Abstract

In the fifty years since Békésy was awarded the Nobel Prize, cochlear physiology has blossomed. Many topics that are now current are things Békésy could not have imagined. In this review we start by describing progress in understanding the origin of cochlear gross potentials, particularly the cochlear microphonic, an area in which Békésy had extensive experience. We then review progress in areas of cochlear physiology that were mostly unknown to Békésy, including: (1) stereocilia mechano-electrical transduction, force production, and response amplification, (2) outer hair cell (OHC) somatic motility and its molecular basis in prestin, (3) cochlear amplification and related micromechanics, including the evidence that prestin is the main motor for cochlear amplification, (4) the influence of the tectorial membrane, (5) cochlear micromechanics and the mechanical drives to inner hair cell stereocilia, (6) otoacoustic emissions, and (7) olivocochlear efferents and their influence on cochlear physiology. We then return to a subject that Békésy knew well: cochlear fluids and standing currents, as well as our present understanding of energy dependence on the lateral wall of the cochlea. Finally, we touch on cochlear pathologies including noise damage and aging, with an emphasis on where the field might go in the future.

Keywords: cochlear microphonic, hair cells, cochlear amplifier, endocochlear potential, prestin, olivocochlear, stereocilia

1. Introduction

In celebration of the 50-year jubilee for Georg von Békésy’s Nobel Prize we review progress in cochlear physiology with a special view to those areas in which Békésy made important contributions. In order to make this paper understandable to non-experts in the field, we focus on major trends and controversies. This necessitates that important details are omitted. Because it is impossible to reference all of the papers that have been important in producing our current understanding of cochlear physiology, we reference a mix of original papers from the discoverers of phenomena, and more recent papers that provide a variety of relevant references. Although many interesting things have been learned about non-mammalian hearing, we concentrate on mammalian cochlear physiology.

2. The Origin of Cochlear Gross Potentials

As Tonndorf (1986) reported, Békésy was employed at the Telephone System Laboratory of the Post Office in Budapest, the best place in Hungary for his experimental endeavors since scientific equipment was available there. Because of the rather primitive understanding of the inner ear at that time, Békésy found it difficult to answer questions from his engineering colleagues about auditory physiology. Fortunately, a supportive environment allowed Békésy to begin the experimental studies that would become his life work.

Békésy’s early electrophysiological experiments were designed to pinpoint the origin of the cochlear microphonic (CM). CM was thought by its discovers, Wever and Bray (1930), to be from the auditory nerve. However, at the time that Békésy performed his experiments, it was known that the CM was not coming from the auditory nerve (Adrian, 1931), and that it disappeared with organ of Corti removal, thereby implicating hair cells in its generation. In spite of the fact that some considered the CM to be an epiphenomenon (Davis et al., 1949), Békésy wondered what role this gross ac cochlear potential might have in peripheral signal coding. His early observations indicated that the vibratory patterns of the basilar membrane (BM) were complex such that the CM represented an integration of voltages produced along the partition, which complicated their interpretation. Even when Békésy used a sharp needle to set a small section of the partition into motion, there were phase cancellations in CM. A differential electrode technique was introduced by Tasaki et al. (1952) to at least partially deal with these complications.

In order to determine the place of origin of the CM, Békésy described three tissues that an electrode encountered in its traverse of the cochlear partition after entering from scala tympani. The first included the BM, which did not produce potentials and, therefore, acted as a simple electrical resistance. The second included supporting cells like Hensen and Claudius cells that do not generate a first-order CM but appeared to function like batteries with negative resting potentials. Finally, the third group included active cells responsible for the large potentials seen in the scala media (SM). With improved recording technologies Békésy would probably have been able to record from individual hair cells in addition to his observations of the endocochlear potential (EP) and injury potentials as the recording electrode passed through the cochlear partition. The first actual in vivo intracellular hair cell recordings were made by Russell and Sellick (1978). These inner hair cell (IHC) recordings from the base of the cochlea were later supplemented by inner and outer hair cell (OHC) measurements from the apex by Dallos and colleagues (1982).

Békésy’s experiments using a vibrating electrode demonstrated that the CM was proportional to BM displacement not velocity. These experimental results foreshadowed the later intracellular work showing that OHCs respond to BM displacement, IHCs to velocity at least at low frequencies. Current thinking suggests that when recorded at the round window, the CM is dominated by receptor currents generated primarily by basal OHCs (Patuzzi et al., 1989) responding to inputs below their characteristic frequency (CF). In other words, the CM recorded from distant electrodes is a passive phenomenon, something that Békésy understood in the 1950s.

3. Stereocilia Mechano-Electrical Transduction (MET) and Amplification

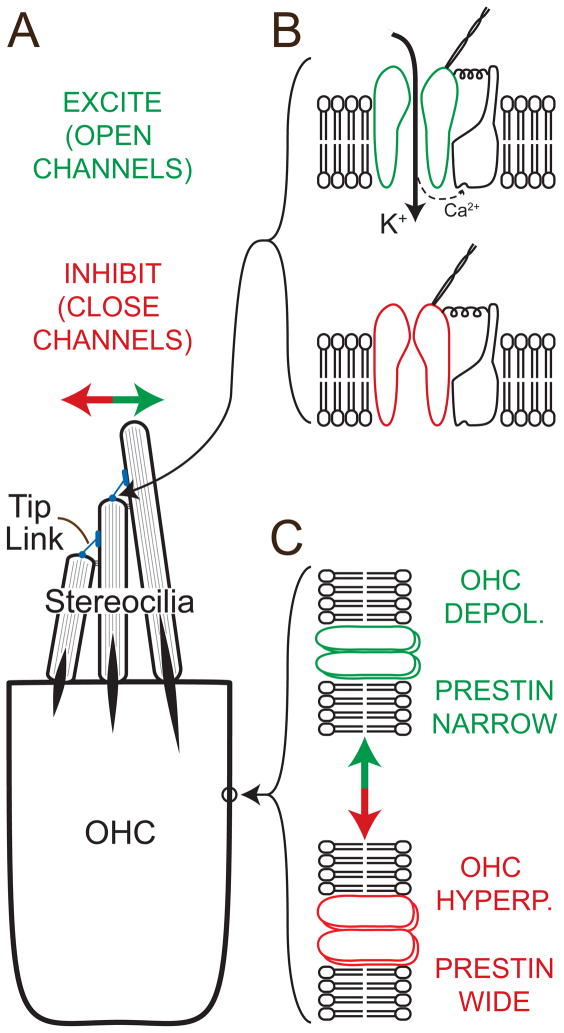

Shortly after Békésy received the Nobel Prize in 1961, the first key steps were made in understanding hair-cell mechano-electrical transduction (MET). Experiments in the lateral line demonstrated that displacing stereocilia toward the tallest row caused current flow into a hair cell (Flock, 1965). The CM is a gross reflection of these receptor currents, i.e., hair-cell MET underlies its generation. Over the past decades much more has been learned about MET in stereocilia, mostly from vestibular and non-mammalian hair cells (Gillespie and Müller, 2009). MET in stereocilia is mediated by connections between adjacent rows of stereocilia called “tip links” (Fig. 1A). Displacing the stereocilia in the excitatory direction pulls on the tip links, thereby increasing open probability, and current flow through the channels (Fig. 1B). From the point of view of a single channel, the action is somewhat like a spring pulling on a door that opens when the tension is sufficient; however, there is not a fixed tension at which the channel opens. Instead the channel opening is probabilistic with open probability increasing as the tension becomes greater. An individual channel rapidly flips between closed and open states, and the tip-link tension controls the proportion of time that the channel is open. The mechanical coupling between the tip-link tension and channel opening is likely to be bidirectional. If something causes a channel to close, it pulls on the tip link and moves the stereocilia (i.e., if the door is closed it stretches the spring). This is important as it represents a mechanism whereby physiological responses of hair cells can cause mechanical movements.

