Abstract

Synthetic lethal screening is a chemical biology approach to identify small molecules that selectively kill oncogene-expressing cell lines with the goal of identifying pathways that provide specific targets against cancer cells. We performed a high-throughput screen of 303,282 compounds from the National Institutes of Health-Molecular Libraries Small Molecule Repository (NIH-MLSMR) against immortalized BJ fibroblasts expressing HRASG12V followed by a counterscreen of lethal compounds in a series of isogenic cells lacking the HRASG12V oncogene. This effort led to the identification of two novel molecular probes (PubChem CID 3689413, ML162 and CID 49766530, ML210) with nanomolar potencies and 4–23 fold selectivities, which can potentially be used for identifying oncogene-specific pathways and targets in cancer cells.

Keywords: RAS oncogene, Synthetic lethal, α-chloroamide, Nitroisoxazole, MLPCN probes

The first rat sarcoma (RAS) oncogene was discovered as a genetic element from the Harvey and Kirsten rat sarcoma viruses with the ability to immortalize mammalian cells [1,2,3]. Mutated RAS oncogenes (i.e., HRAS, NRAS, and KRAS) are found in 10–20% of all human cancers and hence are attractive targets for drug development. Despite significant efforts [4], currently there are no drugs directly targeting mutated RAS oncogenes. Thus, several modes of indirect approaches have emerged for targeting RAS including the use of synthetic lethality.

Synthetic lethal screening is a chemical biology approach to identify small molecules that selectively kill oncogene-expressing cell lines with the goal of identifying pathways that provide specific targets against cancer cells. Two distinct approaches have been investigated for identifying compounds exhibiting RAS synthetic lethality. In the first approach, RNAi screens led to the identification of RAS synthetic lethal genes such as TBK1, CCNA2, KIF2C, PLK1, APC/C, CDK4, and STK33 [5,6,7,8,9]. Disappointingly, small molecules that target the encoded proteins have not been found to show the same pattern of synthetic lethality [10]. In the second approach, phenotypic screens have been used to identify inhibitors that are selectively lethal to cell lines expressing a RAS oncogene. This approach necessitates further studies to identify the target, but nonetheless is an alternative approach towards identifying small molecules with novel cellular properties.

