Abstract

DNA methylation regulates gene expression in a cell-type specific way. Although peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) comprise a heterogeneous cell population, most studies of DNA methylation in blood are performed on total mononuclear cells. In this study, we investigated high resolution methylation profiles of 58 CpG sites dispersed over eight immune response genes in multiple purified blood cells from healthy adults and newborns. Adjacent CpG sites showed methylation levels that were increasingly correlated in adult blood vs. cord blood. Thus, while interindividual variability increases from newborn to adult blood, the underlying methylation changes may not be merely stochastic, but seem to be orchestrated as clusters of adjacent CpG sites. Multiple linear regression analysis showed that interindividual methylation variability was influenced by distance of average methylation levels to the closest border (0 or 100%), presence of transcription factor binding sites, CpG conservation across species and age. Furthermore, CD4+ and CD14+ cell types were negative predictors of methylation variability. Concerns that PBMC methylation differences may be confounded by variations in blood cell composition were justified for CpG sites with large methylation differences across cell types, such as in the IFN-γ gene promoter. Taken together, our data suggest that unsorted mononuclear cells are reasonable surrogates of CD8+ and, to a lesser extent, CD4+ T cell methylation in adult peripheral, but not in neonatal, cord blood.

Keywords: DNA methylation, interindividual variability, immune response genes, cord blood, peripheral blood

Introduction

DNA methylation patterns are erased and re-established each generation during embryogenesis and gametogenesis.1 Throughout development, cell-type specific gene expression is achieved through epigenetic changes in chromatin structure.2 Active genes tend to have decreased methylation levels at TSS and increased methylation at gene bodies.3 In blood, DNA methylation regulates differentiation from hematopoietic stem cells to the entire spectrum of mature cells,4,5 including the expression of cytokine genes6 and the control of immunoglobulin gene rearrangements.7 At birth, blood methylation profiles tend to be more concordant within monozygotic twins than in dizygotic twins, indicating a substantial genetic contribution to methylation patterns.8,9 Methylation levels have also been associated with genomic sequence and structure in adult blood cells.10-12 In principle, methylation levels are mitotically stable.13 Nevertheless, there is increasing evidence that environmental and stochastic factors modulate methylation from intrauterine to postnatal life.14-19 Pediatric research suggests that postnatal changes in methylation happen increasingly in childhood, and particularly during the first year of life.20,21

Efforts to characterize variability of DNA methylation among healthy individuals have shown that methylation levels vary across individuals22-25 and cell types,26-30 and are subject to intra-individual changes over time.31,32 Epigenetic drift—divergence in methylation patterns due to small defects in transmitting methylation marks through successive cell divisions, or in maintaining them in differentiated cells—has been associated with age-dependent methylation changes.14 Studies that followed changes in methylation over time gave conflicting results. Global methylation characteristically decreases with age,33-36 which may be largely due to loss of repetitive element methylation.37 A longitudinal study by Bjornsson and colleagues suggests, however, that global methylation can either increase or decrease with age.31 There is also evidence that at least CpG-rich loci tend to gain, rather than lose methylation with time,38,39 while a study by Rakyan et al. showed that aging-associated hypermethylation preferentially occurred at bivalent chromatin domains, which harbor both active and inactive histone marks.40

Aberrant methylation patterns have been associated with cancer,41 autoimmune disease42 or psychiatric disorders.43 An increasing number of epidemiological studies try to identify changes in methylation levels in blood cells associated with environmental exposure or disease. Genome-wide comparison of methylation levels between multiple blood cell types revealed substantial differences in DNA methylation between cell types, suggesting that methylation differences measured in whole blood or PBMCs may be biased by differential blood composition.30

In the present study, we investigated interindividual variability and patterns of DNA methylation within eight immune response genes in multiple purified blood cell types from adults and newborns. Detailed methylation analysis revealed patterns of co-regulated CpG sites that were already detectable in cord blood and became more prominent in adult blood. Comparing the results from purified cell populations with CBMCs or PBMCs revealed that apparent methylation levels can be influenced by the cellular composition of the blood and may not be representative of cell types relevant for gene expression.

Results

We analyzed CBMCs and PBMCs from 30 mother-newborn pairs. Twelve CBMC and 12 unrelated PBMC samples were sorted into five different cell types (CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, CD14+ monocytes, CD19+ B cells and CD56+ natural killer cells) in order to investigate methylation levels in each subpopulation. In addition, CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells were isolated from CBMCs. All purified subpopulations were compared with P/CBMCs from which they were purified. Furthermore, PBMCs and CBMCs from mother-newborn pairs were compared with each other. High resolution methylation profiles of 8 immune response genes were obtained by bisulfite sequencing using either pyrosequencing or 454 deep sequencing (GS FLX, Roche). We selected eight immune response genes (IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, Il-8, KIR2DL4 and TNF-α), which have previously been described to be regulated by promoter methylation or shown to be differentially methylated in disease conditions including atopic disease, acute myeloid leukemia and obesity.44-55

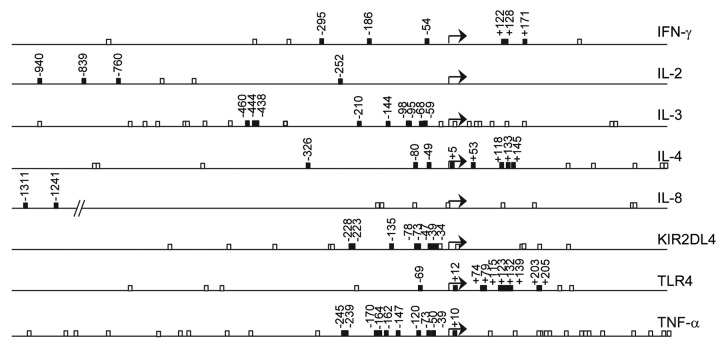

Within these genes, 58 CpG sites located in promoter regions or reported to be differentially methylated under certain conditions were included (Fig. 1). No CpG islands were detected within 1,000 nucleotide bases upstream or 500 bases downstream of the TSS.

Figure 1. Location of CpG sites in the analyzed genes. Numbering of CpGs is based on the TSS (+1), represented by a bent arrow. All CpGs within 1,000 nucleotide bases upstream to 500 bases downstream of the TSS (open boxes) and CpGs included in the methylation study (closed boxes) are shown.

