Abstract

Objective

This study assesses in a baboon model the hemodynamics and HLA immunogenicity of chronically implanted bioengineered (decellularized with collagen conditioning treatments) human and baboon heart valve scaffolds.

Methods

Fourteen baboons underwent pulmonary valve replacement, eight with decellularized and conditioned (bioengineered) pulmonary valves derived from either allogeneic (N=3) or xenogeneic (human) (N=5) hearts; for comparison, six baboons received clinically relevant reference cryopreserved or porcine valved conduits. Panel reactive serum antibodies (HLA Class I&II), complement fixing antibodies (C1q binding), and C-reactive protein titers were measured serially until elective sacrifice at 10 or 26 weeks. Serial transesophageal echocardiograms (TEE) measured valve function and geometry. Differences were analyzed with Kruskal-Wallis and Wilcoxon Rank Sum. P≤ 0.05 significant.

Results

All animals survived and thrived, exhibiting excellent immediate implanted valve function by TEE. Over time, reference valves developed smaller indexed effective orifice areas, EOAI=0.84(1.22) cm2/m2 median (range) while all bioengineered valves remained normal, EOAI=2.45 (1.35) cm2/m2; P=0.005. None of the bioengineered valves developed elevated peak transvalvular gradients, 5.5(6.0) versus 12.5(23.0) mmHg, P=0.003. Cryopreserved valves provoked the most intense antibody responses. Two of five human bioengineered and two of three baboon bioengineered valves did not provoke any Class I antibodies. Bioengineered human (but not baboon) scaffolds provoked Class II antibodies. C1q+ antibodies developed in four recipients.

Conclusions

Valve dysfunction correlated with markers for more intense inflammatory provocation. The tested bioengineering methods reduced antigenicity of both human and baboon valves. Bioengineered replacement valves from both species were hemodynamically equivalent to native valves.

Keywords: valves, surgery, xeno-transplantation, bioengineering, cardiac valve prostheses, tissue engineering, homografts, allografts, pulmonary valve

INTRODUCTION

There is increasing interest in subhuman primates for biomedical research.1 However, they are rarely used for evaluating bioengineered cardiovascular constructs. The Genus Papio (baboons) is potentially valuable for comparative tissue engineering research given significant similarities with humans in cardiac anatomy, physiology, valve dimensions, resident antigens, innate and acquired immune systems. Yet there are few reported baboon chronic survival cardiac surgical replacement valve performance studies.2, 3 A baboon orthotopic valve replacement model could be a significant preclinical tool for bridging cardiovascular tissue engineering to “real world” clinical applications. Papio hamadryas Anubis, an Old World monkey species, is genetically more similar to homo sapiens as compared to other non-hominoid primates and far more so than hoofed food stock ungulate mammals.(eFigure1) The latter are often used both as valve test models (e.g. sheep) and as source material (e.g. porcine) for bioprosthetic valves. International standards and regulatory guidelines for implantable cardiovascular devices typically require large animal preclinical in vivo validation studies.4 For evaluating bioprosthetic heart valves, the classical juvenile sheep model is typically chosen as it is very robust and sensitive for predicting valve structural failure due to dystrophic calcification.5 However, all ungulates express powerful non-HLA xeno-epitopes such as alpha-galactosyl to which all catarrhines (humans, apes and Old World Monkeys) possess natural antibodies. Conversely ungulates cannot be used to directly test human derived uncrosslinked tissue due to profound xenotransplant rejection.6 After removal of cells, it is not known whether heart valve ECM scaffolds remain functionally antigenic and proinflammatory across catarrhine species. Thus for both mechanistic research and possible regulatory utility, these studies were undertaken to evaluate the suitability of the baboon as a subhuman primate model for testing clinical prototype bioengineered heart valves.

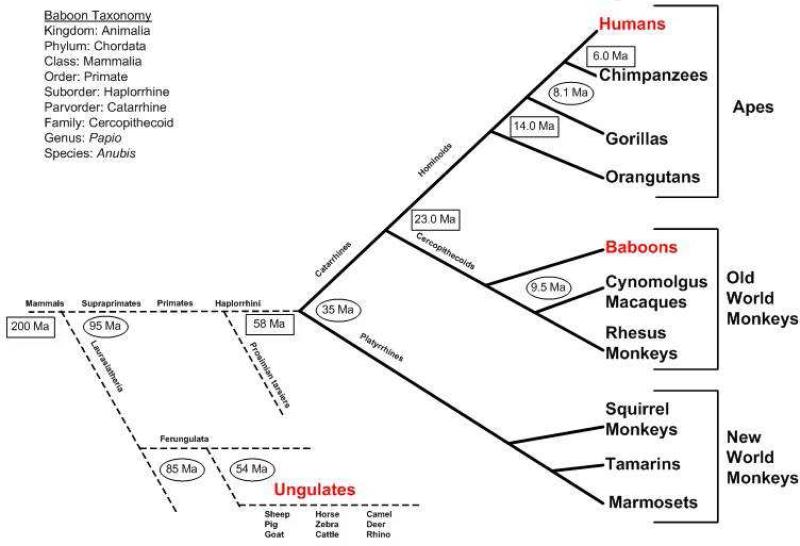

eFigure 1. Relative Primate Homology.

Time domain is estimated with fossil  or mtDNA evidence

or mtDNA evidence  ; Ma = million years ago. Primates first appeared as fossils dated to c. 95 Ma. The depicted divergences represent generalized combinations of physical anthropological findings and computational algorithms based on genetic sequencing data. Of the Old World monkeys, the baboon has the most genomic homology to humans. Data from multiple sources including: Raaum RL, Sterner KN, Noviello CM, Stewart C-B, Disotell TR: Catarrhine primate divergence dates estimated from complete mitochondrial genomes: Concordance with fossil and nuclear DNA evidence. Journal of Human Evolution. 2005;48:237-257.

; Ma = million years ago. Primates first appeared as fossils dated to c. 95 Ma. The depicted divergences represent generalized combinations of physical anthropological findings and computational algorithms based on genetic sequencing data. Of the Old World monkeys, the baboon has the most genomic homology to humans. Data from multiple sources including: Raaum RL, Sterner KN, Noviello CM, Stewart C-B, Disotell TR: Catarrhine primate divergence dates estimated from complete mitochondrial genomes: Concordance with fossil and nuclear DNA evidence. Journal of Human Evolution. 2005;48:237-257.

The current clinical standard for pediatric valved conduit reconstructions is the cryopreserved, cadaver derived allograft “biologic” pulmonary valve, historically termed valve “homografts”. As traditionally prepared, donor cells are retained through surgical implantation, yet these valves do not grow, and the donor cell population disappears; durability is limited especially in infants and children, typically failing due to dystrophic calcification driven by chronic inflammation.7 Cryopreserved human homografts have been conclusively shown to contain HLA antigens capable of provoking antibodies in recipients.8 To reduce inflammatory responses, various tissue decellularization treatments of allogeneic tissues have been devised and some show promise.9-11 Unlike allografts, the clinical results with decellularized porcine valve xenografts have been very poor with accelerated inflammatory destruction.12, 13 This research utilizes valve scaffolds bioengineered (decellularized and conditioned) to be design optimal, minimally pro-inflammatory and attractive biologically to cells both in vitro and in vivo.14, 15 As tested here, these are not “tissue engineered valves” (TEHVs). TEHVs are a subset of bioengineered in which the scaffolds are “seeded” with cells in a bioreactor before implantation.

