Abstract

Thyroid hormone serves many functions throughout brain development, but the mechanisms that control the timing of its actions in specific brain regions are poorly understood. In the cerebellum, thyroid hormone controls formation of the transient external germinal layer, which contains proliferative granule cell precursors, subsequent granule cell migration, and cerebellar foliation. We report that the thyroid hormone-inactivating type 3 deiodinase (encoded by Dio3) is expressed in the mouse cerebellum at embryonic and neonatal stages, suggesting a need to protect cerebellar tissues from premature stimulation by thyroid hormone. Dio3−/− mice displayed reduced foliation, accelerated disappearance of the external germinal layer, and premature expansion of the molecular layer at juvenile ages. Furthermore, Dio3−/− mice exhibited locomotor behavioral abnormalities and impaired ability in descending a vertical pole. To ascertain that these phenotypes resulted from inappropriate exposure to thyroid hormone, thyroid hormone receptor α1 (TRα1) was removed from Dio3−/− mice, which substantially corrected the cerebellar and behavioral phenotypes. Deletion of TRα1 did not correct the previously reported small thyroid gland or deafness in Dio3−/− mice, indicating that Dio3 controls the activation of specific receptor isoforms in different tissues. These findings suggest that type 3 deiodinase constrains the timing of thyroid hormone action during cerebellar development.

Brain development requires thyroid hormone. Developmental hypothyroidism can result in irreversible mental retardation and neurological deficits in humans and rodents (1, 2). Thyroid hormone actions are mediated by binding of the active form of hormone, T3, to thyroid hormone receptor α1 (TRα1) and TRβ nuclear receptors, encoded by Thra and Thrb genes, respectively (3–8). Preceding receptor activation, T3 concentrations within immature tissues can be regulated to some extent independently of systemic hormone levels by the activating deiodinase type 2 (D2) and inactivating D3 (9). The majority of nuclear T3 in the brain is locally derived from T4, the major form of thyroid hormone in the circulation, by D2 enzyme (10, 11). In contrast, D3 depletes both T4 and T3 by conversion into the minimally active metabolites rT3 and diiodothyronine, respectively (9, 12–14). In Dio3−/− mice, brain tissues display changed mRNA levels of T3-responsive genes and an increased responsiveness to exogenous T3 (15), suggesting a protective role for D3 in the immature brain. However, known neurodevelopmental phenotypes in Dio3-deficient mice mainly concern auditory and visual rather than central brain functions (16–18).

The cerebellum mediates locomotor control and motor learning. In rodents, the cerebellum appears during later gestation and then expands postnatally to acquire its laminated and folded, or foliated, form. Thyroid hormone controls migration of cerebellar granule cells, arborization of Purkinje cells, and foliation (7, 19–22). TRα1 mRNA is expressed in the early cerebellar neuroepithelium, Purkinje cell layer, and subsequently in the transient external germinal layer (EGL), whereas TRβ mRNA appears later, at low levels, in the Purkinje cell layer and deep internal layers (23, 24). TRβ and TRα1 deletions have relatively little impact on cerebellar morphology. However, the retardation of cerebellar development caused by hypothyroidism is thought to result from chronic transcriptional dysregulation caused by unoccupied TRα1 (5). Also, a dominant-negative TRα1 alters cerebellar neuronal and glial differentiation in mice (25), indicating a role for TRα1 in cerebellar development.

Given the paucity of known functions for deiodinases in the brain, we investigated a role for D3 in the cerebellum. D3 activity was previously identified in cerebellar extracts of the rat neonate and human fetus (26–28), implying a need to limit exposure to T3 at immature stages. We report that Dio3−/− mice display impaired cerebellar foliation, premature disappearance of the EGL, accelerated expansion of the molecular layer, which contains the Purkinje cell dendritic tree, and defective locomotor behavior. Furthermore, deletion of TRα1 partly corrected cerebellar morphology and behavior but did not correct the previously reported deafness or thyroid gland abnormality in Dio3−/− mice, indicating that D3 controls the activation of specific receptor isoforms in different tissues. These data indicate a role for D3 in cerebellar development and suggest the importance of restricting T3 availability at sensitive stages of brain development.

Materials and Methods

Mouse strains

Activities and expression of D2 and D3 were analyzed in the cerebellum in wild-type (+/+) C57BL/6J mice obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). The Dio3-knockout mutation (29), originally on a 129/SvJ × C57BL/6 mixed background, was backcrossed for two generations onto the C57BL/6 strain. The Thra1 deletion (30) was on a mixed background of BALB/c × C57BL/6 strains. Genotyping was performed by PCR as described (29, 30). Dio3+/− and Thra1+/− mice were crossed to generate combined Dio3+/−;Thra1+/− mice, which were intercrossed to generate +/+ and single and double homozygous genotypes on the same mixed background for analysis. To avoid complications of maternal hormonal influence, progeny for analysis were not obtained from homozygous Dio3−/− dams. Studies were conducted under approved protocols at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease (National Institutes of Health) and Dartmouth Medical School.

Histology

For histology, cerebella and thyroid glands were fixed for 3 and 7 d, respectively, in PBS containing 3% glutaraldehyde/2% paraformaldehyde at 4 C, dehydrated through 30, 50, 70, and 100% ethanol and then embedded in glycol methacrylate (Polysciences, Warrington, PA) for preparation of 6-μm-thick plastic sections. Midsagittal sections of cerebellum were stained with aqueous hematoxylin. Horizontal, midregion sections of thyroid were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Biomeda Corp., Foster City, CA). Groups consisted of three to five cerebella per age per genotype and more than three thyroid glands of adult mice per genotype. Area measurements were made on sections using the ImageJ version 1.44 program (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). EGL thickness was measured at a representative region at the bottom of one of the deepest sulci (between foliae 3 and 4). Five measurements were performed on each of three consecutive sections for three to four cerebella per genotype per age. Cerebellum size was determined in three consecutive midsagittal sections for at least four mice per genotype. Internal granular layer (IGL) area was determined in foliae 6 and 7, a representative area with clearly different foliation. IGL area was determined as a percentage of the total volume of these foliae on two consecutive sections for four mice per genotype. Thyroid area was measured on three consecutive midthyroidal sections for at least three mice per genotype.

Immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization

For immunohistochemistry, cerebella were fixed for 4 h in 2% paraformaldehyde. Twelve-micrometer-thick cryosections were blocked with PBS containing 1.5% goat serum, 0.1% BSA, and 0.4% Triton X-100; incubated with primary antibodies overnight at room temperature; and then incubated with biotinylated goat antirabbit or goat antimouse antibodies. Detection was performed with a Vector ABC Elite kit with diaminobenzidine (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Rabbit anti-calbindin D-28K antibody (Millipore, Billerica, MA; AB1778) was used at 1:500 and mouse anti-neuronal nuclei antibody (Millipore; MAB377) at 1:500 dilution. Fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat antirabbit or goat antimouse were used as secondary antibodies (Vector Laboratories). Calbindin-positive Purkinje cells were counted at a location between foliae 3 and 4 on three consecutive sections in two representative fields per section. The thickness of the Purkinje cell layer was determined using the ImageJ version 1.44 program (National Institutes of Health). Five measurements were performed on each of three consecutive sections, for more than three mice per genotype.

For in situ hybridization, cerebella were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4 C. Twelve-micrometer-thick cryosections were hybridized with digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes generated from mouse cDNA sequences for Dio3 (bases 78–526, accession no. BC106847) and Thra (bases 61–1925, accession no. NM 178060). The same cDNAs were used to generate sense control probes.

Deiodination assays and RIAs

Activities of D3 and D2 were determined as described (16, 31) using three to four individual cerebella from +/+ mice for each developmental age. For comparison of +/+, Dio3+/−, and Dio3−/− embryos, three to five individual cerebella were analyzed. Briefly, D2 was measured using [125I]T4 as a substrate, with or without 1 mm 6n-propyl-2-thiouracil, an inhibitor of type 1 deiodinase. D3 activity was determined with [125I]T3 as a substrate. Substrates were obtained from PerkinElmer Inc. (Norwalk, CT). Serum total T4 and total T3 levels were determined by RIA with Coat-A-Count reagents (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Inc., Webster, TX) for groups of more than 10 mice per genotype for each age except at postnatal d 5 (P5), for which two to three samples from different mice were combined into at least three pools. T4 and T3 values are shown as means ± sem.

Behavioral tests for motor coordination and function

For the vertical pole test for agility, mice were placed face upward near the top of a 40-cm-tall plastic pole. A normal mouse will then invert itself, wrap its tail round the pole, and then climb down to the base (11). The time to invert and the time to descend were measured over a maximum period of 60 sec. Experiments were repeated three times on a single day and performed on three different days (d 1, 3, and 5). For the rotarod test of balance and agility, mice were placed on an accelerating rotarod apparatus (Ugo Basile, model 7650; Varese, Italy) (11). The speed was increased by 4 rpm every 30 sec until the mouse fell off or when the mouse switched to passive rotation, which was defined as more than five rotations without an attempt to walk. Three attempts were performed per day. There was a 2-min break between each session. To assess learning ability, tests were repeated on 3 consecutive days.

Auditory function analysis

Auditory evoked brainstem responses (ABRs) were measured with a SmartEP system (Intelligent Hearing Systems, Miami, FL) in 2- to 3-month-old mice under Avertin anesthesia (0.25 mg/g body weight, ip), as described (16).

Statistical analysis

Statistical tests were performed in GraphPad Prism version 5.0d (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). Data are presented as the mean ± sem. Differences between +/+ and Dio3−/− mice were analyzed using a Student's t test or Wilcoxon rank sum test where appropriate. When several different genotypes were compared, a one-way ANOVA test was used. In the case of significance, we studied whether Dio3−/− mice and Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− mice were significantly different from the +/+ controls with a Student's t test or Mann-Whitney U test where appropriate. We also analyzed whether Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− mice were significantly different from Dio3−/− mice, resulting in three post hoc tests. As a consequence, a Bonferroni correction for multiple testing would require a P value < 0.017 for significance.

Results

D3 and D2 expression in mouse cerebellar development

Activity of the activating D2 enzyme was barely detectable in cerebellar homogenates at embryonic d 18 (E18) or at birth (P0) but increased between P3 and P9 (Fig. 1A). In contrast, the inactivating D3 enzyme showed an opposite trend, consistent with previous data on rat cerebellum (27). D3 activity was detected in cerebellar homogenates from late-stage mouse embryos and neonates, but levels progressively decreased between P3 and P12 (Fig. 1A). Although D3 activity was present in the cerebellum, the level was notably low in comparison with tissues such as the retina at E18.5 (17) (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Developmental expression of D3 and D2 in cerebellum. A, D3 activity peaked in mouse cerebellar homogenates at embryonic and early neonatal stages, whereas D2 activity peaked postnatally. B, D3 activity was undetectable in cerebellar or control eye samples from Dio3−/− mice and was reduced by approximately 50% in both tissues in Dio3+/− mice compared with +/+ mice at E18.5. C, In situ hybridization detected Dio3 mRNA in midcentral regions of the early cerebellar outgrowth (mc), Purkinje cell layer (PCL), and EGL (arrowhead) at E18. At P3, Dio3 mRNA signals decreased but were weakly detectable in the PCL and EGL (arrowhead). At P3, Thra mRNA signals strengthened in the inner region of the PCL. Scale bar, 0.1 mm.

