Abstract

With the majority of HIV infections resulting from mucosal transmission, induction of an effective mucosal immune response is thought to be pivotal in preventing transmission. HIV-specific IgA, but not IgG, has been detected in genital tract, seminal fluid, urethral swabs, urine and vaginal wash samples of HIV-negative sex workers and HIV-status discordant couples. Purified mucosal and plasma IgA from some individuals with highly exposed, persistently sero-negative (HEPS) can neutralize infection and present cross-clade neutralization activity though present at low levels. We generated a CD4i human monoclonal antibody (mAb) F425A1g8 and characterized the impact of its isotype variants on HIV neutralizing activity. The result showed that, in contrast to little neutralization by the F425A1g8 IgG1 in the absence of sCD4, the IgA1 variant of the antibody (Ab) displayed significant independent neutralization activity against a range of HIV clade B isolates in the absence of sCD4. The studies of the neutralizing function of IgA isotypes, and the functional relationship between different antigenic epitopes and IgA antibodies, may also suggest strategies for the intervention of virus transmission and spread within the mucosa of host, as well as serve to inform the design of vaccine strategies that may be more effective at preventing mucosal transmission. This research clearly suggests that IgA isotype because of its unique molecular structure may play an important role in HIV neutralization.

Introduction

HIV infection occurs most often through the mucosal route via hetero- or homosexual contact. As expected, adaptive immune system responds to HIV infection with production of HIV-specific antibodies (1); however, numerous studies have clearly demonstrated the general inability of the humoral immune system to develop functionally effective neutralizing antibodies during natural infection or vaccination (2–4). The immune system is confounded by the immunogenicity of the variable loops, which are exposed on the surface of the virus, and tend to elicit strain specific antibodies (5) as well the transient exposure of specific neutralizing epitopes upon virion binding or engagement with CD4. Therefore, a huge gap in HIV vaccine development has been the inability to generate an immunogen that can elicit effective neutralizing antibodies (6).

Research has shown that not all people are equally susceptible to infection by HIV-1. Some individuals may remain HIV-1 sero-negative despite repeated viral exposure (7). In a study of these highly exposed, persistently HIV-1 sero-negative (HEPS) (8) subjects, HIV-specific IgA responses were detected in the genital tract of female sex workers from Thailand and Kenya (9, 10). HIV-specific IgA, but not IgG, was also present in seminal fluid, urethral swabs, urine and vaginal wash samples from HIV-1 HEPS heterosexual couples (11, 12). Purified mucosal and plasma IgA from HEPS individuals can neutralize HIV-1 infection (8, 13, 14). Although present at low levels, these IgA demonstrated cross-clade neutralizing activity and were able to inhibit HIV mucosal transcytosis (15, 16). However, with a number of conflicting reports in the literature (17–21), it remains unresolved as to which isotype may protect the mucosa from HIV infection (22). More recently, analysis of the immune correlates to the RV144 vaccine study suggests that Env specific IgA antibodies may mitigate the effects of potentially protective antibodies (23). Given that anti-HIV IgA antibodies are rare in infected individuals, it has been difficult to characterize how Ab isotype structure and antigenic specificity participate in viral neutralization, which is clearly of significant in the design of novel immunogens to elicit neutralizing antibodies.

In this paper we will report on the novel discovery that the IgA Isotype switch variant of the CD4i Ab, F425A1g8, displays significant neutralizing activity, whereas there is little neutralization by the parental hybrid or any of the IgG subclasses in the absence of sCD4.

Materials and Methods

Monoclonal antibodies, Virus and Cell Lines

The neutralizing Ab F425A1g8 was generated in our laboratory, as previously described (24), and was shown to bind to the CD4i site of gp120 (data not shown). The immunoglobulin expression vectors pLC-HuCκ, pHC-HuCγ1 and pHC-HuCα1 were obtained from Dr. Gary McLean. They contained the human immunoglobulin light chain and heavy chain γ1, as well as α1 constant regions respectively. The CHO-K1 cells were from American Type Culture Collection. The following reagents were obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: SF162 (R5) from Dr. Jay Levy; 89.6 (R5X4) from Dr. Ronald Collman; BaL (R5) from Dr. Suzanne Gartner, Dr. Mikulas Popovic and Dr. Robert Gallo; 93MW960 (clade C, R5) from Dr. Robert Bollinger and the UNAIDS Network for HIV; JR-FL (R5) from Dr. Irvin Chen; Isolate 67970 (CXCR4) was from Dr. David Montefiori. TZM-bl cells from Dr. John C. Kappes, Dr. Xiaoyun Wu and Transzyme, Inc.

Construction, production and purification of F425A1g8 variants

F425A1g8 VH and VL were PCR amplified respectively from F425A1g8 hybridoma cell line using the specific primers (Table I), which introduced restriction enzymes sites (5’ Nhe I and 3’ Hind III for VH; 5’ Nhe I and 3’ Not I for VL). The VH fragment was cloned into the expression vectors pHC-HuCγ1 and pHC-huCα1 individually. The VL was cloned into vector pLC-huCk. Paired purified plasmids encoding the F425A1g8 light chain versus IgG1 heavy chain, and F425A1g8 light chain versus IgA1 heavy chain were co-transfected into CHO-K1 cells in equimolar amounts in 6-well-plates using lipofectamine LTX reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies). Selection with G418 (800µg/ml) and puromycin (10µg/ml) were added after 24 hours. Cells were plated in 96 well plates with selection and wells were screened when dense using IgG and IgA capture ELISA. Positive wells were cloned by limiting dilution until a stable, producing cell line was isolated. Ab was purified from culture supernatant using protein G (IgG1) or SSL7 (IgA1) chromatography according to manufacturer’s instructions (GE Healthcare and Invivogen, respectively).

Table I.

