Abstract

Crypt abscesses caused by excessive neutrophil accumulation are prominent features of human campylobacteriosis and its associated pathology. The molecular and cellular events responsible for this pathological situation are currently unknown. We investigated the contribution of PI3Kγ signaling in Campylobacter jejuni-induced neutrophil accumulation and intestinal inflammation. Germ-free and specific pathogen free Il10−/−and germ-free Il10−/−; Rag2−/− mice were infected with C. jejuni (109 CFU/mouse). PI3Kγ signaling was manipulated using either the pharmacological PI3Kγ inhibitor AS252424 (i.p. 10 mg/kg daily) or genetically using Pi3γ−/− mice. After up to 14 days, inflammation was assessed histologically and by measuring levels of colonic Il1β, Cxcl2 and Il17a mRNA. Neutrophils were depleted using anti-Gr1 antibody (i.p. 0.5 mg/mouse/every 3 days). Using germ-free Il10−/−; Rag2−/− mice, we observed that innate immune cells are the main cellular compartment responsible for campylobacteriosis. Pharmacological blockade of PI3Kγ signaling diminished C. jejuni-induced intestinal inflammation, neutrophil accumulation and NF-κB activity, which correlated with reduced Il1β (77%), Cxcl2 (73%) and Il17a (72%) mRNA accumulation. Moreover, Pi3kγ−/− mice pretreated with anti-IL-10R were resistant to C. jejuni-induced intestinal inflammation compared to Wt mice. This improvement was accompanied by a reduction of C. jejuni translocation into the colon and extra-intestinal tissues and by attenuation of neutrophil migratory capacity. Furthermore, neutrophil depletion attenuated C. jejuni-induced crypt abscesses and intestinal inflammation. Our findings indicate that C. jejuni-induced PI3Kγ signaling mediates neutrophil recruitment and intestinal inflammation in Il10−/− mice. Selective pharmacological inhibition of PI3Kγ may represent a novel means to alleviate severe cases of campylobacteriosis, especially in antibiotic-resistant strains.

Keywords: Innate immunity, NF-κB, inflammation, enteric infection, crypt abscesses

INTRODUCTION

Campylobacter jejuni is the leading cause of food borne bacterial infection worldwide and has a prevalence of 14 laboratory-confirmed cases/100,000 persons in 2011 in the United States (1). This infection rate is the second highest incidence and higher than the following eight most common pathogens combined ( 9.1/100,000) (1). Symptoms of Campylobacter infection are generally self-limited and include diarrhea, abdominal cramps and fever (2). However, severe cases involving bloody diarrhea, prolonged fever and severe cramping require antibiotic treatment. Importantly, campylobacteriosis is associated with development of extra-intestinal sequelae such as Guillain-Barre Syndrome (3), reactive arthritis(4), relapse of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD)(5) and post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome (6). These numerous sequelae in conjunction with increased resistance to antibiotic treatment position campylobacter an important enteric pathogen and demand an improvement in both prevention and management (7, 8). Although campylobacteriosis represents a major health concern in both the developing and industrialized world, our understanding of the basic molecular and cellular events associated with Campylobacter infection is rather primitive compared to other pathogens with less prevalence (Shigella, Escherichia, Vibrio, Listeria) (9). This gap of knowledge is in stark contrast with the relatively well characterized molecular genetic information of the bacterium. Indeed, the publication of various campylobacter genomes, included C. jejuni 81–176 has contributed to a better understanding of the microbial genetic elements controlling growth, survival and fitness (10, 11). Our limited understanding of Campylobacter pathogenesis likely stems from the poor availability of murine models. We and others have recently showed that Il10−/− mice represent a powerful model to study colonization, infection, bacterial translocation and inflammatory responses (12–14). Moreover, a recent study showed that the colon of C. jejuni infected Il10−/− mice showed increased expression of the chemoattractant Cxcl2 which correlates with the formation of numerous crypt abscesses and neutrophil infiltration, a phenotype commonly observed in human campylobacteriosis (13, 15). Similarly, CXCL-2 mediates neutrophil recruitment into intestinal payer’s patches (PP) and MLN in Salmonella-infected mice (16), therefore this chemokine may play an important role in campylobacteriosis.

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases (PI3Ks) are a large family of signaling proteins formed by a catalytic subunit and a regulatory subunit. These signaling proteins are grouped into three different classes (I, II and III) and are implicated in the regulation of cell growth, proliferation, differentiation, survival and motility (17). In addition, a number of recent reports implicate various PI3K proteins in innate and adaptive immunity (17, 18). PI3Kγ is a class I B PI3K and comprises a catalytic subunit (p110γ) and a regulatory subunit (p101 or p84). PI3Kγ is mainly expressed in immune cells and mediates chemoattractant-induced cell migration by controlling actin cytoskeletal rearrangement through G-protein coupled receptors (19, 20). Interestingly, neutrophils isolated from Pi3kγ−/− mice show impaired migration towards N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP) due to reduced F-actin accumulation at the cell’s leading edge (21). In addition, Pi3kγ−/− mice injected i.p. with Listeria exhibited reduced neutrophil accumulation into the peritonea compared to Wt mice (20).

We recently found that C. jejuni induced intestinal inflammation is associated with neutrophil infiltration (13), although the functional impact and molecular events leading to this response remained elusive. In present study, we hypothesized that neutrophil recruitment into intestinal crypts and the associated tissue destruction observed in C. jejuni infected hosts are mediated through PI3Kγ signaling and neutrophil recruitment. Using pharmacological and genetic approaches, we demonstrated that PI3Kγ signaling promotes C. jejuni-induced colitis by regulating the influx of neutrophils into intestinal crypts. This signaling pathway may represent a new therapeutic target for campylobacteriosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and tissue processing

All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Germ-free 8–12 week-old Il10−/−; NF-κBEGFP (129/SvEv; C57BL/6 mixed background), Il10−/− and Il10−/−; Rag2−/− mice (129/SvEv) were transferred from germ-free isolators and immediately gavaged with a single dose of 109 C. jejuni cfu/mouse (strain 81–176(22)) and sacrificed after up to 14 days as described previously (13). Specific pathogen free (SPF) housed Wt, Il10−/− and Pi3kγ−/− (20) mice (generous gift of Dr. Emilio Hirsch, Univerisity of Torino, Italy) all on a 129/SvEv background were gavaged 109 C. jejuni cfu/mouse one day after 7 day treatment with antibiotics cocktail (streptomycin 2 g/L, gentamycin 0.5 g/L, bacteriocin 1 g/L and ciprofloxacin 0.125 g/L) (13). To inhibit PI3K and PI3Kγ signaling, mice were i.p. injected daily with wortmannin (1.4 mg/kg; Fisher Scientific) and AS252424 (10 mg/kg; Cayman Chemical), respectively. Tissue samples from colon, spleen, and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) were collected for protein, RNA, histology and C. jejuni culture assays as described previously (13). Histological images were acquired using a DP71 camera and DP Controller 3.1.1.276 (Olympus), and intestinal inflammation was scored on a scale of 0 – 4 as described before (12, 13). Neutrophils in colonic tissues were identified based on morphological features using H&E stained sections and counted in 5 fields of view/mouse using a microscope. Data were expressed as average counts/mouse.