The bioengineered valve scaffolds tested in these studies are acellular but otherwise inherently similar to native valves in design, hemodynamic performance, matrix chemistry and material properties.10, 16, 17 As such, they could function as the platform or scaffold for a tissue engineered valve, and since a scaffold without cells at the time of surgical implantation is the “worst case” scenario for a tissue engineered construct in which seeded cells have failed to repopulate, it is the appropriate starting point for the development of new evaluative tools for preclinical assessment of tissue engineered heart valves.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Donors, Recipients, Surgery

Fourteen healthy post pubescent male baboons weighing 28-34 kg were selected as recipients. Donors were unrelated animals 2-4 kg larger than the recipients. Anesthesia and cardiopulmonary bypass methods were refined as previously reported by us.18 All recipients had excision of native valves and main pulmonary artery segments, then test valve conduits were inserted with standard homograft surgical techniques using end-to-end anastomoses. Five were replaced with human bioengineered pulmonary valves for 10 weeks (N=3) or 26 weeks (N=2); three received bioengineered baboon pulmonary valves for a duration of 10 weeks. Three types of clinically analogous alternatives (N=6) were used as reference valves, cryopreserved pulmonary valves from humans (N=2), baboons (N=2) and stentless porcine (N=2) bioprostheses (size 21 Medtronic Freestyle®, Medtronic Corporation, Minneapolis, MN). Studies were performed with IACUC approval (SNPRC), in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, (National Research Council, 2011).

Preparation of Bioengineered Valves

Baboon pulmonary valves were harvested and cryopreserved with clinical methods.7 Seven cryopreserved human valves at end of storage time limits, were obtained from a clinical tissue bank (LifeNet Health, Virginia Beach, VA). Human and baboon bioengineered valves were prepared by subsequent decellularization using a previously reported laboratory developed, double-solvent, multi-detergent, enzyme-assisted, reciprocating osmotic cell fracture method optimized for pulmonary valves.10 Prior to implantation, all decellularized valves were conditioned in solutions designed to acidify tissue pH, rehydrate the collagen helix moisture envelope, align and compact collagen fibrils, and restore soluble proteins to the matrix.16 These decellularized-conditioned valves are termed “bioengineered”.

Transesophageal and Dobutamine Stress Echocardiography

Valve performance was evaluated by transesophageal (TEE) and dobutamine stress echocardiography with geometric dimensions and functional parameters measured and calculated as recommended for evaluation of prosthetic heart valves by the American Society of Echocardiography.19 A 5.0/ 3.7 MHz omni-plane TEE probe (Philips Medical Systems; Andover, MA) was positioned after induction of general anesthesia. Images were captured in real time on an HP SONOS 2500 platform (Philips Medical Systems) and recorded for quantitative off-line analyses. Baseline measurements were performed before cardiopulmonary bypass and after sternotomy closure during stable hemodynamics. Dobutamine was administered intravenously as a continuous infusion (Sigma Spectrum Volumetric Infusion pump, Sigma International Inc.; Medina, NY), with measurements repeated at dosages of 2 and 4 mcg/kg/min. Terminal measurements were similarly performed. Leaflet thicknesses were measured in triplicate by 2D and M-mode echocardiography.

Serial Panel Reactive Antibodies, Complement Fixation, C-reactive Protein Titers

Immediate pre and post operative as well as serial weekly post-operative serum samples were assayed qualitatively for the development of panel reactive antibodies using LABScreen® mixed Class I&II HLA bead assay (One Lambda, Inc., Canoga Park, CA, USA) run on Luminex 200 System (Luminex, Inc., Austin, TX) after serum purification (HiTrap, Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, England). All sera were also assayed with a second assay, LABScreen® PRA (One Lambda, Inc), to confirm positivity and calculate the clinically familiar percentage PRA developing to Class I&II antigens. This %PRA assay contains bead sites to 55 Class I and 32 Class II phenotypes and allows for some discrimination of responsible antigen specificities. Serum C–Reactive Protein titers were measured by ELISA at day 0 and days 7, 35, 70 postoperatively (Monkey CRP, Life Diagnostics, West Chester, PA). Class I complement fixing IgG antibodies were measured with a solid state assay (C1q Screen, One Lambda, Inc).

Explant Pathology Methods

At necropsy, the heart lung block was removed and severity of pericardial adhesions scored (absent, mild, moderate, severe). Test valves were excised with cuffs of native tissue beyond both anastomoses for explant pathology evaluations. Explanted valves were fixed with HistoChoice® MB (Amresco, Solon, OH) and photographed without magnification (Sony® Cybershot, San Diego, CA) and at macroscopic 6.3x (SteREO Discovery V12, Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) to document visual observations and imaged with radiographic methods for calcium mineral formation (Faxitron-LR, Lincolnshire, IL). Longitudinal sections were cut through each cusp, from the free edge to the base, including the corresponding sinus and arterial wall. Paraffin-embedded sections were used for routine hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stains (American Histo Laboratory, Gaithersburg, MD). For immunohistochemistry (IHC), following antigen retrieval (10 minutes, 90°C; Antigen Unmasking Solu tion, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) deparaffinized sections of each valve were incubated overnight with a 1:25 dilution of CD79 (B-cell; mouse monoclonal; Dako) followed by application of a secondary antibody (alkaline phosphatase-conjugated; Vectastain ABC-AP Kits, Vector Laboratories). Slides were examined via light and fluorescence microscopy with digital camera and imaging software (Axio Imager.Z1; Axio Vision; Carl Zeiss). Multiple low magnification (2.5x) H&E images from each entire valved conduit were blindly reviewed (SLH) and the inflammatory response scored based on maximum percentage of tissue area per low power field infiltrated with inflammatory cells: minimal (0-10%), mild (10-25%), moderate (25-50%) or marked (50-100%).

Statistical Methods

Kolmogrov–Smirnoff test for normality indicated these data sets were not normally distributed so nonparametric tests were employed and values reported as median(range). Differences between groups were analyzed for continuous variables with Kruskal-Wallis and ordinal variables by Wilcoxon Rank Sum Tests. P≤0.05 was considered significant (SAS 9.2 and SPSS v.17); Bonferroni correction was applied for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Clinical Outcomes

All baboons were successfully weaned from CPB, survived and thrived. One recipient easily tolerated emergency open surgical removal of an intercurrent gastric bezoar (hair).