Primers for amplifying variable domain of F425A1g8

| F425-A1g8VH-5’ (Nhe I) | CTAGCTAGCCGCCACCATGGAGCTTGG |

| F425-A1g8VH-3’ (Hind III) | CCCTTGAAGCTTGCTGAAGAGACGGTG |

| F425-A1g8VL-5’ (Nhe I) | CTAGCTAGCCGCCACCATGGACATGAGG |

| F425-A1g8VL-3’ (Not I) | GACAGATGGTGCGGCCGCAGTTCGTTTGATATCC |

(Restriction sites were in bold; VH: variable domain of heavy chain; VL: variable domain of light chain)

SDS-PAGE

Purified F425A1g8 antibody variants were mixed with 2× sample loading buffer (0.12M Tris; 5% SDS; pH6.8) with or without DTT (40mM) and 1/10 volume of tracking dye to final concentration of 100µg/ml, boiled 3–5 minutes prior to resolving on a 4–20% gradient gel (Pierce Precise Gel) with 20ul of samples loaded per lane. The gel was stained using GelCode Blue (Pierce) and bands compared to the molecular weight standard (Cell Signaling Technology).

Immunoreactivity of recombinant F425A1g8 variants

Live cell ELISA assay was performed to determine the immunoreactivity of F425A1g8 variances to the CD4 binding site. SF2 infected cells (1×106) were incubated with Ab at 20, 10, 5, 2.5µg/ml for 30 minutes followed by washing and incubation with HRP-conjugated goat anti-human IgG or IgA (Southern Biotechnology Associates). The human monoclonal b12 IgG1 or IgA1, which were generated as described (25), were run at 20µg/ml as a standard to determine relative reactivity of the F425A1g8 variants with HIV. After washing, cells were re-suspended in 100µl TMB substrate and incubated for 10 minutes. Reaction was stopped by adding 100µl of 1M phosphoric acid and samples read on plate reader at 450nm.

Detection of binding affinity of recombinant F425A1g8 variants using BIAcore

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) was used to compare the binding affinity of the F425A1g8 variants to gp120/CD4 complexes using a BIAcore 3000 instrument. FLSC gp120-CD4 complex was kindly provided by Dr. George Lewis (Institute of Human Virology, Baltimore, Maryland). Antibodies were immobilized onto the surface of sensor chip CM-5 (GE Lifesciences, BR100012) using amine coupling. The process involves activation of carboxymethyl groups on a dextran-coated chip by reaction with N-hydroxysuccinimide, followed by covalent bonding of the ligand to the chip surface via amide linkages and blockage of excess activated carboxyls with ethanolamine. Reference surfaces were prepared in the same manner, except that all carboxyls were blocked without added ligand. Purified FLSC gp120-CD4 complex was allowed to flow over the immobilized, ligand surface and the binding response of analyte to ligand was recorded. The maximum RU with each analyte indicates the level of interaction, and reflects comparative binding affinity.

Direct viral neutralization

The neutralization activity of F425A1g8 variants were determined in vitro using a TZM-bl assay with a panel of three isolates including an SF162, JR-FL, and 67970. Primary isolate virus was grown in PHA-stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) as previously described (26–28) and titered on TZM-bl cells (29) to determine TCID50. Serial two-fold dilutions of F425A1g8 variants were incubated with virus stock diluted to 100TCID50 for 1 hour, 37°C prior to the addition of TZM-bl cells (1×104 cell/well). Using β-galactosidase reagent from Promega, as an indicator of HIV replication, plates were incubated for 48 hours, 37°C, 5% CO2 prior to the measurement of β-galactosidase activity. Percent neutralization was determined based on control wells of virus and media and IC50 and IC90 values calculated by regression analysis.

Antibody dependent cell-mediated viral inhibition (ADCVI)

ADCVI activity was measured using HIV grown in PHA stimulated PBMC as previously described (30). Neutrophils were obtained from peripheral blood of seronegative donors by Ficoll-Hypaque gradient centrifugation. Antibodies were titered in 96 well, round bottom plates in 50µl of media containing 20% heat-inactivated FBS. Target cells were PBMC productively infected with HIV-1 four days prior to use as previously described (31), and 1×105 infected cells were added per well in 50µl. Within 10 minutes of the combination of Ab and infected cells, neutrophils were added to the wells at 1×106 effector cells/well in 100µl resulting in an E:T ratio of 10:1. After 4 hours, in order to measure the surviving infectious virus, PHA stimulated PBMC were added as indicator cells (1×105/well). These indicator PBMC were incubated for seven days in the presence of IL-2 at which time the supernatant was quantitated for p24 by a p24-specific ELISA (32). IC50 values were determined by linear regression analysis and significance was ascertained by Student’s t-test. Control wells included irrelevant Ab, no effectors, or no targets to determine background release of virus, maximal production of virus, and whether PMN alone were infected, respectively. Viral inhibition was calculated based on the p24 amount from an irrelevant Ab control. Experiments were repeated three to five times.

