SUMMARY

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterised, not only by cognitive deficits and neuropathological changes, but also by several non-cognitive behavioural symptoms that can lead to a poorer quality of life. Circadian disturbances in core body temperature and physical activity are reported in AD patients, although the cause and consequences of these changes are unknown. We therefore characterised circadian patterns of body temperature and activity in male triple transgenic AD mice (3xTgAD) and non-transgenic (Non-Tg) control mice by remote radiotelemetry. At 4 months of age, daily temperature rhythms were phase advanced and by 6 months of age an increase in mean core body temperature and amplitude of temperature rhythms were observed in 3xTgAD mice. No differences in daily activity rhythms were seen in 4- to 9-month-old 3xTgAD mice, but by 10 months of age an increase in mean daily activity and the amplitude of activity profiles for 3xTgAD mice were detected. At all ages (4–10 months), 3xTgAD mice exhibited greater food intake compared with Non-Tg mice. The changes in temperature did not appear to be solely due to increased food intake and were not cyclooxygenase dependent because the temperature rise was not abolished by chronic ibuprofen treatment. No β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques or neurofibrillary tangles were noted in the hypothalamus of 3xTgAD mice, a key area involved in temperature regulation, although these pathological features were observed in the hippocampus and amygdala of 3xTgAD mice from 10 months of age. These data demonstrate age-dependent changes in core body temperature and activity in 3xTgAD mice that are present before significant AD-related neuropathology and are analogous to those observed in AD patients. The 3xTgAD mouse might therefore be an appropriate model for studying the underlying mechanisms involved in non-cognitive behavioural changes in AD.

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a chronic progressive neurodegenerative disorder that is characterised by the accumulation of extracellular β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques, neurofibrillary tangles composed of hyperphosphorylated tau, neuronal loss and neuroinflammation (Frank-Cannon et al., 2009; Ballard et al., 2011). AD patients present with complex cognitive impairment, memory loss being one of the earliest clinical symptoms. Patients with AD also suffer from non-cognitive behavioural symptoms, such as depression, anxiety, agitation, weight loss, hyperactivity and disturbed circadian rhythms and sleep (Assal and Cummings, 2002; Gillette-Guyonnet et al., 2007; Bombois et al., 2010; Klaffke and Staedt, 2006; Stoppe et al., 1999; Finkel, 2003). These non-cognitive behavioural symptoms might not simply be a consequence of AD neuropathology, but instead could be a predictor of the disease. Furthermore, non-cognitive behavioural changes in AD can lead to a poorer quality of life and, in cases such as severe weight loss, can be life-threatening (White et al., 1998; White et al., 2004). In spite of their serious consequences, most non-cognitive changes in AD remain poorly understood. Understanding when and how these non-cognitive symptoms of AD occur could lead to a better quality of life for AD patients.

Frequently reported non-cognitive changes in AD patients include disruptions in the circadian rhythms of locomotor activity and core body temperature, usually characterised by an increase in nocturnal activity and a raised body temperature (Touitou et al., 1986; Okawa et al., 1991; Okawa et al., 1995; Satlin et al., 1995; Mishima et al., 1997; Volicer et al., 2001; Harper et al., 2001; Harper et al., 2004; Harper et al., 2005; Klegeris et al., 2007). To better understand the aetiology and progression of AD, several mouse models have been developed that harbour mutations linked to human AD, including amyloid precursor protein (APP) and presenilin 1 (PS1) and PS2. These mice develop some of the pathological and cognitive features observed in human AD (Hall and Roberson, 2011; Braidy et al., 2011). Several transgenic AD mouse models also exhibit increases in spontaneous and natural locomotor activity, comparable to AD patients (Huitrón-Reséndiz et al., 2002; Bedrosian et al., 2011; Richter et al., 2008; Ambrée et al., 2006; Vloeberghs et al., 2004; Sterniczuk et al., 2010; Van Dam et al., 2003). Furthermore, mice expressing human mutant APP have an altered core body temperature at an age when significant Aβ plaque deposition is present (Huitrón-Reséndiz et al., 2002). However, the evidence for longitudinal core body temperature changes in AD mouse models prior to significant pathology is limited. Furthermore, most of these studies measuring activity and temperature have been performed in mice that present with Aβ plaques only, such as the Tg2576 mouse. Triple transgenic (3xTgAD) mice have mutations in APP, PS1 and tau and, as a consequence, progressively develop both Aβ plaques and neurofibrillary tangles with a temporal and regional-specific profile characteristic of human AD (Oddo et al., 2003). Disruptions in locomotor activity have been reported in 3xTgAD mice but core body temperature is yet to be studied (Sterniczuk et al., 2010).

TRANSLATIONAL IMPACT.

Clinical issue

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is usually thought as of a disease that affects memory and cognition. However, AD patients also suffer from many non-cognitive symptoms that can severely impact their quality of life. Such changes include alterations in the circadian rhythms of core body temperature and physical activity. Understanding when and how these changes occur, and identifying their relationship to disease pathology, will increase the chance of developing potential therapies.

Results

The authors addressed this issue by characterising circadian patterns of body temperature and activity in an animal model of AD, the triple transgenic AD mouse (3xTgAD). The first apparent change was an advance in the daily temperature rhythms in 4-month-old 3xTgAD mice; by 6 months of age, mean body temperature and the amplitude of temperature rhythms were increased. No changes in activity were noted until 10 months of age, when mean activity and amplitude of activity rhythms were found to be higher in 3xTgAD mice than in controls. All of these changes occurred before significant AD-related pathology because amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles were detected after 10 months of age. Increased temperature in old 3xTgAD mice did not appear to be caused solely by increased food consumption or mediated by cyclooxygenase-driven prostaglandin production.

Implications and future directions

In summary, this study demonstrates age-dependent changes in body temperature and activity that occur before overt neuropathology in 3xTgAD mice. The changes observed resemble those reported in AD patients, suggesting that these mice are an appropriate model for studying the mechanisms underlying non-cognitive symptoms associated with AD.

Mechanisms underlying the changes in core body temperature in AD patients are unknown. The anterior hypothalamus is the key site within the brain that regulates body temperature, and both pathological and neurochemical changes in the human hypothalamus has been observed in post-mortem tissue from patients with AD (Ishii, 1966; Saper and German, 1987; Goudsmit et al., 1990; Standaert et al., 1991; Swaab et al., 1992; Zhou et al., 1995; Stopa et al., 1999; Liu et al., 2000). It is not yet known whether the pathological findings within the hypothalamus are responsible for the disruptions in thermoregulation in human AD and when they develop. Furthermore, it is not clear whether AD pathology, such as Aβ plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, is present in the hypothalamus of transgenic mouse models of AD.

Neuroinflammation is a feature of AD that is observed in both AD patients and transgenic mouse models of AD (Heneka et al., 2010; Johnston et al., 2011) and is characterised by cytokine production and microglia and astroctye activation. Several cytokines can act as endogenous pyrogens to mediate the febrile response to peripheral infection and inflammation by acting within the anterior hypothalamus to induce expression of prostaglandins (PG), such as PGE2, via the action of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2). The expression of pyrogenic cytokines, COX-2 and PG in the brain, and PGE2 in the cerebral spinal fluid, are elevated in AD, especially in the early stages of the disease (Montine et al., 1999; Zagol-Ikapitte et al., 2005; Kitamura et al., 1999). Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen, reduce inflammatory responses and are anti-pyretic through COX inhibition. It is possible therefore that the raised core body temperature in AD patients is due to a cytokine-driven increase in COX and PG production that elevates the set point for body temperature.

