Abstract

Objective. To change the structure of a required pharmacy management course to make it more interactive and engaging for students.

Design. The course is a required component of undergraduate curriculum and is completed over 2 semesters during the students’ third year. Changes included requiring students to lead classroom discussions and complete a business plan in groups.

Assessment. A questionnaire centering on methods of delivery, course content, and outcomes was distributed in 2 academic years, with 74.7% of students responding. Even though the redesigned course required more time, there was strong support for the course among students because they realized the content contributed to their learning.

Conclusion. A major course redesign is a big commitment by faculty members, but if done through consultations with former and current students, it can be rewarding for all involved. Students overwhelmingly embraced the changes to the course as they realized the restructuring and the resulting increase in workload were necessary to raise the relevance of the course to their future professional practice.

Keywords: pharmacy management, curriculum, engagement, active learning, self-directed learning

INTRODUCTION

Pharmacy educators need to continually update their curricula in order to keep in line with changes in pharmacy and to stay relevant. One important area of pharmacy practice that has been overlooked involves administrative and managerial aspects.1 Given the lack of attention to this area, there may be deficiencies in pharmacy education resulting in educators not fully preparing students for the realities of practice.

Pharmacy leaders, current and future, require clinical experience and expertise if they and other pharmacists are to realize their full potential. Moving the profession forward and allowing for that expertise to be applied in a meaningful way, however, requires not only clinical knowledge but also exposure to and experience with management.2 With a shift to more clinically oriented services, pharmacists are being encouraged to develop, promote, and implement new, innovative professional services.3 High-performing pharmacy leaders are relatively rare4 and are likely to become even more scarce if more is not done to prepare future pharmacists to be leaders and advocates. Therefore, there is a need to graduate future pharmacy leaders who are not only clinical experts but also competent in managing patient care and pharmacy personnel.5

Although changes in pharmacy curriculum have been made in response to the need to further integrate clinical experiences in entry-to-practice degree programs, much of the management curriculum involves primarily classroom teaching and learning. Teaching management to pharmacy students is all the more difficult if the students do not see the practical application of what they learn. Additionally, managing others may appear to be an easy or common-sense task to those who have never managed people;6 therefore, simply “telling” students about management and managing may not be the best method to ensure they learn and retain what they need to know to be successful in practice. There is also a call for the professional curriculum to focus on 3 functional roles for pharmacists (patient-centered care, population-based care, and pharmacy systems management) and foster the development of 5 abilities (professionalism, self-directed learning, leadership and advocacy, interprofessional collaboration, and cultural competency).7 This manuscript focuses on 2 of the abilities: self-directed learning and leadership and advocacy. As professionals, pharmacists are required to continually enhance their knowledge base through professional development/education activities. Understanding and developing knowledge requires taking responsibility for learning, a primary component of which is critical thinking.8 As such, the importance of self-directed learning within the profession has received considerable attention.7,9,10

This manuscript describes the redesign of a mandatory undergraduate course on management in pharmacy and the assessment of the redesign by students who were surveyed regarding the perceived benefits, and shortfalls. The purpose of redesigning the course and obtaining student feedback was to instill an understanding of the importance of management in all practice sites using a pragmatic approach, while also creating a more engaging environment by placing more responsibility for learning and teaching on the students.

DESIGN

The course was redesigned based on the recognition that a majority of students who had taken the course were not engaged in the material and/or did not recognize the relevance of management in pharmacy practice. Another motive for the redesign was that numerous former graduates, once in practice, realized the role management plays in practice and were contacting instructors regarding managerial issues, which often had been covered in the course. In an effort to make students appreciate and grasp the role of pharmacy management before entering practice, the course was deemed in need of redesign to make it more engaging and, if possible, to help students retain the concepts presented.

Prior to the redesign, the course consisted primarily of classroom lectures with some interactive/applied tutorials, and assessment consisted of in-class and final examinations and a small-group project. Hands-on application of management situations has been shown to increase student learning.11 Additionally, gaining the perspective of former students who are now practicing pharmacists was recognized as the key to understanding how to make the course more useful and relevant for the students. Former students who had completed the course were e-mailed and asked what they liked, disliked, and would like to see changed about the course. This feedback was used as a starting point for the course redesign. The ultimate goal of the course redesign was to increase student learning and retention.11

Expected Outcomes and Learning Objectives

At the time of the study, there were 10 colleges and schools of pharmacy in Canada. While the process is underway in many schools to convert to a PharmD entry-to-practice curriculum, similar to what is standard in the United States, most programs prescribe to a model that includes 1 year of prepharmacy plus 4 years of undergraduate pharmacy education. 12 Regardless of how the curriculum is designed at a given school, all pharmacy students must complete various structured practical experiences, including community and hospital pharmacy practice experiences.

