Abstract

Among terrestrial organisms, arthropods are especially susceptible to dehydration, given their small body size and high surface area to volume ratio. This challenge is particularly acute for polar arthropods that face near-constant desiccating conditions, as water is frozen and thus unavailable for much of the year. The molecular mechanisms that govern extreme dehydration tolerance in insects remain largely undefined. In this study, we used RNA sequencing to quantify transcriptional mechanisms of extreme dehydration tolerance in the Antarctic midge, Belgica antarctica, the world’s southernmost insect and only insect endemic to Antarctica. Larvae of B. antarctica are remarkably tolerant of dehydration, surviving losses up to 70% of their body water. Gene expression changes in response to dehydration indicated up-regulation of cellular recycling pathways including the ubiquitin-mediated proteasome and autophagy, with concurrent down-regulation of genes involved in general metabolism and ATP production. Metabolomics results revealed shifts in metabolite pools that correlated closely with changes in gene expression, indicating that coordinated changes in gene expression and metabolism are a critical component of the dehydration response. Finally, using comparative genomics, we compared our gene expression results with a transcriptomic dataset for the Arctic collembolan, Megaphorura arctica. Although B. antarctica and M. arctica are adapted to similar environments, our analysis indicated very little overlap in expression profiles between these two arthropods. Whereas several orthologous genes showed similar expression patterns, transcriptional changes were largely species specific, indicating these polar arthropods have developed distinct transcriptional mechanisms to cope with similar desiccating conditions.

Keywords: physiological ecology, environmental stress

For organisms living in arid environments, mechanisms to maintain water balance and cope with dehydration stress are an essential physiological adaptation. Insects, in particular, are at high risk of dehydration because of their small body size and consequent high surface area to volume ratio (1). Physiological mechanisms for maintaining water balance in insects include adaptations to reduce cuticular water permeability (2) and mechanisms to reduce respiratory water loss (3). When water balance cannot be maintained, insects evoke a suite of molecular mechanisms to cope with cellular osmotic stress. For example, during periods of dehydration, heat shock proteins are up-regulated to minimize protein damage (4), whereas aquaporins mediate water movement between cellular compartments (5). However, we have a limited knowledge of the large-scale molecular changes prompted by water loss.

Among terrestrial biomes, polar environments are particularly challenging from a water balance perspective, as water is frozen and therefore unavailable for much of the year (6). Polar arthropods are typically extremely tolerant of desiccation, with some being able to survive near-anhydrobiotic conditions (7). One such dehydration-tolerant polar arthropod is the Antarctic midge, Belgica antarctica, Antarctica’s only endemic insect and the southernmost free-living insect. Larvae of B. antarctica are one of the most dehydration-tolerant insects known, surviving a 70% loss of water under ecologically relevant conditions (8). In this species, the ability to tolerate dehydration is an important adaptation for successful overwintering. The loss of water enhances acute freezing tolerance (8). In addition, overwintering midge larvae are capable of undergoing another distinct form of dehydration, known as cryoprotective dehydration (9). During cryoprotective dehydration, a gradual decrease in temperature in the presence of environmental ice creates a vapor pressure gradient that draws water out of the body, thereby depressing the body fluid melting point and allowing larvae to remain unfrozen at subzero temperatures (10).

In this study, we used next-generation RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) to quantify genome-wide mRNA changes in response to both dehydration at a constant temperature and cryoprotective dehydration. Although our recent work on B. antarctica has revealed several key molecular mechanisms of dehydration tolerance, including expression of heat shock proteins (11), aquaporins (12, 13), and metabolic genes (14), we lack a comprehensive understanding of the genes and pathways involved in extreme dehydration tolerance. To date, only three studies have examined large-scale transcriptional changes in response to dehydration in insects, all of which were conducted on tropical species. Cornette et al. (15) identified genes associated with anhydrobiosis in the African sleeping midge, Polypedilum vanderplanki, using a semiquantitative EST approach, whereas Wang et al. (16) and Matzkin et al. (17) used microarrays to examine genome-wide transcriptional changes following dehydration in Anopheles gambiae and Drosophila mojavensis, respectively. In addition to the insect studies, transcriptional responses to desiccation have been reported for an Arctic arthropod closely related to insects, the springtail (Collembola) Megaphorura arctica (18), as well as a widely distributed collembolan, Folsomia candida (19). Here, in response to dehydration, we report up-regulation of recycling pathways such as the proteasome and autophagy with a concurrent shutdown of central metabolism. Complementary metabolomics experiments supported a number of our transcriptome observations, indicating a strong correlation between gene expression and metabolic end products during dehydration. Using comparative genomics, we also compared the molecular response to dehydration in the Antarctic species B. antarctica with that of the Arctic arthropod M. arctica (18).

Results and Discussion

The Antarctic midge, B. antarctica, is one of the most dehydration-tolerant insects that has been characterized. In this study, we used RNA-seq to measure gene expression levels in response to the following treatments that hereafter we refer to as control, desiccation, and cryoprotective dehydration: control, held at 4 °C and 100% relative humidity, fully hydrated; desiccation, constant temperature of 4 °C and 93% relative humidity for 5 d, resulting in ∼40% water loss; cryoprotective dehydration, gradually chilled over 5 d from −0.6 to −3 °C at vapor pressure equilibrium with surrounding ice and then held at −3 °C for 10 d (9) (also yielded ∼40% water loss).