Neutrophil depletion and IL-10 receptor blockade

Il10 −/−; NF-κBEGFP mice were infected with C. jejuni and injected with anti-Gr1 antibody (i.p. 0.5 mg/mouse, at D0 and D3; clone: RB6-8C5; BioXcell) for 6 days to deplete neutrophil as described in a previous reports (23). We selected a 6 day experimental time instead of the typical 12 days because neutrophil depletion is less effective after 6 days (Sun and Jobin, personal observation). To block IL-10 signaling, antibiotic treated and C. jejuni infected Wt and Pi3kγ−/− mice were injected with anti-IL-10R antibody (i.p. 0.5 mg/mouse, every 3 days; Clone: 1B1.3A;BioXcell) for 14 days as described (24). At the end of the experiment, mice were euthanized using CO2 intoxication and death was ensured by performing cervical dislocation. Colons were resected and processed for H&E staining and colitis evaluation.

Western blotting

A segment of the distal colon was lysed in 300 μl Laemmli buffer, homogenized and heated at 95 °C for 5 min. 20 μg of total protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Targeted protein was detected using enhanced chemiluminescence reaction (ECL) as described previously (25). Primary antibodies used were phosphor-AKT (S473), phosphor-p70S6K (T389), total AKT (all from Cell Signaling) and EGFP (Sigma). The density of Western blot bands was quantified using ImageJ and data were normalized to total AKT control.

Neutrophil isolation and migration assay

Neutrophils from the peripheral blood were isolated as described (26). Briefly, blood (~1 ml/mouse, 8 mice/group) from Wt and Pi3k−/− mice was collected in 5mM EDTA by cardiac puncture. The blood was diluted with 0.15M NaCl, loaded on a single layer of 69.2% Percoll and centrifuged at 1500× g for 20 min at room temperature. Neutrophils were recovered at the bottom layer of the gradients, and contaminating erythrocytes were lysed by hypotonic shock. Neutrophil purity was assessed using Wright-Giemsa staining and was found to be > 98 %. Cell migration assay was performed immediately after purification. A total of 5×105 neutrophils were added in the top chamber of a Transwells (12 wells with 3 μm pore; Corning Inc., Corning, NY) and CXCL-2 (250 ng/mL; R&D Systems) was added to the bottom wells. RMPI 1640 medium without CXCL-2 was used as a negative control. Transwells were then incubated for 2 h in humidified air and 5% CO2. Neutrophils migrated into the bottom wells were imaged using a DP71 camera and DP Controller 3.1.1.276 (Olympus) and enumerated using a hemocytometer (Sigma-Aldrich). Cell viability was more than 95% as judged by trypan blue exclusion.

Enhanced GFP (EGFP) macro-imaging

Following infection and various treatment, Il10 −/−; NF-κBEGFP mice were sacrificed, and the colon and cecum were removed and immediately imaged using a charge-coupled device camera in a light-tight imaging box with a dual-filtered light source and emission filters specific for EGFP (LT-99D2 Illumatools; Lightools Research).

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

Cy3-tagged 5′AGCTAACCACACCTTATACCG3′ was used to probe the presence of C. jejuni in the intestinal tissue sections as previously described (13). Briefly, tissues were deparaffinized, hybridized with the probe, washed, mounted in DAPI medium and imaged using a Zeiss LSM710 Spectral Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope system with ZEN 2008 software. Acquired images were analyzed using BioimageXD (27).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Neutrophils in intestinal tissue were detected using anti-myeloperoxidase (MPO) IHC as described previously (13). Briefly, intestinal tissue sections were deparaffinized, blocked and incubated with an anti-MPO antibody (1:400; Thermo Scientific) overnight. After incubation with anti-rabbit biotinylated antibody, ABC (Vectastain ABC Elite Kit, Vector Laboratories), DAB (Dako) and hematoxylin (Fisher Scientific), the sections were imaged on an Olympus microscope using DP 71 camera and DP Controller 3.1.1.276 (Olympus).

C. jejuni quantification in tissues

MLN and spleen were aseptically resected. Colon tissue was opened, resected and washed three times in sterile PBS. The tissues were weighed, homogenized in PBS, serially diluted and plated on Campylobacter selective blood plates (Remel) for 48 h at 37 °C using the GasPak system (BD). C. jejuni colonies were counted and data presented as colony forming unit (cfu)/g tissue.

Real time RT-PCR

Total RNA from intestinal tissues was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen) following the manufacture’s guide. cDNA was reverse-transcribed using M-MLV (Invitrogen). Proinflammatory Il1β, Cxcl2, Il17a and Tnfα mRNA expression levels were measured using SYBR Green PCR Master mix (Applied Biosystems) on an ABI 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System and normalized to Gapdh. The PCR primers used were reported previously.(13) The PCR reactions were performed for 40 cycles according to the manufacturer’s recommendation, and RNA fold changes were calculated using the ΔΔct method.

Primary splenocyte isolation and C. jejuni infection

Splenocytes were isolated as described previously.13 Briefly, Wt and Pi3kγ−/− mice (8–12 wk-old) were sacrificed, spleens were resected and homogenized in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2mM L-glutamine and 50μM 2-mercaptoethanol. Red blood cells were lysed, and cells were filtered through a 70 μm strainer, centrifuged, resuspended in the2% FBS RPMI 1640 medium and plated at 1×106 cells/well in 6-well plates. Cells were infected with C. jejuni (MOI 50) for 4h in triplicates. Cells were then collected by centrifugation and lysed in TRIzol (Invitrogen) for RNA extraction.

C. jejuni epithelial cell translocation assay

Murine rectal carcinoma epithelial CMT-93 cells (1×106) were plated onto 12-well Transwells (Corning Inc., Corning, NY) in DMEM media containing 10% FBS and 2mM L-glutamine. Upon reached confluency (monolayer), the medium was changed to 1% FBS medium and 108 C. jejuni was added to the upper inserts in presence or absence of 10 μM AS252424. Aliquot of medium from bottom wells was collected every hr for 5 hrs, serially diluted and cultured on Remel plates as described before (13). Translocated C. jejuni was reported as CFU/ml at each time point.

Statistical analysis

Values are shown as mean ± SEM as indicated. Differences between groups were analyzed using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. Experiments were considered statistically significant if P values < 0.05. All calculations were performed using Prism 5.0 software.