Fig. 1.

A schematic of OHC mechano-electric transduction (MET) and prestin conformational change. A: Tip links connect the MET apparatus on short stereocilia (expanded in B) with the next taller stereocilia. Circled is a prestin-containing patch of lateral membrane (expanded in C). Deflection toward the tallest stereocilia pulls on the tip links and increases the probability that the channels will open. Deflection toward the smallest stereocilia does the opposite. B: Cartoon of the MET channel protein in the open (green) and closed (red) state. When the channel is open, potassium (K+) and calcium (Ca2+) ions flow into the OHC. Calcium ions bind to a nearby site, which reduces the open probability, perhaps by relaxing a spring-like element. The binding site is shown here in a second protein molecule, even though the actual configuration remains unknown. The receptor current carried by potassium ions depolarizes the OHC. C-top: OHC depolarization (DEPOL) causes prestin molecules to become narrower resulting in OHC somatic contraction. C-bottom: OHC hyperpolarization (HYPERP) causes prestin molecules to become wider resulting in OHC somatic elongation.

In the cochlea, the tip links are maintained in a state of tension, so that in the resting state the channel-open probability is not zero. This results in there being a resting current flowing through the hair cells. The resting current allows both increases and decreases in tip-link tension to change current flow through the stereocilia, i.e., hair-cell current can be modulated in both directions by sound. The resting operating point of the channel-open probability varies across hair cell types and from base to apex. At the base of the cochlea, ~50% of the MET channels in OHCs appear to be open, which is much larger than the ~11% estimated for OHCs at the apex (Dallos et al., 1982) and for IHCs at all cochlear locations (Russell and Kössl, 1991).

When deflections of the stereocilia cause more MET channels to be open than in the resting state, electrochemical gradients (see below) cause more current to flow into the stereocilia with several consequences. First, the increased MET current flows out of the hair cell through its basolateral surface thereby changing the transmembrane voltage. Although most of the receptor current is carried by potassium (K+) some is carried by calcium (Ca2+), and the calcium produces two kinds of adaptation (Martin et al., 2000). If stereocilia are pushed and held in the excitatory (channel open) condition for many milliseconds, then the calcium flowing into the stereocilia causes the tip-link’s attachment to the taller stereocilia to move down the stereocilia thereby reducing tension in the tip link (Holt and Corey, 2000). This decreases the current flow while the stereocilia remain deflected (i.e., it causes adaptation) with the net effect of returning the transducer operating point to near its resting condition. Calcium entering into the stereocilia also produces another, much faster, adaptation that is thought to be due to calcium ions binding onto the MET channel protein or to a nearby site (Fig. 1B). When calcium binds to this site, it changes the properties of the MET channel such that the channel-closed probability increases. The resulting channel closing pulls on the tip link and exerts a force on the stereocilia. These two calcium-activated adaptations can produce spontaneous oscillations of stereocilia and amplification of small, sound-induced stereocilia motions (Martin et al., 2003). Such calcium-activated stereocilia motion appears to be the mechanism by which responses to low-level sounds are amplified in many non-mammalian vertebrates. Since MET channels in mammalian cochlear stereocilia appear to work by the same mechanisms as in other stereocilia, it has been suggested that stereocilia motility contributes to mammalian cochlear amplification. Fast stereocilia adaptation has been found in mammalian OHCs at frequencies up to a few kHz, but technical limitations have prevented a determination of whether there is fast stereocilia adaptation at higher frequencies (Kennedy et al., 2003).

4. Outer Hair Cell Motility and Prestin

Perhaps the most important reason that Békésy’s traveling wave is not the last word on the topic is OHC somatic motility. Brownell et al. (1985) and Zenner et al. (1985) showed that OHCs change their length as a function of membrane polarization; hyperpolarization causes OHC elongation and depolarization causes OHC contraction. Experimental evidence suggests that a bidirectional relationship between the electrical and mechanical events underlies OHC motility. This direct coupling of OHC voltage and local mechanical properties exhibits a piezoelectric coefficient that is four orders of magnitude greater than the best known piezoelectric materials (Iwasa, 2001). Because many investigators have worked to characterize the biophysics of OHC electromotility (reviewed by Ashmore, 2008), we provide only a few highlights. For example, somatic motility is fast (Ashmore, 1987; Frank et al., 1999) and it can be induced by cilia displacement (Evans and Dallos, 1993). Because motility depends on local membrane events (Kalinec et al., 1992), speculation suggested that the OHC’s lateral membrane might contain sensors that changed their conformation when exposed to a change in membrane potential. This possibility motivated several groups to search for the motor protein. The result was the discovery of prestin (Zheng et al., 2000) and the demonstration that molecular shape changes (Fig. 1C) were dependent on intracellular anions, especially chloride (Oliver et al., 2001; Santos-Sacchi et al., 2006). The concerted action of thousands of motor-protein molecules in the lateral membrane results in length change and the generation of force. Recent atomic force microscopy indicates that the ~11 nm particle clusters in the OHC’s plasma membrane (Murakoshi and Wada, 2009) are associated with prestin tetramers. Because prestin is unique to mammals, it may provide the main motor power for mammalian cochlear amplification.

5. Cochlear Amplification and Cochlear Micromechanics

Békésy’s ground-breaking measurements demonstrated the existence of traveling waves but were done on passive cochleae from cadavers. Over the last few decades we have learned that if Békésy had done measurements on live cochleae in good condition, BM motion to low-level tones would have been much larger. A variety of experiments provide strong evidence that active processes in OHCs increase BM movements at low sound levels by what is now called “cochlear amplification”. The consequences of this for the traveling wave are dealt with in the cochlear mechanics paper in this issue (Olson et al., 2012). Here we consider the question of what cellular and micromechanical processes produce cochlear amplification.

Early work after Békésy’s era showed two major things: that OHCs are needed for sensitive hearing and that as sound level is increased, the growth of BM motion is nonlinear (Rhode 1971; Dallos and Harris, 1978). Since Békésy, techniques for measuring BM motion have slowly improved so that we now have measurements of BM motion in the cochlear base of animals with near-normal thresholds. A key aid in the development of these techniques was the tone-pip audiogram, i.e., measurements across frequency of the sound levels needed to produce a criterion auditory-nerve compound action potential (CAP). Using CAPs, the quality of a preparation could be assessed throughout the surgery. Measurements in sensitive cochleae (assessed by CAPs) have shown that as the level of a stimulus tone is increased, BM motion at the best-frequency cochlear place grows with compressive nonlinearity while motion an octave, or more, away grows linearly (Rhode, 1971; reviewed in Robles and Ruggero, 2001). The increase in BM sensitivity at low sound levels, i.e., “cochlear amplification”, was shown to depend on the endocochlear potential and intact, well-functioning OHCs. In the apical half of the cochlea, there are no BM measurements of comparable quality, and existing measurements suggest that cochlear mechanics is different in the apex compared to the base (Cooper and Rhode, 1995).