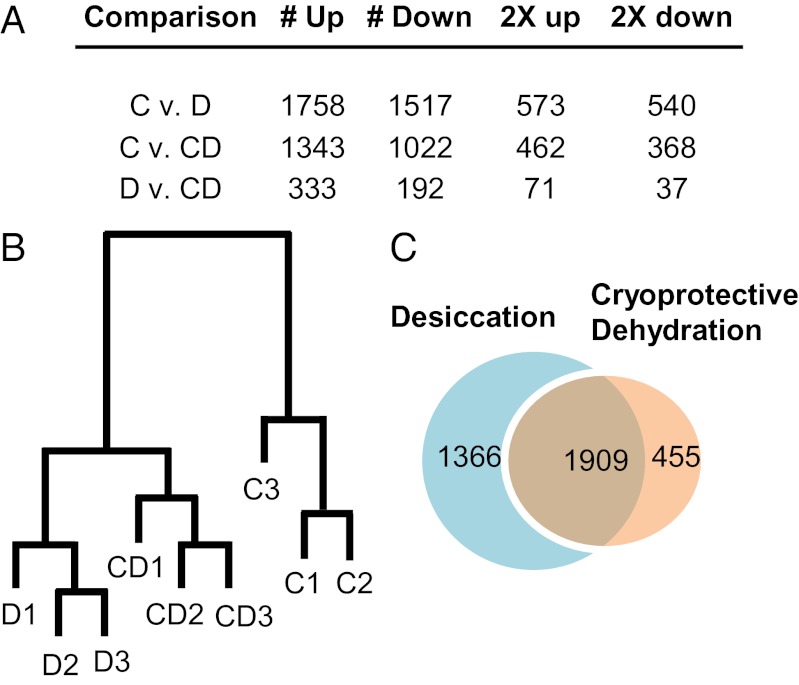

Both dehydration treatments resulted in substantial changes in gene expression. Of the ∼11,500 gene models that had enough reads to support estimation of differential expression, 3,275 and 2,365 were differentially expressed during desiccation and cryoprotective dehydration, respectively (Fig. 1A; Datasets S1 and S2). Hierarchical clustering analysis indicated that the desiccation and cryoprotective dehydration treatments yielded distinct transcriptional signatures (Fig. 1B). However, a majority of the differentially expressed genes were shared between the two treatments (Fig. 1C), and downstream analyses revealed that many enriched pathways were identical. Thus, for clarity, we will primarily discuss the results of the desiccation treatment, whereas specific results from the cryoprotective dehydration treatment can be found in the Tables S1 and S2. Additionally, a direct comparison of the desiccation and cryoprotective dehydration treatments, highlighting the expression differences between these two conditions, is provided in Dataset S3 and Table S3. However, it is worth mentioning that time differences between the two dehydration treatments (5 d for desiccation and 15 d for cryoprotective dehydration) may also contribute to differences between these treatments. To validate our expression results, we used qPCR to measure expression of 13 genes in the same RNA samples used for RNA-seq. Overall, there was excellent agreement between the RNA-seq results and qPCR results (Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Expression summary (A), dendrogram (B), and Venn diagram (C) showing degree of similarity between the D and CD groups. In A and B, the criteria for differentially expressed genes was false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05. In C, the length of each branch indicates the relative distance between two nodes. C, control; D, desiccation; CD, cryoprotective dehydration.

Functional Categories of Differentially Expressed Genes.

To place these large-scale changes in gene expression into a meaningful context, we identified enriched functional categories using gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis (Table 1) and enriched Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) pathways using gene set analysis (GSA; Table 2). To distinguish between functional categories of genes that are turned on and off in response to desiccation, we separated the GO enrichment analysis into lists of up- and down-regulated genes.

Table 1.

GO enrichment analysis of genes up-regulated or down-regulated in response to desiccation

| GO term | Definition | FDR | No. up- or down-regulated | Total in category |

| Up | ||||

| GO:0006511 | Ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic process | 7.35E−03 | 29 | 82 |

| GO:0007465 | R7 cell fate commitment | 1.20E−02 | 10 | 14 |

| GO:0009408 | Response to heat | 1.20E−02 | 21 | 50 |

| GO:0007015 | Actin filament organization | 1.96E−02 | 28 | 80 |

| GO:0006468 | Protein phosphorylation | 1.96E−02 | 86 | 363 |

| GO:0007264 | Small GTPase mediated signal transduction | 2.75E−02 | 26 | 98 |

| GO:0042176 | Regulation of protein catabolic process | 8.51E−02 | 6 | 8 |

| Down | ||||

| GO:0006508 | Proteolysis | 9.33E−20 | 152 | 595 |

| GO:0008152 | Metabolic process | 1.52E−17 | 193 | 827 |

| GO:0055114 | Oxidation-reduction process | 1.62E−12 | 160 | 732 |

| GO:0006030 | Chitin metabolic process | 4.22E−12 | 44 | 104 |

| GO:0015992 | Proton transport | 2.55E−08 | 19 | 30 |

| GO:0015986 | ATP synthesis coupled proton transport | 8.39E−07 | 14 | 19 |

| GO:0005975 | Carbohydrate metabolic process | 1.48E−05 | 48 | 177 |

| GO:0006754 | ATP biosynthetic process | 3.68E−05 | 17 | 32 |

| GO:0006629 | Lipid metabolic process | 8.70E−05 | 41 | 159 |

| GO:0006810 | Transport | 1.36E−04 | 133 | 756 |

| GO:0006096 | Glycolysis | 2.38E−04 | 15 | 30 |

| GO:0055085 | Transmembrane transport | 1.22E−03 | 82 | 408 |

| GO:0006099 | Tricarboxylic acid cycle | 2.16E−03 | 15 | 36 |

| GO:0006123 | Mitochondrial electron transport, cytochrome c to O2 | 3.08E−03 | 6 | 7 |

