Abstract

Background

To assess the covariates of alcohol abuse and the association between alcohol abuse, high-risk sexual behaviors and sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Methods

2,019 women aged 20–44 were randomly selected in a two-stage sampling from the Moshi urban district of northern Tanzania. Participant’s demographic and socio-economic characteristics, alcohol use, sexual behaviors and STIs were assessed. Blood and urine samples were drawn for testing of human immunodeficiency virus, herpes simplex virus, syphilis, chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomonas and mycoplasma genitalium infections.

Results

Adjusted analyses showed that a history of physical (OR=2.05; 95% CI: 1.06–3.98) and sexual violence (OR=1.63; 95% CI: 1.05–2.51) was associated with alcohol abuse. Moreover, alcohol abuse was associated with number of sexual partners (OR=1.66; 95% CI: 1.01–2.73). Women who abused alcohol were more likely to report STIs symptoms (OR=1.61; 95% CI: 1.08–2.40). Women who had multiple sexual partners were more likely to have an STI (OR=2.41; 95% CI: 1.46–4.00) compared to women with one sexual partner. There was no direct association between alcohol abuse and prevalence of STIs (OR=0.86; 95% CI: 0.55–1.34). However, alcohol abuse was indirectly associated with STIs through its association with multiple sexual partners.

Conclusions

The findings of alcohol abuse among physically and sexually violated women as well as the association between alcohol abuse and a history of symptoms of STIs and testing positive for STIs have significant public health implications. In sub-Saharan Africa, where women are disproportionately affected by the HIV epidemic screening for alcohol use should be part of comprehensive STIs and HIV prevention programs.

Keywords: Alcohol abuse, High-risk sexual behaviors, STIs, sub-Saharan Africa

Introduction

Alcohol consumption may strengthen a sense of invulnerability, reduce perceived importance of social norms, diminish awareness of high risk behaviors, and confound the drinker’s ability to negotiate interpersonal situations or interactions with the environment 1, 2. Several studies have suggested a link between alcohol use and the incidence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), particularly human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) 3–5. Alcohol is the commonest form of substance abuse in sub-Saharan Africa 6, 7. Most studies from the region looked at the association between alcohol use before sex and HIV acquisition in specific at risk populations, results of which may not be applicable to the general population 8–10. Women are disproportionately affected by the HIV epidemic in Africa. However, the association between alcohol use and acquisition and transmission of STIs has been understudied among women in the general population.

STIs facilitate the sexual acquisition and transmission of HIV infection 11. Cross-sectional studies in HIV infected individuals have demonstrated that bacterial STIs (e.g. gonorrhea and chlamydia), trichomonas and vulvovaginal candidiasis are associated with higher HIV viral loads in genital secretions, and successful treatment of these STIs may reduce the viral load and presumably reduces the risk of HIV transmission 12–15. Herpes simplex virus (HSV-2) infection and other STIs resulting in genital ulcers are linked to the risk of HIV acquisition and transmission 16, 17. In general, trials testing how STIs control facilitates HIV control provide mixed findings 18. The recognition, treatment and prevention of STIs to reduce the risk of HIV transmission should be a public health priority especially in sub-Saharan Africa where antiretroviral therapy may not be readily available. The region lacks adequate healthcare infrastructure to identify and institute control measures to contain STIs of which most are asymptomatic 19. There is a public health need to establish determinants (socio-economic and individual) that can be used as markers for STI-associated risks. Hence, the urgent need to study the association between alcohol use and STIs.

To determine the correlates of alcohol abuse and the association of alcohol abuse with STIs among women in sub-Saharan Africa, we conducted an analysis of data from a community-based survey in the Moshi urban district of northern Tanzania. Previous analyses of the data did not consider the hierarchy of the data and measurements from the same geographic cluster were analyzed as though they were uncorrelated 20. Women within a given cluster shared common characteristics, and their outcomes were unlikely to be truly independent of one another. We used a multi-level mixed effects regression model that deals with correlated data and produces unbiased standard errors.

