Abstract

In echoic environments, direct sounds dominate perception even when followed by their reflections. As the delay between the direct (lead) source and the reflection (lag) increases, the reflection starts to become localizable. Although this phenomenon, which is part of the precedence effect, is typically studied with brief transients, leading and lagging sounds often overlap in time and are thus composed of three distinct segments: the “superposed” segment, when both sounds are present together, and the “lead-alone” and “lag-alone” segments, when leading and lagging sounds are present alone, respectively. Recently, it was shown that the barn owl (Tyto alba) localizes the lagging sound when the lag-alone segment, not the lead-alone segment, is lengthened. This was unexpected given the prevailing hypothesis that a leading sound may briefly desensitize the auditory system to sounds arriving later. The present study confirms this finding in humans under conditions that minimized the role of the superposed segment in the localization of either source. Just as lengthening the lag-alone segment caused the lagging sound to become more salient, lengthening the lead-alone segment caused the leading sound to become more salient. These results suggest that the neural representations of the lead and lag are independent of one another.

INTRODUCTION

In nature, sounds from an actively emitting source are often followed by reflections off of nearby objects. Yet, the sources of these reflections are often difficult to localize and the active or “direct” sound-source dominates our perception (Wallach et al., 1949; Haas, 1951). These are two commonly reported facets of the precedence effect (Blauert, 1997; Litovsky et al., 1999). As the delay between the direct sound and reflection increases, the two sources are perceived as spatially distinct events.

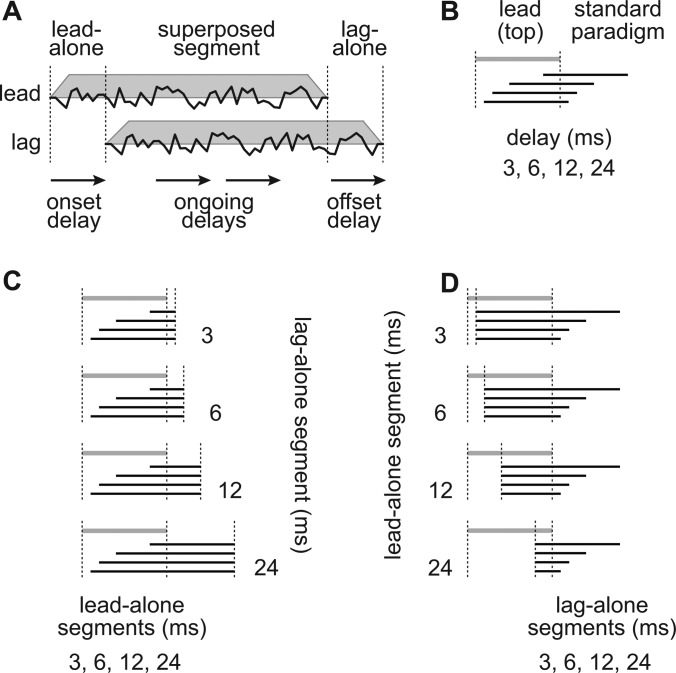

Sounds in nature are often longer than the delays after which reflections arrive, so the reflection and the direct sound overlap temporally [Fig. 1a]. Even pairs of transients such as clicks will cause cochlear filters to ring, thus prolonging their internal representations and causing them to overlap (Hartung and Trahiotis, 2001; Trahiotis and Hartung, 2002). For these overlapping stimuli, the direct (leading) sound is present alone prior to the onset of the echo. Similarly, the later-arriving echo (lagging) sound is present alone after the offset of the leading sound [Fig. 1a]. These two stimulus segments will hereafter be referred to as the lead-alone and lag-alone segments. The period of time when both sounds are present will be referred to as the superposed segment.

Figure 1.

Illustrations of the stimuli, stimulus segments, and delays created by overlapping lead and lag sounds. (a) The lead stimulus is present alone for a length of time equal to the onset delay. Both sounds are then present during the superposed segment, as are ongoing delays between the corresponding features of the lead and lag stimuli. Finally, the lag stimulus is present alone (offset delay). (b) Illustration of the standard paradigm, with lead and lag stimuli of the same length (30 ms). A single gray line indicates the lead stimulus. Black lines indicate lag stimuli, which are identical to the lead. (c) Illustrations of the experimental paradigm with the lag-alone segment fixed at 3, 6, 12, or 24 ms and the lead-alone segment (onset-delay) was varied. (d) Same stimuli as in (c) except that the lag-alone segment is varied while the lead-alone segment (onset delay) is fixed at 3, 6, 12, and 24 ms.

Under such conditions, the delay between the lead and lag stimuli can be defined in at least three different ways. First, an onset delay is produced corresponding to the length of time between the onset of the leading sound and the echo [i.e., the lead-alone segment in Fig. 1a]. This is sometimes called the “echo-delay.” Second, ongoing delays between the corresponding features in the waveforms of the leading and lagging sounds can be defined during the superposed segment. Last, the period of time between the offsets of the leading and lagging sounds defines the lag-alone segment. Each of these various delays could potentially contribute to hearing in echoic environments.

In a recent study of sound localization in the barn owl (Tyto alba), the lag-alone segment was varied independently of the onset and ongoing delays. For the 30 ms noise bursts used in that study, the tendency of the owls to localize the lagging sound depended on the duration of the lag-alone segment, not on the onset and ongoing delays (Nelson and Takahashi, 2008). These results were inconsistent with the prevailing hypothesis that a leading sound may briefly desensitize the auditory system to sounds arriving later, possibly by a lateral-inhibitionlike mechanism triggered by the onset of the leading sound (Harris et al., 1963; McFadden, 1973; Zurek, 1980; Lindemann, 1986; Yin, 1994; Fitzpatrick et al., 1995; Keller and Takahashi, 1996; Burger and Pollak, 2001; Spitzer et al., 2004; Pecka et al., 2007). If such a mechanism operated, one would expect that the localization of a lagging sound would depend on the length of the lead-alone segment. The present study attempts to replicate these findings in human listeners and further explore the roles of the lead and lag-alone segments in the precedence effect.

In order to study the “alone” segments independently of the superposed segment, the latter's contribution was minimized by shortening it. To confirm the efficacy of this manipulation, a short superposed segment was first shown to contribute little to the lateralization of either source. That the lag-alone segment determines when the lagging sound becomes localizable was then shown. Because the lagging sound's localizability depended upon the lag-alone segment, not the lead-alone segment, the possibility that the leading sound's localizability depends on the length of the lead-alone segment was explored. Results suggest that the lead-alone segment influenced the leading source's localizability when the lag-alone segment was consistently long. Thus, for the 30 ms, partially overlapped stimuli used in the present study, human auditory spatial perception appears to depend on the durations of the segments when only one source or the other is present.

In the literature, the terms fusion, localization dominance, and lag-discrimination suppression have been introduced to describe components of the precedence effect (Litovsky et al., 1999). When interpreting the experiments below, fusion is operationally defined as the reporting of a single auditory event, regardless of the precision or accuracy with which the event was localized. Lead-dominance is operationally defined as the preferential localization or lateralization of the leading source. Correspondingly, lead-dominance is viewed as having ended when the two sources were lateralized in equal proportions. Lag-dominance is defined as the preferential localization or lateralization of the lagging source (see also Litovsky and Godar, 2010; Goupell et al., 2012). The sources of lagging sounds are occasionally difficult to localize, a phenomenon referred to as lag-discrimination suppression. Under certain experimental conditions, listeners are shown to occasionally be uncertain of the leading source's location (Litovsky and Godar, 2010; Goupell et al., 2012). Therefore, the terms lag-uncertainty and lead-uncertainty are used.

GENERAL METHODS

Experiments were carried out under a protocol approved by the University of Oregon Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Human Subjects. A total of 14 listeners with no self-reported hearing loss were recruited from the University of Oregon (7 female, 7 male; 19–23 years old). Different listeners were tested in Experiments 2 and 3. Four of these listeners were tested in Experiment 1. The composition of the participant pool is specified below for the individual experiments.

Stimuli generally consisted of 30-ms bursts of noise (2.5 ms linear on/off ramps; 0.2–11 kHz bandwidth) presented over headphones with interaural time differences (ITD) of +250 μs (right) and -250 μs (left), which placed the intracranial images on either side of the midline. Four stimulus configurations were tested.

-

(i)

In Experiment 1, pairs of identical lead/lag noises were presented with a 3 ms delay but with their onsets and offsets synchronized, leaving only the ongoing delays [Fig. 2a]. Similar stimuli consisting of 200-ms bursts of noise were also presented [Fig. 2c]. Comparison of the results for this stimulus and those for two independent noises [Fig. 2b; see configuration (iv) below] allowed the contributions from ongoing delays to be estimated.

-

(ii)

In the “standard paradigm” [Fig. 1b] used in Experiments 2 and 3, two identical noise bursts were presented with a delay of 3, 6, 12, or 24 ms. The leading and lagging sounds were equal in length. As a result, the delay between the onsets and offsets of the noise bursts as well as the delays between corresponding features in the superposed segments, or “ongoing delays,” were all equal. This paradigm is similar to that used in other studies.