| GO:0003333 | Amino acid transmembrane transport | 1.12E−02 | 11 | 28 |

| GO:0006812 | Cation transport | 1.72E−02 | 15 | 40 |

| GO:0044262 | Cellular carbohydrate metabolic process | 3.11E−02 | 5 | 6 |

| GO:0008643 | Carbohydrate transport | 3.34E−02 | 18 | 61 |

| GO:0015672 | Monovalent inorganic cation transport | 3.34E−02 | 4 | 4 |

| GO:0015991 | ATP hydrolysis coupled proton transport | 3.34E−02 | 11 | 28 |

| GO:0006032 | Chitin catabolic process | 5.91E−02 | 9 | 22 |

| GO:0019083 | Viral transcription | 8.20E−02 | 6 | 11 |

| GO:0006865 | Amino acid transport | 9.50E−02 | 7 | 15 |

| GO:0009253 | Peptidoglycan catabolic process | 9.98E−02 | 6 | 13 |

GO, gene ontology; FDR, false discovery rate.

Table 2.

GSA revealing enriched KEGG pathways during desiccation

| Gene set name | Score | Adjusted P value |

| Positive gene sets* | ||

| Regulation of autophagy | 1.27 | <2E−4 |

| TGF-β signaling pathway | 1.11 | <2E−4 |

| mTOR signaling pathway | 0.82 | <2E−4 |

| Endocytosis | 0.68 | <2E−4 |

| Ether lipid metabolism | 0.41 | <2E−4 |

| Negative gene sets* | ||

| Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate acid metabolism | −2.07 | <2E−4 |

| Glycolysis/gluconeogenesis | −1.32 | <2E−4 |

| Starch and sucrose metabolism | −1.19 | <2E−4 |

| Galactose metabolism | −1.05 | <2E−4 |

| Nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism | −1.03 | <2E−4 |

| Propanoate metabolism | −1.01 | <2E−4 |

| Pyruvate metabolism | −0.85 | <2E−4 |

| Tryptophan metabolism | −0.78 | <2E−4 |

| β-Alanine metabolism | −0.71 | <2E−4 |

| Valine, leucine, and isoleucine degradation | −0.60 | <2E−4 |

| Arginine and proline metabolism | −0.58 | <2E−4 |

| Metabolism of xenobiotics | −0.58 | <2E−4 |

| Glutathione metabolism | −0.54 | <2E−4 |

| Fatty acid metabolism | −0.54 | <2E−4 |

| Folate biosynthesis | −0.45 | <2E−4 |

| Phagosome | −0.35 | <2E−4 |

*Positive gene sets are enriched gene sets in which genes tend to be up-regulated, whereas negative gene sets are enriched gene sets in which genes tend to be down-regulated.

Functional Categories Up-Regulated During Desiccation.

In response to desiccation, we observed enrichment of several functional terms, notably terms related to stress response, ubiquitin-dependent proteasome, actin organization, and signal transduction, specifically several GTPase enzymes that are involved in membrane trafficking (Table 2). The GO term “response to heat” was enriched in the up-regulated genes, and this category primarily encompasses the heat shock proteins (hsps), cellular chaperones that repair misfolded proteins in response to various environmental stressors (20), including heat, cold (21), oxidative damage (22), and dehydration (4, 11). Our group has demonstrated the importance of hsps in B. antarctica stress tolerance (11, 23), but previous studies were limited to a few hsp genes obtained by targeted approaches. Here, we report up-regulation of numerous putative hsps, including members of the small heat shock protein (three members), hsp40 (two members), hsp70 (eight members), and hsp90 (one member) families (Dataset S1). We also observed ∼1.8-fold up-regulation of hsf, the transcription factor that regulates hsp expression (24). In addition to chaperone activity, hsps target damaged proteins to the proteasome to prevent accumulation of dysfunctional proteins and to recycle peptides and amino acids (25). Indeed, we detected enrichment of GO terms related to ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis (Table 1) in the desiccation up-regulated genes. Our results indicate coordinated up-regulation of hsps and proteasomal genes, which cooperatively function to repair and degrade damaged proteins during dehydration.

