Abstract

Phagosome maturation is an essential part of the innate and adaptive immune response. Although it is well established that several Ras-related proteins in brain (Rab) proteins become associated to phagosomes, little is known about how these phagosomal Rab proteins influence phagosome maturation. Here, we show a specific role for Rab34 and mammalian uncoordinated 13-2 (Munc13-2) in phagolysosome biogenesis and cargo delivery. Rab34 knockdown impaired the fusion of phagosomes with late endosomes/lysosomes and high levels of active Rab34 promoted this process. We demonstrate that Rab34 enhances phagosome maturation independently of Rab7 and coordinates phagolysosome biogenesis through size-selective transfer of late endosomal/lysosomal cargo into phagosomes. More importantly, we show that Rab34 mediates phagosome maturation through the recruitment of the protein Munc13-2. Finally, we report that the alternative maturation pathway controlled by Rab34 is critical for mycobacterial killing because Rab34 silencing resulted in mycobacterial survival, and Rab34 expression led to mycobacterial killing. Altogether, our studies uncover Rab34/Munc13-2 as a critical part of an alternative Rab7-independent phagosome maturation machinery and lysosome-mediated killing of mycobacteria.

Keywords: LAMP-1, LAMP-2, phagocytosis

Phagocytosis is the process by which professional phagocytes ingest particles and microbes. After internalization, the resulting intracellular vacuoles, termed phagosomes, undergo dynamic changes by sequential acquisition of components from several intracellular compartments (1). This process is referred to as phagosome maturation and represents one of the first lines of defense against infection (2, 3).

Ras-related proteins in brain (Rab) proteins regulate intracellular trafficking events including phagosome maturation (4). Multiple Rab proteins are associated with phagosomes regulating the interactions of these organelles with endosomes and lysosomes (5–8). Many of these phagosomal Rab proteins are even recruited at the same time, although in some cases the kinetics is different (7, 9). Although the recruitment of several Rab GTPases is reported, the function of many individual phagosome-associated Rab proteins that contribute to phagosome maturation is poorly defined. The role of the most well-characterized Rab proteins in phagosome maturation is described (10). For example, both Rab5 and Rab7 are recruited into phagosomes, modulating its maturation (10). However, Rab7 is not sufficient to induce fusion of phagosomes with late endocytic organelles (11). This argues for the existence of as yet unidentified Rab proteins that regulate phagolysosome biogenesis.

Rab34 is a member of the Rab family that participates, from its location in the Golgi complex, in the modulation of the spatial positioning of lysosomes (12). Rab34 has also been associated with the post-Golgi secretory pathway (13) and with phagosomes (9, 14). Additionally, Rab34 has been reported to interact with the vesicle priming protein mammalian uncoordinated 13-2 (Munc13-2) regulating secretion during hyperglycemia (13, 15). At the transcriptional level, Rab34 is up-regulated via NF-κB during mycobacterial killing in phagolysosomes (16). These observations argue for the involvement of this small GTPase in phagosome biology (16). However, little is known about the specific function of Rab34 in phagosome dynamics.

Here, we demonstrate that increased levels of active Rab34 enhanced phagosome maturation. In contrast, when Rab34 is silenced, the acquisition of either luminal or membrane lysosomal markers is significantly lower. This GTPase regulates the delivery of size-selective cargo from late endosomes and lysosomes (collectively referred to as lysosomes for simplicity), distinct from what has been shown for Rab7. More importantly, we report that the Rab34 effector Munc13-2 is recruited via Rab34 into phagosomes, and in macrophages lacking Munc13-2, phagosome maturation is hampered. Finally, we show that both Rab34 and Munc13-2 are critical for the killing of intracellular mycobacteria by macrophages. We postulate that Rab34 modulates the delivery of large luminal cargo and lysosomal membrane proteins to phagosomes via a distinct mechanism from Rab7, with important consequences for elimination of intracellular mycobacteria.

Results

Active Rab34 Regulates Phago-Lysosome Fusion.

