Abstract

Correct alignment of the mitotic spindle during cell division is crucial for cell fate determination, tissue organization, and development. Mutations causing brain diseases and cancer in humans and mice have been associated with spindle orientation defects. These defects are thought to lead to an imbalance between symmetric and asymmetric divisions, causing reduced or excessive cell proliferation. However, most of these disease-linked genes encode proteins that carry out multiple cellular functions. Here, we discuss whether spindle orientation defects are the direct cause for these diseases, or just a correlative side effect.

Introduction

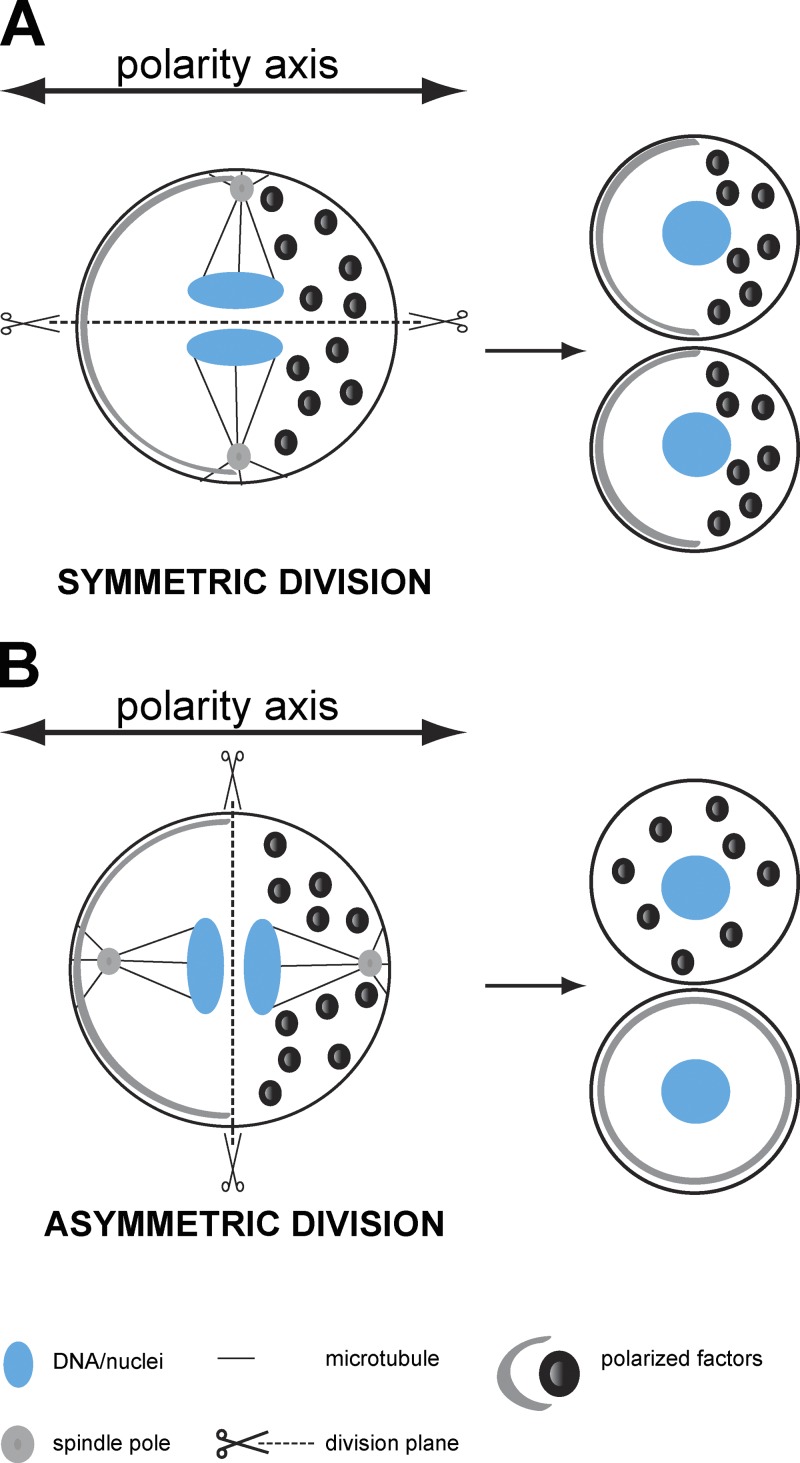

During cell division the orientation of the division plane usually defines the content, the position, and the fate of daughter cells within tissues (Siller and Doe, 2009). As a consequence, it delineates the architecture of the organ, its shape, and function (Castanon and González-Gaitán, 2011). In polarized cells, the division plane orientation determines whether a cell undergoes symmetric or asymmetric cell division (Fig. 1). In symmetric divisions the division plane is parallel to the polarity axis so that cell fate constituents, although polarized, will be equally segregated into daughter cells (Fig. 1 A). By contrast, if the division plane is perpendicular to the polarity axis, daughter cells will inherit different contents and diverge in their development (Fig. 1 B; Siller and Doe, 2009). In certain cases, however, cell fate can be induced regardless of division plane orientation (Clayton et al., 2007; Fleming et al., 2007; Kosodo et al., 2008).

Figure 1.

Orientation of the mitotic spindle: symmetric vs. asymmetric divisions. In polarized cells, orientation of the spindle perpendicular to the polarity axis causes a symmetric (proliferative) division (A). However, spindle orientation parallel to the polarity axis results in an asymmetric (differentiative) division (B).

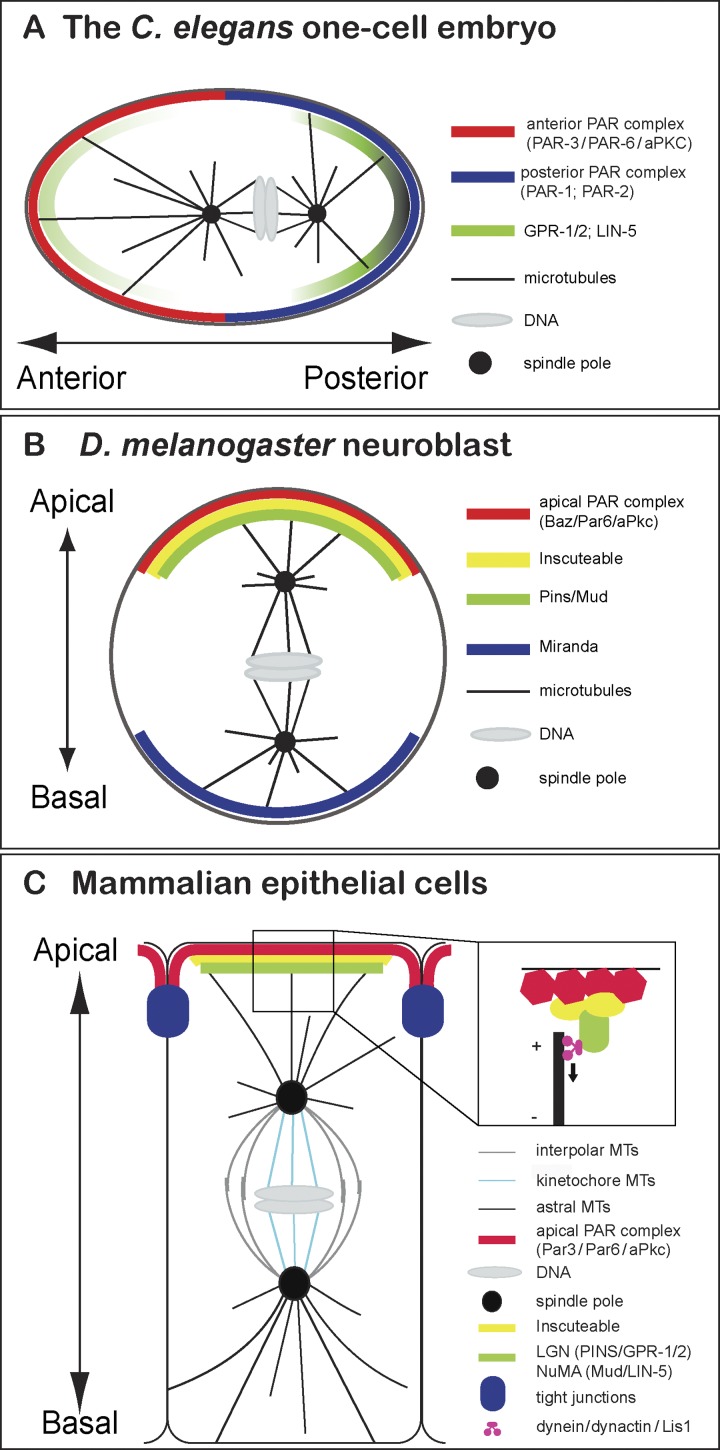

The orientation of the spindle, and the position of centrosomes, determines the orientation of the division plane (Bornens, 2012). Centrosomes are composed of centrioles and the pericentriolar material that nucleates astral and spindle microtubules. Astral microtubules connect the spindle to the cell cortex and control its orientation (Fig. 2). Studies in Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster have contributed considerably to our understanding of the molecular mechanisms regulating spindle orientation, which have been recently reviewed (Morin and Bellaïche, 2011; Fig. 2). However, the relevance of spindle orientation control in mammals had remained mostly unexplored. In recent years several studies linked spindle orientation defects to human diseases, in particular brain pathologies (Fish et al., 2006; Yingling et al., 2008; Godin et al., 2010; Lizarraga et al., 2010) and cancer (Pease and Tirnauer, 2011). Here, we explore the connection between human diseases and spindle orientation defects, and discuss to which extent these defects can be considered causative agents of these diseases.

Figure 2.