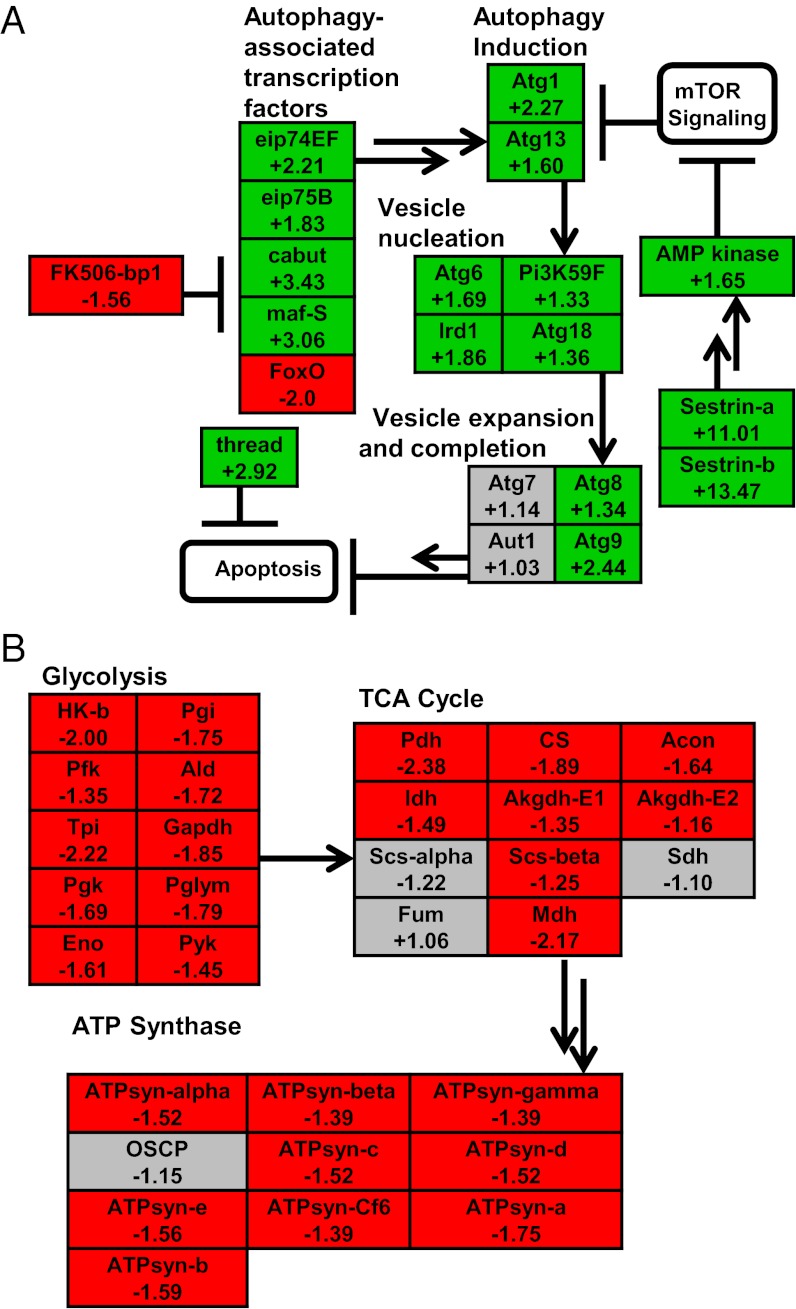

In our GSA, we observed positive enrichment of the KEGG pathway “Regulation of autophagy” during desiccation (Table 2). Autophagy is a catabolic process in which parts of the cytoplasm and organelles are sequestered into vesicles and digested in lysosomes (26), thereby conserving cellular macromolecules and energy during periods of stress and nutrient deprivation. Although autophagy can be an alternative means of programmed cell death, during times of stress, autophagy can reduce the amount of cell death by recycling cellular components and inhibiting apoptotic cell death (26). We hypothesize that during dehydration, the level of autophagy increases, which conserves energy and promotes survival during prolonged periods of cellular stress.

We identified 92 homologs of genes with known function in autophagy and programmed cell death that were differentially expressed during desiccation and/or cryoprotective dehydration (Dataset S4). Several lines of evidence support the hypothesis that dehydration promotes autophagy while concurrently inhibiting apoptosis (Fig. 2A). This evidence includes the following. (i) An 11-fold up-regulation of sestrin during desiccation. Sestrins are highly conserved genes that have an antioxidant function and promote longevity by inhibiting apoptosis and increasing autophagy via inhibition of TOR signaling (27). (ii) Significant up-regulation of six authophagy-related signaling genes (atg1, atg6, atg8, atg9, atg13, and atg18) that carry out the essential cellular functions of auophagy (28). (iii) Up-regulation of four transcription factors, eip74EF, eip75EF, cabut, and maf-S, that are positive regulators of autophagy in D. melanogaster (29). (iv) A threefold up-regulation of thread, a potent inhibitor of apoptotic cell death that prevents activity of proapoptotic caspases (30). (v) Up-regulation of proteasomal genes, suggesting cross-talk and cooperation between these distinct cellular recycling pathways (31). We suspect that the autophagy pathway serves an important protective function by limiting cell death and turnover of macromolecules during dehydration, especially during the long Antarctic winter.

Fig. 2.

Pathway diagrams illustrating up-regulation of autophagy-related genes (A) and down-regulation of carbohydrate metabolism and ATP synthesis (B). Green boxes indicate significant up-regulation, red boxes indicate significant down-regulation, and gray boxes indicate no significant change in expression. Gene abbreviations are provided in SI Methods. Only the results for the closest homolog to each D. melanogaster gene (determined by BLAST) are included. Consecutive arrows indicate steps where intermediate reactions are not pictured or the intermediate reactions are unknown.

Functional Categories Down-Regulated During Dehydration.

Up-regulation of cellular recycling pathways, such as ubiquitin-mediated proteasome and autophagy, likely serves to conserve energy during prolonged dehydration. Consistent with this idea, we observed down-regulation of genes related to general metabolism and ATP production (Table 1; Fig. 2B). Larvae of B. antarctica significantly depress oxygen consumption rates in response to dehydration (32). Metabolic depression is a common adaptation in dehydration-tolerant insects, presumably to minimize respiratory water loss and to minimize the loss of water bound to glycogen and other carbohydrates (33). This dehydration-mediated metabolic shutdown is strongly supported by gene expression data, as nearly 25% of all metabolic genes in our dataset were down-regulated in response to desiccation (Table 1). We noted a general shutdown of carbohydrate catabolism and ATP generation; nearly every gene involved in glycolysis, the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, and ATP synthesis is down-regulated (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, among our down-regulated genes, we observed enrichment of genes related to protein, lipid, and chitin metabolism, as well as energetically expensive processes such as membrane transport, including proton, cation, carbohydrate, and amino acid transport. A decrease in metabolic activity was further supported by our GSA results; nearly every negatively enriched KEGG pathway (i.e., pathways in which genes tended to be down-regulated) was related to metabolism, including several pathways related to carbohydrate and amino acid metabolism (Table 2). Thus, taken together, both GO enrichment analysis and GSA analysis of KEGG pathways revealed a coordinated shutdown of metabolic activity at the transcript level. We hypothesize that these mechanisms may be particularly important for overwintering larvae, contributing to energy conservation during the long Antarctic winter.

