Abstract

Claudin (Cld)-4 is one of the dominant Clds expressed in the kidney and urinary tract, including selective segments of renal nephrons and the entire urothelium from the pelvis to the bladder. We generated Cldn4 −/− mice and found that these mice had increased mortality due to hydronephrosis of relatively late onset. While the renal nephrons of Cldn4 −/− mice showed a concomitant diminution of Cld8 expression at tight junction (TJ), accumulation of Cld3 at TJ was markedly enhanced in compensation and the overall TJ structure was unaffected. Nonetheless, Cldn4 −/− mice showed slightly yet significantly increased fractional excretion of Ca2+ and Cl−, suggesting a role of Cld4 in the specific reabsorption of these ions via a paracellular route. Although the urine volume tended to be increased concordantly, Cldn4 −/− mice were capable of concentrating urine normally on dehydration, with no evidence of diabetes insipidus. In the urothelium, the formation of TJs and uroplaques as well as the gross barrier function were also unaffected. However, intravenous pyelography analysis indicated retarded urine flow prior to hydronephrosis. Histological examination revealed diffuse hyperplasia and a thickening of pelvic and ureteral urothelial layers with markedly increased BrdU uptake in vivo. These results suggest that progressive hydronephrosis in Cldn4 −/− mice arises from urinary tract obstruction due to urothelial hyperplasia, and that Cld4 plays an important role in maintaining the homeostatic integrity of normal urothelium.

Introduction

Claudins (Clds), integral membrane proteins with 4 transmembrane domains, are crucial components of tight junctions (TJs), which act as a primary barrier to solutes and water between the apical and basal sides of epithelial cellular sheets [1], [2]. The claudin gene family consists of at least 24 members in mice and humans [2], [3]. Typically, multiple Clds are expressed in most types of epithelial cells, and the combination and ratio of different types of Clds in TJ strands may determine the permeability of each epithelial cellular sheet [3], [4]. The physiological importance of the barrier function of Cld-based TJs in vivo has been elucidated with the use of mice targeted for various Cld genes (Cldns), such as Cldn1 in epidermis [5], Cldn5 in blood–brain barrier [6], Cldn11 in myelin and Sertoli cells [7], Cldn14 in inner ears [8], [9], and Cldn18 in stomach [10]. In addition, accumulating evidence reveals that Clds may function beyond being a simple barrier. In renal nephrons, for instance, Clds may regulate the reabsorption of selected cations or anions via a paracellular route between the tubular epithelial cells [11], [12], [13]. Among the Cld family members, Cld4 has been shown to act as selective paracellular channels for Cl– [14] and barriers against cations [15] as well as to play a role with MUPP1 in the maintenance of a tight epithelium under hypertonic stress [16], [17] at least in vitro. Clds may also be directly or indirectly involved in the regulation of cell proliferation. It was demonstrated that Cldn15 −/− mice developed mega-intestine due to the diffuse, nonneoplastic increase of upper intestinal epithelial cells [18]. Deregulated expression of Clds has been reported in many types of human tumors and may play a role in tumorigenesis as well [19]. For instance, Cld2 expressed in certain colon cancer cells played a significant role in their epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-mediated cell proliferation, inasmuch as the knockdown of endogenous Cldn2 compromised proliferation in vitro and tumorigenesis in vivo [20], [21]. More recently, we reported that Cld4 expressed on normal thymocytes was capable of enhancing T-cell receptor (TCR)-mediated ERK activation and proliferation in the fetal thymus organ culture [22].

Uroepithelium (urothelium) is a unique stratified epithelium that lines the urinary tract, including the renal pelvis, ureters, and bladder, and forms a highly distensible barrier that prevents unregulated substance exchanges between the urine and the blood supply. This process mainly involves uniquely differentiated umbrella cells [23]. While the urothelial cells show slow turnover rates (∼3–6 mo) at a steady state, they have enormous regenerative capacity and are rapidly restored following damage [23]. Urothelial plaques (uroplaques [UPs]) consisting of uroplakin particles play an important role in the barrier function of urothelium [24]. The urothelial cells express many types of Clds, including Cld4, throughout the layers in both humans and mice [23]; however, their exact function in the urothelium remains elusive. In current study, we demonstrate that Cldn4 −/− mice develop progressive hydronephrosis as they age, resulting in increased mortality. Prior to the development of overt hydronephrosis, Cldn4 −/− mice showed diffuse hyperplasia and thickening of the urothelium leading to urinary tract obstruction as revealed by intravenous pyelography (IVP), while the structure of TJs and the gross barrier effect were largely retained. Our results indicate that Clds play an important physiological role in maintaining the homeostatic integrity of the urothelium.