Since the discovery of BM mechanical nonlinearity and its dependence on active, energy consuming processes, a major question has been whether this nonlinearity is due to amplification of energy carried by the traveling wave. The alternative hypothesis is that the increase of BM response to a tone near the cochlear best place is due to active processes shaping the BM impedance (i.e., making BM impedance lower so the same energy produces a larger amplitude of motion). It is now generally accepted that cochlear amplification is produced by a cycle-by-cycle injection of energy into the traveling wave. Perhaps the strongest evidence on this issue is the presence in normal ears of spontaneous otoacoustic emissions (see below), which are readily explained by energy being injected on a cycle-by-cycle basis but not by changes in BM impedance that do not inject cycle-by-cycle energy. Model-interpreted measurements show that the cochlear amplifier injects energy into the traveling wave over a short distance just basal to the peak of the traveling wave (de Boer and Nuttall, 2000; Shera, 2007).

A second major question about cochlear amplification has been: What cochlear element provides the motor that drives cochlear amplification? Since cochlear amplification depends on OHCs there have been two candidates: OHC stereocilia motility and OHC somatic motility. One approach to this issue is to look at how fast these motors can perform. OHC somatic motility is driven by membrane voltage and in isolated OHCs the basolateral membrane acts on the OHC receptor current like a low-pass RC (resistance-capacitance) filter with a cut-off frequency that was measured to be in the 100–1000 Hz range (Russell et al., 1986). Since this cut-off frequency is much lower than the highest frequencies of mammalian cochlear amplification, it has been argued that OHC somatic motility cannot be the motor for cochlear amplification. Recent extrapolations to more physiologic conditions suggest that the OHC cut-off frequency could be ten times higher than previous estimates (Johnson et al. 2011). Perhaps more important, piezoelectric coupling of OHCs to the local organ of Corti mechanical impedance may make OHC cut-off frequencies higher in situ than in isolated OHCs (Rabbit et al., 2009). Finally, OHCs appear to operate as high-gain force producers in a feedback loop and this, plus their piezoelectric coupling, allows OHCs to provide cochlear amplification at frequencies far above the cut-off frequency of isolated OHCs (Lu et al., 2006; Meaud and Grosh, 2010). Overall, the argument that OHC low-pass filtering precludes OHC somatic motility from being the motor of mammalian cochlear amplification appears to have little weight.

By contrast, much less consideration has been given to the low-pass filter characteristics of motility from the MET channels in OHC stereocilia. The CM at high frequencies demonstrates that stereocilia MET channels operate at high frequencies and provide fast current flow through mammalian stereocilia. However, there is an inherent low-pass nature to the binding and unbinding of Ca2+ at the presumed MET receptor site. In addition, the current through a small channel must build up the local Ca2+ concentration near this binding site in a process that resembles buffered diffusion. Since stereocilia force production at high frequencies has not been demonstrated experimentally, more exploration is needed to determine whether this may be due to inherent low-pass filtering in MET motility. Although the role of stereocilia-based motility in mammals remains unclear, it is still possible that this process contributes to cochlear amplification (Chan and Hudspeth, 2005; Kennedy et al., 2005; Ashmore et al., 2010).

Conclusive evidence on the motor element of mammalian cochlear amplification has come from experimental manipulations of prestin. Prestin knockout (KO) mice showed a loss of frequency selectivity and sensitivity on the order of 50 dB (Liberman et al., 2002; Cheatham et al., 2004), which provided the first good evidence that OHC motility drives the cochlear amplifier. However, in prestin KO mice, OHCs were only 60% of their normal length and their stiffness was reduced. These changes are important because amplifier gain requires an appropriate mechanical impedance match between the amplifier and its load. If the stiffness of the OHC is reduced, the impedance changes and gain may be decreased. In order to more conclusively examine the role of prestin in cochlear amplification, a knockin (KI) mouse in which only 2 of prestin’s 744 amino acids were altered was developed (Dallos et al., 2008). Even though this mutated prestin protein was produced in normal amounts, targeted the OHC’s basolateral membrane and resulted in normal-length OHCs, a dramatic reduction in motor action was recorded. These experiments conclusively showed that prestin is required for normal cochlear amplification. However, questions remain about the process of cochlear amplification. For instance, in a chimeric mouse, where normal OHCs interleaved with those lacking prestin, sensitivity and frequency selectivity were directly proportional to the number of OHCs expressing prestin (Cheatham et al., 2009). Additional experiments are required to understand how this relationship comes about.

While the above data indicate that the traveling wave is amplified by prestin-mediated somatic motility, important details of how this is accomplished are unclear. Nonetheless, it is useful as a heuristic exercise to consider the steps that seem likely to be involved based on current knowledge. Consider what happens as the BM moves up toward scala vestibuli (Fig. 2). The upward movement of the BM and the organ of Corti produces shearing between the reticular lamina (RL) and the tectorial membrane (TM), which by itself would produce deflection of the OHC stereocilia in the excitatory direction. However, there may be significant TM radial vibrations (see below) that affect the timing of the OHC stereocilia deflections. The stereocilia deflections initiate current flow through the OHC MET channels, which depolarizes the OHC. This OHC depolarization produces an OHC contraction, which pulls the RL and the BM closer together. The resulting upward pull on the BM will add energy to, and amplify, the traveling wave if the pull comes at the right phase during the cycle. The timing of all of these steps is a feature that is poorly understood. There may also be other factors involved, such as stereocilia motility or filtering. This outline of what may be happening is intended to provide an understanding of the factors involved in cochlear amplification. Further investigation is required to determine the exact mechanisms by which cochlear amplification is produced.

Fig. 2.

Steps in the cochlear amplification of basilar membrane (BM) motion for BM movement towards scala vestibuli. 1. The pressure difference across the cochlear partition causes the BM to move up. 2. The upward BM movement causes rotation of the organ of Corti about the foot of the inner pillar (IP), movement of the reticular lamina (RL) toward the modiolus (left) and shear of the RL relative to the tectorial membrane (TM) that deflects stereocilia in the excitatory direction (green arrow). 3. This deflection of outer hair cell (OHC) stereocilia opens mechano-electric-transduction channels, which increases the receptor current driven into the OHC (blue arrow) by the potential difference between the +100 mV endocochlear potential and the ~-40 mV OHC resting potential. The receptor current flowing through the impedance of the hair cell’s basolateral surface depolarizes the cell. In contrast to OHCs that are displacement detectors, inner hair cells (IHC) are sensitive to velocity, at least at low frequencies, because their hair bundles are not firmly imbedded in the overlying TM. 4. OHC depolarization causes conformational changes in individual prestin molecules that sum to induce a reduction in OHC length. The OHC contraction pulls the BM upward toward the RL, which amplifies BM motion when the pull on the BM is in the correct phase. As noted in the text, it also produces downward RL motion in the OHC region and upward motion in the IHC region due to RL pivoting. The downward RL motion in the OHC region is opposite from the RL motion produced in steps 1–2, which effectively applies negative feedback on the RL motion that is the drive to the OHC (see Lu et al., 2006). The RL pivoting and resulting fluid flow in the subtectorial space may provide an additional mechanism by which OHC motility may enhance the mechanical drive to IHC stereocilia (see text section 7).

