Exome sequencing studies of autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) have identified many de novo mutations, but few recurrently disrupted genes. We therefore developed a modified molecular inversion probe method enabling ultra-low-cost candidate gene resequencing in very large cohorts. To demonstrate the power of this approach, we captured and sequenced 44 candidate genes in 2,446 ASD probands. We discovered 27 de novo events in 16 genes, 59% of which are predicted to truncate proteins or disrupt splicing. We estimate that recurrent disruptive mutations in six genes—CHD8, DYRK1A, GRIN2B, TBR1, PTEN, and TBL1XR1—may contribute to 1% of sporadic ASDs. Our data support associations between specific genes and reciprocal subphenotypes (CHD8-macrocephaly, DYRK1A-microcephaly) and replicate the importance of a β-catenin/chromatin remodeling network to ASD etiology.

There is considerable interest in the contribution of rare variants and de novo mutations to the genetic basis of complex phenotypes such as autism spectrum disorders (ASD). However, because of extreme genetic heterogeneity, the sample sizes required to implicate any single gene in a complex phenotype are extremely large (1). Exome sequencing has identified hundreds of ASD candidate genes on the basis of de novo mutations observed in the affected offspring of unaffected parents (2–6). Yet, only a single mutation was observed in nearly all such genes, and sequencing of over 900 trios was insufficient to establish mutations at any single gene as definitive genetic risk factors (2–6).

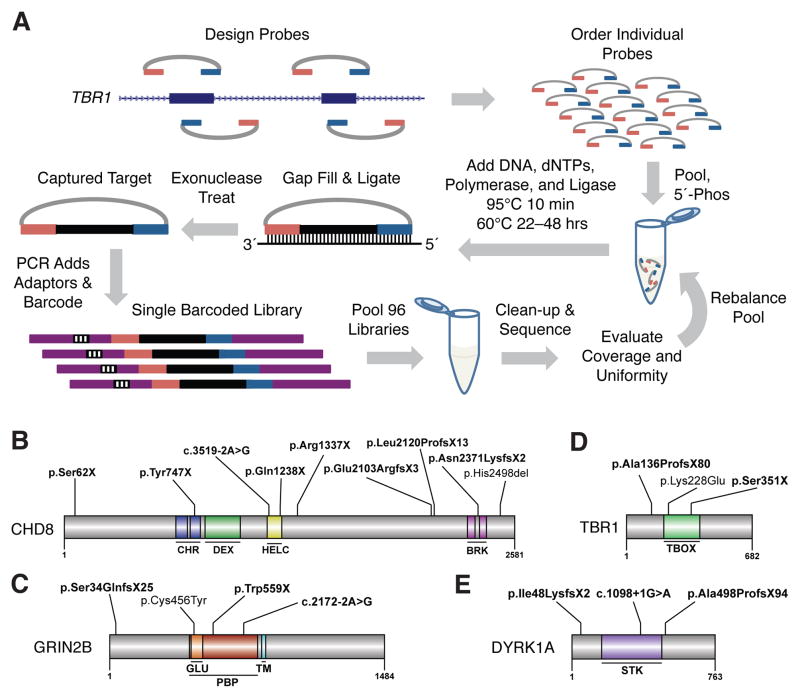

To address this, we sought to evaluate candidate genes identified by exome sequencing (2, 3) for de novo mutations in a much larger ASD cohort. We developed a modified molecular inversion probe (MIP) strategy (Fig. 1A) (7–9) with novel algorithms for MIP design; an optimized, automatable workflow with robust performance and minimal DNA input; extensive multiplexing of samples while sequencing; and reagent costs of less than $1 per gene per sample. Extensive validation using several probe sets and sample collections demonstrated 99% sensitivity and 98% positive predictive value for single nucleotide variants at well-covered positions i.e., 92% to 98% of targeted bases (figs. S1–S7 and tables S1–S9) (10).

Fig. 1.