-

(iii)

In the “experimental paradigm” [Figs. 1c, 1d] used in Experiments 2 and 3, the length of the lag-alone segment was manipulated independently of the lead-alone segment. To generate the lagging sound in the experimental paradigm, the leading sound was replicated, and the replica was delayed by 3, 6, 12, or 24 ms. The lag-alone segment was then extended or truncated to lengths of 3, 6, 12, or 24 ms. Noise added to the lagging sound was unrelated and therefore uncorrelated to the leading sound. However, the portion of the leading sound that would have been correlated to the lag-alone segment had the stimuli been presented separately was most often superposed with the lagging sound. The alone segments were also separated in time by at least a brief superposed segment. Correlations of the leading and lagging sounds within an ear were therefore low. Note that when the onset and ongoing delays are equal, they are collectively referred to as the “onset/ongoing delay.” As a result, a lead/lag pair can have an onset/ongoing delay of one value and a lag-alone segment of a different value.

-

(iv)

Experiments 1 and 2 included a reference condition, which we called “two-independent noises.” Two statistically independent noise-bursts were synthesized: one was presented with an ITD of +250 μs, and the other, which was presented concomitantly, had an ITD of −250 μs. If either noise-burst was presented alone, a listener would presumably hear the sound on one side of the midline or the other. The onsets and offsets of this noise pair were synchronized so that they began and ended simultaneously. This provided a reference condition for the percept evoked by two independent sounds from the same locations as the lead/lag pairs, but in which a lead/lag relationship was undefined due to the lack of onset, offset, and ongoing delays. The effects of consistent delays could thus be isolated from the effects of having two simulated sound sources.

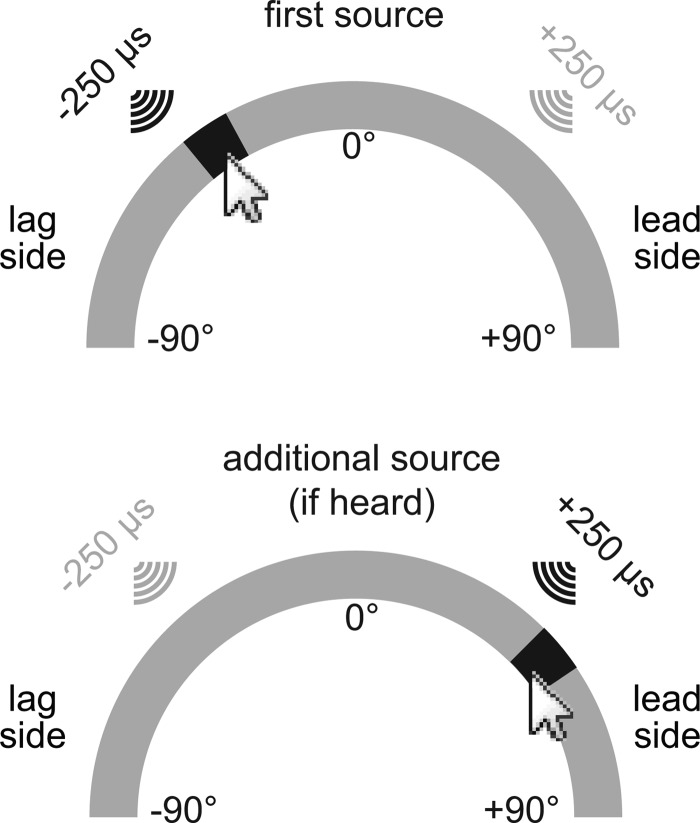

Figure 2.

Illustration of the computer interface used. Listeners were told that each arc represented the frontal hemifield (180°) at eye level. If only one auditory image was perceived, subjects were instructed to indicate the image's central azimuth on the arc nearest the top of the computer screen. The bottom arc was not visible in Experiments 1 and 3. If an additional auditory image was perceived in Experiment 2, subjects were instructed to indicate its central azimuth on the arc nearest the bottom of the computer screen.

Stimuli were presented over headphones (Industrial Acoustics, Bronx, NY; Sennheiser HD 280 Pro, Old Lyme, CT) to subjects in one of two double-walled anechoic or noise attenuating chambers (Industrial Acoustics Co. Bronx, NY; 4.5 m × 3.9 m × 2.7 m or 2.2 m × 2.1 m × 2.0 m). Stimulus presentation and data acquisition were controlled using custom software (MATLAB, The Mathworks, Natick, MA). Sounds were synthesized and presented (48.8 kHz sampling rate) using a real-time audio processor and headphone amplifier (RP2.1, HB6; Tucker-Davis Technologies, Alachua, FL). The noise bursts, presented alone (i.e., not as part of a lead/lag pair), were approximately 75 dB (re: 20 μPa) at the headphones.

Listeners were asked to indicate the locations of the intracranial images generated by the various stimulus configurations. When only a single auditory image was perceived, the subjects were instructed to indicate its centroid on an arc representing the possible intracranial positions [−90° (left) to +90° (right); upper Fig. 2; Blauert and Lindemann, 1986; Litovsky and Godar, 2010]. In Experiment 2, the listeners were asked to mark an additional centroid on a second arc (lower Fig. 2) if an additional source was heard. The arcs were rendered on a flat computer display, and the perceived loci of the intracranial images were marked on the arcs by the press of a mouse button. This procedure requires subjects to transfer the position of an intracranial image onto a representation in extra-personal space. For this reason, we did not quantify the precision of the listener's marks on the arc(s), only their laterality (left or right).

The locations marked by the listeners on the arc(s) were plotted as distributions like those shown in Fig. 4. The leading stimulus could have an ITD of −250 μs or +250 μs on any trial. To visualize the data, however, locations indicated by the listeners are plotted as though leading stimuli always came from the right (+250 μs ITD) and lagging stimuli always came from the left (−250 μs ITD; solid lines, filled symbols). Thus, the right side of each arc (azimuth > 0°; Fig. 2) is referred to as the “leading side” and the left side is referred to as the “lagging side.” To implement this procedure, the magnitude of a subject's response (dashed lines, unfilled symbols), in degrees along the arc(s), was multiplied by the sign of the leading stimulus’ ITD. For instance, if the leading stimulus had an ITD of −250 μs on a given trial, and the subject reported that the stimulus appeared to come from −45° (i.e., 45 ° to the left), the response was plotted as +45°. If, instead, the subject had indicated +45° on the same trial, which would be equivalent to having lateralized the lag, the response was plotted as −45°. Solid lines with filled symbols represent the results of this transformation. Components of the precedence effect were inferred from such distributions after the transformation.

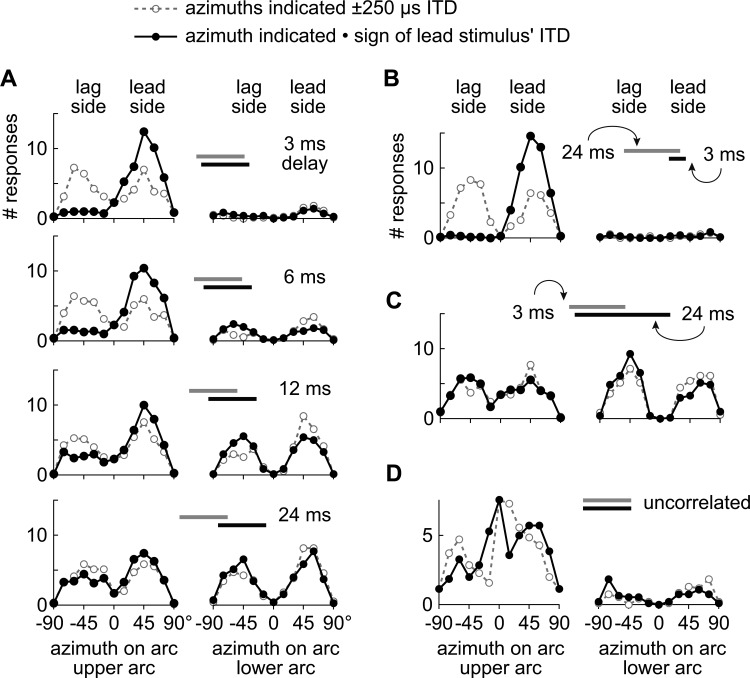

Figure 4.

Locations indicated by subjects on the top (left distribution) and bottom (right distribution) arcs illustrated in Fig. 2. Dashed lines and unfilled symbols show the raw data; i.e., locations indicated by the listeners without regard to whether the lead or lag stimulus was spatialized to the left (−250 μs ITD) or right (+250 μs ITD). The heavy solid lines and filled symbols show the same data plotted as if the lead always came from the right and the lag from the left. For each distribution, the frontal hemifield is represented on the abscissa with values ranging from −90 (left) to +90 (right). (a) Under the standard paradigm, subjects rarely indicated an additional source when the delay was short (3 ms), as shown by the absence of responses in the right distribution. The leading stimulus was also almost always lateralized according to its ITD. Subjects indicated an additional source with increasing frequency as the delay increased, but were unable to distinguish temporal order (see text). (b) Distributions when the lead-alone segment (onset delay) was long (24 ms) and the lag-alone segment was short (3 ms). (c) Distributions when the lead-alone segment (onset delay) was short (3 ms) and the lag-alone segment was long (24 ms). (d) Distributions when the stimuli were two 30 ms independent noises.