RESULTS

Innate immune cells mediate C. jejuni-induced colitis

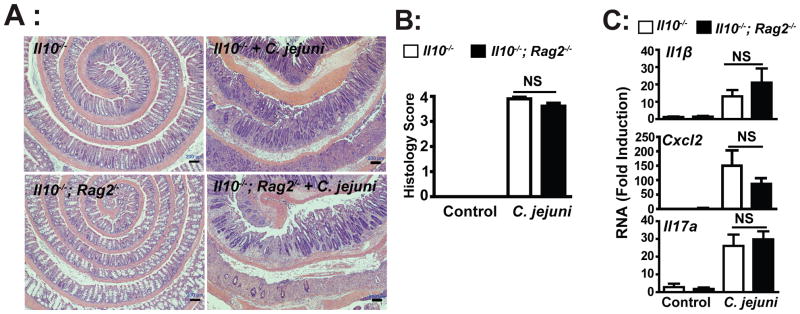

We have previously demonstrated using antibody depletion approach that C. jejuni-induced colitis in Il10−/− mice is CD4 independent (13). To further establish the role of innate and adaptive immunity in campylobacteriosis, we utilized germ-free Il10−/−; Rag2−/−mice. Germ-free Il10−/− and Il10−/−; Rag2−/− mice were transferred to specific pathogen free (SPF) housing and immediately gavaged with a single dose of C. jejuni (109 CFU/mouse). After 12 days, as previously reported, C. jejuni induced severe intestinal inflammation in Il10−/− mice as showed by extensive immune cell infiltration, epithelial damage, goblet cell depletion and crypt hyperplasia and abscesses compared to uninfected mice (Figures 1A-B). Interestingly, the absence of T and B cells did not impact the severity of colitis, as C. jejuni-infected Il10−/−; Rag2−/− and Il10−/− mice developed comparable levels of intestinal inflammation. Similarly, C. jejuni-induced I11β, Cxcl2 and Il17a mRNA accumulation was not significantly different between Il10−/−; Rag2−/− and Il10−/− mice (Figure 1C). Altogether, these observations indicate that C. jejuni-induced intestinal inflammation is predominantly mediated by innate immune cells during the early onset of campylobacteriosis (12 days).

Figure 1. Innate immune cells mediate C. jejuni induced colitis in Il10−/− mice.

Cohorts of 4–7 germ-free Il10−/− and Il10−/−; Rag2−/− mice were transferred to SPF conditions and immediately gavaged with a single dose of 109 C. jejuni/mouse. After 12 days, colons were resected for formalin-fixation, sectioning and H&E staining, or RNA extraction for gene expression analysis. (A) Histological intestinal damage scores of C. jejuni-induced inflammation in Il10−/− and Il10−/−; Rag2−/− mice. (B) Quantification of histological intestinal damage score mediated by C. jejuni infection. (C) Il1β, Cxcl2 and Il17a mRNA accumulation was quantified using an ABI 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System and specific primers and data were normalized to Gapdh. All graphs depict mean ± SEM. NS, P > 0.05. Scale bar is 200 μm. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

PI3K signaling mediates C. jejuni-induced colitis

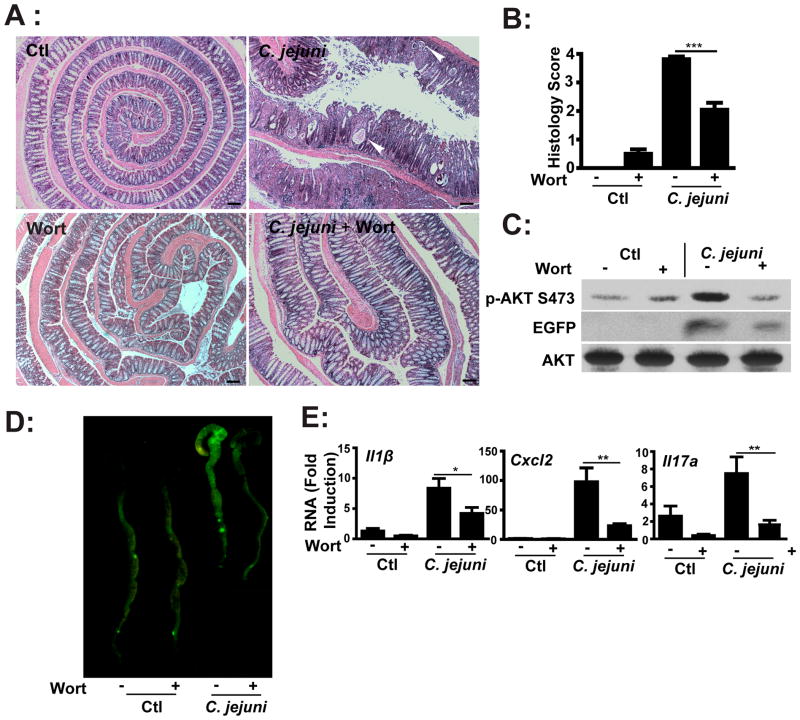

We previously showed that mTOR mediates C. jejuni-induced colitis (13) and since PI3K signaling is a potential upstream regulators of mTOR, we hypothesized that this pathway plays an important role in campylobacteriosis. To test this hypothesis, C. jejuni-infected germ-free Il10−/−; NF-κBEGFP mice were i.p. injected daily with either vehicle (5% DMSO PBS) or with the pharmacological PI3K pan-inhibitor wortmannin (1.4 mg/kg body weight) for 12 days. As seen in Figures 2A–B, C. jejuni-induced colitis and crypt abscesses were reduced in wortmannin-treated mice compared to vehicle-treated mice. Western blot analysis demonstrated reduction of C. jejuni-induced Akt phosphorylation (S473) in colonic lysates from wortmannin-treated, C. jejuni-infected mice (Figure 2C). Moreover, C. jejuni-induced AKT phosphorylation (S473) in colonic lysates was not impaired in Il10−/−; Rag2−/− mice, suggesting that lymphocytes are not the main contributor of Akt phosphorylation (Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 2. PI3K signaling pathway mediates C. jejuni-induced intestinal inflammation in Il10−/−; NF-κBEGFP mice.

Four cohorts of 4–8 germ-free Il10−/−; NF-κBEGFP mice were transferred to SPF conditions and immediately gavaged with a single dose of C. jejuni (109/mouse) and then i.p. injected with vehicle control (Ctl, 5% DMSO), wortmannin (wort, 1.4 mg/kg body weight) daily for 12 days. (A) H&E representation of intestinal damage. Arrow heads indicate crypt abscesses. (B) Quantification of intestinal inflammation as histological score. (C) Western blot for total and phosphorylated (S473) AKT and EGFP protein levels in pooled colonic lysates of infected mice. (D) Colonic EGFP expression levels were visualized using a CCD camera macroimaging system. (E) Il1β, Cxcl2 and Il17a mRNA accumulation was quantified using real time PCR. All graphs depict mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01, ***, P < 0.001. Scale bar is 200 μm. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

To evaluate whole body transcriptional response, we infected Il10−/−; NF-κBEGFP mice with C. jejuni and determined the level of NF-κB-driven EGFP expression. C. jejuni-induced colonic EGFP expression in Il10−/−; NF-κBEGFP mice was attenuated in wortmannin-treated mice compared to vehicle-treated mice (Figures 2C–D). In addition, wortmannin blocked C. jejuni-induced NF-κB dependent I11β, Cxcl2 and Il17a mRNA accumulation by 50%, 77% and 78% respectively in Il10−/−; NF-κBEGFP mice compared to vehicle-treated, infected mice (Figure 2E). These findings indicate that PI3K signaling is involved in C. jejuni-mediated intestinal inflammation.