To define the contribution of non-cognitive parameters such as body temperature in AD, we performed a longitudinal analysis of core body temperature in 3xTgAD mice. Activity was also simultaneously assessed in order to correlate changes in activity with core body temperature. To examine underlying mechanisms responsible for changes in temperature, we firstly examined the hypothalamus for gross AD-related pathology. Because we have previously shown that 3xTgAD mice consume more food than control mice (Knight et al., 2012), we also tested whether hyperphagia could affect body temperature and activity by giving 3xTgAD mice restricted access to food. Finally, to determine the role of neuroinflammation on body temperature and activity, the effect of COX inhibition in 3xTgAD mice was determined.

RESULTS

Core body temperature, activity and food intake in 4- and 6-month-old mice

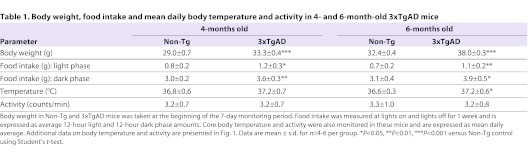

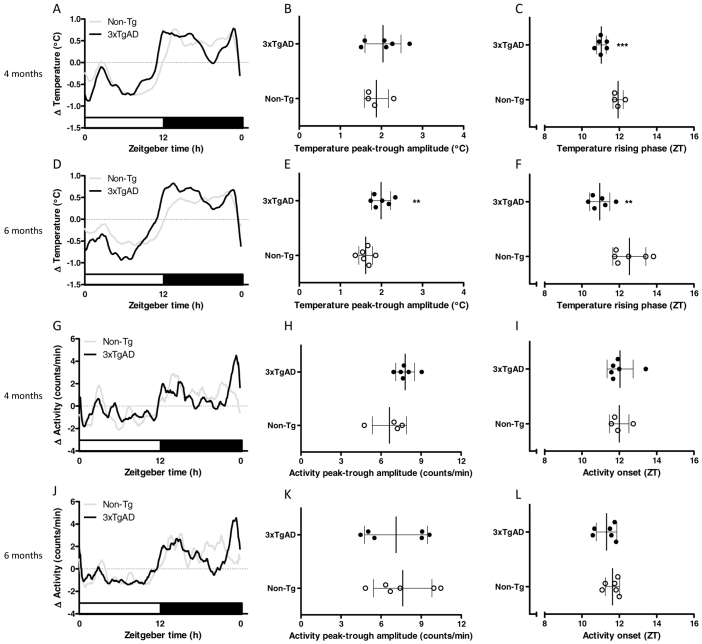

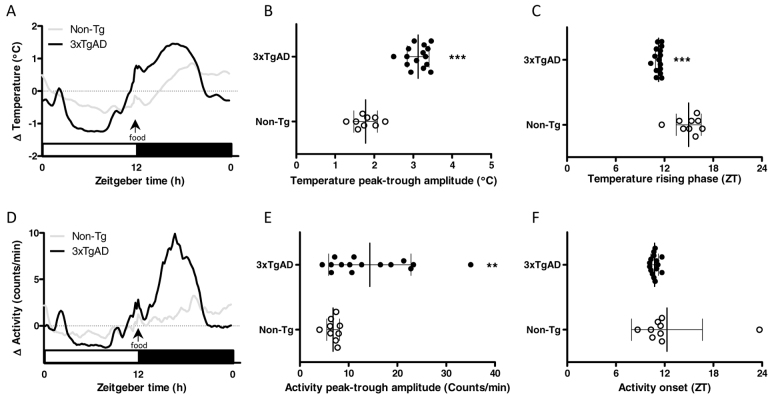

At 4 and 6 months of age, 3xTgAD mice weighed significantly more than Non-Tg controls (P<0.001) and food intake during the light and dark phase was significantly increased (P<0.05 and P<0.01; Table 1). Both Non-Tg and 3xTgAD mice exhibited strong circadian rhythms in core body temperature at 4 and 6 months of age, with temperature being highest during the dark phase (Fig. 1A,D). At 4 months of age there was no significant difference between Non-Tg and 3xTgAD mice in either mean core body temperature (Table 1) nor the peak-trough amplitude of the daily temperature rhythm (Fig. 1B). However, a difference in timing of the daily rise in temperature was observed in 3xTgAD mice, such that the midpoint of this rising phase occurred ∼1 hour earlier compared with Non-Tg controls (P<0.001; Fig. 1C). At 6 months of age, this difference in the timing of daily temperature rhythms in 3xTgAD mice appeared slightly enlarged (P<0.01; Fig. 1F) and a significant increase in mean core body temperature (P<0.05; Table 1) and peak-trough amplitude of temperature rhythms (P<0.01; Fig. 1E) was now apparent in 3xTgAD mice. There were no significant differences in average activity levels (Table 1), nor in the timing or amplitude of daily activity rhythms between Non-Tg and 3xTgAD mice of either age group (Fig. 1G–L).

Table 1.

Body weight, food intake and mean daily body temperature and activity in 4- and 6-month-old 3xTgAD mice

Fig. 1.

Core body temperature and activity in 4- and 6-month-old 3xTgAD mice. (A–L) Core body temperature (°C) and activity (counts/minute) were monitored continuously by remote radiotelemetry over a 7-day period in separate groups of individually housed 3xTgAD and Non-Tg mice at 4 (temperature, AC; activity, G–I) and 6 (temperature, D–F; activity J–L) months of age. The mean 24-hour profiles over the 7 days (expressed as change, Δ) are illustrated in A and D for temperature and G and J for activity. White bars on the abscissa represent the light, inactive phase of the day; black bars represent the dark, active phase. The peak-trough amplitude in temperature rhythms was increased in 6-month-old 3xTgAD mice (E) but not in 4-month-old mice (B). A phase advance in the temperature rhythms was observed in both 4- (C) and 6- (F) month-old 3xTgAD mice. No change in the peak-trough amplitude or phase onset for activity rhythms was observed at 4 (H,I) and 6 (K,L) months of age. Data are expressed as mean ± s.d. and individual values for each animal are represented; n=4–6 per group. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 versus age-matched Non-Tg control mice using Student’s t-test.