Dehydration-Induced Changes in the Metabolome.

To determine whether the above changes in metabolic gene expression correlated with changes in metabolic endpoints, we conducted a follow-up metabolomics experiment with the same treatment conditions. Using targeted GC-MS metabolomics, we measured levels of 36 compounds in response to desiccation and cryoprotective dehydration. As with gene expression, desiccation and cryoprotective dehydration had a major impact on the metabolome, as the concentrations of 32 of the 36 compounds significantly changed in at least one treatment (Fig. S2). Although the metabolic changes induced by desiccation and cryoprotective dehydration were largely similar, our treatment groups were distinct from one another, as determined by hierarchical clustering (Fig. S3).

We observed several distinct metabolic responses to desiccation, and these were generally supported by gene expression data. We noted the following. (i) Decreased levels of the glycolytic intermediates glucose-6-phosphate and fructose-6-phosphate, which reflected down-regulation of glycolysis genes (Fig. 2B). Hexokinase and glucose-6-phosphate isomerase, the enzymes that synthesize glucose-6-phosphate and fructose-6-phosphate, were both significantly down-regulated (>1.5-fold). Additionally, we observed decreased levels of lactate, the endpoint of anaerobic respiration through glycolysis. (ii) Accumulation of citrate, which is evidence of decreased flux through the TCA cycle, was supported by down-regulation of a number of TCA cycle genes (Fig. 2B). An alternative explanation for accumulation of citrate would be increased oxidation of fatty acids, but this hypothesis is not supported by the gene expression data, as a majority of fatty acid metabolism genes were down-regulated (Tables 1 and 2). (iii) Increase in proline levels from 7.8 to 21.1 nmol/mg dry mass in response to desiccation, which was supported by 1.5-fold up-regulation of pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase, the terminal enzyme of proline synthesis. Additionally, we observed 1.3-fold up-regulation of glutamate synthase and concurrent accumulation of glutamate, a precursor of proline, from 12.6 to 29.9 nmol/mg dry mass (Fig. S2). Although proline is a potent cryoprotectant in insects (34) and confers desiccation tolerance in plants (35), proline has not been linked to dehydration in insects. (iv) Accumulation of several osmoprotective polyols, of which the quantities of sorbitol (increase from 0.5 to 4.3 nmol/mg dry mass) and mannitol (increase from 5.0 to 155.1 nmol/mg dry mass) exhibited the most dramatic changes. Additionally, fructose, a precursor for both mannitol and sorbitol, increased from 1.3 to 33.4 nmol/mg dry mass. Although the genes involved in mannitol and sorbitol synthesis are poorly defined in insects, we did observe 4.6-fold up-regulation of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, the rate-limiting step of gluconeogenesis (36). Up-regulation of this gene leads to increased glucose production via gluconeogenesis, with glucose serving as a central precursor for the synthesis of most sugar alcohols. Interestingly, we did not observe accumulation of glucose during dehydration (Fig. S2), suggesting glucose is being shunted to other pathways as soon as it is produced. On the whole, there was good agreement between gene expression and metabolomics data. However, some metabolite changes could not be correlated with changes at the transcript level, suggesting posttranscriptional levels of control. Also, in some instances, changes in gene expression may alter rates of metabolic flux that are not captured in these types of metabolomics analyses.

Comparative Genomics of Molecular Response to Dehydration.

The transcriptomic response to dehydration has been studied in three other insects, the African sleeping midge P. vanderplanki (15), the mosquito A. gambiae (16), and the cactophilic fruit fly, D. mojavensis (17), as well as two closely related arthropods, the Arctic collembolan M. arctica (18) and the collembolan F. candida (19), thus facilitating cross-species comparisons of dehydration-induced gene expression. We observed several general similarities between our dataset and the transcriptome of P. vanderplanki, which inhabits temporary pools in tropical Africa. Like B. antarctica, dehydration in P. vanderplanki induced expression of a number of heat shock proteins, including multiple members of the hsp70 family. Additionally, dehydration in P. vanderplanki causes up-regulation of genes involved in cell death signaling and ubiquitin-mediated proteasome, patterns that are also quite prevalent in our dataset. However, one conspicuous difference between our dataset and that of P. vanderplanki is the absence of late embryogenesis active (LEA) proteins in the B. antarctica genome, despite B. antarctica and P. vanderplanki being in the same family, Chironomidae. LEA proteins are dehydration-associated proteins found in organisms ranging from bacteria to animals (37), but P. vanderplanki is the only true insect in which LEA genes have been identified.

Like B. antarctica, D. mojavensis is adapted to desiccating environments and, albeit warm, desert habitats. As in our dataset, severe dehydration in D. mojavensis elicited significant modulation of numerous metabolic pathways, including down-regulation of genes regulating flux through glycolysis and the TCA cycle (17). Thus, it appears down-regulation of metabolism may be a general feature of xeric-adapted insects. In contrast, comparing our expression data with A. gambiae revealed little overlap between our dataset and the mosquito response to desiccation. Nonetheless, similar to our results, Wang et al. (16) observed down-regulation of numerous metabolic genes, particularly genes related to chitin metabolism.

