Abstract

Culturally-specific HIV risk reduction interventions for Hispanic women are needed. SEPA (Salud/Health, Educación/Education, Promoción/Promotion, y/ and Autocuidado/Self-care) is a culturally-specific and theoretically-based group intervention for Hispanic women. The SEPA intervention consists of five sessions covering STI and HIV prevention; communication, condom negotiation and condom use; and violence prevention. A randomized trial tested the efficacy of SEPA with 548 adult U.S. Hispanic women (SEPA n = 274; delayed intervention control n = 274) who completed structured interviews at baseline and 3, 6, and 12 months post-baseline. Intent-to-treat analyses indicated that SEPA decreased positive urine samples for Chlamydia; improved condom use, decreased substance abuse and IPV; improved communication with partner, improved HIV-related knowledge, improved intentions to use condoms, decreased barriers to condom use, and increased community prevention attitudes. Culturally-specific interventions have promise for preventing HIV for Hispanic women in the U.S. The effectiveness of SEPA should be tested in a translational community trial.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Hispanic, Women, Condom use, Sex risk

Introduction

Although the U.S. is less affected from the feminization of HIV as other regions in the world (e.g., Africa and India), the incidence of HIV has remained relatively stable over the past 10 years among women, indicating little progress in curbing the epidemic among this population [1, 2]. Hispanic women in the U.S. are particularly at risk for HIV infection. In 2006 the incidence of HIV infection among Hispanic women was almost four times that of their white female counterparts, with heterosexual intercourse being the most common mode of transmission [3]. Various factors increase HIV risk for Hispanic women, including socioeconomic factors such as high rates of poverty and unemployment [4], high rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) [3], immigration and acculturation stress [5], and cultural values (e.g., machismo and marianismo) that promote inequitable gender norms that make it difficult for women to negotiate safer sexual practices [6–8]. These culturally-specific risk, along with other generic risk factors for HIV such as a being unaware of their partner’s HIV status and/or risk, substance abuse, poor mental health, and history of violence victimization [9, 10], create a unique configuration for HIV risk among Hispanic women.

The feminization of HIV infection and the ethnic diversification of women in the U.S. have led to a call for the development and evaluation of gender- and culturally-specific HIV prevention strategies [1, 11, 12]. However, few studies have reported the efficacy of HIV prevention programs targeting Hispanic women in the U.S. This is particularly true for HIV prevention programs targeting community-dwelling Hispanics, a hard-to-reach population who appear to be the racial/ethnic group in the U.S. with the lowest utilization rates for health care services [13]. Consequently, in order to make progress in decreasing the incidence of HIV among Hispanic women, community-based interventions need to be developed, tested, and disseminated. This paper reports on the effects of a culturally-specific, community-based HIV risk reduction program for Hispanic adult women.

HIV Disparities Among Hispanic Women

Hispanics are overrepresented in new HIV infections. In fact, while Hispanics comprised 15% of the U.S. population in 2006, they accounted for 17% of new HIV infections [3]. Disparities in newly acquired HIV infection are more striking when Hispanics are stratified according to gender. Although Hispanic men make up the majority of new infections among Hispanics (76%) and have an incidence of HIV twice that of non-Hispanic White men (43/100,000 vs. 20/100,000), Hispanic women have an HIV incidence of HIV four times that of non-Hispanic White women (14.4/100,000 vs. 3.8/100,000) [3]. The co-occurrence of HIV with other behaviorally rooted conditions such as substance abuse, STIs, and intimate partner violence (IPV) further contribute to the disparities in morbidity and mortality experienced by Hispanic women [7–10].

There are various biological, behavioral and sociocultural factors that contribute to HIV related health disparities experienced by Hispanic women. First, the incidence of STIs is high among Hispanics, making easier for Hispanics who are infected with a STI to transmit and acquire HIV [3]. Hispanic women are most likely to acquire HIV through heterosexual intercourse with a male partner, making unprotected sex a key behavior to address through prevention efforts [3]. Nevertheless, culturally ascribed gender roles regarding masculinity (machismo) and femininity (marianismo), make it difficult for Hispanic women to negotiate condom use with their male partners [6–8]. For example, in a study exploring HIV risk among Hispanic immigrants, female participants were reluctant to discuss condom use and did not expect their partners to use them [5]. This may be because culturally desirable values that promote women being like the Virgin Mary (marianismo) and therefore asexual, obedient and submissive, make the negotiation of condoms socially unacceptable [6]. Additionally, a low HIV risk perception and the acculturation process, whereby changes in HIV-related knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors are experienced by Hispanic women, further contribute to the vulnerability of this population [3]. Culturally-specific HIV prevention programs are therefore needed to address the unique context of this group.

HIV Prevention for Hispanic Women

There are six best-evidence HIV prevention programs for Hispanics listed under the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Compendium of Evidence-Based HIV Prevention Interventions [14]. Only two of these interventions, Project Connect [15] and the Women’s Health Promotion [16, 17] intervention targeted community-dwelling Hispanic women outside of drug or STI treatment centers. Project Connect is an HIV prevention program targeting inner-city minority heterosexual couples that aims to increase safer sex practices and relationship communication among couples [15]. The intervention was implemented in a hospital outpatient clinic and delivered over six, 2-h sessions. Although the intervention resulted in an increase in protected vaginal sexual acts among participants, only 39% of participants were of Hispanic origin and authors did not report on effects according to ethnicity. Further, authors noted that the lack of inclusion of biological indicators of risk for HIV (e.g., STI) was an important limitation of the study.

The Women’s Health Program [16, 17] is the only program in the CDC Compendium of Evidence-Based HIV Prevention Interventions that specifically targeted and evaluated effects for Hispanic adult, community-dwelling women [14]. The intervention consisted of 12, 90- to 120-min group sessions implemented in a community clinic that aimed to eliminate or reduce sexual risk behaviors. The intervention was efficacious in increasing condom use with their primary partner at the 3-month follow-up, but these effects were no longer significant during the 15-month follow-up period. Further, biological risk for HIV was not evaluated, making it difficult to assess the impact that these behaviors may have had on health outcomes.