Interindividual variability of DNA methylation in blood cell populations

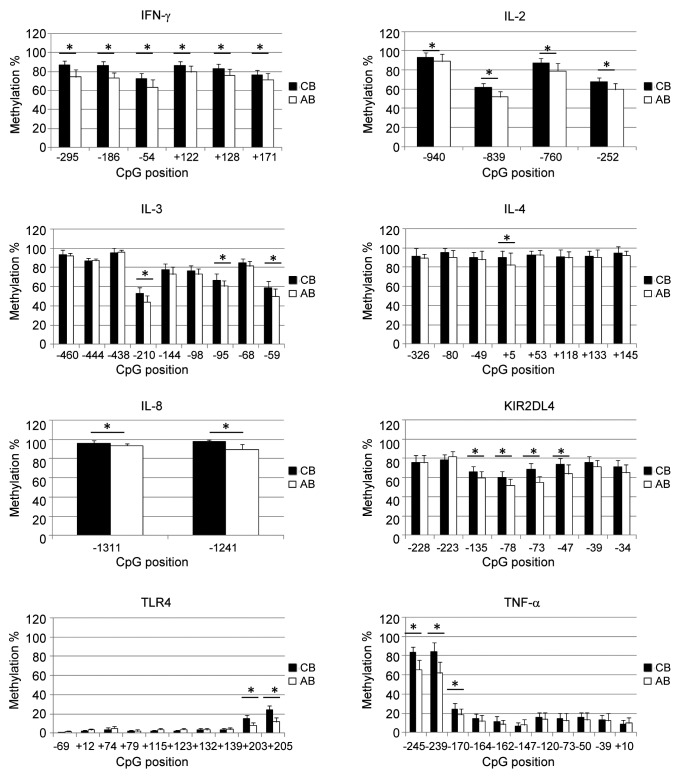

We assessed DNA methylation levels of 58 CpG sites in C/PBMCs of 30 mother-infant pairs. Figure 2 shows that average methylation levels tend to be lower in PBMCs than in CBMCs [25/58 CpG sites (43%)], suggesting a trend for decreased methylation with age. There were no CpGs displaying higher methylation in PBMCs than in CBMCs. Average differences between the highest and the lowest methylation levels across all CpG positions were 19.7 ± 9.7% in CBMCs and 25.5 ± 13.8% in PBMCs. Maximum differences observed within individual CpG positions were 48% in CBMCs (at CpG site TNF-α -239) and 69% in PBMCs (IL4 +5). We defined interindividual variability at each CpG position as the statistical variance over methylation values from all donors. Overall, interindividual variability across individual positions tends to be increased in PBMCs (median variance = 37, IQR = 14–56) in comparison to CBMCs (median variance = 25, IQR = 11–35). Cell-type specific analysis of interindividual variability suggests that the higher variability in PBMCs was not solely related to a more variable blood composition at this age (Fig. 3). Indeed, there was a general trend for higher variability with age in all subpopulations, which supports the concept of postnatal factors influencing methylation variability in these genes. Average interindividual variability across all CpG positions was highest in CD56+ and CD8+ cells, as well as in unsorted CBMCs and PBMCs. CD4+ cells displayed relatively low methylation variability, and CD19+ and CD14+ cell methylation levels were very homogenous (Fig. 3).

Figure 2. Average DNA methylation levels in cord blood and in adult blood. Average methylation levels of about half of the analyzed CpGs were significantly lower in PBMCs than in CBMCs. Stars denote significant differences in average DNA methylation (p < 0.001, Bonferroni-corrected threshold) tested by t-test or Mann-Whitney rank sum test as appropriate. Error bars represent standard deviation (n = 30 donors). Adult blood, open bars; cord blood, closed bars.

Figure 3. Interindividual variability of DNA methylation in blood cell subpopulations. Interindividual variability of DNA methylation levels (expressed as statistical variance) across all CpG sites in different cell types from (A) cord or (B) adult blood donors. Cell types are ordered by decreasing interindividual variability. Boxes display median (horizontal bars), interquartile ranges (lower and upper limits of boxes), 95% interval (whiskers) and outliers (circles). Median values are shown above each box plot. CD19+ and CD14+ cells display a significantly reduced variability in comparison to most other cell types tested by ANOVA on ranks with Tukey’s multiple comparison post-hoc test. Stars denote significant differences (p < 0,05).

For most CpG sites interindividual variability was similar between the different blood cell populations isolated from C/PBMCs (Table S1). TNF-α, KIR2DL4 and IIFN-γ genes represent however a remarkable exception. In TNF-α, 2 particular CpG sites displayed a very high variability in all PBMC subpopulations except for CD14+ cells, which are the main producers of TNF-α (Fig. 4A).56 Similarly, two individuals presented outlier methylation values for 1 CpG site in the KIR2DL4 promoter in all PBMC subpopulations, but not in CD56+ cells, which are the main cells to express KIR2DL4 (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that high interindividual variability of methylation at these sites is not tolerated in CD14+ and CD56+ cells respectively, and may only persist in cell types for which these genes are of minor importance. In IFN-γ, all CpG sites displayed relatively low interindividual variability in most cell types, including CD4+ cells, which are the main producers of IFN-γ.57 However, CB CD56+ cells and AB CD8+ cells, which are also producers of IFN-γ, stand out as having highly variable IFN-γ methylation levels (Fig. 4C; Table S1). In CD56+ cells, the lower variability in AB in comparison to CB may result from methylation changes due to IFN-γ expression in these cells. In contrast, IFN-γ expression in CD8+ cells is not associated with lower variability in AB in comparison to CB.

Figure 4. DNA methylation of TNF-α, KIR2DL4, and IFN-γ promoters in adult blood. (A) In the TNF-α promoter, the high methylation variability of CpGs -245 and -239 (filled circles) in PBMCs is present in all subpopulations (CD4+, CD8+, CD19+ and CD56+ cells) except CD14+ cells, which are the main producers of TNF-α. CD4+ cells are shown as an example of a subpopulation with high methylation variability. (B) In the KIR2DL4 promoter, the outlier methylation values of CpG -228 (filled circles) in PBMCs are present in all subpopulations (CD4+, CD8+, CD14+ and CD19+ cells) except CD56+ cells, which are the main expressers of KIR2DL4. CD4+ cells are shown as an example of a subpopulation with high methylation variability. (C) In the IFN-γ promoter, CD8+ cells present a substantially higher interindividual variability than all other cell types, including CD4+ cells which are the main producers of IFN-γ.

Sorting C/PBMCs into subpopulations is therefore necessary, at least when genes such as TNF-α, KIR2DL4 and IFN-γ are to be analyzed with high resolution and sensitivity. For IFN-γ, further separation of CD4+ cells into naïve, Th1 and Th2 differentiated cells may be appropriate, because of the well described IFN-γ promoter methylation changes during CD4+ cell differentiation.45,58

Parameters that influence interindividual variability of DNA methylation

In order to identify parameters that influence interindividual methylation variability in C/PBMCs and their corresponding subpopulations, we used Spearman’s correlation to obtain an overview over potential bivariate relationships. We tested interindividual variability against average methylation levels, “distance of methylation level to the closest border” (which is “100% - methylation %” or “methylation % - 0%,” whatever is lower), presence of a known transcription binding site (TFBS), phylogenetic conservation of the CpG site, donor age and the different cell types. While there was no significant (p < 0,05) correlation with average methylation levels, there was a highly significant correlation with the “distance of methylation to the closest border.” Indeed, interindividual variability was significantly increased if methylation levels were intermediate (around 50%) rather than low or high (close to 0% or 100%) (Table S2 and Fig. S2). This may be partially expected because of the nature of percentage scales, which restricts both biological and technical variability near interval borders. Other factors that significantly correlated with increased methylation variability included age, CD8+ and CD56+ cell types, while CD14+, CD19+ cell types were negatively correlated with methylation variability. Evolutionary conservation of CpG position, presence of a TFBS and CD34+ cell type were not bivariately correlated with methylation variability. A multiple linear regression model provided however a more subtle interpretation. Analyzing the different variables in one regression model allowed to control for their confounding effects, and to analyze the very specific effects of each parameter on methylation variability. While average methylation levels (distance to the closest border) remained the main factor influencing methylation variability, it appeared that TFBS and interindividual variability were anticorrelated, whereas evolutionary conserved CpG sites were positively correlated with interindividual variability (Table 1). For a given CpG site, presence of TFBS and CpG conservation across species do not change with cell type or age. Thus, distance of average methylation to the closest border is the only variable potentially interacting with presence of a known TFBS and CpG conservation to predict methylation variability, thereby masking the effect of these factors in bivariate correlations. Indeed, both TFBS and CpG conservation turn out to be significant predictors for methylation variability if regression analysis was performed with one of these variables and distance of average methylation to the closest border as the only potential predictors (data not shown). On the other hand, the high methylation variability that was bivariately correlated with CD8+ and CD56+ cell types is not significant when analyzed in a multiple regression model. The high variability associated with these cell types appears to be mostly influenced by other factors, such as average methylation levels or donor age. In order to assess the confounding effect of age on these parameters, we performed the same regression analysis separately for each age group. While CD8+ cells remain uncorrelated with methylation variability in both age groups, CD56+ cells become a significant positive predictor for methylation variability in cord blood.

Table 1. Multiple linear regression analysis to test the association between interindividual variability and potential influencing factors.

| Variables | Beta | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent |

Variance |

||

| Constant |

|

|

0.000 |

| Predictors |

Distance to closest border (methylation %) |

0.488 * |

0.000 |

| |

Presence of a known TFBS |

-0.219 * |

0.000 |

| |

Phylogenetic conservation of CpG |

0.214 * |

0.000 |

| |

Age (adult or newborn) |

0.167 * |

0.000 |

| |

CD4+ cell type |

-0.110 * |

0.005 |

| |

CD14+ cell type |

-0.109 * |

0.006 |

| |

CD19+ cell type |

-0.034 |

0.385 |

| |

CD8+ cell type |

0.030 |

0.441 |

| |

CD34+ cell type |

0.006 |

0.856 |

| CD56+ cell type | 0.005 | 0.891 | |

Ranked by regression coefficient (β), the main factors influencing interindividual variability (variance) are the distance of methylation % to the closest border (0% or 100%), presence of a known TFBS and phylogenetic conservation of CpG site. Stars denote significant correlation coefficients (p < 0.01). Adjusted R2 = 0.340.