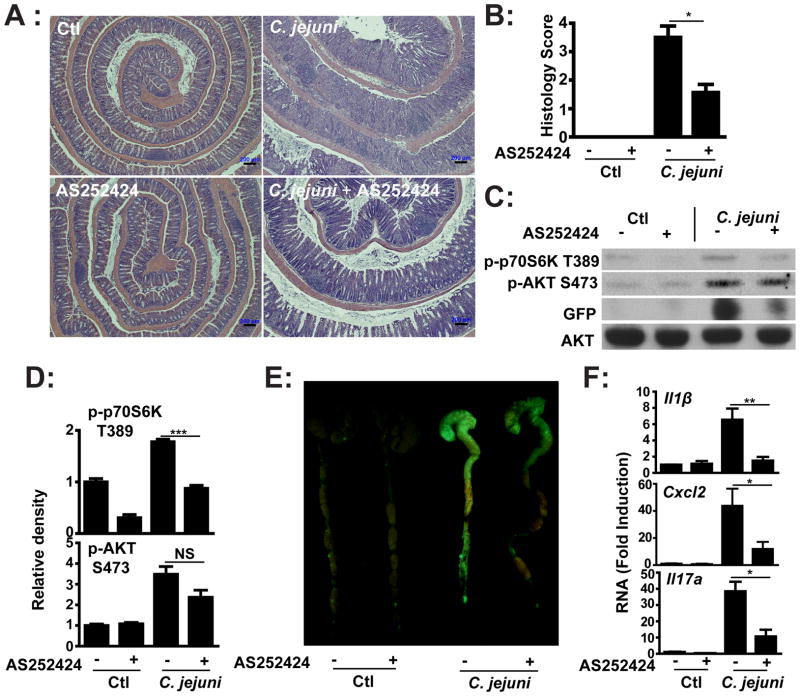

PI3Kγ mediates C. jejuni-induced colitis

Since neutrophil infiltration and crypt abscesses are hallmarks of campylobacteriosis in both human and in the Il10−/− murine model (13, 15), we speculated that signal-induced neutrophil recruitment/activation would be important in host pathogenesis. Among PI3K family members, the class I B PI3Kγ has been implicated in leukocyte migration and activation. To establish the role of PI3Kγ in campylobacteriosis, germ-free Il10−/−; NF-κBEGFP mice were gavaged with a single dose of C. jejuni (109 CFU/mouse) and i.p. injected daily with PI3Kγ specific inhibitor AS252424 (10 mg/kg body weight) or vehicle control (5% DMSO PBS) for 6 days. Interestingly, C. jejuni-induced colitis was reduced in AS252424-treated Il10−/−; NF-κBEGFP mice compared to vehicle-treated mice (Figure 3A–B). Western blot analysis (Figure 3C) demonstrated a modest reduction (Figure 3D) of AKT phosphorylation (S473) but an evident attenuation (34%) of p70S6K phosphorylation (T389) in colonic extracts from AS252424-treated, C. jejuni-infected Il10−/−; NF-κBEGFP mice. In addition, induction of EGFP expression (NF-κB activity) in the colon of C. jejuni infected Il10−/−; NF-κBEGFP mice was reduced in AS252424-treated mice compared to control vehicle-treated mice (Figures 3C–D). We next examined the impact of PI3Kγ on expression of NF-κB-dependent proinflammatory mediators involved in bacterial host responses. AS252424 treatment blocked C. jejuni-induced I11β, Cxcl2 and Il17a mRNA accumulation by 77%, 73% and 72% respectively compared to vehicle-treated, infected Il10−/−; NF-κBEGFP mice (Figure 3E).

Figure 3. Pharmacological inhibition of PI3Kγ blocks C. jejuni-induced intestinal inflammation in Il10−/−; NF-κBEGFP mice.

Four cohorts of 4–6 germ-free Il10−/−; NF-κBEGFP mice were transferred to SPF conditions and infected with C. jejuni as described in Figure1. Mice were i.p. injected with vehicle (5% DMSO) or pharmacological PI3Kγ inhibitor AS252424 (10 mg/kg body weight) daily for 6 days. (A) H&E representation of intestinal inflammation. (B) Quantitative histological score of intestinal inflammation. (C) Western blot for total and phosphorylated (S473) AKT, phosphorylated p70S6K (T389) and EGFP protein levels in pooled colonic lysates of infected mice. (D) Density of Western blot bands was quantified using ImageJ and normalized to control. (E) Colonic EGFP expression levels were visualized using a CCD camera macroimaging system. (F) Il1β, Cxcl2 and Il17a mRNA accumulation was quantified by real time PCR. All graphs depict mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01, NS, not significant. Scale bar is 200 μm. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

