Abstract

Herein we report the topochemical modification of polymer surfaces with perfluorinated aromatic azides. The aryl azides, which have quaternary amine or aldehyde functional groups, were linked to the surface of the polymer by UV irradiation. The polymer substrates used in this study were cyclic olefin copolymer (COC) and poly(methylmethacrylate) (PMMA). These substrates were characterized before and after modification, using reflection-absorption infrared spectroscopy (RAIRS), sessile water contact angle measurements, and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). Analysis of the surface confirmed the presence of an aromatic groups with aldehyde or quaternary amine functionality. Enzyme immobilization and patterning onto polymer surfaces were studied using confocal microscopy. Enzymatic digests were carried out on modified probes manufactured from thermoplastic substrates and the resulting peptide analysis was completed using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry (MALDI-MS).

Introduction

In recent years, there has been a demand for miniaturizing chemical analysis systems through use of microfluidics and microarrays. The microfluidic-based devices have specific advantages such as high throughput analysis due to rapid separations, reduced costs and the ability to integrate multiple components on a single platform.1 These advantages have enabled the use of microfluidic-based devices in the detection of terrorist weapons2 and clinical analyses.3

The two substrates commonly used in microfluidics are glass and polymers. Glass substrates have been used due to their optical properties and ease of surface modification. However, polymer microchips are becoming more important due to their reduced cost, ease of fabrication and the availability of diverse functional groups amenable to modification.4–7 Various polymers are readily available, which has led to a number of ways by which the surface can be modified and tailored to specific chemical analysis.

A key requirement in fabricating functional miniaturized devices is the ability to chemically modify the device surface to improve adhesion,8 enhance electrophoretic separation,9 immobilize biological molecules10, 11 and control electroosmotic flow (EOF).4 Chemical and biochemical modifications to the channel surfaces of bio-microelectromechanical systems (BioMEMS) devices for biological research are essential for integrating sample cleaning, purification, pre-concentration, protein enzymatic digestion, and solid phase extraction onto the BioMEMS device. While the surface chemistry of glass substrates is now well-known,12 a similar understanding and technical ability to modify polymers, in particular the thermoplastics used in microfluidics such as PMMA, is less developed.6 Recently, those in the microfluidic field have began to adapt synthetic schemes developed by organic chemists to produce more integrated BioMEMS.

The polymer devices are modified by forming new dynamic, static or covalent bonds on the polymer surface. Dynamic coatings involve adding small molecules or a polymeric material, which are adsorbed physically to the channel wall.13A drawback of dynamic coatings is their limited lifetime; after sufficient usage, these coatings can be depleted from the channel surface. Additionally, when proteins adhere to the channel walls, they can lead to fluctuations or a reduction in the inherent EOF of the separation device.14 Initially, dynamic coatings were used due to their simplicity; however modifications that form covalent bonds between the polymer surface and a functional group are becoming more popular as technical difficulties associated with this approach are being resolved. 15, 16Formation of covalent bonds with the polymer surface generally involve derivatizations of a specific functional group of a particular polymer; however, these functionalities are difficult to control spatially.5

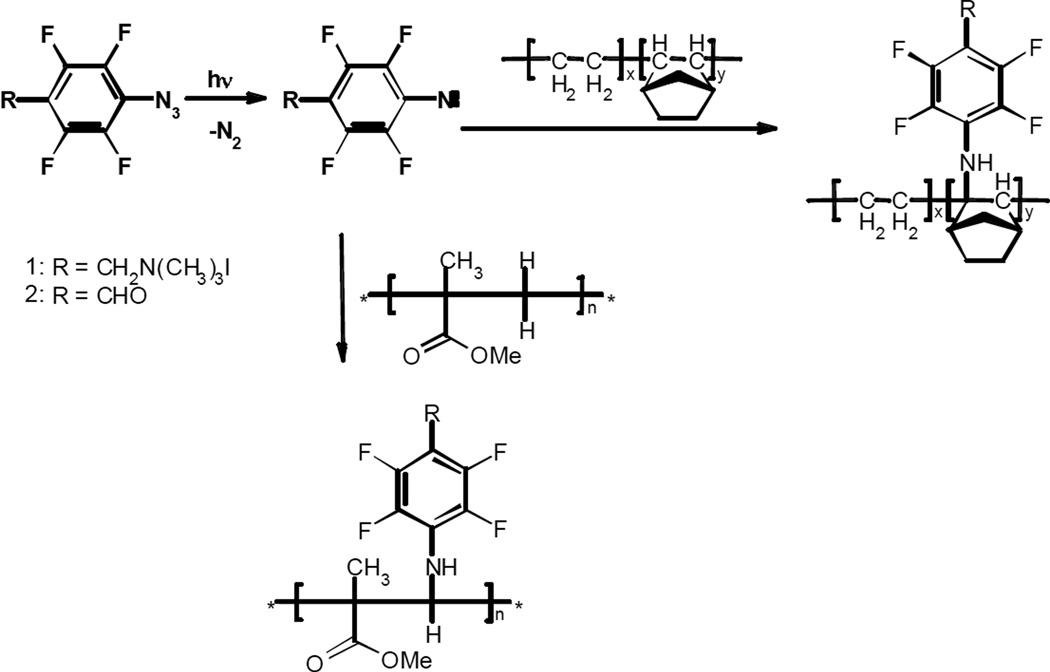

Azido compounds have been used in photografting and cross-linking polymers17–25 and biological species,26 photoaffinity labeling biological compounds27 and modifying carbon surfaces and monolayers.28 Photolysis or thermal activation of azido aryl and ester compounds can lead to formation of the singlet nitrene intermediates by loss of an N2 molecule. Singlet nitrenes are highly reactive intermediates that can insert into surrounding molecules. Depending on the substituents on the aryl azides 29–37 and their concentration,38, 39 reaction solvent,34–36, 40 and temperature,35 singlet aryl nitrenes can rearrange to form azirines, undergo intersystem crossing to form triplet aryl nitrenes, or insert into nearby C-H and C-C bonds.29, 30 Aryl azides with fluorine substituents in both the ortho positions of the benzene have been shown to selectively form singlet nitrene intermediates that will not rearrange to form azirines but rather undergo bimolecular reactions.41–47 Thus, perfluoro-substituted aryl azides can be used to modify plastic surfaces and functionalize polymeric microfabricated devices. In this work perfluorinated aryl azides 1 and 2 (Scheme 1) were specifically used because irradiating leads to the corresponding singlet perfluoroaryl nitrenes, which will insert into neighboring C=C and C-H bonds. However, at higher concentration, the singlet nitrenes will also react with their azido precursors. Scheme 1 depicts the expected insertion of a singlet perfluoroaryl nitrene into cyclic olefin copolymer (COC) and poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA), although the singlet nitrenes can insert into any of the C-H bonds of the polymers.

Scheme 1.

Possible modifications of COC and PMMA surfaces with singlet aryl nitrenes.

