Abstract

Background

Through play children exercise their emerging mental abilities, and for their part, when in collaborative play, caregivers often adjust their behaviours to assist their children’s progress. In this study, we focused on comparisons between play of Down Syndrome (DS) children with their two parents as well as on comparisons between the two parents’ play behaviours.

Method

Altogether 40 parent–child dyads participated: 20 children with DS (M age = 36.14 months) with their mothers and separately with their fathers. We coded participants’ play behaviours during child solitary and mother–child and father–child collaborative sessions.

Results

Although children increased exploratory play from solitary to collaborative sessions with both parents, symbolic play increased only during joint play with fathers. Fathers displayed less symbolic and more exploratory activity compared to mothers. Mothers and fathers alike were attuned to their children, although fathers showed a higher degree of attunement.

Conclusions

This study shows that maternal and paternal contributions to DS child play skills are positive but different. During collaborative play children received specific and nonoverlapping scaffolding from their two parents, and fathers’ contributions were unique.

Keywords: Down Syndrome, father, intellectual disabilities, parent–child interaction, play

Introduction

Much of children’s first learning and many of their first experiences occur during play (Piaget 1962; Vygotsky 1978; Tamis-LeMonda & Bornstein 1996; Bornstein 2007). Moreover, as children grow, more mature cognitive skills emerge and motivate increasingly sophisticated play. Caregiver involvement in child play activities enhances the frequency, the duration, and the complexity of child play both in typically developing children and in children with intellectual disabilities (Cielinski et al. 1995 Bornstein et al. 1996, 2002; Venuti et al. 1997, 2008). In the present study, we focus on children with Down Syndrome (DS), the most common genetic cause of intellectual disabilities. Despite the fact that play is integral to every child’s development, to date specific contributions of parental play to the play of children with DS have not been adequately explored. Moreover, the majority of studies have involved mothers (e.g. Marcheschi et al. 1990; Cielinski et al. 1995; Roach et al. 1998), and no studies (we could find) have directly compared father- with mother–child play in children with DS. The main aim of the present study was therefore to focus on comparisons between play of children with DS with their two parents as well as on comparisons between the two parents’ play behaviours.

The development of play follows universal trends, as consistently attested by the literature, both for typically developing children and for children with DS (Hill & McCune-Nicolich 1981; Cunningham et al. 1985; Beeghly & Cicchetti 1987; Mundy et al. 1987). Simple sensorimotor object exploration and manipulation tend to wane during the first years of life, whereas more complex and hierarchically integrated forms of play, such as combinatorial and symbolic play, wax. This progression has been associated with the emergence of new cognitive skills in the child, a reason why maturity in play is traditionally thought to index children’s overall cognitive level (Piaget 1962; Hill & McCune-Nicolich 1981; Beeghly & Cicchetti 1987). Although some investigators have reported that children with DS tend to repeat the same play schemes more often than do typically developing children, both the course and content of symbolic play in children with DS appear markedly similar to those observed in typically developing children of the same cognitive level (McCune-Nicholich 1981; Cunningham et al. 1985; Beeghly et al. 1989; Cielinski et al. 1995; Sigman & Ruskin 1999). In contrast, exploratory play appears to be compromised in children with DS, even when compared with mental age matched typically developing children (Krakow & Kopp 1982; Brooks-Gunn & Lewis 1984; Sigman & Sena 1993; Venuti et al. 2008), and this difference has been attributed to the lack of exploratory competence or object mastery in DS children (Landry & Chapieski 1989; Ruskin et al. 1994). Other possible reasons for the exploratory play deficit might be related to other compromised areas in DS, such as motor development (Vicari 2006), initiation (Schaefer & Armentrout 2002) and instrumental thinking (Fidler 2006).

Against these clear developmental trends in children’s play, there are significant dyadic effects. The role of caregiver in the development of play in typically developing children is a recurrent topic in the literature (Fiese 1990; Bornstein et al. 1996; Noll & Harding 2003). The presence of the parent during play and his/her specific behaviours exert a powerful influence on the amount, duration, and complexity of child play. By providing adequate scaffolding during collaborative play, parents help their children to practice more sophisticated behaviours (and underlying mental skills) they can potentially reach. Concerning DS children specifically, Cielinski et al. (1995) found that child play sophistication was higher during collaborative play with mother than during solitary play, but the authors did not address the quantity of exploratory and symbolic play activities separately. Venuti et al. (2008), who considered the amounts of both exploratory and symbolic play, found that the presence of the mother during play resulted in more child exploratory, but not symbolic play. Moreover, a positive link between the affective quality of parent–child interaction and the play skills of children with DS have been found; that is, within interactions of higher affective quality, children with DS display more sophisticated play behaviours (Marcheschi et al. 1990; de Falco et al. 2008; Venuti et al. 2008).

