Abstract

Few studies have evaluated the cardiovascular-related effects of indoor biomass burning or the role of characteristics such as age and obesity status, in this relationship. We examined the impact of a cleaner-burning cookstove intervention on blood pressure among Nicaraguan women using an open fire at baseline; we also evaluated heterogeneity of the impact by subgroups of the population. We evaluated changes in systolic and diastolic blood pressure from baseline to post-intervention (range: 273–383 days) among 74 female cooks. We measured indoor fine particulate matter (PM2.5; n=25), indoor carbon monoxide (CO; n=32), and personal CO (n=30) concentrations. Large mean reductions in pollutant concentrations were observed for all pollutants; for example, indoor PM2.5 was reduced 77% following the intervention. However, pollution distributions (baseline and post-intervention) were wide and overlapping. Although substantial reductions in blood pressure were not observed among the entire population, a 5.9 mmHg reduction (95% confidence interval [CI]: −11.3, −0.4) in systolic blood pressure was observed among women 40 or more years of age and a 4.6 mmHg reduction (95% CI: −10.0, 0.8) was observed among obese women. Results from this study provide an indication that certain subgroups may be more likely to experience improvements in blood pressure following a cookstove intervention.

Keywords: Biomass, Household air pollution, Cookstoves, Blood pressure, Intervention, Nicaragua

Introduction

Nearly three billion of the world’s poorest people rely on solid fuel combustion (wood, coal, animal dung, etc.) to meet basic domestic energy needs (Rehfuess et al., 2006; Martin et al., 2011). Many of these households use traditional, inefficient and poorly vented indoor cookstoves to meet these needs, which can result in extremely high household air pollution concentrations. Indoor air pollution ranks 10th among preventable risk factors contributing to the global burden of disease, and it is the 6th leading risk factor for death in low-income countries (Narayan et al., 2010). More efficient cookstove designs have the potential to reduce pollutant emissions and household air pollution exposures substantially (Albalak et al., 2001; Bruce et al., 2004; Ezzati and Kammen, 2002; Naeher et al., 2000b; Smith, 2002). However, assessments of stove interventions incorporating health impacts are limited (McCracken et al., 2007; Romieu et al., 2009; Smith-Sivertsen et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2011), and few studies have evaluated the cardiovascular effects of indoor biomass burning (McCracken et al., 2007; Smith and Peel, 2010; McCracken et al., 2011; Baumgartner et al., 2011; Clark et al., 2011). Although cardiovascular disease has received relatively little attention in developing countries, it is the leading cause of death in Nicaragua (PAHO, 2007). Blood pressure is an ideal endpoint to assess the subclinical cardiovascular effects of household air pollution from biomass combustion; blood pressure is an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease (Lewington et al., 2002; Vasan et al., 2001), has an established relationship with ambient air pollution (Urch et al., 2005; Kannan et al., 2010), can change meaningfully over a short period of time (Turnbull, 2003), and can easily be measured in rural areas of developing countries.

Cross-sectional associations between elevated blood pressure and increased air pollution exposures from indoor biomass combustion have been reported (Baumgartner et al., 2011; Clark et al., 2011). McCracken et al. (2007) were the first to report blood pressure reductions following a chimney stove intervention. Small within-subject reductions in systolic and diastolic blood pressure were observed an average of 63 days (range, 0–342 days) after the stove intervention (McCracken et al., 2007). Whether longer follow-up periods would result in larger blood pressure reductions is unknown.

In addition to population-level effects, investigators have noted the importance of considering population subgroup susceptibility (e.g., socio-economic status, education, race, and underlying disease) when evaluating the potential health benefits associated with air pollution reductions (Levy et al., 2002; Tonne et al., 2008). For example, since stronger relationships between air pollution exposures and adverse health exist for certain subgroups, including for older age groups and obese populations (Sacks et al., 2011), then one could hypothesize that these subgroups would also experience greater benefits from an intervention that reduces these exposures (Levy et al., 2002). Although previous studies focused primarily on industry or traffic-related ambient air pollution reductions (Levy et al., 2002; Tonne et al., 2008), similar hypotheses regarding household air pollution interventions are plausible. No one, to date, has examined the effects of a cookstove intervention on blood pressure changes among population subgroups that may be particularly susceptible to the adverse effects of air pollution and therefore may benefit the most from an intervention to decrease air pollution exposure.

We conducted a longitudinal study to assess the health impact of a cookstove intervention among primary female cooks in a semi-rural community outside of Granada, Nicaragua. We previously reported results from a cross-sectional analysis of household air pollution concentrations and health assessed during the baseline year when all participants used a traditional, open-fire cookstove (Clark et al., 2011). Non-significant elevations in systolic blood pressure were associated with higher indoor carbon monoxide (CO) concentrations; these associations were stronger among obese participants (Clark et al., 2011). Here, we report the longitudinal changes in systolic and diastolic blood pressure from baseline to approximately one year following the introduction of a wood-burning cookstove with a more efficient combustion chamber and a chimney (referred to as the Eco-stove). We hypothesized that systolic and diastolic blood pressure would be reduced among participants following the introduction of the Eco-stove and that certain subgroups of the population would experience greater reductions in blood pressure following the intervention.