Materials and Methods

Study Participants

A cross-sectional multilevel study conducted from November 2002 to March 2003 in the Moshi urban district of Tanzania was analyzed. The study participants consisted of 2,019 women who were enrolled in a community-based survey, the Moshi Infertility survey 21. The women were selected to participate in the survey in a two-stage sampling. During the first stage of sampling, a total of 150 clusters were selected from the Moshi urban district, northern Tanzania. In the second stage of sampling, a number of households were randomly selected from each of the 150 clusters. The 2,019 women aged 20–44 who were residents of the households were interviewed. Information was collected on fertility, infertility, family planning, marriage, sexual practices, socio-demographic characteristics, and husband-wife relations including domestic violence and alcohol use. Blood samples were taken to test for HIV, HSV-2, past syphilis and active syphilis infections. Urine samples were tested for chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomonas and mycoplasma genitalium infections.

Study Measures

Explanatory variables

Demographic and socio-economic characteristics including age, education (pre-secondary, secondary and above), has ever had a child (no, yes), cash earning activity (no, yes), husband/partner (no, yes), ethnicity (Chaga, Pare, other), difficulties conceiving (no, yes), and religion (Catholic, Protestant, Muslim/none) were considered. Physical violence (no, yes) and sexual violence (no, yes) were also included. Physical violence was defined as a positive response to one of the following questions: being insulted or sworn at by a partner; being threatened with physical abuse by a partner; or being hit, slapped, kicked or otherwise physically hurt by a partner. One item from the Conflict Tactics Scale 22 and two items from the Abuse Assessment Screen 23 were used to ascertain 12-months and lifetime partner violence. Sexual violence was defined as a positive response to any one of the following questions: being forced to have first time sex, being forced to have sex within your current relationship or outside your current relationship.

Outcome Variables

Alcohol Abuse

Alcohol abuse was measured by the CAGE score 24 which is defined as the sum of ‘yes’ answers to the following four questions: (1) Have you ever felt you should cut down on drinking?, (2) Have people annoyed you by criticizing your drinking?, (3) Have you ever felt bad or guiltily about your drinking?, and (4) Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning to steady your nerves or to get rid of a hangover? The CAGE score ranged from 0 to 4. Alcohol abuse was defined as a CAGE score of 2–4 and alcohol non-abuse as a CAGE score of 0–1.

Sexual Behaviors

Participants reported the number of sexual partners they had in the last three years (1, 2+) and frequency of condom use in the last 12 months (never, sometimes, and always/often).

Symptoms of STIs

The women were asked if they had the following symptoms at the time of the interview: abdominal pain, abnormal genital discharge, foul smell in the genital area, excessive genital secretions, swelling of lymphnodes in the genital area, itching in the genital area, burning pain on micturition, pain during intercourse, and genital ulcers. An STI symptom was defined as a positive response to any of the above questions.

Testing for STIs

HIV infection was determined using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Vironostika HIV Uni-Form II plus O, Organon, Boxtel, the Netherlands) and reactive samples were confirmed using a second ELISA (Murex 1.2.0, Murex Biotech Ltd, England, UK). Indeterminate results were resolved by Western blot (Genetic Systems HIV-1 Western blot, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Redmond, WA, USA). Antibodies to HSV-2 were detected using the type-specific HSV-2 enzyme immune assay (EIA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (HerpeSelect 2 ELISA, Focus Technologies, Cypress, CA). Blood samples that reacted on the Treponema pallidum hemagglutination (TPHA) test reflected past syphilis and samples that reacted on both TPHA and rapid plasma reagin (RPR) tests reflected active syphilis. Urine samples were tested for chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomonas and mycoplasma genitalium by using a real-time multiplex polymerase chain reaction (M-PCR) assay. The primers, probe and PCR cycling parameters used have been described previously 25.

Statistical Analysis

Pearson’s Chi-square test was used to determine if there was an association between alcohol abuse and demographic and socio-economic measures. Two-level mixed effects regression models, with women nested within clusters were used in assessing the predictors of alcohol abuse and the impact of alcohol abuse on high-risk sexual behaviors and STIs. More specifically, two-level mixed effects logistic and proportional odds regression models were used to assess the predictors of alcohol abuse and the risks associated with alcohol abuse. Random intercepts were included in the logistic and proportional odds regression models to model the combined effect of all unobserved cluster-specific covariates. The analysis was conducted using a generalized linear mixed models procedure in SAS (version 9.0), i.e., PROC GLIMMIX 26. PROC GLIMMIX does not require geographic clusters to have the same number of participants or measurements, and uses all available data instead of eliminating geographic clusters with missing data, resulting in unbiased estimates of the model parameters when data are missing at random. The employed analytic approach has advantages over traditional methods of multilevel analysis, e.g., it is unaffected by randomly missing data, makes use of all available data, and takes into account the correlation between subjects from the same geographic cluster. Detailed discussions on the advantages of mixed models have been reported by Gueorguieva et al 27.

