Abstract

Background:

Smokeless and cigarette tobacco use is becoming increasingly popular among Nigerian adolescents. This study aimed to evaluate predictors of intention to quit tobacco use among adolescents that currently use tobacco products in Nigeria.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 536 male and female high school students in senior classes in Benue State, Nigeria were enrolled into the cross-sectional study. The survey instrument was adapted from the Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) questionnaire.

Results:

Among adolescents with tobacco habits, 80.5% of smokeless tobacco users and 82.8% of cigarette smokers intended to quit tobacco use within 12 months. After adjustment, significant predictors of intention to quit cigarette smoking were parents’ smoking status (P<0.01), peers’ smokeless use status (P<0.01) and perception that smoking made one comfortable at social events (P<0.01). For intention to quit smokeless tobacco use, significant predictors after adjustment were parents’ smokeless use status, (P=0.03) perception that smokeless tobacco use made one more comfortable at social events (P=0.04) and perception of harm from smokeless use (P=0.02).

Conclusion:

This study demonstrates that the intention to quit smokeless and cigarette tobacco use is significantly predicted by perception about the societal acceptance of tobacco use at social events, parents and peers’ tobacco use status as well as the perception of harm from use of tobacco products. Providing social support may increase quit attempts among youth smokers.

Keywords: Adolescents, cigarettes, intention to quit, interventions, smokeless-tobacco, smoking, tobacco

INTRODUCTION

Initiation of tobacco use in adolescents is usually due to interplay of several social factors including academic and domestic stress, peer pressure, motivation by smoking behavior of parents and siblings, the media, secondhand smoke exposure, curiosity, and a drive for experimentation.1–3 While Smoking initiation is often situational and sometimes used in negotiating social relationships and identity, such risk taking behavior may lead to a life-long addiction to smoking.4

The socio-ecological model offers a theoretical framework to community-based interventions for smoking cessation among adolescents. The model considers smoking as not only an individual, but also a social problem. Adolescent smoking habits are influenced by a repertoire of individual, organizational, and interpersonal factors.5 While individual motivation factors predict quit attempts, this is not sufficient in and of itself to ensure that cessation is maintained as other inter-personal factors may be critical to smoking cessation.6 Thus, implementing robust strategies for reducing the prevalence of adolescent smoking require a consideration of individual, interpersonal, and communal factors.

While several populations-based studies have documented the prevalence of cigarette use among Nigerian adolescents, there is paucity of data on factors predicting intention to quit tobacco use among Nigerian adolescents. Therefore, this population-based study was conducted to explore predictors of intention to quit smokeless and cigarette tobacco among Nigerian youth. This paper considers intention to quit tobacco in the light of the socio-ecological model which views smoking behavior as affected by and affecting multiple spheres of influence and individual behavior.7

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a cross-sectional study using structured questionnaires, conducted in Benue state, Nigeria between April and May 2011. Approval for the study was obtained from the institutional review boards of the Harvard School of Public Health, the Federal Medical Center, Makurdi, Nigeria, and from all the school principals.

A three-tier multistage sampling procedure was used to select participants into the study. In the first stage, five rural and five urban schools were randomly selected from a listing of secondary schools in the state published by the federal ministry of education. The randomly selected schools were from six local government areas in Benue state. In the second stage, classes were randomly selected from each school proportional to the sizes of the schools. Thirdly, individual participants were randomly selected from the classes.

RESULTS

“Ever use” prevalence of cigarette smoking was 27.4% while “current use” was 19.4%. About 11.9% of the total study population were current concurrent users of both smokeless and cigarette tobacco. About 82.8% of current cigarette smokers intended to quit tobacco use within 12 months.