Spindle orientation is regulated by a conserved set of molecules in metazoans. (A) The C. elegans one-cell embryo is polarized along the anterior–posterior axis and divides asymmetrically in a somatic anterior cell (AB) and a posterior germline precursor cell (P1). The conserved PAR (partitioning defective) proteins are localized asymmetrically at the cortex: PAR-3, PAR-6, and PKC-3 at the anterior and PAR-1 and PAR-2 at the posterior. Spindle positioning is regulated downstream of polarity by GOA-1 and GPA-16 (Gα subunits of heterotrimeric G proteins), which localize around the entire cortex (not depicted), GPR-1 and GPR-2 (receptor-independent activators of G protein signaling), LIN-5 (coil-coiled protein), and the motor dynein (not depicted; Morin and Bellaïche, 2011). GPR-1/2 and LIN-5 are enriched at the posterior cortex in a PAR-dependent manner. The data suggest a model in which the GPR–GαGDP–LIN-5 complex promotes higher activity of dynein at the posterior cortex, resulting in posterior spindle pulling (Morin and Bellaïche, 2011). (B) D. melanogaster neuroblasts are stem cell–like precursors that generate the fly’s central nervous system. They divide asymmetrically along the apical–basal axis to give rise to a self-renewed neuroblast and a ganglion mother cell. Baz (PAR-3), Par6 (PAR-6), and aPKC (PKC-3) form a complex that localizes at the apical cortex. PINS (GPR-1/2) binds to Gα and localizes to the apical complex by interacting with the Baz-binding protein Inscuteable. (C) The same set of proteins regulates spindle orientation in mammalian cells (Lechler and Fuchs, 2005; Williams et al., 2011; see also Table 1).

Neurological diseases

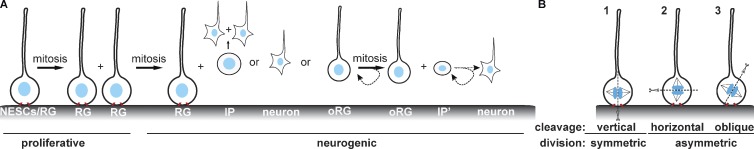

In vertebrates the central nervous system arises through a series of symmetric and asymmetric cell divisions (Fig. 3 A; Peyre and Morin, 2012; Shitamukai and Matsuzaki, 2012). At embryogenesis it is composed of a single layer of stem cells, the neuroepithelial stem cells (NESCs), which divide symmetrically. At the onset of neurogenesis, NESCs acquire characteristics of glial cells and are called radial glia cells (RGs). Both NESCs and RGs have apico–basal polarity and are also called apical progenitors. RGs divide asymmetrically to give origin to intermediate progenitors (IPs); IPs do not display apico–basal polarity, they detach from the apical side and divide one time to generate two neurons. Recently, a new kind of progenitor cell was identified, the outer radial glial cells (oRGs; Fietz et al., 2010; Hansen et al., 2010). These cells delaminate from the apical side but maintain an attachment to the basal side. oRGs can divide either asymmetrically, giving origin to an IP and an oRG, or symmetrically, to expand their pool.

Figure 3.

Mammalian neuronal progenitors and spindle orientation. (A) Cell subtypes in the developing mammalian brain. NESCs, neuroepithelial stem cells. RG, radial glia. IP, intermediate progenitor. oRG, outer radial glia. IP′, transit amplifying intermediate progenitors. Adherens junctions are in red. (B) A putative role of spindle orientation in the decision of symmetric vs. asymmetric division.

Spindles parallel to the apical plane will give rise to planar, symmetric (and proliferative) divisions, whereas vertical or oblique spindles will result in asymmetric (and differentiative) divisions (Fig. 3 B; (Huttner and Brand 1997; Haydar et al., 2003; Kosodo et al., 2004). This implies that interfering with spindle orientation to favor oblique, differentiative divisions will favor neurogenesis at the expense of stem cell pool expansion, leading to smaller brains. Consistent with this model, several genes implicated in neuropathologies resulting in small brains have been implicated in the control of spindle orientation. However, this model is controversial because in vivo observation of rodent neurogenesis showed that the choice between an asymmetric and a symmetric cell division does not only rely on the orientation of the spindle axis (Noctor et al., 2008). Moreover, it was shown that randomization of spindle orientation does not necessarily lead to a small brain (Konno et al., 2008). Keeping this controversy in mind, we summarize here the link between spindle orientation defects and three neurological diseases.

Microcephaly.

Primary microcephaly (MCPH) is an autosomal, recessive “small brain” disease. Microcephalic brains are structurally normal but exhibit reduced surface of the neocortex due to a reduced number of cortical neurons (Bond et al., 2002). Patients bearing microcephaly are mentally retarded but do not display other neurological disorders (Thornton and Woods, 2009). Genetically, the pathology is quite heterogeneous. Mutations in nine different genes have been linked with microcephalic brain (Table 1; Thornton and Woods, 2009; Alkuraya et al., 2011; Bakircioglu et al., 2011; Sir et al., 2011).

Table 1.

Genes regulating spindle orientation and mutated in diseases

| Gene name – species | Cellular function | Associated disease | Molecular characteristics | ||

| Vertebrate | Fly | Worm | |||

| lis1 | lis1 | lis-1 | Dynein-based movement, nucleokinesis (vertebrate, fly, worm), spindle orientation (vertebrate, fly), chromosome alignment (vertebrate), centrosome separation (fly, worm) spindle positioning (worm) (Swan et al., 1999; Dawe et al., 2001; Cockell et al., 2004; Siller and Doe, 2008; Wynshaw-Boris et al., 2010) | Lissencephaly (Reiner et al., 1993; Lo Nigro et al., 1997) | Coiled-coil domain, WD40 repeats |

| dcx | CG17528a | zyg-8 | Microtubule polymerization (vertebrate, worm), spindle orientation (vertebrate), spindle positioning (worm) (Gönczy et al., 2001; Pramparo et al., 2010; Wynshaw-Boris et al., 2010) | Lissencephaly (des Portes et al., 1998; Gleeson et al., 1998) | Doublecortin domain, kinase domain |

| nde1 | nudE | nud-2 | Centrosome duplication and maturation, chromosome alignment, spindle orientation, nucleokinesis (vertebrate), kinetochore function, chromosome congression, centrosome behavior (fly), nuclear migration (worm) (Wainman et al., 2009; Fridolfsson et al., 2010; Chansard et al., 2011) | Microlissencephaly (Alkuraya et al., 2011; Bakircioglu et al., 2011) | Coiled-coil domain |

| Gαi1, Gαi2, Gαi3 | Gαi1 | goa-1, gpa-16 | Spindle orientation (vertebrate, fly), ACD (fly, worm), spindle positioning, chromosome segregation (worm) (Srinivasan et al., 2003; Morin and Bellaïche, 2011) | – | GTPase subunit of heterotrimeric G proteins |

| numa | mud | lin-5 | ACD, chromosome segregation (vertebrate, fly, worm), spindle orientation, spindle pole integrity (vertebrate, fly), spindle positioning, cytokinesis (worm) (Lorson et al., 2000; Radulescu and Cleveland, 2010; Capalbo et al., 2011; Morin and Bellaïche, 2011; Kolano et al., 2012) | Leukemia (Wells et al., 1997) | Coiled-coil domain |

| pins/lgn/gpsm2/ags3 | pins | gpr-1, gpr-2 | ACD (vertebrate, fly, worm), spindle orientation (vertebrate, fly), chromosome segregation (vertebrate, worm), spindle positioning (worm) (Du et al., 2001; Srinivasan et al., 2003; Morin and Bellaïche, 2011) | Non-syndromic deafness (Walsh et al., 2010), brain malformations and deafness in Chudley-McCullough syndrome (Doherty et al., 2012) | GoLoco motif, tetratricopeptide (TPR) domains |

| insc | insc | – | Spindle orientation (vertebrate, fly), asymmetric cell division (fly) (Morin and Bellaïche, 2011) | – | Armadillo repeats |

| htt | htt | F21G4.6a | Neuronal transport, spindle orientation (vertebrate, fly) (Gunawardena et al., 2003; Godin and Humbert, 2011) | The Huntington’s Disease Collaborative Research Group (1993) | Polyglutamine tract, polyproline sequence, HEAT repeats |

| magoh | mago | mag-1 | RNA processing (vertebrate, fly worm), RNA localization (vertebrate, fly), spindle orientation and integrity, genomic stability (vertebrate), cytoskeleton organization (fly) (Li et al., 2000; Kataoka et al., 2001; Palacios, 2002; Le Hir and Andersen, 2008; Silver et al., 2010) | – | Mago nashi domain |

| apc | apc1, apc2 | apr-1 | Wnt signaling, ACD, microtubule stability (vertebrate, fly, worm), spindle orientation (vertebrate, fly), chromosome segregation, tumor suppressor (vertebrate) (Yamashita et al., 2003; Mizumoto and Sawa, 2007; McCartney and Näthke, 2008; Bahmanyar et al., 2009) | Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), gastrointestinal tumors (Minde et al., 2011) | Armadillo repeats, oligomerization domain, CRM1, β-catenin, microtubule-binding domains, |

| vegf | pvf1, pvf2, pvf3 | pvf-1 | Cell migration (vertebrate, fly), growth factor, oncogene, spindle orientation, angiogenesis (vertebrate) (Duchek et al., 2001; Tarsitano et al., 2006; Beck et al., 2011; Sitohy et al., 2012) | Epithelia skin cancer (Beck et al., 2011) | PDGF domain |

| vhl | vhl | vhl-1 | HIF1α regulation (vertebrate, fly, worm), microtubule stability, endocytosis, cell migration (vertebrate, fly), tumor suppressor, spindle orientation, genome integrity (vertebrate) (Thoma et al., 2009; Hsu, 2012) | Renal cell carcinoma (Kaelin, 2008) | Cullin E3 ubiquitin ligase |

| pten | pten | daf-18 | PI3K signaling (vertebrate, fly, worm), tumor suppressor, spindle orientation, genome integrity, cell growth (vertebrate), cell growth, actin cytoskeleton organization, (fly) (Ogg and Ruvkun, 1998; Stocker and Hafen, 2000; von Stein et al., 2005; Toyoshima et al., 2007; Hollander et al., 2011) | PTEN hamartoma tumor syndromes (PHTS) (Hollander et al., 2011) | Protein and lipid phosphatase |