Massively multiplex targeted sequencing identifies recurrently mutated genes in ASD probands. (A) Schematic showing design and general workflow of a modified MIP method enabling ultra-low-cost candidate gene resequencing in very large cohorts (figs. S1–S7 and tables S1–S9) (10). (B to E) Protein diagrams of four genes with multiple de novo mutation events. Significant protein domains for the largest protein isoform are shown (colored regions) as defined by SMART (23) with mutation locations indicated. (B) CHD8. (C) GRIN2B. (D) TBR1. (E) DYRK1A. Bold variants are nonsense, frameshifting indels or at splice-sites (intron-exon junction is indicated). Domain abbreviations: CHR-chromatin organization modifier, DEX-DEAD-like helicases superfamily, HELC-helicase superfamily c-terminal, BRK-domain in transcription and CHROMO domain helicases, GLU-ligated ion channel L-glutamate- and glycine-binding site, PBP-eukaryotic homologs of bacterial periplasmic substrate binding proteins, TM-transmembrane, STK-serine-threonine kinase catalytic, TBOX-T-box DNA binding.

We applied this method to 2,494 ASD probands from the Simons Simplex Collection (SSC) (11) using two probe sets [ASD1 (6 genes) and ASD2 (38 genes)] to target 44 ASD candidate genes (12). Preliminary results using ASD1 on a subset of the SSC implicated GRIN2B as a risk locus (3). The 44 genes were selected from 192 candidates (2, 3), focusing on genes with disruptive mutations, associations with syndromic autism (13), overlap with known or suspected neurodevelopmental CNV risk loci (13, 14), structural similarities, and/or neuronal expression (table S3). Although a few of the 44 genes have been reported disrupted in individuals with neurodevelopmental or neuropsychiatric disorders (often including concurrent dysmorphologies), their role in so-called idiopathic ASD has not been rigorously established. Twenty-three of the 44 genes intersect a 49-member β-catenin/chromatin remodeling protein-protein interaction (PPI) network (2) or an expanded 74-member network (figs. S8 and S9) (3, 4).

We required samples to successfully capture with both probe sets, yielding 2,446 ASD probands with MIP data, 2,364 of which had only MIP data and 82 of which we previously exome sequenced (2, 3). The high GC content of several candidates required considerable rebalancing to improve capture uniformity (12) (figs. S3A and S10). Nevertheless, the reproducible behavior of most MIPs allowed us to identify copy number variation at targeted genes, including several inherited duplications (figs. S11 and S12 and table S10).

To discover de novo mutations, we first identified candidate sites by filtering against variants observed in other cohorts, including non-ASD exomes and MIP-based resequencing of 762 healthy, non-ASD individuals (12). The remaining candidates were further tested by MIP-based resequencing of the proband’s parents and, if potentially de novo, confirmed by Sanger sequencing of the parent-child trio (10, 12). We discovered 27 de novo mutations that occurred in 16 of the 44 genes (Fig. 1, B–E; Table 1; and table S11). Consistent with an increased sensitivity for MIP-based resequencing, six of these were not reported in exome-sequenced individuals (Table 1, tables S5 and S11, and fig. S13) (3, 4, 6). Notably, the proportion of de novo events that are severely disruptive, i.e., coding indels, nonsense mutations, and splice-site disruptions (17/27 or 0.63), is fourfold greater than the expected proportion for random de novo mutations (0.16, binomial p = 4.9×10−8) (table S12) (15).

Table 1.

Six genes with recurrent de novo mutations. Abbreviations: M-male, F-female, Mut-mutation type, fs-frameshifting indel, ns-nonsense, sp-splice-site, aa-single amino acid deletion, ms-missense, HGVS-; NVIQ-nonverbal intellectual quotient.

| Proband | Sex | Gene | Mut | Assay | HGVS | NVIQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12714.p1 | M | CHD8* | ns | MIP | p.Ser62X | 78 |