Methods

Study population

As described previously (Clark et al., 2011), community volunteers associated with a local women’s organization (Casa de la Mujer; Granada, Nicaragua) identified 124 nonsmoking female primary cooks (i.e., the person cooking the majority of meals) in El Fortin, Nicaragua, who had semi-enclosed (2–3 walls) or enclosed (4 walls) kitchen areas, cooked with traditional open-fire cookstoves, and agreed to purchase a subsidized Eco-stove (described below) after baseline health and exposure assessments. Although this was a non-random sample, volunteers indicated that very few, if any, eligible women in the community refused participation. Baseline field data collection was conducted from May to July 2008. Sample collection days occurred Monday through Saturday, which are typically similar in regards to cooking practices and general community activities. Participating families received the Eco-stoves following baseline assessments (between June and September 2008). Follow-up health and exposure measures were collected from May to June 2009, approximately 9 months to 1 year (range: 273 to 383 days) after Eco-stove introduction. Of the 121 participants providing valid blood pressure measures during baseline, subjects were excluded from this analysis due to inability to contact (n=12), pregnancy (n=13), no longer the primary cook of the household (n=12), a shift in body mass index (BMI) greater than 4 kg/m2 (n=5), and self-reported blood pressure medication use (n=5), leaving a total of 74 participants for this analysis. Due to feasibility reasons the study design did not incorporate a control arm (all participating families received an Eco-stove).

Exposure assessment

The exposure of interest for the primary analysis was the Eco-stove intervention. During baseline, all participants used a traditional open-fire cookstove. Traditional stoves generally consisted of homemade, elevated, open-combustion areas without chimneys, typically in a kitchen structure with two to four walls detached from the main living area. The stove model for the intervention was the Eco-stove (PROLENA, Managua, Nicaragua). The Eco-stove consists of an enclosed elbow-shaped combustion chamber surrounded by insulation and a metal encasing, a griddle (plancha) stove top, and a chimney. Materials used in the construction of the Eco-stove cost approximately $120 US; participants in the study paid $1.50 US (an amount determined feasible by the local women’s organization).

Woodsmoke contains numerous harmful pollutants; particulate matter and CO are typically used as markers of woodsmoke combustion (Naeher et al., 2007). Indoor PM2.5 [particulate matter less than 2.5 micrometers in diameter], indoor CO, and personal CO concentrations were measured during baseline and follow-up for a small subset of the population (among those with baseline and follow-up blood pressure measures, n=25 for PM2.5, n=32 for indoor CO, and n=30 for personal CO). Although exposure monitoring during the follow-up year was conducted among the entire population, only a subsample is presented here due to the theft of several study laptops upon completion of data collection. Indoor monitors were collocated inside the kitchen at a height representative of breathing zones; baseline kitchen/monitor sketches (including height and distance from stove) were used to place equipment at the same location during the follow-up monitoring period. As described in detail previously (Clark et al., 2011), concentrations of indoor PM2.5 and indoor and personal CO were assessed continuously over 48 hours using the UCB Particle Monitor (Berkeley Air Monitoring Group; Berkeley, CA, USA) and the Drager Pac 7000 (SKC, Inc; Eighty Four, PA, USA), respectively. The Drager Pac 7000s were pre- and post-calibrated using 50 ppm CO calibration gas; post-study calibration readings were within ten percent of the pre-calibration readings. Time-weighted average concentrations were calculated.

Health, demographic, and stove use measures

All health measurements were obtained at the end of the 48-hour pollutant monitoring period. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure measurements were taken manually (ausculatory method with aneroid sphygmomanometers) between the hours of 8am and 12pm after the participant had been seated and at rest for 10 minutes. Three repeat measures were taken within a 10-minute period of continued rest. When a series of measures are taken, the first is typically the highest (Pickering et al., 2005); therefore, we used the average of the second and third measures in analyses. A survey was administered to collect demographic information, education, occupation, exposure to secondhand smoke (at least occasional exposure in the kitchen or living area), and stove use/cooking practices during the follow-up year. Studies in Guatemala have examined culturally-appropriate indicators of socioeconomic status, including an asset index incorporating the possession of a radio, a television, and/or a bicycle, as well as owning pigs or cattle (Bruce et al., 1998; McCracken et al., 2007). We included similar indicators of socioeconomic status, along with education level, in the survey. Additionally, each participant’s height, weight, and waist circumference were measured. BMI was calculated as the weight divided by the squared height (in kg/m2); obesity was defined as BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2.

Statistical analysis

All data analyses were conducted using the SAS computer program (SAS 9.3, SAS Institute; Cary, NC, USA). Descriptive statistics were calculated for air pollutant concentrations, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and participant characteristics. Box-plots were created to evaluate pollutant concentration distributions (untransformed) by year. Baseline and follow-up pollutant concentrations were compared using paired t-tests (the assumption of normality was evaluated and met for the difference between the baseline and follow-up concentrations for the entire study population; natural log transformations were used when evaluating differences in baseline pollution concentrations among subgroups because distributions were not normal).

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure means were analyzed separately. Paired t-tests were used to evaluate the difference of the follow-up and baseline blood pressure levels for the entire study population (the assumption of normality was met for the paired t-test; the paired differences were independent of each other). A variable representing the change from baseline (prior to the stove introduction) to follow-up (post-introduction of the Eco-stove) was created for each subject by subtracting the baseline blood pressure level from the follow-up blood pressure level (therefore, a negative change in blood pressure indicated that blood pressure was reduced over the course of the study period). To assess heterogeneity of changes in blood pressure within subgroups of the population, we calculated least-squares means (and 95% confidence intervals [CI]) for the change in blood pressure within subgroups as well as p-values comparing the subgroup mean changes using Proc GLM (p-value <0.05 indicates that the subgroup mean changes were statistically different). For example, mean changes from pre- to post-intervention were compared within obese and non-obese subjects, and these mean changes were also compared between the obese and non-obese subjects (i.e., did obese and non-obese participants experience different changes in blood pressure?). Subgroups were defined a priori based on obesity status (BMI>= 30 kg/m2 vs. BMI < 30 kg/m2), any reported usual exposure to secondhand smoke in the home (yes vs. no), self-reported doctor-diagnosed heart disease (yes vs. no), years of education (0 [reference], 1–5, ≥6 years), indicators of socioeconomic status, and age at baseline. Age at baseline was categorized using approximate tertiles and was also dichotomized at 50 years due to evidence of effect modification reported by Baumgartner et al. (2011). All assumptions were evaluated and met (linearity, homoscedasticity, normality of the residuals, and independence of the observations [the mean differences from baseline to follow-up]).