Results

Development of Hydronephrosis in Cldn4−/− Mice

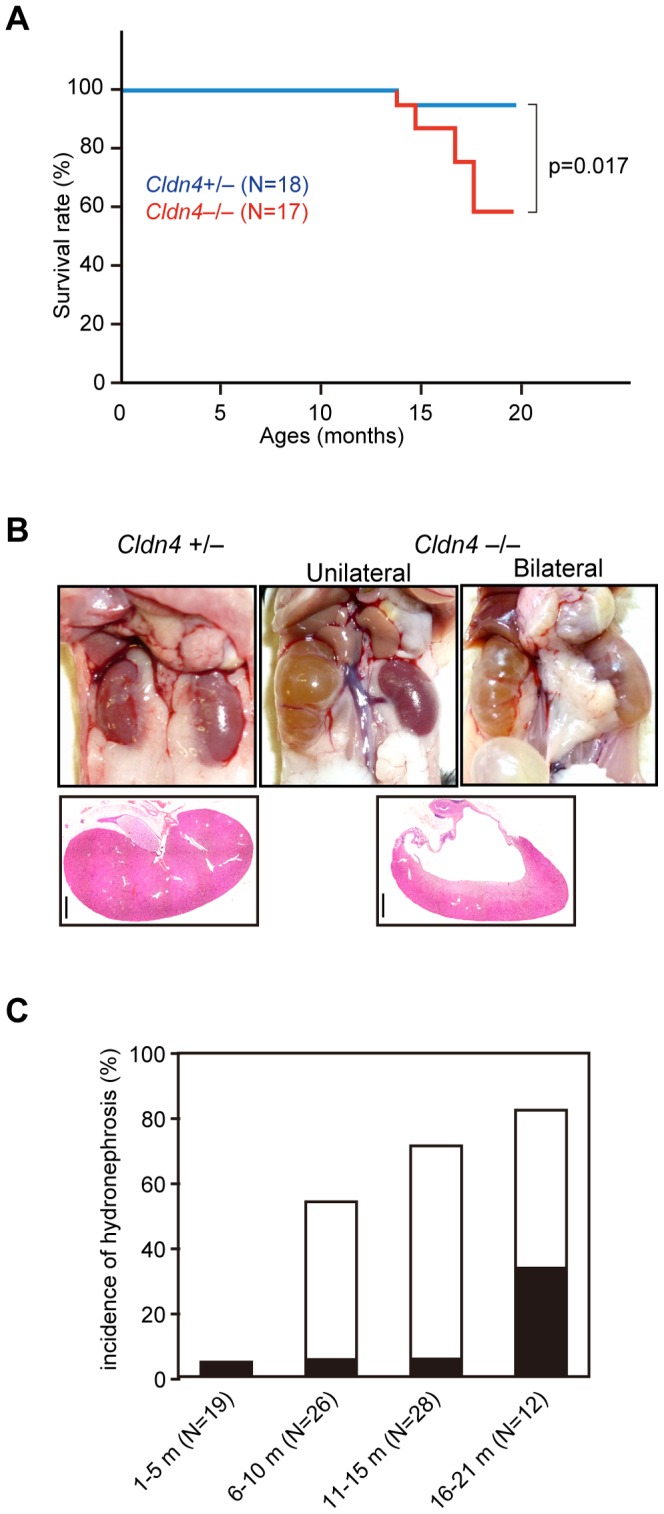

We generated loxP-floxed Cldn4 targeted mice and mated them with CAG-Cre mice to develop germ-line transmittable Cldn4-deleted (Cldn4 −/−) mice (Figure S1). The Cldn4 −/− mice were backcrossed with C57BL/6 (B6) mice for more than six generations. They were born in the expected Mendelian ratio and developed apparently normally. However, after the first year of age, Cldn4 −/−mice showed significantly increased mortality; the survival rate of Cldn4 −/− mice at 20 months of age was 59% (10/17), whereas that of Cldn4 +/− littermates was 94% (17/18) (Figure 1A). Cldn4 −/− mice over 1 year of age frequently showed striking hydronephrosis with markedly dilated pelvis and severely compressed renal parenchyma (Figure 1B). Random sampling autopsy indicated that the macroscopic hydronephrosis was already evident in 54% of Cldn4 −/− mice before 10 months of age and in 83% after 16 months (Fig. 1 C). While most of the hydronephrosis was observed unilaterally before 15 months, the proportion of bilateral hydronephrosis was markedly increased after 16 months Cldn4 −/− mice, leading to increased mortality (Figure 1C). None of the Cldn4 +/− littermates developed hydronephrosis until 21 months of age. Unaffected kidneys of Cldn4 −/− mice were grossly normal without any signs of developmental anomaly upon histological examination, as were other organs.

Figure 1. Development of hydronephrosis in Cldn4 −/− mice.

(A) Kaplan-Meier’s survival curves of Cldn4+/− (N = 18) and Cldn4−/− (N = 17) mice. (B) Macroscopic and microscopic appearances of kidneys in Cldn4+/− and Cldn4−/− mice. Two representative cases of unilateral and bilateral hydronephrosis in Cldn4−/− mice (8 months old) are shown. Bars; 1 mm. (C) Incidence of hydronephrosis at various ages of Cldn4−/− mice. Indicated numbers of Cldn4−/− mice were sacrificed at various ages, and the incidence of macroscopic hydronephrosis was examined. Open columns, unilateral hydronephrosis; closed columns, bilateral hydronephrosis. None of the Cldn4 +/− mice developed hydronephrosis.

Compensatory Cld Expression and Preserved TJs and Barrier Function in Cldn4−/− Mice

