Abstract

There is increasing evidence that physical activity (PA) can enhance weight loss and other outcomes after bariatric surgery. However, most preoperative patients are insufficiently active, and without support, fail to make substantial increases in their PA postoperatively. This review provides the rationale for PA counseling in bariatric surgery and describes how to appropriately tailor strategies to pre- and postoperative patients.

Keywords: exercise, severe obesity, treatment, clinical care, gastric bypass, laparoscopic adjustable gastric band

INTRODUCTION

Severe obesity (body mass index [BMI] ≥35 kg/m2) is a serious health condition with significant comorbidity and impairments in quality of life (29). Bariatric surgery is the most effective treatment for severe obesity, generally resulting in clinically significant weight loss, as well as improvement or resolution of related comorbidities, such as type 2 diabetes, and enhanced physical functioning and quality of life (15). However, weight loss and related outcomes vary greatly among patients (35). While some of this variability is attributed to differences in surgical procedure and related technical factors, there is growing evidence that patients' health behaviors, including physical activity (PA), may play a significant role in weight loss and other postoperative outcomes (14,17,19,33).

Studies of self-reported PA consistently report substantial increases in pre- to postoperative PA (17). Conversely, our work utilizing activity monitors has shown that the majority of preoperative patients are both inactive and highly sedentary (8,10,20), and fail to make large increases in their PA postoperatively despite substantial weight loss (7,23). However, our most recent work provides preliminary evidence that, with support, preoperative patients can achieve large PA increases. (6). Two recent small randomized controlled trials indicate that PA interventions initiated postoperatively can also increase patients' PA levels and contribute to improved surgical outcomes, including weight, body composition and fitness (14,33). There is also evidence to suggest increasing PA preoperatively may reduce surgical complications (24), and substantial support showing that consistent PA is the most important predictor of long-term weight loss maintenance (12). In the current review, we use our research, along with that of others, to support the rationale that PA counseling should be initiated prior to surgery and continued throughout the postoperative period. Additionally, we describe how to appropriately tailor PA counseling strategies to the particular challenges and needs of bariatric surgery patients.

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY RECOMMENDATIONS

Despite recognition that PA promotion is an important component of a comprehensive surgical weight loss program (1,5,30), there are currently no evidence-based pre- or postoperative PA guidelines. However, several organizations have recently issued recommendations. The 2007 Expert Panel on Weight Loss Surgery recommends that patients be encouraged to increase pre- to postoperative PA, in particular low- to moderate-intensity exercise (5). The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) recommends mild exercise (including aerobic conditioning and light resistance training) 20 min/day 3–4 days/week prior to surgery to improve cardiorespiratory fitness, reduce risk of surgical complications, facilitate healing and enhance postoperative recovery (4). The American Heart Association (AHA) recommends a similar “mild” preoperative exercise regimen of low- to moderate-intensity PA at least 20 min/day 3–4 days/week (30). Joint guidelines from the ASMBS, the Obesity Society, and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists recommend that, in general, postoperative patients adhere to general recommendations for a healthful lifestyle, including exercising for at least 30 min per day, to achieve optimal body weight and improve body composition (25). However, evidence-based PA guidelines for healthy and overweight/obese adults (summarized in Table 1) suggest that greater amounts of PA are needed for controlling body weight. In addition, evidence points to a dose-response relationship between PA and both weight loss and long-term weight loss maintenance, such that higher levels of PA translate to greater benefits (12).

Table 1.

Evidence-Based Physical Activity Guidelines for Healthy and Overweight/Obese Adults

| Agency | Target Population | Benefit | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS)(37) | Healthy adults | General health benefits* | ≥150 minutes (min) of aerobic moderate-intensity physical activity (PA) or 75 min of aerobic vigorous-intensity PA per week in episodes of ≥10 min, plus muscle-strengthening activities for major muscle groups ≥2 days per week |

| Institute of Medicine (IOM) (16) | Adults | Prevention of weight gain Weight-independent health benefits |

60 min of moderate-intensity PA per day |

| American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) (12) | Overweight and obese adults | Weight loss Prevention of weight regain |

≥250 min of moderate-intensity PA per week |

| International Association for the Study of Obesity (IASO) (32) | Formerly obese adults | Prevention of weight regain | 60- to 90-min of moderate-intensity PA per day (or lesser amounts of vigorous-intensity PA) on most days of the week |

Improved cardiorespiratory fitness and muscular fitness, prevention of falls, increased bone density, reduced depression, improved sleep quality, better cognitive function, and lower risk of early death, coronary heart disease, stroke, hypertension, adverse lipid profile, type 2 diabetes, and colon, breast, endometrial and lung cancer.

Abbreviations: PA, physical activity, Min, minutes

The absence of evidence-based bariatric surgery-specific PA guidelines is likely due to the fact that the study of bariatric surgery patients' PA and its relation to surgical outcomes is still in its relative infancy. However, evidence is mounting, and an expert panel from the ASMBS and the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) has been assembled to develop pre- and postoperative PA guidelines.

