Abstract

This study examined the nature of pathways between marital hostility and withdrawal, parental disagreements about child rearing issues, and subsequent changes in parental emotional unavailability and inconsistent discipline in a sample of 225 mothers, fathers, and 6-year-old children. Results of autoregressive, structural equation models indicated that marital withdrawal and hostility were associated with increases in parental emotional unavailability over the one-year period, whereas marital hostility and withdrawal did not predict changes in parental inconsistency in discipline. Additional findings supported the role of child rearing disagreements as an intervening or mediating mechanism in links between specific types of marital conflict and parenting practices. Implications for clinicians and therapists working with maritally distressed parents and families are discussed.

Keywords: marital conflict, parenting, structural equation modeling

The marital relationship is conceptualized as the cornerstone of the family unit in family systems theory (Owen & Cox, 1997). Thus, a derivative assumption is that difficulties in the marriage will proliferate to disrupt parenting practices. Consistent with these predictions, marital conflict has been associated with perturbations in parenting such as emotional unavailability (Fauber, Forehand, Thomas, & Wierson, 1990; Harold & Conger, 1997) and difficulties controlling or managing children (Stoneman, Brody, & Burke, 1989). However, inconsistencies in results also underscore the considerable heterogeneity in the magnitude of relationships between marital and parent– child dyads (Erel & Burman, 1995; Grych, 2002). To account for this variability, family process conceptualizations have suggested that pathways between marital conflict and perturbations in family subsystems may vary depending on the specific ways that marital conflict is expressed in the home. For example, different conflict expressions have been shown to have distinct implications for the stability and health of the family system (Christensen & Heavey, 1990; Gottman & Levenson, 1992). Despite the potential value of dissecting forms of marital conflict, research on the pathways between marital conflict and parenting has continued to tacitly operationalize marital discord as unidimensional in nature. Thus, a principal goal of this study was to examine the nature of the interplay between marital hostility and withdrawal in predicting change in two primary classes of parenting: emotional unavailability and inconsistent discipline. Testifying to the clinical relevance of this aim, understanding the relative impact of different types of marital conflict on parenting behaviors may assist in the formulation of specific treatment targets and tools in family treatment programs (Emery, 2001).

Prevailing family conceptualizations underscore the potential value of distinguishing between hostility and withdrawal in the marriage. Whereas marital hostility is commonly defined by displays of anger and hostility, marital withdrawal is typically characterized by expressions of detachment and avoidance during marital discussions. Despite differences in the substantive properties of these two conflict dimensions, disagreement exists about the nature of differences between marital hostility and withdrawal in predicting family disturbances. Some models have proposed that marital hostility and withdrawal may have unique, deleterious consequences for the family system (Katz & Gottman, 1996). Interpersonal antagonism underlying hostile marital interactions may disrupt parental abilities to serve as socialization agents (Easterbrooks & Emde, 1988). Conversely, spousal withdrawal has been hypothesized to result in greater disengagement from parenting, as parents rely on similar coping tactics across family subsystems (Crockenberg & Covey, 1991). Supporting this prediction, Katz and Gottman (1996) reported that marital hostility was associated with negativity and power-assertive parenting by fathers while husband marital withdrawal predicted maternal rejection.

In contrast, other models suggest that linkages between marital discord and disruptions in parenting processes may be largely attributable to underlying marital disengagement rather than marital hostility. Studies on the long-term stability of marriage have suggested that withdrawal may reflect a more destructive process than anger expression because withdrawal may prevent the resolution of serious marital problems and reflect psychological abandonment and detachment of spouses (Christensen & Heavey, 1990). For example, marital cascade models suggest that mutual spousal hostility may be benign for the family because it may signify some degree of emotional investment in the marital relationship. However, turmoil in the family system is theorized to be amplified if the mutual hostility remains unresolved and evolves into spousal apathy and withdrawal (Gottman, 1993). Extending this line of inquiry to the family unit, Cox, Paley, Payne, and Burchinal (1999) found that prenatal marital withdrawal, rather than marital hostility, predicted diminished parental responsiveness in parent– infant interactions at 3 and 12 months.

In light of evidence indicating that family antecedents of parenting may vary across parenting dimensions (Pettit, Laird, Dodge, Bates, & Criss, 2001), it is also possible that marital withdrawal and hostility may operate differently depending on the specific type of parenting practice examined. Two distinct dimensions of parenting practices have been consistently identified in the literature: parental emotional availability (e.g., warmth) and parental behavioral control (e.g., consistent discipline) (Maccoby & Martin, 1983). Previous studies have indicated that the magnitude of associations between hostile marital conflict and parenting difficulties may vary across different forms of parenting (Davies, Sturge-Apple, & Cummings, 2004; Fauber et al., 1990; Gonzalez, Pitts, Hill, & Roosa, 2000). In expanding on this work, a differential impact hypothesis suggests that marital withdrawal and hostility may be differentially related to affective parenting practices in comparison to parental behavioral control. To our knowledge, however, no studies have attempted to systematically investigate whether specific forms of conflict differentially predict different dimensions of parenting. To address this gap, the current study examined the relative roles of marital withdrawal and hostility in the prediction of paternal and maternal emotional unavailability and discipline inconsistency.

Delineating pathways between marital conflict and parenting practices requires further follow up analyses to explicate possible mechanisms underlying interdependencies among family subsystems. To address the question of why specific marital conflict tactics are associated with parenting difficulties, this study examined the role of disagreements about child rearing issues as a possible intermediary mechanism in pathways between marital conflict and parenting practices. A primary assumption of family systems theory is that disruptions and discord in marital relations ultimately undermine parenting practices by disrupting relational processes in other family subsystems (Grych, 2002; McHale, 1995). Marital problems are specifically hypothesized to engender difficulties in the coparenting partnership and, in the process, indirectly undermine child rearing practices (Belsky, Crnic, & Gable, 1995; Margolin, Gordis, & John, 2001; McHale, 1995). However, it is not clear if coparenting disagreements mediate pathways between marital withdrawal and parenting practices. Therefore, another primary goal of this study was to test process models in which child rearing conflict served as an intermediary process in linkages between marital hostility and withdrawal and maternal and paternal parenting practices.

In summary, our first goal was to address the paucity of research on the specificity of links between marital conflict and parenting practices by examining whether paths between marital conflict and subsequent change in parenting varied as a function of the type of marital conflict and parenting practice. Guided by previous work on associations between marital discord and parenting difficulties (e.g., Cowan & Cowan, 1992), we specifically tested the hypothesis that marital hostility and withdrawal would each predict greater parental emotional unavailability and inconsistent discipline. To advance a process model of marital discord and parenting practices, a second central goal of this study was to test the hypothesis that child rearing disagreements served as an intervening mechanism linking interparental hostility and withdrawal to changes in parenting. The generalizability and specificity of these process pathways were further examined by testing parent and child gender as potential moderators. In addressing the practical implications of this study, elucidating the pathways among forms of marital conflict and parenting practices may help clinicians develop more focused interventions that target specific marital processes underlying different types of parenting difficulties. Likewise, examining the role of the coparenting relationship as an intervening mechanism in associations between marital and parenting disturbances may provide practitioners with alternative strategies for strengthening the family system by limiting the impact of protracted marital discord on parenting practices (e.g., Cowan & Cowan, 2002; McHale et al., 2004).