There are a number of advantages for immobilizing biological molecules, specifically proteins, onto microfluidic devices and arrays. Most recently, researchers have been investigating immobilizing proteins for immunoassays for recent terrorist biological threats such as ricin, viscumin and anthrax.48Immobilization of enzymes has been shown useful when combined with mass spectrometry, specifically matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI), for on-chip digestion and high-throughput proteomics.49Often dubbed Protein Chips, this enabling technology allows for evaluation of markers for pharmaceuticals, functional analysis of proteins (protein profiling),50 and biomolecular interaction analysis (protein-protein interactions).51There have been a number of methods52 developed to immobilize biological molecules including chemical derivatization methods that yield aldehyde moieties by which the molecules can be covalently linked.53We used aryl azides with an aldehyde functional group to make site-specific attachment of biological molecules or patterned scaffolding to the microfluidic network possible. Additionally, we used aryl azides with quaternary amine moieties to place a permanent positive charge on the surface of thermoplastic substrates. These specific aryl azides are enabling steps in the development of microfluidic devices with improved control of electroosmotic flow (EOF), whose most important parameter is the net charge on the surface of the channel walls.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis and characterization of azides

The two azides used in this study, 4-azido-2,3,5,6-tetrafluoro-benzyl trimethyl-ammonium iodide salt (azide 1) and 4-azidotetrafluorobenzaldehyde (azide 2) were synthesized and characterized as described in the supporting information.

Polymer modification via aryl azides

Polymer sheets in various thicknesses, obtained from Goodfellow, had two protective films (blue and clear). The films were removed and sheets were cut or machined to the appropriate size. Sheets were thoroughly rinsed or soaked in copious amounts of 2-propanol, sonicated in 50:50 methanol/water for approximately 15 minutes and then dried under a steady stream of house nitrogen. Azide 1 or azide 2 was diluted to various concentrations (0.1–10% w/v) in methanol or water. The solutions were placed dropwise on the polymer. Depending on the application, a steady stream of house nitrogen was used to dry the solutions or they were left standing for photolysis. Photolysis was carried out by placing the polymer substrates, with and without azide, in a custom-built reaction chamber containing a medium pressure, water-cooled, 450 W mercury-vapor lamp housed in a Pyrex immersion well that was cooled with water. The polymer substrates were then exposed to UV irradiation for various time periods (15 min–24 h). If needed, a homemade lithographic mask was used to obtain spatial control during photolysis. It has been previously reported that PMMA will react using quartz filtration (254 nm).7 Control samples, including those not treated with azide but exposed to UV irradiation of various wavelengths, were found to have no change except when irradiated with quartz filtration alone. No changes in control samples at ambient conditions were observed. After photolysis the polymer substrates were washed with copious amounts of 50% methanol/water or 100% nanopure water until no dimerized product could be seen.

Immobilization of enzyme to modified polymer surfaces

MALDI-target probes were machined in-house from COC or PMMA sheets to accommodate ~5 µL of sample. To functionalize the polymer MALDI probe, azide 2 was diluted to a concentration of 0.5% v/v in methanol and 5 µL was placed inside the well by pipette. The solutions were allowed to dry in the dark, followed by irradiation for 1 h. The probes were then washed with copious amounts of 50% methanol. To immobilize trypsin, 5 µL of a reaction mixture containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM sodium chloride and enzyme was placed inside the wells. The enzyme was allowed to react with the functionalized MALDI target for 4 h on ice. The MALDI target was then incubated at 37 °C for 4 h and placed in a 5 °C refrigerator overnight. The following day the supernatant was removed from the MALDI target and the immobilized enzyme was washed three times with 200 µL of 50 mM monobasic sodium phosphate followed by 500 µL of nanopure water.

In a similar fashion, PMMA sheets were first modified with azide 2, then trypsin was immobilized by placing a 3 cm × 3 cm sheet of modified PMMA in a 50 mL beaker containing a 800 µL reaction mixture containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM sodium chloride and 200 µL of enzyme. The mixture was then allowed to sit for 4 h on ice. The sheet was then incubated at 37 °C for 4 h and placed in a 5 °C refrigerator overnight. The following day the sheet was removed and the immobilized enzyme was washed three times with 1 mL of 50 mM monobasic sodium phosphate followed by 1 mL of nanopure water.

Enzymatic Digestions

In-solution digestions of myoglobin with trypsin were performed following standard protocols.54 For on-probe digestions, a 1 mM (prior to alkylation and cysteine reduction protocols) protein solution was injected into the wells of the polymer probe. The probes containing immobilized trypsin and injected myoglobin were then allowed to sit for 4 hours. The protein digests solution was removed and in all cases, before MALDI-MS analysis, the digestion solution was desalted by using the standard protocol for Millipore C18 Zip Tips. For in-solution digests, an ammonium bicarbonate buffer (pH 8.2) was chosen for trypsin.

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) Analysis

PMMA and COC sheets were cleaned and cut to the sample holder dimensions (2 cm × 2 cm). Approximately 20 drops of azide 1 5% (w/v) in water or azide 2 5% (v/v) in methanol was spin coated onto PMMA and COC at 2000 rpm for 60 s. Samples were then subjected to UV irradiation for 2 h. Polymer substrates were then washed with copious amounts of 50% methanol/water or 100% nanopure water and dried under a stream of nitrogen.

The changes in the oxidation state of the specimens at the surface were determined by a Perkin-Elmer model 5300 spectrometer interfaced to an RF reactor. The XPS spectrometer uses Mg Kα radiation (1253.6 eV) operating at 300 W and 15 kV DC. The equipment was calibrated using copper and gold. The instrumental work function was set to yield a value of 84.00 eV for the Au (4f 7/2) line for metallic gold. The values of the Cu lines were set at 932.6 eV± 0.1 and 75.1 eV± 0.1 for Cu 2p 3/2 and Cu 3p 3/2, respectively. XPS survey spectra were collected with a pass energy of 89.45 eV at 0.5 eV/step. High-resolution spectra were obtained using a pass energy of 35.75 eV and 0.05 eV/step. The take-off angle used to collect the XPS data was 45°. The data was acquired using AugerScan 2 software provided by RBD Enterprises. Sample charge data were corrected using 284.6 as the C1s binding energy from adventitious carbon at the samples.

Reflective Absorbance Infrared Spectroscopy (RAIRS) Analysis

RAIRS studies were employed to examine the molecular nature of pristine and azide modified PMMA and COC surfaces. RAIRS was performed using a Nicolet Manga – 760 IR spectrometer. A resolution of 4 cm−1 and 2048 background/sample scans was used for all experiments. The sample gain was adjusted to 8 Hz with a mirror velocity of 0.6329. The aperture was set to 69° and a DTGS KBr detector/beam splitter was used.