EXPERIMENT 1

Leading sounds can dominate spatial perception even when the onsets and offsets of the identical lead/lag noise stimuli are synchronized, leaving only a short ongoing delay (Zurek, 1980; Dizon and Colburn, 2006). To isolate contributions from the lead and lag-alone segments, the superposed segment's contribution had to be minimized. As shown in this control experiment, the leading sound's dominance was weak or did not occur when the superposed segment was shorted from 200 ms to 30 ms.

Design

Lead/lag pairs were synthesized with a 3 ms delay. The lead and lag-alone segments were then excised, leaving only a 30-ms long superposed segment containing a 3 ms ongoing delay [Fig. 3a]. The temporal relationship between the paired sounds was thus discernible only from the ongoing delay. Four subjects, who also participated in Experiments 2 and 3, were instructed to focus on the “clearest” source heard and to indicate its centroid on an arc representing the possible intracranial positions [−90° (left) to +90° (right); upper Fig. 2]. Note that in this task, the listeners are making a subjective choice between the two images based on their perceived clarity and then lateralizing the clearest image. Listeners were given no further instructions regarding clarity to avoid biasing their subjective judgment.

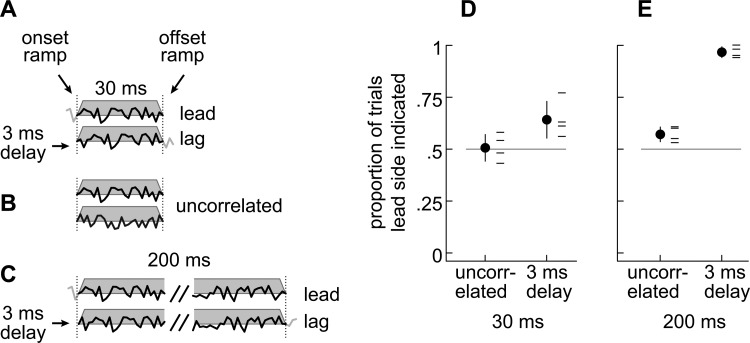

Figure 3.

Stimuli and results from Experiment 1. (a) Identical lead and lag stimuli (33 ms), ramped so that the lead and lag-alone segments (gray segments; 3 ms delay) were removed, leaving only the 30 ms superposed segment. (b) Two 30 ms independent noises. (c) Stimuli similar to those in (b) except that the stimuli were 200 ms after removing the lead and lag-alone segments (gray segments; 3 ms delay; 200 ms independent noises not shown). (d) Proportions of trials inwhich subjects indicated the lead source to be clearer when the stimuli were 30 ms. Thin horizontal lines indicate each of the four listeners and a circle indicates the average across subjects (±1 s.d.). In three of four listeners (horizontal lines), the responses obtained with identical lead/lag pairs could not be distinguished from those obtained with a pair of independent noises. Subject 4 was an exception (P < 0.05; contingency table analysis). (e) Same as (d) but with stimuli that were 200 ms. The leading stimulus was nearly always reported as producing the clearer auditory image (right) compared to results obtained with short lead/lag pairs or with independent 200-ms pairs.

To verify our methods and corroborate previous results, longer 200 ms stimuli were also presented [Fig. 3c]. To isolate the effects of an ongoing delay from the effects of acoustical superposition, pairs of independent 30 ms or 200 ms noises were interspersed among the trials [Fig. 3b; independent 200 ms noises not shown).

Each stimulus (n = 4) was presented 50 times in random order, over 2 listening sessions (400 total trials) for each subject. Before each trial (500 ms), listeners heard a diotic noise (30 ms or 200 ms) that provided a sense of the midline as a reference.

Results and discussion

Results are shown in Fig. 3d, which plots the proportions of trials in which the leading side was indicated for independent stimuli and for identical stimulus pairs with ongoing delays. Three of the four listeners indicated the leading side 50% of the time, which is no different than the responses to a pair of independent noises. Thus, for a delay of 3 ms and an overall stimulus length of 30 ms, the superposed segment contributed inconsistent spatial information on any single trial and little spatial information, on average, over numerous trials.

To ensure that this lack of an effect was due to the brevity of the stimuli, 200 ms stimuli were also presented [Fig. 3c]. As shown in Fig. 3e, the leading side was nearly always reported when the two sounds were identical (>95% of trials). Ongoing delays therefore appear to have contributed little to the leading sound's dominance when the stimuli were short (30 ms), but the contributions were quite strong when the stimuli were several times longer than the lengths of the lead and lag-alone segments tested in Experiments 2 and 3.

EXPERIMENT 2

Design

Experiment 1 demonstrated that the superposed segment is unlikely to contribute significant spatial information when its length is shorter than approximately 30 ms. Here, the contributions of lead and lag-alone segments were tested when their lengths were equal (standard paradigm) or when the length of the lag-alone segment was manipulated independently of the lead-alone segment (experimental paradigms).

Subjects (5 female, 2 male) in this experiment were asked to listen for one or two sounds and to indicate the locations of the intracranial images. When only a single auditory image was perceived, the subjects were instructed to indicate its centroid on an arc representing the possible intracranial positions [−90° (left) to +90° (right); upper Fig. 2]. If they perceived an additional auditory image, listeners were asked to mark its centroid on the lower arc (Fig. 2).

Each stimulus [Figs. 1c and 1(d); n = 17] was presented ten times in random order, over five listening sessions (850 total trials) for each subject. Before each trial (500 ms), listeners heard a diotic noise burst of variable length (33–54 ms) that provided a sense of the midline as a reference.

Results and discussion

Figure 4 shows the average distributions of locations indicated by the subjects on the first (lead) and lower (lag) arcs (dashed lines, open symbols). Figure 4a shows the distributions of locations indicated under the “standard paradigm,” in which the lengths of the lead-alone segment, ongoing delay, and lag-alone segment were all equal. As expected, when the delay was short, there was a high incidence of responses on the leading side of the upper arc, and very few responses on the lower arc. That the listeners always heard at least one auditory image that corresponded to the leading source was inferred from this pattern. As the delay was increased, as shown by each plot in descending order, listeners were increasingly likely to indicate the lagging source, until the delay was 24 ms, at which point, listeners reported the lagging source in roughly half the trials. This suggests that the listeners heard an auditory image that corresponded to the leading source and an additional image that corresponded to the lagging source.

When subjects indicated an additional source, they behaved as though they were unable to determine the temporal order of the stimuli, as shown by the bimodal distributions on both arcs [Fig. 4a, solid lines, filled symbols; Stellmack et al., 1999]. Because responses are plotted as though the lead came from the right (+250 μs ITD), if subjects could determine the temporal order correctly, there should have been a high incidence of responses only on the right side of the first arc, and a high incidence of responses only on the left side of the lower arc.

Figures 4b, 4c show the distributions under the two most extreme experimental conditions when the lead-alone segment was 3 ms and the lag-alone segment was 24 ms [Fig. 4b] or vice versa [Fig. 4c]. When the lead-alone segment was long (24 ms) and the lag-alone segment was short (3 ms), subjects almost always indicated a single image on the leading side, as indicated by the high incidence of responses on the right side of the upper arc, and almost no responses on the lower arc. When the lead-alone segment was short (3 ms) and the lag-alone segment was long [24 ms; Fig. 4c], listeners almost always reported two sources. Notice that these responses resemble those obtained under the standard paradigm at a long delay [24 ms; Fig. 4a] despite the fact that the onset delay was only 3 ms. The responses on both arcs are bimodal, as in the standard paradigm, indicating that listeners were unable to determine the temporal order of lead and lag stimuli.

Figure 4d, which plots the results obtained with two independent sounds, shows that listeners typically reported a single auditory image that was difficult to lateralize. The loci indicated are widespread and clustered around the midline [Fig. 4d, left]. The additional source, when reported, was likewise difficult to lateralize [Fig. 4d, right]. These results reflect the listener's perceptual experience when there are two concurrent sound sources that have no consistent temporal (lead/lag) relationship. Comparing these results [Fig. 4d] with those for lead/lag pairs [Fig. 4a, e.g., top] shows that both conditions evoked a single auditory image, but the single image reported for the two independent noises was diffuse and difficult to localize. By contrast, the image evoked by the lead/lag pair caused listeners to lateralize the image on the lead side.

Distributions like those in Fig. 4 are next interpreted in terms of fusion, dominance, and uncertainty.

Fusion

Fusion is operationally defined as the reporting of a single auditory event, regardless of the precision or accuracy with which the event was localized.