It is noteworthy that both Spearman correlation and regression analysis results remain unaffected by removing the 5 outliers having a variance of 563–859 square percentages (Tables S2 and S3).

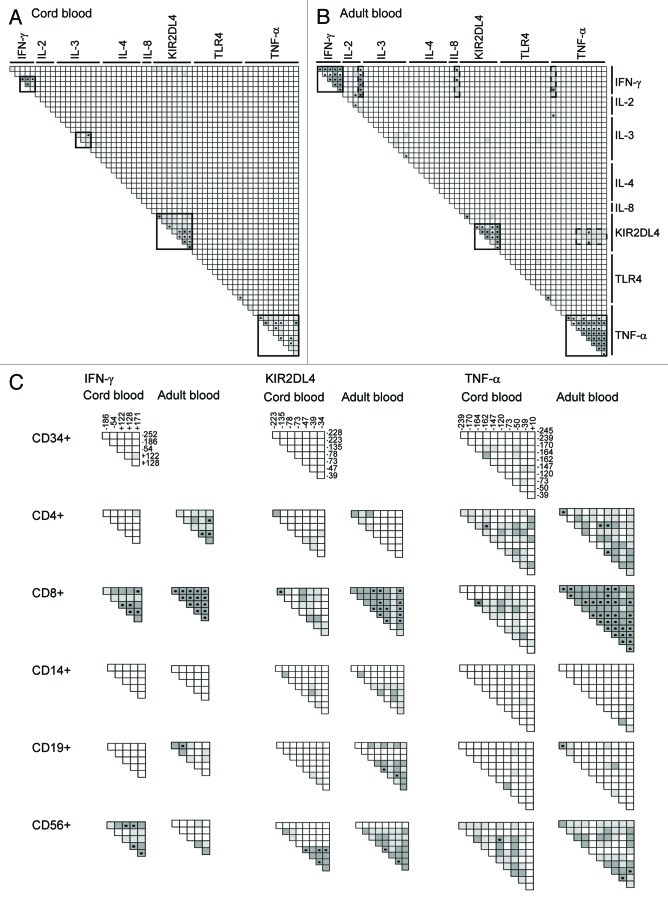

Correlations and patterns of DNA methylation

Methylation of adjacent CpG sites was previously shown to be particularly correlated within genes, but also across different genes.25 Although continuous methylation data were compatible with Pearson’s correlations, we chose to analyze Spearman’s rank order correlations in order to avoid interindividual methylation variability influencing correlation coefficients. Analysis of Spearman’s correlations of methylation levels between all CpGs in CBMCs and PBMCs of the 30 mother-infant pairs revealed clusters of highly correlated CpG methylation levels within IFN-γ, KIR2DL4 and TNF-α promoters (Fig. 5A and B;Tables S4 and S5). Interestingly, both significance and magnitude of the correlations tended to be higher in PBMCs in comparison to CBMCs. Thus, in the IFN-γ promoter, two groups of CpGs with inter-correlated methylation levels can be distinguished in CBMCs [CpGs -252 and -186, rho = 0.67 (p < 0.05); CpGs from -54 to 171, average rho = 0.76, 4 × 10−11 < p < 0.01], whereas methylation levels of all IFN-γ CpGs were highly correlated in PBMCs (average rho = 0.85, 4 × 10−6 < p < 5 × 10−12). Correlations between TNF-α CpG sites from -170 to +10 were also higher in PBMCs (average rho = 0.79, 1 × 10−10 < p < 1 × 10−3) than in CBMCs (average rho = 0.64, 1 × 10−9 < p < 0.06). TLR4 CpGs +203 and +205 [rho = 0.68 (p = 3 × 10−5) in CBMCs and rho = 0.85 (p = 1 × 10−8) in PBMCs] also showed significant correlations between methylation levels. In the KIR2DL4 promoter, correlations between CpGs from -135 to -34 are slightly stronger in PBMCs (average rho = 0.79, 3 × 10−13 < p < 1 × 10−4) than in CBMCs (average rho = 0.74, 4 × 10−11 < p < 0.0002). In CBMCs CpGs -228 and -223 also correlate with this cluster, while this is not the case in PBMCs. Using Fisher’s z transformation, we assessed that 25% of the correlations between CpG sites within the IFN-γ, KIR2DL4 and TNF-α promoters were indeed statistically significantly higher (p < 0.05) in PBMCS than in CBMCs. Correlations between IL-3 CpGs from -210 to -95 were similar in PBMCs and CBMCs [average rho = 0.64 in CBMCs (1 × 10−5 < p < 0.03) and average rho = 0.63 in PBMCs (1 × 10−5 < p < 0.01)]. Therefore, while some CpGs, for instance in the IL-4, seem to be regulated totally independently, adjacent CpGs were often regulated together. This trend to co-regulation tends to be higher in PBMCs than in CBMCs, suggesting that it evolves during an individual’s lifetime, possibly in response to environmental cues or during normal cell differentiation and aging. It is interesting that methylation levels of some CpGs of different genes were also highly correlated in PBMCs, but not in CBMCs. Indeed, methylation levels of the 6 analyzed IFN-γ CpGs significantly correlated with methylation of TNF-α CpG -245 (average rho = 0.77, 3 × 10−9 < p < 3 × 10−5), IL-8 CpG -1241 (average rho = 0.69, 7 × 10−7 < p < 3 × 10−4) and IL-2 CpGs -760 and -252 (average rho = 0.76, 1 × 10−11 < p < 9 × 10−5). There were also significant correlations between KIR2DL4 CpGs -78 to -47 and TNF-α CpGs -147 to +10 (average rho = 0.63, 2 × 10−5 < p < 1 × 10−3). This suggests that methylation levels of distant CpGs may be regulated in concert in response to specific postnatal events. There were no negative correlations (Spearman’s rho < -0.6) in CBMCs, and only between 1 CpG pair in PBMCs.

Figure 5. Correlations between methylation levels of individual CpG sites. Spearman correlations between methylation levels in (A) CB, (B) AB, and (C) IFN-γ, KIR2DL4 and TNF-α promoters in different blood cell populations. Clusters of intercorrelated CpG methylation levels were identified by visual analysis of both magnitude and significance (p value) of the Spearman’s correlation coefficient. Light gray squares: 0.6 < rho < 0.8; dark gray squares: rho ≥ 0.8, Dotted squares correspond to p values < 0.000031 (Bonferroni-corrected threshold). Intragenic clusters of intercorrelated methylation levels are delimited by bold black borders. Intergenic clusters are drawn with dashed borders. See Tables S4 and S5 for a detailed view of rho and p values.

We analyzed the same Spearman’s correlations between methylation levels of all CpGs in the different blood cell subpopulations of 12 CB and 12 AB donors. Although statistical significance (p value below the Bonferroni-corrected threshold of 3 × 10−5) is less often reached than with 30 donors (in the case of C/PBMCs), clusters of CpGs with highly intercorrelated methylation values could again be identified based on significance and high rho values. In both CB and AB, we identified clusters of intercorrelated methylation levels within genes of CD4+ cells (IL-2 and TNF-α), CD8+ cells (IFN-γ, KIR2DL4 and TNF-α), CD14+ cells (IL-3) and in CD56+ cells (IFN-γ, KIR2DL4 and TNF-α). Methylation levels within the IFN-γ promoter were also correlated in adult but not in neonatal CD4+ and CD19+ cells. Similarly, methylation levels within the TLR-4 promoter were correlated in adult, but not neonatal CD8+, CD14+ and CD56+ cells. Notably, methylation levels in CB CD19+ and CD34+ cells were mostly independent within and between genes. Interestingly, methylation of the same CpG sites within IFN-γ, KIR2DL4 and TNF-α genes were highly correlated in some cell types, but totally independent in others (Fig. 5C). Again, correlations within these genes tended to be higher in AB than in CB subpopulations. Clusters of CpG sites with methylation levels correlating between different genes could only be observed in adult CD4+, CD8+ and CD19+ cells and to a lesser extend in neonatal CD8+ and CD56+ cells. In these cell types methylation levels of CpG pairs situated in IFN-γ, IL2, IL4, IL8, KIR2DL4 or TNF-α promoters were shown to vary together.