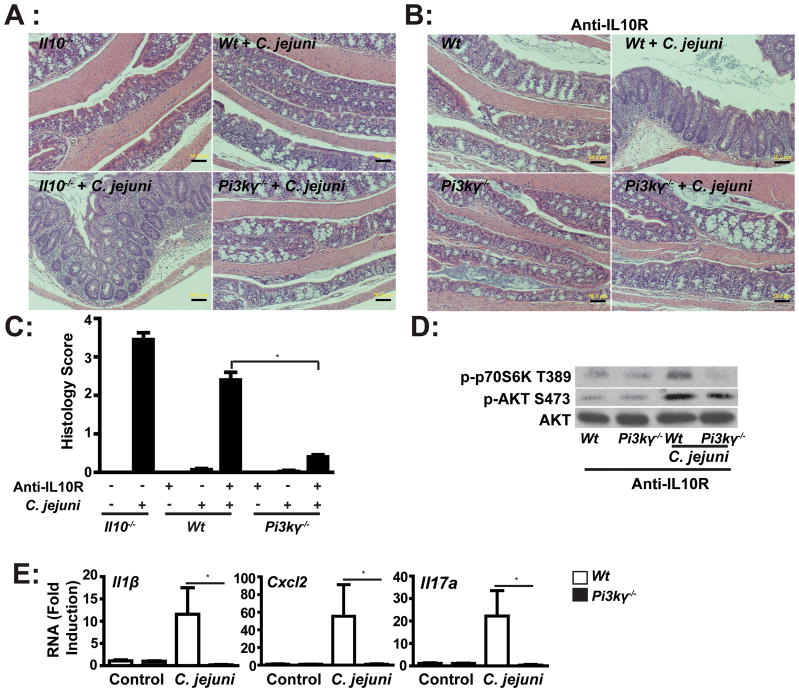

To gain specificity over the pharmacological targeting approach, we next utilized Pi3kγ−/−mice. Antibiotic treatment has been shown to enhance C. jejuni colonization in Wt mice (13). Interestingly, antibiotic-treated Il10−/− mice displayed severe colitis at 2 weeks, but antibiotic-treated SPF Wt and Pi3kγ−/− mice were resistant to C. jejuni induced colitis (Figures 4A and C). To enhance susceptibility of Wt and Pi3kγ−/− mice to C. jejuni-induced colitis, we emulated the Il10 knockout phenotype by using an antibody blocking the IL-10 receptor (IL-10R). Antibiotic-treated Wt and Pi3kγ−/− mice were gavaged with C. jejuni and then i.p. injected with anti-IL-10R antibody (500μg/mouse) every 3 days for 2 weeks. As predicted, anti-IL-10R-treated Wt mice developed colitis following C. jejuni infection, albeit to a slightly lower extent than Il10−/− mice (Figures 4B–C). In agreement with our pharmacologic studies, C. jejuni-induced intestinal inflammation was strongly attenuated in anti-IL-10R-treated Pi3kγ−/− mice compared to anti-IL-10R-treated Wt mice. No evidence of intestinal inflammation was observed in uninfected Wt mice treated with anti-IL-10R antibody alone. Western blot analysis demonstrated a slight reduction of AKT phosphorylation (S473) but a strong blockade (68%) of p70S6K phosphorylation (T389) in intestinal lysates from IL-10R-blocked, C. jejuni-infected Pi3kγ−/− mice compared to Wt mice (Figure 4D). In accordance with the histological score, the absence of PI3Kγ strongly reduced C. jejuni-induced I11β, Cxcl2 and Il17a mRNA accumulation (98.3%, 98.2% and 98.4% respectively) in IL-10R-blocked Pi3kγ−/− mice, compared to treated Wt mice (Figure 4E). To determine whether absence of PI3Kγ signaling is directly responsible for decreased C. jejuni-induced inflammatory gene expression, we isolated splenocytes from Wt and Pi3kγ−/− mice. Interestingly, C. jejuni-induced I11β, Cxcl2, Il17a and Tnfα mRNA expression was comparable between splenocytes obtained from Pi3kγ−/−and Wt mice (Supplemental Figure 2). These results suggest that PI3Kγ signaling does not directly regulate C. jejuni induced proinflammatory gene expression.

Figure 4. PI3Kγ deficiency attenuates C. jejuni-induced intestinal inflammation.

Eight cohorts of 4–6 Wt, Il10−/− and Pi3kγ−/−mice were treated with antibiotic for 7 days and then gavaged with a single dose of C. jejuni (109/mouse). Wt and Pi3kγ−/−mice were injected anti-IL-10R antibody (i.p. 0.5 mg/mouse/every 3 days) to block IL-10 receptors. Mice were sacrificed after 14 days. (A–B) H&E representation of intestinal inflammation. (C) Quantitative histological score of intestinal inflammation. (D) Western blot for phosphorylated AKT (S473), phosphorylated p70S6K (T389) and total AKT protein levels in pooled colonic lysates of infected mice. (E) Il1β, Cxcl2 and Il17a mRNA accumulation was quantified using real time PCR. Data represent means ± SEM.*, P < 0.05. Scale bar is 200 μm. Results are representative of 2 independent experiments.

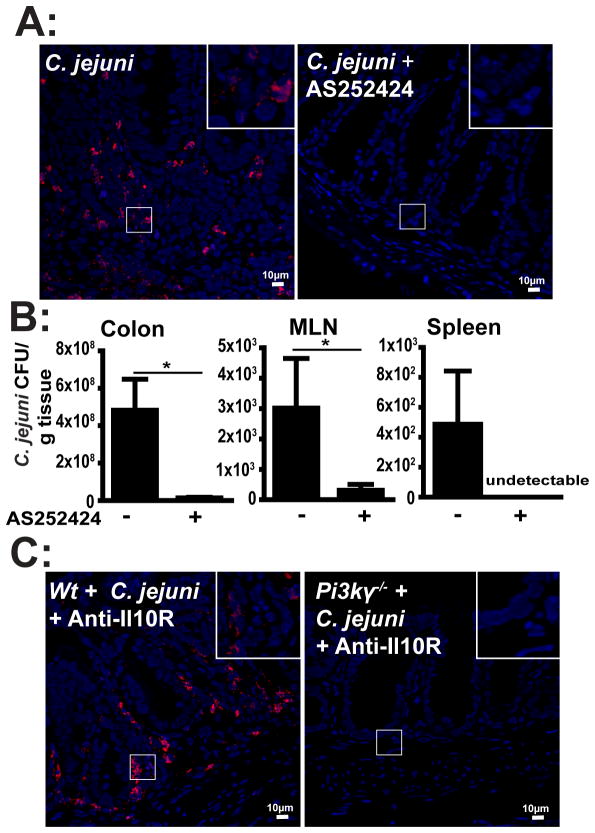

PI3Kγ mediates C. jejuni invasion

Since C. jejuni is an invasive intestinal pathogenic bacterium, we next investigated the impact of PI3Kγ signaling on C. jejuni invasion into intra- and extra-intestinal tissues. Following infection and treatment with the PI3Kγ inhibitor AS252424, C. jejuni DNA was visualized in the colon of Il10−/−; NF-κBEGFP mice using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and confocal microscopy imaging. Remarkably, while C. jejuni was abundant in inflamed crypts and lamina propria of vehicle-treated mice, the bacterium was barely detectable in AS252424-treated mice (Figure 5A). To assess the amount of viable C. jejuni in intestinal and extra-intestinal tissues, we aseptically collected samples from the colon, spleen and MLN and enumerated C. jejuni on Remel Campylobacter selective plates. Consistent with FISH results, AS252424 treatment decreased the amount of viable C. jejuni in colon and MLN by 97% and 90% compared to C. jejuni-infected, vehicle-treated mice (Figure 5B). Moreover, AS252424 treatment strongly reduced the levels of viable C. jejuni in the spleen, compared to vehicle-treated, infected mice. Again, to confirm our findings from pharmacologic studies, we infected Pi3kγ−/− mice treated with IL-10R blocking antibody and assessed C. jejuni invasion using FISH. C. jejuni was detected deeply inside the intestinal section of anti-IL-10R-treated Wt mice, whereas anti-IL-10R-treated Pi3kγ−/− mice exhibited a strong reduction in bacterial invasion into colonic tissues (Figure 5C). To determine whether PI3Kγ signaling derived from epithelial cells directly affects C. jejuni invasion, we infected a monolayer of murine colonic CMT-93 cells with C. jejuni in the presence or absence of AS252424 and measured bacterial translocation using a transwell culture system. As shown in supplemental Figure 3, PI3Kγ inhibition did not prevent C. jejuni translocation. Taken together, these results demonstrate that C. jejuni invasion into intestinal and extra-intestinal tissue is dependent upon functional PI3Kγ signaling, likely originating from immune cells.

Figure 5. PI3Kγ signaling promotes C. jejuni invasion into colon, MLN and spleen.