| mcph1/microcephalin/brit1 | mcph1 | – | DNA damage response, centrosome integrity, chromosome segregation (vertebrate, fly), spindle orientation (vertebrate) (Thornton and Woods, 2009; Gruber et al., 2011) | Microcephaly (Jackson et al., 2002) | BRCA1 C-terminal (BRCT) domains |

| mcph2/wdr62 | – | – | Centrosome integrity, spindle orientation, chromosome alignment (vertebrate) (Bogoyevitch et al., 2012) | Microcephaly, lissencephaly, schizencephaly (Bilgüvar et al., 2010; Nicholas et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2010) | WD40 repeats |

| mcph3/cdk5rap2/cep215 | cnn | – | Centrosome assembly, spindle orientation, chromosome segregation (vertebrate, fly), DNA damage response (vertebrate) (Siller and Doe, 2008; Megraw et al., 2011) | Microcephaly (Bond et al., 2005) | Coiled-coil domains, centrosomin motives (CM) 1 and 2 |

| mcph4/cep152 | asl | – | Centriole formation and duplication (vertebrate, fly), genome integrity (vertebrate) (Kalay et al., 2011; Brito et al., 2012) | Microcephaly (Guernsey et al., 2010), Seckel syndrome (Kalay et al., 2011) | Coiled-coil domains |

| mcph5/aspm/calmbp1 | asp | aspm-1 | Spindle assembly, spindle orientation, cytokinesis (vertebrate, fly), the integrity of spindle poles and the central spindle (fly), meiotic spindle orientation (worm) (Varmark, 2004; van der Voet et al., 2009; Higgins et al., 2010) | Microcephaly (Bond et al., 2002), tumorigenesis (Lin et al., 2008) | Calponin homology (CH) domains, IQ-repeat motifs |

| mcph6/cenpj/cpap | sas4 | sas-4 | Centriole duplication (vertebrate, fly, worm), spindle orientation (vertebrate), ACD (fly) (Leidel and Gönczy, 2005; Basto et al., 2006; Kitagawa et al., 2011; Brito et al., 2012) | Microcephaly (Bond et al., 2005), Seckel syndrome (Al-Dosari et al., 2010) | Coiled-coil motives, PN2-3 domain, T-complex protein 10 (TCP) domain |

| mcph7/stil/sil | ana2 | sas-5 | Centriole duplication (vertebrate, fly, worm), spindle orientation (vertebrate, fly), ACD (fly) (Leidel and Gönczy, 2005; Wang et al., 2011; Brito et al., 2012) | Microcephaly (Kumar et al., 2009), leukemia (Aplan et al., 1991) | Coiled-coil domain, STIL/ANA2 (STAN) motif |

| cep63 | – | – | Spindle assembly, mitotic entry, genome maintenance, centrosome duplication (vertebrate) (Smith et al., 2009; Löffler et al., 2011) | Microcephaly (Sir et al., 2011) | Coiled-coil domains |

In many cases genes mutated in these pathologies control spindle orientation at the cellular level. ACD, asymmetric cell division.

The function of the genes has not been characterized.

All of the MCPH proteins can localize to centrosomes and are involved in centriole biogenesis, centrosome maturation, and spindle organization (Table 1; Bettencourt-Dias et al., 2011; Löffler et al., 2011). The most commonly affected gene is aspm (abnormal spindle-like microcephaly associated, MCPH5; Thornton and Woods, 2009). In human culture cells, ASPM localizes to centrosomes and spindle poles, similar to its fly and worm orthologue (Table 1; Saunders et al., 1997; Kouprina et al., 2005; van der Voet et al., 2009). Depletion of ASPM by RNAi results in spindle misorientation (Fish et al., 2006). A mutation in ASPM identified in microcephalic patients impairs the ability of ASPM to localize to centrosomes, suggesting that centrosomal localization is crucial for ASPM’s role (Higgins et al., 2010).

Mouse aspm is highly expressed during early brain development (Bond et al., 2002). Aspm also decorates centrosomes in dividing NESCs (Kouprina et al., 2005; Fish et al., 2006). NESCs depleted of ASPM by RNAi fail to orient the mitotic spindle perpendicular to the ventricular surface of the neuroepithelium, resulting in an asymmetric, differentiative division instead of the symmetric proliferative divisions, therefore reducing the pool of neuronal precursors (Fig. 3; Fish et al., 2006). However, a mutant that encodes a truncated version of ASPM results in microcephaly without interfering with spindle orientation (Pulvers et al., 2010).

How ASPM regulates spindle orientation is not known. In C. elegans, ASPM-1 binds to the NuMA homologue LIN-5 and is required to recruit it to meiotic spindle poles. LIN-5 together with dynein promotes meiotic spindle rotation (van der Voet et al., 2009). Therefore, it is possible that ASPM controls spindle orientation in mice and humans by recruiting NuMA to centrosomes.

Two other genes mutated in microcephaly, Microcephalin (MCPH1) and CDK5RAP2 (MCPH3), are required for timely centrosome maturation, which allows centrosomes to nucleate many more microtubules in mitosis (Barr et al., 2010; Gruber et al., 2011). In mcph1-deleted mice the checkpoint kinase Chk1 does not localize to centrosomes, resulting in premature mitotic entry in the presence of immature centrosomes. This causes a spindle alignment defect, which increases asymmetric cell divisions of neuroprogenitors at the expense of symmetric, proliferative divisions, and results in smaller brains (Gruber et al., 2011) Similarly, in CDK5RAP2-depleted cells the checkpoint kinase Chk1 is not localized to centrosomes and spindles are misoriented (Barr et al., 2010; Lizarraga et al., 2010).

Depletion of CPAP (MCPH6) and STIL (MCPH7), which are essential for centriole biogenesis, result in spindle orientation defects in culture cells (Kitagawa et al., 2011; Brito et al., 2012), suggesting that impairing centriole biogenesis leads to spindle misalignment. A newly identified mcph gene, cep63, is also required for centriole formation (Sir et al., 2011). CEP63 is important to localize CEP152 (MCPH4) to centrioles, while CEP152 recruits CPAP to centrosomes (Cizmecioglu et al., 2010; Sir et al., 2011). However, a role for CEP63 and CEP152 in spindle orientation has not been investigated.

Lissencephaly.

Morphologically, lissencephalic brains are small, and have almost a smooth surface and abnormal organization of the neocortex due to neuronal migration defects (lissencephaly means “smooth brain”; Wynshaw-Boris, et al., 2010). Patients are mentally retarded, epileptic, and die during their childhood. Genetic analyses of cases with type 1 lissencephaly identified mutations in mainly one gene, lis1 (Reiner et al., 1993; Lo Nigro et al., 1997). The role of Lis1 in spindle orientation was first reported in culture epithelial and neuronal cells where Lis1 stabilizes microtubules via interaction with the dynein–dynactin complex (Faulkner et al., 2000; Smith et al., 2000). In vitro and structural studies indicate that Lis1 and its cofactor NudE regulate dynein, and that Lis1 transforms dynein in a processive, high-load microtubule motor protein (McKenney et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2012). Such a role fits with the functions that have been assigned to Lis1, such as transport of nuclei, chromosomes, centrosomes, large vesicles in axons, or in the case of spindle orientation, pulling of the entire spindle at the cell cortex (Table 1 and Fig. 2; Wynshaw-Boris, et al., 2010).

Yingling et al. (2008) have shown that depletion of Lis1 in NESCs results in less stable astral microtubules and loss of dynein cortical localization in mouse. This deflects the mitotic spindle from a horizontal position, leading to premature asymmetric divisions and finally apoptosis of the arising daughter cells. As a consequence, the pool of brain stem cells is massively diminished early in development, decreasing the number of neurons, causing severe brain abnormalities and eventually embryonic death (Yingling et al., 2008).

Consistent with a role for Lis1 in regulation of spindle orientation in mouse, recent work shows that mutations in the exon junction protein Magoh results in reduced Lis1 levels, spindle orientation defects, and abnormal brain development (Silver et al., 2010). Although expression of Lis1 in these mutants can rescue the brain developmental defects, the authors did not investigate whether the spindle orientation defect was also rescued (Silver et al., 2010). Furthermore, mutations in genes encoding for DCX (doublecortin) and NDE1, both of which function in dynein-dependent processes and physically interact with Lis1, result in spindle orientation defects in C. elegans and mice (Gönczy et al., 2001; Feng and Walsh, 2004; Pramparo et al., 2010) and cause lissencephaly in humans (des Portes et al., 1998; Gleeson et al., 1998; Alkuraya et al., 2011; Bakircioglu et al., 2011).

Huntington.

Another pathology where spindle orientation may play a role is Huntington’s disease. Huntington’s disease is a neurodegenerative disorder that manifests in adult life and leads to cognitive defects, dementia, and muscle coordination defects (Borrell-Pagès et al., 2006). Huntingtin (htt), the protein mutated in Huntington’s disease, interacts with microtubules and dynein and mediates neuronal transport (Borrell-Pagès et al., 2006). In cultured cells, depletion of htt results in the loss of dynein, dynactin, and NuMA at centrosomes and in spindle misalignment (Godin et al., 2010). Huntingtin is also required for proper spindle orientation in D. melanogaster neuroblasts and mouse cortical progenitors (Godin et al., 2010). As Huntington is a disease that develops later in life, this finding raises the possibility that a defect of neurogenesis during embryonic development contributes to the origin of the disease.