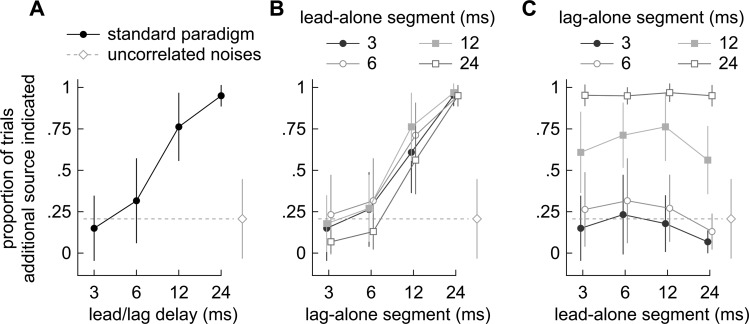

Results from the standard paradigm, in which the leading and lagging noises were equally long [Fig. 1b], are shown in Fig. 5a, which plots against delay, the proportion of trials in which listeners reported two images. Each filled circle represents the mean across subjects [±s.d. (standard deviation)]. Two sources were seldom reported at short delays, but as the delay was increased, two sources were reported more frequently. At a delay between 6 ms and 12 ms, listeners reported two sources in approximately half the trials [Fig. 5a]. Thus, the proportion of the trials in which a single source is reported, i.e., fusion, appears to decline with delay. In the standard paradigm, where onset, offset, and ongoing delays were all the same, the lead-alone, lag-alone, and superposed segments could each have potentially determined whether or not the additional (lagging) source was reported.

Figure 5.

(Color online) Proportions of trials in which subjects lateralized two sources, calculated for each stimulus pair. Each marker indicates the average across subjects (±1 s.d.). A dashed line in each panel shows the across-subject average obtained when two, 30 ms independent noises were presented. (a) Responses to lead/lag pairs under the standard paradigm, in which the lead-alone and lag-alone segments were the same length (30 ms). Subjects tended to report single sources at short delays (3 ms) and were more likely to indicate two sources as the delay increased. (b) Responses to lead/lag pairs with variable lead-alone segments (onset delays). The abscissa indicates the length of the lag-alone segment. Reports of two sources generally increase with the duration of the lag-alone segment (c) Responses are re-plotted to show the results of varying the lead-alone segment (abscissa) when the lag-alone segments were fixed at 3, 6, 12, or 24 ms. The proportions remained flat or even rose with the duration of the lead-alone segment (abscissa).

Figure 5b shows the effect on fusion of varying the lag-alone segments (abscissa) while holding the lead-alone segment constant. When the lag-alone segments were short (leftmost points), the tendency to report two sources was low (∼25%), suggesting that subjects experienced fusion. When the lag-alone segments were longer, the tendency to report two sources was higher (>∼75%). Interestingly, the plots look similar regardless of the length of the lead-alone segments. In other words, the tendency to report two sources seems to depend more on the duration of the lag-alone segment than on the onset/ongoing delays. This point can be seen more clearly in Fig. 5c which re-plots the data so that the effect of varying the onset/ongoing delay (abscissa) can be seen while holding the lag-alone segment at 3, 6, 12, and 24 ms. The proportion of trials in which the listeners reported two sources depended little on the onset/ongoing delay and the psychometric functions therefore remained rather flat.

When two independent noises were presented, subjects reported two sources in only about 25% of the trials (Fig. 5; dashed line). Interestingly, this performance is comparable to that observed in the standard paradigm at short delays, indicating that both types of stimuli cause subjects to report a single auditory image [3, 6 ms; Fig. 4a; p > 0.11, d.f. (degrees of freedom) = 807; pooled data; contingency table analysis] even though the images evoked by the two stimulus types differed in position and lateralizability [compare Fig. 4a, 3 ms, with Fig. 4d]. Performance began to deviate from that obtained with two independent noises when a long lead-alone segment, which is equivalent to a long echo delay, was combined with a short lag-alone segment [rightmost points of curves in Fig. 5c; 24 ms lead-alone, 3 ms lag-alone; p < 10-6, d.f. = 786]. This combination made subjects even more likely (re: two independent noises) to report only a single source, implying that fusion had strengthened.

These results suggest that fusion depends on the length of both the lead and lag-alone segment. An additional source was more readily reported as the lag-alone segment was lengthened. However, reports of the lagging source became less frequent when the lead-alone segment was lengthened. A short lead-alone segment certainly did not promote fusion as one might have expected given earlier results showing that a lagging source is detected when the echo-delay, which is analogous to the lead-alone segment, is long (Wallach et al., 1949; Haas, 1951; Blauert, 1997; Litovsky et al., 1999).

Dominance

The term “localization dominance” traditionally refers to the dominance of the leading source in a precedence-effect situation. Because earlier studies (Litovsky and Godar, 2010; Goupell et al., 2012) and evidence presented below (Figs. 68) suggest that the lagging sound can also dominate perception under certain experimental conditions, it is necessary to specify the dominating source. Therefore, lead-dominance is operationally defined as the preferential localization or lateralization of the leading source. Correspondingly, lead-dominance is viewed as having ended when the two sources were lateralized in equal proportions. Lag-dominance is defined as the preferential localization or lateralization of the lagging source.

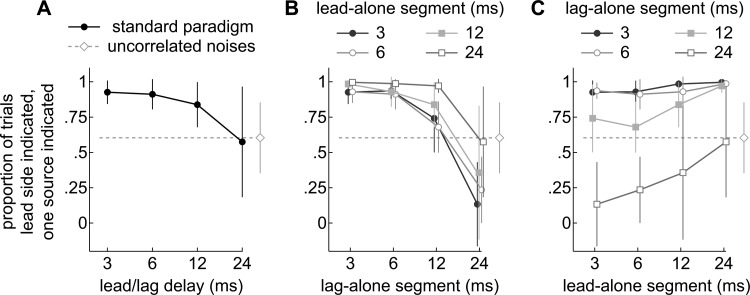

Figure 6.

(Color online) Proportions of trials when a single source was indicated on the leading or lagging sides of the top arc. Each marker indicates the averageacross subjects (±1 s.d.). A dashed line in each panel shows the average obtained when two 30 ms independent noises were presented. (a) Responses to lead/lag pairs under the standard paradigm, when the lead and lag-alone segments were of equal length (30 ms). Subjects tended to report the leading side at short delays (3 ms) and were more likely to indicate the lagging side as the delay increased. (b) Responses to lead/lag pairs with variable lead-alone segments (onset/ongoing delays). The abscissa indicates the length of the lag-alone segment. Reports of the leading side generally decreased with the duration of the lag-alone segment. (c) Responses are re-plotted to show the results of varying the lead-alone segment (abscissa) when the lag-alone segments were fixed at 3, 6, 12, or 24 ms. The proportions remained flat or even rose with the duration of the lead-alone segment (abscissa).

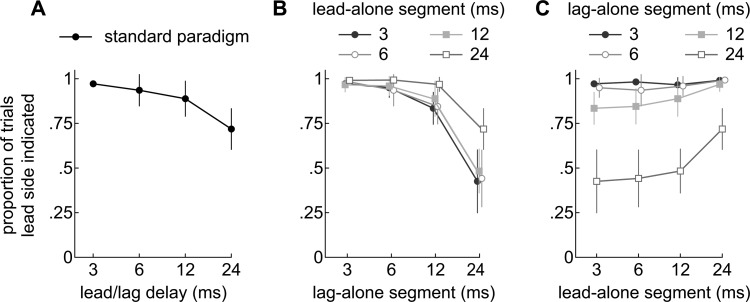

Figure 8.

(Color online) Proportions of trials in which subjects indicated the leading side of the single arc used for Experiment 2. (a) Responses to lead/lag pairs under the standard paradigm. Subjects almost never indicated the lagging side of the arc when the delay was short. The proportions decreased slightly when longer delays were tested, indicating that the lagging side was occasionally indicated. (b) Responses to lead/lag pairs when the lead-alone segment (onset delay) was fixed (3, 6 12, or 24 ms) and the lag-alone segment was varied (abscissa). (c) Responses are re-plotted to show the results of varying the lead-alone segment (abscissa) when the lag-alone segments were fixed at 3, 6, 12, or 24 ms. Interestingly, the leading side was reported more frequently as the lead-alone segment (onset/ongoing delay) was lengthened.

To quantify lead and lag-dominance, the proportion of trials in which listeners indicated a single, fused image on either the leading (azimuth > 0) or lagging (azimuth < 0) side of the top arc (Fig. 2) was measured. If lead-dominance is strong, listeners should report a single sound on the side of the leading source (proportions > 0.5). As lead-dominance weakens, listeners should increasingly report the single image to be on the side of the lagging source. When lag-dominance is strong, listeners should report a single sound on the side of the lagging source (proportions < 0.5).

Results from the standard paradigm are shown in Fig. 6a. When a single source was reported, it was nearly always reported on the leading side at short delays, suggesting strong lead-dominance. As the delay increased, listeners were as likely to indicate the lagging side, suggesting weak lead-dominance. No evidence of lag-dominance was observed under the standard paradigm. However, because listeners seldom reported a single source at long delays, the sample size is smaller and the variance is correspondingly higher, making it difficult to assess lag-dominance.