Collectively, our results show that methylation levels of the same CpG sites may be regulated as a whole cluster of adjacent CpG sites in some cell types, while in other cell types these CpGs vary independently. While neonatal CD19+ and CD34+ cells exhibit methylation levels that are largely independent within and between genes, adult CD8+ cells stand out as having multiple clusters of correlated methylation levels.

Influence of differential blood cell counts on DNA methylation in C/PBMCs

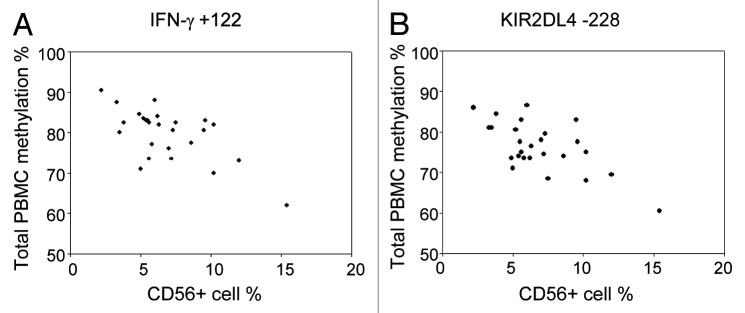

Epidemiological studies conventionally analyze DNA methylation in PBMCs or whole blood. A potential limitation of this approach is that differences in blood cell subpopulations may influence the observed levels of variation. We have phenotyped total C/PBMCs of the 30 mother-infant pairs by flow cytometry for T cell, B cell, monocyte and stem cell markers. While percentages of CD19+ cells (8 ± 3% in CB, 5 ± 2% in AB), CD34+ cells (5 ± 4% in CB) and CD56+ cells (10 ± 5% in CB, 7 ± 3% in AB) were relatively similar between donors, proportions of CD4+ cells (28 ± 8% in CB, 30 ± 8% in AB) and CD14+ cells (21 ± 6% in CB, 19 ± 8% in AB) were more variable. The relative cell counts of CD8+ cells were relatively similar between CB samples (15 ± 4%) but much more variable in AB (19 ± 7%). We have tested whether differences in NK cell frequency bias C/PBMC methylation levels for IFN-γ and KIR2DL4 genes, as these genes present considerably lower methylation values in CD56+ cells compared with all other cell types (Table 2 and Fig. 6). Despite the relatively low variability in CD56+ cell percentages, we were able to correlate methylation of several IFN-γ and KIR2DL4 CpGs in C/PBMCs with the frequency of CD56+ cells. In particular, methylation of all IFN-γ CpG sites was significantly correlated with CD56+ cell frequency in PBMCs (average rho = -0.57, range = -0.41–0.66). For these CpGs, methylation variability in total PBMCs appears to be largely biased by the changes in CD56+ cell population. On the other hand, methylation of most KIR2DL4 CpG sites and most CB IFN-γ CpG sites did not significantly correlate with CD56+ cell frequency and might therefore reflect methylation variability that exceeds changes in blood composition. Furthermore, CB CD34+ cells stand out as having TNF-α methylation levels that differ largely from all other subpopulations. No significant correlations between CD34+ cell frequency and TNF-α methylation were found, which may be due to the overall low frequency of CD34+ cells in CB.

Table 2. Pearson correlation coefficients between DNA methylation in PBMCs and frequency of CD56+ cells.

| |

Cord blood |

Adult blood |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CpG site | Pearson rho | p-value | N | Pearson rho | p value | N |

| IFN-γ -295 |

-0.570 ** |

0.002 |

30 |

-0.414 * |

0.035 |

30 |

| IFN-γ -186 |

-0.325 |

0.106 |

30 |

-0.489 * |

0.011 |

30 |

| IFN-γ -54 |

-0.276 |

0.172 |

30 |

-0.628 *** |

0.001 |

30 |

| IFN-γ +122 |

-0.223 |

0.273 |

30 |

-0.656 ***,† |

0.000 |

30 |

| IFN-γ -128 |

-0.265 |

0.191 |

30 |

-0.580 ** |

0.002 |

30 |

| IFN-γ +171 |

-0.049 |

0.814 |

30 |

-0.600 *** |

0.001 |

30 |

| KIR2DL4 -228 |

-0.423 * |

0.031 |

30 |

-0.656 ***,† |

0.000 |

30 |

| KIR2DL4 -223 |

-0.369 |

0.063 |

30 |

-0.646 *** |

0.000 |

30 |

| KIR2DL4 -135 |

-0.337 |

0.092 |

30 |

-0.144 |

0.484 |

30 |

| KIR2DL4 -78 |

-0.212 |

0.298 |

30 |

0.063 |

0.760 |

30 |

| KIR2DL4 -73 |

-0.303 |

0.133 |

30 |

0.071 |

0.731 |

30 |

| KIR2DL4 -47 |

-0.265 |

0.190 |

30 |

0.300 |

0.136 |

30 |

| KIR2DL4 -39 |

-0.287 |

0.155 |

30 |

-0.345 |

0.084 |

30 |

| KIR2DL4 -34 | -0.381 | 0.055 | 30 | 0.046 | 0.824 | 30 |

p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.0017 (Bonferroni-corrected threshold). †Correlation of methylation of IFN-γ CpG +122 and KIR2DL4 CpG -228 and CD56% in PBMCs is illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6. The influence of CD56+ cell frequency on IFN-γ and KIR2DL4 methylation in PBMCs. Scatterplot showing the correlation between frequency of CD56+ cells and (A) IFN-γ +122 or (B) KIR2DL4 -228 methylation in adult PBMCs.

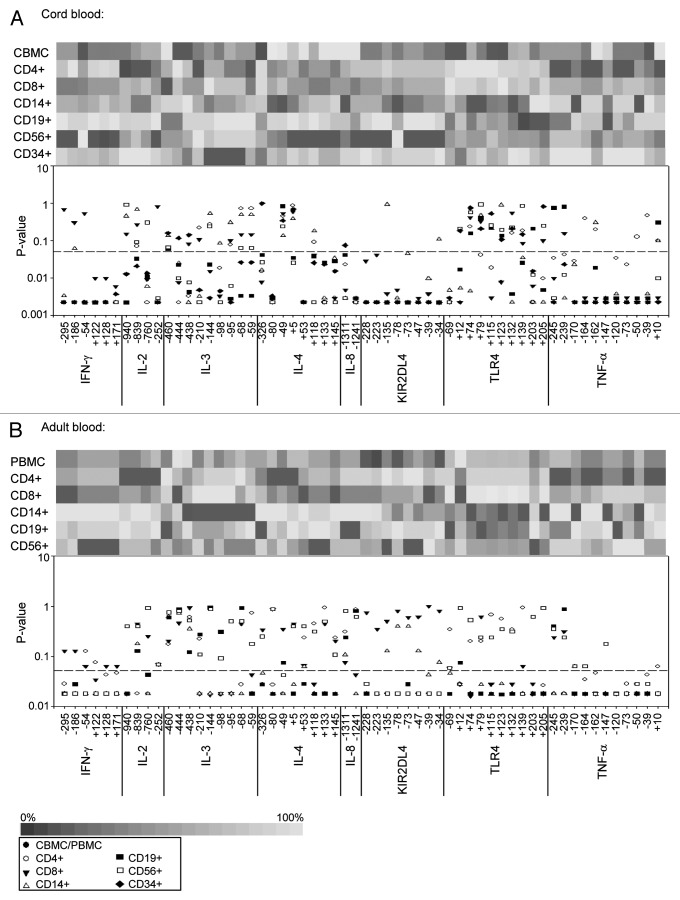

Comparison of methylation in C/PBMCs and subpopulations

In order to evaluate similarity of methylation levels between unsorted C/PBMCs and subpopulations, we compared median methylation levels of each subpopulation to those measured in total C/PBMCs using paired Mann-Whitney tests (Fig. 7). Whenever the null hypothesis of equal median methylation levels between subpopulation and C/PBMCs was not rejected at the 5% significance level (p > 0.05), we considered methylation levels as being similar. Only 2 CpGs in CB (IL-3 -460 and IL-4 -49) and 5 CpGs in AB (IL-2 -252, IL-3 -460, -444, -438 and IL-8 -1311) exhibited similar methylation levels between all subpopulations. In addition, 12 CpG sites (21%) in CB and 11 CpG sites (19%) in AB displayed similar methylation levels between total C/PBMCs and both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Therefore, although T cells make up the majority of C/PBMCs, C/PBMCs methylation levels are not necessarily a direct surrogate for T cell methylation. On the gene level, both CB and AB IL-2 and IL-3, as well as AB IL-4 and IL-8 were the most consistent between C/PBMCs and subpopulations. On the other hand, CB and TNF-α, KIR2DL4 and IFN-γ, as well as CB IL-4 and IL-8 bear methylation levels that were mostly different between C/PBMCs and subpopulations. CpGs IL-4 +53 (p = 0.0022), KIR2DL4 -47 (p = 0.0023) and TNF-α -147 (p = 0.0024) in AB displayed the largest differences from total PBMCs.