Method

Participants

The data for this study were drawn from an Institutional Review Board–approved project designed to assess linkages between family relationships and children’s coping and adjustment (see Davies et al., 2004). The original pool of participants consisted of 235 mothers, fathers, and children. Families were included in the project if they met the eligibility criteria that the family had a child in kindergarten who had lived with two primary caregivers for at least 3 years. The retention rate from the first to second measurement occasion was 95%, resulting in a sample of 227 families (children = 126 girls and 101 boys) for the prospective analyses in this study. Two families identified as multivariate outliers across all models specified in this study were excluded from the analyses. Children were, on average, 6 years old (SD = .48) at the first measurement wave (Wave 1). Families were demographically representative of the counties from which they were drawn. Median family income of the participants fell between a range of $40,000 and $54,000, with 13% of the sample reporting household income below $23,000. A large proportion of the sample was European American (77.3%), followed by smaller percentages of African American (15.9%), Latin American (4.0%), Asian American (1.1%), Native American (0.2%), and other racial (1.5%) families (see Davies et al., 2004 for more details on demographic characteristics).

Procedures

Parents and children completed consent and assent forms that were approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board. Families visited the laboratories at the research sites two times at each of two measurement waves spaced one year apart. At each wave, two visits were conducted within an approximate period of one week. At the beginning of the first visit of the first wave, mothers and fathers participated in a marital interaction task in which they attempted to manage and resolve two common, intense marital disagreements that they viewed as problematic in their relationship. Following similar procedures in previous research (Du Rocher Schudlich, Papp, & Cummings, 2004), spouses independently selected topics that they perceived as problematic in their marriage and then conferred to select one topic from the father’s list and one topic from the mother’s list that they both felt comfortable discussing. Maternal and paternal parenting measures were obtained from separate 10-min play and clean up tasks at each wave. The task consists of 5 mins of free play between the parent and child followed by a 5-min period in which the parent attempts to have the child clean up the toys. Fathers participated in the task during the first visit; mothers participated in the task during the second visit. Videotaped records of the marital and parent– child interactions were obtained for coding marital and parenting difficulties.

Measures

Marital conflict

Marital interaction behaviors of mothers and fathers during the marital discussion tasks during the Wave 1 visit were evaluated using subscales from Malik and Lindahl’s (2004) System for Coding Interactions in Dyads (SCID). The SCID yielded molar ratings of affective and communicative behaviors of husbands and wives for each of the two marital interactions on 5-point continuous scales ranging from 1 (very low) to 5 (high). The rating scale has been widely used across different populations and has demonstrated validity in its relation to similar measures of marital interaction and reliability across studies (Malik & Lindahl, 2004).

Maternal and paternal hostility during each of the marital interactions was assessed using the following SCID scales: (a) verbal aggression, which is defined as the level of hostile and aggressive behaviors and verbalizations each partner expresses toward the other; (b) negativity and conflict, which reflects spousal displays of anger, frustration and tension; and (c) support, which, at low levels, reflects overt disregard for the needs and well-being of the partner. Intraclass correlation coefficients, which indexed the reliability of two independent coders for 25% of the interactions, ranged from .85 to .98 for mothers and fathers across each of the interactions. Given the moderate-to-high correlations between the three scales for mothers (rs between .43 and .80) and fathers (rs between .40 and .78), the three indices of hostility were aggregated to yield more parsimonious composites of maternal and paternal hostility. Coders also rated each couple as a whole using the negative escalation code from the SCID, which assesses tendencies of the partners to reciprocate and escalate displays of negative affect and hostility. The intraclass correlation coefficients, which reflect the interrater reliability of two independent coders for 25% of the interactions, were .96 and .97 across the two interactions. Given the high correlation between negative escalation ratings across the two tasks (r = .66), ratings were summed to form a single measure of couple negative escalation. The resulting measures of maternal hostility, paternal hostility, and couple negative escalation were used as manifest indicators of a latent construct of marital hostility in the structural equation models.

Consistent with the marital hostility measurement battery, mother, father, and couple withdrawal during the marital interactions was assessed using SCID scales (Malik & Lindahl, 2004). Maternal and paternal withdrawal were specifically assessed through the SCID withdrawal scale, with higher scores reflecting displays of repeated, prolonged, and tense forms of detachment and avoidance during the marital interactions. Intraclass correlation coefficients, which index interrater reliability, ranged from .85 to .96 for mothers and fathers across each of the two interactions. To obtain a third index of withdrawal, coders rated the couple as a whole using the pursuit/withdraw scale from the SCID, which assesses the extent to which one partner attempts to avoid discussion while the other partner attempts to continue the discussion. The intraclass correlation coefficients for the couple were .90 and .91 across the two interactions. Ratings of withdrawal across the two interactions were aggregated to form single measures of maternal withdrawal, paternal withdrawal, and pursuit-withdrawal in light of significant intercorrelations for each code over the two interactions (r = .49 to .52). Measures of maternal and paternal withdrawal and couple pursuit-withdrawal were subsequently used as manifest indicators of a latent construct of marital withdrawal in the structural equation models.

Parenting practices

Parenting behaviors of mothers and fathers during the play and cleanup tasks at Wave 1 and Wave 2 were evaluated using subscales from the Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales (IFIRS; Melby & Conger, 2001). The global rating scales of the IFIRS assess the frequency, quality, and intensity of a parent’s caregiving behaviors on 9-point scales, ranging from 1 (not at all characteristic) to 9 (mainly characteristic). The widely used IFIRS has demonstrated validity and reliability across studies (see Melby & Conger, 2001). Coders, who were blind to ratings of marital interaction, independently rated mother and father parenting behaviors. To reduce shared informant variance, different primary coders were used to assess maternal and paternal parenting.

Paternal and maternal emotional unavailability was assessed by the warmth/support and neglecting/distancing scales of the IFIRS during the parent– child interaction task. The neglecting/distancing scale measures parental indifference, apathy, and unresponsiveness during the parent– child interactions, whereas low levels of warmth/support are characterized by the failure to display affection, support, or praise toward the child. Separate ratings of the two emotional unavailability codes were obtained during play and compliance components of the interaction task. Intraclass correlation coefficients, which reflected interrater reliability among two coders for 21% of the interactions, ranged from .91 and .94 at Wave 1 and .82 to .92 at Wave 2 for ratings of the parenting codes for mothers and fathers. The four measures were treated as manifest indicators of latent composites of mother and father emotional unavailability.

To assess maternal and paternal discipline inconsistency, coders rated the cleanup portion of the interaction task using the inconsistent discipline, consistent discipline, and indulgent/permissive scales from the IFIRS (Melby & Conger, 2001). The consistent discipline code assesses the consistency with which parents maintain and enforce rules of conduct for the child whereas the inconsistent discipline code measures the extent to which parents are erratic in enforcing rules of conduct for the child. Finally, the indulgent/permissive scale reflects parental tendencies to be excessively lenient or lax in setting standards of child behavior. The consistent discipline code was reverse scored prior to analyses. Intraclass correlation coefficients, which indexed interrater reliability for 21% of the interactions, ranged from .87 to .95 at Wave 1 and .90 to .98 at Wave 2 across the three codes for mothers and fathers. Consistent with the measurement of emotional unavailability, the three discipline codes were used as manifest indicators of a latent composite indexing maternal and paternal inconsistent discipline.

