Abstract

In 2005, the Institute of Public Health at Georgia State University (GSU) received a 3-year community-based participatory research (CBPR) grant from the National Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities entitled Accountable Communities: Healthy Together (ACHT). Because urban health disparities result from complex interactions among social, economic and environmental factors, ACHT used specific CBPR strategies to engage residents, and promote the participation of community organizations serving, a low-income community in urban Atlanta to: (i) identify priority health and social or environmental problems and (ii) undertake actions to mitigate those problems. Three years after funding ended, a retrospective case study, using semi-structured, taped interviews was carried out to determine what impacts, if any, specific CBPR strategies had on: (i) eliciting resident input into the identification of priority problems and (ii) prompting actions by community organizations to address those problems. Results suggest that the CBPR strategies used were associated with changes that were supported and sustained after grant funding ended. Insights were also gained on the longer term impacts of ACHT on community health workers. Implications for future CBPR efforts, for researchers and for funders, are discussed.

Introduction

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is widely recognized as an alternative to expert-driven research that engaged residents only as study participants [1]. By contrast, CBPR emphasizes co-learning, power-sharing and capacity-building. Community members and academic researchers are equitably involved in all phases of the research initiative, from selecting the research questions to disseminating and acting on the results [2]. CBPR can lead to a deeper understanding of health problems due to lay knowledge, improved cultural sensitivity and relevance of the research methods and intervention strategies, enhanced reliability and validity of data collection tools, and a better fit of research activities into local context [1, 3]. During research implementation, CBPR can increase program participation, build community trust and ownership, promote community empowerment and contribute to higher response rates [3, 4]. In the interpretation and application phase, CBPR can lead to richer interpretation of findings, facilitate translation of research into practice, and increase the likelihood that research findings will be acted upon [3, 4].

CBPR has been used for promoting policy and environmental systems change [2, 5], both of which have the potential to influence population-level health and have become a key component in the federal funding for chronic disease prevention [6, 7]. Understanding how CBPR and the associated academic–community partnerships can play a role in these efforts will help to expand the relevance of CBPR beyond the more traditional intervention research paradigms. This article describes how specific CBPR strategies were employed to elicit input from community residents and engage community organizations in an urban Atlanta neighborhood; it also provides retrospective case-study evidence of the impact of those strategies

Overview of accountable communities: healthy together

The City of Atlanta has 25 neighborhood planning units (NPUs) listed alphabetically A–Z each representing a specific geographic area. The resident advisory council in each NPU makes recommendations to the Mayor and City Council on zoning, land use and other social and economic determinants that influence health and quality of life. In October 2005, the Institute of Public Health (IHP) at GSU received a 3-year grant from the National Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities to undertake ‘Accountable Communities: Healthy Together’ (ACHT). ACHT employed a CBPR strategy tailored to address the priority health problems (and the social and economic causes of those problems) perceived by the 17 000 predominantly low-income, African American residents of NPU-V, which consists of five contiguous neighborhoods.

A five-member ACHT advisory board was established consisting of the directors of two community-based organizations serving the neighborhood, a president of a state non-profit foundation, the director of the county department of health, and a professor of public health from a historically black medical school. The advisory board supported the notion that engaging the community in a meaningful way to identify priority neighborhood issues and strengthening organizational support for those priorities were critical first-step challenges for the success of ACHT.

Community engagement

Recruitment, hiring and training of community health workers

Because they share and understand the ethnicity, language, socioeconomic status and life experiences of those they serve, community health workers (CHWs) can link residents with needed health and social services especially when access to health and social services are limited [8, 9]. Accordingly, the recruitment and training of six CHWs from the target area was deemed an essential first step. CHW training focused primarily on developing skills in the assessment of local health indicators, the use of perception analyzers in group meetings and Photovoice, a method that enables participants to bring stories from other community members into the assessment processes through pictures they take [10].

Engagement of community organizations

Critical factors for effective CBPR are trust and mutual respect, both of which are core constructs of social capital. Putnam [11] distinguished two operational levels of social capital: (i) ‘bonding’ social capital which is a critical factor in creating and nurturing the kind of group solidarity that one sees in close neighborhoods and within ethnic enclaves and (ii) ‘bridging’ or ‘organizational’ social capital that reflects the capacity of community organizations not only to form strong alliances with one another but also with influential sources ‘outside’ the neighborhood.