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY OF BARIATRIC SURGERY PATIENTS

Given the importance of PA in behavioral treatments for obesity (38) there is a burgeoning interest in the role of PA behaviors within the context of bariatric surgery. According to a 2010 review (17), bariatric surgery patients make substantial increases in their PA postoperatively and higher PA levels pre- and postoperatively are associated with greater weight loss. However, in nearly all of the included studies, PA assessment relied exclusively on self-report instruments, most commonly, non-validated retrospective questionnaires. These measures carry high potential for inaccuracies due to a combination of patients simply forgetting, attempting to reconstruct memories using assumptions that are prone to bias, having difficulty differentiating between postoperative improvements in physical ability with time being physically active (18), and seeking to present themselves in a positive light to researchers or clinicians (38). Such inaccuracies could potentially lead to invalid conclusions and inappropriate guidelines that could affect surgical outcomes. Consequently, the authors of the present review and other groups have recently employed objective measures to examine bariatric surgery patients' preoperative PA levels and pre- to postoperative changes in PA, as described below.

Preoperative Physical Activity

To date, three different types of objective monitors have been used to assess bariatric surgery patients' preoperative PA levels: pedometers, accelerometers, and multi-sensor devices (i.e., SenseWear armband). Two pedometer studies found that participants averaged 4621±3701 (18) and 6061± 2740 (11) steps/d preoperatively, respectively, suggesting that most preoperative patients are “sedentary” (< 5000 steps/d) or “low active” (5000–7499 steps/d). However, selection bias might have affected the results of these studies given that pedometer diaries, in which participants recorded their daily step counts, were completed by only 55% (11 of 20) (18) and 37% (48 of 129) (11) of participants, respectively. Additionally, because steps were manually recorded, it is possible that participants didn't accurately report their steps. Finally, the pedometers used in these studies (Sportline 330 and Digi-walker SW-200, respectively) may have systematically under-counted steps, as the accuracy of these pedometers is worse at slow walking speeds and in those with abnormal gaits (23). King et al. (20,23) countered many of the above limitations in the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery-2 (LABS-2) study via use of the Stepwatch Activity Monitor, a valid and reliable measure of ambulatory PA in obese adults from which minute-by-minute step count data from the past week was downloaded for analysis. Participants' (n=757) average preoperative ambulatory PA (7569±3159 steps/d) (20) was higher than that reported in the above studies (11,18). However, one fifth (20%) of participants were sedentary and 34% were low active, and only 19% accumulated at least 10,000 steps/d, a common criterion for sufficient PA. Moreover, using high-cadence (≥80 steps/min) minutes as a proxy measure of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA), the majority (61%) of participants did not engage in any bout-related MVPA (e.g., MVPA occurring in bouts ≥10 minutes) (23). Bond et al. reported similar results from a study using the RT3 triaxial accelerometer, which detects accelerations for each of the 3 planes across 1-minute intervals and converts these data to activity counts per minute, which are used to estimate minutes of MVPA (defined as ≥984 activity counts/min in this study). Specifically, 68% of the 22 participants did not engage in any bout-related MVPA during the past week and only 5% accumulated ≥150 min/wk in these bouts.(8) A subsequent study by Bond et al. (10) using the SenseWear armband, which integrates data from a biaxial accelerometer and a combination of sensors (heat flux, galvanic skin response, skin temperature, and near body temperature) to estimate energy expenditure at different levels of intensity, examined the amount of time that bariatric surgery candidates (n=42) spend in sedentary behaviors, activities performed primarily while sitting that involve very low levels of energy expenditure (i.e., <1.5 Metabolic Equivalent (MET)). Participants spent 79–80% of their time sedentary, considerably higher than the percentage of time sedentary (57–69%) reported in the general adult population. Thus, recent research with objective assessment of PA indicates that although there is a wide range of PA levels among preoperative patients, most have low PA levels and spend the vast majority of their time in sedentary behaviors.

Pre- to Postoperative Changes in Physical Activity

Given the heterogeneity of PA assessment among studies it is difficult to quantify the mean pre- to postoperative change in PA. All studies assessing PA via self-report questionnaires report significant increases in PA, with two-thirds of studies reporting increases of 100–500% (17). The two pedometer studies described above also reported significant increases in mean daily steps of 43% at 3 months (18) and 59% at 12 months postoperatively (11), respectively. However, due to the limitations already described (e.g., selection bias, self-report of steps) these values needed confirmation. Our recent work (7,23) has shown that the magnitude of pre- to postoperative increases in PA determined by self-report and pedometer studies is not corroborated by accelerometry. Bond et al. compared self-reported (via the Paffenbarger Physical Activity Questionnaire) and objectively-measured (via the RT3 accelerometer) changes in MVPA from pre- to 6-months postoperatively among 20 patients.(7) While average self-reported MVPA min/wk increased 500% (45 min/wk to 212 min/wk), there were no significant changes in average objectively-measured total (186 to 151 min/wk) and bout-related (41 to 40 min/wk) MVPA, and only 5% of participants accumulated at least 150 min/wk of bout-related MVPA postoperatively. In an analysis of 310 LABS-2 participants, King et al. found that while several objectively-measured PA parameters increased significantly from pre- to 1-year postoperatively, the magnitude of the change was only 19% for steps, 10% for active minutes, and 16% for bout-related MVPA (23). Accordingly, postoperative patients still only accumulated a median of 23 min/wk of bout-related MVPA, and only 11% accumulated at least 150 min/wk of bout-related MVPA. This study also revealed that a quarter of participants were actually ≥5% less active 1-year postoperatively compared to preoperatively. Further corroboration of low postoperative PA comes from a study of 40 bariatric surgery patients who wore the SenseWear Pro armband for one week 2–5 years postoperatively and averaged only 49 min/wk of bout-related MVPA (19).