A commercial sheet of PMMA was dissolved in dichloromethane to yield a solution with a final concentration of 0.5 mg/mL of PMMA in dichloromethane. Approximately 20 drops of this solution were placed onto a ferroplate slide and was allowed to spin for 60 s at 2200 rpm. The PMMA-coated slide was then inspected by elipsometry and the film thickness was determined to be ~120 nm.

A commercial sheet of COC was dissolved in cyclohexane to yield a solution with a final concentration of 1.5 mg/mL of COC in cyclohexane. Approximately 20 drops of this solution were placed onto the ferroplate slide and was allowed to spin for 30 s at 3000 rpm. The COC-coated slide was then inspected by elipsometry and the film thickness was determined to be ~130 nm.

Approximately 20 drops of azide 1 5% (w/v) in water or azide 2 5% (v/v) in methanol was spin coated onto PMMA and COC ferroplate slides at 2000 rpm for 60 s.

Water Contact Angle Measurements

Sessile drop contact angle measurements were conducted to determine the hydrophilicity of native and modified PMMA and COC polymers. Sessile drop contact angle measurements using 18 MΩ• cm water were performed with a homebuilt contact angle system. The system used an optical black and white camera (APPR) with a light source (Fiber-Lite PL-750). Modified polymer sheets were prepared with azide 1 as described above. Approximately 5 µL of 18 MΩ•cm water was placed on various parts of the surface using a syringe. Contact angle measurements were calculated using FTA 125 (First Ten Angstroms, Portsmouth, VA). The left and right contact angles of the water drops were measured immediately after placement of the water droplet on the PMMA and COC surfaces; it was found in all cases that there was no difference in the left and right contact angles. Each value reported here is the average of at least 5 separate drops of water on a given substrate.

Confocal Microscopy

To investigate the enzyme immobilization by confocal microscopy, the C-terminus of the immobilized enzyme was covalently linked to a fluorescein dye. The dye was attached to the carboxylic acid group of the enzyme, immbolized on the PMMA sheet, by following a reported procedure with modifications.55 Briefly, 33.1 mg (173 µmol) of 1-ethyl-3-[3-(dimethylamino)propyl] carbodiimide (EDC) and 2.5 mg (5.24 µmol) of 5-(aminoacetamido)fluorescein were dissolved in 12 mL of nanopure water that had been made basic by the addition of 2 drops of 10% NaOH solution. This solution was then added to a beaker containing the modified PMMA. The pH of the solution was adjusted to 5.50 by titration with 1.0 M HCl. The beaker containing the above solution and substrate was placed on a shaker table and allowed to shake slowly for 5 h. The reaction was stopped by freezing. The substrate was washed with copious amounts of 2-propanol and then rinsed extensively with nanopure water.

Confocal microscopy was used after attachment of 5-(aminoacetamido)fluorescein. A Zeiss 510 LSM microscope outfitted with an Argon Laser (488 nm excitation) and a Zeiss 20× fluar objective was used in all experiments. Single scans with 1 µm optical slices were used. A control sample was treated with all chemical reactions except for the initial functionalization reaction of the PMMA film.

MALDI-MS

The digestion products from the tryptic and Glu-C digests of myoglobin were analyzed with a Bruker Reflex IV MALDI time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltronics, Billerica, MA). The mass spectrometer was operated in positive ion reflectron mode for analysis of digests and linear mode for the analysis of intact protein.

For protein digestions, α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid, prepared in 60% acetonitrile with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid, was used as the matrix. For all analyses, the enzymatic digests were combined with the appropriate matrix, spotted on the sample plate or probe and allowed to dry. A two-point external and internal mass calibration was used in all cases. The calibrants were chosen from the same chemical class as the analytes, and were bradykinin 1–7 (MW = 756.9) and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) (MW = 2465).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Modification of PMMA and COC with Azide 1

XPS Analysis

XPS was used to confirm that azide 1 had reacted with the surface of native sheet PMMA and COC, by identifying I, F, and N atoms on the surface that can only be present if azide 1 reacts to form covalent bonds with the surface. XPS was also used to determine the extent that azide 1 was grafted onto the PMMA and COC surfaces. The percentage of C, O, N, F, and I atoms on the surface are presented in Table 1 for native PMMA and COC as well as COC and PMMA modified with azide 1.

Table 1.

XPS analysis of PMMA and COC surfaces before and after modification with azide 1.

| Surface | Atomic Concentration (%) | Atomic Ratio Averages | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1s | O1s | N1s | F1s | I3d5 | O1s/C1s | N1s/C1s | F1s/C1s | I3d5/C1s | |

| PMMA | 75.9 | 24.1 | 0.31 ± 0.00 | ||||||

| 76.1 | 23.9 | ||||||||

| 76.2 | 23.8 | ||||||||

| PMMA/azide 1 | 67.3 | 7.0 | 7.9 | 12.2 | 5.6 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 0.07 ± 0.01 |

| 66.3 | 6.6 | 7.8 | 14.3 | 5.0 | |||||

| 69.5 | 6.3 | 6.2 | 13.6 | 4.4 | |||||

| PMMA/azide 1/irradiation | 68.6 | 12.1 | 5.2 | 10.4 | 3.8 | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 0.07 ± 0.00 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.00 |

| 69.9 | 10.9 | 5.0 | 10.3 | 3.9 | |||||

| 69.9 | 9.5 | 5.3 | 11.3 | 4.1 | |||||

| COC | 95.3 | 4.7 | 0.05 ± 0.00 | ||||||

| 95.2 | 4.8 | ||||||||

| 95.0 | 4.5 | ||||||||

| COC/azide 1 | 62.7 | 12.6 | 8.7 | 12.8 | 3.2 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.00 |

| 65.1 | 10.7 | 8.5 | 12.6 | 3.1 | |||||

| 66.0 | 10.7 | 7.7 | 12.4 | 3.2 | |||||

| COC/azide 1/irradiation | 80.4 | 5.1 | 4.5 | 8.5 | 1.5 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.00 | 0.02 ± 0.00 |

| 80.7 | 4.7 | 5.0 | 8.5 | 1.2 | |||||

| 81.5 | 4.9 | 3.9 | 8.6 | 1.2 | |||||

XPS of native PMMA showed two peaks at 537.5 and 288.8 eV, assigned to O1s and C1s, respectively. The ratio of the O1s to C1s is 0.31 ± 0.00, which correlates well with ordered PMMA surface groups.56 After applying azide 1, irradiating and washing, the XPS spectrum of the surface showed additional peaks at 407.1, 695.8, and 625.0 eV, which correspond to N1s, F1s and I3d5, respectively. The ratio of the O1s to C1s in PMMA modified with azide 1 decreased approximately 50% when compared to native PMMA.

From the experimental N/C and F/C atomic ratios of 0.07 and 0.15, respectively, the level of surface functionalization can be calculated considering the following monomer unit:18 (PMMA)x + (NPhF4CH2N(CH3)3I)y or (C5H8O2)x + (C10H11N2F4I)y, where x + y = 1. For an N/C ratio of 0.07, y is 0.21 which corresponding to approximately 21% grafting. Similarly, the F/C ratio of 0.15 corresponds to approximately 23% grafting.