Educational Environment

At the University of Saskatchewan, students complete a minimum of 1 year of prepharmacy courses at the university level and then apply to enter the program, ultimately leading to a bachelor of science in pharmacy (BSP) degree; however, many students have completed more than 1 year of university courses before being accepted into the program and some have already obtained a university degree. Entrance to the program is competitive, with approximately 16% of applicants on average successfully receiving a place in the incoming class of 90 students.

In the first 2 years of the BSP program, students complete many of the foundational courses that are built upon in the third and fourth years of the program.13 Courses in the first 2 years focus on physiology, pharmaceutics, pathology, pharmacology, research methods, and an introduction to pharmacy and the healthcare system. Third- and fourth-year courses focus on biotechnology, management, pharmacotherapeutics, evidence-based practice, advanced patient care, and policy. While practical experience is required throughout the program, the final term for fourth-year students consists of three 5-week practice experiences: community practice, hospital practice, and a specialty practice experience (eg, HIV/AIDS, academic detailing, international pharmacy practice [eg, Ghana], and psychiatry.)

The Management in Pharmacy course described in this manuscript is a mandatory, full academic year (2 terms, September to April) course offered in the third year of the BSP program. All students (approximately 90) attend two 80-minute lectures weekly. There are also 2 different tutorial times (half the class in each) during which more difficult concepts, such as financial and managerial accounting, are further discussed. There are 2 PhD instructors for the course, with each being responsible for the lecture material in 1 of the 2 terms. The course is labor intensive for 2 instructors primarily because of how the content is delivered and the way in which students are assessed.

Course Focus

The redesign of this course took an almost exclusively andragogical14 learner-focused approach that was also focused on the self-directed learner.15 This objective was based on the premise that the students will soon be practicing pharmacists who will need to be self-directed in the required continuing education inherent in being a practicing member of the profession. To foster an environment with an andragogical, self-directed-learner focus, the content of the course required students to take ownership of their learning and move away from the pedagogy, wherein instructor needs tend to take precedence over those of students. While it is easier on the instructor to conduct classroom lectures and use examinations as the sole assessment method, this approach does not truly foster learning.

The course previously had a primarily lecture-based, pedagogical focus. Lectures tended to be primarily 1-way exchanges of information, wherein learning was not necessarily occurring. Examinations involved memorization and information dumps by students with little retention. This is a common occurrence when students are told what they have to learn to be successful in the course. There were a few small-group assignments but nothing too engaging, as the course was previously taught by only 1 instructor. As would be expected, more engaging exercises also require greater preparation and assessment/grading time.

With the redesign of the course, instructors experienced some discomfort as they had to relinquish some control in the classroom if the course was to truly become self-directed and learner-focused. As is typical, change requires drawing upon past experiences in order to move forward in a meaningful way, accepting that one does not know everything and seeking the guidance and experience of others in order to make an informed decision on how to proceed.

One of the first steps the author took toward redesigning the course and learning from others was to enroll in the Participant-Centered Learning Seminars, The Art and Craft of Leadership Discussion at the Harvard School of Business, in Boston, Massachusetts.16 To address the need for health- and specifically pharmacy-focused managerial cases, the author attended the Case Writing Workshop at the Ivey School of Business, University of Western Ontario in London, Ontario, in April 2012.17

Course Content

The broad concepts of the course did not change with the redesign, but the method of teaching and learning changed dramatically. One of the first goals was to identify a textbook that students could use as a resource to supplement information contained in lectures and the accompanying materials. The result was a required text, Pharmacy Management: Essentials for All Practice Settings by Desselle and Zgarrick,18 which was to be used strictly as a supplemental learning resource.

A 9-page course syllabus was compiled that served as an instruction manual on what students could expect during the course, addressing issues ranging from required materials, academic honesty, and course objectives and methods, to how students would be evaluated in the course. It also included a list of required readings (peer-reviewed articles) and a detailed course schedule. While quizzes and examinations were still part of the redesigned course, the assessment of the course focused on 2 new methods introduced in the redesign: a group business plan and a personal portfolio.