Figure 6b shows the results of varying the lag-alone segment (abscissa) on the lateralization of a single source. When the lag-alone segment was short (3, 6 ms), the tendency to report the leading side was high but decreased as the lag-alone segment was lengthened. In other words, the tendency to report the leading side seems to depend more on the duration of the lag-alone segment than on the onset/ongoing delays. This point can be seen more clearly in Fig. 6c which re-plots the data so that the effect of varying the onset/ongoing delay (abscissa) can be seen while holding the lag-alone segment at 3, 6, 12, and 24 ms. With the lag-alone segment held at 3 or 6 ms (circles), lead-dominance is practically complete and it is not possible to see the effect of lengthening the lead alone segment. Note that the nearly complete lead-dominance is maintained even when the lead-alone segment is shorter than the lag alone segment. This attests to the strength of the leading sound in biasing spatial perception. To view any effect of lengthening the lead-alone segment it is necessary to examine the responses obtained when the lag-alone segment is lengthened to 12 or 24 ms (squares) at which values lead-dominance is attenuated. Under these conditions, the proportion of trials in which the leading side was indicated remained rather flat or even rose as the lead-alone segment was lengthened. The average performance with independent noises is indicated in Fig. 6 by a dashed line. As expected, subjects indicated the lagging sides of the arcs as frequently as the leading sides (∼50%). Evidence for lead-dominance was therefore absent.

Figures 6b, 6c also show that when the lag-alone segment is lengthened to 24 ms, the lagging sound can dominate. As shown, the proportion of trials in which the single source is lateralized on the leading side falls below 50%, indicating that the single source is perceived to be more frequently on the lagging side. For example, when the lag-alone segment was 24 ms and the lead-alone segment was 3 or 6 ms, subjects were significantly more likely to indicate the lagging side of the top arc (23 of 29 trials; P = 0.03, pooled data, contingency table analysis). Note that neither source dominated when the lengths of both segments were equal and long (24 ms), as occurred under the standard paradigm.

Uncertainty

When listeners reported two sources, they occasionally lateralized them to the same sides on the top and bottom arcs, suggesting that they were uncertain about the laterality of one of the two sources. This could be related to the phenomenon of lag-discrimination suppression which refers to the observation that the lagging sound is sometimes difficult to localize. However, under certain experimental conditions, listeners in the present study appeared to have difficulty localizing the leading sound. To quantify this difficulty or “uncertainty” in lateralization, the proportion of trials in which listeners indicated the leading [(Figs. 7a, 7b, 7c] or lagging [Figs. 7d, 7e, 7f] sides of both arcs was measured.

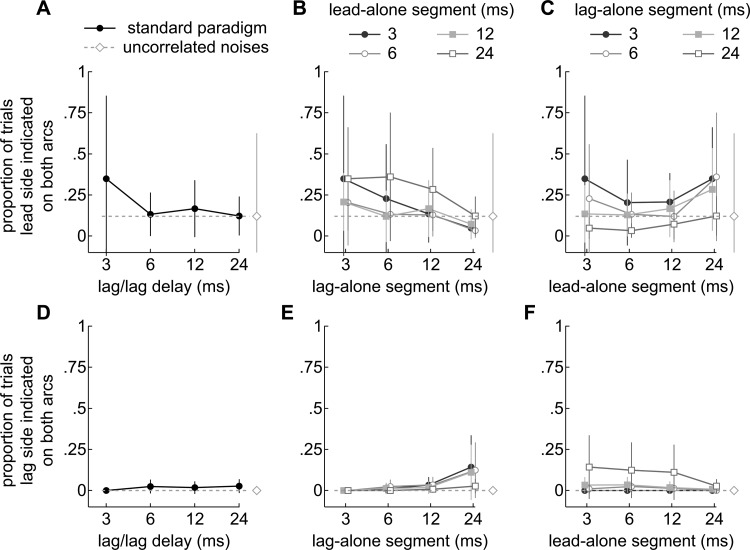

Figure 7.

(Color online) Proportions of trials when two sources were indicated on the same sides of both arcs. (a)–(c) Responses when both sources were indicted on the leading side. (d)–(f) Responses when both sources were indicted on the lagging side. A dashed line in each panel shows the average obtained when two 30 ms independent noises were presented. (a) Responses to lead/lag pairs under the standard paradigm, when the lead and lag-alone segments were of equal length (30 ms). Subjects tended to report the leading sides of both arcs at short delays (3 ms). (b) Responses to lead/lag pairs with variable lead-alone segments (onset/ongoing delays). The abscissa indicates the length of the lag-alone segment. Reports on the leading sides of both arcs generally decreased with the duration of the lag-alone segment. (c) Responses are re-plotted to show the results of varying the lead-alone segment (abscissa) when the lag-alone segments were fixed at 3, 6, 12, or 24 ms. The proportions remained relatively flat with the duration of the lead-alone segment or are opposite to those representing fusion in Fig. 5. (d) Responses under the standard paradigm. Subjects almost never reported the lagging sides of both arcs. (e) Responses to lead/lag pairs with variable lead-alone segments (onset/ongoing delays). The abscissa indicates the length of the lag-alone segment. Reports on the lagging sides of both arcs increased when the duration of the lag-alone segment was 24 ms. (f) Responses are re-plotted to show the results of varying the lead-alone segment (abscissa) when the lag-alone segments were fixed at 3, 6, 12, or 24 ms. Reports on the lagging sides of both arcs are seen to again increase when the duration of the lag-alone segment was 24 ms.

Results from the standard paradigm, when the leading sides of both arcs were indicated, are shown in Fig. 7a. The tendency to indicate the leading sides of both arcs, i.e., “lag-uncertainty,” was variable across subjects but greatest when the delay was short (3 ms). Under these conditions (3 ms delay), three subjects never indicated an additional source. Two subjects indicated the leading sides of both arcs in every trial that an additional source was indicated (4 of 4 and 2 of 2 trials, respectively). The remaining two subjects indicated additional sources in 36 trials but indicated the leading sides of both arcs only once (0 of 26 and 1of 10 trials, respectively). As the delay increased and fusion weakened, subjects frequently indicated an additional source (Fig. 5) but rarely indicated the leading sides of both arcs. A study of the precedence effect in 4–5 year old children (Litovsky and Godar, 2010) reported similar results in which a subject reported both sources to be on the leading side suggesting an uncertainty about the position of the lag.

Figure 7b shows the results of varying the lag-alone segment (abscissa). When the lag-alone segment was short (3, 6 ms), the tendency to report an additional source was low (Fig. 5) but the tendency to indicate the leading sides of both arcs was moderately high (∼25%). This tendency diminished as the lag-alone segment increased and an additional source was more frequently indicated. Thus, the tendency to report sources on the leading sides of both arcs, i.e., lag-uncertainty, seems to have depended more on the duration of the lag-alone segment than the onset/ongoing delay. This point can be seen more clearly in Fig. 7c which re-plots the data so that the effect of varying the onset/ongoing delay (abscissa) can be seen while holding the lag-alone segment at 3, 6, 12, and 24 ms. As shown, the psychometric functions are relatively flat for all lag-alone durations tested. Thus, the proportion of trials in which the leading sides of both arcs were indicated depended less on the onset/ongoing delays.

Interestingly, the shapes of these lag-uncertainty functions [Figs. 7a, 7b, 7c] are opposite to those in Fig. 5, which represent fusion. The listeners thus seem to have become less certain of the lagging source's location as the lag-alone segment was shortened and fusion strengthened.

Figures 7d, 7e, 7f plot the proportion of trials in which the subjects appeared to be uncertain about the leading sound's laterality, and marked the lagging sides of both arcs. Regardless of delay, the lagging sides of both arcs were rarely marked under the standard paradigm [Fig. 7d]. However, when the lag-alone segment was 24 ms, the tendency to report the lagging sides of both arcs, i.e., lead-uncertainty, increased at the shorter onset/ongoing delays (3, 6, or 12 ms). The increase is small (∼15%) but significant (P < 0.05; pooled data, contingency table analyses) because it corresponded to when the listeners nearly always indicated an additional source (Fig. 5). The increase is more apparent in Fig. 7e, which shows the results of varying the lag-alone segment (abscissa). The line that represents trials with a 24 ms lag-alone segment is above the others except for when the lead-alone segment was also 24 ms.

The shapes of these lead-uncertainty functions [Figs. 7e, 7f] do not reflect fusion (Fig. 5) but are opposite those shown in Figs. 6b, 6c, where evidence for lag-dominance was found when the lag-alone segment was 24 ms and the lead-alone segment was shorter (3, 6, or 12 ms). Thus, listeners seem to have become less certain of the leading source's location when the lead-alone segment was shorter than the lag-alone segment and the lagging source dominated perception.

Taken together, varying the length of the lag-alone segment was found to have had a strong influence on fusion (Fig. 5), lead-dominance (Fig. 6), and lag-uncertainty [Figs. 7a, 7b, 7c]. The presence of a long lag-alone segment (24 ms) also seems to have produced measureable levels of lag-dominance [Figs. 6b, 6c] and lead-uncertainty [Figs. 7e, 7f]. In contrast, the length of the lead-alone segment had only a subtle effect on these phenomena. For example, lengthening the lead-alone segment seems to have caused a small increase in fusion [Fig. 5b], slight strengthening of lead-dominance [Fig. 6b], and small increase in lag-uncertainty [Fig. 7b].

EXPERIMENT 3

An earlier study demonstrated that localization dominance need not end when fusion ends (Litovsky and Shinn-Cunningham, 2001). When two sources were reported in Experiment 2, the leading or lagging sounds could be marked on the top or bottom arcs due to temporal order confusion. The variances were therefore large and measures of localization dominance were difficult to compare [Figs. 6a, 6b, 6c].