Several sensitivity analyses were conducted separately to evaluate the robustness of results. We repeated analyses including the 5 participants reporting blood pressure medication use. Additionally, we excluded 10 women who previously smoked (n=3 reported smoking for more than one year and n=4 reported smoking more than 2 cigarettes/day, on average). Finally, due to the presence of primary female cook participants who were relatively young, we conducted an additional sensitivity analysis removing those participants less than 18 years of age (n=10).

Because some subgroups evaluated may contain similar populations, we performed Pearson Chi-square tests for independence to aid interpretation of main subgroup analyses (e.g., older participants may also likely be the obese participants).

Results

Among the population with blood pressure measures in the baseline and follow-up year and not reporting blood pressure medication use (n=74), mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure at baseline were 120.2 mmHg (standard deviation [SD], 21.3) and 75.2 mmHg (SD, 11.6), respectively (Table 1). The average age at baseline was 35.4 years, 38% (n=28) were obese, 41% (n=30) reported at least some exposure to secondhand smoke in the home, 14% (n=10) reported doctor-diagnosed heart disease, and 38% (n=28) reported 0 years of education (Table 1). Additionally, nearly half (47%) reported still using their traditional cookstove (i.e., solely or in conjunction with their Eco-stove) during the follow-up year. When asked to specify the average number of meals cooked per week with each stove type, 24% (n=18) reported using the traditional cookstove at least 25% of the time. Although 42 women participating during baseline were lost to follow-up or removed from analyses for reasons described above, demographic characteristics were similar and the means for baseline systolic and diastolic blood pressure did not differ between those in the current analysis (n=79, including those taking blood pressure medications) and those lost or removed after baseline (n=42) (p=0.90 and 0.99, respectively).

Table 1.

Baseline population characteristics among nonsmoking primary cooks in households using traditional, open-fire cookstoves in Nicaragua (n=74).

| Population Characteristic | Mean ± SD; range/N (%) |

|---|---|

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 120.2 ± 21.3; 95.0–202.5 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 75.2 ± 11.6; 57.0–110.5 |

| Age (years) | 35.4 ± 15.4; 11–80 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.8 ± 7.1; 14.0–54.9 |

| Obese | 28 (37.8) |

| Secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure (in any part of the home)a | 30 (40.5) |

| Doctor-diagnosed Heart diseasea,c | 10 (13.7) |

| Education categoryc | |

| 0 years | 28 (38.4) |

| 1–5 years | 25 (34.3) |

| 6+ years | 20 (27.4) |

| Owns a pigb,c | 20 (27.4) |

| Owns a chickenb,c | 52 (71.2) |

| Owns a televisionb,c | 70 (95.9) |

| Owns a radiob,c | 63 (86.3) |

Includes participants that reported factor in the follow-up year survey but not in the baseline survey (n=4, SHS; n=4, doctor-diagnosed heart disease)

Assessed in the follow-up year survey

N=73 (with complete survey information)