Cohorts of 4–6 germ-free Il10−/−; NF-κBEGFP mice, SPF Wt and Pi3kγ−/− mice were treated and infected as indicated in Figure 3 and 4. (A) C. jejuni (red dots) in colonic sections of infected mice was detected using FISH. Scale bar is 10 μm. (B) C. jejuni bacterial count in the colon, MLN and spleen of vehicle- or AS252424-treated mice. (C) Presence of C. jejuni (red dots) in colonic tissue of Wt and Pi3kγ−/− mice was determined using FISH. Data represent means ± SEM. * P < 0.05. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

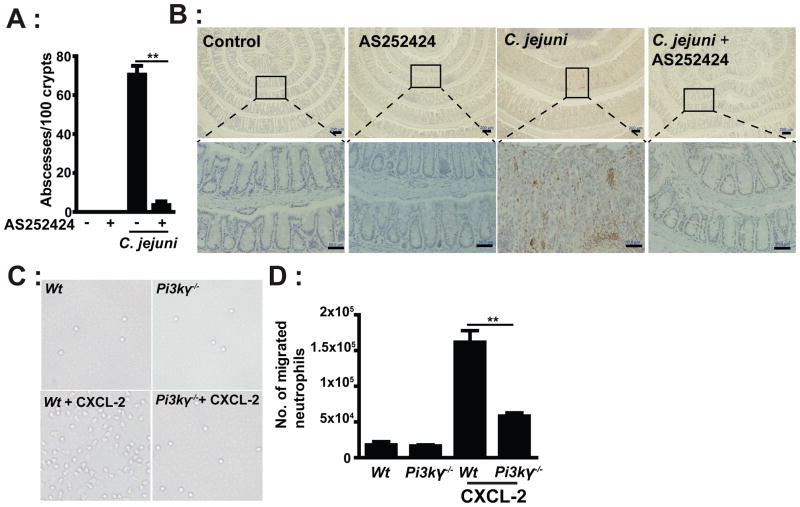

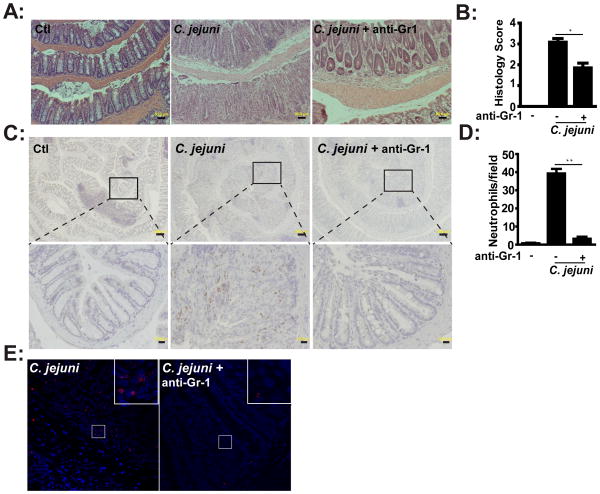

Neutrophil infiltration promotes C. jejuni-induced colitis

As previously reported, crypt abscesses and neutrophil infiltration is predominant in C. jejuni-infected Il10−/− mice (13). As seen in Figure 6A, C. jejuni infection of Il10−/− mice induced an average of greater than 71 colonic crypt abscesses per 100 crypts. Remarkably, C. jejuni-induced crypt abscesses were reduced by 95% in AS252424-treated Il10−/− mice compared to vehicle-treated mice. In accordance with this finding, MPO staining revealed that C. jejuni-induced neutrophil infiltration into colonic tissues was strongly reduced in the presence of AS252424 (Figure 6B). Since PI3Kγ is implicated in neutrophil migration (20), we next evaluated peripheral blood neutrophil motility in response to the chemokine CXCL-2 using a transwell migration assay. Migration was reduced by 64% in neutrophils isolated from Pi3kγ−/− mice compared to Wt cells (Figures 6C and D). Together our observations demonstrate that suppression of C. jejuni-induced colitis by pharmacologic inhibition of PI3Kγ is associated with an impaired neutrophil migration/infiltration and subsequent crypt abscess formation. To directly assess the role of neutrophils in C. jejuni-induced colitis, we depleted these cells using an anti-Gr-1 antibody (i.p. every 3 days for 6 days). Depletion of neutrophils attenuated C. jejuni-induced colitis in Il10−/− mice, as demonstrated by the significant reduction of histological scores (Figures 7A–B), which was correlated with reduced MPO staining (Figure 7C). Numbers of colonic neutrophils were reduced by more than 92% in anti-Gr-1 antibody-treated, C. jejuni infected mice compared to untreated mice (Figure 7D). To determine the effect of neutrophil depletion on C. jejuni invasion, we visualized C. jejuni presence in colon tissues using FISH assay. Interestingly, although neutrophils were depleted, C. jejuni invasion into the colon was strongly attenuated (Figure 7E), suggesting that other immune cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells are important in eliminating invading C. jejuni. Collectively, these results demonstrate that PI3Kγ signaling is essential for C. jejuni induced intestinal inflammation, likely by modulating neutrophil infiltration and migration into the intestinal tissues.

Figure 6. PI3Kγ mediates neutrophil accumulation and crypt abscesses in C. jejuni infected mice.

Cohorts of 4–6 germ-free Il10−/−; NF-κBEGFP mice were transferred to SPF conditions and infected/treated as indicated in Figure 3. (A) Number of crypt abscesses in C. jejuni infected mice. (B) IHC representation of MPO positive cells (brown dots) in the colon tissue of C. jejuni infected mice. (C) Peripheral blood neutrophils were isolated and plated in a transwell system and cells migration in response to CXCL-2 (250 ng/mL) at the bottom well were enumerated. Representative light images of neutrophils migrated into bottom wells. (D) Quantitative measurements of migrated neutrophils. Lower panels (scale bar 20 μm) are magnified images of area shown in the upper panels (scale bar 200 μm). Data represent means ± SEM. **, P < 0.01. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Figure 7. Neutrophils enhance C. jejuni-induced colitis.

Cohorts of 4–6 germ-free Il10−/−; NF-κBEGFP mice were transferred to SPF conditions and infected as in Figure 3. Neutrophils were depleted using anti-Gr1 antibody. (A) H&E representation of intestinal inflammation. (B) Quantitative histological score of intestinal inflammation. (C) IHC representation of MPO positive cells (brown dots) in the colon tissue of C. jejuni infected mice. (D) The colonic H&E stained sections were imaged (5 fields/mouse) and neutrophils were identified based on morphological features. Data are presented as average counts/mouse. (E) Presence of C. jejuni (red dots) in colonic tissue was determined using FISH. Lower panels (scale bar 20 μm) are magnified images of area shown in the upper panels (scale bar 200 μm). Data represent means ± SEM. *, P < 0.05. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

The molecular and cellular events leading to campylobacteriosis and its associated pathological features remain poorly understood. We previously reported that C. jejuni induced intestinal inflammation through mTOR signaling, a downstream target of the PI3K pathway, which was associated with neutrophil infiltration and tissue damage (13). However, the molecular events leading to C. jejuni induced neutrophil migration and their functional consequence on intestinal inflammation has not been addressed. In addition, because PI3Ks form a large family of kinases, the subunit responsible for neutrophil activation and migration following C. jejuni infection is unclear. In this study, we uncover the key role of innate immune cells, especially neutrophils in C. jejuni-induced intestinal inflammation. In addition, we identified PI3Kγ signaling as key event leading to campylobacteriosis.