To confirm that cerebellar D3 activity resulted from the enzyme encoded by the Dio3 gene, we investigated Dio3−/− mice at E18.5 (Fig. 1B). D3 activity was undetectable in cerebellar or control eye samples (17) from Dio3−/− mice and was reduced by approximately 50% in both tissues from Dio3+/− heterozygous mice compared with +/+ mice.

To corroborate the detection of D3 activity in the cerebellum, Dio3 mRNA was analyzed by in situ hybridization with digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes in +/+ mice at E18.5 and postnatal stages, spanning the peak period for D3 activity (Fig. 1C). Dio3 mRNA levels were low in accord with the observed level of D3 activity. Dio3 mRNA was detectable within the early cerebellar outgrowth and in the EGL (arrowhead). A control Dio3 sense probe gave very little background signal. By P3, Dio3 signal had declined to almost undetectable levels, but weak signal persisted in the formative Purkinje cell layer and the EGL. A Thra probe encompassing the common region of TRα1 and the non-T3-binding TRα2 variant detected Thra signal in the early cerebellar outgrowth and Purkinje cell layer at E18 and P3. Thra mRNA was not detected in the early EGL at E18 or P3 but was detected at later stages in the EGL by P12, consistent with data for the rat (23). Dio3 mRNA remained below detection in any cerebellar region at these older postnatal ages.

Abnormal cerebellar morphology in Dio3−/− mice

Histological examination revealed impaired cerebellar foliation in adult Dio3−/− mice (Fig. 2). The rudiments of all foliae (I to X) were present, but the foliae were smaller and less elaborately formed than in +/+ mice.

Fig. 2.

Hematoxylin staining of midsagittal sections of cerebellum, revealing impaired foliation in adult Dio3−/− mice. All foliae (numbered I–X) were present in rudimentary form in Dio3−/− mice but were less elaborately expanded or folded than in +/+ mice. Scale bar, 1 mm.

At late embryonic stages in mice, cerebellar granule cell precursors begin to form the proliferative EGL, which expands postnatally with a peak of proliferation around P8 (32). During the first two postnatal weeks, these precursors differentiate into granule cells, which migrate inward through the nascent molecular layer to form the IGL (33, 34). In +/+ mice, the EGL was prominent at P10 but diminished in size by P14 (Fig. 3, C and D). However, in Dio3−/− mice at P10, the EGL was prematurely thinner than in +/+ mice (by ∼50%) and at P14 had almost completely disappeared (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 3.

Hematoxylin staining of midsagittal sections of cerebellum showing abnormally accelerated development in Dio3−/−, mice and substantial reversal of this phenotype in Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− mice. A, Adult Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− mice displaying corrected foliation compared with Dio3−/−, mice. Scale bar, 1 mm. B, At P14, Dio3−/− mice display accelerated disappearance of the EGL compared with +/+ mice; the phenotype is largely reversed in Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− mice. Scale bar, 1 mm. C, Magnified view of boxed area in B. Scale bar, 0.1 mm. ML, Molecular layer. D, At P10, the EGL was prematurely thinner in Dio3−/− mice compared with +/+ or Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− mice. Scale bar, 0.1 mm.

Fig. 4.

Abnormal cerebellar dimensions in Dio3−/− mice and partial correction in Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− mice. A, Prematurely decreased thickness of the EGL in Dio3−/− but not Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− mice at P10 and P14 (means ± sem). ***, P < 0.001 compared with +/+ mice. B, The IGL in adult Dio3−/− mice was 41% smaller than in +/+ mice (mean size ± sem). *, P < 0.05 (P = 0.025) compared with +/+ mice. C, Cerebellar size measured on representative areas of histological sections was smaller in Dio3−/− mice than +/+ mice, but this reduction was in proportion to the 30% lower body weight of Dio3−/− mice at P10 (mean ± sem). ***, P < 0.001 compared with +/+ mice. P values shown were obtained using a t test or Mann-Whitney U test where appropriate.

Histomorphometric measurements also demonstrated that Dio3−/− mice displayed an abnormally smaller IGL. The IGL area in a given field of view of cerebellar sections in adult Dio3−/− mice was 41% smaller than in +/+ mice (Fig. 4B).

The molecular layer was prematurely expanded in Dio3−/− mice and at P10 was 50% wider than in +/+ mice (Fig. 5, A and B). At mature ages (3–4 months old), the molecular layer was equally wide in Dio3−/− and +/+ mice. The molecular layer is largely formed by the dendritic tree of the Purkinje cells, which form synapses with granule neuron projections. Thus, the premature expansion of the molecular layer was consistent with accelerated differentiation of Purkinje cells in Dio3−/− mice. However, numbers of Purkinje cells in a given field of view identified by calbindin staining, were similar in Dio3−/− and +/+ mice at P10 (Fig. 5, A and B).

Fig. 5.

Premature expansion of the molecular layer (ML) in Dio3−/− mice but not in Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− mice. A, Calbindin staining of midsagittal sections of cerebellum of +/+, Dio3−/−, Thra1−/−, and Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− mice at P10 and at adult ages. PCL, Purkinje cell layer. B, Molecular layer thickness at P10 and adult ages and number of Purkinje cells at P10 (mean thickness ± sem). ***, P < 0.001 compared with +/+ mice. P values shown were obtained using a Student's t test or Mann-Whitney U test where appropriate. Scale bar, 0.05 mm.

Overall, cerebellar area measured on histological sections was smaller in Dio3−/− mice than +/+ mice, but this reduction was in proportion to the 30% lower body weight of Dio3−/− mice at P10 (Fig. 4C). Thus, the changed kinetics of disappearance of the EGL, expansion of molecular layer, and less elaborate foliation but not overall cerebellar size were independent of the body mass of Dio3−/− mice.