6. The Tectorial Membrane

The TM is a key element in cochlear amplification because the drive to OHC somatic motility comes from OHC stereocilia being deflected by shear between the RL and the TM. The TM has long been thought to act mainly as a mass at the frequencies relevant for cochlear amplification and not to shape the BM traveling wave. However, in mice with a genetically-altered TM protein (β-tectorin KO mice), high-frequency cochlear sensitivity was reduced but cochlear tuning became sharper (Russell et al., 2007). This result contrasts with previous manipulations where lowered cochlear sensitivity was associated with broader tuning functions. Measurements on excised TMs show that the TM can sustain shear waves that propagate in the longitudinal direction (Ghaffari et al. 2010). In other words, they show TM traveling waves, something foreshadowed in cochlear models (Hubbard, 1993). In β-tectorin KO mice, the spatial extent of the TM traveling wave is reduced in a way that seems to account for the sharper BM traveling wave tuning (Ghaffari et al., 2010). These data suggest that the TM has a greater influence on cochlear tuning and BM responses than has been appreciated (Meaud and Grosh, 2010).

7. Cochlear Micromechanics and the Drive to Inner Hair Cells

The classic view, illustrated in Békésy’s (1960) book, is that the mechanical drive to hair-cell stereocilia comes from shearing between the RL and the TM. In this view, BM motion produces in-phase transverse motions of the TM and organ of Corti, and RL-TM shearing comes from these structures pivoting about different insertion points. However, recent measurements have shown that cochlear micromechanics is more complicated. In the cochlear base of sensitive guinea pigs, the motion in response to a best-frequency sound is 2–3 times larger at the RL than at the BM (Chen et al., 2011). Furthermore, RL and BM responses both grow nonlinearly, but with different patterns. Although in the past the primary interest has been on BM mechanics, it is now focused at the top of the organ of Corti where the micromechanics drive the IHC stereocilia, and ultimately the synaptic events that form the output of the cochlea.

Recent work has provided new insights into the motion patterns driving IHC stereocilia. At low frequencies (~ <3 kHz), OHC contractions cause the RL to pivot about the head of the pillar cells so that when the RL over the OHCs moves down (toward scala tympani), the RL over the IHCs moves up (Nowotny and Gummer, 2006; Jacob et al., 2011). Indirect evidence indicates that OHC contractions may also increase the RL-TM gap (Guinan, 2011). RL pivoting and the resulting gap changes would induce fluid flow in the subtectorial space that deflects IHC stereocilia (Nowotny and Gummer, 2006; Guinan, 2011), thereby providing a way for active OHCs to directly affect IHCs without BM motion as an intermediary. Since, at low frequencies, the force that moves the TM is transmitted primarily through the OHC stereocilia, passive organ of Corti motions from pressure differences across the cochlear partition may also change the RL-TM gap. Again, this could influence fluid flow in the RL-TM gap that drives IHC stereocilia. Speculation suggests that for low frequencies and low sound levels, the main drive to IHCs may relate to RL tilting and the resulting fluid flows in the RL-TM gap, i.e., not from the traditional RL-TM shear. However, much remains to be learned about how changes in the RL-TM gap drive IHC stereocilia, particularly in their phases relative to the traditional RL-TM shear.

8. Otoacoustic Emissions

Békésy demonstrated the existence of forward traveling waves, and in the years since his work it has been found that there are also backward traveling waves that give rise to otoacoustic emissions (OAEs). OAEs are sounds in the ear canal that originate in the cochlea (Kemp 1978). As a traveling wave moves apically it generates distortion due to cochlear nonlinearities (mostly from nonlinear characteristics of the OHC MET channels, the same source that produces the nonlinear growth of BM motion), and encounters irregularities due to variations in cellular properties. As a result, some of this energy travels backwards in the cochlea and the middle ear to produce OAEs. Although most investigators support the idea that the energy for OAEs is carried backward in the cochlea by reverse traveling waves (e.g., Shera et al., 2007; Dong and Olson, 2008; Meenderink, and van der Heijden, 2010), others maintain that this energy is carried by compressional waves in the cochlear fluids (e.g., Ren, 2004; Siegel et al., 2005).

Normal ears sometimes exhibit spontaneous OAEs (SOAEs), and in birds and reptiles stereocilia are thought to be responsible for their generation (Manley, 2001). However, in mammals there is strong evidence that SOAEs arise from multiple reflections of forward and backward traveling waves that are sustained by cochlear amplification (Shera, 2003). In theory these SOAEs can be produced by cochlear amplification from either somatic or stereocilia motility. If OHC somatic electromotility mediates the majority of cochlear amplification, then SOAEs in mammals arises from gain produced by prestin-based mechanisms.

OAE amplitudes provide information about cochlear amplification because the energy for OAEs comes from the traveling wave and the cochlear amplifier amplifies this energy. Since OAEs can be measured with a sensitive microphone in the ear canal, they provide a non-invasive measure of cochlear amplification and cochlear health. Because OAEs have both scientific and clinical utility, they have become the main method for infant hearing-screening tests.

9. Olivocochlear Efferents and Cochlear Physiology

At the time that Békésy was awarded the Nobel Prize, it was known that there were efferent fibers that went from the brainstem to the cochlea, and that shocking efferents in the brainstem inhibited auditory nerve CAPs and increased CM (reviewed by Guinan, 1996). However, the relationship of both efferents and auditory nerve afferents to IHCs and OHCs was not yet known. In the ensuing years, it was shown that (1) myelinated Type I auditory nerve fibers (ANFs) innervate IHCs, and unmyelinated Type II ANFs innervate OHCs, and (2) myelinated medial-olivocochlear (MOC) efferent fibers innervate OHCs while unmyelinated lateral-olivocochlear (LOC) efferent fibers innervate dendrites of Type I ANFs under IHCs. Relatively little is known about the two types of unmyelinated fibers because they are difficult to stimulate and record from. However, inhibition of CAPs from the myelinated, Type I ANFs is now known to be produced by the myelinated MOC fibers (Guinan et al., 1983). How do MOC fibers that innervate OHCs change the firing patterns of ANFs that innervate IHCs?

An important step in answering this question came from the demonstration that stimulating MOC fibers produces changes in otoacoustic emissions (Mountain, 1980; Siegel and Kim, 1982), i.e., MOC fibers produce mechanical effects. Furthermore, the pattern of these effects is consistent with the idea that MOC activity turns down the gain of the cochlear amplifier. MOC fibers release acetylcholine, the neurotransmitter that acts on an unusual acetylcholine receptor on OHCs (Elgoyhen et al., 2001). Activation of these receptors allows the entry of calcium into OHCs, which activates Ca2+-activated K+ channels that hyperpolarize the OHCs (Fuchs, 2002). This change in membrane potential reduces cochlear amplifier gain in two ways: (1) from the synaptic K+ channel conductance shunting OHC receptor currents (Rabbitt, 2009), and (2) by the OHC hyperpolarization moving OHC somatic motility away from its optimum voltage operating point (Santos-Sacchi, 1991). Thus, MOC fibers on OHCs reduce the response of ANFs that innervate IHCs by decreasing OHC force production, thereby turning down the gain of the cochlear amplifier.