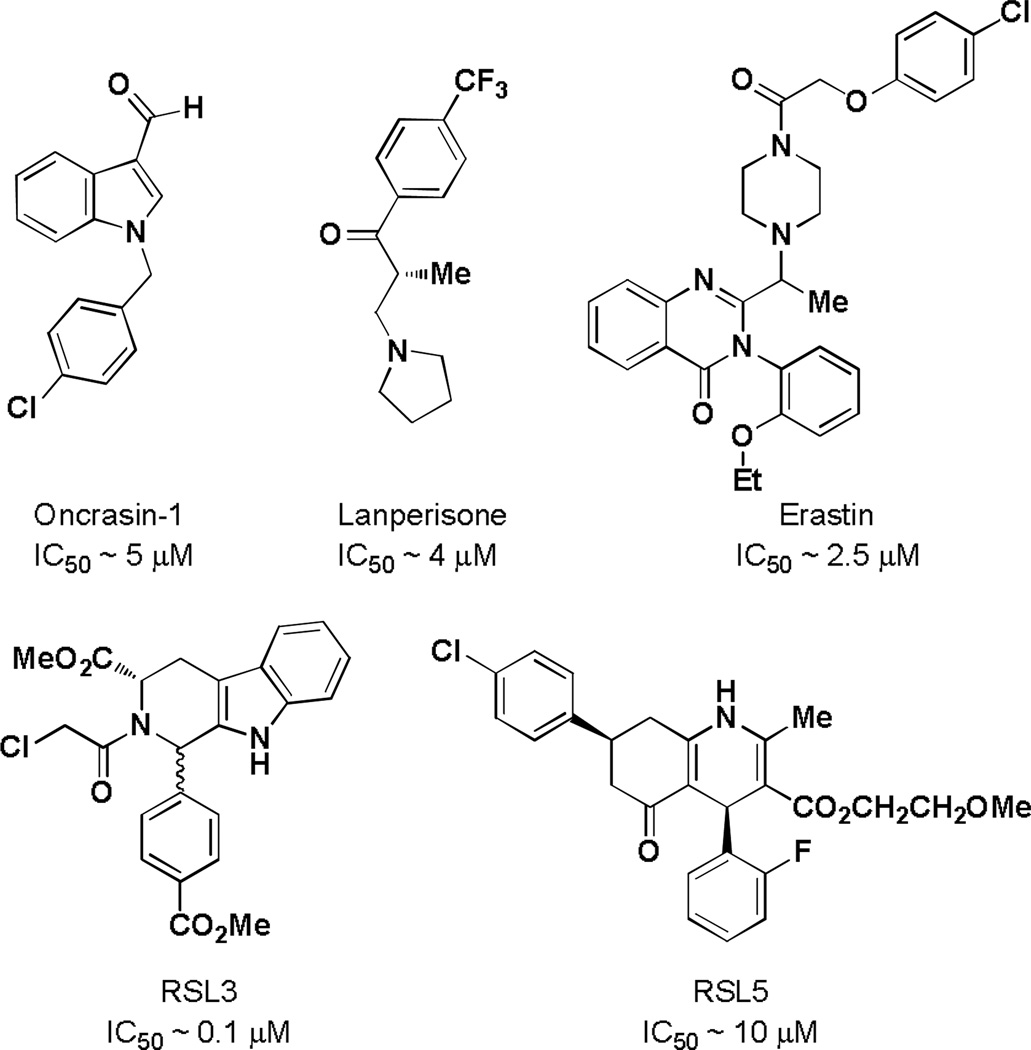

Using a phenotypic approach, Guo and colleagues identified oncrasin-1 (Figure 1), which is selectively toxic to cell lines harboring a KRAS oncogene and ineffective in HRAS mutant cell lines [11]. More recently, Shaw et al. reported a synthetic lethal screen using mouse embryonic fibroblast harboring an oncogenic KRASG12D allele and identified lanperisone (Figure 1) as the most promising candidate [4]. Stockwell and colleagues have identified inhibitors (erastin, RSL3 and RSL5, Figure 1) that are synthetically lethal with cell lines expressing mutant HRAS and KRAS [12,13]. In this paper, we describe the discovery and development of novel molecular probes exhibiting RAS synthetic lethality that could be used to identify new pathways and targets for the development of novel cancer therapeutics [14].

Figure 1.

Previously reported small molecules that are lethal to RAS mutant cell lines.