Results

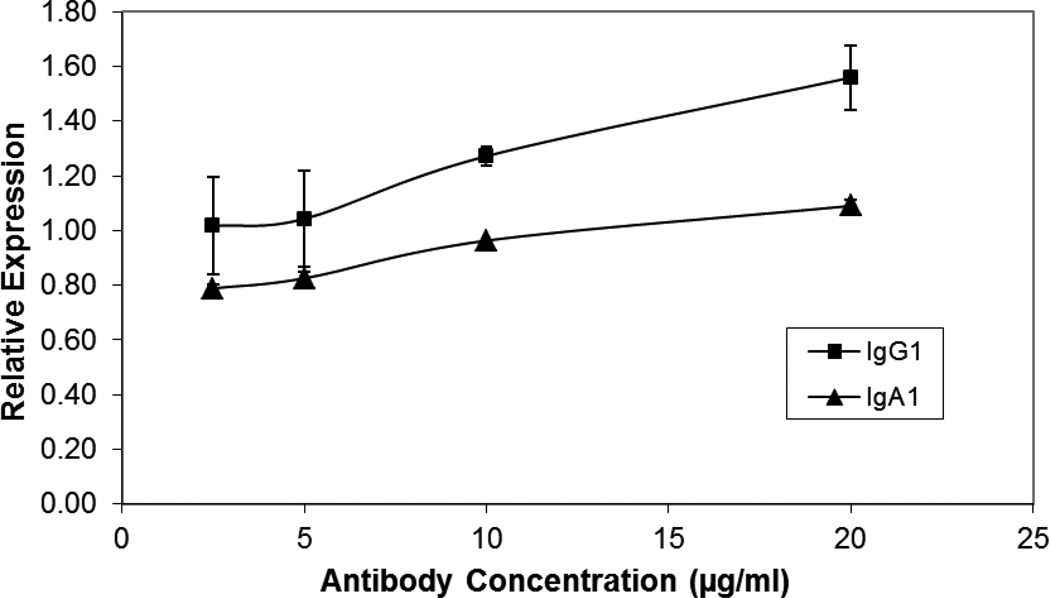

The immunoreactivity of F425A1g8 IgG1 and IgA1 variants

Prior to using the antibody variants in any assays, the antibodies were subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis and were determined to be monomeric with no aggregation (supplement Figure 1). To determine the immunoreactivity of F425A1g8 variants with the CD4i epitope on HIV infected cells, a live cell ELISA assay was used. Since HRP conjugated secondary antibodies directly binding to the light chain may be competed by antigen, IgG or IgA isotype specific secondary antibodies had to be used. Therefore, b12 IgG1 and IgA1 were used to establish relative reactivity by comparing the absorbance (optical density) obtained with F425A1g8 variants with that obtained from the b12 controls. The results are expressed as a relative “b12 unit” (OD F425A1g8/OD b12). As shown in Figure 1, the reactivity of F425A1g8 IgG1 and IgA1 with HIV was retained. Interestingly, the IgG1 variant of F425A1g8 had more relative binding than that observed for the IgA1 variant.

Figure 1. F425A1g8 IgG1 and IgA1 Variants immunoreactivity with HIV-infected cells.

Immunoreactivity of F425A1g8 IgG1 and IgA1 variants with HIV-1. SF2-infected cells (1×106) were incubated with titered antibodies of F425A1g8 IgG1 (▲) and IgA1 (♦) which were detected using HRP-conjugated goat anti-human IgG or IgA. Bound antibody was visualized using TMB substrate and stopped by 100µl of 1M phosphoric acid. The OD was read on plate reader at 450nm. b12 IgG1 or IgA1 (20µg/ml) was a standard to determine relative reactivity of the F425A1g8 variants with HIV.

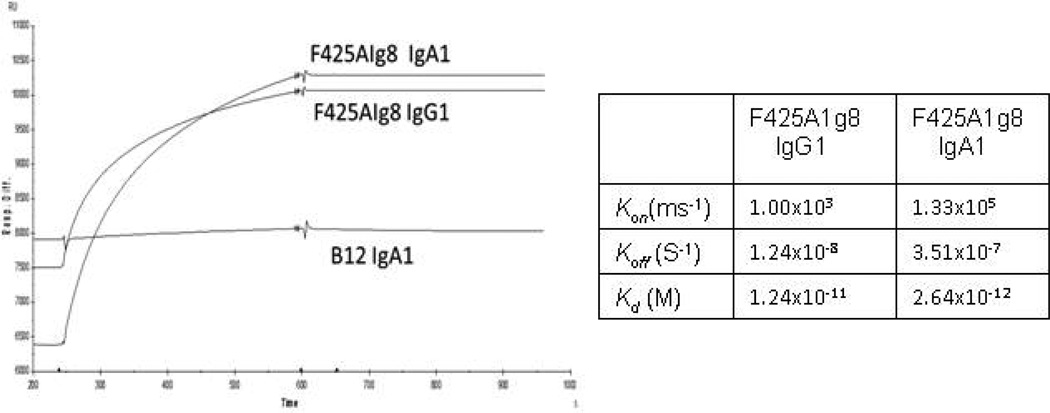

The binding affinity of F425A1g8 IgG1 and IgA1 variants

To further determine binding affinity of the antibodies, we obtained a single chain polypeptide encoding HIV-1 BaL and the D1D2 domain of CD4 linked by a 20 amino-acid linker (termed FLSC for full-length single chain) and which presents as a natural gp120-CD4 configuration (33). We detected the binding affinity of F425A1g8 IgG1 and IgA1 variants with FLSC gp120-CD4 complex using BIAcore. Given the structure of the FLSC, the CD4 binding site is unavailable for b12 binding; therefore, b12 was used as a negative antibody control in these studies and and gp120 monomer was used as a negative control for the antigen. It was determined that the binding affinities of F425A1g8 IgG1 and IgA1 with FLSC gp120-CD4 complex were very similar (Figure 2). The KD of F425A1g8 IgG1 was 1.24×10−11 M and of F425A1g8 IgA1 was 2.64×10−12 M. Both F425A1g8 variants failed to bind to gp120 monomer (data not shown). Thus, it is clearly shown that the recombinant F425A1g8 IgG1 and IgA1 retain similar immunoreactivity with the CD4i epitope activity.

Figure 2. Binding kinetics of recombinant F425A1g8 variants to gp120/CD4 complex using BIAcore.

Binding affinity of the F425A1g8 variants to gp120/CD4 complexes as determined by BIAcore. Antibodies (10µg/ml, 20µl) were immobilized onto the surface of sensor chip CM-5 (GE Lifesciences, BR100012) using amine coupling. Purified FLSC gp120-CD4 complex (30µg/ml, 100µl) was allowed to flow over the immobilized-ligand surface and the binding response of analyte to ligand was recorded.