Based on studies showing that organizational social capital is a major predictor of positive neighborhood change and stability [12, 13], the assessment of organizational or bridging social capital within NPU-V was an ACHT priority. To address that priority, representatives from 12 not-for profit organizations serving NPU-V residents agreed to participate in an ACHT planning. During that meeting, participants completed a questionnaire designed to assess the level of social capital among their respective organizations. Of the 12 participants, 10 indicated that they had ‘little or no interaction with one another during the past year’. Discussion of this finding led to a group consensus that ‘communication failure’ between these organizations (about their respective goals and services) could create ‘missed opportunities to help meet the needs of the residents they were try to serve. Discussion of this finding led to a recommendation from the group that instead of holding a community-wide meeting to announce its goals to the community (which was outlined in its grant proposal), ACHT should consider shifting the focus of that meeting. Specifically, they called for a session that would showcase to residents all of the various services that were available to them through the existing organizations.

ACHT acted on that recommendation by organizing and conducting a half-day health fair designed to heighten NPU-V residents’ awareness about existing community service organizations. Twenty-five organizations offering services in the areas of health, counseling, employment training and opportunities, spiritual development and support, youth development, safety and fire protection and law enforcement participated; each had a booth to share information. Recruitment efforts by CHWs resulted in a turnout of over 200 residents. Key contributors to the community-wide meeting included: Healthcare Georgia Foundation, Kroger Food Stores, Target Stores, the Atlanta Braves, the Atlanta Falcons Youth Foundation and International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW).

A follow-up survey of participating community organizations revealed that they found it very helpful to see how the work of other organizations was, to some degree, linked to their own organization's mission; a finding consistent with the aim of strengthening ‘organizational’ social capital. Commenting about the participating organizations, the NPU-V President at the time said, ‘These folks care about, and are dedicated to, serving the residents of NPU-V, and they share a common goal— doing what it takes to make our neighborhoods safer and healthier.’ The President of the Center for Working Families said, ‘It really says something about their level of interest when families are willing to give up part of their Easter Saturday to come together to participate and learn more about these services and programs; this ought to be an annual event.’

Community health assessment

Another CBPR strategy was to undertake actions that would help identify the priority health-related issues as perceived by NPU-V residents. To that end, three data-related tasks were undertaken: (i) to review health-related data relevant to the NPU-V area, (ii) to assess resident's perceptions of their health needs and (iii) to ascertain residents’ views of environmental health concerns.

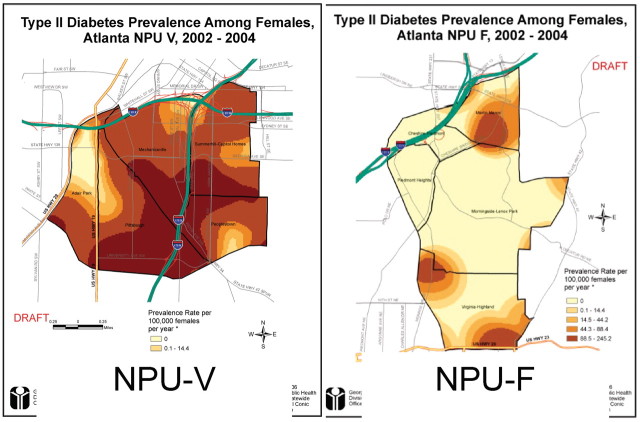

The review of NPU-V specific health-related data included two components. The first component consisted of community ‘listening sessions’ carried out in each of the five neighborhoods that make up NPU-V. The goals of the ‘listening sessions’ were: (i) to share with residents existing health data specific to NPU-V and (ii) to elicit their perceptions of their current health needs. CHWs and ACHT staff organized and implemented ‘listening sessions’ in each of the five NPU-V neighborhoods; the participation rates ranged from 20 to 30 residents per session. Perception analyzer technology was used to help prompt resident participation as they were presented with local level health data. Perception Analyzers are hand-held, electronic devices that enable people in a group setting to provide immediate and anonymous feedback for discussion. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) maps were used as a means to show how selected health-related indicators specific to NPU-V (e.g. heart disease, site specific cancers, diabetes) compared with other areas of urban Atlanta. This approach provided participants with a vivid, graphic illustration of the magnitude of health disparities that existed in NPU-V (Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Example of comparative GIS data presented during ‘Listening Sessions:’ Type II diabetes prevalence among females, in NPU-V and NPU F 2002-2004 (the darker the shading, the higher the prevalence).

After seeing the data, participants were asked to indicate (anonymously through their hand-held perception analyzer device) whether they were aware of those differences. Their responses were aggregated and immediately displayed on a screen. In all five ‘listening sessions’, this process generated considerable discussion and questions for clarification.