There have been 4 other interventions specifically developed for adult Hispanic women that have been formally evaluated and reported in the literature [18–21]. These interventions vary in aims, structure, content, and length. The Centro San Bonifacio HIV Prevention Program followed a community health worker approach to increase HIV knowledge and self-perception of risk through engaging community members in one educational session that was delivered in different settings and formatted according to the needs of the audience [18]. Effects on HIV knowledge and self-perception were noted by the investigator. Nevertheless, behavioral and biological outcomes were not evaluated. The other interventions included health promotion programs comprised of a number of structured psychoeducational group sessions consisting of knowledge and skills-building activities. These varied in length from three 2.5-h sessions [19] to six 2-h sessions [20]. SEPA (Salud/Health, Educacion/Education, Prevencion/Prevention, Autocuidado/Self-care) was the only one of these interventions that increased condom use, as shown in a previous randomized trial [20].

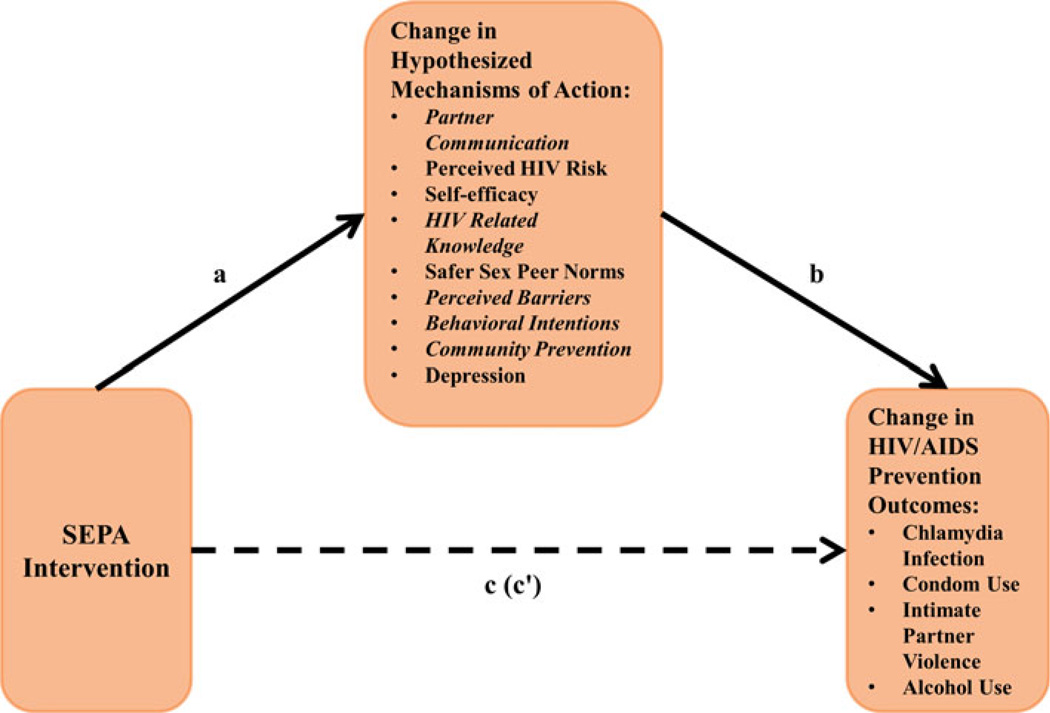

SEPA is an evidence-based HIV risk reduction intervention initially designed for low-income Mexican and Puerto Rican women in Chicago, IL [20]. In the current trial described in this paper, SEPA was adapted for the diverse community of Hispanic women in South Florida through a mixed-method study that identified the need to address substance abuse and intimate partner violence (IPV) [7, 22]. SEPA was further adapted by reducing the number of sessions from six to five. This decision was made based on the difficulty of keeping this population engaged in behavioral interventions over long periods of time [23] and evidence from the previous trial that the participation of five of the six sessions SEPA sessions were enough to lead to decrease risk for HIV [20, 23]. SEPA is informed by the social cognitive theory of behavior change and was designed to be consistent with Hispanic cultural values [20, 24]. As such, SEPA targets changes in an array of beliefs and skills related to reducing sexual risk. Group facilitators used multiple approaches: hands-on activities, role playing (e.g., negotiating condom use), skill demonstration (e.g., correct condom use, assertive communication), homework to build self-efficacy (e.g., educating peers about sexual risk and condom use), and direct provision of information (e.g., HIV/STD knowledge, links between alcohol use and sexual risk). Figure 1 shows the theoretical mechanisms of action in SEPA.

Fig. 1.

Theoretical model of mechanisms of action in SEPA. Path of intervention to change in mediator = a. Path of change in mediator to change in outcome = b. Indirect effect = a * b. Intervention effect without controls (total effect) = c. Intervention effect after controlling for the indirect effect (mediated or direct effect) = c′. Variable names in italics in the indicate hypothesized mediator variables that showed a statistically significant intervention effect in initial analyses, and were included separately in the subsequent mediation analyses

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of SEPA on biological, behavioral, social cognitive risk for HIV and community prevention over a 1 year follow-up period. Further, this study examined possible mediators of intervention effects on condom use. The following hypotheses were tested: (1) Women in the intervention group (SEPA) will have greater reductions in biological risk (i.e., Chlamydia infection rates) than the control group. (2) Women in the intervention group will have greater improvements in behavioral risks (i.e., condom use, intimate partner violence, and getting drunk) than the control group. (3) Women in the intervention group will have greater improvements in social-cognitive/community prevention variables (e.g., partner communication, HIV-related knowledge, perceived HIV risk, and self-efficacy) than the control group. (4) Social cognitive/community prevention will mediate the intervention effect on condom use. That is, there will be a significant indirect effect from treatment condition to change in the proposed mediator (social cognitive/community prevention variables) to change in condom use.

Methods

Design and Procedures

A randomized controlled experimental study with adult Hispanic women in Miami-Dade and Broward counties compared SEPA to a delayed intervention control group. Participants were assessed at baseline and 3-, 6-, and 12-months post-baseline between January 2008 and April 2010. Participants were recruited through the distribution of flyers and outreach at public places where Hispanic women go frequently (e.g., churches, supermarkets, community organizations). Recruitment efforts were targeted in areas close to the study office locations in the downtown area of Miami-Dade, and in a neighborhood in Broward County that has a high proportion of Hispanic immigrants. After recruitment and informed consent, women were interviewed in their preferred language by trained bilingual (Spanish and English) female research staff using a standardized protocol and a structured interview. Interviews (about 2 h) were conducted in private offices at or near community service agencies. Assessments were collected with a secure web-based research management software system (e-Velos) that allowed assessors to ask participants questions and document their responses on the computer. Assessors were not blinded to the study condition. Participants were compensated $50 per interview and $20 per SEPA session. Strategies for retention included obtaining contact information for multiple participant contacts, offering interviews at convenient and trusted sites, and using multiple mail and telephone communications.