Results

Characteristics of the study participants

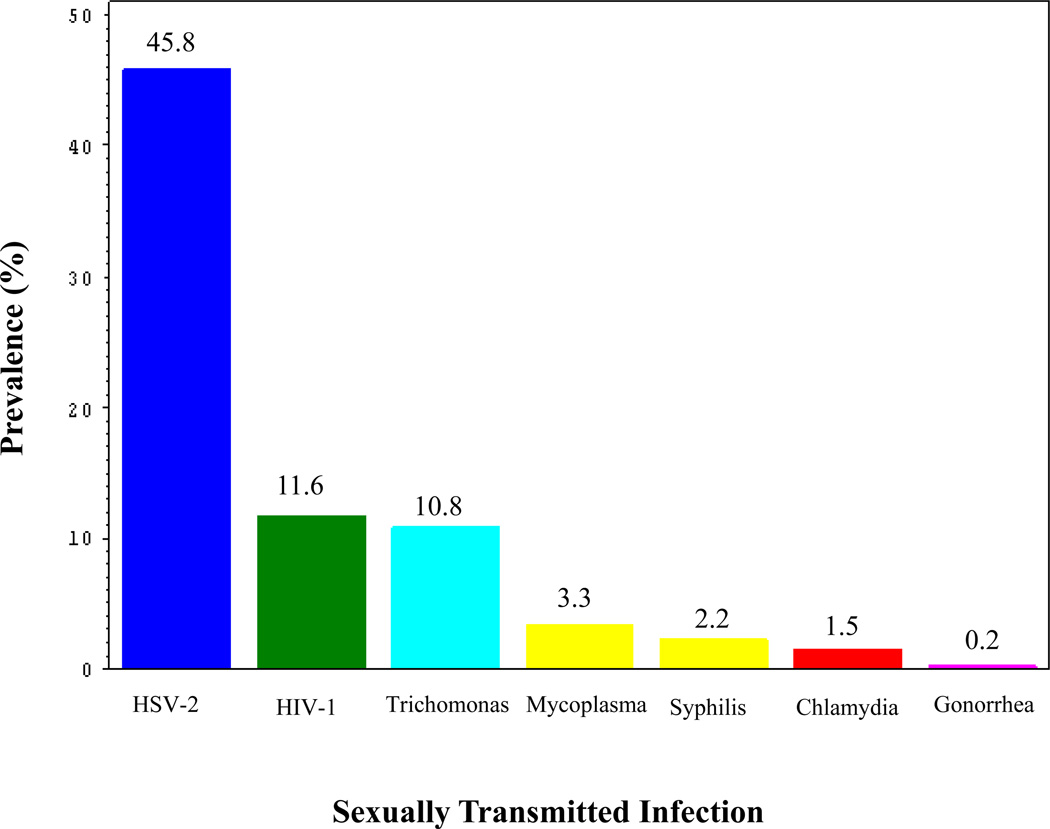

Among the 2,019 women recruited into the study 1,418 women (70.2 %) consented to have blood drawn for testing of HIV, HSV-2, past syphilis and active syphilis infections. As many as 1,440 women provided urine samples for testing of chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomonas and mycoplasma genitalium infections. 1,841 women (91.2 %) answered the questions on STI symptoms, and 1 out of 4 women reported having symptoms of STIs. A half of the tested women had at least one STI, while 14% had more than one STI. The most prevalent STI among the study participants was HSV-2 reaching 45.8% followed by an HIV infection rate of 11.6%. The prevalence rates for other STIs were; trichomonas (10.8%), mycoplasma genitalium (3.3%), syphilis (2.2%), chlamydia (1.5%) and gonorrhea (0.2%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections among women tested for STIs in Moshi, Tanzania, 2002–2003. The data used in the bar graph were derived from tests (described in the methods section) performed on blood and urine samples from 1,418 and 1,440 women, respectively.