One of the questions posed during the ‘listening sessions’ was taken from the CDC Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System measured ‘frequent mental distress’: ‘thinking about your mental health, which includes stress, depression and problems with emotions, for how many days during the past 30 days was your mental health not good?’ Frequent mental distress is defined as having 14 or more days when mental health is ‘not good.’ The aggregate mean for all NPU-V participants from the five ‘listening sessions’ reporting 14 or more days of frequent mental distress was 26%, over 2.5 times greater than the national average of 9.4% [14]. Although participants were self-selected, the fact that so many were struggling with similar mental health challenges revealed an area of concern that was widely shared among neighborhood residents.

The second method, Photovoice, was used to elicit residents’ views and feelings regarding their day-to-day encounters with the environment and how that affected their health and quality of life [10] (Figure 2). Twenty residents, including three CHWs, were trained to take photographs to show the health impact of daily life in NPU-V. Selected staff members from ACHT, the Center for Working Families and the Annie E. Casey Foundation Civic Site were trained to use a semi-structured, open-ended interview guide employing the SHOWeD questioning technique, to facilitate the analysis of the photographs in small group sessions [15]. The key questions were: ‘What do you see here?’; ‘What is really happening here?’; ‘How does this relate to our lives?’; ‘Why does the problem exist?’; and ‘What can we do about it?’ Priority themes that emerged from the residents’ photographs were: trash, construction debris, poor neighborhood living conditions, vacant housing and loss of community.

Fig. 2.

Example of ‘Photovoice’ reflecting a resident’s concern.

An unanticipated effect of Photovoice was the recommendation made by the NPU-V Photovoice Guidance Committee. The committee, made up of 20 members representing local foundations, community-based organizations and media, recommended that findings from Photovoice be combined with data on the magnitude of these environmental challenges; in turn, this information could be used to seek policy actions aimed at improving the built environment in NPU-V.

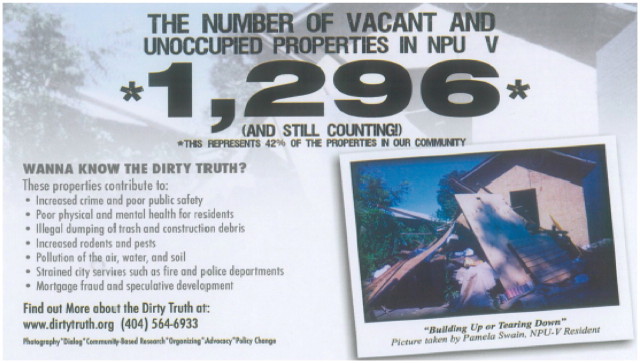

Following this recommendation, Photovoice participants and members of an existing neighborhood group surveyed vacant housing between November 2006 and January 2007. They found 1296 vacant or unoccupied properties in NPU-V, representing 42% of all properties in the neighborhood. This documentation led to the Dirty Truth Campaign, an NPU-V policy advocacy initiative (Figure 3). The Dirty Truth Campaign addressed a dual reality: ‘not only did vacant properties in disarray reflect a serious environmental problem, they also created conditions associated with poor mental health outcomes and crime’—two priorities identified by NPU-V residents.

Fig. 3.

‘Dirty Truth’ postcard. How Photovoice was used to call policy-makers’ attention to environmental problems associated in NPU-V.

The third data component was an aggregate assessment of Southside Medical Center (SMC) medical records to document the clinical utilization patterns (by the diagnosis of health problems) of NPU-V residents. Variables examined included gender, race or ethnicity, age, visit date, diagnoses (first five ICD-9 codes), procedures (first five codes), treatment, department or clinic visited, physician and type of insurance. A summary of that assessment is presented in Table I. It is relevant to note that, unlike findings from the ‘listening sessions’, those data make no categorical reference to depression or mental health.

Table I.

Top 10 diagnoses at SMC of NPU-V residents by gender (2004–05 records review)

| Males | Females |

|---|---|

| 1. Hypertension | 1. Hypertension |

| 2. Acute upper respiratory infection | 2. Diabetes |

| 3. Diabetes | 3. Inflammation of cervix or vagina |

| 4. Eye disorders | 4. Eye disorders |

| 5. Teeth disorder | 5. Menstrual problems |

| 6. Asthma | 6. Teeth disorders |

| 7. Skin rash edema | 7. Dermatophytosis |

| 8. Dermatophytosis | 8. Skin rash edema |

| 9. Atopic dermatitis | 9. Atopic dermatitis |

| 10. Conjunctiva | 10. Asthma |

Selection of community priorities

One month after completion of the community engagement and data collection strategies, over 100 community residents participated in a dinner meeting at SMC to review the data and select the ACHT priorities. CHWs and ACHT staff facilitated an in-depth review and discussion of all of the health-related data gathered including information from the ‘listening sessions’ and Photovoice activities. Residents then engaged in two rounds of a modified nominal group process enabling them to identify the health outcomes and social determinants they wanted ACHT to address. Although the epidemiologic data and SMC admission records pointed to diabetes, hypertension and other chronic diseases as the major health issues in NPU-V, residents chose depression and mental health as their priority health problem not only because of the high rate of frequent mental distress detected during the listening sessions, but also the Photovoice discussions pointing to an association between the displacement of residents and their feelings of loss and disconnection from others in the community. During the meeting, mental health and depression seemed to emerge as a ‘root problem’. As one resident put it, ‘… it is hard to choose just one among five problems because they are all linked to one another; but if we choose the root problem, then 2, 3, 4, and 5 will be taken care of by addressing number 1.’ There was a tie on the two priority social determinants: vacant housing and crime.