Core body temperature, activity and food intake in 8- to 10-month-old mice

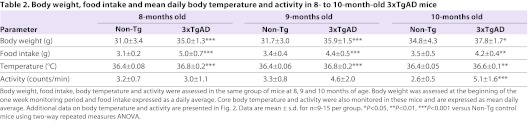

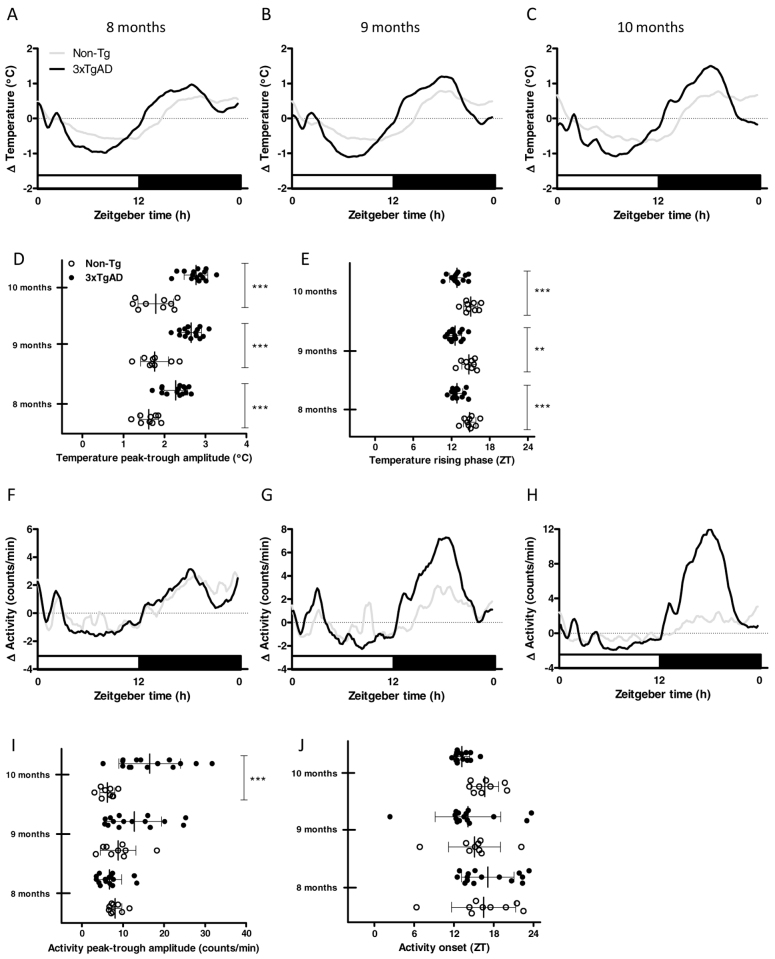

Core body temperature, activity, food intake and body weight were monitored longitudinally in a group of Non-Tg and 3xTgAD mice of between 8 and 10 months of age. Body weight and daily average food intake were significantly higher in 3xTgAD mice than in Non-Tg mice at 8, 9 and 10 months of age (Food intake: genotype F1,44: 56.72, P<0.001; interaction F2,44: 11.01, P<0.001. Bonferroni post-tests, P<0.001 at 8 and 9 months of age, P<0.01 at 10 months of age. Body weight: genotype F1,44: 14.08, P<0.01; age F2,44: 76.63, P<0.001. Bonferroni post-tests, P<0.001 at 8 and 9 months of age, P<0.05 at 10 months of age; Table 2). Mean core body temperatures were also higher in 3xTgAD mice than in Non-Tg mice over this age range (genotype F1,44: 37.74, P<0.001; interaction F2,44: 6.19; P<0.001; age F2,44: 15.15, P<0.001. Bonferroni post-tests, P<0.001 at 8 and 9 months of age, P<0.01 at 10 months of age; Table 2). In addition, a progressive increase in the peak-trough amplitude of daily temperature rhythms in 3xTgAD mice compared with age-matched controls was observed (Age F2,44: 15.11, P<0.001; genotype F1,44: 64.18, P<0.001; interaction F2,44: 3.569, P<0.05; Bonferroni post-tests, P<0.001 at 8, 9 and 10 months of age; Fig. 2A–D). As in 4- and 6-month-old 3xTgAD mice, daily temperature rhythms in these older animals were also consistently phase advanced relative to Non-Tg control mice (genotype F1,38: 18.79, P<0.001; Bonferroni post-tests, P<0.001 at 8 and 10 months and P<0.01 at 9 months; Fig. 2A–C,E). Although the magnitude of this effect on phase advancement appeared larger than was observed in the 4- and 6-month-old animals (∼2 hours earlier than age-matched controls), across the range studied there was no evidence of a progressive change in phasing (P>0.05 for age and genotype versus age).

Table 2.

Body weight, food intake and mean daily body temperature and activity in 8- to 10-month-old 3xTgAD mice

Fig. 2.

Core body temperature and activity in 8- to 10-month-old 3xTgAD mice. (A–I) Core body temperature (°C) and activity (counts/minute) were monitored continuously by remote radiotelemetry over a 7-day period at 8 (temperature, A; activity, F), 9 (temperature, B; activity, G) and 10 (temperature, C; activity, H) months of age in the same groups of individually housed 3xTgAD and Non-Tg mice. The mean 24-hour profiles over the 7 days (expressed as change,Δ) are illustrated in A–C for temperature and F–H for activity. Grey lines show Non-Tg mice and black lines 3xTgAD mice. White bars on the abscissa represent the light, inactive phase of the day whereas black bars represent the dark, active phase. The peak-trough amplitude in temperature rhythms was increased in 8, 9 and 10-month-old 3xTgAD mice (D). A phase advance in temperature rhythms was observed in 3xTgAD mice at all ages (E). An increase in peak-trough amplitude for activity rhythms in 3xTgAD mice was observed at 10 months of age (I) in the absence of any difference in the phase onset for activity rhythms (J). Data are expressed as mean ± s.d. and individual values for each animal are represented. Open circles, Non-Tg mice; black closed circles, 3xTgAD mice; n=9–15 per group. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 versus age-matched Non-Tg control mice using two-way repeated measures ANOVA.

By contrast with the effects observed on temperature rhythms, no significant effects of age or genotype on the timing of daily activity rhythms were detected in 8- to 10-month-old mice (Fig. 2F–H,J). However, a progressive increase in the amplitude of mean daily activity profiles for 3xTgAD mice compared with Non-Tg mice was observed (age F2,44: 4.79, P<0.05; genotype F1,44: 8.5, P<0.01; interaction F2,44: 9.02, P<0.001; Bonferroni post-tests P<0.001 at 10 months; Fig. 2F–H,I) and by 10 months of age an increase in mean activity levels was detected in 3xTgAD mice.

To test whether the increases in core body temperature and activity might be due to greater food intake, 3xTgAD mice were food restricted to the average ad-libitum amount eaten by Non-Tg control mice at 10 months of age (pair-feeding paradigm). Whereas pair feeding appeared to normalise mean daily body temperature in the 3xTgAD mice (Non-Tg, 36.4±0.07°C; 3xTgAD, 36.4±0.15°C; P>0.05), the increased amplitude and advanced timing of the phase for temperature was still present in 3xTgAD mice that were pair-fed to Non-Tg controls (Fig. 3A–C). The increased mean and amplitude of daily locomotor activity in these 3xTgAD mice was also maintained under pair-fed conditions (mean activity: Non-Tg, 2.8±0.7 counts/minute; 3xTgAD 4.4±1.9 counts/minute; P<0.05; Fig. 3D,E).

Fig. 3.

Increased food intake does not contribute to the changes in temperature and activity rhythms in 3xTgAD mice. (A–F) Core body temperature (A) and activity (D) were monitored continuously by remote radiotelemetry over a 5-day period in individually housed 3xTgAD and Non-Tg mice at 10 months of age. Non-Tg mice were given ad libitum access to food and 3xTgAD mice were food restricted (pair-fed) daily for 5 days by giving them access to the amount of food consumed by the Non-Tg mice the previous 24 hours. Food was presented at ZT 12 (lights out). White bars on the abscissa represent the light, inactive phase of the day; black bars represent the dark, active phase. An increase in the peak-trough amplitude for temperature (B) and activity (E) rhythms and a phase advance in temperature (C) was observed in 3xTgAD mice that ate the same amount of food as Non-Tg control mice. Data are expressed as mean ± s.d. and individual values for each animal are represented; n=9–15 per group. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 versus Non-Tg control mice.