Reversal of cerebellar phenotype in Dio3−/− mice by deletion of TRα1

To test the hypothesis that premature disappearance of the EGL and impaired foliation in Dio3−/− mice resulted from stimulation by T3, the major T3 receptor isoform in cerebellum, TRα1 (35), was deleted from Dio3−/− mice. According to the hypothesis, removal of TRα1 would make the cerebellum at least partly resistant to T3. Indeed, Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− doubly homozygous mice showed a marked improvement in cerebellar morphology compared with Dio3−/− mice at adult or juvenile (P14) ages (Fig. 3, A and B). Furthermore, Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− mice also retained an EGL at P10 and P14 that was of similar thickness as in +/+ mice (Fig. 3, C and D, and Fig. 4, A and B). The EGL of Thra1−/− mice was similar to that in +/+ mice at both P10 and P14; overall cerebellar morphology in Thra1−/− mice was not overtly different from that in +/+ mice, as reported previously (5).

Histomorphometric measurements demonstrated that in addition to EGL thickness, the IGL area (Fig. 4B) and the molecular layer width (Fig. 5B) were fully or substantially corrected in Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− mice compared with Dio3−/− mice. Purkinje cell counts in a given field of view were not affected in any of the genotypes (Fig. 5B).

Behavioral phenotype in Dio3−/− mice and reversal by deletion of TRα1

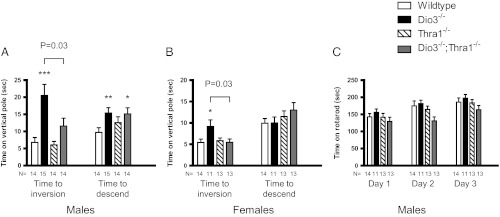

Given that cerebellar abnormalities in rodents are associated with impaired locomotor activity, we tested whether Dio3−/− mice exhibited such deficiencies using the vertical pole and rotarod tests for agility and balance. On the vertical pole, both male and female Dio3−/− mice took a longer time to invert than +/+ mice (Fig. 6A). After inversion, male Dio3−/− mice also took longer to descend (Fig. 6B). However, female Dio3−/− mice did not show a significant delay compared with +/+ mice, suggesting a gender-specific difference in responses. On the rotarod, no differences in performance were observed between +/+ and Dio3−/− mice, whether male (Fig. 6C) or female (not shown). There was also no difference in learning capacity, as demonstrated by similar improvements in performance when tested on the rotarod on three consecutive days.

Fig. 6.

Dio3−/− mice have impaired locomotor activity, which is partially reversed in Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− mice. A, Time to invert and time to descend a vertical pole in male +/+, Dio3−/−, Thra1−/−, and Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− mice (mean ± sem). *, P < 0.05 (P = 0.02); **, P = 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 compared with wild-type. B, Time to invert on and time to descend a vertical pole for female +/+, Dio3−/−, Thra1−/−, and Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− mice (mean ± sem). * P < 0.05 (P = 0.02) compared with +/+ mice. C, Performance on a rotarod was not different between +/+ and Dio3−/− mice, nor was there a difference in their learning capacity (mean ± sem). P values shown were obtained using a Student's t test or Mann-Whitney U test where appropriate.

Compared with Dio3−/− mice, Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− mice displayed improved performance on the vertical pole test, indicating that the behavioral abnormalities resulted from T3 acting on TRα1 in the absence of D3 enzyme. The time to invert was improved in Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− male mice and was fully normalized in female Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− mice (Fig 6A).

Corrected body weight but not thyroid gland function by deletion of TRα1 in Dio3−/− mice

In addition to the cerebellar and behavioral phenotypes described in this study, Dio3−/− mice were previously reported to display a small dysfunctional thyroid gland and low body weight (31, 36). To investigate whether cooperation between the Dio3 and Thra genes extended to other tissues, Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− mice were tested for serum T4 and T3 levels, thyroid gland size, and body weight.

Dio3−/− mice display very low T4 levels in the postnatal period and approximately 50% lower T4 levels as adults. Dio3−/− mice also display prematurely elevated T3 levels in the postnatal period followed by a drop after approximately P10, giving somewhat low levels of T3 in adulthood (31, 36). Serum T4 and T3 levels were similar in Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− and in Dio3−/− mice at P5 and P10 and in adults (Fig. 7A). Moreover, both genotypes also displayed small thyroid glands with fewer colloid-filled follicles than +/+ or Thra1−/− mice (Fig. 7B, D), indicating that the thyroid dysfunction in Dio3−/− mice was not primarily caused by overstimulation of TRα1. Importantly, these data indicated that correction of the cerebellar phenotype in Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− mice was not mediated via systemic normalization of circulating T4 and T3 levels.

Fig. 7.

Corrected body weight but not thyroid gland function by deletion of TRα1 in Dio3−/−mice. A, Serum T4 and T3 levels were similar in Dio3−/− and in Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− mice at P5 and P10 and in adults (mean ± sem). B, Hematoxylin and eosin staining of midregion thyroid sections demonstrating smaller thyroid glands with fewer colloid-filled follicles in Dio3−/− and Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− mice than in +/+ or Thra1−/− mice. C, Body weight in Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− mice was substantially recovered compared with Dio3−/− mice (mean ± sem). ***, P < 0.001 compared with +/+ mice. D, Decreased thyroid size in Dio3−/− mice was not proportionate to the decreased weight (mean ± sem). *, P < 0.05 (P = 0.02 for both) compared with +/+ mice. P values shown were obtained using a Student's t test or Mann-Whitney U test where appropriate. Scale bar, 0.1 mm.