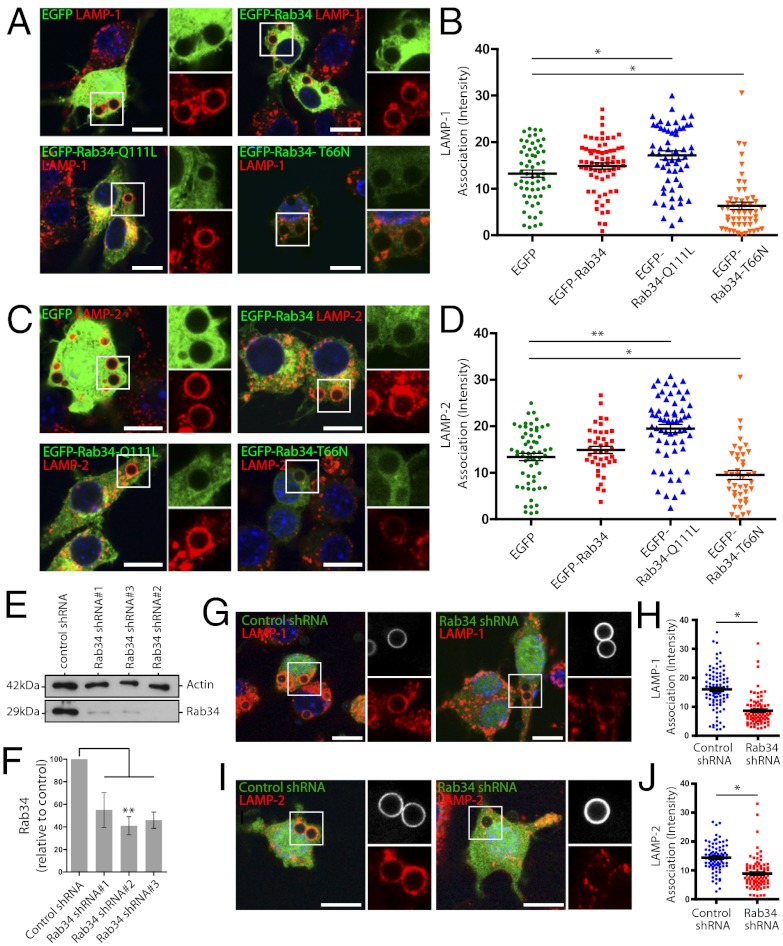

In macrophages, endogenous and expressed Rab34 is associated not only to the Golgi complex but also to late endosomes (Figs. S1 and S2). Using electron microscopy and Western blot detection of Rab34 in isolated phagosomes, we confirmed that Rab34 is present on phagosomes (Fig. S3 A–C). However, live cell imaging revealed that Rab34 transiently associates to phagosomes (Fig. S3 D–G) through the fusion of the Rab34-positive lysosomal vesicles (Fig. S3 H–J). Considering the dynamic association of Rab34 to phagosomes, we analyzed the impact of the expression of EGFP-Rab34 and mutants on phagosome maturation. The rate of bead internalization was not significantly affected by expression of Rab34 WT and mutants as shown by flow cytometry (Fig. S4). Single phagosome analysis revealed that the expression of EGFP-Rab34-Q111L (constitutively active mutant) increased the amount of lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP-1) and LAMP-2 associated to phagosomes (Fig. 1 A–D). In contrast, expression of the EGFP-Rab34-T66N (dominant negative mutant) significantly decreased both LAMP-1 and LAMP-2 association (Fig. 1 A–D). To confirm these observations, we used the pSIREN system to express small hairpin RNA (shRNA) to knockdown Rab34 (17). The vector also expressed the DsRed fluorescent protein to monitor Rab34 silencing by microscopy. To test silencing efficiency, transfected macrophages were sorted based on the expression of DsRed and the levels of Rab34 analyzed by Western blot. Expressed oligomers significantly depleted Rab34 levels; oligo 2, in particular, decreased Rab34 levels around 50% or lower (Fig. 1 E and F). Macrophages expressing the scrambled shRNA and Rab34 shRNA oligo 2 were incubated with beads, and phagosome maturation was analyzed in DsRed-positive cells. Rab34 knockdown significantly reduced the amount of both LAMP-1 and LAMP-2 associated with phagosomes relative to cells expressing the scrambled shRNA (Fig. 1 G–J). Thus, increased levels of Rab34 enhanced phagolysosome biogenesis, whereas expression of the dominant negative mutant and Rab34 knockdown impaired this process.

Fig. 1.

Rab34 is required for phagosome maturation, (A) Macrophages expressing the different constructs were incubated with fluorescent beads for 30 min of pulse and 30 min of chase and stained for LAMP-1. (B) Quantitative analysis of LAMP-1 fluorescence intensity associated with phagosomes. (C) Association of LAMP-2 to phagosomes as in A. (D) Quantitative analysis of LAMP-2 fluorescence intensity associated with phagosomes as indicated in B. (E) Rab34 was silenced by transfection with the pSIREN vector expressing the Rab34-shRNA oligomers (1, 2, or 3) or the scrambled shRNA as control. Cells were sorted based on DsRed signal and analyzed by Western blot to detect endogenous Rab34. Actin was used as loading control. (F) Quantification of Rab34 levels from three independent experiments. (G) Representative images of Rab34 silenced (oligo 2, pSIREN pseudocolored in green) and control cells stained for LAMP-1. (H) Quantitative analysis of LAMP-1 fluorescence intensity associated to phagosomes. (I) Association of LAMP-2 association to phagosomes as in G. (J) Quantitative analysis of LAMP-2 association to phagosomes as in H. Data show one representative experiment out of three in which at least 45 cells were analyzed. Mean ± SEM; *P ≤ 0.01; **P ≤ 0.001 from two-tailed Student t test. (Scale bar, 10 µm.) (Inset magnification: A and C: ∼2.5×, G and I: ∼2×.)

Rab34 Regulates Size-Selective Lysosomal Cargo Delivery to Phagosomes.

