Abstract

Background

Knee stiffness or limited range of motion (ROM) after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) may compromise patient function. Patients with stiffness are usually managed with manipulation under anesthesia (MUA) to improve ROM. However, the final ROM obtained is multifactorial and may depend on factors such as comorbidities, implant type, or the timing of MUA.

Questions/purposes

We asked whether diabetes mellitus, implant type, and the interval between TKA and MUA influenced post-MUA ROM.

Methods

From a group of 2462 patients with 3224 TKAs performed between 1999 and 2007 we retrospectively reviewed 96 patients with 119 TKAs (4.3%) who underwent MUA. We determined the presence of diabetes mellitus, implant type, and the interval between TKA and MUA.

Results

The average increase in ROM after MUA was 34°. Patients with diabetes mellitus experienced lower final ROM after MUA (87.5° versus 100.3°) as did patients with cruciate-retaining (CR) prostheses versus posterior-stabilized (92.3° versus 101.6°). The interval between TKA and MUA inversely correlated with final ROM with a decrease after 75 days.

Conclusions

Most patients experience improvements in ROM after MUA. Patients with diabetes mellitus or CR prostheses are at risk for lower final ROM after MUA. Manipulation within 75 days of TKA is associated with better ROM.

Level of Evidence

Level IV, therapeutic study. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

TKA alleviates pain and restores knee function. However, 1% to 6% of patients develop a variable degree of arthrofibrosis or adhesions that adversely affects knee ROM and consequently restricts daily activities [23, 25]. Although knee stiffness is a common complication after TKA, there is no universally accepted definition of stiffness. Fox and Poss defined stiffness as a failure to achieve approximately 90° of active flexion within 2 weeks after TKA [10]. Others such as Kim et al. describe stiffness as having a flexion contracture ≥ 15° and/or < 75° of flexion after TKA [15]. An individual requires 67° of knee flexion to walk normally, 83° to ascend stairs, 90° to descend stairs, 105° to get up from a chair, and 115° to get up from a sofa [14, 17]. Final ROM achieved after TKA is an important determinant of patient satisfaction and function [30].

The ROM obtained after TKA is multifactorial. The principal predictive factor of final post-TKA ROM is reportedly pre-TKA ROM [27, 28]. Pre-TKA patient characteristics such as age, race, body mass index, and comorbidities also may affect final ROM [3, 15, 30]. Patients with lower body mass indices have been associated with greater pre-TKA ROM and are less likely to require manipulation under anesthesia (MUA) to manage stiffness after TKA [11]. Patients with diabetes mellitus have lower ROM and experience more stiffness after surgery [2, 22, 31]. Intraoperative variables including type of implant, anesthesia type, cruciate, and collateral ligament balance are also potential determinants of final ROM [6, 32]. Additionally, final outcomes may depend on adequacy of perioperative anesthetic management, use of continuous passive motion, type of rehabilitation program, and patient motivation [1–3, 7, 12, 16, 24, 26, 30, 31, 33]. Furthermore, there is disagreement regarding the interval between initial TKA and MUA with some data showing that patients manipulated within 90 days achieve greater increases in ROM compared with patients at longer intervals after TKA [8, 21]. Other studies suggest patients achieve similar final ROM irrespective of interval between surgery and MUA [13, 31].

The purpose of this study was to determine (1) the effect of MUA on ROM; and (2) the influence of diabetes mellitus, prosthesis design, and timing of MUA on post-MUA ROM.

Materials and Methods

Between 1999 and 2007 we performed 3244 primary TKAs in 2782 patients. Of those, 112 patients with 140 TKAs (4.3%) underwent MUA as a result of limited ROM after TKA. The indications for MUA were: failure to obtain 90° of flexion within 6 weeks after TKA or sooner if patients were not on pace to achieve this benchmark. The contraindications to MUA were presence of: infection, fracture, hematoma presenting as stiffness, or obvious malposition of component. We excluded 16 patients (21 knees) from the study as a result of inadequate followup (less than 2 years) resulting in 96 patients with 119 TKAs. There were 72 women (75%; 90 knees) who underwent MUA (Table 1). The average age of patients in the MUA group was 63 years (range, 40–81 years). Osteoarthritis was the primary diagnosis in 90 patients (94%; 113 knees) and diabetes mellitus was diagnosed in 9% patients. The minimum followup was 2 years (average, 3 years; range, 2–12 years). No patients were recalled specifically for this study; all data were obtained from medical records including hospital charts and office notes.

