Abstract

During the past decade, the kisspeptin system has been identified in various vertebrates, leading to the discovery of multiple genes encoding both peptides (Kiss) and receptors (Kissr). The investigation of recently published genomes from species of phylogenetic interest, such as a chondrichthyan, the elephant shark, an early sarcopterygian, the coelacanth, a non-teleost actinopterygian, the spotted gar, and an early teleost, the European eel, allowed us to get new insights into the molecular diversity and evolution of both Kiss and Kissr families. We identified four Kissr in the spotted gar and coelacanth genomes, providing the first evidence of four Kissr genes in vertebrates. We also found three Kiss in the coelacanth and elephant shark genomes revealing two new species, in addition to Xenopus, presenting three Kiss genes. Considering the increasing diversity of kisspeptin system, phylogenetic, and synteny analyses enabled us to clarify both Kiss and Kissr classifications. We also could trace back the evolution of both gene families from the early steps of vertebrate history. Four Kissr and four Kiss paralogs may have arisen via the two whole genome duplication rounds (1R and 2R) in early vertebrates. This would have been followed by multiple independent Kiss and Kissr gene losses in the sarcopterygian and actinopterygian lineages. In particular, no impact of the teleost-specific 3R could be recorded on the numbers of teleost Kissr or Kiss paralogs. The origin of their diversity via 1R and 2R, as well as the subsequent occurrence of multiple gene losses, represent common features of the evolutionary histories of Kiss and Kissr families in vertebrates. In contrast, comparisons also revealed un-matching numbers of Kiss and Kissr genes in some species, as well as a large variability of Kiss/Kissr couples according to species. These discrepancies support independent features of the Kiss and Kissr evolutionary histories across vertebrate radiation.

Keywords: kisspeptin, kisspeptin receptor, phylogeny, synteny, evolutionary history, spotted gar, coelacanth, European eel

Introduction

As increasing vertebrate genomes have been explored, the understanding of their structure and evolution has progressed in parallel. Indeed, the comparison of their gene organization shed light on various large-scale genomic events that occurred along vertebrate radiation. Among those events, in the early stages of their history, vertebrates experienced two rounds of whole genome duplication (1R and 2R), resulting in fourfold-replicated genomes (Dehal and Boore, 2005; Van de Peer et al., 2010). These two events can be traced through the study of gene families currently presenting up to four paralogs. In addition, the comparison of teleost genomes with other vertebrate genomes revealed a teleost-specific third round of whole genome duplication (3R), resulting in up to eight paralogs in the same gene family in this lineage (Amores et al., 1998; Meyer and Van de Peer, 2005; Kasahara et al., 2007).

In 1996, kisspeptin was first discovered as an anti-metastatic peptide in human carcinoma (Lee et al., 1996). In 2001, the orphan receptor GPR54 was identified as the cognate receptor of kisspeptin (Kotani et al., 2001; Muir et al., 2001). Two years later, both kisspeptin (Kiss) and its receptor (Kissr) were demonstrated as key players of the reproductive function in mammals (de Roux et al., 2003; Funes et al., 2003; Seminara et al., 2003). They act up-stream in the gonadotropic axis mediating gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) and steroid effects on gonadotropin secretion, and are considered as major puberty gatekeepers and reproduction regulators (Pinilla et al., 2012). To date, the kisspeptin system has been identified in various vertebrate species, leading to the discovery of multiple genes encoding Kiss as well as multiple genes encoding Kissr (Biran et al., 2008; Felip et al., 2009; Kitahashi et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2009).

Concerning Kiss and Kissr diversity, contrasting situations are found in the different vertebrate phyla. Indeed, in eutherian species, one single gene, named Kiss1r, encodes the kisspeptin receptor and one single gene, named Kiss1, encodes kisspeptin. In prototherians, such as platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus), two Kiss, and two Kissr are present (Lee et al., 2009). To date, in teleosts, two situations have been reported. One Kiss gene and one Kissr gene are present in some species such as fugu (Takifugu niphobles), tetraodon (Tetraodon nigroviridis), and stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus). In contrast, a second Kiss as well as a second Kissr genes have been characterized in some species including zebrafish (Danio rerio; Biran et al., 2008), goldfish (Carassius auratus; Li et al., 2009), medaka (Oryzias latipes; Lee et al., 2009), and striped bass (Morone saxatilis; Zmora et al., 2012). Until recently the maximum number of Kiss and Kissr genes was found in an amphibian species, the Xenopus (Xenopus tropicalis), with three paralogs of each gene. On the opposite, in birds (chicken, Gallus gallus, zebra finch, Taeniopygia guttata, and turkey, Meleagris gallopavo) neither Kiss nor Kissr have been found. So far, in all these cases, a matching number of Kiss and Kissr genes had been reported, leading to the suggestion of the occurrence of “paired Kiss/Kissr” systems in vertebrates (Kim et al., 2012).

The recent publications of genomes from representative species of key phylogenetic positions makes it possible to revisit the diversity, the origin and the evolution of Kiss and Kissr in vertebrates. These genomes include a chondrichthyan, the elephant shark (Callorhinchus milii; Venkatesh et al., 2007), a representative of early sarcopterygian, the coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae, coelacanth genome project, Broad Institute), a non-teleost actinopterygian, the spotted gar (Lepisosteus oculatus; Amores et al., 2011), and an early teleost (elopomorphe), the European eel (Anguilla anguilla; Henkel et al., 2012). Gene characterization, phylogenetic, and syntenic analyses allowed us to provide new insights on the respective evolutionary histories of Kiss and Kissr families. Furthermore, the comparison of proposed Kiss and Kissr phylogenetic histories highlighted common processes as well as divergent events leading to discuss the existence of conserved Kiss/Kissr couples among the various vertebrate lineages.

Materials and Methods

Genomic databases

The following genomic databases were investigated:

– the chicken genome1,

– the coelacanth genome2,

– the elephant shark genome3,

– the European eel genome4,

– the human genome5,

– the lizard genome6,

– the platypus genome7,

– the sea lamprey genome8,

– the spotted gar genome9,

– the stickleback genome10,

– the Xenopus genome11,

– the zebrafish genome12.

TBLASTN search

The TBLASTN algorithm of the CLC DNA Workbench software (CLC bio, Aarhus, Denmark) was used on the European eel genome database and the elephant shark genome database. The TBLASTN algorithm (search sensitivity: near exact matches) of the e!ENSEMBL website13 was used on the coelacanth and spotted gar genomic databases.

Gene predictions

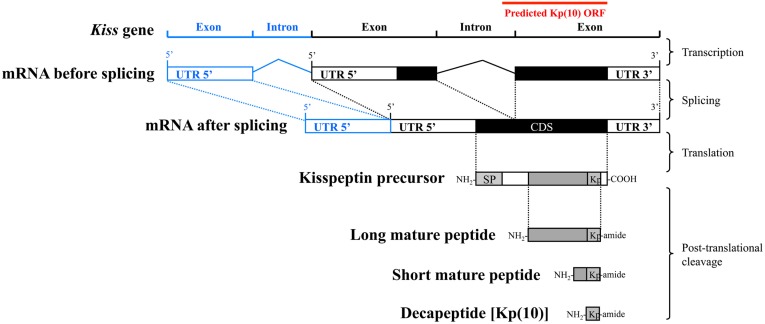

Considering that Kissr gene structure as well as coding sequences (CDS) are well conserved among vertebrate species, it was possible to predict the exon and intron sequences for new Kissr genes (Pasquier et al., 2012). The splicing junctions were predicted using the empirical nucleotidic splicing signatures, i.e., intron begins with “GT” and ends with “AG.” Concerning Kiss structures, the fact that their CDS are split on two exons (Figure 1), appear to be conserved across vertebrates (for review: Tena-Sempere et al., 2012). However, they are highly variable among species, except for the sequence encoding the Kp(10) localized on the final exon (Figure 1). Therefore, only this Kp(10) conserved sequence can be predicted when investigating new genomes. This small sequence was used to identify the open reading frame (ORF) encompassing a part of the putative Kiss final exon and a part of the putative intron sequence (Figure 1). We therefore focused on this ORF encompassing the sequence encoding Kp(10), in the various genomes. The ORFs of the European eel, the coelacanth, the spotted gar, and the elephant shark, were determined using ORF finder tool of the CLC DNA Workbench software.