Out of that community-based process, two priorities emerged, which are the focus of this retrospective qualitative evaluation. The first addressed the top priorities of depression and mental health by focusing on improving access to mental health services. The second was an extension of Photovoice, which highlighted the negative impacts of vacant housing in the neighborhood, as the means to promote advocacy and community empowerment to improve environmental and housing conditions (factors known to influence depression and hopelessness) in NPU-V.

Case study methods

Behavioral and medical studies have shown that retrospective assessments, based on face-to-face interviews, can reveal outcomes similar to those found using prospective, controlled studies [16, 17]. In addition, interview strategies have the advantage of allowing for the exploration of important information that emerges during the interview process.

Three years after the ACHT grant funding ended, two methods were employed to gain insight into what impact, if any, the implementation of specific CBPR strategies had on (i) eliciting resident input into the identification of priority problems and (ii) prompting actions to address those problems. The first consisted of face-to-face, tape-recorded interviews with informed individuals who were administrative leaders and/or staff with ACHT collaborating organizations (n = 9 respondents from seven organizations). A similar interview was also conducted with the Commissioner of Planning and Development for the City of Atlanta. The second was a tape-recorded 2-hour focus group with the CHWs (n = 6) employed by ACHT. The focus group method was used to elicit input from the CHWs because the interaction inherent in a group setting is likely to yield information and insights that would be less likely to surface in a one-on-one setting [18]. Because the CHWs shared common experiences, the ‘chaining’ or ‘cascading’ effect that might be created during the focus group setting was deemed beneficial [19]. The focus group guide asked CHWs to reveal what tangible impacts, positive or negative, if any, the ACHT grant program (which ended in 2008) had within NPU-V in three areas: (i) access to mental health services, (ii) effects on environmental and housing issues and (iii) employment opportunities for CHWs.

The decision to elicit input from representatives of community organizations and CHWs, and not community residents at large, was influenced by three related factors: (i) the importance given to addressing the role of ‘organizational’ social capital within ACHT, (ii) a desire to identify the range of potential organizational-level outcomes that could best be identified by the key informants most deeply engaged in the project and (iii) time and budget limitations that precluded a larger sample size. The organizational informants were chosen because they represented organizations that were engaged in all aspects of the planning and implementation of ACHT.

In the application of both methods, participants signed informed consent forms advising them that:

confidentiality would be maintained throughout the process including when follow-up efforts are undertaken to verify actions or outcomes that may have been attributed to ACHT efforts;

consent would be obtained to use direct quotes and titles of participants within their respective organizations; and

the information gained from the process would be used in a report and paper that would be submitted for publication.

Interviews were recorded and transcribed. Transcripts from the individual and focus group interviews were reviewed by three of the authors. A tentative list of outcomes was generated in this initial phase of analysis. Validation of those outcomes was sought through a review of existing interviews for attribution of the outcome to the project. If the existing information yielded no confirmation or was contradictory, secondary interviews were conducted to provide corroborating evidence—four secondary interviews were conducted.

Results

Results are presented below in three categories. The first two address priorities that emerged from the community participation process: (i) access to mental health services and (ii) vacant housing and environmental issues. The third category describes the impact of the ACHT process on CHWs.

Access to mental health services

Interviews with leaders at SMC offered insights into possible longer range positive impacts on mental health services in NPU-V. They indicated that they had not anticipated that ‘mental health and depression’ would emerge as the priority concern of NPU-V residents especially because ‘mental health and depression’ did not show up in the ACHT list of the top 10 diagnoses for SMC admissions (Table I). The SMC CEO indicated that:

Those findings were a reflection of the reality that mental health and depression were not among those health conditions our primary care center screened for at the time. That doesn’t mean that depression and mental health were not problems, it meant we weren’t collecting those data! At that time our primary focus on mental health was through our programmatic efforts to address alcohol and substance abuse in our Alcohol and Substance Abuse Treatment Center, housed in a separate facility. By bringing the evidence of residents’ concern for mental health and depression to the attention of personnel during subsequent staff meetings, mental health was elevated as an issue of concern for SMC.