In summary, our recent research using objective PA measures appears to counter previous findings derived from self-report measures that suggest patients make substantial increases in their PA postoperatively. Indeed, our data suggest that the vast majority of preoperative patients do not engage in PA at levels recommended to obtain general health benefits, and that only a small minority of patients achieve this recommendation postoperatively.

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY INTERVENTIONS IN BARIATRIC SURGERY PATIENTS

Despite the potential importance of PA in bariatric surgery, few randomized controlled trials (RCT) of PA interventions have been conducted. Trials which test whether PA interventions increase pre- or postoperative PA and/or impact bariatric surgery outcomes are described below.

Preoperative Intervention

Bari-Active is an ongoing NIH-funded preoperative RCT comparing a 6-week preoperative behavioral intervention involving weekly individual, face-to-face counseling to standard preoperative care. Using behavioral strategies, such as self-monitoring, goal setting and stimulus control, the intervention focuses on the goal of accumulating at least 30 minutes of moderate-intensity walking in bouts of at least 10 minutes every day. Preliminary analyses with the first 35 subjects suggest that the Bari-Active intervention successfully produces large increases in objectively-measured bout-related MVPA, consistent with public health recommendations (6).

Postoperative Interventions

Approximately 4 weeks postoperatively Egberts et al. randomized 50 laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding patients to either usual care or 12 weeks of aerobic and strength building exercises with a personal trainer for 45 min/3 times a week (14). Those in the exercise group had better excess weight loss (37%) and change in percentage body fat (3.6%) compared to the usual care group (27% and 1.6%, respectively) at the end of the intervention.

Shah et al. randomized 33 Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and adjustable gastric banding patients who were three to 102 months postoperative to either 12 weeks of dietary counseling only (n=12) or dietary counseling plus a high volume exercise program incorporating exercise-related behavioral therapy (n=21) (33). Over the first 4 weeks the exercise group progressed to a goal of at least 2000 kcal/week from moderate-intensity PA (MPA) accumulated over at least 5 days/week. Attendance at a fitness center for partially supervised exercise 1 to 2 times per week was encouraged. After 12 weeks the exercise group had significantly greater improvements in self-reported PA, objectively-measured fitness, and postprandial blood glucose levels. The groups did not significantly differ on changes in weight, dietary intake, fasting lipids, glucose, insulin or HRQoL, perhaps due to: the small sample size and distribution of participants (20 vs. 8 at follow-up), the effect of the dietary counseling (which may have overpowered the effect of PA counseling), the short duration of the intervention, or the variable time in which the intervention was initiated, as some participants may have been actively losing weight while others may have been maintaining or gaining weight at study entry.

Translating Findings of Randomized Clinical Trials to Clinical Practice

Clinicians report that doubt of counseling efficacy and lack of patient interest are barriers to providing PA counseling in clinical care (34). These barriers may in part be responsible for recent survey results which revealed that only 22% of patients of Bariatric Surgical Centers accredited by the American College of Surgeons (ACS) Bariatric Surgery Center Network (BSCN) report having received postoperative exercise consultation (28), despite BSCN accreditation requirements to establish procedures for exercise counseling (3). However, the RTCs described above, which provide evidence that motivated patients can increase their PA level, leading to important health benefits, if given very clear guidelines and assistance in reaching PA goals, justify routine PA counseling and support in the clinical care of bariatric surgery patients. Due to patients' health-related barriers to PA, clinicians may be inclined to hold off on initiating PA counseling until patients have benefited from surgery-induced weight loss. However, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services PA guidelines (37) indicate that “adults with chronic conditions obtain important health benefits from regular PA; when adults with chronic conditions do activity according to their abilities, PA is safe.” In addition, there are several compelling reasons to initiate PA counseling preoperatively (see table 2). Accordingly, we advocate both pre- and postoperative PA counseling.

Table 2.

Reasons to Initiate Physical Activity Counseling Prior to Banatric Surgery *

| • Higher aerobic fitness at time of surgery may help reduce surgical complications, and facilitate healing and postoperative recovery. |

| • Preoperative physical activity (PA) counseling may help patients achieve the mindset that bariatric surgery is a tool for making positive behavior changes. |

| • Many preoperative patients are receptive to PA encouragement and advice. |

| • Many preoperative barriers to PA persist after surgery if they are not addressed. |

| • Preoperative PA counseling can lead to substantial increases in preoperative PA which is maintained postoperatively. |

| • Preoperative PA attitudes (e.g., perceiving more exercise benefits, having more confidence to exercise) and behaviors (i.e., increasing physical activity prior to surgery, and physical activity level at time of surgery) predict higher postoperative PA. |

Information from reference (40).