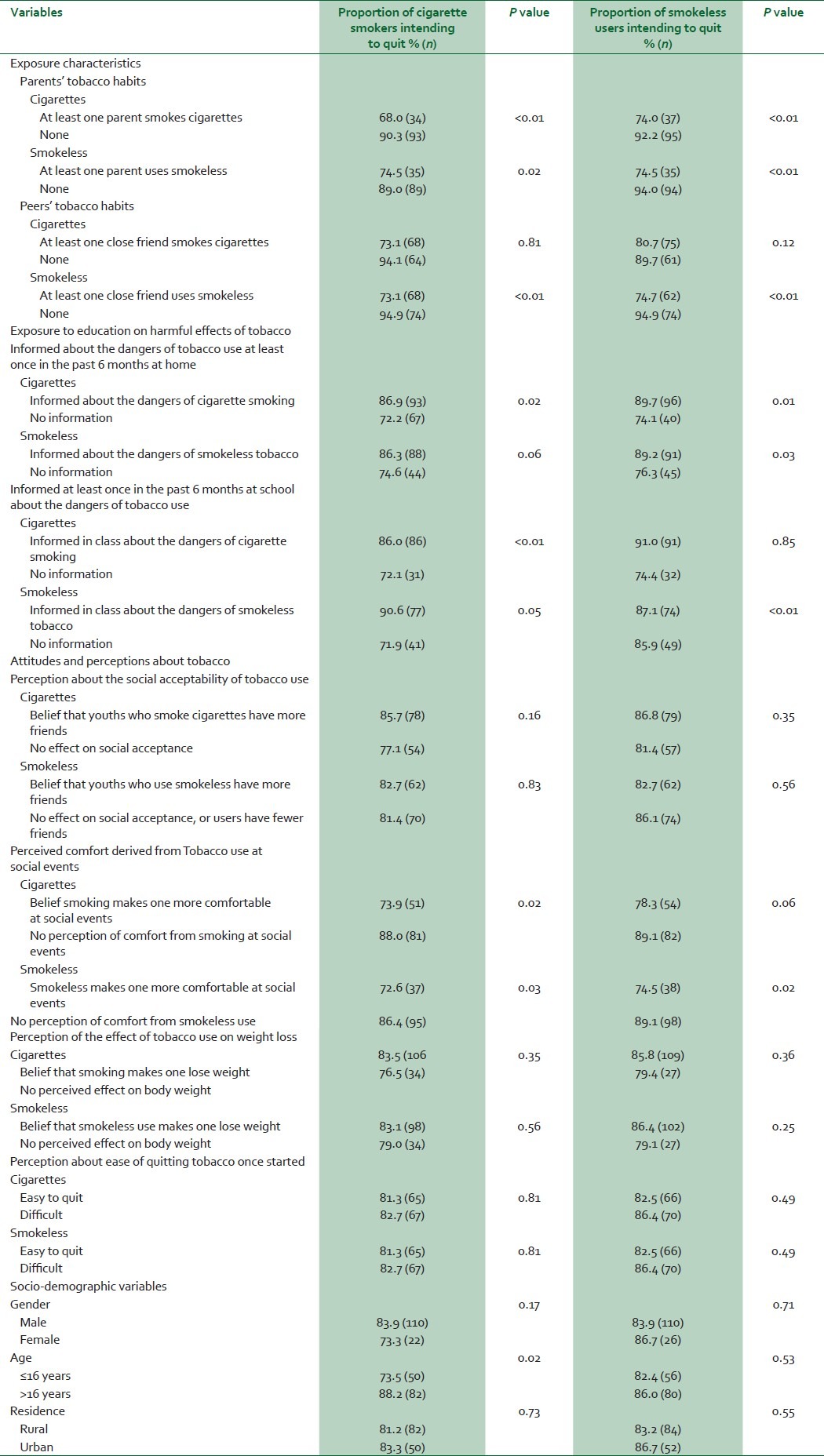

Bivariate analysis indicated that variables significantly associated with intention to quit cigarette smoking included age (P=0.02), parents’ smoking status (P<0.01), parents’ smokeless use status (P=0.02), peers’ smokeless use status (P<0.01), exposure to information at home about the dangers of cigarette smoking (P=0.02), inclusion of information in school curriculum on dangers of cigarette and smokeless use (P<0.01, P=0.05 respectively), perception of harm from cigarette smoking (P<0.01) and perception that smoking made one more comfortable at social events (P=0.02) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Characteristics of smokeless and cigarette users relating to intention to quit