2D and Doppler Echocardiographic Assessment of Valve Performance

Compared to bioengineered, reference valves developed higher peak (20.0(29.0) versus 5.5(6.0) mmHg, P=0.0003) and mean (12.5(23.0) versus 3.5(4.0) mmHg, P=0.003) pressure gradients by 10 weeks post-implant (Table 1). None of the bioengineered valves developed elevated resting valve gradients (Figure 1, data and notes). The majority (5 of 6) reference valves developed cusp thickening (≥ 1.5 mm) and restriction in cusp excursion (Table 2). In contrast, mild cusp thickening was seen in only one bioengineered valve (animal #10), and all had normal cusp mobility. Bioengineered valves maintained stable normal effective orifice areas (EOA) to 10 and 26 weeks. Reference valves developed markedly decreased EOA as compared to the bioengineered valve group (0.72(1.08) cm2 versus 1.77(1.19) cm2; P=0.005). Bioengineered cusp dysfunctional regurgitation was typically trace to mild, but was moderate for one C1q+ recipient receiving a human derived bioengineered valve (animal #10).

Table 1.

Echocardiography measurements of Test and Reference valves

| Valve Implant Type | Exam | N | Valve Diameter (2D Echo) | Maximum Geometric Valve Areaa | Peak Gradient (Doppler) | Mean Gradient (Doppler) | EOAc (Doppler) | EOAIc (Doppler) | Cardiac Output | BSAd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bioengineered Valves | cm | cm2 | mmHg | mmHg | cm2 | cm2/m2 | mL/min | m2 | ||

| Papio Bioengineered | Day 0 | 3 | 1.58 (0.29) | 1.96 (0.75) | 4.0 (6.0) | 3.0 (4.0) | 1.96 (0.93) | 2.40 (0.93) | 3251 (2994) | 0.79 (0.16) |

| 10 wk | 3 | 1.76 (0.19) | 2.43 (0.50) | 5.0 (3.0) | 2.0 (2.0) | 2.28 (0.92) | 3.09 (1.03) | 4143 (11) | 0.76 (0.11) | |

| Human Bioengineered | Day 0 | 5 | 2.11 (0.64) | 3.50 (2.11) | 3.0 (1.0) | 2.0 (0.0) | 2.05 (0.36) | 2.65 (0.39) | 3398 (1878) | 0.78 (0.09) |

| 10 wk | 5 | 2.00 (0.51) | 3.14 (1.49) | 8.0 (6.0) | 3.0 (4.0) | 1.73 (1.14) | 2.32 (1.28) | 4705 (3797) | 0.78 (0.15) | |

| 26 wk | 2 | 1.97 (0.13) | 3.04 (0.40) | 4.0 (4.0) | 2.0 (2.0) | 2.5 (0.06) | 3.15 (0.07) | 3708 (1344) | 0.80 (0.04) | |

| Reference Valves | ||||||||||

| Papio Cryopreserved | Day 0 | 2 | 1.68 (0.15) | 2.21 (0.39) | 6.0 (0.0) | 3.5 (1.0) | 2.12 (0.43) | 2.64 (0.06) | 5040 (2955) | 0.80 (0.15) |

| 10 wk | 2 | 1.52 (0.08) | 1.82 (0.19) | 23.0 (18.0) | 14.5 (11.0) | 0.68 (0.41) | 0.84 (0.35) | 2755 (2) | 0.79 (0.16) | |

| Human Cryopreserved | Day 0 | 2 | 2.01 (0.18) | 3.18 (0.57) | 4.5 (1.0) | 2.0 (0.0) | 2.33 (0.47) | 2.75 (0.17) | 3980 (2379) | 0.84 (0.14) |

| 10 wk | 2 | 1.75 (0.30) | 2.42 (0.82) | 12.0 (8.0) | 7.5 (5.0) | 1.35 (0.41) | 1.57 (0.43) | 3940 (2179) | 0.85 (0.03) | |

| Porcine Glutaraldehyde | Day 0 | 2 | 1.65 (0.40) | 2.17 (1.04) | 5.0 (4.0) | 3.0 (2.0) | 2.19 (1.15) | 2.59 (1.34) | 4270 (383) | 0.84 (0.01) |

| 10 wk | 2 | 1.97 (0.06) | 3.05 (0.19) | 35.5 (23.0) | 21.5 (13.0) | 0.52 (0.06) | 0.61 (0.08) | 2776 (825) | 0.85 (0.01) | |

| All Bioengineeredb | 10 wk | 8 | 1.76 (0.54) | 2.43 (1.56) | 5.5 (6.0)* | 3.5 (4.0)** | 1.77 (1.19)† | 2.45 (1.35)‡ | 4148 (3797) | 0.78 (0.16) |

| All Reference Valvesb | 10 wk | 6 | 1.75 (0.52) | 2.42 (1.42) | 30.0 (39.0)* | 12.5 (23.0)** | 0.72 (1.08)† | 0.84 (1.22)‡ | 2813 (2666) | 0.85 (0.16) |

Data reported as median(range). Porcine glutaraldehyde, papio cryopreserved and human cryopreserved valves are reference valves while papio 10 week, human 10 week and human 6 month implant valves are bioengineered valves.

Maximum geometric test valve areas (theoretical) are calculated by measuring the internal annulus diameters at time of implantation and explantation with Hegar dilators.

All Bioengineered versus all Reference valves at 10 weeks

P=0.0003

P= 0.003

P=0.005

P=0.002.

EOA = Effective Orifice Area; EOAI = EOA Indexed to BSA.

BSA calculated by Haycock Formula.

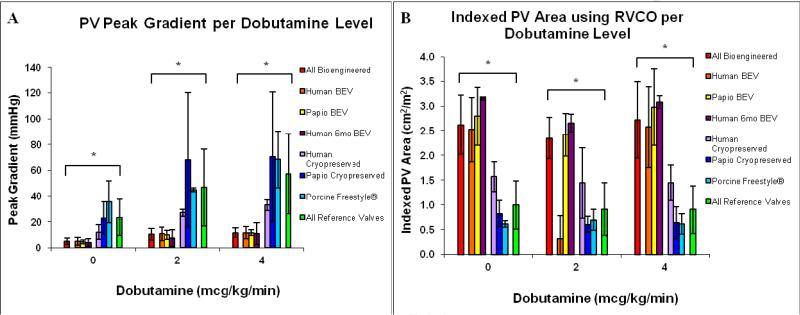

Figure 1. Dobutamine Echocardiography.

Dobutamine echocardiography results after chronic implantation of human and baboon bioengineered and control valves. Source species and process preparation for each group noted in figure. Porcine (light blue) were glutaraldehyde crosslinked stentless valves (Medtronic Freestyle®). Transvalvular gradients were uniformly lower for all bioengineered valves (red) at rest and during dobutamine challenge as compared to the clinical reference valves (green) (Panel A). The human bioengineered valves (orange) functionally had low gradients and normal indexed EOA at maximum dobutamine stimulation (Panel B). *p≤0.005. BEV=Bioengineered Valves.

Table 2.