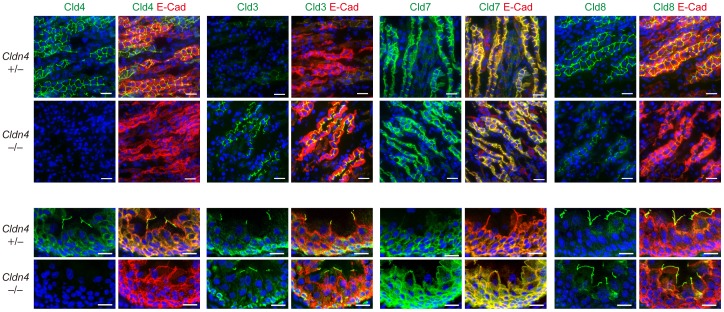

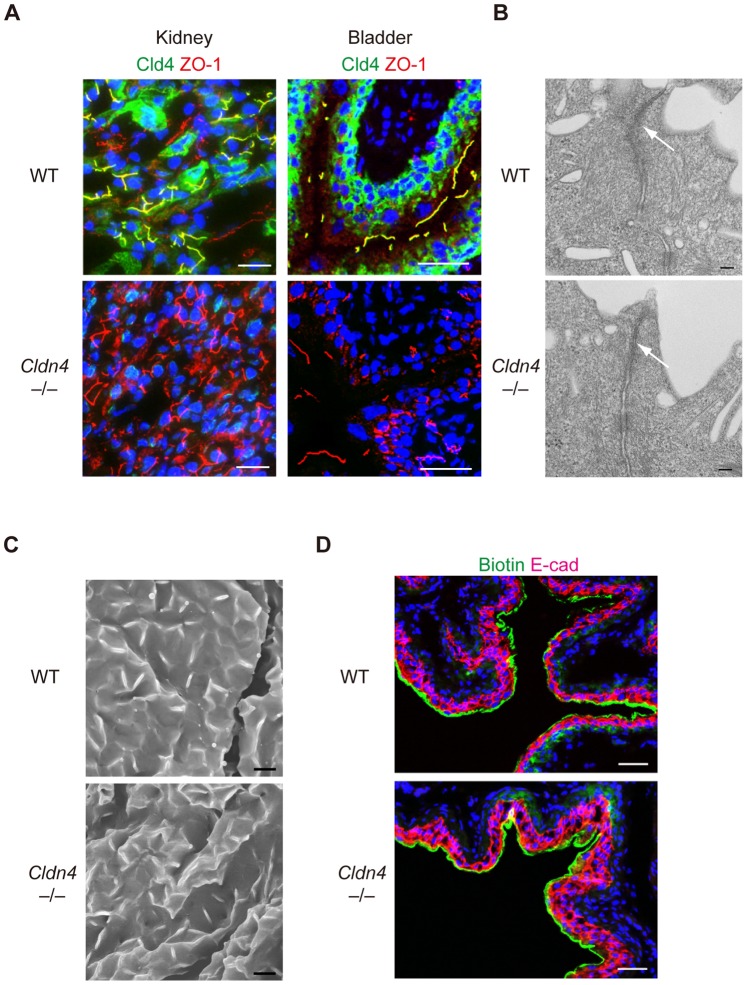

In the renal nephrons, Cld4 expression was detected selectively in the medullary AQP1+ cells corresponding to the thin descending loop of Henle [25], CIC-K+ thin ascending loop of Henle [26], TRPV5+ late distal convoluted tubule and connecting tubule [27], and AQP2+ collecting duct [28], sparing the cortical AQP1+ proximal tubules [25] and THP+ thick ascending loop of Henle [29] (Figure S2). Interestingly, although no Cld4 expression was detected in nephrons of Cldn4−/− mice as expected by immunostaining analysis, the collecting duct cells showed markedly enhanced signals of Cld3 and reduced Cld8 at TJs compared with those of Cldn4 +/−mice (Figure 2 upper). It was noted that Cld3 was apparently concentrated at TJs of collecting duct epithelial cells corresponding to Cld4 in Cldn4 +/− mice (Figure 2 upper). Immunoblotting and quantitative RT-PCR analysis, however, revealed that the expression of Cld3 and Cld8 was unchanged at both protein and transcripts levels in kidneys (Figure S3A, B), strongly suggesting that the accumulation of Cld3 at TJs and reduced Cld8 signals of Cldn4−/− renal tubular epithelial cells was attributable to the molecular redistribution. In agreement with compensational localization of Cld3 at TJs in Cldn4−/−medullary nephrons, these tubular epithelial cells showed a characteristic expression profile of ZO-1 associated with TJs indistinguishable from WT cells (Figure 3A), suggesting that the TJ formation per se was hardly affected. In the normal urothelium, Cld4 was concentrated at TJs of the most apical umbrella cells and as well as being diffusely distributed throughout plasma membranes of underlying cell layers (Figure 2 lower). On the other hand, Cld8 expression was highly restricted at the TJs of umbrella cells, whereas Cld7 was detected mostly in the cells from intermediate to basal layers along the entire plasma membrane (Figure 2 lower). The urothelium of Cldn4−/− mice showed markedly enhanced signals of Cld7 at the TJs of umbrella cells, although the expression patterns of Cld3 and Cld8 were unchanged (Figure 2 lower). Again, expression of Cld7 as well as other Clds expressed in urothelium [30] were not altered at the total protein level (Figure S4). Accordingly, the TJ formation was unaffected in the Cldn4−/− urothelium as judged by both the ZO-1 expression profile and ultrastructural analysis (Figure 3A, B); UP formation on the surface of the bladder was also normal (Figure 3C). Furthermore, the bladders of Cldn4−/− mice showed a barrier effect for small molecular weight tracers comparable to that of WT littermates (Figure 3D). Altogether, these results suggest that the formation of TJs and the barrier function are largely conserved in the nephrons and urothelium of Cldn4−/− mice, most likely due to the compensatory relocalization of other specific Cld members at TJs.

Figure 2. Compensatory accumulation of other Clds at TJs in the nephrons and urothelium of Cldn4 −/− mice.

Renal medullary regions (upper) and ureters (lower) of Cldn4+/− mice and Cldn4−/− mice (2 months old) with no evidence of hydronephrosis were three-color immunostained with anti-Cld4, anti-Cld3, anti-Cld7, or anti-Cld8 (green), along with anti-E-cadherin (E-cad) (red) and DAPI (blue). Bars, 50 µm (upper) and 20 µm (lower). Note the increased signal of Cld3 with diminished Cld8 signal at the cell-cell adhesion sites in renal medullary regions and increased Cld7 signal in ureter of Cldn4−/− mice.

Figure 3. Preserved TJs and barrier function of TJs of Cldn4 −/− mice.

(A) Kidneys and bladders of WT and Cldn4−/− mice were immunostained with anti-Cld4 (green), anti-ZO-1 (red), and DAPI (blue). Bars, 50 µm. (B) Urothelium of ureters of WT and Cldn4−/− mice were subjected to ultrathin transmission electron microscopy. Bars, 100 nm. Arrows indicate TJs. (C) Urothelium of bladders of WT and Cldn4−/− mice were subjected to scanning electron microscopy. Bars, 5 µm. (D) WT and Cldn4−/− mice under anesthesia were injected with sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin into bladders, and 20 minutes later the bladders were dissected and 3-color immunostained with streptavidin (green) and E-cadherin (E-cad)(red) and DAPI (blue). Bars, 50 µm.

Impaired Renal Reabsorption of Selective Ions in Cldn4−/− Mice

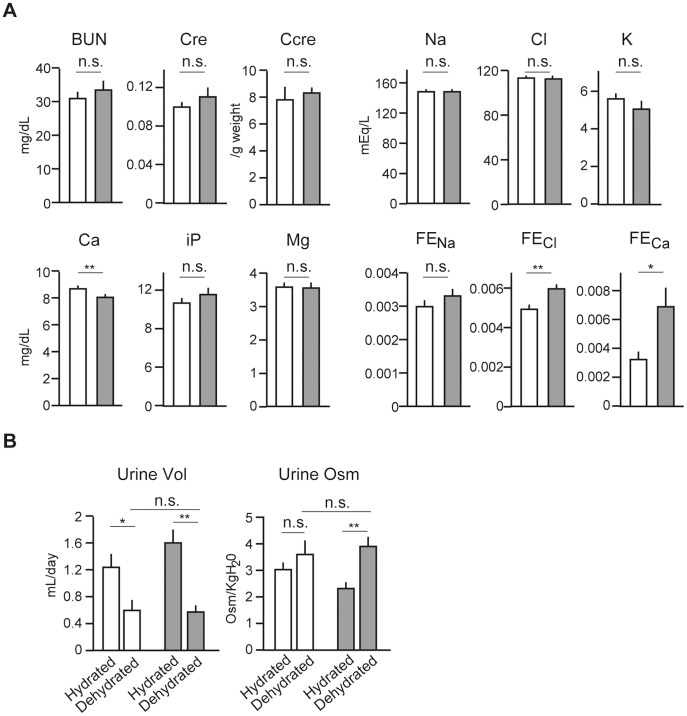

Prior to overt hydronephrosis, 3-month-old Cldn4−/− mice showed serum blood urea nitrogen and creatinine within normal ranges (Figure 4A). Also, the concentration of serum ions, including Na+, K+, Cl−, iP, and Mg2+, was unaffected except for a mild, yet significant decrease of Ca2+ (Figure 4A). The decrease of serum Ca2+ was paralleled by an increased Ca2+ fractional excretion (FECa), suggesting impaired reabsorption. FECl was also increased significantly, although plasma Cl− concentration was unchanged (Figure 4A). In concordance with increases of FECa and FECl, Cldn4−/− mice with free access to water and food tended to show increased daily urine volume (p = 0.172) with reduced osmolality (p = 0.017)(Figure 4B). However, 24-hour dehydration caused a sharp decrease of urine volume with increased osmolality in Cldn4−/− mice to the extent comparable with WT littermates (Figure 4B). Thus, although the basal activity of urine concentration tended to be reduced reflecting the mild impairment of Ca2+ and Cl− reabsorption, Cldn4−/− mice showed no evidence of diabetes insipidus.