Sample

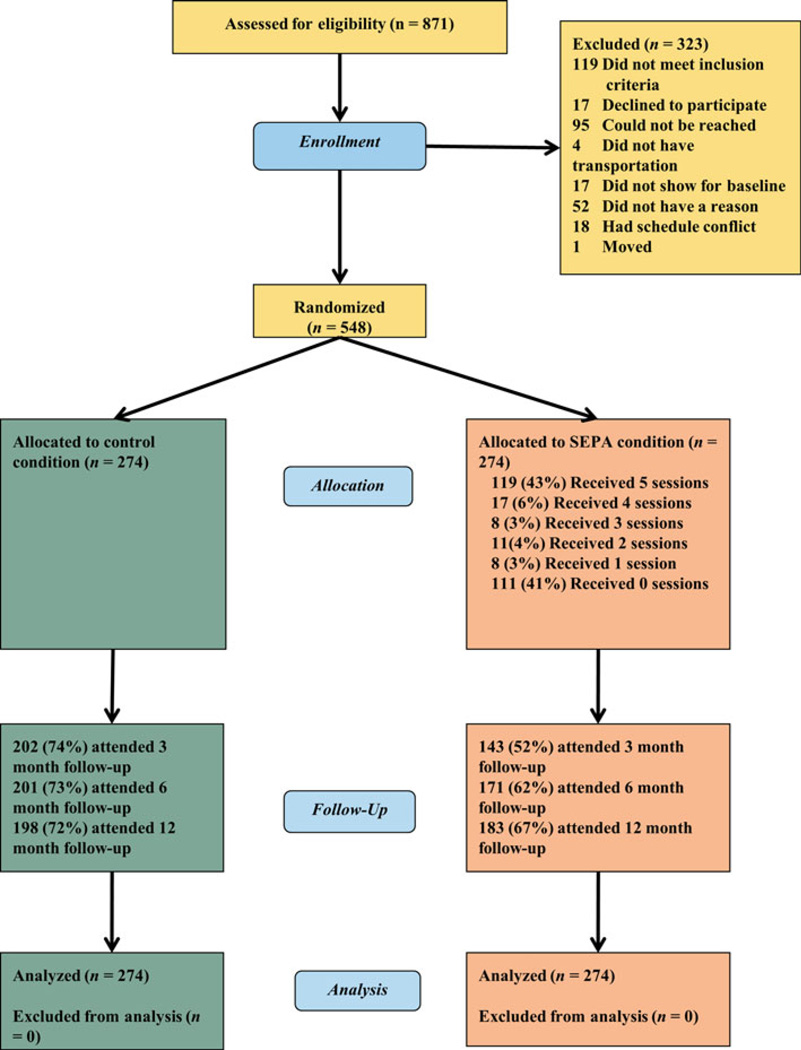

Eligibility criteria were: self-identifying as Hispanic, being between 18 and 50 years old, and reporting sexual activity in the last 3 months. In total 872 women were screened, 119 of whom were not eligible (14%) and 204 of whom were excluded for various reasons (Fig. 2). A total of 548 women (63%) were randomized using a permuted-block randomization procedure. There were no significant baseline differences in demographics (Table 1) or outcomes (Table 2) between conditions. A plurality of women were born in Colombia (34%), 13% in Cuba, 8% in Peru, 8% in the U.S., 6% in the Dominican Republic, and 5% or fewer women were born in one of eleven other nations.

Fig. 2.

CONSORT subject flow diagram

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of women in the control and SEPA conditions

| Characteristic | Control (n = 274) M (SD) |

SEPA (n = 274) M (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 38.22 (8.73) | 38.74 (8.32) |

| Education in years | 13.11 (3.51) | 13.62 (3.38) |

| Years in U.S. | 10.99 (9.88) | 11.84 (10.78) |

| Americanism | 2.32 (0.80) | 2.40 (0.79) |

| Hispanicism | 3.55 (0.44) | 3.53 (0.44) |

| Number of sexual partners (past 3 months) | 1.08 (0.45) | 1.11 (0.65) |

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Employed | 88 (32) | 92 (34) |

| Monthly income <$2000/month | 185 (68) | 196 (72) |

| Born outside of U.S. | 251 (92) | 256 (93) |

| Living w/ partner | 199 (73) | 181 (66) |

| Has health insurance | 114 (42) | 92 (34) |

Table 2.

Magnitude (OR) of difference in outcomes at every assessment for women in the control and SEPA conditions

| Outcome | Baseline | 3-month | 6-month | 12-month | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control n % |

SEPA n % |

χ2 | P | OR | Control n % |

SEPA n % |

χ2 | P | OR | Control n % |

SEPA n % |

χ2 | P | OR | Control n % |

SEPA n % |

χ2 | P | OR | |

| Biological | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Chlamydia infectiona | 3 | 1 | 1.06 | .30 | 0.32 | – | – | –b | 0 | 1 | 1.20 | .27 | –b | 3 | 1 | 0.8 | .37 | 0.37 | ||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Behavioral | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Condom use | 104 | 96 | 0.50 | .48 | 0.88 | 65 | 55 | 1.46 | .23 | 1.32 | 76 | 64 | 0.01 | .94 | 0.98 | 69 | 89 | 7.45 | .01 | 1.77 |

| 38 | 35 | 32 | 39 | 38 | 37 | 35 | 49 | |||||||||||||

| Domestic violence | 166 | 184 | 2.56 | .11 | 1.33 | 102 | 74 | 0.11 | .74 | 0.93 | 89 | 73 | 0.37 | .54 | 1.14 | 83 | 64 | 2.99 | .08 | 1.45 |

| 61 | 67 | 51 | 53 | 46 | 43 | 45 | 36 | |||||||||||||

| Got drunk | 25 | 37 | 2.62 | .11 | 1.56 | 17 | 8 | 1.03 | .31 | 0.64 | 10 | 12 | 0.69 | .41 | 1.44 | 10 | 5 | 1.35 | .25 | 0.53 |