Serum HLA antibody serial assays and corresponding valve cusp function by transesophageal echocardiography

| Valve Type | No. | Labscreen mixed HLA assay1 | Labscreen % PRA assay2 | Candidate HLA culprit specificities3,4 | C1q Complement | Echocardiography (Cusp)5,6 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | Class II | Class I | Class II | Class I | Class II | Thickness | Mobility | Regurgitation | |||||||

| Reference Valves | Result | Time | Result | Time | Result | Time | Result | Time | |||||||

| Porcine glutaraldehyde | 1 | + | wk 3 | - | N/A | 0% | N/A | 0% | N/A | none | none | - | thick | restricted | 0 |

| 2 | - | N/A | + | wk 10 | 0% | N/A | 0% | N/A | none | none | - | thick | restricted | 1+ | |

| Papio cryopreserved | 3 | ++ | wk 3 | ++ | wk 3 | 85% | wk 3 | 98% | wk 3 | A32, A29, A74, B18, B42, B27, B37, B38, B39, B47, B57 | DQ7, DQ8, DR11, DR13, DR14 | - | thick | restricted | 0 |

| 4 | + | wk 10 | ++ | wk 4 | 95% | wk 10 | 70% | wk 6 | A1, A10, A23, A24, A25, A3, A32, B48, B13, B62, B44, B45, B60 | DR1, DR10, D9, DR4, DQ7, DQ5, DQ8, DQ9 | + (62%) | thick | restricted | 2+ | |

| Human cryopreserved | 5 | ++ | wk 2 | ++ | wk 4 | 98% | wk 2 | 98% | wk 5 | Highly reactive | DR7, DQ6 | + (100%) | thin | restricted | 3+ |

| 6 | + | wk 4 | ++ | wk 3 | 60% | wk 6 | 100% | wk 4 | A2, A68, A69, B58 | Highly reactive | - | thick | normal | 1+ | |

| Papio 10 wk implant | 7 | - | N/A | - | N/A | - | - | - | N/A | none | none | - | thin | normal | 2+ |

| 8 | - | N/A | - | N/A | - | N/A | - | N/A | none | none | - | thin | normal | 2+ | |

| 9 | + | wk 6 | - | N/A | 65% | wk 6 | - | N/A | A25, A26, A33, A34, A32, A74, A23, A24, A66 | none | + (58%) | thin | normal | 2+ | |

| Bioengineered Valves | |||||||||||||||

| Human 10 wk implant | 10 | + | wk 9 | ++ | wk 2 | 76% | wk 9 | 100% | wk 4 | A24, B7, B8, B81, B48, B27, B42, B54, B60, B64, B65 | DR4 | + (25%) | mildly thickened | normal | 3+ |

| 11 | + | wk 1 | + | wk 8 | 96% | wk 1 | 14% | wk 8 | A25, A26, B48, B60 | DR7 Dr9 | - | thin | normal | 2+ | |

| 12 | + | wk 6 | + | wk 5 | 75% | wk 6 | 20% | wk 5 | A25, A29, A66, B81, B56, B54, B55, B57, B7, B42, B51, B53, B35 | DR7, DR9 | - | thin | normal | 2+ | |

| Human 6 mo implant | 13 | - | N/A | + | wk 6 | 0% | N/A | 100% | wk 7 | none | DR7, DR8, DR9, DR17 | - | thin | normal | 2+ |

| 14 | - | N/A | + | wk 9 | 0% | N/A | 100% | wk 9 | none | DR11, DR12, DR13, DR14, DR17, DR8 | - | thin | normal | 2+ | |

Porcine glutaraldehyde, papio cryopreserved and human cryopreserved valves are reference valves while papio 10 week, human 10 week and human 6 month implant valves decellularized and conditioned are termed bioengineered valves.

Results of the LabScreen® mixed assay are scored as positive (+; MFI >1000 units) or strongly positive (++; peak MFI > 7000 units), for the post-operative week at which the serum first measured as Ab positive.

Results of the LabScreen® % PRA assay are reported as the maximum PRA titer (%) for the post-operative week after the % PRA first exceeded 10%. Time points where the % PRAs were negative for the study duration are reported as N/A.

Results are the likely antigens responsible for HLA-I or-II sensitization as identified by reporting bead epitope sites.

Epitopes can be shared by multiple antigens so antibody specificities can arise against HLA antigens other than those actually provoking the response.

“Highly reactive” indicates an inability to assign specificities due to intense reactivity.

Cusps were designated as thickened when the thickness measured by TEE was ≥ 1.5 mm; mildly thickened = cusp thickness ≥ 1.2 mm. Cusp regurgitation scores represent function at pre-sacrifice exam: trace (1+), mild (2+) and moderate (3+).19

There was complete agreement on the measurement of cusp thickness by TEE and explant qualitative observations except for Animal #3 (compare to eTable 1).

Dobutamine Stress Echocardiography

Dobutamine stress testing demonstrated marked differences in EOA and EOAI between reference and bioengineered valves (Figure 1). Peak and mean transvalvular pressure gradients were consistently lower for all bioengineered valves. At maximum dobutamine stimulation, the reference valves had peak and mean pressure gradients of 44.5(76.0) mmHg and 29.5(49.0) mmHg, respectively. In contrast, the human bioengineered valves had functionally low valve gradients (12.0(12.0) mmHg peak and 7.0(8.0) mmHg mean) despite cardiac indexes ≥ 5 L/min/m2 at the maximum dobutamine stimulation (p≤0.005 for all comparisons). For all bioengineered valves, transvalvular gradients during stress echocardiography were comparable to those across native valves in each animal, suggesting the bioengineered valves were functionally equivalent to native valves. The geometric valve annulus diameters (Table 1) by direct TEE measurement after 10 weeks for bioengineered (1.76(0.54) cm and reference valves (1.75(0.52) were the same; P>0.05). Thus the reductions in EOA measured in reference valves were likely not due to anatomical shrinkage, but rather to increasing cuspal stiffness, restricted cusp opening and loss of conduit wall compliance.

Mixed Class I and II HLA Antibodies Screening Assay

The mixed screening assay accurately predicted whether Class I or II PRA titers would exceed 10% when measured by quantitative LABScreen® PRA % assay (Table 2). Both allogeneic and xenogeneic cryo reference valves provoked Class I&II antibodies, typically as “strongly positive”, beginning relatively early (weeks 1-6) after implantation. In contrast, 2/5 human and 2/3 baboon bioengineered valves did not provoke Class I antibodies. None of the bioengineered baboon valves provoked Class II antibodies while all human tissues did.