That awareness prompted SMC leaders to take two concrete actions. First, they combined behavioral and mental health and changed the name of their Alcohol and Substance Abuse Treatment Center to the Behavioral Lifestyle Enrichment Center. This move was intended to: (i) incorporate a wider breadth of mental health services (acknowledging that traditionally, almost all of the mental health services at Southside have been rendered through substance abuse treatment services) and (ii) ‘de-stigmatize’ mental health.

The CEO of SMC provided tangible evidence of mental health being elevated as a priority. ‘As a part of the organizational structure and staffing of SMC’s newest site in South Fulton County, which will be operational before the end of 2011, mental health screening and treatment, including licensed personnel, will be integrated as a core component of our primary care services.’

During their focus group, CHWs agreed that, prior to ACHT, NPU-V residents believed that if one sought help for depression or mental health problems it would be like ‘you were telling people you were crazy’. In light of that prevailing attitude, they were ‘somewhat surprised’ when depression and mental health emerged as a publicly declared priority by residents. Prior to ACHT, only 5% of women who were screened for postnatal depression at the Center for Black Women’s Wellness (CBWW) and received a positive score participated in the recommended follow-up therapy. Interviews with CBWW staff revealed that the absence of on-site counseling services was a major barrier to treatment. The CBWW director indicated during her interview that the public declaration that residents viewed mental health and depression as a priority in NPU-V ‘helped them make the case needed to secure grant support to provide on-site mental health counseling to NPU-V residents whose screening scores revealed they needed follow-up counseling’.

During the year and a half that funding was available, the rate of women who received follow-up counseling increased to 50%. When asked why the use of follow-up therapy services was not higher, the therapist who was contracted to provide those services replied, ‘Since the services were free, my guess is that the lack of compliance lies in a combination of factors, including not only the stigma frequently associated with mental health, but issues like the lack of transportation, and child care. And some feel and believe that trying to find a job is more important than counseling for depression, even though it is free.’

Despite these barriers, the therapist reported several success stories. ‘Some patients have clearly been stabilized on medications, and were adhering to follow-up treatment with outside resources. In addition, five of the CBBW clients have continued to seek services with me even after the grant ended.’ During the focus group, several CHWs said they knew of some clients who continued to seek counseling on their own after the grant ended. The therapist added, ‘Based on my experiences, the population in the NPU-V neighborhood would prefer home-visits due to the issues that arise with them coming to a location. If mental health services reached out and went to the people who needed help, people would probably begin to feel more comfortable with the idea of mental health support.’

A CHW who worked at the CBWW acknowledged that ‘while some progress had been made, the overall impact to date has been modest; the community needs a safe place for people to share their thoughts, and stigma remains an issue’. The director of an NPU-V non-profit organization that provides residents with job training, said:

Mental health is not being prioritized for this community the way that it needs to be. People are not advocating for mental health services within the political scene. Economics are still the focus. Substance abuse, as a mental health problem, needs to be a focus within this community, especially in men. Women tend to not seek treatment either.

Vacant housing and environmental issues

Four of the six CHWs indicated that the ‘Dirty Truth’ campaign, triggered by public response to results from the Photovoice component of ACHT, had a clear, positive impact on NPU-V. Nearly 1 year after the termination of ACHT grant support (9 July 2009), the Dirty Truth Campaign received official non-profit status from the Internal Revenue Service under the name 303 Community Coalition, Inc. (303 CC). The ‘303’ in the name represents zip codes in the city of Atlanta, many of which are plagued by vacant properties, blight and lack of community-driven economic development. The mission of 303 CC is working to help create urban communities where affordable housing, renovated for and by community residents, is the norm (see: http://www.dirtytruth.org/about.html).

An interview with Atlanta Commissioner Planning and Community Development confirmed that the NPU-V vacant property counts, spearheaded by Photovoice and the Dirty Truth Campaign, promoted an open dialogue with the City of Atlanta’s Code Enforcement Office. This led to an independent assessment and report of NPU-V vacant properties by the National Vacant Properties Campaign that was jointly funded by the City of Atlanta, the Annie E. Casey Foundation Atlanta Civic Site and the Georgia State University ACHT grant. The National Vacant Properties Campaign has been renamed and is now the ‘Center for Community Progress’. City officials confirmed that the Atlanta Code Enforcement Office followed up on two policy actions recommended in the report: (i) helping non-profits serving NPU-V in acquiring and re-using vacant properties more quickly and efficiently and (ii) addressing problematic properties near schools and parks that put children in danger. Photovoice documented the sites deserving highest priority for action because their location put children in danger. In an interview with James Shelby, Atlanta Commissioner for Planning and Community Development, the commissioner confirmed that ‘the city’s decision to address properties in NPU-V that were in close proximity to schools and parks was influenced by the recommendations from the report they had commissioned from the Vacant Properties Campaign’.