XPS of native COC showed two peaks at 536.2 and 288.3 eV at a ratio of 0.05 ± 0.00, assigned to O1s and C1, respectively. It is not clear why the O1s peak was detected but it is presumably from oxidization of COC in the manufacturing process. Addition of azide 1 to the COC surface decreased the O1s/C1s ratio (Table 2) and additional peaks at 404.1, 692.2, and 622.8 eV assigned to N1s, F1s and I3d5, respectively, were detected. After irradiating and washing the surface, a small increase in ratio of O1s/C1s was observed in comparison with pristine COC, which can be ascribed to the high carbon content in native cyclic COC. Importantly, after irradiating and washing the COC surface, the survey spectrum continued to showed peaks due to the N1s, F1s and I3d5 atoms.

Table 2.

Sessile contact angles and their assignments for PMMA and COC surfaces before and after modification with azide 1 and before and after washing.

| Polymer Substrate | Contact Angle |

|---|---|

| Pristine PMMA | 68 ± 2° |

| PMMA/Photolysis/No Washing | 7 ± 5° |

| PMMA/Photolysis/Washing | 37 ± 3° |

| Pristine COC | 92 ± 2° |

| COC/Photolysis/Washing | 63 ± 3° |

From the experimental N/C and F/C atomic ratios of 0.06 and 0.11, respectively, the level of surface functionalization can be calculated as before for PMMA considering the following COC monomer unit: (COC)x + (NPh(F4)CH2N(CH3)3I)y or (C9H14)x + (C10H11N2F4I)y, where x + y = 1. An N/C ratio of 0.06 (y = 0.27) corresponds to approximately 27% grafting. Similarly, the F/C value of 0.11 corresponds to approximately 25% grafting.

RAIRS Analysis

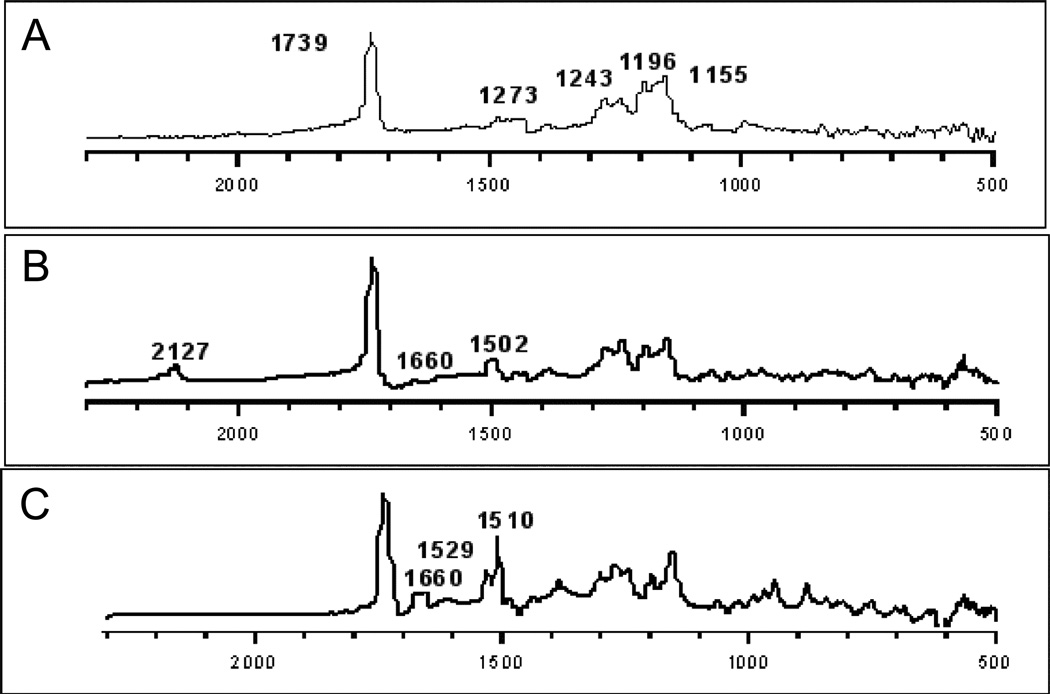

RAIRS was used to examine the photofunctionalization of PMMA and COC with azide 1 and to confirm that covalent bonds had been made to the surfaces of PMMA and COC. In Figure 1 are displayed the RAIRS spectra of native PMMA, and PMMA and azide 1, before and after irradiation. As expected, the spectrum of native PMMA correlates well with its reported transmission spectrum, 57, 58 which has the most prominent band at ~1739 cm−1 due to its carbonyl stretching. RAIRS of PMMA after applying azide 1 to the polymer surface yields major bands at 2127 (N3), 1660 and 1502 (C=C) cm−1. After irradiation, the azido band at 2127 cm−1 is fully depleted whereas the other major C=C bands are detected at 1660, 1529 and 1510 cm−1 (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

RAIR Spectra of (A) PMMA (B) PMMA after applying azide 1, and (C) PMMA after irradiation of azide 1.

Figure 2 depicts the RAIR spectra of native COC, COC and azide 1 before and after irradiation. The spectrum of native COC fits with the reported transmission spectrum of COC,59 with the most prominent bands at 2957 and 2930 cm−1 due to C-H stretching. The major IR bands for azide 1 on the COC surface are located at 2131 (N3), 1659 and 1506 (C=C) cm−1. After irradiating azide 1 on the COC surface the azido band at 2131 cm−1 is fully depleted whereas the C=C stretches shifted to 1662 and 1511 cm−1.

Figure 2.

RAIR Spectra of (A) COC (B) COC after applying azide 1, and (C) COC after irradiation of azide 1. In B and C, the RAIR spectra of COC has been subtracted.

The polymer surfaces were washed extensively after photolysis to remove any products that can be attributed to the nitrene from azide 1 reacting with their precursors. As the aromatic C=C stretches are still present in the RAIR spectra of COC and PMMA surfaces that have been modified with azide 1, whereas the azido band has been fully depleted, it can be assumed that azide 1 has reacted with the polymer surface.

Contact Angle Measurements

Sessile drop water contact angle measurements were done on both native and PMMA and COC surfaces photofunctionalized with azide 1 to measure differences in hydrophobicity between native and modified surfaces (Table 2). The average water contact angle for pristine PMMA was found to be 68 ± 2° (Figure 3A), which correlates well with the literature value of 67° for a highly ordered hydrophobic methyl ester-terminated monolayer.60 Water contact angles were measured as a function of concentrations of azide 1 (0.1%–10%), irradiation time (15 min–24 h) and solvent (methanol or water). Contact angles of unwashed PMMA sheets modified with azide 1 yielded an average value of 7 ± 5° (Figure 3B) for irradiation periods longer than 30 min and did not depend on the concentration range studied and the solvent. Washing the irradiated PMMA surface increased the value of the contact angle as unbound perfluorinated aryl azides that did not react with the polymer surface were removed.