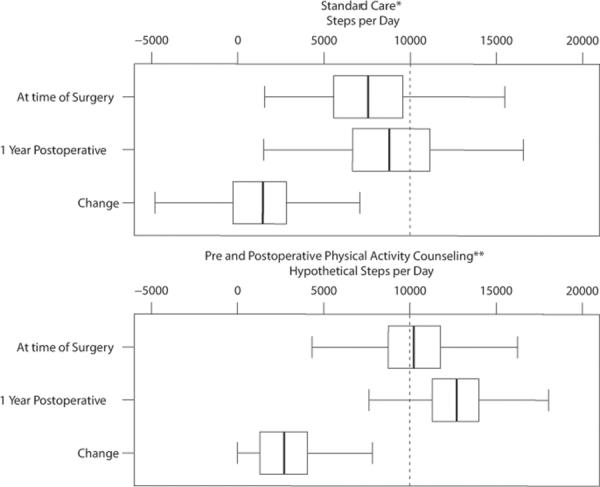

Figure 1 illustrates how pre- and postoperative PA counseling could change the distribution of bariatric surgery patients' PA before and 1 year following surgery. First, the PA level of patients receiving standard care is shown. Underneath, the hypothesized PA level of patients receiving both pre and postoperative counseling, based on the RCTs described above (6, 14, 33), is shown; after receiving pre and postoperative PA counseling roughly half of patients are “active” by the time they undergo surgery and the great majority of patients are “active” by their 1 year follow-up visit. Next we describe how proven PA counseling strategies can be used in clinical practice to safely and effectively counsel pre- and postoperative patients to increase their PA level, in particular addressing their unique challenges and needs.

Figure 1.

Schematic Illustrating Potential Impact of Pre- and Postoperative Physical Activity Counseling versus Standard Care on Patients' Physical Activity

Figure Footnotes:

* Physical activity resulting from standard care based on the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery-2 (20).

** First, preliminary results from the Bari-Active study (6) were applied to preoperative PA data of patients receiving standard care to estimate physical activity (PA) at time of surgery resulting from preoperative PA counseling. Next, postoperative changes in PA resulting from postoperative PA counseling were estimated from RCTs (14, 33), and then applied to estimated physical activity at time of surgery to estimate postoperative PA.

TAILORING PHYSICAL ACTIVITY COUNSELING TO BARIATRIC SURGERY PATIENTS

The five A's organizational construct (Assess, Advise, Agree, Assist, Arrange) (39) is a helpful tool for structuring PA counseling in clinical care (26).

Assess

In order to appropriately tailor PA advice and assistance to the needs and conditions of each individual bariatric surgery patient, PA counseling should begin with a patient interview (40). The clinician should assess the patients' PA-related knowledge, beliefs and values, past PA experiences, preferences for PA and current PA level, attitudes regarding willingness and confidence to change, and potential barriers to implementing a PA program. To help motivate patients it is also helpful to assess their health-related goals, as well as goals they may have for family members, as some patients may be more willing to make behavioral changes to help others.

The clinician must also assess the patients' ability to safely increase their PA level. Although many obese patients can begin an exercise program with a gradual increase in PA without undergoing diagnostic exercise testing, ACSM recommends that patients with current symptoms or history of metabolic, cardiac, or pulmonary disease be referred to a cardiologist for an evaluation including a graded exercise test to minimize the risk of injury, stroke and/or heart attack before starting at moderate or vigorous intensity exercise program (2). Patients should also be assessed for physical limitations and musculoskeletal conditions, which are especially common among preoperative patients (21). Patients with sensory, balance or gait deficits have an increased risk of injury. Patients experiencing activity-induced musculoskeletal pain are also at risk of further injury and will have a difficult time increasing their PA level if their pain is not addressed. Patients with such problems should be referred to physical therapy to learn rehabilitative exercises that will address their specific problems.

Advise

Following the assessment the clinician should educate the bariatric surgery patient on the benefits of regular PA, as well as help the patient develop realistic outcome expectations. For example, increasing one's PA improves cardiorespiratory fitness and weight loss maintenance, but will not eliminate loose sagging skin. Patients should also be taught about, PA-related safety concerns (see table 3), and general symptoms that warrant stoppage of activity and seeking of medical attention (e.g., nausea, light-headedness, difficulty breathing, cold or clammy skin, angina). However, it is just as important for the clinician to explain that some feelings of discomfort during and after PA are normal, especially when first starting a PA program. At the beginning of a workout the patient might feel dull aches as the blood flows to the muscles causing tissue to swell, and following a new workout routine a patient might feel tenderness from swelling or microtears in the muscle and connective tissue. However, as the body becomes accustomed to the new level of PA, discomfort lessons or resolves. Taking into consideration the assessment and relevant safety-related issues the clinician should formulate an appropriate PA program that suits the patient's attitude, needs and lifestyle. Long term goals, such as meeting PA guidelines for prevention of weight regain, are helpful. However, it is important to have several intermediate goals along the way that are clearly defined with specified type, duration, frequency and intensity.

Table 3.

Physical Activity-Related Safety Concerns for the Bariatric Surgery Patient

| Potential Risk | Description |

|---|---|

| Reduced heart rate and/or blood pressure | Patients may be taking medications that affect their exercise capacity. For example, heart medications, such as beta blockers and angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, lower resting heart rate. Thus, patients taking these medications should be given a lower heart rate target or instructed to use the talk test to monitor intensity. |

| Dehydration | Given their larger size and sweat rate bariatric surgery patients typically require more fluid during activity than nonobese adults. However, following surgery their fluid consumption is limited. Patients should be instructed to take frequent sips of water and exercise in cool temperatures when possible. |

| Susceptibility to specific injuries | Patients should be educated regarding surgery-related exercise restrictions. For example, resistance training exercises, particularly those targeting the abdominal and lower back regions, may not be appropriate for the first few months following surgery to allow for sufficient healing time. |

| Impaired balance or coordination | Rapid weight loss following surgery alters the body's center of gravity, which may affect patients' coordination and ability to balance. Thus, until weight has stabilized patients should be advised to be especially careful when performing exercises which require a significant degree of balance and coordination. |

| Catabolic state | Although rare, exercise paired with a post-surgery diet (i.e., fewer total calories with decreased carbohydrates and increased protein) may cause the body to shift into a catabolic state in which the body burns protein from muscle to meet energy requirements. Thus, patients should be forewarned about signs and symptoms (e.g., drossiness, lethargy) that should prompt them to seek medical help. |