Figure 1.

Main steps leading from the Kiss gene to the Kp(10) peptide. ORF, open reading frame; UTR, un-translated region; CDS, coding sequence; SP, signal peptide; Kp, mature kisspeptin. Predicted ORF sequence containing Kp(10) is represented as a red line. The intron and exon represented in blue have been observed in some mammalian Kiss1 genes including human Kiss1, pig Kiss1, and mouse Kiss1.

Syntenic analyses

The synteny analyses of the eel genomic regions were manually performed using CLC DNA Workbench 6 software and the European eel genome database. The analyses of the spotted gar genomic regions were performed using the preliminary gene annotation of the genome assembly LepOcu1 generated by Ensembl release 67. Synteny maps of the conserved genomic regions in human, platypus, lizard (Anolis carolinensis), Xenopus, zebrafish, medaka, stickleback, tetraodon, and coelacanth, as well as of the corresponding region in chicken, G. gallus, were performed using the PhyloView of Genomicus v67.01 web site14 (Muffato et al., 2010).

Results and Discussion

As one of the aims of this study was to compare the Kiss and Kissr histories, we first propose to make a short overview of our recent findings concerning the diversity, classification, and origin of Kissr gene family. Then, we will expose and discuss our new findings concerning Kiss family. Finally, we will compare and discuss the Kiss and Kissr evolutionary histories in order to get a better understanding of the kisspeptin system evolution.

Diversity and evolutionary history of Kissr in vertebrates

Diversity and classification of Kissr

New advances in Kissr gene characterization

Recently, we described three Kissr genes in the genome of a basal teleost, the European eel, providing the first evidence of the existence of three Kissr genes in a teleost species (Pasquier et al., 2012). Furthermore, we described four Kissr in the genome of a non-teleost actinopterygian, the spotted gar, as well as in the genome of a basal sarcopterygian, the coelacanth (Pasquier et al., 2012). This provided the first evidence for four Kissr genes in vertebrate species and revealed a larger diversity of Kissr than previously described.

So far, no Kissr sequence has been reported in chondrichthyans. Our search in the elephant shark genome has only led to the identification of multiple partial sequences, corresponding at least to two Kissr (unpublished data). Ongoing sequencing of other chondrichthyan genomes, such as dogfish (Scyliorhinus canicula), may provide more insights into the Kissr diversity in the sister group of osteichthyans.

Phylogeny, synteny, and classification of Kissr

Phylogenetic analysis of 51 peptidic Kissr sequences clustered the osteichthyan Kissr into four clades, each one encompassing a coelacanth and spotted gar Kissr (Pasquier et al., 2012). Clade-1 mainly encompassed mammalian Kissr including human Kiss1r, as well as Xenopus Kissr-1a, European eel Kissr-1, spotted gar Kissr-1, and coelacanth Kissr-1. Clade-2 mainly encompassed teleost Kissr including European eel Kissr-2, as well as amphibian, spotted gar, and coelacanth Kissr-2. Clade-3 encompassed a few teleost Kissr including European eel Kissr-3 as well as Xenopus Kissr1b, spotted gar, and coelacanth Kissr-3. Clade-4 encompassed two early osteichthyan (spotted gar and coelacanth) Kissr-4 and two tetrapod Kissr (lizard and platypus; Pasquier et al., 2012).

Synteny analysis of Kissr neighboring genes, performed on 11 representative vertebrate species including the European eel, coelacanth, and spotted gar, fully supported the phylogenetic repartition of Kissr in four clades. Based on this classification, we proposed a new nomenclature of the Kissr family (Kissr-1, Kissr-2, Kissr-3, and Kissr-4; Pasquier et al., 2012).

Evolutionary history of Kissr

Origin of Kissr diversity via 1R and 2R

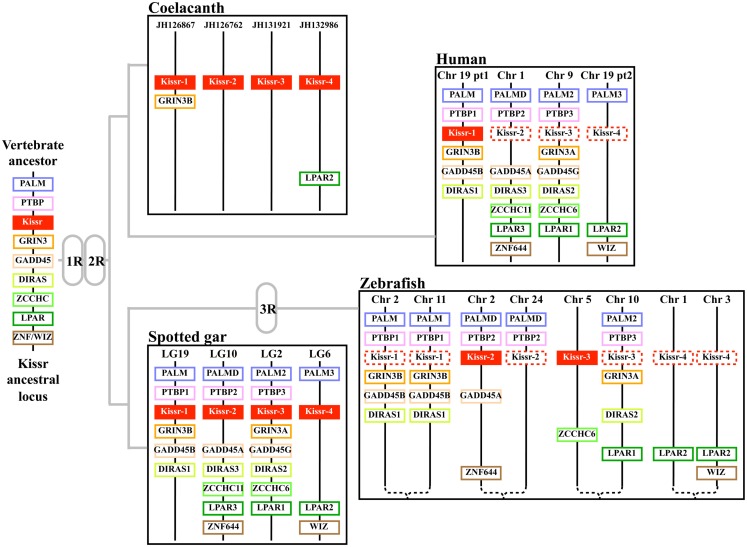

Synteny analysis revealed that the four Kissr neighboring genomic regions were highly conserved, each presenting paralogs from eight gene families, i.e., PALM, PTBP, GRIN3, GADD45, DIRAS, ZCCHC, LPAR, ZNF644/WIZ (Pasquier et al., 2012). The hypothesis of the potential existence of four Kissr paralogons in vertebrates had been previously raised by Lee et al. (2009) and Kim et al. (2012), although only a maximum of three Kissr genes had been discovered at that time. Our finding of four Kissr genes, located on four paralogous genomic regions, in coelacanth and spotted gar, provides direct evidence validating this former hypothesis. These four Kissr paralogons likely resulted from the two successive genomic duplications (1R and 2R) of a single ancestral genomic region (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proposed origin of osteichthyan Kissr tetra-paralogons. The paralogous genes of each of the eight identified families delineate four paralogons in the spotted gar, coelacanth, and human genomes and a duplicated tetra-paralogon in the zebrafish genome. This suggests a common origin of the four Kissr before the two whole genome duplication rounds (1R and 2R) which occurred in the early vertebrate history. This also suggests no impact of the teleost-specific 3R on Kissr number in current teleosts. Chr, chromosome; LG, linkage group.

The currently available data led to a polytomy of the four Kissr clades. This polytomy did not allow to fully solve the homology relationships between the four Kissr resulting from the 2R (Pasquier et al., 2012). A recent study proposed the phylogenetic reconstruction of the PALM family (Hultqvist et al., 2012). The study of these genes, located in the vicinity of Kissr genes, allows us to infer further relationships between the four Kissr. We can thus hypothesize that Kissr-1 and Kissr-3, on one side, and Kissr-2 and Kissr-4, on the other side, could be sister genes resulting from the 2R.

Recently, one study proposed the reconstruction of 10 proto-chromosomes of the ancestral vertebrate karyotype and their linkage to the corresponding tetra-paralogons in the human genome (Nakatani et al., 2007). Considering our localization of the four Kissr syntenic regions in the human genome, we can hypothesize that the corresponding tetra-paralogons resulted from the duplications of one single region localized on the proto-chromosome-A of the vertebrate ancestor (Pasquier et al., 2012).