| 13986.p1 | M | CHD8* | fs | MIP | p.Tyr747X | 38 |

| 11654.p1 | F | CHD8* | sp | MIP|| (4) | c.3519-2A>G | 41 |

| 13844.p1 | M | CHD8* | ns | EX | p.Gln1238X | 34 |

| 14016.p1 | M | CHD8* | ns | MIP | p.Arg1337X | 92 |

| 12991.p1 | M | CHD8* | fs | MIP | p.Glu2103ArgfsX3 | 67 |

| 12752.p1 | F | CHD8* | fs | EX | p.Leu2120ProfsX13 | 93 |

| 14233.p1 | M | CHD8* | fs | MIP | p.Asn2371LysfsX2 | 19 |

| 14406.p1 | M | CHD8* | aa | MIP | p.His2498del | 98 |

| 12099.p1 | M | DYRK1A* | fs | MIP|| (4) | p.Ile48LysfsX2 | 55 |

| 13890.p1 | F | DYRK1A* | sp | EX | c.1098+1G>A | 42 |

| 13552.p1 | M | DYRK1A* | fs | MIP¶ (6) | p.Ala498ProfsX94 | 66 |

| 11691.p1 | M | GRIN2B† | fs | MIP§,|| (3) | p.Ser34GlnfsX25 | 62 |

| 13932.p1 | M | GRIN2B† | ms | MIP | p.Cys456Tyr | 55 |

| 12547.p1 | M | GRIN2B† | ns | MIP§ | p.Trp559X | 65 |

| 12681.p1 | F | GRIN2B† | sp | EX | c.2172-2A>G | 65 |

| 14433.p1 | M | PTEN | ms | MIP | p.Thr131Ile | 50 |

| 14611.p1 | M | PTEN | fs | MIP | p.Cys136MetfsX44 | 33 |

| 11390.p1 | F | PTEN | ms | EX | p.Thr167Asn | 77 |

| 12335.p1 | F | TBL1XR1* | ms | EX | p.Leu282Pro | 47 |

| 14612.p1 | M | TBL1XR1* | fs | MIP | p.Ile397SerfsX19 | 41 |

| 11480.p1 | M | TBR1† | fs | EX | p.Ala136ProfsX80 | 41 |

| 13814.p1 | M | TBR1† | ms | MIP | p.Lys228Glu | 78 |

| 13796.p1 | F | TBR1† | fs | MIP|| (4) | p.Ser351X | 63 |

Given their extremely low frequency, accurately establishing expectation for de novo mutations in a locus-specific manner through the sequencing of control trios is impractical. We therefore developed a probabilistic model that incorporates the overall rate of mutation in coding sequences, estimates of relative locus-specific rates based on human-chimpanzee fixed differences (fig. S14 and table S13), and other factors that may influence the distribution of mutation classes, e.g., codon structure (12). We applied this model to estimate (by simulation) the probability of observing additional de novo mutations during MIP-based resequencing of the SSC cohort. To compare expectation and observation, we treated missense mutations as one class and severe disruptions as a second class. Thus, we could evaluate the probability at a given locus of observing at least X de novo mutations, of which at least Y belong to the severe class.

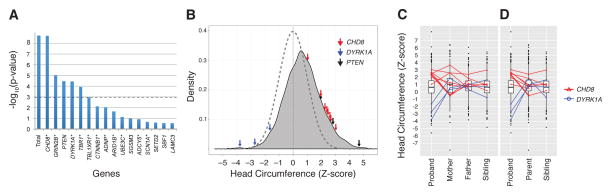

We found evidence of mutation burden—a higher rate of de novo mutation than expected—in the overall set of 44 genes (observed n = 27 vs. mean expected n = 5.6, simulated p < 2×10−9) (Fig. 2A). The burden was driven by the severe class (observed n = 17 vs. mean expected n = 0.58, simulated p < 2×10−9). Most severe class mutations intersected the 74-member PPI network (16/17), although only 23/44 genes are in this network (binomial p = 0.0002) (12). Furthermore, 21/27 mutations occurred in network-associated genes (binomial p = 0.004). Of the six individual genes (CHD8, GRIN2B, DYRK1A, PTEN, TBR1, and TBL1XR1) with evidence of mutation burden (alpha of 0.05 after a Holm-Bonferroni correction for multiple testing (Fig. 2A); TBL1XR1 is not significant with a more conservative Bonferroni correction), five fall within the β-catenin/chromatin remodeling network. In our combined MIP and exome data, ~1% (24/2,573) of ASD probands harbor a de novo mutation in one of these six genes, with CHD8 representing 0.35% (9/2,573) (Fig. 1B and Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Locus-specific mutation probabilities and associated phenotypes. (A) Estimated p-values for the observed number of additional de novo mutations identified in the MIP screen of 44 ASD candidate genes. Probabilities shown are for observing X or more events of which at least Y belong to the severe class. The observed numbers of mutations in all 44 genes (“Total”) and CHD8 were not seen in any of 5×108 simulations. Based on the simulation mean (0.0153), the Poisson probability for seven or more severe class CHD8 mutations is 3.8×10−17. Dashed line Bonferroni corrected significance threshold for α = 0.05. *Gene product in the 74-member PPI connected component. (B–D) Standardized head circumference (HC) Z-scores for SSC. (B) All probands screened with superimposed normal distribution (dashed). HC Z-scores for individuals with de novo truncating/splice mutations highlighted for CHD8 (red arrows), DYRK1A (blue arrows), and PTEN (black arrows). (C and D) Box and whisker plots of the HC Z-scores for the SSC. Mutations carriers are shown and linked to their respective family members. (C) All family members. (D) Only proband sex-matched family members.