In a follow-up interview with the Director of the Center for Working Families at that time, she confirmed the view by CHWs: ‘it is certainly fair to say that the products of Photovoice and the Dirty Truth Campaign were clearly driving forces behind the removal of those vacant properties’. The director said that Photovoice and subsequent Dirty Truth Campaign were also instrumental in the multiorganizational collaborative efforts that led to the formation of the Community Economic Development Institute and the emergence of community-driven ‘study circles’, through which neighborhood residents took the lead in determining what outcomes they wanted to achieve through the redevelopment process.

The director also pointed out that even after the ACHT grant ended, lessons learned from ACHT were evident in the emergence of the Sustainable Neighborhood Development Strategies, Inc. (SNDSI), which was established as a non-profit developer charged with the implementation of the community-driven redevelopment plan. SNDSI has embarked upon a development approach that preserves the heritage and identity of one of the NPU-V neighborhoods (Pittsburgh) by adopting a policy of non-displacement of neighborhood residents, a key theme that came out of the Photovoice process [20]. Located along Atlanta's planned Belt Line (a redevelopment corridor that follows mostly abandoned rail lines circling Atlanta), the University Avenue site provides an exceptional opportunity for a transit-oriented development. Another SNDSI priority is to establish the Pittsburgh neighborhood as a model for sustainable, environmentally conscious practices, including energy efficient, healthy homes and training in green building trades so that residents can achieve economic stability and long-term self-sufficiency.

A CHW who, after termination of the ACHT grant, was hired by a local non-profit organization, Environmental Community Action Inc (ECO Action) stated that: ‘in 2008, ECO-Action applied for, and received a $100,000 grant from the Environmental Protection Agency designed to develop a sustainable environmental health collaborative within NPU-V involving residents, community-based organizations, municipal and state agencies, local businesses, and Georgia State University. There is no doubt in my mind that the grant would not have been made without the foundation that was created by our ACHT work, especially through Photovoice and the subsequent actions taken to address the challenges of the built environment in NPU-V.’

Impact of ACHT on CHWs

For ACHT, CHWs constituted the central core for communication among helping organizations and residents of NPU-V. Three years after grant funding ended all six of the CHWs were employed: five in health or social service related positions, three of whom had been hired by the SMC, and one had started a local cleaning service business. During the focus group session, CHWs indicated that the competencies and contacts they had developed through their work with ACHT were major assets as they sought employment after grant support ended, these competencies included, interviewing and listening skills, the capacity to link objective and subjective data, establishing specific goals and objectives, and organizing and managing group processes.

In reflecting on the value of the three ACHT CHWs now employed his organization, CEO of SMC said: ‘You can’t address a community’s perceived needs unless you know them! If we undertake a project, we must be able to demonstrate a benefit to the community.’ In addition he said, ‘we were impressed by the use of ‘perception analyzers’ by CHWs to elicit community input during neighborhood meetings. As a result, we borrowed the ‘perception analyzers’ from GSU to use in our community meetings to get input on our services … the results were very helpful in our own planning and staff training efforts. For example, we took steps to simplify and avoid duplication in the SMC intake registration process because a large number of patients had identified components of the process as repetitious and frustrating.’

During their focus group, CHWs identified a phenomenon they all experienced when grant funding ended. As one worker put it, ‘university people who manage CBPR projects like ours need to fully understand that our jobs don’t end when the grant does!’ There was unanimous concurrence with the following observation: ‘We were all trained to work closely with residents to help them not only with the identification of their health and social needs, but also in pursuing avenues to meet those needs. When the project was over and we were without jobs and pay, ironically our job didn’t end! Among those people we had made contacts with and befriended, many continued to seek our assistance because they had no other sources to turn to for help.’

Another CHW said, ‘This is a complex issue because at one level, it feels good to be perceived as one whose advice is sought out and valued. It is as if you are an informed leader whose friends and neighbors seek your counsel; and you want to help them because all of our lives we’ve been taught that’s what friends and neighbors should do! On the other hand, we have our own families, our own health-related needs, and our own interests, like trying to get jobs ourselves!’

The CHWs were unanimous in their recommendation that academics who work with disadvantaged populations need to address this reality before they start programs like ACHT. If left unattended, this impact will merely reinforce the sentiment at the local level that disadvantaged populations are being ‘used’ to benefit goals of academic centers, not necessarily those they intend to serve.