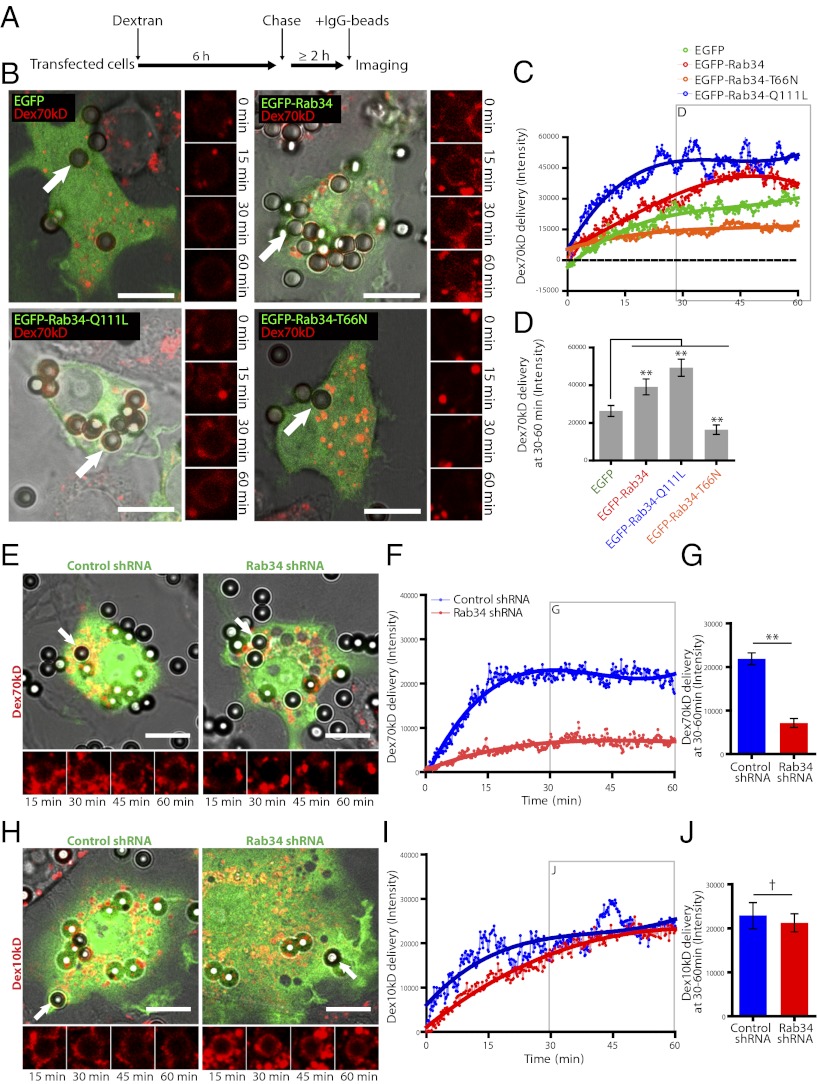

We next analyzed the impact of Rab34 in the transfer of cargo preloaded in lysosomes into phagosomes (Fig. 2A). The expression of both EGFP-Rab34 and EGFP-Rab34-Q111L significantly increased the rate of Dex70kDa delivery during the first hour of phagosome maturation (Fig. 2 B–D), whereas Dex70kDa delivery was severely impaired in macrophages expressing EGFP-Rab34-T66N (Fig. 2 B–D). Strikingly, phagosomes in macrophages silenced for Rab34 acquired significantly less Dex70kDa during the first hour compared with the scrambled control (Fig. 2 E–G; Movie S1). Phagosomes undergo transient contact with endocytic organelles, and the delivery of size-dependent contents to phagosomes displays different kinetics (10, 18, 19). Therefore, we investigated the possibility that Rab34 regulates a size-selective mechanism of cargo transfer at the molecular level. A lower-molecular-weight dextran (Dex10kDa) was more efficiently distributed in the endo/lysosomal tubular network as previously reported (20). Strikingly, the knockdown of Rab34 did not have a significant effect on the acquisition of preloaded Dex10kDa by phagosomes during the first hour of phagocytosis (Fig. 2 H–J; Movie S2). Because Dex10kDa and Dex70kDa were found mostly in the same compartments (Fig. S5), we concluded that Rab34 is required for the delivery of the high- (Dex70kDa) but not the lower-(Dex10kDa)-molecular-weight luminal cargo. This indicates that Rab34 regulates size-selective transfer of lysosomal cargo into phagosomes.

Fig. 2.

Rab34 regulates size-selective cargo delivery into phagosomes. (A) Outline of the protocol followed for lysosomal compartment preloading in transfected macrophages before phagocytosis of beads. (B) Analysis of delivery of preloaded Dex70kDa to phagosomes in Rab34 expressing macrophages during the first hour. The phagosomes in the Insets are indicated with white arrows. (C) Quantitative analysis of the Dex70kDa delivered to phagosomes. The curve shows the average of at least five phagosomes from three independent experiments, plotted with a third-degree polynomial regression curve fitting. (D) Data points from 30 to 60 min in E were pooled. (E) Analysis of delivery of preloaded Dex70kDa to phagosomes in Rab34 silenced and control macrophages (pSIREN pseudocolored green) during the first hour. The phagosomes in the Insets are indicated with white arrows (Movie S1). (F) Quantitative analysis of the Dex70kDa delivered to phagosomes. The curve shows the average of at least five phagosomes from three independent experiments, plotted with a third-degree polynomial regression curve fitting. (G) Data points from 30 to 60 min in F were pooled. (H) Analysis of delivery of preloaded Dex10kDa to phagosomes as in E (Movie S2). (I) Quantitative analysis of the fluorescence signal intensity of Dex10kDa delivered to phagosomes as in F. (J) Quantitative analysis as in G. Data show mean ± SD; †P > 0.01; **P ≤ 0.001 from two-tailed Student t test. (Scale bar, 10 µm.) (Inset magnification: ∼2×.)

Role of Rab34 in Phago-Lysosome Fusion Is Independent of Rab7.

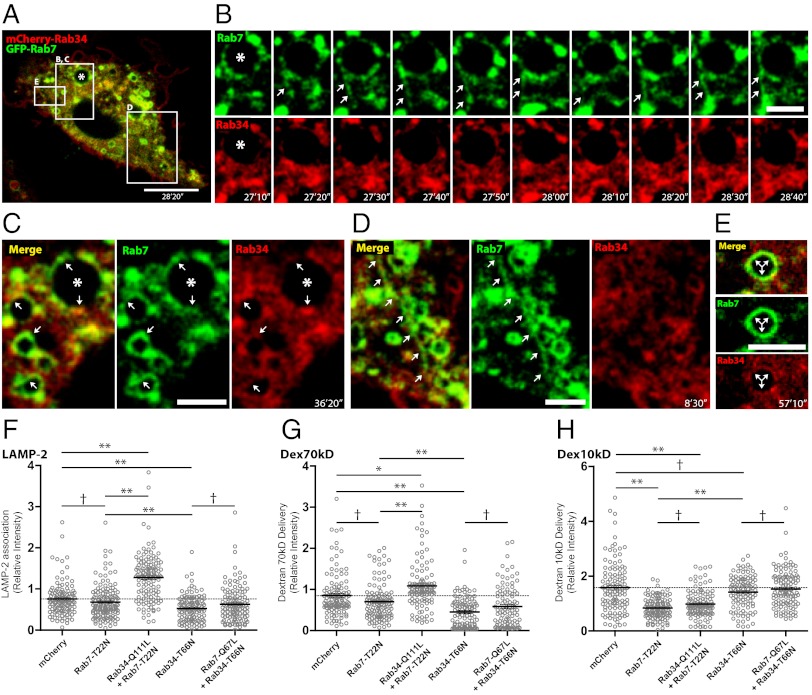

Because Rab7 is also important in phagolysosome biogenesis, we investigated these seemingly overlapping effects. The dynamic localization of Rab34 and Rab7 in cells coexpressing EGFP-Rab7 and mCherry-Rab34 was strikingly different (Fig. 3A; Movie S3). Whereas Rab34 transiently associated with phagosomes, Rab7 was continuously present on phagosomes as shown before (Fig. 3 B and C). Moreover, Rab7, but not Rab34, was localized on tubular structures originated from lysosomes and phagosomes (Fig. 3D; Movie S3).