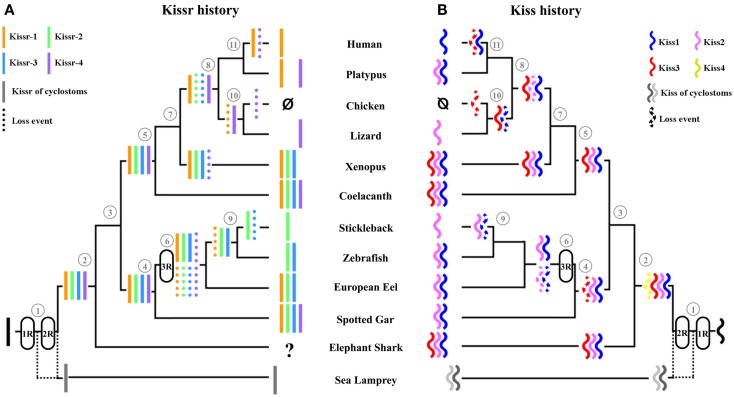

A subsequent history of Kissr losses

Since the spotted gar and the coelacanth are the only two vertebrate species in which we discovered four paralogous Kissr, we can hypothesize multiple Kissr loss events to explain the status of this receptor in current vertebrates (Figure 3A). In the sarcopterygian lineage, Kissr-4 may have been lost in amphibians, while Kissr-1 and Kissr-2 would have been lost in early amniotes. Subsequent additional losses may have led to the presence of only Kissr-1 in eutherian mammals and to the absence of any Kissr in birds.

Figure 3.

Current status and proposed evolutionary history of Kissr genes (A) versus Kiss genes (B). (1) Vertebrates, (2) gnathostomes, (3) osteichthyans, (4) actinopterygians, (5) sarcopterygians, (6) teleosts, (7) tetrapods, (8) amniotes, (9) euteleosts, (10) diapsides, (11) mammals. The names of the current representative species of each phylum are given at the end of the final branches, together with the symbol of the Kiss and Kissr genes they possess. These hypotheses assume the presence of four Kiss and four Kissr paralogs in the vertebrate lineage resulting from the two rounds of vertebrate whole genome duplication. Multiple subsequent gene loss events are indicated in the various lineages.

Considering the presence of four Kissr in a non-teleost actinopterygian, the spotted gar, the teleost-specific 3R could have resulted in the potential existence of up to eight Kissr genes. However, we only found three Kissr in the European eel, representing the current maximum number of this gene in teleosts. Furthermore, each eel Kissr is orthologous to a different tetrapod Kissr, supporting the absence of any teleost-specific Kissr. Synteny analysis demonstrated that each of the four Kissr paralogous genomic regions, present in the spotted gar, was duplicated in zebrafish, in agreement with the 3R. This analysis also indicated that all 3R-copies of Kissr were lacking in the corresponding duplicated regions (Figure 2). This suggests an early loss of duplicated Kissr genes, which would have suppressed the impact of the 3R on the number of Kissr in teleosts (Figure 3A). Additional successive deletions may have led to the presence of three Kissr in a basal teleost (the eel), two Kissr in a cypriniform (zebrafish), and only one Kissr in a more recent teleost (stickleback; Figure 3A).

Diversity and evolutionary history of Kiss in vertebrates

In contrast to the receptor proteins which present several conserved domains, the Kiss genes encode precursors which are highly variable among vertebrates, except for the short sequence of the mature decapeptide [Kp(10)]. This makes it difficult to obtain Kiss mRNA sequences by classical molecular strategies. Genomic database analyses thus represent the best approach to characterize the Kiss set for a given species. However, the small characteristic sequence of Kiss, encoding Kp(10), could be missing in genomic databases due to sequencing or assembly limitations.

All previously investigated osteichthyan species possessed the same number of Kiss and Kissr genes: one in eutherian mammals, two in prototherians, three in Xenopus, none in birds, and one or two in teleosts (Lee et al., 2009). In cyclostomes, two Kiss genes have been reported (Lee et al., 2009), while only one Kissr could be predicted until now (Pasquier et al., 2011).

Diversity and classification of Kiss

New advances in Kiss gene characterization

To further assess the Kiss diversity in vertebrates, we re-investigated the presence of these genes in the genome of the elephant shark, the coelacanth, the spotted gar, and the European eel, representative species from four groups of relevant phylogenetical positions. Most of the vertebrate Kiss genes are made of two exons except for some mammalian Kiss1, including human Kiss1, pig (Sus scrofa) Kiss1, and mouse Kiss1, that are made of three exons (Figure 1). However, the CDS of all the Kiss described so far are split on two exons (Figure 1). In fact the first of those two exons encodes the signal peptide while the final exon encodes mainly the mature peptides including the conserved Kp(10) (Figures 1 and 4; Tomikawa et al., 2010, 2012; Cartwright and Williams, 2012; Tena-Sempere et al., 2012). Considering that the Kiss gene sequences are highly variable among species except for the sequence encoding the Kp(10), we focused our prediction on the ORF containing this sequence. We performed TBLASTN in the four genomes, resulting in the identification of several ORF containing conserved sequences encoding for Kp(10).

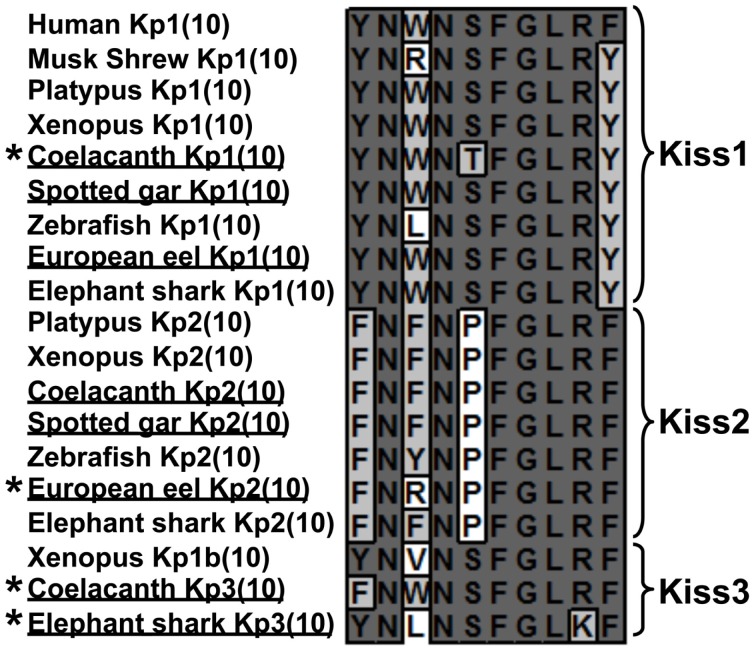

Figure 4.

Sequence alignment of vertebrate Kp(10). At each position, identical amino-acids are shaded in dark gray and similar amino-acids in light gray. Newly identified sequences are underlined and unique sequences are marked by an asterisk.

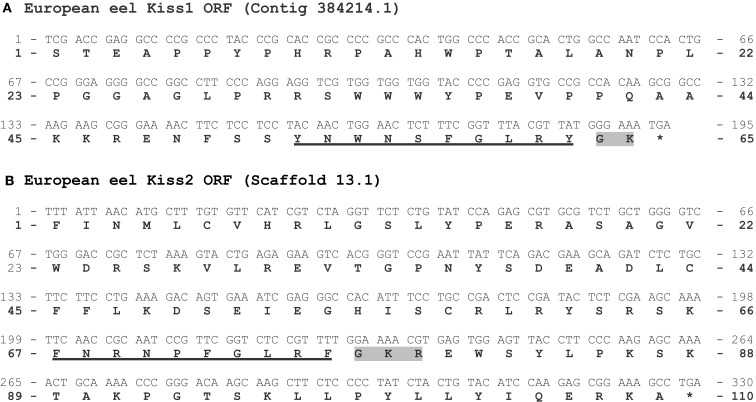

Two Kiss genes in the European eel genome. The two ORFs containing the sequences encoding Kp(10) are 296 and 327 bp long, respectively (Figure A1 in Appendix). Once translated, each of them leads to a peptidic sequence encompassing a putative Kp(10): YNWNSFGLRY [European eel Kp1(10)] and FNRNPFGLRF [European eel Kp2(10)], respectively (Figure 4). The C-terminal end of the Kp1(10) sequence is followed by a GK-Stop motif, while the Kp2(10) sequence is followed by a GKR motif (Figure A1 in Appendix). The sequences “X-G-Basic-Basic” or “X-G-Basic” are characteristic of the conserved proteolytic cleavage and alpha-amidation sites of neuropeptides (Eipper et al., 1992).