Starting from the fact that both parents may be emotionally and practically involved in childrearing (Lamb 1997a,b; Parke 2002), recently investigators have drawn attention to the importance of fathers in the development of children with intellectual disabilities. There is a growing body of literature on fathers’ adaptation, stress, and coping skills when facing the challenges of parenting a child with intellectual disability whatever the etiology (Olsson & Hwang 2001; Glidden et al. 2006; Shin et al. 2006), and some studies have now specifically focused on fathers of children with DS (Ricci & Hodapp 2003; Hodapp 2007; Stoneman 2007; Senese et al. 2008). However, there is still a dearth of observational research on actual interactions between fathers and children with intellectual disabilities.

Yet, there are significant reasons to extend to fathers the investigation of parent–child play interaction with DS children. First, in typical development, theorists and researchers agree that fathers foster their children development specifically through play (Hewlett 1992; Caneva & Venuti 1998; Parke 2002). Fathers, compared to mothers, spend less time in caregiving and more time in play activities, and therefore a paternal role of playmate has been frequently described in the literature (Lamb 1977a,b; Parke 1996; Venuti & Giusti 1996). Therefore, it might be the case that when playing with their children with DS fathers have a more powerful effect compared to mothers in enhancing their children’s play skills. Another reason to deepen our knowledge about interactions between fathers and children with DS is that, although both parents of children with intellectual disabilities suffer from parenting stress and decreased levels of well-being (Roach et al. 1999; Hodapp 2002), according to some authors fathers compared to mothers experience less stress and feel themselves more in control of the situation (Goldberg et al. 1986; Bristol et al. 1988; Damrosch & Perry 1989; Olsson & Hwang 2001; Shin et al. 2006). It might be the case that the maternal and paternal contributions to the development of children with DS may differ as a result of these differences in feelings and emotional reactions.

This study takes a closer look at parent–child play in children with DS, focusing on comparisons across three observed play situations: child solitary play, child collaborative play with mother, and child collaborative play with father. Specifically we studied: (i) how DS child play differs in solitary and in collaborative situations with mother or father; (ii) how maternal and paternal play with their DS children differs in collaborative play situations; (iii) if paternal and maternal play behaviours are associated to one another; and (iv), finally, if there are associations between children and each parent’s play during collaborative play.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Altogether 40 parent–child dyads participated in this study: 20 children with DS (Chronological age: M = 36.14 months; SD = 10.25 range = 18–48. Developmental age: M = 19.95 months; SD = 5.95 range = 10–26) with their mothers (M age = 36.00 years; SD = 5.79) and the same children with their fathers (M age = 38.95 years; SD = 6.41). All children had the Trisomy 21 type, confirmed by chromosomal analysis. Children were recruited from an Early Intervention Centre in the metropolitan area of Naples. The Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development (2nd Edition, Bayley 1993) were used to determine the developmental age of children with DS. The socioeconomic status of the parents, calculated with the Four-Factor Index of Social Status (SES; Hollingshead 1975), indicated a low- to middle-status in the Italian population (M = 28.67; SD = 13.98). We individually contacted the mothers of 18- to 50-month-old children with DS (n = 20) who were regularly attending the Centre and living with their married biological parents. As is common in studies on clinical populations, our sample was not homogeneous or balanced demographically. It included 13 boys and seven girls, and child chronological age varied widely. However, children’s age range does not differ from other studies in the literature focusing on young children with DS (Cielinski et al. 1995; Fewell et al. 1997; Libby et al. 1997). Two children had very low overall developmental age (<12 months), however all participants could perform at least one behaviour classified as ‘self directed pretence’ (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Play coding scheme

| Play levels | Description |

|---|---|

| Exploratory play | |

| 1. Unitary functional activity | Production of effects that were unique to a single object (e.g. dialing a telephone). |

| 2. Inappropriate combinatorial activity | Inappropriate juxtaposition of two or more objects (e.g. putting the ball on the telephone). |

| 3. Appropriate combinatorial activity | Appropriate juxtaposition of two or more objects (e.g., putting the handset on the telephone base). |

| 4. Transitional play | Approximated pretence but without confirmatory evidence (e.g. putting the telephone handset to ear without vocalization). |

| Symbolic play | |

| 5. Self-directed pretence | Pretence activity directed toward self (drinking from an empty cup). |

| 6. Other-directed pretence | Pretence activity directed towards someone or something else (e.g. putting a doll to sleep). |

| 7. Sequential pretence | Linking two or more pretence actions (e.g. pouring into an empty cup from the teapot and then drinking). |

| 8. Substitution pretence | One or more object substitutions (e.g. pretending a cup is a telephone and talking into it). |

| No play | Absence of play or behaviours not included above (e.g. non functional manipulation of the toys, physical games without toys). |