Table 1.

Demographic and ROM data

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 96 |

| Number of knees | 119 |

| Average age (years) | 63 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 73% |

| Male | 27% |

| Average body mass index (kg/m2) | 32.0 |

| Race | |

| White | 78% |

| Nonwhite | 22% |

| Pre-TKA ROM | 96.5° ± 18.4° |

| Pre-MUA ROM | 64.7° ± 20.1°* |

| Final ROM | 99.2° ± 18.1°† |

* Significantly lower than pre-TKA ROM (p < 0.001); †Significantly higher than pre-MUA ROM (p < 0.001); ROM = range of motion; MUA = manipulation under anesthesia.

All TKAs were performed by fellowship-trained adult reconstructive surgeons with over 1000 TKAs performed per surgeon before the study period.

The rehabilitation protocol after TKA at our institution included mobilization with walking on postoperative day 1 with assistive devices, active and passive flexion on day 2, and hospital discharge to a skilled nursing facility when medically stable or home when ambulating independently. All inpatient physical therapy was supervised by a physical therapist in two 1-hour sessions per hospital day. After discharge, physical therapy was continued at least two times per week supervised by a physical therapist. The physical therapy regimen was standard among all patients in the investigation. Over the course of this study, the average length of hospital stay was 4 days.

Manipulation was performed under general or regional anesthesia with complete muscle relaxation provided. The hip was then flexed to 90° and the knee was bent until a firm end point was encountered. The proximal shaft of the tibia was used as the lever arm for flexion. During MUA, the ROM was determined by intraoperative long-armed goniometric measurement by the surgeon. Ice packs were immediately applied postoperatively and physical therapy started in the recovery area.

The post-MUA inpatient physical therapy consisted of active and passive supervised ROM exercises and ambulation supervised by a physical therapist. Patients underwent active and passive flexion-extension exercises until discharge from the hospital 1 day after manipulation. Outpatient physical therapy was initiated on discharge at least three times per week.

Extension and flexion measurements were performed using a long-armed goniometer by a physical therapist, orthopaedic nurse, or surgeon. For statistical analysis, the ROM arc was determined based on the difference between extension and flexion. Extension and flexion were measured before TKA, before MUA, at the time of MUA, and at most recent followup. Final ROM was defined as the arc of motion measured at most recent patient followup.

The data were retrospectively collected from clinical, intraoperative, and anesthesia notes. Race was classified as white or nonwhite. We evaluated the charts for a prior diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Prosthesis type included cruciate retaining (CR) or posterior stabilized (PS). The timing of MUA was analyzed based on five intervals: within 45, 46 to 60, 61 to 75, 76 to 90, and more than 90 days between TKA and MUA.

To test the effect of MUA on ROM, we used a paired t-test comparing pre- and post-MUA ROM. The influence of race, diabetes mellitus, prosthesis design, and timing of MUA on post-MUA ROM was tested using Pearson’s chi square for discrete variables or two-sample t-tests for continuous variables. To test the independent effects of these variables, we used a stepwise linear regression model with backward selection and p > 0.20 for removal from the model. All tests were conducted using STATA 12 (Stata Statistical Software: Release 12; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Patients experienced increases in ROM after MUA with a mean increase of 34° (p < 0.001). Patients undergoing manipulation had improvements (p < 0.001) in final flexion contracture measurements as compared with pre-TKA flexion contracture values (Table 1). However, pre-TKA and final flexion values were similar (p = 0.88) (Table 2). Patients experienced improvements in both flexion contracture and flexion after MUA (p < 0.001) (Table 3). Furthermore, intra-MUA ROM correlated with (r = 0.18, p = 0.06) final ROM.

Table 2.

Comparison of Pre-TKA flexion and flexion contracture

| Variable | Pre-TKA value | Final value | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexion contracture | 4.4° ± 6.2° | 1.9° ± 3.9° | < 0.001 |

| Flexion | 100.3° ± 17.5° | 100.6° ± 17.5° | 0.88 |

Table 3.

