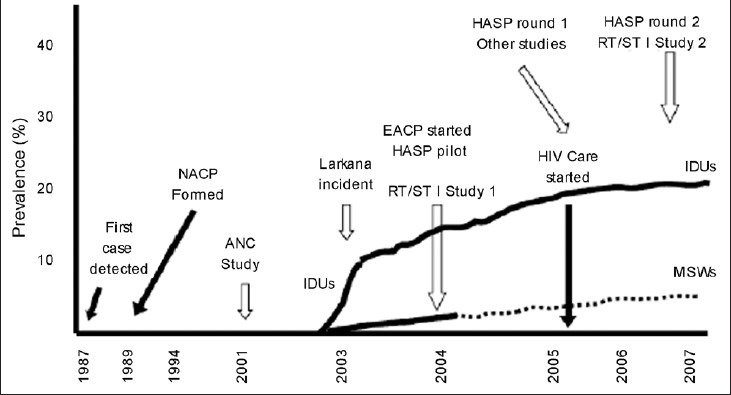

Globally, Human immunodeficiency virus infection / Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) is a major public health problem. According to World Health Organization (WHO), in 2008, there were 33.4 million people living with HIV, 2.7 million were newly diagnosed with HIV, and 2 million died globally due to AIDS.[1] Pakistan, a low-income country has a population of 190 million with 35% of its population below the age of 15 years, and 60% within the age of 15-64 years.[2] According to estimates from 2000, the mean age at first marriage for males was 26.3 years and 22.1 years for females.[3] Pakistan, even though has low burden of HIV/AIDS, with an estimated 85,000 people or 0.1 percent of the adult population living with HIV, the HIV/AIDS epidemic has begun in the country [Figure 1].[4] The epidemic is still “concentrated” in injection drug users (IDUs) and male sex workers (MSWs) including transgender, often called as “Hijras”.[5] According to the March-July 2004 sexually transmitted infections (STI) survey of high risk groups, 23% of 402 IDUs and 4% of 409 men who have sex with men were HIV-positive.[6] However, the volume of unprotected sexual acts and poor infection control strategies are high in the country that may lead this epidemic to general population.[7] Pakistan established National AIDS Control Program (NACP) in 1986-87 with an initial focus on laboratory diagnosis of suspected HIV cases.[8] However, with increasing burden of HIV/AIDS, the program's focus shifted towards HIV prevention and control interventions in the community. The development of National Strategic Framework-one in 2001, the Government of Pakistan with support from the World Bank, launched an enhanced response in the form of Enhanced HIV and AIDS Control Program (EHACP).[8] In 2004, with the support of Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), a five year HIV/AIDS Surveillance Project (HASP) was launched. HASP was a capacity building project involving the NACP, provincial AIDS control programs, and other stakeholders including NGOs, research institutes and laboratories to develop a sustainable second generation surveillance system for HIV/AIDS in the country.[8]

Figure 1.

Evolution of HIV epidemics in Pakistan.[4] NACP: The National AIDS Control Program of Pakistan (Ministry of Health). ANC Study: The Antenatal Clinic Study (2001). EACP: The Enhanced AIDS Control Program of Pakistan. HASP: The HIV/AIDS Surveillance Project.RT/STI Study: The National Study of Reproductive Tract and Sexually Transmitted. Infections (2004). IDUs: Injection Drug Users. MSWs: Male Sex Workers

IDUs, MSWs including transgenders were found to be high-risk groups in Pakistan[4,9] with similar findings by HASP[10] and NACP.[8] The sexual transmission of HIV beyond “core groups,” a proportion of persons who are frequently infected with and transmit the disease, depend upon the members of core groups who have sexual intercourse with members of the general population-so-called “bridge populations”.[11] The prevalence of HIV among general population and female sex workers (FSWs) in Pakistan is still quite low, which is less than 1% and <0.01% respectively.[8] However, according to recent report, the infection has started spreading among FSWs.[10] Bridge populations such as wives of IDUs, clients of sex workers, truck or bus drivers, and migrant workers have high potential to spread this epidemic among general population.[4] Male IDUs often avoid disclosures of their drug use to their wives. Majority of their wives do not know their drug-using activities till they are married, making them generally more helpless to protect them. It has been estimated through recent study in seven cities of Pakistan, the mean number of clients per FSWs varied substantially between cities, ranging from 7.6 per month in Hyderabad to 62.0 per month in Sukkur.[12] Also, the use of condom is low among clients of MSWs; it has been found that greater anal-sex clients, and sex workers reporting 30 or more clients are negatively associated with condom use.[13] Similarly, one quarter of married truck drivers are found to be engaged in commercial or non-commercial extramarital sex, and rarely use condom during sexual act.[4] A large majority of Pakistanis are working abroad[4] especially poor manual workers,[14] and many of them remain away from their homes and families for years.[14] It has been estimated that over half (55%) of single migrant men had sexual experience and 36% of married migrant men reported premarital sex, with a very few individuals wearing condom during sex.[14]

There is already growing evidence from several countries in East Africa about declining HIV prevalence.[15] Lessons from these countries need to be learnt by Pakistan before the spread of this concentrated HIV epidemic in Pakistan to general population. Behavioral change in decreasing sexual encounters with commercial sex, increase use of condom, intensive HIV testing policy with intensive counseling and follow-up of HIV-positive persons, tracing of sexual partners, increasing education, decline in multiple sexual partners, delay in age at first sex, and a reduction in casual sex are some of the strategies that have shown a promising future to decrease HIV epidemic, worldwide.[16,17] Further, good communications and health service infrastructure, control of sexually transmitted infections, social marketing of condoms, voluntary counseling and HIV testing services, television and radio serial dramas on HIV awareness, and among younger women, delayed age at first birth have also proved successful in decreasing HIV epidemic in other countries.[16–18] The effectiveness of these measures needs to be tested, and those that will be found effective should be implemented in settings like Pakistan.