Child rearing disagreements

Mothers and fathers completed an abbreviated version of the Child Rearing Disagreements (CRD) scale (Jouriles et al., 1991) during the Wave 1 assessment. The abbreviated CRD scale contains 8 items assessing the frequency of marital disagreements over child rearing issues (e.g., “being too tough in disciplining our child”). Items are rated using a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (daily). The original CRD has adequate internal consistency and the validity of the measure is supported by its associations with marital discord and child behavior problems. Internal consistency coefficients for the CRD scale in this sample were satisfactory (α’s = .79 and .75 for mothers and fathers respectively). Mother and father reports on the CRD were treated as manifest indicators of a larger latent composite of child rearing disagreements.

Overview of analysis plan

Structural equation modeling (SEM) using maximum likelihood performed with Amos 4.0 software (Arbuckle & Wothke, 1999) was used to examine all hypothesized models because of its ability to simultaneously test complex, multidimensional relationships. Model fit was assessed using (a) the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), with values of .08 or less reflecting reasonable fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1993); (b) the comparative fit index, with values of .90 and higher indicating a good fit (Bentler, 1990); and (c) the χ2/df ratio, with values between 1 and 3 indicating acceptable fit (Arbuckle & Wothke, 1999). Measurement models, which included all possible correlations among the latent variables, were examined prior to the structural model analyses. All measurement models fit the data well and the factor loadings for each manifest indicator of the latent constructs were all positive and significant at p < .001 (standardized loadings ranged from .48 to .97). For the sake of brevity, measurement model analyses are not presented but are available from Melissa Sturge-Apple. Residual error variances of corresponding manifest indicators across the two measurement waves for mothers and fathers were allowed to correlate for parenting constructs in each model. However, for clarity of presentation, correlations among residuals are not shown in the figures. Finally, our analysis of statistical power according to guidelines by MacCallum, Browne, and Sugawara (1996) indicated that each of the structural models had adequate power to reject the hypothesis of poor model fit.

To examine direct and mediating effects, we followed procedures outlined by Baron and Kenny (1986). We first analyzed a model that included only direct, predictive paths between marital hostility and withdrawal and the two outcome variables, Wave 2 maternal parenting and Wave 2 paternal parenting. Next, to test whether child rearing disagreements served as a mediating variable in the relationship between marital constructs and parenting practices, we examined a model that included the paths from marital hostility and withdrawal to child rearing disagreements and Wave 2 maternal and paternal parenting practices. We then examined the effect of regressing Wave 2 parenting practices on child rearing disagreements on the direct paths between marital conflict variables and Wave 2 parenting practices (i.e., testing whether a direct relation between marital constructs and parenting is reduced or eliminated). To determine the significance of the mediating effect, we utilized procedures for testing αβ as outlined by MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, and Sheets (2002).

Results

Associations among study measures are shown in Table 1. Relationships among study variables were in the expected direction and correlations between manifest indicators within a latent construct were generally higher than correlations with manifest indicators across study constructs. Additionally, mean levels of mother and father reports on the various conflict indices were comparable to, or higher than, means obtained in other community samples (e.g., Davies & Windle, 1997). Finally, an analysis of the item frequencies on the child rearing disagreements scales indicated that almost 25% of parents reported experiencing “almost daily” disagreements for at least one of the eight topics on the scale.

Table 1.

Associations Among Study Measures

| Measures | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | HOSW1M | — | |||||||||||||||||

| 2. | HOSW1F | .69 | — | ||||||||||||||||

| 3. | HOSW1C | .78 | .72 | — | |||||||||||||||

| 4. | WITHW1M | −.01 | .11 | −.10 | — | ||||||||||||||

| 5. | WITHW1F | .08 | .16 | −.12 | .38 | — | |||||||||||||

| 6. | WITHW1C | .14 | .11 | −.08 | .38 | .62 | — | ||||||||||||

| 7. | CRDW1-M | .12 | .18 | .12 | .14 | .07 | .12 | — | |||||||||||

| 8. | CRDW1-F | .13 | .12 | .10 | .20 | .06 | .12 | .39 | — | ||||||||||

| 9. | PNDW1-M | .15 | .11 | .05 | .25 | .22 | .08 | .14 | .19 | — | |||||||||

| 10. | PWSW1-M | .13 | .10 | .02 | .23 | .16 | .11 | .17 | .15 | .56 | — | ||||||||

| 11. | C-NDW1-M | .13 | .14 | .10 | .17 | .10 | .04 | .09 | .26 | .59 | .36 | — | |||||||

| 12. | C-WSW1-M | .11 | .17 | .01 | .17 | .19 | .08 | .17 | .14 | .43 | .51 | .39 | — | ||||||

| 13. | P-NDW1-F | .11 | .06 | .04 | .22 | .15 | .14 | .09 | .05 | .04 | .16 | .11 | .18 | — | |||||

| 14. | P-WSW1-F | .11 | .07 | .01 | .15 | .14 | .12 | .14 | .09 | .06 | .17 | .10 | .22 | .69 | — | ||||

| 15. | C-NDW1-F | .01 | .05 | −.02 | .18 | .11 | .01 | .03 | .06 | −.01 | .08 | .13 | .17 | .72 | .56 | — | |||

| 16. | C-WSW1-F | .03 | .04 | −.03 | .13 | .13 | .15 | .04 | .11 | .07 | .16 | .09 | .22 | .52 | .72 | .62 | — | ||

| 17. | C-IPW1-M | −.04 | −.06 | −.09 | .03 | −.01 | .04 | .22 | .09 | .05 | .03 | −.14 | .24 | −.05 | .02 | −.16 | −.07 | — | |

| 18. | C-CDW1-M | −.02 | −.04 | −.07 | .03 | −.02 | .02 | .23 | .09 | .07 | .02 | −.13 | .23 | −.06 | −.01 | −.18 | −.07 | .97 | — |

| 19. | C-IDW1-M | −.04 | −.06 | −.09 | .04 | −.01 | .03 | .21 | .10 | .06 | .03 | −.11 | .24 | −.05 | −.01 | −.15 | −.09 | .95 | .97 |

| 20. | C-IPW1-F | −.06 | −.08 | −.05 | −.02 | .08 | .07 | −.03 | −.06 | .03 | −.01 | .01 | −.06 | −.11 | −.14 | −.13 | −.04 | −.03 | −.04 |

| 21. | C-CDW1-F | −.02 | −.03 | −.04 | −.02 | .07 | .06 | −.05 | −.02 | .05 | −.01 | .05 | −.05 | −.01 | −.03 | −.04 | .05 | −.04 | −.04 |

| 22. | C-IDW1-F | −.04 | −.07 | −.06 | −.04 | .05 | .02 | −.06 | −.03 | .07 | .01 | .06 | −.01 | −.02 | −.03 | −.01 | .08 | −.01 | −.04 |