| 9 | 14 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 3 | |||||||||||||

| Social-cognitive and community prevention | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Partner comm. | 185 | 175 | 0.62 | .43 | 0.87 | 108 | 92 | 4.02 | .04 | 1.58 | 79 | 83 | 2.44 | .12 | 1.39 | 76 | 80 | 1.14 | .29 | 1.27 |

| 68 | 65 | 55 | 66 | 41 | 49 | 47 | 53 | |||||||||||||

| Perceived HIV risk | 63 | 47 | 2.91 | .09 | 0.69 | 17 | 15 | 0.43 | .51 | 1.28 | 16 | 15 | 0.09 | .77 | 1.12 | 16 | 13 | 0.13 | .72 | 0.87 |

| 23 | 17 | 8 | 11 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 7 | |||||||||||||

| Self-efficacy | 78 | 74 | 0.24 | .63 | 0.91 | 78 | 57 | 0.03 | .86 | 1.04 | 95 | 86 | 0.25 | .62 | 1.11 | 119 | 93 | 3.12 | .08 | 0.69 |

| 28 | 27 | 39 | 40 | 48 | 51 | 60 | 51 | |||||||||||||

| HIV knowledge | 88 | 98 | 0.81 | .37 | 1.18 | 98 | 88 | 5.72 | .02 | 1.70 | 76 | 102 | 17.66 | <.001 | 2.43 | 105 | 107 | 1.14 | .29 | 1.32 |

| 32 | 36 | 49 | 62 | 38 | 60 | 53 | 59 | |||||||||||||

| Behavioral intentions | 165 | 155 | 0.75 | .39 | 0.86 | 129 | 102 | 2.11 | .15 | 1.41 | 153 | 134 | 0.18 | .67 | 1.11 | 162 | 144 | 0.59 | .44 | 0.82 |

| 60 | 57 | 64 | 71 | 77 | 78 | 82 | 79 | |||||||||||||

| Safer sex peer norms | 85 | 68 | 1.58 | .21 | 0.78 | 69 | 44 | 0.84 | .36 | 0.80 | 70 | 61 | 0.01 | .91 | 1.03 | 63 | 59 | 0.03 | .86 | 0.96 |

| 31 | 25 | 37 | 32 | 37 | 38 | 34 | 33 | |||||||||||||

| Perceived barriers | 14 | 13 | 0.04 | .84 | 0.86 | 18 | 1 | 10.85 | .001 | 0.07 | 3 | 1 | 0.72 | .40 | 0.39 | 5 | 5 | 0.02 | .90 | 1.08 |

| 5 | 5 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | |||||||||||||

| Community prevention | 162 | 112 | 0.12 | .73 | 0.94 | 55 | 88 | 9.12 | .003 | 1.95 | 68 | 103 | 19.45 | <.001 | 2.55 | 88 | 95 | 1.35 | .25 | 1.27 |

| 51 | 41 | 33 | 62 | 35 | 60 | 45 | 52 | |||||||||||||

| Depression | 127 | 129 | 0.03 | .86 | 1.03 | 76 | 57 | 0.18 | .67 | 1.10 | 67 | 58 | 0.01 | .91 | 1.03 | 55 | 53 | 0.07 | .80 | 1.06 |

| 46 | 47 | 38 | 40 | 33 | 34 | 28 | 29 | |||||||||||||

No test for Chlamydia at 3-months.

OR not defined for groups of zero. Significant comparisons in bold

Sample Size Determination

Most effect sizes from the previous SEPA trial [15] were in the medium to large range [25]. However, intervention effects on condom use were smaller (d = 0.17). Assuming a 70% retention rate over the course of the study, N = 548 gives sufficient power (>.80) to detect an effect of this size (d = 0.17).

Intervention

SEPA is an HIV risk reduction intervention for Hispanic women. SEPA’s conceptual framework integrates the social-cognitive model of behavioral change [24] and Freire’s pedagogy [26]. The social-cognitive model drove the content and activities of the session, which included structured activities that would promote self-efficacy (e.g., condom use demonstration, communication activities). Freire’s pedagogy drove the delivery and contextual tailoring of SEPA by establishing the importance of every individual in the group contributing to the knowledge and skills that were generated during the session and providing an atmosphere that encouraged participants to engage in discussion and activities. SEPA consisted of five, 2-h sessions delivered in small groups (M = 4.79 women, SD = 1.97); 163 (60%) women attended at least 1 session, with 119 (73%) of those attending all sessions. Sessions covered HIV/AIDS in the Hispanic community, STIs, HIV/AIDS prevention (e.g., condom use), negotiation and communication with the partner, IPV and substance abuse. Five bilingual and bicultural Hispanic female facilitators with a range of education (bachelors to doctoral) delivered the intervention. Groups were conducted in English or Spanish according to the language with which participants expressed they felt most comfortable. Groups took place in community sites easily accessible to participants. Role play, participatory sessions, videos and discussions were used to build skills. At the 6-month follow-up, women in SEPA were invited to a booster session to discuss topics related to the HIV intervention. In total, there were 14 booster sessions offered. A small proportion (n = 31, 11%) of the participants randomized to the intervention condition attended these boosters. The control group received a one-session, condensed version of SEPA after their 12-month assessment. Fidelity was ensured through a facilitator training, intervention manual and standardized PowerPoint presentations that would assist the facilitator in covering the content and activities during each session. The PI of the study also conducted unannounced visits to groups led by each of the facilitators to assess and address fidelity.

Measures

All measures had been used with Hispanic samples from previous research and were available in Spanish and English. Outcome variables were dichotomized to correct for high skew by (1) applying the cutoffs from the original authors of each measure when available, (2) using the upper quartile (75th percentile) to differentiate between high and low, or (3) using a single response to any item on the scale or the most extreme score for highly skewed variables.

Biological

Chlamydia infection was assessed with a sample of voided urine (first part of stream—not midstream) using strand displacement amplification [27]. Urine samples were collected at baseline, 6-months, and 12-months.

Behavioral

Condom use was assessed with one item from an interview used in previous research with Hispanic women [20]. Due to low baseline rates of consistent condom use, any reported use of (male) condoms was coded as 1; none was coded as 0.