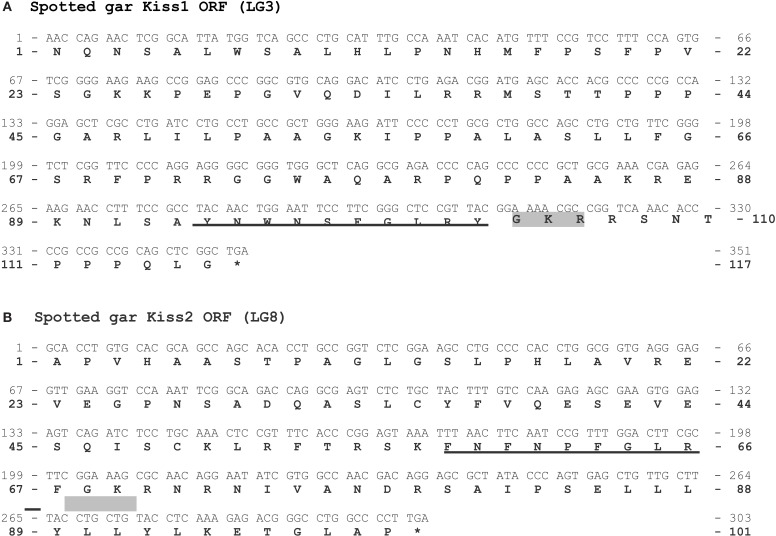

Two Kiss genes in the spotted gar genome. The two ORFs containing the sequences encoding Kp(10) are 348 and 300 bp long, respectively (Figure A2 in Appendix). Once translated, each of them leads to a peptidic sequence presenting a putative Kp(10): YNWNSFGLRY [spotted gar Kp1(10)] and FNFNPFGLRF [spotted gar Kp2(10)], respectively (Figure 4). The C-terminal ends of these two sequences are followed by a GKR motif (Figure A2 in Appendix).

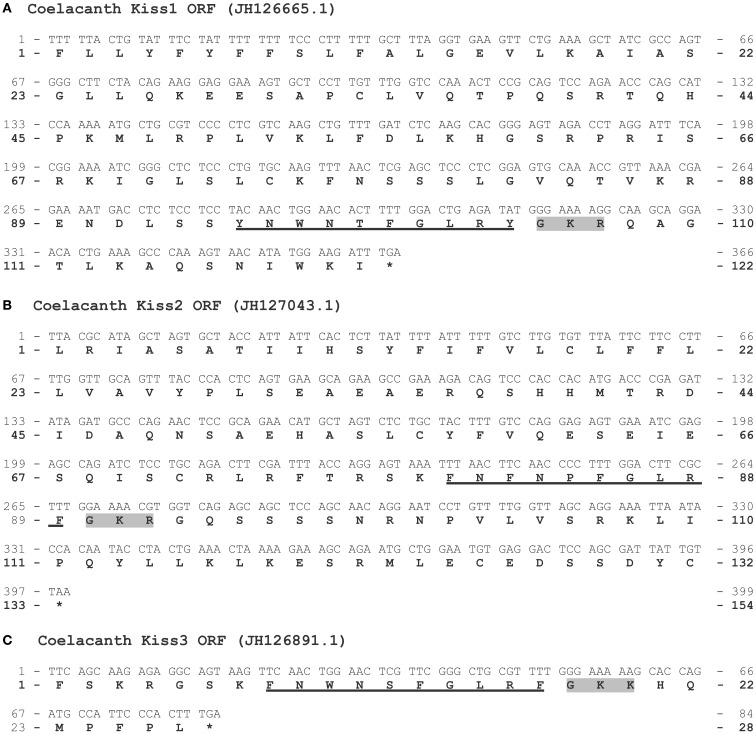

Three Kiss genes in the coelacanth genome. The three ORFs containing the sequences encoding Kp(10) are 363, 396, and 81 bp long, respectively (Figure A3 in Appendix). Once translated, each of them leads to a peptidic sequence encompassing a putative Kp(10): YNWNTFGLRY [coelacanth Kp1(10)], FNFNPFGLRF [coelacanth Kp2(10)], and FNWNSFGLRF [coelacanth Kp3(10)], respectively (Figure 4). The C-terminal ends of the Kp1(10) and the Kp2(10) sequences are followed by a GKR motif, while the Kp3(10) is followed by a GKK motif (Figure A3 in Appendix). Seven amino-acids up-stream the sequence of the Kp3(10), a stop codon appears (Figure A3 in Appendix) suggesting that coelacanth Kiss3 gene could have a different intro-exon structure compared to what has been described so far or it can suggest that this gene is no longer expressed.

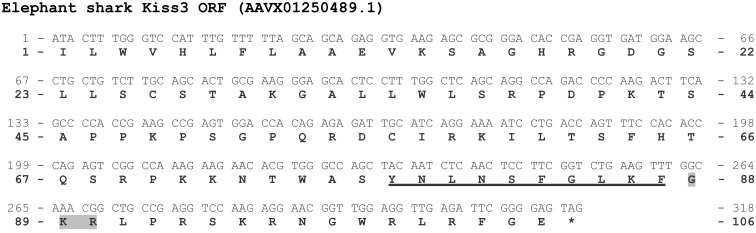

A third Kiss gene in the elephant shark genome. While two Kiss (Kiss1 and Kiss2) were previously identified in the elephant shark genome (Lee et al., 2009), we were able to localize a new ORF of 315 bp containing a third sequence encoding a Kp(10) (Figure A4 in Appendix). Once translated, it leads to a peptidic sequence encompassing a putative Kp(10): YNLNSFGLKF [elephant shark Kp3(10)] (Figure 4). The C-terminal end of this peptide is followed by a GKR motif (Figure A4 in Appendix).

Kiss sequence alignment and comparisons

The alignment of 56 kisspeptin precursors revealed a high variability of their amino-acid sequences except for the sequences corresponding to Kp(10) and its few surrounding amino-acids which, in contrast, are highly conserved (data not shown). Such a pattern, which is representative of many other neuropeptide precursors, provides poor phylogenetic information within alignment matrix. This lack of information makes the use of phylogenetic analysis inappropriate to establish homology relationships within this kind of peptide precursor family.

Novel Kp(10)

Among the new Kiss genes predicted in the present study, four of them encode novel Kp(10) (Figure 4). The singularity of the elephant shark Kp3(10) is the presence of a lysine (K) instead of an arginine (R) at the ninth position. The coelacanth Kp1(10) provides the first case of a threonine (T) at the fifth position. The coelacanth Kp3(10) is the only one to present both a phenylalanine (F) at the first position and a serine (S) at the fifth position. The European eel Kp2(10) presents at its third position an arginine (R), which possesses different physical and chemical properties from amino-acids commonly present at this position. Up to now, only the musk shrew (Suncus murinus) Kp1(10) presented an arginine at the third position and it was demonstrated that its kisspeptin system was involved in the reproductive function as in other mammals (Inoue et al., 2011). Since the impacted positions by the amino-acid substitutions have not been characterized as highly critical for Kp(10) functional properties (Gutiérrez-Pascual et al., 2009; Curtis et al., 2010), those novel Kp(10) may have conserved their functionality. Since Kp(10) is considered as the smallest required sequence to specifically bind to the receptor (Kotani et al., 2001), it could be of interest to test all those peptides in future pharmacological studies in order to assess their structure/function relationships.