Fig. 3.

Rab34 size-selective cargo delivery to phagosomes is independent of Rab7, (A) Phagosome (asterisk) maturation in macrophages coexpressing EGFP-Rab7 and mCherry-Rab34 (Movie S3). (B) Rab7-positive, Rab34-negative tubule extended from the phagosome (white arrows). (C) Expressed Rab7 and Rab34 partially colocalized in phagosomes and endocytic vesicles (white arrows). (D) Extended tubular vesicle, positive for Rab7 and negative for Rab34. (E) Endocytic vesicle with strong EGFP-Rab7, but no mCherry-Rab34 association. (Scale bars, 10 µm in A, 3 µm in B–D, and 2 µm in E.) Time stamp refers to the event in Movie S3. (F) Quantification of LAMP-2 fluorescence signal intensity associated to phagosomes in expressing or coexpressing cells, relative to nonexpressing cells in the same field as the internal control. (G) Quantification of Dex70kDa fluorescence signal intensity associated to phagosomes quantification as indicated in F. (H) Quantification of Dex10kDa fluorescence signal intensity associated to phagosomes as indicated in G. Data show mean ± SEM from four independent experiments, with at least 30 cells evaluated in each. †P > 0.01; *P ≤ 0.01; **P ≤ 0.001 from two-tailed Student t test.

Expression of the dominant negative mutant of Rab7 (EGFP-Rab7-T22N) significantly decreased delivery of Dex10kDa as reported before (11) but not the delivery of Dex70kDa or LAMP-2 association to phagosomes during the first hour (Fig. 3 F–H). However, the expression of the constitutively active mutant of Rab7 (EGFP-Rab7-Q67L) did not affect Dex10kDa and Dex70kDa delivery or LAMP-2 acquisition (Fig. S6). The coexpression of Rab34-Q111L with Rab7-T22N significantly increased LAMP-2 levels (Fig. 3F) and Dex70kDa delivery (Fig. 3G), but not Dex10kDa delivery (Fig. 3H), compared with cells expressing only Rab7-T22N. Conversely, the coexpression of Rab7-Q67L with Rab34-T66N did not significantly increase the LAMP-2 levels on phagosomes (Fig. 3F) or Dex10kDa delivery (Fig. 3H) compared with cells expressing only Rab34-T66N. However, in cells coexpressing Rab7-Q67L and Rab34-T66N, Dex70kDa delivery significantly increased compared with cells expressing Rab34-T66N alone (Fig. 3G) but not relative to the control expressing only mCherry.

Both Rab34 and Rab7 interact with the Rab-interacting lysosomal protein (RILP). However, in Rab34 knockdown cells, the protein levels of RILP were not affected (Fig. S7). The expression of a truncated form of RILP (RILP-C33) that exert an inhibitory effect downstream of Rab7 (6) only decreased Dex10kDa delivery but not Dex70kDa delivery or LAMP-2 association (6) (Fig. S7). In addition, the expression of the Rab34-K82Q mutant unable to bind RILP (12) did not significantly affect LAMP-2 association to phagosomes or Dex10kDa and Dex70kDa delivery (Fig. S7). Altogether, these observations are consistent with a role of Rab34 in increasing phagolysosome biogenesis that is independent of Rab7 and RILP.

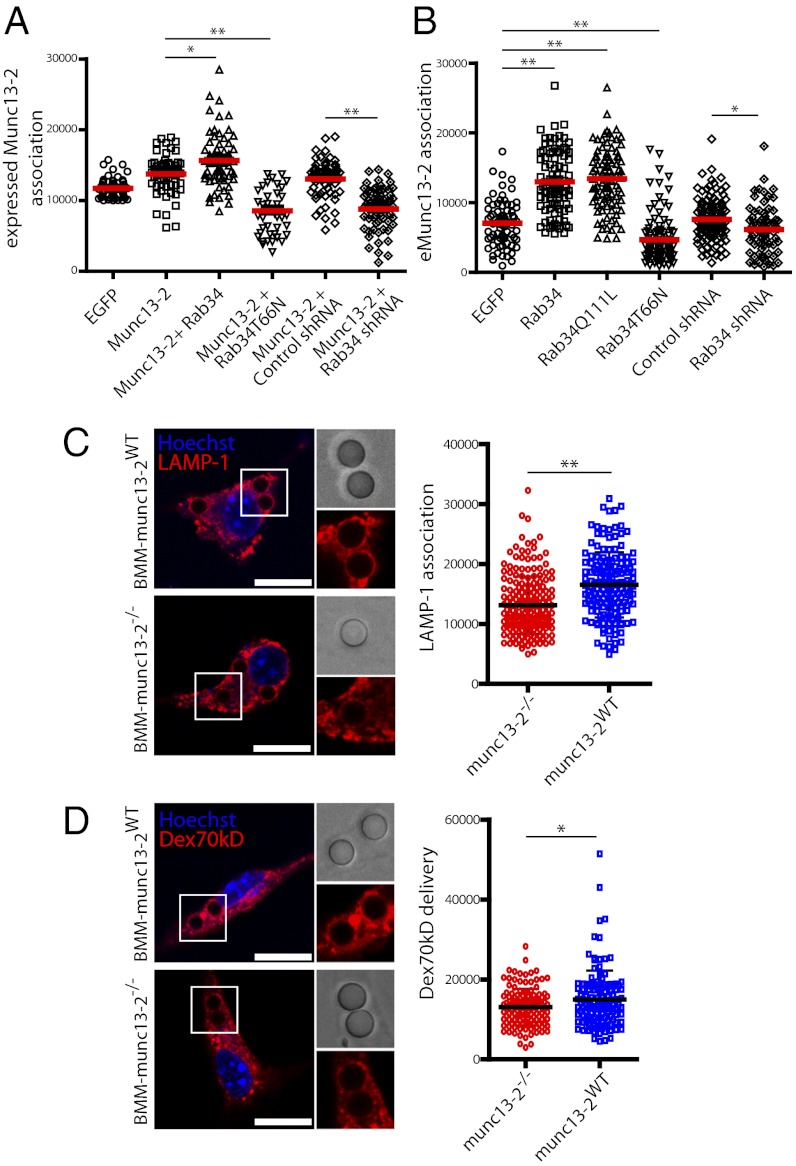

Munc13-2 Is Recruited to Phagosomes by Rab34 and Is Required for Phago-Lysosome Fusion.