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) was assessed with the Partner-to-you scale from the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale short form [28]. The scale consists of an assessment of the frequency of 12 behaviors (e.g., “insulted you”, “beat you up”, “forced you to have sex”) which are summed for a total score. A positive response to any of these behaviors was coded as 1; none was coded as 0. In this sample Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .84 to .87 at all assessments.

Got Drunk was assessed with an item (“In the past 3 months, how often have you been drunk on alcohol”) from a substance abuse instrument adapted from Kelly et al. [29]. This variable was coded 1 = got drunk in past 3 months vs. 0 = did not get drunk.

Social-Cognitive and Community Prevention

Partner communication was measured with the Communication with Partner scale [30]. This scale has 10 items (e.g., “Asked your partner(s) how he/she felt about using condoms before you had intercourse?”) about whether (yes or no) the respondent discussed topics related to HIV concerns with their primary sexual partner (αs > .86). A positive response to any of these behaviors was coded as 1; none was coded as 0.

Perceived HIV risk was assessed with a single item (“What are the chances of getting HIV/AIDS from what you have done during the past 3 months?”) used in previous research with Hispanic women [31]. Women could respond on a 4-point scale, 0 = very low to 3 = very high. The variable was dichotomized, 0 = very low, 1 = low to very high.

Self-efficacy for HIV/AIDS prevention was measured with a 7 item (e.g., “It would be easy to make my partner(s) use condoms”) self-assessment of the women’s confidence in their ability to accomplish HIV prevention behaviors [31]. Responses were summed for a total score (αs > .68). High scores were defined as responding with strongly agree to all questions.

HIV Related Knowledge was assessed with a 12 item scale containing questions about HIV transmission, prevention and consequences (e.g., “Condoms cause men physical pain”) [32]. Items answered correctly were summed to a total score (αs > .52). High scores were defined as ≥90% questions answered correctly.

Safer sex peer norms were assessed using 4-items (e.g., “Most of my closest friends use condoms when they have sex with a man”) adapted from Sikkema and colleagues for Hispanic women [20, 33]. Women responded on a 4-point Likert scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree). Items were summed, resulting in a range of 4–16 (αs > .80); high scores were defined as those in the upper quartile (≥75th percentile).

Perceived barriers to condom use was measured with 4 items (e.g., “Sex is not as good with a condom”) adapted from Sikkema and others for Hispanic women [20, 33]. Women responded on a 4-point Likert scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree). Items were summed, resulting in a possible range of 4–16 for the total score (αs > .52). High scores were defined as those in the upper quartile (≥75th percentile).

Behavioral intentions to use condoms was measured with 4 items (e.g., “I will say no to sex with a male partner if he will not use a condom”) adapted from Sikkema and colleagues for Hispanic women [20, 33]. Women responded on a 4-point Likert scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree) (αs > .73); high scores were defined as those in the upper quartile (≥75th percentile).

Community Prevention was defined as responding yes to either of two questions (“In the past 3 months, how many times have you talked about HIV/AIDS concerns with men/women and/or other people who live in your community?” and “In the past 3 months, how many times have you talked about HIV/AIDS with men/women and/or other people who live outside of your community?”) [20]. This variable was coded as 1 = talk about HIV/AIDS at least once vs. 0 = none.

Depression The CES-D [34] has 20 questions addressing the frequency (0 = rarely or none of the time, 3 = most of the time) of depressive symptoms experienced in the past week, with English or Spanish items [35]. Responses are added for a total (range 0–60; αs > .94). High scores were defined as those above the cutoff (16) for likely clinical depression [27].

Hispanicism and Americanism were measured with the Bidimensional Acculturation Scale [36], a 24-item measure of several domains including language use, linguistic proficiency, and electronic media in either Spanish or English. To score the subscales 12 items are averaged giving a range between 1 (low) and 4 (high). High internal consistency (α = .96) was reported in the original Hispanic sample [36]. In this study reliability was high (α = .85 and .95 for Hispanicism and Americanism, respectively). Acculturation was included only to describe the sample.

Analyses

Each hypothesis was tested in a separate intent-to-treat (ITT) generalized estimating equations (GEE) analysis in SPSS 17, which allowed the inclusion of all data over time, provided estimates robust to correlations from repeated measures using an AR-1 covariance structure [37], and allowed logistic distributions for outcomes. Goodness of fit between linear change (Time × Condition) and quadratic change (Time squared × Condition) over time was evaluated using the Corrected Quasi-likelihood under Independence Model Criterion. Mediation was tested using latent growth modeling in Mplus 5.21 [38]. Only variables that were significantly influenced by the intervention were tested as possible mediators for condom use, the primary behavioral outcome.

Results

Biological

As seen in Table 2, rates of Chlamydia were very low (0–1%). There was a significant Time × Condition interaction, B = 15.60, SE = 2.00, P < .001, 95% CI [11.69, 19.51], and a significant Time2 × Condition interaction, B = −3.89, SE = 0.49, P < .001, 95% CI [−4.84, −2.94], on Chlamydia infection. Control women showed an initial drop in infection followed by an increase to original levels, but Chlamydia rates in SEPA remained very low across the year.

