Abstract

When information is incomplete but a choice must be made, individuals sometimes can rely on past experiences to help them assess uncertain outcomes in terms of the probabilities of payoffs. Monkeys (Cebus apella) and humans (Homo sapiens) were presented with a test in which they first made quantity judgments between two clear options. Then, they made choices where only one option was visible, and they had to estimate the quantity in the other option. Both species were guided by past outcomes, as they shifted from selecting the known option to selecting the unknown option at the point at which the known option went from being more than the average rate of return to less than the average rate of return. This comparability across species suggests that tallying ongoing average rates of return from repeated choices occurs spontaneously and likely serves an adaptive purpose when dealing with uncertainty in the environment.

Keywords: Quantity judgment, Estimation, Uncertainty, Humans, Monkeys, Decision-making

Uncertainty is a common feature of daily life, both for humans and for other animals. For example, leaving one food source to travel to another one that is both spatially and temporally distant requires some sense on the part of an organism that the latter source is more profitable than the current one (e.g., Stephens & Krebs 1986). Another area in which uncertainty is relevant pertains to quantity judgment. What one means in saying a “bird in the hand is worth two in the bush” is that the “two in the bush” are an uncertain outcome, and thus may be less viable than sticking with what one has.

Some animals appear to deal with uncertainty adaptively by seeking information or refusing to make a choice when the risk of error is high (e.g, Call & Carpenter, 2001; Hampton, Zivin, & Murray, 2004; Kornell, Son, & Terrace, 2007; Smith, Shields, & Washburn, 2003; Suda-King, 2008). However, there are other ways to deal with uncertainty, and one is to rely on past experiences to estimate the likelihood of current outcomes. For example, one may not know whether the next roll of the roulette wheel will come up black or red, but observations of the table over a long enough period of time will indicate that both outcomes are equally likely. It is the sum of the observations that produces the estimate of likelihood for each outcome, even if one cannot see that the wheel itself has equal slots for each color. This kind of estimation on the basis of summed experience can produce efficient decision making.

Nonhuman animals may well be capable of this kind of tallying behavior. Animals track the rates of return from multiple food sources within foraging bouts (e.g. Stephens & Krebs 1986). They track relative reinforcement rates for multiple response schedules (Herrnstein 1961), often matching responses to probabilities of reward on those schedules (Herrnstein 1997; Sugrue, Corrado, & Newsome 2004). Less studied are circumstances in which animals are given repeated experience with discrete judgments that are each unique along a quantitative dimension. However, these experiences might lead to the formation of an expected value (or some other measure related to the approximate average number of items they received across these repeated experiences), and thus would be useful in dealing with choices made in circumstances with incomplete information (i.e., uncertainty).

Beran, Evans, and Harris (2009) asked whether, in the face of uncertainty, such as when the quantity in one set was unknown, chimpanzees would use information gathered from their own previous responses to deal with that uncertainty. First, chimpanzees made 15 consecutive judgments between two visible food sets that varied in the number of items across trials. Then, they were faced with the same combinations of set sizes for another 15 trials, but only one set was revealed while the other remained unknown, and the chimpanzees could choose either option. The chimpanzees made selections as if they were using an approximate mean number of items obtained in the first 15 trials to determine if the known quantity was large enough. So, it was the rate of return from responses in the first phase (when both sets were known) that guided the chimpanzees’ choice of the unknown set rather than some specific quantity that acted as a threshold for choosing the known or the unknown set.

The results with chimpanzees, however, were from highly trained individuals who had extensive experience in judging between quantities. In some cases, this experience has stretched across more than two decades of testing and involves dozens of different kinds of tests including those that require counting items, judging discrete and continuous quantities, responding to arithmetic manipulations, and being tested for long term-retention of numeral meaning (e.g., Beran, 2009). In addition, there was no way to directly compare their performance to that of humans as no relevant data were available. The present study offers the first such direct comparison between humans and a nonhuman species. If capuchin monkeys and humans perform similarly this would indicate that spontaneous, ongoing representations of reward amounts are widespread among primate species and may support adaptive responding in the face of uncertainty, such as can occur in the natural environments of these species.