| 23. | P-NDW2-M | .17 | .26 | .18 | .30 | .15 | .05 | .27 | .24 | .38 | .37 | .34 | .25 | .14 | .13 | .08 | .10 | −.01 | .02 |

| 24. | P-WSW2-M | .18 | .23 | .15 | .23 | .15 | .04 | .22 | .15 | .29 | .34 | .23 | .26 | .12 | .16 | .08 | .07 | −.05 | −.05 |

| 25. | C-NDW2-M | .15 | .29 | .16 | .31 | .23 | .12 | .21 | .27 | .34 | .30 | .43 | .29 | .16 | .18 | .16 | .23 | −.16 | −.15 |

| 26. | C-WSW2-M | .22 | .26 | .17 | .27 | .22 | .09 | .21 | .20 | .33 | .38 | .37 | .34 | .20 | .27 | .15 | .22 | −.05 | −.06 |

| 27. | P-NDW2-F | .04 | .02 | .01 | .10 | .21 | .14 | .06 | .03 | .06 | .14 | .09 | .07 | .31 | .43 | .28 | .38 | −.10 | −.13 |

| 28. | P-WSW2-F | .06 | .06 | .01 | .09 | .18 | .05 | .05 | −.03 | .01 | .14 | −.09 | .04 | .26 | .45 | .26 | .42 | −.08 | −.08 |

| 29. | C-NDW2-F | .08 | .08 | .05 | .12 | .22 | .11 | .10 | −.02 | −.03 | .14 | .04 | .10 | .34 | .34 | .37 | .33 | −.08 | −.10 |

| 30. | C-WSW2-F | .06 | .11 | .01 | .10 | .19 | .06 | .10 | .04 | .01 | .18 | −.06 | .08 | .28 | .44 | .34 | .46 | −.07 | −.09 |

| 31. | C-IPW2-M | .07 | .02 | .10 | −.04 | .06 | −.01 | .07 | .04 | .03 | .05 | .01 | .02 | −.07 | −.03 | −.13 | −.08 | .21 | .19 |

| 32. | C-CDW2-M | .11 | .05 | .14 | −.09 | .04 | −.01 | .05 | .04 | −.01 | .05 | .02 | .01 | −.07 | −.03 | −.11 | −.07 | .17 | .14 |

| 33. | C-IDW2-M | .08 | .04 | .13 | −.08 | .02 | −.05 | .05 | .02 | .01 | .05 | .01 | .01 | −.07 | −.03 | −.12 | −.08 | .17 | .15 |

| 34. | C-IPW2-F | .04 | .03 | .02 | .07 | −.03 | .01 | .14 | .14 | .10 | .08 | .20 | .10 | .08 | .09 | −.06 | .06 | .12 | .15 |

| 35. | C-CDW2-F | .04 | .04 | .01 | .06 | −.01 | −.06 | .15 | .15 | .11 | .13 | .21 | .15 | .08 | .12 | −.03 | .09 | .10 | .11 |

| 36. | C-IDW2-F | .04 | .05 | .02 | .08 | .02 | −.04 | .14 | .15 | .13 | .15 | .21 | .15 | .11 | .13 | −.01 | .11 | .10 | .11 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | M | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.43 | 1.67 | 6.00 | 30.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 4.19 | 1.60 | 6.00 | 30.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3.42 | 1.79 | 2.00 | 10.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3.46 | 1.60 | 2.00 | 9.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3.89 | 1.90 | 2.00 | 10.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3.89 | 1.82 | 2.00 | 10.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 14.58 | 4.67 | 8.00 | 34.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 14.95 | 4.53 | 8.00 | 39.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1.52 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 6.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 5.65 | 1.24 | 2.00 | 9.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1.40 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 8.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 5.71 | 1.40 | 2.00 | 9.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2.17 | 1.76 | 1.00 | 8.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 5.60 | 1.62 | 2.00 | 9.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2.01 | 1.78 | 1.00 | 9.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 5.59 | 1.71 | 2.00 | 9.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3.59 | 2.35 | 1.00 | 9.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3.67 | 2.28 | 1.00 | 9.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| — | 3.23 | 2.36 | 1.00 | 9.00 | |||||||||||||||||

| −.04 | — | 4.01 | 2.74 | 1.00 | 9.00 | ||||||||||||||||

| −.03 | .88 | — | 4.15 | 2.53 | 1.00 | 9.00 | |||||||||||||||

| −.03 | .84 | .94 | — | 3.89 | 2.66 | 1.00 | 9.00 | ||||||||||||||

| .01 | −.07 | −.02 | −.03 | — | 1.77 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 6.00 | |||||||||||||

| −.04 | −.16 | −.11 | −.11 | .63 | — | 4.29 | 1.26 | 1.00 | 8.00 | ||||||||||||

| −.16 | −.11 | −.05 | −.04 | .69 | .58 | — | 1.83 | 1.24 | 1.00 | 8.00 | |||||||||||

| −.05 | −.15 | −.07 | −.07 | .60 | .74 | .71 | — | 4.32 | 1.53 | 1.00 | 9.00 | ||||||||||

| −.12 | .02 | .03 | .05 | .11 | .19 | .25 | .24 | — | 2.31 | 1.65 | 1.00 | 9.00 | |||||||||

| −.11 | .04 | −.04 | −.02 | .06 | .20 | .16 | .21 | .66 | — | 5.74 | 1.73 | 1.00 | 9.00 | ||||||||

| −.07 | −.02 | −.02 | .01 | .08 | .18 | .15 | .19 | .76 | .54 | — | 2.14 | 1.62 | 1.00 | 9.00 | |||||||

| −.11 | −.10 | −.08 | −.05 | .10 | .26 | .23 | .27 | .59 | .80 | .63 | — | 5.77 | 1.73 | 1.00 | 9.00 | ||||||

| .17 | −.07 | −.09 | −.12 | .02 | −.05 | −.05 | .12 | −.03 | −.05 | −.06 | −.06 | — | 3.22 | 2.29 | 1.00 | 9.00 | |||||

| .14 | −.04 | −.08 | −.10 | .03 | −.05 | −.03 | .12 | −.03 | −.08 | −.05 | −.05 | .95 | — | 2.86 | 2.11 | 1.00 | 9.00 | ||||

| .14 | −.05 | −.07 | −.09 | .03 | −.04 | −.03 | .13 | −.03 | −.06 | −.05 | −.05 | .94 | .97 | — | 2.87 | 2.29 | 1.00 | 9.00 | |||

| .15 | .21 | .22 | .20 | .09 | .01 | .07 | .08 | .03 | −.06 | .02 | −.01 | .09 | .09 | .08 | — | 3.50 | 2.34 | 1.00 | 9.00 | ||

| .12 | .19 | .21 | .18 | .14 | .08 | .13 | .15 | .11 | −.01 | .12 | .08 | .08 | .08 | .06 | .91 | — | 3.43 | 2.30 | 1.00 | 9.00 | |

| .13 | .19 | .22 | .19 | .16 | .08 | .14 | .15 | .13 | .01 | .14 | .09 | .09 | .10 | .08 | .89 | .96 | — | 3.22 | 2.43 | 1.00 | 9.00 |

Note. M = mother, F = father, C = couple, HOS = hostile conflict, WITH = withdrawal, CRD = child rearing disagreements, C = compliance, P = play, ND = neglecting/distancing, WS = warmth/support, IP = indulgent/permissive, CD = consistent discipline, ID = inconsistent discipline, W1 = Wave 1, W2 = Wave 2. Correlations ≥ |.13| are significant at the p < .05 level.