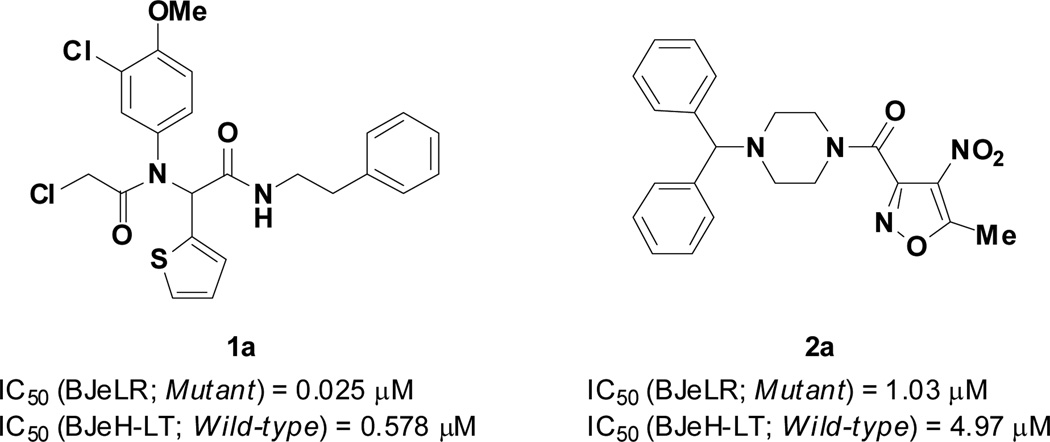

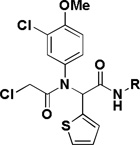

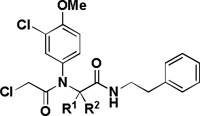

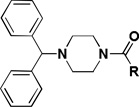

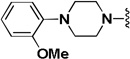

A high-throughput screen using the National Institutes of Health-Molecular Libraries Small Molecule Repository (NIH-MLSMR) comprising 303,282 compounds (PubChem AID 1832) was performed. Hits were triaged based on activities on four cell lines: BJeLR (expressing HRASG12V), BJeH-LT (isogenic to BJeLR without HRASG12V), DRD (expressing HRASG12V with alternative oncogenic constructs), BJeH (immortalized background cell line) [15]. The hits that emerged from these secondary screens were evaluated for cell viability, which led to the identification of 73 compounds that had IC50 < 2.5 µM against BJeLR and > 4-fold selectivity against the isogenic BJeH-LT cell line. Two hit clusters, an α-chloroacetamide and a nitroisoxazole, were identified and prioritized for optimization. The structures of lead compounds (1a and 2a) from the two series are shown in Figure 2 and the structure/activity relationships (SAR) of these two lead compounds are the subject of this paper.

Figure 2.

Hit compounds from the high throughput screening campaign.

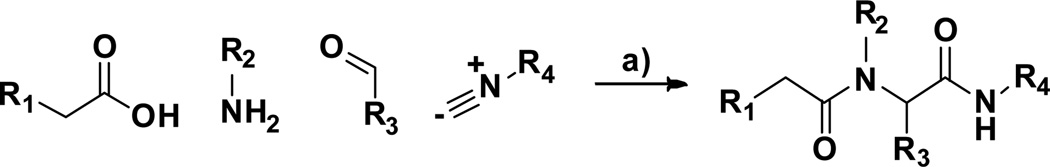

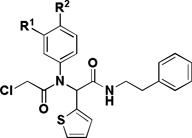

The first cluster represented by compound 1a features an α-chloroacetamide that can potentially act as an electrophile. Although covalent inhibitors are rarely considered when initiating a drug discovery program, they have proved to be successful in various disease areas [16,17]. Particularly, in the context of phenotypic screens, where the target is unknown, covalent inhibitors can facilitate target identification through pull-down experiments. RSL3, a previously reported RAS synthetic lethal molecule is also an α-chloroacetamide with an IC50 of 100 nM in BJeLR and approximately 8-fold selectivity vs BJeH-LT [14]. Compound 1a also possesses a α-chloroamide sub-unit but shows increased activity and selectivity compared to RSL3 and was thus considered a superior scaffold for SAR studies. To investigate the SAR of 1a, several analogs were synthesized using the Ugi 4-component reaction (Scheme 1). The influence of all four components was investigated, and the results are presented in Tables 1–3.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of α-chloroamide analogs using the Ugi 4-component reaction. Reagent and conditions: a) MeOH, 23 °C, 48 h.

Table 1.

SAR of the aniline portion

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | R1 | R2 | IC50 (µM)a | Selectivityb | |

| BJeLR | BJeH-LT | ||||

| 1a | Cl | OMe | 0.025 | 0.578 | 23 |

| 1f | H | OMe | 0.22 | 1.7 | 7.8 |

| 1g | Cl | H | 0.156 | 0.331 | 2.1 |

| 1h | OMe | H | 0.17 | 2.4 | 14 |

Values are means of experiments performed in triplicate.

BJeH-LT IC50/BJeLR IC50.

Table 3.

SAR of the phenethylamine portion

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | R | IC50 (µM)a | Selectivityb | |

| BJeLR | BJeH-LT | |||

| 1a |  |

0.025 | 0.578 | 23 |

| 1o |  |

0.113 | 0.27 | 2.4 |

| 1p | 0.075 | 0.179 | 2.4 | |

| 1q |  |

0.089 | 0.208 | 2.3 |

| 1r |  |

0.102 | 0.242 | 2.4 |

Values are means of experiments performed in triplicate.

BJeH-LT IC50/BJeLR IC50.