Methods

Participants

Six capuchin monkeys were tested: Griffin (male, 12 years of age), Gabe (male, 11 years of age), Liam (male, 6 years of age), Lily (female, 12 years of age), Nala (female, 7 years of age), and Wren (female, 7 years of age). All were experienced in a variety of different cognitive tests, including some judgments of food quantities (e.g., Beran, Evans, Leighty, Harris, & Rice, 2008; Evans, Beran, Harris, & Rice, 2009). Thus, they had experiences that allowed them to recognize the value of quantity in making judgments, but they had much less experience than the previously tested chimpanzees.

39 humans from Georgia State University were tested (15 males, 15 females; mean age = 20.3 years, age range: 18 to 39 years). They performed the experiment for credit as part of various undergraduate class requirements in the psychology department.

Apparatus

Monkeys voluntarily separated from group mates into individual test enclosures positioned 107 cm off the floor. Food items were hidden under black plastic containers positioned at opposite ends of a shelf (60 cm wide, and 30 cm deep). The shelf was white plastic coated with a perforated black fabric (to keep reward items from rolling out of place). The shelf sat on top of a utility cart (107 cm tall) that allowed us to move both quantities toward a monkey at the same time.

Humans were tested at a table using similar materials as those used with the capuchin monkeys except that humans saw pennies instead of food pellets as the items to be quantified.

Design and Procedure

Each experimental session consisted of 30 trials. The first 15 trials constituted the training phase. An experimenter placed a blind between the apparatus and the participant. The experimenter then placed two quantities of items (food pellets for monkeys, pennies for humans) on opposite ends of the test area and then covered them with the containers. The experimenter removed the blind and then lifted the tin container on the left, allowing the participant to look at the quantity of items underneath for approximately two seconds before recovering it. The experimenter then revealed and recovered the other set (on the right) in the same manner. For monkeys, the experimenter closed his eyes and lowered his head (so as not to influence the monkey’s choice) and immediately pushed the bench shelf forward so that the monkey could make a selection by sticking a finger through the cage mesh and pressing one of the containers. A second experimenter, out of view of the monkeys, called out which container was selected so the first experimenter would know which quantity to uncover and give to the monkey. The barrier was then lowered again, and the next trial was prepared. For humans, only one experimenter played both the role of presenter and recorder of the choice, and human participants simply pointed to the container that they wanted. Prior to this, human participants were told:

“Thank you for being in this experiment. Your task is to try to collect as many pennies as possible during this experiment. I will put a barrier between us while I set pennies under each of these two containers. Next, I will move the barrier and uncover and recover each container one at a time. Then, I will ask you to point to the container you think holds more pennies. I will put the pennies from the set you chose into the cup. I will then replace the barrier and remove the pennies from the set you did not choose.”

In the test phase, a second block of 15 trials was presented. Trials were prepared in the same way (out of view of the participant), and the experimenter revealed the first set in the same way. However, the experimenter never revealed the second set. Instead, the experimenter paused for two seconds and then allowed the participant to make a choice. This meant that the second set contained a quantity unknown to the participant at the point of the response. All other aspects of trial presentation were the same. Before these trials, human participants were told:

“Now, we will do the same thing as before, except I will only show you what is under one container. You must decide whether to take that amount of pennies or choose the other set which you have not seen. As before, I will put the pennies from the set you chose into the cup and then remove the other pennies after replacing the barrier. And, as before, your job is to try to get the largest amount of pennies on each trial.”

These instructions were considered necessary because during pilot data collection, humans would immediately ask us why or remind us that the second set had not been revealed. Thus, these instructions were more than monkeys could possibly have been given, but monkeys also had extensive experience in choice tests of various kinds, so there was no way to perfectly equate the testing experiences of the two species.

Each monkey received one session per day for two or three days each week. In each session, six different quantities were presented during trials, and each possible combination was presented one time during the 15 training trials (when both sets were revealed) and one time during the 15 test trials (when only one set was revealed). The order in which these 15 comparisons were presented was randomly determined for both phases, and position of the larger set was randomized in both phases.

We presented three quantity ranges: 1 to 6 (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6), 2 to 10 (2, 3, 5, 6, 8 and 10), and 5 to 12 (5, 6, 7, 8, 10 and 12). This allowed us to assess how the monkeys varied their selections of the unknown quantity as a function of the known quantity and as a function of the overall rate of reward they had received during the training phase. Each monkey completed three test sessions with each of the three quantity ranges for a total of nine sessions. The order of completion within a block was randomized for each monkey. Importantly, 80% sessions were separated by multiple days, to minimize any carryover of memory for trials from one session to the next.