Munc13-2 has been reported as a Rab34 effector (15), but the possibility that this interaction has a functional role during the phagocytic pathway has not been explored. Munc13 proteins are members of the protein kinase C (PKC) superfamily. The different Munc13 isoforms have been mainly associated to the regulation of neurotransmitter release (21) and lysosomal secretion (22, 23). Munc13-2 was associated to purified phagosomes (Fig. S8). To investigate the contribution of Rab34 to the recruitment of Munc13-2 onto phagosomes, we expressed EGFP-Munc13-2 in macrophages. Strikingly, EGFP-Munc13-2 localizes in early phagosomes, and overexpression of mCherry-Rab34 increased this association to phagosomes (Fig. S8; Fig. 4A). In contrast, expression of Rab34-T66N or Rab34 knockdown significantly impaired EGFP-Munc13-2 association with phagosomes (Fig. 4A). In agreement with these observations, overexpression of EGFP-Rab34 significantly enhanced endogenous Munc13-2 association with phagosomes (Fig. 4B). Conversely, the expression of the dominant negative mutant of Rab34 inhibited the recruitment of Munc13-2 to phagosomes (Fig. 4B). Accordingly, Rab34 knockdown also decreased the amount of endogenous Munc13-2 associated with phagosomes (Fig. 4B). Finally, phagosome maturation was significantly inhibited in bone marrow macrophages (BMMs) from Munc13-2−/− mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 4 C and D). Altogether, these data strongly suggest that Munc13-2 recruitment into phagosomes requires active Rab34, and this recruitment is necessary for the maturation of phagosomes.

Fig. 4.

Role of Munc13-2 in the Rab34-dependent regulation of phago-lysosome fusion, (A) Quantitative analysis of EGFP-Munc13-2 association to phagosomes under the different conditions. Data show mean ± SD from one representative experiment out of two with at least 50 cells analyzed in each. (B) Quantitative analysis of endogenous Munc13-2 association to phagosomes in macrophages expressing the indicated constructs. Data show mean ± SD from one representative experiment in which at least 50 cells were analyzed. (C) Association of LAMP-1 to phagosomes in Munc13-2 WT and KO mouse bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMMs). (Right) Quantitative analysis of LAMP-1 fluorescence intensity association to bead phagosomes. (D) Delivery of Dex70kDa to phagosomes in BMMs preloaded with Dex70kD. (Right) Quantitative analysis of Dex70kDa delivery to phagosomes. Mean ± SD from three experiments; at least 100 cells were analyzed. *P ≤ 0.01, **P ≤ 0.001, from two-tailed Student t test. (Scale bar, 10 µm.) (Inset magnification: ∼1.75×.)

Rab34 Modulates Intracellular Killing of Mycobacteria.