Procedure

The present study followed a standardized protocol. Data were collected during three consecutive 10 min sessions that were vide recorded continuously by a female filmer. Observations took place at the Intervention Centre in a quiet room, which was familiar to the participants. A set of standard, age-appropriate toys was used that represented feminine, masculine, and gender-neutral categories (Caldera et al. 1989). During the first session (solitary play), the child played with the toy set on his or her own, while the parents were asked to fill out a questionnaire. During the second and third sessions (collaborative play), the mother or the father were asked to play with the child the way she/he typically would and to disregard the filmer’s presence as much as possible. Mothers/fathers and children could use any or all of the toys provided; the child’s own toys were not present. The order of the mother and father collaborative play sessions was counterbalanced.

The same play coding system was applied to the child’s play and to the mother’s and the father’s play. This play code focuses on the behaviours of one individual at a time. Therefore, for each child the coding was separately applied five times, i.e. to the child’s behaviours in the three sessions (solitary, collaborative with mother and collaborative with father), as well as to the father’s behaviours and to the mother’s behaviours in the collaborative sessions.

As described in Table 1, the play coding consists of a mutually exclusive and exhaustive category system that included eight levels and a default (no play) category (see Bornstein & O’Reilly 1993; Bornstein et al. 1996; Tamis-LeMonda & Bornstein 1996); these play levels were derived from previous research on the progressive nature of play across the first years of life.

Levels 1–4 constitute the macro-category Exploratory play, and Levels 5–8 constitute the macro-category Symbolic play. Altogether exploratory and symbolic macrocategories and the default ‘no-play’ category allow for exhaustive coding of the play sessions.

Play was coded continuously by noting play level as well as start times and end times (accurate to 1 s). Minimum play time was set to 1 s, and play at a given level was coded so long as there was no break longer than 10 s and the player did not touch another object. For each level four measures were calculated: the absolute frequency, the proportional frequency, the absolute duration, and the proportional duration. As these measures have been found to be consistently highly correlated in previous studies (see Bornstein et al. 1996), and showed high correlations in our sample (rs range = 0.48 to 0.86, Ps < 0.01), their mean standard score was used as a summary index representing the amount of each play level and each macro-category. It was not possible to have the complete 10 min play session for four dyads; the minimum duration of these incomplete sessions was 7.5 min, and therefore we coded the first 450 s for every session. Coding was carried out by three independent coders on 25% of the sessions to evaluate coding reliability. Average kappas between coders for the eight play levels play ranged from 0.75 to 0.83. Play coders were blind to hypotheses and purposes of the study and to additional information about the dyads.

Results

Analytic plan

We first conducted preliminary analyses of the data. Then, we report descriptive statistics for child solitary and collaborative play, and for mother and father play. For purposes of illustration and clarity, descriptive statistics and figures report durations of play (in s). All the analyses were conducted on the summary indexes of exploratory and symbolic play which were highly correlated with durations and frequencies (see procedure).

For our first aim, separate repeated-measures anovas were used to evaluate child exploratory and symbolic play summary indexes across the three situations; Tukey HSD were used, where appropriate, as post-hoc tests. For our second aim, independent t-tests were performed to compare maternal and paternal summary indexes of exploratory and symbolic play. For our third aim, correlation analyses were carried out between maternal and paternal summary indexes of play. Finally, for our fourth aim, regarding the attunement in play between each child and his/her parent, correlation analyses between child and parent play summary indexes in the collaborative situations were used; moreover, we analysed the probability of co-occurrence of the same play level between the child and the parent applying the Yule’s Q statistic to mother–child and father–child collaborative sessions. Yule’s Q is an index of association that represents a transformation of the Odds Ratio, and it varies from −1 and +1, with 0 representing no effects.