Thirty of the 39 human participants completed only a single session of 30 trials (15 training and 15 test trials) from one of the three ranges. The range was randomly assigned to the 30 participants so that 10 participants were assigned to each range. The remaining nine participants came to the laboratory on three separate days to perform each of the three quantity range tests. Order of range used in the test session was randomized across these participants.

Results

During the training phase, the capuchin monkeys selected the larger quantity in 247 of 270 trials (91.5%) when the range was 1 to 6 items, 246 of 270 trials (91.1%) when the range was 2 to 10 items, and 239 of 270 trials (88.5%) for the range of 5 to 12 items. Humans in the between-subjects design selected the larger quantity in 150 of 150 trials (100%) when the range was 1 to 6 items, 146 of 150 trials (97.3%) when the range was 2 to 10 items, and 148 of 150 trials (98.7%) for the range of 5 to 12 items. Humans in the within-subjects design selected the larger quantity in 130 of 135 trials (96.3%) when the range was 1 to 6 items, 132 of 135 trials (97.8%) when the range was 2 to 10 items, and 131 of 135 trials (97.0%) for the range of 5 to 12 items. Each of these performance levels was significantly higher than chance levels of responding as assessed with a two-tailed binomial test (p < 0.01).

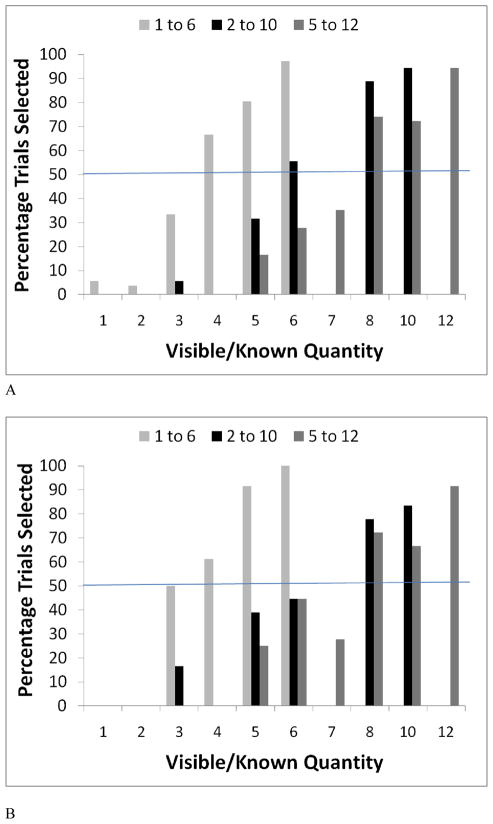

In the test phase, all trials were combined across monkeys for each known quantity in each of the three conditions. Figure 1a presents the percentage of all test trials in which the monkeys selected the unknown quantity as a function of the known quantity for each range of values presented during the training phase. Monkeys’ overall selection frequencies of the unknown quantity differed from chance levels (50%) in nearly all cases, either because the monkeys were significantly more likely than chance to choose the unknown quantity or significantly less likely than chance to choose the unknown quantity (all p < 0.05 as assessed with a two-tailed binomial test). The only exception was for the quantity 6 when the training range was 2 to 10, where selections did not exceed chance levels between the two choices.

Figure 1.

The percentage of trials in which the capuchins selected the known quantity during the test phase. Each series shows performance for a different range of quantities presented during individual sessions. The horizontal line shows the 50% level which indicates indifference between the choices. A Panel: All data are combined across monkeys; B Panel: Data combined across monkeys for the first session only for each quantity range.

Figure 1b presents a subset of the monkey data, now only for the first session completed by each monkey with each quantity range. This analysis is offered in comparison to the overall data to demonstrate that the phenomenon emerged very early in the experiment and was not the result of behavior changing with experience. The percentages of choosing the quantities shared across all ranges were significantly different across the three ranges (known quantity 5: χ2 (df = 2) = 12.22, p = 0.002; known quantity 6: χ2 (df = 2) = 11.43, p = 0.003).