Figure 3.

Sessile drop water contact angle measurements of (A) native PMMA, (B) PMMA after irradiation of azide 1 but before washing (C) PMMA after irradiation of azide 1 followed by washing, (D) native COC and (E) COC after irradiation of azide 1 followed by washing.

The contact angle was found to decrease with increasing irradiation time suggesting a more hydrophilic surface. Likewise, as the concentration of azide 1 was increased from 0.1% to 5%, in either methanol or water, a general decrease was noted in the contact angle in comparison to native PMMA. However, when the concentration of azide 1 was more than 5%, in either methanol or water, the contact angle become more consistent likely due to the competitive pathway of singlet nitrene insertion into azide 1.

With azide 1 at 5% w/v in water, irradiation period of 2 h, and washing the surface with 50% aq. methanol, a contact angle of 37 ± 3° was obtained (Figure 3C). Similar contact angle values have been observed for self-assembled monolayers terminated with hydrophilic functional groups.60 Variances in this value might be due to compensating hydrophobic forces exhibited by the bulky phenyl groups, insufficient iodide counter ion removal or insufficient surface coverage may account for the relatively hydrophobic surface after modification.

The average water contact angle for pristine COC was found to be 92 ± 2° (Figure 3D), which correlates well with the literature value of 91°.61With azide 1 at 5% w/v in water, irradiation period of 2 h, and washing the surface with 50% aq. methanol, a contact angle of 63 ± 3° was obtained (Figure 3E). The net decrease of ~30° in the contact angles in modified COC versus native COC is almost identical to the contact angle decrease noted with modified PMMA.

Modification of PMMA and COC with Azide 2

XPS

XPS was used to confirm that irradiating azide 2 on PMMA and COC surfaces successfully added an aldehyde functional group. The atomic percentages for C1s, O1s, N1s and F1s are presented in Table 3 for native PMMA and COC as well as COC and PMMA modified with azide 2. After irradiation and washing the average ratio of O1s/C1s of PMMA modified with azide 2 showed no net change when compared to native PMMA. This is not unreasonable because azide 2 is rich in C-atoms. However the XPS detected the presence of both N and F atoms, indicating that azide 2 had reacted with the surface.

Table 3.

XPS analysis of PMMA and COC surfaces before and after modification with azide 2.

| Surface | Atomic Concentration (%) | Atomic Ratios (Averages) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1s | O1s | N1s | F1s | O1s/C1s | N1s/C1s | F1s/C1s | |

| PMMA | 75.9 | 24.1 | 0.31 ± 0.00 | ||||

| 76.1 | 23.9 | ||||||

| 76.2 | 23.8 | ||||||

| PMMA/azide 2 | 62.5 | 22.7 | 6.5 | 8.3 | 0.36 ± 0.00 | 0.11 ± 0.00 | 0.13 ± 0.00 |

| 62.6 | 22.3 | 6.7 | 8.4 | ||||

| 62.6 | 22.4 | 6.7 | 8.3 | ||||

| PMMA/azide 2 /irradiation | 72.1 | 24.0 | 1.2 | 2.8 | 0.32 ± 0.01 | 0.020 ± 0.00 | 0.033 ± 0.01 |

| 73.2 | 23.3 | 1.4 | 2.1 | ||||

| 73.1 | 22.8 | 1.7 | 2.4 | ||||

| COC | 95.3 | 4.7 | - | - | 0.05 ± 0.00 | - | - |

| 95.2 | 4.8 | - | - | ||||

| 95.0 | 4.5 | - | - | ||||

| COC/azide 2 | 73.3 | 12.9 | 5.2 | 8.7 | 0.18 ± 0.00 | 0.07 ± 0.00 | 0.12 ± 0.00 |

| 73.1 | 13.0 | 5.3 | 8.6 | ||||

| 73.2 | 12.8 | 5.3 | 8.8 | ||||

| COC/azide 2/irradiation | 92.1 | 4.5 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.010 ± 0.00 | 0.025 ± 0.00 |

| 93.1 | 3.7 | 1.2 | 2.0 | ||||

| 93.4 | 3.1 | 0.9 | 2.6 | ||||

From the experimental N/C and F/C atomic ratios of 0.020 and 0.033, respectively, the level of surface functionalization can be calculated as before: (PMMA)x + (NPh(F4)COH)y or (C5H8O2)x + (C7HONF4)y, where x + y = 1. The N/C ratio of 0.02 corresponds to approximately 10% grafting. Similarly, an F/C atom ratio of 0.033 corresponds to approximately 4% grafting.

As with PMMA, XPS of pristine COC and COC modified with azide 2 did not show significant changes in the atomic concentration average ratio of O1s/C1s of COC. However, XPS of COC modified with azide 2 revealed the presence of N1 and F1 atoms (Table 3).

From the experimental N/C and F/C atomic ratios of 0.010 and 0.025, respectively, the level of surface functionalization can be calculated as before: (COC)x + (NPh(F4)COH)y or (C9H14)x + (C7HONF4)y, where x + y = 1. An N/C value of 0.011 corresponds to approximately 9% grafting and the F/C value of 0.025 corresponds to approximately 7% grafting.