Nine hundred and seventy-seven of the women interviewed provided complete information on alcohol use. The CAGE score was used to stratify these women into two groups (alcohol abuse, alcohol non-abuse). Tables 1 and 2 show the characteristics of study participants and distribution of the study outcomes according to their alcohol use status. Fifteen percent had CAGE scores between 2 and 4, and were classified as alcohol abusers. The majority of study participants, regardless of their drinking status, were from the Chagga tribe, were Catholic, had pre-secondary education (76% of participants), had never used a condom in the prior 12 months, had one sex partner in the last three years and had a husband/partner. The prevalence of alcohol abuse was the same across all ages. More than 50% of the alcohol abusers had one or more STIs. Alcohol abuse was more prevalent among women with a history of two or more partners in the last three years, physical and sexual violence. Women who reported difficulties conceiving and women who reported symptoms of one or more STIs were likely to abuse alcohol.

Table 1.

Characteristics of women study participants by alcohol abuse in Moshi, Tanzania, 2002–2003.

| Variable |

Alcohol non-abuse (N=836) |

Alcohol abuse (N=141) |

P-valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Age | 0.80 | ||||

| 20–24 | 182 | 85 | 32 | 15 | |

| 25–29 | 221 | 84 | 42 | 16 | |

| 30–34 | 177 | 86 | 28 | 14 | |

| 35–44 | 256 | 87 | 39 | 13 | |

| Education | 0.73 | ||||

| Pre-secondary | 623 | 85 | 107 | 15 | |

| Secondary and above | 213 | 86 | 34 | 14 | |

| Had a child | 0.07 | ||||

| No | 106 | 80 | 26 | 20 | |

| Yes | 729 | 86 | 115 | 14 | |

| Cash earning activity | 0.76 | ||||

| No | 251 | 85 | 44 | 15 | |

| Yes | 581 | 86 | 96 | 14 | |

| Husband/partner | 0.34 | ||||

| No | 303 | 84 | 57 | 16 | |

| Yes | 533 | 86 | 84 | 14 | |

| Ethnicity | 0.67 | ||||

| Chagga | 533 | 86 | 85 | 13 | |

| Pare | 82 | 85 | 14 | 15 | |

| Other | 220 | 84 | 42 | 16 | |

| Difficulties conceiving | 0.08 | ||||

| No | 751 | 86 | 120 | 14 | |

| Yes | 83 | 80 | 21 | 20 | |

| Religion | 0.14 | ||||

| Muslim/other | 174 | 84 | 32 | 16 | |

| Catholic | 450 | 88 | 64 | 12 | |

| Protestant | 211 | 82 | 45 | 18 | |

| Physical violence | 0.05 | ||||

| No | 592 | 86 | 97 | 14 | |

| Yes | 46 | 77 | 14 | 23 | |

| Sexual violence | 0.05 | ||||

| No | 589 | 87 | 88 | 13 | |

| Yes | 247 | 82 | 53 | 18 | |

Based on Pearson’s Chi-square test

Table 2.

Distribution of study outcomes by alcohol abuse in Moshi, Tanzania, 2002–2003.

| Variable |

Alcohol non-abuse (N=836) |

Alcohol abuse (N=141) |

P-valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Condom use in the last 12 months | 0.47 | ||||

| Never | 562 | 86 | 94 | 14 | |

| Sometime | 145 | 85 | 25 | 15 | |

| Often/always | 52 | 80 | 13 | 20 | |

| Number of sexual partners in the last 3 years | 0.04 | ||||

| 1 | 669 | 86 | 108 | 14 | |

| 2+ | 97 | 79 | 26 | 21 | |

| STIs symptoms | 0.01 | ||||

| No | 625 | 87 | 91 | 13 | |

| Yes | 211 | 81 | 50 | 19 | |

| STIs | 0.81 | ||||

| No | 276 | 84 | 52 | 16 | |

| Yes | 362 | 85 | 65 | 15 | |

Based on Pearson’s Chi-square test

Correlates of alcohol abuse

We assessed whether a participants’ characteristics were associated with alcohol abuse. All the variables that were associated with alcohol abuse at the 0.20 level and others that were taught to be important correlates of alcohol abuse were included in the analysis of alcohol. Three characteristics, history of physical violence, sexual violence and difficulties conceiving had statistically significant associations with alcohol abuse (Table 3). In adjusted models women were more likely to abuse alcohol, if they had experienced physical violence (OR=2.05; 95% CI: 1.06–3.98) or sexual violence (OR=1.63; 95% CI: 1.05–2.51). Women who reported difficulties conceiving were more likely to abuse alcohol (OR=1.87; 95% CI: 1.02–3.43).