The transcriptomic study of dehydration in M. arctica (18) included two treatments very similar to our desiccation and cryoprotective dehydration treatments, allowing a formal comparison of the two datasets. M. arctica (formerly Onychiurus arcticus) is found on numerous islands in the northern Palearctic (38), and like B. antarctica is extremely dehydration-tolerant and capable of using cryoprotective dehydration as an overwintering strategy (7). Thus, we investigated whether B. antarctica and M. arctica share common transcriptional responses to desiccation and cryoprotective dehydration, despite their geographic and phylogenetic separation.

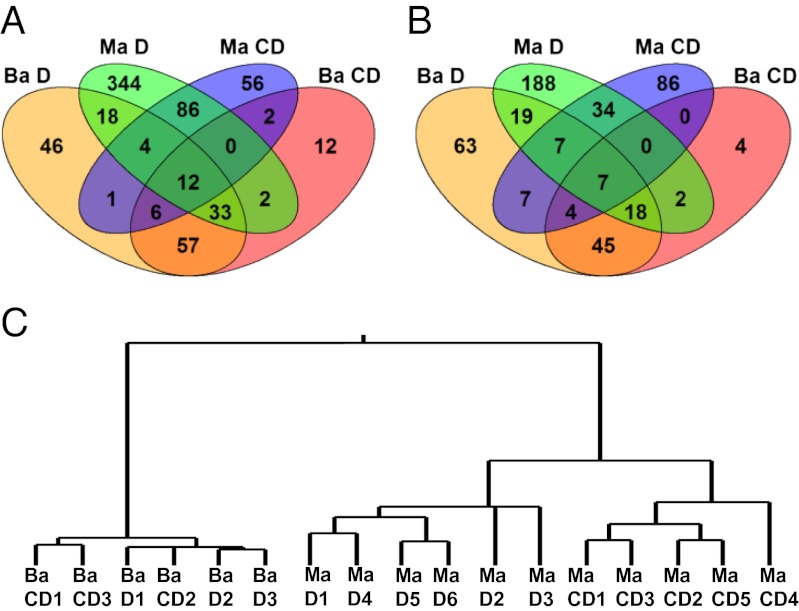

Using reciprocal blast, we identified 1,280 putative one-to-one orthologs between the B. antarctica gene models and the M. arctica EST library. Of these, we found 12 genes that were up-regulated in response to both desiccation and cryoprotective dehydration in both species, and 7 that were down-regulated (Dataset S5). Of note, common up-regulated genes included an hsp40 gene, two genes involved in the ubiquitin-mediated proteasome, and a GTPase involved in membrane trafficking, thus supporting the central roles of these processes during dehydration. Among the seven down-regulated genes in common were four genes involved in carbohydrate hydrolysis and a single peptidase, indicating that down-regulation of metabolic genes may be a common attribute of dehydration. Additionally, there were 37 genes that were either up- or down-regulated in response to desiccation only (Dataset S6), and 2 genes up-regulated only during cryoprotective dehydration. Genes specific to cryoprotective dehydration were a gene involved in unfolded protein binding and an acid-amino acid ligase.

Despite the above similarities in dehydration-induced gene expression, the expression profiles of B. antarctica and M. arctica during dehydration were largely different. The Venn diagrams in Fig. 3 A and B indicate that more differentially expressed genes are specific to a particular species than are shared between the two species. Also, hierarchical clustering indicates a high degree of separation in the transcript signatures of B. antarctica and M. arctica (Fig. 3C). Thus, the transcript signature for a particular group is more dependent on the species than the dehydration treatment it experienced. This result suggests that despite being adapted to similar habitats, B. antarctica and M. arctica have evolved distinct molecular responses to dehydration. General comparisons with a second collembolan transcriptomic dataset, that of F. candida (19), also revealed very little similarity to B. antarctica. In F. candida, desiccation at a constant temperature likewise results in down-regulation of lipid and chitin metabolism genes, but aside from these examples, very few genes showed similar expression patterns. These differences in expression patterns may reflect different strategies for combating dehydration; whereas B. antarctica shuts down metabolic activity and waits for favorable conditions to return, F. candida relies on active water vapor absorption to restore water balance during prolonged periods of desiccation. However, because B. antarctica and collembolans are so phylogenetically distant, similar comparisons with closely related chironomids are needed to better understand the evolutionary physiology of dehydration tolerance in this taxonomic family that is so well known for its extreme tolerance of multiple environmental stresses.

Fig. 3.

Venn diagrams (A and B) and dendrogram (C) showing degree of similarity between the gene expression profiles of the Antarctic midge B. antarctica (Ba) and the Arctic springtail M. arctica (Ma) in response to desiccation (D) and cryoproective dehydration (CD). The numbers of shared and unique up-regulated genes are depicted in A, whereas the numbers of shared and unique down-regulated genes are depicted in B. In C, hierarchical clustering was conducted on the log fold change values for each orthologous gene in each sample.

Methods

Larvae of B. antarctica were collected on offshore islands near Palmer Station (64°46′S, 64°04′W) in January 2010 and shipped to The Ohio State University. Before an experiment, fourth-instar larvae were handpicked from substrate in ice water and left at 4 °C overnight on moist filter paper to standardize body water content.

For these experiments, larvae were exposed to the following conditions: control (C, held at 100% relative humidity at 4 °C), desiccation (D, exposed to 93% relative humidity for 5 d at 4 °C), and cryoprotective dehydration (CD, temperature gradually lowered from −0.6 to −3 °C over 5 d in the presence of environmental ice and then held at −3 °C for 10 d). During cryoprotective dehydration, larvae lose water through the cuticle to the surrounding ice and remain unfrozen by decreasing the hemolymph melting point to match the temperature of the surrounding ice (9). Both the desiccation and cryoprotective dehydration treatments resulted in ∼40% water loss, with survival near 100%. Immediately after treatment, larvae were frozen at −70 °C, where they were held until RNA and metabolite extractions. Each treatment consisted of three biological replicates, with each replicate containing 20 larvae.