For these analyses, we conservatively used the highest available empirical estimate of the overall mutation rate in coding sequences (3). With the exception of TBL1XR, these results were robust to doubling the overall mutation rate, or to using the upper bound of the 95% confidence interval of the locus-specific rate estimate for each of these genes (10). Moreover, we obtained similar results regardless of whether parameters were estimated from rare, segregating variation or from de novo mutations in unaffected siblings (10), as well as with a sequence composition model based on genome-wide de novo mutation (16). Exome sequencing of non-ASD individuals (unaffected siblings or non-ASD cohorts) further support these conclusions (table S14) (10).

We also validated 23 inherited, severely disruptive variants in the 44 genes (table S15). Two probands with such variants carry de novo 16p11.2 duplications (table S16). Combining de novo and inherited events, severe class variants were observed at twice the rate in MIP-sequenced probands as compared with MIP-sequenced healthy, non-ASD individuals (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.083). Severe class variants were not transmitted to 14/20 unaffected siblings (binomial p = 0.058) (table S15). However, larger cohorts than currently exist will be needed to fully evaluate these modest trends.

We analyzed phenotypic data on probands with mutations in the six implicated genes. Each was diagnosed with autism on the basis of current, strict, gold-standard criteria. No obvious dysmorphologies or recurrent comorbidities were present. Probands tended to fall into the intellectual disability range for nonverbal IQ (NVIQ) (mean 58.3) (Table 1). However, for CHD8, probands were found to have NVIQ scores ranging from profoundly impaired to average (mean 62.2, range 19–98).

Given the previously observed microcephaly in our index DYRK1A mutation case, macrocephaly in both probands with CHD8 mutations (3), and the association of these traits with other syndromic loci (13, 17), we reexamined head circumference (HC) in the larger set of probands with protein-truncation or splice-site de novo events using age and sex normalized HC Z-scores (12) (Fig. 2B). For CHD8 (n = 8), we observed significantly larger head sizes relative to individuals screened without CHD8 mutations (two-sample permutation test, two-sided p = 0.0007). De novo CHD8 mutations are present in ~2% of macrocephalic (HC > 2.0) SSC probands (n = 366), suggesting a useful phenotype for patient subclassification. For DYRK1A (n = 3), we observed significantly smaller head sizes relative to individuals screened without DYRK1A mutations (two-sample permutation test, two-sided p = 0.0005). Comparison of head size in the context of the families (Fig. 2, C and D, and table S17) provides further support for this reciprocal trend (10). These findings are also consistent with case reports of patients with structural rearrangements and mouse transgenic models that implicate DYRK1A and CHD8 as regulators of brain growth (18–21). Macrocephaly was also observed in individuals with de novo and inherited PTEN mutations (22).

Our data support an important role for de novo mutations in six genes in ~1% of sporadic ASD. As the SSC was specifically established for simplex ASD and as its probands generally have higher cognitive functioning than has been reported in other ASD cohorts (11), it is unknown how our findings will translate into other cohorts. Furthermore, while implicating specific loci in ASD, our data are insufficient to evaluate whether the observed de novo mutations are sufficient to cause ASD (tables S16 and S18).