Body weight in Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− mice was substantially recovered compared with Dio3−/− mice (Fig. 7C) despite the lack of rescue of systemic T4 and T3 levels. These findings suggest that the small stature of Dio3−/− mice results from overstimulation of TRα1 in specific tissues.

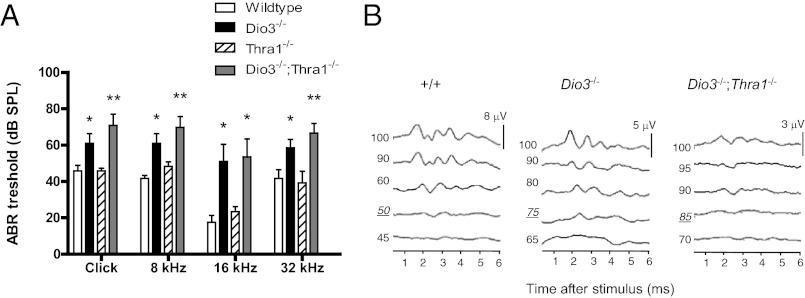

Nonreversal of auditory defect in Dio3−/− mice by deletion of TRα1

Dio3−/− mice are also known to exhibit deafness (18), but deletion of TRα1 did not reverse this defect (Fig. 8A). The sound pressure levels required to produce an ABR for a click stimulus or pure tone stimuli of 8, 16, and 32 kHz, were comparably elevated in Dio3−/− and Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− genotypes. The ABR waveforms of individual mice were poorly defined for both Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− and Dio3−/− genotypes. The magnitude of the evoked waveforms for some Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− mice was reduced compared with Dio3−/− mice, suggesting that the double mutation may exacerbate the defect in auditory function (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Nonreversal of auditory defect in Dio3−/− mice by deletion of TRα1. A, ABR thresholds for a click stimulus or pure tone stimuli of 8, 16, and 32 kHz were elevated in both Dio3−/− and Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− genotypes. The magnitude and statistical significance of defects in Dio3−/− mice compared with +/+ mice were consistent with previously reported data (means ± sem). *, P < 0.05 for Dio3−/− and Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− groups, individually, compared with +/+ mice; **, P < 0.01 for Dio3−/− and Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− groups, individually, compared with +/+ mice. B, Representative ABR waveforms for +/+, Dio3−/−, and Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− mice with thresholds of 50, 75, and 85 dB sound pressure level, respectively, for a click stimulus. The normalized voltage scale is different for each genotype. P values were obtained using a Student's t test or Mann-Whitney U test where appropriate.

Discussion

We report that Dio3−/− mice display abnormally accelerated cerebellar differentiation and locomotor behavioral defects, suggesting that D3 protects cerebellar tissues from inappropriate, premature stimulation by thyroid hormone. This study also indicates that the cerebellar, behavioral, and small stature phenotypes of Dio3−/− mice result specifically from inappropriate stimulation of the TRα1 receptor isoform, suggesting that particular combinations of deiodinases and T3 receptor isoforms determine the tissue and temporal specificity of thyroid hormone actions in development.

Deiodinase expression in cerebellar development

The D3 activity level in the cerebellum was low compared with other organs such as the eye. Nonetheless, the activity was specific, which was corroborated by 1) detection of both D3 activity and Dio3 mRNA with similar expression profiles in development and 2) loss of cerebellar D3 activity in Dio3−/− mice. The postnatal decline of D3 activity also resembles the trend reported previously for the rat (12, 27). D3 is considered to be an efficient enzyme, and it is possible that even traces of enzyme can influence cellular responses (14).

Limitations in the sensitivity of detection of low levels of Dio3 mRNA in mouse cerebellum may explain why detectable Dio3 mRNA declined in advance of D3 activity (18) and possibly also why previous in situ hybridization analyses did not mention detection of Dio3 mRNA in rat cerebellum (12, 37). Given this low expression level, available reagents do not allow us to identify the individual cell types in which D3 is expressed in the mouse cerebellum. In the chick cerebellum, D3 immunoreactivity has been reported in granule cells at immature ages and in Purkinje cells at older ages (38, 39).

The reciprocal switch in expression of the inactivating D3 and activating D2 enzymes during the first postnatal week may initiate a strictly timed amplification of T3 levels in the cerebellum at a key period of tissue expansion and differentiation (Fig. 1A). Switches in D3 and D2 expression may be a common means of neurodevelopmental control because similar trends also occur in the rodent hypothalamus and cerebrum (26, 27, 31), human fetal brain tissues (28), and inner ear in neonatal mice (16, 18).

D3 and the timing of tissue development

The accelerated cerebellar development in Dio3−/− mice suggests that normally, D3 reduces ligand concentration in the vicinity of TR-expressing target cells at immature stages. Treatment of rats throughout development with very high doses of T4 or T3, which presumably would overcome protection by D3, also cause premature disappearance of the EGL (19, 21, 40, 41) and impair foliation (22). Dio3−/− mice lack D3 in the cerebellum but also have abnormal T4 and T3 levels in the circulation such that both direct and indirect changes may exacerbate T3 exposure in the cerebellum. Neonatal Dio3−/− pups have 2- to 3-fold elevated levels of T3 that drop below normal before P10, whereas T4 remains chronically low over this period (31, 36). However, the cerebellar abnormalities become most obvious in Dio3−/− mice between P10 and P14, when circulating levels of T3 are below normal. This indicates that at least part of the phenotype results from intrinsic lack of protection in the cerebellum rather than elevated T3 levels in the circulation. Although there are no data available on T3 content in the immature cerebellum, the above proposal is supported by the report of enhanced expression of the T3-sensitive Nrgn (Rc3) gene in the cerebellum in juvenile Dio3−/− mice, at ages when serum T3 levels are below normal (15).