Effect of ibuprofen on core body temperature in 3xTgAD mice

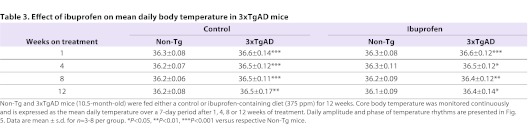

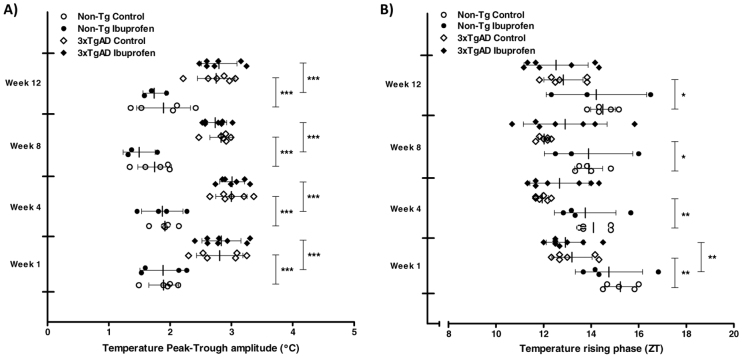

At 10.5 months of age, Non-Tg and 3xTgAD mice were maintained for 12 weeks on either a control diet or a diet containing ibuprofen (375 ppm). Core body temperature was assessed at 1, 4, 8 and 12 weeks of treatment. One Non-Tg and 3xTgAD mouse treated with ibuprofen had to be sacrificed during the 12 weeks of treatment. At all time points, average core body temperature (Table 3) and amplitude of temperature rhythms (Fig. 4A) were significantly increased in control-fed 3xTgAD versus Non-Tg mice. Ibuprofen had no effect on the mean temperature and amplitude in 3xTgAD mice and both measurements were significantly increased in ibuprofen-fed 3xTgAD mice compared with ibuprofen-fed Non-Tg mice at 1, 4, 8 and 12 weeks. As previously, daily temperature rhythms were advanced in control-fed 3xTgAD compared with Non-Tg mice; however, ibuprofen did not significantly affect this phase advancement as no difference was observed between 3xTgAD mice fed either a control or ibuprofen diet (Fig. 4B).

Table 3.

Effect of ibuprofen on mean daily body temperature in 3xTgAD mice

Fig. 4.

Ibuprofen does not affect the changes in core body temperature in 3xTgAD mice. (A,B) Core body temperature was monitored continuously by remote radiotelemetry in individually housed 3xTgAD and Non-Tg mice at 10.5 months of age. Mice were maintained on either a control diet or a diet containing ibuprofen (375 ppm) for 12 weeks. The mean daily peak-trough amplitude (°C; A) and phase (in ZT; B) of temperature rhythms over a 7-day period were calculated after 1, 4, 8 and 12 weeks of treatment. Data are mean ± s.d. for n=3–8 per group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 versus respective Non-Tg mice.

In order to test the efficacy of ibuprofen, C57BL/6 mice were given access to either an ibuprofen-containing (375 ppm) or control diet for 2 days prior to i.p. injection of LPS. In mice fed a control diet, LPS significantly increased core body temperature over 8 hours compared with vehicle-treated mice on a control diet (AUC for 0–8 hours: control diet/vehicle, 12±3.4°C×hour; control diet/LPS, 21.4±0.8°C×hour; P<0.05). Ibuprofen significantly inhibited the febrile effect of LPS as no difference in core body temperature was observed between vehicle-treated mice fed a control diet and LPS-treated ibuprofen-fed mice (AUC for 0–8 hours: control diet/vehicle, 12±3.4°C×hour; ibuprofen diet/LPS, 14.3±5.6°C×hour). Ibuprofen also inhibited the reduction in food intake observed 24 hours after i.p. LPS (control diet/vehicle 4.3±0.7 g; control diet/LPS 3.2±0.5 g; ibuprofen diet/LPS 4.2±0.6 g; P<0.05 for control diet/LPS versus control diet/vehicle).

Effect of ibuprofen on behaviour in 3xTgAD mice

Ibuprofen has been reported to reduce behavioural deficits in transgenic models of AD including 3xTgAD mice. In order to further test the efficacy of ibuprofen we assessed memory in all groups of mice after 12 weeks on either the control or ibuprofen-containing diet. Using the Y-maze spontaneous alternation task, 3xTgAD mice on a control diet displayed significantly fewer alternations compared with Non-Tg mice on a control diet (Non-Tg control, 54.0±16.8%; 3xTgAD control, 33.6±8.7%; P<0.05). Ibuprofen had no effect on the number of alternations in Non-Tg mice (Non-Tg control, 54.0±16.8%; Non-Tg ibuprofen, 55.3±4.7%; P>0.05) but inhibited the deficit in 3xTgAD mice as no difference in alternations was observed between Non-Tg and 3xTgAD mice fed an ibuprofen diet (Non-Tg ibuprofen, 55.3±4.7%; 3xTgAD ibuprofen, 52.8±12.7%).

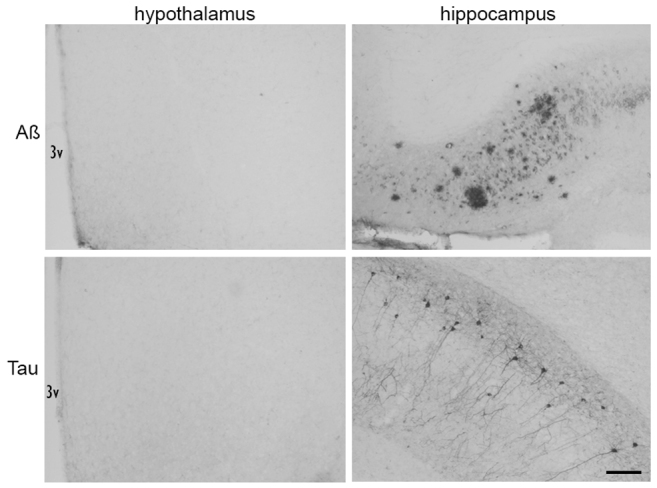

Hypothalamic AD pathology

No extracellular Aβ plaques (or Aβ-positive neurones) or hyperphosphorylated tau were identified in the hypothalamus (including the anterior hypothalamus that is involved in the regulation of body temperature) of 3xTgAD mice at 12 months of age (Fig. 5A,C). In the same group of 3xTgAD mice, Aβ plaques and neurones positive for hyperphosphorylated tau were found in the hippocampus (Fig. 5B,D) and amygdala (not shown). Intraneuronal Aβ-positive cells were also present in the cortex, hippocampus (Fig. 5B) and amygdala of 12-month-old 3xTgAD mice. No Aβ plaques (or Aβ-positive cells) or hyperphosphorylated tau were present in the brains of Non-Tg control mice for all brain regions examined.

Fig. 5.

Aβ plaques and neurofibrillary tangles are not present in the hypothalamus of 3xTgAD mice. Immunohistochemistry to detect Aβ plaques (top row) and neurofibrillary tangles (bottom row; hyperphosphorylated tau) was performed using 6E10 and AT8 antibodies, respectively, on brain sections from 12-month-old 3xTgAD mice. No Aβ plaques or neurofibrillary tangles were detected in the hypothalamus of 3xTgAD mice. Aβ plaques and neurofibrillary tangles were present in the hippocampus of 12-month-old 3xTgAD mice. 3V, third ventricle of the hypothalamus. Scale bar: 100 μm.