Among the large family of PI3Ks, PI3Kγ is predominantly expressed in immune cells (19, 20). Disruption of PI3Kγ attenuates E. coli-induced lung injury resulting from neutrophil infiltration (28). Similarly, a reduction of neutrophil-mediated rheumatoid arthritis is observed in Pi3kγ−/− mice (29). Our study demonstrates that C. jejuni-induced colitis can be alleviated by inactivation of PI3Kγ signaling using either pharmacological or genetic manipulation.

Using FISH and culture assays, we observed that PI3Kγ signaling promotes C. jejuni invasion into colon, MLN and spleen of Il10−/− mice. Immunohistochemistry assays revealed massive infiltration of neutrophils into the colon following C. jejuni infection, an effect attenuated by inactivation of PI3Kγ. Moreover, depletion of neutrophils using anti-Gr1 antibody reduced C. jejuni induced intestinal inflammation by ~ 40%, an effect comparable to inactivation of PI3Kγ. Taken together, our findings highlight the essential role of PI3Kγ signaling and neutrophils in C. jejuni pathogenesis.

The contribution of innate and adaptive immune cells in host response to C. jejuni infection is not well understood. Adaptive immunity has been documented to protect the host against C. jejuni-induced diarrhea and intestinal inflammation in CD4 deficient HIV patients (30). On the other hand, the plasma of C. jejuni infected patients have been shown to contain anti-ganglioside 1 IgG (31) mimicry between the core lipooligosaccharides of C. jejuni and human gangliosides which may be associated with the development of Guillain-Barre Syndrome (3). Interestingly, adaptive immunity may not been essential for early intestinal inflammation as C. jejuni induced colitis is similar between Il10−/−; Rag2−/− mice and Il10−/− mice. This finding strongly suggests that innate immune cells are key cellular components responsible for the acute state (~12 days) of campylobacteriosis in our model. In addition, IHC analysis in conjunction with cell migration and depletion studies strongly point to the key role of neutrophils in campylobacteriosis. Therefore, although persistent C. jejuni infection triggers an adaptive immune response, the initial responses and associated tissue damage is mediated by neutrophils.

Following enteric bacterial infection, neutrophils are rapidly recruited into intestinal tissues where they eliminate microorganisms through phagocytosis and degranulation-mediated bacterial killing (32). However, overzealous neutrophil recruitment into a defined location like intestinal crypts often leads to significant host tissue damage. Neutrophil-induced tissue damage has been reported in non-infectious diseases such as IBD (33), lung injury (28) and arthritis (29). In C. jejuni-infected patients, histological assessment of intestinal tissues has revealed neutrophil infiltration and crypt abscesses (34). Using transmission electron microscopy analysis, we previously showed that crypt microvilli are virtually destroyed by accumulated neutrophils (13). Our current studies demonstrated that antibody-mediated depletion of neutrophils diminished intestinal inflammation and strongly decreased crypt abscess formation.

Although our data have identified neutrophils as key innate cells in C. jejuni mediated pathogenesis, the molecular events leading to their recruitment into intestinal crypts is less clear. We have shown a strong induction of the chemokine Cxcl2 in colonic lysates of C. jejuni infected Il10−/− mice. In vitro experiments indicate that intestinal epithelial cells (12) and splenocytes up-regulate Cxcl2 gene expression following C. jejuni infection. From these data, one could speculate that C. jejuni invasion leads to the secretion of various chemo-attractants including CXCL-2, from immune and non-immune cells, which then promote recruitment of neutrophils. Interestingly, C. jejuni-induced proinflammatory gene expression including Cxcl2 is comparable in splenocytes isolated from Pi3kγ−/− and Wt mice and blocking PI3Kγ doesn’t attenuate C. jejuni invasion through CMT-93 epithelial monolayer. We conclude that PI3Kγ signaling predominantly mediates its inhibitory effect through regulation of neutrophil migration. Interestingly, although neutrophils most likely participate in the removal of invading C. jejuni, FISH assay showed a strong decrease of the bacterium in colonic tissues of GR-1-treated mice. This finding suggests that other innate cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells are important for C. jejuni eradication in the colon. In this scenario, the beneficial impact of neutrophils in C. jejuni elimination is outweighed by the tissue destructive capacity of these innate cells and associated damage to the epithelial barrier. It is likely that C. jejuni located in the luminal compartment profits from this impaired barrier function to further invade the colonic tissues.

Presently, the primary treatment for campylobacteriosis resorts to antibiotics. However, antibiotic treatment is constrained by multiple factors, including minimal effectiveness in the late course of disease, a negligible reduction in disease duration (1.5 days), increased antibiotic resistance, and the risk of harmful eradication of normal flora (35). Thus alternatives to antibiotics are imperative for treating infectious enteric pathogens, and immunotherapy targeting specific signaling pathways such as PI3Kγ may provide such an alternative.

In summary, this report defines the critical role of PI3Kγ in mediating the pro-inflammatory effects of C. jejuni infection. We report that PI3Kγ mediated neutrophil infiltration plays an active role in the pathogenesis of C. jejuni infection. Accordingly, modulation of the cellular/molecular events leading to this process could represent a new therapeutic approach to control campylobacteriosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants DK047700, DK073338, AI082319 to C. Jobin and by P30 DK34987 for the CGIBD. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

The authors would like to thank Mrs. Brigitte Allard for technical assistance throughout this project. We would like to thank Dr. Janelle Arthur for editorial assistance. We would also like to thank Dr. Robert Bagnell, Mr. Steven Ray and Mrs. Victoria Madden (Microscopy Services Laboratory) and Mr. Robert Currin (Manager, Cell & Molecular Imaging Facility and UNC-Olympus Center), all of UNC-CH, for their assistance with the confocal fluorescent microscopy.

Abbreviations

- MLN

mesenteric lymph nodes

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- FISH

fluorescence in situ hybridization

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Author Contribution:

Conceived and designed the experiments: CJ, XS. Performed the experiments: XS. Analyzed the data: XS, CJ. Contributed reagents: RBS, BL. Wrote the paper: XS, CJ.