Moderating Effect of Child Gender

Given the potential moderating role of child gender in models of family process (Davies & Lindsay, 2001), we initially examined whether the proposed links between marital discord and parenting differed as a function of child gender by splitting the data by boys and girls and estimating models simultaneously using a multiple-group analysis (for details, see Sturge-Apple, Davies, Boker, & Cummings, 2004). For the emotional unavailability and inconsistent discipline models, we estimated the multiple-group model with all direct paths between marital variables and parenting outcomes constrained to equality for boys and girls. Next, we estimated a model in which these parameters were allowed to vary freely. Comparisons of the constrained and free-to-vary models revealed no difference in fit, thus indicating that child gender did not moderate links between marital discord and parenting practices. Therefore, all subsequent analyses were performed with the full sample.

Marital Withdrawal and Hostility and Parental Emotional Unavailability

We first examined direct associations between dimensions of marital conflict and maternal and paternal emotional unavailability. The overall fit of the model to the data was acceptable, χ2(184, N = 225) = 402.30, p = .001, RMSEA = .07, CFI = .92, χ2/df ratio = 2.19. Examination of the path coefficients, which are denoted in brackets in Figure 1, revealed that marital hostility was a significant, albeit modest, predictor of greater maternal emotional unavailability (β = .20, p < .05) but negligibly related to paternal emotional unavailability (β = .03, p = .57). In contrast, marital withdrawal was a significant predictor of both maternal and paternal emotional unavailability, β = .17 and β = .17, ps < .05, respectively. Furthermore, the critical ratio for differences statistic was calculated to determine whether the magnitude of associations between forms of marital conflict and maternal and paternal parenting were significantly different from each other. The results indicated that, in comparison with marital hostility, marital withdrawal was more strongly associated with paternal emotional unavailability, z = 2.25, p < .05. However, for mothers, these two paths for marital hostility and withdrawal were not statistically different from one another, z = 1.25, p > .05.

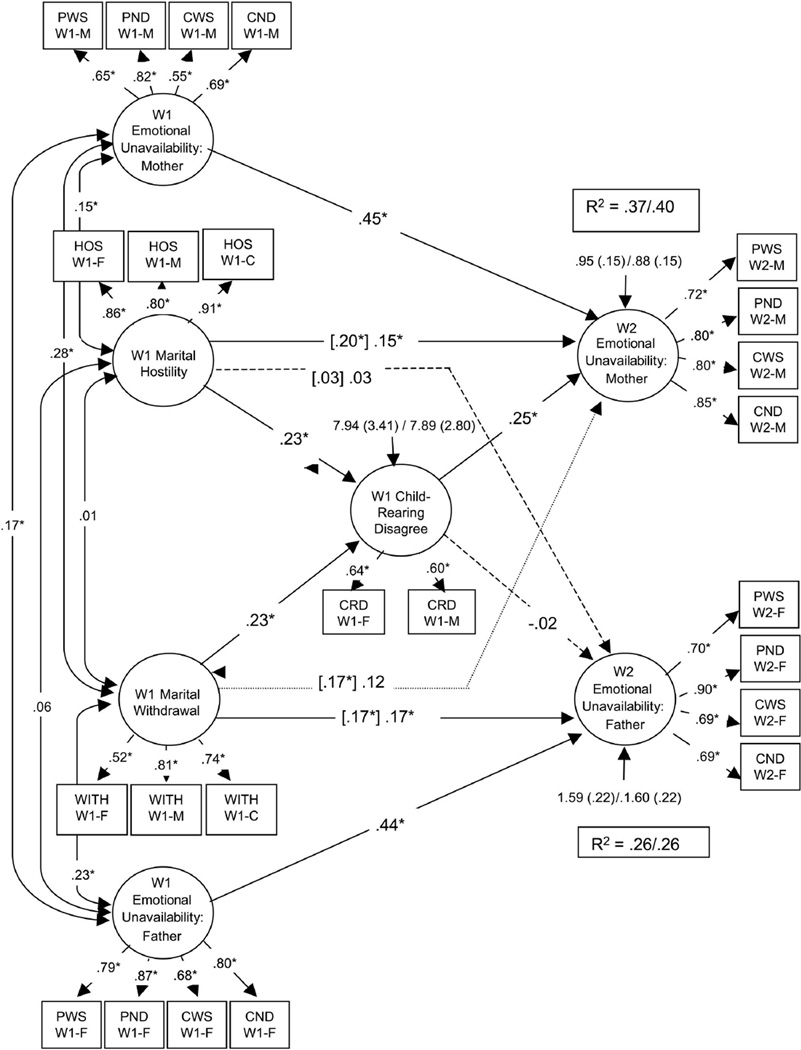

Figure 1.

Model of marital hostility and withdrawal predicting change in maternal and paternal emotional unavailability with child rearing disagreements as a potential mediator. For ease of presentation, correlations among cross-lag residuals for similar manifest indicators and among exogenous latent variables are not shown in the figure. Numbers in brackets [ ] represent estimates from model analysis when the mediator is absent. Large dashed paths (— — —) signify nonsignificant paths; small dashed paths (- - -) signify a direct path mediated by child rearing disagreements. M = mother, F = father, C = couple, HOS = hostile conflict, WITH = withdrawal, CRD = child rearing disagreements, PWS = play warmth/support, PND = play neglecting/distancing, CWS = compliance warmth/support, CND = compliance neglecting/distancing, W1 = Wave 1, W2 = Wave 2. * p < .05.

Figure 1 also shows the results of the structural equation model after specifying the intermediary role of parental disagreements about child rearing in paths between marital conflict and parent emotional unavailability. The structural paths for this model are denoted by the nonbracketed coefficients in Figure 1. The model provided an acceptable representation of the data, χ2(224, N = 225) = 478.02, p = .001, RMSEA = .07, CFI = .91, χ2/df ratio = 2.13. Examination of the path coefficients indicated that both marital hostility and withdrawal predicted higher levels of child rearing disagreements (β’s = .23 and .23, respectively, p < .05). In turn, child rearing disagreements predicted greater emotional unavailability for mothers only (β = .25, p < .05). Further analysis of these indirect pathways revealed that the direct effect of marital withdrawal on maternal emotional unavailability was reduced by 24% when the child rearing disagreements were estimated in the model, β = .17, p < .05 to β = .12, ns. Follow-up tests using MacKinnon and colleagues (2002) procedures indicated that the indirect pathway (αβ) was significant in the prediction of maternal emotional unavailability (z′ = 1.71, p < .05). Thus, spousal conflict about child rearing was a modest mediator in the link between marital withdrawal and mothers’ emotional unavailability. In contrast, the effects of marital hostility on maternal emotional unavailability were not significantly reduced with the inclusion of child rearing disagreements, however the indirect pathway was significant (z′ = 1.72, p < .05), suggesting that child rearing disagreements were a partial mediator of the effects of marital hostility on the emotional unavailability of mothers. For fathers, child rearing disagreements were not associated with changes in paternal emotional unavailability, therefore no indirect pathways were identified between the two forms of marital conflict and paternal emotional unavailability.