Carcinogenesis

Because the loss of several tumor suppressor genes or overexpression of certain oncogenes results in spindle orientation defects, carcinogenesis is the second disease class that has been associated with defective spindle orientation (Pease and Tirnauer, 2011). Cancer formation results from the uncontrolled proliferation of cells, which impairs tissue function, and from the ability of cells to invade new tissues during metastasis. One prominent hypothesis is that spindle orientation defects increase cell numbers by suppressing the asymmetric, differentiative divisions of stem cells while increasing their symmetric, proliferative divisions (Morrison and Kimble, 2006). Moreover, defective spindle orientation might disorganize tissue architecture, a typical feature of malignant transformation (McAllister and Weinberg, 2010). The best evidence for a defective fate determination of stem cells is found in D. melanogaster, where there is a clear distinction between asymmetric differentiative and symmetric proliferative stem cell divisions, and where loss of asymmetric stem cell division results in an uncontrolled invasive cell proliferation (Caussinus and Gonzalez, 2005; Lesage et al., 2010). More recent studies postulated a similar mechanism in mammals, based on experiments performed in mammospheres and mouse models for colon cancer or gliomas (Cicalese et al., 2009; Quyn et al., 2010; Sugiarto et al., 2011). This mechanism could favor the uncontrolled proliferation of stem cells, leading to the formation of cancer stem cells. Indeed, in some cancers, such as papillomas (Driessens et al., 2012), cancer stem cells undergo rapid proliferative divisions, with the ability to be at the origin of an entire tumor cell population. However, there are several caveats to consider. First, there is conflicting evidence as to whether mammalian stem cells undergo asymmetric or symmetric cell divisions (Quyn et al., 2010; Snippert et al., 2010; Bellis et al., 2012); second, the idea of cancer stem cells itself is hotly debated, both as a concept and whether it is applicable to all cancer types (Lobo et al., 2007; Magee et al., 2012); third, cancer stem cells may not necessarily originate from stem cells. Keeping these caveats in mind, we present here the molecular evidence linking spindle orientation to carcinogenesis.

APC: Adenomatous polyposis coli.

Mutations in the apc gene are found in a vast majority of colon cancers and in familial adenomatous polyposis disease, where they predispose patients to intestinal cancer (Fodde and Smits, 2001; Minde et al., 2011). APC is a tumor suppressor that inhibits canonical Wnt signaling by impairing β-catenin–dependent transcriptional activity (Reya and Clevers, 2005). APC can inhibit β-catenin through direct binding, or by promoting its nuclear export to favor its ubiquitin-dependent degradation. APC also plays a crucial role during mitosis, where it binds the microtubule plus-end scaffold protein EB1 (Su et al., 1995) to promote microtubule stability (Fodde and Smits, 2001; Kaplan et al., 2001). APC mutations or deletions cause spindle orientation and chromosome alignment defects, and lead to chromosomal instability and cytokinesis failure in mammalian cells (Fodde and Smits, 2001; Kaplan et al., 2001; Green and Kaplan, 2003; Tighe et al., 2004; Caldwell et al., 2007). Furthermore, in D. melanogaster APC is required for correct spindle orientation and asymmetric cell division in germline stem cells and in the syncytium (McCartney et al., 2001; Yamashita et al., 2003), but not in neuroblasts (Rusan et al., 2008).

The molecular mechanism by which APC controls spindle orientation is still under debate: it could be its ability to stabilize astral microtubules and/or its regulation of cell polarity (Akiyama and Kawasaki, 2006). In vivo APC mutations or loss of APC lead to a rapid cellular transformation, and to cancer formation in the small and large intestine in mice; it correlates with misoriented spindles in both compartments, suggesting that loss of asymmetric divisions promotes tissue overgrowth (Caldwell et al., 2007; Fleming et al., 2009; Quyn et al., 2010). This could occur either through an aberrant distribution of cell fate determinants into daughter cells and/or incorrect placement of the arising daughters within the tissue (Näthke, 2006). However, a recent report challenged this view, showing that APC mutant mice develop colon cancer in the absence of spindle orientation defects (Bellis et al., 2012). Furthermore, the induction of β-catenin signaling alone is sufficient to induce carcinogenesis, implying that the tumor suppressor activity of APC cannot be explained only in terms of spindle orientation control (Harada et al., 1999).

VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor.

VEGF is an oncogene that promotes angiogenesis in cancer tissues (Ferrara, 2002). Studies investigating the behavior of cancer stem cells in skin papilloma found that inhibition of VEGF results in reduced proliferative symmetric stem cell divisions, reappearance of asymmetric divisions, and tumor regression. These asymmetric divisions correlate with a mitotic spindle oriented perpendicular to the epidermis (Beck et al., 2011), suggesting that high levels of VEGF impair spindle orientation.

VHL: von Hippel-Lindau gene.

Mutations in vhl, a tumor suppressor gene, predispose patients to cancer formation in multiple tissues, in particular in kidneys (Frew and Krek, 2007; Kaelin, 2008). VHL is an adaptor protein with multiple interactors and functions, one of which is to target the hypoxia-inducible factor 1 α, HIF1α, for ubiquitin-dependent degradation (Kaelin, 2008). Loss of VHL leads to angiogenesis, thus favoring cancer growth. However, VHL also regulates microtubule dynamics both in vertebrates and flies (Hergovich et al., 2003; Thoma et al., 2007, 2009; Duchi et al., 2010), and it plays a crucial role during vertebrate mitosis. VHL depletion or knock-out in culture cells randomizes spindle orientation due to unstable astral microtubules, and weakens the spindle checkpoint, resulting in chromosomal instability (Thoma et al., 2009). Cancer patients can carry vhl mutations affecting only HIF1α stability or only microtubule stability, indicating that both phenotypes are sufficient to induce tumorigenesis (Thoma et al., 2009). One attractive hypothesis is that the elongation of renal tubes requires oriented cell divisions; misregulation of division plane leads to an increase in tube diameter and cyst development, a feature of VHL syndrome (Fischer et al., 2006). However, only very few of those cysts will develop into a carcinoma, suggesting that spindle orientation defects and the ensuing cysts are not sufficient, per se, to induce cancer formation in kidneys. Moreover, loss of VHL may prone cells for aneuploidy, another potential cause of cancer formation (Weaver and Cleveland, 2009).

PTEN: Phosphatase and tensin homologue.

PTEN is a lipid phosphatase that controls cell growth by regulating phosphatidylinositol kinase signaling, and it is one of the most frequently mutated tumor suppressor genes (Hollander et al., 2011). PTEN was shown to control spindle orientation in human tissue culture cells (Toyoshima et al., 2007). This study found that phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PIP3) molecules are enriched at the cell equator, and that PIP3 localization directs the correct localization of dynein at the cell cortex. Loss of PTEN or inactivation of PI3-kinase respectively saturate or abolish PIP3 localization in the entire cell cortex, leading to randomization of spindle orientation (Toyoshima et al., 2007). However, as these data were only obtained in cultured cell lines, it will be important to examine whether loss of PTEN also impairs spindle orientation in tissues.

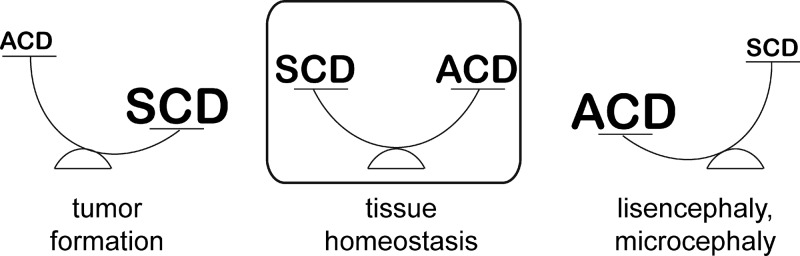

Spindle orientation defects: Cause, aggravating factor, or symptom?

Given the correlation between spindle orientation defects and the appearance of neurological diseases and cancers, it is tempting to postulate that the loss of spindle orientation control is at the origin of these pathologies. Although neurological disorders would be caused by a premature shift from symmetric to asymmetric divisions and consequent reduction in neuron number, cancers would be the results of uncontrolled symmetric and thus proliferative cell divisions (Fig. 4). This would reflect the fact that the controlled balance of symmetric or asymmetric cell divisions is essential for development and tissue homeostasis, and that the consequences of spindle misorientation strongly depend on the biological context. A causal link between spindle orientation defects and carcinogenesis has been made in D. melanogaster (Caussinus and Gonzalez, 2005; Castellanos et al., 2008). In mammals, however, this is only an attractive hypothesis based on correlative evidence. One of the reasons is that all the mutations or gene deletions that we have discussed lead to pleiotropic effects. This ranges from induction of apoptosis (e.g., MCPH1, CDK5RAP2, or Lis1), loss of growth control (e.g., APC, PTEN, VEGF), chromosome segregation defects (e.g., Lis1, APC, VHL, MCPH1, CDK5RAP2), and changes in other microtubule-dependent processes, such as intracellular transport or cell migration (Table 1 and references within). All these processes are implicated in neuropathologies or tumor formation. Moreover, many of those gene products are also present in cilia (e.g., MCPH4, 6, and 7; Bettencourt-Dias et al., 2011) or involved in cilia formation (VHL and PTEN; Frew et al., 2008; Hsu, 2012), which could suggest that cilia defects might be at the origin of some pathologies. Conversely, a number of gene deletions or mutations classically associated with ciliopathies, such as Pkd1 and ITF88, also impair spindle orientation, raising the possibility that spindle orientation defects play an aggravating role in ciliopathies (Fischer et al., 2006; Delaval et al., 2011). Furthermore, it is difficult to establish a direct causality because mutations affecting spindle orientation can have tissue-specific effects. At present it is therefore impossible to determine whether spindle orientation defects are a cause, an aggravating factor, or just a by-product of these diseases.

Figure 4.

Equilibrium between symmetric and asymmetric divisions confers proper development and tissue homeostasis. Schematic representation of the balance between symmetric and asymmetric cell division and its relevance. ACD, asymmetric cell division. SCD, symmetric cell division.