Surgical patients will likely gain noticeable benefits from performing many types of activities. Emphasis should be placed on aerobic exercise, which yields the greatest health benefits, such as improving heart function and preventing cardiovascular disease, increasing endurance, and regulating body weight (38). Many health benefits can also be gained by adding strength training to the PA program. Specifically, strength training can improve muscular strength and endurance, which can improve ability to perform a wide variety of activities of daily living (e.g., carrying grocery bags, doing household chores), help correct posture and improve balance and coordination, prevent and help manage a variety of chronic medical conditions, and improve coronary risk factors (31). Strength training also has a positive effect on the composition and amount of muscle, subcutaneous abdominal adiposity, and bone. Flexibility exercises are also beneficial as they help patients increase their range of motion, thereby improving their physical function. However, strengthening and flexibility exercises should complement, rather than replace, a patient's aerobic PA.

Aerobic PA should be done in bouts of 10 minutes or longer (38). Thus, a goal of 60 minutes of MPA/day can be accomplished in as many as six ten-minute bouts. Exercising in short bouts may be a useful tactic for patients who have trouble finding a large block of time to exercise, or for patients who do not yet have the fitness required to sustain MPA for a long duration. In rare cases, severely deconditioned patients may not be able to sustain PA for at least 10 minutes. These patients should be advised according to their fitness and ability level. During a patient's first week of an exercise program it is better to have a patient successfully complete four 5-minute walking bouts per day than to attempt two 10-minute bouts and give up after the first one.

Most PA guidelines specify that activity should be done on “most” or “all” days of the week. Thus it is important to help patients understand that PA should become a part of their daily life. In addition, because some patients will have greater success meeting their PA goals by accumulating several shorter bouts of PA throughout the day, rather than one sustained effort, it is important to talk about frequency in terms of times per day and days per week.

While eventually patients should strive to exercise at moderate or vigorous intensity, when starting out patients should be encouraged to select a walking speed (or exertion level for other activities) that allows them to achieve their duration and frequency goals. When describing PA intensity to patients, it is important to explain that the same activity does not illicit the same physiological response in all individuals. For instance, although 2.5 mph is often cited as the minimum walking speed at which moderate intensity is achieved), obese adults may achieve MPA (as determined by their heart rate in reference to their maximum value and oxygen consumption in reference to their resting value) at much slower walking speeds (22). Thus, rather than telling patients to walk at a “brisk” pace, patients should be taught how to self-monitor their PA intensity, with the “Talk Test,” the Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion scale, or by monitoring their heart rate (40), and encouraged to do regular self-checks of their intensity to ensure they are exercising at their target intensity.

There is a growing body of literature supporting the importance of reducing sedentary time, even with low-intensity PA, as frequency and duration of movement appears to play a role in health outcomes such as achieving and maintaining a healthy weight (27). Thus, in addition to encouraging patients to stick with their scheduled exercise, patients should be encouraged to increase their incidental PA (e.g., use stairs instead of taking elevators). Patients should also be encouraged to decrease sedentary behaviors such as watching TV and using the computer.

Many bariatric surgery patients have difficulty complying with prescribed PA goals postoperatively (9). A recent observational study showed that a majority of postoperative patients did not intend to be active on most days during the week, and all patients had difficulty in achieving their intended amount of PA on the days that they were active (9). These findings highlight the challenges faced by patients in adopting a habitual PA program and the assistance that they require to identify and apply appropriate strategies for adhering to PA goals. The clinician can start by helping the patient select an appropriate activity. Considerations for selecting appropriate activities include range of motion, agility, balance, coordination, aerobic fitness and personal preference. Walking is often promoted as a practical and convenient way to exercise. However, those with significant pain or physical limitations may require activities with less impact, such as cycling or elliptical trainer. Aquatic exercises, which can be done alone (e.g., swimming laps, aqua jogging) or in group settings (e.g., water aerobics or water therapy classes) at gyms and community centers may also be sensible options, especially for patients with knee, hip, or back pain. Patients should also be reminded of at-home exercise options, such as exercise videos and television programs, which may be especially important during times of inclement weather, when walking outside is not feasible (40).

Common barriers to PA are perceived lack of time, childcare, support from family and friends, motivation, discipline, and/or self-management skills, enjoyment, and a safe and convenient environment to be active. Additional barriers to PA that may be more common among obese adults, and bariatric surgery patients in particular, are feeling too overweight to exercise, reduced aerobic capacity, excessive fatigue/dyspnea with low-level effort, musculoskeletal problems that hinder balance and mobility, body image dissatisfaction, and lack of confidence to be active (i.e., low self-efficacy) due to either lack of experience, past negative experiences, or fear of increasing musculoskeletal pain, getting injured, or having a cardiac event (40). Thus, it is important to help patients develop strategies for coping with perceived barriers and determine a PA plan that addresses their concerns. Table 4 provides examples of how to address unique physical and psychological barriers to PA of bariatric surgery patients.

Table 4.