Comparison of pre-MUA flexion and flexion contracture

| Variable | Pre-MUA value | Final value | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexion contracture | 5.3° ± 6.8° | 1.9° ± 3.9° | < 0.001 |

| Flexion | 69.6° ± 18.2° | 100.6° ± 17.5° | < 0.001 |

MUA = manipulation under anesthesia.

Nonwhite patients had lower (p < 0.001) final ROM as compared with whites. Diabetes mellitus was independently associated with (p = 0.03) lower mean ROM after TKA. The proportion of CR versus PS implants was similar (r = 0.37, p = 0.32) during the study period. However, CR prostheses demonstrated lower final ROM (p = 0.02) than PS (92.3° compared with 101.5°) after MUA (Table 4). Multivariate analysis evaluating race, diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, and use of CR versus PS implants demonstrated lower ROM in patients with diabetes mellitus and those with CR prostheses (Table 5).

Table 4.

Univariate analysis of variables predictive of ROM after MUA

| Variable | Post-MUA ROM | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Race | < 0.001 | |

| White | 101.7° ± 17.1° | |

| Nonwhite | 89.8° ± 19.0° | |

| Diabetes | 0.03 | |

| Patients with diabetes | 87.5° ± 22.8° | |

| Patients without diabetes | 100.3° ± 17.2° | |

| Implant type | 0.02 | |

| Cruciate retaining | 92.3° ± 20.0° | |

| Posterior stabilized | 101.6° ± 16.9° |

ROM = range of motion; MUA = manipulation under anesthesia.

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis of variables predictive of ROM after MUA

| Variable | Correlation coefficient | 95% confidence interval | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes mellitus | −11.9 | −19.1 to −4.7 | 0.04 |

| Cruciate-retaining implant | −13.1 | −24.0 to −2.2 | 0.007 |

ROM = range of motion; MUA = manipulation under anesthesia.

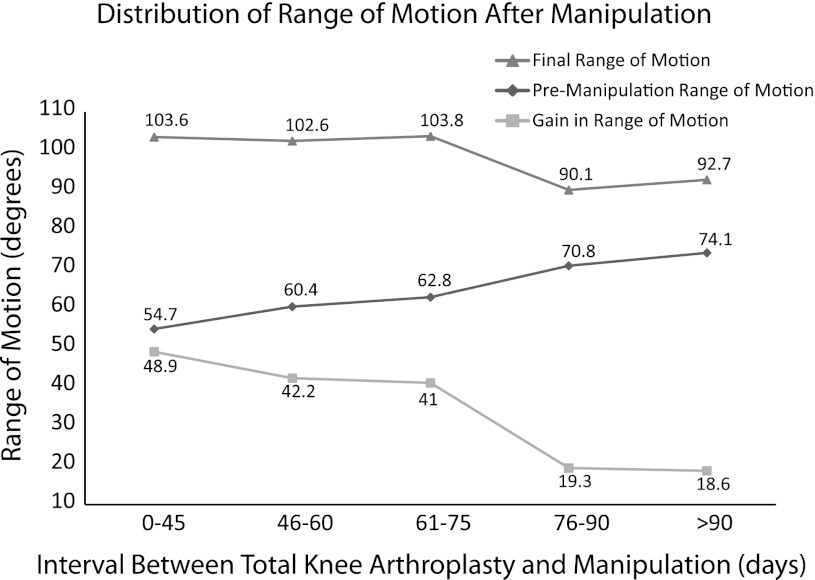

The mean interval between TKA and MUA was 74 days. An improvement (p = 0.001) in ROM was observed in knees manipulated within 75 days after surgery versus knees manipulated after 75 days (103° as compared with 92°). The interval between TKA to MUA negatively correlated (r = −0.20, p = 0.04) with final ROM. A linear regression analysis controlling for pre-MUA ROM demonstrated a 0.21° decrease in final ROM for each day between TKA and MUA (Fig. 1). We found a higher (all p < 0.05) final ROM and post-MUA gain in the 61- to 75-day interval as compared with the 76- to 90-day interval (Fig. 1; Table 6).

Fig. 1.

Final, pre-MUA, and gain in ROM based on followup intervals between TKA and MUA are shown.

Table 6.