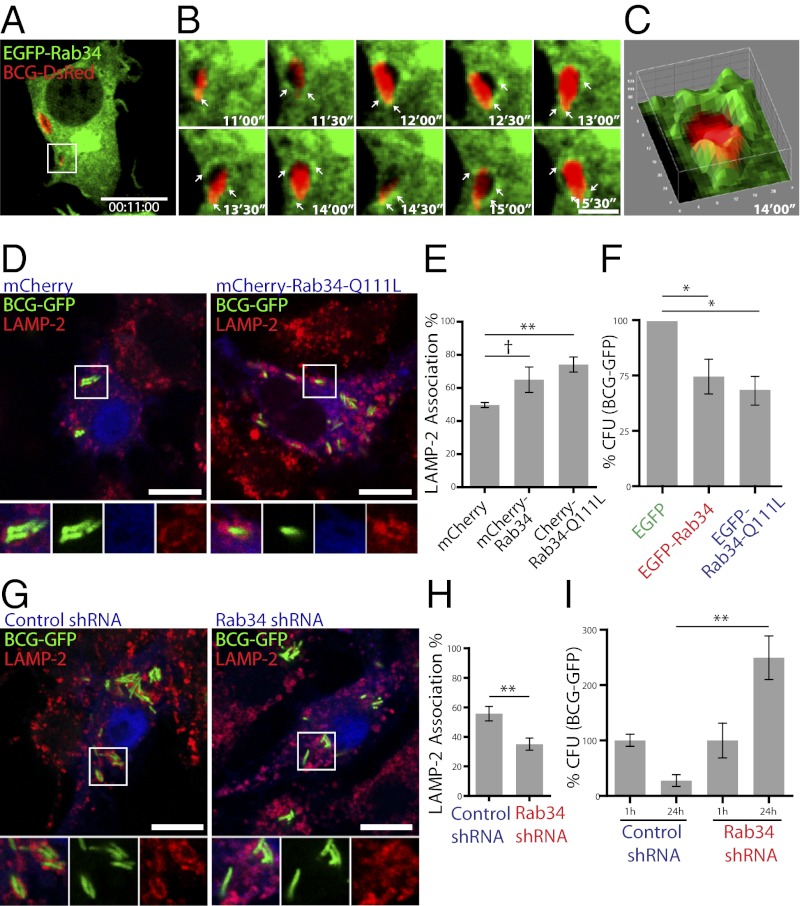

Because Rab34 is up-regulated under conditions where macrophages are able to kill mycobacteria (16), we investigated the functional role of Rab34 in this process. We found that EGFP-Rab34 was recruited to mycobacteria containing phagosomes during early time points of infection (Fig. 5 A–C; Movie S4). Considering that the expression of EGFP-Rab34 increased phago-lysosome fusion, we evaluated the effect of Rab34 overexpression or knockdown in macrophages infected with Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin-GFP. Strikingly, overexpression of mCherry-Rab34 and mCherry-Rab34-Q111L significantly increased the number of mycobacterial phagosomes positive for LAMP-2 (Fig. 5 D and E), correlating with increased killing of mycobacteria (Fig. 5F). Conversely, Rab34 knockdown significantly reduced the number of mycobacterial phagosomes positive for LAMP-2 (Fig. 5 G and H), leading to an increase in the number of intracellular mycobacteria (Fig. 5I). Mycobacterial survival was not caused by differences in internalization, because the Rab34 knockdown did not affect the extent of internalization (Fig. S4). Moreover, and confirming our observations with Munc13-2, in BMMs from Munc13-2−/−, the survival of mycobacteria was significantly higher (Fig. S8). Thus, our data identifies Rab34 and its effector Munc13-2 as regulators in the process of mycobacterial killing by macrophages.

Fig. 5.

Rab34 is required for the lysosome-mediated killing of mycobacteria, (A) Analysis of the association of EGFP-Rab34 to M. bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin-DsRed containing phagosomes during the early time points after phagocytosis (Movie S4). (B) Association of EGFP-Rab34 to mycobacterial phagosome (white arrows) (C) 3D surface plot at 14:00 s after uptake of mycobacteria. (Scale bars, 10 µm in A and 2 µm in B). (D) Macrophages transfected with the indicated constructs were infected with M. bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin-GFP, and cells were fixed and stained for LAMP-2. (E) Analysis of number of mycobacterial phagosomes positive for LAMP-2. Mean ± SD of three independent experiments; at least 100 cells were evaluated in each. (F) Macrophages selected for the expression of EGFP, EGFP-Rab34, or EGFP-Rab34-Q111L (pseudocolored blue) were infected with bacillus Calmette–Guérin-DsRed. After 24 h, cells were lysed, and cfu determined. Mean ± SEM of the percentage of bacteria recovered compared with control cells from two independent experiments. (G) Rab34 silenced and control cells (pseudocolored blue) were infected with bacillus Calmette–Guérin-GFP as described in D and stained for LAMP-2. (H) Analysis of number of mycobacterial phagosomes positive for LAMP-2 as in E. (I) Rab34 silenced and control cells were sorted and infected with bacillus Calmette–Guérin-GFP. After 1 and 24 h of infection, macrophages were lysed and cfu determined. Data show mean ± SEM of the percentage of bacteria recovered compared with control cells from two independent experiments. †P > 0.01; *P ≤ 0.01; **P ≤ 0.001 from two-tailed or two-paired Student t test. (Inset magnification: ∼1.75×.)

Discussion

Although Rab34 has been associated to phagosome maturation (9, 14), its specific function in this process has not been defined. In this study, we provide direct evidence that Rab34 expression levels are important for the fusion of lysosomes with phagosomes. Rab34 knockdown or Rab34 dominant negative mutant expression not only impaired the delivery of luminal cargo (Dex70kDa) but also the association of lysosomal membrane glycoproteins to phagosomes.

Two alternative explanations can be evoked about the remarkable size specificity in cargo delivery to phagosomes controlled by Rab34. First, compelling evidence indicates that late endosomal compartments are highly heterogeneous, and different compartments contribute to phagosome maturation (24, 25). Therefore, Rab34 could specifically regulate fusion of a distinct subset of late endosomes with phagosomes. However, Rab34 regulation of a subset of lysosomal compartments cannot fully explain our data, because in our experiments, both dextrans are mostly localized in the same compartments, as reported before (18, 19). A second possible scenario is that the smaller Dex10kDa molecules do not require full fusion events to be transferred between compartments (18, 26, 27). In contrast, larger molecules such as Dex70kDa would require full fusion, and their efficient transfer to the phagosome could be limited by their molecular size. Supporting this notion, low-molecular-weight solutes are transferred more rapidly to phagosomes than those of larger molecular weight (18, 19). This size dependence is also evident in events of “kiss and run,” where low-molecular-size molecules are freely transferred, whereas in full fusion events, both low- and higher-molecular-size molecules can be efficiently delivered (18, 20, 28). The existence of a size-selective differential mechanism for delivery of molecules to phagosomes has been long postulated. We identified the existence of at least one small GTPase that specifically controls such a mechanism at the molecular level, arguing for an important physiological function. Moreover, our data provide evidence for the hypothesis that the complex and dynamic profile of different enzymes and membrane-associated receptors in the phagosome could be regulated, at least in part, by this mechanism (29, 30).

Proteomic data (8, 9) indicate that multiple Rab proteins are associated with phagosomes during maturation. Other Rab proteins such as Rab5 (11), Rab14 (31), and Rab10 (32) have been reported to be involved in phagosome maturation. Rab7 is important for lysosome function and position (6, 33) and also contributes to phagosome maturation (11, 14). Here, we show that Rab34 is a major player in the delivery of membrane and luminal components to phagosomes in a manner distinct from Rab7. Our data argue that Rab34 participates in additional mechanisms of Rab7-independent phagosome maturation, as suggested by Vieira and colleagues (11). Although localized to lysosomal vesicles, Rab34 was strikingly absent from dynamic tubular structures, in contrast to Rab7. This is in agreement with the observation that Salmonella-containing phagosomes recruit Rab7 but not Rab34 (7). In addition, the vacuole resulting from VacA toxin of Helicobacter pylori treatment strongly recruits Rab7 but not Rab34, although these Rab proteins are both lysosome associated (34). LAMP-1 and LAMP-2 association to phagosomes is strongly dependent on the level of active Rab34 present in macrophages and much less dependent on the presence of Rab7. Therefore, we postulate that Rab34 and Rab7 modulate two distinct mechanisms of delivery of different types of cargo and membrane proteins during phagolysosome formation (Fig. S9). It is conceivable that, although Rab7 modulates fusion events of more homogenously distributed late endosomes, Rab34 plays a role in the less dynamic lysosomes or terminal compartments as defined previously (35). This hypothesis is consistent with previous studies showing that Mycobacterium- and Legionella-containing phagosomes acquire Rab7 but not LAMP-1 (36) and that mycobacterial phagosomes acquire LAMP-2 independently of Rab7 (37).