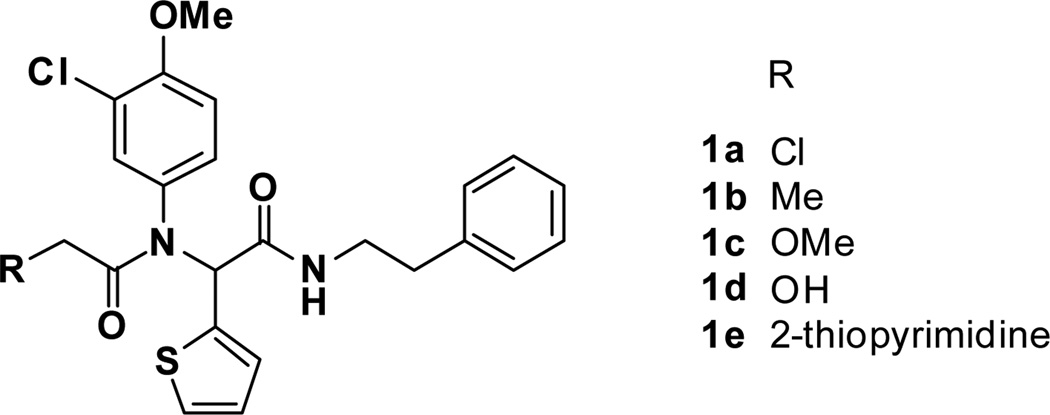

Our initial goal was to determine if the α-chloroamide moiety was essential for activity. Thus, analogs where the chloro functional group of 1a was replaced with a methyl, a methoxy, a hydroxyl moiety, and a heterocyclic leaving group [18] (1b–e, Figure 3) were prepared. All of these analogs were found to be inactive, suggesting that the α-chloroamide moiety is required for activity.

Figure 3.

SAR on the α-chloroamide portion.

In order to assess the stability of 1a as a nonselective akylating agent, it was subjected to the presence of glutathione (GSH). After 48 hours of incubation of 1a in PBS/DMSO (1/2) at room temperature, in the presence of a physiologically relevant amount of GSH (5 mM), only 20% of the corresponding GSH adduct was observed. This indicates that 1a is not highly reactive toward thiols and is relatively stable in the presence of nucleophiles such as GSH. When a base (triethylamine) was added, the formation of the GSH adduct was observed in 1 hour.

Compound 1a is a racemate and was thus, subjected to chiral HPLC separation to investigate the importance of the stereogenic center on activity and selectivity. Both enantiomers were obtained with > 99% ee (see supporting information) and were tested in the cell assays. They were shown to have similar activity and selectivity for HRASG12V cell lines. To establish whether the enantiomers could racemize under the assay conditions, each enantiomer was subjected to a PBS stability assay. After 48 hours incubation in PBS (0.1% DMSO), the stereochemical integrity of the compound was assessed by chiral HPLC/MS. No detectable racemization was observed (see supporting information). Given these results, all analogs prepared for SAR studies were synthesized as racemates.

The influence of the substitution on the aniline ring was then examined (Table 1). Both the meta-chloro substitutent and the para-methoxy substitutent were found to be critical for activity, as removal of either one led to a 10-fold decrease in activity (1f–g). A meta-methoxy (1h) led to a decrease in activity.

Different aldehydes were used in the Ugi reaction to investigate the SAR at the thiophene position (Table 2). Replacing the thiophene ring with hydrophobic group such as a cyclohexyl or an isopropyl group (1i–j) led to a decrease in activity and selectivity. The thiophene was also replaced with a thiazole (1k) or a 2-chlorothiophene (1l) in order to deactivate the 3-position. The thiazole analog 1k was shown to be inactive, but the 2-chlorothiophene analog 1l was found to be very potent with an IC50 of 61 nM in BJeLR cell line. However, its selectivity was only 2.2-fold. The thiophene ring was removed in order to address the presence of a stereogenic center in the molecule. Acetone or formaldehyde was used in the Ugi reaction in order to generate the gem-dimethyl moiety (1m) or a methylene moiety (1n), respectively, in place of the thiophene substituent. The gem-dimethyl analog (1m) was equipotent to the initial hit (1a) with an IC50 of 58 nM in BJeLR cell line but lacked the selectivity. Compound 1n showed decrease in potency and selectivity.

Table 2.

SAR on the thiophene portion

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | R1 | R2 | IC50 (µM)a | Selectivityb | |

| BJeLR | BJeH-LT | ||||

| 1a | H | 0.025 | 0.578 | 23 | |

| 1i | H | 0.505 | 1.18 | 2.3 | |

| 1j | H | 0.895 | 1.3 | 1.5 | |

| 1k |  |

H | 8.26 | 19.8 | 2.4 |

| 1l |  |

H | 0.061 | 0.133 | 2.2 |

| 1m | Me | Me | 0.058 | 0.127 | 2.2 |

| 1n | H | H | 0.231 | 0.531 | 2.3 |

Values are means of experiments performed in triplicate.