Comparison of the time interval between TKA and MUA

| Interval (days) | 0−45 | 46−60 | 61−75 | 76−90 | > 90 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final ROM | 103.6° | 102.6° | 103.8° | 90.1° | 92.7° |

| Increase in flexion after MUA | 45.7° | 38.4° | 39° | 16.8° | 14.1° |

| p value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Improvement in flexion contracture after MUA | 3.2° | 3.8° | 2° | 2.4° | 4.5° |

| p value | 0.02 | 0.0006 | 0.1 | 0.18 | 0.02 |

MUA = manipulation under anesthesia; ROM = range of motion.

Discussion

Previous studies on the outcome of MUA after TKA have demonstrated many variables, which appear to correlate with final ROM [13, 15]. However, a number of controversies remain. We therefore determined (1) the effect of MUA on ROM; and (2) the influence of diabetes mellitus, prosthesis design, and timing of MUA on post-MUA ROM.

Our investigation was subject to a number of limitations. First, because the study was retrospective, the data relied on accurate examinations and recordkeeping and assumed all measurements were made in a uniform way. The ROM measurements were performed using a long-armed goniometer by experienced physicians and physician assistants in our joint replacement division. Previous studies have demonstrated the accuracy of long-armed goniometric knee measurements; however, inconsistencies in measurement were possible [18]. Nevertheless, intra- and interobserver reliability is reportedly high with goniometric evaluation of knee flexion and extension [4]. Group comparisons such as this one have greater accuracy and reliability over time when compared with individual measurements [19]. Correlation coefficients of intratester measurements of flexion and extension when using goniometers were reported to be 0.99 and 0.98, respectively. Similarly, intertester goniometric reliability of flexion and extension is on the order of 0.90 and 0.86 for flexion and extension, respectively [34]. Second, complete knee scores were unavailable for 34 of the 96 patients in the study and therefore were omitted from the analysis. Because ROM is an objective measure that indirectly indicates function, this was the primary outcome evaluated.

The rate of MUA and resulting mean improvement in ROM of 34° is consistent with previous studies showing similar results [9, 13, 20] (Table 7). These increases in ROM were mostly attributed to increases in flexion with moderate improvements in extension. Patients were followed for an average of 3.1 years. Because minimal increases in ROM occur more than 1 year after TKA, this followup was adequate at capturing true end points of ROM and function [9, 33]. As previously described, this study also demonstrated a strong association between pre-TKA and final ROM [27, 28]. Consequently, patients with low initial ROM should be informed that pre-TKA ROM is predictive of final ROM [13, 27, 28, 35]. Final post-MUA flexion regressed toward pre-TKA flexion as demonstrated by nearly equivalent flexion arcs (100.3° versus 100.6°). Comorbidities may prognosticate final ROM after TKA [2, 11, 30]. In this study, patients with diabetes mellitus experienced 12.8° lower final ROM versus patients without diabetes mellitus.

Table 7.

Comparison of previous investigations of MUA after TKA

| Study | Year | Number of knees | Number of patients | Type of prosthesis | MUA rate | Change in ROM after MUA | Mean interval between TKA and MUA (days) | Mean followup (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daluga et al. [8] | 1991 | 94 | 60 | PS | 12.0% | 42° | – | 34.8 |

| Esler et al. [9] | 1999 | 47 | 42 | CR | 9.9% | 35° | 79 | – |

| Fox and Poss [10] | 1981 | 76 | – | CR, PS, unicondylar, bicompartmental | 23.0% | 30° | 14 | 12 |

| Keating et al. [13] | 2007 | 113 | 90 | CR | 1.8% | 35° | – | 55.2 |

| Maloney [20] | 2002 | 24 | – | PS | 11.2% | 47° | 51 | – |

| Scranton [31] | 2001 | 19 | 19 | PS | 10.8% | 42° | – | – |

| Yercan et al. [35] | 2006 | 46 | 46 | PS | 4.0% | 47° | 30 | 31 |

| Current study | 2012 | 119 | 96 | PS, CR | 4.3% | 34° | 71 | 36 |

MUA = manipulation under anesthesia; ROM = range of motion; PS = posterior stabilized; CR = cruciate retaining.

The degree of prosthesis constraint may predict the response to MUA. We found the mean ROM was higher among PS versus CR prostheses (101.5° compared with 92.3°) post-MUA. Other studies have reported similar ROM in both PS and CR prostheses [5] (Table 7). However, we believe the intact posterior cruciate ligament or its improper balance could limit the knee ROM arc in CR prostheses and therefore explain the decreased improvement in ROM after MUA.