Accelerated differentiation is generally harmful because this does not allow adequate time for normal tissue maturation. In Dio3−/− mice, premature expansion of the molecular layer and Purkinje cell dendritic tree occurs during a period of synaptogenesis between Purkinje cells and projections from deeper lying neurons (21, 34, 42) such that the synaptic network may form abnormally. Synaptic maturation is known to be sensitive to thyroid hormone signaling because Thra+/PV mutant mice have reduced synaptic glucose utilization in the cerebellum and other brain regions (6). Premature differentiation induced by thyroid hormone also creates long-lasting damage in other systems. For example, T4 induces premature metamorphosis of flounder larvae, resulting in adult-like but abnormally small fish (43), whereas T3 excesses in neonatal mice accelerate cochlear differentiation and produce permanent deafness (18).

The cerebellar abnormalities plausibly contribute to the locomotor behavioral defects in Dio3−/− mice. Interestingly, an inability to invert and descend a vertical pole has also been observed for Dio2−/− mice (11), suggesting that the development of the underlying motor control is sensitive to too much or too little T3.

Possible cellular functions for D3 in the cerebellum

The impaired cerebellar foliation in Dio3−/− mice may be explained by imbalances in the rates of development of the EGL and the more slowly differentiating, underlying cortical layers (34, 44). The expression pattern of TRα1 suggests cell types that may respond to unconstrained T3 signaling. In rats in the second postnatal week, TRα1 mRNA is detected in postmitotic granule cells residing at the inward side of the EGL and in cells that have migrated into the IGL (5, 23, 24, 45). Nongranule cell types in the emerging molecular and internal granule cell layers may also indirectly influence granule cell maturation, survival, or migration. In mice, fluorescently tagged TRα1 protein expressed from the endogenous Thra gene has been detected in stellate, basket, glial, granule, and Purkinje cells (45).

Purkinje cells express both TRα1 and TRβ1 (5, 23), and both receptor isoforms could contribute to formation of the dendritic tree. T3 promotes the dendritic outgrowth of Purkinje cells in cerebellar cultures explanted from Thrb−/− mice but not Thra1−/− mice (7), suggesting that T3 acts on Purkinje cells via TRα1. The corrected molecular layer width in Dio3−/−;Thra1−/− mice compared with Dio3−/− mice supports the proposal that TRα1 mediates the premature outgrowth of Purkinje cell dendrites in response to unconstrained stimulation by T3 in Dio3−/− mice in vivo. Although the signals in the cerebellum that are regulated by T3 are incompletely understood (46–53), it is interesting that deletion of Gli2, a transcriptional activator downstream of Sonic hedgehog, results in impaired cerebellar foliation as in Dio3−/− mice (54, 55). In keratinocytes and skin carcinoma, Gli2 and Dio3 have been reported to act in the same pathway (56).

Combinatorial actions of deiodinases and TR isoforms

The improvement of cerebellar morphology and behavior by deletion of TRα1 in Dio3−/− mice reveals a close functional cooperation between a deiodinase and a particular TR isoform in vivo. Remarkably, deletion of TRα1 also improved body weight of Dio3−/− mice, suggesting that the small stature of Dio3−/− mice is mediated by overstimulation of TRα1, although it is unknown in which tissues these actions occur. In contrast, the dysfunctional thyroid gland and deafness of Dio3−/− mice were not corrected by deletion of TRα1, consistent with evidence that T3 primarily acts through TRβ in the pituitary-thyroid axis and auditory system (3, 30). Previous studies indicated that in the retina, D3 controls TRβ activity (17, 18), whereas in the cochlea, D3 as well as D2 are likely to control TRβ activity (16, 18).

It remains a challenge to understand how thyroid hormone elicits its wide variety of actions in different tissues in development. The differential expression of the small family of TRα1 and TRβ receptor isoforms provides one means of determining tissue-specific responses. The differential expression of activating D2 and inactivating D3 deiodinases superimposes another layer of control over these receptor isoforms in individual tissues and adds flexibility to the temporal control of T3 actions. The present data support the proposal that particular combinations of deiodinases and TR isoforms greatly extend the tissue-specific code that governs where and when T3 acts in development.

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Vennström for Thra1−/− mice.

This work was supported by ZonMw VENI Grant 91696017 and an Erasmus Medical Center Fellowship (to R.P.P.), National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants 5R01DK079946 and MH83220 (to A.H. and D.G.) and by the intramural research program at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases at the NIH.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

- ABR

- Auditory evoked brainstem response

- D2

- deiodinase type 2

- E18

- embryonic d 18

- EGL

- external germinal layer

- IGL

- internal granular layer

- P5

- postnatal d 5

- TRα1

- thyroid hormone receptor α1.