Total RNA was extracted from larvae using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies), and RNA-seq libraries were prepared with the Illumina TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation kit (Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Libraries were checked for the correct insert size on an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 and sequenced on an Illumina Genome Analyzer II. A summary of the raw sequencing data is provided in Table S4.

Reads were mapped to B. antarctica genomic contigs using Bowtie and TopHat (39), and we counted the total number of sequencing reads that aligned to each putative gene model in the draft B. antarctica genome using HTSeq. Genes were annotated using blastx (E-value cutoff of 1E−4) to compare our gene models with annotated protein sequences from Aedes aegypti and Drosophila melanogaster, and GO terms were assigned to each gene model with Blast2GO (40).

Differentially expressed genes were determined using the R package DESEq. (41). For hierarchical clustering of the phenotypic classes, we obtained variance stabilized data from DESeq, calculated a matrix of distances, and used the R package hclust for clustering. Enriched GO terms were determined using the R package GOsEq. (42), with P values corrected using the Benjamini and Hochberg method (43). We restricted the output to GO terms with ontology “Biological Process” to limit redundancy. Additionally, we tested for enriched KEGG pathways with the R package GSA (44). For GSA, we mapped our gene models to the A. aegypti proteome and tested the entire set of A. aegypti KEGG pathways for enrichment. Expression results were validated by conducting qPCR on a subset of genes (Table S5).

For comparative analysis with M. arctica, we identified putative orthologs between B. antarctica and M. arctica using reciprocal blast. We restricted gene expression comparisons to the two treatments in ref. 18 that were analogous to our desiccation and cryoprotective dehydration treatments, the treatments named “0.9 salt” and “−2°C,” respectively. The M. arctica microarray data were obtained from ArrayExpress (accession no. E-MEXP-2105) and analyzed using the R package limma according to the parameters outlined in ref. 18. To determine overall similarity in gene expression between groups, we conducted hierarchical clustering on the samples, restricting the analysis to orthologous transcripts.

Because a large number of metabolic genes were differentially regulated in our treatments, we also conducted a metabolomics analysis of the same treatment conditions. Metabolomics experiments were conducted as in ref. 21.