Table 3.

Predictors of women’s alcohol abuse in Moshi, Tanzania, 2002–2003.

| Predictors | Unadjusted Odds Ratios | Adjusted Odds Ratios | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Had a child | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 0.64(0.40–1.03) | 0.07 | 0.68(0.37–1.26) | 0.21 |

| Husband/Partner | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 0.84 (0.58–1.20) | 0.33 | 0.62 (0.37–1.04) | 0.06 |

| Difficulties conceiving | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.58(0.94–2.65) | 0.08 | 1.87(1.02–3.43) | 0.04 |

| Religion | ||||

| Muslim/other | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Catholic | 0.77(0.49–1.22) | 0.27 | 0.79(0.46–1.35) | 0.38 |

| Protestant | 1.16(0.71–1.91) | 0.56 | 1.14(0.64–2.04) | 0.65 |

| Physical violence | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.86(1.00–3.51) | 0.05 | 2.05(1.06–3.98) | 0.03 |

| Sexual violence | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.44(1.01–2.09) | 0.05 | 1.63(1.05–2.51) | 0.02 |

Effects of alcohol abuse on high-risk sexual behaviors and STIs

It has been suggested that alcohol consumption increases risk-taking behaviors and the risk of acquiring an STI. To investigate this association, we fitted several two-level mixed models with alcohol use as independent variable and condom use, number of sexual partners, symptoms of STIs and STIs as dependent variables. Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios were similar and adjusted findings were reported (Table 4). There was no statistically significant difference in the frequency of condom use between alcohol abusers and non-abusers (OR=0.85; 95% CI: 0.56–1.28). However, alcohol abuse was significantly associated with the number of sexual partners in the last three years and symptoms of STIs. Women who abused alcohol were more likely to have had more than one sexual partner in the previous three years (OR=1.66; 95% CI: 1.01–2.73), and alcohol abuse was associated with symptoms of STIs (OR=1.61; 95% CI=1.08–2.40). There was no statistically significant association between testing positive for an STI and alcohol abuse (OR=0.86; 95%, CI 0.55–1.34). Number of sexual partners in the previous three years was significantly associated with STIs (OR=2.41; 95% CI: 1.46–4.00). Thus, alcohol abuse was indirectly associated with testing positive for an STI through the number of sexual partners of a woman.

Table 4.

Effects of women’s alcohol abuse on condom use, number of sexual partners, STIs symptoms and STIs in Moshi, Tanzania, 2002–2003.

| Dependent variable | Unadjusted Odds Ratios | Adjusted Odds Ratiosa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |

|

Model-I: Condom use in the last 12 months |

||||

| Alcohol abuse | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 0.85 (0.56–1.28) | 0.42 | 0.85 (0.56–1.28) | 0.43 |

|

Model-II: Number of sexual partners in the last 3 years |

||||

| Alcohol abuse | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.66 (1.02–2.70) | 0.04 | 1.66 (1.01–2.73) | 0.04 |

| Model-III: STIs Symptoms | ||||

| Alcohol abuse | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.62 (1.10–2.40) | 0.02 | 1.61 (1.08–2.40) | 0.02 |

| Model-IV: STIs | ||||

| Alcohol abuse | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 0.97 (0.64–1.46) | 0.88 | 0.86 (0.55–1.34) | 0.51 |

| Number of sexual partners | ||||

| 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 2+ | 1.95 (1.33–2.84) | <0.01 | 2.41 (1.46–4.00) | <0.01 |

The odds ratios were adjusted for the effects of age, ethnicity, religion, and education.

Discussion

We found that physical violence, sexual violence and difficulties conceiving were associated with alcohol abuse. Furthermore, alcohol abuse was directly associated with STIs symptoms, and indirectly associated with testing positive for STIs through its association with multiple sexual partners. This is one of the first population-based studies in sub-Saharan Africa designed at assessing problem drinking in women with regards to STIs-associated risks. Most studies have looked at STIs in association with alcohol use prior to sex10; we did not investigate alcohol use prior to sex.