References

- 1. Eayrs JT, Taylor SH. 1951. The effect of thyroid deficiency induced by methyl thiouracil on the maturation of the central nervous system. J Anat 85:350–358 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Osler W. 1897. Sporadic cretinism in America. Transact Congr Am Physicians Surg 169–206 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Forrest D, Vennström B. 2000. Functions of thyroid hormone receptors in mice. Thyroid 10:41–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Venero C, Guadaño-Ferraz A, Herrero AI, Nordström K, Manzano J, de Escobar GM, Bernal J, Vennström B. 2005. Anxiety, memory impairment, and locomotor dysfunction caused by a mutant thyroid hormone receptor α1 can be ameliorated by T3 treatment. Genes Dev 19:2152–2163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morte B, Manzano J, Scanlan T, Vennstrom B, Bernal J. 2002. Deletion of the thyroid hormone receptor α 1 prevents the structural alterations of the cerebellum induced by hypothyroidism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:3985–3989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Itoh Y, Esaki T, Kaneshige M, Suzuki H, Cook M, Sokoloff L, Cheng SY, Nunez J. 2001. Brain glucose utilization in mice with a targeted mutation in the thyroid hormone α or β receptor gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:9913–9918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heuer H, Mason CA. 2003. Thyroid hormone induces cerebellar Purkinje cell dendritic development via the thyroid hormone receptor α1. J Neurosci 23:10604–10612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hashimoto K, Curty FH, Borges PP, Lee CE, Abel ED, Elmquist JK, Cohen RN, Wondisford FE. 2001. An unliganded thyroid hormone receptor causes severe neurological dysfunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:3998–4003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gereben B, Zavacki AM, Ribich S, Kim BW, Huang SA, Simonides WS, Zeöld A, Bianco AC. 2008. Cellular and molecular basis of deiodinase-regulated thyroid hormone signaling. Endocr Rev 29:898–938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guadaño-Ferraz A, Obregón MJ, St Germain DL, Bernal J. 1997. The type 2 iodothyronine deiodinase is expressed primarily in glial cells in the neonatal rat brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:10391–10396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Galton VA, Wood ET, St Germain EA, Withrow CA, Aldrich G, St Germain GM, Clark AS, St Germain DL. 2007. Thyroid hormone homeostasis and action in the type 2 deiodinase-deficient rodent brain during development. Endocrinology 148:3080–3088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tu HM, Legradi G, Bartha T, Salvatore D, Lechan RM, Larsen PR. 1999. Regional expression of the type 3 iodothyronine deiodinase messenger ribonucleic acid in the rat central nervous system and its regulation by thyroid hormone. Endocrinology 140:784–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kuiper GG, Kester MH, Peeters RP, Visser TJ. 2005. Biochemical mechanisms of thyroid hormone deiodination. Thyroid 15:787–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bianco AC, Salvatore D, Gereben B, Berry MJ, Larsen PR. 2002. Biochemistry, cellular and molecular biology, and physiological roles of the iodothyronine selenodeiodinases. Endocr Rev 23:38–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hernandez A, Quignodon L, Martinez ME, Flamant F, St Germain DL. 2010. Type 3 deiodinase deficiency causes spatial and temporal alterations in brain T3 signaling that are dissociated from serum thyroid hormone levels. Endocrinology 151:5550–5558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ng L, Goodyear RJ, Woods CA, Schneider MJ, Diamond E, Richardson GP, Kelley MW, Germain DL, Galton VA, Forrest D. 2004. Hearing loss and retarded cochlear development in mice lacking type 2 iodothyronine deiodinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:3474–3479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ng L, Lyubarsky A, Nikonov SS, Ma M, Srinivas M, Kefas B, St Germain DL, Hernandez A, Pugh EN, Jr, Forrest D. 2010. Type 3 deiodinase, a thyroid-hormone-inactivating enzyme, controls survival and maturation of cone photoreceptors. J Neurosci 30:3347–3357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ng L, Hernandez A, He W, Ren T, Srinivas M, Ma M, Galton VA, St Germain DL, Forrest D. 2009. A protective role for type 3 deiodinase, a thyroid hormone-inactivating enzyme, in cochlear development and auditory function. Endocrinology 150:1952–1960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Legrand J. 1984. Effects of thyroid hormones on central nervous system development. In: Yanai J, ed. Neurobehavorial teratology. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 331–363 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lauder JM. 1979. Granule cell migration in developing rat cerebellum. Influence of neonatal hypo- and hyperthyroidism. Dev Biol 70:105–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nicholson JL, Altman J. 1972. The effects of early hypo- and hyperthyroidism on the development of rat cerebellar cortex. I. Cell proliferation and differentiation. Brain Res 44:13–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lauder JM, Altman J, Krebs H. 1974. Some mechanisms of cerebellar foliation: effects of early hypo- and hyperthyroidism. Brain Res 76:33–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bradley DJ, Towle HC, Young WS., 3rd 1992. Spatial and temporal expression of α- and β-thyroid hormone receptor mRNAs, including the β2-subtype, in the developing mammalian nervous system. J Neurosci 12:2288–2302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mellström B, Naranjo JR, Santos A, Gonzalez AM, Bernal J. 1991. Independent expression of the α and β c-erbA genes in developing rat brain. Mol Endocrinol 5:1339–1350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fauquier T, Romero E, Picou F, Chatonnet F, Nguyen XN, Quignodon L, Flamant F. 2011. Severe impairment of cerebellum development in mice expressing a dominant-negative mutation inactivating thyroid hormone receptor α1 isoform. Dev Biol 356:350–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bates JM, St Germain DL, Galton VA. 1999. Expression profiles of the three iodothyronine deiodinases, D1, D2, and D3, in the developing rat. Endocrinology 140:844–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kaplan MM, Yaskoski KA. 1981. Maturational patterns of iodothyronine phenolic and tyrosyl ring deiodinase activities in rat cerebrum, cerebellum, and hypothalamus. J Clin Invest 67:1208–1214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kester MH, Martinez de Mena R, Obregon MJ, Marinkovic D, Howatson A, Visser TJ, Hume R, Morreale de Escobar G. 2004. Iodothyronine levels in the human developing brain: major regulatory roles of iodothyronine deiodinases in different