Behavioral

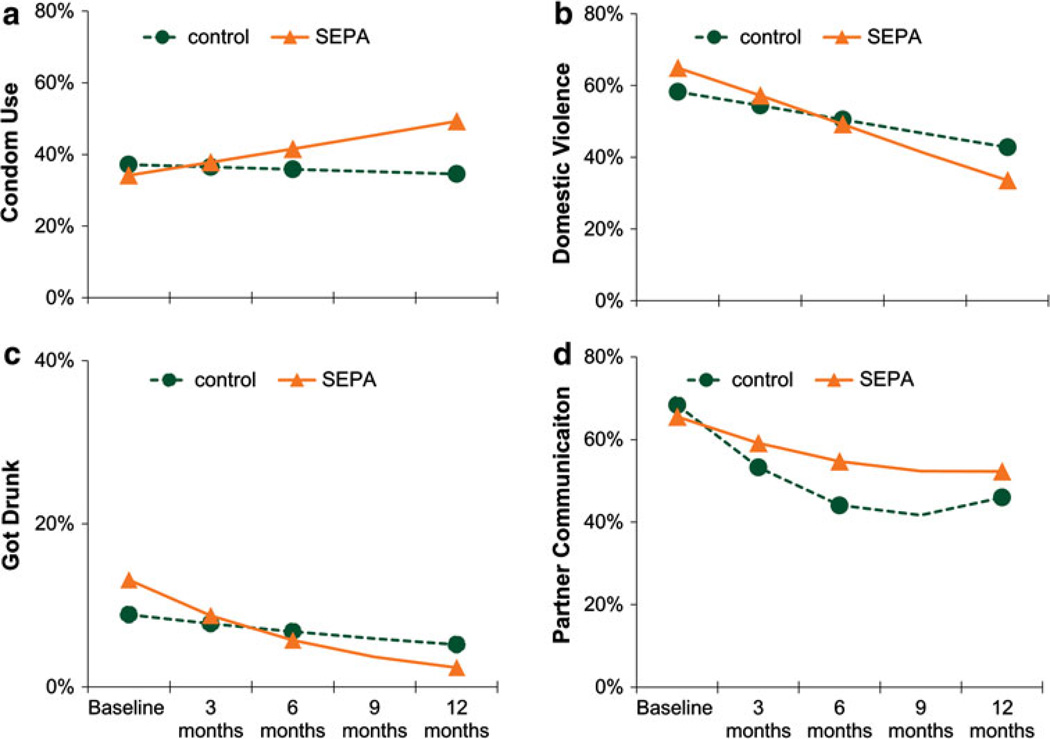

There was a significant Time × Condition interaction, B = 0.18, SE = 0.06, P < .001, 95% CI [0.08, 0.19], on using condoms, such that SEPA women were more likely to use condoms over time. There was a significant Time × Condition interaction, B = −0.17, SE = 0.06, P < .01, 95% CI [−0.29, −0.05], on IPV, such that SEPA women reported greater reductions in IPV over time. There was a significant Time × Condition interaction, B = −0.31, SE = 0.14, P < .05, 95% CI [−0.59, −0.04], on getting drunk. Specifically, SEPA women were less likely to get drunk over time. Figure 3 shows the trajectories of behavioral outcomes over the year for women in both conditions.

Fig. 3.

Estimated trajectories over 1 year of a condom use, b domestic violence, c got drunk, and d partner communication for women in the control (circles, dashed lines) and SEPA (triangles, solid lines) conditions. The y-axis for got drunk is on a different scale than the other outcomes due to the low number of women who got drunk in this sample

Social Cognitive and Community Prevention

There was a significant Time × Condition interaction, B = 0.46, SE = 0.20, P < .05, 95% CI [0.06, 0.86], and a trend toward a significant Time2 × Condition interaction, B = −0.09, SE = 0.05, P = .06, 95% CI [−0.18, 0.00], on partner communication. Specifically, SEPA women showed a lower decrease over time in the probability of engaging in partner communication. There was no difference in perceived HIV risk, B = −0.01, SE = 0.02, P = .51, 95% CI [−0.05, 0.03]. There was no difference in self-efficacy, Time × Condition interaction, B = 0.21, SE = 0.21, P = .30, 95% CI [−0.19, 0.62], Time2 × Condition interaction, B = −0.07, SE = 0.05, P = .15, 95% CI [−0.16, 0.02]. There was a significant Time × Condition interaction, B = 0.58, SE = 0.20, P < .01, 95% CI [0.20, 0.97], and a significant Time2 × Condition interaction, B = −0.14, SE = 0.05, P < .01, 95% CI [−0.23, −0.05], on HIV knowledge. Specifically, SEPA women showed a greater increase in HIV knowledge through 6-months, but had similar knowledge to controls by 12-months. There was no difference in norms over time, B = 0.05, SE = 0.06, P = .44, 95% CI [−0.07, 0.17]. There was a significant Time × Condition interaction, B = −2.27, SE = 0.96, P < .05, 95% CI [−4.15, −0.38], and a significant Time2 × Condition interaction, B = 0.58, SE = 0.24, P < .05, 95% CI [0.12, 1.05], on perceived barriers. Specifically, SEPA women had decreased perceived barriers through 6-months, but a similar probability as controls at 12-months. There was a significant Time × Condition interaction, B = 0.43, SE = 0.22, P < .05, 95% CI [0.01, 0.86], and a significant Time2 × Condition interaction, B = −0.11, SE = 0.05, P < .05, 95% CI [−0.22, −0.01], on behavioral intentions to use condoms. Specifically, SEPA women showed a greater increase in intentions through 6-months, with little difference by 12-months. There was a significant Time × Condition interaction, B = 0.92, SE = 0.20, P < .001, 95% CI [0.54, 1.30], and Time2 × Condition interaction, B = −0.21 SE = 0.05, P < .001, 95% CI [−0.30, −0.13], on community prevention, such that SEPA women were more likely to talk about HIV/AIDS through 6-months, but little difference by 12-months. There was no difference in depression over time, B = 0.00, SE = 0.06, P = .99, 95% CI [−0.12, 0.12].

Mediation

Change in partner communication was not related to change in condom use, B = −0.98, SE = 0.51, P = .05, 95% CI [−1.81, 0.15], indicating no mediation. Change in HIV knowledge was related to change in condom use, B = 1.55, SE = 0.27, P < .001, 95% CI [1.11, 1.99], and the indirect effect (intervention to change in HIV knowledge to change in condom use) was statistically significant, B = 0.40, SE = 0.10, P < .001, 95% CI [−2.55, 0.21], indicating mediation. Change in percieved barriers was not related to change in condom use, B = −1.17, SE = 0.84, P = .16, 95% CI [−2.55, 0.21]. Change in behavioral intentions to use condoms was related to change in condom use, B = 1.48, SE = 0.14, P < .001, 95% CI [1.26, 1.70], and the indirect effect (intervention to change in behavioral intentions to change in condom use) was statistically significant, B = 0.92, SE = 0.20, P < .001, 95% CI [0.19, 0.41], indicating mediation. Change in community prevention was related to change in condom use, B = 0.19, SE = 0.09, P < .05, 95% CI [0.54, 1.30], but the indirect effect (intervention to change in community prevention to change in condom use) was not statistically significant, B = 0.05, SE = 0.04, P = .16, 95% CI [−0.02, 0.14], which indicated no mediation.