Class I and Class II % PRA Assay

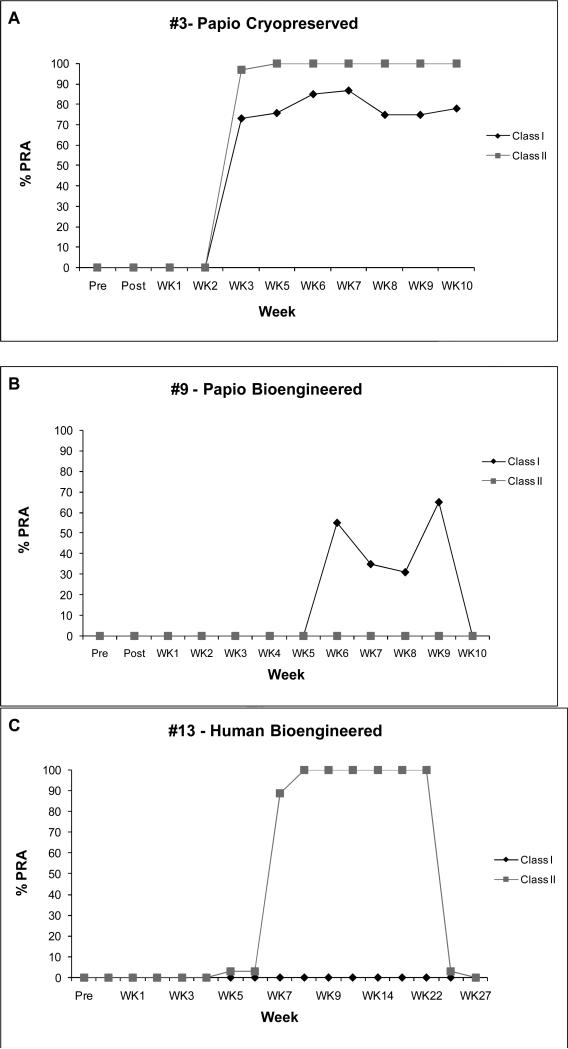

All cryopreserved donor valves provoked Class I&II titers exceeding 60% by week 10 (Table 2) regardless of species of origin. Baboon bioengineered valves were negative for both Class I&II elevations except for one animal (#9) that developed 75% Class I (and C1q+) by week 6 but which declined by week 10 to 47%. Two human bioengineered valves remained Class I negative (<10%) to six months, but all eventually provoked Class II antibodies. PRA time courses were variable (Figure 2): bioengineered valves that elicited positive PRA titers typically did so by 4 weeks and then returned to zero by 10 weeks, while cryopreserved valves (even allogeneic) tended to evoke more persistent elevations. Valves maintaining superior hemodynamics typically had absent or shorter elevations of PRA.

Figure 2. Examples of PRA Time Curves.

Panel A: Animal #3 received a cryopreserved allograft and developed both Class I&II PRA's by week 3, sustained through 10 weeks. Panel B: Animal #9 received a bioengineered allograft and did not elevate Class II, and was the only bioengineered allograft recipient in which Class I rose at all. Titer returned to zero by 10 weeks. Panel C: Animal #13 received a human bioengineered valve which provoked Class II antibodies at week 7, but returned to baseline by weeks 26 and 27; no Class I antibodies were detected. These serial measurements demonstrate the potential difficulties in interpretation of random isolated PRA titer measurements after tissue transplants.

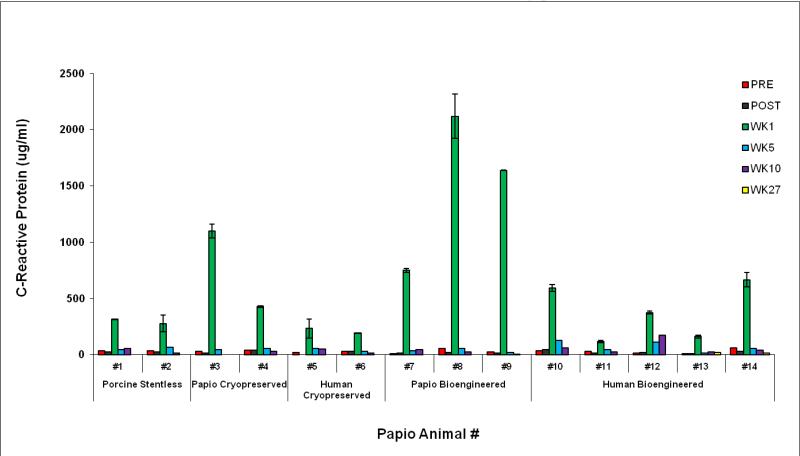

Complement Fixing Antibody, C-reactive Protein Assays

C1q binding Class I antibody titers were positive in four animals receiving four different valve types (Table 2). Elevated CRP titers consistently occurred only perioperatively (P=0.005). (eFigure2).

eFigure 2. C-reactive Protein titers.

C-reactive protein serum titers for each animal consistently peaked 1 week postoperatively indicating classic proinflammatory effects of surgery and cardiopulmonary bypass. Pre = preoperatively; Post = immediately after surgery.

Explant Pathology

Both human and baboon bioengineered valves appeared to have virtually normal cusps qualitatively except for one human valve in a strongly Class II+ and C1q+ recipient (#10) that was described as “slightly thickened”. By echo, this valve's leaflets were measured as “mildly thickened” (Table 2). Only one valve (#3 – cryopreserved) had discordant leaflet scoring between echo and explant observations (compare Tables and e1), although this particular valve did exhibit gross findings of inflammatory degradation with sinus wall thickening (Table 2). In contrast, all but one reference valve exhibited cusp thickening quantitatively by echo (eTable 1). Frank calcifications were not observed by radiographic examination in any of the explanted valves. Inflammatory histologic scores demonstrated some variability yet tended to correlate with the PRA titers (Table 2 and eTable1). With the exception of a single baboon valve, all cryopreserved valves elicited a marked inflammatory infiltrative response (mimicking clinical experience) while only two human bioengineered valves did. Immunohistochemical staining confirmed the presence of B-cells in these inflammatory infiltrates (eFigure3).

eTable 1.

Explant valve necropsy observations

| Valve Type | Animal ID Number | Pericardial Adhesions | Valve Conduit wall | Valve sinus wall | Valve cusps | Histologic inflammatory response score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porcine Glutaraldehyde1 | 1 | moderately severe | stiff | stiff, thick | very stiff, thick | marked |

| 2 | severe | rigid | stiff, thick | stiff, thick | marked | |

| Papio Cryopreserved | 3 | moderate | stiff, nodular suture line | nodules, scarring | thin | mild |

| 4 | severe | scarring at suture lines | stiff, thick | thick, contracted | marked | |

| Human Cryopreserved | 5 | moderately severe | no scar | no scar or calcium | thin, normal | marked |

| 6 | moderate | no scar | stiff, thick | stiff, thickened | marked | |

| Papio 10 wk implant | 7 | mild | normal | normal | thin, normal | minimal – mild |

| 8 | mild | normal | normal | thin, normal | minimal – mild | |

| 9 | mild | normal | fibrin deposits | thin, normal | minimal – mild | |

| Human 10 wk implant | 10 | moderate | thickened | inflammatory adventitia | slightly thickened | marked |

| 11 | mild | normal | normal | thin, normal | moderate | |

| 12 | moderate | small nodule at STJ2 | normal to slight thickening | thin, pliable | marked | |

| Human 6 mo implant | 13 | mild | normal | normal | thin, normal | moderate |

| 14 | mild | normal | normal | thin, normal | minimal – mild |

Porcine glutaraldehyde, papio cryopreserved and human cryopreserved valves are reference valves while papio 10 week, human 10 week and human 6 month implant valves are bioengineered valves.

Porcine glutaraldehyde valve inflammatory infiltrates were limited to the adventitia only.

STJ = sino-tubular junction.