BJeH-LT IC50/BJeLR IC50.

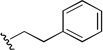

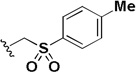

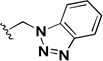

The influence of the phenethylamine portion of the hit compound was investigated by using different isocyanide components in the Ugi reaction (Table 3). Replacement of the phenethylamine group by shorter hydrophobic amines (1o–p) afforded potent compound but the selectivity was eroded.

In addition to investigating the SAR, attempts were made to improve the aqueous solubility of 1a by the introduction of a sulfone group (1q). Although this approach improved the aqueous solubility (16 µM vs <1 µM) it led to a decrease in activity and a 10-fold reduction in selectivity. Introduction of a benzotriazole group (1r) did not improve solubility and also led to a decrease in activity and selectivity.

Compound 1a was found to be the most potent and selective analog in the series. The α-chloroamide portion is required for activity, and the 3-chloro-4-methoxyaniline, the thiophene ring and the phenethylamine portion were found to be optimal for activity and selectivity. Both activity and selectivity of 1a were confirmed using another pair of HRAS-mutant and wild-type cell lines; HRASG12V cell line (DRD, IC50 = 34 nM) and HRAS wild-type cell line (BJeH, IC50 = 2400 nM).

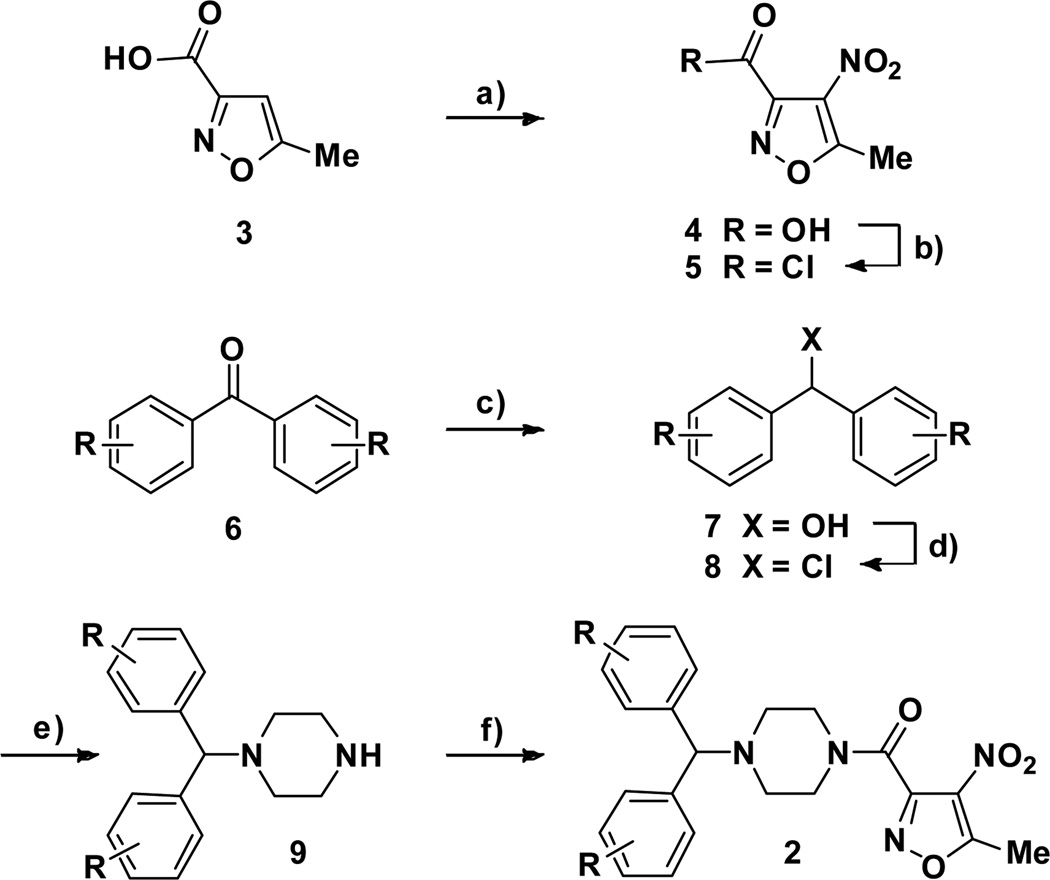

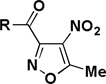

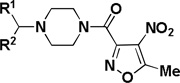

The SAR of the second cluster, the nitroisoxazole hit 2a (Figure 2), was then investigated. The synthesis of the analogs was accomplished in six steps using the general scheme developed for the synthesis of 2a (Scheme 2). Nitration of the 5-methylisoxazole-3-carboxylic acid 3 was accomplished using concentrated sulfuric acid and potassium nitrate. The obtained compound 4 was