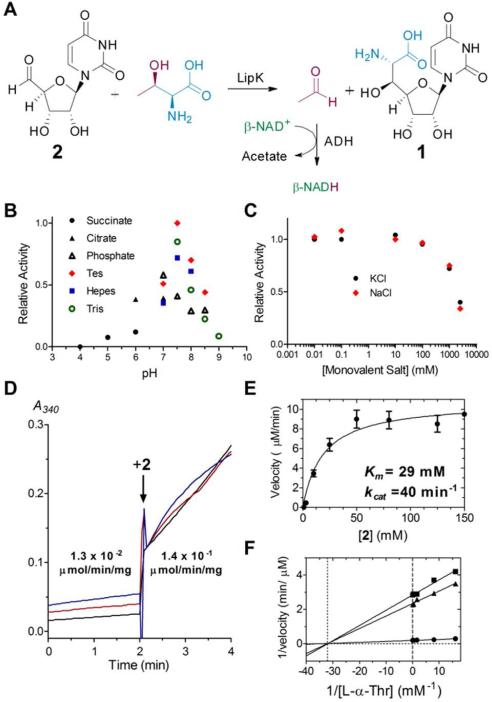

The identification of (5′S,6′S)-1 as the UV-active product suggested acetaldehyde was concomitantly formed during the reaction. To confirm this, we performed LipK reactions under conditions wherein ~ 40% of 2 was converted to (5′S,6′S)-1, and the reactions were quenched with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine under acidic conditions.18 Using acetaldehyde in place of 2 and authentic acetaldehyde-2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine as controls, acetaldehyde was confirmed as the second product of LipK (Figure S15). In total, the data are consistent with the functional assignment of LipK as a PLP-dependent l-Thr:2 transaldolase that generates acetaldehyde and (5′S,6′S)-1 (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Characterization and kinetic analysis of LipK. (A) The LipK-catalyzed reaction and coupling with aldehyde dehydrogenase (ADH). (B) pH profile (C) Activity with variable monovalent salts. (D) UV/Vis spectroscopic analysis of the l-Thr retro-aldol-type reaction catalyzed by LipK in the absence or presence of 10 mM 2. Each line represents an independent reaction with 2 added at the indicated time. A340, absorbance at 340 nm. (E) Single-substrate kinetic analysis with 30 mM l-Thr and variable 2. (F) Bisubstrate kinetic analysis using 1 mM (■), 3 mM (▲), and 60 mM (•) 2.

Finally, we established the specificity and biochemical properties of LipK. Using HPLC for product detection, LipK was shown to be inactive with commercially available l-Thr diastereomers and various Thr analogues (Figure S16), demonstrating the high specificity for l-Thr. Under initial velocity conditions, the pH profile for LipK was shown to resemble a bell-shaped curve with optimal activity at pH 7.5 (Figure 5B), and monovalent ions yielded only a slight change in activity up to concentrations of 100 mM, above which the activity decreased (Figure 5C). After optimizing the conditions for activity by HPLC, we developed a facile and robust assay for this enzyme activity that is amenable to kinetic analysis by taking advantage of the formation of acetaldehyde, which is an efficient substrate for Saccharomyces cerevisiae aldehyde dehydrogenase (ADH, EC 1.2.1.3) isozymes that couple acetaldehyde oxidation with the reduction of β-NAD+ (Figure 5A).19 Using optimal conditions for ADH activity, we first ensured that components necessary for each enzyme did not affect the activity of the respective enzyme (Figure S17). Subsequently, using the coupled assay LipK, EcLTA, and EcGlyA were shown to catalyze a retro-aldol-type reaction in the presence of only l-Thr, yielding specific activities of (1.3 ± 0.2) × 10-2, 1.2 ± 0.2, and (5.7 ± 0.4) × 10-4 μmol/min/mg, respectively (Figure 5D and Figure S18). Nevertheless, the rate of the retro-aldol reaction catalyzed by LipK was significantly enhanced upon addition of an equimolar amount of 2 (Figure 5D). Single-substrate kinetic analysis of LipK revealed typical Michaelis-Menten kinetics with respect to varied 2, yielding kinetic constants of Km = 29.2 ± 9.5 mM and kcat = 40 ± 4 min-1 (Figure 5E). The high Km for 2 precluded an accurate single-substrate kinetic analysis with respect to varied l-Thr. Bisubstrate kinetic analysis was consistent with LipK employing a sequential mechanism reminiscent of bona fide SHMTs despite the realization that acetaldehyde is produced in the absence of 2 (Figure 5F).20

The newly discovered LipK family of l-Thr:2 transaldolases now joins 4-fluorothreonine transaldolase (FTase) as putative SHMTs that instead catalyze a l-Thr-dependent β-substitution reaction via sequential Cα-Cβ bond breaking and creation (Figure S19A).21,22 Unlike FTase, which is a didomain protein with an SHMT-like and sugar epimerase/aldolase domain (Figure S19B), LipK is a single domain protein, and it is now clear that the transaldolase activity for both resides in this SHMT-like domain despite sharing only 25% sequence identity in this region. Additionally, the observation of a potential transaldolase activity with EcGlyA and EcLTA, again despite the low sequence similarity with LipK, suggests the l Thr-dependent transaldolase reaction may be more common than currently appreciated, which is also intimated by the genetic redundancy of annotated SHMTs per genome such as the five within Streptomyces clavuligerus ATCC 27064.