areas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:3117–3128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hernandez A, Fiering S, Martinez E, Galton VA, St Germain D. 2002. The gene locus encoding iodothyronine deiodinase type 3 (Dio3) is imprinted in the fetus and expresses antisense transcripts. Endocrinology 143:4483–4486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wikström L, Johansson C, Saltó C, Barlow C, Campos Barros A, Baas F, Forrest D, Thorén P, Vennström B. 1998. Abnormal heart rate and body temperature in mice lacking thyroid hormone receptor α1. EMBO J 17:455–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hernandez A, Martinez ME, Fiering S, Galton VA, St Germain D. 2006. Type 3 deiodinase is critical for the maturation and function of the thyroid axis. J Clin Invest 116:476–484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fujita S, Shimada M, Nakamura T. 1966. H3-Thymidine autoradiographic studies on the cell proliferation and differentiation in the external and the internal granular layers of the mouse cerebellum. J Comp Neurol 128:191–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Goldowitz D, Hamre K. 1998. The cells and molecules that make a cerebellum. Trends Neurosci 21:375–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sillitoe RV, Joyner AL. 2007. Morphology, molecular codes, and circuitry produce the three-dimensional complexity of the cerebellum. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 23:549–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bernal J. 2007. Thyroid hormone receptors in brain development and function. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 3:249–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hernandez A, Martinez ME, Liao XH, Van Sande J, Refetoff S, Galton VA, St Germain DL. 2007. Type 3 deiodinase deficiency results in functional abnormalities at multiple levels of the thyroid axis. Endocrinology 148:5680–5687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Escámez MJ, Guadaño-Ferraz A, Cuadrado A, Bernal J. 1999. Type 3 iodothyronine deiodinase is selectively expressed in areas related to sexual differentiation in the newborn rat brain. Endocrinology 140:5443–5446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Verhoelst CH, Vandenborne K, Severi T, Bakker O, Zandieh Doulabi B, Leonard JL, Kühn ER, van der Geyten S, Darras VM. 2002. Specific detection of type III iodothyronine deiodinase protein in chicken cerebellar Purkinje cells. Endocrinology 143:2700–2707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Verhoelst CH, Roelens SA, Darras VM. 2005. Role of spatiotemporal expression of iodothyronine deiodinase proteins in cerebellar cell organization. Brain Res Bull 67:196–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gourdon J, Clos J, Coste C, Dainat J, Legrand J. 1973. Comparative effects of hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism and undernutrition on the protein and nucleic acid contents of the cerebellum in the young rat. J Neurochem 21:861–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Balázs R, Kovács S, Cocks WA, Johnson AL, Eayrs JT. 1971. Effect of thyroid hormone on the biochemical maturation of rat brain: postnatal cell formation. Brain Res 25:555–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rabié A, Favre C, Clavel MC, Legrand J. 1979. Sequential effects of thyroxine on the developing cerebellum of rats made hypothyroid by propylthiouracil. Brain Res 161:469–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Inui Y, Miwa S. 1985. Thyroid hormone induces metamorphosis of flounder larvae. Gen Comp Endocrinol 60:450–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mares V, Lodin Z. 1970. The cellular kinetics of the developing mouse cerebellum. II. The function of the external granular layer in the process of gyrification. Brain Res 23:343–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wallis K, Dudazy S, van Hogerlinden M, Nordström K, Mittag J, Vennström B. 2010. The thyroid hormone receptor α1 protein is expressed in embryonic postmitotic neurons and persists in most adult neurons. Mol Endocrinol 24:1904–1916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Manzano J, Morte B, Scanlan TS, Bernal J. 2003. Differential effects of triiodothyronine and the thyroid hormone receptor β-specific agonist GC-1 on thyroid hormone target genes in the brain. Endocrinology 144:5480–5487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Katoh-Semba R, Takeuchi IK, Semba R, Kato K. 2000. Neurotrophin-3 controls proliferation of granular precursors as well as survival of mature granule neurons in the developing rat cerebellum. J Neurochem 74:1923–1930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Doughty ML, Delhaye-Bouchaud N, Mariani J. 1998. Quantitative analysis of cerebellar lobulation in normal and agranular rats. J Comp Neurol 399:306–320 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Doughty ML, Lohof A, Campana A, Delhaye-Bouchaud N, Mariani J. 1998. Neurotrophin-3 promotes cerebellar granule cell exit from the EGL. Eur J Neurosci 10:3007–3011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chatonnet F, Guyot R, Picou F, Bondesson M, Flamant F. 2012. Genome-wide search reveals the existence of a limited number of thyroid hormone receptor α target genes in cerebellar neurons. PLoS One 7:e30703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Picou F, Fauquier T, Chatonnet F, Flamant F. 2012. A bimodal influence of thyroid hormone on cerebellum oligodendrocyte differentiation. Mol Endocrinol 26:608–618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Portella AC, Carvalho F, Faustino L, Wondisford FE, Ortiga-Carvalho TM, Gomes FC. 2010. Thyroid hormone receptor β mutation causes severe impairment of cerebellar development. Mol Cell Neurosci 44:68–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Quignodon L, Grijota-Martinez C, Compe E, Guyot R, Allioli N, Laperrière D, Walker R, Meltzer P, Mader S, Samarut J, Flamant F. 2007. A combined approach identifies a limited number of new thyroid hormone target genes in post-natal mouse cerebellum. J Mol Endocrinol 39:17–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Corrales JD, Blaess S, Mahoney EM, Joyner AL. 2006. The level of sonic hedgehog signaling regulates the complexity of cerebellar foliation. Development 133:1811–1821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Corrales JD, Rocco GL, Blaess S, Guo Q, Joyner AL. 2004. Spatial pattern of sonic hedgehog signaling through Gli genes during cerebellum development. Development 131:5581–5590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dentice M, Luongo C, Huang S, Ambrosio R, Elefante A, Mirebeau-Prunier D, Zavacki AM, Fenzi G, Grachtchouk M, Hutchin M, Dlugosz AA, Bianco AC, Missero C, Larsen PR, Salvatore D. 2007. Sonic hedgehog-induced type 3 deiodinase blocks thyroid hormone action enhancing proliferation of normal and malignant keratinocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:14466–14471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]