Figure 4. Impaired reabsorption of Ca2+ and Cl− in Cldn4−/− mice.

(A) Indicated ion concentrations in the urine and serum of WT (open columns) and Cldn4−/− (gray columns) mice (3 months old) with no evidence of hydronephrosis were analyzed, and the serum ion concentrations, creatinine (Cre), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine clearance (Ccre), and ion fractional excretions (FE) were determined. The means and SE of five mice are indicated. n.s., not significant; *p<0.05; **p<0.01. (B) Total 24-hour urine volume and osmolality of WT (open columns) and Cldn4−/− (gray columns) mice before and after the water depletion for 24 hours were determined. The means and SE of five mice. n.s., not significant; *p<0.05; **p<0.01.

Diffuse Urothelial Hyperplasia Underlies Hydronephrosis in Cldn4−/− Mice

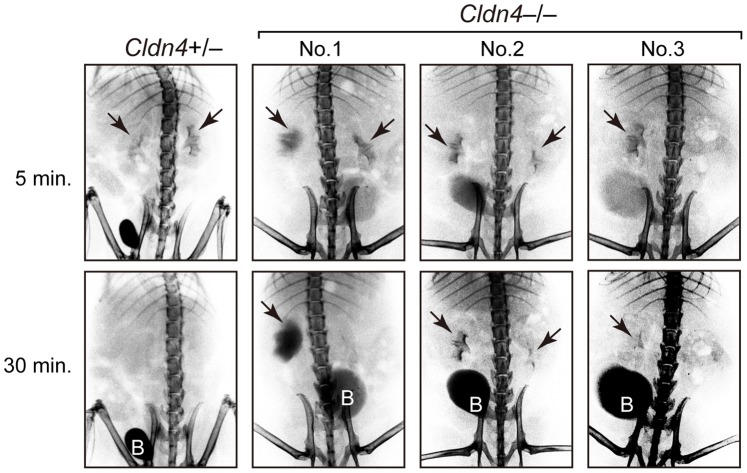

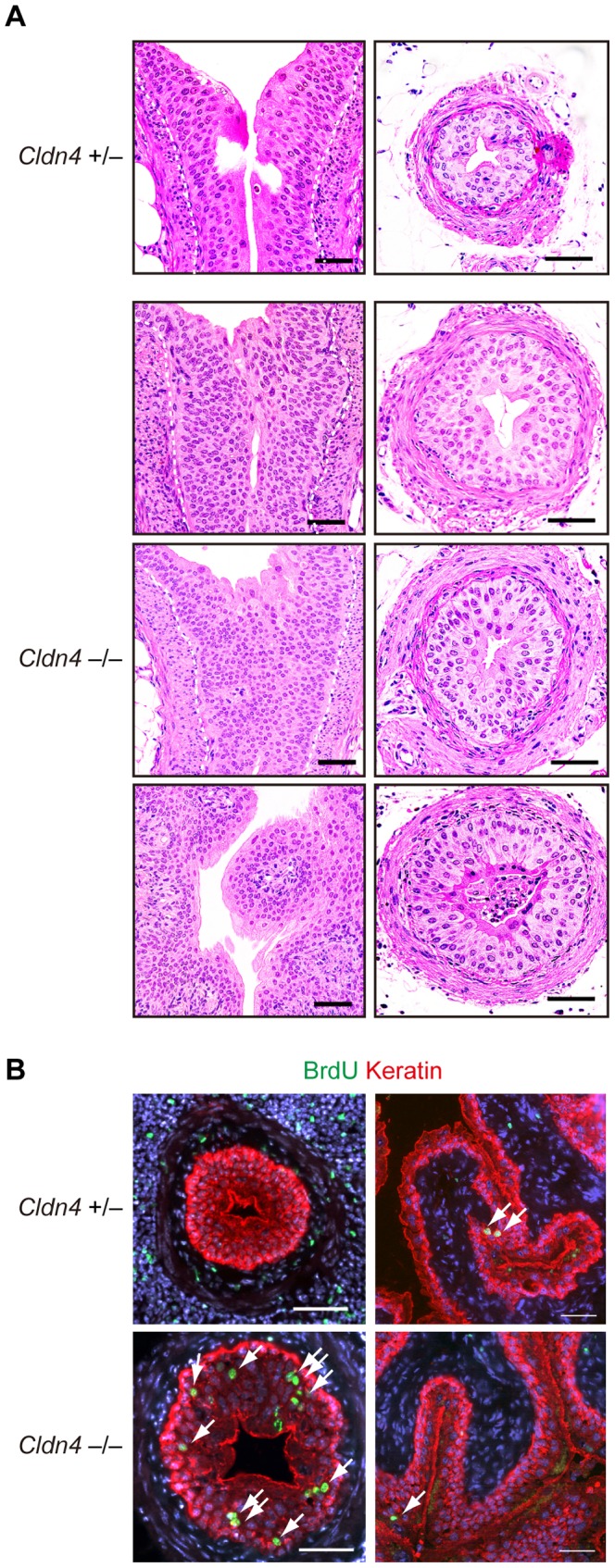

We then investigated the possibility of postrenal causes for the development of hydronephrosis. IVP analysis revealed that the majority of Cldn4 −/− mice at 5–8 months of age exhibited delayed excretion of Omnipaque compared with Cldn4 +/− mice at variable levels, including a marked retention at unilateral pelvis (Figure 5, No. 1), delayed clearance at both sides (Figure 5, No. 2), and complete failure of unilateral pelvic depiction (Figure 5, No. 3). The results suggested urinary tract obstruction in Cldn4 −/− mice prior to hydronephrosis and prompted us to carefully examine the histology of the urothelium. It was found that the urothelial layers of the renal pelvic region and ureters were thickened diffusely with markedly increased cellularity and layers in Cldn4 −/− mice prior to the development of hydronephrosis (Figure 6A). Although papillomatous protrusions were observed occasionally in the pelvis, no overt tumor formation was encountered (Figure 6A). There was no evidence of inflammatory reactions either, such as inflammatory cell infiltration and fibrosis. To directly investigate the proliferation rates of urothelial cells in situ, we examined BrdU uptake in the urothelium after BrdU injection for 4 consecutive days. Although BrdU staining was rarely observed in the urothelial cells in Cldn4 +/− mice, both the pelvic and ureteral urothelial cells of Cldn4 −/− mice with no overt hydronephrosis showed significant incorporation of BrdU (Figure 6B). The bladder urothelial cells of the same Cldn4 −/− mice, however, showed no evidence of hyperplasia and rarely incorporated BrdU similar to Cldn4 +/− mice (Figure 6B). The results suggest that the pelvic and ureteral urothelial cells in Cldn4 −/− mice show increased proliferation as they age, leading to the urothelial hyperplasia and progression of upper urinary tract obstruction.