The literature with respect to timing of MUA after TKA contains contradictory findings [8, 13, 21, 31]. Some studies suggest patients manipulated within 90 days achieve greater increases in ROM compared with patients at longer intervals after TKA [8, 21], whereas others show patients achieve similar final ROM irrespective of the interval between surgery and MUA (Table 7). Similar to our observations, Keating et al. identified a mean pre-MUA flexion of 70° with an overall mean increase of 35° of flexion after MUA [13]. Moreover, a study of early versus late MUAs reported improvements in flexion among patients manipulated before 90 days (68.4° ± 17.2° to 101.4° ± 16.2°) with smaller improvements at intervals greater than 90 days (81.0° ± 13.3° to 98.0° ± 18.0°) [21]. These investigations used a two-sample model to compare ROM among patients before and after 90 days and failed to find a significant difference with respect to timing. Our analysis differed in that we used a linear regression analysis demonstrating a negative correlation between time interval and final ROM. Our linear regression analysis that controlled for pre-TKA ROM identified a loss of 0.21° per day between initial surgery and MUA. The mean time between TKA and MUA was 74 days. Although our protocol is to manipulate at 6 weeks post-TKA, patient factors adversely affected adherence to this regimen. Moreover, there was a higher final ROM associated with MUA before 75 days. We subsequently evaluated the ROM with respect to five different time intervals based on expected patient followup patterns. We found a higher final ROM and post-MUA gain of ROM in the 61- to 75-day interval as compared with the 76- to 90-day interval (Fig. 1). We believe these findings should be considered when counseling patients before MUA.

The stiff TKA remains both a diagnostic and therapeutic conundrum. Like previous investigations, our study identified an average benefit of 34° after knee manipulation [13]. Likewise, medical comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus are associated with worse motion and manipulation after TKA [29, 31]. On the other hand, in our study, patients with CR prostheses achieved less ROM after MUA than patients with PS knees. Although ROM after uncomplicated primary TKA is similar with PS and CR implants, additional investigation may clarify the role of the posterior cruciate ligament in the stiff knee. Finally, the timing of manipulation after TKA has been controversial with most authors publishing no major differences between early and late manipulations [13, 31]. However, this study differed from others in that a linear regression analysis identified a per-day loss of ROM and poorer results after 74 days in terms of final ROM.

Patients with stiffness after TKA experience increased final ROM after MUA after TKA. Furthermore, patients with diabetes mellitus, CR prostheses, and greater intervals between TKA and MUA may experience compromises in final ROM.

Acknowledgments

We thank William Petersilge, MD, for contributing patients to the study and Patricia Conroy-Smith for help with data collection.

Footnotes

One of the authors (VMG) certifies that he has received payments or benefits, in any one year, an amount in excess of $1,000,000 from Zimmer (Warsaw, IN, USA) related to this work.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA-approval status, of any drug or device prior to clinical use.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

References

- 1.Babis GC, Trousdale RT, Pagnano MW, Morrey BF. Poor outcomes of isolated tibial insert exchange and arthrolysis for the management of stiffness following total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:1534–1536. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200110000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolognesi MP, Marchant MH, Jr, Viens NA, Cook C, Pietrobon R, Vail TP. The impact of diabetes on perioperative patient outcomes after total hip and total knee arthroplasty in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bong MR, Di Cesare PE. Stiffness after total knee arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2004;12:164–171. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200405000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brosseau L, Balmer S, Tousignant M, O’Sullivan JP, Goudreault C, Goudreault M, Gringras S. Intra- and intertester reliability and criterion validity of the parallelogram and universal goniometers for measuring maximum active knee flexion and extension of patients with knee restrictions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:396–402. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.19250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaudhary R, Beaupre LA, Johnston DW. Knee range of motion during the first two years after use of posterior cruciate-stabilizing or posterior cruciate-retaining total knee prostheses. A randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:2579–2586. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christensen CP, Crawford JJ, Olin MD, Vail TP. Revision of the stiff total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17:409–415. doi: 10.1054/arth.2002.32105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coutts RD, Engh GA, Mayor MB, Whiteside LA, Wilde AH. The painful total knee replacement and the influence of component design. Contemp Orthop. 1994;28(523–536):541–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daluga D, Lombardi AV, Jr, Mallory TH, Vaughn BK. Knee manipulation following total knee arthroplasty. Analysis of prognostic variables. J Arthroplasty. 1991;6:119–128. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(11)80006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esler CN, Lock K, Harper WM, Gregg PJ. Manipulation of total knee replacements. Is the flexion gained retained? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81:27–29. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.81B1.8848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fox JL, Poss R. The role of manipulation following total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63:357–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gadinsky NE, Ehrhardt JK, Urband C, Westrich GH. Effect of body mass index on range of motion and manipulation after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26:1194–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawamura H, Bourne RB. Factors affecting range of flexion after total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Sci. 2001;6:248–252. doi: 10.1007/s007760100043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keating EM, Ritter MA, Harty LD, Haas G, Meding JB, Faris PM, Berend ME. Manipulation after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:282–286. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kettelkamp DB. Gait characteristics of the knee: normal, abnormal, and postreconstruction. Americam Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons: Symposium on Reconstructive Surgery of the Knee. 1976:47–57.