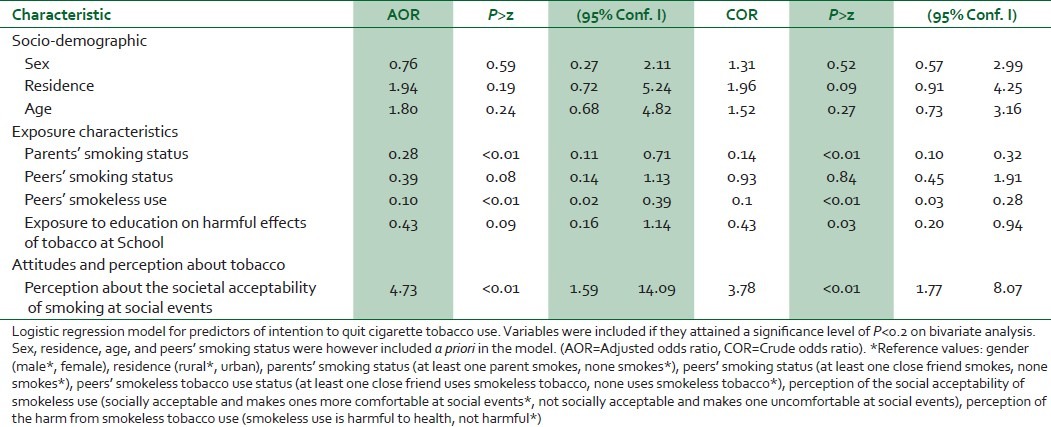

After adjusting for other covariates, significant predictors of intention to quit cigarette smoking were parents’ smoking status, peers’ smokeless use status and perception that smoking made one more comfortable at social events. Smoking adolescents that had at least one smoking parent were less likely to intend to quit compared to those that had no smoking parent (AOR=0.28, P<0.01), similarly, those with at least one close friend that used smokeless tobacco were less likely to quit smoking compared to those with none (AOR=0.10, P<0.01). Adolescent smokers who perceived that smoking was socially unacceptable and made one uncomfortable at social events were over four times more likely to quit smoking than those who perceived otherwise (AOR=4.73, P<0.01) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Estimated crude and adjusted odds ratios, two-sided P values, 95% confidence intervals for predictors of intention to quit cigarette smoking among adolescents in Nigeria

“Ever use” prevalence of smokeless tobacco was 22.0% while “current use” prevalence was 17.7%. Among adolescents with smokeless tobacco habits, 80.5% intended to quit within 12 months.

Significant predictors on bivariate analysis included parents’ smoking status (P<0.01), parents’ smokeless use status (P<0.01), peers’ smokeless use status (P=0.03), inclusion of information in school curriculum on dangers of smokeless use (P<0.01) and perception that smokeless tobacco use made one more comfortable at social events (P=0.02) [Table 1].

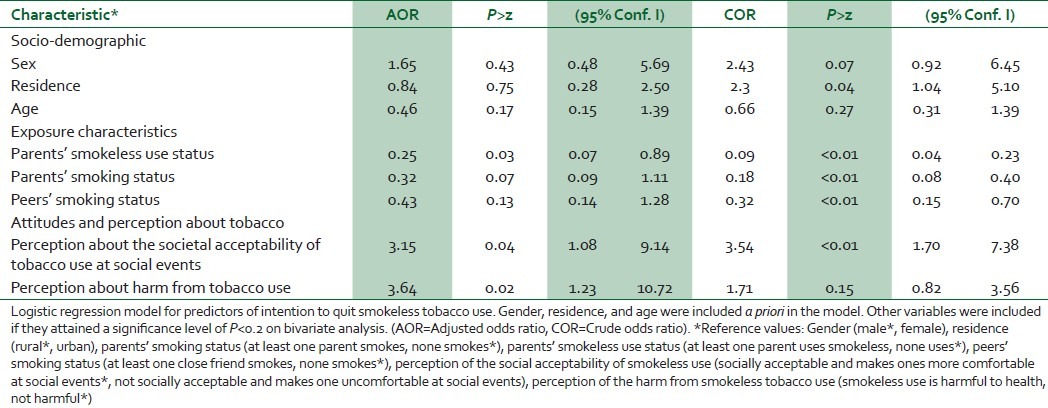

After adjustment, predictors that were significant were parents’ smokeless use status, perception about the social acceptability of tobacco and perception of harm from smokeless use. Adolescent smokeless users who had at least one parent using smokeless were less likely to intend to quit compared to those with none (AOR=0.25, P=0.03), users who perceived smokeless use as being socially unacceptable and made one uncomfortable at social events were over three times more likely to intend to quit that those who perceived otherwise (AOR=3.15, P=0.04). Similarly, users who perceived smokeless use as being harmful to their health were close to four times more likely to quit than those who thought that smokeless use was harmless (AOR=3.64, P=0.02) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Estimated crude and adjusted odds ratios, two-sided P values, 95% confidence intervals for predictors of intention to quit smokeless tobacco use among adolescents in Nigeria

DISCUSSION

Our results showed that intention to quit cigarette and smokeless tobacco use is predicted by parents’ tobacco use status, perception about the social acceptability of tobacco use and perception of harm from tobacco use. Intention to quit has been shown to be a strong predictor of smoking cessation.8 found that the intention to quit and self-efficacy for quitting were important mediators of teen tobacco treatment outcome.

We established in our study that parental smoking status was a significant predictor of intention to quit among smoking adolescents (P<0.01). Parents who smoke are known to influence their children's smoking activities. In a survey of 1,561 Chinese secondary students who were current smokers, those who had parents prohibiting them from smoking and who received social support were more likely to have an intention to quit smoking than those who did not.9 In our study, smoking adolescents that had at least one smoking parent were less likely to intend to quit compared to those that had no smoking parent. This aligns well with a study by10 in which they concluded that encouraging parents to quit might be an effective method for reducing adolescent smoking. They also found that the earlier parents quit, the less likely their children will become smokers.