Business Plan. The business plan became a focal point of the course. Completing a business plan as a member of a group has been shown to increase pharmacy students’ business management skills for implementing new clinical/professional services.19 Further, involving pharmacy managers in the process has been shown to enhance pharmacy students’ business plan development skills.20

Innovative changes have led to many great ideas and pilot projects that have resulted in improved clinical outcomes; however, all too often, these projects are not sustainable and/or end when pilot funding runs out. A common theme that emerged in most of these changes was that there was no long-term strategy to make the innovation sustainable, and, in particular, no business plan. Whether in a for-profit commercial practice environment (eg, community pharmacy) or a nonprofit practice environment (eg, hospital pharmacy or primary care practice), financial feasibility of practice change is essential. In a manner similar to the rationale followed when approving a drug for inclusion on a formulary, one must show a clinical as well as a financial benefit to successfully implement practice change.

For the business plan, students formed self-selected groups of 5 or 6. In these groups, they were required to create a business plan with the goal of implementing a new service into an existing community pharmacy practice. This exercise focused on community pharmacy practice because of the access students had to practitioners and resources while creating their plans. The guidelines for the business plan were intentionally broad to stimulate creativity in a manner not generally seen in traditional science-based professional programs. As a result, students struggled to find their focus at the beginning; but by the end of the process, they understood and appreciated the purpose, which was to develop something innovative from conception to completion.

Business Plan Competition. Another change that aligned with the requirement to develop a business plan was to establish a business plan competition. Rather than merely having the students present their plans to their classmates, the competition was used as an opportunity to show to pharmacy stakeholders outside of the college what pharmacy students are capable of creating.

External pharmacy stakeholders (advocacy, regulatory, industry and publishing) were brought in to judge the business plan competition and also to sponsor the competition. Having these stakeholders judge the business presentations provided a source of motivation for students. The competition was held at the end of the course before final examinations began and took an entire morning to complete (approximately 5 hours). The competition was held during regular class time, with instructors from 2 other courses trading class times so it could be conducted on a single day.

For the competition, students were allowed 10 minutes to present their business plans to the judging panel. The competition portion of the business plan, while mandatory, was not graded. Instead, students competed for cash and other prizes, with the winners having their names permanently engraved on a plaque displayed in the college and having an opportunity to present their plan to future colleagues, and potential employers at the annual Pharmacists’ Association of Saskatchewan conference.

The first competition (2010-2011 academic year) was an outstanding success, and by the second competition in the following academic year, students fully embraced the opportunity. Some of the student business plans have been implemented into practice, and many students have used their experience to distinguish themselves from others when competing for job opportunities. The students, the college, and sponsors have all received recognition for their efforts in the competition.21-23 Title sponsorship has been obtained on a long-term basis,24 and overall, the competition has proven to be a rewarding experience for all involved.

Participation Log. Another activity introduced to the redesigned course was that each student was to maintain a participation log throughout the course and, at the end of each term, submit the log with a memo, referred to as a participation report. This activity was initiated based on the realization that not speaking up in class and expressing opinions does not necessarily indicate that a student is not actively engaged in the material. For this exercise, students made at least 1 log entry per week in which they focused on the lecture topic (not necessarily the content of the lecture) and expressed their thoughts about it, how it was presented in class, how it applied to their current life and would apply in the future, as well as whether their group discussed the topic. When submitting the participation report at the end of each term, students included a summative account of their experiences, which was similar to what they will experience in performance evaluations in their career when they assess their own professional growth and development. Although this requirement, which resulted in approximately 90 reports, many of which were 30 or more pages long, involved a great deal of time to produce and evaluate, the benefit to both students and instructors was considered significant enough to justify the additional effort.

Current Events

Another change was that the course lectures were redesigned to increase student engagement. Within the new course format, each lecture began with a discussion of current events in pharmacy to increase the relevance of the course to the students and to highlight the role management plays in successful professional practice. Many students stated that the current events section of each class was the first time they had been exposed to what was actually going on in pharmacy practice.

While these discussions included current events from pharmacy and health care within Canada, they also showcased what was being done in other countries, with particular focus on the United States, Australia, and the United Kingdom. By having the current events discussion at the beginning of each lecture, the lecture topic often became part of the discussion, which helped students understand why the management course was important and how what they learned would influence their careers.