Syntenic analysis and classification of Kiss genes

In order to classify the different Kiss paralogs, we performed a syntenic analysis of the Kiss neighboring genes. We considered the following vertebrate representatives: mammals (human), birds (chicken), squamates (lizard), amphibians (Xenopus), basal sarcopterygian (coelacanth), non-teleost actinopterygians (spotted gar), and teleosts (zebrafish, stickleback, and European eel). Our syntenic analysis demonstrated that the Kiss genes are localized in three different genomic regions.

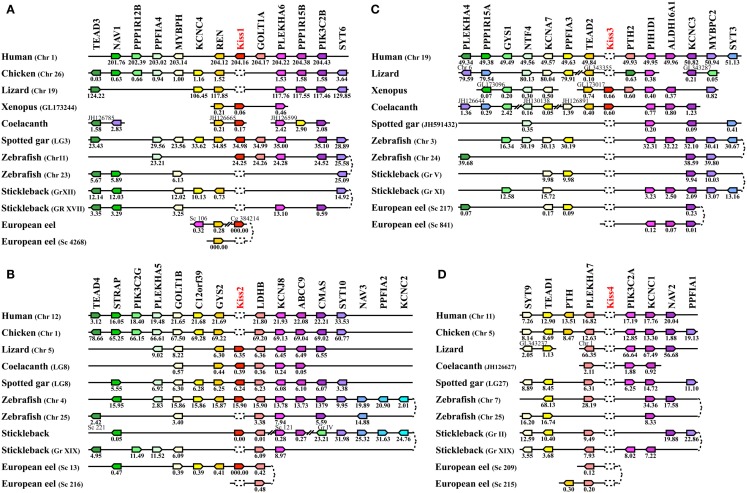

The human Kiss1, Xenopus Kiss1a, coelacanth Kiss1, spotted gar Kiss1, and zebrafish Kiss1 are positioned in genomic regions containing common loci, including TEAD3, NAV1, PPP1R12B, PPFIA4, MYBPH, KCNC4, REN, GOLT1A, PLEKHA6, PPP1R15B, PIK3C2B, and SYT6, thus exhibiting well conserved synteny (Figure 5A). This supports the orthology of these Kiss genes, all considered as Kiss1 genes. Syntenic analysis suggests that the stickleback, lizard, and chicken genomes do not contain any Kiss1 gene, although the above-mentioned neighboring genes are present in the corresponding genomic regions (Figure 5A). The peptidic sequence of eel Kiss1 presents many similarities to the other Kiss1, but the eel Kiss1 gene is located on too small scaffolds to contain any other gene, preventing from any syntenic analysis.

Figure 5.

Conserved genomic synteny of osteichthyan Kiss. Genomic synteny maps comparing the orthologs of Kiss1 (A), Kiss2 (B), Kiss3 (C), Kiss4 (D), and their neighboring genes. Analyses were performed on the genomes of human (Homo sapiens), platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus), lizard (Anolis carolinensis), chicken (Gallus gallus), Xenopus (Xenopus tropicalis), coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae), spotted gar (Lepisosteus oculatus), zebrafish (Danio rerio), stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus), and European eel (Anguilla anguilla). This map was established using the PhyloView of Genomicus v67.01 web site, manual annotation of the European eel genome using CLC DNA Workbench 6 software and the gene annotation of the coelacanth and spotted gar genomic databases. Kiss genes are named according to our proposed nomenclature (Kiss1 to Kiss4). The other genes are named after their human orthologs according to the Human Genome Naming Consortium (HGNC). Orthologs of each gene are shown in the same color. The direction of arrows indicates the gene orientation, with the position of the gene (in 10−6 base pairs) indicated below. The full gene names and detailed genomic locations are given in Table S1 in Supplementary Material. Chr, chromosome; LG, linkage group; Gr, group; Sc, scaffold; Cg, contig.

The lizard Kiss2, coelacanth Kiss2, spotted gar Kiss2, zebrafish Kiss2, stickleback Kiss2, and European eel Kiss2 genes are positioned in genomic regions containing common loci including STRAP, PLEKHA5, GOLT1B, C12orf39, GYS2, LDHB, KCNJ8, ABCC9, CMAS, SYT10, NAV3, PPFIA2, and KCNC2, thus exhibiting well conserved synteny (Figure 5B). This supports the orthology of these Kiss genes, all considered as Kiss2 genes. Syntenic analysis suggests that human and chicken genomes do not contain any Kiss2 gene, although the above-mentioned neighboring genes are present in the corresponding genomic region (Figure 5B).

The coelacanth Kiss3 and the Xenopus Kiss1b genes are positioned in genomic regions containing common loci, including TEAD2, PIH1D1, and ALDH16A1, thus exhibiting well conserved synteny (Figure 5C). This supports the orthology of these two Kiss genes, both considered here as Kiss3 genes. Syntenic analysis suggests that human, lizard, spotted gar, and teleost genomes do not contain any Kiss3 gene, although the above-mentioned neighboring genes are present in the corresponding genomic regions (Figure 5C). Syntenic analysis also suggests that the whole considered region is absent from the chicken genome.

Evolutionary history of Kiss

Origin of Kiss diversity via 1R and 2R

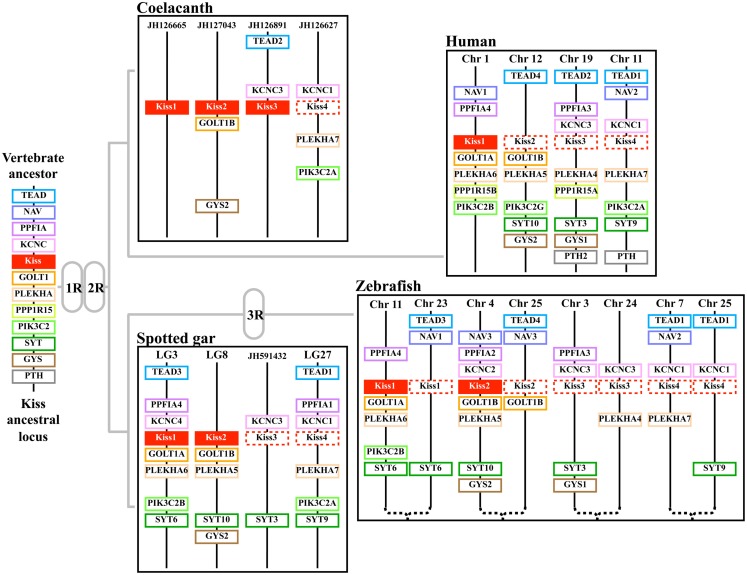

The syntenic analysis also allowed us to investigate the origin of the multiple Kiss genes found in vertebrates. The three conserved genomic regions, presenting Kiss genes, also comprise other paralogs from 11 gene families: TEAD (4 paralogs), NAV (3 paralogs), PPFIA (4 paralogs), KCNC (4 paralogs), GOLT1 (2 paralogs), PLEKHA (4 paralogs), PPP1R15 (2 paralogs), PIK3C2 (3 paralogs), SYT (4 paralogs), GYS (2 paralogs), and PTH (2 paralogs) (Figures 5A–C). The members of those families are present among the three Kiss syntenic regions and they also delineate a fourth conserved region (Figure 5D), which does not present any Kiss gene in the osteichthyan representative species studied so far. The four conserved regions delineated by the 11 gene families can be considered as paralogous (tetra-paralogon).