Exome sequencing and CNV studies suggest that there are hundreds of relevant genetic loci for ASD. Technologies and study designs directed at identifying de novo mutations, both for the discovery of ASD candidate genes as well as for their validation, provide sufficient power to implicate individual genes from a relatively small number of events. The analytical framework described here can be applied to any other disorder—simple or complex—for which de novo coding mutations are suspected to contribute to risk. Additionally, the experimental methods presented here are broadly useful for the rapid and economical resequencing of candidate genes in extremely large cohorts, as may be required for the definitive implication of rare variants or de novo mutations in any genetically complex disorder.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project and its ongoing studies which produced and provided exome variant calls for comparison: the Lung GO Sequencing Project (HL-102923), the WHI Sequencing Project (HL-102924), the Broad GO Sequencing Project (HL-102925), the Seattle GO Sequencing Project (HL-102926) and the Heart GO Sequencing Project (HL-103010), Benjamin Vernot, Megan Dennis, Tonia Brown, and other members of the Eichler and Shendure labs for helpful discussions. We are grateful to all of the families at the participating Simons Simplex Collection (SSC) sites, as well as the principal investigators (A. Beaudet, R. Bernier, J. Constantino, E. Cook, E. Fombonne, D. Geschwind, R. Goin-Kochel, E. Hanson, D. Grice, A. Klin, D. Ledbetter, C. Lord, C. Martin, D. Martin, R. Maxim, J. Miles, O. Ousley, K. Pelphrey, B. Peterson, J. Piggot, C. Saulnier, M. State, W. Stone, J. Sutcliffe, C. Walsh, Z. Warren, E. Wijsman). We appreciate obtaining access to phenotypic data on SFARI Base. Approved researchers can obtain the SSC population dataset described in this study (https://ordering.base.sfari.org/~browse_collection/archive[ssc_v13]/ui:view) by applying at https://base.sfari.org. This work was supported by a grant from the Simons Foundation (SFARI 137578, 191889 to E.E.E., J.S., and R.B.), NIH HD065285 (E.E.E. and J.S.), NIH NS069605 (H.C.M), and R01 NS 064077 (D.D.). E.B. is an Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellow. E.E.E. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Scientific advisory broad or consulting affiliations: Ariosa Diagnostics (J.S), Stratos Genomics (J.S), Good Start Genetics (J.S), Adaptive Biotechnologies (J.S), Pacific Biosciences (E.E.E), SynapDx (E.E.E.), DNAnexus (E.E.E.), and SFARI GENE (H.C.M.). B.J.O. is an inventor on patent PCT/US2009/30620: Mutations in Contactin Associated Protein 2 are Associated with Increased Risk for Idiopathic Autism. Raw sequencing data available at the National Database for Autism Research, NDARCOL1878.

Footnotes

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/science.1227764/DC1

Materials and Methods

References and Notes

- 1.Kryukov GV, Shpunt A, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Sunyaev SR. Power of deep, all-exon resequencing for discovery of human trait genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812824106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Roak BJ, et al. Exome sequencing in sporadic autism spectrum disorders identifies severe de novo mutations. Nat Genet. 2011;43:585. doi: 10.1038/ng.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Roak BJ, et al. Sporadic autism exomes reveal a highly interconnected protein network of de novo mutations. Nature. 2012;485:246. doi: 10.1038/nature10989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanders SJ, et al. De novo mutations revealed by whole-exome sequencing are strongly associated with autism. Nature. 2012;485:237. doi: 10.1038/nature10945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neale BM, et al. Patterns and rates of exonic de novo mutations in autism spectrum disorders. Nature. 2012;485:242. doi: 10.1038/nature11011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iossifov I, et al. De novo gene disruptions in children on the autistic spectrum. Neuron. 2012;74:285. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turner EH, Lee C, Ng SB, Nickerson DA, Shendure J. Massively parallel exon capture and library-free resequencing across 16 genomes. Nat Methods. 2009;6:315. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Porreca GJ, et al. Multiplex amplification of large sets of human exons. Nat Methods. 2007;4:931. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krishnakumar S, et al. A comprehensive assay for targeted multiplex amplification of human DNA sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803240105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.See supplementary text on Science Online.

- 11.Fischbach GD, Lord C. The Simons Simplex Collection: A resource for identification of autism genetic risk factors. Neuron. 2010;68:192. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Materials and methods are available as supplementary material on Science Online.