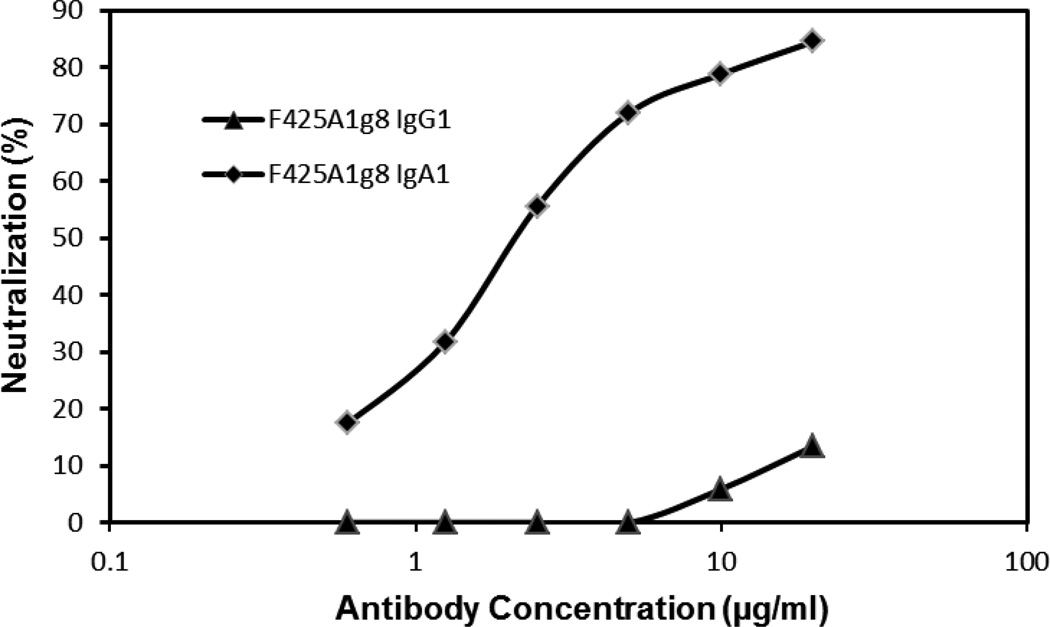

The neutralizing activity against HIV-1 by IgG1 and IgA1 variants of F425A1g8

Neutralization of HIV was tested using TZM-bl cells and three clade B primary isolate viruses (SF162, JR-Fl, 67970) grown in PBMCs. Serial dilutions of Ab were tested and IC50 values for JR-F1, 67970 and IC90 for SF162 were determined by linear regression. In contrast to minimal neutralization by F425A1g8 IgG1 in the absence of sCD4, the IgA1 variant of the Ab displayed significant neutralization activity against a number of HIV clade B isolates in the absence of sCD4 as shown in Table II and Figure 3. Even though the F425A1g8 IgG1 neutralized the SF162 isolate, the IgA1 variant of F425A1g8 displayed significantly increased neutralization. This differential neutralization was confirmed in studies using tier 1 and reference panel virus (n=7 including BaL and SF162) grown in 293T cells (personal communication, Dr. Michael Seaman, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center). Increased neutralization mediated by IgA1 occurs despite relatively decreased immunoreactivity of the IgA1 to SF2 infected cells as compared to the IgG1.

Table II.

Neutralization of HIV-1 by F425A1g8 IgG1 and IgA1 Isotypesa

| JR-FL Clade B,R5 (IC50)b |

67970 Clade B, X4 (IC50) |

SF162 Clade B,R5 (IC90)c |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| IgG1d | >40 | >40 | 2.3±1.4 |

| IgA1e | 1.73±0.2 | 23.3±14.3 | 1.7±1.0 |

The result were the mean of triplicate wells and were representative of at least three independent experiments.

IC50: or IC90: concentration (µg/ml) of antibody required for 50% or 90% inhibition of HIV, respectively.

F425A1g8 IgG1 variant expressed from CHO-K1 cells.

F425A1g8 IgA1 variant expressed from CHO-K1 cells.

Figure 3. Neutralization of JR-FL by F425A1g8 IgG1 and IgA1 variants measured using TZM-bl cells.

JR-FL (100TCID50) was incubated with two-fold serial dilutions of F425A1g8 IgG1 (▲) and IgA1 (♦) variants for one hour prior to the addition of TZM-bl cells. HIV was measured as b-galactosidase activity after 48 hours. Percent neutralization was determined by the formula ((control – test)/control) ×100.