Unique Physical and Psychological Barriers to Engaging in and Maintaining Regular Physical Activity among Severely Obese Bariatric Surgery Patients

| Barrier | Reason | Possible Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of confidence to go to a fitness facility or try group exercise classes |

|

|

| Excessive fatigue |

|

|

| Activity-indeced pain or impaired mobility |

|

|

| Fear of harming self (e.g., injury, heart attack) |

|

|

| Frustration with exercise guidelines |

|

|

Agree

Although the clinician should use his/her expertise to guide PA recommendations, it is important that the clinician and patient collaborate to agree upon the patients' specific PA goals, including type, duration, frequency and intensity of PA, and the time frame for goal evaluation and modification. In particular, the clinician should try to set at least one goal that the patient has a good chance of accomplishing, thereby increasing their sense of confidence and mastery, which may increase the likelihood of continuing to increase their PA level. Depending on the patients' readiness to increase their PA, it may be necessary to agree on more modest goals than would be ideal. However, PA adherence is poor when goals are not realistic or practical. Based on the collaborative process, the clinician and patient should develop a written exercise contract to reinforce a life-long commitment to exercise that consists of short-, mid- and long-term PA goals, a timeline and rewards for achievements, reasons for committing to an active lifestyle, and persons to provide support. Make a copy of the contract for the patient's file and for the patient to take home.

Assist

At the same time a patient signs an exercise contract, clinicians can further assist patients by providing printed materials and online resources that support counseling messages, as well as tools for self-monitoring PA, such as pedometers and PA diaries, and a list of community resources that support PA, including safe walking paths and local fitness facilities. In addition to material aid, patients should be taught behavioral strategies, such as developing social support, which will help them initiate and maintain their PA goals (see table 5). Patients needing additional guidance or encouragement to establish a PA routine should be encouraged to see an exercise specialist, such as a personal trainer or lifestyle coach, who can help patients improve their confidence, commitment and compliance. In addition, to prevent injuries, patients planning to initiate a strength training program should be encouraged to seek instruction from a qualified professional to learn proper technique. Such referrals are supported by the ASMBS's Allied Health Nutritional Guidelines, which recommends that surgical weight loss patients with barriers to PA be referred to appropriate professionals for specialized PA instruction (1).

Table 5.

Behavioral Strategies to Assist Bariatric Surgery Patients Increase and Sustain Physical Activity

| Strategy | Application |

|---|---|

| Goal-setting* | Help patient set incremental weekly goals that are specific, attainable, measurable, and based on patients' initial PA levels |

| Contracting* | Develop agreement consisting of short-, mid- and long-term goals that reinforces commitment to making permanent PA behavior change |

| Action planning and tailoring | Ask patients to plan when, where, and how PA will be accumulated throughout each day according to their schedule of activities |

| Self-monitoring | Provide patient with a pedometer to record daily steps or a diary to record structured PA min (≥ 10-min bouts) to establish baseline PA level and monitor progress |

| Problem-solving | Teach patients to apply problem-solving strategies (defining problem, brainstorming solutions, choosing, implementing, and evaluating best solution) to overcome barriers to exercise |

| Social support | Encourage patient to recruit an “exercise buddy,” enlist friends or family members to call and ask about progress toward PA goals, and to assist with childcare if needed |

| Stimulus control | Encourage patients to add cues to the external environment to promote PA (e.g., extra pair of walking shoes at work, reminder notes) and remove/avoid cues that promote sedentary behavior (e.g., avoid TV room, turn off computer after each use) |

| Reinforcement | Improve patients' self-efficacy through attainable short-term goals with a high likelihood of success Praise “small successes” and progress towards achievement of PA goals Help the patient identify external rewards for goal achievement (that support PA change) Increase awareness of internal rewards from PA |

Goal-setting and contracting should first be introduced during the Advise and Agree segments of PA counseling, and then reviewed and revised as necessary when Assisting patients at future appointments.

Arrange

An effective PA counseling programs requires multiple contacts and ongoing support. A week or two after an initial PA counseling session the clinician or an assistant should follow-up with the patient by phone to answer questions and provide reinforcement for progress towards PA goals. The clinician should also advise the patient to schedule an in-person follow-up visit to discuss attainment of goals, and revise the treatment plan as needed. Lack of immediate behavior change does not indicate that PA counseling is ineffective; some patients will require several prompts to change their PA behavior. Thus, it is important to offer PA counseling to patients throughout their pre- and postoperative care, so that when patients are ready to make a commitment to improving their health through PA, they have the assistance they need. Similarly, patients who are struggling to meet goals should be reminded that behavior change often takes several attempts and that renewed effort with a focus on overcoming past barriers can lead to success.

There are several books and online resources specific to implementing routine PA counseling into clinical care, including educational material for clinicians and patients, and tools to assess PA level and need for further testing prior to initiating a PA program (26). Using written material, such as the Clinician's Guide to Providing PA Counseling to the Bariatric Surgery Patient (see table 6), during PA counseling will provide structure and facilitate time effective counseling sessions.

Table 6.