- 13.Betancur C. Etiological heterogeneity in autism spectrum disorders: More than 100 genetic and genomic disorders and still counting. Brain Res. 2011;1380:42. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.11.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper GM, et al. A copy number variation morbidity map of developmental delay. Nat Genet. 2011;43:838. doi: 10.1038/ng.909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lynch M. Rate, molecular spectrum, and consequences of human mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912629107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kong A, et al. Rate of de novo mutations and the importance of father’s age to disease risk. Nature. 2012;488:471. doi: 10.1038/nature11396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams CA, Dagli A, Battaglia A. Genetic disorders associated with macrocephaly. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:2023. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Møller RS, et al. Truncation of the Down syndrome candidate gene DYRK1A in two unrelated patients with microcephaly. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:1165. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Bon BW, et al. Intragenic deletion in DYRK1A leads to mental retardation and primary microcephaly. Clin Genet. 2011;79:296. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guedj F, et al. DYRK1A: A master regulatory protein controlling brain growth. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;46:190. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Talkowski ME, et al. Sequencing chromosomal abnormalities reveals neurodevelopmental loci that confer risk across diagnostic boundaries. Cell. 2012;149:525. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou J, Parada LF. PTEN signaling in autism spectrum disorders. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2012;22:873. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Letunic I, Doerks T, Bork P. SMART 7: Recent updates to the protein domain annotation resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):D302. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugimoto N, Nakano S, Yoneyama M, Honda K. Improved thermodynamic parameters and helix initiation factor to predict stability of DNA duplexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4501. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.22.4501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y, et al. Analysis of molecular inversion probe performance for allele copy number determination. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R246. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-11-r246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krumm N, et al. NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project, Copy number variation detection and genotyping from exome sequence data. Genome Res. 2012;22:1525. doi: 10.1101/gr.138115.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ren J, et al. DOG 1.0: Illustrator of protein domain structures. Cell Res. 2009;19:271. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li W-H. Molecular Evolution. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland, MA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tennessen JA, et al. Broad GO; Seattle GO; NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project, Evolution and functional impact of rare coding variation from deep sequencing of human exomes. Science. 2012;337:64. doi: 10.1126/science.1219240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen JQ, et al. Variation in the ratio of nucleotide substitution and indel rates across genomes in mammals and bacteria. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26:1523. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roche AF, Mukherjee D, Guo SM, Moore WM. Head circumference reference data: Birth to 18 years. Pediatrics. 1987;79:706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hothorn T, Hornik K, van de Wiel MAV, Zeileis A. Implementing a class of permutation tests: The coin package. J Stat Softw. 2008;28:1. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deng J, et al. Targeted bisulfite sequencing reveals changes in DNA methylation associated with nuclear reprogramming. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:353. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amiri A, et al. Pten deletion in adult hippocampal neural stem/progenitor cells causes cellular abnormalities and alters neurogenesis. J Neurosci. 2012;32:5880. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5462-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nishiyama M, Skoultchi AI, Nakayama KI. Histone H1 recruitment by CHD8 is essential for suppression of the Wnt-β-catenin signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:501. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06409-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishiyama M, et al. CHD8 suppresses p53-mediated apoptosis through histone H1 recruitment during early embryogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:172. doi: 10.1038/ncb1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thompson BA, Tremblay V, Lin G, Bochar DA. CHD8 is an ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling factor that regulates beta-catenin target genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:3894. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00322-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zahir F, et al. Novel deletions of 14q11.2 associated with developmental delay, cognitive impairment and similar minor anomalies in three children. J Med Genet. 2007;44:556. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.050823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bedogni F, et al. Tbr1 regulates regional and laminar identity of postmitotic neurons in developing neocortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:13129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002285107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Endele S, et al. Mutations in GRIN2A and GRIN2B encoding regulatory subunits of NMDA receptors cause variable neurodevelopmental phenotypes. Nat Genet. 2010;42:1021. doi: 10.1038/ng.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Myers RA, et al. A population genetic approach to mapping neurological disorder genes using deep resequencing. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1001318. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fotaki V, et al. Dyrk1A haploinsufficiency affects viability and causes developmental delay and abnormal brain morphology in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:6636. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.18.6636-6647.