Munc13 proteins have been mainly related to vesicle fusion with the plasma membrane and not associated with processes of vesicle-to-vesicle fusion. Based on the data reported here, Munc13-2 also participates in phago-lysosome fusion and mycobacterial killing. We propose that Rab34 and Munc13-2 could control the recruitment of tethering factors to facilitate the targeting of lysosomes to phagosomes, enhancing priming and fusion (Fig. S9). However, the cognate complexes participating in this process remain to be identified. Given that Munc13 proteins are regulated by diacylglycerol (DAG), our data provide an alternative mechanism by which phorbol esters stimulate phagosome maturation (38, 39). However, PKC is also present on phagosomes and whether phorbol esters operate via Munc13-2, PKC, or both remains to be determined.

Rab34 expression is up-regulated during the killing of mycobacteria by macrophages (16), and it has been reported that Rab34 transiently associates with mycobacterial phagosomes (14). Based on these observations, a role for Rab34 in mycobacterial killing has been suggested but not formally demonstrated until now. We show here that the mechanism regulated by Rab34 clearly has a significant impact on the innate immune response, because blocking this pathway leads to improved mycobacteria survival. Our studies also reveal the Rab34/Munc13-2 cascade as an additional modulator of phagosome maturation. We postulate that Rab34 regulates an early process during phagosome maturation that likely involves the delivery of specific lysosomal content to phagosomes. Further studies will determine the qualitative and quantitative aspects of the Rab34-dependent transfer of lysosomal components, which are required to eliminate intracellular mycobacteria by macrophages.

Materials and Methods

A summary of the material and methods is presented in the following section; further details are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Cells and Reagents.

RAW 264.7 macrophages were grown in high glucose DMEM with 10% (vol/vol) heat inactivated FCS incubated at 37 °C in a 5% (vol/vol) CO2 atmosphere. BMMs were obtained as described before (40). M. bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin expressing GFP and DsRed were kind gifts of Brigitte Gicquel (Institute Pasteur, Paris, France). EGFP-Rab34, EGFP-Rab34-Q111L, and EGFP-Rab34-T66N plasmids were previously described (12). mCherry-Rab34 plasmids were subcloned from the EGFP-Rab34 plasmids. The RNAi-Ready pSIREN-RetroQ-DsRed-Express vector was from Clontech. EGFP-Munc13-2 was cloned as previously described (18). Anti-Rab34 antibody and mouse anti-β-actin were from Abcam. Rabbit polyclonal α-Munc13-2 antibody was from Abgent. The C57BL/6 Munc-13–2−/− mouse was previously described (41).

IgG Coating of Microbeads.

Carboxylated latex microspheres (Polysciences) or polystyrene microparticles (Kisker Biotech) were coupled to 50 µg mouse DyLight 649–conjugated IgG (Dianova) or mouse IgG (Rockland) as described before (17).

Phagosome Isolation.

Macrophages were pulsed with 1-µm beads and isolated after 15, 30, and 60 min of chase as described before (40).

Indirect Immunofluorescence.

Macrophages were processed as described before (17) and analyzed (Fig. S10) using a Leica SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems).

Rab34 Knockdown with the pSIREN System.

Rab34-shRNA oligomers were designed based on Rab34-siRNA for Mus musculus. Oligomers (Eurofins MWG Operon) were inserted into the linear RNAi-Ready pSIREN-RetroQ-DsRed-Express (Clontech) in addition to the provided scrambled shRNA oligomer. After a 24-h transfection, cells were scraped, sorted for DsRed signal at a purity of 75–80% using a BD Aria II Cell Sorter (BD Bioscience), and used for experiments.

Image Analysis.