References

- 1.CDC. Incidence of laboratory-confirmed bacterial and parasitic infections, and postdiarrheal hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), by year and pathogen, Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet), United States, 1996 – 2011. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/foodnet/data/trends/tables/table2a-b.html#table-2b. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blaser MJ. Epidemiologic and clinical features of Campylobacter jejuni infections. J Infect Dis. 1997;176(Suppl 2):S103–105. doi: 10.1086/513780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nachamkin I. Chronic effects of Campylobacter infection. Microbes Infect. 2002;4:399–403. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(02)01553-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mortensen NP, Kuijf ML, Ang CW, Schiellerup P, Krogfelt KA, Jacobs BC, van Belkum A, Endtz HP, Bergman MP. Sialylation of Campylobacter jejuni lipo-oligosaccharides is associated with severe gastro-enteritis and reactive arthritis. Microbes Infect. 2009;11:988–994. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gradel KO, Nielsen HL, Schønheyder HC, Ejlertsen T, Kristensen B, Nielsen H. Increased Short- and Long-Term Risk of Inflammatory Bowel Disease After Salmonella or Campylobacter Gastroenteritis. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:495–501. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qin HY, Wu JC, Tong XD, Sung JJ, Xu HX, Bian ZX. Systematic review of animal models of post-infectious/post-inflammatory irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol. (2010/09/18) 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00535-00010-00321-00536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van den Bruele T, Mourad-Baars PE, Claas EC, van der Plas RN, Kuijper EJ, Bredius RG. Campylobacter jejuni bacteremia and Helicobacter pylori in a patient with X-linked agammaglobulinemia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;29:1315–1319. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-0999-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valenza G, Frosch M, Abele-Horn M. Antimicrobial susceptibility of clinical Campylobacter isolates collected at a German university hospital during the period 2006–2008. Scand J Infect Dis. 2010;42:57–60. doi: 10.3109/00365540903283723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young KT, Davis LM, Dirita VJ. Campylobacter jejuni: molecular biology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:665–679. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fouts DE, Mongodin EF, Mandrell RE, Miller WG, Rasko DA, Ravel J, Brinkac LM, DeBoy RT, Parker CT, Daugherty SC, Dodson RJ, Durkin AS, Madupu R, Sullivan SA, Shetty JU, Ayodeji MA, Shvartsbeyn A, Schatz MC, Badger JH, Fraser CM, Nelson KE. Major structural differences and novel potential virulence mechanisms from the genomes of multiple campylobacter species. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hofreuter D, Tsai J, Watson RO, Novik V, Altman B, Benitez M, Clark C, Perbost C, Jarvie T, Du L, Galan JE. Unique features of a highly pathogenic Campylobacter jejuni strain. Infect Immun. 2006;74:4694–4707. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00210-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lippert E, Karrasch T, Sun X, Allard B, Herfarth HH, Threadgill D, Jobin C. Gnotobiotic IL-10; NF-kappaB mice develop rapid and severe colitis following Campylobacter jejuni infection. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7413. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun X, Threadgill D, Jobin C. Campylobacter jejuni Induces Colitis Through Activation of Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Signaling. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:86–95. e85. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.09.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mansfield L, Patterson J, Fierro B, Murphy A, Rathinam V, Kopper J, Barbu N, Onifade T, Bell J. Genetic background of IL-10−/− mice alters host–pathogen interactions with Campylobacter jejuni and influences disease phenotype. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2008;45:241–257. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blaser MJ, Parsons RB, Wang WL. Acute colitis caused by Campylobacter fetus ss. jejuni. Gastroenterology. 1980;78:448–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rydstrom A, Wick MJ. Monocyte and neutrophil recruitment during oral Salmonella infection is driven by MyD88-derived chemokines. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:3019–3030. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koyasu S. The role of PI3K in immune cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:313–319. doi: 10.1038/ni0403-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gunzl P, Schabbauer G. Recent advances in the genetic analysis of PTEN and PI3K innate immune properties. Immunobiology. 2008;213:759–765. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2008.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Z, Jiang H, Xie W, Zhang Z, Smrcka AV, Wu D. Roles of PLC-beta2 and -beta3 and PI3Kgamma in chemoattractant-mediated signal transduction. Science. 2000;287:1046–1049. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sasaki T, Irie-Sasaki J, Jones RG, Oliveira-dos-Santos AJ, Stanford WL, Bolon B, Wakeham A, Itie A, Bouchard D, Kozieradzki I, Joza N, Mak TW, Ohashi PS, Suzuki A, Penninger JM. Function of PI3Kgamma in thymocyte development, T cell activation, and neutrophil migration. Science. 2000;287:1040–1046. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferguson GJ, Milne L, Kulkarni S, Sasaki T, Walker S, Andrews S, Crabbe T, Finan P, Jones G, Jackson S, Camps M, Rommel C, Wymann M, Hirsch E, Hawkins P, Stephens L. PI(3)Kgamma has an important context-dependent role in neutrophil chemokinesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:86–91. doi: 10.1038/ncb1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Korlath JA, Osterholm MT, Judy LA, Forfang JC, Robinson RA. A point-source outbreak of campylobacteriosis associated with consumption of raw milk. J Infect Dis. 1985;152:592–596. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.3.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ribechini E, Leenen PJM, Lutz MB. Gr-1 antibody induces STAT signaling, macrophage marker expression and abrogation of myeloid-derived suppressor cell activity in BM cells. European Journal of Immunology. 2009;39:3538–3551. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bai F, Town T, Qian F, Wang P, Kamanaka M, Connolly TM, Gate D, Montgomery RR, Flavell RA, Fikrig E. IL-10 signaling blockade controls murine West Nile virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000610. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muhlbauer M, Chilton PM, Mitchell TC, Jobin C. Impaired Bcl3 Up-regulation Leads to Enhanced Lipopolysaccharide-induced Interleukin (IL)-23P19 Gene Expression in IL-10−/− Mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283:14182–14189. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709029200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boxio R, Bossenmeyer-Pourie C, Steinckwich N, Dournon C, Nusse O. Mouse bone marrow contains large numbers of functionally competent neutrophils. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:604–611. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0703340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kankaanpää P, Pahajoki K, Marjomäki V, Heino J, White D. BioImageXD-New Open Source Free Software for the Processing, Analysis and Visualization of Multidimensional Microscopic Images. Microscopy Today. 2006;14:12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ong E, Gao XP, Predescu D, Broman M, Malik AB. Role of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-gamma in mediating lung neutrophil sequestration and vascular injury induced by E. coli sepsis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L1094–1103. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00179.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Camps M, Ruckle T, Ji H, Ardissone V, Rintelen F, Shaw J, Ferrandi C, Chabert C, Gillieron C, Francon B, Martin T, Gretener D, Perrin D, Leroy D, Vitte PA, Hirsch E, Wymann MP, Cirillo R, Schwarz MK, Rommel C. Blockade of PI3Kgamma suppresses joint inflammation and damage in mouse models of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Med. 2005;11:936–943. doi: 10.1038/nm1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snijders F, Kuijper EJ, de Wever B, van der Hoek L, Danner SA, Dankert J. Prevalence of Campylobacter-associated diarrhea among patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:1107–1113. doi: 10.1086/513643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oomes PG, Jacobs BC, Hazenberg MP, Banffer JR, van der Meche FG. Anti-GM1 IgG antibodies and Campylobacter bacteria in Guillain-Barre syndrome: evidence of molecular mimicry. Ann Neurol. 1995;38:170–175. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, Fauler B, Uhlemann Y, Weiss DS, Weinrauch Y, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004;303:1532–1535. doi: 10.1126/science.1092385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chin AC, Parkos CA. Neutrophil transepithelial migration and epithelial barrier function in IBD: potential targets for inhibiting neutrophil trafficking. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1072:276–287. doi: 10.1196/annals.1326.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Spreeuwel JP, Duursma GC, Meijer CJ, Bax R, Rosekrans PC, Lindeman J. Campylobacter colitis: histological immunohistochemical and ultrastructural findings. Gut. 1985;26:945–951. doi: 10.1136/gut.26.9.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ternhag A, Asikainen T, Giesecke J, Ekdahl K. A meta-analysis on the effects of antibiotic treatment on duration of symptoms caused by infection with Campylobacter species. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:696–700. doi: 10.1086/509924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.