In separate groups of 3xTgAD mice of between 4 and 10 months of age, no extracellular Aβ plaques (or Aβ-positive cells) or hyperphosphorylated tau were identified in the hypothalamus. Although intraneuronal Aβ-positive cells were present in the cortex, hippocampus and amygdala in brain sections of 4- to 10-month-old 3xTgAD mice, no Aβ plaques or hyperphosphorylated tau were detected at these ages, apart from a few scattered Aβ plaques and neurones positive for hyperphosphorylated tau in 10-month-old mice.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates age-dependent changes in core body temperature and activity rhythms in male 3xTgAD mice. These start with an advance in the timing of core body temperature rhythms that is present by 4 months of age, and progress to include increases in rhythm amplitude and overall mean body temperature by 6 months of age. By contrast, activity rhythms in 3xTgAD mice remain similar to Non-Tg controls until 10 months of age when an increase in activity becomes apparent. These data are the first to fully characterise activity and temperature longitudinally, and to demonstrate changes in core body temperature in the 3xTgAD mouse. Increased spontaneous locomotor activity has been observed previously at various ages in other mouse models of AD including 3xTgAD mice (Huitrón-Reséndiz et al., 2002; Bedrosian et al., 2011; Richter et al., 2008; Ambrée et al., 2006; Vloeberghs et al., 2004; Sterniczuk et al., 2010; Van Dam et al., 2003). However, the present study is the first to follow activity in the same group of mice over time and has therefore identified that hyperactivity in 3xTgAD mice occurs later than other non-cognitive changes (including temperature) in these animals.

Consistent with the results presented here, AD patients often show hyperactivity and a raised core body temperature (Touitou et al., 1986; Okawa et al., 1991; Okawa et al., 1995; Satlin et al., 1995; Mishima et al., 1997; Volicer et al., 2001; Harper et al., 2001; Harper et al., 2004; Harper et al., 2005; Klegeris et al., 2007), thus, 3xTgAD mice might represent a useful model to study non-cognitive behavioural symptoms in AD. Moreover, one of the most pronounced (and earliest) changes we observe in the 3xTgAD mice is a change in the timing of body temperature rhythms. Patients with AD also often present with an alteration in the phase of daily temperature and activity rhythms (Satlin et al., 1995; Satlin et al., 1991; Harper et al., 2001; Volicer et al., 2001; Harper et al., 2004). Interestingly though, unlike the 3xTgAD rhythms which adopt earlier phasing, these tend to be phase delayed relative to those of healthy individuals. We argue that these apparent differences most likely stem from a common cause, an impaired or altered photo-entrainment of the circadian clock. Indeed, because the internal clocks of mice [including 3xTgAD (Sterniczuk et al., 2010)] run faster than 24 hours, whereas human clocks tend to run slower (Duffy and Wright, 2005), a change in sensitivity of the clock to light would naturally push the phasing of rhythms in these two species in opposite directions. Such a change in light-mediated clock resetting could occur, either due to a reduction in photic input, or in the sensitivity of the circadian system itself. One study has investigated circadian activity patterns in the 3xTgAD mice and did not find clear changes in the magnitude of phase shifts evoked by bright light pulses (Sterniczuk et al., 2010). Whereas those findings indicate that circadian photo-entrainment is not entirely absent, they do not rule out changes in the sensitivity of the circadian clock to light because that study did not employ subsaturating light pulses or investigate a full phase response curve. Moreover, in support of the notion that photo-entrainment is impaired in AD, a number of studies have demonstrated beneficial effects of bright light therapy for non-cognitive behavioral symptoms in AD patients (Ancoli-Israel et al., 2003; Fetveit and Bjorvatn, 2004; Van Someren et al., 1997; Riemersma-van der Lek et al., 2008). We suggest, then, that more detailed investigations of light-mediated clock resetting in these 3xTgAD mice might provide important insights relevant to the human disease.

Secondary to these changes in phasing, we also observed changes in the amplitude of temperature rhythms and mean daily body temperature. The consequence of a raised core body temperature in AD is unknown, but in vitro studies suggest that an elevated temperature might have a negative effect on the disease as higher temperatures increase the expression of amyloid precursor protein (APP) and the rate of Aβ oligomerisation and fibril formation (Kusumoto et al., 1998; Gursky and Aleshkov, 2000; LeVine, 2004; Ciallella et al., 1994). There are several possible mechanisms underlying the changes in temperature in AD, including an increase in locomotor activity (see Weinert and Waterhouse, 2007). Our findings rule out increased activity as a causal factor for the increased body temperature in 3xTgAD mice, because changes in their daily temperature profiles became apparent several months before locomotor hyperactivity developed.

The main pathological features of AD are the presence of Aβ plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, primarily within the cortex and hippocampus. Although the hippocampus and cortex are not classically thought to be involved in the regulation of body temperature, it is possible that pathology in these brain regions could contribute directly or indirectly to the disruption in body temperature in 3xTgAD mice. For example, it has been shown that stimulation of the hippocampus can affect the thermosensitivity of hypothalamic neurones and body temperature in rats (Hori et al., 1982b; Hori et al., 1982a; Osaka et al., 1984). However, as significant Aβ plaques and neurofibrillary tangles are not detected in the hippocampus in the present cohort of 3xTgAD mice until 10–12 months of age (see Knight et al., 2012) it is unlikely that the changes in temperature and activity observed in 3xTgAD mice before this age are dependent on pathology in these brain regions. However, it is still possible that other pathological changes in the hippocampus of 3xTgAD mice, such as the presence of soluble Aβ and synaptic dysfunction, might be responsible for the changes in temperature rhythms in these mice. The anterior hypothalamus is the key brain region that regulates body temperature. Pathological changes, including a limited amount of Aβ plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, have been observed in the hypothalamus of AD patients (Ishii, 1966; Saper and German, 1987; Goudsmit et al., 1990; Standaert et al., 1991; Swaab et al., 1992; Zhou et al., 1995; Stopa et al., 1999; Liu et al., 2000). However, no overt pathology, including Aβ plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, was noted in the hypothalamus of 3xTgAD mice at all ages tested in the present study, including the period when activity and temperature were altered, although it is likely that changes might be seen in older mice. Increases in core body temperature are therefore unlikely to be due to overt AD-related pathology in the hypothalamus. It is possible that more subtle changes including synaptic changes, neuronal loss and soluble Aβ might be present within key nuclei of the hypothalamus, as a reduction in cells containing the neuropeptides vasopressin and VIP are observed in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus of 3xTgAD mice (Sterniczuk et al., 2010). The suprachiasmatic nucleus is the primary circadian clock involved in the regulation of circadian rhythms and thus is likely to be at least partially responsible for the changes in activity and temperature in 3xTgAD mice.

Indeed, body temperature is regulated by the circadian clock in both humans and rodents and is highest during the active phase, which corresponds with the dark phase for mice when the majority of food is consumed. The maintenance of a higher body temperature during the active dark phase in rodents is partially due to diet-induced thermogenesis, and mice that are fasted or food restricted are unable to maintain their core body temperature (Zhang et al., 2012; Rikke and Johnson, 2007). As data presented here and previously (Knight et al., 2012) demonstrate that 3xTgAD mice are hyperphagic, increased food consumption might contribute to the raised core body temperature. However, our data do not fully support that view. Firstly, we observed increased food intake in 4-month-old 3xTgAD mice, before significant increases in mean body temperature or amplitude were detected. Secondly, the amplitude of body temperature rhythms remained markedly higher in 3xTgAD mice that were pair-fed to control animals. Whereas these data argue against hyperphagia as the cause of the increased amplitude of 3xTgAD temperature rhythms, mean daily temperature in these animals was normalised to control values upon pair feeding. Overall, therefore, whereas increased food intake might contribute to the altered core body temperature in 3xTgAD mice, understanding the origin of exaggerated daily variations in body temperature will require further study.