About 15% of the study participants were considered to be alcohol abusers using the CAGE score. This finding is consistent with previous reports from the sub-region 7, 9, 28. Seventy six percent of the alcohol abusers had only pre-secondary education. Are these women using alcohol as self-medication for an underlying problem? The affirmative answer to this question could be deduced based on the significant association between alcohol abuse and a history of intimate partner violence (physical and sexual violence) and having multiple partners. Moreover, women with difficulties conceiving were more likely to resort to alcohol abuse (p=0.04) in adjusted models (Table 3).

In most sub-Saharan African countries, women are accorded a subordinate status and this may affect their abilities to negotiate sexual decisions and behaviors and their risk of STIs 29, 30. Women are expected to be faithful and even condone their partners engagement in multiple partnerships and sexual risk behaviors 30. It is plausible that societal expectations and pressures put upon women by their partners result in alcohol use and abuse as an escape. Alcohol use may reduce women’s inhibition and the use of alcohol may help women refrain from protesting and condone with the sexual risk behaviors of their partners. The findings in this study are consistent with earlier studies that found significant associations between sexual risk behaviors and alcohol consumption in female partners 9, 28 and contrast a study in Uganda where no relation was established 31. In sum, male perpetrators of intimate partner violence may engage in sexual risk behaviors putting their female partners at greater risk of acquiring an STI/HIV, especially those who resort to alcohol use.

Alcohol abuse had a direct association with having STIs symptoms and was indirectly associated with testing positive for an STI through its association with multiple sexual partners. This finding suggests that multiple sexual partners may be in the pathway of alcohol abuse and STIs. This finding is consistent with the association between alcohol use and STI/HIV previously reported 10. Although the association between alcohol and HIV is not clear, it has been suggested that alcohol enhances in vitro susceptibility of human peripheral mononuclear cells to HIV infection and the replication of virus in HIV-infected individuals 32, 33. Furthermore, reduced inhibition from alcohol use may result in sexual risk-taking behaviors associated with STIs 8, 34. Hence, screening for alcohol use in women in sub-Saharan African may be a useful surrogate for predicting intimate partner violence (physical and sexual violence) and an individual’s risk of acquiring STIs/HIV.

Alcohol abuse was significantly associated with number of sexual partners. Stable and monogamous relationships were associated with a reduced risk of alcohol abuse, although the association was not significant. This finding is consistent with previous studies from the sub-region 9, 35. We found no significant association between alcohol use and ethnicity, religion or education. The most prevalent STIs among study participants were HSV-2 reaching 45.8% followed by the infection rates of 11.6% for HIV and 10.8% for trichomonas, while the remaining STIs studied had prevalence rates below 5.0%. The STIs prevalence rates found in the study population are high and consistent with other studies in the region 36, 37. Most STIs prevalence data are based on selected populations attending gynecological and family planning clinics. The similarity between the population based rates in this study and rates in high risk groups, such as bar and hotel workers, is of concern.

HSV-2 and other STIs, particularly those causing genital ulcerations, are known to facilitate HIV acquisition and transmission. The high prevalence rate (45.8%) of HSV-2 is of concern as it can further fuel the HIV epidemic. Moreover, we observed a rather low prevalence of condom use in the last 12 months among study participants. At the time of the study HIV awareness and prevalence in the community were low and that may partly explain the rather low condom use. Preferably, the study should have analyzed data about life time use of condoms, but that information was not collected. There is a need for comprehensive community-based STIs prevention programs in Moshi, as well as throughout sub-Saharan Africa.

This study has several strengths compared to previous studies. It has a large sample size. Moreover, the data on STIs come from both biological samples and self-reports. However, it has inherent limitations associated with population-based studies. First, only women who provided information on alcohol use and STIs were included in the analysis. Analysis of the complete cases ignores the possible systematic difference between the women who provided information on these variables (alcohol use, number of sexual partners and symptoms of STIs) and those who did not. Thus, inferences from complete cases can be biased if there were a systematic difference between cases with observed data and those with unobserved data. For example, if subjects who provided urine samples were more likely to report symptoms consistent with STIs, this might have led to overestimation of the population prevalence. The reported sexual behaviors might have been affected by social desirability bias. For instance, in most sub-Saharan African cultures women are not permitted to have multiple partners; the number of partners reported by study participants could be an underestimation. Moreover, the analysis is based on a cross-sectional data, which limits the conclusions that can be drawn with regards to causality between alcohol abuse, sexual risk factors and STIs.