To better evaluate localization dominance when listeners reported two sources, seven additional listeners (2 female, 5 male) were asked to indicate the centroid of the “clearest” auditory image on a single arc (top arc in Fig. 2). When the leading source dominates, subjects should indicate the leading side of the arc. When the lagging source dominates, subjects should indicate the lagging side. When neither source dominates, subjects should indicate both sides equally often.

Design

The stimuli were the same as in Experiment 2 [Figs. 1c, 1d]. Locations indicated on the arc were recorded and the proportion of trials in which subjects indicated the leading side of the arc (Fig. 2) as opposed to the lagging side was calculated across test sessions. Each stimulus [Figs. 1c and 1(d); n = 16] was presented 12 times per session, in random order, across 5 sessions for each subject (960 total trials). Before each trial (500 ms), listeners heard a diotic noise burst of variable length (33–54 ms) that provided a sense of the midline as a reference.

Results and discussion

The data are presented first for the standard paradigm [Fig. 8a]. The results are similar to those shown in Fig. 6a in that lead-dominance weakened with delay, but the variance is reduced for long delays.

Figure 8b shows the results of varying the lag-alone segment (abscissa) while the length of the lead-alone segment was held constant. The results are comparable to those shown in Fig. 6b except that the variance was, again, greatly reduced when the lag-alone segment was long. By and large, the tendency to indicate the leading source declines with the lag-alone segment, for all lead-alone segments tested. In other words, lead-dominance declines as the lag-alone segment is lengthened. Interestingly, the psychometric function representing data obtained with the longest lead-alone segment (24 ms) remains above the others. This suggests that lead-dominance is more resistant to the effects of the lag-alone segment when the lead-alone segment is long.

This point can be seen more clearly in Fig. 8c which re-plots the data so that the effect of varying the lead-alone segment (abscissa) can be seen while holding the lag-alone segment constant. It is evident that for a lag-alone segment of 24 ms and perhaps 12 ms, the tendency of listeners to indicate the leading sound rises as longer lead-alone segments are tested. This suggests, again, that lead-dominance strengthens as the lead-alone segment is lengthened.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

The objective of this study was to describe the contributions of the lead and lag-alone segments to lateralization when the leading and lagging sounds overlapped. When the contribution of the superposed segment was minimized, the lengths of the lead- and lag-alone segments were found to affect the spatial perception of the leading and lagging sounds, respectively. Extending the lead-alone segment, which extended the onset/ongoing delay and might be expected to diminish the leading sound's dominance, actually strengthened it. Similarly, extending the lag-alone segment caused the lagging sound to be reported even when the onset/ongoing delay was fixed at values that caused the leading sound to be reported almost exclusively under the standard paradigm.

The independent manipulation of the lead and lag-alone segments could be viewed as producing an unnatural stimulus. However, a comparable lag-alone segment could occur in nature when one or more reflections overlap the direct sound (e.g., 3 ms delay) and an additional reflection arrives after a substantially longer delay (e.g., 24 ms). The “lag-alone” segment that is produced under this scenario is unlikely to be identical to the corresponding segment of the leading source, which is obscured by the earlier reflections, but may be more similar than a reflection that arrives after a short delay. Thus, while the independent extension of the lag-alone segments, sometimes by the concatenation of unrelated noise, was an experimental manipulation, it led to observations that may be relevant to spatial hearing in more complex and naturalistic environments that create multiple echoes. It is, perhaps, more naturalistic than the standard paradigm which simulates a direct sound followed by a single reflection with equal amplitude. Indeed, the manner by which the lag-alone segment was lengthened did not influence the frequency with which an additional source was indicated [Figs. 5b, 5c; P > 0.05; pooled data].

Lead and lag independence

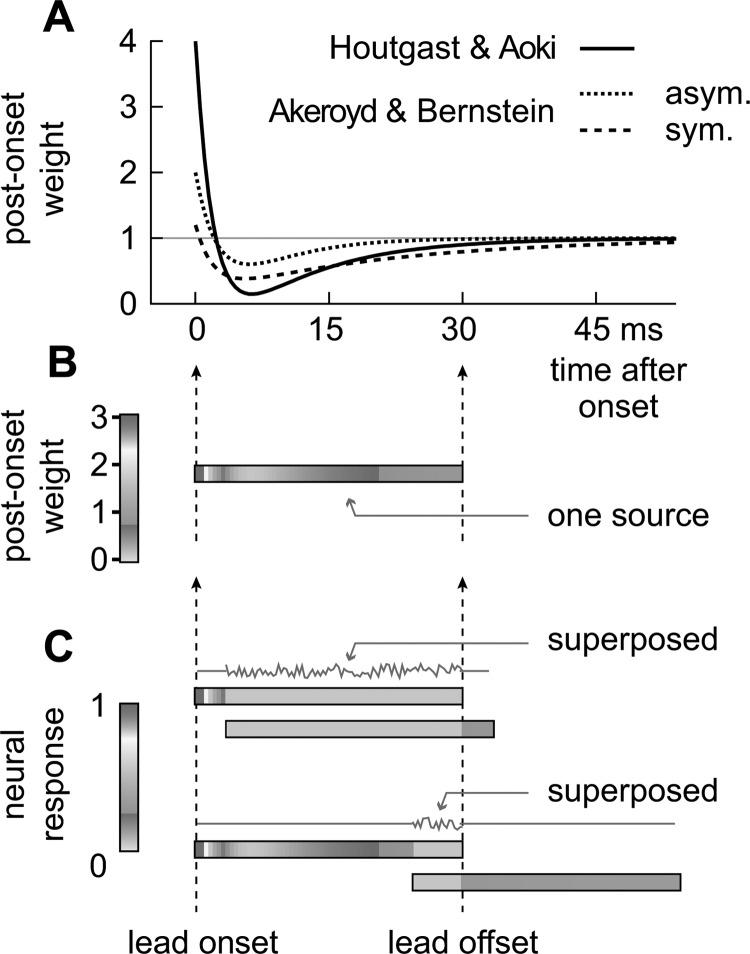

The observations reported above are consistent with the idea that neural responses to the sources of leading and lagging sounds are independent of one another. That is, neural responses evoked during the lead-alone segment do not affect those that are evoked during the lag-alone segment (or vice versa). This idea of independent neural representations, combined with earlier observations on the temporal variation in sensitivity to localization cues (e.g., Houtgast and Plomp, 1968; Zurek, 1980; Houtgast and Aoki, 1994; Freyman et al., 1997; Akeroyd and Bernstein, 2001), offers some insight to the results (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

(Color online) Sensitivity to spatial cues after a sound's onset. (a) Sensitivity functions estimated by Houtgast and Aoki (1994; f(t) = 5 e−t/2+ −2 e−t/10 + 1) and Akeroyd and Bernstein (2001; ITD asymmetric time window: f(t) = 3.1 e−t/2.8 + −2.1 e−t/5.9 + 1; ITD symmetric time window: f(t) = 1.1 e−t/2 + −2 e−t/20.3 + 1). (b) Single source shaded according to the sensitivity function described by Houtgast and Aoki (1994). Note that the function approaches a near steady state (value of 1 and white shade) after 30 ms and thus prior to the leading stimulus’ offset. (c) Lead/lag stimulus pairs (3or 24 ms delay, standard paradigm) shaded according to the probability of a neural response. Response probabilities parallel the sensitivity function described by Houtgast and Aoki (1994) but also show a decrease in response probability due to fluctuations of ITD during the superposed segment (thin gray lines).

Figure 9a plots sensitivity to sound localization cues (post-onset weight) against time after the onset of a stimulus from a single source obtained from human listeners by Houtgast and Aoki (solid line) and Akeroyd and Bernstein (broken lines). The latter estimated their functions using symmetrical (dashed) and asymmetrical (dotted) integration windows. Although obtained using different techniques, they all show a heightened sensitivity at the beginning of the sound, a brief loss of sensitivity, and then a recovery to a near steady-state level. Sensitivity, as determined by Houtgast and Aoki, is represented in Fig. 9b on a horizontal bar representing a sound from a single source. In Fig. 9c), an additional source was added after a 3 or 24 ms delay.

Above the bars in Fig. 9c are gray lines representing variation in ITD. At the sound's onset, when sensitivity is high, the ITDs are stable since there is only one source—the lead. During the superposed segment, the signals from the lead and lag sum and cause ITD to fluctuate (e.g., Snow, 1954; Takahashi and Keller, 1994; Blauert, 1997; Roman et al., 2003; Faller and Merimaa, 2004; Keller and Takahashi, 2005; Dizon and Colburn, 2006; Meffin and Grothe, 2009). At the lead's offset, the ITDs begin to stabilize once again but at the ITD of the lagging source. Note, however, that while the ITD is now stable, the sensitivity is not as high as it was at the onset.