Preliminary analyses

Prior to formal data analysis, all the dependent variables and potential covariates were examined for normalcy, homogeneity of variance, outliers, correlations among variables, and influential cases (Fox 1997). Transformations were applied to resolve problems of nonnormalcy, and residuals were examined for influential points. The distance of each case to the centroid was evaluated to screen for multivariate outliers (see Bollen 1987; Tabachnick & Fidell 1996). Preliminary correlations were conducted to investigate associations between demographic variables and play measures. A significant correlation between maternal age and the summary index of child exploratory play in the mother–child collaborative session was found, r(18) = −0.52, P < 0.005. Consistent with the play general progression, developmental age showed a positive association with child solitary symbolic play (r(18) = 0.33, ns) and a negative association with child solitary exploratory play (r(18) = −0.11, ns), however these correlations were not significant. In addition, we divided our sample in two subgroups, one with lower developmental age (n = 8; range = 10–18 months; M = 14.00, SD = 2.67) and one with higher developmental age (n = 12; range = 20–26 months; M = 23.64, SD = 2.07); these two groups were compared for symbolic and exploratory child play in the solitary session. We found that, accordingly with the play general developmental trend, the amount of symbolic play tended to be higher in children with higher developmental age (M = 80 s, SD = 81 s) then in children with lower developmental age (M = 67 s, SD = 85 s); however there were no significant differences between the two groups and this may be due to the small n of the groups, F(1, 19) = 1.23, ns. As for exploratory play, we did not find differences between the lower (M = 41 s, SD = 47 s) and the higher (M = 44 s, SD = 54 s) developmental age groups, F(1, 19) = 0.27, ns. Therefore, the subsequent analyses were carried out on the complete sample. No child gender differences were found in mother–child and father–child interactions; therefore, the data are reported for girls and boys combined.

Descriptive statistics

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for durations of child solitary and collaborative play with mother and father. Table 3 shows durations of mothers’ and fathers’ play.

Table 2.

Descriptive and inferential statistics for child play by situation

| Child solitary play |

Child collaborative play with mother |

Child collaborative play with father |

F(2, 38) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exploratory play (duration in s) | M | 31.68a | 42.37b | 54.79b | 2.86* |

| SD | 52.38 | 37.78 | 58.93 | ||

| Median | 7 | 30 | 30 | ||

| Symbolic play (duration in s) | M | 55.11a | 55.84a | 112.84b | 3.22* |

| SD | 76.90 | 6.04 | 96.00 | ||

| Median | 16 | 36 | 85 |

Reported F-values refer to the separate repeated measures anovas performed on the summary indexes of play;

P ≤ 0.01.

Means with different subscripts refer to significant differences in summary indexes at Tukey HSD post-hoc tests.

Table 3.

Maternal and paternal play in collaborative play sessions

| Mother play | Father play | t(19)° | r(18) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exploratory play (duration in s) |

M | 59.81 | 45.85 | 2.23* | −0.29 |

| SD | 46.58 | 44.01 | |||

| Median | 31 | 51 | |||

| Symbolic play (duration in s) |

M | 33.05 | 63.70 | −2.38* | 0.12 |

| SD | 26.52 | 48.73 | |||

| Median | 26 | 60 |

Reported t-values refer to independent tests performed on the summary indexes of play;

P ≤ 0.01.

Reported r values refer to Pearson’s correlation coefficients between summary indexes of play.