SD, standard deviation

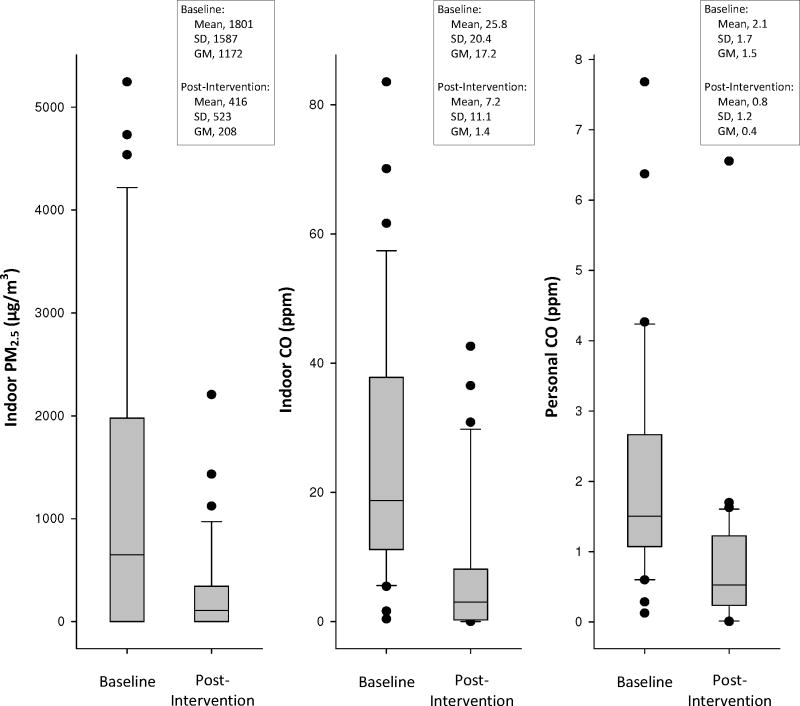

Although the subsample of the population with follow-up (post-intervention) exposure measurements was not a random subsample, there were no meaningful differences in baseline pollution concentrations, blood pressure, or demographic factors when comparing those with to those without post-intervention exposure measurements (results not presented). Large mean reductions in indoor PM2.5, indoor CO, and personal CO pollutant concentrations were observed from baseline to follow-up (p < 0.001 for all pollutants) (Figure 1). Mean 48-hour concentrations were reduced from 1801 μg/m3 to 416 μg/m3 for PM2.5 (n=25), 25.8 ppm to 7.2 ppm for indoor CO (n=32), and 2.1 ppm to 0.8 ppm for personal CO (n=30). However, as demonstrated in Figure 1, large overlap in distributions was observed between pollutant concentrations at baseline and follow-up. Additionally, when evaluating changes in mean pollutant concentrations across subgroups of the population (i.e., by obesity status, age categories, reported stove use) we observed that all subgroups experienced similar mean decreases in pollutant concentrations and did not differ statistically. For example, those reporting only the use of the Eco-stove during the follow-up year did not experience greater exposure reductions as compared to those reporting mixed stove use during the follow-up year (use of the traditional stove either solely or in conjunction with the Eco-stove) for PM2.5 (p=0.94), indoor CO (p=0.57), or personal CO (p=0.22). For PM2.5, those reporting sole use of the Eco-stove during follow-up experienced a 1363 μg/m3 reduction (95% CI: −2209, −517) while those reporting mixed use experienced a 1406 μg/m3 reduction (95% CI: −2219, −593). Similar patterns were observed for indoor and personal CO.

Figure 1.

Pollutant concentration distributions at baseline and post-intervention (for indoor PM2.5, n=25; for indoor CO, n=32; for personal CO, n=30). SD, standard deviation; GM, geometric mean; GSD, geometric standard deviation; the lower boundary of the box (closest to zero) indicates the 25th percentile, a line within the box marks the median, and the upper boundary of the box (farthest from zero) indicates the 75th percentile. Error bars above and below the box indicatethe 90th and 10th percentiles.

On average, systolic and diastolic blood pressure did not change substantially from baseline to the post-intervention follow-up in the entire population (mean change for systolic blood pressure = −1.5 mmHg, 95% CI: −4.9, 1.8; mean change for diastolic blood pressure = 0 mmHg, 95% CI: −2.1, 2.1) (Table 2). Mean changes in blood pressure among different subgroups of the population indicated that the subgroups with higher baseline blood pressure levels experienced greater reductions in blood pressure from baseline to follow-up. Although not a statistically significant difference (p=0.16 comparing the mean changes), obese participants experienced, on average, a 4.6 mmHg reduction (95% CI: −10.0, 0.8) in systolic blood pressure while non-obese participants experienced a 0.3 mmHg increase (95% CI: −3.9, 4.6). Similar trends in systolic and diastolic blood pressure were observed among those reporting exposure to secondhand smoke and doctor-diagnosed heart disease (Table 2). We did not observe differences in mean blood pressure changes by pig, chicken, television, or radio ownership (results not presented); however, suggestive evidence for greater decreases in blood pressure was observed for those reporting no formal education as compared to those reporting 1–5 years and 6 or more years of education (Table 2). Those in the oldest age tertile experienced a larger reduction in blood pressure (mean systolic blood pressure change = −5.9, 95% CI: −11.3, −0.4; mean diastolic blood pressure change = −1.8, 95% CI: −5.4, 1.7). Larger blood pressure reductions were observed when limiting the older population to those greater than 50 years (Table 2). Systolic and diastolic blood pressure demonstrated similar patterns, but, reductions were larger for systolic blood pressure.

Table 2.

Mean changes from baseline to follow-up in systolic and diastolic blood pressure by population characteristics.

| Systolic Blood Pressure | Diastolic Blood Pressure | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Characteristic | N | Baseline Mean | Baseline SD | Mean Change | 95% CI for the mean change | p-valuea | Baseline Mean | Baseline SD | Mean Change | 95% CI for the mean change | p-value a |

| Total Population | 74 | 120.2 | 21.3 | −1.5 | −4.9, 1.8 | 75.2 | 11.6 | 0 | −2.14, 2.14 | ||

| Obesity status | |||||||||||

| Yes | 28 | 131.5 | 24.8 | −4.6 | −10.0, 0.8 | ref | 81.7 | 12.4 | −1.9 | −5.3, 1.6 | ref |

| No | 46 | 113.3 | 15.5 | 0.3 | −3.9, 4.6 | 0.16 | 71.2 | 9.1 | 1.1 | −1.6, 3.8 | 0.18 |

| SHS exposure in the home | |||||||||||

| Yes | 30 | 122.9 | 26.0 | −4.5 | −9.7, 0.7 | ref | 76.4 | 13.5 | −1.2 | −4.6, 2.2 | ref |

| No | 44 | 118.4 | 17.5 | 0.5 | −3.8, 4.8 | 0.14 | 74.4 | 10.2 | 0.8 | −2.0, 3.6 | 0.35 |

| Doctor-diagnosed heart disease | |||||||||||

| Yes | 10 | 130.1 | 32.0 | −6.2 | −15.4, 3.0 | ref | 78.2 | 16.6 | −0.5 | −6.3, 5.4 | ref |

| No | 63 | 118.7 | 19.2 | −0.7 | −4.3, 3.0 | 0.27 | 74.6 | 10.8 | 0.3 | −2.0, 2.6 | 0.82 |

| Education | |||||||||||

| 0 years | 28 | 125.7 | 23.3 | −3.7 | −9.1, 1.8 | ref | 77.7 | 11.4 | −1.0 | −4.6, 2.5 | ref |

| 1–5 years | 25 | 119.5 | 19.4 | −0.1 | −5.9, 5.7 | 0.37 | 76.6 | 10.5 | 0.1 | −3.6, 3.9 | 0.66 |

| 6+ years | 20 | 112.5 | 19.1 | 0.7 | −5.8, 7.1 | 0.31 | 70.0 | 12.3 | 1.4 | −2.8, 5.6 | 0.38 |

| Age at baseline (approximate tertiles) | |||||||||||

| 11 – 25 years | 22 | 108.1 | 9.8 | 2.1 | −3.9, 8.2 | ref | 68.1 | 7.8 | 2.7 | −1.2, 6.6 | ref |