Gain reduction does not explain all of the MOC effects on ANF responses to sound. In fibers with high (>10 kHz) CFs, MOC stimulation inhibits responses for “tail-frequency” tones by as much as 10 dB (Stankovic and Guinan, 1999). In contrast, BM measurements show no cochlear amplification at frequencies an octave, or more, below high-frequency BFs. Another example is that in fibers with CFs <4 kHz, MOC stimulation inhibits the auditory nerve initial peak (ANIP) response to high-level clicks (Guinan et al., 2005). Again, this is not readily accounted for by the classic effects of cochlear amplification because the first peak of BM click responses grows linearly and does not receive cochlear amplification, at least for moderate to high levels at the base of the cochlea where BM motion is well characterized. These phenomena may be explained by fluid flow in the RL-TM gap that excites IHCs (Section 7) but more data are needed to clarify these issues.

All of the above MOC phenomena build up and decay on a time scale of ~100 ms but one kind of MOC inhibition builds up and decays on a much longer time scale. Although these “fast” and “slow” MOC effects both reduce BM responses to sound, they result in different BM phase changes, indicating that they originate from separate OHC mechanical changes (Cooper and Guinan, 2003). For example, the slow MOC effect may relate to a stiffness change, since application of acetylcholine reduces OHC stiffness on a slow time scale (Dallos et al., 1997).

These MOC effects appear to have several roles. There is strong evidence that MOC stimulation reduces acoustic trauma and this trauma reduction may be due to the MOC slow effect. However, MOC fast effects may also be involved in reducing acoustic trauma. At high levels MOC activation has little effect on BM cochlear amplification, but it has large effects on BM phase, which shows that MOC fibers produce mechanical changes that affect high-level BM responses (Cooper and Guinan, 2011). A second effect of MOC fibers is to increase the ability to discriminate sounds in a noisy background (Winslow and Sachs, 1988; Kawasa et al., 1993). The MOC-induced reduction of cochlear amplifier gain reduces the response to ongoing, low-level noise more than it reduces the response to higher-level transient sounds (Cooper and Guinan, 2006; but see Russell and Murugasu, 1997). This behavior increases the signal-to-noise ratio of BM responses. The MOC reduction of responses to low-level noise also reduces adaptation at the IHC-ANF synapse. Both of these effects enhance auditory-nerve responses to transient sounds, making them more salient (reviewed by Guinan, 2006). Although there are many investigations that failed to observe MOC antimasking, others have succeeded, and the overall conclusion is that MOC antimasking can enhance hearing but is not a potent factor in all situations.

10. Fluid Physiology, Standing Currents, and Energy Dependence on the Lateral Wall

Békésy’s perspective on the ear reflected the importance of electrical circuits (electrical potentials, boundary resistances, etc.) in understanding physiological systems. This view was also incorporated into Davis’ model (1958) of the same era. These electrical models provided the foundation for our understanding of the physiological processes in the cochlea and the origin of cochlear potentials. In addition, Békésy described the resting potentials throughout the ear, specifically the high positive potential recorded in cochlear endolymph. Although the unique high potassium content of endolymph had been reported (Smith et al., 1954), its significance was not fully appreciated, as the understanding of electrochemistry and the ionic basis of cochlear transduction was to come later. In the electrical models, currents across resistances were driven by voltage differences. Model interpretations changed slightly when it became known that ionic currents through ion channels depend on both ionic concentrations and voltage gradients (i.e., electrochemical gradients). We now know that the current passing through the hair cells is predominantly carried by potassium, passing though non-selective cation channels in the hair cell stereocilia. The potassium passes partially as a current in perilymph but some is recirculated back into endolymph through an epithelial gap junction system mediated by ion transport systems in the organ of Corti and the lateral wall (a.k.a. stria vascularis). When the electrochemistry of this circuit is considered, it can be appreciated that the energy driving transduction is added in a two-step process in the lateral wall. The first step is elevation of the electrochemical potential for potassium by active transport into the fibrocytes, basal cells and intermediate cells (linked together by gap junctions). The second step is the increase in electrochemical potential for potassium generated by active transport in the basolateral membrane of the marginal cells. Both of these steps are accomplished using Na/K/ATPases and metabolic energy to exchange ions. However, the Na/K/ATPases and associated NaKCl cotransporters move ions in an almost electroneutral manner and do not themselves contribute to the major electrical potentials of the ear. In other words, the positive endocochlear potential is not directly generated by these active transport processes but arises from an ion flux through the inward rectifier, KCNJ10, potassium channels in the apical membrane of intermediate cells. This movement is driven by the electrochemical gradient for potassium that the active transport has established. Similarly, the hair cell resting potentials arise from the high potassium permeability of their basolateral membranes and not directly from active ion transport. This knowledge implies that the energy driving transduction currents cannot be inferred from endocochlear and hair cell potentials, as passive ion movements mainly generate these potentials. The source of the energy for transduction, an issue that acutely concerned Békésy, is thought to be provided predominantly by the remote active ion transport in the lateral wall and not by the hair cells themselves. That the energy comes mainly from the lateral wall contrasts with the perspective from electrical models in which the lateral wall and hair cells appear to make similar contributions to the energy driving current circulation. It also explains why the positive endolymphatic potential is absent in the saccule and utricle, which have secretory dark cells (analogous to cochlear marginal cells) but lack the fibrocyte, basal cell and intermediate cell components that provide one step in the elevation of potassium potential in the cochlea (Wangemann, 1995). Nevertheless, even with our present-day understanding of endolymph physiology, there remain perplexing issues. For example, we know that potassium circulates as the so-called transduction current resulting in an endolymph turnover, measured by radiotracer, with a half time of 55 min (Konishi et al., 1978). Yet similar radiotracer measurements show that endolymph chloride turns over almost as quickly as potassium, with a measured half time of 69 min (Konishi and Hamrick, 1978). This similarity suggests chloride currents may be equally important, although we know remarkably little about them. With large circulating potassium currents, we might also expect endolymph volume to be unstable in the face of different current demands through the hair cells. The fact that endolymph volume is remarkably stable may result from the regulation of anions, as electroneutrality prevents anion and cation concentrations from differing. These possibilities require investigation in order to establish and understand the mechanisms underlying local endolymph regulation.

Early on Békésy speculated that there was a constant current flow across the cochlear partition and an associated potential generated in the absence of sound. His experiments on DC potentials in the cochlea and demonstration of sustained potentials to trapezoidal mechanical stimuli showed that there existed a continuous consumption of energy in the cochlea. This observation foreshadowed the result by Zidanic and Brownell (1990) showing a resting or silent current originating in the stria vascularis and flowing through the scala media space. This observed activity in the absence of stimulation probably relates to the fact, as discussed above, that a proportion of the MET channels are open at rest. OHCs with high CFs do not generate slow depolarizing (sometimes called ‘dc’) receptor potentials because the set point of their transducer operating functions is located at a place where the function has its steepest slope, thereby maximizing gain. Variations around this set point average to zero over a stimulus tone cycle. In contrast, in IHCs the relationship between MET conductance and cilia deflection is nonlinear even for low-level inputs so that variations around the set point do not average to zero over a stimulus-tone cycle, which accounts for the asymmetry of IHC receptor potentials. Except at low frequencies where phasic or ‘ac’ receptor potentials can induce transmitter release, it is this dc receptor potential in IHCs that gives rise to transmission of high-frequency information to the auditory nerve.