Student-Led Discussions. As part of the redesign, students formally led some of the class discussions. Having pharmacy students teach their peers improved student confidence, knowledge, and skills in that particular area.25 For this aspect of the course, a reading list of current academic, peer-reviewed articles related to pharmacy practice and management was created, and each student group (same group members that completed the business plan together) led a class discussion on their chosen article. This activity provided students an opportunity to get to know the members of their group and how they work together.

When leading class discussions, student groups were expected to simply talk about their article without using technical media such as PowerPoint (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Most followed this method, although a minority supplemented their discussion with audiovisual or electronic media. Each group was given a maximum of 20 minutes during select class times to lead a discussion about their article. Students were also encouraged to bring in other relevant articles and develop questions to engage their peers in the discussion. This simple approach allowed a dialogue to occur as the group leading the discussion directly engaged the audience by asking questions. At times, the groups would have to deal with the awkward silence that can occur when an audience is not fully engaged in the discussion; therefore, the group had to prepare follow-up questions to engage the audience.

The activity also provided students with an opportunity to present their views, critically appraise an article, and gain confidence in speaking in front of a large group. It was also unlike formal presentations, for which grading/assessment occurs, in that students did not have to stress over the format of the presentation/discussion and were able to engage the audience by directly asking questions. This format differed from formal presentations in which the delivery of information is 1-way, followed by questions from the audience.

Relevance. All lectures ended with a slide or 2 called “Application to Business Plan,” which addressed the relevance of the lecture and topic to the business plan. This aspect of the redesigned course provided another opportunity to illustrate to students the relevance of the course subject matter.

An average week in the course consisted of two 80-minute class sessions. In the first session of the week, which typically introduced a new topic, there was some interaction between instructor and students but it was primarily a lecture format. The second session usually had a maximum of 2 student groups leading class discussions on their articles, followed by coverage of the remainder of the topic. At times, when a more engaging discussion did not allow for a topic to be completely covered, the students were asked to review the notes themselves and ask the instructor questions or the topic was wrapped up in a subsequent session. After the first revised course was offered, “catch-up” class sessions were routinely scheduled because of the likelihood that discussions of some topics would not be completed in the allotted time.

EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT

At the end of the first term in the 2010-2011 and 2011-2012 academic years, a questionnaire was distributed to students in the Management in Pharmacy course (copy of the questionnaire can be obtained from the author on request). Because the questionnaire was distributed/administered only once per academic year, students had to be in class on the day the questionnaire was distributed in order to respond. The survey instrument centered on the methods of delivering the course content as well as perceived outcomes. In an attempt to obtain responses that were as truthful as possible, students were asked not to provide any information that would reveal their identity.