In our study smokeless and cigarette tobacco use was significantly higher in males than females (P<0.01). In older females the intention to quit may be linked with the anticipation of undesirable effects of smoking in pregnancy but in younger girls the need for social acceptance may be a more logical motivation since females that smoke in the Nigerian setting are lightly esteemed. Indeed Jarallah et al. alluded that women in developing countries tend to smoke less probably due to socio-cultural taboo or religious reasons.11

It is probable that the mean duration of smoking in our population was shorter than in an older population suggesting less dependence on nicotine and a higher tendency towards quitting tobacco use. We suggest here that it may be easier to quit smoking as an adolescent than as a middle aged or elderly person. This aligns with the "hardening hypothesis" which holds that tobacco control activities have mostly influenced those smokers who found it easier to quit and, thus, remaining smokers are those who are less likely to stop smoking. Older cohorts of smokers are thus more likely to have a higher proportion of hardcore smokers.12 In our study the mean duration of smoking among smoking urban adolescents (5.3 years) was higher than that for the rural population (4.2 years). The effects of urban versus rural environment on adolescent development was investigated in a study in Kwara state, Nigeria and it was noted that urban adolescents had higher scores for engaging in diverse vices, including smoking.13

Youth smoking is a serious public health issue, providing social support may help initiate cessation of tobacco use among youths. Considering that perception of youths about the societal acceptance of smoking at social events is such a powerful predictor of intention to quit, large-scale public health interventions could be built around mass communication campaigns in collaboration with the Nigerian movie industry – “Nollywood.” This may involve incorporating health messages within the dialogue of movie scripts to introduce a new social concept that de-normalizes tobacco use among adolescents. This may reinforce intention to quit and strengthen positive health behavior.

CONCLUSION

This study demonstrates that the intention to quit smokeless and cigarette tobacco among Nigerian adolescents is popular and is significantly predicted by perception about the social acceptability of tobacco use, parents and peers’ tobacco use status as well as the perception of harm from use of tobacco products.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge the following individuals: Dr. Swende TZ, Gwar Samuel, Gwar Joy, Agaku Dooshima, Agaku Nguevese, and Gwar Josiah.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Das S, Ghosh M, Sarkar M, Joardar S, Chatterjee R, Chatterjee S. Adolescents speak: Why do we smoke? J Trop Pediatr. 2011;57:476–80. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmr003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nizami S, Sobani ZA, Raza E, Baloch NU, Khan JA. Causes of smoking in Pakistan: An analysis of social factors. J Pak Med Assoc. 2011;61:198–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Voorhees CC, Ye C, Carter-Pokras O, MacPherson L, Kanamori M, Zhang G, et al. Peers, tobacco advertising, and secondhand smoke exposure influences smoking initiation in diverse adolescents. Am J Health Promot. 2011;25:e1–11. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.090604-QUAN-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bidstrup PE, Tjørnhøj-Thomsen T, Mortensen EL, Vinther-Larsen M, Johansen C. Critical discussion of social-cognitive factors in smoking initiation among adolescents. Acta Oncol. 2011;50:88–98. doi: 10.3109/02841861003801155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorini G. Individual, community, regulatory, and systemic approaches to tobacco control interventions. Epidemiol Prev. 2011;35(3-4 Suppl 1):33–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borland R, Yong HH, Balmford J, Cooper J, Cummings KM, O’Connor RJ, et al. Motivational factors predict quit attempts but not maintenance of smoking cessation: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Four country project. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(Suppl):S4–11. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sorensen G, Barbeau E, Hunt MK, Emmons K. Reducing social disparities in tobacco use: A social-contextual model for reducing tobacco use among blue-collar workers. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:230–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Myers MG, Brown SA, Kelly JF. A smoking intervention for substance abusing adolescents: Outcomes, predictors of cessation attempts, and post-treatment substance use. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2000;9:77–91. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong DC, Chan SS, Ho SY, Fong DY, Lam TH. Predictors of intention to quit smoking in hong kong secondary school children. J Public Health (Oxf) 2010;32:360–71. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdp125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farkas AJ, Distefan JM, Choi WS, Gilpin EA, Pierce JP. Does parental smoking cessation discourage adolescent smoking? Prev Med. 1999;28:213–8. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jarallah JS, al-Rubeaan KA, al-Nuaim AR, al-Ruhaily AA, Kalantan KA. Prevalence and determinants of smoking in three regions of Saudi Arabia. Tob Control. 1999;8:53–6. doi: 10.1136/tc.8.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughes JR. The hardening hypothesis: Is the ability to quit decreasing due to increasing nicotine dependence? A review and commentary. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;117:111–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ilesanmi OO, Osiki JO, Falaye A. Psychological effects of rural versus urban environment on adolescent's behaviour following pubertal changes. [Last retrieved on 2011 May 18]. Available from: http://www.faqs.org/periodicals/201003/1973238791.html .