Clinician's Guide to Providing Physical Activity Counseling to the Bariatric Surgery Patient

| Assess | • Patient's knowledge, beliefs and values regarding physical activity (PA) |

| • PA history, current PA level and PA preferences | |

| • Readiness to change, motivation, self-confidence and barriers to implementing a PA program | |

| • PA, physical function and general health goals | |

| • Physical limitations and pain associated with PA; refer to physical therapy as needed | |

| • Patient's ability to safely increase PA; refer high-risk patients for exercise testing | |

|

| |

| Advise | • Enhance motivation by summarizing the benefits of PA |

| • Help patient develop realistic expectations | |

| • Discuss safety-related issues and provide guidance on how to minimize risks (table 3) | |

| • Provide strategies on how to overcome barriers to PA (table 4) | |

| • Teach patients how to gauge their PA intensity | |

| • Tailor PA recommendations to the patients' capabilities and readiness | |

|

| |

| Agree | • Collaborate with patient to determine specific PA goals (including type, duration, frequency and intensity) and the time frame for goal evaluation and modification |

| • Provide written exercise contract including short-, mid- and long-term goals (include copies in medical file) | |

|

| |

| Assist | • Teach patient behavioral strategies to be successful (see table 5) |

| • Provide printed material and online resources that support counseling messages | |

| • Provide tools for self-monitoring PA such as pedometers and PA diaries | |

| • Provide list of community resources for participating in PA, including safe walking paths | |

| • Refer patients to exercise specialists as needed | |

|

| |

| Arrange | • Share patient's PA plan with clinic staff/members of the bariatric team to establish team consensus and commitment |

| • Schedule follow-up contacts (in-person or over the phone) to answer questions, discuss attainment of goals, provide positive reinforcement for progress towards goals, and revise treatment plan as needed | |

| • Provide ongoing PA counseling at future appointments | |

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Although evidence is mounting to support the role of PA in weight loss and other outcomes following bariatric surgery, this is a relatively new area of study with much work to be done. Future work should investigate how varying type, intensity, duration and frequency of PA affects weight loss and other surgical outcomes. In addition, work is needed to determine the most effective strategies for helping surgical patients increase and maintain higher PA levels. In particular RCTs are needed to determine the most effective approaches to PA counseling (e.g., behavioral strategies, supervised exercise, referral to community programs), modes of delivery (e.g., in person or internet-based; individual or group counseling), and dose of counseling (i.e., weekly for 2 months vs. monthly for 2 years). Research is also needed to inform how the timing of PA counseling (i.e. pre, peri- or postoperatively) affects compliance and if and how the dosage of recommended PA should vary in relation to the various stages related to surgery (i.e. preparation for surgery, recovery from surgery, active weight loss, and weight maintenance).

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Evidence is mounting that increasing PA pre- to postoperatively and higher postoperative PA level are associated with greater weight loss, improved body composition, and improved fitness following surgery. Prior to surgery the majority of bariatric surgery patients are highly sedentary and inactive. Many patients report an increase in their PA postoperatively, but objective PA monitoring suggests the majority of them do not meet PA guidelines for general health, weight loss or weight maintenance, and some actually become less active. To help patients maximize weight loss and other health benefits following bariatric surgery, patients need more PA encouragement and support before and following surgery. While there is much work to be done to determine the most effective way to help patients achieve an active lifestyle, recent evidence suggests that with support inactive patients can become sufficiently active and improve their surgical outcomes. By using proven PA counseling strategies, including following the five A's, tailored to bariatric surgery patients, clinicians can do their part to increase the PA level of patients during all phases of their care, including providing referrals for exercise testing, physical therapy and an exercise specialist as indicated. While meeting PA recommendations for weight maintenance (e.g. 60–90 minutes MVPA/day) is an appropriate long-term goal for most patients, clinicians should help patients set realistic, attainable, measurable short-term goals, and gradually increase the amount and intensity of PA over time.

Acknowledgments

Funding Dr. King is in part supported by National Institutes of Health U01 DK066557. Dr. Bond is supported by National Institutes of Health Grant K01-DK083438.

Footnotes

Disclosure The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Allied Health Sciences Section Ad Hoc Nutrition Committee. Aills L, Blankenship J, Buffington C, Furtado M, Parrott J. ASMBS Allied Health Nutritional Guidelines for the Surgical Weight Loss Patient. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008 Sep-Oct;4(5 Suppl):S73–108. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American College of Sports Medicine . ACSM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. Seventh Edition Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.American College of Surgeons ACS Bariatric Surgery Center Network Accreditation Program. (ACS BSCN) [Accessed February 8, 2012];Bariatric accreditation program manual. Available at http://www.cms.gov/determinationprocess/downloads/id160c.pdf.

- 4.American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery [Accessed Feb 2, 2012];ASMBS Public and Professional Education Committee Bariatric Surgery: Postoperative Concerns. Available at: http://s3.amazonaws.com/publicASMBS/GuidelinesStatements/Guidelines/asbs_bspc.pdf.