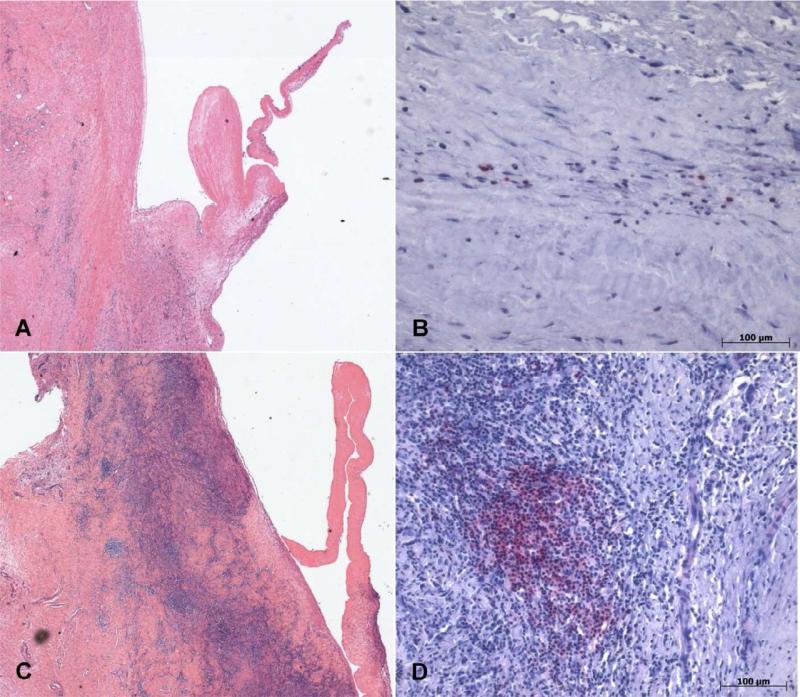

eFigure 3. Histopathology.

Histologic and immunohistochemical stains of pulmonary valves. A, Histologic section of cryopreserved human pulmonary valve explanted at 10 weeks (H&E, magnification 2.5x) exemplifying a microscopic field that would rate a mild inflammation score. Elsewhere in the specimen, areas of marked inflammation were observed, thus the overall score for this valve explant was “marked” (Animal #5, Table 2). B, Immunohistochemical stain for B-cells (red, alkaline phosphatase, magnification 10x) within the conduit wall inflammatory infiltrate shown in Panel A. C, Histologic section of cryopreserved papio pulmonary valve explanted at 10 weeks (H&E, magnification 2.5x) exemplifying a score of “marked” inflammation (Animal #4). D, Immunohistochemical stain for B-cells (red, alkaline phosphatase, magnification 10x) within the inflammatory infiltrate in the conduit of PRA+ recipient in Panel C.

DISCUSSION

The key findings of this study include: 1) bioengineering using valve decellularization and conditioning reduces antigenicity and prolongs normal functional valve performance especially well for baboon (allogeneic) but also for human (xenogeneic) sourced valve scaffolds; 2) the intensity of immune and inflammatory responses is correlated with valve functional durability; 3) prolonged and higher HLA titers appear to predict accelerated functional degradation; 4) C1q+ complement fixing antibodies were provoked by four different test valves, all developed 2+ to 3+ valve regurgitation; 5) technical implant surgery in baboons is analogous to human clinical surgery; 6) development of HLA antibodies in baboons can be quantified with commercially available solid state assays used in transplantation surgery. Our rationale for selecting the baboon was similarity to humans in ontogeny, phylogeny, immunology (eg, 4 IgG subclasses, complement fixation, macrophage, T and B cell functions), absence of α-Gal epitope, similar semilunar valve microstructure, semi-upright posture, lack of susceptibility to simian herpes B virus, and robust tolerance of cardiopulmonary bypass.18 Our data suggest that bioengineered cross species human to baboon valve scaffold transplants are different immunologically (eg, provoking Class II+ antibodies), than allo-transplants, but functionally much less provocative than cryopreserved valves of either species.9

Valve Functional Performance Correlates with Markers of HLA Mismatch

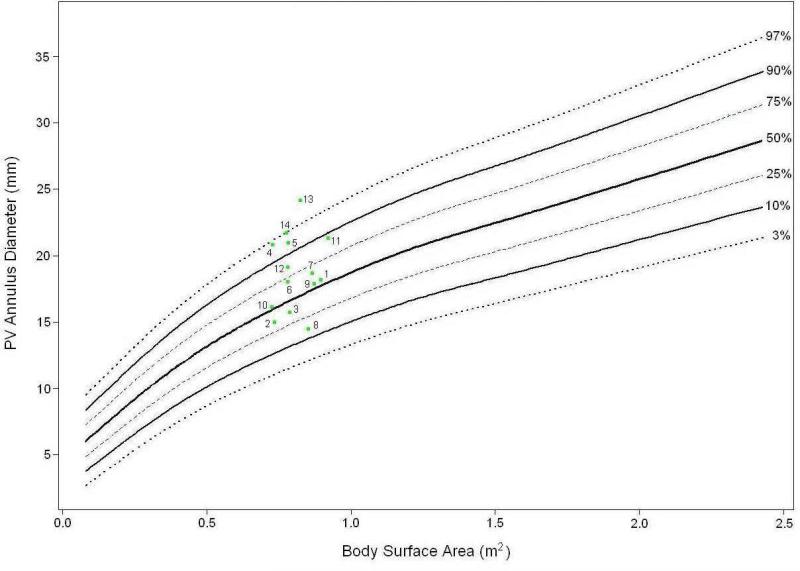

The baboon valve diameters as measured at implant scaled allometrically to normalized (BSA) pediatric valve annulus diameters with values similar to human (Figure 3). The indexed effective valve orifice areae increased by the time of explant for bioengineered valves (papio ↑ 29%, human ↑ 19%), but decreased for cryopreserved (papio ↓ 68%, human ↓ 57%) and porcine (↓ 76%). The differences in resting pressure gradients across the clinical reference valves versus the bioengineered valves are likely under reported since the cardiac outputs at 10 weeks were generally higher in the animals with bioengineered valves. There was no echocardiographic evidence of impending bioengineered valve stenotic failure as transvalvular gradients did not increase over time, nor did calculated valve EOA's decrease significantly at either 10 weeks or 26 weeks post-implant. The dobutamine driven elevated cardiac outputs only provoked physiologic flow gradients comparable to expected values for human native valves. In contrast, echocardiographic evidence of critical dysfunction with decreasing EOA was manifest in all 3 types of reference valves even by 10 weeks suggesting that the baboon is a severe test species and robust model for such assessments. Dysfunction by TEE correlated with measurements of more intense PRA responses. Only one bioengineered valve (#10) demonstrated cuspal thickening. This recipient had a high Class II+ response and was Class I C1q+. The two valves that developed leaflet dysfunction with greater than 2+ regurgitation (#5, #10) were both associated with higher PRA titers and C1q+ antibodies. To our knowledge, correlation of the appearance of C1q complement fixing antibodies and transplanted biological valve dysfunction has not previously been reported. Intuitively, C1q+ antibodies may be implicated in more consequential antibody mediated clinical tissue transplant rejection and may thus be an observation perhaps worthy of evaluation clinically in homograft valve recipients exhibiting accelerated valved conduit dysfunction. Thus various indicators of the severity of provoked immunogenic inflammatory responses appeared to correlate with the severity of valve dysfunction, which decellularization and conditioning appeared to mitigate. These observations corroborate current mechanistic theories emphasizing the immune and inflammatory pathogenesis of valve degradation..20

Figure 3. Implanted Valve Sizes.