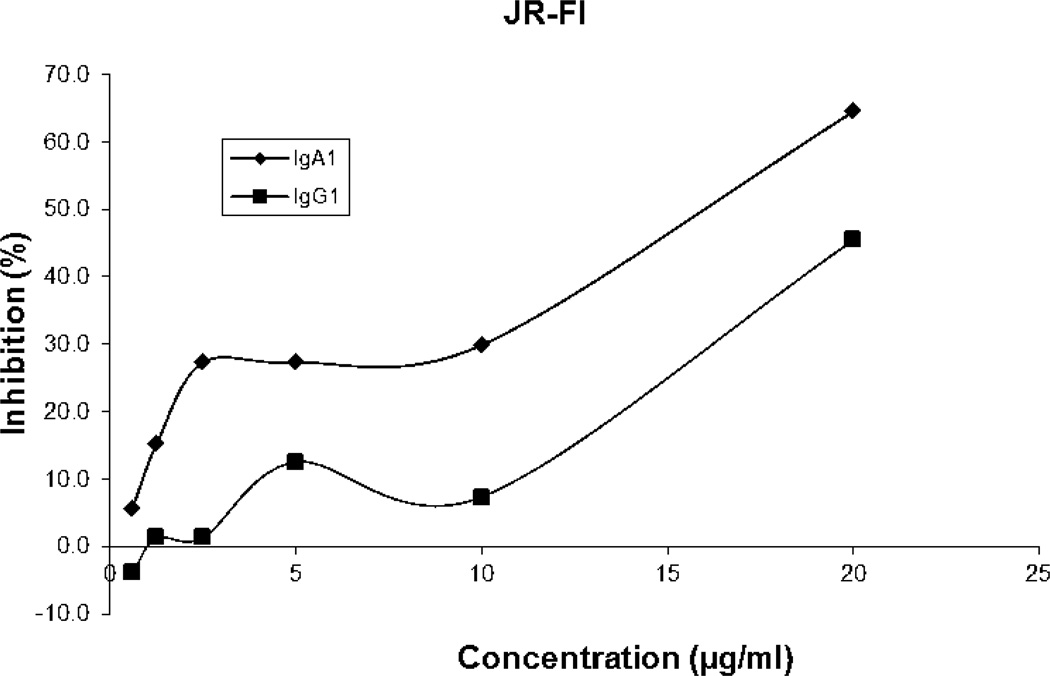

Functional activity of F425A1g8 switched variants in mediating ADCVI

We also investigated the impact of the switch constant domain between IgG1 and IgA1 of F425A1g8 on functional ability of ADCVI for HIV and HIV-infected cells. HIV-1-binding antibodies mediate ADCVI through an interaction with specific Fc receptors on effector cells, resulting in effector cell mediated destruction of infected cells with Ab-bound antigen (34). Therefore, ADCVI would be a useful assay to determine the ability of the isotype variants of specific antibodies to mediate effector cell destruction of or inhibit HIV replication in an infected target cell population in vivo. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN) or neutrophils are the predominant (60–70%) type of white blood cell in the circulation and play a critical role in innate immunity against infections. PMN consistently express multiple receptors for IgG including FcγRIIa (CD32), FcγRIIIa (CD16) and FcγRIIIb. They also express FcγRI (CD64) following induction with G-CSF. In addition to Fc receptors for IgG, PMN also express Fc receptors for IgA (FcαR, CD89). Cross-linking Fcγ receptors as well as cross-linking of the IgA receptor on PMN by monoclonal antibodies have been shown to be critical to induce ADCC against tumor cells (35, 36). Therefore, although traditional ADCVI (or ADCC) assays are based on mononuclear cell populations, we propose to use neutrophils as effectors.

Since the binding of F425A1g8 was different with strains of virions, a total of five isolates, including clade B representing R5, R5X4, and X4 isolates and clade C isolate (R5), were tested in this variant of the neutralization assay. Ab-mediated destruction of HIV and HIV-infected cells is determined by testing the inhibition of subsequent HIV replication or p24 levels. The results of these assays are summarized in Table III as well as in Figure 4, as represented by JR-FI strain. The F425A1g8 IgA1 showed significant ADCVI activity for both clade B isolates, and a single clade C isolate. For two of four clade B isolates (SF162 and JR-Fl, both R5), F425A1g8 IgG1 failed to mediate ADCVI activity whereas significant activity was observed for F425A1g8 A1 (Table III) with p values ranging from 0.0008-0.05 for multiple experiments. Two clade B strains, BaL (R5) and 89.6 (R5X4) failed to be inhibited by either isotype variant at the concentrations tested. Of importance, both isotype variants inhibited the clade C isolate, 93MW960. Interestingly, the IgG1 isotype had greater activity against the Clade C isolate than IgA1 (p value from 0.0012 to 0.0598). This variant in impact of isotype in ADCVI may result from affinity and/or binding specificity of the Fc fragment of IgG1 and IgA1 subclasses with Fc receptors on the surface of neutrophils. On the other hand, the antigen density and epitope orientation may result in differences in outcome. Since only one clade C strain was tested for ADCVI in this project, it would be valuable to explore the impact of IgA1 isotype on clade C. There was no viral inhibition in mock control wells, which contained Ab, target cells, or indicator cells without neutrophils. Viral replication was similar for control wells containing effector cells, target cells without Ab, and target cells alone (data not shown).

Table III.

ADCVI activity of HIV-1 by F425A1g8 IgG1 and IgA1 variants

| IC50(µg/ml)a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BaL Clade B, R5 (nb=6) |

JR-FL Clade B, R5 (n=6) |

93MW960 Clade C R5 (n=5) |

89.6 Clade B,R5X4 (n=3) |

SF162 Clade B,R5 (n=3) |

|

| IgG1 | >40 | >40 | 9.5±7.9 | >40 | >40 |

| IgA1 | >40 | 16.6±5.1 | 18.3±13.4 | >40 | 6.1±5.9 |

The ADCVI activity was determined by IC50 that represents concentration (µg/ml) of antibody required for 50% inhibition of HIV.

n: repeat times of ADCVI assay

Figure 4. Inhibition of JR-FL by F425A1g8 IgG1 and IgA1 variants measured using ADCVI.

Antibody-dependent cell-mediated viral inhibition (ADCVI) mediated by F425A1g8 IgG1 (▲) and IgA1 (♦) antibodies and neutrophils. F425A1g8 variants were incubated with JR-FL infected PBMC just prior to adding neutrophils at an E:T ratio of 10:1. After 4 hours, PHA stimulated PBMC were added as indicator cells and p24 quantitated by ELISA after one week. Percent inhibition was determined by the formula: [(p24 control-p24 test)/p24 control] ×100.

Discussion

We generated and characterized the isotype switch variants of the CD4i Ab, F425A1g8. The study on the property of recombinant IgG1 and IgA1 variants has shown that they were monomeric antibody molecules and remained similar high binding affinity with the CD4i epitope. The IgA1 variant of F425A1g8 displayed significant neutralization activity alone. In contrast, there was little neutralization by the parental hybrid or IgG1 subclass variant in the absence of sCD4. Combined with epidemiological data, these data suggest that HIV-specific IgA1 antibodies may play an important independent role in providing protective immunity against HIV infection in mucosal surfaces. However, the relationship of IgA structure to functional neutralization of HIV, as well as why the functional IgA antibodies could not be induced in the most natural HIV infected population, remain to be fully resolved. Exploration of these questions may yield information that may guide vaccine design.

The entry of HIV-1 into target cells typically requires the sequential binding of the viral exterior envelope glycoprotein, gp120, to CD4 and a chemokine receptor. CD4-induced (CD4i) antibodies recognize the epitope of gp120 structures that are formed or exposed by CD4 binding, and can block virus binding to the chemokine receptor. However, CD4i neutralizing antibodies demonstrate large conformational requirements for binding in that the site is only exposed upon CD4/gp120 binding, which limits Ab access to the proximal chemokine site (37). The results of many studies have demonstrated that Fab or scFv of CD4i antibodies tend to be more effective at neutralization than the intact molecule, presumably due to greater access to the epitope (37, 38). The distinct structural properties of IgA provide this Ab isotype some unique functional capabilities. IgA1 molecules have a lengthy hinge region with a 13 amino–acid insertion. Crystal studies have shown that the structure of IgA1 resembles more of a “T” structure as compared to the “Y” structure of an IgG1 molecule (39). This flexible stretch property of IgA1 would seem likely to afford a greater reach between its two antigen-binding sites and potential to decrease steric hindrance (8), allowing improved access to the relatively hidden CD4i epitopes recognized by F425A1g8 compared to IgG1 isotypes. This may be particularly important in an effective neutralizing Ab response to HIV when increasing Ab flexibility could result in cooperative interactions on gp120/gp41 trimers. Increased flexibility of Ab molecules have been shown by our laboratory to increase Ab neutralization activity (26). It can be suggested that the IgA1 variant displayed higher ADCVI than IgG1 because there are more IgA receptors than IgG receptors on neutrophils. However, when comparing IgG1 and IgA1 variants of other human monoclonal anti-HIV antibodies, we generally do not observe a difference in ADCVI activity (data not shown). Regardless, IgG and IgA receptor density is the focus of additional studies.