Marital Hostility and Withdrawal and Parental Inconsistent Discipline

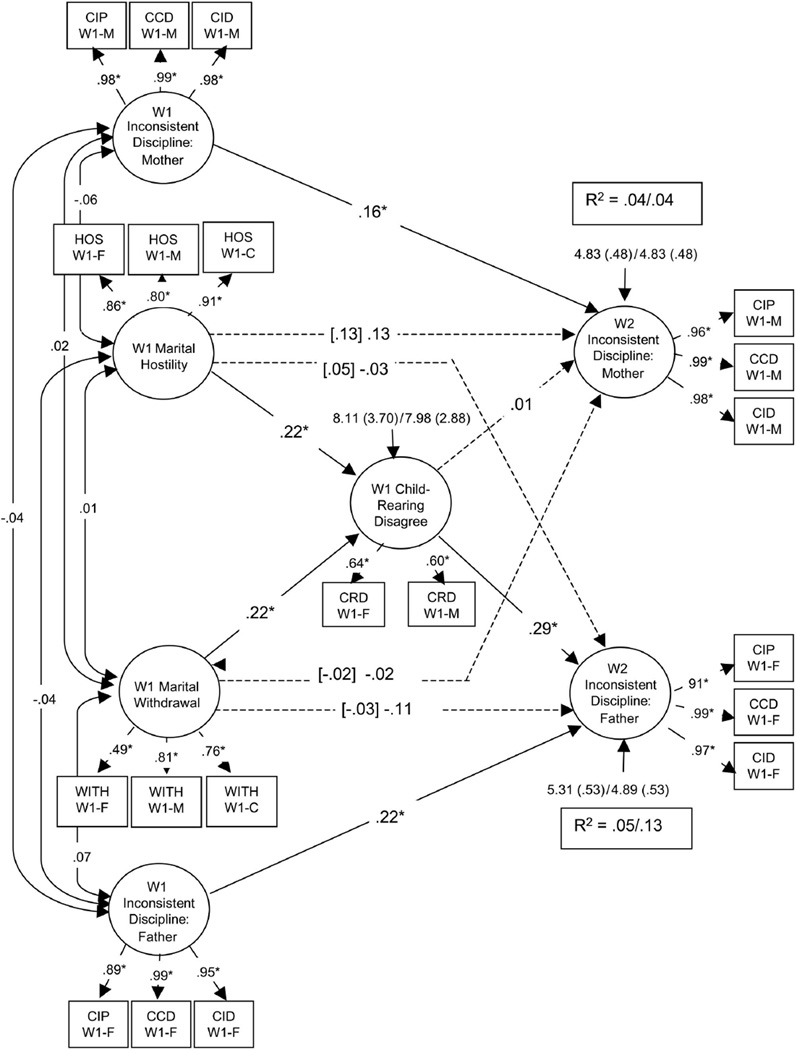

Following the same format as the models of parent emotional unavailability, we first utilized SEM to simultaneously examine the roles of marital hostility and withdrawal as predictors of maternal and paternal inconsistent discipline (see Figure 2). The structural paths in the model, denoted by the bracketed coefficients, also are shown in Figure 2. The model provided a good fit to the data, χ2(117, N = 225) = 166.34, p= .01, RMSEA = .04, CFI = .99, χ2/df ratio = 1.42. In contrast to the parental emotional availability model, marital hostility and withdrawal failed to predict changes in maternal and paternal inconsistent discipline over the one-year time period, with βs ranging from −.02 to .13, ps > .05.

Figure 2.

Structural equation model of maximum likelihood estimation of marital hostility and withdrawal as predictors of maternal and paternal inconsistent discipline with intervening variable child rearing disagreements. For ease of presentation, correlations among cross-lag residuals for similar manifest indicators and among exogenous latent variables are not shown in the figure. Numbers in brackets [ ] represent estimates from model analysis when the mediator is absent. Dashed paths (- - -) signify nonsignificant paths. M = mother, F = father, C = couple, HOS = hostile conflict, WITH = withdrawal, CRD = child rearing disagreements, CIP = compliance indulgent/permissive, CCD = compliance consistent discipline, CID = compliance inconsistent discipline, W1 = Wave 1, W2 = Wave 2. * p < .05

Although these results rule out the possibility that child rearing disagreements may act as a mediator, it may still serve as an intervening mechanism that indirectly links forms of marital conflict with parental inconsistent discipline (e.g., Davies, Harold, Goeke-Morey, & Cummings, 2002; Grych, Harold, & Miles, 2003). Broadly defined, intervening variables provide a link between independent and outcome variables such that a predictor is related to an outcome variable through their relationship with an intervening variable (e.g., X > I > Y; MacKinnon et al., 2002). Therefore, an intervening variable does not necessarily require a significant direct path between a predictor and outcome. Rather, intervening variables may provide the link between a predictor and outcome. Examining indirect pathways are valuable in elucidating important processes that are set in motion by the occurrence of distal, but etiologically central, factors in family process models (Grych et al., 2003).

To test intervening processes for inconsistent discipline, we examined a model that included child rearing disagreements in the relationship between marital hostility and withdrawal and parental inconsistency in discipline. The nonbracketed coefficients in Figure 2 denote the structural paths calculated for this model. To determine the significance of the intervening effect of child rearing disagreements, we utilized procedures outlined by MacKinnon and colleagues (2002). The overall model, which is depicted in Figure 2, evidenced an acceptable fit to the data, χ2(148, N = 225) = 196.38, p= .001, RMSEA = .04, CFI = .99, χ2/df ratio = 1.33. Examination of the paths revealed two indirect pathways between forms of marital conflict and inconsistent discipline. Marital withdrawal was specifically associated with greater child rearing disagreements, which in turn was related to high levels of paternal inconsistent discipline. Follow-up tests examining the statistical significance of the indirect path between marital withdrawal and child rearing disagreements (α = .22, p < .05) and the path between child rearing disagreements and paternal inconsistency in discipline (β = .29, p < .05) indicated that the indirect pathway (αβ) was significant (z′ = 1.68, p < .05). Likewise, the indirect effect between the effects of marital hostility on elevated spousal disagreements about child rearing disagreements (α = .22, p < .05) and paternal inconsistent discipline (β = .29, p < .05) was significant (z′ = 1.76, p < .05). In contrast to the prediction of paternal inconsistent discipline, no indirect pathways were found for maternal inconsistency in discipline.

Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to elucidate the nature of pathways between forms of marital conflict and specific types of maternal and paternal parenting practices. Questions in the literature remain about the nature of the interplay between specific forms of conflict in predicting parenting practices. Previous studies have tended to focus on a single dimension of conflict (e.g., Fauber et al., 1990) or have examined multiple dimensions of conflict in isolation (e.g., Katz & Gottman, 1996). To overcome this limitation, the first aim of this study was to simultaneously delineate associations between marital hostility and withdrawal during conflict and subsequent changes in maternal and paternal caregiving practices over a one-year period. The findings presented here have important implications both for future empirical work and for practitioners working with maritally distressed parents. Understanding the harmful effect of different types of marital conflict on family relationships may help guide clinicians in their work to educate couples on the importance and implications of eliminating detrimental marital interaction patterns for the health and stability of the family system.

In models predicting parental emotional unavailability, our findings suggest that different pathways may be operating in the prediction of maternal and paternal parenting. Our results demonstrated that marital withdrawal was a significantly stronger predictor of paternal emotional unavailability than the negligible paths between marital hostility and paternal unavailability. Interpreted within a cascade model, these results suggest that the harmful effects of marital withdrawal may proliferate beyond the marital subsystem by engendering broader patterns of paternal disengagement that are reflected in diminished emotional availability in father– child interactions. In contrast, our results for mothers’ displays of emotional unavailability supported the differential impact hypothesis. More specifically, marital withdrawal and hostility were statistically comparable predictors of maternal emotional unavailability, and our findings raise the possibility that marital hostility and withdrawal set in motion relatively distinct processes in mothers that each uniquely impact maternal support and availability.

Guided by the affective organization model of parenting (Dix, 1991), it is possible that cumulative experiences with anger arousal in hostile marriages may undermine maternal availability in the caregiver role by priming negative appraisals and attributions of child behavior or disrupting their ability to identify the needs of their children. Although a thorough analysis of why different processes may be operating in the prediction of maternal and paternal parenting will require replication of our findings, one plausible explanation is that mothers may be vulnerable to a broader array of destructive marital conflict tactics than fathers by virtue of their greater sensitivity to interpersonal problems in the marital relationship (Cummings & Davies, 1994). Our findings here call particular attention to the value of alerting parents to the possibility that spousal detachment as well as overt hostility may affect their roles as responsive parents in therapeutic agenda. Incorporating the findings from the present study into practice, practitioners may help parents to understand that engagement in marital problem-solving, rather than avoidance of anger and hostility, may play a key role in enhancing parenting practices.

In contrast to models of parental emotional unavailability, there were no direct links between the forms of marital conflict and parental inconsistent discipline. Empirical inconsistencies in the small corpus of studies addressing associations between specific marital conflict dimensions and parents’ inconsistent discipline strategies obscure any authoritative analysis of our results. Nevertheless, inconsistencies may reflect differences in methodological rigor across studies. For example, studies utilizing questionnaire data from single informants have reported direct linkages between marital discord and inconsistent discipline exist (Gonzales, Pitts, Hill, & Roosa, 2000; Stoneman et al., 1989), whereas other studies utilizing multiple methods or informants have failed to find associations between marital conflict and discipline strategies (e.g., Davies et al., 2004; Fauber et al., 1990). Although drawing definitive conclusions about the nature and magnitude of paths between marital conflict and parental inconsistent discipline will require further research, differences in the consistency of direct associations between marital conflict and the two types of parenting practices are in accordance with some family process models. For example, some conceptualizations have postulated that preoccupation and distress arising from spousal conflict is particularly likely to disrupt parenting practices that require emotional and psychological sensitivity and responsiveness (e.g., Grych, 2002). Accordingly, it is possible that the effects of marital hostility and withdrawal on consistency in discipline practices may result from indirect processes through different family process variables.

The second goal of this study was to identify processes that underlie links between forms of marital conflict and specific parenting practices. Drawing from family systems theory, we tested the hypothesis that marital strife may ultimately undermine parenting practices by impairing the ability of parents to support each other in child rearing responsibilities (e.g., Minuchin, 1974). To delineate the proliferation of marital problems across family subsystems, we specifically examined whether disruptions in one aspect of the coparenting partnership, as reflected in spousal disagreements about children, is an intervening mechanism in links between forms of marital conflict and parenting practices. In partial support of our hypothesis, spousal disagreements about child rearing issues served as a mediating or intervening mechanism in four of the eight indirect pathways between forms of marital conflict and maternal and paternal parenting practices. In particular, the role of child rearing disagreements as an intervening mechanism of marital hostility and withdrawal was particularly robust in the prediction of subsequent maternal emotional unavailability and paternal discipline consistency. The findings here highlight an important avenue for clinical intervention with maritally distressed parents, in that interventions aimed at strengthening relationships between parents may hinge upon incorporating parental agreements about child rearing into therapeutic sessions.

These possible parent gender differences in the indirect pathways between marital conflict and parenting perturbations merit discussion. On the one hand, associations between marital conflict, child rearing disagreements, and parental emotional unavailability were specifically more consistent for mothers than fathers. In accordance with research indicating that women still assume considerably greater child rearing responsibilities than men (e.g., Thompson & Walker, 1989), it may be that marital difficulties and coparenting disturbances are especially likely to deplete the large psychological resources that mothers require to fulfill their considerable parenting responsibilities. On the other hand, our findings suggest that marital conflict variables may be indirectly linked to greater difficulties in paternal consistency in discipline. Given that fathers’ roles may be less socially scripted than mothers’ (Belsky, Youngblade, Rovine, & Volling, 1991), perhaps the effects of marital conflict on greater child rearing disagreements make it more difficult for fathers to utilize and solicit mothers’ input on discipline practices and result in greater use of inconsistent discipline techniques by fathers experiencing marital distress. Given the role of parent gender in the differential impact of types of marital conflict on coparenting and parenting for mothers and fathers, different therapeutic approaches aimed at strengthening parenting practices may be necessary for men and women in discordant marriages. However, although the differential role of child rearing disagreements for mothers and fathers is intriguing, replication of these exploratory findings will be required before definitive conclusions regarding the nature of these pathways can be made.

Several limitations should be taken into consideration in interpreting our results. First, care should be taken in generalizing the findings from our community sample to other samples. Second, although our study is among the first utilizing prospective assessments of associations between types of marital conflict and parenting practices, our data, which only assessed marital conflict at Wave 1, precluded a full examination of bidirectionality in paths between marital and parent– child subsystems (Cox & Paley, 1997). Third, although our multimethod design is a methodological improvement over the majority of previous studies, observational assessments used to measure both marital and parenting variables and findings may have capitalized on shared method variance. Fourth, contemporaneous assessments of marital and child rearing disagreement constructs precludes definitive ascertainment of the nature of directionality among these variables. Finally, pathways among study constructs tended to be modest in magnitude. Nevertheless, in the context of our conservative autoregressive models, even modest associations among family processes are regarded as substantively powerful and meaningful.