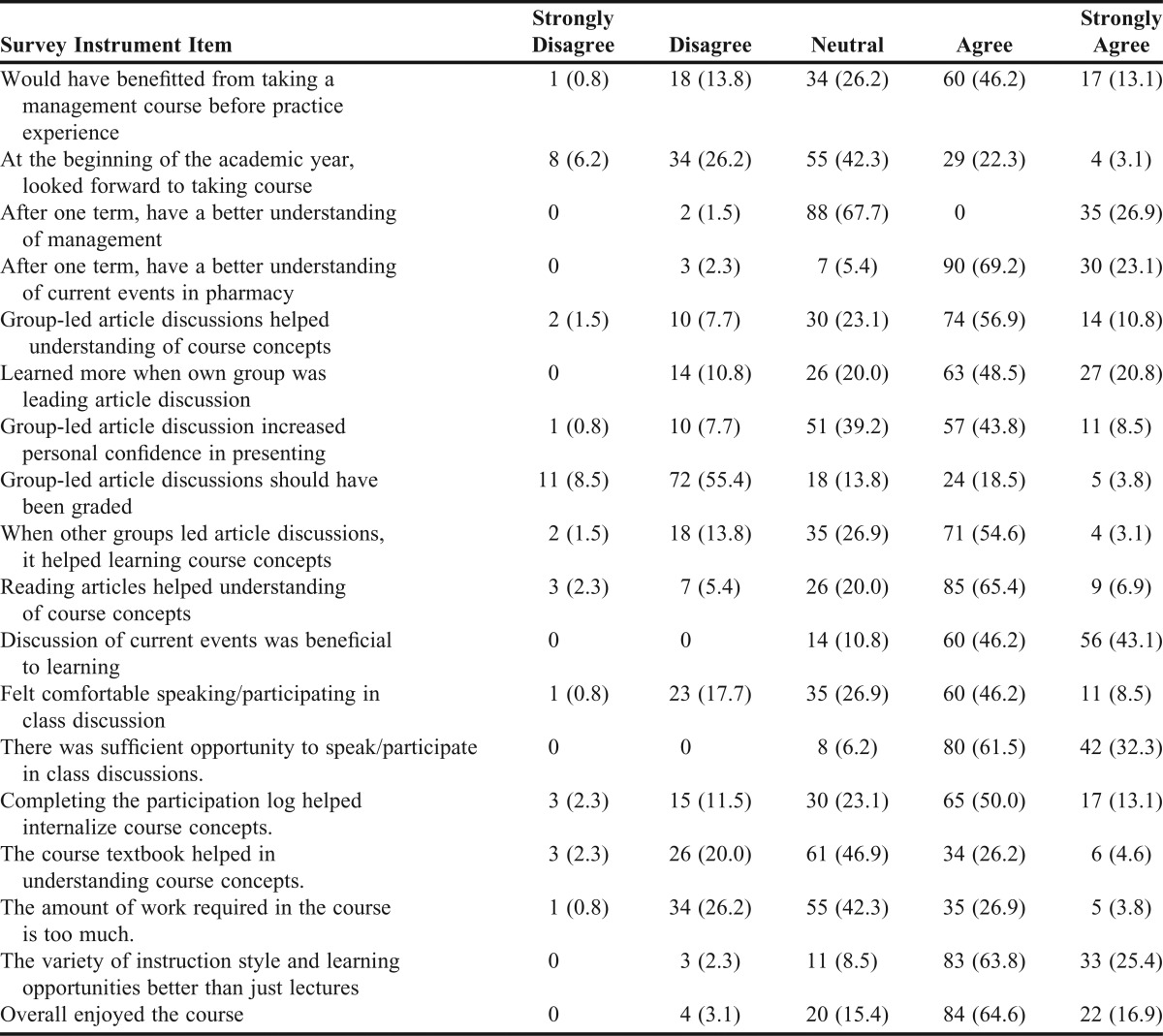

Once data were collected, descriptive statistics and 1-way ANOVA tests were conducted. For results showing significant differences (p<0.05), cross-tabulation statistics were run to explore the differences between groups. Reliability analyses were also conducted, resulting in unsatisfactory loadings (data not displayed), with standardized item-factor loading weights less than 0.70 (alpha >0.70).26-28 Of the 174 students registered in the course over both academic years, 130 (74.7%) completed and returned the questionnaire (63 of 86 for 2010-2011; 67 of 88 for 2011-2012). A large majority (86.9%) had never taken any management course before enrolling in the Management in Pharmacy course. Almost three-fourths (73.1%) of respondents were female, a percentage consistent with course and college enrollment. Frequencies are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Pharmacy Students’ Opinions Regarding a Redesigned Course in Pharmacy Management, No. (%)

Several significant differences emerged. If respondents had not taken a management course before, they were less likely to report that reading the peer-reviewed articles helped their understanding of the course concepts (p=0.036) and that there was sufficient opportunity to speak/participate in class (p=0.035). With respect to the amount of work required in the course, if respondents reported that the course did not require too much work, they were more likely to agree that the variety in teaching methods was better than having strictly lectures (ie, classroom teaching) (p=0.012), and they were more likely to report having enjoyed the course (p=0.010).

The 2 main variables explored were whether the respondent looked forward to taking the course prior to its inception and whether they enjoyed the course. Respondents who looked forward to taking the course were more likely to: have a better understanding of management (p=0.002); find that the group-led article discussions helped their understanding of course concepts (p=0.011); feel that article discussions led by other groups helped their understanding of the material (p=0.037); find that reading the actual articles helped them to understand course concepts (p=0.004); state that there was sufficient opportunity to participate during class (p=0.002); and report that the variety in teaching methods was better than lectures alone (p=0.034).