- 5.Blackburn GL, Hutter MM, Harvey AM, et al. Expert panel on weight loss surgery: executive report update. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009 May;17(5):842–62. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bond DS. Bari-Active: A preoperative intervention to increase physical activity. Obes Surg. 2011;21(8):1042. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bond DS, Jakicic JM, Unick JL, et al. Pre- to postoperative physical activity changes in bariatric surgery patients: self report vs. objective measures. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18(12):2395–2397. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bond DS, Jakicic JM, Vithiananthan S, et al. Objective quantification of physical activity in bariatric surgery candidates and normal-weight controls. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6(1):72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2009.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bond DS, Thomas JG, Ryder BA, Vithiananthan S, Pohl D, Wing RR. Ecological momentary assessment of the relationship between intention and physical activity behavior in bariatric surgery patients. Int J Behav Med. 2011 Dec 28; doi: 10.1007/s12529-011-9214-1. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bond DS, Unick JL, Jakicic JM, et al. Objective assessment of time spent being sedentary in bariatric surgery candidates. Obes Surg. 2011;21:811–814. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0151-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colles SL, Dixon JB, O'Brien PE. Hunger control and regular physical activity facilitate weight loss after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Obes Surg. 2008;18(7):833–840. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9409-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donnelly JE, Blair SN, Jakicic JM, Manore MM, Rankin JW, Smith BK, American College of Sports Medicine American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand. Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009 Feb;41(2):459–71. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181949333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunn AL, Marcus BH, Kampert JB, Garcia ME, Kohl HW, 3rd, Blair SN. Comparison of lifestyle and structured interventions to increase physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness: a randomized trial. JAMA. 1999 Jan 27;281(4):327–34. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.4.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Egberts K, Brown WA, O'Brien PE. Optimising lifestyle factors to achieve weight loss in surgical patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011 SFR-111. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eldar S, Heneghan HM, Brethauer SA, Schauer PR. Bariatric surgery for treatment of obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011 Sep;35(Suppl 3):S16–21. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Institute of Medicine . Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (macronutrients) National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Josbeno DA, Jakicic JM, Hergenroeder A, Eid GM. Physical activity and physical function changes in obese individuals after gastric bypass surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6(4):361–6. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Josbeno DA, Kalarchian M, Sparto PJ, Otto AD, Jakicic JM. Physical activity and physical function in individuals post-bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2011 Aug;21(8):1243–9. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0327-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobi D, Ciangura C, Couet C, Oppert JM. Physical activity and weight loss following bariatric surgery. Obes Rev. 2010;12(5):366–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.King WC, Belle SH, Eid GM, et al. Physical activity levels of patients undergoing bariatric surgery in the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4(6):721–728. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King WC, Engel SG, Elder KA, et al. Walking capacity of bariatric surgery candidates. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012 Jan-Feb;8(1):48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King WC, Hames K, Goodpaster B. BMI predicts walking speed at which moderate-intensity physical activity is achieved. MSSE. 2010 May;42(5):S514. [Google Scholar]

- 23.King WC, Hsu JY, Belle SH, et al. Pre- to postoperative changes in physical activity: report from the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery-2. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011 Aug 16; doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2011.07.018. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCullough PA, Gallagher MJ, Dejong AT, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and short-term complications after bariatric surgery. Chest. 2006 Aug;130(2):517–25. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.2.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mechanick JI, Kushner RF, Sugerman HJ, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists; Obesity Society; American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery medical guidelines for clinical practice for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009 Apr;17(Suppl 1):S1–70. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.28. v. Erratum in: Obesity (Silver Spring). 2010 Mar;18(3):649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meriwether RA, Lee JA, Lafleur AS, Wiseman P. Physical activity counseling. Am Fam Physician. 2008 Apr 15;77(8):1129–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Owen N, Healy GN, Matthews CE, Dunstan DW. Too much sitting: the population health science of sedentary behavior. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2010;38(3):105–113. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e3181e373a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peacock JC, Zizzi SJ. Survey of bariatric surgical patients' experiences with behavioral and psychological services. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011 Dec 8; doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2011.11.015. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pi-Sunyer X. The medical risks of obesity. Postgrad Med. 2009;121:21–33. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2009.11.2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poirier P, Cornier MA, Mazzone T, et al. American Heart Association Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Bariatric surgery and cardiovascular risk factors: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011 Apr 19;123(15):1683–701. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182149099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pollock ML, Franklin BA, Balady GJ, et al. AHA Science Advisory Resistance exercise in individuals with and without cardiovascular disease: benefits, rationale, safety, and prescription: An advisory from the Committee on Exercise, Rehabilitation, and Prevention, Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association; Position paper endorsed by the American College of Sports Medicine. Circulation. 2000 Feb 22;101(7):828–33. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.7.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saris WH, Blair SN, van Baak MA, et al. How much physical activity is enough to prevent unhealthy weight gain? Outcome of the IASO 1st Stock Conference and consensus statement. Obes Rev. 2003 May;4(2):101–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2003.00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shah M, Snell PG, Rao S, et al. High-volume exercise program in obese bariatric surgery patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011 Sep;19(9):1826–34. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simkin-Silverman LR, Conroy M, King WC. Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Primary Care Practice: Current Evidence and Future Directions. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 2008 Jul;2:296–304. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sjostrom L, Narbro K, Sjostrom CD, et al. Swedish Obese Subjects Study. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:741–752. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas JG, Bond DS, Sarwer DB, Wing RR. Technology for behavioral assessment and intervention in bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011;7(4):548–557. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [Accessed February 10, 2012];2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Available at: http://www.health.gov/paguidelines/pdf/paguide.pdf.

- 38.Wing RR. Physical activity for weight loss maintenance. In: Bouchard C, Katzmarzyk PT, editors. Physical Activity and Obesity. 2nd edition Human Kinetics; Champaign: 2010. pp. 245–247. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Whitlock EP, Orleans CT, Pender N, Allan J. Evaluating primary care behavioral counseling interventions: an evidence-based approach. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22(4):267–284. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00415-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zunker C, King WC. Psychosocial Assessment and Treatment of Bariatric Surgery Patients. Psychology Press and Routledge, part of the Taylor and Francis Group; London: 2012. Physical Activity Pre- and Post Bariatric Surgery; pp. 131–158. [Google Scholar]