One way to address this question would be to test whether rescuing spindle orientation defects by reintroducing a separation-of-function mutant suppresses the corresponding pathology. The C-terminal truncation of aspm in mice is an example for this approach (Pulvers et al., 2010). This truncation does not disrupt spindle orientation, but still leads to microcephaly, indicating that spindle orientation defects are not essential for primary microcephaly. Another possibility would be to introduce a deletion in a second gene to rescue the spindle orientation defects. For example, to counteract a VHL mutant that cannot stabilize microtubules, one could delete a gene that destabilizes microtubules, like stathmin-1 (Belmont and Mitchison, 1996). Stathmin-1 is an oncogene, but knock-out mice are viable with only minor sociological defects (Schubart et al., 1996; Shumyatsky et al., 2005). Therefore, one could test whether stathmin-1 deletion suppresses both spindle defects and cancerogenesis in such a background. One caveat for the interpretation of this strategy is that the “suppressor” deletion may have other, unwanted effects. Another caveat is that these experiments only reveal whether spindle orientation defects are essential for disease development in a particular genetic background, and not whether spindle orientation defects, per se, can induce a pathological state.

A more direct approach will be to test the effect of a “pure” spindle orientation defect, which has no other side-effects. Two ideal candidates are LGN and Insc, which only affect spindle orientation, and do not impair cell polarity or other aspects of mitotic progression in mammalian systems (Zheng et al., 2010; Postiglione et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2011). Interestingly, both genes have been deleted in mice to study their contribution to brain development (Konno et al., 2008; Postiglione et al., 2011). Loss of LGN randomized mitotic spindle orientation and led to tissue architecture defects but did not result in smaller brains. On the contrary, loss of Insc led to depletion of vertical and oblique divisions (Fig. 3 B), and this resulted in production of fewer neurons and smaller brains. In the future it will be necessary to closely compare these phenotypes and to combine both mutants for epistasis analysis to investigate the outcome and better understand the role of spindle orientation in this process. Furthermore, it will be interesting to test if mutations in LGN or Insc are ever found in human microcephaly patients.

With regards to carcinogenesis, it is striking that LGN mutant mice have minor developmental defects, but that cancers have not been reported (Konno et al., 2008; Williams et al., 2011). However, before drawing strong conclusions, these mice should be analyzed for spindle orientation defects in other tissues. Furthermore, one should investigate whether some of the LGN functions are taken over by the closely related protein, AGS3 (Sanada and Tsai, 2005; Siller and Doe, 2009).

It will be also important to investigate if spindle orientation defects can play an aggravating role in cancer by combining spindle orientation defects with cancer mutations and testing for synergistic effects. Ideal cancer mutations could be loss of the tumor suppressor p53, or overexpression of the Ras oncogene (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2000). The combinations of mutations will be interesting even if spindle orientation defects, per se, are sufficient to induce tumor formation, as they can reveal whether spindle orientation defects lead to an earlier onset of tumor formation and/or accelerate the progression of the tumor. Overall, such investigations will allow one to test the attractive hypothesis that spindle orientation is a critical process for those diseases, opening up new important paths for possible treatments of these pathologies.

Acknowledgments

A. Noatynska and M. Gotta are supported by the Swiss National Research Foundation and the University of Geneva. P. Meraldi is supported by the Swiss National Research Foundation, the University of Geneva, the Swiss Cancer League, and the ETH Zurich.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- IP