No doubt, through HASP and NACP in Pakistan, progress has been made in drawing attention to the high risk groups for HIV and bridging groups, but these groups have a potential to spread this epidemic to general population. There are still inadequate HIV preventive measures in Pakistan, mainly because of low healthcare budget,[7] and lack evaluation of measures when placed, for their effectiveness. There is less evidence available on the role of spouses/non-commercial partners of sex workers and IDUs, clients of sex workers and other bridging groups in epidemic progression in Pakistan. There is non-existence of national reporting system to enumerate repatriated workers who acquire HIV while abroad, especially the Middle East where mandatory HIV testing is conducted at recruitment, and those who acquire HIV are deported back to Pakistan. There are dearth of studies to understand the risk profiles and networks of migrant men, and those who receive their medications through injections from non-formal medical care providers in the country. HIV is still considered a social stigma not only among general population but also healthcare workers.[7] This stigma hinders HIV positive individuals to disclose their HIV status, making not only their social networks at risk for HIV but also making them unable to receive healthcare from healthcare providers. In addition, it makes difficult for general public to take up voluntary counseling and to get tested. The HIV epidemic in Pakistan is still “concentrated;” this window should be taken as an opportunity to prevent this epidemic to spread to general public by continuous surveillance and implementing evidence-based HIV preventive measures in the country.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Global summary of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, December 2008. 2010. [Last cited on 2010 Nov 18]. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/data/global_data/en/index.html .

- 2.The World Factbook. South Asia: Pakistan. 2011. [Last cited on 2012 Aug 02]. Available from: http://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/pk.html .

- 3.Population Association of Pakistan. Selected Demographic Indicators of Pakistan. 2000. [Last cited on 2012 Aug 02]. Available from: http://www.pap.org.pk/statistics/population.htm#tabfig-1.2 .

- 4.Khan AA, Khan A. The HIV epidemic in Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2010;60:300–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. AIDS and Sexually Transmitted Diseases: Country profiles, Pakistan, Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. 2009. [Last cited on 2010 November 18]. Available from: http://www.emro.who.int/asd/hivsituation_countryprofiles.htm .

- 6.The World Bank. HIV/AIDS in Pakistan. 2006. [Last cited on 2012 Aug 02]. Available from: http://www.siteresources.worldbank.org/INTSAREGTOPHIVAIDS/Resources/HIV-AIDS-brief-August06-PKA.pdf .

- 7.Burki T. New government in Pakistan faces old challenges. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:217–8. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(08)70054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ministry of Health. National AIDS Control Program: Government of Pakistan. 2010. [Last cited on 2010 Nov 20]. Available from: http://www.nacp.gov.pk/

- 9.Khan AA, Rehan N, Qayyum K, Khan A. Correlates and prevalence of HIV and sexually transmitted infections among Hijras (male transgenders) in Pakistan. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19:817–20. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2008.008135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emmanuel F, Blanchard J, Zaheer HA, Reza T, Holte-McKenzie M. HASP Team. The HIV/AIDS Surveillance Project mapping approach: An innovative approach for mapping and size estimation for groups at a higher risk of HIV in Pakistan. AIDS. 2010;24(Suppl 2):S77–84. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000386737.25296.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aral SO. Behavioral aspects of sexually transmitted diseases: Core groups and bridge populations. Sex Transm Dis. 2000;27:327–8. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200007000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blanchard JF, Khan A, Bokhari A. Variations in the population size, distribution and client volume among female sex workers in seven cities of Pakistan. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84(Suppl 2):ii 24–7. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.033167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaw SY, Emmanuel F, Adrien A, Holte-McKenzie M, Archibald CP, Sandstrom P, et al. The descriptive epidemiology of male sex workers in Pakistan: A biological and behavioural examination. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87:73–80. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.041335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faisel A, Cleland J. Migrant men: A priority for HIV control in Pakistan? Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82:307–10. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.018762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asamoah-Odei E, Garcia Calleja JM, Boerma JT. HIV prevalence and trends in sub-Saharan Africa: No decline and large subregional differences. Lancet. 2004;364:35–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Arazoza H, Joanes J, Lounes R, Legeai C, Clemencon S, Perez J, et al. The HIV/AIDS epidemic in Cuba: Description and tentative explanation of its low HIV prevalence. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:130. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-7-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fylkesnes K, Musonda RM, Sichone M, Ndhlovu Z, Tembo F, Monze M. Declining HIV prevalence and risk behaviours in Zambia: Evidence from surveillance and population-based surveys. AIDS. 2001;15:907–16. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200105040-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gregson S, Garnett GP, Nyamukapa CA, Hallett TB, Lewis JJ, Mason PR, et al. HIV decline associated with behavior change in eastern Zimbabwe. Science. 2006;311:664–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1121054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]