Several CHWs indicated that there were times when tensions arose between university faculty or staff and local residents over the differential reward structures for university personnel versus those working in the communities. ‘One could argue that it is a “research disparity” when the university gets all of the “indirect costs” of a federal CBPR grant; this does not reflect a “partnership” in the eyes of those in the community.’ As Story et al. [21] and Minkler [22] have observed, these views and experiences of the ACHT CHWs were not unique:

It is the academic or professional researchers who stand to gain the most from such collaborations, bringing in grants (often with salary support), adding to their publication lists, and so forth. The common expectation that community partners will work in a minimally paid capacity and the fact that receipt of compensation may take months … are sources of considerable resentment and frustration. (p. 689)

Discussion

Based on these 3-year retrospective case-study findings, planned CBPR strategies designed to enhance the participation of community organizations and residents do yield tangible results. The recognition, both by NPU-V residents and community organizations, of the need for accessible mental health services is a notable example. A national US survey indicated that those diagnosed with a mental disorder do not access care until nearly a decade following the development of their illness, and one-third of people who seek help receive minimally adequate care [23]. While mental health stigma among NPU-V residents and lack of access to services remain barriers to seeking mental health services, there is tangible evidence that positive changes in mental health service availability and use occurred as a result of the ACHT initiative. Grant funding enabled the CBWW to provide on-site mental health counseling services to those who were referred for postnatal depression.

Also, prior to ACHT, the primary mental health services offered by the SMC were limited to substance abuse. Since then, SMC has re-framed that focus to include behavioral health and now offers a wider range of mental health services. SMC leaders indicated that these changes are the direct result of findings from the ACHT listening sessions: that depression and mental health are of the utmost importance to NPU-V residents.

ACHT also led to increased efforts to address environmental challenges in the neighborhood. The translation of Photovoice findings into the Dirty Truth campaign provided a source of empowerment to community members enabling them to address key built environment issues in NPU-V that had been previously ignored. As a result, cleaning up vacant properties that had been boarded up or torn down, especially near areas where children lived and played, became a high priority. Two non-profit organizations (303 Community Coalition and SNDSI) were created to address critical housing and environmental issues identified. The Atlanta Code Enforcement Office also took action on issues raised by NPU-V residents and key community organizations. Collectively, these examples reinforce findings from Checkland and Scholes [24], Midgley [25] and Minkler et al. [5] that the active engagement of organizations within a community ‘system’ and the development of strong community partners, can help trigger sustained changes because stakeholders have a better understanding of both the relevance and importance of those changes.

The ACHT CHWs reported that the skills, experiences and contacts that they acquired during the grant period constituted major assets to finding employment after the grant ended. It also positioned them as credible helpers and in some instances, leaders in the community. Their current employment positions, most of which are in organizations that serve the NPU-V community, allow them to continue positive work in the community while communicating needs of residents to the organizations that serve them.

However, feedback from CHWs indicated that they encountered a problem that was not mentioned or discussed at any time during their training or service: when their employment was terminated at the end of the grant, residents continued to seek their assistance and counsel. The more effective CHWs are in their work, the greater the likelihood that requests and demands for their assistance will continue after the program ends. The good news is, the effects of the CBPR research are lasting and position CHWs as community leaders. The downside is that it places an unanticipated burden on CHWs to continue to provide prior services without compensation. Both CBPR grant-makers and researchers would benefit by determining: (i) how common this effect is and (ii) how to address the inevitable demands and burdens that are likely to be placed on former CHWs.

Throughout the planning and implementation of ACHT, steps were taken to follow the principles of community participation and engagement reflected by insights and guidelines recommended by Minkler and Wallerstein [26] and Green et al. [27]. Emphasis was given to enhancing community input especially as that related to the (i) documentation of the potential causes of health disparities in NPU-V including the perceptions of residents and (ii) effective communication of those causes and their potential solutions with leaders of the organizations that serve the NPU-V community, and City of Atlanta policy-makers.

Limitations

This case study has several limitations. The disadvantage of using interviews as the means to detect effects is the ‘interviewer effect’, wherein responses by interviewees could be influenced by their perceptions of what they think the researcher wants to hear. In addition, because most of those interviewed were directly or indirectly involved with the ACHT project, they may have been prone to bias because of a desire to prove that their efforts made a difference [28]. Feedback from residents not involved with ACHT or collaborating organizations could have provided another perspective on the effects reported here.

Conclusion

This retrospective assessment shows that CBPR can provide an effective platform for bringing local residents together to establish health priorities that prompt community organizations to enhance their level of collaboration in addressing complex challenges like vacant housing, the stigma associated with mental health, and access to mental health services. Findings from this case study do support the notion that residents, supported by trained CHWs, can use techniques like Photovoice and ‘listening sessions’ to build a community-wide response to their adverse living conditions and, the effect implementation of those techniques can prompt local community organizations, and local government, to take actions to address those conditions. However, in the absence of political and economic support to expand and sustain these efforts, community residents may view the CBPR process as yielding short-term benefits that go primarily to the academic institutions and researchers who manage them. Leaders from both applied and academic public health need to address the sustainability of efforts initiated through CBPR and assure that the major benefits of the program accrue to community residents.