The response properties of neurons in the IC (inferior colliculus), without which localization and the precedence effect in humans is impaired (Litovsky et al., 2002), suggest how this hypothetical mechanism might be implemented in the auditory system (Nelson and Takahashi, 2008). IC neurons in a variety of species are selective for ITD, and their firing typically begins with a burst of spikes at the stimulus’ onset, followed by a decline in spike probability to a near steady-state. Sensitivity to ITD may thus reflect the response properties of these neurons [Fig. 9c]. The leading sound is briefly present alone during the lead-alone segment, and thus consistently evokes at least one spike in neurons tuned to the lead's ITD. During the superposed segment, the probability of a spike declines considerably due to variation in ITD. When the leading sound ends, ITD stabilizes, and neurons representing the lag source are more likely to respond than they were during the superposed segment. However, because the leading sound caused ITD to vary at the lagging sound's onset, a greater overall response is evoked during the lead-alone segment than during the lag-alone segment. This could also explain why, in the standard paradigm, a short lead-alone segment causes lead dominance even though there is a lag-alone segment of equal length.

Role of inhibition

The dominance of the leading source at short delays is commonly attributed to a lateral-inhibitionlike process in which the neurons tuned for the location of the leading sound preempt the discharges of neurons tuned to the lagging sound's location (Lindemann, 1986; Yin, 1994; Fitzpatrick et al., 1995; Keller and Takahashi, 1996; Burger and Pollak, 2001; Spitzer et al., 2004; Pecka et al., 2007). The present explanations of the precedence effect, like those of Tollin (1998), Trahiotis and Hartung (2002), and those proposed for the owl (Nelson and Takahashi, 2008, 2010), do not require inhibition.

Physiological models involving inhibition, developed initially for clicks (e.g., Lindemann, 1986), have not been successfully generalized to lead/lag pairs that overlap explicitly in time. A direct comparison with models that do not invoke inhibition is therefore difficult. However, as indicated above, there are a number of psychoacoustical studies that have addressed the sensitivity of the auditory system to spatial cues at different times during an ongoing sound. These studies, although employing different methodologies, all describe a brief loss in sensitivity to spatial cues after a sound's onset (e.g., Houtgast and Plomp, 1968; Zurek, 1980; Houtgast and Aoki, 1994; Freyman et al., 1997; Akeroyd and Bernstein, 2001). This post-onset desensitization is illustrated in Fig. 9a.

The present results are inconsistent with the idea that post-onset desensitization prevents the lagging sound from being perceived as a spatially distinct auditory event. When the delay is only 3 ms [Fig. 9b, top), the lagging sound arrives while the auditory system is desensitized, and this can account for the usual observation that the lagging sound is not detected as a spatially separate event (note that the lag-alone segment is also 3 ms). At an onset delay of 24 ms, the auditory system should have recovered its sensitivity, allowing it to detect the lagging sound. However, in Experiment 2, listeners were unlikely to detect an additional source even with a lead-alone segment of 24 ms, as long as the lag-alone segment was short (3–6 ms). If anything, a long lead-alone segment tended to enhance the perception of the leading sound, not of the lagging sound. Thus, the clarity of the leading sound's image and the ability of listeners to lateralize the lagging sound seem to depend on the lengths of the lead and lag-alone segments, respectively.

The sensitivity profiles in Fig. 9 are illustrated as being independent of stimulus duration. Another possibility is that inhibition is continuously renewed throughout the lead-alone and superposed segments and persists for a brief period after the leading sound's offset. Lengthening the lag-alone segment, it may be argued, simply allows the lagging sound to outlast the persistent inhibition. The present data cannot exclude this hypothesis. However, measurements of fusion when the delay was short (3 ms) are similar to those obtained with two independent noises [30 ms; dashed lines in Fig. 5a]. In other words, the listeners’ responses can be accounted for by the presence of two sources without recourse to inhibition.

Role of the superposed segment

In order to study the “alone” segments independently of the superposed segment, the latter segment was shortened so that its contribution to precedence phenomena was minimal. This is shown explicitly in Experiment 1. Results from Experiments 2 and 3 further suggest that the superposed segment contributed little to precedence phenomena. This is because the duration of the superposed segment, which is the difference between the leading sound's duration (30 ms) and that of the lead-alone segment, increased as the lead-alone segment was shortened. Ongoing delays in the superposed segment were also the shortest when the lead-alone segment was short (3 ms). Results from Experiment 1 notwithstanding, if the superposed segment's contribution had been significant, one would have expected listeners to experience fusion and lead-dominance most frequently when the lead-alone segment was 3 ms (superposed segment = 27 ms; ongoing delays = 3 ms) and least frequently when the lead-alone segment was 24 ms (superposed segment = 3 ms; ongoing delays = 24 ms). Instead, the subjects’ responses better reflect the length of the lag-alone segment and, if anything, have the opposite trend when the lead-alone segment was varied and the lag-alone segment was held constant [Figs. 6c8c]. The superposed segment thus appears to have contributed less to precedence phenomena than the periods of time when one sound or the other was present by itself.

The interpretation offered above has a basis in acoustics. When there is only one sound in the environment, as there is during the lead and lag-alone segments, all the frequency-specific binaural cues assume values that correspond to those generated at that sound-source’s location, and they remain at those values for the sound's duration. For the stimuli used in the present study, the ITD should be constant ( ± 250 μs) across frequencies and remain at those values for the duration of the lead and lag-alone segments. The auditory image based on these cues should be spatially coherent and stable. By contrast, when there are two concurrent sounds with overlapping spectra, as there are during the superposed segment, the frequency-specific binaural cues are likely to fluctuate over time, fleetingly achieving values that correspond to one sound-source’s position during moments when the amplitude of that source is higher than the other (e.g., Snow, 1954; Takahashi and Keller, 1994; Blauert, 1997; Roman et al., 2003; Faller and Merimaa, 2004; Keller and Takahashi, 2005; Dizon and Colburn, 2006; Meffin and Grothe, 2009). Thus, the binaural cues are expected to be less spatially coherent and stable during the superposed segment than during the lead and lag-alone segments.

The relatively weak contribution from the superposed segment for the 30 ms stimuli are at odds with those of Zurek (1980) and of Dizon and Colburn (2006) who also presented stimulus pairs having synchronized onsets and offsets. Results similar to these previous studies were obtained in Experiment 1, however, when the stimuli were lengthened to 200 ms. Thus, the discrepancy appears to be attributable to the use of ongoing delays longer than 3 ms and stimuli that are considerably longer than “clicks” but shorter than 30 ms.

The effect of delay and duration may be related to the accumulation of binaural information over time, as suggested above for the lead and lag-alone segments. Hafter and colleagues, using a periodic train of transients or periodically modulated sounds, for example, showed that each transient contributes an equal amount of information when they are separated by more than 10 ms (Hafter and Dye, 1983; Hafter et al., 1983; Buell and Hafter, 1988; Stecker and Hafter, 2002). Thus, stimuli longer than 30 ms may have allowed for the accumulation of more information during the superposed segment. Had a longer superposed segment been used, the contributions of the lead- and lag-alone segments could have been diminished.

Role of the lead-alone segment

The presence of a lead-alone segment (onset delay) always caused listeners to localize the leading source. Neither temporal order confusion (Experiment 2) nor occasional instances of lag-dominance, for example, seem to have caused the leading source's image to vanish. If anything, lengthening the lead-alone segment caused a slight strengthening of both fusion and lead-dominance.

This interpretation of the present data has parallels in studies using brief transients, such as clicks, which represent the bulk of the stimuli used in studies of the precedence effect. Although clicks have an apparent advantage of avoiding the temporal overlap of the leading and lagging stimuli, the peripheral auditory filters ring, lengthening the internal signals, and causing the lead/lag pair to overlap in time for short delays or in low-frequency channels (Hartung and Trahiotis, 2001; Trahiotis and Hartung, 2002). It is therefore possible to define lead-alone, lag-alone, and superposed segments in the internal signals. During the internal superposed segment, the binaural cues fluctuate over time and across frequency channels (Hartung and Trahiotis, 2001; Trahiotis and Hartung, 2002), as they do during the superposed segment in the stimuli used in the present study. Hartung and Trahiotis (2001) demonstrated that the dominance of the leading sound can be explained by the combination of the ringing peripheral filters and a model of the hair cell (Meddis et al., 1990). The hair cell response, which is crucial to the model's success in predicting psychoacoustical observations, is strong at the onset and declines to a steady state as the ringing continues (Meddis, 1986). The hair cell's temporal response profile, like that of neurons in the owl's space map, may thus emphasize the internal lead-alone segment, during which the frequency-specific binaural cues are coherent and stable.

This interpretation is also consistent with the results of Devore et al. (2009) who demonstrated that under reverberant conditions, human listeners can localize sounds relatively accurately by making use of the earliest portion of the signal before reflections arrive.

CONCLUSIONS

The durations of the lead-alone, lag-alone, and superposed segments were manipulated to determine their contributions to spatial hearing in the presence of a single simulated echo. Results suggest that human listeners perceive the lagging sound as a spatially distinct event not when the delay between the onsets of the lead/lag pair increases, but when the lag-alone segment is lengthened. By the same token, lengthening the lead-alone segment, which is equivalent to increasing the onset delay, did not affect the perception of the lagging sound, but instead, increased the spatial “clarity” of the leading sound. Although some cues regarding each stimulus were also available in the superposed segment, listeners treated the two sounds as though they were statistically independent.