Respondents reporting enjoying the course were more likely to: agree that they would have benefited from taking a management course before their community pharmacy 4-week practicum (p=0.0001); report a better understanding of management than before taking the course (p=0.0001); have a better understanding of current events affecting pharmacy practice (p=0.0001); find that group-led article discussions helped their understanding of course concepts (p=0.0001); state that group-led article discussions helped increase their confidence in presenting to an audience (p=0.002); feel that group-led article discussions should not be graded (p=0.021); report that article discussions led by other groups helped them to understand course concepts (p=0.001); find that reading the articles themselves helped them understand the course concepts (p=0.0001); feel comfortable speaking during the class (p=0.0001); report sufficient opportunity to participate during class (p = 0.001); report that the participation log helped them internalize course concepts (p=0.0001); state that the variety of teaching methods was better than just lectures (p=0.0001); and have taken the course in the 2010-2011 academic year as opposed to the 2011-2012 academic year.

DISCUSSION

Not all pharmacists will be managers/owners nor do many want to be. However, the reality is that all pharmacists will be required to manage people as well as processes. To assure stakeholders of the value of pharmacist interventions for the healthcare system as a whole, a sustainable financial and managerial plan must be developed. Many barriers and obstacles must be overcome for innovation to take root. If a pharmacist can understand and speak to what administrators, managers, and financiers require to support that innovation, it is much easier to persuade them that an investment up front will result in better clinical and financial outcomes. Although the authors recognized that having students create business plans rather than assessing student learning with only examinations would be more work for both students and instructors, the change was implemented in the belief that, over the long term, it would be beneficial for all involved.

As with any change, a steep learning curve and a few bumps along the way are bound to occur, and this course redesign was no exception. While these obstacles were anticipated to some extent, the main challenge was the increased demand on time for both students and instructors. Although the redesign was quite demanding from the initial concept/vision to the delivery and assessment, the challenges associated with the redesign should not be a deterrent to anyone wanting to modify a course in order to provide students with a richer learning experience and ideally increase their retention of concepts beyond the final examination. In particular, the participation reports take quite a long time to assess, especially when students are fully engaged in the subject matter and write extensively. Given the time and effort students invested in producing the reports, it was only fair that they be provided with adequate feedback from the instructor rather than just assigned a grade. Further, the amount of learning and feedback the instructors took away from reading over the reports was invaluable and was, in and of itself, adequate justification for such an exercise. Almost two-thirds (63.1%) of respondents reported that completing the participation log/report helped them internalize the course concepts.

For group-led article discussions, the instructor provided general feedback to each group afterward but did not assign a formal grade. Less than one-fourth (22.3%) of respondents felt that the group-led article discussions should have been graded. This finding shows a heightened level of maturity, given that the students seemed to recognize that not everything that matters as they prepare to become pharmacists and are socialized into the profession is associated with a grade. The majority (52.3%) of respondents also reported that leading a class discussion increased their personal confidence in presenting to a group.

At the time of this report, 31 student groups have led article discussions. Each group has been unique with respect to the way its members led the discussion, and not a single student has been critical about not receiving a grade for leading the discussion. Students reported that they liked not receiving a grade because they felt less pressure and were able to step out of their comfort zone and try presentation techniques they would have been afraid to attempt with a graded exercise. This finding is especially relevant, given that management is an entirely new concept for the large majority of students.

Incorporating a discussion about current events in pharmacy practice was 1 aspect of the course redesign. The vast majority (92.3%) of respondents reported having a better understanding of what was going on in the profession after completing the course than before. Presenting current events at the beginning of each class session not only helped students relate course concepts to “the real world” but also showed them the realities of practice and that the utopian image of the practice environment sometimes presented to them may not be realistic. The discussions of current events in class was also found to be beneficial to learning for the majority (89.3%) of respondents.

Respondents strongly agreed (89.2%) that the variety of instruction style and learning opportunities was better than classroom lectures alone. This finding may be the result of students realizing that management is a subject best learned by doing and being engaged in the content of the course rather than passively receiving information. When assessing the course, most students (81.5%) reported enjoying the course, a positive finding considering that most students who took the previous iteration of the course disliked it.

SUMMARY

A pharmacy management course was redesigned to actively engage students and to be more relevant and applicable to the “real world.” Students who participated in the study were accommodating and appreciative of the steps taken to improve the course and did not mind doing extra work they perceived as beneficial. Redesigning a pharmacy management course to be more relevant and interactive for students, however, places additional demands on instructors’ time and requires an openness to feedback and criticism.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author acknowledges Dr. Roy T. Dobson for giving his “blessing” to our plans to redesign the Management in Pharmacy course at the University of Saskatchewan and his willingness to accept the changes and transform his teaching. The authors also thank the BSP Class of 2012 for agreeing to be “guinea pigs” for this experiment in curriculum redesign.