11. Cochlear Pathologies Including Noise Damage and Aging

In a review of Békésy’s work, Tonndorf (1986) points out that “Békésy was the first to study function of the auditory organ experimentally, replacing theoretical considerations with experimental evidence”. While most of his publications were focused on how the normal ear and other sensory systems transduced their specific inputs into a form that the brain could utilize, he also played a pivotal role in the emerging fields of audiometry and audiology. He established Békésy audiometry, an automated tracking procedure in which the subject held a button when they heard a tone, during which the tone level was slowly decreased, and released the button when they could not hear the tone, during which the tone level was slowly increased. He also published on the subject of loudness recruitment, which was pertinent to the increasing use of electronic hearing aids at the time. But Békésy could never have imagined the growth of interactions between scientists and clinicians in the area of pathologies of the ear that has taken place over the past 50 years. Studies of noise effects on the ear have led to industrial noise-exposure regulations, increased use of hearing protection devices and hearing conservation programs. In recent years there is mounting evidence that protective drug therapies, given either pre- or post-exposure, may ameliorate the damage to hearing by loud sound. We are also beginning to realize that noise can have complex effects not just limited to OHC loss. In fact, noise can produce damage to the lateral wall (Hirose & Liberman, 2003) and excitotoxic effects at afferent synapses that can cause loss of afferent fibers after noise, even when the measured sensitivity of the ear recovers fully (Lin et al., 2011). In clinical practice, measures of auditory and vestibular function now play an important part in the diagnosis and treatment of conditions such as Meniere’s disease, otosclerosis and acoustic neuroma. We are also beginning to understand the progressive deterioration of inner ear function with age that is manifest as presbycusis. Similar to the situation with noise, there is now evidence that age-related hearing loss can arise not only from deterioration and loss of sensory hair cells, but also from a decline of ion transport processes in the lateral wall with concomitant reduction of the endocochlear potential (Schuknecht, 1974; Gratton et al., 1996). As we increasingly understand the underlying physiology of these conditions, we move closer to the goal of diagnosing the specific types of hearing loss, and perhaps determining the tissues and structures involved for each individual patient, in order to optimize therapies for specific conditions.

Nowhere is this more important than in the field of genetic deafness, where screening can now establish the genes, proteins and affected cell types underlying the deafness. While therapies for deafness have advanced with the widespread availability of cochlear implants, there are ongoing advances that will expand the benefits of these devices. The use of “soft” surgical techniques that preserve residual low-frequency hearing in the implanted ear allows patients with high-frequency hearing loss to benefit from implantation (Lehnhardt, 1993). This advance has expanded the use of hybrid cochlear implants in what is now called electroacoustic stimulation (Gantz and Turner, 2004). The use of local drug therapies, such as steroids or neurotrophins, in conjunction with cochlear implantation is also likely to improve patient outcomes. And finally, we are presently on the cusp of a new era in the treatment of inner ear disorders, which is the use of gene, cellular, and stem-cell regenerative therapies to restore hearing in the deafened ear. This has to be seen as the ultimate test of our knowledge of development, function, pathology and regenerative therapy of the ear. In recent years, endolymphatic injections have been utilized to deliver siRNAs (Sellick et al, 2008) and genes such as Atoh1 (Kawamoto et al, 2003) that have been reported to induce new hair cells in the deafened cochlea. Many issues remain before these experimental results can become clinical procedures but they offer the promise of curing or ameliorating many conditions that are now untreatable.

A major driver of the changes that have taken place since Békésy’s era has been the development of less invasive procedures for monitoring and manipulating the inner ear. Such techniques allow sophisticated measurements to be made with the ear in as close to a physiologically normal state as possible. There are still limitations to many of our techniques, but as new methodologies are developed, we can look forward to the opening of areas of cochlear physiology that are still unknown. Given the huge advances in the past 50 years, it will be interesting to see how our understanding of the ear changes in the next 50. Will we be able to use new techniques and new genetic information to fix a broken cochlea?

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Wei Zhao for comments on the manuscript. Supported by NIH RO1 DC000235, RO1 DC005977, P30 DC005209, RO1 DC01368, R01 DC00089.

List of Abbreviations

- ANF

auditory nerve fiber

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- BM

basilar membrane

- Ca2+

calcium ion

- CAP

compound action potential

- CF

characteristic frequency

- CM

cochlear microphonic

- EP

endocochlear potential

- IHC

inner hair cell

- IP

inner pillar

- K+

potassium ion

- KI

knockin

- KO

knockout

- LOC

lateral olivocochlear

- MET

mechano-electrical transduction

- MOC

medial olivocochlear

- OAE

otoacoustic emission

- OHC

outer hair cell

- RC

resistance-capacitance

- RL

reticular lamina

- siRNA

short interfering ribonucleic acid

- SM

scala media

- TM

tectorial membrane

Contributor Information

John J. Guinan, Jr., Email: jjg@epl.meei.harvard.edu.

Alec Salt, Email: salta@ent.wustl.edu.

Mary Ann Cheatham, Email: m-cheatham@northwestern.edu.