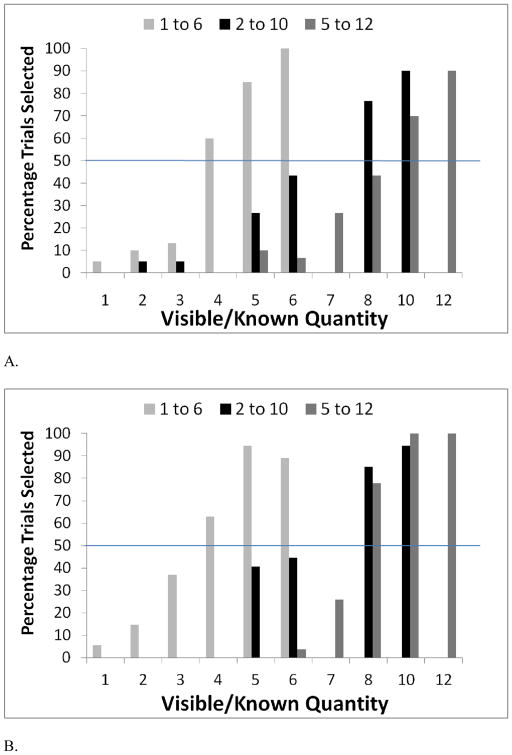

The performance of the humans was highly consistent with that of the monkeys (Figure 2). Their overall selection frequencies of the unknown quantity also differed from chance levels (50%) in nearly all cases (all p < 0.05 as assessed with a two-tailed binomial test). The only exceptions for the 30 participants in the between-subjects design were for the quantity 4 when the training range was 1 to 6, the quantity 6 when the training range was 2 to 10, and the quantity 8 when the range was 5 to 12. The only exceptions for the nine participants in the within-subjects design were for the quantities 3 and 4 when the training range was 1 to 6 and the quantities 5 and 6 when the training range was 2 to 10.

Figure 2.

The percentage of trials in which humans selected the known quantity during the test phase. All data are combined across participants. Each series shows performance for a different range of quantities presented during individual sessions. The horizontal line shows the 50% level which indicates indifference between the choices. A Panel: Data for the 30 participants in the between-subjects design. B Panel: Data for the nine participants in the within-subjects design.

Each of the three quantity ranges shared two common known quantities – five items and six items. Thus, we could assess whether either group of participants had a threshold quantity that determined choice of the known or unknown set. For monkeys, the proportions of choice of those known quantities were significantly different across the three ranges (known quantity 5: χ2 (df = 2) = 34.05, p < 0.001; known quantity 6: χ2 (df = 2) = 42.19, p < 0.001. For humans in the between-subjects design, the proportions of choice also were significantly different across the three ranges (known quantity 5: χ2 (df = 2) = 26.88, p < 0.001; known quantity 6: χ2 (df = 2) = 42.48, p < 0.001. For humans in the within-subjects design, the proportions of choice were significantly different across the three ranges (known quantity 5: χ2 (df = 2) = 18.08, p < 0.005; known quantity 6: χ2 (df = 2) = 32.89, p < 0.001. A comparison of the graphs in Figure 2a and Figure 2b shows that performance was highly similar for the between-subjects and within-subjects participants in this experiment.

Humans came closer than monkeys to using the mean number of items obtained in the training phase to guide their choice of the unknown quantity. For the range of 1 to 6 items, the mean number of items obtained per trial, assuming perfect performance in which every trial ended with choice of the larger set, was 4.67 items. Humans showed indifference between the two choices when the known set was 4 items, whereas capuchins significantly preferred the known set of four items. For the range of 2 to 10 items, the mean number of items obtained per trial, assuming perfect performance, was 7.53 items. Humans shifted from selecting the unknown quantity to the known quantity between the six- and eight-item known quantities, whereas capuchins already were indifferent between the choices when the known quantity was six items. For the range of 5 to 12 items, the mean number of items obtained per trial, assuming perfect performance, was 9.53 items. Humans in the between-subjects test shifted from selecting the unknown quantity to the known quantity between the eight- and 10-item known quantities, whereas capuchin monkeys and humans in the within-subjects test significantly preferred receiving the eight items in the known set when it was presented. Thus, in nearly all cases humans’ indifference points in choosing between the two sets were as close to the mean number of items received during training as could have occurred given the actual comparisons that were used. Capuchin monkeys consistently were underestimating that mean. It should be noted that this pattern for capuchins still holds even if one uses the actual mean number of items obtained during training rather than the theoretical number. If all correctly completed training trials for the capuchins are used to calculate the mean number of items obtained across the three ranges, those values drop to 4.53, 7.36, and 9.32, which are all very close to the means obtained assuming perfect performance during the training trials.