In summary, the current study extends prior research on marital conflict and parenting by demonstrating that relations between these constructs may vary by the type of conflict under study, the specific parenting dimension examined, and the gender of the parent involved in parenting. To our knowledge, this was the first study to simultaneously delineate longitudinal associations between marital hostility and withdrawal and the two distinct parenting dimensions of emotional unavailability and inconsistency in discipline. Differences in the impact of marital hostility and withdrawal on maternal and paternal parenting constructs as well as on the intermediary role of coparenting disagreements highlight the importance of distinguishing between specific types of marital conflict in examining differences in family pathways. In this regard, assessments and interventions with distressed families may benefit from expanding the focus on the marriage during therapeutic intervention to include other family process variables, such as coparenting and parenting practices. For example, increasing positivity, engagement, and agreeableness between parents and strengthening the coparenting partnership may advance both the positivity of the marital relationship and the quality of parenting in families. Finally, the results of this study indicate that current heterogeneity in the deleterious effects of marital conflict on parenting and coparenting constructs may be attributable, in part, to the narrow conceptualizations of marital conflict utilized in previous studies, and that advancement in understanding how marital conflict influences family processes depends upon increasing specificity in operationalizations of marital discord in future studies.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a National Institute of Mental Health grant (Project R01 MH57318) awarded to Patrick T. Davies and E. Mark Cummings. Melissa L. Sturge-Apple was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant F32 MH66596. We are grateful to the children, parents, teachers, and school administrators who participated in this project. Our gratitude is also expressed to the staff who assisted on various stages of the project, including Courtney Forbes, Courtney Henry, Marcie Goeke-Morey, Amy Keller, Michelle Sutton, and the graduate and undergraduate students at the University of Rochester and the University of Notre Dame.

Contributor Information

Melissa L. Sturge-Apple, Department of Clinical and Social Sciences in Psychology, University of Rochester

Patrick T. Davies, Department of Clinical and Social Sciences in Psychology, University of Rochester

E. Mark Cummings, Department of Psychology, University of Notre Dame.

References

- Arbuckle JL, Wothke W. Amos 4. 0 user’s guide. Chicago: Smallwaters Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Crnic K, Gable S. The determinants of coparenting in families with toddler boys: Spousal differences and daily hassles. Child Development. 1995;66:629–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Youngblade L, Rovine M, Volling B. Patterns of marital change and parent–child interaction. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1991;53:487–498. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen A, Heavey CL. Gender and social structure in demand/withdraw pattern of marital conflict. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;59:73–81. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.59.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CP, Cowan PA. When partners become parents: The big life change for couples. New York: Basic Books, Inc; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan PA, Cowan CP. Interventions as tests of family systems theories: Marital and family relationships in children’s development and psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:731–760. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402004054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Paley B. Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology. 1997;48:243–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Paley B, Payne CC, Burchinal M. The transition to parenthood: Marital conflict and withdrawal and parent-infant interactions. In: Cox MJ, Brooks-Gunn J, editors. Conflict and cohesion in families: Causes and consequences. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1999. pp. 87–104. [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg S, Covey L. Marital conflict and externalizing behavior in children. In: Cicchetti D, Toth S, editors. Rochester Symposium on Developmental Psychopathology: Models and integrations. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 1991. pp. 235–260. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies P. Children and marital conflict: The impact of family and dispute resolution. New York: Guilford Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Harold GT, Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings EM. Child emotional security and interparental conflict. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2002;67(3):1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Lindsay L. Does gender moderate the effects of conflict on children? In: Grych JH, Fincham FD, editors. Interparental conflict and child development: Theory, research, and application. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 64–97. [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Sturge-Apple ML, Cummings EM. Interdependencies among interparental discord and parenting practices: The role of adult attributes and relationship characteristics. Developmental Psychopathology. 2004;16:773–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Windle M. Gender-specific pathways between maternal depressive symptoms, family discord, and adolescent adjustment. Developmental Psychology. 1997;72:657–668. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.4.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dix T. The affective organization of parenting: Adaptive and maladaptative processes. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:3–25. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Rocher Schudlich TD, Papp LM, Cummings EM. Relations of husbands’ and wives’ dysphoria to marital conflict resolution strategies. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:171–183. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easterbrooks MA, Emde RN. Marital and parent–child relationships: The role of affect in the family system. In: Hinde R, Stevenson-Hinde J, editors. Relationships within families. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 1988. pp. 83–103. [Google Scholar]

- Emery RE. Interparental conflict and social policy. In: Grych JH, Fincham FD, editors. Interparental conflict and child development: Theory, research, and application. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 417–439. [Google Scholar]

- Erel O, Burman B. Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent–child relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118:108–132. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauber R, Forehand R, Thomas A, Wierson M. A mediational model of the impact of marital conflict on adolescent adjustment in intact and divorced families: The role of disrupted parenting. Child Development. 1990;61:1112–1123. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Pitts SC, Hill NE, Roosa MW. A mediational model of the impact of interparental conflict on child adjustment in a multiethnic, low-income sample. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14:365–379. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.3.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM. The roles of conflict engagement, escalation, and avoidance in marital interaction: A longitudinal view of five types of couples. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:6–15. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Levenson RW. Marital processes predictive of later dissolution: Behavior, physiology and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63:221–233. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH. Marital relationships and parenting. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting. 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, Inc; 2002. pp. 203–225. [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Harold GT, Miles CJ. A prospective investigation of appraisals as mediators of the link between interparental conflict and child adjustment. Child Development. 2003;74:1176–1193. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harold GT, Conger RD. Marital conflict and adolescent distress: The role of adolescent awareness. Child Development. 1997;68:333–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles E, Murphy C, Farris A, Smith D, Richters J, Waters D. Marital adjustment, parental disagreements about child rearing, and behavior problems in boys: Increasing the specificity of marital assessment. Child Development. 1991;62:1424–1433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LF, Gottman JM. Spillover effects of marital conflict: In search of parenting and coparenting mechanisms. New Directions for Child Development. 1996;74:57–76. doi: 10.1002/cd.23219967406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:130–149. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby E, Martin JA. Socialization in the context of the family: Parent–child interaction. In: Mussen P, editor. Handbook of child psychology. New York: Wiley; 1983. pp. 1–101. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik NM, Lindahl KM. System for coding interactions in dyads (SCID) In: Kerig PK, Baucom DH, editors. Couple observational coding systems. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2004. pp. 173–188. [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, Gordis EB, John RS. Coparenting: A link between marital conflict and parenting in two-parent families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:3–21. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale JP. Coparenting and triadic interactions during infancy: The roles of marital distress and child gender. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:85–996. [Google Scholar]

- McHale JP, Kazali C, Rotman T, Talbot J, Carleton M, Lieberson R. The transition to coparenthood: Parents’ prebirth expectations and early coparental adjustment at 3 months postpartum. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:711–734. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404004742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, Conger RD. The Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales: Instrument summary. In: Kerig PK, Lindahl KM, editors. Family observational coding systems: Resources for systemic research. Philadelphia: Brunner/Mazel; 2001. pp. 33–58. [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin S. Families and family therapy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Owen MT, Cox MJ. Marital conflict and the development of infant-parent attachment relationships. Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11:152–164. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit GS, Laird RD, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Criss M. Antecedents and behavior-problem outcomes of parental monitoring and psychological control in early adolescence. Child Development. 2001;72:583–598. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoneman Z, Brody GH, Burke M. Marital quality, depression and inconsistent parenting: Relationship with observed mother–child conflict. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1989;59:105–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1989.tb01639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturge-Apple ML, Davies PT, Boker SM, Cummings EM. Interparental discord and parenting: Testing the moderating role of child and parent gender. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2004;4:365–384. [Google Scholar]