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Green RE, et al. A draft sequence of the Neandertal genome. Science. 2010;328:710. doi: 10.1126/science.1188021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hong JY, et al. Down’s-syndrome-related kinase Dyrk1A modulates the p120-catenin-Kaiso trajectory of the Wnt signaling pathway. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:561. doi: 10.1242/jcs.086173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li J, Wang CY. TBL1-TBLR1 and beta-catenin recruit each other to Wnt target-gene promoter for transcription activation and oncogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:160. doi: 10.1038/ncb1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choi HK, et al. Reversible SUMOylation of TBL1-TBLR1 regulates β-catenin-mediated Wnt signaling. Mol Cell. 2011;43:203. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanders SJ, et al. Multiple recurrent de novo CNVs, including duplications of the 7q11.23 Williams syndrome region, are strongly associated with autism. Neuron. 2011;70:863. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Horn D, et al. Identification of FOXP1 deletions in three unrelated patients with mental retardation and significant speech and language deficits. Hum Mutat. 2010;31:E1851. doi: 10.1002/humu.21362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hamdan FF, et al. De novo mutations in FOXP1 in cases with intellectual disability, autism, and language impairment. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:671. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Feuk L, et al. Absence of a paternally inherited FOXP2 gene in developmental verbal dyspraxia. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:965. doi: 10.1086/508902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lai CS, et al. The SPCH1 region on human 7q31: Genomic characterization of the critical interval and localization of translocations associated with speech and language disorder. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67:357. doi: 10.1086/303011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wei X, et al. NISC Comparative Sequencing Program, Exome sequencing identifies GRIN2A as frequently mutated in melanoma. Nat Genet. 2011;43:442. doi: 10.1038/ng.810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Awadalla P, et al. Direct measure of the de novo mutation rate in autism and schizophrenia cohorts. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:316. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jia P, et al. International Schizophrenia Consortium, Network-assisted investigation of combined causal signals from genome-wide association studies in schizophrenia. PLOS Comput Biol. 2012;8:e1002587. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tarabeux J, et al. S2D team, Rare mutations in N-methyl-D-aspartate glutamate receptors in autism spectrum disorders and schizophrenia. Transcult Psychiatry. 2011;1:e55. doi: 10.1038/tp.2011.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barak T, et al. Recessive LAMC3 mutations cause malformations of occipital cortical development. Nat Genet. 2011;43:590. doi: 10.1038/ng.836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lossin C. A catalog of SCN1A variants. Brain Dev. 2009;31:114. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim KS, et al. Adenylyl cyclase type 5 (AC5) is an essential mediator of morphine action. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:3908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508812103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pinhasov A, et al. Activity-dependent neuroprotective protein: A novel gene essential for brain formation. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2003;144:83. doi: 10.1016/S0165-3806(03)00162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hill JM, et al. Blockage of VIP during mouse embryogenesis modifies adult behavior and results in permanent changes in brain chemistry. J Mol Neurosci. 2007;31:183. doi: 10.1385/jmn:31:03:185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wat MJ, et al. Recurrent microdeletions of 15q25.2 are associated with increased risk of congenital diaphragmatic hernia, cognitive deficits and possibly Diamond—Blackfan anaemia. J Med Genet. 2010;47:777. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.075903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Santen GW, et al. Mutations in SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex gene ARID1B cause Coffin-Siris syndrome. Nat Genet. 2012;44:379. doi: 10.1038/ng.2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hoyer J, et al. Haploinsufficiency of ARID1B, a member of the SWI/SNF-a chromatin-remodeling complex, is a frequent cause of intellectual disability. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:565. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Halgren C, et al. Corpus callosum abnormalities, intellectual disability, speech impairment, and autism in patients with haploinsufficiency of ARID1B. Clin Genet. 2012;82:248. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01755.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nord AS, et al. STAART Psychopharmacology Network, Reduced transcript expression of genes affected by inherited and de novo CNVs in autism. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19:727. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kishi M, Pan YA, Crump JG, Sanes JR. Mammalian SAD kinases are required for neuronal polarization. Science. 2005;307:929. doi: 10.1126/science.1107403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Batsukh T, et al. CHD8 interacts with CHD7, a protein which is mutated in CHARGE syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:2858. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jongmans MC, et al. CHARGE syndrome: The phenotypic spectrum of mutations in the CHD7 gene. J Med Genet. 2006;43:306. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.036061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Feng L, Allen NS, Simo S, Cooper JA. Cullin 5 regulates Dab1 protein levels and neuron positioning during cortical development. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2717. doi: 10.1101/gad.1604207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Levy D, et al. Rare de novo and transmitted copy-number variation in autistic spectrum disorders. Neuron. 2011;70:886. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.El-Tahir HM, et al. Expression of hepatoma-derived growth factor family members in the adult central nervous system. BMC Neurosci. 