| 26 – 39 years | 25 | 115.7 | 15.8 | −0.1 | −5.8, 5.6 | 0.60 | 75.7 | 12.4 | −0.4 | −4.1, 3.3 | 0.25 |

| 40 or more years | 27 | 134.3 | 24.9 | −5.9 | −11.3, −0.4 | 0.05 | 80.5 | 10.7 | −1.8 | −5.4, 1.7 | 0.09 |

| Age at baseline (50 year cut-point) | |||||||||||

| ≤ 50 years | 62 | 115.6 | 16.7 | 0.048 | −3.5, 3.6 | ref | 73.9 | 11.3 | 0.7 | −1.6, 3.0 | ref |

| > 50 years | 12 | 143.9 | 27.2 | −9.7 | −17.8, −1.5 | 0.03 | 82.0 | 11.3 | −3.8 | −9.0, 1.5 | 0.13 |

p-values comparing the difference between subgroup least-square mean changes (testing the null hypothesis that the subgroup mean change is equal to the reference group [ref]);

Obesity defined as BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2; body mass index; SHS, secondhand smoke; CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation

Although mean reductions in blood pressure were slightly greater after excluding participants less than 18 years of age at baseline (mean change in systolic blood pressure = −2.4 mmHg, 95% CI: −6.1, 1.3; mean change in diastolic blood pressure = −0.9, 95% CI: −3.2, 1.4; n=64), results comparing mean changes in the subgroups were not appreciably altered (results not presented). Results from additional sensitivity analyses (including women taking blood pressure medication and removing previous smokers) were similar to the primary results (results not presented).

Although population subgroup classifications were analyzed separately for differences in mean blood pressure changes, the classifications (by obesity, age, education, secondhand smoke exposure, and self-reported use of the traditional open fire during the follow-up year) were evaluated for independence. We observed that the more educated participants were less likely to be obese (p=0.003), the older participants were more likely to be obese (p<0.0001), and the younger participants were more likely to report more years of education (p<0.0001).

Discussion

In this longitudinal intervention study using a cookstove that reduced average indoor PM2.5 concentrations by 77%, we observed a 5.9 mmHg reduction (95% CI: −11.3, −0.4) in systolic blood pressure among women 40 years of age or older. Results for this age group are supported by two previous cookstove studies. Baumgartner et al. (2011) reported a cross-sectional relationship among rural Chinese women between personal exposure to PM2.5 from biomass combustion and elevated blood pressure that was stronger among women greater than 50 years of age (4.1 mmHg increase in systolic blood pressure per 1 log-transformed μg/m3 unit increase in PM2.5). Our longitudinal study design is more comparable to a chimney stove intervention conducted in Guatemala by McCracken et al. (2007). The mean within-person change before and after the stove intervention was −3.1 mmHg (95% CI: −5.3, −0.8) for systolic blood pressure. The mean age of the Guatemalan population was 53.3 years which is more consistent with our subgroup that included older women. Our results do not provide evidence of an effect of a cookstove intervention on blood pressure among women less than 40 years of age.

Although the small sample size and lack of statistically significant results limit our ability to make strong conclusions, obese participants and those reporting secondhand smoke exposures in the home demonstrated reductions in blood pressure from baseline to follow-up with weaker evidence for blood pressure reductions among those with doctor-diagnosed heart disease and lower education levels. Several investigators have hypothesized that those more susceptible to the adverse effects of increased exposures may also be the groups that benefit most from efforts to reduce air pollution levels (Levy et al., 2002; Tonne et al., 2008). However, it is not known if larger predicted benefits among these subpopulations are due to differences in greater relative improvements associated with air pollution reductions or differences in absolute improvements due to poorer baseline health status, which may be independent of air pollution (Levy et al., 2002). Here, we observed evidence suggesting that susceptible participants may be the only ones to benefit from a cookstove intervention (i.e., we did not observe blood pressure improvements among the entire population). There was no indication that these groups experienced greater reductions in exposure concentrations as a result of the intervention. These results demonstrating greater differences in mean blood pressure improvements in subgroups with poorer baseline health (i.e., higher baseline blood pressure) provide evidence supporting the hypothesis that susceptible populations will benefit most from interventions that reduce air pollution exposures.

Hypothesized mechanisms regarding the biologic plausibility for the cardiovascular health effects of air pollution involve multiple pathways, which can include pulmonary and systemic inflammation and oxidative stress, vascular alterations, and altered cardiac autonomic function (Pope and Dockery, 2006; Brook et al., 2010). A few studies have examined potential mechanistic pathways involving air pollution due to biomass-burning. Ray et al. (2006) reported increased activation of platelets and formations of platelet-leukocyte complexes among biomass users compared to liquid petroleum gas users in India. Barregard et al. (2006) reported small exposure-related increases in inflammatory mediators, such as Serum Amyloid A and Factor VIIIc, after a four-hour controlled exposure to wood smoke. Finally, McCracken et al. (2011) observed reduced occurrences of ST-segment depression (a measure of ventricular repolarization) following a wood-burning chimney stove intervention. Evidence from the ambient air pollution literature suggests that older (National Research Council, 2004), obese (Delfino et al., 2010; Dubowsky et al., 2006; Kannan et al., 2010), those with existing hypertension (Auchincloss et al., 2008), or socioeconomically disadvantaged (O’Neill et al., 2003) groups of people may be more susceptible, potentially due to underlying chronic inflammation (Huang et al., 2012; Libby et al., 2002), to the adverse health effects of increased air pollution exposures.