A number of studies have reported that the IgA Ab may have more advantages than IgG antibodies for inhibiting tumor growth and infectious diseases via mediation of immune cell targeting (40). For example, IgA antibodies are far more effective than IgG anti-tumor antibodies in recruiting neutrophils for destruction of lymphoma and solid tumor targets (41–43). Specific secretory IgA Ab against Streptococcus mutans was effective in preventing re-colonization with Streptococci, whereas the parental IgG1 Ab was rapidly cleared (44). It has been hypothesized that the long hinge of IgA1 and the FcαRI may provide for particularly efficient bridging between antigen on a target cell and FcαRI on an effector cell (45). The increase in ADCVI activity observed with the IgA1 construct of F425A1g8 in our study supports this hypothesis. It may also be possible that failure of IgA to stimulate FcγRIIb, resulted in an “inhibitory” response contributing to more protective activity of IgA as compared to IgG (46). While IgA antibodies represent a new attractive candidate for immunotherapy of cancer and infectious diseases (47–54) it has been difficult to determine the importance of IgA to HIV neutralization in different immune compartments given the failure of HIV infected individuals to produce significant mucosal IgA. However, engineered HIV specific IgA antibodies are ideal to study the structural effects of IgA on neutralization activity and compartment specific function as neutralizing and arming antibodies. The data we published in here support the notion that the IgA1 variant of F425A1g8 CD4i Ab has substantial independent neutralization activity against HIV-1 compared to neutralization by the CD4i IgG. These results suggest that IgA isotype utilizing its unique molecular structure can play an important role in HIV neutralization and warrants further study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the generous contributions to this work of Ig expression vector provided by Dr. Gary McLean (University of Texas Health Sciences Center, Houston, TX). We are also grateful to AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH, as well as Dr. Jay Levy, Dr. Neal Halsey; Dr. Ronald Collman, Dr. Suzanne Gartner, Dr. Mikulas Popovic, Dr. Robert Gallo; Dr. Robert Bollinger, Dr. Irvin Chen for supporting HIV strain and Dr. John C. Kappes, Dr. Xiaoyun Wu, Dr. David Montefiori for providing TZM-bl cells. The authors also thank Dr. Paula M. Kuzontkoski for her efforts on editing and revising the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- Ab

antibody

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- mAb

monoclonal Ab

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH grants R01AI06396 and R21AI075932

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflict interest.