Perhaps the most intriguing realization with the discovery of LipK activity is that it provides another, distinct mechanism for extending the carbon chain of sugars. Hitherto this process is known to occur by aldolase or transketolase enzymes, which employ a carbonyl-group-containing substrate—typically a ketone group for aldolases—as the donor.23 LipK on the other hand uses an amino acid as a donor to yield a β-sugar substituted α-amino acid. Given that aldolases and transkelose enzymes have served as valuable tools in biocatalytic synthesis to generate complex natural and unnatural sugars, the l-Thr transaldolase activity uncovered here may provide a new biotechnological platform to prepare previously inaccessible sugars as well as unusual amino acids that is exemplified by 1.

In summary we have identified an enzyme catalyst, l-Thr:2 transaldolase, that is integral for amalgamating amino acids and nucleosides into antibiotics. Mechanistically, this is an intriguing transformation (Figure S20), and the results described here provide the foundation for future in depth mechanistic studies. Furthermore, the unearthing of this activity finally provides an enzymatic imperative for formation of high-carbon nucleosides, which is likely utilized in other biosynthetic systems.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Structures of specified congeners of lipopeptidyl nucleoside antibiotics containing the nonproteinogenic β-hydroxy-α-amino acid, GlyU.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant AI087849 and the Kentucky Science and Education Foundation (S. V. L.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Experimental procedures, supporting figures, spectroscopic data, and complete reference 11. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Isono K. Pharmacol. Ther. 1991;52:269. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(91)90028-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winn M, Goss RJ, Kimura K, Bugg TD. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2010;27:279. doi: 10.1039/b816215h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujita Y, Kizuka M, Funabashi M, Ogawa Y, Ishikawa T, Nonaka K, Takatsu T. J. Antibiot. 2011;64:495. doi: 10.1038/ja.2011.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Igarashi M, Takahashi Y, Shitara T, Nakamura H, Naganawa H, Miyake T, Akamatsu Y. J. Antibiot. 2005;58:327. doi: 10.1038/ja.2005.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDonald LA, Barbieri LR, Carter GT, Lenoy E, Lotvin J, Petersen PJ, Siegel MM, Singh G, Williamson RT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:10260. doi: 10.1021/ja017748h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Funabashi M, Baba S, Nonaka K, Hosobuchi M, Fujita Y, Shibata T, Van Lanen SG. Chembiochem. 2010;11:184. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaysser L, Lutsch L, Siebenberg S, Wemakor E, Kammerer B, Gust B. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:14987. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M901258200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng L, Chen W, Zhai L, Xu D, Huang T, Lin S, Zhou X, Deng Z. Mol. Biosyst. 2011;7:920. doi: 10.1039/c0mb00237b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schirch L, Gross T. J. Biol. Chem. 1968;243:5651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gutierrez ML, Garrabou X, Agosta E, Servi S, Parella T, Joglar J, Clapés P. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:4647. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Z, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:7885. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.203562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chi X, Pahara P, Nonaka K, Van Lanen SG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:14452. doi: 10.1021/ja206304k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimura T, Vassilev VP, Shen GJ, Wong CH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:11734. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Contestabile R, Paiardini A, Pascarella S, di Salvo ML, D'Aguanno S, Bossa F. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001;268:6508. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schirch V, Hopkins S, Villar E, Angelaccio S. J. Bacteriol. 1985;163:1. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.1.1-7.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishimaru T. Nippon Kagaku Zasshi. 1960;81:1589. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saeed A, Young DW. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:2507. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartos J, Pesez M. Pure & Appl. Chem. 1979;51:1803. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X, Mann CJ, Bai Y, Ni L, Weiner H. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:822. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.4.822-830.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schirch LV, Tatum CM, Jr., Benkovic SJ. Biochemistry. 1977;16:410. doi: 10.1021/bi00622a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murphy CD, O'Hagan D, Schaffrath C. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001;40:4479. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011203)40:23<4479::aid-anie4479>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deng H, Cross SM, McGlinchey RP, Hamilton JT, O'Hagan D. Chem. Biol. 2008;15:1268. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takayama S, McGarvey GJ, Wong C-H. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1997;51:285. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.