Child solitary and collaborative play

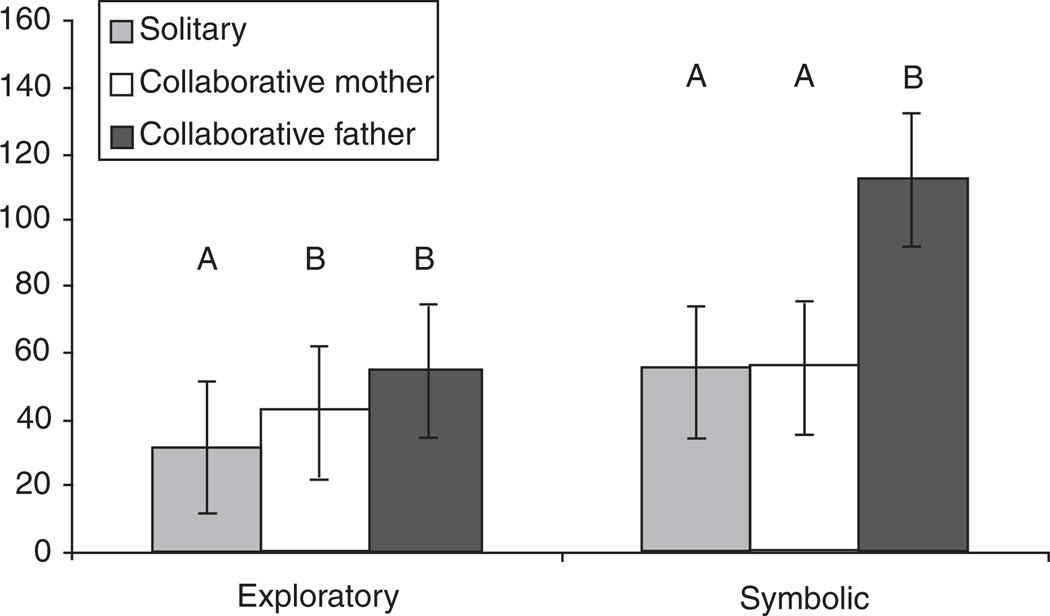

A significant difference emerged in the summary indexes of child exploratory play across the three situations, F(2, 38) = 3.92, P < 0.05. Tukey HSD post-hoc tests showed that children engaged less in exploratory play during the solitary session than during the mother–child and father–child collaborative situations, which did not differ from one another. A significant difference was found in the summary indexes of child symbolic play across the three situations F(2, 38) = 3.32, P < 0.05, and Tukey HSD post-hoc analyses showed that children with DS played more symbolically when playing with their father than when they were playing with their mother or alone; no differences emerged between solitary and mother–child collaborative sessions (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Child exploratory and symbolic play by situation. Bars with different letters represent significant mean differences in summary indexes at Tukey HSD post-hoc tests for P < 0.05.

Mothers’ and fathers’ play

The two groups of parents differed in the summary indexes of both exploratory, t(19) = 2.23, P < 0.05, and symbolic play, t(19) = −2.38, P < 0.05. Specifically fathers showed more exploratory activity than mothers, and mothers displayed more symbolic play than fathers (Table 3).

Association between maternal and paternal lay

No significant correlations emerged between the two parents in either exploratory, r = −0.29, ns, or symbolic play, r = 0.12, ns.

Association between parent and child play

Correlation analyses showed significant strong positive associations between the summary indexes of child and father exploratory play, r(18) = 0.62, P < 0.001, and between the summary indexes of child and father symbolic play, r(18) = 0.50, P < 0.05. In mother–child collaborative play, correlation coefficients were also strong, but on account of sample size, reached only marginal significance for both exploratory, r(18) = 0.42, P = 0.08 and symbolic, r(18) = 0.42, P = 0.08 play.

The Yules’s Q analysis highlighted that the probability of co-occurrence of the same play level between the child and his/her father during the collaborative session was 0.71 for exploratory play and 0.40 for symbolic play. In mother–child collaborative session the probability of co-occurrence of the same play level between the child and the mother was 0.50 for exploratory play and 0.35 for symbolic play.

Discussion

Most studies about parent–child play in children with DS have involved mothers. However, there are several reasons for an investigation of the specific contributions of fathers to the play behaviours of their children with DS (Goldberg et al. 1986; Bristol et al. 1988; Damrosch & Perry 1989; Quinn 1999; Olsson & Hwang 2001; Simmerman et al. 2001; Shin et al. 2006; Senese et al. 2008). Therefore, in the present study we aimed to compare mother–child and father–child play within the same families of children with DS by comparing three semi-structured situations: child solitary play, child collaborative play with mother, and child collaborative play with father. Specifically, we aimed to assess how child play with each parent differed from child solitary play, how mothers and fathers compared in play with their DS children; whether mother and father play was correlated; and, finally, how attuned paternal and maternal play were to their children’s play.

We found that, from solitary to collaborative play, children with DS (like typically developing children), increase in their exploratory play with both fathers and mothers. Exploratory activity represents a specific challenge for children with DS. In fact, several studies have demonstrated that, even when compared to children of the same mental age, children with DS show poor exploratory play; this deficit has been explained by their lack of object mastery (Ruskin et al. 1994) or a failure to maintain attention on objects (Landry & Chapieski 1989) and could also be related to other basic deficits of children with DS, such as movement or instrumental thinking. Our data suggest that fathers and mothers alike are able to help their children to enhance what they specifically lack. By participating in their children’s play, both parents provide the adequate support that children with DS need to overcome their basic difficulties in solitary exploration.