Considering the reconstruction of the ancestral vertebrate chromosomes, their linkage to the tetra-paralogons in the human genome (Nakatani et al., 2007) and our localization of the four Kiss syntenic regions in the human genome (on Chromosomes 1, 11, 12, and 19), we can hypothesize that the Kiss tetra-paralogons resulted from the duplications of one single genomic region localized on the proto-chromosome-D of the vertebrate ancestor. Therefore, we can infer that the current three Kiss genes may have resulted from a single ancestral gene duplicated through 1R and 2R that occurred in early steps of vertebrate evolution (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Proposed origin of osteichthyan Kiss tetra-paralogons. The paralogous genes of each of the 11 identified families delineate four paralogons in spotted gar, coelacanth, and human genomes and a duplicated tetra-paralogon in the zebrafish genome. This suggests a common origin of the three Kiss before the two whole genome duplication rounds (1R and 2R) which occurred in the early vertebrate history. This also suggests no impact of the teleost-specific 3R on Kiss number in current teleost species. Chr, chromosome; LG, linkage group.

A subsequent history of Kiss losses

Multiple loss events in sarcopterygians and actinopterygians. The 1R and 2R events should have resulted in four different Kiss genes in vertebrates. Since the fourth Kiss gene (referred to as Kiss4 in this study) has not been observed in any species studied so far, we can hypothesize an early loss of this gene after the 2R. As only a chondrichthyan, the elephant shark, and two sarcopterygians, the coelacanth and Xenopus, still present three Kiss genes, whereas all other species possess less than three Kiss, we can hypothesize multiple additional events of Kiss losses in vertebrates (Figure 3B).

Among the sarcopterygian lineage, in tetrapods, Kiss3 would have been lost in amniotes. Further alternative losses may have occurred in this lineage, with only Kiss1 remaining in eutherian mammals and only Kiss2 in squamates (lizard). Finally, additional losses would have led to the complete absence of Kiss in birds (Figure 3B). Among the actinopterygian lineage, an early loss of Kiss3 would have occurred since it is lacking in the actinopterygian species investigated so far (Figure 3B).

No impact of the teleost-specific 3R on Kiss number in current species. In the actinopterygian lineage, the teleost-specific 3R and the presence of two Kiss in a non-teleost actinopterygian, the spotted gar, implied the potential existence of at least four Kiss genes in the early teleost history. However, our study showed that so far the largest number of Kiss exhibited by current teleosts, including the eel, is two. Furthermore, each teleost Kiss is orthologous to a different tetrapod Kiss, indicating that no teleost-specific Kiss exists. Synteny analysis revealed that each of the four Kiss genomic regions present in the spotted gar is duplicated in teleosts in agreement with the 3R event but that duplicated Kiss genes are lacking (Figures 5 and 6). This suggests an early loss of duplicated Kiss genes suppressing the impact of the 3R on the number of Kiss in teleosts (Figure 3B). Additional deletion may have led to the presence of only Kiss2 in gasterosteiforms (the stickleback; Figure 3B). Kiss evolutionary history was punctuated by numerous loss events through vertebrate radiation (Figure 3B).

Comparison of the evolutionary histories of Kiss and Kissr in vertebrates

These new data concerning Kiss and Kissr diversities enabled us to improve their respective classifications and evolutionary histories. A remaining challenge was to elucidate whether Kiss and Kissr families have experienced parallel histories during vertebrate radiation. The comparative study of the current status of both families in vertebrates allows a better understanding of the whole kisspeptin system.

Features in agreement with parallel histories

Origin of the Kiss and Kissr multiplicity via 1R and 2R

Our syntenic studies suggest that the vertebrate Kiss and Kissr families both resulted from the successive duplications of a single ancestral gene through the 1R and 2R (Figure 3). Thus, Kiss and Kissr experienced, in parallel, the two first genome duplication rounds resulting in four copies of each gene in the early steps of the vertebrate evolutionary history (Figure 3). While Kissr gene homologs were characterized in non-vertebrate species (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus, GenBank accession numbers: XP_793873.1 and XP_796286.1; Saccoglossus kowalevskii, GenBank accession numbers: NP_001161573.1 and NP_001161574.1), tracing back the presence of an ancestral Kissr in early deuterostomes, Kiss genes have not yet been discovered in non-vertebrate species.

Subsequent history of gene losses

Both Kiss and Kissr families were composed of four genes in the early steps of the vertebrate history. However, most of the current vertebrate species investigated so far present less than four copies of Kiss and Kissr genes. The current numbers of both Kiss and Kissr genes suggest that both families underwent numerous independent loss events across vertebrate history (Figure 3).

No impact of the teleost-specific 3R

The teleost lineage, which has experienced a third whole genome duplication round (3R), could have been expected to possess up to eight Kiss and Kissr genes. However, the analyses of the Kiss and Kissr within teleost genomes revealed a maximum of three Kissr and two Kiss genes and did not reveal any 3R-specific copies of Kiss or Kissr genes. This suggests that the teleost-specific 3R did not impact the current number of Kiss or Kissr genes, reflecting massive losses of the 3R-copies of both Kiss and Kissr genes in early teleosts (Figure 3).

Features in opposition to parallel histories: independent loss events

Un-matching number of Kiss and Kissr in some species

In the current gnathostomes, we observed a maximum of four Kissr but only three Kiss paralogs. This difference suggests that this lineage inherited the four Kissr copies resulting from the 1R and 2R, whereas the fourth Kiss may have been lost before or at an early stage of the gnathostome emergence (Figure 3). This situation was observed in an early sarcopterygian, the coelacanth, while an even larger difference in Kissr (four) and Kiss (two) numbers was found in the spotted gar, reflecting an additional independent loss of Kiss in the actinopterygian lineage. An un-matching number of Kissr (three) and Kiss (two) was also observed in an early teleost, the European eel, while additional losses may have led to equal numbers of Kissr and Kiss in more recent teleosts (two or one according to the species). These variations in Kissr/Kiss numbers reflect different timing of Kiss and Kissr loss events. Those hypotheses suggest that Kiss losses occurred independently among the different gnathostome lineages and also independently from the Kissr losses.

Various Kiss/Kissr combinations across vertebrates

The hypothesis of independent Kiss and Kissr evolutionary histories is also strengthened by the comparison of the gene sets present in species with even matching numbers of Kiss and Kissr. For example, lizard, and stickleback both present the Kiss2 gene, whereas they possess different Kissr, i.e., Kissr-4 in the lizard and Kissr-2 in the stickleback (Figure 3). The same observation can be done comparing the kisspeptin systems of platypus and zebrafish, which both present the Kiss1 and Kiss2 genes, whereas their sets of receptors are completely different, i.e., Kissr-1 and Kissr-4 in platypus versus Kissr-2 and Kissr-3 in zebrafish (Figure 3). These observations strongly suggest a large variety of Kiss and Kissr combinations, resulting from independent loss events. These data shed new lights on the evolution of the kisspeptin system in vertebrates and challenge the former hypothesis of a conservation of Kiss/Kissr couples across vertebrate evolution. This diversity among vertebrates opens new research avenues for comparative physiology and endocrinology of kisspeptin system.

What could have favored the independent evolutions of Kiss and Kissr?