Figure 5. Urinary tract obstruction in Cldn4−/− mice.

Intravenous pyelography (IVP) was performed at 5 and 30 minutes after the injection of Omnipaque in Cldn4+/− and Cldn4−/− mice (7–8 months old). Typical examples of Cldn4−/− mice are indicated: No. 1, 8 months old; No. 2, 7 months old; and No 3., 7 months old. Arrows indicate the depicted pelvises and “B” indicates bladders.

Figure 6. Urothelial hyperplasia with increased BrdU incorporation in Cldn4 −/− mice.

(A) Sections of the uretero-pelvic junction regions (left panels) and lower part of the ureters (right panels) of Cldn4 +/− and Cldn4 −/− littermate mice (8–19 month old) with no evidence of hydronephrosis were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Dotted lines indicate the urothelial basal layers. Note the increased urothelial cell numbers and layers. Bars, 50 µm. (B) Cldn4 +/− and Cldn4 −/− littermate mice (12 months old) were injected with BrdU (1 mg/animal) intraperitoneally for 4 consecutive days, and the sections of the ureters (left) and bladders (right) were three-color immunostained with anti-BrdU (green, arrows), anti-keratin (red), and DAPI (blue). Bars, 50 µm.

Discussion

Nephropathy due to progressive hydronephrosis can be caused by various renal as well as postrenal causes, and a number of genetically engineered mouse models have been described. ClC-K1 and AQP-2, which mediate the transepithelial transport of chloride and water, respectively, in the renal nephrons, play a crucial role in urine concentration, and the ablation of Clck1 or Aqp2 or mutation of Aqp2 results in the rapid development of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus followed by hydronephrosis [31], [32], [33], [34]. On the other hand, ablation of uroplakin genes (UPII, UPIIIa) responsible for the formation of UPs covering the surface of the umbrella cells of the urinary tract causes increased urothelial leakiness and hyperplasia, leading to obstructive hydronephrosis [35], [36]. In the current study, we developed Cldn4 −/− mice and found that Cldn4 deficiency also resulted in the development of hydronephrosis. The hydronephrosis developed unilaterally with no overt clinical signs, but the disease progressed bilaterally in a significant proportion of Cldn4 −/− mice with age, causing increased mortality.

A recent report indicates that Cld4 is physically associated with Cld8 at TJs in a cultured collecting duct cell line [14]. In Cldn4 −/− mice, Cld8 expression at TJs was greatly reduced specifically in collecting duct epithelial cells, in agreement with the coordinated expression of Cld4 and Cld8 in the normal nephron in vivo. In any case, the TJ structures were apparently preserved in both collecting duct and urpthelium of Cldn4 −/− mice, as judged by the unaffected localization of TJ-associated ZO-1. We found that the Cldn4 −/− tubular epithelial cells and urothelium showed markedly enhanced expression of Cld3 and Cld7 at TJs, respectively, which were detected diffusely and only marginally in Cldn4 +/− mice. Such a compensatory or back-up localization of other Cld members at TJs has not been reported in other Cld-deficient mice. The overall protein levels of Cld3, Cld7 and Cld8 were unchanged in the kidneys and urothelium of Cldn4 −/− compared with Cldn4 +/− mice, and thus it was strongly suggested that the effects were due to the altered localization of other preexisting claudin members rather than induction or repression of the expression. Claudins are not always confined to the TJs, but may be found significantly at other subcellular locations such as basolareral membrane and intracellular domains [3]. Although the function of such claudins outside TJs is not well understood, our current results suggest that different Cld members have distinct priorities for accumulating at TJs in specific tissue epithelia and claudins outside TJs may localize at TJs in compensation for the original Clds in certain conditions. The compensatory effects might be influenced by the preference of physical interaction among given Cld members in each tissue.

Cld4 is expressed at the selective segments of nephrons, including the thin descending and ascending loops of Henle, connecting tubule, and collecting duct as well as the entire urothelium from the pelvis to the bladder [37](current results). Accumulating evidence indicates that Clds at TJs of the renal nephrons contribute to the transport of selected ions via a paracellular route [13], [38], [39]. Thus, Cld2 at the proximal tubule promotes the reabsorption of cations (Na+, Ca2+) by enhancing the paracellular leakiness [13], [38], whereas Cld4 has been shown to act as a paracellular Cl− channel in the collecting duct cell lines such as M-1 and mIMCD3 cells [14]. Current results indicated that Cldn4 −/− mice showed selective increase of FECl, in agreement with the proposed role of Cld4 in the paracellular reabsorption of Cl− in the collecting duct. The reason why FECa was also increased in Cldn4 −/− mice remained to be investigated. One possibility is that compensatory expression of Cld3, which is shown to be a sealing component of TJs for ions and either charged and uncharged solutes [40], may inhibit Ca2+ reabsorption. Secondary effects of decreased Cl− reabsorption may also be considered. In either case, Cldn4 −/− mice with free access to water and food tended to show increased urine volume with diminished osmolality, probably reflecting the increase of FECa and FECl. However, Cldn4 −/− mice had completely normal capacity for concentrating urine upon dehydration with no evidence of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, and thus it was quite unlikely that the progressive hydronephrosis in Cldn4 −/− mice was nephrogenic.

IVP examination indicated that the urinary flow was retarded to variable extents in Cldn4 −/− mice prior to the overt development of hydronephrosis. The effect was observed unilaterally in many cases, suggesting the obstructive changes in the upper urinary tract. Cld4 is expressed along the entire urinary tract with many other Clds [23], [30], [41] and is localized at the TJs of the uppermost umbrella cells as well as throughout the plasma membranes of the underlying urothelial cells. In the urothelium of Cldn4 −/− mice, Cld7 expression was specifically enhanced at TJs, while the expression profiles of Cld3 and other Clds were unchanged. The effect was again attributable to the accumulation of preexisting Cld7 at TJs rather than the upregulation of Cld7 protein expression, and it was indicated that the types of compensatory Clds for Cld4 at TJs depended on the context of epithelial cell types. Probably due to the compensatory effect, the TJ formation in the urothelium was apparently unaffected in Cldn4 −/− mice, with grossly normal barrier function. However, it was found that the urothelium of the renal pelvis and ureters showed diffuse hyperplasia and thickening in Cldn4 −/− mice as they aged. The BrdU labeling experiments in vivo indicated that the urothelial cells in Cldn4 −/− mice showed markedly increased BrdU uptake with 4-day pulsing, whereas BrdU+ cells were rarely detected in the Cldn4 +/− urothelium. The effect was apparently “sterile,” and no associated inflammation was observed. The finding was quite surprising, considering the slow turnover rate of urothelial cells (∼3–6 months) in normal mice [23]. The change was observed prior to the development of hydronephrosis and thus was unlikely due to a secondary effect.