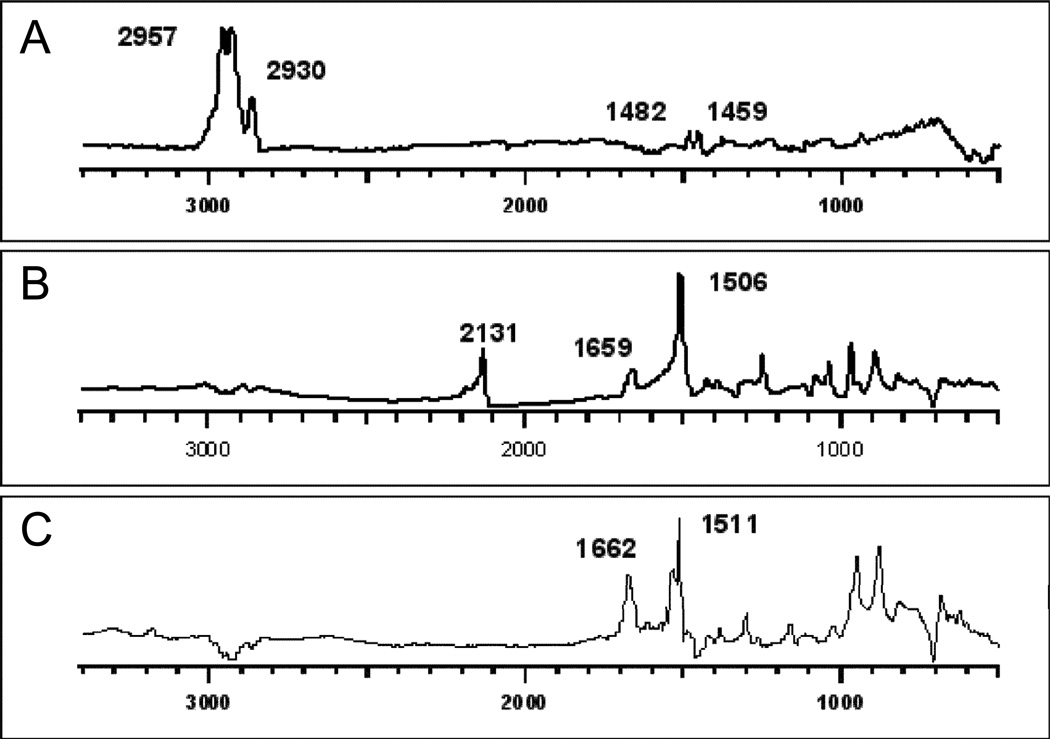

RAIRS

RAIRS was used also to examine the photofunctionalization of PMMA and COC with azide 2 and to confirm that covalent bonds had been made to the surfaces of PMMA and COC. Displayed in Figure 4 are representative RAIRS spectra of PMMA and azide 2, before and after irradiation. RAIRS of PMMA after applying azide 2 to the polymer surface shows the major bands at 2140 (N3), 1712 (C=O) and 1500 (C=C) cm−1. After irradiation and washing the surface the azido band at 2140 is fully depleted whereas the aldehyde band is shifted to 1708 cm−1 and the C=C to 1499 cm−1.

Figure 4.

RAIR Spectra of (A) PMMA (B) PMMA after applying azide 2, and (C) PMMA after irradiation of azide 2 and washing. The spectra in B and C were obtained by subtracting the RAIR spectra of PMMA.

Site-selective Chemical Modification and Enzyme Immobilization

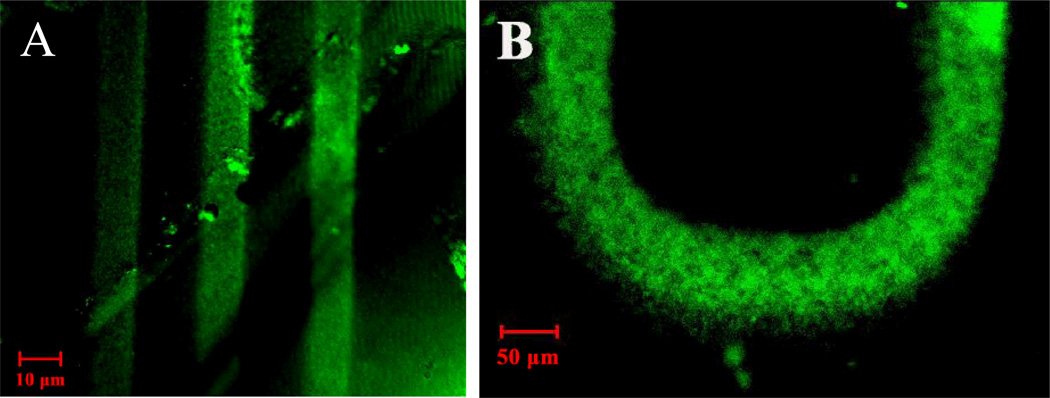

To demonstrate that site-selective chemical modification of thermoplastic microfabricated devices is feasible by grafting azide 2 onto pristine PMMA, a sheet of PMMA was covered with a photolithographic mask, which was used to spatially control the modification of the polymer surface, and then exposed to UV irradiation. To the irradiated PMMA, trypsin was covalently bound to the aldehyde moiety of azide 2. Once trypsin was immobilized, 5-(aminoacetamido)fluorescein dye was attached to the free carboxyl groups of the enzyme. As can be seen in Figure 5, the lithography mask spatially controlled the azide modification of the polymer surface. In addition to the 50 µm width mask, other masks allowing patterning of areas down to as low as 10 µm. The combination of synthetic flexibility with patterned surface modification provides a new route for controlling the surface chemistries feasible on thermoplastic surfaces or within thermoplastic-based microfluidic channels.

Figure 5.

Confocal microscopy images of (A) PMMA after applying azide 2 followed by photolysis with a lithography mask consisting of 10 µm wide spacing, and (B) PMMA after applying azide 2 followed by photolysis with a lithography mask consisting of 50 µm spacing. In both cases trypsin was immobilized to the substrate followed by fluorescent tagging using 5-(aminoacetamido)fluorescein.