In conclusion, we found an association between physical violence, sexual violence, difficulties conceiving and alcohol abuse. There was a direct relationship between alcohol abuse, number of sexual partners and STIs symptoms and an indirect relationship between alcohol abuse and testing positive for an STI. These findings have significant public health implications. In sub-Saharan Africa, where women are disproportionately affected by the HIV epidemic, screening for alcohol use should be part of comprehensive STIs and HIV prevention programs.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by grants from NIH/NICHD R01 HD41202, NIH/NIDA 5 U01-DA017387-03S1 and Harvard University Center for AIDS Research (HU CFAR NIH/NAIDS P30-AI 060354). We thank the women of Moshi urban district of Tanzania for their participation.

References

- 1.Giesbrecht N, Dick R. Societal norms and risk-taking behaviour: inter-cultural comparisons of casualties and alcohol consumption. Addiction. 1993;88:867–876. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oei TP, Kerschbaumer DM. Peer attitudes sex, the effects of alcohol on simulated driving performance. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1990;16:135–146. doi: 10.3109/00952999009001578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Standerwick K, Davies C, Tucker L, Sheron N. Binge drinking, sexual behaviour and sexually transmitted infection in the UK. Int J STD AIDS. 2007;18:810–813. doi: 10.1258/095646207782717027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher JC, Cook PA, Sam NE, Kapiga SH. Patterns of alcohol use, problem drinking, and HIV infection among high-risk African women. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:537–544. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181677547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chersich MF, Luchters SM, Malonza IM, Mwarogo P, King'ola N, Temmerman M. Heavy episodic drinking among Kenyan female sex workers is associated with unsafe sex, sexual violence and sexually transmitted infections. Int J STD AIDS. 2007;18:764–769. doi: 10.1258/095646207782212342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Obot IS. The measurement of drinking patterns and alcohol problems in Nigeria. J Subst Abuse. 2000;12:169–181. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parry CD, Bhana A, Myers B, et al. Alcohol use in South Africa: findings from the South African Community Epidemiology Network on Drug use (SACENDU) Project. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63:430–435. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mbulaiteye SM, Ruberantwari A, Nakiyingi JS, Carpenter LM, Kamali A, Whitworth JA. Alcohol and HIV: a study among sexually active adults in rural southwest Uganda. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:911–915. doi: 10.1093/ije/29.5.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiser SD, Leiter K, Heisler M, et al. A population-based study on alcohol and high-risk sexual behaviors in Botswana. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e392. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zablotska IB, Gray RH, Serwadda D, et al. Alcohol use before sex and HIV acquisition: a longitudinal study in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS. 2006;20:1191–1196. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000226960.25589.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wasserheit JN. Epidemiological synergy. Interrelationships between human immunodeficiency virus infection and other sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Transm Dis. 1992;19:61–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen MS, Hoffman IF, Royce RA, et al. Reduction of concentration of HIV-1 in semen after treatment of urethritis: implications for prevention of sexual transmission of HIV-1. AIDSCAP Malawi Research Group. Lancet. 1997;349:1868–1873. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)02190-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coombs RW, Reichelderfer PS, Landay AL. Recent observations on HIV type-1 infection in the genital tract of men and women. AIDS. 2003;17:455–480. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200303070-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McClelland RS, Lavreys L, Katingima C, et al. Contribution of HIV-1 infection to acquisition of sexually transmitted disease: a 10-year prospective study. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:333–338. doi: 10.1086/427262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watts DH, Springer G, Minkoff H, et al. The Occurrence of Vaginal Infections Among HIV-Infected and High-Risk HIV-Uninfected Women: Longitudinal Findings of the Women's Interagency HIV Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:161–168. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000242448.90026.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wald A, Link K. Risk of human immunodeficiency virus infection in herpes simplex virus type 2-seropositive persons: a meta-analysis. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:45–52. doi: 10.1086/338231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wawer MJ, Gray RH, Sewankambo NK, et al. Rates of HIV-1 transmission per coital act, by stage of HIV-1 infection, in Rakai, Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1403–1409. doi: 10.1086/429411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Consultation on STD Interventions for Preventing HIV: What is the Evidence? UNAIDS Best Practice Collection.Reference Number: WHO/HSI/2000.02. ( www.who.int/entity/hiv/pub/sti/pubevidence/en/index.html).