The mechanism for the deregulated urothelial cell proliferation in Cldn4 deficiency remains to be investigated. Of note, Cldn15 −/− mice develop mega-intestine with nonneoplastic, deregulated increase of intestinal epithelial cells [18], [42]. The effects may be indirect ones caused by the altered cell microenvironment, such as ion concentrations, due to the changes of paracellular leakiness [43]. Alternatively, Clds may directly regulate cell proliferation. It was reported that Cld2 expressed in colon cancer cells promoted EGFR-mediated proliferation in vitro [20], [21], and we reported that Cld4 in the thymocytes was capable of enhancing the TCR-mediated ERK activation [22]. In this regard, it is noted that the defect of uroplakins, which form UP crystals covering the apical surface of umbrella cells, also results in the urothelial hyperplasia of ureters, leading to rapid progression of hydronephrosis [35], [36]. Because the urothelium of Cldn4 −/− mice showed normal UPs, the effect should be independent of the UPs. While UPs cover the apical surface of the uppermost umbrella cell layer, Cld4 is localized not only at the TJs between the umbrella cells but distributed diffusely throughout plasma membranes of underlying urothelial cell layers. The apical surface of umbrella cells is associated with heparin-binding epidermal growth factor (EGF), and the smooth muscle cells surrounding the urothelium also produce EGF [44], [45]. Thus, it may be possible that UPs and Cld4 regulate the availability of EGF and/or the signaling of EGFR. In either case, these results suggest that Cld4 and UPs independently regulate homeostatic urothelial cell proliferation. Relatively late onset and chronic progression of hydronephrosis in Cldn4 −/− mice, as opposed to early and rapid progression in UP −/− mice, may be due in part to the compensatory function of Cld7 at TJs. Although we have not observed overt tumor development in Cldn4 −/− mice, effects of urinary chemical carcinogens are under investigation.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that Cldn4 −/− mice develop chronic urothelial hyperplasia and eventually overt hydronephrosis. Our results indicate that Clds play an important role in maintaining urothelial integrity and provide insights into the function of Clds in tissue homeostasis.

Materials and Methods

Cldn4 −/− Mice

A targeting vector (Figure S1A) was introduced into D3a2 embryonic stem (ES) cells [46]. Correctly targeted ES cells (Figure S1B) were injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts and transferred into foster mothers to develop heterozygous mice. These mice were further mated with CAG-cre transgenic mice [47] to delete the neomycin cassette and floxed Cldn4. Mice were maintained in specific pathogen-free conditions at Kyoto University’s Laboratory Animal Center in accordance with University guidelines.

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used: anti-Cld2, anti-Cld4, Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated anti-Cld4, anti-Cld13 (Invitrogen), anti-Cld3 (Novus), anti-Cld7, anti-TRPV5 (Abcam), anti-Cld8, anti-Cld12 (IBL), anti-AQP1 (Millipore), anti-ClC-K (Alomone Labs), anti-THP (Biomedical Technologies), anti-AQP2 (a kind gift from Dr. Y. Noda, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Tokyo), anti-pan-Keratin (DAKO), anti-E-Cadherin (Takara), anti-β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated anti-BrdU (BD Bioscience) and anti- ZO-1 (obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, The University of Iowa, USA). Secondary reagents were as follows: Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated streptavidin, donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen), Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-rat IgG and anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson), Horse-radish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (GE healthcare) and anti-goat IgG (KPL).

Immunostaining

Tissue immunostaining was performed as described before [48]. Tissues were snap-frozen with liquid nitrogen in OCT compound (Sakura), and tissue sections (6-µm thickness) were fixed with 95% ethanol followed by 100% acetone. The sections were blocked and incubated with primary antibodies, followed by secondary antibodies or reagents. For BrdU staining, mice were injected intraperitoneally with BrdU (1.0 mg/animal) for 4 consecutive days, and the tissue sections were first stained with pan-keratin followed by fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde/phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). After washing, sections were treated with 4 N HCl for 20 minutes, neutralized with 0.2 M sodium borate (pH 8.5), and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated anti-BrdU monoclonal antibody. The samples were examined with a microscope (Carl Zeiss), and the images were processed with Photoshop.

In vivo Permeability Assay

Anesthetized mice were injected with sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin (606.9 Da, 1 mg/PBS containing 1 mM CaCl2 and methylene blue) into the bladder using a 27-gauge needle. After 20 minutes, mice were sacrificed, and the tissues were subjected to immunostaining. Biotin was detected with Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated streptavidin.

Intravenous Pyelography

Mice were anesthetized and injected intravenously with Omnipaque (Daiichi Sankyo, 3 µl/g of body weight), followed by serial radiographs at 5, 15, and 30 minutes with the use of SOFTEX CMB-2(SOFTEX).

Electron and Scanning Microscopy

For transmission electron microscopy, the tissues were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde in PBS, post-fixed with osmium tetroxide, embedded in Epon, and examined under a HITACHI H-7650 microscope. For scanning electron microscopy, tissues were fixed as for transmission electron microscopy, critical-point dried, and examined with a HITACHI H-4700 microscope.

Plasma and Urine Analysis

Mice were kept in metabolic cages for 24 hours with free access to water and food. Urine samples were collected twice at an interval of 1 week and the average values were used for the statistical analysis. After the second urine collection, mice were sacrificed and whole blood was collected. Urine and serum ions were measured with an autoanalyzer (Hitachi-7180, Hitachi Instruments), and urine osmolality was measured by freezing-point depression osmometry (OM-6030, OM-6050, and OM-6060, Arkray). For the urine concentration test, urine samples were collected after animals were deprived of water for 24 hours.

Histology

Tissues were fixed in 10% formalin neutral buffer solution (Wako) and embedded in paraffin, and the sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Immunoblotting

Kidneys were homogenized with FastPrep24 instrument (MP-biomedicals) in RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors. The mucosal layer of bladders was mechanically removed from muscle layer and lysed in lysing buffer (20 mM HEPES buffer pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate) containing protease inhibitors. Immunoblotting was performed as described before [49].