These observations are consistent with the idea that during spatial tasks, the auditory system is influenced most heavily by epochs when spatial cues are stable. Stability is maximal during the lead-alone and lag-alone segments when there is but a single sound. The lengths of these segments determine whether the leading sound or both sounds are reported. These segments, however, are not necessarily equally weighted. When the lead- and lag-alone segments are both short (<6 ms), the leading sound dominates perception, not necessarily because the responses to the lagging sound are somehow suppressed in the auditory pathways, but because the auditory system is highly sensitive to sound onsets, which only the leading sound contains. Finally, the superposed segment can also contribute to spatial perception, but because spatial cues are less stable when there are two concomitant sounds instead of one, a longer stimulus (200 ms) may be required to extract this spatial information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported in part by the University of Oregon Academic Support Account; the present experiments are also based on prior work in the owl supported by grants from the NIDCD: Grant No. F32-DC008267 to B.S.N. and Grant No. R01-DC003925. We thank Dr. Kathleen Roberts (Director, Communication Disorders & Sciences, University of Oregon) for giving us access to audiometric booths and Dr. C. H. Keller for helpful discussions.

References

- Akeroyd, M. A., and Bernstein, L. R. (2001). “ The variation across time of sensitivity to interaural disparities: Behavioral measurements and quantitative analyses,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 110, 2516–2526. 10.1121/1.1412442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blauert, J. (1997). Spatial Hearing: The Psychophysics of Human Sound Localization, revised ed. (The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA: ). [Google Scholar]

- Blauert, J., and Lindemann, W. (1986). “ Spatial mapping of intracranial auditory events for various degrees of interaural coherence,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 79, 806–813. 10.1121/1.393471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buell, T. N., and Hafter, E. R. (1988). “ Discrimination of interaural differences of time in the envelopes of high-frequency signals: Integration times,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 84, 2063–2066. 10.1121/1.397050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger, M. R., and Pollak, G. D. (2001). “ Reversible inactivation of the dorsal nucleus of the lateral lemniscus reveals its role in the processing of multiple sound sources in the inferior colliculus of bats,” J. Neurosci. 21, 4830–4843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devore, S., Ihlefeld, A., Hancock, K., Shinn-Cunningham, B., and Delgutte, B. (2009). “ Accurate sound localization in reverberant environments is mediated by robust encoding of spatial cues in the auditory midbrain,” Neuron 62, 123–134. 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.02.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dizon, M. M., and Colburn, S. H. (2006). “ The influence of spectral, temporal, and interaural stimulus variations on the precedence effect,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 119, 2947–2964. 10.1121/1.2189451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faller, C., and Merimaa, J. (2004). “ Source localization in complex listening situations: Selection of binaural cues based on interaural coherence,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 116, 3075–3089. 10.1121/1.1791872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick, D. C., Kuwada, S., Batra, R., and Trahiotis, C. (1995). “ Neural responses to simple simulated echoes in the auditory brain stem of the unanesthetized rabbit,” J. Neurophysiol. 74, 2469–2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freyman, R. L., Zurek, P. M., Balakrishnan, U., and Chiang, Y.-C. (1997). “ Onset dominance in lateralization,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 101, 1649–1659. 10.1121/1.418149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goupell, M. J., Yu, G., and Litovsky, R. Y. (2012). “ The effect of an additional reflection in a precedence effect experiment,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 131, 2958–2967. 10.1121/1.3689849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas, H. (1951). “ Uber den einfluss eines einfachechos auf die horsamkeit von sprache (On the influence of a single echo on the intelligibility of speech),” Acustica 1, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hafter, E. R., and Dye, R. H. J. (1983). “ Detection of interaural differences of time in trains of high-frequency clicks as a function of interclick interval and number,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 73, 644–651. 10.1121/1.388956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafter, E. R., Dye, R. H. J., and Wenzel, E. (1983). “ Detection of interaural differences of intensity in trains of high-frequency clicks as a function of interclick interval and number,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 73, 1708–1713. 10.1121/1.389394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, G. G., Flanagan, J. L., and Watson, B. J. (1963). “ Binaural interaction of a click with a click pair,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 35, 672–678. 10.1121/1.1918583 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hartung, K., and Trahiotis, C. (2001). “ Peripheral auditory processing and investigations of the ‘precedence effect’ which utilize successive transient stimuli,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 110, 1505–1513. 10.1121/1.1390339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtgast, T., and Aoki, S. (1994). “ Stimulus-onset dominance in the perception of binaural information,” Hear. Res. 72, 29–36. 10.1016/0378-5955(94)90202-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtgast, T., and Plomp, R. (1968). “ Lateralization threshold of a signal in noise,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 44, 807–812. 10.1121/1.1911178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller, C. H., and Takahashi, T. T. (1996). “ Responses to simulated echoes by neurons in the barn owl's auditory space map,” J. Comp. Physiol., A 178, 499–512. 10.1007/BF00190180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller, C. H., and Takahashi, T. T. (2005). “ Localization and identification of concurrent sounds in the owl's auditory space map,” J. Neurosci. 25, 10446–10461. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2093-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann, W. (1986). “ Extension of a binaural cross-correlation model by contralateral inhibition. I. Simulation of lateralization for stationary signals,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 80, 1608–1622. 10.1121/1.394325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litovsky, R. Y., Colburn, H. S., Yost, W. A., and Guzman, S. J. (1999). “ The precedence effect,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 106, 1633–1654. 10.1121/1.427914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litovsky, R. Y., Fligor, B. J., and Tramo, M. J. (2002). “ Functional role of the human inferior colliculus in binaural hearing,” Hear. Res. 165, 177–188. 10.1016/S0378-5955(02)00304-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litovsky, R. Y., and Godar, S. P. (2010). “ Difference in precedence effect between children and adults signifies development of sound localization abilities in complex listening tasks,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 128, 1979–1991. 10.1121/1.3478849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litovsky, R. Y., and Shinn-Cunningham, B. (2001). “ Investigation of the relationship among three common measures of precedence: Fusion, localization dominance, and discrimination suppression,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 109, 346–358. 10.1121/1.1328792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden, D. (1973). “ Precedence effects and auditory cells with long characteristic delays,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 54, 528–530. 10.1121/1.1913611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meddis, R. (1986). “ Simulation of mechanical to neural transduction in the auditory receptor,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 79, 702–711. 10.1121/1.393460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meddis, R., Hewitt, M. J., and Shackleton, T. M. (1990). “ Implementation details of a computational model of the inner hair-cell auditory-nerve synapse,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 87, 1813–1816. 10.1121/1.399379 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meffin, H., and Grothe, B. (2009). “ Selective filtering to spurious localization cues in the mammalian auditory brainstem,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 126, 2437–2454. 10.1121/1.3238239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, B. S., and Takahashi, T. T. (2008). “Independence of echo-threshold and echo-delay in the barn owl,” PLoS ONE, 3(10), e3598. 10.1371/journal.pone.0003598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, B. S., and Takahashi, T. T. (2010). “ Spatial hearing in echoic environments: The role of the envelope in owls,” Neuron 67, 643–655. 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecka, M., Zahn, T. P., Saunier-Rebori, B., Siveke, I., Felmy, F., Wiegrebe, L., Klug, A., Pollak, G. D., and Grothe, B. (2007). “ Inhibiting the inhibition: A neuronal network for sound localization in reverberant environments,” J. Neurosci. 27, 1782–1790. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5335-06.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman, N., Wang, D., and Brown, G. J. (2003). “ Speech segregation based on sound localization,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 114, 2236–2252. 10.1121/1.1610463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow, W. B. (1954). “ The effects of arrival time on stereophonic localization,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 26, 1071–1074. 10.1121/1.1907451 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer, M. W., Bala, A. D. S., and Takahashi, T. T. (2004). “ A neuronal correlate of the precedence effect is associated with spatial selectivity in the barn owl's auditory midbrain,” J. Neurophysiol. 92, 2051–2070. 10.1152/jn.01235.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecker, C. G., and Hafter, E. R. (2002). “ Temporal weighting in sound localization,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 112, 1046–1057. 10.1121/1.1497366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellmack, M. A., Dye, R. H., and Guzman, S. J. (1999). “ Observer weighting of interaural delays in source and echo clicks,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 105, 377–387. 10.1121/1.424555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, T. T., and Keller, C. H. (1994). “ Representation of multiple sound sources in the owl's auditory space map,” J. Neurosci. 14, 4780–4793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollin, D. J. (1998). “ Computational model of the lateralisation of clicks and their echoes,” in Proceedings of the NATO Advanced Study Institute on Computational Hearing, edited by Greenberg S. and Slaney M. (NATO Scientific and Environmental Affairs Division, Il Ciocco: ), pp. 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Trahiotis, C., and Hartung, K. (2002). “ Peripheral auditory processing, the precedence effect and responses of single units in the inferior colliculus,” Hear. Res. 168, 55–59. 10.1016/S0378-5955(02)00357-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallach, H., Newman, E. B., and Rosenzweig, M. R. (1949). “ The precedence effect in sound localization,” Am. J. Psychol. 57, 315–336. 10.2307/1418275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin, T. C. (1994). “ Physiological correlates of the precedence effect and summing localization in the inferior colliculus of the cat,” J. Neurosci. 14, 5170–5186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurek, P. M. (1980). “ The precedence effect and its possible role in the avoidance of interaural ambiguities,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 67, 952–964. 10.1121/1.383974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]