Nomogram of BSA normalized human pediatric pulmonary valve annulus diameters derived from 14,128 normal pediatric transthoracic echocardiograms archived in the Children's Mercy Cardiac Database and on which the 14 implanted valve annulus diameters measured by transesophageal echocardiography at baseline after implant surgery (day 0) are graphed (green dots). Note that all but 3 were above the 50% median; the smallest valve for the recipient size was a baboon bioengineered (#8). An inadvertent “downsizing” bias would not explain the greater functional deterioration of the cryopreserved valves. Numbers identify recipient animals for each valve as identified in Table 2.

Baboon and human HLA molecules have been compared and are almost 90% identical with cross-species differences concentrating in positions typically demonstrating polymorphisms in human alleles that serve to activate T cells.21 Cryopreserved valves provoked strong HLA I and II responses regardless of donor species. Interestingly, in the baboon model, as in human transplantation, suspect culprit antigen specificities tended to group with known shared epitopes (eg, B8 with B64 and B65; DQ7 with DQ8; B7 with B42).22 The duration of the PRA elevations was more sustained for cryo-implants, but when occurring in recipients of bioengineered valves, the transient elevations, were as brief as five weeks duration, highlighting the need for well timed blood draws to identify sensitization. (Figure 2) This has significant implications for the interpretations of PRA titers in older reports and assay timing in future clinical studies.

Limitations

The 10 week duration of these studies was too short to adequately assess in situ autologous in vivo recellularization but was intentionally chosen to best capture early immune-inflammatory responses to correlate with echo function and PRA titers. Only two recipients with human bioengineered scaffolds were kept to 6 months; both had persistent excellent valve functionality without MHCI+ or C1q+ antibodies, suggesting that when antigenicity is minimized, longer term hemodynamic performance studies are feasible. Why antigenicity can be variably retained at all in decellularized valves (albeit typically mild) is not clear from these studies. All mammalian semilunar valves have microscopic interdigitations of ventricular muscle deep within the fibrous annulus where some fragmentary cell remnants could remain despite 97-99% removal of DNA and other indicators of decellularization effectiveness. Epitopes could be associated with extracellular matrix (as seen with α-gal). Alternatively, mass spectrometry of detergent decellularized equine carotid arteries has revealed small residuals of over 300 cell associated proteins.23 These could include epitopes accounting for some retention of xenotransplant immunogenicity despite absence of cell fragments. Our complete cardiac experience with baboons has provided some unique observations (eTable 2) that may aid other investigators considering this species for cardiac preclinical studies.18 Cardiac surgery studies in baboons cost 500% more than sheep. As in this study, this limits feasible animal numbers per test group.

eTable 2.

Observed differences between humans and baboons that may impact cardiovascular modeling

| Observation | Human | Baboon | Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | Right sided | Transverse | Precludes retroflexed gastric TEE views or subxiphoid needle approaches |

| Cardiac orientation | Normal = levocardia | Normal = levocardia | Base of Apex alignment and orientation within the chest is similar to human and not transversely situated as in four-legged food stock animals |

| Right ventricle wall thickness | “Normal” | Thinner | Less myocardial reserve; poorly tolerates distention, infundibular incisions, or acutely increased afterloads; may be useful for Fontan modeling |

| Left ventricle muscle mass | “Normal” | Thicker with essentially concentric hypertrophy as compared to human | Diastolic stiffness. Narrow left ventricular outflow tract; optimized cardioplegia strategies required |

| Right coronary ostia | Typically smaller than left main | Miniscule | Smallest coronary perfusion cannulae (1mm) cannot cannulate |

| Splanchnic venous reserve | Limited | Large blood volume for autotransfusion via autonomic reflexes | Careful weaning from cardiopulmonary bypass with surgeon and TEE chamber volume monitoring to avoid acute cardiac distention. Avoid “light” anesthesia. After CPB, transfuse pump blood residual slowly |

| Arterial wall thickness | Large lumen to wall thickness ratio | Very thick and stiff and hyper - vasoconstrictive | Peripheral arterial cannulation precluded; not likely a good species for transvascular catheter methods; enhanced fight/flight responses; older baboons develop hypertension and presbycardia |

| Body mass | Evolves with age from upper body to lower body dominant | Upper body dominant | BSA calculations should be based on formulae that assume less contribution from lower body mass (eg, Haycock Formula) when normalizing measurement to BSA (eg, indexing EOA of valves) |

| Demeanor | Age dependent calm | Aggressive potentially bellicose | All interventions under sedation/anesthesia; perioperative management and husbandry by experts with proper caging, socialization procedures, management techniques, etc. required |

Note: Regional Primate Centers are supported by NIH Comparative Medicine Programs (formally in the National Center for Research Resources) and tasked with optimizing breeding, experimental modeling, availability, medical knowledge for many Old and New World species for use in biomedical research; we found it preferable to travel as a team and operate onsite at the Texas Biomedical Research Institute where subhuman primate veterinary medicine and husbandry are optimized. However, this adds to the additional limitation of expense.

Tissue Engineered Valves and Preclinical Testing with Baboons

The need for chronic animal models that are especially relevant to humans has been identified by multiple authorities as critical to “bench to bedside” translation of tissue engineering strategies.1,2,24 A principal tenet in the field of tissue engineering is that the more a re-established cellular population resembles normal tissue, in cell density, location and phenotypes, the more likely it is that such tissues will effectively mimic native, particularly with the capacity for constructive and adaptive remodeling. One pathway to a “personal” heart valve would be to “tissue engineer” by repopulating a decellularized allogeneic scaffold with the putative recipient's own cells. This could be achieved by one or more strategies: 1) preimplant direct bioreactor cell seeding (classical tissue engineering); 2) employing physical, chemical, and biological conditioning treatments of scaffold matrix to promote cell adhesion and in-migration in vivo as an in situ postimplantation autologous process; 3) introducing into the scaffold “homing” molecules (“breadcrumbs” strategy) that accelerate in vivo cell seeding.6, 25 In this study, Method 2 was utilized without ex vivo cell seeding. However, regardless of technique, the base scaffold must be minimally pro-inflammatory or the result may be scar tissue not physiologic, healthy, reconstituted tissue structures. Previous research has demonstrated that autologous cell in-migration, even without preseeding, effectively repopulates decellularized conduit vascular walls.10 Cuspal re-endothelialization is improved with conditioning, but the matrix of all semilunar cusps of such valve scaffolds are not consistently (ie, all three cusps every time) fully repopulated with valve interstitial cells by just autologous postsurgical in vivo cell migration and proliferation.10, 16 This is an important distinction as repopulated cells are needed to provide matrix remodeling protein synthesis capacity for growth and repair, which suggests enhanced recellularization strategies could be useful.14, 25 Development of viable personal heart valves using any combination of these strategies will be strengthened by assessment methods designed to emulate putative clinical paradigms as closely as possible. Both clinical hemodynamic failure modes for biological replacement valved conduits (insufficiency due to leaflet dysfunction and stenosis with progressive gradients) were replicated in this model. Thus, the baboon could be useful for both mechanistic studies and as a bridge from traditional large animals to clinical trials of tissue engineered cardiovascular constructs.