Quantitative RT-PCR

Kidney and bladder mucosa were frozen in liquid nitrogen and homogenized with FastPrep24 in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). RNA was extracted and transcribed into cDNA with Super-Script III (Invitrogen). Real-time PCR was performed with a LightCycler SYBR Green I marker kit on a LightCycler instrument (Roche). The transcripts of each gene were normalized to those of cyclophilin. Primer sequences for Cldns were described before. [22].

Supporting Information

Establishment of Cldn4 −/− mice. (A) Schematic representation of the targeting vector. E, EcoRI digestion site. (B) A targeted allele was confirmed by Southern blotting analysis of EcoRI-digested genomic DNA using an indicated DNA probe. (C) Primer sets for detecting WT and deleted alleles of Cldn4.

(TIF)

Expression profiles of Cld4 in normal mouse renal nephrons and urothelium. (A) Sections of the kidneys of normal B6 mice were two-color immunostained with anti-Cld4 (green) and established markers for various segments of nephrons (red), including AQP1 (proximal tubule and thin descending loop of Henle), CIC-K (thin ascending loop of Henle), THP (thick ascending loop of Henle), AQP2 (connecting tubule and collecting duct), and TRVP5 (connecting tubule). Arrows, Vasa recta. Bars; 20 µm. (B) Schematic Cld4 expression profile in nephrons and urothelium is illustrated based on the results.

(TIF)

Protein and mRNA expression of other Cld members in Cldn4 −/− kidneys. (A) Cldn4 +/− and −/− kidneys were lysed and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (B) RNA was extracted from Cldn4 +/− and Cldn4 −/− kidneys and relative Cldns transcripts were assessed by qPCR The means of triplicate analysis are shown. The values are mean±SEM. 3-months old mice were used. L and R indicate left and right kidney respectively.

(TIF)