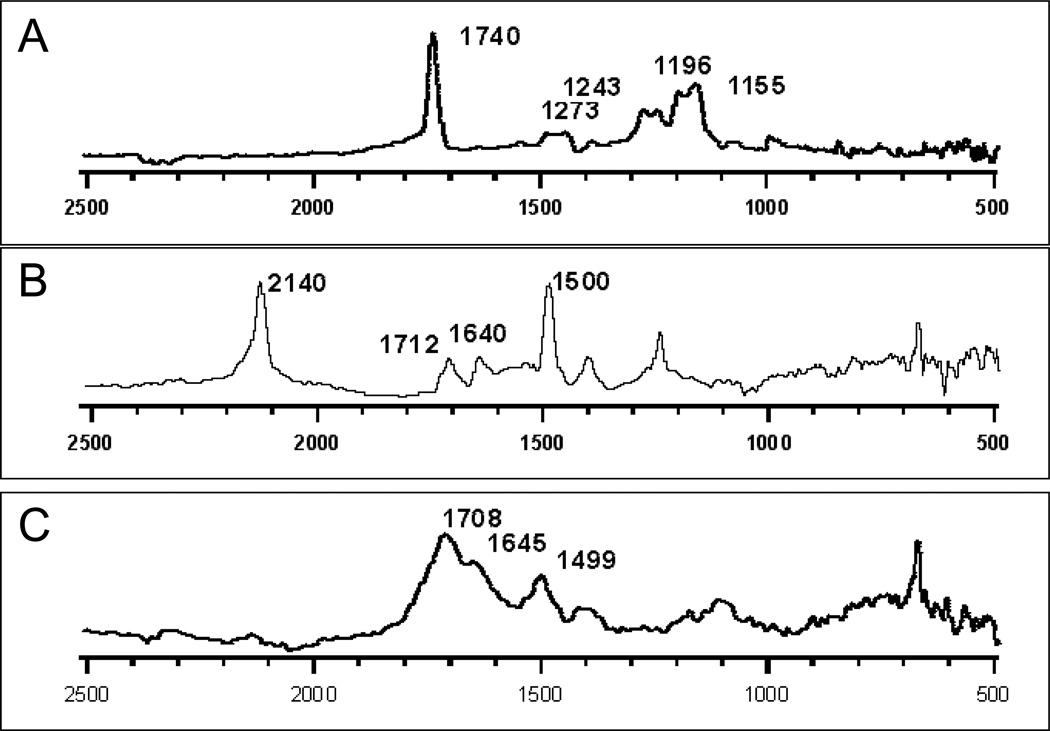

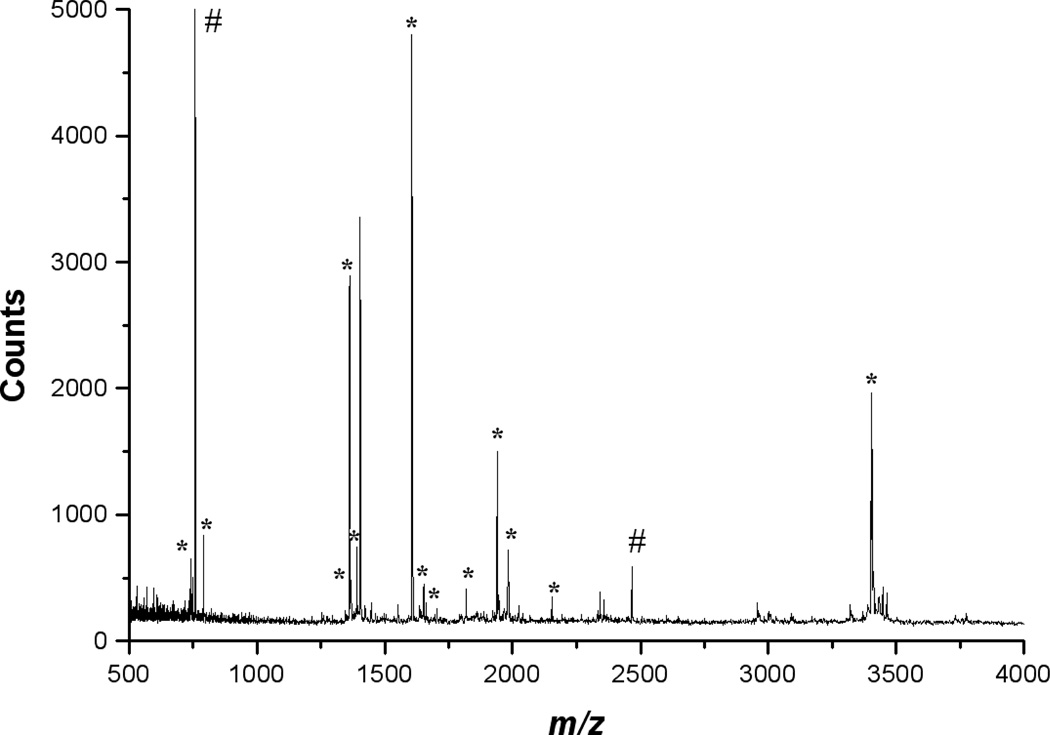

As another demonstration of the analytical utility of the photochemical approach, MALDI target probes fabricated from PMMA and COC were photofunctionalized with azide 2 followed by trypsin immobilization through the available aldehyde group.Figures 6 and S1 illustrate representative MALDI mass spectra from on-probe tryptic digestion of myoglobin. Tables 4 and S1 report the masses of peaks labeled with asterisks (*) along with the corresponding amino acid sequences. These data clearly demonstrate on-probe tryptic digestion using the immobilized enzyme. To characterize the extent of tryptic digestion, MALDI mass spectral data was also obtained at higher m/z to examine for the presence of intact myoglobin (Figure S2). As can be seen in Figure S1, intact myoglobin was not detected, suggesting that an appropriate amount of immobilized trypsin was present on the sample probe. As a control, enzyme immobilization and digestion procedures were carried out in the absence of photochemical modification of the thermoplastics.Figure S2 is a representative MALDI spectrum that was collected in linear mode of a digestion carried out on a non-functionalized PMMA probe. Intact myoglobin was detected, thus non-specific adsorption of trypsin on the MALDI probe does not occur.

Figure 6.

Enzymatic digestion of myoglobin using trypsin immobilized on-probe with PMMA. The peaks identified by * are those which correspond to expected digestion products (see Table 4 for assignments). The peaks marked # correspond to internal standards.

Table 4.

Assigned m/z values from the MALDI-MS analysis of on-probe digested myoglobin after immobilization of trypsin onto PMMA MALDI targets.

| PMMA |

m/z Immobilized |

m/z Theoretical |

Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| X | 748.4 | 748.4 | (K)ALELFR(N) |