Discussion

Monkeys and humans performed very similarly in this experiment when faced with one known and one unknown quantity. Both species showed nearly the same distribution of responses to the two quantities used in all three ranges used in the experiment. This performance matched that of chimpanzees previously tested (Beran et al., 2009). Because capuchin monkeys are a New World monkey species distantly related to chimpanzees and humans, this shows that the capacity to estimate likely outcomes in uncertain situations is widespread among primate taxa. Further, because the capuchin monkeys live in a similar laboratory setting to the previously tested chimpanzees, but without the enriched rearing that those chimpanzees experienced, this capacity is not reliant on any special training or rearing.

Monkeys and humans, like previously-tested chimpanzees, did not choose between known and unknown quantities on the basis of some absolute, or threshold, amount. This is evidenced by their differential responding to the quantities 5 and 6 across the three different quantity ranges. Thus, all three species clearly showed that any prediction regarding their choice of an unknown set would need to take into account not only the known quantity or the unknown quantity but also what occurred earlier in the test session. Capuchin monkeys and humans were keeping track of the relative rates of return from their selections across the first 15 training trials and using information from those trials to guide responding in the face of uncertainty. Humans were better at this, as their indifference points nearly always fell exactly where predicted if the mean number of items obtained during the training trials was used to guide responding. Capuchins underestimated the means. This difference may have been partly the result of using edible items with animals and small-valued symbolic stimuli (pennies) with humans. Had food items or larger-value coins been used, humans might have performed differently due to increased motivation that might have affected relative rates of risk-aversion responses versus risk-taking responses. However, this seems unlikely given that the use of different rewards has been shown to not change choice behavior in monkeys or humans in other tasks (e.g., Hayden & Platt, 2009). Thus, it is more likely that humans are better at estimating the relative rates of return from numerous quantity judgments, due perhaps to more precise representations of quantity and number than are formed by nonhuman animals (e.g., Gallistel & Gelman, 2000).

The task never instilled any requirement that participants remember anything from one trial to the next during the training phase. Everything was visible, and choices were made with full knowledge of both set sizes. Even beyond that, the entire testing history of these animals followed the same principle. Success or failure in choosing the larger amount in all previous quantity judgment experiments was based solely on what was seen on a given trial. Retaining information about a trial, for possible use in subsequent trials, offered no benefit whatsoever to the animal for any of its previous experiences. And yet, monkeys (and humans) spontaneously tracked the cumulative rewards they were obtaining through those training trials. Doing so clearly served an adaptive role later in the session, even though participants could not have known this during the training phase. This was true for all sessions with humans tested in the between-groups design and at least for the first session with monkeys and humans tested in the within-subjects design. Thus, these judgments in the face of incomplete information were made spontaneously, as this was the first time these monkeys (and perhaps these humans) ever were faced with such quantity judgments with incomplete information.

Although learning something about the overall reward structure of a task offers a source of information that could be used in the face of uncertainty, this is not the same kind of learning that occurs through trial and error, or trial by trial feedback in terms of rewards or punishments. Instead, it is a kind of “record keeping” whereby presently useless information is still tallied and retained. Although this is most likely done implicitly, especially in the nonhuman species, it still occurs, and apparently it occurs across a variety of primates – at least those with extensive experimental histories. These monkeys used session-by-session information to guide their responses when information was incomplete. Questions remain, however, about whether less experimentally sophisticated animals would show this same pattern, and so there needs to be more research to assess both the extent to which untested species might also show this phenomenon, and to assess the role of previous experiences in performance on this kind of task. It remains to be seen if non-primates or experimentally naïve primates perform similarly to those already tested, but it seems reasonable to assume that they can. Research has indicated that a variety of species ranging from insects to birds to mammals perform in highly similar ways when they judge quantities (e.g., Agrillo, Dadda, Serena, & Bisazza 2008; Anderson, Hattori, & Fujita, 2008; Boysen & Berntson, 1989; Brannon & Terrace, 2000; Call, 2000; Dack & Srinivasan, 2008; Pepperberg, 1994; Tomonaga, 2007). Those skills clearly offer the basis for the type of implicit “calculations” that would support adaptive decision making in the face of uncertain options in this quantity judgment task – decision making like that shown by the primates given such tests so far.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants HD38051, HD060563, and HD061455 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and by grant BCS-0924811 from the National Science Foundation.