By contrast, children in our sample increased in symbolic activity from solitary to collaborative play only with their fathers. Symbolic play includes the use of representations and pretence which underscore more complex cognitive skills compared to most exploratory behaviours. Previous studies of children with DS have highlighted that their symbolic play skills are substantially linked to their general intellectual impairment, rather than to a specific deficit and are therefore similar to those of metal age-matched typically developing children. Therefore, we can conclude that in our study fathers seemed to be more able than mothers in promoting a kind of play that is cognitively advanced although not specifically compromised in this population.

Altogether these results expand the literature on parent–child play in children with DS by extending to fathers the influential role on their children’s play that has been previously highlighted mostly by studies involving mothers. Moreover, from the direct comparison of child play with the two parents, we found that children with their fathers displayed the same amount of exploratory, but a higher amount of symbolic activity than with mothers. Therefore, children played more during the collaborative session with their fathers and the extra-time consisted of a more advanced kind of play. Thus, this study offers some evidence that children with DS might benefit more from their fathers’ than from their mothers’ play during joint play in terms of their increased play sophistication.

How did fathers succeed in promoting more pretence in their children compared to mothers? This result may be interpreted in light of the literature on fatherhood in typical development that depicts the paternal role in parenting as largely carried out through play (Hewlett 1992; Lamb 1997a,b; Caneva & Venuti 1998). Fathers are reported as more active playmates for their children compared to mothers (Lamb 1977a,b; Tamis-LeMonda 2004), and this investment in play may be conducive to children advancing in their symbolic behaviours when in collaborative play.

It could be that fathers in our sample in the collaborative situation stimulated their children more by displaying more symbolic play themselves compared to their wives. But this interpretation is not supported by our findings; fathers did not display more symbolic play than mothers. By contrast, our results indicate that fathers play significantly less symbolically and more at exploration than mothers did. Thus, it appears as if mothers tried more than fathers to demonstrate symbolic play to their children but children followed them less than their fathers. Moreover, not only did the play behaviours of mothers and fathers appear to differ in our sample but they were not associated with one another; although playing with the same child, who has the same abilities and characteristics, the two parents engaged in different behaviours when joining him/her in play.

A possible explanation for the unique paternal influence on child symbolic play may concern parent–child attunement. Perhaps fathers did not over-demonstrate symbolic play to their children, but they tried to promote pretence mostly when there was a joint focus on this kind of play. Our correlation and contingency analyses partially support this hypothesis; when playing together, fathers and children in our sample showed a high degree of mutual attunement. Therefore, fathers may tailor their behaviour to their children’s abilities and interests, and at the same time children with DS respond to their fathers’ bids. The associations between fathers and their children’s play were strong both for exploratory and symbolic play, highlighting attunement that represents an essential social frame for cognitive development (Vygotsky 1978; Greenspan 1997; Venuti 2007). By contrast the degree of mutual attunement was somewhat lower for mother–child play; however, all the correlations were positive, and a small n (low power) may be the reason we did not achieve statistical significance.

Future research is needed to examine more broadly the types of behaviours mothers and fathers use to match or scaffold their child’s play. Specifically, behaviours such as imitation, modelling, verbal requests, and encouragement as well as the function of maternal or paternal play (beyond level) would provide insight into the way parents differently influence their children’s play skills. In this connection, several limitations in this study should be noted. First, as is common in studies of clinical populations, the sample was relatively small and unbalanced in terms of child gender. Second, we analysed only three 10 min sessions per child. Third, our sample came from a homogeneously middle-to-low socioeconomic status. Fourth, the inclusion of other variables, such as maternal and paternal levels of stress, anxiety, and self-perception of parenting efficacy, might enrich future understanding of parent–child play in DS. Fifth, the inclusion of control groups of typically developing children and of children with intellectual disabilities with mixed aetiology would enable future researchers to draw conclusions more specific to the population of individuals with DS. Finally, we investigated parent–child attunement in play through correlations, but sequential analysis might give additional and more specific information about synchrony within parent– child play exchanges.

In conclusion, this study shows that maternal and paternal contributions to the play skills of their children with DS are both positive but different. During collaborative play children received specific and nonoverlapping scaffolding from their two parents and fathers seemed to provide a unique contribution. For this reason, these results point to the importance of including fathers in early intervention programs for children with DS. Especially through their play, fathers may exert a unique and supplementary role in successfully parenting a child with DS.