Although we observed improvement in blood pressure following one year of Eco-stove use for certain subgroups, it is possible that the full potential of the cookstove intervention was not realized among the entire population due to incomplete adoption of the new stove and mixed use of the traditional and new stove. Nearly half of the study population reported continued use of the traditional stove either alone or in conjunction with the Eco-stove; lack of complete and sustained adoption has previously limited cookstove intervention impacts (Pine et al., 2011; Ruiz-Mercado et al., 2011), although adoption is not always reported. We observed a 77% reduction in indoor PM concentrations approximately one year after the installation of the Eco-stove; however, the post-intervention concentrations were still relatively high, particularly compared to standards for ambient air pollution in developed countries (WHO, 2005). Smith and Peel (2010) recently demonstrated that the exposure–response relationship for particulate matter and cardiovascular disease risk, which begins to plateau at relatively high PM doses (Pope et al., 2009), implies much larger public health benefits for cookstove interventions that achieve relatively low PM doses (i.e. those typically experienced in relatively clean ambient environments). Therefore, the post-intervention mean pollution concentrations may not have been low enough to produce an even larger impact on blood pressure.

This study may be limited by misclassification of blood pressure if measures on one day during each year of the study are not typical of longer-term blood pressure levels; this would likely result in non-differential misclassification. Although we compared blood pressure changes within person over time, thus eliminating confounding by between-person factors, we cannot rule out the potential for confounding by time-varying factors (e.g., age, diet, or health policy changes; or changes in other exposures, such as trash burning outside) due to the lack of a control arm in the study. For a factor to act as a confounder it would need to have changed systematically over time (e.g., either increased or decreased from pre- to post-intervention). Neither we nor our local partners are aware of any health policy change or intervention that occurred simultaneously with our cookstove intervention. Age-related increases in blood pressure are well-described (Pearson et al., 1997; Franklin et al., 1997); for example, systolic blood pressure remains relatively stable until around age 40 in healthy women, then increases by 5–8 mmHg per decade (Pearson et al., 1997). If small age-related increases in blood pressure occurred in this study population over the course of the one-year follow-up, then the impact of the stove intervention is likely underestimated. Changes in dietary habits within person over the course of the study could also confound results. Although resources, and therefore types of foods consumed, likely did not change over the course of the one-year follow-up, it is possible that foods were prepared differently with the introduction of the plancha stove top. We did not systematically measure any potentially time-varying factors that may have confounded the results and therefore were not able to adjust for these changes if they occurred. Another limitation is that we cannot rule out the possibility that the observed blood pressure reductions among the subgroups are due to regression to the mean (Barnett et al., 2005); however, those with elevated baseline blood pressure were those with known risk factors (i.e. older, obese) for high blood pressure. Additionally, defined subgroups (i.e. obesity, age, education) were not independent of each other, limiting our ability to distinguish the independent impact of each factors. Finally, given that not all women in El Fortin were eligible and communities in other locations are different, our results may not be generalizable to all populations (e.g. different stove types and cooking practices may influence results). Despite these limitations, strengths of this study include longitudinal measures that were taken during the same season and approximate time of day, the selection of a study community with no other major sources of air pollution (i.e. major roads), the evaluation of subgroups that may benefit most from cookstove interventions, and a relatively long follow-up (post-intervention measures taken 272 to 383 days after the introduction of the Eco-stove).

Conclusion

Household air pollution from biomass combustion accounts for an estimated 2.0 million premature deaths per year worldwide, representing about 3.3% of the global disease burden (WHO, 2009). However, these estimates are based on extrapolation, primarily from observational studies of respiratory effects (Bruce et al., 2002; Ezzati and Kammen, 2002; Naeher et al., 2005; Smith, 2002). Cardiovascular disease is a growing and under studied disease in developing countries (Reddy, 2004; Yusuf et al., 2001; Yusuf et al., 2004; Narayan et al., 2010), and it is the leading cause of death in Nicaragua (PAHO, 2007). The importance of blood pressure, even within the normotensive range, as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease is well accepted (Urch et al., 2005; Vasan et al., 2001); a 2 mmHg downward shift in population average systolic blood pressure could result in 10% lower mortality (Lewington et al., 2002). Therefore, changes in the range observed in our study could result in a large public health impact. Additionally, the increasing prevalence of obesity in many developing countries, including those of Latin America, is a growing concern (Bautista et al., 2009; Martorell et al., 2000). Our results suggest that people with certain risk factors (i.e. age, obesity) for elevated baseline blood pressure may be more likely to experience post-intervention improvements in blood pressure. Although these results are supported by evidence from the ambient air pollution literature, this is the first study to compare and describe differences in blood pressure reductions between these subgroups in the context of a cookstove intervention study.

Practical Implications.

Nearly half the world’s population is regularly exposed to extremely high household air pollution concentrations from the use of traditional, inefficient and poorly vented indoor cookstoves. Cleaner-burning stove designs have the potential to substantially reduce pollutant emissions and indoor air pollution exposures; however, few studies have been conducted to evaluate cardiovascular health improvements following a cookstove intervention. In this longitudinal intervention study using a cookstove that reduced average indoor particulate matter concentrations by 77%, we observed greater systolic blood pressure improvements among certain subgroups of the population (e.g., older and obese participants). These results demonstrating greater differences in mean blood pressure improvements in subgroups with poorer baseline health (i.e., higher baseline blood pressure) provide evidence supporting the hypothesis that susceptible populations will benefit most from interventions that reduce air pollution exposures.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (R03 ES019696-01); the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Mountain and Plains Education and Research Center; and the Colorado State University, College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, College Research Council. We gratefully acknowledge Casa de la Mujer (Granada, Nicaragua) for logistical support, Maria Teresa Nurinda, Maria del Trancito Murillo, Maria Jose Narvaez Murillo, Gloria Elena Rodriguez, the CSU student field teams, William Marquardt, and Allison Shaw.