References

- 1.Willey S, Aasa-Chapman MM. Humoral immunity to HIV-1: neutralisation and antibody effector functions. Trends Microbiol. 2008;16:596–604. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou JY, Montefiori DC. Antibody-mediated neutralization of primary isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells is not affected by the initial activation state of the cells. J Virol. 1997;71:2512–2517. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2512-2517.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey J, Lassen K, Yang H-C, Quinn T, Ray S, Bankson J, Siliciano R. Neutralizing antibodies do not mediate suppression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in elite suppressors or selection of plasma virus variants in patients on highly active anti-retroviral therapy. J Virol. 2006;80:4758–4770. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.10.4758-4770.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palker TJ, Clark ME, Langlois AJ, Matthews TJ, Weinhold KJ, Randall RR, Bolognesi DP, Haynes BF. Type-specific neutralization of the human immunodeficiency virus with antibodies to envencoded synthetic peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:1932–1936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.6.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Posner M, Elboim H, Santos D. The construction and use of a human-mouse myeloma analogue suitable for the routine production of hybridomas secreting human monoclonal antibodies. Hybridoma. 1987;6:611–625. doi: 10.1089/hyb.1987.6.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walker BD, Burton DR. Toward an AIDS vaccine. Science. 2008;320:760–764. doi: 10.1126/science.1152622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fowke KR, Nagelkerke NJ, Kimani J, Simonsen JN, Anzala AO, Bwayo JJ, MacDonald KS, Ngugi EN, Plummer FA. Resistance to HIV-1 infection among persistently seronegative prostitutes in Nairobi, Kenya. Lancet. 1996;348:1347–1351. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)12269-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Broliden K, Hinkula J, Devito C, Kiama P, Kimani J, Trabbatoni D, Bwayo JJ, Clerici M, Plummer F, Kaul R. Functional HIV-1 specific IgA antibodies in HIV-1 exposed, persistently IgG seronegative female sex workers. Immunol Lett. 2001;79:29–36. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(01)00263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaul R, Trabattoni D, Bwayo JJ, Arienti D, Zagliani A, Mwangi FM, Kariuki C, Ngugi EN, MacDonald KS, Ball TB, Clerici M, Plummer FA. HIV-1-specific mucosal IgA in a cohort of HIV-1-resistant Kenyan sex workers. AIDS. 1999;13:23–29. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199901140-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beyrer C, Artenstein AW, Rugpao S, Stephens H, VanCott TC, Robb ML, Rinkaew M, Birx DL, Khamboonruang C, Zimmerman PA, Nelson KE, Natpratan C. Epidemiologic and biologic characterization of a cohort of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 highly exposed, persistently seronegative female sex workers in northern Thailand. Chiang Mai HEPS Working Group. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:59–67. doi: 10.1086/314556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazzoli S, Trabattoni D, Lo Caputo S, Piconi S, Ble C, Meacci F, Ruzzante S, Salvi A, Semplici F, Longhi R, Fusi ML, Tofani N, Biasin M, Villa ML, Mazzotta F, Clerici M. HIV-specific mucosal and cellular immunity in HIV-seronegative partners of HIV-seropositive individuals. Nat Med. 1997;3:1250–1257. doi: 10.1038/nm1197-1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lo Caputo S, Trabattoni D, Vichi F, Piconi S, Lopalco L, Villa ML, Mazzotta F, Clerici M. Mucosal and systemic HIV-1-specific immunity in HIV-1-exposed but uninfected heterosexual men. AIDS. 2003;17:531–539. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200303070-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devito C, Hinkula J, Kaul R, Lopalco L, Bwayo JJ, Plummer F, Clerici M, Broliden K. Mucosal and plasma IgA from HIV-exposed seronegative individuals neutralize a primary HIV-1 isolate. AIDS. 2000;14:1917–1920. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200009080-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devito C, Hinkula J, Kaul R, Kimani J, Kiama P, Lopalco L, Barass C, Piconi S, Trabattoni D, Bwayo JJ, Plummer F, Clerici M, Broliden K. Cross-clade HIV-1-specific neutralizing IgA in mucosal and systemic compartments of HIV-1-exposed, persistently seronegative subjects. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30:413–420. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200208010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belec L, Ghys PD, Hocini H, Nkengasong JN, Tranchot-Diallo J, Diallo MO, Ettiegne-Traore V, Maurice C, Becquart P, Matta M, Si- Mohamed A, Chomont N, Coulibaly IM, Wiktor SZ, Kazatchkine MD. Cervicovaginal secretory antibodies to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) that block viral transcytosis through tight epithelial barriers in highly exposed HIV-1-seronegative African women. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:1412–1422. doi: 10.1086/324375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devito C, Broliden K, Kaul R, Svensson L, Johansen K, Kiama P, Kimani J, Lopalco L, Piconi S, Bwayo JJ, Plummer F, Clerici M, Hinkula J. Mucosal and plasma IgA from HIV-1-exposed uninfected individuals inhibit HIV-1 transcytosis across human epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2000;165:5170–5176. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fiore JR, Laddago V, Lepera A, La Grasta L, Di Stefano M, Saracino A, Lopalco P, Pastore G, Angarano G. Limited secretory-IgA response in cervicovaginal secretions from HIV-1 infected, but not high risk seronegative women: lack of correlation to genital viral shedding. New Microbiol. 2000;23:85–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mestecky J, Jackson S, Moldoveanu Z, Nesbit LR, Kulhavy R, Prince SJ, Sabbaj S, Mulligan MJ, Goepfert PA. Paucity of antigen-specific IgA responses in sera and external secretions of HIV-type 1-infected individuals. AIDS Res Hum Retrovis. 2004;20:972–988. doi: 10.1089/aid.2004.20.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raux M, Finkielsztejn L, Salmon-Ceron D, Bouchez H, Excler JL, Dulioust E, Grouin JM, Sicard D, Blondeau C. Comparison of the distribution of IgG and IgA antibodies in serum and various mucosal fluids of HIV type 1-infected subjects. AIDS Res Hum Retrovis. 1999;15:1365–1376. doi: 10.1089/088922299310070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mestecky J, Wright PF, Lopalco L, Staats HF, Kozlowski PA, Moldoveanu Z, Alexander RC, Kulhavy R, Pastori C, Maboko L, Riedner G, Zhu Y, Wrinn T, Hoelscher M. Scarcity or absence of humoral immune responses in the plasma and cervicovaginal lavage fluids of heavily HIV-1-exposed but persistently seronegative women. AIDS Res Hum Retrovis. 2011;27:469–486. doi: 10.1089/aid.2010.0169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dorrell L, Hessell AJ, Wang M, Whittle H, Sabally S, Rowland- Jones S, Burton DR, Parren PW. Absence of specific mucosal antibody responses in HIV-exposed uninfected sex workers from the Gambia. AIDS. 2000;14:1117–1122. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006160-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alexander R, Mestecky J. Neutralizing antibodies in mucosal secretions: IgG or IgA? Curr HIV Res. 2007;5:588–593. doi: 10.2174/157016207782418452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haynes BF, Gilbert PB, McElrath MJ, Zolla-Pazner S, Tomaras GD, Alam SM, Evans DT, Montefiori DC, Karnasuta C, Sutthent R, Liao HX, DeVico AL, Lewis GK, Williams C, Pinter A, Fong Y, Janes H, DeCamp A, Huang Y, Rao M, Billings E, Karasavvas N, Robb ML, Ngauy V, de Souza MS, Paris R, Ferrari G, Bailer RT, Soderberg KA, Andrews C, Berman PW, Frahm N, De Rosa SC, Alpert MD, Yates NL, Shen X, Koup RA, Pitisuttithum P, Kaewkungwal J, Nitayaphan S, Rerks-Ngarm S, Michael NL, Kim JH. Immune-correlates analysis of an HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trial. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1275–1286. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cavacini L, Duval M, Song L, Sangster R, Xiang SH, Sodroski J, Posner M. Conformational changes in env oligomer induced by an antibody dependent on the V3 loop base. AIDS. 2003;17:685–689. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200303280-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu X, Pollock D, Duval M, Lewis C, Joseph K, Meade H, Cavacini L. Neutralization of HIV by Milk Expressed Antibody. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318271c450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cavacini L, Kuhrt D, Duval M, Mayer K, Posner M. Binding and neutralization activity of IgG1 and IgG3 from serum of HIV infected individuals. AIDS Res Hum Retrovis. 2003;19:785–792. doi: 10.1089/088922203769232584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cavacini L, Duval M, Song L, Sangster R, Xiang S-H, Sodroski J, Posner M. Conformational changes in env oligomer induced by an antibody dependent on the V3 loop base. AIDS. 2003;17:685–689. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200303280-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wei X, Decker J, Liu H, Zhang Z, Arani R, Kilby J, Saag M, Wu X, Shaw G, Kappes J. Emergence of resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in patients receiving fusion inhibitor (T-20) monotherapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:1896–1905. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.6.1896-1905.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duval M, Posner MR, Cavacini LA. A bispecific antibody composed of a nonneutralizing antibody to the gp41 immunodominant region and an anti-CD89 antibody directs broad human immunodeficiency virus destruction by neutrophils. J Virol. 2008;82:4671–4674. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02499-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miranda L, Duval M, Doherty H, Seaman M, Posner M, Cavacini L. The neutralization properties of a HIV-specific antibody are markedly altered by glycosylation events outside the antigen-binding domain. J Immunol. 2007;178:7132–7138. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.7132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cavacini L, Peterson J, Nappi E, Duval M, Goldstein R, Mayer K, Posner M. Minimal incidence of serum antibodies reactive with intact primary isolate virions in HIV-1 infected individuals. J Virol. 1999;73:9638–9641. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.11.9638-9641.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stubbe H, Berdoz J, Kraehenbuhl J-P, Corthesy B. Polymeric IgA is superior to monomeric IgA and IgG carrying the same variable domain in preventing Clostridium difficile toxin A damaging of T84 monolayers. J Immunol. 2000;164:1952–1960. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fouts TR, Tuskan R, Godfrey K, Reitz M, Hone D, Lewis GK, DeVico AL. Expression and characterization of a single-chain polypeptide analogue of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120- CD4 receptor complex. J Virol. 2000;74:11427–11436. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.24.11427-11436.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forthal DN, Gilbert PB, Landucci G, Phan T. Recombinant gp120 vaccine-induced antibodies inhibit clinical strains of HIV-1 in the presence of Fc receptor-bearing effector cells and correlate inversely with HIV infection rate. J Immunol. 2007;178:6596–6603. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hernandez-Ilizaliturri F, Jupudy V, Ostberg J, Oflazoglu E, Huberman A, Repasky E, Czuczman M. Neutrophils contribute to the biological antitumor activity of rituximab in a non-hodgkin's lymphoma severe combined immunodeficiency mouse model. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:5866–5873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rafiq K, Bergtold A, Clynes R. Immune complex-mediated antigen presentation induces tumor immunity. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:71–79. doi: 10.1172/JCI15640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chioe H, Li W, Wright PL, Vasilieva N, Venturi M, Huang C-C, Grundner C, Dorfman T, Zwick MB, Wang L, Rosengerg ES, Kwong PD, Burton DR, Robinson JE, Sodroski JG, Farzan M. Tyrosine sulfation of human antibodies contributes to recognition of the CCR5 binding region of HIV-1 gp120. Cell. 2003;114:161–170. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00508-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moulard M, Phogat SK, Shu Y, Labrijn AF, Xiao X, Binley JM, Zhang MY, Sidorov IA, Broder CC, Robinson J, Parren PW, Burton DR, Dimitrov DS. Broadly cross-reactive HIV-1- neutralizing human monoclonal Fab selected for binding to gp120-CD4- CCR5 complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6913–6918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102562599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boehm MK, Woof JM, Kerr MA, Perkins SJ. The Fab and Fc fragments of IgA1 exhibit a different arrangement from that in IgG: a study by X-ray and neutron solution scattering and homology modelling. J Mol Biol. 1999;286:1421–1447. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bakema JE, van Egmond M. Immunoglobulin A: A next generation of therapeutic antibodies? MAbs. 2011;3:352–361. doi: 10.4161/mabs.3.4.16092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Otten MA, Rudolph E, Dechant M, Tuk CW, Reijmers RM, Beelen RH, van de Winkel JG, van Egmond M. Immature neutrophils mediate tumor cell killing via IgA but not IgG Fc receptors. J Immunol. 2005;174:5472–5480. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huls G, Heijnen IA, Cuomo E, van der Linden J, Boel E, van de Winkel JG, Logtenberg T. Antitumor immune effector mechanisms recruited by phage display-derived fully human IgG1 and IgA1 monoclonal antibodies. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5778–5784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dechant M, Valerius T. IgA antibodies for cancer therapy. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2001;39:69–77. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00105-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ma JK, Hikmat BY, Wycoff K, Vine ND, Chargelegue D, Yu L, Hein MB, Lehner T. Characterization of a recombinant plant monoclonal secretory antibody and preventive immunotherapy in humans. Nat Med. 1998;4:601–606. doi: 10.1038/nm0598-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Woof JM, Burton DR. Human antibody-Fc receptor interactions illuminated by crystal structures. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:89–99. doi: 10.1038/nri1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ravetch JV, Bolland S. IgG Fc receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:275–290. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wolfe DN, Kirimanjeswara GS, Goebel EM, Harvill ET. Comparative role of immunoglobulin A in protective immunity against the Bordetellae. Infect Immun. 2007;75:4416–4422. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00412-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lohse S, Derer S, Beyer T, Klausz K, Peipp M, Leusen JH, van de Winkel JG, Dechant M, Valerius T. Recombinant dimeric IgA antibodies against the epidermal growth factor receptor mediate effective tumor cell killing. J Immunol. 2011;186:3770–3778. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bakema JE, Ganzevles SH, Fluitsma DM, Schilham MW, Beelen RH, Valerius T, Lohse S, Glennie MJ, Medema JP, van Egmond M. Targeting FcalphaRI on polymorphonuclear cells induces tumor cell killing through autophagy. J Immunol. 2011;187:726–732. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van der Pol W, Vidarsson G, Vile HA, van de Winkel JG, Rodriguez ME. Pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide-specific IgA triggers efficient neutrophil effector functions via FcalphaRI (CD89) J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1139–1145. doi: 10.1086/315825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Iagudaeva E, Zhigis LS, Razguliaeva OA, Zueva VS, Mel'nikov EE, Zubov VP, Kozlov LV, Bichucher AM, Kotel'nikova OV, Alliluev AP, Avakov AE, Rumsh LD. [Isolation and determination of activity of IgA1 protease from Neisseria meningitidis] Bioorg Khim. 2010;36:89–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vidarsson G, van Der Pol WL, van Den Elsen JM, Vile H, Jansen M, Duijs J, Morton HC, Boel E, Daha MR, Corthesy B, van De Winkel JG. Activity of human IgG and IgA subclasses in immune defense against Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B. J Immunol. 2001;166:6250–6256. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.10.6250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hellwig SM, van Spriel AB, Schellekens JF, Mooi FR, van de Winkel JG. Immunoglobulin A-mediated protection against Bordetella pertussis infection. Infect Immun. 2001;69:4846–4850. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.8.4846-4850.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Balu S, Reljic R, Lewis MJ, Pleass RJ, McIntosh R, van Kooten C, van Egmond M, Challacombe S, Woof JM, Ivanyi J. A novel human IgA monoclonal antibody protects against tuberculosis. J Immunol. 2011;186:3113–3119. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.