Discussion

Results demonstrated that SEPA has moderate efficacy with many of the HIV risk factors under investigation. Specifically, the results confirmed hypotheses that SEPA would: (1) decrease biological risk (i.e., incidence of Chlamydia), (2) improve health safety behaviors (i.e., condom use, substance abuse and IPV), and (3) improve social cognitive and community prevention, although some changes were negligible as more time passed. The findings from this trial add to the evidence base supporting the efficacy of SEPA by corroborating the results documented in the first trial [20] and also by demonstrating efficacy for Hispanic women from diverse backgrounds. Notably SEPA reduced IPV, making it the first culturally-specific HIV prevention program known to reduce IPV. Most importantly, SEPA simultaneously addressed multiple and interrelated health disparities experienced by Latinas, which potentiates the public health significance of this intervention. Culturally specific interventions are needed for Hispanic women and promising findings of the current study indicate more research on the dissemination and the effectiveness of SEPA is warranted. Future wide-scale adaptations of SEPA should also account for cultural heterogeneity among Hispanic women.

There was mixed evidence for the theorized mechanisms of action of SEPA. Women in the SEPA intervention had improvements in relationship communication; however, this did not mediate intervention effects on condom use. Further research is needed to explore if alternate pathways connect improved communication to condom use (e.g., through decreased IPV). Women in the SEPA intervention had increases in HIV knowledge and behavioral intentions to use condoms which contributed to increases in condom use. The increased knowledge of HIV risk was likely related to increased intentions to use condoms, and thus encouraged SEPA participants to be more assertive about the initiating condom use with their sexual partners.

In contrast to the previous trial [20], women in SEPA did not show improvements in self-efficacy or perceived HIV risk. This may have been due to ceiling effects on the self-efficacy scale. Most women endorsed the extreme high responses at baseline, making it difficult to show improvements. Lack of change in perceived risk may have been related to the increased use of condoms and hence an actual decrease in risk. More research is needed to evaluate the validity and reliability of the self-efficacy measure for Hispanic women and to clarify the relationship between SEPA, self-efficacy and risk for HIV among Hispanic women.

Some initial gains in HIV risk variables for women in SEPA compared to the control condition appeared to decline over a full year. For example, HIV knowledge increased through the first 6 months of the follow-up period, but knowledge was at a level that was indistinguishable from the control condition at the 1 year follow-up. Similar diminishing effects of the SEPA intervention were also found for other variables, including perceived barriers and women’s likelihood of discussing HIV/AIDS. These declines support the development of longer-term HIV prevention interventions. Improvements for women in the delayed treatment control condition are consistent with the idea that repeated engagement with HIV risk topics (e.g., repeated questions about the importance of HIV prevention) has benefits. Perhaps by incorporating the peer-to-peer trainer model within SEPA, women can be trained to continue to educate other women in the community, raising the chances that the intervention will have longer-term positive effects.

There are several limitations to this study. Data on women’s behavior were self-reported and therefore subject to bias due to poor recall or impression management. Some measures had lower reliability for this sample of Hispanic women than expected based on past research with HIV risk interventions. Participants tended to respond strongly (either positively or negatively) to items on many measures, which led to the skewed response patterns and the need to dichotomize outcomes. Although use of dichotomous variables avoids violations of analysis assumptions, it does not allow for as rich of an analysis as continuous variables and may attenuate intervention effects. Future research should investigate response tendencies of Hispanic women with an eye to modifying existing measures or developing new measures that can assess a wider range of responses, and thus allow for analysis of continuous HIV risk variables. Assessors were not blinded to the participant assignment. Consequently, assessors may have interpreted and/or scored responses from participants differently based on knowledge of assignment. Assessor trainings addressed this potential source of bias and encouraged assessors to be cautious in committing this error.

Another important limitation of this study is that study participants appeared to be at relatively low risk for HIV as indicated by a lower than expected incidence of Chlamydia and a modal number of 1 sexual partner over the previous 3-months at baseline and during the study follow-up period. The majority of the sample consisted of immigrant Hispanic women with low levels of acculturation, most of whom were primarily Spanish-speaking (92%). Less acculturated women have been found to have poor HIV knowledge, unrealistic risk perceptions for HIV, and lower rates of condom use [5, 7]—all risks that were evident in this sample. Given that the primary the primary mode of HIV transmission for Hispanic women is sexual intercourse with a man [3], increasing the knowledge of HIV transmission, changing perceptions of risk and increasing condom use are important prevention measures for this population. Additionally, Spanish-speaking immigrant women have low levels of insurance coverage and encounter barriers in accessing health services [39]. These provide barriers in accessing HIV related information, screening and treatment, making community-based prevention programs an important means of reaching this population. Finally, research appears to indicate that as Hispanic women acculturate, they begin to demonstrate more risky behaviors such as having multiple sexual partners and substance abuse [7]. Consequently, interventions need to target this less acculturated, apparently “lower risk” population, in order to provide this group with the necessary knowledge, skills and services to protect themselves against HIV as they adjust to a new environment.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NCMHD) grant 1P60 MD002266—Center of Excellence for Health Disparities Research: El Centro, (Nilda P. Peragallo, Principal Investigator).

Footnotes

Human Participation Protection

This study was approved by the University of Miami and the Miami-Dade County Health Departments IRBs.

Contributor Information

Nilda Peragallo, Center of Excellence for Health Disparities Research: El Centro, School of Nursing and Health Studies, University of Miami, 5030 Brunson Drive, Coral Gables, FL 33124, USA.

Rosa M. Gonzalez-Guarda, Email: rosagonzalez@miami.edu, Center of Excellence for Health Disparities Research: El Centro, School of Nursing and Health Studies, University of Miami, 5030 Brunson Drive, Coral Gables, FL 33124, USA.

Brian E. McCabe, Center of Excellence for Health Disparities Research: El Centro, School of Nursing and Health Studies, University of Miami, 5030 Brunson Drive, Coral Gables, FL 33124, USA

Rosina Cianelli, Center of Excellence for Health Disparities Research: El Centro, School of Nursing and Health Studies, University of Miami, 5030 Brunson Drive, Coral Gables, FL 33124, USA; Escuela de Enfermeria, Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Santiago, Region Metropolitana, Chile.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Women and health: today’s evidence, tomorrow’s agenda. [Accessed 9 December 2010];2009 Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2009/WHO_IER_MHI_STM.09.1_eng.pdf.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimates of new HIV infection in the United States. [Accessed 9 December 2010];2008 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/factsheets/incidence.htm.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS among Hispanics/Latinos. [Accessed 29 September 2011];2010 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/hispanics/resources/factsheets/pdf/hispanic.pdf.