Another pathological feature of AD that could underlie changes in body temperature is neuroinflammation, including microglia and astroctye activation, and increases in cytokine production in the brain (Heneka et al., 2010; Johnston et al., 2011). Cytokines are endogenous pyrogens that can increase core body temperature via COX-mediated release of PGs. As the expression of pyrogenic cytokines, COX and PGs in the brain are elevated in AD (Montine et al., 1999; Zagol-Ikapitte et al., 2005; Kitamura et al., 1999), we tested the hypothesis that PGs mediate the rise in core body temperature observed in 3xTgAD mice. Our data show that the changes in temperature in the 3xTgAD mouse are independent of inflammatory-driven PGs, because inhibition of COX using ibuprofen in the diet had no effect on the increase in core body temperature observed in 3xTgAD mice up to 12 weeks of treatment. By contrast, the same dose of ibuprofen prevented LPS-mediated increases in core body temperature in C57BL/6 mice, confirming its efficacy. Furthermore, as reported previously (McKee et al., 2008), the behavioural deficit (assessed in the Y-maze) in 3xTgAD mice was significantly reduced after 12 weeks treatment of ibuprofen.

In summary, these data show that there are age-related changes in core body temperature and activity rhythms in 3xTgAD mice that precede significant AD pathology. Alterations in temperature and activity might therefore be predictive of future AD. Furthermore, as these physiological/behavioural changes in 3xTgAD mice appear to analagous to those observed in the clinical situation, the 3xTgAD mouse might be a useful model for studying the mechanisms underlying non-cognitive behavioural changes and assessing potential therapies.

METHODS

Animals

Male 3xTgAD and background strain, wild-type non-transgenic (Non-Tg) (C57BL6/129sv) mice, were originally supplied by Frank LaFerla and Salvadore Oddo (University of California-Irvine, CA) and in-house colonies were established. Male mice were housed in standard housing conditions (temperature 20±2°C, humidity 55±5%, 12-hour light-dark cycle with lights on at 07:00 hours), and given ad-libitum access to standard rodent chow and water unless stated otherwise. The time of lights off was designated as Zeitgeber time (ZT) 12. All experimental procedures using animals were conducted in accordance with the United Kingdom Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986 and approved by the Home Office and the local Animal Ethical Review Group, University of Manchester.

Measurement of core body temperature and activity

For measurements of core body temperature and activity, radiotransmitters (TA10TA-F20; Data Sciences, Minneapolis, MN) were implanted abdominally into the peritoneum of mice under isoflurane anaesthesia. After surgery, mice were allowed to recover for at least 7 days before they were housed individually for continuous monitoring of core body temperature and activity by remote radiotelemetry (Data Quest III system, Data Sciences).

Core body temperature, activity and food intake in 4- and 6-month-old mice

In separate groups of mice, core body temperature and activity were measured continuously for 1 week at 4 (Non-Tg n=4; 3xTgAD n=6) and 6 (Non-Tg n=6; 3xTgAD n=6) months of age. Food intake was measured daily at lights on (07:00 hours, ZT 0) and prior to lights off (19:00 hours, ZT 12) to monitor circadian feeding patterns and the average 12-hour light phase and 12-hour dark phase values calculated.

Core body temperature, activity and food intake in 8- to 10-month-old mice

Core body temperature and activity were measured continuously for 1 week in the same group of Non-Tg (n=9) and 3xTgAD (n=15) mice at 8, 9 and 10 months of age. Food intake was measured weekly at the beginning of the light phase and the daily average calculated. After measurements at 10 months of age, 3xTgAD mice were pair-fed to Non-Tg mice for 5 days. Briefly, food weight was monitored daily in Non-Tg mice and the average 24-hour food intake calculated. Each day for 5 days at lights out (19:00 hours, ZT 12), 3xTgAD mice were given the same amount of food as the Non-Tg mice had consumed in the previous 24 hours and core body temperature and activity were recorded.

Effect of ibuprofen on core body temperature in 3xTgAD mice

At 10.5 months of age, Non-Tg and 3xTgAD mice (from the experiment above) were randomly assigned on either a control laboratory rodent diet (5001 LabDiet; IPS, London, UK) or ibuprofen-containing diet (375 ppm, modified LabDiet 5001; IPS, London, UK). Based on the average food consumption and body weight at 10 months of age, the dose of ibuprofen was calculated to be 37.5 or 41 mg/kg/day for Non-Tg and 3xTgAD, respectively. All mice (n=4–8/group) were maintained on their respective diet for 12 weeks. Core body temperature was recorded continuously during this time and data were analysed at weeks 1, 4, 8 and 12. Behaviour was then assessed after 13 weeks of treatment (see below).

In order to test the efficacy of the dose of ibuprofen used, C57BL/6 mice (n=4–5/group) were maintained on either a control or ibuprofen (375 ppm) diet for 2 days. Mice were then injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with either vehicle (5 ml/kg saline) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 100 μg/kg; 0127:B8 from Eschericha coli; Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, UK) 2 hours after lights on. After injections, animals were given a pre-weighed amount of their respective diets. Core body temperature was measured continuously for 8 hours and food intake recorded at 24 hours.

Effect of ibuprofen on behaviour in 3xTgAD mice

After 13 weeks on either ibuprofen or control diet, the Y-maze spontaneous alternation task (Hughes, 2004) was performed between 10:00 and 14:00 hours (ZT 3–7), a time during which no differences in locomotor activity was noted between Non-Tg and 3xTgAD mice. Mice were habituated to the testing room for at least 30 minutes. Following habituation, mice were placed in the starting arm and allowed to explore the maze for 8 minutes. During this period, the arm entries made by each animal were recorded visually. A mouse was said to have made an entry when all four paws had entered an arm. Spontaneous alternation was defined as successive entry into three different arms, on overlapping triplet sets. The percentage alternation was then calculated as the number of actual alternations divided by the maximum number of alternations (the total number of arm entries minus two).

Immunohistochemistry for hypothalamic AD pathology

3xTgAD and Non-Tg mice at 12 months of age (n=5–6) were anaesthetised using isoflurane (1.5–2.5% in O2) and intracardially perfused with 0.9% saline. The brain was removed and immersion fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB) (Sigma-Aldrich), before cryoprotection in 30% sucrose (Fisher Scientific) in 0.1 M PB at 4°C for 24 hours. Coronal 30-μm brain sections were then cut throughout the level of the hypothalamus on a freezing sliding microtome (from 0.50 to −2.46 mm relative to bregma according to the atlas of Paxinos and Franklin (Paxinos and Franklin, 2001). As a positive control for Aβ and tau, sections were also taken to include the hippocampus (from −1.06 to −3.64 mm relative to bregma). Immunohistochemistry for either Aβ or phosphorylated tau was then performed on free-floating sections. Briefly, endogenous peroxidase was removed by incubation in 1.5% H2O2 (in 20% methanol, PB, 0.3% Triton X-100) before treatment in blocking solution (10% normal horse serum in PB, 0.3% Triton X-100). Sections were then incubated at 4°C overnight with either a monoclonal mouse anti-human amyloid 6E10 (1:3000; Covance-Signet Laboratories, Cambridge, UK) for Aβ, or monoclonal mouse anti-human PHF-tau (AT8, 1:1000; Autogen Bioclear, Calne, UK) for hyperphosphorylated tau. After washes in PB containing 0.3% Triton X-100, sections were treated for 2 hours in a biotinylated horse anti-mouse IgG antibody (1:500; Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, UK). Following washes in 0.1 M PB, sections were immersed in avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC; Vector Laboratories) for 30 minutes, rinsed in 0.1 M PB and colour-developed using 0.05% diaminobenzidine solution in 0.01% H2O2. Sections were mounted onto gelatine-coated slides and dried; coverslips were applied before viewing under a light microscope. Immunohistochemistry for Aβ and phosphorylated tau in the hypothalamus and hippocampus was also performed on brain sections from a separate set of mice between the ages of 4 and 10 months.