converted to the corresponding acid chloride 5 in quantitative yield. Benzophenone derivatives 6 were reduced using sodium borohydride to the corresponding alcohol 7. Treatment of 7 with oxalyl chloride provided 8 and was followed by treatment with an excess of piperazine in refluxing acetonitrile to afford 9. Coupling of secondary amines 9 with the acid chloride 5 in dichloromethane afforded the final compounds 2.

Scheme 2.

Representative synthesis of the nitroisoxazole compounds 2. Reagent and conditions: a) H2SO4, KNO3; b) Oxalyl chloride, CH2Cl2; c) NaBH4, THF/MeOH 1/1; d) Oxalyl chloride, CH2Cl2; e) Piperazine, CH3CN; f) 5, CH2Cl2.

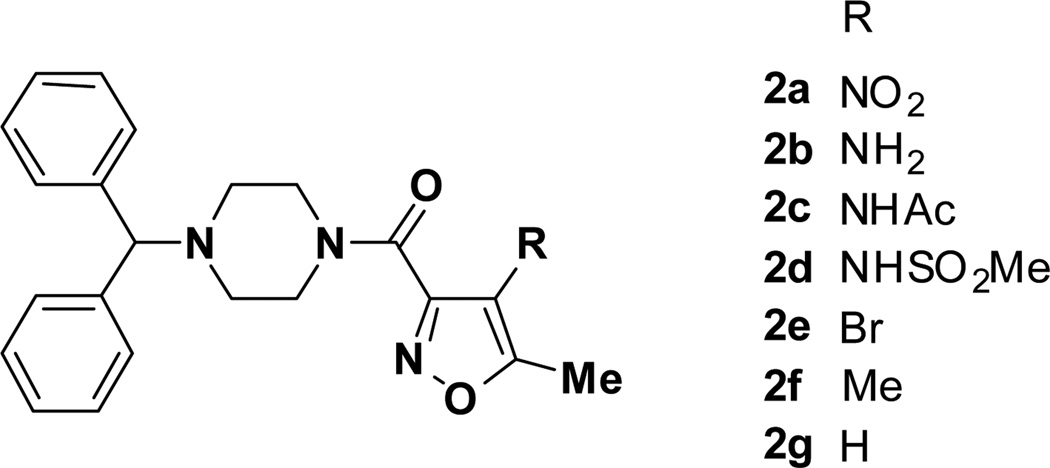

Even though the nitro group is present in several FDA-approved drugs, it can be a liability in many instances [16]. Thus, an attempt was made to replace the nitro group with other functional groups (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

SAR at the 4-position of the nitroisoxazole ring.

Replacement of the nitro group by a primary amine, acetamide, sulfonamide, bromine, methyl, and hydrogen (2b–g, Figure 3) led to inactive compounds, suggesting the importance of the nitro group for activity.

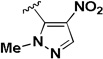

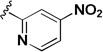

The influence of the nitroisoxazole ring on the activity of the compound (Table 4) was addressed. Replacing the nitroisoxazole ring with other nitroaromatics, such as 4-nitropyrazole (2h–j), led to inactive compounds. A nitropyridyl analog (2k) was found to be a weak inhibitor and demonstrated poor selectivity. Nitrophenyl (2l), as well as a nitrofuran analog (2m) were also found to be inactive. Thus, the nitroisoxazole moiety of the molecule was found to be important for activity and was conserved intact for further SAR studies.

Table 4.