Analysis was performed using ImageJ (National Institute of Health). Iterative versions of ImageJ used for this work are 1.41m through 1.47b.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical calculations and normalizations were performed using GraphPad Prism software. P values were calculated using Student two-tailed t test or one-way ANOVA and Dunnett's multiple comparison posttest as indicated for each case. Curve averaging was performed using Origin 8.5 scientific plotting software (OriginLab).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Brose and Dr. Reim (Max Planck Institute of Experimental Medicine) for providing the Munc13-2−/− mice and Munc13-2 plasmids. We also thank Gareth Griffiths, Marisa Colombo, Luis Mayorga, and members of the Phagosome Biology Laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript. M.G.G. is supported by a Helmholtz Young Investigator grant (Initiative and Networking funds of the Helmholtz Association).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. S.G. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1206811109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Stuart LM, Ezekowitz RA. Phagocytosis: Elegant complexity. Immunity. 2005;22(5):539–550. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flannagan RS, Cosío G, Grinstein S. Antimicrobial mechanisms of phagocytes and bacterial evasion strategies. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(5):355–366. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jutras I, Desjardins M. Phagocytosis: At the crossroads of innate and adaptive immunity. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:511–527. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.102755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stenmark H. Rab GTPases as coordinators of vesicle traffic. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10(8):513–525. doi: 10.1038/nrm2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garin J, et al. The phagosome proteome: Insight into phagosome functions. J Cell Biol. 2001;152(1):165–180. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.1.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrison RE, Bucci C, Vieira OV, Schroer TA, Grinstein S. Phagosomes fuse with late endosomes and/or lysosomes by extension of membrane protrusions along microtubules: Role of Rab7 and RILP. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(18):6494–6506. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.18.6494-6506.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith AC, et al. A network of Rab GTPases controls phagosome maturation and is modulated by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Cell Biol. 2007;176(3):263–268. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200611056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trost M, et al. The phagosomal proteome in interferon-gamma-activated macrophages. Immunity. 2009;30(1):143–154. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rogers LD, Foster LJ. The dynamic phagosomal proteome and the contribution of the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(47):18520–18525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705801104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vieira OV, Botelho RJ, Grinstein S. Phagosome maturation: Aging gracefully. Biochem J. 2002;366(Pt 3):689–704. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vieira OV, et al. Modulation of Rab5 and Rab7 recruitment to phagosomes by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(7):2501–2514. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.7.2501-2514.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang T, Hong W. Interorganellar regulation of lysosome positioning by the Golgi apparatus through Rab34 interaction with Rab-interacting lysosomal protein. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13(12):4317–4332. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-05-0280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldenberg NM, Grinstein S, Silverman M. Golgi-bound Rab34 is a novel member of the secretory pathway. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(12):4762–4771. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-11-0991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seto S, Tsujimura K, Koide Y. Rab GTPases regulating phagosome maturation are differentially recruited to mycobacterial phagosomes. Traffic. 2011;12(4):407–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Speight P, Silverman M. Diacylglycerol-activated Hmunc13 serves as an effector of the GTPase Rab34. Traffic. 2005;6(10):858–865. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gutierrez MG, et al. NF-kappa B activation controls phagolysosome fusion-mediated killing of mycobacteria by macrophages. J Immunol. 2008;181(4):2651–2663. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang C, et al. GODZ-mediated palmitoylation of GABA(A) receptors is required for normal assembly and function of GABAergic inhibitory synapses. J Neurosci. 2006;26(49):12758–12768. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4214-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desjardins M, Nzala NN, Corsini R, Rondeau C. Maturation of phagosomes is accompanied by changes in their fusion properties and size-selective acquisition of solute materials from endosomes. J Cell Sci. 1997;110(Pt 18):2303–2314. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.18.2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang YL, Goren MB. Differential and sequential delivery of fluorescent lysosomal probes into phagosomes in mouse peritoneal macrophages. J Cell Biol. 1987;104(6):1749–1754. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.6.1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berthiaume EP, Medina C, Swanson JA. Molecular size-fractionation during endocytosis in macrophages. J Cell Biol. 1995;129(4):989–998. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.4.989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Betz A, et al. Munc13-1 is a presynaptic phorbol ester receptor that enhances neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 1998;21(1):123–136. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80520-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feldmann J, et al. Munc13-4 is essential for cytolytic granules fusion and is mutated in a form of familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (FHL3) Cell. 2003;115(4):461–473. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00855-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neeft M, et al. Munc13-4 is an effector of rab27a and controls secretion of lysosomes in hematopoietic cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16(2):731–741. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-10-0923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anes E, et al. Dynamic life and death interactions between Mycobacterium smegmatis and J774 macrophages. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8(6):939–960. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perret E, Lakkaraju A, Deborde S, Schreiner R, Rodriguez-Boulan E. Evolving endosomes: How many varieties and why? Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17(4):423–434. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Desjardins M. Biogenesis of phagolysosomes: The ‘kiss and run’ hypothesis. Trends Cell Biol. 1995;5(5):183–186. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)88989-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duclos S, et al. Rab5 regulates the kiss and run fusion between phagosomes and endosomes and the acquisition of phagosome leishmanicidal properties in RAW 264.7 macrophages. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 19):3531–3541. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.19.3531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bright NA, Gratian MJ, Luzio JP. Endocytic delivery to lysosomes mediated by concurrent fusion and kissing events in living cells. Curr Biol. 2005;15(4):360–365. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Claus V, et al. Lysosomal enzyme trafficking between phagosomes, endosomes, and lysosomes in J774 macrophages. Enrichment of cathepsin H in early endosomes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(16):9842–9851. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rohde K, Yates RM, Purdy GE, Russell DG. Mycobacterium tuberculosis and the environment within the phagosome. Immunol Rev. 2007;219:37–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kyei GB, et al. Rab14 is critical for maintenance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis phagosome maturation arrest. EMBO J. 2006;25(22):5250–5259. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cardoso CM, Jordao L, Vieira OV. Rab10 regulates phagosome maturation and its overexpression rescues Mycobacterium-containing phagosomes maturation. Traffic. 2010;11(2):221–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.01013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bucci C, Thomsen P, Nicoziani P, McCarthy J, van Deurs B. Rab7: A key to lysosome biogenesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11(2):467–480. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.2.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Terebiznik MR, et al. Helicobacter pylori VacA toxin promotes bacterial intracellular survival in gastric epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2006;74(12):6599–6614. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01085-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pillay CS, Elliott E, Dennison C. Endolysosomal proteolysis and its regulation. Biochem J. 2002;363(Pt 3):417–429. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3630417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clemens DL, Lee BY, Horwitz MA. Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Legionella pneumophila phagosomes exhibit arrested maturation despite acquisition of Rab7. Infect Immun. 2000;68(9):5154–5166. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.9.5154-5166.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seto S, Matsumoto S, Ohta I, Tsujimura K, Koide Y. Dissection of Rab7 localization on Mycobacterium tuberculosis phagosome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;387(2):272–277. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.06.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kielian MC, Cohn ZA. Phorbol myristate acetate stimulates phagosome-lysosome fusion in mouse macrophages. J Exp Med. 1981;154(1):101–111. doi: 10.1084/jem.154.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trivedi V, et al. Immunoglobulin G signaling activates lysosome/phagosome docking. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(48):18226–18231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609182103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wähe A, et al. Golgi-to-phagosome transport of acid sphingomyelinase and prosaposin is mediated by sortilin. J Cell Sci. 2010;123(Pt 14):2502–2511. doi: 10.1242/jcs.067686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenmund C, et al. Differential control of vesicle priming and short-term plasticity by Munc13 isoforms. Neuron. 2002;33(3):411–424. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00568-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.