Protein expression of other Cld members in Cldn4 −/− urothelium. Cldn4 +/− and Cldn4 −/− bladder mucosa were lysed and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. 3-months old mice were used.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of our laboratory for helpful discussions. We thank Dr. T. Tsuruyama and Dr. A. Kanematsu for helpful discussions, Dr. J. Miyazaki for CAG-Cre Tg mice, and Mr. H. Koda and Mrs. K. Furuta for electron microscopic analysis.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Science, Sports and Technology of the Japanese Government to Y.H. and N.M. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Tsukita S, Furuse M, Itoh M (2001) Multifunctional strands in tight junctions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2: 285–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Furuse M (2010) Molecular basis of the core structure of tight junctions. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2: a002907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Angelow S, Ahlstrom R, Yu AS (2008) Biology of claudins. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F867–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anderson JM, Van Itallie CM (2009) Physiology and function of the tight junction. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 1: a002584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Furuse M, Hata M, Furuse K, Yoshida Y, Haratake A, et al. (2002) Claudin-based tight junctions are crucial for the mammalian epidermal barrier: a lesson from claudin-1-deficient mice. J Cell Biol 156: 1099–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nitta T, Hata M, Gotoh S, Seo Y, Sasaki H, et al. (2003) Size-selective loosening of the blood-brain barrier in claudin-5-deficient mice. J Cell Biol 161: 653–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gow A, Southwood CM, Li JS, Pariali M, Riordan GP, et al. (1999) CNS myelin and sertoli cell tight junction strands are absent in Osp/claudin-11 null mice. Cell 99: 649–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wilcox ER, Burton QL, Naz S, Riazuddin S, Smith TN, et al. (2001) Mutations in the gene encoding tight junction claudin-14 cause autosomal recessive deafness DFNB29. Cell 104: 165–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ben-Yosef T, Belyantseva IA, Saunders TL, Hughes ED, Kawamoto K, et al. (2003) Claudin 14 knockout mice, a model for autosomal recessive deafness DFNB29, are deaf due to cochlear hair cell degeneration. Hum Mol Genet 12: 2049–2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hayashi D, Tamura A, Tanaka H, Yamazaki Y, Watanabe S, et al. (2012) Deficiency of claudin-18 causes paracellular H+ leakage, up-regulation of interleukin-1beta, and atrophic gastritis in mice. Gastroenterology 142: 292–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hou J, Renigunta A, Gomes AS, Hou M, Paul DL, et al. (2009) Claudin-16 and claudin-19 interaction is required for their assembly into tight junctions and for renal reabsorption of magnesium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 15350–15355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tatum R, Zhang Y, Salleng K, Lu Z, Lin JJ, et al. (2010) Renal salt wasting and chronic dehydration in claudin-7-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F24–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Muto S, Hata M, Taniguchi J, Tsuruoka S, Moriwaki K, et al. (2010) Claudin-2-deficient mice are defective in the leaky and cation-selective paracellular permeability properties of renal proximal tubules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107: 8011–8016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hou J, Renigunta A, Yang J, Waldegger S (2010) Claudin-4 forms paracellular chloride channel in the kidney and requires claudin-8 for tight junction localization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107: 18010–18015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Van Itallie C, Rahner C, Anderson JM (2001) Regulated expression of claudin-4 decreases paracellular conductance through a selective decrease in sodium permeability. J Clin Invest 107: 1319–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hamazaki Y, Itoh M, Sasaki H, Furuse M, Tsukita S (2002) Multi-PDZ domain protein 1 (MUPP1) is concentrated at tight junctions through its possible interaction with claudin-1 and junctional adhesion molecule. J Biol Chem 277: 455–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lanaspa MA, Andres-Hernando A, Rivard CJ, Dai Y, Berl T (2008) Hypertonic stress increases claudin-4 expression and tight junction integrity in association with MUPP1 in IMCD3 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105: 15797–15802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tamura A, Kitano Y, Hata M, Katsuno T, Moriwaki K, et al. (2008) Megaintestine in claudin-15-deficient mice. Gastroenterology 134: 523–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Swisshelm K, Macek R, Kubbies M (2005) Role of claudins in tumorigenesis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 57: 919–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Buchert M, Papin M, Bonnans C, Darido C, Raye WS, et al. (2010) Symplekin promotes tumorigenicity by up-regulating claudin-2 expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107: 2628–2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dhawan P, Ahmad R, Chaturvedi R, Smith JJ, Midha R, et al. (2011) Claudin-2 expression increases tumorigenicity of colon cancer cells: role of epidermal growth factor receptor activation. Oncogene 30: 3234–3247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kawai Y, Hamazaki Y, Fujita H, Fujita A, Sato T, et al. (2011) Claudin-4 induction by E-protein activity in later stages of CD4/8 double-positive thymocytes to increase positive selection efficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108: 4075–4080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Khandelwal P, Abraham SN, Apodaca G (2009) Cell biology and physiology of the uroepithelium. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F1477–1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wu XR, Kong XP, Pellicer A, Kreibich G, Sun TT (2009) Uroplakins in urothelial biology, function, and disease. Kidney Int 75: 1153–1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sabolic I, Valenti G, Verbavatz JM, Van Hoek AN, Verkman AS, et al. (1992) Localization of the CHIP28 water channel in rat kidney. Am J Physiol 263: C1225–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Uchida S, Sasaki S, Nitta K, Uchida K, Horita S, et al. (1995) Localization and functional characterization of rat kidney-specific chloride channel, ClC-K1. J Clin Invest 95: 104–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Loffing J, Loffing-Cueni D, Valderrabano V, Klausli L, Hebert SC, et al. (2001) Distribution of transcellular calcium and sodium transport pathways along mouse distal nephron. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F1021–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fushimi K, Uchida S, Hara Y, Hirata Y, Marumo F, et al. (1993) Cloning and expression of apical membrane water channel of rat kidney collecting tubule. Nature 361: 549–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hession C, Decker JM, Sherblom AP, Kumar S, Yue CC, et al. (1987) Uromodulin (Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein): a renal ligand for lymphokines. Science 237: 1479–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Acharya P, Beckel J, Ruiz WG, Wang E, Rojas R, et al. (2004) Distribution of the tight junction proteins ZO-1, occludin, and claudin-4, -8, and -12 in bladder epithelium. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287: F305–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Matsumura Y, Uchida S, Kondo Y, Miyazaki H, Ko SB, et al. (1999) Overt nephrogenic diabetes insipidus in mice lacking the CLC-K1 chloride channel. Nat Genet 21: 95–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lloyd DJ, Hall FW, Tarantino LM, Gekakis N (2005) Diabetes insipidus in mice with a mutation in aquaporin-2. PLoS Genet 1: e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McDill BW, Li SZ, Kovach PA, Ding L, Chen F (2006) Congenital progressive hydronephrosis (cph) is caused by an S256L mutation in aquaporin-2 that affects its phosphorylation and apical membrane accumulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 6952–6957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yang B, Zhao D, Qian L, Verkman AS (2006) Mouse model of inducible nephrogenic diabetes insipidus produced by floxed aquaporin-2 gene deletion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 291: F465–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hu P, Deng FM, Liang FX, Hu CM, Auerbach AB, et al. (2000) Ablation of uroplakin III gene results in small urothelial plaques, urothelial leakage, and vesicoureteral reflux. J Cell Biol 151: 961–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kong XT, Deng FM, Hu P, Liang FX, Zhou G, et al. (2004) Roles of uroplakins in plaque formation, umbrella cell enlargement, and urinary tract diseases. J Cell Biol 167: 1195–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kiuchi-Saishin Y, Gotoh S, Furuse M, Takasuga A, Tano Y, et al. (2002) Differential expression patterns of claudins, tight junction membrane proteins, in mouse nephron segments. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 875–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Muto S, Furuse M, Kusano E (2012) Claudins and renal salt transport. Clin Exp Nephrol 16: 61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hou J, Goodenough DA (2010) Claudin-16 and claudin-19 function in the thick ascending limb. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 19: 483–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Milatz S, Krug SM, Rosenthal R, Gunzel D, Muller D, et al. (2010) Claudin-3 acts as a sealing component of the tight junction for ions of either charge and uncharged solutes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1798: 2048–2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Varley CL, Garthwaite MA, Cross W, Hinley J, Trejdosiewicz LK, et al. (2006) PPARgamma-regulated tight junction development during human urothelial cytodifferentiation. J Cell Physiol 208: 407–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tamura A, Hayashi H, Imasato M, Yamazaki Y, Hagiwara A, et al. (2011) Loss of claudin-15, but not claudin-2, causes Na+ deficiency and glucose malabsorption in mouse small intestine. Gastroenterology 140: 913–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tsukita S, Yamazaki Y, Katsuno T, Tamura A, Tsukita S (2008) Tight junction-based epithelial microenvironment and cell proliferation. Oncogene 27: 6930–6938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Parries G, Chen K, Misono KS, Cohen S (1995) The human urinary epidermal growth factor (EGF) precursor. Isolation of a biologically active 160-kilodalton heparin-binding pro-EGF with a truncated carboxyl terminus. J Biol Chem 270: 27954–27960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Freeman MR, Yoo JJ, Raab G, Soker S, Adam RM, et al. (1997) Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor is an autocrine growth factor for human urothelial cells and is synthesized by epithelial and smooth muscle cells in the human bladder. J Clin Invest 99: 1028–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shull MM, Ormsby I, Kier AB, Pawlowski S, Diebold RJ, et al. (1992) Targeted disruption of the mouse transforming growth factor-beta 1 gene results in multifocal inflammatory disease. Nature 359: 693–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sakai K, Miyazaki J (1997) A transgenic mouse line that retains Cre recombinase activity in mature oocytes irrespective of the cre transgene transmission. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 237: 318–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hamazaki Y, Fujita H, Kobayashi T, Choi Y, Scott HS, et al. (2007) Medullary thymic epithelial cells expressing Aire represent a unique lineage derived from cells expressing claudin. Nat Immunol 8: 304–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shimatani K, Nakashima Y, Hattori M, Hamazaki Y, Minato N (2009) PD-1+ memory phenotype CD4+ T cells expressing C/EBPalpha underlie T cell immunodepression in senescence and leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 15807–15812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Establishment of Cldn4 −/− mice. (A) Schematic representation of the targeting vector. E, EcoRI digestion site. (B) A targeted allele was confirmed by Southern blotting analysis of EcoRI-digested genomic DNA using an indicated DNA probe. (C) Primer sets for detecting WT and deleted alleles of Cldn4.

(TIF)

Expression profiles of Cld4 in normal mouse renal nephrons and urothelium. (A) Sections of the kidneys of normal B6 mice were two-color immunostained with anti-Cld4 (green) and established markers for various segments of nephrons (red), including AQP1 (proximal tubule and thin descending loop of Henle), CIC-K (thin ascending loop of Henle), THP (thick ascending loop of Henle), AQP2 (connecting tubule and collecting duct), and TRVP5 (connecting tubule). Arrows, Vasa recta. Bars; 20 µm. (B) Schematic Cld4 expression profile in nephrons and urothelium is illustrated based on the results.

(TIF)

Protein and mRNA expression of other Cld members in Cldn4 −/− kidneys. (A) Cldn4 +/− and −/− kidneys were lysed and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (B) RNA was extracted from Cldn4 +/− and Cldn4 −/− kidneys and relative Cldns transcripts were assessed by qPCR The means of triplicate analysis are shown. The values are mean±SEM. 3-months old mice were used. L and R indicate left and right kidney respectively.

(TIF)

Protein expression of other Cld members in Cldn4 −/− urothelium. Cldn4 +/− and Cldn4 −/− bladder mucosa were lysed and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. 3-months old mice were used.

(TIF)