2006;7:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-7-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Felder B, et al. FARP2, HDLBP and PASK are downregulated in a patient with autism and 2q37.3 deletion syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149A:952. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Talkowski ME, et al. Assessment of 2q23.1 microdeletion syndrome implicates MBD5 as a single causal locus of intellectual disability, epilepsy, and autism spectrum disorder. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:551. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Williams SR, et al. Haploinsufficiency of MBD5 associated with a syndrome involving microcephaly, intellectual disabilities, severe speech impairment, and seizures. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18:436. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Millson A, et al. Chromosomal loss of 3q26.3-3q26.32, involving a partial neuroligin 1 deletion, identified by genomic microarray in a child with microcephaly, seizure disorder, and severe intellectual disability. Am J Med Genet A. 2011 doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Glessner JT, et al. Autism genome-wide copy number variation reveals ubiquitin and neuronal genes. Nature. 2009;459:569. doi: 10.1038/nature07953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Van der Aa N, Vandeweyer G, Kooy RF. A boy with mental retardation, obesity and hypertrichosis caused by a microdeletion of 19p13.12. Eur J Med Genet. 2010;53:291. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen YH, Tsai MT, Shaw CK, Chen CH. Mutation analysis of the human NR4A2 gene, an essential gene for midbrain dopaminergic neurogenesis, in schizophrenic patients. Am J Med Genet. 2001;105:753. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Le WD, et al. Mutations in NR4A2 associated with familial Parkinson disease. Nat Genet. 2003;33:85. doi: 10.1038/ng1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Borg I, et al. Disruption of Netrin G1 by a balanced chromosome translocation in a girl with Rett syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2005;13:921. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Briant JA, et al. Evidence for association of two variants of the nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptor gene OPRL1 with vulnerability to develop opiate addiction in Caucasians. Psychiatr Genet. 2010;20:65. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e32833511f6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Williams SR, et al. Haploinsufficiency of HDAC4 causes brachydactyly mental retardation syndrome, with brachydactyly type E, developmental delays, and behavioral problems. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:219. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Borroni B, et al. Atypical presentation of a novel Presenilin 1 R377W mutation: Sporadic, late-onset Alzheimer disease with epilepsy and frontotemporal atrophy. Neurol Sci. 2012;33:375. doi: 10.1007/s10072-011-0714-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Goffin A, Hoefsloot LH, Bosgoed E, Swillen A, Fryns JP. PTEN mutation in a family with Cowden syndrome and autism. Am J Med Genet. 2001;105:521. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Herman GE, et al. Increasing knowledge of PTEN germline mutations: Two additional patients with autism and macrocephaly. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143:589. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Arch EM, et al. Deletion of PTEN in a patient with Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome suggests allelism with Cowden disease. Am J Med Genet. 1997;71:489. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19970905)71:4<489::AID-AJMG24>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Trivier E, et al. Mutations in the kinase Rsk-2 associated with Coffin-Lowry syndrome. Nature. 1996;384:567. doi: 10.1038/384567a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Merienne K, et al. A missense mutation in RPS6KA3 (RSK2) responsible for non-specific mental retardation. Nat Genet. 1999;22:13. doi: 10.1038/8719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Field M, et al. Mutations in the RSK2(RPS6KA3) gene cause Coffin-Lowry syndrome and nonsyndromic X-linked mental retardation. Clin Genet. 2006;70:509. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00723.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Taniue K, Oda T, Hayashi T, Okuno M, Akiyama T. A member of the ETS family, EHF, and the ATPase RUVBL1 inhibit p53-mediated apoptosis. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:682. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Feng Y, Lee N, Fearon ER. TIP49 regulates beta-catenin-mediated neoplastic transformation and T-cell factor target gene induction via effects on chromatin remodeling. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Budanov AV, Karin M. p53 target genes sestrin1 and sestrin2 connect genotoxic stress and mTOR signaling. Cell. 2008;134:451. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Buysse K, et al. Delineation of a critical region on chromosome 18 for the del(18)(q12.2q21.1) syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:1330. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hoischen A, et al. De novo mutations of SETBP1 cause Schinzel-Giedion syndrome. Nat Genet. 2010;42:483. doi: 10.1038/ng.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Xie P, et al. Histone methyltransferase protein SETD2 interacts with p53 and selectively regulates its downstream genes. Cell Signal. 2008;20:1671. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yang H, Sasaki T, Minoshima S, Shimizu N. Identification of three novel proteins (SGSM1, 2, 3) which modulate small G protein (RAP and RAB)-mediated signaling pathway. Genomics. 2007;90:249. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hevner RF, et al. Tbr1 regulates differentiation of the preplate and layer 6. Neuron. 2001;29:353. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yang BZ, Han S, Kranzler HR, Farrer LA, Gelernter J. A genomewide linkage scan of cocaine dependence and major depressive episode in two populations. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:2422. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Huang X, Langelotz C, Hetfeld-Pechoc BK, Schwenk W, Dubiel W. The COP9 signalosome mediates beta-catenin degradation by deneddylation and blocks adenomatous polyposis coli destruction via USP15. J Mol Biol. 2009;391:691. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.06.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tian C, et al. KRAB-type zinc-finger protein Apak specifically regulates p53-dependent apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:580. doi: 10.1038/ncb1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.