A few in vitro studies using recombinant receptors have showed cross-reactivities between various kisspeptins and kisspeptin receptors (Biran et al., 2008;Lee et al., 2009; Li et al., 2009). For instance, Lee et al. (2009) tested the specificity of recombinant human GPR54 (Kissr-1 according to our nomenclature), zebrafish GPR54-1, and -2 (Kissr-3 and Kissr-2 according to our nomenclature), and Xenopus GPR54-1a, -1b, and -2 (Kissr-1, Kissr-4, and Kissr-2 according to our nomenclature) toward various kisspeptins. They showed that human, zebrafish, and Xenopus kisspeptins were able to activate all the receptors with differential intra and inter-specific ligand selectivity. Such cross-reactivity could have promoted the independence of the Kiss and Kissr evolutionary histories. This could explain the situation of species presenting un-matching numbers of Kiss and Kissr genes, as well as the high variability of Kiss/Kissr gene combinations across vertebrate species. Another study, using goldfish recombinant GPR54a and GPR54b (Kissr-3 and Kissr-2 according to our nomenclature), revealed that the ligand potency strikingly differed depending on the responsive element used in the reporter gene construction (Li et al., 2009). These data showed the difficulty to define specific Kiss/Kissr couples based only on pharmacological properties.

In the case of the presence of multiple Kiss/Kissr genes in a given species, anatomical relationships between projections of Kiss neurons and target cells expressing Kissr may provide further cues for determining Kiss/Kissr functional couples. Thus, in zebrafish which possess two Kiss genes and two Kissr genes, in situ hybridization and immunocytochemical studies localized the Kiss1 neurons in different nuclei from Kiss2 neurons (Servili et al., 2011). Moreover, Kiss1 neurons are projecting to Kiss1r (Kissr-3 according to our nomenclature) expressing cells, while Kiss2 neurons are projecting to Kiss2r (Kissr-2 according to our nomenclature) expressing cells (Servili et al., 2011). This reveals anatomically separated kisspeptin systems and distinct specific Kiss/Kissr functional couples in zebrafish (Servili et al., 2011). In striped bass, another teleost possessing two Kiss genes and two Kissr genes, in situ hybridization and laser capture microscopy coupled to quantitative PCR showed, in contrast, that Kiss1 and Kiss2 were co-expressed in neurons of the hypothalamus, indicating promiscuous Kiss synthesis sites (Zmora et al., 2012). However, the two Kissr of the striped bass were expressed in different brain cells, indicating that the kisspeptin systems are not fully redundant (Zmora et al., 2012). All these data underline the importance of investigating the gene diversity, the anatomical organization and the functional properties of the kisspeptin system in various species, regarding the potential high variability of this system among vertebrates.

Conclusion

Kisspeptin system is known to play a role in many physiological processes such as antimetastasis, energy metabolism homeostasis, pregnancy, and puberty onset. Even though this system has been widely studied in the last few years, its diversity and evolutionary history remained unclear. Thanks to the newly published genomes of osteichthyans of key phylogenetical positions, we were able to provide new data on the diversity of Kiss and Kissr genes, to clarify the classification of these genes and to bring new insights on the evolutionary history of these gene families. Four Kissr and four Kiss genes may have arisen via the 1R and 2R in early vertebrates. This would have been followed by multiple independent Kiss and Kissr gene loss events in the sarcopterygian and actinopterygian lineages. In particular, due to massive Kiss and Kissr gene losses, no impact of the teleost-specific 3R can be recorded on the number of Kissr or Kiss paralogs in current teleost species. The comparison of both Kiss and Kissr gene status, in the current vertebrates, supports both parallel and independent evolutionary histories of the Kiss and Kissr families across vertebrate radiation. It also underlines a large diversity of Kiss/Kissr possible combinations that needs to be taken into account in future comparative studies.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at http://www.frontiersin.org/Neuroendocrine_Science/10.3389/fendo.2012.00173/abstract

Names, references, and locations of the genes used in the Kiss synteny analysis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. B. Quérat (CNRS, Paris, France) for his helpful advices and discussions concerning phylogeny and synteny. We also thank all the different consortiums at the initiative of sequencing, assembly, annotation, and publication of genomes, in particular the consortiums of the European eel genome, the spotted gar genome, the coelacanth genome, the elephant shark genome, and the sea lamprey genome. Our thanks also include the authors of the Ensembl genome browser web site and all web sites providing free access to their genomic databases. We thank the authors of the Genomicus web site providing a very useful and friendly tool for synteny analysis. Jérémy Pasquier is a recipient of a Ph.D. fellowship from the Ministry of Research and Education. This work was supported by grants from the National Research Agency, PUBERTEEL N ANR-08-BLAN-0173 to Karine Rousseau and Sylvie Dufour, and from the European Community, Seventh Framework Program, PRO-EEL N No. 245257 to Anne-Gaëlle Lafont and Sylvie Dufour.

Appendix

Figure A1.

Prediction of two Kiss ORFs from the European eel genome. Nucleotide and deduced amino-acid sequences of the ORF encoding the European eel Kp1(10) (A) and Kp2(10) (B). Nucleotides (top) are numbered from 5′ to 3′. The amino-acid residues (bottom) are numbered beginning with the first amino-acid residue encoded by the ORF. The asterisk (*) indicates the stop codon. The predicted Kp(10) are underlined. The amino-acids of the C-terminal α-amidation and cleavage site are shaded in gray.

Figure A2.

Prediction of two Kiss ORFs from the spotted gar genome. Nucleotide and deduced amino-acid sequences of the ORF encoding the spotted gar Kp1(10) (A) and Kp2(10) (B). Nucleotides (top) are numbered from 5′ to 3′. The amino-acid residues (bottom) are numbered beginning with the first amino-acid residue encoded by the ORF. The asterisk (*) indicates the stop codon. The predicted Kp(10) are underlined. The amino-acids of the C-terminal α-amidation and cleavage site are shaded in gray.

Figure A3.

Prediction of three Kiss ORFs from the coelacanth genome. Nucleotide and deduced amino-acid sequences of the ORF encoding the coelacanth Kp1(10) (A), Kp2(10) (B), and Kp3(10) (C). Nucleotides (top) are numbered from 5′ to 3′. The amino-acid residues (bottom) are numbered beginning with the first amino-acid residue encoded by the ORF. The asterisk (*) indicates the stop codon. The predicted Kp(10) are underlined. The amino-acids of the C-terminal α-amidation and cleavage site are shaded in gray.

Figure A4.

Prediction of a third Kiss ORF from the elephant shark genome. Nucleotide and deduced amino-acid sequences of the ORF encoding the elephant shark Kp3(10). Nucleotides (top) are numbered from 5′ to 3′. The amino-acid residues (bottom) are numbered beginning with the first amino-acid residue encoded by the ORF. The asterisk (*) indicates the stop codon. The predicted Kp(10) is underlined. The amino-acids of the C-terminal α-amidation and cleavage site are shaded in gray.