Data analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± s.d., unless otherwise stated. To estimate the phase and amplitude of diurnal variations in temperature (°C) and activity (counts per minute; CPM), the raw data was smoothed (monitored over 5–7 day epochs) using a boxcar filter (width of 1 hour). Mean daily profiles for each animal (as a function of ZT) were calculated. The amplitude of the diurnal rhythm in each individual was calculated as the difference between the highest and lowest values of these 24-hour averages. Phase was estimated for each animal as the ZT when the value of these 24-hour averages first became higher than the overall daily mean (temperature) or median (activity). These phase markers were chosen to provide the most reliable estimators of phase, but estimates based on daily peaks (or nadirs) gave similar results (not shown). Phase and amplitude was also estimated directly from raw records by fitting sinusoids (constrained to a period of 24 hours; Prism 4, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Phase and amplitude values derived from these fits were also essentially identical to those estimated above (not shown).

Statistical comparisons for 4- and 6-month-old mice were performed using a Student’s t-test. Data for 8- to 10-month-old mice were analysed using a two-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple comparisons test; data was recorded over time in the same group of mice. For the effect of ibuprofen on body temperature and behaviour in Non-Tg and 3xTgAD mice, a two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc analysis was employed. For the effect of ibuprofen on body temperature in C57BL/6 mice, the integrated temperature response (between 0 and 8 hours), stated as area under the curve (AUC, °C.hour), was calculated for each animal by the trapezoidal method. Average AUC values were then determined for each group. Differences were considered significant at the P<0.05 level.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Biological Services Facility at the University of Manchester for expert animal husbandry.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that they do not have any competing or financial interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.B.L. and S.M.A. conceived and designed the experiments. C.B.L., J.C.M.S., E.J.W. and S.G. performed the in vivo experiments and ex vivo analyses. C.B.L. and T.M.B. analysed the data and wrote the paper.

FUNDING

J.C.M.S. and E.J.W. were Masters of Research students funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC). E.M.K. was a Medical Research Council (MRC)-funded PhD student.