References

- Albalak R, Bruce N, Mccracken JP, Smith KR, De Gallardo T. Indoor respirable particulate matter concentrations from an open fire, improved cookstove, and LPG/open fire combination in a rural Guatemalan community. Environmental Science & Technology. 2001;35:2650–5. doi: 10.1021/es001940m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auchincloss AH, Diez Roux AV, Dvonch JT, Brown PL, Barr RG, Daviglus ML, Goff DC, Kaufman JD, O’neill MS. Associations between recent exposure to ambient fine particulate matter and blood pressure in the Multi-ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Environmental Health Perspectives. 2008;116:486–91. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett AG, Van Der Pols JC, Dobson AJ. Regression to the mean: what it is and how to deal with it. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;34:215–20. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barregard L, Sällsten G, Gustafson P, Andersson L, Johansson L, Basu S, Stigendal L. Experimental Exposure to Wood-Smoke Particles in Healthy Humans: Effects on Markers of Inflammation, Coagulation, and Lipid Peroxidation. Inhalation Toxicology. 2006;18:845–853. doi: 10.1080/08958370600685798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner J, Schauer JJ, Ezzati M, Lu L, Cheng C, Patz JA, Bautista LE. Indoor air pollution and blood pressure in adult women living in rural china. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2011;119:1390–5. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista LE, Casas JP, Herrera VM, Miranda JJ, Perel P, Pichardo R, Gonzalez A, Sanchez JR, Ferreccio C, Aguilera X, Silva E, Orostegui M, Gomez LF, Chirinos JA, Medina-Lezama J, Perez CM, Suarez E, Ortiz AP, Rosero L, Schapochnik N, Ortiz Z, Ferrante D. The Latin American Consortium of Studies in Obesity (LASO) Obes Rev. 2009;10:364–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00591.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook RD, Rajagopalan S, Pope CA, 3rd, Brook JR, Bhatnagar A, Diez-Roux AV, Holguin F, Hong Y, Luepker RV, Mittleman MA, Peters A, Siscovick D, Smith SC, Jr, Whitsel L, Kaufman JD. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: An update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:2331–78. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181dbece1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce N, Mccracken J, Albalak R, Schei MA, Smith KR, Lopez V, West C. Impact of improved stoves, house construction and child location on levels of indoor air pollution exposure in young Guatemalan children. Journal of Exposure Analysis and Environmental Epidemiology. 2004;14(Suppl 1):S26–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce N, Neufeld L, Boy E, West C. Indoor biofuel air pollution and respiratory health: the role of confounding factors among women in highland Guatemala. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1998;27:454–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/27.3.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce N, Perez-Padilla R, Albalak R. The health effects of indoor air pollution exposure in developing countries. In: BRUCE N, PEREZ-PADILLA R, ALBALAK R, editors. WHO/SDE/OEH/02.05. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Clark ML, Bazemore H, Reynolds SJ, Heiderscheidt JM, Conway S, Bachand AM, Volckens J, Peel JL. A baseline evaluation of traditional cook stove smoke exposures and indicators of cardiovascular and respiratory health among Nicaraguan women. International Journal of Occupational & Environmental Health. 2011;17:113–21. doi: 10.1179/107735211799030942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delfino RJ, Tjoa T, Gillen DL, Staimer N, Polidori A, Arhami M, Jamner L, Sioutas C, Longhurst J. Traffic-related air pollution and blood pressure in elderly subjects with coronary artery disease. Epidemiology. 2010;21:396–404. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181d5e19b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubowsky SD, Suh H, Schwartz J, Coull BA, Gold DR. Diabetes, obesity, and hypertension may enhance associations between air pollution and markers of systemic inflammation. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2006;114:992–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzati M, Kammen DM. The health impacts of exposure to indoor air pollution from solid fuels in developing countries: knowledge, gaps, and data needs. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2002;110:1057–68. doi: 10.1289/ehp.021101057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin SS, Gustin WT, Wong ND, Larson MG, Weber MA, Kannel WB, Levy D. Hemodynamic patterns of age-related changes in blood pressure. The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1997;96:308–15. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.1.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Zhu T, Pan X, Hu M, Lu SE, Lin Y, Wang T, Zhang Y, Tang X. Air pollution and autonomic and vascular dysfunction in patients with cardiovascular disease: interactions of systemic inflammation, overweight, and gender. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176(2):117–126. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannan S, Dvonch JT, Schulz AJ, Israel BA, Mentz G, House J, Max P, Reyes AG. Exposure to fine particulate matter and acute effects on blood pressure: effect modification by measures of obesity and location. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2010;64:68–74. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.081836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy JI, Greco SL, Spengler JD. The importance of population susceptibility for air pollution risk assessment: a case study of power plants near Washington, DC. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2002;110:1253–60. doi: 10.1289/ehp.021101253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:1903–13. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11911-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby P, Ridker PM, Maseri A. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;105:1135–43. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin WJ, 2nd, Glass RI, Balbus JM, Collins FS. Public health. A major environmental cause of death. Science. 2011;334:180–1. doi: 10.1126/science.1213088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martorell R, Khan LK, Hughes ML, Grummer-Strawn LM. Obesity in women from developing countries. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2000;54:247–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mccracken J, Smith KR, Stone P, Diaz A, Arana B, Schwartz J. Intervention to Lower Household Woodsmoke Exposure in Guatemala Reduces ST-segment Depression on Electrocardiograms. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2011;119:1562–1568. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mccracken JP, Smith KR, Diaz A, Mittleman MA, Schwartz J. Chimney stove intervention to reduce long-term wood smoke exposure lowers blood pressure among Guatemalan women. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2007;115:996–1001. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naeher LP, Brauer M, Lipsett M, Zelikoff JT, Simpson CD, Koenig JQ, Smith KR. Woodsmoke health effects: a review. Inhalation Toxicology. 2007;19:67–106. doi: 10.1080/08958370600985875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naeher LP, Smith KR, Brauer M, Chowdhury Z, Simpson C, Koenig JQ, Lipsett M, Zelikoff JT. Critical Review of the Health Effects of Woodsmoke. Ottawa: Air Health Division, Health Canada; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Naeher LP, Smith KR, Leaderer BP, Mage D, Grajeda R. Indoor and outdoor PM2.5 and CO in high- and low-density Guatemalan villages. Journal of Exposure Analysis and Environmental Epidemiology. 2000b;10:544–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan KM, Ali MK, Koplan JP. Global noncommunicable diseases--where worlds meet. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363:1196–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1002024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Research Priorities for Airborne Particulate Matter; IV, Continuing Research Progress. Washington, D.C: The National Academies Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- O’neill MS, Jerrett M, Kawachi I, Levy JI, Cohen AJ, Gouveia N, Wilkinson P, Fletcher T, Cifuentes L, Schwartz J. Health, wealth, and air pollution: advancing theory and methods. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2003;111:1861–70. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paho . Health in the Americas, 2007 Edition. Washington DC, USA: Pan American Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson JD, Morrell CH, Brant LJ, Landis PK, Fleg JL. Age-associated changes in blood pressure in a longitudinal study of healthy men and women. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 1997;52:M177–83. doi: 10.1093/gerona/52a.3.m177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, Falkner BE, Graves J, Hill MN, Jones DW, Kurtz T, Sheps SG, Roccella EJ. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation. 2005;111(5):697–716. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000154900.76284.F6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine K, Edwards R, Masera O, Schilmann A, Marron-Mares A, Riojas-Rodriguez H. Adoption and use of improved biomass stoves in Rural Mexico. Energy for Sustainable Development. 2011;15:176–183. [Google Scholar]