Funding

This retrospective case study was supported by the Georgia State University Center of Excellence: Syndemics of Disparities Project; National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, (#5P20MD004806-02).

Acknowledgments

For their time and thoughtful input into this paper, the authors would like to thank Travie Leslie, Pamela Swain, Roddy Longino, Dalisa Boswell, Catherine Prather and Clemmie Jenkins (former CHWs), Mtamanika Youngblood, President/CEO, Sustainable Neighborhood Development Strategies, Inc., Jemea Dorsey, Director, Center for Black Women’s Wellness, Deborah James, Director, Ropheka Rock of the World, Keely Foster, Mental Health Comprehensive Services, Dr Yomi Noibi, Director of ECO Action, James Shelby, Atlanta Planning and Community Development Commissioner and Dr David Williams, CEO Southside Medical Center.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- 1.Minkler M. Community-based research partnerships: challenges and opportunities. J Urban Health. 2005;82(2 Suppl. 2):ii3–12. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Israel B, Coombe C, Cheezum R. Community-based participatory research: a capacity-building approach for advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:2094–102. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.170506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cargo M, Mercer S. The value and challenges of participatory research: strengthening its practice. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:325–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.091307.083824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jagosh J, Pluye P, Macaulay A, et al. Assessing the outcomes of participatory research: Protocol for identifying, selecting, appraising and synthesizing the literature for realist review. Imp Science. 2011;6:24. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minkler M, Vasquez V, Chang C, et al. Promoting Healthy Public Policy through Community-based Participatory Research: Ten Case Studies. Policy Link, University of California, Berkeley; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Community Transformation Grants. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/communitytransformation/. Accessed: 20 November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frieden T. A framework for public health action: the health impact pyramid. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:590–5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.185652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eng E, Parker E. Natural helper models to enhance a community’s health and competence. In: DiClemente RJ, et al., editors. Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 2002. 126. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Witmer A, Seifer S, Finocchio L, et al. Community health workers: integral members of the health care work force. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:1055–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.8_pt_1.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang C, Burris M. Photovoice: concept, methodology and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24:369–87. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Putnam RD. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Shuster; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tempkin K, Rohe W. Neighborhood change and urban policy. J Plan Educ Res. 1996;15:159–70. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tempkin K, Rohe W. Social capital and neighborhood stability: an empirical investigation. Housing Policy Debate. 1998;9:61–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moriarty D, Zack M, Holt J, et al. Geographic patterns of frequent mental distress U.S. adults, 1993–2001 and 2003–2006. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:497–505. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang C. Photovoice: a participatory action research strategy applied to women’s health. J Women’s Health. 1999;8:185–92. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1999.8.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sallis J, Saelens B. Assessment of physical activity by self-report status, limitations, and future directions. Res Q Exer Sport. 2000;71(2 Suppl):S1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aseltine R, Carlson K, Fowler F, et al. Comparing prospective and retrospective measures of treatment outcomes. Med Care. 1995;33(4 Suppl):AS67–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hughes D, DuMont K. Using focus groups to facilitate culturally anchored research. Am J Commun Psychol. 1993;21:775–806. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindlof TR, Taylor BC. Qualitative Communication Research Methods, 2nd Edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Redwood Y, Schulz AJ, Israel BA, et al. Social, economic, and political processes that create built environment inequities: perspectives from urban African Americans in Atlanta. Fam Community Health. 2010;33:415–29. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e3181c4e2d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Story L, Hinton A, Wyatt S. The role of community health advisors in community-based participatory research. Nursing Ethics. 2010;17:117–26. doi: 10.1177/0969733009350261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minkler M. Ethical challenges for the ‘outside’ researcher in community based participatory research. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:684–97. doi: 10.1177/1090198104269566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, et al. Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch General Psychiatry. 2005;62:603–13. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Checkland P, Scholes J. Soft Systems Methodology in Action. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Midgley G. Systemic Evaluation: Philosophy, Methodology, and Practice. New York: Kluwer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green L, George A, Daniel M, et al. Guidelines for participatory research in health promotion. In: Minkler M, Wallerstien, editors. Community-based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco Jossey-Bass Inc, 419–428. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johannes CB, Crawfort SL, McKinlay JB. Interviewer effects in a cohort study, results from the Massachusetts women health study. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:429–38. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]