| X | 791.4 | 790.4 | (K)ASEDLKK(H) |

| X | 1360.7 | 1360.7 | (K)ALELFRNDIAAK(Y) |

| X | 1366.8 | 1367.6 | (K)TEAEMKASEDLK(K) |

| X | 1606.8 | 1606.8 | (K)VEADIAGHGQEVLIR(L) |

| X | 1635.2 | 1635.0 | (K)HGTVVLTALGGILKKK(G) |

| X | 1651.8 | 1651.9 | (K)ALELFRNDIAAKYK(E) |

| X | 1815.8 | 1815.9 | (−)GLSDGEWQQVLNVWGK(V) |

| X | 1937.9 | 1937.0 | (R)LFTGHPETLEKFDKFK(H) |

| X | 1982.0 | 1982.0 | (K)KGHHEAELKPLAQSHATK(H) |

| X | 2150.2 | 2150.2 | (K)ASEDLKKHGTVVLTALGGILK(K) |

| X | 3403.7 | 3403.7 | (−)GLSDGEWQQVLNVWGKVEADIAGHGQEVLIR(L) |

CONCLUSIONS

These developments illustrate our ability to covalently pattern photoreactive azido groups on polymer surfaces to control and manipulate the surface properties or functionality. The use of functionalized perfluorinated aromatic azides allows for the surface chemistry to be tailored for a specific application. Moreover, the aryl azide approach allows for a universal means by which even chemically inert surfaces of polymeric devices can be covalently modified. These developments will enable further advancements in polymer-based microfluidic and microarray devices in high-throughput (bio)analyses. Current efforts are focused on the derivatization of polymeric microfluidic device by functionalized aryl azides to enhance the EOF characteristics to facilitate efforts to develop thermoplastic microfluidic devices coupled to electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry for pharmaceutical and proteomics applications.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial support of this research was provided by the National Science Foundation (DBI 137924 and CHE 0093622) and the National Institute of Health (GM 69547). The authors thank Basak Bengu, Pablo Rosales, Supa Wirasas, Christina Bennet-Stamper and Dr. Larry Sallans for their assistance with spectral analysis.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Synthetic preparation of azides 1 and 2 and MALDI-mass spectral data. This material is available free at charge at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Khandurina J, Guttman A. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2003;7:595–602. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang J. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2004;507:3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verpoorte E. Electrophoresis. 2002;23:677–712. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200203)23:5<677::AID-ELPS677>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dolnik V. Electrophoresis. 2004;25:3589–3601. doi: 10.1002/elps.200406113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belder D, Ludwig M. Electrophoresis. 2003;24:3595–3606. doi: 10.1002/elps.200305648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker H, Locascio LE. Talanta. 2002;56:267–287. doi: 10.1016/s0039-9140(01)00594-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wei S, Vaidya B, Patel AB, Soper SA, McCarley RL. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005;109:16988–16996. doi: 10.1021/jp051550s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rossier J, Reymond F, Michel P. Electrophoresis. 2002;23:858–867. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200203)23:6<858::AID-ELPS858>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belder D, Ludwig M. Electrophoresis. 2003;24:2422–2430. doi: 10.1002/elps.200305497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krenkova J, Foret F. Electrophoresis. 2004;25:3550–3563. doi: 10.1002/elps.200406096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J. Electrophoresis. 2002;23:713–718. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200203)23:5<713::AID-ELPS713>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hau W, Trau D, Sucher N, Wong M, Zohar Y. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2003;13:272–278. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Righetti PG, Gelfi C, Verzola B, Castelletti L. Electrophoresis. 2001;22:603–611. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200102)22:4<603::AID-ELPS603>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vreeland WN, Barron AE. Curr. Opin. Biotechn. 2002;13:87–94. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(02)00292-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Locascio LE, Henry AC, Johnson TJ, Ross D. Surface Chemistry in Polymer Microfluidic Systems. In: Oosterbroek RE, van den Berg A, editors. Lab-on-a-Chip. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2003. pp. 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou XM, Dai ZP, Liu X, Luo Y, Wang H, Lin BC. J. Sep. Sci. 2005;28:225–233. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200401920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan M, Cai S, Wybourne M, Keanna F. Bioconj. Chem. 1994;5:151–157. doi: 10.1021/bc00026a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henneuse-Boxu C, Duliere E, Marchand-Brynaert J. Euro. Poly. J. 2001;37:9–18. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ito Y, Nogawa M, Takeda M, Shibuya T. Biomaterials. 2005;26:211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yan M, Ren J. Chem. Mater. 2004;16:1627–1632. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keana JFW, Cai SX. J. Fluorine Chem. 1989;43:151–154. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soundararajan N, Platz MS. J. Org. Chem. 1990;55:2034–2038. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cai SX, Keana JFW. Bioconj. Chem. 1991;2:38–43. doi: 10.1021/bc00007a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai SX, Glenn DR, Keana JFW. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:1299–1304. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jadhav AV, Gulgas CG, Gudmundsdottir AD. Euro. Polym. J. 2007;43:2594–2601. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aldenhoff Y, Blezer R, Lindhout T, Koole L. Biomaterials. 1997;18:167–172. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(96)00095-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kotzyba-Hibert F, Kapfer I, Goeldner M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1995;34:1296–1312. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fleming S. Tetrahedron. 1995;46:12479–12520. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Platz MS. Nitrenes. In: Moss RA, Platz MS, Jones M, editors. Reactive Intermediate Chemistry. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2004. pp. 501–558. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schuster G, Platz MS. Adv. Photochem. 1992;17:69–143. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buchmueller KL, Hill BT, Platz MS, Weeks KM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:10850–10861. doi: 10.1021/ja035743+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schnapp KA, Platz MS. Bioconj. Chem. 1993;4:178–183. doi: 10.1021/bc00020a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schnapp KA, Poe R, Levya E, Sondararajan N, Platz MS. Bioconj. Chem. 1993;4:172–177. doi: 10.1021/bc00020a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gritsan NP, Tigelaar D, Platz MS. J. Phys. Chem. A. 1999;103:3458–3465. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gritsan NP, Gudmundsdottir AD, Tigelaar D, Zhu Z, Karney WL, Hadad CM, Platz MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:1951–1962. doi: 10.1021/ja9944305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kobayashi T, Ohtani K, Suzuki K, Yamaoka T. J. Phys. Chem. 1985;89:776–779. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schrock AK, Schuster GB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:5228–5234. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poe R, Schnapp KA, Young MJT, Grayzar J, Platz MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:5054–5067. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yi Y-Z, Kirby JP, George MW, Poliakoff M, Schuster GB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:8092–8098. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levya E, Platz MS, Persey G, Wirz JJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986;108:3783–3790. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abramovitch RA, Challand SR, Scriven EFV. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972;94:1374–1376. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abramovitch RA, Challand SR, Scriven EFV. J. Org. Chem. 1975;40:1541–1547. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Banks RE, Sparkes GR. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1972:1964. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Banks RE, Venayak ND. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1980:900. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Banks RE, Prakash A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1973:99. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Banks RE, Prakash A. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1974:1365. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Banks RE, Madany IM. J. Fluorine Chem. 1985;30:211. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rubina AY, Dyukova VI, Dementieva EI, Stomakhin AA, Nesmeyanov VA, Grishin EV, Zasedatelev AS. Anal. Biochem. 2005;340:317–329. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ekstrom S, Onnerfjord P, Nilsson J, Bengtsson M, Laurell T, Marko-Varga G. Anal. Chem. 2000;72:286–293. doi: 10.1021/ac990731l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chaurand P, DaGue BB, Pearsall RS, Threadgill DW, Caprioli RW. Proteomics. 2001;1:1320–1326. doi: 10.1002/1615-9861(200110)1:10<1320::AID-PROT1320>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arenkov P, Kukhtin A, Gemmell A, Voloshchuk S, Chupeeva V, Mirzabekov A. Anal. Biochem. 2000;278:123–131. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hollander A, Thome J, Keusgen M, Degener I, Klein W. Appl. Surface Sci. 2004;235:145–150. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dominick WD, Berhane B, Mecomber J, Limbach PA. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2003;376:349–354. doi: 10.1007/s00216-003-1923-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stone KL, Williams KR. Enzymatic Digestion of Proteins in Solution and in SDS Polyacrylamide Gels. In: Walker JM, editor. Protein Protocols Handbook. Totowa: Humana Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Paprica P, Margaritis A, Petersen N. Bioconjug. Chem. 1992;3:32–36. doi: 10.1021/bc00013a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rosencrance S, Way W, Winograd N, Shirley D. Surface Science Spectra. 1993;2:71–75. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Henry AC, Tutt TJ, Galloway M, Davidson YY, McWhorter CS, Soper SA, McCarley RL. Anal. Chem. 2000;72:5331–5337. doi: 10.1021/ac000685l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Omastova M, Pavlinec J, Pionteck J, Simon F, Kofina S. Polymer. 1998;39:6559–6566. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yu HH, Hwang SJ, Hwang KC. Opt. Comm. 2005;284:51–57. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ulman A. An Introduction to Ultrathin Organic Films: From Langmuir-Blodgett to Self-Assembly. San Diego: Academic Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li C, Yang P, Craighead HG, Lee KH. Electrophoresis. 2005;26:1800–1806. doi: 10.1002/elps.200410309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.