References

- Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development. 2nd edn. San Antonio, TX: Manual. Psychological Corp.; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Beeghly M, Cicchetti D. An organizational approach to symbolic development in children with Down syndrome. NCMJ Directions in Child Development. 1987;36:5–29. doi: 10.1002/cd.23219873603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeghly M, Weiss-Perry BW, Cicchetti D. Structural and affective dimensions of play development in young children with Down syndrome. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1989;12:257–277. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Outliers and improper solutions: A confirmatory factor analysis example. Sociological Methods and Research. 1987;15:375–384. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH. On the significance of social relationships in the development of children’s earliest symbolic play: An ecological perspective. In: Gönçü A, Gaskins S, editors. Play and Development: Evolutionary, Sociocultural, and Functional Perspectives. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2007. pp. 101–129. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, O’Reilly AW. The Role of Play in the Development of Thought. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Haynes OM, O’Reilly AW, Painter K. Solitary and collaborative pretence play in early childhood: Sources of individual variation in the development of representational competence. Child Development. 1996;67:2910–2929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Venuti P, Hahn C. Mother–child play in Italy: regional variation, individual stability, and mutual dyadic influence. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2002;2:273–301. [Google Scholar]

- Bristol M, Gallagher J, Shopler E. Mothers and fathers of young developmentally disabled and nondisabled boys: adaptation and spousal support. Developmental Psychology. 1988;24:441–451. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Lewis M. Maternal responsivity. Interactions with handicapped infants Child Development. 1984;55:782–793. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1984.tb03815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldera YM, Huston AC, O’Brien M. Social interactions and play patterns of parents and toddlers with feminine, masculine, and neutral toys. Child Development. 1989;60:70–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb02696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caneva L, Venuti P. Stile materno e stile paterno nel gioco con i figli: uno studio osservativo a tre e tredici mesi. Psicologia Clinica dello Sviluppo. 1998;2:303–326. [Google Scholar]

- Cielinski KL, Vaughn BE, Seifer R, Contreras J. Relations among sustained engagement during play, quality of play, and mother–child interaction in samples of children with Down syndrome and normally developing toddlers. Infant Behaviour and Development. 1995;18:163–176. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CC, Glenn SM, Wilkinson P, Sloper P. Mental ability, symbolic play and receptive and expressive language of young children with Down’s syndrome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1985;26:255–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1985.tb02264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damrosch S, Perry L. Self-reported adjustment, chronic sorrow, and coping of parents of children with Down Syndrome. Nursing Research. 1989;38:25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Falco S, Esposito G, Venuti P, Bornstein MH. Father’s play with their Down Sindrome children. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2008;52:490–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2008.01052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fewell RR, Ogura T, Notari-Syverson A, Wheeden CA. The relationship between play and communication skills in young children with DS. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 1997;17:103–118. [Google Scholar]

- Fidler DJ. The emergence of a syndrome-specific personality profile in young children with Down syndrome. Down Syndrome: Research & Practice. 2006;10:53–60. doi: 10.3104/reprints.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiese BH. Playful relationships: a contextual analysis of mother–toddler interaction and symbolic play. Child Development. 1990;61:1648–1656. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J. Applied Regression Analysis, Linear Models and Related Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Glidden LM, Billings FJ, Jobe BM. Personality, coping style and well-being of parents rearing children with developmental disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2006;50:949–962. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg S, Marcovitch S, MacGregor D, Lojkasek M. Family responses to developmentally delayed preschoolers: etiology and the father’s role. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 1986;90:610–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenspan SJ. Developmentally Based Psychotherapy. Madison, CT: International University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hewlett B. Father–Child Relations: Cultural and Biosocial Contexts. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hill PM, McCune-Nicolich L. Pretend play and patterns of cognition in Down’s syndrome. Child Development. 1981;52:611–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodapp RM. Parenting children with mental retardation. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of Parenting, How Children Influence Parents . 2nd edn. Volume I. Erlbaum, NJ: Hillsdale; 2002. pp. 355–381. [Google Scholar]

- Hodapp RM. Families of persons with Down syndrome: new perspectives, findings, and research and service needs. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 2007;13:279–287. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. The Four Factor Index of Social Status. Unpublished manuscript, Yale University; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Krakow JB, Kopp CB. Sustained engagement in young DS children. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 1982;2:32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME. Father-infant and mother-infant interaction in the first year of life. Child Development. 1977b;48:167–181. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME, editor. The Role of the Father in Child Development. 3rd edn. New York: Wiley; 1997a. [Google Scholar]

- Landry SH, Chapieski ML. Joint attention and infant toy exploration effects of DS and prematurity. Child Development. 1989;60:103–l. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby S, Powell S, Messer D, Jordan R. Imitation of pretend play acts by children with autism and DS. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1997;27:365–383. doi: 10.1023/a:1025801304279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcheschi M, Millepiedi S, Bargagna S. Lo sviluppo del gioco e l’interazione madre-bambino nel bambino Down. Psichiatria dell’Infanzia e dell’Adolescenza. 1990;3:645–652. [Google Scholar]