Figure 7. Methylation levels in blood cell subpopulations. Upper subplots display heatmaps of average DNA methylation levels in each CpG position and in each cell type in (A) CB and (B) AB. The lower subplots show p values for the comparison of median methylation levels between each subpopulation and total C/PBMCs using paired Mann-Whitney rank sum tests. The dashed line indicates the significance threshold of a p value < 0.05.

C/PBMC methylation levels that differ from subpopulation methylation levels may nevertheless be a valuable surrogate for specific subpopulations, if there is a significant correlation between the two. Indeed, highly correlated methylation levels will lead to a comparable ranking of individuals, regardless whether C/PBMC or subpopulation methylation levels are considered. Therefore, we analyzed Pearson correlations between each subpopulation and total C/PBMCs for each CpG site. In CB, correlations with CBMCs were relatively low for all subpopulations, being highest in the majority cell type of CD4+ cells (median rho = 0.35, IQR = 0.07–0.53), and lowest in the minority cell type of CD34+ cells (median rho = 0.08, IQR = -0.07–0.33) (Fig. 8A). As shown in Figure 8B, at specific CpG sites the same individuals may indeed rank differently depending on the cell type. In contrast, AB CD8+ and CD4+ cells showed strong correlations with total PBMCs for most genes (CD8 median rho = 0.79, IQR = 0.71–0.90; CD4 median rho = 0.62, IQR = -0.43–0.78). In particular, for IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-8, KIR2DL4 and TNF-α, CD8+ and CD4+ cell methylation levels also correlated well within each other (median rho = 0.78, IQR = 0.73–0.89), making PBMC methylation a valuable surrogate for these gene’s methylation in T cells. The high interindividual variability in adult CD8+ cell methylation might be responsible for their increased correlation with PBMC methylation, although they are not the majority cell type. In contrast, CD14+ cells displayed the lowest correlations with PBMCs (median rho = 0.01, IQR = -0.22–0.27).

Figure 8. Correlation of methylation levels between subpopulations and C/PBMCs. (A) Median Pearson correlations between methylation levels of each CpG site in subpopulations and total C/PBMCs. Boxes display median (horizontal bars), interquartile ranges (lower and upper limits of boxes), 95% interval (whiskers) and outliers (circles). C/PBMC methylation levels best correlated with CD4+ and CD8+ cell methylation. (B) Methylation of TLR4 CpG site +205 in CB. Symbols indicate the different individuals. The ranking of the individuals’ methylation levels differs between cell types.

This cell-type specific analysis suggests that although methylation levels detected in total C/PBMCs differ from absolute methylation status in subpopulations, they constitute a valuable surrogate for CD8+ and to a lesser extent for CD4+ cell methylation in AB. In CB however, both correlations and absolute methylation levels between subpopulations and CBMCs differ significantly for almost all CpG sites. Sorting of CBMCs into different cell subpopulations is therefore necessary to obtain reliable methylation data, at least for the genes analyzed in the present study.

Discussion

DNA methylation regulates gene expression in a cell-type specific way. Although PBMCs comprise a heterogeneous cell population, most studies of DNA methylation in blood are performed on unsorted PBMCs. Here, we investigated how interindividual variability, correlations and patterns of DNA methylation compare between various blood cell populations from healthy adults and newborns.

In total C/PBMCs, highest and lowest methylation levels differed by about 20%, which is comparable to the methylation differences in PBMCs or T cells commonly observed in human studies, such as changes in IFN-γ gene methylation in atopic children and in inflammatory bowel disease patients,45,59 or alterations in TNF-α gene methylation in obese responders to dietary intervention.54 However, the observed variation in healthy donors is modest compared with cancer cell lines or animal models where methylation levels ranged from virtually unmethylated to essentially full methylation.50,60 Although we cannot extrapolate our results from eight immune response genes to the whole genome, they are consistent with the variability reported for other genes in whole blood of healthy individuals.23-25 Interestingly, interindividual variability of methylation levels in AB subpopulations were greater than in CB subpopulations, which is compatible with the influence of postnatal factors such as stress, diet,61-63 but also immune-related triggers including infections.64 Indeed, IFN-γ methylation for instance was shown to be altered in HIV-infected CD4+ T cells.65 Furthermore, individual-specific changes in effector, memory and regulatory cell populations are likely to contribute to the higher variability in PBMCs. In C/PBMCs, patterns of DNA methylation look very similar between adult and cord blood donors. About half of the analyzed CpGs displayed however significantly lower methylation levels in PBMCs, which is in line with the observation of lower DNA methylation with age in non-CpG island genes.39

A more compelling finding of our study was that the particularly high interindividual variability observed at 3 CpG positions in TNF-α and KIR2DL4 promoters was present in all cell types except those that mainly express these genes, namely CD14+ and CD56+ cells, respectively. This suggests that methylation of these CpGs is tightly regulated in these cells, and that variability in the other cell types may merely be the result of haphazard processes. One might speculate that methylation of TNF-α CpG sites -245 and -239 prevents binding of a transcriptional repressor, while KIR2DL4 CpG -228 may be located in a TFBS. However, there were no TFBS located at or nearby these CpG sites, as determined by TRANSFAC database search and MATCH algorithm. For TNF-α, the closest TFBS (25 bp downstream of the CpG site -239) was NF-κB, a transcriptional activator of TNF-α. The role of methylation of CpG sites -245 and -239 in TNF-α expression thus is not clear, but seems to be different than normally expected. However, we observe that the other TNF-α CpG sites (from -170 to +10) have low methylation levels in CD14+ cells, which seems to be required for transcription factor binding and gene expression, as shown by Pieper et al.66 TNF-α, TLR4 and KIR2DL4 are typical examples where methylation levels should be investigated in purified or enriched cell populations.

Recent evidence indicates that interindividual variability of DNA methylation is predominantly found in CpG-poor regions, while CpG-rich regions exhibit low and relatively similar methylation levels among individuals.10 Other factors associated with susceptibility to DNA methylation variability have not been described so far. We show here that evolutionary conserved regions are associated with an increased interindividual variability of methylation levels, which may reflect the functional importance of methylation at these sites. Furthermore, variability was reduced when CpG sites were located in TFBS. This is in line with the observation that for some CpG sites interindividual variability is specifically abolished in those cell types that mainly express the gene downstream, and suggests that high interindividual variability may only persist in cell types or at CpG sites that are of minor importance to gene expression. We also find a strong correlation between interindividual variability and average methylation levels, but in contrast to a recent study by Bock et al.10 we find the highest variability when average methylation levels are intermediate rather than high. Bock and colleagues investigated the variability at the amplicon-level and across 3 human chromosomes, which may explain apparent differences in results.