SAR on the nitroisoxazole portion

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | R | IC50 (µM)a | Selectivityb | |

| BJeLR | BJeH-LT | |||

| 2a |  |

1.03 | 4.97 | 4.8 |

| 2h |  |

IA | IA | NAc |

| 2i |  |

IA | IA | NA |

| 2j |  |

IA | IA | NA |

| 2k |  |

37.3 | 49.7 | 1.33 |

| 2l |  |

IA | IA | NA |

| 2m | IA | 18.9 | NA | |

Values are means of experiments performed in triplicate.

BJeH-LT IC50/BJeLR IC50.

IA = Inactive, highest concentration tested was 20 µg/ml.

NA = Not applicable

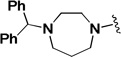

The influence of the benzhydryl-piperazine portion of the molecule was then investigated (Table 5). Replacing the benzhydryl-piperazine portion with morpholine (2n) or a shorter amide like the p-fluorobenzyl analog (2o) provided inactive compounds. Keeping the piperazine ring in place and only replacing the benzhydryl portion with an ethylcarbamate (2p) or an o-methoxyphenyl ring (2q) also led to inactive compounds. Even the removal of one of the two phenyl rings of 2a (2r) was sufficient to eliminate activity demonstrating that the benzhydryl portion is necessary for activity. Replacing the piperazine linker with homopiperazine (2s) led to a modest improvement in activity but also resulted in a modest decrease in selectivity. Hence, suggesting that homopiperazine is tolerated at that position. The ethylene diamine analog (2t) afforded a dramatic decrease in activity indicating the importance of rigidity in this quadrant as well as the importance of hydrogen bonding acceptors.

Table 5.

SAR on the benzhydrylpiperazine portion

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | R | IC50 (µM)a | Selectivityb | |

| BJeLR | BJeH-LT | |||

| 2a | 1.03 | 4.97 | 4.8 | |

| 2n | IA | IA | NA | |

| 2o | IA | IA | NA | |

| 2p | IA | IA | NA | |

| 2q |  |

IA | IA | NA |

| 2r | IA | IA | NA | |

| 2s |  |

0.773 | 2.79 | 3.6 |

| 2t | 21.6 | IA | NA | |

Values are means of experiments performed in triplicate.

BJeH-LT IC50/BJeLR IC50.

IA = Inactive, highest concentration tested was 20 µg/ml.

NA = Not applicable

To improve activity and solubility of the lead, the substitution on both phenyl ring of the benzhydryl group was studied (Table 6). Replacement of both phenyl groups by 2-pyridyl (2u) or 4-pyridyl groups (2v) increased aqueous solubility to afford analogs with solubility greater than 500 µM. Unfortunately, both of these compounds were found to be inactive.

Table 6.

SAR on the benzhydryl portion

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | R1, R2 | IC50(µM)a | Selectivityb | |

| BJeLR | BJeH-LT | |||

| 2a | R1 = R2 = Ph | 1.03 | 4.97 | 4.8 |

| 2u | R1 = R2 = 2-Pyridyl | IA | IA | NA |

| 2v | R1 = R2 = 4-Pyridyl | IA | IA | NA |

| 2w | R1 = R2 = 4-F-Ph | 0.183 | 0.757 | 4.1 |

| 2x | R1 = R2 = 4-OMe-Ph | 1.57 | 5.32 | 3.4 |

| 2y | R1 = R2 = 4-Cl-Ph | 0.071 | 0.272 | 3.9 |

| 2z | R1 = Ph, R2 = 4-Cl-Ph | 0.129 | 0.51 | 4.0 |

Values are means of experiments performed in triplicate.

BJeH-LT IC50/BJeLR IC50.

IA = Inactive, highest concentration tested was 20 µg/ml.

NA = Not applicable

Introducing p-fluoro substituents on both phenyl rings (2w) led to a 5-fold increase in activity with a slight decrease in selectivity. Introduction of p-methoxy substituents on both phenyl groups (2x) led to a decrease in activity and selectivity. The introduction of p-chloro substituents on both phenyl rings (2y) led to a 14-fold increase in activity at the cost of a slight decrease in selectivity. Taking clues from the structure of the drug cetirizine, we made an analog that contains an unsymmetrical benzhydryl unit where only one phenyl ring has a 4-chloro substituent (2z). Unfortunately, this modification led to a decrease in activity. The amide function of 2y was also reduced to the corresponding amine (2y’, see supporting information), which led to a decrease in activity (26.4 µM in BJeLR). Homologation of 4 to produce 2w’ was also accomplished (see supporting information) but led to a less potent compound (2.99 µM in BJeLR).