- 15.Kim J, Nelson CL, Lotke PA. Stiffness after total knee arthroplasty. Prevalence of the complication and outcomes of revision. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:1479–1484. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.86B7.15255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lau SKK, Chiu KY. Use of continuous passive motion after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:336–339. doi: 10.1054/arth.2001.21453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laubenthal KN, Smidt GL, Kettelkamp DB. A quantitative analysis of knee motion during activities of daily living. Phys Ther. 1972;52:34–43. doi: 10.1093/ptj/52.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lavernia C, D’Apuzzo M, Rossi MD, Lee D. Accuracy of knee range of motion assessment after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lenssen AF, van Dam EM, Crijns YH, Verhey M, Geesink RJ, van den Brandt PA, de Bie RA. Reproducibility of goniometric measurement of the knee in the in-hospital phase following total knee arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8:83. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-8-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maloney WJ. The stiff total knee arthroplasty: evaluation and management. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17:71–73. doi: 10.1054/arth.2002.32450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Namba RS, Inacio M. Early and late manipulation improve flexion after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:58–61. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Namba RS, Paxton L, Fithian DC, Stone ML. Obesity and perioperative morbidity in total hip and total knee arthroplasty patients. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nelson CL, Kim J, Lotke PA. Stiffness after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(Suppl 1):264–270. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E-00345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papagelopoulos PJ, Sim FH. Limited range of motion after total knee arthroplasty: etiology, treatment, and prognosis. Orthopedics. 1997;20:1061–1065. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19971101-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pariente GM, Lombardi AV, Jr, Berend KR, Mallory TH, Adams JB. Manipulation with prolonged epidural analgesia for treatment of TKA complicated by arthrofibrosis. Surg Technol Int. 2006;15:221–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pope RO, Corcoran S, McCaul K, Howie DW. Continuous passive motion after primary total knee arthroplasty—does it offer any benefits? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79:914–917. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.79B6.7516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ritter MA, Campbell ED. Effect of range of motion on the success of a total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1987;2:95–97. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(87)80015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ritter MA, Stringer EA. Predictive range of motion after total knee replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;143:115–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schiavone Panni A, Cerciello S, Vasso M, Tartarone M. Stiffness in total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Traumatol. 2009;10:111–118. doi: 10.1007/s10195-009-0054-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schurman DJ, Parker JN, Ornstein D. Total condylar knee replacement. A study of factors influencing range of motion as late as two years after arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67:1006–1014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scranton PE., Jr Management of knee pain and stiffness after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:428–435. doi: 10.1054/arth.2001.22250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scuderi GR. The stiff total knee arthroplasty: causality and solution. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:23–26. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shoji H, Solomonow M, Yoshino S, D’Ambrosia R, Dabezies E. Factors affecting postoperative flexion in total knee arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 1990;13:643–649. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19900601-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watkins MA, Riddle DL, Lamb RL, Personius WJ. Reliability of goniometric measurements and visual estimates of knee range of motion obtained in a clinical setting. Phys Ther. 1991;71:90–96. doi: 10.1093/ptj/71.2.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yercan HS, Sugun TS, Bussiere C, Ait Si Selmi T, Davies A, Neyret P. Stiffness after total knee arthroplasty: prevalence, management and outcomes. Knee. 2006;13:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]