- McCune-Nicholich L. Toward symbolic functioning: structure of early pretend games and potential parallels with language. Child Development. 1981;52:785–797. [Google Scholar]

- Mundy P, Sigman M, Ungerer J, Sherman T. Nonverbal communication and play correlates of language development in autistic children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1987;17:349–364. doi: 10.1007/BF01487065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll LM, Harding CB. The relationship of mother–child interaction and the child’s development of symbolic play. Infant Mental Health. 2003;24:557–570. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson MB, Hwang CP. Depression in mothers and fathers of children with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2001;45:535–543. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2001.00372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD. Fatherhood. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD. Mahwah. Parke fathers and families. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of Parenting Volume 3, Being and Becoming a Parent (2e) Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 27–73. [Google Scholar]

- Piaget J. Play, Dreams and Imitation in Childhood. New York: Norton; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn P. Supporting and encouraging father involvement in families of children who have a disability. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal. 1999;16:439–454. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci LA, Hodapp RM. Fathers of children with Down’s syndrome versus other types of intellectual disability: perceptions, stress and involvement. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2003;47:273–284. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2003.00489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach MA, Barratt MS, Miller JF, Leavitt JA. The structure of mother–child play: young children with Down syndrome and typically developing children. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:77–87. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach MA, Orsmond GI, Barratt MS. Mothers and fathers of children with Down syndrome: Parental stress and involvement in childcare. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 1999;104:422–436. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(1999)104<0422:MAFOCW>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruskin E, Mundy P, Kasari C, Sigman M. Object mastery motivation in children with DS. American Journal of Mental Retardation. 1994;98:499–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer JE, Armentrout JA. The effects of peer-buddies on increased initiation of social interaction of a middle school student with Down syndrome and her typical peers. Down Syndrome Quarterly. 2002;7:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Senese VP, La Femina F, Buro L, Saladino G, Di Lucia G. Effetti dello sviluppo atipico sulla relazione genitori-figli: uno studio preliminare. Padova: Congresso Nazionale della Sezione di Psicologia Dinamico-Clinica; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shin J, Nhan NV, Crittenden KS, Hong HTD, Flory M, Ladinsky J. Parenting stress of mothers and fathers of young children with cognitive delays in Vietnam. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2006;50:748–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigman M, Ruskin E. Continuity and change in the social competence of children with autism, Down syndrome, and developmental delays. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1999;64:v–114. doi: 10.1111/1540-5834.00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigman M, Sena R. Pretend play in high-risk and developmentally delayed children. In: Bornstein MH, O’Reilly A, editors. New Directions for Child Development: The Role of Play in the Development of Thought. Volume 59. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1993. pp. 29–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmerman S, Blacher J, Baker B. Fathers’ and mothers’ perceptions of father involvement in families with young children with a disability. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability. 2001;26:325–338. [Google Scholar]

- Stoneman Z. Examining the Down syndrome advantage: mothers and fathers of young children with disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2007;51:1006–1017. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2007.01012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. New York: HarperCollins College Publishers; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Tamis-LeMonda CS. Conceptualizing fathers’ roles: playmates and more. Human Development. 2004;47:220–227. [Google Scholar]

- Tamis-LeMonda CS, Bornstein MH. Variation in children’s exploratory, nonsymbolic, and symbolic play: an explanatory multidimensional framework. In: Rovee-Collier CR, Lipsitt LP, editors. Advances in Infancy Research. Volume 10. Norwood, NJ: Ablex; 1996. pp. 37–78. [Google Scholar]

- Venuti P. Percorsi evolutivi: Forme Tipiche e Atipiche . Rome: Carocci; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Venuti P, Giusti F. Madre e Padre: antropologia, scienze dell’evoluzione e psicologia. Firenze: Giunti; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Venuti P, Rossi G, Spagnoletti MS, Famulare E, Bornstein MH. Gioco non simbolico e simbolico a 20 mesi: comportamenti di gioco del bambino e della madre. Età Evolutiva. 1997;10:25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Venuti P, de Falco S, Giusti Z, Bornstein MH. Play and emotional availability in young children with Down Syndrome. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2008;29:133–152. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicari S. Motor Development and Neuropsychological Patterns in Persons with Down Syndrome. Behavior Genetics. 2006;36:355–364. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky L. Mind in Society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]