- intermediate progenitor

- MCPH

- microcephaly

- NESC

- neuroepithelial stem cell. oRG, outer radial glia

- RG

- radial glia

References

- Akiyama T., Kawasaki Y. 2006. Wnt signalling and the actin cytoskeleton. Oncogene. 25:7538–7544 10.1038/sj.onc.1210063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Dosari M.S., Shaheen R., Colak D., Alkuraya F.S. 2010. Novel CENPJ mutation causes Seckel syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 47:411–414 10.1136/jmg.2009.076646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkuraya F.S., Cai X., Emery C., Mochida G.H., Al-Dosari M.S., Felie J.M., Hill R.S., Barry B.J., Partlow J.N., Gascon G.G., et al. 2011. Human mutations in NDE1 cause extreme microcephaly with lissencephaly [corrected]. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 88:536–547 (corrected) 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aplan P.D., Lombardi D.P., Kirsch I.R. 1991. Structural characterization of SIL, a gene frequently disrupted in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:5462–5469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahmanyar S., Nelson W.J., Barth A.I. 2009. Role of APC and its binding partners in regulating microtubules in mitosis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 656:65–74 10.1007/978-1-4419-1145-2_6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakircioglu M., Carvalho O.P., Khurshid M., Cox J.J., Tuysuz B., Barak T., Yilmaz S., Caglayan O., Dincer A., Nicholas A.K., et al. 2011. The essential role of centrosomal NDE1 in human cerebral cortex neurogenesis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 88:523–535 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr A.R., Kilmartin J.V., Gergely F. 2010. CDK5RAP2 functions in centrosome to spindle pole attachment and DNA damage response. J. Cell Biol. 189:23–39 10.1083/jcb.200912163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basto R., Lau J., Vinogradova T., Gardiol A., Woods C.G., Khodjakov A., Raff J.W. 2006. Flies without centrioles. Cell. 125:1375–1386 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck B., Driessens G., Goossens S., Youssef K.K., Kuchnio A., Caauwe A., Sotiropoulou P.A., Loges S., Lapouge G., Candi A., et al. 2011. A vascular niche and a VEGF-Nrp1 loop regulate the initiation and stemness of skin tumours. Nature. 478:399–403 10.1038/nature10525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellis J., Duluc I., Romagnolo B., Perret C., Faux M.C., Dujardin D., Formstone C., Lightowler S., Ramsay R.G., Freund J.N., De Mey J.R. 2012. The tumor suppressor Apc controls planar cell polarities central to gut homeostasis. J. Cell Biol. 198:331–341 10.1083/jcb.201204086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmont L.D., Mitchison T.J. 1996. Identification of a protein that interacts with tubulin dimers and increases the catastrophe rate of microtubules. Cell. 84:623–631 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81037-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettencourt-Dias M., Hildebrandt F., Pellman D., Woods G., Godinho S.A. 2011. Centrosomes and cilia in human disease. Trends Genet. 27:307–315 10.1016/j.tig.2011.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilgüvar K., Oztürk A.K., Louvi A., Kwan K.Y., Choi M., Tatli B., Yalnizoğlu D., Tüysüz B., Cağlayan A.O., Gökben S., et al. 2010. Whole-exome sequencing identifies recessive WDR62 mutations in severe brain malformations. Nature. 467:207–210 10.1038/nature09327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogoyevitch M.A., Yeap Y.Y., Qu Z., Ngoei K.R., Yip Y.Y., Zhao T.T., Heng J.I., Ng D.C. 2012. WD40-repeat protein 62 is a JNK-phosphorylated spindle pole protein required for spindle maintenance and timely mitotic progression. J. Cell Sci. 10.1242/jcs.107326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond J., Roberts E., Mochida G.H., Hampshire D.J., Scott S., Askham J.M., Springell K., Mahadevan M., Crow Y.J., Markham A.F., et al. 2002. ASPM is a major determinant of cerebral cortical size. Nat. Genet. 32:316–320 10.1038/ng995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond J., Roberts E., Springell K., Lizarraga S.B., Scott S., Higgins J., Hampshire D.J., Morrison E.E., Leal G.F., Silva E.O., et al. 2005. A centrosomal mechanism involving CDK5RAP2 and CENPJ controls brain size. Nat. Genet. 37:353–355 10.1038/ng1539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornens M. 2012. The centrosome in cells and organisms. Science. 335:422–426 10.1126/science.1209037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell-Pagès M., Zala D., Humbert S., Saudou F. 2006. Huntington’s disease: from huntingtin function and dysfunction to therapeutic strategies. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 63:2642–2660 10.1007/s00018-006-6242-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito D.A., Gouveia S.M., Bettencourt-Dias M. 2012. Deconstructing the centriole: structure and number control. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 24:4–13 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell C.M., Green R.A., Kaplan K.B. 2007. APC mutations lead to cytokinetic failures in vitro and tetraploid genotypes in Min mice. J. Cell Biol. 178:1109–1120 10.1083/jcb.200703186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capalbo L., D’Avino P.P., Archambault V., Glover D.M. 2011. Rab5 GTPase controls chromosome alignment through Lamin disassembly and relocation of the NuMA-like protein Mud to the poles during mitosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108:17343–17348 10.1073/pnas.1103720108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castanon I., González-Gaitán M. 2011. Oriented cell division in vertebrate embryogenesis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 23:697–704 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos E., Dominguez P., Gonzalez C. 2008. Centrosome dysfunction in Drosophila neural stem cells causes tumors that are not due to genome instability. Curr. Biol. 18:1209–1214 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caussinus E., Gonzalez C. 2005. Induction of tumor growth by altered stem-cell asymmetric division in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Genet. 37:1125–1129 10.1038/ng1632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chansard M., Hong J.H., Park Y.U., Park S.K., Nguyen M.D. 2011. Ndel1, Nudel (Noodle): flexible in the cell? Cytoskeleton (Hoboken). 68:540–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicalese A., Bonizzi G., Pasi C.E., Faretta M., Ronzoni S., Giulini B., Brisken C., Minucci S., Di Fiore P.P., Pelicci P.G. 2009. The tumor suppressor p53 regulates polarity of self-renewing divisions in mammary stem cells. Cell. 138:1083–1095 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cizmecioglu O., Arnold M., Bahtz R., Settele F., Ehret L., Haselmann-Weiss U., Antony C., Hoffmann I. 2010. Cep152 acts as a scaffold for recruitment of Plk4 and CPAP to the centrosome. J. Cell Biol. 191:731–739 10.1083/jcb.201007107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton E., Doupé D.P., Klein A.M., Winton D.J., Simons B.D., Jones P.H. 2007. A single type of progenitor cell maintains normal epidermis. Nature. 446:185–189 10.1038/nature05574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockell M.M., Baumer K., Gönczy P. 2004. lis-1 is required for dynein-dependent cell division processes in C. elegans embryos. J. Cell Sci. 117:4571–4582 10.1242/jcs.01344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawe A.L., Caldwell K.A., Harris P.M., Morris N.R., Caldwell G.A. 2001. Evolutionarily conserved nuclear migration genes required for early embryonic development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Genes Evol. 211:434–441 10.1007/s004270100176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaval B., Bright A., Lawson N.D., Doxsey S. 2011. The cilia protein IFT88 is required for spindle orientation in mitosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 13:461–468 10.1038/ncb2202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- des Portes V., Pinard J.M., Billuart P., Vinet M.C., Koulakoff A., Carrié A., Gelot A., Dupuis E., Motte J., Berwald-Netter Y., et al. 1998. A novel CNS gene required for neuronal migration and involved in X-linked subcortical laminar heterotopia and lissencephaly syndrome. Cell. 92:51–61 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80898-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty D., Chudley A.E., Coghlan G., Ishak G.E., Innes A.M., Lemire E.G., Rogers R.C., Mhanni A.A., Phelps I.G., Jones S.J., et al. ; FORGE Canada Consortium 2012. GPSM2 mutations cause the brain malformations and hearing loss in Chudley-McCullough syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 90:1088–1093 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driessens G., Beck B., Caauwe A., Simons B.D., Blanpain C. 2012. Defining the mode of tumour growth by clonal analysis. Nature. 488:527–530 10.1038/nature11344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Q., Stukenberg P.T., Macara I.G. 2001. A mammalian Partner of inscuteable binds NuMA and regulates mitotic spindle organization. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:1069–1075 10.1038/ncb1201-1069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchek P., Somogyi K., Jékely G., Beccari S., Rørth P. 2001. Guidance of cell migration by the Drosophila PDGF/VEGF receptor. Cell. 107:17–26 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00502-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchi S., Fagnocchi L., Cavaliere V., Hsouna A., Gargiulo G., Hsu T. 2010. Drosophila VHL tumor-suppressor gene regulates epithelial morphogenesis by promoting microtubule and aPKC stability. Development. 137:1493–1503 10.1242/dev.042804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner N.E., Dujardin D.L., Tai C.Y., Vaughan K.T., O’Connell C.B., Wang Y., Vallee R.B. 2000. A role for the lissencephaly gene LIS1 in mitosis and cytoplasmic dynein function. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:784–791 10.1038/35041020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y., Walsh C.A. 2004. Mitotic spindle regulation by Nde1 controls cerebral cortical size. Neuron. 44:279–293 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N. 2002. Role of vascular endothelial growth factor in physiologic and pathologic angiogenesis: tkherapeutic implications. Semin. Oncol. 29(6, Suppl 16):10–14 10.1016/S0093-7754(02)70064-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fietz S.A., Kelava I., Vogt J., Wilsch-Bräuninger M., Stenzel D., Fish J.L., Corbeil D., Riehn A., Distler W., Nitsch R., Huttner W.B. 2010. OSVZ progenitors of human and ferret neocortex are epithelial-like and expand by integrin signaling. Nat. Neurosci. 13:690–699 10.1038/nn.2553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer E., Legue E., Doyen A., Nato F., Nicolas J.F., Torres V., Yaniv M., Pontoglio M. 2006. Defective planar cell polarity in polycystic kidney disease. Nat. Genet. 38:21–23 10.1038/ng1701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish J.L., Kosodo Y., Enard W., Pääbo S., Huttner W.B. 2006. Aspm specifically maintains symmetric proliferative divisions of neuroepithelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103:10438–10443 10.1073/pnas.0604066103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming E.S., Zajac M., Moschenross D.M., Montrose D.C., Rosenberg D.W., Cowan A.E., Tirnauer J.S. 2007. Planar spindle orientation and asymmetric cytokinesis in the mouse small intestine. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 55:1173–1180 10.1369/jhc.7A7234.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming E.S., Temchin M., Wu Q., Maggio-Price L., Tirnauer J.S. 2009. Spindle misorientation in tumors from APC(min/+) mice. Mol. Carcinog. 48:592–598 10.1002/mc.20506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fodde R., Smits R. 2001. Disease model: familial adenomatous polyposis. Trends Mol. Med. 7:369–373 10.1016/S1471-4914(01)02050-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frew I.J., Krek W. 2007. Multitasking by pVHL in tumour suppression. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 19:685–690 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frew I.J., Thoma C.R., Georgiev S., Minola A., Hitz M., Montani M., Moch H., Krek W. 2008. pVHL and PTEN tumour suppressor proteins cooperatively suppress kidney cyst formation. EMBO J. 27:1747–1757 10.1038/emboj.2008.96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridolfsson H.N., Ly N., Meyerzon M., Starr D.A. 2010. UNC-83 coordinates kinesin-1 and dynein activities at the nuclear envelope during nuclear migration. Dev. Biol. 338:237–250 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson J.G., Allen K.M., Fox J.W., Lamperti E.D., Berkovic S., Scheffer I., Cooper E.C., Dobyns W.B., Minnerath S.R., Ross M.E., Walsh C.A. 1998. Doublecortin, a brain-specific gene mutated in human X-linked lissencephaly and double cortex syndrome, encodes a putative signaling protein. Cell. 92:63–72 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80899-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godin J.D., Humbert S. 2011. Mitotic spindle: focus on the function of huntingtin. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 43:852–856 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godin J.D., Colombo K., Molina-Calavita M., Keryer G., Zala D., Charrin B.C., Dietrich P., Volvert M.L., Guillemot F., Dragatsis I., et al. 2010. Huntingtin is required for mitotic spindle orientation and mammalian neurogenesis. Neuron. 