The bioengineering processes employed appeared to reduce antigenicity of semilunar valve scaffold tissues and prolong functional performance, especially within species, but also across genera from two Primate Families of high genomic congruence. Absent or evolving postoperative MHC antibody titers could be assessed and appeared to correlate with functional measurements. This experience suggests that the baboon model may be useful in the future for chronic functional testing of clinical prototype human bioengineered or even “tissue engineered” replacement valves for which human decellularized scaffolds could be recellularized with recipient (ie, baboon) cells to closely simulate clinical paradigms.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a subgrant award from National Institutes of Health, Southwest National Primate Research Center base grant P51RR013986-11.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dekant W, Testai E. Opinion on: The need for non-human primates in biomedical research, production and testing of products and devices. SCHER: Scientific Committee on Health and Environmental Risks. 2009:20–21. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trantina-Yates A, Weissenstein C, Human P, Zilla P. Stentless bioprosthetic heart valve research: Sheep versus primate model. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:S422–427. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)02502-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber B, Scherman J, Emmert MY, Gruenenfelder J, Verbeek R, Bracher M, Black M, Kortsmit J, Franz T, Schoenauer R, Baumgartner L, Brokopp C, Agarkova I, Wolint P, Zund G, Falk V, Zilla P, Hoerstrup SP. Injectable living marrow stromal cell-based autologous tissue engineered heart valves: First experiences with a one-step intervention in primates. European Heart Journal. 2011;32:2830–2840. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atala AE. Principles of regenerative medicine. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2011. Chapter 63: Overview of the fda regulatory process. pp. 1145–1168. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flameng W, Jashari R, De Visscher G, Mesure L, Meuris B. Calcification of allograft and stentless xenograft valves for right ventricular outflow tract reconstruction: An experimental study in adolescent sheep. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141:1513–1521. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.08.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper DK. Outwitting evolution. Xenotransplantation. 2010;17:171–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2010.00595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hopkins R. Resolution of the conflicting theories of prolonged cell viability: In: Hopkins ra., editor. Cardiac reconstructions with allograft tissues. Springer; New York: 2005. pp. 184–189. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baskett RJ, Nanton MA, Warren AE, Ross DB. Human leukocyte antigen-dr and abo mismatch are associated with accelerated homograft valve failure in children: Implications for therapeutic interventions. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;126:232–239. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(03)00210-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hopkins RA, Jones AL, Wolfinbarger L, Moore MA, Bert AA, Lofland GK. Decellularization reduces calcification while improving both durability and 1-year functional results of pulmonary homograft valves in juvenile sheep. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2009;137:907–913. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quinn RW, Hilbert SL, Bert AA, Drake BW, Bustamante JA, Fenton JE, Moriarty SJ, Neighbors SL, Lofland GK, Hopkins RA. Performance and morphology of decellularized pulmonary valves implanted in juvenile sheep. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2011;92:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown JW, Ruzmetov M, Eltayeb O, Rodefeld MD, Turrentine MW. Performance of synergraft decellularized pulmonary homograft in patients undergoing a ross procedure. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:416–422. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.10.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rieder E, Seebacher G, Kasimir M-T, Eichmair E, Winter B, Dekan B, Wolner E, Simon P, Weigel G. Tissue engineering of heart valves: Decellularized porcine and human valve scaffolds differ importantly in residual potential to attract monocytic cells. Circulation. 2005;111:2792–2797. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.473629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruffer A, Purbojo A, Cicha I, Glockler M, Potapov S, Dittrich S, Cesnjevar RA. Early failure of xenogenous de-cellularised pulmonary valve conduits -- a word of caution! Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;38:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hopkins R. Cardiac surgeon's primer: Tissue-engineered cardiac valves. Seminars in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery: Pediatric Cardiac Surgery Annual. 2007;10:125–135. doi: 10.1053/j.pcsu.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frank BS, Toth PB, Wells WK, McFall CR, Cromwell ML, Hilbert SL, Lofland GK, Hopkins RA. Determining cell seeding dosages for tissue engineering human pulmonary valves. J Surg Res. 2012;174:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.11.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quinn RW. Enhanced autologous re-endothelialization of decellularized and extracellular matrix conditioned allografts implanted into the right ventricular outflow tracts of juvenile sheep. Cardiovascular Engineering and Technology. Published Online 02 February 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Converse GL, Armstrong M, Quinn RW, Buse EE, Cromwell ML, Moriarty SJ, Lofland GK, Hilbert SL, Hopkins RA. Effects of cryopreservation, decellularization and novel extracellular matrix conditioning on the quasi-static and time-dependent properties of the pulmonary valve leaflet. Acta Biomaterialia. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whittaker C, Grist G, Bert A, Brasky K, Neighbors S, McFall C, Hilbert SL, Drake WB, Cromwell M, Mueller B, Lofland GK, Hopkins RA. Pediatric cardiopulmonary bypass adaptations for long-term survival of baboons undergoing pulmonary artery replacement. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2010;42:223–231. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zoghbi WA, Chambers JB, Dumesnil JG, Foster E, Gottdiener JS, Grayburn PA, Khandheria BK, Levine RA, Marx GR, Miller FA, Jr., Nakatani S, Quinones MA, Rakowski H, Rodriguez LL, Swaminathan M, Waggoner AD, Weissman NJ, Zabalgoitia M. Recommendations for evaluation of prosthetic valves with echocardiography and doppler ultrasound. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:975–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rajamannan NM, Evans FJ, Aikawa E, Grande-Allen KJ, Demer LL, Heistad DD, Simmons CA, Masters KS, Mathieu P, O'Brien KD, Schoen FJ, Towler DA, Yoganathan AP, Otto CM. Calcific aortic valve disease: Not simply a degenerative process. Circulation. 2011;124:1783–1791. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.006767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDevitt H. Evolution of mhc class ii allelic diversity. Immunol Rev. 1995;143:113–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1995.tb00672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cai J, Terasaki PI, Mao Q, Pham T, El-Awar N, Lee JH, Rebellato L. Development of nondonor-specific hla-dr antibodies in allograft recipients is associated with shared epitopes with mismatched donor dr antigens. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:2947–2954. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boer U. The effect of detergent-based decellularization procedures on cellular proteins and immunogenicity in equine carotid artery grafts. Biomaterials. 2011:9730–9737. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hjortnaes J, Bouten CV, Van Herwerden LA, Grundeman PF, Kluin J. Translating autologous heart valve tissue engineering from bench to bed. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2009;15:307–317. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEB.2008.0565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jordan JE, Williams JK, Lee SJ, Raghavan D, Atala A, Yoo JJ. Bioengineered self-seeding heart valves. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143:201–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]