Contributor Information

Michael J. Beran, Email: mjberan@yahoo.com, Language Research Center, Georgia State University, University Plaza, Atlanta, GA 30302

Katharine Owens, Department of Psychology, Georgia State University;.

Holly A. Phillips, Department of Psychology, Georgia State University

Theodore A. Evans, Language Research Center, Georgia State University

References

- Agrillo C, Dadda M, Serena G, Bisazza A. Do fish count? Spontaneous discrimination of quantity in female mosquitofish. Animal Cognition. 2008;11:495–503. doi: 10.1007/s10071-008-0140-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JR, Hattori Y, Fujita K. Quality before quantity: Rapid learning of reverse-reward contingency by capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella) Journal of Comparative Psychology. 2008;122:445–448. doi: 10.1037/a0012624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beran MJ. Chimpanzees as natural accountants. Human Evolution. 2009;24:183–196. [Google Scholar]

- Beran MJ, Evans TA, Harris EH. When in doubt, chimpanzees rely on estimates of past reward amounts. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2009;276:309–314. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beran MJ, Evans TA, Leighty K, Harris EH, Rice D. Summation and quantity judgments of sequentially presented sets by capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella) American Journal of Primatology. 2008;70:191–194. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boysen ST, Berntson GG. Numerical competence in a chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) Journal of Comparative Psychology. 1989;103:23–31. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.103.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannon EM, Terrace HS. Representation of the numerosities 1–9 by rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 2000;26:31–49. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.26.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Call J. Estimating and operating on discrete quantities in orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus) Journal of Comparative Psychology. 2000;114:136–147. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.114.2.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Call J, Carpenter M. Do apes and children know what they have seen? Animal Cognition. 2001;4:207–220. doi: 10.1007/s100710100078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dacke MSMV. Evidence for counting in insects. Animal Cognition. 2008;11:683–689. doi: 10.1007/s10071-008-0159-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans TA, Beran MJ, Harris EH, Rice D. Quantity judgments of sequentially presented food items by capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella) Animal Cognition. 2009;12:97–105. doi: 10.1007/s10071-008-0174-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallistel CR, Gelman R. Non-verbal numerical cognition: From reals to integers. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2000;4:59–65. doi: 10.1016/S1364-6613(99)01424-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampton RR, Zivin A, Murray EA. Rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) discriminate between knowing and not knowing and collect information as needed before acting. Animal Cognition. 2004;7:239–246. doi: 10.1007/s10071-004-0215-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden BY, Platt ML. Gambling for Gatorade: Risk sensitive decision making for fluid reward in humans. Animal Cognition. 2009;12:201–207. doi: 10.1007/s10071-008-0186-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrnstein RJ. Relative and absolute strength of response as a function of frequency of reinforcement. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1961;4:267–272. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1961.4-267.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrnstein RJ. The matching law: Papers in psychology and economics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kornell N, Son LK, Terrace HS. Transfer of metacognitive skills and hint seeking in monkeys. Psychological Science. 2007;18:64–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepperberg IM. Numerical competence in an African Grey parrot (Psittacus erithacus) Journal of Comparative Psychology. 1994;108:36–44. doi: 10.1037//0735-7036.108.1.36. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Shields WE, Washburn DA. A comparative approach to metacognition and uncertainty monitoring. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2003;26:317–339. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x03000086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens DW, Krebs JR. Foraging theory. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Suda-King C. Do orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus) know when they do not remember? Animal Cognition. 2008;11:21–42. doi: 10.1007/s10071-007-0082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugrue LP, Corrado GS, Newsome WT. Matching behavior and the representation of value in the parietal cortex. Science. 2004;304:1782–1787. doi: 10.1126/science.1094765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomonaga M. Relative numerosity discrimination by chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes): Evidence for approximate numerical representations. Animal Cognition. 2007;11:43–57. doi: 10.1007/s10071-007-0089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]