References

- Adrian ED. Report of A Discussion on Audition, Phys Soc London. 1931. The microphonic action of the cochlea in relation to theories of hearing; pp. 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ashmore J, Avan P, Brownell WE, Dallos P, Dierkes K, Fettiplace R, Grosh K, Hackney CM, Hudspeth AJ, Julicher F, Lindner B, Martin P, Meaud J, Petit C, Santos-Sacchi J, Canlon B. The remarkable cochlear amplifier. Hear Res. 2010;266:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashmore J. A fast motile response in guinea-pig outer hair cells: the cellular basis of the cochlear amplifier. J Physiol. 1987;388:323–347. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashmore J. Cochlear outer hair cell motility. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:173–210. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell WE, Bader CR, Bertrand D, de Ribaupierre Y. Evoked mechanical response of isolated cochlear outer hair cells. Science. 1985;277:194–196. doi: 10.1126/science.3966153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan DK, Hudspeth AJ. Ca(2+) current-driven nonlinear amplification by the mammalian cochlea in vitro. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:149–55. doi: 10.1038/nn1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheatham MA, Huynh KH, Gao J, Zuo J, Dallos P. Cochlear function in Prestin knockout mice. J Physiol. 2004;560:821–30. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.069559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheatham MA, Low-Zeddies S, Naik K, Edge R, Zheng J, Anderson CT, Dallos P. A chimera analysis of prestin knock-out mice. J Neurosci. 2009;29:12000–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1651-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Zha D, Fridberger A, Zheng J, Choudhury N, Jacques SL, Wang RK, Shi X, Nuttall AL. A differentially amplified motion in the ear for near-threshold sound detection. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:770–4. doi: 10.1038/nn.2827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper NP, Guinan JJ., Jr Separate mechanical processes underlie fast and slow effects of medial olivocochlear efferent activity. J Physiol. 2003;548:307–312. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.039081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper NP, Guinan JJ., Jr Efferent-mediated control of basilar membrane motion. J Physiol. 2006;576:49–54. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.114991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper NP, Guinan JJ., Jr . Efferent insights into cochlear mechanics. In: Shera CA, Olson ES, editors. What Fire is in Mine Ears: Progress in Auditory Biomechanics. Vol. 1403. American Institute of Physics; Melville, New York, USA: 2011. pp. 396–402. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper NP, Rhode WS. Nonlinear mechanics at the apex of the guinea-pig cochlea. Hear Res. 1995;82:225–243. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)00180-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallos P, Harris DM. Properties of auditory nerve responses in absence of outer hair cells. J Neurophysiol. 1978;41:365–383. doi: 10.1152/jn.1978.41.2.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallos P, He DZ, Lin X, Sziklai I, Mehta S, Evans BN. Acetylcholine, outer hair cell electromotility, and the cochlear amplifier. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2212–2216. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-06-02212.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallos P, Santos-Sacchi J, Flock Å. Intracellular recordings from cochlear outer hair cells. Science. 1982;218:582–584. doi: 10.1126/science.7123260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallos P, He DZ, Lin X, Sziklai I, Mehta S, Evans BN. Acetylcholine, outer hair cell electromotility, and the cochlear amplifier. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2212–2226. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-06-02212.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallos P, Wu X, Cheatham MA, Gao J, Zheng J, Anderson CT, Jia S, Wang X, Cheng WH, Sengupta S, He DZ, Zuo J. Prestin-based outer hair cell motility is necessary for mammalian cochlear amplification. Neuron. 2008;58:333–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis H. Transmission and transduction in the cochlea. Laryngoscope. 1958;48:359–382. doi: 10.1002/lary.5540680314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis H. Audition; a physiological survey. Science. 1949;109:442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer E, Nuttall AL. The mechanical waveform of the basilar membrane. II. From data to models--and back. J Acoust Soc Am. 2000;107:1487–96. doi: 10.1121/1.428435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong W, Olson ES. Supporting evidence for reverse cochlear traveling waves. J Acoust Soc Am. 2008;123:222–40. doi: 10.1121/1.2816566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgoyhen AB, Vetter D, Katz E, Rothlin C, Heinemann S, Boulter J. Alpha 10: A determinant of nicotinic cholinergic receptor function in mammalian vestibular and cochlear mechanosensory hair cells. PNAS. 2001;98:3501–3506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051622798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans BN, Dallos P. Stereocilia displacement induced somatic motility of cochlear outer hair cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8347–8351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flock Å. Transducing mechanisms in the lateral line canal organ receptors. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1965;30:133–145. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1965.030.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank G, Hemmert W, Gummer AW. Limiting dynamics of high-frequency electromechanical transduction of outer hair cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4420–4425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs P. The synaptic physiology of cochlear hair cells. Audiol Neurootol. 2002;7:40–4. doi: 10.1159/000046862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantz B, Turner C. Combining acoustic and electrical speech processing: Iowa/Nucleus hybrid implant. Acta Otolaryngol. 2004;124:344–347. doi: 10.1080/00016480410016423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaffari R, Aranyosi AJ, Richardson GP, Freeman DM. Tectorial Membrane Traveling Waves Underlie Abnormal Hearing in Tectb Mutant Mice. Nat Commun. 2010;1:96. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie PG, Müller U. Mechanotransduction by hair cells: Models, molecules, and mechanisms. Cell. 2009;139:33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinan JJ., Jr . The Physiology of Olivocochlear Efferents. In: Dallos PJ, Popper AN, Fay RR, editors. The Cochlea. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1996. pp. 435–502. [Google Scholar]