Additional methodological detail is provided in SI Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of Palmer Station for support during our field season. We also acknowledge Asela Wijeratne and members of the Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center Molecular and Cellular Imaging Center for running the sequencing reactions. We appreciate input from Xiaodong Bai during the initial planning phase of this study, and we thank Martin Holmstrup (Aarhus University) and Melody Clark (British Antarctic Survey) for critically reading the paper. We acknowledge Vanessa Larvor for technical assistance in the GC-MS experiments. This work was supported by National Science Foundation OPP-ANT-0837613 and ANT-0837559. Funding for the metabolomics experiments was provided by the French Polar Institute (Institut Polaire Français Paul-Emile Victor 136) and is linked with the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research Evolution and Biodiversity in the Antarctic research program.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: Raw sequencing reads are available in the NCBI Short Read Archive (accession no. SRA058518). The genomic contigs are available under NCBI BioProject PRJNA172148. Accession numbers for predicted transcripts in this study are deposited in the NCBI Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly database (accession no. GAAK01000000).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1218661109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Gibbs AG, Chippindale AK, Rose MR. Physiological mechanisms of evolved desiccation resistance in Drosophila melanogaster. J Exp Biol. 1997;200(12):1821–1832. doi: 10.1242/jeb.200.12.1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gibbs AG. Water-proofing properties of cuticular lipids. Am Zool. 1998;38(3):471–482. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chown SL. Respiratory water loss in insects. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2002;133(3):791–804. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(02)00200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benoit JB, Lopez-Martinez G, Phillips ZP, Patrick KR, Denlinger DL. Heat shock proteins contribute to mosquito dehydration tolerance. J Insect Physiol. 2010;56(2):151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu K, Tsujimoto H, Cha SJ, Agre P, Rasgon JL. Aquaporin water channel AgAQP1 in the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles gambiae during blood feeding and humidity adaptation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(15):6062–6066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102629108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kennedy AD. Water as a limiting factor in the Antarctic terrestrial environment: A biogeographical synthesis. Arct Alp Res. 1993;25(4):308–315. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montiel PO, Grubor-Lajsic G, Worland MR. Partial desiccation induced by sub-zero temperatures as a component of the survival strategy of the Arctic collembolan Onychiurus arcticus (Tullberg) J Insect Physiol. 1998;44(3–4):211–219. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1910(97)00166-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayward SAL, Rinehart JP, Sandro LH, Lee RE, Jr, Denlinger DL. Slow dehydration promotes desiccation and freeze tolerance in the Antarctic midge Belgica antarctica. J Exp Biol. 2007;210(5):836–844. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elnitsky MA, Hayward SAL, Rinehart JP, Denlinger DL, Lee RE., Jr Cryoprotective dehydration and the resistance to inoculative freezing in the Antarctic midge, Belgica antarctica. J Exp Biol. 2008;211(4):524–530. doi: 10.1242/jeb.011874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmstrup M, Bayley M, Ramløv H. Supercool or dehydrate? An experimental analysis of overwintering strategies in small permeable arctic invertebrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(8):5716–5720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082580699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lopez-Martinez G, et al. Dehydration, rehydration, and overhydration alter patterns of gene expression in the Antarctic midge, Belgica antarctica. J Comp Physiol B. 2009;179(4):481–491. doi: 10.1007/s00360-008-0334-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goto SG, et al. Functional characterization of an aquaporin in the Antarctic midge Belgica antarctica. J Insect Physiol. 2011;57(8):1106–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2011.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yi SX, et al. Function and immuno-localization of aquaporins in the Antarctic midge Belgica antarctica. J Insect Physiol. 2011;57(8):1096–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teets NM, Kawarasaki Y, Lee RE, Jr, Denlinger DL. Expression of genes involved in energy mobilization and osmoprotectant synthesis during thermal and dehydration stress in the Antarctic midge, Belgica antarctica. J Comp Physiol B. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00360-012-0707-2. 10.1007/s00360-012-0707-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cornette R, et al. Identification of anhydrobiosis-related genes from an expressed sequence tag database in the cryptobiotic midge Polypedilum vanderplanki (Diptera; Chironomidae) J Biol Chem. 2010;285(46):35889–35899. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.150623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang MH, Marinotti O, Vardo-Zalik A, Boparai R, Yan GY. Genome-wide transcriptional analysis of genes associated with acute desiccation stress in Anopheles gambiae. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(10):e26011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matkin LM, Markow TA. Transcriptional regulation of metabolism associated with the increased desiccation resistance of the cactophilic Drosophila mojavensis. Genetics. 2009;182(4):1279–1288. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.104927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark MS, et al. Surviving the cold: molecular analyses of insect cryoprotective dehydration in the Arctic springtail Megaphorura arctica (Tullberg) BMC Genomics. 2009;10:328. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Timmermans MJ, Roelofs D, Nota B, Ylstra B, Holmstrup M. Sugar sweet springtails: On the transcriptional response of Folsomia candida (Collembola) to desiccation stress. Insect Mol Biol. 2009;18(6):737–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2009.00916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feder ME, Hofmann GE. Heat-shock proteins, molecular chaperones, and the stress response: evolutionary and ecological physiology. Annu Rev Physiol. 1999;61:243–282. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teets NM, et al. Uncovering molecular mechanisms of cold tolerance in a temperate flesh fly using a combined transcriptomic and metabolomic approach. Physiol Genomics. 2012;44(15):764–777. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00042.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Girardot F, Monnier V, Tricoire H. Genome wide analysis of common and specific stress responses in adult Drosophila melanogaster. BMC Genomics. 2004;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-5-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rinehart JP, et al. Continuous up-regulation of heat shock proteins in larvae, but not adults, of a polar insect. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(38):14223–14227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606840103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morimoto RI. Regulation of the heat shock transcriptional response: Cross talk between a family of heat shock factors, molecular chaperones, and negative regulators. Genes Dev. 1998;12(24):3788–3796. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.24.3788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldberg AL. Protein degradation and protection against misfolded or damaged proteins. Nature. 2003;426(6968):895–899. doi: 10.1038/nature02263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maiuri MC, Zalckvar E, Kimchi A, Kroemer G. Self-eating and self-killing: crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(9):741–752. doi: 10.1038/nrm2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee JH, et al. Sestrin as a feedback inhibitor of TOR that prevents age-related pathologies. Science. 2010;327(5970):1223–1228. doi: 10.1126/science.1182228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He CC, Klionsky DJ. Regulation mechanisms and signaling pathways of autophagy. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:67–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102808-114910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gorski SM, et al. A SAGE approach to discovery of genes involved in autophagic cell death. Curr Biol. 2003;13(4):358–363. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lisi S, Mazzon I, White K. Diverse domains of THREAD/DIAP1 are required to inhibit apoptosis induced by REAPER and HID in Drosophila. Genetics. 2000;154(2):669–678. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.2.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Korolchuk VI, Menzies FM, Rubinsztein DC. Mechanisms of cross-talk between the ubiquitin-proteasome and autophagy-lysosome systems. FEBS Lett. 2010;584(7):1393–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benoit JB, et al. Mechanisms to reduce dehydration stress in larvae of the Antarctic midge, Belgica antarctica. J Insect Physiol. 2007;53(7):656–667. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marron MT, Markow TA, Kain KJ, Gibbs AG. Effects of starvation and desiccation on energy metabolism in desert and mesic Drosophila. J Insect Physiol. 2003;49(3):261–270. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1910(02)00287-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kostál V, Zahradnícková H, Šimek P. Hyperprolinemic larvae of the drosophilid fly, Chymomyza costata, survive cryopreservation in liquid nitrogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(32):13041–13046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107060108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verbruggen N, Hermans C. Proline accumulation in plants: A review. Amino Acids. 2008;35(4):753–759. doi: 10.1007/s00726-008-0061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanson RW, Reshef L. Regulation of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (GTP) gene expression. Annu Rev Biochem. 1997;66:581–611. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hand SC, Menze MA, Toner M, Boswell L, Moore D. LEA proteins during water stress: Not just for plants anymore. Annu Rev Physiol. 2011;73:115–134. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hodkinson ID, et al. Feeding studies on Onychiurus arcticus (Tullberg) (Collembola, Onychiuridae) on West Spitsbergen. Polar Biol. 1994;14(1):17–19. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. TopHat: Discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(9):1105–1111. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Conesa A, et al. Blast2GO: A universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(18):3674–3676. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11(10):R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Young MD, Wakefield MJ, Smyth GK, Oshlack A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: Accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 2010;11(2):R14. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-2-r14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Efron B, Tibshirani R. On testing the significance of sets of genes. Ann. Appl. Stat. 2007;1(1):107–129. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.