- Pope CA, 3rd, Dockery DW. Health effects of fine particulate air pollution: lines that connect. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 2006;56:709–42. doi: 10.1080/10473289.2006.10464485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope CA, 3rd, Burnett RT, Krewski D, Jerrett M, Shi Y, Calle EE, Thun MJ. Cardiovascular mortality and exposure to airborne fine particulate matter and cigarette smoke: shape of the exposure-response relationship. Circulation. 2009;120:941–948. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.857888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray MR, Mukherjee S, Roychoudhury S, Bhattacharya P, Banerjee M, Siddique S, Chakraborty S, Lahiri T. Platelet activation, upregulation of CD11b/CD18 expression on leukocytes and increase in circulating leukocyte-platelet aggregates in Indian women chronically exposed to biomass smoke. Human & Experimental Toxicology. 2006;25:627. doi: 10.1177/0960327106074603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy KS. Cardiovascular disease in non-Western countries. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;350:2438–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehfuess E, Mehta S, Pruss-Ustun A. Assessing Household Solid Fuel Use: Multiple Implications for the Millennium Development Goals. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2006;114:373–378. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romieu I, Riojas-Rodriguez H, Marron-Mares AT, Schilmann A, Perez-Padilla R, Masera O. Improved biomass stove intervention in rural Mexico: impact on the respiratory health of women. American Journal of Respiratory & Critical Care Medicine. 2009;180:649–56. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200810-1556OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Mercado I, Masera O, Zamora H, Smith KR. Adoption and sustained use of improved cookstoves. Energy Policy. 2011;39:7557–7566. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks JD, Stanek LW, Luben TJ, Johns DO, Buckley BJ, Brown JS, Ross M. Particulate matter-induced health effects: who is susceptible? Environmental Health Perspectives. 2011;119:446–54. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Sivertsen T, Diaz E, Pope D, Lie RT, Diaz A, Mccracken J, Bakke P, Arana B, Smith KR, Bruce N. Effect of reducing indoor air pollution on women’s respiratory symptoms and lung function: the RESPIRE Randomized Trial, Guatemala. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;170:211–20. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KR. Indoor air pollution in developing countries: recommendations for research. Indoor Air. 2002;12:198–207. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0668.2002.01137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KR, Mccracken JP, Weber MW, Hubbard A, Jenny A, Thompson LM, Balmes J, Diaz A, Arana B, Bruce N. Effect of reduction in household air pollution on childhood pneumonia in Guatemala (RESPIRE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378:1717–26. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60921-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KR, Peel JL. Mind the gap. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2010;118:1643–5. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonne C, Beevers S, Armstrong B, Kelly F, Wilkinson P. Air pollution and mortality benefits of the London Congestion Charge: spatial and socioeconomic inequalities. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2008;65:620–7. doi: 10.1136/oem.2007.036533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull F. Effects of different blood-pressure-lowering regimens on major cardiovascular events: results of prospectively-designed overviews of randomised trials. Lancet. 2003;362:1527–35. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14739-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urch B, Silverman F, Corey P, Brook JR, Lukic KZ, Rajagopalan S, Brook RD. Acute blood pressure responses in healthy adults during controlled air pollution exposures. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2005;113:1052–5. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasan RS, Larson MG, Leip EP, Evans JC, O’donnell CJ, Kannel WB, Levy D. Impact of high-normal blood pressure on the risk of cardiovascular disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345:1291–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Who. WHO Air Quality Guidelines: Global Update for 2005. Copenhagen: World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Who. Global Health Risks: Mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf S, Reddy S, Ounpuu S, Anand S. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: part I: general considerations, the epidemiologic transition, risk factors, and impact of urbanization. Circulation. 2001;104:2746–53. doi: 10.1161/hc4601.099487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf S, Vaz M, Pais P. Tackling the challenge of cardiovascular disease burden in developing countries. Am Heart J. 2004;148:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]