- 19.Wilkinson D, Abdool Karim SS, Harrison A, et al. Unrecognized sexually transmitted infections in rural South African women: a hidden epidemic. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77:22–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kapiga SH, Sam NE, Bang H, et al. The role of herpes simplex virus type 2 and other genital infections in the acquisition of HIV-1 among high-risk women in northern Tanzania. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1260–1269. doi: 10.1086/513566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larsen U, Mlay J, Aboud S, et al. Design of a community-based study of sexually transmitted infections/HIV and infertility in an urban area of northern Tanzania. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:20–24. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000218878.29220.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Straus MA, Douglas EM. A short form of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales, and typologies for severity and mutuality. Violence Vict. 2004;19:507–520. doi: 10.1891/vivi.19.5.507.63686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McFarlane J, Parker B, Soeken K, Bullock L. Assessing for abuse during pregnancy. Severity and frequency of injuries and associated entry into prenatal care. JAMA. 1992;267:3176–3178. doi: 10.1001/jama.267.23.3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayfield D, McLeod G, Hall P. The CAGE questionnaire: validation of a new alcoholism screening instrument. Am J Psychiatry. 1974;131:1121–1123. doi: 10.1176/ajp.131.10.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klinger EV, Kapiga SH, Sam NE, et al. A Community-based study of risk factors for Trichomonas vaginalis infection among women and their male partners in Moshi urban district, northern Tanzania. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33:712–718. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000222667.42207.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schabenberger O. Introducing the GLIMMIX procedure for generalized linear models. SUGI 30. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gueorguieva R, Krystal JH. Move over ANOVA: progress in analyzing repeated-measures data and its reflection in papers published in the Archives of General Psychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:310–317. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simbayi LC, Kalichman SC, Jooste S, Mathiti V, Cain D, Cherry C. Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV infection among men and women receiving sexually transmitted infection clinic services in Cape Town, South Africa. J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65:434–442. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolff B, Blanc AK, Ssekamatte-Ssebuliba J. The role of couple negotiation in unmet need for contraception and the decision to stop childbearing in Uganda. Stud Fam Plann. 2000;31:124–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2000.00124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koenig MA, Lutalo T, Zhao F, et al. Domestic violence in rural Uganda: evidence from a community-based study. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81:53–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koenig MA, Zablotska I, Lutalo T, Nalugoda F, Wagman J, Gray R. Coerced first intercourse and reproductive health among adolescent women in Rakai, Uganda. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2004;30:156–163. doi: 10.1363/3015604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bagasra O, Kajdacsy-Balla A, Lischner HW, Pomerantz RJ. Alcohol intake increases human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:789–797. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.4.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balla AK, Lischner HW, Pomerantz RJ, Bagasra O. Human studies on alcohol and susceptibility to HIV infection. Alcohol. 1994;11:99–103. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(94)90050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karamagi CA, Tumwine JK, Tylleskar T, Heggenhougen K. Intimate partner violence against women in eastern Uganda: implications for HIV prevention. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:284. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Brown HC, Gray GE, McIntryre JA, Harlow SD. Gender-based violence, relationship power, and risk of HIV infection in women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. Lancet. 2004;363:1415–1421. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Killewo JZ, Sandstrom A, Bredberg Raden U, Mhalu FS, Biberfeld G, Wall S. Prevalence and incidence of syphilis and its association with HIV-1 infection in a population-based study in the Kagera region of Tanzania. Int J STD AIDS. 1994;5:424–431. doi: 10.1177/095646249400500609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kamali A, Nunn AJ, Mulder DW, Van Dyck E, Dobbins JG, Whitworth JA. Seroprevalence and incidence of genital ulcer infections in a rural Ugandan population. Sex Transm Infect. 1999;75:98–102. doi: 10.1136/sti.75.2.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]