Footnotes

References

- Amores A., Catchen J., Ferrara A., Fontenot Q., Postlethwait J. H. (2011). Genome evolution and meiotic maps by massively parallel DNA sequencing: spotted gar, an outgroup for the teleost genome duplication. Genetics 188, 799–808 10.1534/genetics.111.127324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amores A., Force A., Yan Y. L., Joly L., Amemiya C., Fritz A., et al. (1998). Zebrafish hox clusters and vertebrate genome evolution. Science 282, 1711–1714 10.1126/science.282.5394.1711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biran J., Ben-Dor S., Levavi-Sivan B. (2008). Molecular identification and functional characterization of the kisspeptin/kisspeptin receptor system in lower vertebrates. Biol. Reprod. 79, 776–786 10.1095/biolreprod.107.066266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright J. E., Williams P. J. (2012). Altered placental expression of kisspeptin and its receptor in pre-eclampsia. J. Endocrinol. 214, 79–85 10.1530/JOE-12-0091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis A. E., Cooke J. H., Baxter J. E., Parkinson J. R., Bataveljic A., Ghatei M. A., et al. (2010). A kisspeptin-10 analog with greater in vivo bioactivity than kisspeptin-10. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 298, E296–E303 10.1152/ajpendo.00426.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Roux N., Genin E., Carel J. C., Matsuda F., Chaussain J. L., Milgrom E. (2003). Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism due to loss of function of the KiSS1-derived peptide receptor GPR54. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 10972–10976 10.1073/pnas.1834399100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehal P., Boore J. L. (2005). Two rounds of whole genome duplication in the ancestral vertebrate. PLoS Biol. 3:e314. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eipper B. A., Stoffers D. A., Mains R. E. (1992). The biosynthesis of neuropeptides: peptide alpha-amidation. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 15, 57–85 10.1146/annurev.ne.15.030192.000421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felip A., Zanuy S., Pineda R., Pinilla L., Carrillo M., Tena-Sempere M., et al. (2009). Evidence for two distinct KiSS genes in non-placental vertebrates that encode kisspeptins with different gonadotropin-releasing activities in fish and mammals. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 312, 61–71 10.1016/j.mce.2008.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funes S., Hedrick J. A., Vassileva G., Markowitz L., Abbondanzo S., Golovko A., et al. (2003). The KiSS-1 receptor GPR54 is essential for the development of the murine reproductive system. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 312, 1357–1363 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Pascual E., Leprince J., Martínez-Fuentes A. J., Ségalas-Milazzo I., Pineda R., Roa J., et al. (2009). In vivo and in vitro structure-activity relationships and structural conformation of Kisspeptin-10-related peptides. Mol. Pharmacol. 76, 58–67 10.1124/mol.108.053751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkel C. V., Burgerhout E., de Wijze D. L., Dirks R. P., Minegishi Y., Jansen H. J., et al. (2012). Primitive duplicate Hox clusters in the European eel’s genome. PLoS ONE 7:e32231. 10.1371/journal.pone.0032231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hultqvist G., Ocampo Daza D., Larhammar D., Kilimann M. W. (2012). Evolution of the vertebrate paralemmin gene family: ancient origin of gene duplicates suggests distinct functions. PLoS ONE 7:e41850. 10.1371/journal.pone.0041850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue N., Sasagawa K., Ikai K., Sasaki Y., Tomikawa J., Oishi S., et al. (2011). Kisspeptin neurons mediate reflex ovulation in the musk shrew (Suncus murinus). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 17527–17532 10.1073/pnas.1113035108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara M., Naruse K., Sasaki S., Nakatani Y., Qu W., Ahsan B., et al. (2007). The medaka draft genome and insights into vertebrate genome evolution. Nature 447, 714–719 10.1038/nature05846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. K., Cho E. B., Moon M. J., Park S., Hwang J. I., Do Rego J. L., et al. (2012). Molecular coevolution of neuropeptides gonadotropin-releasing hormone and kisspeptin with their cognate G protein-coupled receptors. Front. Neurosci. 6:3. 10.3389/fnins.2012.00003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitahashi T., Ogawa S., Parhar I. S. (2009). Cloning and expression of kiss2 in the zebrafish and medaka. Endocrinology 150, 821–831 10.1210/en.2008-0940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotani M., Detheux M., Vandenbogaerde A., Communi D., Vanderwinden J. M., Le Poul E., et al. (2001). The metastasis suppressor gene KiSS-1 encodes kisspeptins, the natural ligands of the orphan G protein-coupled receptor GPR54. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 34631–34636 10.1074/jbc.M104847200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H., Miele M. E., Hicks D. J., Phillips K. K., Trent J. M., Weissman B. E., et al. (1996). KiSS-1, a novel human malignant melanoma metastasis-suppressor gene. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 88, 1731–1737 10.1093/jnci/88.23.1731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. R., Tsunekawa K., Moon M. J., Um H. N., Hwang J. I., Osugi T., et al. (2009). Molecular evolution of multiple forms of kisspeptins and GPR54 receptors in vertebrates. Endocrinology 150, 2837–2846 10.1210/en.2008-1679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Zhang Y., Liu Y., Huang X., Huang W., Lu D., et al. (2009). Structural and functional multiplicity of the kisspeptin/GPR54 system in goldfish (Carassius auratus). J. Endocrinol. 201, 407–418 10.1677/JOE-09-0016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinilla L., Aguilar E., Dieguez C., Millar R. P., Tena-Sempere M. (2012). Kisspeptins and reproduction: physiological roles and regulatory mechanisms. Physiol. Rev. 92, 1235–1316 10.1152/physrev.00037.2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seminara S. B., Messager S., Chatzidaki E. E., Thresher R. R., Acierno J. S., Shagoury J. K., et al. (2003). The GPR54 gene as a regulator of puberty. N. Engl. J. Med. 349, 1614–1627 10.1056/NEJMoa035322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servili A., Le Page Y., Leprince J., Caraty A., Escobar S., Parhar I. S., et al. (2011). Organization of two independent kisspeptin systems derived from evolutionary-ancient kiss genes in the brain of zebrafish. Endocrinology 152, 1527–1540 10.1210/en.2010-0948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tena-Sempere M., Felip A., Gomez A., Zanuy S., Carrillo M. (2012). Comparative insights of the kisspeptin/kisspeptin receptor system: lessons from non-mammalian vertebrates. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 175, 234–243 10.1016/j.ygcen.2011.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomikawa J., Homma T., Tajima S., Shibata T., Inamoto Y., Takase K., et al. (2010). Molecular characterization and estrogen regulation of hypothalamic KISS1 gene in the pig. Biol. Reprod. 82, 313–319 10.1095/biolreprod.109.079863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomikawa J., Uenoyama Y., Ozawa M., Fukanuma T., Takase K., Goto T., et al. (2012). Epigenetic regulation of Kiss1 gene expression mediating estrogen-positive feedback action in the mouse brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, E1294–E1301 10.1073/pnas.1114245109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Peer Y., Maere S., Meyer A. (2010). 2R or not 2R is not the question anymore. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 166. 10.1038/nrg2579-c1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh B., Kirkness E. F., Loh Y. H., Halpern A. L., Lee A. P., Johnson J., et al. (2007). Survey sequencing and comparative analysis of the elephant shark (Callorhinchus milii) genome. PLoS Biol. 5:e101. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zmora N., Stubblefield J., Zulperi Z., Biran J., Levavi-Sivan B., Munoz-Cueto J. A., et al. (2012). Differential and gonad stage-dependent roles of Kisspeptin1 and Kisspeptin2 in reproduction in the modern teleosts, morone species. Biol. Reprod. 86:177. 10.1095/biolreprod.111.097667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A., Van de Peer Y. (2005). From 2R to 3R: evidence for a fish-specific genome duplication (FSGD). Bioessays 27, 937–945 10.1002/bies.20293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muffato M., Louis A., Poisnel C. E., Roest Crollius H. (2010). Genomicus: a database and a browser to study gene synteny in modern and ancestral genomes. Bioinformatics 26, 1119–1121 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir A. I., Chamberlain L., Elshourbagy N. A., Michalovich D., Moore D. J., Calamari A., et al. (2001). AXOR12, a novel human G protein-coupled receptor, activated by the peptide KiSS-1. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 28969–28975 10.1074/jbc.M102743200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatani Y., Takeda H., Kohara Y., Morishita S. (2007). Reconstruction of the vertebrate ancestral genome reveals dynamic genome reorganization in early vertebrates. Genome Res. 17, 1254–1265 10.1101/gr.6316407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquier J., Lafont A.-G., Jeng S.-R., Morini M., Dirks R., van den Thillart G., et al. (2012). Multiple kisspeptin receptors in early osteichthyans provide new insights into the evolution of this receptor family. PLoS ONE 7:e48931. 10.1371/journal.pone.0048931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquier J., Lafont A. G., Leprince J., Vaudry H., Rousseau K., Dufour S. (2011). First evidence for a direct inhibitory effect of kisspeptins on LH expression in the eel, Anguilla anguilla. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 173, 216–225 10.1016/j.ygcen.2011.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Names, references, and locations of the genes used in the Kiss synteny analysis.