67:392–406 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.06.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gönczy P., Bellanger J.M., Kirkham M., Pozniakowski A., Baumer K., Phillips J.B., Hyman A.A. 2001. zyg-8, a gene required for spindle positioning in C. elegans, encodes a doublecortin-related kinase that promotes microtubule assembly. Dev. Cell. 1:363–375 10.1016/S1534-5807(01)00046-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green R.A., Kaplan K.B. 2003. Chromosome instability in colorectal tumor cells is associated with defects in microtubule plus-end attachments caused by a dominant mutation in APC. J. Cell Biol. 163:949–961 10.1083/jcb.200307070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber R., Zhou Z., Sukchev M., Joerss T., Frappart P.O., Wang Z.Q. 2011. MCPH1 regulates the neuroprogenitor division mode by coupling the centrosomal cycle with mitotic entry through the Chk1-Cdc25 pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 13:1325–1334 10.1038/ncb2342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guernsey D.L., Jiang H., Hussin J., Arnold M., Bouyakdan K., Perry S., Babineau-Sturk T., Beis J., Dumas N., Evans S.C., et al. 2010. Mutations in centrosomal protein CEP152 in primary microcephaly families linked to MCPH4. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 87:40–51 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunawardena S., Her L.S., Brusch R.G., Laymon R.A., Niesman I.R., Gordesky-Gold B., Sintasath L., Bonini N.M., Goldstein L.S. 2003. Disruption of axonal transport by loss of huntingtin or expression of pathogenic polyQ proteins in Drosophila. Neuron. 40:25–40 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00594-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D., Weinberg R.A. 2000. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 100:57–70 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81683-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen D.V., Lui J.H., Parker P.R., Kriegstein A.R. 2010. Neurogenic radial glia in the outer subventricular zone of human neocortex. Nature. 464:554–561 10.1038/nature08845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada N., Tamai Y., Ishikawa T., Sauer B., Takaku K., Oshima M., Taketo M.M. 1999. Intestinal polyposis in mice with a dominant stable mutation of the beta-catenin gene. EMBO J. 18:5931–5942 10.1093/emboj/18.21.5931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haydar T.F., Ang E., Jr, Rakic P. 2003. Mitotic spindle rotation and mode of cell division in the developing telencephalon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:2890–2895 10.1073/pnas.0437969100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hergovich A., Lisztwan J., Barry R., Ballschmieter P., Krek W. 2003. Regulation of microtubule stability by the von Hippel-Lindau tumour suppressor protein pVHL. Nat. Cell Biol. 5:64–70 10.1038/ncb899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J., Midgley C., Bergh A.M., Bell S.M., Askham J.M., Roberts E., Binns R.K., Sharif S.M., Bennett C., Glover D.M., et al. 2010. Human ASPM participates in spindle organisation, spindle orientation and cytokinesis. BMC Cell Biol. 11:85 10.1186/1471-2121-11-85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander M.C., Blumenthal G.M., Dennis P.A. 2011. PTEN loss in the continuum of common cancers, rare syndromes and mouse models. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 11:289–301 10.1038/nrc3037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu T. 2012. Complex cellular functions of the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene: insights from model organisms. Oncogene. 31:2247–2257 10.1038/onc.2011.442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Roberts A.J., Leschziner A.E., Reck-Peterson S.L. 2012. Lis1 acts as a “clutch” between the ATPase and microtubule-binding domains of the dynein motor. Cell. 150:975–986 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttner W.B., Brand M. 1997. Asymmetric division and polarity of neuroepithelial cells. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 7:29–39 10.1016/S0959-4388(97)80117-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A.P., Eastwood H., Bell S.M., Adu J., Toomes C., Carr I.M., Roberts E., Hampshire D.J., Crow Y.J., Mighell A.J., et al. 2002. Identification of microcephalin, a protein implicated in determining the size of the human brain. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 71:136–142 10.1086/341283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin W.G., Jr 2008. The von Hippel-Lindau tumour suppressor protein: O2 sensing and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 8:865–873 10.1038/nrc2502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalay E., Yigit G., Aslan Y., Brown K.E., Pohl E., Bicknell L.S., Kayserili H., Li Y., Tüysüz B., Nürnberg G., et al. 2011. CEP152 is a genome maintenance protein disrupted in Seckel syndrome. Nat. Genet. 43:23–26 10.1038/ng.725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan K.B., Burds A.A., Swedlow J.R., Bekir S.S., Sorger P.K., Näthke I.S. 2001. A role for the Adenomatous Polyposis Coli protein in chromosome segregation. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:429–432 10.1038/35070123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka N., Diem M.D., Kim V.N., Yong J., Dreyfuss G. 2001. Magoh, a human homolog of Drosophila mago nashi protein, is a component of the splicing-dependent exon-exon junction complex. EMBO J. 20:6424–6433 10.1093/emboj/20.22.6424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa D., Kohlmaier G., Keller D., Strnad P., Balestra F.R., Flückiger I., Gönczy P. 2011. Spindle positioning in human cells relies on proper centriole formation and on the microcephaly proteins CPAP and STIL. J. Cell Sci. 124:3884–3893 10.1242/jcs.089888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolano A., Brunet S., Silk A.D., Cleveland D.W., Verlhac M.H. 2012. Error-prone mammalian female meiosis from silencing the spindle assembly checkpoint without normal interkinetochore tension. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 109:E1858–E1867 10.1073/pnas.1204686109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konno D., Shioi G., Shitamukai A., Mori A., Kiyonari H., Miyata T., Matsuzaki F. 2008. Neuroepithelial progenitors undergo LGN-dependent planar divisions to maintain self-renewability during mammalian neurogenesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 10:93–101 10.1038/ncb1673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosodo Y., Röper K., Haubensak W., Marzesco A.M., Corbeil D., Huttner W.B. 2004. Asymmetric distribution of the apical plasma membrane during neurogenic divisions of mammalian neuroepithelial cells. EMBO J. 23:2314–2324 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosodo Y., Toida K., Dubreuil V., Alexandre P., Schenk J., Kiyokage E., Attardo A., Mora-Bermúdez F., Arii T., Clarke J.D., Huttner W.B. 2008. Cytokinesis of neuroepithelial cells can divide their basal process before anaphase. EMBO J. 27:3151–3163 10.1038/emboj.2008.227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouprina N., Pavlicek A., Collins N.K., Nakano M., Noskov V.N., Ohzeki J., Mochida G.H., Risinger J.I., Goldsmith P., Gunsior M., et al. 2005. The microcephaly ASPM gene is expressed in proliferating tissues and encodes for a mitotic spindle protein. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14:2155–2165 10.1093/hmg/ddi220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Girimaji S.C., Duvvari M.R., Blanton S.H. 2009. Mutations in STIL, encoding a pericentriolar and centrosomal protein, cause primary microcephaly. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 84:286–290 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Hir H., Andersen G.R. 2008. Structural insights into the exon junction complex. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 18:112–119 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechler T., Fuchs E. 2005. Asymmetric cell divisions promote stratification and differentiation of mammalian skin. Nature. 437:275–280 10.1038/nature03922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leidel S., Gönczy P. 2005. Centrosome duplication and nematodes: recent insights from an old relationship. Dev. Cell. 9:317–325 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesage B., Gutierrez I., Martí E., Gonzalez C. 2010. Neural stem cells: the need for a proper orientation. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 20:438–442 10.1016/j.gde.2010.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Boswell R., Wood W.B. 2000. mag-1, a homolog of Drosophila mago nashi, regulates hermaphrodite germ-line sex determination in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 218:172–182 10.1006/dbio.1999.9593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S.Y., Pan H.W., Liu S.H., Jeng Y.M., Hu F.C., Peng S.Y., Lai P.L., Hsu H.C. 2008. ASPM is a novel marker for vascular invasion, early recurrence, and poor prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 14:4814–4820 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lizarraga S.B., Margossian S.P., Harris M.H., Campagna D.R., Han A.P., Blevins S., Mudbhary R., Barker J.E., Walsh C.A., Fleming M.D. 2010. Cdk5rap2 regulates centrosome function and chromosome segregation in neuronal progenitors. Development. 137:1907–1917 10.1242/dev.040410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Nigro C., Chong C.S., Smith A.C., Dobyns W.B., Carrozzo R., Ledbetter D.H. 1997. Point mutations and an intragenic deletion in LIS1, the lissencephaly causative gene in isolated lissencephaly sequence and Miller-Dieker syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 6:157–164 10.1093/hmg/6.2.157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo N.A., Shimono Y., Qian D., Clarke M.F. 2007. The biology of cancer stem cells. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 23:675–699 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löffler H., Fechter A., Matuszewska M., Saffrich R., Mistrik M., Marhold J., Hornung C., Westermann F., Bartek J., Krämer A. 2011. Cep63 recruits Cdk1 to the centrosome: implications for regulation of mitotic entry, centrosome amplification, and genome maintenance. Cancer Res. 71:2129–2139 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorson M.A., Horvitz H.R., van den Heuvel S. 2000. LIN-5 is a novel component of the spindle apparatus required for chromosome segregation and cleavage plane specification in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Cell Biol. 148:73–86 10.1083/jcb.148.1.73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee J.A., Piskounova E., Morrison S.J. 2012. Cancer stem cells: impact, heterogeneity, and uncertainty. Cancer Cell. 21:283–296 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister S.S., Weinberg R.A. 2010. Tumor-host interactions: a far-reaching relationship. J. Clin. Oncol. 28:4022–4028 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.4257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCartney B.M., Näthke I.S. 2008. Cell regulation by the Apc protein Apc as master regulator of epithelia. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 20:186–193 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCartney B.M., McEwen D.G., Grevengoed E., Maddox P., Bejsovec A., Peifer M. 2001. Drosophila APC2 and Armadillo participate in tethering mitotic spindles to cortical actin. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:933–938 10.1038/ncb1001-933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenney R.J., Vershinin M., Kunwar A., Vallee R.B., Gross S.P. 2010. LIS1 and NudE induce a persistent dynein force-producing state. Cell. 141:304–314 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megraw T.L., Sharkey J.T., Nowakowski R.S. 2011. Cdk5rap2 exposes the centrosomal root of microcephaly syndromes. Trends Cell Biol. 21:470–480 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minde D.P., Anvarian Z., Rüdiger S.G., Maurice M.M. 2011. Messing up disorder: how do missense mutations in the tumor suppressor protein APC lead to cancer? Mol. Cancer. 10:101 10.1186/1476-4598-10-101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizumoto K., Sawa H. 2007. Two betas or not two betas: regulation of asymmetric division by beta-catenin. Trends Cell Biol. 17:465–473 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin X., Bellaïche Y. 2011. Mitotic spindle orientation in asymmetric and symmetric cell divisions during animal development. Dev. Cell. 21:102–119 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison S.J., Kimble J. 2006. Asymmetric and symmetric stem-cell divisions in development and cancer. Nature. 441:1068–1074 10.1038/nature04956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Näthke I. 2006. Cytoskeleton out of the cupboard: colon cancer and cytoskeletal changes induced by loss of APC. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 6:967–974 10.1038/nrc2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas A.K., Khurshid M., Désir J., Carvalho O.P., Cox J.J., Thornton G., Kausar R., Ansar M., Ahmad W., Verloes A., et al. 2010. WDR62 is associated with the spindle pole and is mutated in human microcephaly. Nat. Genet. 42:1010–1014 10.1038/ng.682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noctor S.C., Martínez-Cerdeño V., Kriegstein A.R. 2008. Distinct behaviors of neural stem and progenitor cells underlie cortical neurogenesis. J. Comp. Neurol. 