Spearman correlations between methylation levels of individual CpG sites revealed clusters of CpG sites that seem to be regulated as a whole rather than as individual CpGs. This confirms and expands observations of Talens and colleagues, who described correlations between levels of methylation within genes and between mainly imprinted genes.25 Interestingly, the same clusters of correlated CpG sites were found in CB and AB cells. Both magnitude and significance of the correlations were higher in AB, and clusters that were already detectable in CB cells became broader and more prominent in AB. The pattern in the different cell populations suggested that these CpG sites were regulated as clusters in some cell types and independently in others. Postnatal events or natural development may influence methylation levels of those co-regulated CpG sites. In CB, CD34+ methylation levels are largely uncorrelated, indicating that clusters of CpGs with correlating methylation levels may result from both cellular differentiation and environmental exposures.

Our study is unique in that it investigates interindividual methylation variability in the most important subpopulations of C/PBMCs. When all CpGs are considered, CD8+ andCD56+ cells displayed the highest variability in both CB and AB, whereas CD14+ and CD19+ cells exhibited the lowest variations. The higher variability in T cells may be related to their increased average mitotic age, enabling them to accumulate more methylation differences throughout life.67 In addition, with age CD4+ T cells become increasingly memory/effector type cells, which exhibit largely different methylation levels.68 Comparison of absolute methylation levels revealed only few CpG sites having similar methylation in C/PBMCs and all subpopulations. However, about 20% of CpG sites displayed similar methylation in C/PBMCs and both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Although absolute methylation levels in total C/PBMCs are mostly different from those measured in subpopulations, correlations between C/PBMC and subpopulation methylation levels show that PBMC methylation levels may be a valuable surrogate for CD8+, and to a slightly lesser extent for CD4+ T cell methylation. In contrast, CBMC methylation levels are mostly different from and only poorly correlated with subpopulation methylation levels, suggesting that sorting of CBMCs is necessary to obtain unbiased methylation data, at least for the genes analyzed in the present study. Furthermore, methylation levels of several IFN-γ and KIR2DL4 CpGs in total C/PBMCs significantly correlated with the proportion of CD56+ cells, substantiating concerns that differential cell count in the blood influences apparent methylation levels measured in PBMCs. A limitation of our approach is that the correlation results are unreliable for CpG sites with a limited methylation variability (e.g., below the technical variability). This may lead to underestimation of the correlation between DNA methylation in CBMCs and subpopulations.

In conclusion, our methylation studies in purified subpopulations of PBMCs and CBMCs using highly quantitative pyrosequencing showed that although absolute methylation levels differ between subpopulations, PBMC but not CBMC methylation levels represent valuable surrogates for T cell methylation. Methylation patterns in subpopulations suggest a picture in which interindividual variability of promoter methylation of immune response genes is limited in TFBS and may be totally abrogated in the promoter of cells in which the gene is active. While interindividual variability increases from newborn to adult blood, the underlying methylation changes may not be merely stochastic, but seem to be orchestrated as clusters of correlated CpG methylation levels within and between immune response gene promoters.

Materials and Methods

Subject recruitment and sample collection

The study protocol was approved by the Luxembourgish National Research Ethics Committee (CNER) according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All volunteers provided written consent before participation. Exclusion criteria for participants were current or past diagnosis of autoimmune disease or cancer. We recruited 12 healthy adults (6 male and 6 female, age range 18–60 y, mean 33 ± 11 y) for peripheral blood collection (50 ml). Thirty paired maternal-neonatal subjects (maternal age range 20–42 y, mean 33 ± 5 y) were recruited at Dr Bohler Hospital (Luxembourg) by the Clinical and Epidemiological Investigation Center (CIEC, CRP-Santé). We obtained 10–50 ml of cord blood and 10 ml of maternal blood, both collected at the time of delivery. All blood samples were collected into EDTA tubes.

Cell purification and sorting

The mononucleated cell fraction was purified by Ficoll-PaqueTM PLUS (GE Healthcare Cat. No. 17-1440-02) density gradient centrifugation using Leucosep® tubes (Greiner Bio-one, Cat. No. 227289). From the cells collected by density gradient, CD4+ and CD8+ cells were positively selected using 2 rounds of MACS. The purity of MACS-sorted cells was analyzed by flow cytometry using PE-labeled CD4 (clone MEM-241) and PE-labeled CD8 (clone MEM-31) antibodies (Immunotools Cat. No. 21270044 and 21270084). The average purity of MACS-sorted cells was 95% (± 4%) of CD4+ cells and 89% (± 10%) of CD8+ cells. Purity assessments by flow cytometry were based on cell populations excluding dead cells, debris and cell doublets only. Cells in the monocyte gate were essentially CD4 and CD8 negative and were probably co-purified unspecifically. CD14+, CD19+, CD34+ and CD56+ cells were then selected from the T-cell negative fraction using FACS. Briefly, cells were washed with FACS buffer (PBS supplemented with 0.5% BSA and 0.05% NaN3), incubated for 25 min with FITC-labeled CD14 (clone MEM-18, Immunotools Cat. No. 21270143), PE-labeled CD19 (clone LT19, Immunotools Cat. No. 21270194), PE-Cy7-labeled CD34 (clone 581, BD Biosciences Cat. No. 560710) and APC-labeled CD56 (clone MEM-188, Immunotools Cat. No. 21270566) antibodies, washed again in FACS buffer, and passed through a 70 μm cell strainer before analysis and sorting on a FACSAria (BD Biosciences). The average purity of FACS-sorted cells was 97% (± 4%) of CD14+ cells, 98% (± 1%) of CD19+ cells, 94% (± 4%) of CD34+ cells and 95% (± 4%) of CD56+ cells. Cell pellets were stored at -20°C until DNA extraction. The sorting strategy is shown in Figure S1.

DNA extraction and bisulfite treatment

Genomic DNA was extracted using QIAquick kit (Qiagen Cat. No. 28706) following manufacturer’s instructions. Extracted DNA was bisulfite-treated using the EpiTect® Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen Cat. No. 59104) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and stored at -20°C until further use.

Primer design and PCR amplification

PCR primers were designed using MethPrimer software69 or PSQ assay design software (Biotage). PCR Primer sequences are listed in Table S6. For pyrosequencing, first round PCR amplifications were performed with duplicate samples of bisulfite-treated DNA. Then, nested PCR reactions were performed using one unlabeled and one biotin-labeled primer for subsequent purification with streptavidin-sepharose beads. For 454 sequencing, first round PCR amplification was done on single samples of bisulfite-treated DNA. Nested second-round PCR reactions were performed with primers adding M13 universal tails to all amplicons. Then a third round PCR amplification was used to add a sample-specific 10-nucleotide tag (Roche) for computational separation after 454 sequencing.

PCR reaction mixtures consisted of 1x PCR buffer, 1.5–3 mM MgCl2, 0.2mM dNTPs, 0.2–0.8 μM primers, 0.02 U Platinum Taq Polymerase (Invitrogen Cat. No. 10966–026) and 1–10 ng of template DNA. All amplification steps were performed with an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 3 min, 40 cycles of 94°C for 30s, primer-specific annealing temperature for 30s, 72°C for 30s and a final extension step at 72°C for 7 min.

Pyrosequencing

PCR amplicons were purified using streptavidin-sepharose beads (GE Healthcare, Cat. No. 17-5113-01) and the Pyrosequencing Vacuum Prep Tool (Biotage) following the manufacturers recommendations. Pyrosequencing primer (0.4 µM) was then annealed to the purified single-stranded PCR product and pyrosequencing was performed on a PyroMark ID (Biotage). Primers are listed in Table S7. All pyrosequencing reactions were run in duplicates from bisulfite treatment on. The average standard deviation of duplicate values was 2.6 square %.

454 sequencing

Each PCR amplicon was individually prepared, gel-purified and quantified using PicoGreen dsDNA assay kit (Invitrogen, Cat. No. P7589). Samples were run on a 454 sequencer (Roche) by Eurofins MWG Operon or VIB (KU Leuven). Sequencing data were sorted using Geneious v5.3.6 Software (www.geneious.com) and analyzed with QUMA Software.70 Median sequence read coverage per amplicon was 520 (IQR = 181 – 960).