Overall, studying the effect of structural changes of the benzhydryl portion of the molecule on activity turned out to be productive, and led to the identification of 2y with the bis-4-chlorophenyl substituent as the most potent compound in the nitroisoxazole series. Compound 2y was also found to have an IC50 of 107 nM in the DRD cell line, which represents a 16-fold increase in activity compared to the hit compound 2a. It also shows an IC50 of 628 nM in the BJeH cell line. This represents a 6-fold selectivity for the DRD (HRASG12V) vs the BJeH (non expressing HRASG12V) cell line.

In conclusion, HTS of the MLPCN library followed by SAR investigation led to the identification of two HRAS synthetic lethal compounds 1a and 2y with nanomolar potencies against two HRASG12V expressing cell lines and 4 to 23-fold selectivities against two control cell lines not expressing HRASG12V. Because these two probes were identified through a phenotypic screen, their target is still unknown. Future studies will be initiated in order to understand their mode of action and to shed light on RAS-dependent cancers. Compounds 1a and 2y have been registered with NIH Molecular Libraries Program (ML 162 and ML 210, respectively) and are available upon request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the NIH-MLPCN program (1 U54 HG005032-1 awarded to S.L.S.) and (R01CA097061 and R03MH084117 awarded to B.R.S.). S.L.S. and B.R.S. are Investigators with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data (protocols for the synthesis of analogs and bioassays, 1H and 13C NMR and LCMS) associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at [INSERT].

References and notes

- 1.Harvey JJ. Nature. 1964;204:1104. doi: 10.1038/2041104b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirsten WH, Mayer LA. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1967;39(2):311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbacid M. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1987;56:779. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.004023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaw AT, Winslow MM, Magendantz M, Ouyang C, Dowdle J, Subramanian A, Lewis TA, Maglathin RL, Tolliday N, Jacks T. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108(21):8773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105941108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mizuarai S, Kotani H. Hum. Genet. 2010;128(6):567. doi: 10.1007/s00439-010-0900-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luo J, Emanuele MJ, Li D, Creighton CJ, Schlabach MR, Westbrook TF, Wong KK, Elledge SJ. Cell. 2009;137(5):835. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Puyol M, Martın A, Dubus P, Mulero F, Pizcueta P, Khan G, Guerra C, Santamarıa D, Barbacid M. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:63. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scholl C, Frohling S, Dunn IF, Schinzel AC, Barbie DA, Kim SY, Silver SJ, Tamayo P, Wadlow RC, Ramaswamy S, et al. Cell. 2009;137(5):821. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barbie DA, Tamayo P, Boehm JS, Kim SY, Moody SE, Dunn IF, Schinzel AC, Sandy P, Meylan E, Scholl C, et al. Nature. 2009;462:108. doi: 10.1038/nature08460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Babij C, Zhang Y, Kurzeja RJ, Munzli A, Shehabeldin A, Fernando M, Quon K, Kassner PD, Ruefli-Brasse AA, Watson VJ, Fajardo F, Jackson A, Zondlo J, Sun Y, Ellison AR, Plewa CA, San Miguel T, Robinson J, McCarter J, Schwandner R, Judd T, Carnahan J, Dussault I. Cancer Res. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo W, Wu S, Liu J, Fang B. Cancer Res. 2008;68(18):7403. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dolma S, Lessnick SL, Hanh WC, Stockwell BR. Cancer Cell. 2003;3(3):285. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang WS, Stockwell BR. Chem. Biol. 2008;15(3):234. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan DA, Giaccia AJ. Nat. Rev. Drug Disc. 2011;10:351. doi: 10.1038/nrd3374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hahn WC, Counter CM, Lundberg AS, Beijersbergen RL, Brooks MW, Weinberg RA. Nature. 1999;400:464. doi: 10.1038/22780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh J, Petter RC, Baillie TA, Whitty A. Nat. Rev., Drug Disc. 2011;10:307. doi: 10.1038/nrd3410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perez DI, Palomo V, Perez C, Gil C, Dans PD, Luque FJ, Conde S, Martinez A. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:4042. doi: 10.1021/jm1016279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lepore SD, Mondal D. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:5103. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2007.03.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.