REFERENCES

- Ambrée O., Touma C., Görtz N., Keyvani K., Paulus W., Palme R., Sachser N. (2006). Activity changes and marked stereotypic behavior precede Abeta pathology in TgCRND8 Alzheimer mice. Neurobiol. Aging 27, 955–964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ancoli-Israel S., Gehrman P., Martin J. L., Shochat T., Marler M., Corey-Bloom J., Levi L. (2003). Increased light exposure consolidates sleep and strengthens circadian rhythms in severe Alzheimer’s disease patients. Behav. Sleep Med. 1, 22–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assal F., Cummings J. L. (2002). Neuropsychiatric symptoms in the dementias. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 15, 445–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard C., Gauthier S., Corbett A., Brayne C., Aarsland D., Jones E. (2011). Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 377, 1019–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedrosian T. A., Herring K. L., Weil Z. M., Nelson R. J. (2011). Altered temporal patterns of anxiety in aged and amyloid precursor protein (APP) transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 11686–11691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bombois S., Derambure P., Pasquier F., Monaca C. (2010). Sleep disorders in aging and dementia. J. Nutr. Health Aging 14, 212–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braidy N., Muñoz P., Palacios A. G., Castellano-Gonzalez G., Inestrosa N. C., Chung R. S., Sachdev P., Guillemin G. J. (2012). Recent rodent models for Alzheimer’s disease: clinical implications and basic research. J. Neural. Transm. 119, 173–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciallella J. R., Rangnekar V. V., McGillis J. P. (1994). Heat shock alters Alzheimer’s beta amyloid precursor protein expression in human endothelial cells. J. Neurosci. Res. 37, 769–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy J. F., Wright K. P., Jr (2005). Entrainment of the human circadian system by light. J. Biol. Rhythms 20, 326–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetveit A., Bjorvatn B. (2004). The effects of bright-light therapy on actigraphical measured sleep last for several weeks post-treatment. A study in a nursing home population. J. Sleep Res. 13, 153–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel S. I. (2003). Behavioral and psychologic symptoms of dementia. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 19, 799–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank-Cannon T. C., Alto L. T., McAlpine F. E., Tansey M. G. (2009). Does neuroinflammation fan the flame in neurodegenerative diseases? Mol. Neurodegener. 4, 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillette-Guyonnet S., Abellan Van Kan G., Alix E., Andrieu S., Belmin J., Berrut G., Bonnefoy M., Brocker P., Constans T., Ferry M., et al. (2007). IANA (International Academy on Nutrition and Aging) Expert Group: weight loss and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Nutr. Health Aging 11, 38–48 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudsmit E., Hofman M. A., Fliers E., Swaab D. F. (1990). The supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei of the human hypothalamus in relation to sex, age and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 11, 529–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gursky O., Aleshkov S. (2000). Temperature-dependent beta-sheet formation in beta-amyloid Abeta(1–40) peptide in water: uncoupling beta-structure folding from aggregation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1476, 93–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall A. M., Roberson E. D. (2012). Mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. Bull. 88, 3–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper D. G., Stopa E. G., McKee A. C., Satlin A., Harlan P. C., Goldstein R., Volicer L. (2001). Differential circadian rhythm disturbances in men with Alzheimer disease and frontotemporal degeneration. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 58, 353–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper D. G., Stopa E. G., McKee A. C., Satlin A., Fish D., Volicer L. (2004). Dementia severity and Lewy bodies affect circadian rhythms in Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol. Aging 25, 771–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper D. G., Volicer L., Stopa E. G., McKee A. C., Nitta M., Satlin A. (2005). Disturbance of endogenous circadian rhythm in aging and Alzheimer disease. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 13, 359–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneka M. T., O’Banion M. K., Terwel D., Kummer M. P. (2010). Neuroinflammatory processes in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neural Transm. 117, 919–947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori T., Kiyohara T., Osaka T., Shibata M., Nakashima T. (1982a). Responses of preoptic thermosensitive neurons to mediobasal hypothalamic stimulation. Brain Res. Bull. 8, 677–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori T., Osaka T., Kiyohara T., Shibata M., Nakashima T. (1982b). Hippocampal input to preoptic thermosensitive neurons in the rat. Neurosci. Lett. 32, 155–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes R. N. (2004). The value of spontaneous alternation behavior (SAB) as a test of retention in pharmacological investigations of memory. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 28, 497–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huitrón-Reséndiz S., Sánchez-Alavez M., Gallegos R., Berg G., Crawford E., Giacchino J. L., Games D., Henriksen S. J., Criado J. R. (2002). Age-independent and age-related deficits in visuospatial learning, sleep-wake states, thermoregulation and motor activity in PDAPP mice. Brain Res. 928, 126–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii T. (1966). Distribution of Alzheimer’s neurofibrillary changes in the brain stem and hypothalamus of senile dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 6, 181–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston H., Boutin H., Allan S. M. (2011). Assessing the contribution of inflammation in models of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 39, 886–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura Y., Shimohama S., Koike H., Kakimura J., Matsuoka Y., Nomura Y., Gebicke-Haerter P. J., Taniguchi T. (1999). Increased expression of cyclooxygenases and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma in Alzheimer’s disease brains. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 254, 582–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaffke S., Staedt J. (2006). Sundowning and circadian rhythm disorders in dementia. Acta Neurol. Belg. 106, 168–175 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klegeris A., Schulzer M., Harper D. G., McGeer P. L. (2007). Increase in core body temperature of Alzheimer’s disease patients as a possible indicator of chronic neuroinflammation: a meta-analysis. Gerontology 53, 7–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight E. M., Verkhratsky A., Luckman S. M., Allan S. M., Lawrence C. B. (2012). Hypermetabolism in a triple-transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 33, 187–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusumoto Y., Lomakin A., Teplow D. B., Benedek G. B. (1998). Temperature dependence of amyloid beta-protein fibrillization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 12277–12282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeVine H., 3rd (2004). Alzheimer’s beta-peptide oligomer formation at physiologic concentrations. Anal. Biochem. 335, 81–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R. Y., Zhou J. N., Hoogendijk W. J., van Heerikhuize J., Kamphorst W., Unmehopa U. A., Hofman M. A., Swaab D. F. (2000). Decreased vasopressin gene expression in the biological clock of Alzheimer disease patients with and without depression. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 59, 314–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee A. C., Carreras I., Hossain L., Ryu H., Klein W. L., Oddo S., LaFerla F. M., Jenkins B. G., Kowall N. W., Dedeoglu A. (2008). Ibuprofen reduces Abeta, hyperphosphorylated tau and memory deficits in Alzheimer mice. Brain Res. 1207, 225–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishima K., Okawa M., Satoh K., Shimizu T., Hozumi S., Hishikawa Y. (1997). Different manifestations of circadian rhythms in senile dementia of Alzheimer’s type and multi-infarct dementia. Neurobiol. Aging 18, 105–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montine T. J., Sidell K. R., Crews B. C., Markesbery W. R., Marnett L. J., Roberts L. J., 2nd, Morrow J. D. (1999). Elevated CSF prostaglandin E2 levels in patients with probable AD. Neurology 53, 1495–1498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddo S., Caccamo A., Shepherd J. D., Murphy M. P., Golde T. E., Kayed R., Metherate R., Mattson M. P., Akbari Y., LaFerla F. M. (2003). Triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease with plaques and tangles: intracellular Abeta and synaptic dysfunction. Neuron 39, 409–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okawa M., Mishima K., Hishikawa Y., Hozumi S., Hori H., Takahashi K. (1991). Circadian rhythm disorders in sleep-waking and body temperature in elderly patients with dementia and their treatment. Sleep 14, 478–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okawa M., Mishima K., Hishikawa Y., Hozumi S. (1995). [Rest-activity and body-temperature rhythm disorders in elderly patients with dementia – senile dementia of Alzheimer’s type and multi-infarct dementia]. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 35, 18–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osaka T., Hori T., Kiyohara T., Shibata M., Nakashima T. (1984). Changes in body temperature and thermosensitivity of preoptic and septal neurons during hippocampal stimulation. Brain Res. Bull. 13, 93–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G., Franklin K. B. J. (2001). The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. New York, NY: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- Richter H., Ambrée O., Lewejohann L., Herring A., Keyvani K., Paulus W., Palme R., Touma C., Schäbitz W. R., Sachser N. (2008). Wheel-running in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease: protection or symptom? Behav. Brain Res. 190, 74–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemersma-van der Lek R. F., Swaab D. F., Twisk J., Hol E. M., Hoogendijk W. J., Van Someren E. J. (2008). Effect of bright light and melatonin on cognitive and noncognitive function in elderly residents of group care facilities: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 299, 2642–2655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rikke B. A., Johnson T. E. (2007). Physiological genetics of dietary restriction: uncoupling the body temperature and body weight responses. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 293, R1522–R1527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saper C. B., German D. C. (1987). Hypothalamic pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 74, 364–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satlin A., Teicher M. H., Lieberman H. R., Baldessarini R. J., Volicer L., Rheaume Y. (1991). Circadian locomotor activity rhythms in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychopharmacology 5, 115–126 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satlin A., Volicer L., Stopa E. G., Harper D. (1995). Circadian locomotor activity and core-body temperature rhythms in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 16, 765–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standaert D. G., Lee V. M., Greenberg B. D., Lowery D. E., Trojanowski J. Q. (1991). Molecular features of hypothalamic plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Pathol. 139, 681–691 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterniczuk R., Dyck R. H., Laferla F. M., Antle M. C. (2010). Characterization of the 3xTg-AD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease: part 1. Circadian changes. Brain Res. 1348, 139–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stopa E. G., Volicer L., Kuo-Leblanc V., Harper D., Lathi D., Tate B., Satlin A. (1999). Pathologic evaluation of the human suprachiasmatic nucleus in severe dementia. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 58, 29–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoppe G., Brandt C. A., Staedt J. H. (1999). Behavioural problems associated with dementia: the role of newer antipsychotics. Drugs Aging 14, 41–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaab D. F., Grundke-Iqbal I., Iqbal K., Kremer H. P., Ravid R., van de Nes J. A. (1992). Tau and ubiquitin in the human hypothalamus in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 590, 239–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touitou Y., Reinberg A., Bogdan A., Auzéby A., Beck H., Touitou C. (1986). Age-related changes in both circadian and seasonal rhythms of rectal temperature with special reference to senile dementia of Alzheimer type. Gerontology 32, 110–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dam D., D’Hooge R., Staufenbiel M., Van Ginneken C., Van Meir F., De Deyn P. P. (2003). Age-dependent cognitive decline in the APP23 model precedes amyloid deposition. Eur. J. Neurosci. 17, 388–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Someren E. J., Kessler A., Mirmiran M., Swaab D. F. (1997). Indirect bright light improves circadian rest-activity rhythm disturbances in demented patients. Biol. Psychiatry 41, 955–963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vloeberghs E., Van Dam D., Engelborghs S., Nagels G., Staufenbiel M., De Deyn P. P. (2004). Altered circadian locomotor activity in APP23 mice: a model for BPSD disturbances. Eur. J. Neurosci. 20, 2757–2766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volicer L., Harper D. G., Manning B. C., Goldstein R., Satlin A. (2001). Sundowning and circadian rhythms in Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Psychiatry 158, 704–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinert D., Waterhouse J. (2007). The circadian rhythm of core temperature: effects of physical activity and aging. Physiol. Behav. 90, 246–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White H., Pieper C., Schmader K. (1998). The association of weight change in Alzheimer’s disease with severity of disease and mortality: a longitudinal analysis. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 46, 1223–1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White H. K., McConnell E. S., Bales C. W., Kuchibhatla M. (2004). A 6-month observational study of the relationship between weight loss and behavioral symptoms in institutionalized Alzheimer’s disease subjects. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 5, 89–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagol-Ikapitte I., Masterson T. S., Amarnath V., Montine T. J., Andreasson K. I., Boutaud O., Oates J. A. (2005). Prostaglandin H(2)-derived adducts of proteins correlate with Alzheimer’s disease severity. J. Neurochem. 94, 1140–1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. N., Mitchell S. E., Hambly C., Morgan D. G., Clapham J. C., Speakman J. R. (2012). Physiological and behavioral responses to intermittent starvation in C57BL/6J mice. Physiol. Behav. 105, 376–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J. N., Hofman M. A., Swaab D. F. (1995). VIP neurons in the human SCN in relation to sex, age, and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 16, 571–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]