Statistical analysis

Quantitative methylation data were analyzed with SPSS v19.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics). Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to assess bivariate correlations among continuous variables and Spearman correlation coefficient was used to evaluate bivariate relationships between continuous and binary variables. Fisher’s z transformation was performed using R, version 2.15 (package “psych”) in order to determine whether Spearman correlation coefficients were significantly different. Student’s t-test and Mann-Whitney rank sum test were used to assess differences in the mean and median values between two groups. Multiple groups were compared using ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison post-hoc test. In order to analyze correlations with methylation variability, TFBS were extracted from TRANSFAC database version 2012.1. Evolutionary conservation % of CpG sites were calculated based on multiple sequence alignments of homo sapiens, bos taurus, canis familiaris, equus caballus, pan troglodytes, macaca mulatta, Mus musculus and rattus norvegicus sequences. A multiple linear regression model was built to adjust for potential confounders. The TRANSFAC Match algorithm was used to predict potential TFBS in TNF-α and KIR2DL4 promoters.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Clinical and Epidemiological Investigation Center (CIEC, CRP-Santé) for recruitment of participants and the Dr. Bohler Hospital personnel for collaboration and sample collection. We also thank Oliver Hunewald for support with bioinformatics analysis and Sophie Mériaux for technical help. This work was supported by the Centre de Recherche Public de la Santé (CRP-Santé) and the Ministry of Higher Education and Research of Luxembourg.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- AB

adult blood

- CB

cord blood

- CBMC

cord blood mononuclear cell

- CD

cluster of differentiation

- CpG

CG-dinucleotide

- FACS

fluorescence-activated cell sorting, IFN-γ, interferon-γ

- IL

interleukin

- IQR

interquartile range

- KIR2DL4

Killer cell Immunoglobulin-like receptor 2DL4

- MACS

magnetic-activated cell sorting

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- TLR4

toll-like receptor 4

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

- TSS

transcription start site

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest are disclosed.

Supplemental Materials

Supplemental materials may be found here: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/epigenetics/article/22845