REFERENCES

- 1.Senft SL, Thompson C, Blumenschein K. Dual degree programs at the University of Kentucky College of Pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(1):Article 12. doi: 10.5688/aj720112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolawole O, Pedersen C, Schneider P, Smeenk D. Perspectives on the attributes and characteristics of pharmacy executives. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2002;59(3):278–281. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/59.3.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hermansen-Kobulnicky C, Moss C. Pharmacy student entrepreneurial orientation: a measure to identify potential pharmacist entrepreneurs. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(5):Article 113. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Filerman G, Komaridis K. The pharmacy leadership gap: diagnosis and prescription. J Health Admin Educ. 2007;24(2):117–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Latif D. Using emotional intelligence in the planning and implementation of a management skills course. Pharm Educ. 2004;4(2):81–89. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holdford D. Managing oneself: an essential skill for managing others. J Am Pharms Assoc. 2009;49(3):436–445. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2009.07066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jungnickel P, Kelley K, Hammer D, Haines S, Marlowe K. Addressing competencies for the future in the professional curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(8):Article 156. doi: 10.5688/aj7308156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garrison D. Critical thinking and self-directed learning in adult education: an analysis of responsibility and control issues. Adult Educ Q. 1992;42(3):136–148. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown D, Hinton A. Self-directed professional development: the pursuit of affective learning. Am J Pharm Educ. 2001;65(Fall):240–246. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huynh D, Haines S, Plaza C, et al. The impact of advanced pharmacy practice experiences on students' readiness for self-directed learning. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(4):Article 65. doi: 10.5688/aj730465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calomo J. Teaching management in a community pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(2):Article 41. doi: 10.5688/aj700241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Austin Z, Ensom M. Education of pharmacists in Canada. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(6):Article 128. doi: 10.5688/aj7206128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Undergraduate programs: bachelor of science in pharmacy. College of Pharmacy and Nutrition, Unviersity of Saskatchewan. 2012 http://www.usask.ca/pharmacy-nutrition/undergradprograms/bscpharmacy.php. Accessed September 14. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knowles M. The Modern Practice of Adult Education. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Cambridge Adult Education; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knowles M. Self-Directed Learning: A Guide for Learners and Teachers. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Cambridge Adult Education; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 16.HBSP. Participant-centered learning. 2012 http://hbsp.harvard.edu/product/participant-centered-learning. Accessed September 14. [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Ivey Case Writing Workshop. The Richard Ivey School of Business, The Univesity of Western Ontario. 2012 http://www.ivey.uwo.ca/workshops/ivey_workshops.html. Accessed September 14. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desselle S, Zgarrick D. Pharmacy Management: Essentials for All Practice Settings. Toronto, ON: The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hicks C, Siganga W, Shah B. Enhancing pharmacy student business management skills by collaborating with pharmacy managers to implement pharmaceutical care services. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(4):Article 94. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moultry A. A mass merchandiser’s role in enhancing pharmacy students’ business plan development skills for medication therapy management services. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(7):Article 133. doi: 10.5688/ajpe757133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perepelkin J, Killeen R. 2011 University of Saskatchewan pharmacy student business plan competition. Can Pharm J. 2011;144(4):158–159. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perepelkin J. Preparing students for the real world: U of Saskatchewan launches business plan competition. Pharm Bus. 2012;March:12 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perepelkin J. University of Saskatchewan mounts another successful business plan competition. Can Pharm J. 2012;145(3):107. doi: 10.3821/145.3.cpj107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perepelkin J. University of Saskatchewan pharmacy student business plan competition. 2012 doi: 10.1177/1715163513494598. http://www.usask.ca/pharmacy-nutrition/businessplan/index.php. Accessed September 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shrader S, Kavanagh K, Thompson A. A diabetes self-management education class taught by pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(1):Article 13. doi: 10.5688/ajpe76113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santos J. Cronbach's Alpha: a tool for assessing the reliability of scales. J Extension. 1999;37(2) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nunnally J, Bernstein I. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed. Toronto, ON: McGraw-Hill, Inc.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bollen KA. Structural Equations With Latent Variables. Toronto, ON: John Wiley & Sons; 1989. [Google Scholar]