- Guinan JJ., Jr Olivocochlear Efferents: Anatomy, Physiology, Function, and the Measurement of Efferent Effects in Humans. Ear Hear. 2006;27:589–607. doi: 10.1097/01.aud.0000240507.83072.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinan JJ., Jr . Mechanical excitation of IHC stereocilia: An attempt to fit together diverse evidence. In: Shera CA, Olson ES, editors. What Fire is in Mine Ears: Progress in Auditory Biomechanics. Vol. 1403. American Institute of Physics; Melville, New York, USA: 2011. pp. 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Guinan JJ, Jr, Lin T, Cheng H. Medial-olivocochlear-efferent inhibition of the first peak of auditory-nerve responses: Evidence for a new motion within the cochlea. J Acoust Soc Am. 2005;118:2421–2433. doi: 10.1121/1.2017899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinan JJ, Jr, Warr WB, Norris BE. Differential olivocochlear projections from lateral vs. medial zones of the superior olivary complex. J Comp Neurol. 1983;221:358–370. doi: 10.1002/cne.902210310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratton MA, Schmiedt RA, Schulte BA. Age-related decreases in endocochlear potential are associated with vascular abnormalities in the stria vascularis. Hear Res. 1996;102:181–190. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(96)90017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose K, Liberman MC. Lateral wall histopathology and endocochlear potential in the noise-damaged mouse cochlea. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2003;3:339–352. doi: 10.1007/s10162-002-3036-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt JR, Corey DP. Two mechanisms for transducer action in vertebrate hair cells. PNAS. 2000;97:11730–11735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.22.11730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard A. A traveling-wave amplifier model of the cochlea. Science. 1993;259:68–71. doi: 10.1126/science.8418496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasa KH. A two-state piezoelectric model for outer hair cell motility. Biophys J. 2001;81:2495–2506. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75895-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob S, Pienkowski M, Fridberger A. The endocochlear potential alters cochlear mechanics. Biophys J. 2011;100:2586–2594. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Beurg M, Marcotti W, Fettiplace R. Prestin-driven cochlear amplification is not limited by the outer hair cell membrane time constant. Neuron. 2011;70:1143–54. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinec F, Holley MC, Iwasa KH, Lim DJ, Kachar B. A membrane-based force generation mechanism in auditory sensory cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8671–8675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasa T, Delgutte B, Liberman MC. Antimasking effects of the olivocochlear reflex. II. Enhancement of auditory-nerve response to masked tones. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:2533–2549. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.6.2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto K, Ishimoto S, Minoda R, Brough DE, Raphael Y. Math1 gene transfer generates new cochlear hair cells in mature guinea pigs in vivo. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4395–4400. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-11-04395.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp DT. Stimulated acoustic emissions from within the human auditory system. J Acoust Soc Am. 1978;64:1386–1391. doi: 10.1121/1.382104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy HJ, Evans MG, Crawford AC, Fettiplace R. Fast adaptation of mechanoelectrical transducer channels in mammalian cochlear hair cells. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:832–6. doi: 10.1038/nn1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy HJ, Crawford AC, Fettiplace R. Force generation by mammalian hair bundles supports a role in cochlear amplification. Nature. 2005;433:880–3. doi: 10.1038/nature03367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi T, Hamrick PE, Walsh PJ. Ion transport in guinea pig cochlea. I. Potassium and sodium transport. Acta Otolaryngol. 1978;86:22–34. doi: 10.3109/00016487809124717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi T, Hamrick PE. Ion transport in the cochlea of guinea pig. II. Chloride transport. Acta Otolaryngol. 1978;86:176–184. doi: 10.3109/00016487809124734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehnhardt E. Intracochlear placement of cochlear implant electrodes in soft surgery technique. HNO. 1993;41:356–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman MC, Gao J, He DZ, Wu X, Jai S, Zuo J. Prestin is required for electromotility of the outer hair cell and for the cochlear amplifier. Nature. 2002;419:300–304. doi: 10.1038/nature01059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin HW, Furman AC, Kujawa SG, Liberman MC. Primary neural degeneration in the Guinea pig cochlea after reversible noise-induced threshold shift. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2011;12:605–616. doi: 10.1007/s10162-011-0277-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu TK, Zhak S, Dallos P, Sarpeshkar R. Fast cochlear amplification with slow outer hair cells. Hear Res. 2006;214:45–67. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley GA. Evidence for an active process and a cochlear amplifier in nonmammals. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:541–549. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.2.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P, Mehta AD, Hudspeth AJ. Negative hair-bundle stiffness betrays a mechanism for mechanical amplification by the hair cell. PNAS. 2000;97:12026–12031. doi: 10.1073/pnas.210389497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P, Bozovic D, Choe Y, Hudspeth AJ. Spontaneous oscillation by hair bundles of the bullfrog’s sacculus. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4533–4548. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-11-04533.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaud J, Grosh K. The effect of tectorial membrane and basilar membrane longitudinal coupling in cochlear mechanics. J Acoust Soc Am. 2010;127:1411–21. doi: 10.1121/1.3290995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meenderink SW, van der Heijden M. Reverse cochlear propagation in the intact cochlea of the gerbil: evidence for slow traveling waves. J Neurophysiol. 2010;103:1448–55. doi: 10.1152/jn.00899.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountain DC. Changes in endolymphatic potential and crossed olivocochlear bundle stimulation alter cochlear mechanics. Science. 1980;210:71–72. doi: 10.1126/science.7414321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakoshi M, Wada H. Atomic force microscopy in studies of the cochlea. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;493:401–13. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-523-7_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowotny M, Gummer AW. Nanomechanics of the subtectorial space caused by electromechanics of cochlear outer hair cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2120–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511125103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver D, He DZ, Klocker N, Ludwig J, Schulte U, Waldegger S, Ruppersberg JP, Dallos P, Fakler B. Intracellular anions as the voltage sensor of prestin, the outer hair cell motor protein. Science. 2001;292:2340–2343. doi: 10.1126/science.1060939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson ES, Duifhuis H, Steele CR. von Békésy and cochlear mechanics. Hear Res. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2012.04.017. (submitted for Békésy Jubilee Issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patuzzi RB, Yates GK, Johnstone BM. The origin of the low-frequency microphonic in the first cochlear turn of guinea-pig. Hearing Res. 1989;39:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(89)90089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbitt RD, Clifford S, Breneman KD, Farrell B, Brownell WE. Power efficiency of outer hair cell somatic electromotility. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000444. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren T. Reverse propagation of sound in the gerbil cochlea. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:333–4. doi: 10.1038/nn1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhode WS. Observations of the vibration of basilar membrane in squirrel monkeys using the Mössbauer technique. J Acoust Soc Am. 1971;49:1218–1231. doi: 10.1121/1.1912485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles L, Ruggero MA. Mechanics of the mammalian cochlea. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:1305–1352. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.3.1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell IJ, Kössl M. The voltage responses of hair cells in the basal turn of the guinea-pig cochlea. J Physiol. 1991;435:493–511. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell IJ, Murugasu E. Medial efferent inhibition suppresses basilar membrane responses to near characteristic frequency tones of moderate to high intensities. J Acoust Soc Am. 1997;102:1734–1738. doi: 10.1121/1.420083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell IJ, Sellick PM. Intracellular studies of hair cells in the mammalian cochlea. J Physiol (Lond) 1978;284:261–290. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell IJ, Cody AR, Richardson GP. The responses of inner and outer hair cells in the basal turn of the guinea-pig cochlea and in the mouse cochlea grown in vitro. Hear Res. 1986;22:199–216. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(86)90096-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell IJ, Legan PK, Lukashkina VA, Lukashkin AN, Goodyear RJ, Richardson GP. Sharpened cochlear tuning in a mouse with a genetically modified tectorial membrane. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:215–23. doi: 10.1038/nn1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Sacchi J, Song L, Zheng J, Nuttall AL. Control of mammalian cochlear amplification by chloride anions. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3992–3998. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4548-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Sacchi J. Reversible inhibition of voltage-dependent outer hair cell motility and capacitance. J Neurosci. 1991;11:3096–110. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-10-03096.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuknecht H. Pathology of the Ear. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1974. pp. 388–403. [Google Scholar]

- Sellick P, Layton MG, Rodger J, Robertson D. A method for introducing non-silencing siRNA into the guinea pig cochlea in vivo. J Neurosci Methods. 2008;167:237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JH, Kim DO. Efferent neural control of cochlear mechanics? Olivocochlear bundle stimulation affects cochlear biomechanical nonlinearity. Hearing Res. 1982;6:171–182. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(82)90052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JH, Cerka AJ, Recio-Spinoso A, Temchin AN, van Dijk P, Ruggero M. Delays of stimulus-frequency otoacoustic emissions and cochlear vibrations contradict the theory of coherent reflection filtering. J Acoust Soc Am. 2005;118:2434–2443. doi: 10.1121/1.2005867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shera CA. Mammalian spontaneous otoacoustic emissions are amplitude-stabilized cochlear standing waves. J Acoust Soc Am. 2003;114:244–62. doi: 10.1121/1.1575750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shera CA. Laser amplification with a twist: traveling-wave propagation and gain functions from throughout the cochlea. J Acoust Soc Am. 2007;122:2738–58. doi: 10.1121/1.2783205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shera CA, Tubis A, Talmadge CL, de Boer E, Fahey PF, Guinan JJ., Jr Allen-Fahey and related experiments support the predominance of cochlear slow-wave otoacoustic emissions. J Acoust Soc Am. 2007;121:1564–75. doi: 10.1121/1.2405891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CA, Lowry OH, Wu ML. The electrolytes of the labyrinthine fluids. Laryngoscope. 1954;64:141–153. doi: 10.1288/00005537-195403000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stankovic KM, Guinan JJ., Jr Medial efferent effects on auditory-nerve responses to tail-frequency tones I: Rate reduction. J Acoust Soc Am. 1999;106:857–869. doi: 10.1121/1.427102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasaki I, Davis H, Legouix The space-time pattern of the cochlear microphonics (guinea pig) as recorded by differential electrodes. J Acoust Soc Am. 1952;24:502–519. [Google Scholar]

- Tonndorf J. Georg von Békésy and his work. Hear Res. 1986;22:3–10. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(86)90067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wangemann P. Comparison of ion transport mechanisms between vestibular dark cells and strial marginal cells. Hear Res. 1995;90:149–157. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00157-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wever EG, Bray C. Action currents in the auditory nerve in response to acoustic stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci US. 1930;16:344–350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.16.5.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winslow RL, Sachs MB. Single-tone intensity discrimination based on auditory-nerve rate responses in backgrounds of quiet, noise, and with stimulation of the crossed olivocochlear bundle. Hear Res. 1988;35:165–189. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(88)90116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Békésy G. Experiments in Hearing. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Zenner HP, Zimmermann U, Schmitt U. Reversible contraction of isolated mammalian cochlear hair cells. Hear Res. 1985;18:127–33. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(85)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Shen W, He DZ, Long KB, Madison LD, Dallos P. Prestin is the motor protein of cochlear outer hair cells. Nature. 2000;405:149–55. doi: 10.1038/35012009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zidanic M, Brownell WE. Fine structure of the intracochlear potential field. I. The silent current. Biophys J. 1990;57:1253–1268. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82644-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]