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/epigenetics/article/22845

References

- 1.Reik W, Dean W, Walter J. Epigenetic reprogramming in mammalian development. Science. 2001;293:1089–93. doi: 10.1126/science.1063443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonasio R, Tu S, Reinberg D. Molecular signals of epigenetic states. Science. 2010;330:612–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1191078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Y, Zhu J, Tian G, Li N, Li Q, Ye M, et al. The DNA methylome of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ji H, Ehrlich LI, Seita J, Murakami P, Doi A, Lindau P, et al. Comprehensive methylome map of lineage commitment from haematopoietic progenitors. Nature. 2010;467:338–42. doi: 10.1038/nature09367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bocker MT, Hellwig I, Breiling A, Eckstein V, Ho AD, Lyko F. Genome-wide promoter DNA methylation dynamics of human hematopoietic progenitor cells during differentiation and aging. Blood. 2011;117:e182–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-331926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee CG, Sahoo A, Im SH. Epigenetic regulation of cytokine gene expression in T lymphocytes. Yonsei Med J. 2009;50:322–30. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2009.50.3.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergman Y, Fisher A, Cedar H. Epigenetic mechanisms that regulate antigen receptor gene expression. Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15:176–81. doi: 10.1016/S0952-7915(03)00016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ollikainen M, Smith KR, Joo EJ, Ng HK, Andronikos R, Novakovic B, et al. DNA methylation analysis of multiple tissues from newborn twins reveals both genetic and intrauterine components to variation in the human neonatal epigenome. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:4176–88. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coolen MW, Statham AL, Qu W, Campbell MJ, Henders AK, Montgomery GW, et al. Impact of the genome on the epigenome is manifested in DNA methylation patterns of imprinted regions in monozygotic and dizygotic twins. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bock C, Walter J, Paulsen M, Lengauer T. Inter-individual variation of DNA methylation and its implications for large-scale epigenome mapping. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:e55. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boks MP, Derks EM, Weisenberger DJ, Strengman E, Janson E, Sommer IE, et al. The relationship of DNA methylation with age, gender and genotype in twins and healthy controls. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6767. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gertz J, Varley KE, Reddy TE, Bowling KM, Pauli F, Parker SL, et al. Analysis of DNA methylation in a three-generation family reveals widespread genetic influence on epigenetic regulation. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002228. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lange UC, Schneider R. What an epigenome remembers. BioEssays: news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology. 2010;32:659–68. doi: 10.1002/bies.201000030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fraga MF, Ballestar E, Paz MF, Ropero S, Setien F, Ballestar ML, et al. Epigenetic differences arise during the lifetime of monozygotic twins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10604–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500398102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heijmans BT, Tobi EW, Stein AD, Putter H, Blauw GJ, Susser ES, et al. Persistent epigenetic differences associated with prenatal exposure to famine in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17046–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806560105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langevin SM, Houseman EA, Christensen BC, Wiencke JK, Nelson HH, Karagas MR, et al. The influence of aging, environmental exposures and local sequence features on the variation of DNA methylation in blood. Epigenetics. 2011;6:908–19. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.7.16431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilhelm-Benartzi CS, Houseman EA, Maccani MA, Poage GM, Koestler DC, Langevin SM, et al. In utero exposures, infant growth, and DNA methylation of repetitive elements and developmentally related genes in human placenta. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:296–302. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Talens RP, Christensen K, Putter H, Willemsen G, Christiansen L, Kremer D, et al. Epigenetic variation during the adult lifespan: cross-sectional and longitudinal data on monozygotic twin pairs. Aging Cell. 2012;11:694–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00835.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gordon L, Joo JE, Powell JE, Ollikainen M, Novakovic B, Li X, et al. Neonatal DNA methylation profile in human twins is specified by a complex interplay between intrauterine environmental and genetic factors, subject to tissue-specific influence. Genome Res. 2012;22:1395–406. doi: 10.1101/gr.136598.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alisch RS, Barwick BG, Chopra P, Myrick LK, Satten GA, Conneely KN, et al. Age-associated DNA methylation in pediatric populations. Genome Res. 2012;22:623–32. doi: 10.1101/gr.125187.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martino DJ, Tulic MK, Gordon L, Hodder M, Richman TR, Metcalfe J, et al. Evidence for age-related and individual-specific changes in DNA methylation profile of mononuclear cells during early immune development in humans. Epigenetics. 2011;6:1085–94. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.9.16401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandovici I, Kassovska-Bratinova S, Loredo-Osti JC, Leppert M, Suarez A, Stewart R, et al. Interindividual variability and parent of origin DNA methylation differences at specific human Alu elements. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:2135–43. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heijmans BT, Kremer D, Tobi EW, Boomsma DI, Slagboom PE. Heritable rather than age-related environmental and stochastic factors dominate variation in DNA methylation of the human IGF2/H19 locus. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:547–54. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schneider E, Pliushch G, El Hajj N, Galetzka D, Puhl A, Schorsch M, et al. Spatial, temporal and interindividual epigenetic variation of functionally important DNA methylation patterns. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:3880–90. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Talens RP, Boomsma DI, Tobi EW, Kremer D, Jukema JW, Willemsen G, et al. Variation, patterns, and temporal stability of DNA methylation: considerations for epigenetic epidemiology. FASEB J. 2010;24:3135–44. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-150490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eckhardt F, Lewin J, Cortese R, Rakyan VK, Attwood J, Burger M, et al. DNA methylation profiling of human chromosomes 6, 20 and 22. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1378–85. doi: 10.1038/ng1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lister R, Pelizzola M, Dowen RH, Hawkins RD, Hon G, Tonti-Filippini J, et al. Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. Nature. 2009;462:315–22. doi: 10.1038/nature08514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Rohde C, Tierling S, Jurkowski TP, Bock C, Santacruz D, et al. DNA methylation analysis of chromosome 21 gene promoters at single base pair and single allele resolution. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun YV, Turner ST, Smith JA, Hammond PI, Lazarus A, Van De Rostyne JL, et al. Comparison of the DNA methylation profiles of human peripheral blood cells and transformed B-lymphocytes. Hum Genet. 2010;127:651–8. doi: 10.1007/s00439-010-0810-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reinius LE, Acevedo N, Joerink M, Pershagen G, Dahlén SE, Greco D, et al. Differential DNA methylation in purified human blood cells: implications for cell lineage and studies on disease susceptibility. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bjornsson HT, Sigurdsson MI, Fallin MD, Irizarry RA, Aspelund T, Cui H, et al. Intra-individual change over time in DNA methylation with familial clustering. JAMA. 2008;299:2877–83. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.24.2877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Madrigano J, Baccarelli A, Mittleman MA, Sparrow D, Vokonas PS, Tarantini L, et al. Aging and epigenetics: longitudinal changes in gene-specific DNA methylation. Epigenetics. 2012;7:63–70. doi: 10.4161/epi.7.1.18749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fuke C, Shimabukuro M, Petronis A, Sugimoto J, Oda T, Miura K, et al. Age related changes in 5-methylcytosine content in human peripheral leukocytes and placentas: an HPLC-based study. Ann Hum Genet. 2004;68:196–204. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2004.00081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fraga MF, Esteller M. Epigenetics and aging: the targets and the marks. Trends Genet. 2007;23:413–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bollati V, Schwartz J, Wright R, Litonjua A, Tarantini L, Suh H, et al. Decline in genomic DNA methylation through aging in a cohort of elderly subjects. Mech Ageing Dev. 2009;130:234–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heyn H, Li N, Ferreira HJ, Moran S, Pisano DG, Gomez A, et al. Distinct DNA methylomes of newborns and centenarians. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:10522–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120658109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jintaridth P, Mutirangura A. Distinctive patterns of age-dependent hypomethylation in interspersed repetitive sequences. Physiol Genomics. 2010;41:194–200. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00146.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tra J, Kondo T, Lu Q, Kuick R, Hanash S, Richardson B. Infrequent occurrence of age-dependent changes in CpG island methylation as detected by restriction landmark genome scanning. Mech Ageing Dev. 2002;123:1487–503. doi: 10.1016/S0047-6374(02)00080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Christensen BC, Houseman EA, Marsit CJ, Zheng S, Wrensch MR, Wiemels JL, et al. Aging and environmental exposures alter tissue-specific DNA methylation dependent upon CpG island context. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000602. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rakyan VK, Down TA, Maslau S, Andrew T, Yang TP, Beyan H, et al. Human aging-associated DNA hypermethylation occurs preferentially at bivalent chromatin domains. Genome Res. 2010;20:434–9. doi: 10.1101/gr.103101.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ehrlich M. DNA methylation in cancer: too much, but also too little. Oncogene. 2002;21:5400–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strickland FM, Richardson BC. Epigenetics in human autoimmunity. Epigenetics in autoimmunity - DNA methylation in systemic lupus erythematosus and beyond. Autoimmunity. 2008;41:278–86. doi: 10.1080/08916930802024616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsankova N, Renthal W, Kumar A, Nestler EJ. Epigenetic regulation in psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:355–67. doi: 10.1038/nrn2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.White GP, Watt PM, Holt BJ, Holt PG. Differential patterns of methylation of the IFN-gamma promoter at CpG and non-CpG sites underlie differences in IFN-gamma gene expression between human neonatal and adult CD45RO- T cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:2820–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.White GP, Hollams EM, Yerkovich ST, Bosco A, Holt BJ, Bassami MR, et al. CpG methylation patterns in the IFNgamma promoter in naive T cells: variations during Th1 and Th2 differentiation and between atopics and non-atopics. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2006;17:557–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2006.00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murayama A, Sakura K, Nakama M, Yasuzawa-Tanaka K, Fujita E, Tateishi Y, et al. A specific CpG site demethylation in the human interleukin 2 gene promoter is an epigenetic memory. EMBO J. 2006;25:1081–92. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu S, Shen T, Huynh L, Klisovic MI, Rush LJ, Ford JL, et al. Interplay of RUNX1/MTG8 and DNA methyltransferase 1 in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1277–84. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Santangelo S, Cousins DJ, Winkelmann NE, Staynov DZ. DNA methylation changes at human Th2 cytokine genes coincide with DNase I hypersensitive site formation during CD4(+) T cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2002;169:1893–903. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.4.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kwon NH, Kim JS, Lee JY, Oh MJ, Choi DC. DNA methylation and the expression of IL-4 and IFN-gamma promoter genes in patients with bronchial asthma. J Clin Immunol. 2008;28:139–46. doi: 10.1007/s10875-007-9148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.De Larco JE, Wuertz BR, Yee D, Rickert BL, Furcht LT. Atypical methylation of the interleukin-8 gene correlates strongly with the metastatic potential of breast carcinoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13988–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2335921100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li G, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. Epigenetic mechanisms of age-dependent KIR2DL4 expression in T cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:824–34. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0807583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takahashi K, Sugi Y, Hosono A, Kaminogawa S. Epigenetic regulation of TLR4 gene expression in intestinal epithelial cells for the maintenance of intestinal homeostasis. J Immunol. 2009;183:6522–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sullivan KE, Reddy AB, Dietzmann K, Suriano AR, Kocieda VP, Stewart M, et al. Epigenetic regulation of tumor necrosis factor alpha. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:5147–60. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02429-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Campión J, Milagro FI, Goyenechea E, Martínez JA. TNF-alpha promoter methylation as a predictive biomarker for weight-loss response. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:1293–7. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cordero P, Campion J, Milagro FI, Goyenechea E, Steemburgo T, Javierre BM, et al. Leptin and TNF-alpha promoter methylation levels measured by MSP could predict the response to a low-calorie diet. J Physiol Biochem. 2011;67:463–70. doi: 10.1007/s13105-011-0084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schippers EF, van ’t Veer C, van Voorden S, Martina CA, le Cessie S, van Dissel JT. TNF-alpha promoter, Nod2 and toll-like receptor-4 polymorphisms and the in vivo and ex vivo response to endotoxin. Cytokine. 2004;26:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sellge G, Magalhaes JG, Konradt C, Fritz JH, Salgado-Pabon W, Eberl G, et al. Th17 cells are the dominant T cell subtype primed by Shigella flexneri mediating protective immunity. J Immunol. 2010;184:2076–85. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Janson PC, Marits P, Thörn M, Ohlsson R, Winqvist O. CpG methylation of the IFNG gene as a mechanism to induce immunosuppression [correction of immunosupression] in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2008;181:2878–86. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gonsky R, Deem RL, Landers CJ, Derkowski CA, Berel D, McGovern DP, et al. Distinct IFNG methylation in a subset of ulcerative colitis patients based on reactivity to microbial antigens. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:171–8. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weaver IC, Cervoni N, Champagne FA, D’Alessio AC, Sharma S, Seckl JR, et al. Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:847–54. doi: 10.1038/nn1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Waterland RA, Lin JR, Smith CA, Jirtle RL. Post-weaning diet affects genomic imprinting at the insulin-like growth factor 2 (Igf2) locus. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:705–16. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kotsopoulos J, Sohn KJ, Kim YI. Postweaning dietary folate deficiency provided through childhood to puberty permanently increases genomic DNA methylation in adult rat liver. J Nutr. 2008;138:703–9. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.4.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smith AK, Conneely KN, Kilaru V, Mercer KB, Weiss TE, Bradley B, et al. Differential immune system DNA methylation and cytokine regulation in post-traumatic stress disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2011;156B:700–8. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Paschos K, Allday MJ. Epigenetic reprogramming of host genes in viral and microbial pathogenesis. Trends Microbiol. 2010;18:439–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mikovits JA, Young HA, Vertino P, Issa JP, Pitha PM, Turcoski-Corrales S, et al. Infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 upregulates DNA methyltransferase, resulting in de novo methylation of the gamma interferon (IFN-gamma) promoter and subsequent downregulation of IFN-gamma production. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5166–77. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pieper HC, Evert BO, Kaut O, Riederer PF, Waha A, Wüllner U. Different methylation of the TNF-alpha promoter in cortex and substantia nigra: Implications for selective neuronal vulnerability. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;32:521–7. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chu M, Siegmund KD, Hao QL, Crooks GM, Tavaré S, Shibata D. Inferring relative numbers of human leucocyte genome replications. Br J Haematol. 2008;141:862–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li Y, Chen G, Ma L, Ohms SJ, Sun C, Shannon MF, et al. Plasticity of DNA methylation in mouse T cell activation and differentiation. BMC Mol Biol. 2012;13:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-13-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li LC, Dahiya R. MethPrimer: designing primers for methylation PCRs. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:1427–31. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.11.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kumaki Y, Oda M, Okano M. QUMA: quantification tool for methylation analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(Web Server issue):W170-5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.