508:28–44 10.1002/cne.21669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogg S., Ruvkun G. 1998. The C. elegans PTEN homolog, DAF-18, acts in the insulin receptor-like metabolic signaling pathway. Mol. Cell. 2:887–893 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80303-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacios I.M. 2002. RNA processing: splicing and the cytoplasmic localisation of mRNA. Curr. Biol. 12:R50–R52 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00671-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pease J.C., Tirnauer J.S. 2011. Mitotic spindle misorientation in cancer—out of alignment and into the fire. J. Cell Sci. 124:1007–1016 10.1242/jcs.081406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyre E., Morin X. 2012. An oblique view on the role of spindle orientation in vertebrate neurogenesis. Dev. Growth Differ. 54:287–305 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2012.01350.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postiglione M.P., Jüschke C., Xie Y., Haas G.A., Charalambous C., Knoblich J.A. 2011. Mouse inscuteable induces apical-basal spindle orientation to facilitate intermediate progenitor generation in the developing neocortex. Neuron. 72:269–284 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pramparo T., Youn Y.H., Yingling J., Hirotsune S., Wynshaw-Boris A. 2010. Novel embryonic neuronal migration and proliferation defects in Dcx mutant mice are exacerbated by Lis1 reduction. J. Neurosci. 30:3002–3012 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4851-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulvers J.N., Bryk J., Fish J.L., Wilsch-Bräuninger M., Arai Y., Schreier D., Naumann R., Helppi J., Habermann B., Vogt J., et al. 2010. Mutations in mouse Aspm (abnormal spindle-like microcephaly associated) cause not only microcephaly but also major defects in the germline. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107:16595–16600 10.1073/pnas.1010494107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quyn A.J., Appleton P.L., Carey F.A., Steele R.J., Barker N., Clevers H., Ridgway R.A., Sansom O.J., Näthke I.S. 2010. Spindle orientation bias in gut epithelial stem cell compartments is lost in precancerous tissue. Cell Stem Cell. 6:175–181 10.1016/j.stem.2009.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radulescu A.E., Cleveland D.W. 2010. NuMA after 30 years: the matrix revisited. Trends Cell Biol. 20:214–222 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner O., Carrozzo R., Shen Y., Wehnert M., Faustinella F., Dobyns W.B., Caskey C.T., Ledbetter D.H. 1993. Isolation of a Miller-Dieker lissencephaly gene containing G protein beta-subunit-like repeats. Nature. 364:717–721 10.1038/364717a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reya T., Clevers H. 2005. Wnt signalling in stem cells and cancer. Nature. 434:843–850 10.1038/nature03319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusan N.M., Akong K., Peifer M. 2008. Putting the model to the test: are APC proteins essential for neuronal polarity, axon outgrowth, and axon targeting? J. Cell Biol. 183:203–212 10.1083/jcb.200807079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanada K., Tsai L.H. 2005. G protein betagamma subunits and AGS3 control spindle orientation and asymmetric cell fate of cerebral cortical progenitors. Cell. 122:119–131 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders R.D., Avides M.C., Howard T., Gonzalez C., Glover D.M. 1997. The Drosophila gene abnormal spindle encodes a novel microtubule-associated protein that associates with the polar regions of the mitotic spindle. J. Cell Biol. 137:881–890 10.1083/jcb.137.4.881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubart U.K., Yu J., Amat J.A., Wang Z., Hoffmann M.K., Edelmann W. 1996. Normal development of mice lacking metablastin (P19), a phosphoprotein implicated in cell cycle regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 271:14062–14066 10.1074/jbc.271.24.14062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shitamukai A., Matsuzaki F. 2012. Control of asymmetric cell division of mammalian neural progenitors. Dev. Growth Differ. 54:277–286 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2012.01345.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumyatsky G.P., Malleret G., Shin R.M., Takizawa S., Tully K., Tsvetkov E., Zakharenko S.S., Joseph J., Vronskaya S., Yin D., et al. 2005. stathmin, a gene enriched in the amygdala, controls both learned and innate fear. Cell. 123:697–709 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siller K.H., Doe C.Q. 2008. Lis1/dynactin regulates metaphase spindle orientation in Drosophila neuroblasts. Dev. Biol. 319:1–9 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.03.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siller K.H., Doe C.Q. 2009. Spindle orientation during asymmetric cell division. Nat. Cell Biol. 11:365–374 10.1038/ncb0409-365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver D.L., Watkins-Chow D.E., Schreck K.C., Pierfelice T.J., Larson D.M., Burnetti A.J., Liaw H.J., Myung K., Walsh C.A., Gaiano N., Pavan W.J. 2010. The exon junction complex component Magoh controls brain size by regulating neural stem cell division. Nat. Neurosci. 13:551–558 10.1038/nn.2527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sir J.H., Barr A.R., Nicholas A.K., Carvalho O.P., Khurshid M., Sossick A., Reichelt S., D’Santos C., Woods C.G., Gergely F. 2011. A primary microcephaly protein complex forms a ring around parental centrioles. Nat. Genet. 43:1147–1153 10.1038/ng.971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitohy B., Nagy J.A., Dvorak H.F. 2012. Anti-VEGF/VEGFR therapy for cancer: reassessing the target. Cancer Res. 72:1909–1914 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D.S., Niethammer M., Ayala R., Zhou Y., Gambello M.J., Wynshaw-Boris A., Tsai L.H. 2000. Regulation of cytoplasmic dynein behaviour and microtubule organization by mammalian Lis1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:767–775 10.1038/35041000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith E., Dejsuphong D., Balestrini A., Hampel M., Lenz C., Takeda S., Vindigni A., Costanzo V. 2009. An ATM- and ATR-dependent checkpoint inactivates spindle assembly by targeting CEP63. Nat. Cell Biol. 11:278–285 10.1038/ncb1835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snippert H.J., van der Flier L.G., Sato T., van Es J.H., van den Born M., Kroon-Veenboer C., Barker N., Klein A.M., van Rheenen J., Simons B.D., Clevers H. 2010. Intestinal crypt homeostasis results from neutral competition between symmetrically dividing Lgr5 stem cells. Cell. 143:134–144 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan D.G., Fisk R.M., Xu H., van den Heuvel S. 2003. A complex of LIN-5 and GPR proteins regulates G protein signaling and spindle function in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 17:1225–1239 10.1101/gad.1081203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker H., Hafen E. 2000. Genetic control of cell size. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 10:529–535 10.1016/S0959-437X(00)00123-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su L.K., Burrell M., Hill D.E., Gyuris J., Brent R., Wiltshire R., Trent J., Vogelstein B., Kinzler K.W. 1995. APC binds to the novel protein EB1. Cancer Res. 55:2972–2977 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiarto S., Persson A.I., Munoz E.G., Waldhuber M., Lamagna C., Andor N., Hanecker P., Ayers-Ringler J., Phillips J., Siu J., et al. 2011. Asymmetry-defective oligodendrocyte progenitors are glioma precursors. Cancer Cell. 20:328–340 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan A., Nguyen T., Suter B. 1999. Drosophila Lissencephaly-1 functions with Bic-D and dynein in oocyte determination and nuclear positioning. Nat. Cell Biol. 1:444–449 10.1038/15680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarsitano M., De Falco S., Colonna V., McGhee J.D., Persico M.G. 2006. The C. elegans pvf-1 gene encodes a PDGF/VEGF-like factor able to bind mammalian VEGF receptors and to induce angiogenesis. FASEB J. 20:227–233 10.1096/fj.05-4147com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Huntington’s Disease Collaborative Research Group 1993. A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington’s disease chromosomes. Cell. 72:971–983 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90585-E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoma C.R., Frew I.J., Hoerner C.R., Montani M., Moch H., Krek W. 2007. pVHL and GSK3beta are components of a primary cilium-maintenance signalling network. Nat. Cell Biol. 9:588–595 10.1038/ncb1579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoma C.R., Toso A., Gutbrodt K.L., Reggi S.P., Frew I.J., Schraml P., Hergovich A., Moch H., Meraldi P., Krek W. 2009. VHL loss causes spindle misorientation and chromosome instability. Nat. Cell Biol. 11:994–1001 10.1038/ncb1912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton G.K., Woods C.G. 2009. Primary microcephaly: do all roads lead to Rome? Trends Genet. 25:501–510 10.1016/j.tig.2009.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tighe A., Johnson V.L., Taylor S.S. 2004. Truncating APC mutations have dominant effects on proliferation, spindle checkpoint control, survival and chromosome stability. J. Cell Sci. 117:6339–6353 10.1242/jcs.01556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoshima F., Matsumura S., Morimoto H., Mitsushima M., Nishida E. 2007. PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 regulates spindle orientation in adherent cells. Dev. Cell. 13:796–811 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Voet M., Berends C.W., Perreault A., Nguyen-Ngoc T., Gönczy P., Vidal M., Boxem M., van den Heuvel S. 2009. NuMA-related LIN-5, ASPM-1, calmodulin and dynein promote meiotic spindle rotation independently of cortical LIN-5/GPR/Galpha. Nat. Cell Biol. 11:269–277 10.1038/ncb1834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varmark H. 2004. Functional role of centrosomes in spindle assembly and organization. J. Cell. Biochem. 91:904–914 10.1002/jcb.20013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Stein W., Ramrath A., Grimm A., Müller-Borg M., Wodarz A. 2005. Direct association of Bazooka/PAR-3 with the lipid phosphatase PTEN reveals a link between the PAR/aPKC complex and phosphoinositide signaling. Development. 132:1675–1686 10.1242/dev.01720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wainman A., Creque J., Williams B., Williams E.V., Bonaccorsi S., Gatti M., Goldberg M.L. 2009. Roles of the Drosophila NudE protein in kinetochore function and centrosome migration. J. Cell Sci. 122:1747–1758 10.1242/jcs.041798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh T., Shahin H., Elkan-Miller T., Lee M.K., Thornton A.M., Roeb W., Abu Rayyan A., Loulus S., Avraham K.B., King M.C., Kanaan M. 2010. Whole exome sequencing and homozygosity mapping identify mutation in the cell polarity protein GPSM2 as the cause of nonsyndromic hearing loss DFNB82. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 87:90–94 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Li S., Januschke J., Rossi F., Izumi Y., Garcia-Alvarez G., Gwee S.S., Soon S.B., Sidhu H.K., Yu F., et al. 2011. An ana2/ctp/mud complex regulates spindle orientation in Drosophila neuroblasts. Dev. Cell. 21:520–533 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver B.A., Cleveland D.W. 2009. The role of aneuploidy in promoting and suppressing tumors. J. Cell Biol. 185:935–937 10.1083/jcb.200905098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells R.A., Catzavelos C., Kamel-Reid S. 1997. Fusion of retinoic acid receptor alpha to NuMA, the nuclear mitotic apparatus protein, by a variant translocation in acute promyelocytic leukaemia. Nat. Genet. 17:109–113 10.1038/ng0997-109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams S.E., Beronja S., Pasolli H.A., Fuchs E. 2011. Asymmetric cell divisions promote Notch-dependent epidermal differentiation. Nature. 470:353–358 10.1038/nature09793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynshaw-Boris A., Pramparo T., Youn Y.H., Hirotsune S. 2010. Lissencephaly: mechanistic insights from animal models and potential therapeutic strategies. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 21:823–830 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita Y.M., Jones D.L., Fuller M.T. 2003. Orientation of asymmetric stem cell division by the APC tumor suppressor and centrosome. Science. 301:1547–1550 10.1126/science.1087795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yingling J., Youn Y.H., Darling D., Toyo-Oka K., Pramparo T., Hirotsune S., Wynshaw-Boris A. 2008. Neuroepithelial stem cell proliferation requires LIS1 for precise spindle orientation and symmetric division. Cell. 132:474–486 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu T.W., Mochida G.H., Tischfield D.J., Sgaier S.K., Flores-Sarnat L., Sergi C.M., Topçu M., McDonald M.T., Barry B.J., Felie J.M., et al. 2010. Mutations in WDR62, encoding a centrosome-associated protein, cause microcephaly with simplified gyri and abnormal cortical architecture. Nat. Genet. 42:1015–1020 10.1038/ng.683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Z., Zhu H., Wan Q., Liu J., Xiao Z., Siderovski D.P., Du Q. 2010. LGN regulates mitotic spindle orientation during epithelial morphogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 189:275–288 10.1083/jcb.200910021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]