- 4.US Census Bureau. State & county quickfacts Miami-Dade County, Florida. [Accessed 9 December 2010]; Revised August 16, 2010; Available at: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/12/12086.html.

- 5.Shedlin MG, Decena CU, Oliver-Velez D. Initial acculturation and HIV risk among new Hispanic immigrants. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(7 Suppl):32S–37S. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cianelli R, Ferrer L, McElmurry BJ. HIV prevention and low-income Chilean women: machismo, marianismo and HIV misconceptions. Cult Health Sex. 2008;10(3):297–306. doi: 10.1080/13691050701861439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzalez-Guarda RM, Peragallo N, Urrutia MT, Vasquez EP. HIV risk, substance abuse and intimate partner violence among Hispanic females and their partners. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2008;19(4):252–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peragallo N. Latino women and AIDS risk. Public Health Nurs. 1996;13(3):217–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.1996.tb00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell JC, Baty ML, Ghandour RM, Stockman JK, Francisco L, Wagman J. The intersection of intimate partner violence against women and HIV/AIDS: a review. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2008;15(4):221–231. doi: 10.1080/17457300802423224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Women and HIV/AIDS in the United States: 2010. [Accessed 10 December 2010]; Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats08/surv2008-Complete.pdf.

- 11.Dworkin SL, Ehrhardt AA. Going beyond “ABC” to include “GEM”: critical reflections on progress in the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):13–18. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.074591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.UNESCO. A cultural approach to HIV/AIDS prevention and care: UNESCO/UNAIDS research project. [Accessed 9 December 2010];2002 Available at: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001262/126289e.pdf.

- 13.U.S. Census Bureau. Health status, health insurance and health services utilization: 2001. [Accessed 7 July 2011];2006 Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/2006pubs/p70-106.pdf.

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Subset of best-evidence interventions, by characteristics. [Accessed 1 July 2011];2009 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/research/prs/subset-best-evidence-interventions.htm.

- 15.El-Bassel N, Witte SS, Gilbert L, et al. The efficacy of a relationship-based HIV/STD prevention program for heterosexual couples. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(6):963–969. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raj A, Amaro H, Cranston K, Martin B, Cabral H, Navarro A, et al. Is a general women’s health promotion program as effective as an HIV-intensive prevention program in reducing HIV risk among Hispanic women? Public Health Rep. 2001;116(6):599–607. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.6.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amaro H, Raj A, Reed E, Cranston K. Implementation and long-term outcomes of two HIV intervention programs for Latinas. Health Promot Pract. 2002;3(2):245–254. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin M, Camargo M, Ramos L, Lauderdale D, Krueger K, Lantos J. The evaluation of a Latino community health worker HIV prevention program. Hispanic J Behav Sci. 2005;27(3):371–384. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harvey SM, Henderson JT, Thorburn S, Beckman LJ, Casillas A, Mendez L, et al. A randomized study of a pregnancy and disease prevention intervention for Hispanic couples. Perspect Sex and Reprod Health. 2004;36(4):162–169. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.162.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peragallo N, Deforge B, O’Campo P, Lee SM, Kim YJ, Cianelli R, Ferrer L. A randomized clinical trial of an HIV risk reduction intervention among low-income Latina women. Nurs Res. 2005;54(2):108–118. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200503000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi KH, Hoff C, Gregorich SE, Grinstead O, Gomez C, Hussey W. The efficacy of female condom skills training in HIV risk reduction among women: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(10):1841–1848. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.113050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzalez-Guarda RM, Vasquez EP, Urrutia MT, Villarruel A, Peragallo N. Hispanic females’ experiences with substance abuse, intimate partner violence and risk for HIV. J Transcult Nurs. 2011;22(1):46–54. doi: 10.1177/1043659610387079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim Y, Peragallo N, DeForge B. Predictors of participation in an HIV risk reduction intervention for socially deprived Latino women: a cross sectional cohort study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;43(5):527–534. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bandura A. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen J. Statistical analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freire P. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walker GT, Fraiser MS, Schram JL, Little MC, Nadeau JG, Malinowski DP. Strand displacement amplification—an isothermal, in vitro DNA amplification technique. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20(7):1691–1696. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.7.1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Straus MA, Douglas EM. A short form of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales, and typologies for severity and mutuality. Violence Vict. 2004;19(5):507–520. doi: 10.1891/vivi.19.5.507.63686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelly JA, Murphy DA, Washington CD, et al. The effects of HIV/AIDS intervention groups for high-risk women in urban clinics. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(12):1918–1922. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.12.1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Catania JA, Binson D, Dolcini MM, et al. Risk factors for HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases and prevention practices among US heterosexual adults: changes from 1990 to 1992. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(11):1492–1499. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.11.1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cianelli R. University of Illinois at Chicago, Health Sciences Center; 2003. HIV/AIDS issues among Chilean Women: cultural factors and perception of risk for HIV/AIDS acquisition [dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heckman TG, Kelly JA, Sikkema K, et al. HIV risk characteristics of young adult, adult, and older adult women who live in inner-city housing developments: implications for prevention. J Womens Health. 1995;4(4):397–406. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sikkema KJ, Heckman TG, Kelly JA, et al. HIV risk behaviors among women living in low-income, inner-city housing developments. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(8):1123–1128. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.8_pt_1.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts RE, Vernon SW, Rhoades HM. Effects of language and ethnic status on reliability and validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale with psychiatric patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1989;177(10):581–592. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198910000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marin G, Gamba RJ. A new measurement of acculturation for Hispanics: the Bidimensional Acculturation Scale for Hispanic. Hispanic J Behav Sci. 1996;18(3):297–316. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diggle PJ, Liang K, Zeger SL. Analysis of longitudinal data. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 5th ed. Los Angeles: Muthén and Muthén; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pew Hispanic Center and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Hispanics and health care in the United States: Access, information and knowledge. [Accessed 30 September 2011];2004 Available at: http://www.pewhispanic.org/files/reports/91.pdf.